| 10 | Rate of profit and crisis in the US economy |

| A class perspective | |

| Simon Mohun |

In Understanding Capital (Foley, 1986), Duncan Foley proposed a way of thinking about Marx’s categories that developed the approach of his earlier article (Foley, 1982; see also Duménil, 1983; Mohun, 1994). Marx had built his analysis in Capital Volume 1 on the basis of the labour theory of value, which postulated that the price of each commodity pi was its labour value λi divided by the value of the money commodity λmc. For (the typical) commodity i at unit level,

|

(1) |

His subsequent Volume 3 analysis showed that such value-price relations could not in general hold because of the different compositions of capital (ratios of labour to non-labour input) involved in the production of commodities. Competition tendentially equalized the rate of profit, and entailed price-value deviations for individual commodities. Notwithstanding individual price-value deviations, Marx tried to show that the labour theory of value continued to hold at an aggregate level. Subsequent commentary on and evaluation of Marx’s demonstration has become known as “the transformation problem”, and a huge literature has established positions along a spectrum varying from praise of Marx’s complete success to condemnation of his complete failure.

Foley’s approach sidestepped this debate, by proposing that Marx be interpreted as saying that, in the aggregate, hours of productive labour (Hp) and money value added (Y) are essentially the same thing; the one is always equal to the other, with the value of money λm relating the different dimensions.1 That is, whatever the individual price-value deviations,

|

(2) |

Money is no longer a commodity such as gold, but is a composite whose value is defined by equation (2). Further, while labour-power is commodified under capitalist relations of production, it is not a produced commodity. With neither composition of capital nor profit to consider, the tendential equalization of profit rates through competition has no relevance, so that at this level of abstraction, the relation between the value of labour-power and its price is unaffected by price-value deviations. Therefore equation (1) applies and the price of labour-power per hour of productive labour hired (the hourly wage rate wp) is simply its value per hour of labour hired (λz) divided by the value of money, or

|

(3) |

Equations (2) and (3) obviously hold in a world in which equation (1) holds for all commodities. But Foley’s proposal that equations (2) and (3) also hold in a world of unequal or non-equivalent exchange (in which equation (1) does not generally hold) provided a powerful way of using the labour theory of value empirically. For, since total value added in hours (Hp), is the sum of variable capital (V) and surplus value (S), and since total money value added is the sum of total wages (Wp) and surplus value in money terms (MSV), then it is easy to show that

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

and

|

(6) |

In particular, surplus-value in money terms remains proportional to surplus-value in (socially necessary) labour hours, and therefore unequal exchange makes no difference to the fundamentals of the analysis of exploitation and profit. In the course of his argument, Foley made reference to the applicability of the categories to the US economy, using real (rounded) numbers (Foley, 1986, pp. 14–15, 46, 122–124). While his purpose was to illustrate the theoretical concepts and provide plausible orders of magnitude, his approach raised the possibility of a more sustained empirical analysis on this value-theoretic basis.

This chapter investigates data for the US economy within this framework. It begins by relating the 1982 Foley approach to the forces and relations of production in order to develop a focus on capital productivity (the ratio of money value added to the fixed capital stock) as encapsulating the forces of production, and the money surplus value share as encapsulating the relations of production. Combining the two generates the overall rate of profit for the economy as a whole, whose long run development is then explored.

There are a number of substantial and influential analyses which have proposed a long run Marxist analysis of the US economy. Representative analyses include Brenner (1998, 2002), Duménil and Lévy (1993, 2004, 2011), Gillman (1957), Moseley (1991), Shaikh (1999, 2010), Shaikh and Tonak (1994) and Weisskopf (1979). This chapter proposes that the profit share and consequently the rate of profit have not been sufficiently well-specified in the Marxist literature. Profits are by definition the residual from money value added once wages have been paid. But little attention has been given to how to measure wages.2 Generally wages are taken to be employee compensation (possibly together with some estimate of the wage component of self-employed income). But in class terms this includes both working-class labour income and non-working-class labour income. Conventionally defined wages and profits are not class categories, and if class is to be the primary category of analysis, this makes a substantial difference to how the data have to be constructed. This recognition problematizes the conventionally defined rate of profit as the key indicator of the development of capitalism. Constructing a “class rate of profit” requires that the labour income accruing to those who are not members of the working class be explicitly considered, and this in turn requires both a specification of how the non-working-class might be empirically identified, and a specification of how to measure their labour income.3

In short, class matters. This chapter therefore focuses particularly on the relations of production. Using annual data beginning in 1909, it finds that a class-defined rate of profit (with a numerator comprising profits plus the labour income that does not accrue to the working class) is generally rising through time; that is, there is a marked long run tendency of this class rate of profit to rise. That rise is punctuated by short run stagnation of profitability that precedes serious crises in 1913, 1929, 1979 and 2007–8. Resolutions of the crises which these short run downturns precede more than overcome the preceding stagnation. But processes of crisis resolution require régime change.4 In 1913, that change was relatively minor (the formation of a national banking system, whose roots lay in response to the crisis of October 1907). In the second two cases, the changes were major (to a weak form of social democracy after 1929, and to neoliberal finance after 1979). As of 2012, resolution of the crisis of 2007–8 is uncertain and continuing.

The forces of production are “material productive forces” (Marx, 1987 [1859], p. 263) and concern the appropriation of the natural world to human ends. They describe the knowledge of science and technology, and how this is put to practical effect in the organization of production. For most of human history, such knowledge has increased only slowly, but after about 1500 this began to change. In the modern era (from about 1770 onwards) the forces of production have evolved rapidly, posing potentialities of great change.

The relations of production are concerned with how the surplus product is produced by the immediate producers, and how it is then appropriated. These issues are generally determined by ownership of and control over the means of production, that is, by property relations. They therefore depend upon both the physical force and the ideologies that maintain those property relations. Following the development of settled agriculture, and the possibilitiesof storage of a surplus and consequent acquisition of wealth, these relations revolved around the ownership and control over land and the means to cultivate it. More recently, they have been concerned with how surplus labour is extracted in industrial production processes and realized in trade, surplus product appearing as profit.

Considering both forces and relations of production together, in Marx’s phrase, the relations of production are “appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production” (ibid). So the forces of production determine what relations of production are possible at any time. At the same time, the forces of production are only applied under particular relations of production, so that the relations of production determine how the forces of production are developed. In contrast to the dynamism of the forces of production, changes in property relations are severely constrained by the prevailing pattern of asset ownership and the material interests to which that pattern gives rise. Prevailing relations of production can thereby limit potentialities, to such an extent that

the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production, or — this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms — with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution.

Marx, 1987 [1859], p. 263

But as well as determining transformations of one mode of production into another, this opposition between forces and relationsofproduction also determines transformations within modes of production. A number of possible political, legal and ideological forms are compatible with a given pattern of property relations, andaslong asthat basic patternis maintained, varieties of regime change involving significant institutional and political change within modes of production are possible.

