Table 18.1 Average number of employees per establishment and co-worker means for two-digit SIC manufacturing industries, 1967–1997

Source: Author’s computations from the Census of Manufacturing, 1967–1997

| 18 | Consequences of downsizing in U.S. manufacturing, 1967 to 1997 |

| Edward N. Wolff |

There has been much discussion of “downsizing” in the press. In this chapter, using Census of Manufacturing data, I explore whether such a pattern has characterized U.S. manufacturing over the period from 1967 to 1997, the period when downsizing received the most attention. I do find evidence of a decline in average establishment size over this period.1 Moreover, regression to the mean also occurred, with large establishments tending to become smaller (or to being replaced by smaller enterprises) and small establishments tending to expand, with the overall tendency being movement toward the middle.

A few words might be said about the notion of “downsizing” and the choice of period reviewed. In the popular vernacular, “downsizing” refers to the deliberate (or strategic) announcements of plant layoffs in order to gain media and/or Wall Street attention. Perhaps, the most egregious example was “Chainsaw Al” (Albert Dunlap) who obtained his nickname from the ruthless methods he employed to streamline ailing companies, most notably Scott Paper. Baumol, Blinder, and Wolff (2003, Chapter 2) provide extensive documentation of layoff announcements during the 1980s and 1990s in the U.S.2 I use the term “downsizing” here in the more mundane sense of a reduction in average establishment size within industry. However, using Census of Manufacturing data, I am unable to determine whether reductions in average establishment size came about due to a deliberate strategy of layoffs or due to other reasons for shrinking plant size.

My period of analysis covers the years 1967 to 1997. The choice of years is mainly dictated by data availability (as noted below, the U.S. industry classification scheme was changed in 1997). However, it is also the case that the years 1980–1997 were the heyday of the “downsizing” craze, so that my period of analysis covers the main period of downsizing. After 1997, popular concern switched to “outsourcing,” which involves a different set of issues.

The chapter explores some potential consequences of downsizing. First, I investigate whether there is any evidence that the act of downsizing increases the productivity of establishments. Second, I explore whether downsizing leads to higher profitability of firms. I also consider the effects of downsizing on average share prices of manufacturing stocks.

Third, I look into the association of downsizing with both employee compensation and unit labor costs. Downsizing might be a weapon in reducing wages, particularly if it reduces the relative employment of more senior employees or higher paid jobs. Reductions in establishment size might also lower wages simply through the well-documented employer size effect on wages: namely, that ceteris paribus, larger establishments pay higher wages (see, for example, Masters, 1969; Mellow, 1981; Idson, 1999).

The central story that emerges here is rather straightforward. First, on average, where downsizing has occurred in the manufacturing sector it has not contributed to productivity, contrary to what is frequently conjectured. Second, it has actually reduced profits. Third, downsizing by a firm has been associated with a decline in the price of its stocks, perhaps because it lowers profitability. In contrast, de-unionization is strongly associated with a decline in profitability, a reduction in stock prices, and a drop in worker compensation.

The remainder of the chapter is organized as follows. The next section reviews the pertinent literature. The following section provides theoretical motivation for the effects of downsizing on productivity and profitability. Descriptive statistics on changes in the size distribution of establishments in manufacturing are presented in the fourth section. The fifth section shows time trends of variables that may be affected by downsizing in manufacturing and this set of factors is formally analyzed in the sixth section. Concluding remarks are made in the last section.

Background on the downsizing phenomenon was provided by Lazonick (2009). He documented the shift in the basic corporate business model in the U.S. from about 1980 to the present, from an emphasis on stakeholder value to one on shareholder value. He called this new business model the “New Economy business model” or NEBM, which radically altered the terms on which workers were employed in the U.S. The rise of the NEBM is also connected to the widespread adaption and diffusion of information and communication technology (ICT). The “Old Economy business model” (OEBM) that dominated the U.S. corporate economy from the end of World War II and into the 1980s offered employment that was much more stable, and earnings that were much more equitable, than employment and earnings in the NEBM. In the OEBM, men (mainly men) typically secured a well-paying job right after college in an established company and then worked their way up and around the corporate hierarchy over the next three or four decades of employment. In the NEBM, an employee begins work for a company but that person has no expectation of a lifetime career with that particular enterprise. The NEBM set the stage for the phenomenon of downsizing that started in force in the 1980s. Insofar as companies no longer valued worker loyalty, workers were expendable if that increased the bottom line on their income statement.

Another concurrent development was the formation of global value chains, as documented by Sturgeon, Van Biesebroeck, and Gereffi (2008) for the automobile industry in North America. They found a growing tendency by firms to divide the process of producing goods and services, and to locate different parts of the production process in different parts of the world depending on costs, markets, logistics, or polities. The globalization of production is often described as “slicing up the value chain,” “outsourcing,” or “offshoring.” This process of outsourcing was predominant during the 1990s. Outsourcing put further pressure on globalized firms to downsize (domestic) employment.

A related trend was the growing “financialization” of the U.S. corporate economy. As discussed in Milberg (2008) and documented in Duménil and Lévy (2011), there has been a large increase in the financialization of the U.S. economy. This process has taken three forms. First, there is an increasing share of GDP accounted for by the financial sector. Second, gross international capital flows have grown much faster than world output. Third, non-financial firms have relied more heavily on finance than on production as both a source and use of their funds. Milberg focused on the third of these processes in his article.

The article connects growing financialization with the development of global value chains by U.S. non-financial corporations. Financialization was associated with a restructuring of production, with firms, in particular, focusing their production on their core competence. This new managerial strategy also became widespread around the same time — in the 1980s. This development exacerbated the shift to a focus on shareholder value. The focus on shareholder value and the formation of global value chains exerted further pressure to outsource production and to downsize (domestic) employment.

A similar argument is made by Stockhammer (2004). He also documented that from the 1980s through the 2000s, the financial accumulation of non-financial business was rising. He argued that financialization, the shareholder revolution, and the development of a market for corporate control shifted power away from other constituencies and to shareholders, and thus changed management priorities, leading to a reduction in the desired growth rate. Interestingly, he also provided evidence for the U.S., the U.K., France, and Germany that supported the negative effect of financialization on accumulation.

Two papers look at the effects of downsizing on productivity. Baily, Bartelsman, and Haltiwanger (1996) investigated why average labor productivity declines during recessions and increases during booms. One of their findings is that productivity tends to decline in plants that are downsizing — at least, during aggregate downswings. Collins and Harris (1999) used similar methodology to investigate the effects of downsizing on productivity in the U.K. motor vehicle industry over the period 1974–1994. They found that productivity growth was indeed higher in those plants that successfully downsized, but that those plants that were unsuccessful in downsizing tended to have among the worst productivity growth records. Unsuccessful downsizers accounted for a significant part of the overall decline in productivity in the U.K. motor vehicle industry after 1989.

