19.1 What Is a k-ratio?

Both the numerator and the denominator of the k-ratio must be measured under similar, well-controlled instrument conditions. The electron beam energy must be the same. The probe dose, the number of electrons striking the sample during the measurement, should be the same (or the intensity scaled to equivalent dose.) The position of the sample relative to the beam and to the detector should be fixed. Both the sample and the standard(s) should be prepared to a high degree of surface polish, ideally to reduce surface relief below 50 nm, and the surface should not be chemically etched. If the unknown is non-conducting, the same thickness of conducting coating, usually carbon with a thickness below 10 nm, should be applied to both the unknown and the standard(s). Ideally, the only aspect that should differ between the measurement of the unknown and the standard are the compositions of the materials.

- 1.

The k-ratio eliminates the need to know the efficiency of the detector since both sample and unknown are measured on the same detector at the same relative position. Since the efficiency as a multiplier of the intensity is identical in the numerator and denominator of the k-ratio, the efficiency cancels quantitatively in the ratio.

- 2.

The k-ratio mitigates the need to know the physics of the X-ray generation process if the same elements are excited under essentially the same conditions. The ionization cross section, the relaxation rates, and other poorly known physical parameters are the same for an element in the standard and the unknown.

In the history of the development of quantitative electron-excited X-ray microanalysis, the X-ray intensities for the unknown and standards were measured sequentially with a wavelength spectrometer in terms of X-ray counts. The raw measurement contains counts that can be attributed to both the continuum background (bremsstrahlung) and characteristic X-rays. Since k-ratio is a function of only the characteristic X-rays, the contribution of the continuum must be estimated. Usually, this is accomplished by measuring two off-peak measurements bounding the peak and using interpolation to estimate the intensity of the continuum background at the peak position. The estimated continuum is subtracted from the measured on peak intensity to give the characteristic X-ray line intensity.

Extracting the k-ratio with an energy dispersive spectrometer can be done in a similar manner for isolated peaks. However, to deal with the peak interferences frequently encountered in EDS spectra, it is necessary to simultaneously consider all of the spectrum channels that span the mutually interfering peaks. Through a process called linear least squares fitting, a scale factor is computed which represents the multiplicative factor by which the integrated area under the characteristic peak from the standard must be multiplied by to equal the integrated area under the characteristic peak from the unknown. This scale factor is the k-ratio, and the fitting process separates the intensity components of the interfering peaks and the continuum background. The integrated counts measured for the unknown and for the standard for element Z enable an estimate of the precision of the measurement for that element. Linear least squares fitting is employed in NIST DTSA-II to recover characteristic X-ray intensities, even in situations with extreme peak overlaps.

A measured k-ratio of zero suggests that there is none of the associated element in the unknown. A measurement on a standard with exactly the same composition as the unknown will nominally produce a k-ratio of unity for all elements present. Typically, k-ratios will fall in a range from 0 to 10 depending on the relative concentration of element Z in the unknown and the standard. A k-ratio less than zero can occur when count statistics and the fitting estimate of the background intensity conspire to produce a slightly negative characteristic intensity. Of course, there is no such thing as negative X-ray counts, and negative k-ratios should be set to zero before the matrix correction is applied. A k-ratio larger than unity happens when the standard generates fewer X-rays than the unknown. This can happen if the standard contains less of the element and/or if the X-ray is strongly absorbed by the standard. Usually, a well-designed measurement strategy won’t result in a k-ratio much larger than unity. We desire to use a standard where the concentration of element Z is high so as to minimize the contribution of the uncertainty in the amount of Z in the standard to the overall uncertainty budget of the measurement, as well as to minimize the uncertainty contribution of the count statistics in the standard spectrum to the overall measurement precision. The ideal standard to maximize concentration is a pure element, but for those elements whose physical and chemical properties prohibit them from being used in the pure state, for example, gaseous elements such as Cl, F, I, low melting elements such as Ga or In, or pure elements which deteriorate under electron bombardment, for example, P, S, a binary compound can be used, for example, GaP, FeS2, CuS, KCl, etc.

TIP

To get the most accurate trace and minor constituent measurements, it is best to average together many k-ratios from distinct measurements before applying the matrix correction. Don’t truncate negative k-ratios before you average or you’ll bias your results in the positive direction.

19.2 Uncertainties in k-ratios

All k-ratio measurements must have associated uncertainty estimates. The primary source of uncertainty in a k-ratio measurement is typically count statistics although instrumental instability also can contribute. X-ray emission is a classic example of a Poisson process or a random process described by a negative exponential distribution.

Negative exponential distributions are interesting because they are “memoryless.” For a sequence of events described by a negative exponential distribution, the likelihood of an event’s occurring in an interval τ is equally as likely regardless of when the previous event occurred. Just because an event hasn’t occurred for a long time doesn’t make an event any more likely in the subsequent time interval. In fact, the most probable time for the next event is immediately following the previous.

If X-rays are measured at an average rate R, the average number of X-rays that will be measured over a time t is N = R · t. Since the X-ray events occur randomly dispersed in time, the actual number measured in a time t will rarely ever be exactly N = R · t. Instead, 68.2 % of the time the actual number measured will fall within the interval (N – ΔN, N + ΔN) where ΔN ~ N 1/2 when N is large (usually true for X-ray counts). This interval is often called the “one sigma” interval. The one-sigma fractional uncertainty is thus N/N 1/2 = 1/N 1/2, which for constant R decreases as t increased. This is to say that generally, it is possible to make more precise measurements by spending more time making the measurement. All else remaining constant, for example, instrument stability and specimen stability under electron bombardment, a measurement taken for a duration of 4 t will have twice the precision of a measurement take for t.

Poisson statistics apply to both the WDS and EDS measurement processes. For WDS, the on-peak and background measurements all have associated Poissonian statistical uncertainties. For EDS, each channel in the spectrum has an associated Poissonian statistical uncertainty. In both cases, the statistical uncertainties must be taken into account carefully so that an estimate of the measurement precision can be associated with the k-ratio.

The best practices for calculating and reporting measurement uncertainties are described in the ISO Guide to Uncertainty in Measurement (ISO 2008). Marinenko and Leigh (2010) applied the ISO GUM to the problem of k-ratios and quantitative corrections in X-ray microanalytical measurements. In the case of WDS measurements, the application of ISO GUM is relatively straightforward and the details are in Marinenko and Leigh (2010). For EDS measurements, the process is more complicated. If uncertainties are associated with each channel in the standard and unknown spectra, the k-ratio uncertainties are obtained as part of the process of weighted linear squares fitting.

19.3 Sets of k-ratios

Typically, a single compositional measurement consists of the measurement of a number of k-ratios—typically one or more per element in the unknown. The k-ratios in the set are usually all collected under the same measurement conditions but need not be. It is possible to collect individual k-ratios at different beam energies, probe doses or even on different detectors (e.g., multiple wavelength dispersive spectrometers or multiple EDS with different isolation windows).

There may more than one k-ratio per element. Particularly when the data is collected on an energy dispersive spectrometer, more than one distinct characteristic peak per element may be present. For period 4 transition metals, the K and L line families are usually both present. In higher Z elements, both the L and M families may be present. This redundancy provides a question – Which k-ratio should be used in the composition calculation?

While it is in theory possible to use all the redundant information simultaneously to determine the composition, standard practice is to select the k-ratio which is likely to produce the most accurate measurement. The selection is non-trivial as it involves difficult to characterize aspects of the measurement and correction procedures. Historically, selecting the optimal X-ray peak has been something of an art. There are rules-of-thumb, but they involve subtle compromises and deep intuition.

19.4 Converting Sets of k-ratios Into Composition

As stated earlier, the k-ratio is often a good first approximation to the composition. However, we can do better. The physics of the generation and absorption of X-rays is sufficiently well understood that we can use physical models to compensate for non-ideal characteristics of the measurement process. These corrections are called matrix corrections as they compensate for differences in the matrix (read matrix to mean “material”) between the standard material and the unknown material.

- 1.

Estimate the composition of the unknown. Castaing’s First Approximation is a good place to start.

- 2.

Calculate an improved estimate of CZ,unk based on the previous estimated composition.

- 3.

Update the composition estimate based on the new calculation.

- 4.

Test whether the resulting computed k-ratios are sufficiently similar to the measured k-ratios.

- 5.

Repeat steps 2–5 until step 4 is satisfied.

While there is no theoretical guarantee that this algorithm will always converge or that the result is unique, in practice, this algorithm has proven to be extremely robust.

19.5 The Analytical Total

The result of the iteration procedure is a set of estimates of the mass fraction for each element in the unknown. We know these mass fractions should sum to unity—they account for all the matter in the material. However, the measurement process is not perfect and even with the best measurements there is variation around unity.

The sum of the mass fractions is called the analytical total. The analytical total is an important tool to validate the measurement process. If the analytic total varies significantly from unity, it suggests a problem with the measurement. Analytical totals less than one can suggest a missed element (such as an unanticipated oxidized region of the specimen), a reduced excitation volume, an unanticipated sample geometry (film or inclusion), or deviation from the measurement conditions between the unknown and standard(s). Analytic totals greater than unity likely arise because of measurement condition deviation or sample geometry issues.

19.6 Normalization

Careful inspection of the raw analytical total is a critical step in the analytical process. If all constituents present are measured with a standards-based/matrix correction procedure, including oxygen (or another element) determined by the method of assumed stoichiometry, then the analytical total can be expected to fall in the range 0.98 to 1.02 (98 weight percent to 102 weight percent). Deviations outside this range should raise the analyst’s concern. The reasons for such deviations above and below this range may include unexpected changes in the measurement conditions, such as variations in the beam current, or problems with the specimen, such as local topography such as a pit or other excursion from an ideal flat polished surface. For a deviation below the expected range, an important additional possibility is that there is at least one unmeasured constituent. For example, if a local region of oxidation is encountered while analyzing a metallic sample, the analytical total will drop to approximately 0.7 (70 weight percent) because of the significant fraction of oxygen in a metal oxide. Note that “standardless analysis” (see below) may automatically force the analytical total to unity (100 weight percent) because of the loss of knowledge of the local electron dose used in the measurement. Some vendor software uses a locally measured spectrum on a known material, e.g., Cu, to transfer the local measurement conditions to the conditions used to measure the vendor spectrum database. Another approach is to use the peak-to-background to provide an internal normalization. Even with these approaches, the analytical total may not have as narrow a range as standards-based analysis. The analyst must be aware of what normalization scheme may be applied to the results. An analytical total of exactly unity (100 weight percent) should be regarded with suspicion.