In capitalism, the forces of production are developed through innovation in products and processes, with the motor force being competition between competing capitals. An innovating capitalist can undercut rivals, taking market share and extra profit. Rivals must copy and similarly innovate, or ultimately they will fail.

Innovation enables a reduction in unit costs via productivity increases. This is typically achieved by adding to the non-labour inputs (means of production) with which labour works. Such investment depends upon the relation between the cost of the extra means of production per worker-hour and the benefit of the productivity increase to which it leads. The use-value equivalent of this value criterion concerns the question of how much productivity increase a given increase in capital intensity yields. Define the constant price productive fixed capital stock (kp) as the nominal fixed capital stock worked by productive labour (Kp) deflated by the net value added deflator (pY),

|

(7) |

and similarly define constant price money value added y as

|

(8) |

Then labour productivity is y/Hp and capital intensity is kp/Hp. The development of the forces of production might mean that the rate of growth of labour productivity exceeds the rate of growth of capital intensity, so that y/kp is rising. Periods in which smaller increases in capital intensity lead to larger increases in productivity are characteristic of periods of innovation with very widespread application across all sorts of products and processes (for example, the development and use of electric power, or the development of semiconductor industries).

Conversely, the rate of growth of capital intensity might exceed the rate of growth of labour productivity, so that y/kp is falling. Periods in which increases in capital intensity lead to rather smaller increases in productivity are characteristic of periods of innovation in which it is increasingly difficult to extract increases in labour productivity; new technologies are not widely generalizable and are much more product and process-specific. This can be equivalently characterized by noting that y/kp is the inverse of the ratio of “dead” to living labour. Then if capital intensity is rising faster then labour productivity, the ratio of dead to living labour is rising, so that technical change is capital-using and labour-saving. This particular relationship between changes in capital intensity and changes in labour productivity is typical of much of capitalism’s history (Marquetti, 2003).5 But it is evidently not the only possible relationship.

Multiplying the ratio y/kp (or equivalently Y/Kp) by the proportion of the capital stock that is productive (Kp /K) yields the ratio Y/K, called “capital productivity”.6 So capital productivity expresses first, the relation between capital intensity and the labour productivity it generates; and second, what proportion of the capital stock is worked by productive labour. But there is no automaticity in the direction of change in either of these expressions. For example, increases in labour productivity have to be extracted, and precisely how this is done depends not only upon technological development but also upon the balance of class power in the workplace. So the forces of production are developed under capitalist relations of production, and are expressed by capital productivity and its movements through time.

Capital productivity in the US economy for the period 1890 to 2010 is depicted in Figure 10.1, along with its trend.7

In broad trend terms, capital productivity was falling from 1890 to 1916. It then rose for half a century to the mid-1960s, with two short interruptions, one due to the 1929 crash and its immediate consequences, and the other due to the post-1945 transition to a peacetime economy after the exceptional mobilization of resources for World War II. After the mid-1960s, there was a substantial fall until 1982, in turn almost completely reversed by a rise until 2000, when a further sharp fall began. Two features are worth emphasizing. First, the whole period after World War II had higher levels of capital productivity than the whole period before. Second, sustained periods of broadly falling capital productivity were confined to just three periods: 1890–1916, 1966–82 and 2000–9, so that only about a third of the whole period 1890–2010 was characterized by Marx-biased technical progress in which capital intensity rose faster than the labour productivity it induced. The step-change from the early-1930s to the early-1940s, the first half of the 1960s and the two decades after 1980 were all periods in which labour productivity rose faster than capital intensity.

Capitalism requires the existence of a property-less class whose members are forced into the market to sell the only asset they possess (their capacity to work). Movements in the value of labour-power therefore provide an indication of the state of class relations, or, equivalently, how much surplus-value in money terms accrues to those who employ the working class. For, expanding equation (5) and using equation (8),

|

(9) |

so that the value of labour-power depends upon the ratio of the real product wage rate (of productive labour) to labour productivity. Consequently, the value of labour-power will fall (rise) if the real product wage rate is rising less fast (faster) than productivity.

A falling value of labour-power entails a rising rate of surplus value, a rising share of money surplus value in money value added and growing class inequalities. For a given level of employment, there is a growing quantity of surplus-value, which must be invested if it is to be accumulated as capital. If it is not, then it is either hoarded as idle balances, or is used for speculation as money attempts to create more money without the intermediation of production. This possibility might be summarized as “underconsumption” (wages are too low to support the demand that accumulation requires). The other possibility is that the value of labour-power is not falling, so that the total quantity of surplus value, the rate of surplus value, and the share of money surplus value in money value added are all non-increasing. From the perspective of capital, this involves an undesirable strengthofthe working class, with “too little” surplus valuebeing produced relative to the amount ofcapital invested, and hence an “overproduction”of capital relative to surplus value.

Since money surplus-value is net money value added less the wages paid to productive labour, then in terms of share

|

(10) |

The money surplus value share is hence an index of capitalist relations of production, but it is not independent of the forces of production. This is because of the latter’s role in determining first, the technological possibilities for productivity increases which impact upon the value of labour-power; second, the technologies of circulation which speed up turnover (such as the evolution of “just-in-case” into “just-in-time” methods of distribution and inventory control); and third, the technologies of supervision and surveillance.

Subtracting the unproductive wage share Wu/Y from both sides of the first part of equation (10), and noting that MSV = Y − Wp and W = Wp + Wu,

|

(11) |

so that the profit share is the money surplus value share less the unproductive wage share. Figure 10.2 shows the profit share for the US economy from 1890 to 2010.

In long run terms, the profit share fell. While there were a number of episodes of small rise, and a violent fluctuation from 1926 to 1941, nevertheless the whole period was broadly characterized by a falling share to 1982, and thereafter a barely rising share.

In terms of the money surplus value share, Figure 10.2 is not very informative, because there is no separate information about the unproductive wage share.8 Yet the profit share is commonly taken as an index of the relations of production, since “wages” are paid to labour and “profits” to capital. A generally falling profit share is taken as an indicator of the rising strength of labour, a sustained shift from capital to labour indicating increasing working class strength relative to capital (only marginally reversed in the era after 1980). In this manner, the profit share is interpreted as a class category.

But this is a muddle. The profit share is what remains of money value added after subtracting the wage share, and wages include the labour income of top echelons of management in the same way as they include the labour income of the workers who clean the offices of top management: both receive “employee compensation”. Saez (2012, Table A7) reports the composition of income within the top decile of the income distribution of household tax units. In 2007, for example, over the bottom half of the top decile, wages on average accounted for 88.6% of total income; for percentiles 95 to 99, 80.1%, and for the top percentile 54.3%. Even in the top one hundredth of the top decile, wages were 38.1% of income, averaging $7.35 millions (in 2010 prices). Wages measured by employee compensation are too inclusive a category to be of use as a class category, so that profits substantially underestimate non-working-class income. This problematizes both the conventionally defined profits share and the conventionally defined profit rate, if they are to be of any use in constructing an interpretation of US economic development in terms of class and class conflict. The latter require in the first instance a more nuanced understanding of “wages”.

