Most papers, articles, and books on risk management are primarily centered on techniques. This book is no exception, as will be apparent in the next chapters. However, before we get to the techniques, we would like to take a microeconomic point of view and highlight the definition of a bank, as well as the nature of the relationship between banks and industrial firms. These are best described in a microeconomic framework.

The increasing breadth of credit markets in most advanced economies has reduced the role of banking intermediation. The trend toward market-based finance appears to be very strong and even calls into question the reason for having banks. The objective of this chapter is to analyze the underlying microeconomics in order to better understand this change and its consequences and to identify the value brought by banks to the economy. This analysis will help us to better grasp the characteristics of the optimal behavior of banks in a market environment. This will prove particularly valuable when dealing with bank risk management.

At the outset, it is important to mention that the definition of the banking firm, according to microeconomic theory, is a rather narrow one, corresponding more to commercial banking than to investment banking: A bank basically receives deposits and lends money. Loans are not assumed to be tradable in debt markets. In this respect an investment bank that tends to offer services linked with market activities (securities issuance, asset management, etc.) is not considered a bank, but is simply included in the financial markets environment. Other important financial intermediaries such as institutional investors (insurance companies, pension funds, etc.) and rating agencies (acting as delegated monitors) are not yet as well identified. These categories of participants should find a better place in financial theory, in conjunction with their increased role.

According to microeconomic principles, the rationale for the existence of banks is linked with the absence of Walrasian financial markets,1 providing full efficiency and completeness. Such absence can result from either asymmetric information on industrial projects, incompleteness of contracts, or incompleteness of markets.2 A Walrasian economy is necessary for financial markets to provide Pareto optimal3 adjustments between supply of and demand for money. The “real-world” economy cannot be qualified as Walrasian.

Following Merton’s (1995) approach,4 a bank should be defined by the missions it fulfills for the benefit of the economy. This analysis is shared by many significant contributors to banking theory.5 A bank is described as the institution, or to rephrase it in microeconomic wording, as the most adequate—Pareto optimal—coalition of individual agents, able to perform three major intermediation functions6: liquidity intermediation, risk intermediation, and information intermediation.

1. The liquidity intermediation function is the most obvious one. It consists of reallocating all the money in excess, saved by depositors, in order to finance companies short of cash and expanding through long-term investment plans. This “asset transformation” activity reconciles the preference for liquidity of savers with the long-term maturity of capital expenditures.

2. The risk intermediation function corresponds to all operations whereby a bank collects risks from the economy (credit, market, foreign exchange, interest rate risks, etc.) and reengineers them for the benefit of all economic agents. The growing securitization activity, whereby a bank repackages risks and resells them in the market through new securities with varying degrees of risk, falls into this category.

3. The information intermediation function is particularly significant whenever there is some asymmetric information between an entrepreneur (who has better information about the riskiness of his project) and the uninformed savers and investors from whom he is seeking financing. Since the seminal article by Diamond (1984), banks have been considered as delegated monitors. They are seen as able to operate for the benefit of the community of investors in order to set mechanisms for information revelation. Moral hazard and adverse selection7 can be tackled by them.

To summarize, banks exist because they fulfill intermediation services and fill in gaps in financial markets.

In addition, in a theoretical perfect economy, agents should be indifferent between the two major sources of funding: equity and debt (Modigliani and Miller, 1958). One could then argue that equity raised on financial markets should be sufficient for financing corporations and that bank lending should not be absolutely required. However, just like banking theory, financial theory accounts for the existence of both debt and equity because of imperfect financial markets where there is asymmetric information, incomplete contracts, or frictions such as taxes. With the existence of these different financial products, banks have found a very important role, focusing particularly on the lending business. One of their main characteristics (and a competitive advantage of banks) is that they are focused on debt management. They are in fact the only type of financial institution that manages debt both as resources (through either deposits that are debt-like contracts or money raised on financial markets) and as assets, with loans customized to requirements.

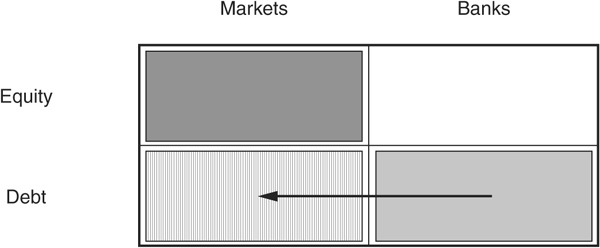

Credit disintermediation has a very strong momentum, and the traditional segregation between debt and equity as well as between the banking firm and financial markets tends to evolve quickly (see Figure 1-1). The main reason behind these dynamics is the increasing level of efficiency of markets.

FIGURE 1-1

The Trend Toward Disintermediation

In the following section of this chapter, we first look at the theory of the firm in order to identify the drivers of capital structure, as well as the role of debt and equity. This review of the microeconomics of the firm helps us to better understand major pitfalls and risk mitigation requirements related to providing external funding. A snapshot of the theory of financial contracts in particular will enable us to properly identify where the added value of the banking industry lies. We then briefly review the theory of the banking firm in order to show more precisely how banks can be a good alternative to markets for debt allocation to companies.