Gordon (1996) argued that downsizing could reduce wages and salaries. He contended that a critically important source of falling wages has been U.S. corporations’ increasingly aggressive stance with their employees, their mounting power to gain the upper hand in those struggles, and the associated shift in the institutional environment. Two papers provided some evidence on this. Cappelli (2003) looked at the relationship between both job losses associated with shortfalls in demand and downsizing and subsequent financial performance. His results indicated, among other things, that downsizing reduced labor costs per employee. Espahbodi, John, and Vasudevan (2000) examined the performance of 118 firms that downsized between 1989 and 1993. They found that operating performance improved significantly following the downsizing, and, in particular, these firms were able to reduce labor costs.

Several papers looked into how stock prices reacted to downsizing. The evidence is mixed. Abowd, Milkovich, and Harnnon (1990) used an event study methodology to investigate whether human resource decisions of firms (such as staffing) announced in the Wall Street Journal between 1980 and 1987 discernibly affected either the level or variation of shareholder return. They found no consistent pattern of increased or decreased valuation in response to any of five categories of announcements of staff reduction, even after controlling for the likely effect of such announcements on total compensation costs.3 Abraham (1999) also used an event study methodology to assess the effects of layoff announcements on shareholder returns. The Wall Street Journal was used to identify 368 firms that announced layoffs in 1993 or 1994. The results showed that layoff announcements induced a decrease in the shareholder returns of the firms that made the announcements. Farber and Hallock (1999) generally found negative effects on stock prices as a result of announcements of reductions in force for a sample of 1176 large firms over the 1970–1997 period.

Worrell, Davidson, and Sharma (1991) tested the reaction of the securities’ market to announcements of 194 layoffs. They argued that investors reacted negatively to layoff announcements attributable to financial reasons. They found that negative preannouncement reactions occurred when negative hints about firms preceded announcements, and announcements of large or permanent layoffs elicited stronger negative responses than other announcements. Gombola and Tsetsekos (1992) argued that that a permanent plant closing provides evidence about an entire firm’s financial condition — in particular, that out-of-date plants could not be sold and the firms did not have any other alternatives. Unless investors already knew the true value of the plant, a closing announcement should be following by a negative stock price reaction. They found confirmation of this in their data analysis. Caves and Krepps (1993) also examined how the stock market reacted to announcements of corporate downsizing between 1987 and 1991. Using disaggregated manufacturing industry data from 1967 to 1986, they found evidence that shareholders came to react positively to downsizings that involved white-collar layoffs and related reorganizations.

I have identified five theoretical models of downsizing. Each of these models focuses on a potential cause of downsizing and then traces its consequences for the firm’s employment, productivity, and profitability. Although the models are distinct, they are not mutually exclusive; downsizing may and probably does have multiple causes. Still, it is essential to ask which of the candidate explanations are consistent with the data and which are not.

There has long been a presumption that technological progress favors larger firm size — for example, by requiring huge investments for successful entry or by extending the range of output over which economies of scale persist. Technology of that sort certainly characterized the railroads, automobile manufacture, and earlier forms of steel-making. However, technological change can sometimes make it more efficient to operate on a smaller scale. Transporting freight by truck instead of by rail is one well-known example; it materially decreased average firm size in the transportation industry. Mini mills, the success story of the modern U.S. steel industry, are vastly smaller than integrated steel mills. Some people argue for “the end of mass production” and the greater relative importance of speed, flexibility, product variety, and customization in the computer age. This argument may suggest that downsizing should lead to higher productivity and profitability.

The second model of downsizing also attributes the phenomenon to technical change. But here the effect stems not from changes in the cost-minimizing size of a firm, but rather from the pace of technological improvement itself. The essential idea is that any product or process innovation requires alterations in the nature of the tasks that workers perform. A speedup in the rate of innovation therefore implies that such changes come faster and are more dramatic. And that, in turn, almost certainly requires more extensive reallocations of labor both within and among firms.

One important feature of this phenomenon is the unevenness with which the costs and benefits of such labor market churning are spread across the workforce. Employees who are better educated and/or trained can adapt to new technology and changing circumstances more easily. So they may well be net beneficiaries of innovation. But less skilled workers are presumably less adaptable, and hence are likely to suffer both unemployment and wage declines when they get “downsized.”

The hypothesized role of innovation as the driver of downsizing may seem at first to rest on a fortuitous relationship: Technical change just happens to play a key role. But it may be otherwise. In particular, the market mechanism creates remorseless pressures for innovation, and these pressures are what most clearly distinguish the capitalist economy from all alternatives. One major source of this pressure for continued and increasing innovative effort is the fact that the adoption of new technology, especially in the forms of new products and new industrial processes, has emerged as a prime competitive weapon for firms in the major oligopolistic sectors. The result is an innovation arms race that can literally be a matter of life or death for the participants.

In such a game, no player dares to fall behind, and many may well hope to pull ahead of their rivals. This sort of rivalry is clearly a recipe for increasing investment in R&D and innovative activities more generally. Moreover, faster innovation increases the frequency with which plant and equipment needs to be replaced. By accelerating the replacement of capital, it presumably also adds to the amount of labor-market churning. More often than not, such labor churning requires either retraining existing workers or replacing them with others who are better able to use the new technologies. Such changes therefore disadvantage those whom it is particularly difficult or costly to retrain (e.g., the poorly educated) or who offer bleak prospects for recoupment of the firm’s investments in retraining (e.g., older workers). In this way, innovation may leave a permanent — or at least a very long lasting — imprint on relative wages and the distribution of income, depressing the wages of unskilled and less-educated workers relative to those with more skill and education. On average, however, in this scenario, downsizing should lead to greater efficiency and therefore higher productivity, and to cost-cutting and therefore greater profitability.

A third model attributes downsizing to intensification of foreign competition — whether actual or threatened. It comes in two versions. In the first, increased competition from abroad, or perhaps simply greater cross-border economic activity, changes relative demands and supplies in the U.S. market — which in turn requires some firms and industries to contract while others expand. In fact, the availability of cheaper foreign products can be viewed as analogous to technological progress: Both factors increase the value of the outputs that the U.S. economy can produce from a given set of inputs, and both are likely to require significant industrial change. Furthermore, increased globalization has a clear technological basis: Reduced transportation costs, faster telecommunications, and the like are among the primary drivers of increased trade.

The argument asserts that the U.S. and other industrial economies have grown increasingly vulnerable to import competition as trade barriers have fallen and as technology transfer has progressed. This foreign competition, moreover, has forced American firms to reduce what has been called X-inefficiency (see Leibenstein, 1966) — that is, to trim fat — and this slimming down was (and is) often accomplished by cutting the dispensable portions of their labor forces. The argument is that certain, presumably large, firms used to have (or perhaps still have) more labor than they needed to produce the desired level of output — which they subsequently shed (or are shedding) under pressure from foreign competitors. The prototypical case is perhaps the U.S. auto industry in the 1960s and 1970s, which was widely viewed as “fat and lazy” before the onslaught of Japanese competition.