Marx famously wrote,

… individuals are dealt with here only in so far as they are the personifications of economic categories, the bearers of particular class-relations and interests.

Marx Capital I, 1976 [1867], p. 92

Personifying the capital relation is impossible in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA), because it is impossible to distinguish just who are the bearers of the economic category of capital. And yet within the labour process it is obvious to both blue-collar and white-collar workers who bears that relation: employment is typically participation in a structured hierarchical and authoritarian network of relationships, and the work performed and compensation received are very different in different parts of that hierarchy. Following Marglin (1974), this suggests distinguishing class categories in the labour force by the criterion of control over the work of others.9 Defining those who are so controlled as “working class”, those who do the controlling are then “supervisors”. Most of the latter will not be directly capitalists in the sense of having sufficient resource to avoid the compulsion of selling their labour-power, although some will be. But regardless of that, all supervisors are structurally the de facto bearers of the capital relation because they supervise the labour of the working class.

Pursuing this, first note that unproductive wages comprise the wages of circulation workers (Wuc) and the wages of those who supervise and control both productive labour and circulation labour (Wus). Hence the wage term in equation (11) can be expanded so that

|

(12) |

Equation (12) can then be transformed into one denoting class shares by adding the supervisory wage share to both sides, so that

|

(13) |

Hence, the working class share is the total production worker wage share (Wp + Wuc/Y), and the non-working-class share is the sum of the profit share and the supervisory wage share (Π + Wsu/Y). This latter will henceforth be called the “supervisory plus capitalist class share” in a binary class model there is no other possibility.10

Shares are constructed by combining NIPA data with data from the Employment, Hours and Earnings Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which has (non-farm) data on employment, hours and earnings, disaggregated according to whether supervisory functions above shop-floor level are a part of the job. So define “production workers” as production workers in mining and manufacturing, construction workers in construction, and non-supervisory workers in service-producing industries; “supervisory workers” are then the remainder.

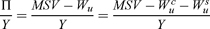

Production workers comprised 88.6% of all in employment in 1948; this figure fell slowly to 82.1% by 1970, and remained around that level thereafter (a mean of 81.0% and standard deviation of 0.68 percentage points between 1970 and 2010). More significant, however, than their numerical strength is how much they were paid. From 1948 to 1973, production workers’ employment share fell by 6.2 percentage points, and their wage share of money value added fell by 5.4 percentage points. From 1973 to 2007, while their employment share remained roughly constant, their wage share of money value added fell by 10.4 percentage points. This large change throws some light on the effects of class struggle. Table 10.1 shows the shares in value added in 1948 (the beginning of the “golden age”), 1966 (the year of peak profitability post-1945), 1979 (the year ending in the Volcker interest rate rise) and 2007 (the year beginning the Great Recession).

In both the “golden age” years to 1966 and the years after 1979, what share of value added production workers lost, supervisory workers gained. But in the 15 years after 1966, the supervisory wage share rose almost entirely at the expense of the profit share. As is often remarked, these were the years of “profit squeeze”, but it is less often remarked that the squeeze was by supervisory workers, not production workers: supervisory workers were taking more money surplus value as labour income, squeezing profits in the process.

Table 10.2 displays another way of looking at the growth of inequality, showing average labour income as a proportion of the average income of a production worker, for supervisory workers (in italics) and at various percentiles of the wage distribution reported by Saez (2012).11

| Levels | 1948 | 1966 | 1979 | 2007 |

| Production wage share | 53.5 | 46.8 | 47.3 | 37.6 |

| Supervisory wage share | 14.9 | 21.3 | 25.6 | 34.5 |

| Profit share | 31.7 | 31.9 | 27.1 | 27.8 |

| Δ% (percentagepoints) | 1948–66 | 1966–79 | 1979–2007 | |

| Production wage share | −6.6 | 0.5 | −9.6 | |

| Supervisory wage share | 6.4 | 4.3 | 8.9 | |

| Profit share | 0.2 | −4.8 | 0.7 |

Table 10.2 Average labour income relative to the average labour income of a production worker, USA, selected dates and percentiles

Interpreting Table 10.2, the average income of a supervisory worker was 2.2 times that of a production worker in 1948, 2.3 times in 1979, and 4.2 times in 2007. From 1948 to 1979, average supervisory worker income, relative to that of a production worker, grew by an average of 0.27% p.a., and from 1979 to 2007 at more than 10 times that rate, by an average of 2.8% p.a. Broadly, 1979 was very little different from 1948, but 2007 was very different from 1979, particularly the higher the percentile of the income distribution considered. Thus, trends in how much supervisory workers were paid were similar to what happened at the top percentiles of income distribution.12

Deriving a longer run picture is more speculative, because of the paucity of data, and its construction from 1947 back to 1909 requires some strong assumptions (sketched in the Appendix). Figure 10.3 depicts the results, showing the various shares of money value added and their long run trends: the working class share (northwest quadrant), the supervisory wage share (northeast quadrant), the profit share (southeast quadrant) and the non-working-class income share, (southwest quadrant).

The scales in each quadrant are dimensionally the same for comparability. Since the working class wage share, the supervisory wage share and the profit share sum to unity, the working class wage share and the non-working-class income share in the left-hand quadrants are the mirror images of each other.

The proximate reason for the rise in working class wage share from 1922 to a peak in 1949, and its sustained fall after 1949, is determined by equation (9), written in terms of production workers. Table 10.3 shows these proximate underlying determinants.13 From 1922 to 1949, the annual average rate of growth of the real annual wage of a production worker substantially exceeded productivity growth, whereas after 1949 this relationship was reversed, annual average real wage growth halving and annual productivity growth increasing by 50%. Hence prior to 1949 the non-working-class income share fell, whereas after 1949 it saw a substantial increase.

In Figure 10.3, the left-hand quadrants display periods when class shares were relatively flat. From 1926 to 1931 the working class wage share increased by just 1.85 percentage points, whereas the supervisory wage share rose by 9 percentage

Table 10.3 Labour productivity and the real wage, USA, selected dates and annual average rates of change; US$2005

points and the profit share fell by 10.8 percentage points. The flat period in shares from 1966 to 1979 is clearly visible, whereas the right-hand quadrants display a falling profit share andarising supervisory wage share, and thus a profit squeeze by supervisory workers, as already illustrated in Table 10.1 above. A third episode of flat class shares occurred over the decade after 1992, when movements in the profit share were roughly balancedbyopposite movementsin the supervisory wage share so that in particular the years of the dot.com boom and bust were also characterized by supervisory wages squeezing profits.In termsofshareofaggregate value added, it was as if capitalists qua supervisory workers first struggled over what they paid their workers, and then looked at what was left. When they had the power to do so, this determined how much labour income they could take for themselves, leaving the residual as profits. Sometimes that power was so pronounced that the supervisory wage share increased directly at the expense of the working class wage share, as in the years 1979 to 1992.

