9

The late pre-Roman Iron Age in western and northern Britain

Beyond the peripheral zone of coin-issuing tribes – the Durotriges, Dobunni, Corieltauvi and Iceni – lay vast expanses of Britain: the south-western peninsula, Wales and the north. The south-west differed from the rest in that it remained in contact by sea both with the southeastern tribes and with Armorica and thus absorbed cultural influences from the two peninsulas. Wales and the north on the other hand were far removed from the rapidly expanding economies of the south-east and were largely isolated from Continental influences until the second half of the first century AD, by which time Roman rule, or the bow-wave effects of the Roman presence, had penetrated all but the extreme north-west. For these reasons there is a considerable degree of cultural unity over large stretches of country and it is sometimes difficult to isolate material of the Late Iron Age from that of earlier periods. Nevertheless the writings of several Roman authors provide a valuable descriptive horizon from which to assess the social and economic changes of the preceding decades.

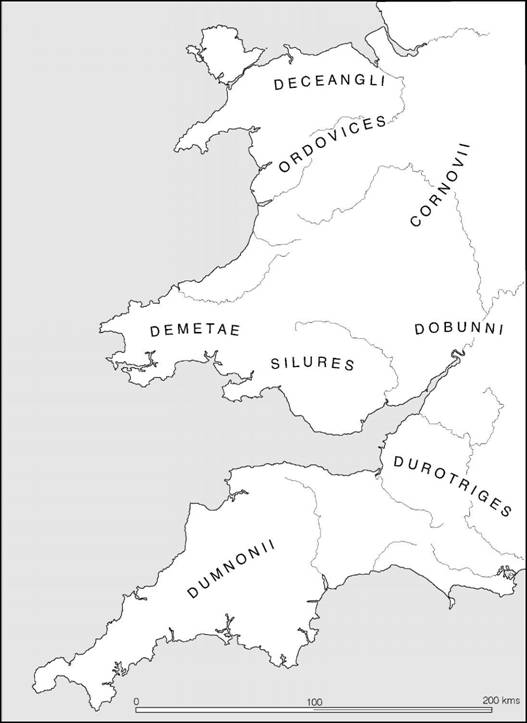

The south-west peninsula: the Dumnonii (Figure 9.1)

The Dumnonii occupied the south-west peninsula probably as far east as the Parrett–Axe line. In this position of relative isolation, cultural contact with the communities of the south-east was limited and it is therefore hardly surprising that the disparate peoples who occupied the broken and varied landscape of the peninsula failed to develop a coinage of their own: exchange remained embedded in traditional social systems. Apart from coin hoards at Mount Batten, Carn Brae, Penzance and Paul, coins are virtually unknown.

The ceramic development of the region can be divided into two distinct traditions, one following the other and in parts replacing it. The earlier is characterized by the South-Western Decorated Wares, which used to be called ‘Glastonbury wares’. These decorated vessels were produced at several centres, including the Lizard peninsula and on the Permian outcrops of the Exe region. As we have seen, the tradition probably originated in the fourth century BC, inspired by Armorican developments, and decorated wares continued to be made well into the first century BC. The classic forms were necked-bowls and jars decorated with elaborated curvilinear motifs executed by shallow tooling, stamping and, less frequently, the roulette wheel.

Figure 9.1 The tribes of western Britain (sources: various).

The second, later, tradition is generally known as Cordoned Ware. The repertoire includes necked-jars, tazza-like bowls and large everted-rimmed jars, all undecorated except for prominent horizontal cordons sometimes used in combination with grooves (Figure A:37). The vessels were well made and turned on a wheel. At several sites, including Castle Dore, Cordoned Ware could be shown to be generally later than South-Western Decorated Wares and there is ample evidence from Cornwall to show that the Cordoned Ware tradition continued into the Roman period.

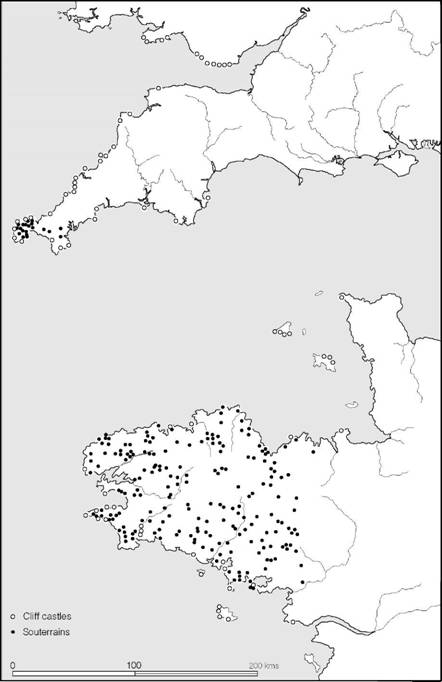

It used to be thought that Cordoned Wares were brought to the south-west by refugees from Armorica fleeing in the wake of the Roman advance of 56 BC, and that fogous and cliff castles, both of which had close parallels to similar structures in Brittany, were introduced at the same time (Hawkes 1966). This view can no longer be sustained, since the Cornish fogous (Christie 1979; Maclean 1992) and cliff castles (Sharpe 1992; Herring 1994) can be shown to date back to the beginning of the Middle Iron Age if not earlier and are part of a shared cultural tradition which linked the two peninsulas for centuries before the Caesarian episode (Figure 9.2). The appearance of Cordoned Ware could be better explained in the general context of continuing social intercourse rather than as the result of a single event.

The dating of the Cornish Cordoned Wares is difficult to establish with precision, but stylistically they have little in common with Armorican ceramics of the Caesarian period. They do, however, share a general resemblance to developments in north-western France and central southern Britain dating to the second half of the first century BC. They are best explained therefore as the result of local trading contacts between these areas in the post-Caesarian period. That the distribution is restricted largely to Cornwall, extending as far east as the port of Mount Batten, suggests that most of Devon was excluded from the system: here the traditional decorated wares probably continued until the Roman Conquest.