The financial world is generally supposed to be subordinated to the “real economy.” It provides support to companies that produce goods and services and thus contributes to increased global welfare. Credit markets evolve according to the funding choices of corporate firms.

In making financial decisions, a firm should seek to maximize its value. When the owner and the manager of the company are the same, then maximization of the value of the firm corresponds to maximizing the manager’s wealth. But when a manager and various investors share the profits of the firm, the various parties tend to seek their own interest.8 As the firm is not a perfect market, there is no pricing system that solves conflicts of interest and internal tensions. There is no a priori rationale to ensure that the balancing of individual interests leads to the maximization of the value of the firm. This explains why modern corporate finance theory measures the quality of the capital structure of the firm based on the appropriateness of the financial instruments used9: The relevant capital structure should induce agents in control of the firm to maximize its value. This approach is not consistent with the Modigliani-Miller (1958) setting in which the choice of the financial structure of the firm has no bearing on its value.10 The Modigliani-Miller theorem breaks down because a very important assumption about perfect markets is not fulfilled in practice: the transparency of information.

The funding of a given project will in general be supplied not only by the cash flows of the company, but also by additional debt or equity. Debt and equity offer very different payoff patterns, which trigger different behaviors by the claim holders. More precisely, the equity holder has a convex profile (of payoff as a function of the value of the firm), and the debt holder has a concave one (Figure 1-2). As a result, there are two issues. Each of the stakeholders will have different requirements (cash flow rights) and would make different decisions about the management of the firm (control rights11).

FIGURE 1-2

Debt and Equity Payoffs

Figure 1-2 depicts the payoffs to the debt holder and the equity holder as a function of the value of the firm V at the debt maturity. D is the principal of debt. The payoff to the debt holder is bounded by the repayment of the principal D. If the value of the firm is below the principal  , then debt holders have priority over equity holders and seize the entire value of the firm V. Therefore equity holders have a zero payoff. However, if the value of the firm is more than sufficient to repay the debt

, then debt holders have priority over equity holders and seize the entire value of the firm V. Therefore equity holders have a zero payoff. However, if the value of the firm is more than sufficient to repay the debt  , the excess value

, the excess value  falls into the hands of equity holders. Clearly, the debt holder is not interested in the firm reaching very high levels

falls into the hands of equity holders. Clearly, the debt holder is not interested in the firm reaching very high levels  as its payoff is unchanged compared with the situation in which

as its payoff is unchanged compared with the situation in which  . On the contrary, the higher the value of the firm, the better for the equity holder.

. On the contrary, the higher the value of the firm, the better for the equity holder.

Equity holders run the firm and make investment and production decisions. The convexity of their payoff with respect to the value of the firm induces them to take on more risk in order to try and reach very high levels of V. If the project fails, they are protected by limited liability and end up with nothing. If the project succeeds, they extract most of the upside, net of the repayment of the debt.

Financial theory shows that optimal allocation of control rights between debt holders and shareholders enables in some cases the maximization of the value of the firm in a comparable way to the entrepreneur who funds capital expenditures from his or her own resources. This second-order optimum requires a fine tuning between equity and debt in order to minimize the following two sources of inefficiency:

The asymmetry of roles between the uninformed lender and the well-informed entrepreneur

The asymmetry of roles between the uninformed lender and the well-informed entrepreneur

Market inefficiencies—the incompleteness of contracts, leading both parties to be unable to devise a contract that would express the adequate selection rule as well as the rule for optimized management of the project12

Market inefficiencies—the incompleteness of contracts, leading both parties to be unable to devise a contract that would express the adequate selection rule as well as the rule for optimized management of the project12

We now turn to these inefficiencies in more detail, focusing first on the impact of the asymmetric relationship between entrepreneurs and investors vis-à-vis the value of the firm. We then review the instrumental understanding of the capital structure of the firm, given incomplete contracts.

An asymmetric relationship exists between the investor providing funding and the entrepreneur seeking it: asymmetry in initial wealth, asymmetry regarding the management of the funded project, and, of course, asymmetric information. The entrepreneur has privileged private knowledge about the value of the project and how it is managed.

There are two major types of asymmetric information biases in microeconomic theory:

Adverse selection. Because of a lack of information, investors prove unable to select the best projects.13 They will demand the same interest rate for all projects. This will, in turn, discourage holders of good projects, and investors will be left with the bad ones.

Adverse selection. Because of a lack of information, investors prove unable to select the best projects.13 They will demand the same interest rate for all projects. This will, in turn, discourage holders of good projects, and investors will be left with the bad ones.

Moral hazard. If an investor cannot monitor the efforts of an entrepreneur, the latter can be tempted to manage the project suboptimally in terms of the value of the firm. This lack of positive incentive is called “moral hazard.”