The second version of the foreign competition argument emphasizes the pressure that low-wage labor abroad puts on U.S. labor markets — especially markets for unskilled labor. The idea that workers in poor countries (“the South”) pose a threat to low-skilled workers in rich countries (“the North”) has been widely offered as an explanation for rising wage inequality in the industrial countries. But it may also lead firms to rid themselves of excess domestic labor, that is, to downsize in the United States. In this model, downsizing is alleged to be caused by intensified competition. If so, the phenomenon should be most severe where the intensification of competition is greatest. Journalistic accounts seem to support this idea, but it is not easy to measure the intensity of competition. Nor is foreign competition the only cause. Falling profit margins are one indication that a particular industry is facing greater competition, but profits are influenced by a myriad of other factors as well. To the extent that increased international competition is the driving force, we should find a positive correlation between downsizing and the share of imports (and maybe even the share of exports) in industry output. There are several pitfalls here, however. For example, the theory of contestable markets emphasizes that potential competition can sometimes be nearly as effective as actual competition in keeping profits down. Hence, profits can be depressed by growing foreign competitiveness even if the foreign market share is low and remains so.

Regardless of the underlying cause, however, it would appear that the “trimming fat” model has a clear empirical implication: Downsizing should raise the average productivity of labor strongly by ridding a firm of redundant labor without reducing its output. This implication appears at least partly testable in a cross-section of firms: Labor productivity should be rising faster in industries which have displaced relatively more workers. The profit implications are less clear, however. Intensified competition should reduce profitability, but shedding excess labor should increase it.

Another possible explanation for downsizing is that firms are shedding labor because they are adopting production technologies that employ relatively less labor and relatively more capital. In other words, they are moving along isoquants toward higher capital–labor ratios. In this case, the total output of a typical firm would not fall, but labor input would fall and capital input would rise. In this scenario, capital–labor substitution underlies downsizing. Why might this be so? Neoclassical theory looks to factor prices to explain optimal factor proportions. A rise in the capital–labor ratio should be prompted by a rise in the ratio of labor compensation to the cost of capital. But the real wage was certainly not growing rapidly during what were apparently the prime downsizing years — say, 1985–1993. Indeed, it was even lagging behind labor productivity. However, the cost of capital fell substantially after the 1980s. The stock market was much higher in 1997 and real interest rates lower than they were then in 1958. So the ratio of labor compensation to the interest rate may well have risen even though wages were barely rising.

Another possibility harkens back to the skill-biased technical progress hypothesis. Most attention has been given recently to the notion that technical change over the last 30 years or so has shifted optimal input proportions away from unskilled labor and toward skilled labor. But suppose capital is a complement to skilled labor (computers require literate and numerate workers), but a substitute for unskilled labor (machines replace brawn). In that case, skill-biased technical progress would also promote capital deepening.

What are the implications in terms of productivity and profitability? Capital–labor substitution would certainly increase labor productivity, but its effect on total factor productivity is indeterminate. Moreover, it is likely in this scenario that downsizing squeezes wages but boosts profits.

A quite different model of downsizing hypothesizes a sea change in the relationship between labor and capital in America. This story shares common elements with the parts of Model 3 that focus on trimming fat. However, it emphasizes the “fat” embodied in high wages — rents captured by labor — rather than in redundant labor. The model comes in two variants.

According to the first variant, owners of capital have become less generous toward and/or less solicitous of labor. Whereas previously, at least, large corporations entered into a kind of “social contract” with their workers — one that involved rent sharing and considerable job security — capital has unilaterally broken that contract and demanded more of the rents for itself. This argument is similar to Lazonick’s portrayal of the radical shift from the OEBM to the NEBM. Labor is thus faced with a choice between lower wages and fewer jobs, the latter being used as a threat to achieve the former. The second, and related, variant of the hypothesis envisions a change in the nature of shareholding away from more patient, relationship-oriented stockholders (e.g., insiders) and toward more impatient, return-oriented stockholders (e.g., fund managers who must show quarterly results). This second variant can possibly explain the first: More activist shareholders may have demanded that management focus on “creating shareholder value” to the detriment of labor and other stakeholders.

If, indeed, the social contract has been rewritten in this way, we can think of several possible causes. One is the intensification of competition, whether domestic or foreign. A second possibility is that the nature of shareholding has shifted toward large (especially institutional) shareholders who give less weight to stakeholders — such as the firm’s workers — and are more focused on the bottom line. A third is the growing financialization of the U.S. economy, as emphasized by Milberg (2008). A fourth is the attitudinal change associated with the country’s political shift to the right — which may, in turn, be ascribable in part to the success of economists’ teachings — may have played a role. The neoclassical message has gotten through. Economic life is now imitating economic theory as never before. One consequence has been the elevation of shareholder value to primacy among possible goals of the firm, to the exclusion of, for example, the interests of stakeholders. Thus, for example, labor is increasingly viewed as “just another commodity” whose price and conditions of employment are determined by supply–demand conditions and nothing else.

Regardless of the cause, how would we know whether the hypothesis underlying Model 5 is valid? One source of potential evidence begins with several studies published in the late 1980s that documented sizable and persistent interindustry wage differentials. These studies found that some industries tend to pay all their workers, not just the occupational groups in short supply, more than other industries do (see, for example, Dickens and Katz, 1987; Krueger and Summers, 1987, 1988). While several hypotheses were advanced to explain this phenomenon, one of the more convincing at the time (and since) was rent sharing. Suppose managers were inclined to share rents with other stakeholders — in particular, with their workers. And suppose further that only certain industries had large rents to distribute, perhaps because only they enjoyed market power. Then employees fortunate enough to work in these industries would enjoy higher wages across the board.

The question is: Have such rents been squeezed or eliminated? The answer appears to be that the interindustry wage differentials observed in the 1980s have persisted into the 1990s — but they appear to have shrunk a bit. For example, Krueger (1998) found from Current Population Survey (CPS) wage data that, after controlling for differences in the educational attainment and experience of their workforces, the interindustry wage distribution became less dispersed over the decade 1983–1993. This evidence is vaguely consistent with the hypothesis that the social contract has been amended in ways that reduce labor’s rents.

Another source of evidence is aggregate data on factor shares. If capital becomes more aggressive — and is successful at it — factor shares should shift toward profits and away from labor compensation. Macro time series on factor shares appear to contain some crude evidence in support of this hypothesis: The share of corporate profits in national income has risen sharply in recent years — from 9.1 percent in 1992 to 11.0 percent in 2000 — while the share of employee compensation has declined almost as much (from 73 percent to 71.6 percent over the same eight-year period).4

Yet another implication of the downsizing scenario based on a change in the social contract is that the level of stock prices should display a permanent increase, and therefore the stock market should enjoy a transition period — perhaps lasting for several years — during which price appreciation is extraordinarily high. That is just what seems to have happened, of course: Stock prices soared from 1995 to a peak in 2000. But (permanently) higher profitability may not have been the only reason, nor even the main reason. Many observers of the stock market, for example, believe that investors are now willing to accept a lower risk premium for holding equity than they previously demanded (see, for example, Cochran, 1999). Hence equilibrium price—earnings ratios may have been permanently elevated. Others insisted that stocks were seriously overvalued in 2000 or so, and were bound to fall (see, for example, Shiller, 2000).