But they did not always have that power. From 1932 to 1940, class shares were relatively flat, but the supervisory wage share collapsed by 15.1 percentage points as the profit share recovered from its nadir of 1932. And from 1940 to 1944, the supervisory wage share fell by a further 6.9 percentage points as the profit share rose further in the war time economy. Over the two decades after World War II, it might appear that the supervisory wage share rose at the expense of the working class wage share. But this is misleading. Suppose there had been constant proportionsofclassintotal employment (rather than the fallinproduction workers’ employment share by 6.2 percentage points from 1948 to 1973). What would have happened to the non-working-class income share if the production workers’ employment share had remained constant at its 1948 level, but everything else had changed as it in fact did? After constructing counterfactual production worker wages, and subtracting from total wages to determine counterfactual supervisory wages, adding the actual profits share gives the counterfactual non-working-class income share. From 1948 to 1960, this counterfactual share averaged 46.7%, with a standard deviation of 0.54 (compared with the actual figures of 48% and 1.2, respectively.) The low standard deviation for the counterfactual share indicates an approximate relative constancy of non-working-class income share from 1948 to 1960. Thereafter, through to 1966, both hypothetical and actual non-working-class income share rose by more than3 percentage points becauseof a rising profit share.

All of this suggests that the changes posited by the New Deal were institutionalized and consolidated by the wartime economy into a (weak) form of social democracy, producing a flatlining of the non-working-class income share (assuming constant proportions of class in total employment) which was both unlike the pre-war experience and unlike the post-1979 experience. Since proportions of class in total employment were roughly constant after 1973, Figure 10.3 sharply indicates the striking changes in class share after 1979, to such an extent that the actual non-working-class income share under neoliberalism surpassed its 1929 level in 1988 and its peak 1916 level in 2003. Three years into the crisis that began in 2007, the non-working-class income share remained higher than its 1916 level.

In terms of theory, it should be noted that the non-working-class income share is not the money surplus value share. For the non-working-class income share is given by equation (13):

whereas the money surplus value share is evidently

|

(14) |

An analysis based on class and a strict value analysis are not the same, because production workers located in circulation activities are members of the working class but produce no value. Data to measure their wage share is only available from 1964, and, from 1964 to 2010, it averaged 12.8%, with a standard deviation of 0.335. This (surprising) constancy of the wage share of production workers in circulation activities implies that that the money surplus value share, while different in level from the non-working-class income share, is almost identical to it in terms of time path. A scatter of the money surplus value share against the non-working-class income share yields an R2 of 0.99; that of the money surplus value share against the profit share yields an R2 of 0.14 (and with the wrong sign). Hence the non-working-class income share is an excellent proxy for the money surplus value share (at least for the 46 years to 2010).

The forces of production and the relations of production together are reflected in movements in capital intensity, the real product wage rate, labour productivity and the division of the employed labour force (and hence the capital stock) into productive and unproductive components. Development of the forces of production is summarized in movements of capital productivity, and the relations of production in movements of the relevant income share. Combining forces and relations of production into one single index generates the (macroeconomic) rate of profit as the key summary statistic for evaluating trends in capitalism. But this is dependent on what is taken as the relevant income share, the profit share or the non-working-class income share.

Conventionally, the relevant income share is taken as the profit share, so that the macroeconomic rate of profit r is determined as

|

(15) |

Its timepath and trend from 1890 to 2010 are depicted in Figure 10.4.

In trend terms, the rate of profit was fluctuating. From 1890 to around 1916, the trend was falling, followed by a decade of rising trend. There was then a collapse into the Great Depression, and a strong recovery through to 1944. After a small fluctuation this peak (in trend terms) was revisited in the mid-1960s. Thereafter, the trend was falling until the early 1980s, and it then rose modestly to the end ofthe century. These movements are broadly the same as the movements in capital productivity in Figure 10.1. Moreover, since the profit share was generally falling, its downward trend amplified the effects of downward movements in capital productivity on the rate of profit, and dampened the effect of upward movements.

Since profits (after tax) are partly distributed and partly retained, with retained earnings plus borrowings financing investment, and since investment determines capital accumulation, then it seems obvious to try to relate trends in profitability to patterns of accumulation. High levels of profitability would be associated with high rates of growth, and declining profitability with increasing difficulties in accumulation. Indeed, much Marxist theory goes further, and insists on a focus on downward movements in the rate of profit as the cause of crisis (even if theory is undeveloped on the precise mechanisms whereby falling profitability results in crisis).

Figure 10.4 The rate of profit, USA, 1890–2010.

There are two difficulties with this. First, the time-frame of analysis requires better specification. The declining profitability of 1926–29 and 2004–7 were shortrun processes, in each case at the end of a longer period of substantial rise. The decline of 1966–79 was a much longer run process. Hence a unified empirical explanation, covering all three periods of declining profitability preceding crisis, is challenging. Second, if the rate of profit is to summarize forces and relations of production in a class-divided society, then the rate of profit as determined in equation (15) is not an adequate statistic, because the profit share as a class income share is incorrectly specified.

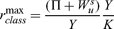

If the relevant income share is taken to be the non-working-class income share, then the “maximal class rate of profit” (rclassmax) is determined as the product of this non-working-class income share, and capital productivity.14

|

(16) |

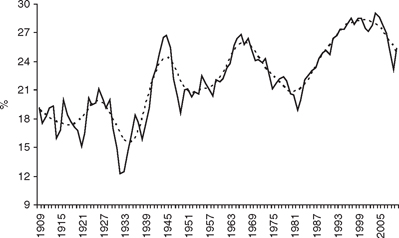

Its timepath is shown in Figure 10.5.

In contrast to the understanding informed by the rate of profit in Figure 10.4, a sharp focus on class indicates that the history of US capitalism is one of fluctuations in the maximal class rate of profit along a rising path. Until 1949, the non-working-class income share was falling. Over this period, falling capital productivity had an amplified effect on the maximal class rate of profit, and rising capital productivity a dampening effect. After 1949, this was reversed: the non-working-class income share was generally rising, amplifying the effects of rising capital productivity on the maximal class rate of profit, and dampening the effects

Figure 10.5 The maximal class rate of profit, USA, 1909–2010.

of its downward movements. Nevertheless, compared with the rate of profit in Figure 10.4, while the trend is quite different, the maximal class rate of profit fluctuated in a similar manner, with the same peaks and troughs. So it is worth investigating further whether movements in the conventional and maximal class rates of profit are similarly associated with subsequent crisis.