19.7 Other Ways to Estimate CZ

k-ratios are not the only information we can use to estimate the amount of an element Z, C Z. Sometimes it is not possible or not desirable to measure k Z. For example, low Z elements, like H or He, don’t produce X-rays or low Z elements like Li, B and Be produce X-rays which are so strongly absorbed that few escape to be measured. In other cases, we might know the composition of the matrix material and all we really care about is a trace contaminant. Alternatively, we might know that certain elements like O often combine with other elements following predictable stoichiometric relationships. In these cases, it may be better to inject other sources of information into our composition calculation algorithm.

19.7.1 Oxygen by Assumed Stoichiometry

Oxygen can be difficult to measure directly because of its relatively low energy X-rays. O X-rays are readily absorbed by other elements. Fortunately, many elements combine readily with oxygen in predictable ratios. For example, Si oxidizes to form SiO2 and Al oxidizes to form Al2O3. Rather than measure O directly, it is useful to compute the quantity of other elements from their k-ratios and then compute the amount of O it would take to fully oxidize these elements. This quantity of O is added in to the next estimated composition.

NIST DTSA-II has a table of common elemental stoichiometries for calculations that invoke assumed stoichiometry. For many elements, there may be more than one stable oxidation state. For example, iron oxidizes to FeO (wüstite), Fe3O4 (magnetite), and Fe2O3 (hematite). All three forms occur in natural minerals. The choice of oxidation state can be selected by the user, often relying upon independent information such as a crystallographic determination or based upon the most common oxidation state that is encountered in nature.

The same basic concept can be applied to other elements which combine in predicable ratios.

19.7.2 Waters of Crystallization

Water of crystallization (also known as water of hydration or crystallization water) is water that occurs within crystals. Typically, water of crystallization is annotated by adding “·nH2O” to the end of the base chemical formula. For example, CuSO4 · 5H2O is copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate. This expression indicates that five molecules of water have been added to copper sulfate. Crystals may be fully hydrated or partially hydrated depending upon whether the maximum achievable number of water molecules are associated with each base molecule. CuSO4 is partially hydrated if there are fewer than five water molecules per CuSO4 molecule. Some crystals hydrate in a humid environment. Hydration molecules (water) can often be driven off by strong heating, and some hydrated materials undergo loss of water molecules due to electron beam damage.

Measuring water of crystallization involves measuring O directly and comparing this measurement with the amount of water predicted by performing a stoichiometric calculation on the base molecule. Any surplus oxygen (oxygen measured but not accounted for by stoichiometry) is assumed to be in the form of water and two additional hydrogen atoms are added to each surplus oxygen atom. The resulting composition can be reported as the base molecule + “·nH2O” where n is the relative number waters per base molecule.

19.7.3 Element by Difference

This approach has numerous pitfalls. First, the uncertainty in difference is the sum of the uncertainties for the mass fractions of the N-1 elements. This can be quite large particularly when N is large. Second, since we assume the total mass fraction sums to unity, there is no redundant check like the analytic total to validate the measurement.

19.8 Ways of Reporting Composition

19.8.1 Mass Fraction

Weight fraction, mass percent, weight percent are all commonly seen synonyms for mass fractions. Mass fraction or mass percent is the preferred nomenclature because it is independent of local gravity.

19.8.2 Atomic Fraction

19.8.3 Stoichiometry

Stoichiometry is closely related to atomic fraction. Many materials can be described simply in terms of the chemical formula of its most basic constituent unit. For example, silicon and oxygen combine to form a material in which the most basic repeating element consists of SiO2. Stoichiometry can be readily translated into atomic fraction. Since our measurements are imprecise, the stoichiometry rarely works out in clean integral units. However, the measurement is often precise enough to distinguish between two or more valence states.

19.8.4 Oxide Fractions

Oxide fractions are closely related to stoichiometry. When a material such as a natural mineral is a mixture of oxides, it can make sense to report the composition as a linear sum of the oxide constituents by mass fraction.

Three different ways to report the composition of NIST SRM 470 glass K412.

K412 Glass | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Element | Mg | Al | Si | Ca | Fe | O | Sum |

Valence | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | −2 | – |

Atomic weight (AMU) | 24.305 | 26.9815 | 28.085 | 40.078 | 55.845 | 15.999 | |

Oxide fraction | 0.1933 ± 0.0020 MgO | 0.0927 ± 0.0020 Al2O3 | 0.4535 ± 0.0020 Si02 | 0.1525 ± 0.0020 CaO | 0.0996 ± 0.0020 FeO | – | 0.9916 |

Mass fraction | 0.1166 | 0.0491 | 0 2120 | 0.1090 | 0.0774 | 0 4276 | 0.9916 |

Atomic fraction | 0.1066 | 0.0404 | 0.1678 | 0.0604 | 0.0308 | 0.5940 | 1 |

19.8.4.1 Example Calculations

19.9 The Accuracy of Quantitative Electron-Excited X-ray Microanalysis

19.9.1 Standards-Based k-ratio Protocol

![$$ \mathrm{RDEV}=\left[\frac{\left(\mathrm{Analyzed}\ \mathrm{value}-\mathrm{expected}\ \mathrm{value}\right)}{\mathrm{expected}\ \mathrm{value}}\right]\times 100\% $$](../images/271173_4_En_19_Chapter/271173_4_En_19_Chapter_TeX_Equ17.png)

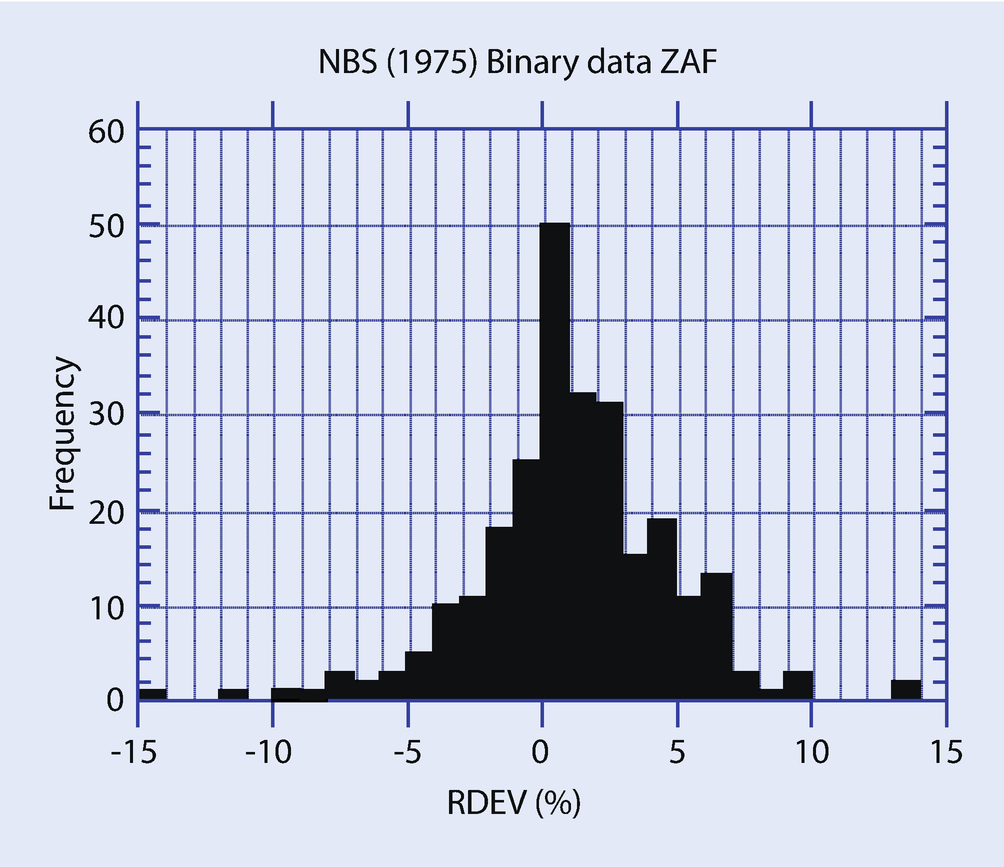

Histogram of relative deviation from expected value (relative error) for electron probe microanalysis with wavelength dispersive spectrometry following the k-ratio protocol with standards and ZAF corrections (Yakowitz 1975)