Downsizing based on a breakdown of the social contract clearly carries rather doleful implications for the labor market: Real wages should fall and job insecurity should rise. But the fall in employment should be a transitory phenomenon. It is a way to discipline the workforce. Once workers have been properly disciplined, the economy will have adjusted to the new “rules of the game,” with rents squeezed out of real wages. Then labor should be (permanently) cheaper, and the optimal capital–labor ratio should fall. With regard to productivity, in the standard neoclassical view, if “downsizing” is about the redistribution of rents, its implications for productivity should be nil. It is just that capital should capture more of the rent, and labor less.

In sum, I have discussed five different models of why downsizing may have occurred. Some are “soft” and almost sociological — like the breakdown in the social contract. Others, like capital–labor substitution, are strictly neoclassical. These disparate models have partially overlapping, partially differing implications for a number of observable variables. Some of their implications are testable with existing data, and I will perform some of the relevant tests in the section “Regression Analysis” below.

To determine whether downsizing has occurred in manufacturing. I use data from the U.S. Census of Manufacturing on establishments over the period 1967–1997. The Census of Manufacturing data begin in 1967 and are complete through 1992. Some additional data are available for 1997.5 This source includes data on single establishment and multi-establishment firms. Establishments are classified into industries by their main product.

According to these data, the average establishment size in total manufacturing fell rather sharply over time, from 60.5 employees in 1967 to 45.7 employees in 1992, followed by a slight increase to 46.5 employees in the boom year 1997 (see Table 18.1). The change was fairly continuous over time, though it accelerated a bit in the period between 1987 and 1992. In particular, while over the entire 1967–1992 period, average establishment size fell at an average annual rate of 1.12 percent, between 1987 and 1992 it declined at an annual rate of 1.54 percent.

Table 18.1 also shows results by two-digit SIC. Of the 20 industries, 17 experienced reductions in average establishment size from 1967 to 1992; the other three experienced increases. Of the 16 industries with data available through 1997, 13 show a decline in average establishment size and 3 show an increase. Within the group showing declines, the most notable are electronics and other electrical equipment, primary metals, and leather and leather products, whose average establishment size fell by about half over the period. On the other hand, food and tobacco products both experienced substantial increases in their average establishment sizes. It is also of interest that durable good industries experienced greater declines in their average establishment size — 26 percent between 1967 and 1992 —

Table 18.1 Average number of employees per establishment and co-worker means for two-digit SIC manufacturing industries, 1967–1997

Source: Author’s computations from the Census of Manufacturing, 1967–1997

than did non-durables (16 percent). Finally, the rate of decline of average establishment size accelerated (or the rate of increase declined) in the 1987–1992 period compared to 1967–1987 in 14 of the 20 industries. This is particularly true of durables.

I also calculate the co-worker mean, defined as the weighted average of average establishment size by size class with the percentage of total employment in the size class used as the weight.6 Let:

| Njt | = | number of establishments in industry j at time t. |

| Njkt | = | number of establishments in size class k in industry j at time t. |

| Ejt | = | number of employees in industry j at time t. |

| Ejkt | = | average number of employees in size class k in industry j at time t.7 |

| pjkt = Ejkt/Ejt | = | share of total manufacturing employment in size class k in industry j at time t. |

| ejt = Ejt/Njt | = | average number of employees per establishment in industry j at time t. |

Then the co-worker mean cjt for industry j at time t is given by:

|

(1) |

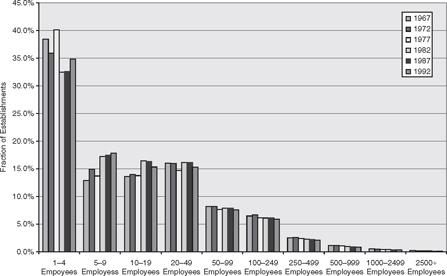

The reason for using the co-worker mean is that the size distribution of establishments (and firms) is highly skewed (see Figures 18.1 and 18.2). In other words, most businesses are small but most employees work in large businesses. The average establishment (or firm) size tells us about the average business but not about the average worker. The co-worker mean is a closer reflection of the experience of the average employee in an industry in terms of the size of business he or she is working in.

It is first of note that the co-worker mean is, as expected, much larger than the average (see Table 18.1). In 1967 the co-worker mean for total manufacturing is 1,424, compared to an average establishment size of 60.5. This means that the typical manufacturing worker in 1967 was employed in an establishment of about 1,500 workers. However, like the average establishment size, the co-worker mean also shows a significant downward trend between 1967 and 1992 of 37 percent, compared to a 25 percent decline for average establishment size over the same years.8 The co-worker mean, like average establishment size, fell in every period except 1982–1987, when it essentially remained unchanged.

Of the 20 industries, all but one experienced a reduction in its co-worker mean between 1967 and 1992. The most notable declines occurred in rubber and plastic products (65 percent), lumber and wood products (56 percent), primary metals (50 percent), and fabricated metal products (49 percent). Leather and leather products underwent a modest increase in its co-worker mean (7 percent).

Table 18.2 provides a summary of the number of industries downsizing and upsizing by census period. The results show a clear pattern: Average establishment

Figure 18.1 Size distribution of establishments by number of employees, 1967–1992 (Census of Manufacturing data).

Figure 18.2 Size distribution of employment by size of establishment in number of employees, 1967–1992 (Census of Manufacturing data).

| Change in average size: | |||

| Period | Total manufacturing | Number of industries downsizing | Number of industries upsizing |

| A. Census of Manufacturing mean establishment size | |||

| 1967–1972 | −4.7% | 11 | 9 |

| 1972–1977 | −8.5% | 18 | 2 |

| 1977–1982 | −3.1% | 14 | 6 |

| 1982–1987 | −3.5% | 11 | 9 |

| 1987–1992 | −7.4% | 14 | 6 |

| 1992–1997 | 1.7% | 5 | 11 |

| TOTAL | −23.2% | 73 | 43 |

| B. Census of Manufacturing establishments: co-worker meana | |||

| 1967–1972 | −17.1% | 13 | 7 |

| 1972–1977 | −3.0% | 16 | 4 |

| 1977–1982 | −8.9% | 19 | 1 |

| 1982–1987 | 0.4% | 15 | 5 |

| 1987–1992 | −14.0% | 15 | 5 |

| Totalb | −36.8% | 78 | 22 |

Source: Author’s computations from the Census of Manufacturing, 1967–1997

Census of Manufacturing data on average-establishment size are missing for five industries in 1997.