“Crisis” is a notoriously overused word. Of medical origin, its precise meaning encapsulates an event (or set of events) following which there is a decisive change for better or for worse. Inspection of Figure 10.5 shows six significant downturns (more than a 3 percentage points fall) in the maximal class rate of profit between 1910 and 2010: 1913–14, 1916–21, 1926–32, 1945–49, 1966–82 and 2004–9. Two of these episodes were characterized by demobilization and the transition to a peacetime economy (1916–21, 1945–49); that of 1913–14 was prompted by a decline in railway profits, fears of credit restrictions on the establishment of the Federal Reserve System, and the cutting off of export markets to Europe (Flamant and Singer-Kérel, 1970); and the remaining three saw major crises erupt in the autumn of 1929, the autumn of 1979, and the late summer of 2007. Is there then an empirical regularity: do short run falls in the maximal class rate of profit precede crisis, and is this different from falls in the conventional rate of profit?

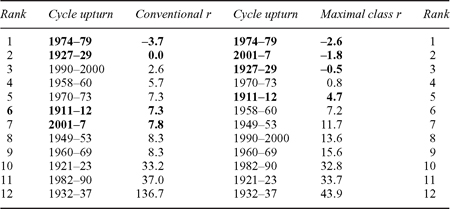

Consider the trough to peak years of US business cycles.15 Profitability ought to be rising in an upturn, implying increasing difficulties if it is not. Table 10.4 ranks cycle upturns according to the rate of growth in the two rates of profit, conventionally defined and class defined. It omits the war-affected upturns of 1914–18, 1918–19, 1938–44 and 1945–48 on the grounds that economies mobilized for military production create conditions of abnormal profitability (and

Table 10.4 Ranking of NBER cycles (peak to peak) by percentage fall in the rate of profit

demobilization years, the reverse) which are untypical of “normal” capitalist development.

Table 10.4 provides some evidence of the causal efficacy of rates of profit in predicting crisis. For, consider movements in the maximal class rate of profit. A falling rate preceded major crisis in each of the peacetime cyclical upturns immediately prior to the crises of 1929, 1979 and 2007, and there was no other peacetime cyclical upturn with a falling maximal class rate of profit. These falls, being percentage falls rather than percentage points falls, were small. It would be therefore be more appropriate to say that stagnation of the maximal class rate of profit during a peacetime cyclical upturn invariably preceded a major crisis. The 1970–73 upturn marking the end of the “golden age” must then be considered. There had certainly been intimations of crisis, as the war in Vietnam was lost amidst domestic political turmoil, and international instability, as the dollar’s link to gold was broken and the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates collapsed. But the end of the “golden age” produced political stasis rather than crisis and crisis resolution; while stagnation of the maximal class rate of profit in the 1970–73 upturn was part of the run-up to the crisis of 1979, that crisis itself took a further six years to break. Finally, the upturn of 1911–12 can similarly be incorporated into a stagnationist thesis. Hence there is indeed an empirical regularity: peacetime cyclical upturns in which the maximal class rate of profit increased by less than 5% culminated in crisis, and no crisis occurred in the absence of such stagnation. In terms of movements of the conventional rate of profit during cyclical upturns, those of1974–79 and 1927–29 might imply a similar stagnationist thesis. But this is not true for either the upturn of 1911–12 or that of 2001–7. In particular, the 2007 crisis is inexplicable in terms of movements in conventional profitability. A stagnationist thesis for the conventional rate of profit cannot therefore be empirically defended.

This is, however, a weak result. It is restricted to cyclical upturns as defined ex post by the NBER. If every three year change in profitability is calculated and ranked, no such pattern as displayed in Table 10.4 emerges. Similarly for the ranking of every two year change in profitability. There is therefore no general sense in which a short run falling rate of profit (however defined) empirically results in crisis.

In what effects does stagnation in the maximal class rate of profit manifest itself? Crises are sufficiently infrequent as to provide only a very small sample for study, and generalization is therefore hazardous. But some features are clear. In both the crisis of 1929 and the crisis of 2007–8, a background of increasing international imbalances was an important feature. So too was speculation fueled by credit and bubbles in asset markets. The two were closely related, as international surpluses financed the credit which fuelled speculation.

Of course there were major differences. In the 1920s, imbalances were created by the way in which reparation payments (US loans enabled Germany to pay its reparations to the war victors, who used the proceeds to repay their wartime loans from the US) interacted with a structure of gold standard fixed exchange rates in which some currencies (such as sterling) were overvalued, and others (such as the French franc) undervalued. The crisis of 1929 broke out in the stockmarket, where speculation had been fuelled by credit as brokers’ loans financed clients’ purchases on margin. Loans at call could be called at no notice, and once foreign loans to the US market were called in October 1929, credit rationing to preserve the profitable market in brokers’ loans created severe difficulties in goods markets that depended on easy credit, such as autos, whose production had peaked in March 1929. Credit restrictions also impacted quickly on commodities’ prices, because most inter- and intra-country trade depended on very short term bank credit to finance the transport and storage of finished goods prior to their sale. As trade credit was reduced, sellers who could neither store goods nor divert them elsewhere were forced to cut prices, often dramatically. Hence bankruptcies were spread, both in the US and internationally, first in commerce, then in production and finally in banks (Kindleberger, 1984, Temin, 1989).

In the “noughties”, some countries (oil exporting, Germany and especially China) had accumulated large current account surpluses, and others (the US and the UK) large current account deficits. Because the Chinese exchange rate was highly managed, Chinese surpluses were accumulated as central bank reserves, and invested mostly in US Treasuries. The consequence was a fall in real risk-free medium- and long-term rates of interest to historically low levels (roughly halving in the 15 years after 1990). This had three effects (Turner, 2009). First, there was a rapid growth in credit, much of which found its way into the housing market, fuelling a housing price bubble. Second, on the demand side, investors were eager in an era of historically low returns to purchase any financial asset that appeared to yield more return, especially if that return could be gained apparently without assuming extra risk. And third, on the supply side, financial institutions invented, packaged, and traded a variety of securitized credit instruments claiming to disperse risk, which were eagerly purchased. These instruments were increasingly complex, allowing both the hedging of underlying credit exposures, and the creation of synthetic credit exposures which could then be further hedged. But the complexity of these instruments concentrated rather than dispersed risk. The crisis of 2007–8 broke out in wholesale money markets, as lenders were increasingly reluctant to accept securitized bonds as collateral, because of uncertainty as to the extent of their contamination by securitized subprime mortgage derivative bonds after the burst in the bubble in house prices the previous year.16 The uncertainty then spread to the market in commercial paper, in which borrowers seek to finance their short-term activities (such as payroll), and, once funds dried up, deleveraging was forced, and crises of liquidity and solvency were inevitable.