Dumnonian settlement of the period c. 100 BC–AD 50 forms part of a continuous pattern well rooted in the preceding centuries and continuing in some areas throughout the Roman period (Johnson and Rose 1982). In Devon the multiple-ditched enclosures of the third or second century remain the dominant form of defended homestead or hamlet into the first century AD, with little apparent change in either size of community or the predominantly pastoral economy. Thus Milber Down Camp, one of the few excavated sites in this category, remained in use well into the first century BC, while later occupation into the Roman period continued outside the main enclosure. Similarly, at Castle Dore first-century AD occupation is attested by Cordoned Ware. Further west, in Cornwall, many of the rounds (i.e. small defended homesteads seldom exceeding 2 ha in extent) which form a dominant element in the Roman settlement pattern originate in the Late Iron Age. At Crane Godrevy, Castle Gotha and Gwithian Cordoned Ware has been found; and at the somewhat larger site of Carloggas, St Mawgan-in- Pydar, occupation began during the late second or early first century BC, while South-Western Decorated Wares were in use and continued into the Roman period. Another large settlement, the bivallate site of Killibury, began equally early but was abandoned before Roman pottery reached the area. The settlement at Trevisker, close to Carloggas, spanned the period from the Middle Bronze Age into Roman times. It is estimated (Thomas 1966b, 88–90) that in Cornwall and south and west Devon between 750 and 1,000 rounds existed, with a density averaging one per 2.6 square kilometres. Clearly they must represent the homesteads or small hamlets of an essentially non-nucleated population.

Comparatively little is known of the occupation of central and eastern Devon in the Late Iron Age but excavation on Dartmoor, at Gold Park, on the eastern edge of the moor, has demonstrated the presence of a small well-established farming community. The discovery raises the possibility that some of the more congenial moorland landscape may have begun to be recolo- nized at this time.

Figure 9.2 Settlement similarities between Cornwall and Brittany (source: Cunliffe 1982a with additions).

Another type of settlement which appears later, representing the same size of social group, is the courtyard house – so-called because each had a central area, thought to have been a courtyard, surrounded by rooms all enclosed within a massive stone wall. It has, however, been suggested that the entire structure, rooms and central area, was roofed in one (Wood 2001). Sometimes courtyard houses were built within rounds (e.g. Goldherring) or were otherwise enclosed, but open villages like Chysauster and Carn Euny are also known. The origin of the courtyard house is still a matter of uncertainty, but the evidence from the long-lived settlement at Carn Euny suggests local evolution, though perhaps not until after the beginning of the Roman occupation.

The best-defined category of hillforts in the south-west are the cliff castles, which densely ring the coasts of Cornwall (Herring 1994) and north Devon. Essentially, a cliff castle is a promontory projecting into the sea, the neck of which is defended by one or more series of banks and ditches. The obvious similarities between the cliff castles of south-west Britain and those of Brittany (Wheeler and Richardson 1957) has frequently been used as an argument in favour of a Venetic invasion of Cornwall, but of the sites excavated, Maen Castle seems to have originated at least as early as the second century BC, while Gurnard’s Head has produced a range of pottery beginning not very much later. At the Rumps occupation began in the second century BC and lasted until the early first century AD. Thus, from the available evidence it would appear that cliff castles formed an essential part of the settlement pattern for at least three centuries and are therefore unlikely to be the result of the arrival of refugees in the mid-first century BC.

The enclosed areas of the cliff castles vary according to the shape and size of the promontory selected, but since in every case the actual length of the defences was kept to a minimum, the amount of labour involved in construction was relatively slight. Massive hillfort-building on the scale practised in the south-east is almost unknown, and even when an inland site was chosen, like Tregear or Chun Castle, size was restricted. At Chun, for example, while the two defensive walls were substantial, the area enclosed was only about 52 m across.

The function of the cliff castles presents a problem. They were often remote and inaccessible and some offered little inhabitable space. It could, of course, be that they served as the residences of the élite but their liminal positions, at the interface of land and sea, might hint at a less secular function. It is not impossible that some served as a focus for ritual activity (Sharpe 1992). At any event the cliff castles and small inland forts were not suited to serve as foci for larger social gatherings as were the hillforts of Wessex.

The port-of-trade established at Mount Batten, Plymouth, in the Late Bronze Age, and serving throughout much of the Iron Age as a link with the Atlantic trading system, remained in use during the Late Iron Age, but the intensity of occupation does not appear to have been great though there is evidence of contact with the Solent harbours at this time. The cemetery on Stamford Hill nearby did, however, produce a group of well-furnished burials dating to the middle decade of the first century AD, suggesting the possibility of an upturn in fortunes at about the time of the Roman Conquest.

The rite of inhumation in small cists, which was practised in the area in the preceding periods (e.g. at Harlyn Bay and Trevone), continued unhindered into the Roman period. It is represented at several sites, including the large cemetery at Stamford Hill, Mount Batten, and the smaller group of burials at Trelan Bahow near St Keverne, where one of the graves was of a rich female who had been provided with a bronze mirror, two bracelets, rings, brooches and a necklace of blue glass beads, all dating to the first century AD. The similarities between this burial and female inhumations in the territory of the Durotriges and Dobunni may suggest an element of unity underlying the burial rites of the south-west. At Bryher, Isles of Scilly, a burial provided with a mirror and a sword was found, implying that the burial tradition may have been more complex than the gender-related items may at first have suggested.

In summary, it may be said that many of the elements which together constitute the culture of the Dumnonii owe much to social intercourse with their Armorican neighbours, but Dumnonian culture developed slowly in parallel with the Continent and was not suddenly altered by incursions of refugees.