Industries in which average size changes by less than 0.1 percent are excluded from the tabulation.

a The co-worker mean is the employment-weighted average establishment size.

b 1967–1992

size in total manufacturing fell steadily from 1967 until the 1992–1997 boom. However, even though average establishment size in all manufacturing declined in every five-year period (until 1992–1997), there were always some “upsizing” industries. Of the 116 observations in total (five census periods with 20 industries and the last census period with 16), downsizing occurred in 73 cases while upsizing occurred in the other 43. So, while downsizing was the most common occurrence, there were plenty of exceptions.

There are also interesting differences by period. Manufacturing industries were less likely to downsize during 1967–1972 and 1982–1987, when the overall decline in manufacturing employment was low, than during 1972–1977 and 1987–1992, when manufacturing employment fell rapidly. In this respect, the 1977–1982 period is a bit of an anomaly, since it ended in a deep recession but the tendency to downsize was weak. Perhaps the cheap dollar of the 1977–1980 period helped manufacturing.

As shown in Panel B of Table 18.2, the downsizing pattern was much stronger for individual industries on the basis of the co-worker mean than the simple mean. Of the 100 observations in total (five census periods with 20 industries), downsizing occurred in 78 percent of the cases (compared to 63 percent of the cases on the basis of the simple mean).

Figures 18.1 and 18.2 show dramatic changes in the overall size distribution of manufacturing establishments based on Census of Manufacturing data over the period 1967 to 1992. The percentage of establishments in all size classes above 19 employees declined over time, and particularly so for establishments of 1,000 employees or more, while the proportion in size classes 5–9 and 10–19 increased. However, interestingly, the percentage of establishments in the size class with less than five employees also fell.

Even more dramatic is the change in the size distribution of employment. The share of total employment in establishments of 2,500 employees or more plummeted almost in half, from 19.6 percent in 1967 to 10.6 percent in 1992. The share of total employment in size class 1,000–2,499 also fell sharply, from 13.2 to 10.6 percent. The proportion of employment in size class 500–999 also declined somewhat. In contrast, the share of total employment in all the smaller size classes rose.

I begin with some descriptive statistics. Figure 18.3 displays the change in average establishment size, and the average rates of TFP and labor productivity growth for total manufacturing by census period. There are no clear connections between productivity and establishment size, at least at the level of total manufacturing. Downsizing occurred during the 1977–1982 period, when TFP (and labor productivity) growth was very low, but also continued during the 1982–1987 period, when productivity grew very rapidly. Productivity growth was also quite high in the 1992–1997 period, when average establishment size gained.

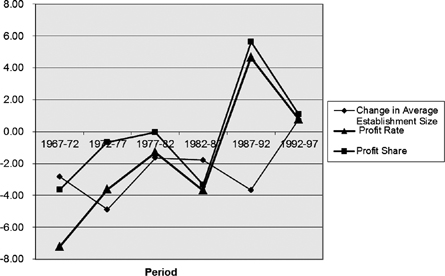

I next show the change in average establishment size and the change in both the average rate of profit and the average profit share for total manufacturing from the preceding census period (see Figure 18.4). There appears to be a somewhat direct relation between the three sets of statistics, at least at the level of total manufacturing. Changes in both the profit rate and the profit share were highest during 1987–1992, when establishments experienced pronounced downsizing, and lowest during the 1967–1972, a period of modest downsizing.

Figure 18.5 shows trends in the average market value of firms in total manufacturing. The data are from the University of Chicago’s CRSP Market Capitalization database, which includes a sample of firms in almost all two-digit industries. Average market value is computed as the ratio of the total market capitalization in a two-digit manufacturing industry divided by the number of firms in that industry. The average market value is deflated by the CPI-U. The index is somewhat imperfect, since it does not correct for mergers, acquisitions, or divestitures.

Stock values fluctuate much more widely than do the other industry level variables. During the first downsizing period, 1967–1972, it rose by only 14 percent and during the next downsizing period, 1972–1977, it fell precipitously, by

Figure 18.3 Changes in average establishment size and the annual percentage growth in TFP and labor productivity, total manufacturing, 1967–1997.

Figure 18.4 Changes in average establishment size and percentage change in profitability, total manufacturing, 1967–1997.

Figure 18.5 Change in average establishment size and the percentage change in average stock market valuation, total manufacturing, 1967–1997.

43 percent (this was true for the S&P 500 index as well). Between 1977 and 1982, another downsizing period, average market value in manufacturing inched up by 3 percent. However, during the next two periods, 1982–1987 and 1987–1992, during which average firm size fell, average market values rose by 37 and 32 percent, respectively. In the 1992–1997 period, when average establishment size increased very modestly, the average stock valuation in manufacturing boomed (as did the S&P 500 index), more than doubling in value. If anything, it appears that stock values rise faster during upsizing periods than during downsizing.

The last variable of interest is the change in average employee pay. This is defined in two ways: first, as average wages and salaries per full-time equivalent employee (FTEE); and, second, as the average employee compensation, including wages and salaries and employee benefits per FTEE. Both wages and salaries and employee compensation are deflated by the CPI-U to obtain employee pay in constant dollars.

Figure 18.6 shows the percentage change in the latter for the Census of Manufacturing periods (changes in wages and employee compensation are highly correlated). Here, a somewhat closer correspondence between patterns of upsizing and downsizing and the growth in pay is seen than between changes in average size and the preceding set of variables. During the first downsizing period, 1967–1972, average compensation grew at a brisk pace (10.5 percent) but in the next downsizing period, 1972–1977, the growth in average compensation fell by 6.0 percent. Over the next three periods, all characterized by downsizing, gains in average employee compensation actually declined by −2.6 percent, then rebounded to 6.4 percent, but subsequently collapsed to 1.2 percent. During the

Figure 18.6 Changes in average establishment size and percentage change in employee compensation, 1967–1997.

1992–1997 period, when average establishment size rose slightly, the growth in average compensation once again recovered — to 2.2 percent.

I next turn to regression analysis to analyze the effects of downsizing on these various variables. I use a panel data set, consisting of 20 industry observations in each of the six five-year time periods. I estimate a fixed-effects model, in which the dependent variable is a function of average establishment size in an industry plus an industry-specific effect that is constant over time. The regression is based on the first difference of this equation, so that the industry-specific constant washes out.

In the regressions, I posit that the level of a dependent variable (such as the profit rate) is a function of the logarithm of establishment size and other pertinent variables, as well as a set of (19) industry dummy variables. The basic model is given, in the case of the profit rate as dependent variable, by:

|

(2) |

where ejt is the average number of employees per establishment in industry j at time t, EXPGOjt is the ratio of industry j’s exports to gross output at time t, IMPGOjt is the ratio of industry j’s imports to gross output at time t, INDDUMj is an industry dummy variable for industry j (19 dummy variables in all), and ujt is a stochastic error term assumed to be independently and identically distributed (i.i.d). I use the logarithmic form for ejt since it is more likely for the profit rate (and the other dependent variables) to be a convex function of establishment size, rather than to be proportionately related to establishment size. The industry dummy variable is included to control for industry effects due to industry differences in technology, scale, and capital requirements.