Moral hazard. If an investor cannot monitor the efforts of an entrepreneur, the latter can be tempted to manage the project suboptimally in terms of the value of the firm. This lack of positive incentive is called “moral hazard.”

Adverse selection refers to the intrinsic quality of a project, whereas moral hazard relates to how the entrepreneur behaves (whatever the actual intrinsic quality of the project). In addition, adverse selection will occur before a contractual relationship is entered, whereas moral hazard will develop during the relationship.

Here we highlight some aspects of the complex impact of adverse selection on good firms and good projects. We mainly consider investors and firms. We show how difficult the selection of companies is for investors. In particular, debt allocation (in essence bank intermediation) is important to support projects and provide a signal to investors.

The Capital Structure of the Firm Can Be Seen as a Signal to Investors, and Surprisingly Not Exactly the Way Common Sense Would Suggest When there is adverse selection, the financial structure of the firm can be seen as a signal to investors. The two approaches below are about costs of signaling. In Ross (1977), costly bankruptcy is considered. In Leland and Pyle (1977), the focus is on managerial risk aversion, with managers who signal good projects by retaining risky equity.

A reasonably large level of debt could be seen as evidence of the good quality of the firm. Ross (1977) expresses this idea in a particular case, i.e., on the basis of two strong assumptions:

The entrepreneur is a shareholder and therefore will benefit from debt leverage since it increases the value of the firm.

The entrepreneur is a shareholder and therefore will benefit from debt leverage since it increases the value of the firm.

The entrepreneur will receive a specific penalty if the firm goes bankrupt.14

The entrepreneur will receive a specific penalty if the firm goes bankrupt.14

Under such assumptions, only good firms would use debt, because for bad companies, recourse to debt would not maximize the utility function of the entrepreneur, given the increased bankruptcy risk. In this context, debt would operate as a way to segregate good companies from bad ones.

Other models15 follow the same path, assuming that up to a certain level, debt and leverage can be seen as an expression of robustness of firms, providing a positive signal. Leland and Pyle (1977) come to the same result, but without assigning penalties to the entrepreneur under bankruptcy. The idea behind such models is that if the entrepreneur knows that a given project within the firm is good, he will tend to increase his participation in the company. But because he needs cash to finance the project, he will have to use debt. In the end, increased leverage goes along with increased participation of the entrepreneur as a shareholder, thus providing a good signal.

To Some Extent, the Definition of a Pecking Order of Financial Instruments Can Compensate for Adverse Selection, When a Signal Can Be Sent to Investors Another element tends to restrain the selection of good projects: the underestimation of the value of the equity by investors due to their limited access to company and project information. If the value of the shares of a firm is significantly undervalued, good new projects that would be suitable for investment16 may be rejected because of lack of funding. Existing shareholders will not be willing to supply new funding given the low valuation of the firm. They will also refuse to allow new shareholders in since newcomers not only would benefit from the cash flows of the new projects but also would benefit from all existing projects of the firm (dilution effect). This situation of lack of equity funding is clearly suboptimal for the economy. It can be compensated by seeking internal funding based on cash flows. If this option proves impossible, then the company will try to avoid the effect of adverse selection through the use of external debt and in particular of fairly valued low-risk securities with strong collateral (e.g., asset-backed securities on receivables, etc.).

Under strong adverse selection, all companies will be evaluated by investors at a single price, based on average expected return. The average price will play against good companies. In the end, good firms will curtail their investment plans, whereas bad ones will keep on investing by tapping the equity markets. In reality, ways exist to compensate for adverse selection through recourse to funding based on a pecking order.17 The firm will try to limit its cost of financial funding by choosing instruments based on a ranking: Cash flow comes first, then risk-free debt, then well-secured less risky debt, then unsecured debt, and ultimately equity.

Recent crises like Enron in the United States or Vivendi Universal in Europe, where the management of the company has shifted from the initial core business without the clear consent of all stakeholders, stand as a good example of moral hazard. Enron indeed moved from a gas pipeline business to an energy trading activity, while Vivendi Universal evolved from a water and waste management utility to a media and telecom company. Both companies engineered a buoyant communication policy vis-à-vis the stakeholders that was largely focused on the personality of the top management. This behavior ultimately led to some accounting opacity concealed to some extent by the communication policy.

The investor-entrepreneur relationship can be illustrated using principal-agent theory.18 Moral hazard supposes that decisions made by the agent that affect the utility function of both the agent and the principal cannot be fully observed by the principal.

In what follows, we first describe the moral hazard problems and then show how banks bring value in solving parts of these issues.

Conflict of Interest between Entrepreneurs and Investors According to Jensen and Meckling (1976), moral hazard between an entrepreneur and an investor arises from competing interests. The entrepreneur tries to benefit from any new project and to extract value for herself. She does so, for instance, by recourse to additional spending paid by the firm, hence reducing the shareholders’ value.