The proximity of the two peninsulas facilitated social interaction but it was probably the tin trade, stretching back into the Bronze Age, which acted as the main stimulus for contact. This network of exchange brought the communities of Armorica and the south-west together, while the striking geomorphological similarities of the two territories led to a degree of parallel cultural development. The ceramic sequences, though distinct, shared much in common. At the same time settlement morphology, with its cliff castles, rounds and fogous or souterrains, was remarkably similar on both sides of the Channel. The development of a trading network between Armorica and the Solent harbours in the first half of the first century BC may have temporarily deflected contact, but in the aftermath of the Caesarian campaign traditional relations were re-established. It was probably in this context that the Cornish Cordoned Wares developed and a few Italian amphorae reached sites like Carloggas and the Rumps. The contrast between the culture and economy of the Dumnonii and that of the other tribes of southern Britain is very marked. The Dumnonii were in every way closer to the tribes of Armorica than they were to their neighbours in Britain.

Wales

Any consideration of the cultural groupings and developments in Wales during the first centuries BC and AD is likely to be fraught with difficulty, largely because of the lack of large-scale excavation and the almost total absence of closely datable cultural material. Moreover, the inhospitable nature of much of the countryside has ensured that considerable areas remained uninhabited while in others pastoralism probably played a significant part. Together these factors militate against an adequate description of the material culture on a regional basis.

Knowledge of tribal groupings rests largely upon the writings of the geographer Ptolemy whose lists, taken together with descriptive accounts by Tacitus and other fragments of epi- graphic evidence, show that Wales was divided into a minimum of five tribal areas roughly approximating to broad geographical divisions. In the extreme south-west were the Demetae. Next to them, from the Gower peninsula stretching along the coastal plain to the Wye and extending into the Black Mountains, were the Silures, whom Tacitus describes as ruddy-faced and curly-haired, reminding him of Iberians. In the north-west, centred on the Lleyn peninsula, lay the Gangani, who may have been related to a tribe of the same name living in north-west Ireland, while along the north coast lived the Deceangli. Lastly, between these four tribes were the Ordovices, occupying the mountainous area in the centre of the principality.

The Silures

The exact limits of Silurian territory cannot be precisely drawn but it is clear that the bulk of the tribe occupied the lowland coastal areas of Glamorganshire and Monmouthshire and the valleys of the Black Mountains, with the river Wye forming the approximate boundary with the Dobunni. In all probability, the cluster of small defended settlements centred on the upper reaches of the Usk, in the heart of the Brecon Beacons, can also be regarded as belonging to a geographically isolated community of the Silures.

Material culture and settlement type have many similarities with those of adjacent territories. Some of the hillforts in the eastern part of the territory, such as Sudbrook and Llanmelin in Monmouthshire, are closely similar to Wessex sites; others are best paralleled by the multiple- ditched enclosures of the south-west peninsula; while the cliff castles of the coastal group have much in common with those of Cornwall and Devon. Environment, economy and commercial communications must have encouraged this parallelism. At Llanmelin a 2.2 ha multivallate enclosure with a semi-inturned entrance was shown to have been in use during the local phase of the saucepan pot continuum, roughly second to first centuries BC, and there is some evidence of modification after south-eastern style pottery had arrived on the site, probably during the first century AD. Occupation continued into the Roman period. A similar continuity into Roman times was demonstrated by the multivallate enclosure at Sudbrook, where the defences came late in the sequence, post-dating occupation containing first-century BC saucepan pots. The levels contemporary with the defences contained a mixture of first-century AD pottery continuing until early Flavian times.

Both of the sites so far considered lie at the east side of the territory, where influence from Dobunnic and Roman culture might be expected. Further west, however, along the Glamorganshire coast, the material culture is far less well represented. The forts which have been excavated, the Knave, the Bulwarks, the West Fort on Harding’s Down, Bishopston Valley Fort and High Penard, have produced very little apart from a few imported sherds of South-Western Decorated Ware, odd scraps of Roman pottery and a few indeterminate sherds. Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that the forts were in use during the last century of Silurian independence.

Only two settlements have been excavated on any scale. At Mynydd Bychan, a walled enclosure was examined containing a group of circular huts. In the first period the buildings were of timber but later they were rebuilt in stone within walled courtyards. Occupation began in the latter part of the first century BC and continued probably as late as Flavian times, the later decades being characterized by the appearance of wheel-turned vessels manufactured in the south-eastern manner but in an orange-buff fabric.

The farmstead at Whitton presented a rather different sequence. Here a rectangular ditched enclosure was built c. AD 30 to defend a series of circular timber-built houses. Occupation continued until the end of the century, when rectangular timber buildings replaced them. These in turn were succeeded by simple masonry-based buildings in the second century. The evidence suggests a largely unbroken sequence spanning the period of transition from freedom to incorporation with little trace of a change in status.

From the inception of the Fosse frontier in AD 47, Silurian territory would have been in close contact with the Roman world, and the foundation of the fortress at Usk in c. 55–60, followed by several decades of campaigning before the final annexation in c. AD 74, would soon have brought the natives of the coastal plain into an intimate relationship with the Roman army. It may well have been under these conditions that the south-eastern style ceramics were introduced from Dobunnic territory (Spencer 1983).