By taking first differences of equation (2), I obtain:

|

(3) |

where ΔXjt ≡ Xjt − Xj,t−1 for any variable X, gjte is the percentage change in ejt over the period, and vjt ≡ ujt − uj,t−1. The error term vjT is by construction auto-correlated. I use GMM (the generalized method of moments) with autocorrelation correction for the estimation.

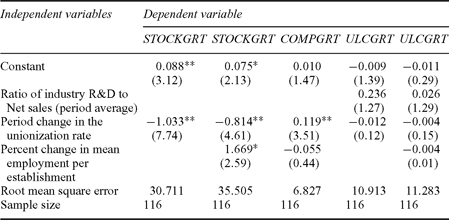

Results are shown in the first two columns of Table 18.3 for the first dependent variable, TFP growth (see the Data Appendix for the definition of TFP growth).9 The first variable of interest is the constant term, which is interpreted as the pure rate of technological progress. Its value ranges from 0.6 percent to 1.6 percent per year. These values are typical for most estimations of TFP growth in manufacturing.

The next variable of interest is industry R&D expenditures as a percent of net sales. A large literature has now almost universally established a positive and significant effect of R&D expenditures on productivity growth (see, for example, Griliches, 1979, for a review of the literature). Following Griliches (1992), the coefficient of this variable can be interpreted as the rate of return of R&D (under the assumption that the average rate of return to R&D is equalized across sectors). In Table 18.3, the coefficient of the ratio of R&D expenditures to net sales is significant at the 1 percent level in the two specifications. The estimated rate of return to R&D ranges from 13 to 14 percent. These estimates are about average for previous work on the subject (see, for example, Mohnen, 1992, for a review).

I next consider the effects of international trade on TFP growth. The change in import intensity has a negative coefficient but it is not significant. In contrast, the change in export intensity has a positive coefficient, which is significant at the 1 percent level. The rationale is that export competition puts pressure on a firm to increase efficiency and reduce cost to compete in international markets and this shows up as a positive effect on TFP.

The last variable of interest is the percentage change in mean establishment size. Its coefficient is negative but not significant. The results do not support the argument in the third section that downsizing may be a mechanism that increases establishment productivity as unnecessary labor is shed.10

Note: The sample consists of panel data, with observations on each of the 20 manufacturing industries. The census periods are: 1967–1972, 1972–1977, 1977–1982, 1982–1987, 1987–1992, and 1992–1997 (16 industries). The coefficients are estimated using GMM. t-statistics are in parentheses. See the Data Appendix for sources and methods.

Key:

TFPGRT: average annual rate of total factor productivity growth, based on full-time equivalent employees (FTEE) and net capital stock.

The GMM instruments are: (1) unionization rate; and (2) the profit rate.

ΔPROFRAT: Change in the profit rate over the period.

ΔPROFSHR: Change in the profit share over the period.

The GMM instruments for both variables are: (1) the ratio of R&D to sales; and (2) TFP growth.

Significance levels: # − 10%, * − 5%, ** − 1%.

I next investigate the relation of downsizing to both profitability and the market value of companies. I use the same sample as in the analysis of productivity trends. There is less of a theoretical basis for the choice of possible determinants of firm profitability and stock valuation than there is of productivity growth. However, it might be expected that profitability within an industry would depend on, among other things, the unionization rate, the degree of import penetration, export competition, and the change in establishment size.

The first dependent variable is the period change in the average industry profit rate (see Table 18.3). In the first specification, I include only the unionization rate for the industry and the change in both import and export intensity as independent variables. The coefficient of the unionization rate is negative, as expected, and significant at the 1 percent level. This result is consistent with the findings of Freeman and Medoff (1986). The coefficient of the change in import intensity is, also as expected, negative though not significant. On the other hand, the coefficient of the change in export intensity is positive and significant at the 5 percent level. This result is in accord with the finding reported above that a rise in export intensity leads to increased TFP. The argument is likely the same — namely, that export competition leads to increased efficiency and reduced cost.

In the next specification, I add the percent change in mean establishment size as an independent variable. Its coefficient is significant at the 5 percent level but unexpectedly positive. A possible explanation is that downsizing causes firms to reorganize production, as well as to get rid of workers with potentially needed skills. The adjustment costs associated with reorganization may lead to higher costs and therefore lower profits.

The next dependent variable is the change in the profit share within an industry between the previous and current period. The coefficients, shown in the last two columns of Table 18.3, have the same sign as those for the change in the profit rate, but are generally less robust. In fact, the coefficient of the change in the unionization rate is no longer significant, while that of the change in export intensity is significant at the 10 percent level in the first of the two specifications but not significant in the second. On the other hand, the coefficient of the change in import intensity is negative and significant at the 10 percent level. This result supports the argument that import competition cuts into the market of the domestic producer and lowers profitability. The coefficient of the percentage change in average establishment size is positive, as before, but is not statistically significant.

The third dependent variable in this group is the percentage change in the average market value of firms within an industry, deflated by the CPI-U (see the first two columns of Table 18.4). In the case of stock market valuation, there is little theory to guide us with regard to other independent variables, and I use only the change in the unionization rate. Its coefficient is negative and significant at the 1 percent level. This result strongly suggests the stock market puts a negative valuation on the presence of unions, presumably because of their negative

Table 18.4 Regressions of stock prices, employee compensation, and unit labor costs on downsizing variables

Note: The sample consists of panel data, with observations on each of the 20 manufacturing industries. The census periods are: 1967–1972, 1972–1977, 1977–1982, 1982–1987, 1987–1992, and 1992–1997 (16 industries). The coefficients are estimated using GMM. t-statistics are in parentheses. See the Data Appendix for sources and methods.

Key:

STOCKGRT: Percentage change in the average market valuation of firms over the period.

COMPGRT: Percentage change in average employee compensation over the period.

The GMM instruments for both variables are: (1) the ratio of R&D to sales; and (2) TFP growth.

ULCGRT: Percentage change in unit labor costs over the period.

The GMM instrument is: percentage change in the average market value of firms.

Significance levels: # − 10%, * − 5%, ** − 1%.

impact on the profit rate, and rewards industries in which the union presence is reduced.

The major finding is that the coefficient of the percentage change in mean employment per establishment is positive and significant at the 5 percent level. In other words, contrary to popular belief and the models developed in the third section, downsizing is associated with a drop in stock values, not a rise.

This regression finding on the relation between changes in the market valuation of firms and downsizing does not establish the direction of causation. It is possible that firms downsize when their stock values fall, thus creating a positive correlation between changes in average market value and changes in establishment size. It is also possible that when a firm gets into trouble, both its stock value falls and it downsizes in response to falling profits. It may also be true that the market does not reward downsizing — that is, when layoffs occur, investors take it as a sign of trouble and try to sell off the company’s stock.11

The next dependent variable of interest is the change in employee remuneration. This is measured by the percent change in employee compensation, including wages, salaries, and fringe benefits, per FTEE.12 There are a limited number of independent variables for the analysis here as well. Ideally, one would like to control for changes in the average human capital or skill level of employees within an industry. However, these data are not available. I do, however, have information on the degree of unionization within an industry. This will allow us to control for the well-documented wage differential between union and non-union workers (see, for example, Lewis, 1986).