The main types of entrepreneurs’ misbehaviors are:

Actions driven by private benefits

Actions driven by private benefits

The use of firm resources for private purposes

The use of firm resources for private purposes

Limited effort

Limited effort

Blackmail on early departure from the company

Blackmail on early departure from the company

Overinvestment to maximize the entrepreneur’s utility19

Overinvestment to maximize the entrepreneur’s utility19

Disagreement on the decision to terminate the business though it is the optimal decision

Disagreement on the decision to terminate the business though it is the optimal decision

Given all these negative incentives, it seems desirable to have entrepreneurs who are also shareholders. However, as entrepreneurs are typically short of cash, a high level of leverage is often required to finance the expansion of the firm, leading the entrepreneurs to resort to large debt. This often results in a new form of moral hazard between shareholders and debt holders. Shareholders indeed benefit from limited liability and have an incentive to maximize leverage and favor riskier projects, while debt holders seek to minimize risk in order to avoid the large downside corresponding to bankruptcy. In other words, shareholders tend to seize parts of the benefits that should accrue to debt holders. As debt holders expect such behavior, they ask for an additional risk premium on issued debt. The value of the firm is thus lessened by agency costs on debt issuance.

Jensen and Meckling (1976) conclude that the balance between debt and equity can be analyzed on a cost-benefit basis. The benefit is linked with the convergence of the utility of the entrepreneur and that of the shareholder (reducing moral hazard between the two). Cost is expressed as agency cost generated by the risk-averse debt holder.

The Debt Contract: The Way to Reduce Such Inefficiencies Carefully specifying covenants in debt contracts can provide a remedy for many inefficiencies. In the situation described above, analyzed by Harris and Raviv (1991), the control of the firm or of its assets will typically be transferred to creditors in case of distress or default.

Several studies have come to the conclusion that a standard debt contract20 is optimal in a context of asymmetric information. Indeed, revealing the true return of the project to the investor becomes the best choice of the entrepreneur. The standard debt contract can always be improved in order to deal with the problem of limited involvement of the entrepreneur. The best way to do so is to award a bonus21 that is calibrated on an observable criterion expressing the effort of the manager. This can also be complemented by ongoing surveillance of the entrepreneur through some monitoring of the project’s performance.

These developments on optimal contracts do not, however, provide insights regarding the rationale for equity origination. One of the main weaknesses of the previous analysis is that it is static.22 Diamond (1989) considers a dynamic approach with repeated games and reputational effects. He shows that in a Jensen and Meckling (1976) setup, shareholders and debt holders will pilot the level of risk together in order to establish the reputation of the company and reduce agency costs in the long run, i.e., credit spreads. This analysis is particularly insightful with respect to the debt policy of large companies.

In reality the relationship between creditors and debtors can be more complex. It cannot always be ruled by a customized written contract. As a result, the conceptual framework most frequently used to deal with moral hazard corresponds to the analysis of dynamic interactions between agents in a situation of incomplete contracts.

Moral hazard between the debtor and the creditor is a significant issue. They stand in a conflicting position, challenging each other on the control of the firm in a situation where asymmetric information prevails. Finding a conceptual way to resolve this issue is possible by considering incomplete contracts.

Allocation of Control Rights The starting point with this approach is to assume that no contract can fully solve the latent conflict of interest between creditors and debtors. In order to obtain a performance as close as possible to the optimum, the best solution is to allocate control to the agent23 who will follow the most profitable strategy for the firm. Simply put, the efficiency of the performance of the firm will then depend on the optimal allocation of control rights. This allocation process is dynamic and, of course, fully contingent on the current performance of the firm.24

The above corresponds to an instrumental view on contracts. This means that such contracts are used in order to distribute control rights appropriately among the entrepreneur, shareholders, and creditors.

The Two Main Types of Contracts The management policies resulting from debt and equity contracts will be dissimilar:

Debt contracts typically lead to higher risk aversion, strong governance, and strict control of the entrepreneur.

Debt contracts typically lead to higher risk aversion, strong governance, and strict control of the entrepreneur.

Equity contracts, on the other hand, imply lower risk aversion, more flexibility, and freedom for the top management of the firm.

Equity contracts, on the other hand, imply lower risk aversion, more flexibility, and freedom for the top management of the firm.

Let us examine a simplified two-period case. Under incomplete contracts, we assume that the initial financial structure of the firm is defined and is reflected in financial contracts with lenders and shareholders. At the end of the first period, the agents (debt holders, shareholders) observe the level of return as well as the involvement and performance of the entrepreneur. Usually, debt contracts will enable the redistribution of control rights. For example, in the case of default or distress, a new negotiation between stakeholders will occur, giving power to creditors. Creditors can decide to liquidate or to reorganize the firm. As a result, the control of creditors will be much tighter.25

The model by Dewatripont and Tirole (1994) shows how the capital structure can lead to optimal dynamic management. For instance, the authors explain that a sharp increase in short-term debt will lead to a real risk of default as well as to a potential change of control in favor of creditors. Because of this threat, entrepreneurs have strong incentive to manage the company appropriately, i.e., taking into account creditors’ interests. Since debt is considered a risk for managers, it leads them to conduct business prudently. In addition, problems linked with existing asymmetric information and conflicts of interest among stakeholders are lessened by the necessity to sustain a firm’s reputation as a debtor. Large corporate firms reflect this situation well, being continually reviewed by rating agencies that assess their reputation.