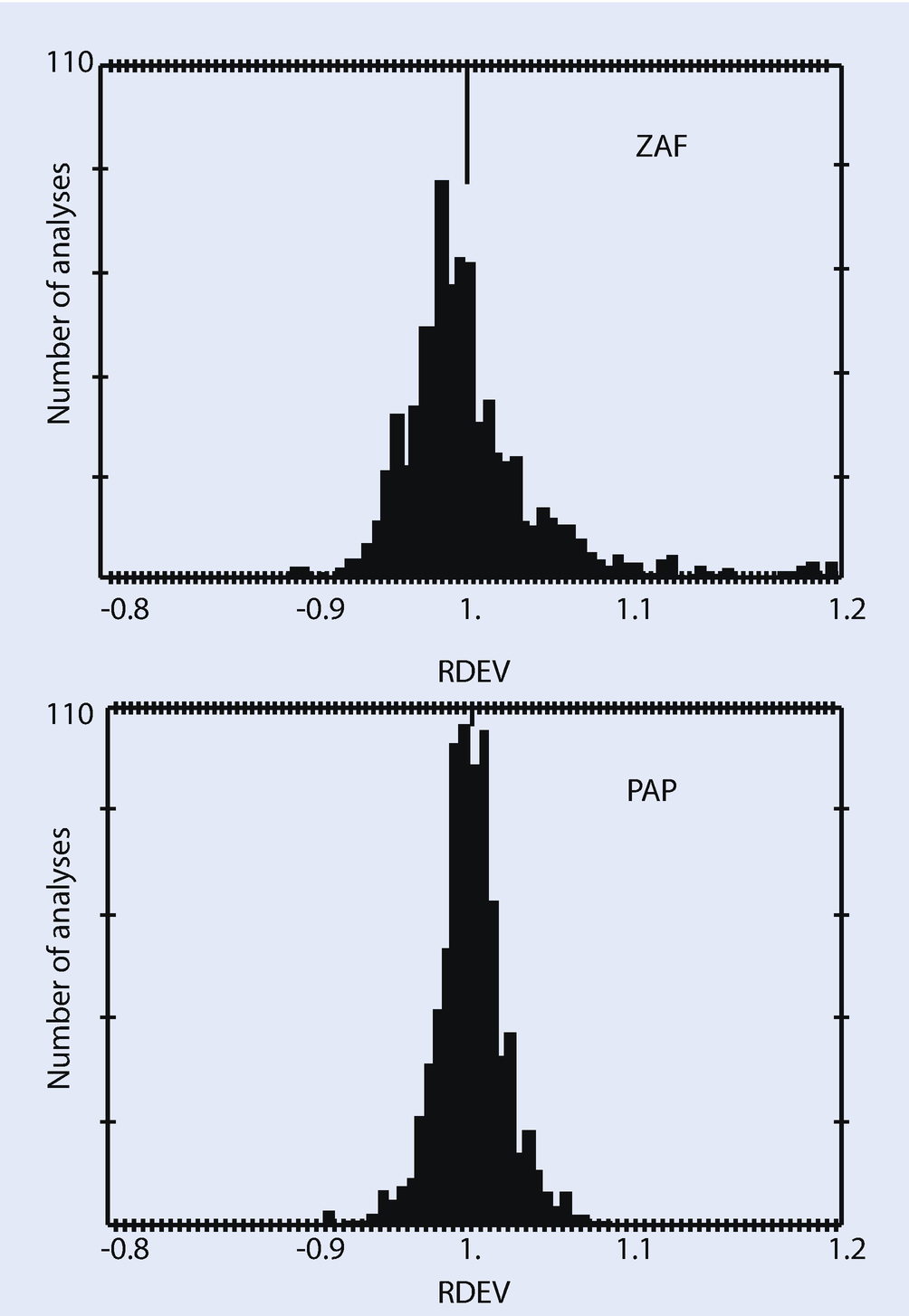

Comparison of quantitative analysis of an EPMA-WDS k = ratio database by conventional ZAF and by the PAP φ(ρz) model (Pouchou and Pichoir 1991)

► Chapter 20 will illustrate examples of quantitative electron-excited X-ray microanalysis with silicon drift detector (SDD)-EDS performed on flat bulk specimens following the k-ratio protocol and PAP φ(ρz) matrix corrections with NIST DTSA-II. The level of accuracy achieved with this SDD-EDS approach fits within the RDEV histogram achieved with EPMA-WDS for major, minor, and trace constituents, even when severe peak interference occurs. It should be noted that SDD-EDS is sufficiently stable with time that, providing a quality measurement protocol is in place to ensure that all measurements are made under identical conditions of beam energy, known dose, specimen orientation, and SDD-EDS performance, archived standards can be used without significant loss of accuracy.

19.9.2 “Standardless Analysis”

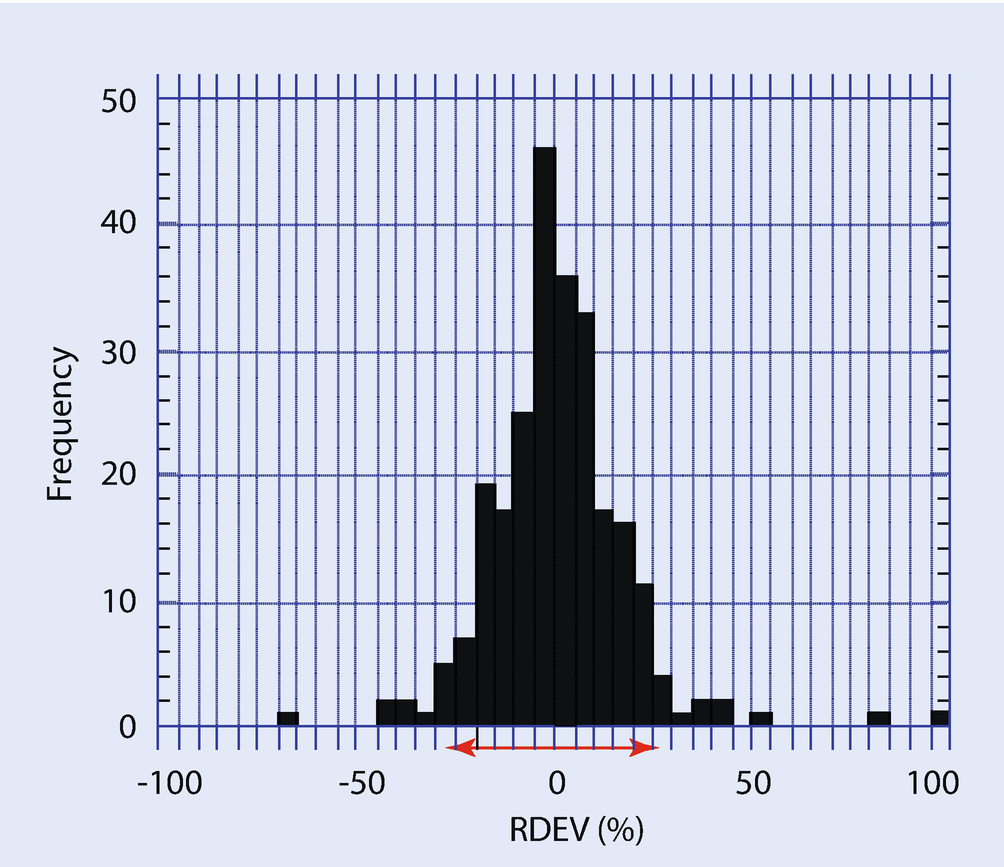

RDEV distribution observed for a vendor standardless analysis procedure (Newbury et al. 1995)

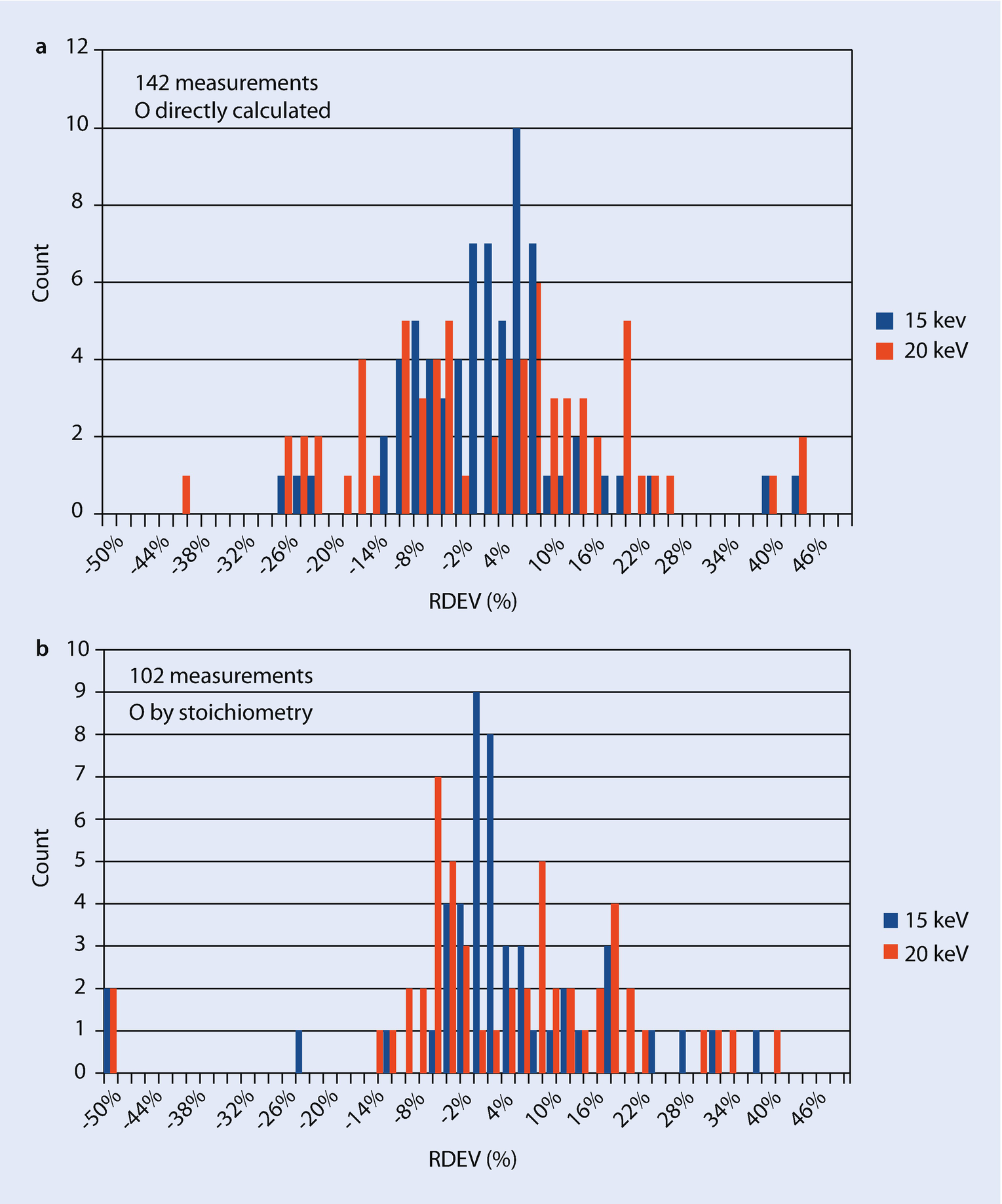

a RDEV distribution observed for a vendor standardless analysis procedures in 2016 with oxygen calculated directly for oxidized specimens. b RDEV distribution observed for a vendor standardless analysis procedures in 2016 with oxygen calculated by stoichiometry for oxidized specimens

SEM-EDS analysis of a YBa2Cu3O7-x single crystal (O calculated by stoichiometry)

Y (true) 0.133 mass conc | Ba (true) 0.412 | Cu (true) 0.286 | |

|---|---|---|---|

k-ratio Stds ZAF | 0.138 (+4 %) | 0.411 (−0.2 %) | 0.281 (−2 %) Cu-K Y1Ba2Cu3O6.4 |