As well as involving international imbalances and leveraged speculation, the crises of 1929 and 2007–8 erupted in situations in which inequalities had been growing. Production worker wages were too low to support the levels of demand that would warrant the levels of investment that could increase the rate of accumulation. In the late 1920s, leverage was used to finance stock market speculation. In the “noughties”, while inadequate wages were boosted by the expansion of consumer debt, accumulation remained “jobless”, and leverage was used by finance, through securitization, to speculate in increasingly opaque financial derivatives resting on house price appreciation. Once the crisis broke, credit restrictions quickly impacted on the real economy, and in each case aggregate demand fell sharply. The short run fall in class profitability was thereby exacerbated.

However, the crisis of 1979 was different. It was not precipitated by a confidence-shattering market collapse (as in 1929 and 2007–8). It was rather precipitated in October 1979 by a major change in US interest rate policy, as the Federal Reserve Board under Volcker tried to squeeze inflation out of the system with a high real interest rate policy. While the transition from the fixed exchange rate world of Bretton Woods to an era of floating exchange rates had created difficulties in the 1970s, relative capital immobility (compared with the 1920s and the “noughties”) precluded serious speculative excess. The economy was too regulated to allow of a market resolution, so that the crisis mechanism was essentially political and not economic.

While short run stagnation in the maximal class rate of profit is a harbinger of crisis, there are also long run features of crisis. For the market-based crisis of 1929 and the politically induced crisis of 1979 proved similar in one crucial respect: resolution of the crisis in each case led to régime change. After 1929, this took some considerable time, as the framework laid down by the New Deal was then overlaid by the transition to a wartime regulated economy. Many of the elements of this regulated framework were carried forward into the postwar years. Currency, credit and financial institutions remained heavily regulated, both nationally and, under US tutelage, internationally. While private ownership remained fundamental, the era was characterizedbyguaranteesoffull employment (sometimes implicit, sometimes explicit), the development of state-sponsored social protection mechanisms, active state interventions in industry, an (often grudging) acceptance of the legitimacy of labour unions and collective bargaining, and generally rising living standards. There was also a very substantial reduction in inequalities to a level that was maintained for the 20 years to the early 1970s. In this manner, the free market era dominated by finance up to 1929 was succeeded by a (more or less) social democratic era dominated by “managerialism”, a culture of actively managing capitalism through constraints on the operation of market forces.

But as the “golden age” came to an end, the regulatory structures that had underpinned it were increasingly questioned. Beginning in the late 1960s, and with gathering momentum through the 1970s, there was a recognition of the end of an era, but considerable confusion as to what might replace it, and no resolution of what had come to be seenas its fundamental problems. Labour unions were increasingly seen as too powerful as they attempted to maintain real wages; at the same time oligopolistic firms attempted to maintain profitability. Demand management policies were problematic; managerial interests wanted buoyant demand, and hence the monetary accommodation of inflationary pressures, whereas financial interests wanted monetary contraction via higher interest rates. This stalemate played out as “stagflation”, but increasingly the view took hold that the regulatory state had to be rolled back. There was no inevitability about this. But those who wanted to defend the old order were often members of defensive institutions (such as labour unions) who were dismissed as the anachronistic defenders of sectional interests, relics from an era no longer relevant. Following the credit tightening of October 1979, inflation peaked in the spring of 1980, and in November 1980 Reagan was elected President. By 1982, the deregulation movement was proceeding apace, with state-sponsored and successful attacks on labour union resistance, and the dismantling of what were seen as excessive regulatory structures particularly in banking and finance. Increasingly, the market was celebrated as the only legitimate arena of social activity, and money as its the only measure. In this manner, finance restored its prerogatives of the pre-1929 era over the managerialism of the “golden age”.

The crisis of October 1979 thus initiated régime change, and with a much faster transition than after 1929. After 1929 the transition to the “golden age” took a long time because there was no clear manifesto driving the transition. People knew what they did not want, and the structures eventually put in place were reactive in this manner, as well as shaped by the changed international conditions during and following World War II. By contrast, the transition to what became called “neoliberalism” was rapid once the crisis was initiated. Its agents knew exactly what they wanted, whereas the defenders of social democracy were increasingly compromised by their defence of the structures of a “golden age” that had in fact ended 10 years before. Globalization and financialization accordingly swept away the era of social democracy, restoring the hegemon of finance. And history then rhymed, as 2007–8 recalled 1929.17

This chapter has proposed that in order to comprehend the development of US capitalism, class categories must be constructed that can be used empirically. Proceeding on the basis of a particular interpretation of the labour theory of value, it finds that, for the US economy, the maximal class rate of profit has a marked long run tendency to rise, in contrast with the conventionally defined rate of profit. The difference between the two is determined by the addition of supervisory wages to the numerator. In a binary class model, there is little else one can do. An obvious direction for further research is to render the underlying model richer, by empirically distinguishing capitalist class wages from non-capitalist supervisory wages. Then three wage shares could be measured: the working class wage share, the capitalist class wage share and the non-capitalist supervisory wage share, the last being loosely a managerial wage share. That would enable some escape from the awkward neologisms of “non-working-class income share” and “maximal class rate of profit”, through a direct identification of the capitalist class share and the corresponding class rate of profit. The time trend of this class rate of profit will lie somewhere between the conventional rate of profit, in which capitalists have no labour income, and the maximal class rate of profit, in which all supervisory wages are treated as capitalist labour income.

While that is for future research, the binary class model developed here has shown a dynamic capitalism structured around the increasing extraction of money surplus value, with rare but dramatic interruptions by crisis. These crises follow short run stagnation in the maximal class rate of profit from trough to peak of the (peacetime) business cycle. Market-based crises (1929, 2007–8) are initiated by a speculative crash. “Too much” surplus value is produced relative to demand, and, since wages are too low because of rising inequality, surplus value is channelled into speculation rather than investment. In a regulated economy, by contrast, crisis has to be politically induced (1979), which requires a permissive ideological context and a willingness to exert the prerogatives of class power. Either way, resolution of crisis requires régime change.

US capitalism has seen a number of régime changes. The formation of a national banking system was a successful systemic response to falling capital productivity. Free markets in an unregulated environment were eventually regulated into a form of social democracy, which harnessed and consolidated rising capital productivity until the mid-1960s. The subsequent 15 years of falling capital productivity were successfully reversed by the transition to neoliberal finance and deregulation at the end of the 1970s. Falling capital productivity in the early twenty-first century appears to require some further change in capitalist relations of production.

From 2010 onwards, the crisis that began in August 2007 became a sovereign debt crisis. While history suggests the necessity of régime change, it also suggests that the transition will be protracted and unstable, because there is little consensus as to the direction of travel. For the revivalism of free markets has served greatly to weaken the progressive forces of the labour movement, both materially and ideologically, and it seems likely that the capital relation will be preserved. Then the transition in the coming years is likely to revolve around how far financial and managerial interests within capital are inseparably fused, versus how far they can be separated in such a way that managerialism sees its interests as best served by some accommodation with the mass of working people.