We have seen that all stakeholders involved in a firm have different objectives and risk profiles. We have tried to explain where these differences are coming from, using both payoff analysis and concepts extracted from microeconomic theory (adverse selection and moral hazard). We have also discussed the ability of financial contracts related to the capital structure of the firm to allocate control rights in the most efficient way in order to achieve optimal risk-return performance. Based on this investigation, formulating customized contracts and engaging in active monitoring can prove an interesting solution. It all relates to the role of banks, the subject of the following sections.

Why use banks? This question can be formulated from the point of view of a firm seeking financing: Why choose a bank rather than tap the market in order to raise finance? It can also be considered from the point of view of investors: Why deposit money in a bank account instead of buying a bond directly?

Banking theory is based on intermediation: The institution receives deposits, mainly short-term ones, and lends money for typically fixed long-term maturities (illiquid loans). This maturity transformation activity is a necessary function for the achievement of global economic optimum. Banks act as an intermediary and reduce the deficiencies of markets in three areas: liquidity, risk, and information.

In the next paragraphs we address these various types of intermediation. We particularly focus on the reason why banking intermediation is Pareto optimal, compared with disintermediated markets. The core advantages of banks in this activity are explicitly defined.

The banking activity reconciles the objectives of two major conflicting agents in the economy:

Consumers. These agents maximize their consumption utility function at a given time horizon (short term). Their needs are subject to random variations. Consumers are averse to volatility and prefer smooth consumption patterns through time. Shocks in purchasing power (due to temporary unemployment or an unexpected expense, for example) could generate reduced utility if the agents were forced to cut their spending. The best way for them to minimize this risk and maintain optimal behavior is to keep a sufficient deposit cushion that absorbs shocks. Bank deposits are similar to liquidity insurance. The insurance premium is reflected in the low interest rate paid on such deposits.

Consumers. These agents maximize their consumption utility function at a given time horizon (short term). Their needs are subject to random variations. Consumers are averse to volatility and prefer smooth consumption patterns through time. Shocks in purchasing power (due to temporary unemployment or an unexpected expense, for example) could generate reduced utility if the agents were forced to cut their spending. The best way for them to minimize this risk and maintain optimal behavior is to keep a sufficient deposit cushion that absorbs shocks. Bank deposits are similar to liquidity insurance. The insurance premium is reflected in the low interest rate paid on such deposits.

Investors. The bank makes profits in leveraging consumers’ deposits and financing long-term illiquid investments. The two core requirements to succeed in such operations are diversification and liquidity stability based on “mutualization.” Diversification means that the bank is able to repay deposits because it works on a diversified portfolio of loans (diversified in terms of maturities and credit risk). Liquidity stability suggests that the amount of deposits it holds is fairly stable over time because all depositors will not require cash at the same time.

Investors. The bank makes profits in leveraging consumers’ deposits and financing long-term illiquid investments. The two core requirements to succeed in such operations are diversification and liquidity stability based on “mutualization.” Diversification means that the bank is able to repay deposits because it works on a diversified portfolio of loans (diversified in terms of maturities and credit risk). Liquidity stability suggests that the amount of deposits it holds is fairly stable over time because all depositors will not require cash at the same time.

One of the first models portraying banking intermediation is that of Diamond and Dybvig (1983). The authors show that banking intermediation is Pareto optimal in an economy with two divergent time horizons: the long term of entrepreneurs and the short term of consumers.

Diamond and Dybvig clearly put emphasis on deposits rather than on lending policy.26 Their bank could have invested in bonds (rather than lend to entrepreneurs) and obtained a sufficient diversification effect. In their very theoretical economy, if consumers directly owned long-term bonds, these instruments would tend to be underpriced. This price gap would correspond to a liquidity option required by these agents in order to cover any sudden liquidity need.

When an entrepreneur develops a new project, she knows that she may have to face unexpected financial needs to sustain random shocks on income or expenses. As long as these new financial requirements imply value creation for the firm,27 there will probably exist an investor to bring additional cash. But the new money needed may not be linked with the value of the firm or the value of the project. It can be a mere cost.28

The company has to anticipate such a liquidity risk. Two main options are available:

Hold money in reserve, for example through liquid risk-free bonds (government bonds), that can be used for unexpected difficulties.

Hold money in reserve, for example through liquid risk-free bonds (government bonds), that can be used for unexpected difficulties.

Hold no initial reserve and rely on an overdraft facility obtained from a bank.

Hold no initial reserve and rely on an overdraft facility obtained from a bank.