The Demetae

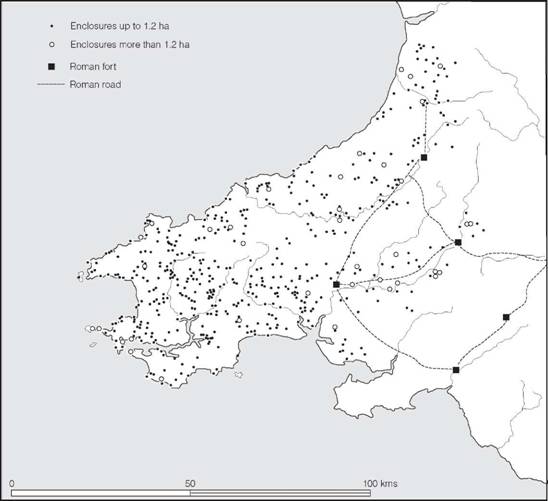

The Demetae occupied the extreme south-west corner of Wales, probably extending along the valleys of the Tywi and Teifi into the foothills of the Cambrian mountains. Much of the more hospitable parts of this territory was densely scattered with small enclosed settlements, usually 0.4–1.2 ha in extent, comparable in many ways to the rounds of Cornwall (Figure 9.3). Excavations at Walesland Rath, Pembs., have demonstrated the existence of a moderate-sized community living in a cluster of circular huts from the first century BC into the first century AD. In the second century, after a period of abandonment, the site was reoccupied by a community existing in much the same way as before, but now living in a simple rectangular stone building and using Romanized pottery. Continuity of this kind may also be suspected at two nearby sites, Cwmbrwyn and Trelissey, where Romanized buildings have been excavated inside apparently earlier earthworks. Not all of the native sites which continued in use into the Roman period and beyond showed evidence of Romanized improvements, as a series of comprehensive excavations in the Llawhaden region have amply demonstrated (Williams 1988). This pattern of unhampered indigenous development spanning many centuries may well have been even more deeply rooted. Indeed, the discovery of La Tène I bracelets at Coygan Camp tends to emphasize the antiquity of settlement in the area, but the extreme paucity of artefacts makes any assessment of material development and chronology a matter of difficulty for the pre-Roman phases.

The coast line of the extreme south-west supports a considerable number of cliff castles closely similar to those of Devon and Cornwall and Armorica. Around the coasts of Pembrokeshire alone fifty-five have been identified (Crane 2001, figure 1) but few have been examined by excavation. Work at Great Castle Head, Dale, Pembs., however, shows the promontory to have been defended over a period of time extending into the Late Iron Age.

Several observers have pointed out the relative lack of Roman military activity in the southwest of Wales, suggesting that the Demetae offered no resistance to the advance and therefore required no substantial holding force save a garrison based at Carmarthen. If this were so, it would explain the peaceful uninterrupted occupation of the peasant villages and hamlets – a process which, on present evidence, offers some contrasts to the settlement of the hostile Silurian territory.

The Ordovices, Gangani and Deceangli

The settlement pattern of north Wales appears to have been little affected by the events of the late pre-Roman Iron Age in the south-east of the country. The material culture remained as sparse as ever and many of the sites continued to be occupied well into the Roman period with little evidence of significant change. The Roman campaigns of AD 47–51 and indeed the Roman presence in Britain from AD 43 tend, however, to be reflected in the structural development of some of the defended sites. At Dinorben, Denbigh., it has been suggested that the final reconstruction of the ramparts on the south side of the fort (period V) could have resulted from Roman threats in the neighbourhood, while at Castell Odo, Caerns., the slighting of the defences may have been carried out by the Romans in the last quarter of the first century AD.

Perhaps the most impressive feature of the settlement pattern of the area is the continued use of the hillforts like Tre’r Ceiri, Caerns,, with their densely occupied interiors, and the development of large numbers of enclosed farmsteads usually working on average 6 ha or so of associated terraced fields (Smith 1978b; Smith 2001). While the exact origin of this system is still in some doubt (Hogg 1966), it is clear that the social grouping and some aspects of the architecture must relate to pre-Roman tradition and it would indeed be surprising if many of the farms in use in the Roman period did not originate in the first century BC or even earlier.

Figure 9.3 Settlements in south-west Wales (source: G. Williams 1988 with additions).

Few settlements have yet been excavated on anything approximating to a useful scale. One exception is Bryn Eryr on Anglesey, which was occupied apparently continuously from the Middle Iron Age to the end of the Roman period, the late Roman phase being represented by a rectangular enclosure containing a pair of houses set within a farmyard. Two settlements at Crawcwellt West and Bryn y Castell, in Merioneth, were both engaged in iron production, as well, presumably, as farming, in the Late Iron Age, providing an interesting insight into the specialized economies of these remote upland settlements.

The Cornovii

According to Ptolemy, the territory of the Cornovii included both the cantonal capital at Viroco- nium and the legionary base at Deva (Chester), which in terms of modern counties would have meant that the tribe occupied Cheshire and Shropshire and probably parts of surrounding areas. To the south, their boundary with the Dobunni probably approximated with the river Teme, an east-flowing tributary of the Severn; in the east they would have met the Corieltauvi in the Trent valley; and to the north the boundary with the Brigantes may have lain along the Mersey. The western limit of the tribal territory is far more difficult to define. The great number of defended enclosures in the hills and mountains of the Welsh borderland could equally well have been under Ordovician domination, but the structural peculiarities of some of the larger forts (e.g. Old Oswestry, the Breiddin, Ffridd Faldwyn and Titterstone Clee) tend to link them more with the forts of the south and east, suggesting a zone of contact, although this does not necessarily imply that the borderland forts belonged to Cornovian territory. The absence of coins and the relative lack of finds make the definition of the tribal boundary hereabouts uncertain and indeed the very identity of the Cornovii is difficult to define in terms of distinctive material culture (Wigley 2001; Philpott 2001).

In the century or so before the Roman Conquest, the area seems to have continued to develop along earlier lines uninfluenced by the social and economic systems of the south-east. Many of the hillforts were kept in defensive order, and a little pottery and fine metalwork was imported from outside the area but, like the other territories outside the aggressive range of the southeastern chieftains and of their trading patterns, there was little discernible change until the entire territory was annexed by the Roman army led by Ostorius Scapula, in and soon after AD 48.