The results are shown in column 3 of Table 18.4. The main finding is that, not surprisingly, the change in the unionization rate has a positive coefficient, significant at the 1 percent level. On the other hand, percentage change in the average number of employees per establishment has a negative but statistically insignificant coefficient.

The last dependent variable of interest is the annual change in unit labor cost. Unit labor cost is defined as employee compensation (in 1992 dollars) to output (also in 1992 dollars). It is thus the ratio of real compensation per worker to labor productivity. Its change over time thus reflects changes in employee compensation and changes in labor productivity. The results for this variable are shown in the last two columns of Table 18.4. The coefficients of both R&D intensity and the change in the unionization rate have the expected sign, but neither coefficient is statistically significant. The coefficient of the percentage change in the average number of employees per establishment is negative but not significant.

Using U.S. Census of Manufacturing data covering the period from 1967 to 1997, I find strong evidence that average establishment size declined in manufacturing. Overall, mean establishment size fell from 60.5 to 46.5 over this period.

With regard to the consequences of downsizing, I essentially find no support for any of the five models of downsizing outlined above. Indeed, of the six dependent variables considered in this chapter, the change in average establishment size has significant coefficients for only two — the period change in the profit rate and the percentage change in average stock prices. However, in these two cases, the results are exactly the opposite of what is predicted by the models. Downsizing leads to both lower profitability and lowered stock prices. The possible reason, suggested above, is that downsizing causes firms to reorganize production, as well as to get rid of workers with potentially needed skills. The adjustment costs associated with reorganization may lead to higher costs and therefore lower profits. Lowered profits, in turn, may lead to a fall in stock prices.

This result on the relationship between downsizing and stock prices is consistent with those of Worrell, Davidson, and Sharma (1991), Gombola and Tsetsekos (1992), Abraham (1999), and Farber and Hallock (1999). This regression finding does not establish the direction of causation — whether downsizing leads to falling stock values, or falling stock values induce firms to downsize. Moreover, as one referee pointed out, it is possible that the negative effect on stock prices results from the fact that I define downsizing as a reduction in average establishment size instead of the strategic announcements of layoffs. However, evidence from Chapter 2 of Baumol, Blinder, and Wolff (2003), which looked at the relation of layoff announcements in the press to changes in stock market prices found no discernible association between the two.

The results, as noted above, do not indicate that changes in average establishment size have any direct association with industry productivity growth. This result is broadly consistent with the findings of Baily, Bartelsman, and Haltiwanger (1996) and Collins and Harris (1999) that downsizing was generally associated with a lowering of productivity growth. Moreover, downsizing does not appear to lead to reductions in unit labor costs. This result contrasts with the findings reported by Cappelli (2003) and Espahbodi, John, and Vasudevan (2000).

In contrast, the change in the unionization rate — more specifically, de-unionization — exercised a substantial effect. In fact, the results of this chapter seem to be more of a story about de-unionization than about downsizing. I find that the change in the unionization rate is negatively and highly significantly related to the change in the industry profit rate, indicating that the de-unionization in an industry increases its profitability. The change in the unionization rate is also found to be negatively and highly significantly related to market value gains. The results indicate that the stock market puts a negative valuation on the presence of unions, presumably because of their depressing effect on profits. Not surprisingly, the change in the unionization rate, is positively associated with the growth in employee compensation and the effect is statistically significant.

In brief, the econometric evidence indicates that where downsizing has occurred in the manufacturing sector it has, first of all, not contributed to productivity, contrary to what is frequently conjectured. Second, it has actually reduced profits. Third, downsizing by a firm has been associated with a decline in the price of its stocks, perhaps because it lowers profitability. In contrast, de-unionization is strongly associated with a rise in profitability, an increase in stock prices, and a drop in worker compensation.

Further analysis suggests that the main effect of downsizing may be to deplete unions. A regression of the change in unionization on the percent change in mean establishment size (run using GMM, with TFP growth as the instrument) yields a positive coefficient, significant at the 5 percent level. The estimated coefficient is 0.25, suggesting that a 1 percent decline in average establishment size reduces the unionization rate by 0.25 percentage points.

1 The term “establishment” refers to an individual plant or office in a single geographical location. In contrast, an “enterprise” is one or more establishments owned by the same company. The term “firm” is synonymous with “enterprise.”

2 Somewhat ironically, in our analysis in this book we found very little correlation between announcements of downsizing and actual reduction in establishment or firm size. Also See Baumol, Blinder, and Wolff (2003) for an extensive bibliography on the subject of downsizing.

3 On the other hand, announcements of permanent staff reductions were associated with significant increases in the variation of abnormal total shareholder return around the announcement date.

4 The data are from the National Income and Product Accounts. See the Appendix for details.

5 The 1997 Census of Manufacturing shifted from the old SIC industry classification to the new NAICS (North American Industrial Classification System). As a result, size distributions of establishments in 1997 are not directly comparable to those of earlier years. However, some bridge tables were provided for 1997 by the U.S. Census Bureau based on the old SIC scheme.

6 Technically speaking, the co-worker mean as introduced by Davis, Haltiwanger, and Schuh (1996) was based on microdata (plant level data), while here I use aggregate size class data.

7 This is estimated as the midpoint of the size class, 1–4, 5–9, …, 2,500+ (see Figure 18.1 for the size classes used), with a Pareto estimate for the mean of the top size class.

8 The co-worker mean could not be computed for 1997.

9 Technically, the levels equation includes the logarithm of TFP as the dependent variable and R&D stock as an independent variable, so that first differencing yields TFP growth as the dependent variable and the ratio of R&D expenditures to sales as an independent variable in the first difference equation. See, for example, Griliches (1992) for a derivation.

10 I also use the annual rate of labor productivity growth as the dependent variable (and include the rate of growth of total capital per worker as an independent variable). The results are very similar to those for TFP growth (these are not shown in a table).

11 I did test for reverse causation by regressing the percent change in average establishment size on TFP growth, R&D intensity, the unionization rate, the change in export and import intensity, the growth in total industry employment, the lagged profit rate, and the percent change in the average market value of firms within an industry lagged one period. I found that the coefficient of the last of these variables is uniformly negative, though not statistically significant. This result is unexpected, since it suggests that when the stock value of a firm declines, it responds (after a lag) by increasing employment rather than decreasing it.

12 In this case, the dependent variable in the levels equation is the logarithm of average employee compensation. Results are also very similar for wages and salaries (in contrast to total employee compensation) per FTEE and are not shown here.

Abowd, John M., George T. Milkovich, and John M. Harmon (1990) ‘The Effects of Human Resource Management Decisions on Shareholder Value’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 43: 203–236.