Diamond (1997) and Holmström and Tirole (1998) offer interesting insights regarding the second option. When the liquidity risks of different companies are independent, then bank overdrafts become Pareto optimal and supersede the use of liquid bonds. The proof is again based on mutualization: If nothing happens to the project or to the company, then the bonds are unnecessarily held while the money could be invested in the firm. It artificially increases the value of these bonds on financial markets and is costly to the company itself (in terms of yield differential between the riskless investment and an investment in other projects). In contrast, any new customer increases the mutualization and diversification of the bank, thereby improving overdraft lending conditions.

Banks fulfill another very important economic function: bearing, transforming, or redistributing financial risks. For example, the progress achieved in interest rate risk management in the eighties has been accompanied by the boom in derivative markets. Banks have become experts in terms of financial risk management and have begun to sell this expertise to corporate firms. This activity has been predominantly driven by investment banks.

The objective of this section is not to discuss asset and liability management specifically, nor to explain how credit derivatives can be used to manage risks.29 It is rather to focus on the changing relationship between commercial banks and firms in the context of financial market expansions and credit disintermediation.

Looking at risk management principles from the bank’s point of view, and in particular at credit risk, we shed some light on the criteria for decision making: Should a bank hold and manage such risks or sell them?

In developed economies, credit products are increasingly available in financial markets. In particular, securitization has expanded significantly since the eighties. It has given birth to an enormous market of traded structured bonds (collateralized debt obligations, asset-backed securities, etc.) in the United States and subsequently in Europe. Credit derivatives have enabled synthetic risk coverage, without physical exchange of property rights and without initial money transfer. This trend illustrates a major shift in the role of commercial banks in financial markets. Allen and Santomero (1999) show how important securitization has been in the United States (see Figure 1-3).

FIGURE 1-3

The Growing Importance of Securitization

As Figure 1-3 shows, credit risk is increasingly brought back to the market by commercial banks. The next step is then to rationalize the decision process within the bank, based on an adequate definition of the risk-aversion profile of the bank. In a similar way as for interest rate risk, the choice will lie somewhere between two extreme options: Either become a broker through complete hedging in financial markets, or become an asset transformer who holds and actively manages risk through diversification and ongoing monitoring of counterparties.30

A credit decision involves three components: financial, managerial, and strategic. Risk management consists primarily of reducing earnings volatility and avoiding large losses. For a bank, mastering the stability of its profits is a critical credibility issue, because if the current capital structure of a banking firm is not strong enough, some additional external funding will be required. Such funding can prove costly and dangerous because of agency costs driven by asymmetric information or potential conflicts of interest between managers and investors. As a result, the bank should definitely think about and define its own risk aversion in order to target earnings stability and the robustness of its capital structure.31 This part of a bank’s mission is often understated although it is critical in terms of competitive positioning among peers.

In addition, risk management allows banks to have less costly capital sitting on their balance sheet, while satisfying minimum capital requirements.

From a management point of view, both brokerage (reselling risk) and asset transformation (keeping risk) are possible as long as the underlying assets display sufficient liquidity.32

In the case of brokerage, the bank’s profit is based on marketing and distribution skills.

In the case of brokerage, the bank’s profit is based on marketing and distribution skills.

In the case of asset transformation, a gross profit from risk holding is generated. This profit has to be netted with holding costs, such as monitoring costs and costs associated with concentration of the portfolio in a specific sector or region.

In the case of asset transformation, a gross profit from risk holding is generated. This profit has to be netted with holding costs, such as monitoring costs and costs associated with concentration of the portfolio in a specific sector or region.

Considering these two options, the bank has to draw comparisons and to set limits, based on a return-risk performance indicator. When holding risk is preferred to pure brokerage, the ability to measure appropriately the level of economic capital “consumed” by a specific loan becomes critical, as it is the most important risk component in the evaluation of the performance indicator. This stresses the crucial priority of understanding dependence-correlation patterns in a dynamic way, as diversification is one of the most significant ways to gain economic capital relief (see Chapters 5 and 6).

From a strategic perspective, the main question is to understand whether a bank holds a competitive advantage in the lending business compared with markets. Leland and Pyle (1977) were the first to identify that banks have an advantage over investors, based on the privileged information they collect on loans and borrowers. Diamond (1984) and a stream of other articles have established that debtor surveillance and delegated monitoring by banks corresponded to an optimal behavior. It is now clear that the right perimeter for the lending business by banks is that in which the bank retains an informational advantage in terms of credit risk management.

Investment financing takes place in a context where asymmetric information is frequent and significant. The entrepreneur seeking financing obviously knows more about his project than potential investors or their representatives.

Two perverse effects result from asymmetric information as recalled above: adverse selection and moral hazard.

The entrepreneur could try to benefit from asymmetric information and to extract undue value from his project. As mentioned previously, the nature of the lending contract can minimize this risk and provide incentive for the entrepreneur to behave optimally. However, direct surveillance of the manager by the lender can prove very valuable to deter the entrepreneur from concealing information. Diamond (1984) has introduced the concept of monitoring. If the bank (the monitor) observes the evolution of the value of the project carefully and frequently, it can dissuade the entrepreneur from defaulting on his debt by introducing the threat of a liquidation. Most of the time the threat will be sufficient, and the bank can deter the entrepreneur without having to take action. This active monitoring obviously has a cost, but Diamond estimates that it is lower than the expected cost of going into liquidation.