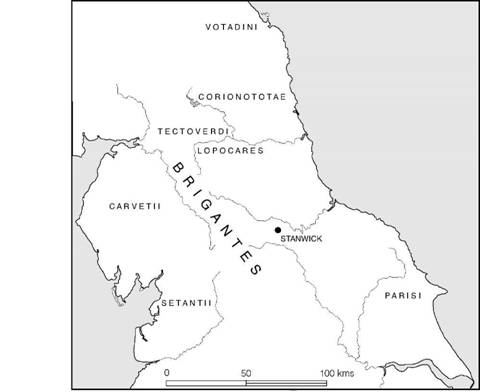

Northern England (Figure 9.4)

The Greek geographer Ptolemy writing in the second century AD tells us of a northern tribe, the Brigantes, whose territory stretched from ‘sea to sea’ (Geog. ii, 3, 10). This vision of a northern people, ‘the most populous in the whole province’, was also conjured up by Tacitus writing of the Conquest of Britain (Agricola, xvii, 2). From these descriptions has sprung the modern construct of Brigantia, conceived of as a vast territory extending from the Peak District to Hadrian’s Wall and from the Irish Sea to the North Sea, a political and cultural monolith. The vision is given enhanced respectability by the story of the Brigantian queen, Cartimandua, and her husband Venutius, who make an appearance in the works of Tacitus. Much has been written on the subject, especially by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in his report on the excavations at Stanwick (Wheeler 1954), and for some while Wheeler’s interpretation of the Brigantes and their history was widely accepted; but new work at Stanwick and several reviews of the northern evidence (Braund 1984; Haselgrove 1984a; Higham 1987) have refocused attention on the varied and complex nature of the evidence and have amply demonstrated that many old preconceptions must now be abandoned.

The Brigantes were not the only tribe to be recorded in northern England. The Parisi were noted by Ptolemy and may be equated with the archaeologically defined Arras culture occupying the Yorkshire Wolds north of the Humber. Several other tribes mentioned by Ptolemy in the west and north of the territory can also be approximately located, though their cultural attributes are less well known.

Figure 9.4 The tribes of northern England (sources: various).

While there can be little doubt that the dominant force at the time of the Roman invasion was the Brigantes, the other tribal groups should not be overlooked, nor should the whole north be written off as a monolithic ‘Brigantian confederacy’. A far more likely model would be to see the Brigantes (whose name means ‘high ones’) as having hegemony over their neighbours, whose position was that of clients. The Brigantes themselves probably occupied the Pennines and their flanks, thus commanding not only a central position controlling the principal routes north to south and east to west but also having access to a range of varied and well-drained and fertile soils (Higham 1987). In their geographical position probably lay the basis of their power.

The Brigantes and their neighbours

Relatively little is known of the settlement pattern and economy of the north at this time, but the varied geology and altitude, and the considerable differences in rainfall on either side of the Pennine ridge, have created various different micro-environments demanding different economic strategies. The traditional generalization – that the Brigantes were largely pastoralists (Wheeler 1954; Piggott 1958) – must now be abandoned in the face of growing evidence of agriculture in the north-east both from the results of pollen analysis (Turner 1979, 1981) and from actual crop remains recovered from sites such as Coxhae, Co. Durham, Thorpe Thewles, Cleveland, and Stanwick and Rock Castle, North Yorks. (Van der Veen 1992). The large numbers of beehive querns found in north-eastern Yorkshire, artefacts which are closely associated with good arable land, is a further indication of widespread agricultural activity, though the type is not exclusively of Late Iron Age date (Hayes, Hemingway and Spratt 1980; Gwilt and Heslop 1995). Animals, however, played a significant part in the economy, cattle being the most numerous. Clearly a mixed economy must have been practised over much of north-eastern Britain at this time, though the specific regimes will have varied from area to area (Haselgrove 1984a).

In the Pennine valleys early field systems, such as the well-preserved groups in Wharfedale and adjacent valleys, are a further indication of agricultural activity, but flocks and herds may well have been tended in upland pastures for much of the year. The use, well into the Roman era, of caves and isolated huts on the Pennine moors is an indication that a transhumant economy continued to be practised for many centuries. There is little evidence yet available for settlement and economy in the north-west at this time, but high rainfall would have made the arable strategies of the drier north-east less appropriate and there may well have been a greater reliance on animal husbandry.

Apart from dimly conceived differences between economic systems there is little evidence on which to distinguish regional or tribal variation. Ceramic technology was ill-developed (Evans 1995). Northern pottery consists almost entirely of coarsely made cooking and storage vessels, generally without decoration and of simple form lacking distinctive characteristics. No doubt most of the containers were made of wood, basketry, horn and leather – materials more appropriate to the needs of a society practising a degree of mobility. An example of an elegant wooden dish was found in a waterlogged deposit at Stanwick. That the population was not entirely unappreciative of fine pottery is, however, vividly demonstrated by the high percentage of imported wares found at Stanwick: of all the pottery recovered, some 60 per cent consisted of samian ware, butt-beakers and other Roman imports from the south.

With the exception of Stanwick there is little evidence of centralized settlement in the north. Of those hillforts which have been excavated, Almondbury, Yorks., Mam Tor, Derbyshire, Cast- ercliff, Lincs., and Skelmore Head, Lancs., none appears to have been occupied after the fourth century BC and the normal unit of settlement remained the isolated farm of family or extended family size. Against this background the earthworks of Stanwick stand out in stark contrast.