Standards: Y and Cu pure elements; Ba (NIST glass K309) | |||

Standardless Analysis (two different vendors): | |||

M1 | 0.173 (+30 %) | 0.400 (−3 %) | 0.267 (−7 %) Cu-K Y2Ba3Cu4O10 |

M1 | 0.158 (+19 %) | 0.362 (−12 %) | 0.316 (+10 %) Cu-L Y2Ba3Cu6O12 |

M2 | 0.165 (+24 %) | 0.387 (−6 %) | 0.287 (+0.4 %) Cu-K Y2Ba3Cu5O11 |

M2 | 0.168 (+26 %) | 0.395 (−4 %) | 0.276 (−3.5 %) Cu-L Y4Ba6Cu9O21 |

Another shortcoming of standardless analysis is the loss of the information on the dose and the absolute spectrometer efficiency that is automatically embedded in the standards-based k-ratio/matrix corrections protocol. Without the dose and absolute spectrometer efficiency information, standardless analysis results must inevitably be internally normalized to unity (100 %) so that the calculated concentrations have realistic meaning, thereby losing the very useful information present in the raw analytical total that is available in the standards-based k-ratio/matrix corrections protocol. It must be noted that standardless analysis results will always sum to unity, even if one or more constituents are not recognized during qualitative analysis or are inadvertently lost from the suite of elements being analyzed. If the local dose and spectrometer efficiency can be accurately scaled to the conditions used to record remote standards, then standardless analysis can determine a meaningful analytical total, but this is not commonly implemented in vendor software.

19.10 Appendix

19.10.1 The Need for Matrix Corrections To Achieve Quantitative Analysis

There has long been confusion around the definition of the expression ‘ZAF’ used to compensate for material differences in X-ray microanalysis measurements. There are two competing definitions. Neither is wrong and both exist in the literature and implemented in microanalysis software. However, the two definitions lead to numerical values of the matrix corrections that are related by being numerical inverses of each other.

For the sake of argument, let’s call these two definitions ZAF

A and ZAF

B. In both definitions,  and C

unk is the mass fraction of the element in the unknown.

and C

unk is the mass fraction of the element in the unknown.

The confusion extends to this book. Most of this book has been written using the first convention (ZAF

A) however, the previous (third) edition of this book used the second convention (ZAF

B). The following section which has been pulled from the third edition continues to use the ZAF

B convention as this was the definition favored by the writer. NIST DTSA-II and CITZAF uses the  convention.

convention.

(Contribution of the late Prof. Joseph Goldstein taken from SEMXM-3, ► Chapter 9)

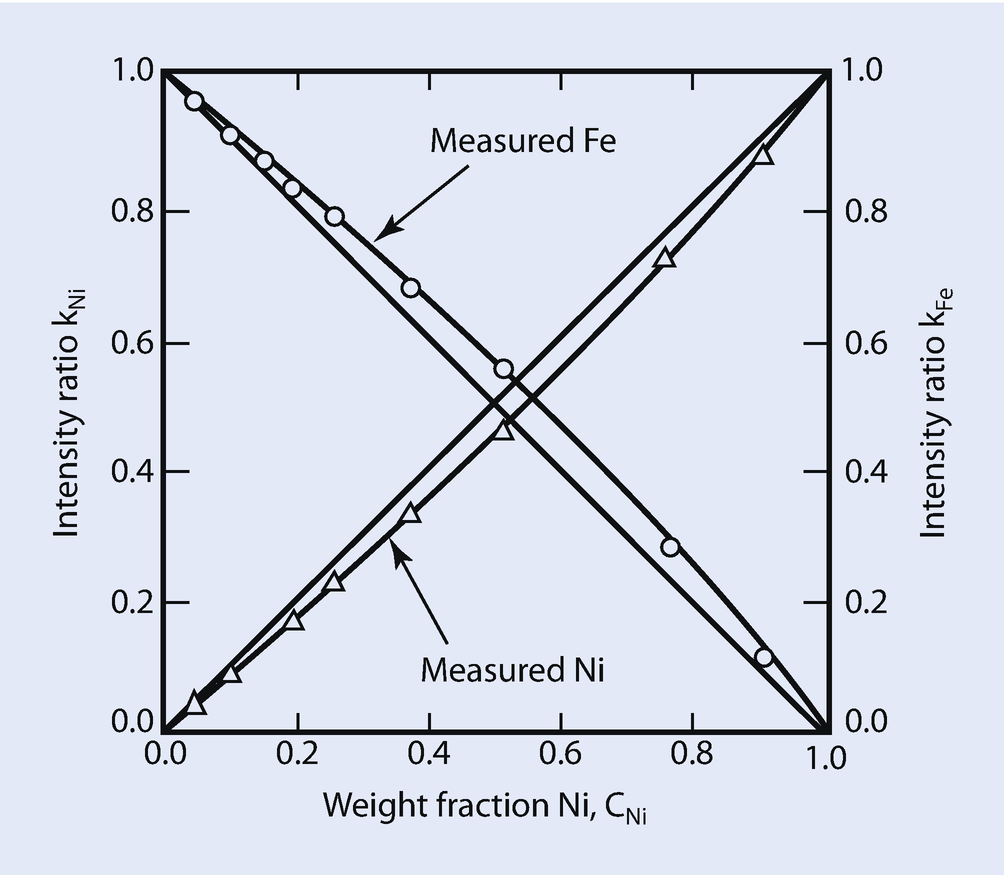

Measured Fe K-L3 and Ni K-L3 k-ratios versus the weight fraction of Ni at E 0 = 30 keV. Curves are measured k-ratio data, while straight lines represent ideal behavior (i.e., no matrix effects)

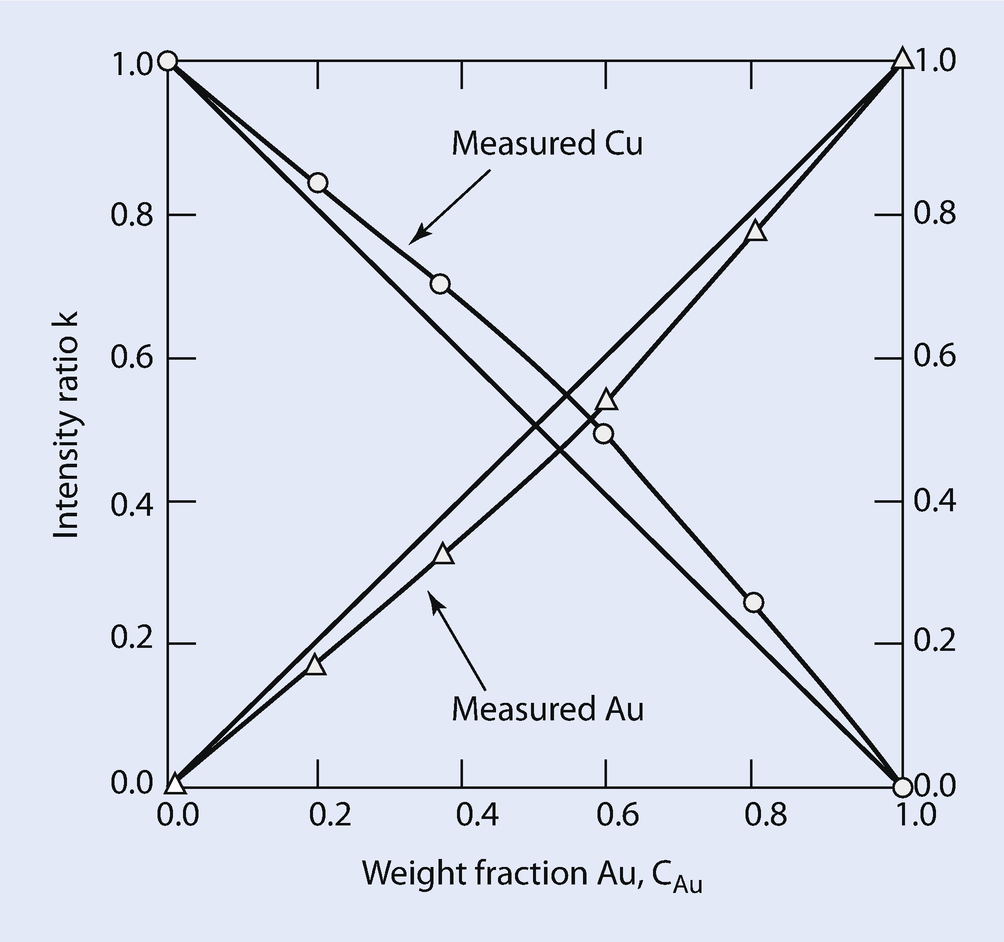

These effects that cause deviations from the simple linear behavior given by Eq. (19.16) are referred to as matrix or inter-element effects. As described in the following sections, the measured intensities from specimen and standard need to be corrected for differences in electron backscatter and energy loss, X-ray absorption along the path through the solid to reach the detector, and secondary X-ray generation and emission that follows absorption, in order to arrive at the ratio of generated intensities and hence the value of C i,unk. The magnitude of the matrix effects can be quite large, exceeding factors of ten or more in certain systems. Recognition of the complexity of the problem of the analysis of solid samples has led numerous investigators to develop the theoretical treatment of the quantitative analysis scheme, first proposed by Castaing (1951).

19.10.2 The Physical Origin of Matrix Effects

What is the origin of these matrix effects? The X-ray intensity generated for each element in the specimen is proportional to the concentration of that element, the probability of X-ray production (ionization cross section) for that element, the path length of the electrons in the specimen, and the fraction of incident electrons which remain in the specimen and are not backscattered. It is very difficult to calculate the absolute generated intensity for the elements present in a specimen directly. Moreover, the intensity that the analyst must deal with is the measured intensity. The measured intensity is even more difficult to calculate, particularly because absorption and fluorescence of the generated X-rays may occur in the specimen, thus further modifying the measured X-ray intensity from that predicted on the basis of the ionization cross section alone. Instrumental factors such as differing spectrometer efficiency as a function of X-ray energy must also be considered. Many of these factors are dependent on the atomic species involved. Thus, in mixtures of elements, matrix effects arise because of differences in elastic and inelastic scattering processes and in the propagation of X-rays through the specimen to reach the detector. For conceptual as well as calculational reasons, it is convenient to divide the matrix effects into atomic number, Z i; X-ray absorption, A i; and X-ray fluorescence, F i, effects.