Let us now focus on the reason why banks are best placed to perform monitoring. When the number of projects (n) and the number of lenders (m) get large, the number of required surveillance actions becomes very quickly intractable. There is a strong incentive to delegate monitoring to a bank that will supervise all projects on behalf of investors. The bank faces a single cost of K per project; i.e., the corresponding cost for each lender becomes K/m. This is in fact not exactly true, as lenders must deal with an additional moral hazard problem: how to make sure that the bank is acting appropriately. In order not to have to monitor the bank itself, investors seek insurance to protect their deposits. Diamond shows that the monitoring costs for the bank correspond to nK, plus the cost associated with deposits contract c(n). This global cost is inferior, for a large m, to direct monitoring costs nmK by investors.

On the basis of all the approaches generated by Diamond’s (1984) seminal article, we will identify where the advantage of the banks resides in terms of monitoring.

Theoretical Advantages for Banks Diamond’s presentation has been criticized, modified, and broadened. The optimality of standard debt contracts has been tested in various cases,33 for different types of loans,34 and for various agents.35 Other models have been introduced where moral hazard impacts on the level of effort provided by the entrepreneur.

Most of the articles tend not to focus on adverse selection. Gale (1993), however, has mixed delegated monitoring with appropriate screening of entrepreneurs. This type of screening selection requires an additional cost equivalent to a pure monitoring cost. In Gale’s model, a too large demand for loans tends to saturate the banking system and to generate credit rationing.36 In the end Gale suggests adding additional selection criteria, such as asking for an ex ante fee to work on any loan requirement. This reduces the demand for loans and the risk of credit rationing.

Bank Lending Efficiency A bank lends money to a company, having spent time and money on monitoring. To some extent, through this initial investment, the bank has significantly reduced competition. At the same time, it takes a long time for the customer to obtain the positive reputation of “a good debtor” when the maturity of the loan is long enough. In the meantime the bank will be in a position to have the customer overpay on any new loans until his reputation as a reliable borrower is clearly established. Through this mechanism, the bank can generate a secure surplus.37 This could lead to a too high cost of capital in the economy and to suboptimal investment.

Optimal Split between Banks and Financial Markets It is clear that when there is transparency and when information about companies is widely diffused, the competitive advantage of banks over financial markets tends to decrease.38 For large firms, monitoring can be performed outside the bank, for example by rating agencies.39

For well-rated large companies with good profit prospects, financial markets can fully solve moral hazard issues without recourse to monitoring. The main incentive for such a company is to sustain its good reputation. A rating migration, an increase in the firm’s spread level or a period of financial distress can tarnish the firm’s reputation, damage investors’ confidence, and increase substantially its funding costs. The reputation effect becomes a very strong incentive, capable of restraining debtors.40 In such a situation financial markets benefit from a strong advantage, as marked-to-market prices tend to reflect all available information and affect all stakeholders. This informational advantage can be seen as a strong positive element in the economy.

Private companies, e.g., smaller or younger companies or companies without any rating or with a low (non-investment-grade) rating, tend to ask for bank loans and ongoing monitoring in order to strengthen their reputation before tapping the bond markets. For such debtors asymmetric information becomes the major issue. We have seen above that banks are most efficient in dealing with this type of problem.

On the particular topic of financing very innovative projects, some studies have shown, however, that market intermediaries such as private equity or leveraged finance specialists are better able to perform selection of entrepreneurs and projects, based on customized contracts.41

The first conclusion we would like to draw is that although disintermediation is a real phenomenon, the future of banks is not at stake. Their scope of activity has evolved given the increased weight of financial markets, but their activity more than ever is central to the efficiency of the economy.

In addition we have seen that a bank is properly defined by three major intermediation activities: liquidity, risk, and information intermediation. When dealing with credit risk management, it is essential not to forget some very important concepts such as liquidity management and information management. In the recent past it has been increasingly recognized that credit risk management cannot be separated from global risk management. The message we would like to convey here is that global risk management cannot be isolated from liquidity and information management.

Credit rationing is a well-established concept. Jaffee and Modigliani (1969) had already mentioned that in the case of interest rate rigidity, banks would opt for credit rationing. This concept has, for example, been used in macroeconomics to evaluate the impact of a monetary policy on the real economy when investment demand appears to be partially disconnected from interest rates (Bernanke, 1983, 1988).

The seminal article in credit rationing is Stiglitz and Weiss (1981). The authors study the credit market under incomplete information. They show how asymmetric information leads to credit rationing, i.e., a situation where the demand for loans is in excess of offer.