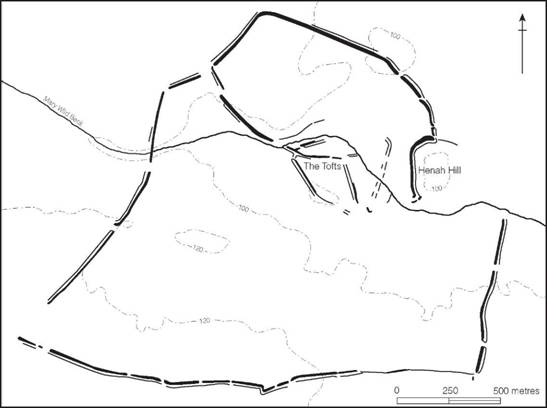

Stanwick lies at the junction of two major routes, one running along the east side of the Pennines joining the south to Scotland and the other branching west across the mountains through the Stainmore Pass. The site now consists of over 300 ha of pasture and arable land enclosed and traversed by 10 km of massive earthworks surviving in places to a height of 5 m (Figure 9.5). The choice of location and the vast investment of energy in its fortification fairly reflect the great economic and political importance of the place, sited as it is in the heart of Brig- antian territory.

The potential interest of the site was fully appreciated by Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who chose it as a research project in 1951 and 1952. Wheeler’s excavations were limited but his conclusions were far-reaching (Wheeler 1954). He saw Stanwick as a military stronghold of the Brigantes – a rallying place for anti-Roman resistance, beginning with a 7 ha enclosure, the Tofts, constructed in c. AD 47–8, which was then enlarged in two stages. In its final form Stanwick provided protection for the tribe in its last stand against the Ninth Legion led by Petillius Cerialis in a victorious sweep through the north in 71–2.

A more recent programme of fieldwork and excavation has shown that the structural sequence proposed by Wheeler has to be modified and that his military interpretation of the earthworks is likely to be incorrect (Chadburn 1983; Turnbull 1984; Haselgrove et al. 1991). It now seems quite possible that most of the system was laid out as part of a single plan, probably in the middle of the first century AD, although by that time part of the site, the Tofts, was already inhabited. The straggling earthworks and vast enclosed area are highly reminiscent of the territorial oppida of the south. This, together with the surprisingly high proportion of luxury pottery imported from the south suggests that Stanwick may have served, in much the same way as the southern oppida, as a centre of tribal power where long-distance trade was articulated with local distribution networks. The evidence for metalworking (Spratling 1981) is entirely consistent with this view for at such centres raw materials would be given added value through refinement and manufacture.

Figure 9.5 The Stanwick fortifications (source: Haselgrove, Turnbull and Fitts 1991).

The dating evidence suggests that occupation began at about the time of the Conquest and declined in the later decades of the first century AD. This is entirely explicable against the background of the early military history of the province (chapter 10). The initial intention was to secure only the south-east, and to this end a frontier zone was established from Lincoln to Exeter. Though further campaigning, followed by expansion, took place in the Midlands and Wales, the north was left as a friendly buffer state ruled by Queen Cartimandua until the early 70s. In such a context the development of vigorous trading relationships between the province and its northern neighbours would be expected. Stanwick, deep in Brigantian territory and commanding the major routes, was admirably sited to serve as the principal entrepôt where the Brigantian monopoly, established through treaty with the Roman authorities, could be exercised, further strengthening their hegemony over their lesser neighbours.

The situation in the north was politically unstable. Literary evidence relating to the first century AD provides several glimpses of the factions and rivalries within upper echelons of society, and it may fairly be supposed that these reflect the deep divisions that might be expected within the structure of a people divided by tribal loyalties and whose territory and resources were so diverse. The flamboyant and aggressive aspects of this northern society are manifest in a group of distinctive swords (Piggott’s class IV) made, no doubt, by a single school of craftsmen for the northern élite, and, by the scattered discoveries of horse-trappings including the remarkable hoard found at Stanwick in 1845 (MacGregor 1962; Fitts et al. 1999) which contained a sword, a wide range of chariot- and horse-trappings and a number of fragments of personal equipment. While the exact nature of the Stanwick hoard must remain in doubt, it provides a vivid impression of the degree of wealth and display attained by the upper classes of Brigantian society at the end of their period of freedom.

The Parisi

On the east flank of the Brigantes lay the Parisi, occupying the territory stretching from the Humber estuary to the north Yorkshire moors. The region was in close contact with northern France in the late fifth century, giving rise to the Arras culture (pp. 84–6 and Stead 1979), which developed possibly after a small-scale folk movement brought a new élite into the area from the Seine valley. Stead has demonstrated a degree of continuity from the fifth- or fourth-century beginning until the Roman Conquest, unhindered by any further Continental contact – a fact which has led him to support the idea that the tribal name of Parisi, recorded by Ptolemy in describing the situation in the first century AD, must date back to the fifth to fourth centuries. He further points out that the closest parallels for the Yorkshire burials occur in the territory of the Gallic Parisii.

The cemeteries of the Arras culture at Dane’s Graves and Eastburn continued in use throughout the first century BC and well into the first century AD. There was little change, except that metal associations were rare in the later periods and, where objects occurred at all, they related more directly to the developing styles of southern Britain. Pottery buried with the dead, however, became more common. At Wetwang Slack the only discernible difference in a long-established cemetery, laid out along a track, was that in the Late Iron Age a ditch had been dug through many of the old burials to delimit a more restricted cemetery zone. By the Late Iron Age, however, the rite of vehicle burial had been totally abandoned throughout the region of the Arras culture.