![$$ {C}_{\mathrm{i},\mathrm{unk}}/{C}_{\mathrm{i},\mathrm{std}}=={\left[\mathrm{ZAF}\right]}_{\mathrm{i}}\left[{\mathrm{I}}_{\mathrm{i},\mathrm{unk}}/{\mathrm{I}}_{\mathrm{i},\mathrm{std}}\right]={\left[ ZAF\right]}_{\mathrm{i}}.{k}_{\mathrm{i}} $$](../images/271173_4_En_19_Chapter/271173_4_En_19_Chapter_TeX_Equ19.png)

It is important for the analyst to develop a good idea of the origin and the importance of each of the three major non-linear effects on X-ray measurement for quantitative analysis of a large range of specimens.

19.10.3 ZAF Factors in Microanalysis

The matrix effects Z, A, and F all contribute to the correction for X-ray analysis as given in Eq. (19.17). This section discusses each of the matrix effects individually. The combined effect of ZAF determines the total matrix correction.

19.10.3.1 Atomic Number Effect, Z (Effect of Backscattering [R] and Energy Loss [S])

One approach to the atomic number effect is to consider directly the two different factors, backscattering (R) and stopping power (S), which determine the amount of generated X-ray intensity in an unknown. Dividing the stopping power, S, for the unknown and standard by the backscattering term, R, for the unknown and standard yields the atomic number matrix factor, Z i, for each element, i, in the unknown. A discussion of the R and S factors follows.

Backscattering, R: The process of elastic scattering in a solid sample leads to backscattering which results in the premature loss of a significant fraction of the beam electrons from the target before all of the ionizing power of those electrons has been expended generating X-rays of the various elemental constituents. From ◘ Fig. 2.3a, which depicts the backscattering coefficient as a function of atomic number, this effect is seen to be strong, particularly if the elements involved in the unknown and standard have widely differing atomic numbers. For example, consider the analysis of a minor constituent, for example, 1 weight %, of aluminum in gold, against a pure aluminum standard. In the aluminum standard, the backscattering coefficient is about 15 % at a beam energy of 20 keV, while for gold the value is about 50 %. When aluminum is measured as a standard, about 85 % of the beam electrons completely expend their energy in the target, making the maximum amount of Al K-L3 X-rays. In gold, only 50 % are stopped in the target, so by this effect, aluminum dispersed in gold is actually under represented in the X-rays generated in the specimen relative to the pure aluminum standard. The energy distribution of backscattered electrons further exacerbates this effect. Not only are more electrons backscattered from high atomic number targets, but as shown in ◘ Fig. 2.16a, b, the backscattered electrons from high atomic number targets carry off a higher fraction of their incident energy, further reducing the energy available for ionization of inner shells. The integrated effects of backscattering and the backscattered electron energy distribution form the basis of the “R-factor” in the atomic number correction of the “ZAF” formulation of matrix corrections.

Stopping power, S: The rate of energy loss due to inelastic scattering also depends strongly on the atomic number. For quantitative X-ray calculations, the concept of the stopping power, S, of the target is used. S is the rate of energy loss given by the Bethe continuous energy loss approximation, Eq. (1.1), divided by the density, ρ, giving S = − (1/ρ)(dE/ds). Using the Bethe formulation for the rate of energy loss (dE/ds), one observes that the stopping power is a decreasing function of atomic number. The low atomic number targets actually remove energy from the beam electron more rapidly with mass depth (ρz), the product of the density of the sample (ρ), and the depth dimension (z) than high atomic number targets.

Measured Au L3-M5 and Cu K-L3 k-ratios versus the weight fraction of Au at E 0 = 25 keV. Curves are measured k-ratio data, while straight lines represent ideal behavior (i.e., no matrix effects)

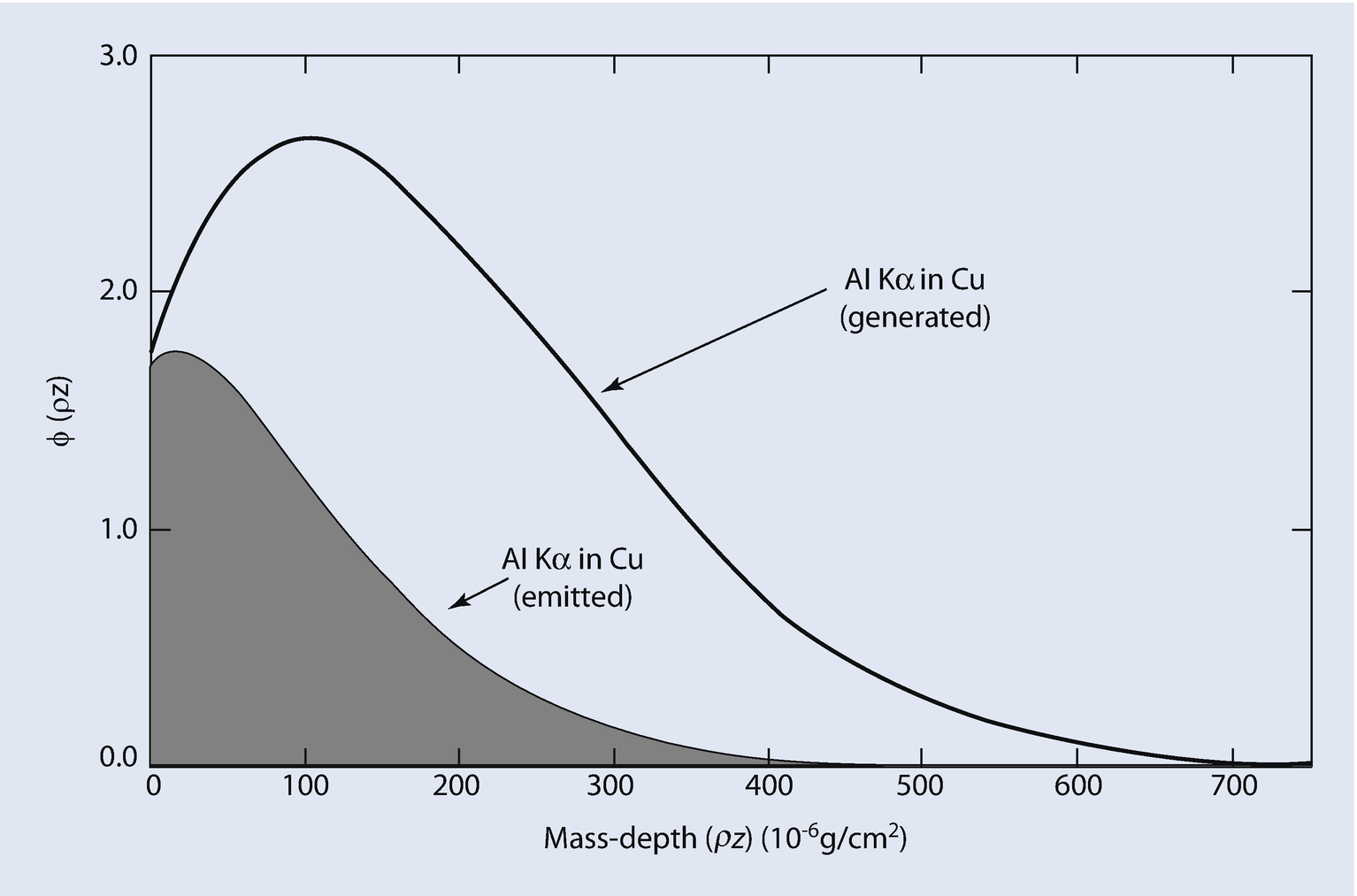

X-ray Generation With Depth, φ(ρz)

A second approach to calculating the atomic number effect is to determine the X-ray generation in depth as a function of atomic number and electron beam energy. As shown in ► Chapters 1, 2, and 4, the paths of beam electrons within the specimen can be represented by Monte Carlo simulations of electron trajectories. In the Monte Carlo simulation technique, the detailed history of an electron trajectory is calculated in a stepwise manner. At each point along the trajectory, both elastic and inelastic scattering events can occur. The production of characteristic X-rays, an inelastic scattering process, can occur along the path of an electron as long as the energy E of the electron is above the critical excitation energy, E c, of the characteristic X-ray of interest.