The data are derived from the National Income and Product Accounts (August 2011) and the Fixed Asset tables (August 2011), published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis at <http://www.bea.gov>; the Employment, Hours and Earnings data, published by the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) at <http://www.bls.gov>; Kendrick (1961); Lebergott (1964); Bureau of the Census (1949, 1966, 1975, 2006), and Carter et al. (2006); and the Internal Revenue Service, as reported by Saez (2012). Following Shaikh and Tonak (1994), BLS categories are mapped on to NIPA data in the manner described by Mohun (2005, 2006).

National accounts provide measuresofvalue added, but these are typicallyahybrid combination of use-value and value. They not only measure everything (legal) that goes through the market; they also measure activities for which there is no market price. Activities that are not marketed are not (Marxian) value-creating. The two most important examples are the outputofgeneral government (whichisaccounted for by general government employee compensation), and a variety of activities, which, because they do not take measurable monetary form, are given an imputed monetary value.

These imputations are substantial, amounting in the US to 14.9% of GDP in 2007. The largest imputation (45.4% of all imputations) was the rental value imputed to owner-occupied housing, followed by employment related imputations (27%, the vast majority being employer contributions for health and life insurance), then consumption of general government fixed capital (11.6%), and then financial services furnished without payment (11.5%).18 In general, from a Marxist perspective of the production of value and surplus value that can be accumulatedas further capital, these imputations should be excluded, because they are not market transactions. But some imputations are different, in that they are not invented, but redirected, so that their consumption is attributed to the recipient rather than the payer. Employer contributions for health and life insurance fall into this category, and in principle comprise part of employee compensation and so part of the value of labour-power.

Hence value added in money terms requires subtracting all imputations except employer contributions for health and life insurance, and subtracting general government employee compensation (net of imputations). The aggregate from which these are subtracted is net domestic product (NDP) rather than gross domestic product (GDP), because the focus is on new value created, whereas the consumption of fixed capital is a charge to replace the depreciated portion of the fixed capital stock. So value added in money terms is NDP less general government employee compensation (both net of all imputations except employer contributions for health and life insurance).19

Conceptually, profits comprise everything that is not wages, the residual after the subtraction of wages from Y. Pre-tax profits include both taxes on production and imports less subsidies, and taxes on corporate income. Profits also include interest and rent, specifically net interest and miscellaneous payments, business current transfer payments, and rental income of persons. Finally, they include the profits component ofproprietors’ income (estimated as all such income that is not alabour income, where the latter is proxied by the average labour income in each relevant industry or industry group). Hence, the notion of profits is a very inclusive one (but remains less than surplus value in money terms because it does not include unproductive wages).

The fixed capital stock is taken to be non-residential equipment, software and structures (at replacement prices), together with inventories. Since in principle any investment made in order to make money should be cumulated into a measure of the capital stock, tenant-occupied residential structures are also included. But owner-occupied residential structures are excluded,as is general government fixed capital. Fixed capital stock data are end-of-year figures, and so the rate of profit in year t is computed as profits in year t divided by the sum of inventories in year t and fixed capital in year t − 1.

The trends in Figures 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, 10.4 and 10.5 are determined by a nearest neighbour loess fit, using a polynomial of degree 2, and a bandwidth of 0.2. Choice of these two parameters determines the trend, and there is always a compromise between smoothness and capturing the peaks and troughs (Cleveland, 1993, ch. 3). The higher the bandwidth, the smoother the trend.

In calculating numbers of workers, an important caveat affects goods-producing industries. Whereas in all other (private-service-providing) industries, nonproduction workers are executive, managerial and supervisory workers, this is not true in mining, in which the category “production workers” not only excludes executive, managerial and supervisory workers, but also excludes those working in finance (including accounting, collection and credit), trade (purchasing, sales and advertising), personnel, cafeterias, and professional or technical positions (including legal and medical). Neither is it true in construction, which in addition excludes those working in clerical positions; and manufacturing, which, as well as all categories excluded in mining and construction, also excludes those working in product installation or servicing, recordkeeping not related to production, delivery as well as sales, and force account construction20 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009, Ch. 2, Concepts, and Appendix). This entails that “supervisory workers” in mining, manufacturing and construction include employees who do not perform supervisory functions. Since these three industries comprised 40.3% of employment in non-farm private industries in 1973, a proportion that had halved by 2007, the numbers of supervisory workers are overestimated, and by an indeterminate amount, although decreasing with the declining employment weight of mining, manufacturing and construction through time.

Data prior to 1948 are constructed on the basis of manufacturing data. The construction assumes that the ratio of production workers to total employment tracks the time path of that ratio for manufacturing.

The overestimation of the numbers of supervisory workers (in mining, manufacturing and construction) is likely to have the following effects. First, the effect on average production worker labour income will be small, because the categories of worker “wrongly” categorized as supervisory workers are likely to be paid similar wages on average as production workers. The denominators underlying the ratios displayed in Table 10.2 will not therefore be altered very much if more accurate measurements were possible. Secondly, it exaggerates the level of the supervisory worker wage share at the expense of the production worker wage share, for the latter will rise if there are more production workers. Thirdly, because trends in supervisory labour income are dominated by what happens at the top of the income distribution, the trend of the wage share in value added of supervisory workers is unlikely to be significantly altered. And fourthly, the average labour income (and the hourly wage rate) of a supervisory worker will be increased if lower waged numbers in mining, manufacturing and construction could be reclassified to “production worker” status. The numbers in the Supervisory row in Table 10.2 must therefore be considered very much as lower bounds at best.

Pre-1948 wages for each sector j are constructed on the basis of the manufacturing weekly wage, weighted by the NIPA ratio of average employee compensation for sector j to average employee compensation in manufacturing.

I am grateful to participants at the annual Analytical Political Economy Seminar (held at Queen Mary), and the London Seminar on Contemporary Marxist Theory for helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

1 The subscript p denotes “productive” throughout. Not all capitalist wage-labour produces value and surplus-value. That which does is called “productive”, whereas “unproductive labour” consumes rather than produces surplus-value. see for example Foley (1986, pp. 116–22).

2 Moseley (1991) and Shaikh and Tonak (1994) are partial exceptions, but their concern was primarily to measure Marxian variables, and then to relate their measures to the conventionally defined rate of profit. Hence their focus was directed to productive and unproductive labour, and not to class.

3 This approach was first broached in Mohun (2006).

4 While this thesis is most prominent in the work of Duménil and Lévy (2004, 2011), the supportive evidence presented here is differently constructed and has a different emphasis. see also Foley (2010) and Michl (2011).