One new element to appear in the area during the first century BC was the rite of single warrior inhumation – known from North Grimston, Bugthorpe and Grimthorpe, all sited along the western side of the Wolds. The presence of weapons and lack of indigenous features – such as the cart buried with the body, rectangular enclosures and barrows – suggest a different tradition and ritual. It is, however, quite unnecessary to define a separate culture (as Stead 1965, 84, who calls it the North Grimston culture). It is simpler to regard the burials, which are similar to others found in various parts of Britain, as representing a general and widespread change. What exactly the new styles of burial mean is less clear; in all probability, it is little more than a change of fashion, but the possibility that it signifies the presence of extra-tribal mercenary warriors or simply a more warlike tendency in society should not be overlooked. In this connection, the discovery at Garton Slack of small chalk-cut figures carrying swords might be taken as evidence of a new militarism (Stead 1988, 32–4). Another change noted at about this period was the preference for laying out the body extended rather than crouched which was noted at the Rudston, Makeshift, cemetery (Stead 1991).

Settlement morphology and economy among the Parisi is becoming much better understood as the result of the large-scale excavation of extensive, but scattered settlements in the valley of Garton and Wetwang Slack (Dent 1982, 1990), where there is some evidence to suggest that, by the Late Iron Age, hitherto open settlements were being enclosed. Elsewhere, for example at Rillington, near Malton, complex patterns of enclosure had already been established a century or two earlier. Continuity of occupation into the Roman period is demonstrated at the ditched enclosures at Langton and Staxton: at Langton, and again at Rudston, Late Iron Age settlements were eventually replaced by Roman villas. The overall impression given by the settlement evidence is of continuity and gradual change.

The quality of ceramic production improved throughout the first centuries BC and AD, probably under the influence of traditions emanating from the territory of the Corieltauvi across the Humber. Such an improvement would be consistent with the gradual introduction of a more settled economy. The development can perhaps best be seen by comparing the coarse plain vessels from Dane’s Graves with the later collection from an occupation site at Emmotland in Holderness (Brewster 1963). The Emmotland vessels not only are better made and finished but are constructed in more positive forms, mostly jars with everted rims but occasionally bead- rimmed jars and small bowls reminiscent of the styles from the south. A scatter of Claudio- Neronian brooches from Parisian territory, together with the large quantity of imported Gallo-Belgic wares from North Ferriby on the north bank of the Humber, leaves little doubt that trading relations had been established with the south by the Claudian period, if not earlier. North Ferriby may well have been the principal ‘gateway community’ through which products from the Roman province south of the Humber were introduced into the territory of the Parisi (Dent 1990). A settlement, producing a similar range of material, lay on the opposite bank at South Ferriby and must have been part of the transshipment system. It is possible that this was the way by which commodities entered barbarian territory en route to Stanwick, though some must have been deflected into the hands of the Parisian élite. An awareness of the material advantages of Romanization may have been instrumental in encouraging the tribe to offer no resistance to the eventual penetration by the Roman army in 71–2.

Southern Scotland: Votadini, Novantae, Selgovae and Damnonii (Figure 9.6)

Between the Tyne–Solway and the Clyde–Forth lines, which later approximated to the frontiers constructed under Hadrian and Antoninus Pius, four major tribal groups can be distinguished. The Votadini occupied the eastern coastal region and the lowlands between the Tyne and the Clyde, the Novantae covered the area of Galloway and Dumfriesshire, while the Selgovae lay between the two. North of the Novantae and stretching along the west coast to the Clyde was the territory of the Damnonii. How significant were the social and political differences between the groups at the time when they were distinguished by Roman writers in the first and second centuries AD it is impossible to say, except that the Votadini appear to have been more generously treated by the Romans than their neighbours the Selgovae, an observation which, if substantiated, might hint at a distinction between tribal policies. Nor is it possible to define how far back in time tribal distinctions can be traced, since there is no historical or numismatic evidence upon which to base conclusions. Any description of the area must, therefore, rely substantially on the form and distribution of settlement sites and upon the somewhat sparse material culture recovered by excavation.

Figure 9.6 The major tribes of northern Britain (sources: various).

While a very large number of settlement sites are known in the area, as a result of extensive field surveys carried out by the staff of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments and by G. Jobey, it is extremely difficult to assign dates to them, except for the earlier sites (p. 60) for which a number of radiocarbon determinations are available. On typological grounds, however, two major classes of settlements and homesteads can be defined as belonging to the period stretching from the end of the pre-Roman Iron Age into the Roman era: ‘scooped enclosures’, consisting of walled enclosures containing huts and yards terraced into the natural slope of the hill, and settlements of stone-built huts. The latter are relatively common, particularly in the territory of the Votadini, but any apparent differential distribution may be due largely to different intensities in the archaeological fieldwork. The dating evidence obtained for some of these settlements suggests an initial occupation in the second century AD, but this does not preclude an earlier beginning for others. The abandonment of many of the small hillforts and defended enclosures probably occurred throughout the first century AD, but no indisputable dating evidence survives and it may well be that some at least continued in use. By the end of their life, many of them had developed into multivallate structures, some with close-set defences, others with their ramparts more widely spaced in a manner similar to that of the multiple-ditched enclosures of south-west Britain.

Many of the larger hillforts evidently continued to be occupied. The principal fort of the Votadini, the long-established Traprain Law in East Lothian, may have remained the tribal centre throughout the Roman occupation but there is little indisputable evidence for this. The Selgovian centre on Eildon Hill North, Roxburgh, seems to have been abandoned before, perhaps long before, the time of the Flavian advance. A general consideration of the forts of both the Selgovae and the Votadini tends to suggest a gradual amalgamation of nucleated communities at an increasingly restricted number of sites in a manner paralleled in southern Britain. This might well represent a growing political cohesion which eventually manifested itself in organized tribal attitudes to Rome. Herein might lie the reason why Agricola subdued the eastern areas of Scotland first, before turning his attention to the more fragmented Novantae and Damnonii, where there are only four hillforts in excess of 2.5 ha compared with thirteen in the territory of the Selgovae and Votadini.