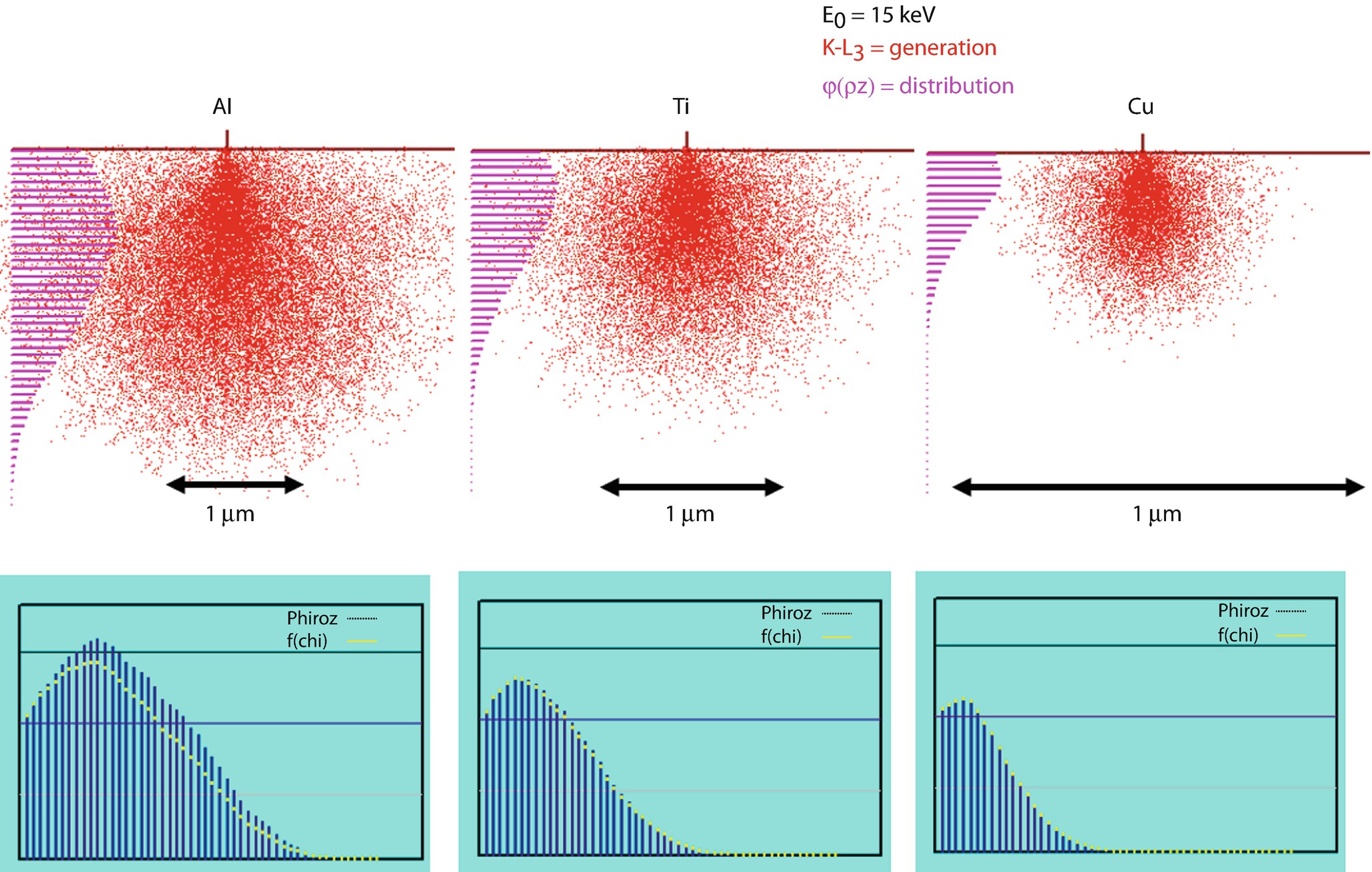

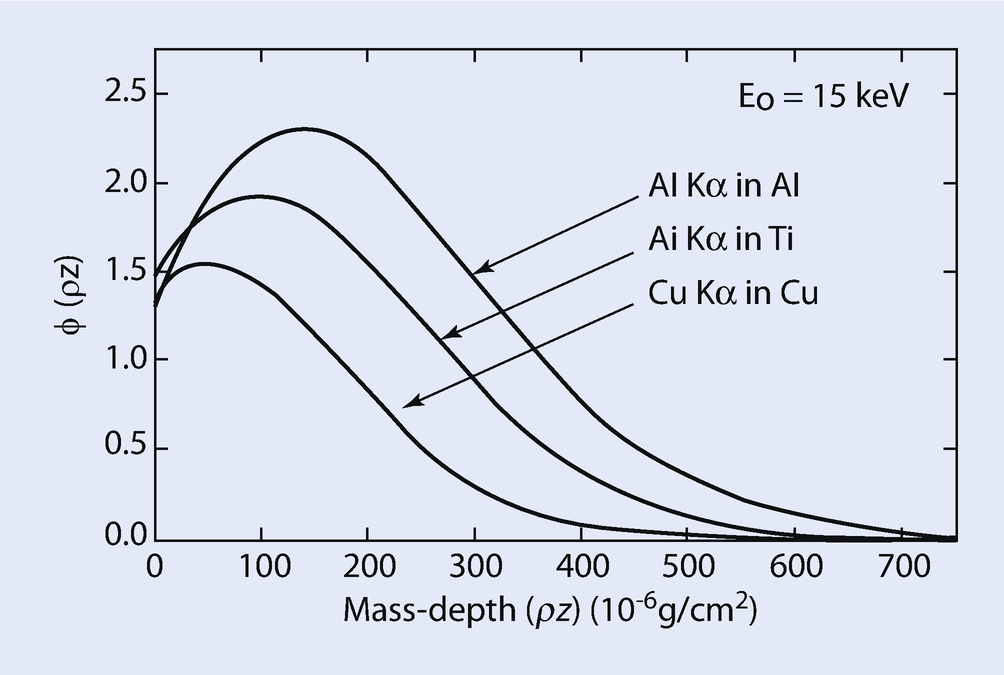

Monte Carlo simulations (Joy Monte Carlo) of X-ray generation at E 0 = 15 keV for Al K-L3, Ti K-L3, and Cu K-L3, showing (upper) the sites of X-ray generation (red dots) projected on the x-z plane, and the resulting φ(ρz) distribution. (lower) the φ(ρz) distribution is plotted with the associated f(χ) distribution showing the escape of X-rays following absorption

One can observe from ◘ Fig. 19.7 that there is a non-even distribution of X-ray generation with depth, z, for specimens with various atomic numbers and initial electron beam energies. This variation is illustrated by the histograms on the left side of the Monte Carlo simulations. These histograms plot the number of X-rays generated with depth into the specimen. In detail the X-ray generation for most specimens is somewhat higher just below the surface of the specimen and decreases to zero when the electron energy, E, falls below the critical excitation energy, E c, of the characteristic X-ray of interest.

As illustrated from the Monte Carlo simulations, the atomic number of the specimen strongly affects the distribution of X-rays generated in specimens. These effects are even more complex when considering more interesting multi-element samples as well as the generation of L and M shell X-ray radiation.

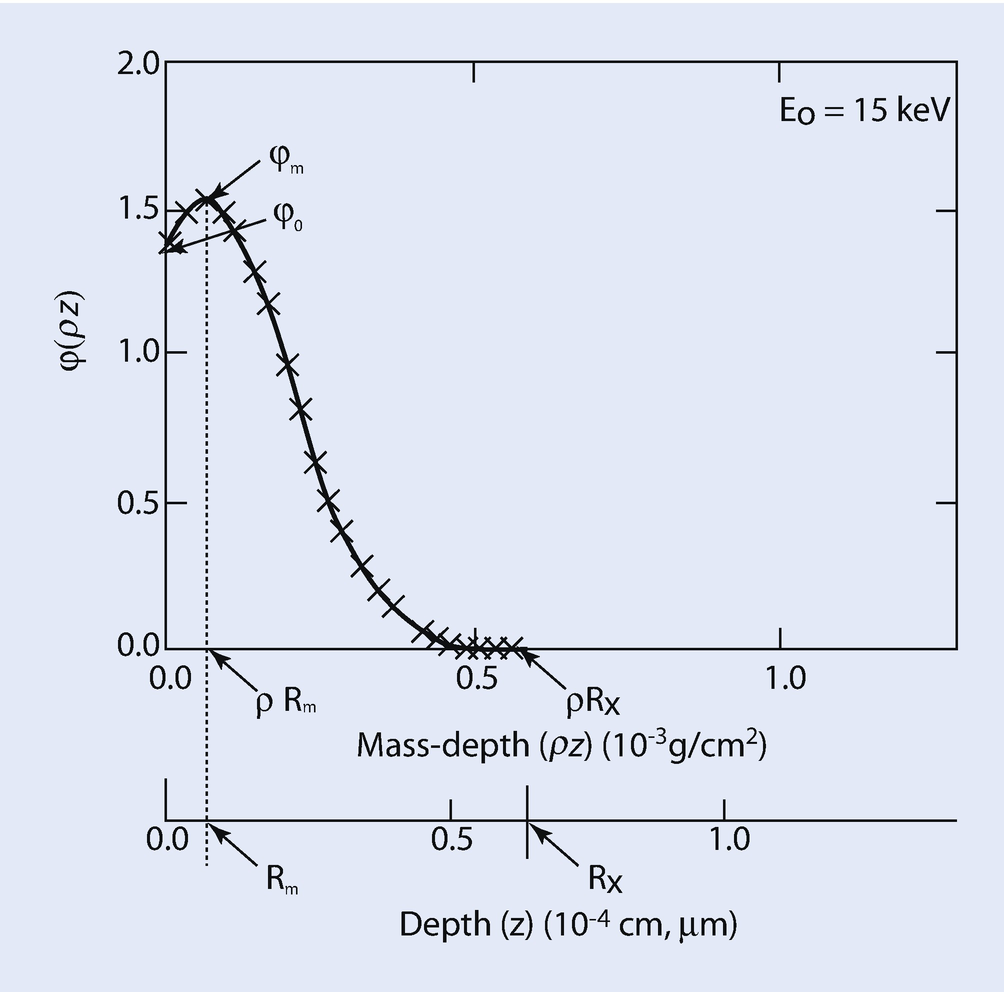

◘ Figure 19.7 clearly shows that X-ray generation varies with depth as well as with specimen atomic number. In practice it is very difficult to measure or calculate an absolute value for the X-ray intensity generated with depth. Therefore, we follow the practice first suggested by Castaing (1951) of using a relative or a normalized generated intensity which varies with depth, called φ (ρz). The term ρz is called the mass depth and is the product of the density ρ of the sample (g/cm3) and the linear depth dimension, z (cm), so that the product ρz has units of g/cm2. The mass depth, ρz, is more commonly used than the depth term, z. The use of the mass depth removes the strong variable of density when comparing specimens of different atomic number. Therefore it is important to recognize the difference between the two terms as the discussion of X-ray generation proceeds.