The relation between a bank’s expected profit and the offered interest rates is abnormal, being altered by adverse selection and lack of incentive. In such a situation the bank cannot distinguish among various debtors who have private information on the true level of risk of their projects. When banks’ competition is limited (the banks are “price makers”), a bank can choose to increase interest rates in order to select the best-performing projects. But contraintuitively such a policy will penalize the best projects first, leading banks to pick worse ones.

An analysis of the behavior of the debtor and the creditor will explain this result. We consider two projects with equal expected returns but different risk levels.

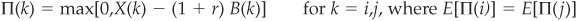

For each project (i), the project return is X(i), the debt level is B(i), and the interest rate is r. From the company standpoint, the manager can expect to make a profit once she has repaid the debt:

This corresponds to writing a call option. But for a call, we know that vega =  , which implies that the riskier the project, the more rewarding it is in terms of call value. For a given expected return, the debtor will prefer the riskier project. This corresponds to moral hazard.

, which implies that the riskier the project, the more rewarding it is in terms of call value. For a given expected return, the debtor will prefer the riskier project. This corresponds to moral hazard.

The manager of a risky project will therefore agree to pay a higher interest rate than the manager of a safe project, given the higher level of the upside. Limited liability ensures that the downside is bounded. This mechanism, whereby a bank has incentive to select bad risks (“lemons” as Akerlof, 1970, puts it) and to reject good ones, is called adverse selection. This phenomenon tends to reduce the bank’s expected profit. The function that maps interest rates to expected profit has a bell shape. Its maximum is obtained for a level of interest rates where adverse selection reduces the bank’s profits enough to offset the increase due to interest rates. This value may not correspond to the full adjustment between the offer of and demand for loans: Credit rationing appears with suboptimality.

The model by Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) is one of the most important reference points in banking theory. It has clarified the effect of asymmetric information in banking. However, the lender has a simplistic behavior, because the lender can only act through the interest rate on loans.

Several articles have tried to illustrate constraints on a “price-taker” bank and the consequences in terms of credit rationing.

In a competitive environment a bank is not able to adjust its interest rates. The adjusted price is based on market equilibrium. Before accepting any project, the bank has to check the following three criteria:

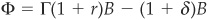

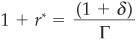

1. On each project the interest rate has to incorporate the default risk on the global portfolio of the bank (Jaffee and Russell, 1976). In the following equation, Φ is the expected profit of the bank, δ the refinancing cost of the bank,  the average recovery rate on the bank loan portfolio, B is the loan exposure of the bank, and r the interest rate on loans. The bank maximizes

the average recovery rate on the bank loan portfolio, B is the loan exposure of the bank, and r the interest rate on loans. The bank maximizes

With a minimal equilibrium for  (competition drags expected profits to 0), we have

(competition drags expected profits to 0), we have

The inability to identify the credit quality of its individual clients implies that the bank has to charge an average interest rate based on the average recovery rate: “Good” borrowers will pay for “bad” ones. There is a mutualization effect. Such a behavior will penalize good borrowers who will have to pay a risk premium independent from the risk of their project. By acting this way, a bank could avoid financing good projects for which market pricing is considered as being incompatible with the bank’s internal hurdle rate.

2. On each project there is an adjustment between market interest rate pricing and an optimal interest rate required by the bank:

If the interest rate is lower than the optimum defined by the bank, then the project may not be retained.

If the interest rate is lower than the optimum defined by the bank, then the project may not be retained.

If the interest rate is higher than this optimum, then increasing default risk will reduce expected return. Indeed the bank’s expected return follows a concave function of the interest rate (bell curve). The bank can discover the optimal point and understand that too-high interest rates weaken projects and make them riskier in terms of probability of default.

If the interest rate is higher than this optimum, then increasing default risk will reduce expected return. Indeed the bank’s expected return follows a concave function of the interest rate (bell curve). The bank can discover the optimal point and understand that too-high interest rates weaken projects and make them riskier in terms of probability of default.

When market equilibrium interest rates are too far from the optimal rate defined by the bank, then the project is rejected within the bank, i.e., there is credit rationing.

3. On each project the impact of the size of a loan needs to be taken into account. Say the profit of the firm is X. It is supposed to be bounded, with  . The loan is B, and r is the interest rate. One of these three results would be obtained:

. The loan is B, and r is the interest rate. One of these three results would be obtained:

For small-size loans

For small-size loans  , the loan service is inferior to the minimum profit of the firm. The bank can lend just over refinancing cost.

, the loan service is inferior to the minimum profit of the firm. The bank can lend just over refinancing cost.

If the size of B increases, the probability of default increases equally, but a higher interest rate r is sufficient to compensate for accrual risk.

If the size of B increases, the probability of default increases equally, but a higher interest rate r is sufficient to compensate for accrual risk.

Over a certain B*, it would be wise to increase interest rates and reduce the size of the loan.

Over a certain B*, it would be wise to increase interest rates and reduce the size of the loan.

When the bank is price taker, it has to reject some projects because of return requirements. This can lead to credit rationing. These requirements depend on the average default rate in the bank portfolio, the size of the exposure on each project, and the market interest rate compared with the expected return of the bank.