Abraham, Steven E. (1999) ‘Layoff and Employment Guarantee Announcements: How Do Shareholders Respond?’, Department of Economics, SUNY-Oswego Working Papers.

Baily, Martin Neil, Eric J. Bartelsman, and John Haltiwanger (1996) ‘Labor Productivity: Structural Change and Cyclical Dynamics’, NBER Working Paper Series, No. 5503, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Baumol, William J., Alan S. Blinder, and Edward N. Wolff (2003) Downsizing in America: Reality, Causes, and Consequences, New York: Russell Sage Press.

Cappelli, Peter (2003) ‘Examining the Incidence of Downsizing and its Effect on Establishment Performance’, in David Neumark (Ed.) On the Job: Is Long-Term Employment a Thing of the Past?, New York: Russell Sage Press.

Caves, Richard E., and Matthew B. Krepps (1993) ‘Fat: The Displacement of Nonproduction Workers from U.S. manufacturing industries’, Brookings Papers: Microeconomics, 2: 227–288.

Cochran, John (1999) “New Facts in Finance,” NBER Working Paper, No. 7169, June.

Collins, Alan, and Richard I.D. Harris (1999) ‘Downsizing and Productivity: The Case of UK Motor Vehicle Manufacturing 1974–;1994’, Managerial-and-Decision-Economics, 20: 281–290.

Davis, Steven J., John C. Haltiwanger, and Scott Schuh (1996) Job Creation and Destruction, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dickens, William T., and Lawrence F. Katz (1987) ‘Interindustry Wage Differences and Industry Characteristics’, in Kevin Lang and Jonathan Leonard (Eds.) Unemployment and the Structure of Labor Markets, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Duménil, Gérard, and Dominique Lévy (2011) The Crisis of Neoliberalism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Espahbodi, Reza, Teresa A. John, and Gopala Vasudevan (2000) ‘The Effects of Downsizing on Operating Performance’, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 15: 107–126.

Farber, Henry S., and Kevin F. Hallock (1999) ‘Have Employment Reductions Become Good News for Shareholders? The Effect of Job Loss Announcements on Stock Prices, 1970–;97’, NBER Working Paper, No. 7295, August, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Freeman, Richard B., and James L. Medoff (1986) What Do Unions Do?, New York: Basic Books.

Gombola, Michael J., and George P. Tsetsekos (1992) ‘Plant Closings for Financially Weak and Financially Strong Firms’, Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 31: 69–83.

Gordon, David M. (1996) Fat and Mean: The Corporate Squeeze of Working Americans and the Myth of Managerial “Downsizing”, New York: Free Press.

Griliches, Zvi (1979) ‘Issues in Assessing the Contribution of Research and Development to Productivity Growth’, Bell Journal of Economics, 10: 92–116.

Griliches, Zvi (1992) ‘The Search for R&D Spillovers’, Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 94: 29–47.

Hirsch, Barry T., and David A. Macpherson (1993) ‘Union Membership and Coverage Files from the Current Population Surveys: Note’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 46: 574–578.

Idson, Todd (1999) ‘Skill-Biased Technical Change and the Employer Size-Wage Effects’, Columbia University, mimeo, New York.

Kokkelenberg, Edward C, and Donna R. Sockell (1985) ‘Union Membership in the United States, 1973–;81’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 38: 497–543.

Krueger, Alan B. (1998) ‘Thoughts on Globalization, Unions and Labor Market Rents’, mimeo, Princeton University, April 28.

Krueger, Alan B., and Lawrence H. Summers (1987) ‘Reflections on the Inter-Industry Wage Structure’, in K. Lang and J. Leonard (Eds.), Unemployment and the Structure of Labor Markets, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Krueger, Alan B., and Lawrence H. Summers (1988) ‘Efficiency Wages and the Inter-Industry Wage Structure’, Econometrica, 56: 259–294.

Lazonick, William (2009) Sustainable Prosperity in the New Economy? Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Leibenstein, Harvey (1966) ‘Allocative Efficiency vs. X-Efficiency’, American Economic Review, 56: 392–415.

Lewis, H. Gregg (1986) Union Relative Wage Effects: A Survey, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Masters, Stanley H. (1969) ‘An Interindustry Analysis of Wages and Plant Size’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 51: 341–345.

Mellow, Wesley (1981) ‘Employer Size and Wages’, Bureau of Labor Statistics Working Paper, No. 116, April, Washington, DC.

Milberg, William (2008) ‘Shifting Sources and Uses of Profits: Sustaining US Financialization with Global Value Chains’, Economy and Society, 37: 420–451.

Mohnen, Pierre (1992) The Relationship between R&D and Productivity Growth in Canada and Other Major Industrialized Countries, Ottawa: Canada Communications Group.

Shiller, Robert J. (2000) Irrational Exuberance, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Stockhammer, Engelbert (2004) ‘Financialisation and the Slowdown of Accumulation’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 28: 719–741.

Sturgeon, Timothy, Johannes Van Biesebroeck, and Gary Gereffi (2008) ‘Value Chains, Networks and Clusters: Reframing the Global Automotive Industry’, Journal of Economic Geography, 8: 297–321.

White, Halbert L. (1980) ‘A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity’, Econometrica, 48: 817–838.

Worrell, Dan L., Wallace N. Davidson III, and Varinder M. Sharma (1991) ‘Layoff Announcements and Stockholder Wealth’, Academy of Management Journal, 43: 662–678.

where Ŷj is the annual rate of output growth,  is the annual growth in labor input, and

is the annual growth in labor input, and  is the annual growth in capital input in sector j, and

is the annual growth in capital input in sector j, and  is the average share of employee compensation in GDP over the period in sector j (the Tornqvist–Divisia index). I measure output using GDP in constant dollars, the labor input using FTEEs, and the capital input by the fixed non-residential net capital stock (1992 dollars).

is the average share of employee compensation in GDP over the period in sector j (the Tornqvist–Divisia index). I measure output using GDP in constant dollars, the labor input using FTEEs, and the capital input by the fixed non-residential net capital stock (1992 dollars).

Key:

PBT: Corporate profits before tax.

PI: Proprietors’ income.

PTI: Gross property-type income, defined as the sum of corporate profits, the profit portion of proprietors’ income, rental income of persons, net interest, capital consumption allowances, business transfer payments, and the current surplus of government enterprises less subsidies. Proprietors’ income includes both labor income and a return on capital. The labor portion is estimated by multiplying the number of self-employed workers by the average employee compensation of salaried workers. The profit portion is the residual part of proprietors’ income.

CCCA: Corporate Capital Consumption Allowance.

NCCA: Non-corporate Capital Consumption Allowance.

GDP: Current dollar Gross Domestic Product.

COMP: Compensation of employees, which consists of wage and salary accruals, employer contributions for social insurance, and other labor income.

NNI: Net national income, defined as COMP + PTI − CCCA − NCCA.

NETK: Current-cost net stock of fixed reproducible tangible non-residential private capital.