Schematic illustration of the φ(ρz) depth distribution of X-ray generation, with the definitions of specific terms: φ 0, φ m, ρR m, R m, ρR X, and R X

Calculated φ(ρz) curves for Al K-L3 in Al; Ti K-L3 in Ti; and Cu K-L3 in Cu at E 0 = 15 keV; calculated using PROZA

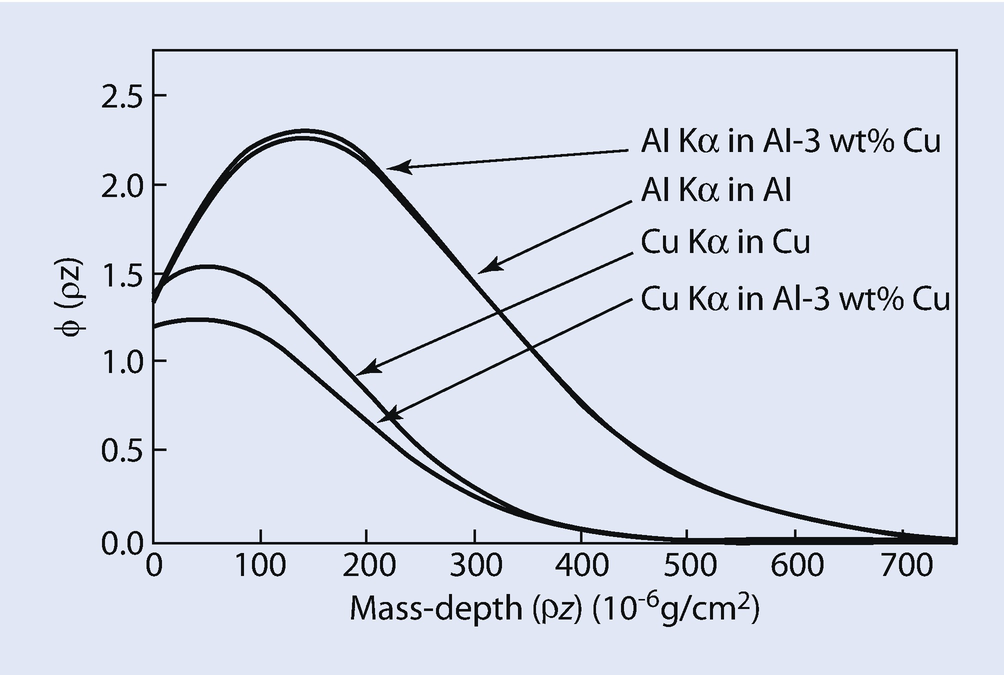

Calculated φ(ρz) curves for Al K-L3 and Cu K-L3 in Al, Cu, and Al-3wt%Cu at E 0 = 15 keV; calculated using PROZA

Sample | X-ray | φ(ρz)i,gen Area (cm2/g) | Atomic number factor, Zi | φ 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cu | Cu K-L3 | 3.34 × 10−4 | 1.0 | 1.39 |

Al | Al K-L3 | 7.85 × 10−4 | 1.0 | 1.33 |

Al-3wt%Cu | Cu K-L3 | 2.76 × 10−4 | 0.826 | 1.20 |

Al-3wt%Cu | Al K-L3 | 7.89 × 10−4 | 1.005 | 1.34 |

The atomic number correction, Z i, can be calculated by taking the ratio of φ(ρz) i,gen Area for the standard to φ(ρz) i,gen Area for element i in the specimen. Pure Cu and pure Al are the standards for Cu K-L3 and Al K-L3 respectively. The values of the calculated ratios of generated X-ray intensities, pure element standard to specimen (Atomic number effect, Z Al, Z Cu) are also given in ◘ Table 19.3 As discussed above, it is expected that the atomic number correction for a heavy element (Cu) in a light element matrix (Al – 3 wt % Cu) is less than 1.0 and the atomic number correction for a light element (Al) in a heavy element matrix (Al – 3 wt % Cu) is greater than 1.0. The calculated data in ◘ Table 19.3 also show this relationship.

In summary, the atomic number matrix correction, Z i, is equal to the ratio of Z i,std in the standard to Z i,unk in the unknown. Using appropriate φ(ρz) curves, correction Z i can be calculated by taking the ratio of I gen,std for the standard to I gen,unk for the unknown for each element, i, in the sample. It is important to note that the φ(ρz) curves for multi-element samples and elemental standards which can be used for the calculation of the atomic number effect inherently contain the R and S factors discussed previously.

19.10.3.2 X-ray Absorption Effect, A

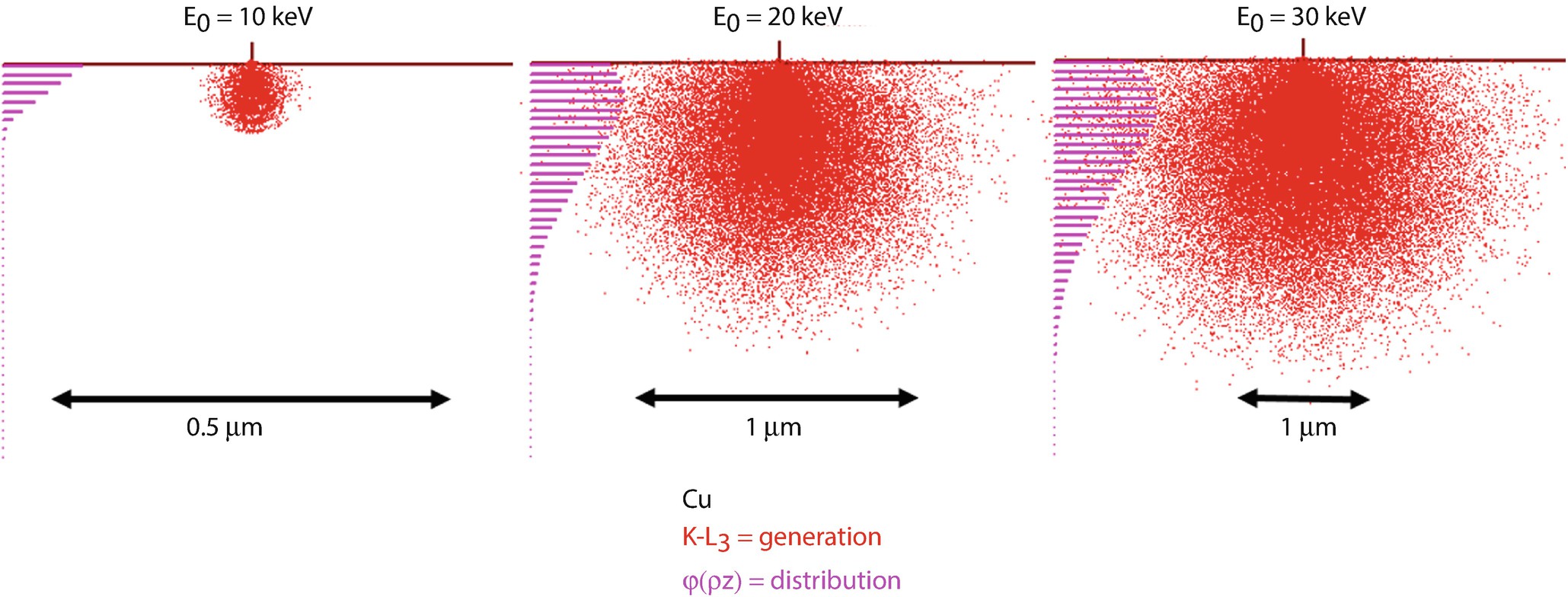

Monte Carlo simulations (Joy Monte Carlo) of the X-ray generation volume for Cu K-L3at E 0 = 10 keV, 20 keV and 30 keV. The sites of X-ray generation (red dots) are projected on the x-z plane, and the resulting φ(ρz) distribution is shown