5 Because it was the case on which Marx focused, it is sometimes called “Marx-biased technical change”.

6 This account is simplified. More properly, the deflator in equation (7) should be one appropriate to fixed capital, in which case Y/K is complicated by a ratio of deflators. But it is not necessary to pursue this here.

7 Data sources for all figures are given in the Appendix. The trend is a (“loess”) locally weighted least squares regression. see the Appendix for more detail.

8 The unproductive wage share has been investigated by Moseley (1991), Shaikh and Tonak (1994) and Mohun (2005, 2006).

9 Discussion of the separation of control from ownership has of course a long twentiethcentury pedigree.

10 I return to this in the Conclusion section.

11 Salary distribution percentiles are measured in terms of household tax units. This is a completely different basis of measurement from that of individual production and supervisory worker income. It is therefore remarkable how close the average labour income of the bottom nine deciles of the labour income distribution of tax units is to the average individual production worker wage.

12 Note that the 1948 and 1979 figures in Tables 10.1 and 10.2 are not incompatible. Table 10.1 concerns wage shares, while Table 10.2 concerns relative incomes. The changes in wage share are driven by changing wages and by a falling percentage of total fulltime equivalents of production workers through to 1966, but relative incomes barely changed.

13 This is a little loose. see the discussion following equation (14).

14 Because the supervisory plus capitalist class share is a good proxy for the money surplus value share (at least since 1964), the maximal class rate of profit is a similarly good proxy for a “Marxian rate of profit” (the ratio of money surplus value to the capital stock).

15 As dated by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Because the data of this paper are annual and NBER cycle turning points are by month, if the turning point is in January, February or March of year t, the turning point year is taken as year t − 1. Also, the cycle defined by the peaks of 1980 and 1981 is absorbed into the cycle beginning in 1979.

16 This was manifested as a run in the repo market as ever-increasing haircuts were demanded on collateral by lenders, until the market froze completely in August 2007. Over the following year, deleveraging effectively wiped out the shadow banking sector. see Gorton (2010).

17 The reference is to an aphorism attributed to Mark Twain: “History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme”.

18 The remaining 4.6% comprise the rental valueof non-residentialfixed assets owned and used by non-profit institutions serving households, premium supplements for property and casualty insurance, farm products consumed on farms, and margins on owner-built housing.

19 The flow of money to pay services such as those supplied by the servants discussed by Adam Smith should also be excluded, but in a developed capitalist economy these flows are very small (and are taken for the US to be represented by the category “private households”). All other money flows are attributable to the production of value.

20 Construction work performed by an establishment, engaged primarily in some business other than construction, for its own account and for use by its employees.

Brenner, R. (1998) “The Economics of Global Turbulence”. New Left Review 229: 1–264.

Brenner, R. (2002) The Boom and the Bubble. London and New York: Verso.

Bureau of the Census (1949) Historical Statistics of the United States 1789–;1945. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

Bureau of the Census (1966) Long Term Economic Growth 1860–;1965. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

Bureau of the Census (1975) Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Bicentennial Edition. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2009) Handbook of Methods. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office. Available at http://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/homch2_b.htm

Carter, S. B., S. S. Gartner, M. R. Haines, A. L. Olmstead, R. Sutch and G. Wright (eds) (2006) Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present: Millennial Edition. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cleveland, W. S. (1993) Visualizing Data. Summit NJ: Hobart Press.

Duménil, G. (1983) “Beyond the Transformation Riddle: A Labor Theory of Value”. Science & Society 47: 427–450.

Duménil, G., and D. Lévy (1993) The Economics of the Profit Rate. Aldershot UK and Vermont USA: Edward Elgar.

Duménil, G., and D. Lévy (2004) Capital Resurgent. Cambridge Mass. and London:Harvard University Press.

Duménil, D., and D. Lévy (2011) The Crisis of the Early 21st Century: A Critical Review of Alternative Interpretations. Paris: EconomiX, PSE.

Flamant, M., and Singer-Kérel (1970) Modern Economic Crises. London: Barrie & Jenkins.

Foley, D. K. (1982) “The Value of Money, the Value of Labour Power, and the Marxian Transformation Problem”. Review of Radical Political Economics 14: 37–47.

Foley, D. K. (1986) Understanding Capital. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Foley, D. K. (2010) “The Political Economy of Post-crisis Global Capitalism”Available at http://homepage.newschool.edu/∼foleyd/FoleyPolEconGlobalCap.pdf

Gillman, J. M. (1957) The Falling Rate of Profit. London: Dennis Dobson.

Gorton, G. B. (2010) Slapped by the Invisible Hand. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kendrick, J. W. (1961) Productivity Trends in the United States. National Bureau for Economic Research.

Kindleberger, C. P. (1984) A Financial History of Western Europe. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Lebergott, S. (1964) Manpower in Economic Growth. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Marglin, S. A. (1974) “What Do Bosses Do? The Origins and Functions of Hierarchy in Capitalist Production. Part 1”. Review of Radical Political Economics 6: 60–112.

Marquetti, A. A. (2003) “Analyzing Historical and Regional Patterns of Technical Change from a Classical-Marxian Perspective”. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 52: 191–200.

Marx, K. (1976b [1867]) Capital I. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Marx, K. (1981 [1894]) Capital III. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Marx, K. (1987 [1859]) A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. In Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Vol. 29. Moscow: Progress Publishers, and London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Michl, T. (2011) “Finance as a Class?”. New Left Review 70: 117–125.

Mohun, S. (1994) “A Re(in)statement of the Labor Theory of Value”. Cambridge Journal of Economics 18: 391–412.

Mohun, S. (2005) “On Measuring the Wealth of Nations: the U.S. Economy, 1964–;2001”. Cambridge Journal of Economics 29: 799–815.

Mohun, S. (2006) “Distributive Shares in the U.S. Economy, 1964–;2001”. Cambridge Journal of Economics 30: 347–370.

Moseley, F. (1991) The Falling Rate of Profit in the Postwar United States Economy. New York, St. Martin’s Press.

Saez, E. (2012) Tables and Figures Updated to 2010. Available at http://elsa.berkeley. edu/∼saez/

Shaikh, A. M. (1999) “Explaining the Global Economic Crisis”. Historical Materialism 5: 103–44.

Shaikh, A. M. (2010) “The First Great Depression of the 21st Century”. In L. Panitch, G. Albo and V. Chibber (eds.), The Crisis This Time. Socialist Register 2011. London: Merlin Press and New York: Monthly Review Press.

Shaikh, A. M., and E. A. Tonak (1994) Measuring the Wealth of Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Temin, P. (1989) Lessons from the Great Depression. Cambridge Mass. and London: The MIT Press.

Turner, A. (2009) “The Turner Review. A Regulatory Response to the Global Banking Crisis”. London: Financial Services Authority.

Weisskopf, T.E. (1979) “Marxian Crisis Theory and the RateofProfit intheUS Economy”. Cambridge Journal of Economics 3: 341–378.