A few brochs are known in Votadinian territory, with rather more spreading down the west coast into the lands of the Damnonii and Novantae. One can be shown to be secondary to the multivallate hillfort at Torwoodlee, Selkirk, while at Edin’s Hall, Berwick, a broch follows a hillfort but is replaced by a stone-built settlement. Dates ranging from the first into the second century AD are indicated for the occupation of the southern brochs where there is sufficient material to indicate a chronology. Various suggestions have been made to explain the occurrence of brochs in the area, including the importation of broch-building mercenaries by the Votadini, following the first Roman withdrawal from Scotland, but the matter must remain beyond proof.

Northern Scotland (Figure 9.6)

North of the Forth–Clyde line the names of some twelve tribes are recorded, but since they are not easy to differentiate historically or archaeologically it is simpler to describe the area and its settlements in general terms.

The Highland Massif, the homeland of the Caledonians, divides the area into two: the eastern coastal region occupied by the Venicones, the Vacomagi and the Taezali; and the north and west coasts and islands (the Atlantic province) settled by the Epidii, Creones, Carnonacae, Caereni, Cornovii, Smertae, Lugi and Decantae. In the north-eastern region the basic folk culture continued largely unchanged. Defended settlement sites, duns, hillforts and occasional brochs occur but are relatively little known in archaeological terms. It was through this area that the last campaigns of Agricola were fought, and it was somewhere here that the great army of the Caledonians under their leader Calgacus met its defeat, leaving the countryside depleted for a generation or two. Events of this magnitude must have left their mark on the settlement pattern but it still remains to be defined.

The Atlantic province, largely untouched by Rome, continued to develop in relative isolation, giving rise to a range of highly distinctive structures and a material culture well adapted to the needs of the environment. Reassessing the evidence in 1934, Childe referred to the structures of the area as the castle complex, in order to emphasize the basic unity of the hundreds of small forts, duns and brochs which characterized the densely fortified landscape. Broadly speaking, these ‘castles’ can be divided into duns and brochs, both of which can be further subdivided on the basis of their form, siting and regional distribution (MacKie 1965c, figure 2). The details of these structures are considered below (chapter 14) and need not concern us now.

The material culture belonging to the settlements of the Atlantic province presents much the same variety as that of the contemporary sites in the south, with the one exception that iron was never plentiful. Bone was made into needles, awls, gouges, bobbins, long-handled combs, spindle whorls and dice; bronze was used for ring-headed pins and spiral finger-rings; while stone of various kinds continued in use for tool-making, for the production of armlets out of jet and for the manufacture of small vessels. Another similarity to southern Britain is that pottery was well made and relatively plentiful in the Western Isles; moreover, it is susceptible to regional and chronological division. In the west several distinct styles have been defined; these include Clettraval ware, characterized by globular jars with everted rims, decorated by a finger-pinched girth cordon with concentric channelled semi-circles in a zone above (Figure A:40). Alongside the later stages of the development, Vaul ware appears in two basic forms: large barrel-shaped urns and smaller jars with an S-shaped profile and slightly everted rim; both types are often decorated with incised geometric patterns. Broadly contemporary with the Vaul wares are the barrel-shaped Balevullin vessels with finger-printed girth cordons, sometimes ornamented with simple incised patterns. Such dating evidence as there is suggests that these decorated wares belong to the second century AD.

In the northern area of Orkney, Shetland, Caithness and Sutherland incised and cordoned wares are almost entirely lacking. Instead, the commonest types are tall jars with small beaded or everted rims, sometimes with well-burnished surfaces, which developed out of the pre-broch wares at Clickhimin and can therefore be referred to as the Clickhimin IV style. The type is widespread in the north and occasionally penetrates into the west. The main feature is the shouldered jar with internally fluted everted rim (Figures A:38 and A:39). Sometimes cordons are applied at the junction of rim and body and a few examples have bases internally impressed with patterns of finger-marks.

Very few well-stratified sites have yet been adequately examined in the Atlantic province, but the range of material now available from Clickhimin, Jarlshof, Dun Mor Vaul, Dun Vulan, Dun Bharabhat, Crosskirk, Bu Broch, etc., is at last allowing the copious material culture to be arranged in a sequence related to structural development. A first assessment of this was offered by MacKie (1965c, figure 6), but until more excavation has been undertaken and thoroughly published, details of sequential development and regionalism will remain unclear.

Childe believed that the broch culture arose as the result of intrusive elements emanating from south-west Britain (1935b, 237–9; 1946, 94). This view was expanded by Sir Lindsey Scott (1948), who attempted to show that the pottery, as well as the architecture and the rest of the material culture, could be derived directly from the south-west and that in his view the entire culture was introduced by ‘colonists’. MacKie (1965c) has argued convincingly for the indigenous development of the broch and the wheelhouse together with much of the ceramic tradition, but still retained the belief (1969a) in an immigration from the south some time in the first century BC. As D.V. Clarke (1970) has shown, however, the supposed evidence for immigration is entirely unconvincing and can all be explained in terms of trade and other forms of peaceful contact not requiring folk movement.

By the time of the Roman invasion, the Northern and Western Isles were very strongly defended by more than 500 families living in their broch towers. The fact that in AD 43 a treaty was concluded between the Roman fleet and the Orcadian chieftains is perhaps indicative of their significance in the eyes of the Roman commanders. The treaty probably continued to be honoured, for when Agricola destroyed the mainland resistance in the battle of Mons Graupius in AD 84, he was able to claim that the conquest of Britain had been completed, though not before the islands had been visited by the Roman fleet.

In the ensuing peace the fortifications were gradually dismantled and were replaced by wheel- houses representing a resurgence of the native traditions of domestic architecture. Local economy flourished at first and trading relations were maintained with the Roman world, during which time luxury goods like glass and pottery together with a few coins trickled in, but with the collapse of the Roman administration in the south a decline set in and the material culture became much simpler until it was once more reduced to a level not unlike that of the Late Bronze Age.