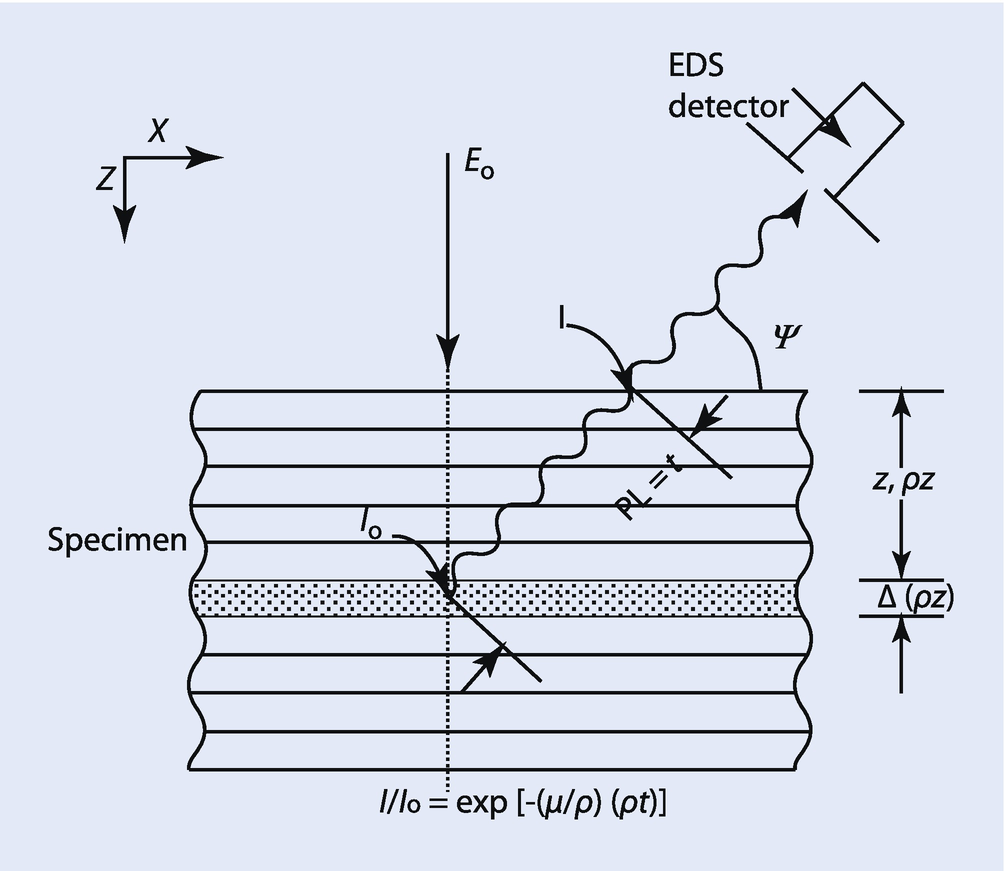

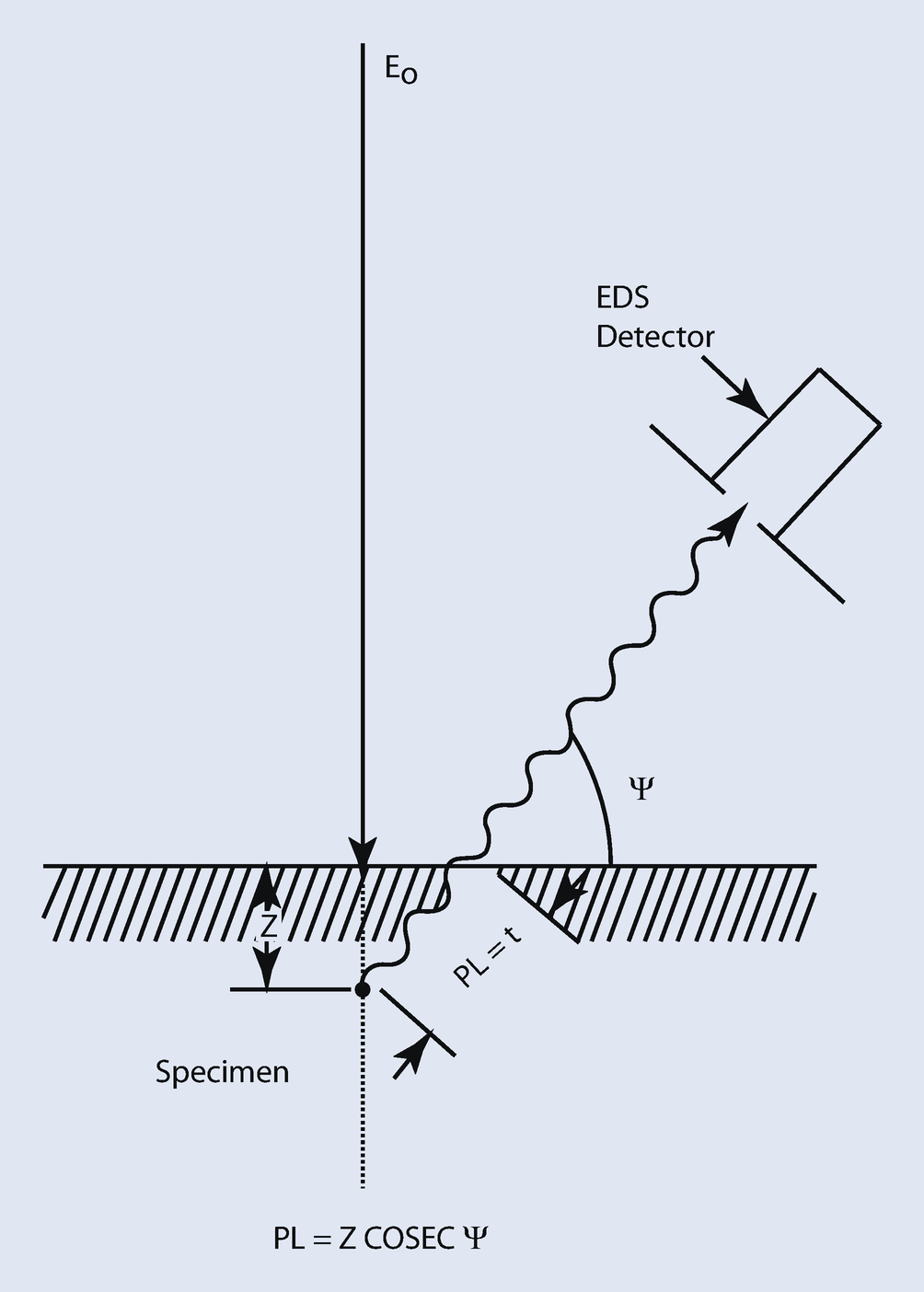

Created over a range of depth, the X-rays will have to pass through a certain amount of matter to reach the detector, and as explained in ► Chapter 4 (X-rays), the photoelectric absorption process will decrease the intensity. It is important to realize that the X-ray photons are either absorbed or else they pass through the specimen with their original energy unchanged, so that they are still characteristic of the atoms which emitted the X-rays. Absorption follows an exponential law, so as X-rays are generated deeper in the specimen, a progressively greater fraction is lost to absorption.

Calculated φ(ρz) curves for Cu K-L3 in Cu at E 0 = 10 keV, 20 keV, and 30 keV; calculated using PROZA

![$$ I/{I}_0=\exp \left[-\left(\mu /\rho \right)\left(\rho t\right)\right] $$](../images/271173_4_En_19_Chapter/271173_4_En_19_Chapter_TeX_Equ20.png)

Schematic diagram of absorption in the measurement or calculation of the φ(ρz) curve for emitted X-rays. PL = path length, ψ = X-ray take-off angle (detector elevation angle above surface)

Calculated generated and emitted φ(ρz) curves for Al K-L3 in a Cu matrix at E 0 = 20 keV

X-ray absorption is usually the largest correction factor that must be considered in the measurement of elemental composition by electron-excited X-ray microanalysis. For a given X-ray path length, the mass absorption coefficient, (μ/ρ), for each measured characteristic X-ray peak controls the amount of absorption. The value of (μ/ρ) varies greatly from one X-ray to another and is dependent on the matrix elements of the specimen (see ► Chapter 4, “X-rays”). For example, the mass absorption coefficient for Fe K-L3 radiation in Ni is 90.0 cm2/g, while the mass absorption coefficient for Al K-L3 radiation in Ni is 4837 cm2/g. Using Eq. (19.18) and a nominal path length of 1 μm in a Ni sample containing small amounts of Fe and Al, the ratio of X-rays emitted at the sample surface to the X-rays generated in the sample, I/I0, is 0.923 for Fe K-L3 radiation but only 0.0135 for Al K-L3 radiation. In this example, Al K-L3 radiation is very heavily absorbed with respect to Fe K-L3 radiation in the Ni sample. Such a large amount of absorption must be taken account of in any quantitative X-ray analysis scheme. Even more serious effects of absorption occur when considering the measurement of the light elements, for example, Be, B, C, N, O, and so on. For example, the mass absorption coefficient for C K-L radiation in Ni is 17,270 cm2/g, so large that in most practical analyses, no C K-L radiation can be measured if the absorption path length is 1 μm. Significant amounts of C K-L radiation can only be measured in a Ni sample within 0.1 μm of the surface. In such an analysis situation, the initial electron beam energy should be held below 10 keV so that the C K-L X-ray source is produced close to the sample surface.

Schematic diagram showing the X-ray absorption path length in a thick, flat-polished sample: PL = absorption path length; ψ = X-ray take-off angle (detector elevation angle above surface)

Path Length, PL, for Al K-L3 X-rays in Al

E 0 | Take-Off Angle, ψ | R x (μm) | Path Length, PL, (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

10 | 15 | 0.3 | 1.16 |

10 | 60 | 0.3 | 0.35 |

30 | 15 | 2.0 | 7.7 |

30 | 60 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

The variation in PL is larger than a factor of 20, from 0.35 μm at the lowest keV and highest take-off angle to 7.7 μm at the highest keV and lowest take-off angle. Clearly the analyst’s choices of the initial electron beam energy and the X-ray take-off angle have a major effect on the path length and therefore the amount of absorption that occurs.

In summary, using appropriate formulations for X-ray generation with depth or φ(ρz) curves, the effect of absorption can be obtained by considering absorption of X-rays from element i as they leave the sample. The absorption correction, Ai, can be calculated by taking the ratio of the effect of absorption for the standard, A i,std, to X-ray absorption for the unknown, A i,unk, for each element, i, in the sample. The effect of absorption can be minimized by decreasing the path length of the X-rays in the specimen through careful choice of the initial beam energy and by selecting, when possible, a high take-off angle.

19.10.3.3 X-ray Fluorescence, F

Photoelectric absorption results in the ionization of inner atomic shells, and those ionizations can also cause the emission of characteristic X-rays. For fluorescence to occur, an atom species must be present in the target which has a critical excitation energy less than the energy of the characteristic X-rays being absorbed. In such a case, the measured X-ray intensity from this second element will include both the direct electron-excited intensity as well as the additional intensity generated by the fluorescence effect. Generally, the fluorescence effect can be ignored unless the photon energy is less than 5 keV greater than the critical excitation energy, E c.

The significance of the fluorescence correction, F i, can be illustrated by considering the binary system Fe-Ni. In this system, the Ni K-L3 characteristic energy at 7.478 keV is greater than the energy for excitation of Fe K radiation, E c = 7.11 keV. Therefore, an additional amount of Fe K-L3 radiation is produced beyond that due to the direct beam on Fe. ◘ Figure 19.5 shows the effect of fluorescence in the Fe-Ni system at an initial electron beam energy of 30 keV and a take-off angle, ψ, of 52.5°. Under these conditions, the atomic number effect, Z Fe, and the absorption effect, AFe, for Fe K-L3 are very close to 1.0. The measured kFe ratio lies well above the first approximation straight line relationship. The additional intensity is given by the effect of fluorescence. As an example, for a 10 wt% Fe – 90 wt% Ni alloy, the amount of iron fluorescence is about 25 %.

The quantitative calculation of the fluorescence effect requires a knowledge of the depth distribution over which the characteristic X-rays are absorbed. The φ(ρz) curve of electron-generated X-rays is the starting point for the fluorescence calculation, and a new φ(ρz) curve for X-ray-generated X-rays is determined. The electron-generated X-rays are emitted isotropically. From the X-ray intensity generated in each of the layers Δ(ρz) of the φ(ρz) distribution, the calculation next considers the propagation of that radiation over a spherical volume centered on the depth ρz of that layer, calculating the absorption based on the radial distance from the starting layer and determining the contributions of absorption to each layer (ρz) in the X-ray-induced φ(ρz) distribution. Because of the longer range of X-rays than electrons in materials, the X-ray-induced φ(ρz) distribution covers a much greater depth, generally an order of magnitude or more than the electron-induced φ(ρz) distribution. Once the X-ray-induced φ(ρz) generated distribution is determined, the absorption of the outgoing X-ray-induced fluorescence X-rays must be calculated with the absorption path length calculated as above.

The fluorescence factor, F i, is usually the least important factor in the calculation of composition by evaluating the [ZAF] term in Eq. (19.17). In most analytical cases secondary fluorescence may not occur or the concentration of the element which causes fluorescence may be small. Of the three effects, Z, A, and F, which control X-ray microanalysis calculations, the fluorescence effect, F i, can be calculated (Reed 1965), with sufficient accuracy so that it rarely limits the development of an accurate analysis.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.