14

Settlement and the settlement pattern in the centre and north

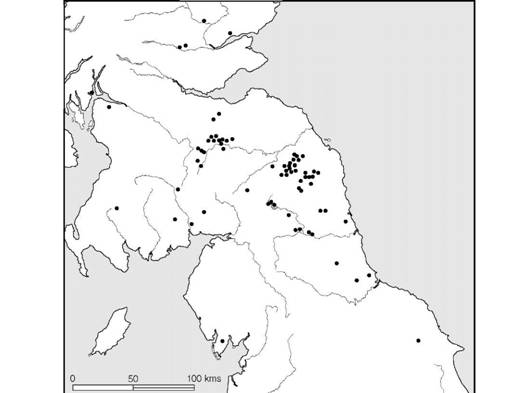

Any cognitive geography that attempts to divide a land mass into regions is bound, to some extent, to be forced into arbitrary decisions. Strict use of geomorphology is one approach. If we had adopted this rigorously, then the logic would have been to take the Jurassic scarp as one boundary and the Welsh Borderland as another, leaving what used to be called in the old geography books ‘The Midland Triangle’ as part of the centre but including the Yorkshire Wolds and Tabular Hills in the south. Another approach might have been to adopt the divisions so elegantly argued by the historical geographers Brian Roberts and Stuart Wrathwell in Region and Place (2002), but their entirely convincing regionalization is determined to a significant extent by developments in the second millennium AD and to adopt it for the first millennium BC would be anachronistic. The divide adopted here is something of a compromise, resting partly on geo- morphology and partly on an appreciation of the archaeological evidence, with the centre beginning at a line roughly coincident with the Dee valley, the northern edge of the Trent basin and the Humber.

To the north of this line the centre and north of Britain have for convenience been divided into three broad zones: the Pennines and central Britain; the Tees–Forth region; and western Scotland and the Western and Northern Isles. Needless to say, each of these zones is capable of subdivision into many different regions.

The Pennines and central Britain

The north of England is geomorphologically varied and is best considered as a number of distinct sub-zones. Through the centre runs the backbone of the Pennines, composed largely of Carboniferous limestone and Millstone grit capped with large tracts of moorland, even today creating a real barrier between the two faces of northern England. East of the divide the landscape falls naturally into three sub-zones. To the south are the chalk Wolds and the limestone Moors divided from each other by the Vale of Pickering, which is itself part of an extensive tract of lowlands drained by the river system of the Ouse and Swale serving to separate the calcareous massifs of the east from the Pennine ridge. West of the Pennines the Lake District massif forms a major barrier between the coastal plain of Cheshire and Lancashire and the lowlands drained by the rivers flowing to the Solway Firth. Variation in climate, geology and altitude serve to create a palimpsest of micro-environments, while mountain ridges and wide river flood plains present barriers to easy communication. It is hardly surprising therefore that the settlement potential of each region has imposed its stamp on settlement pattern.

For a long while knowledge of Iron Age settlement was confined to evidence from a few well- excavated sites. More recently, however, not only has the number of excavations increased but a series of regional and general surveys have been prepared. Among the more important may be listed three overviews of the available pollen sequences which allow the framework of localized environmental change to be sketched out (Turner 1981; Wilson 1983; Simmons et al. 1990; Simmons 1995), and a series of regional surveys including the Wolds (Ramm 1980; Stoertz 1997), the North York Moors (Spratt 1982) and the Pennine Dales and the Aire–Wharfe drainage system (West Yorks CC 1981). The whole of the north-east region has been thoroughly reviewed by Haselgrove (1984a, 1999). No comparable surveys are yet available for the far less well-known zone west of the Pennines. In the pages to follow, the better-recorded settlements will be briefly discussed.

The Yorkshire Wolds

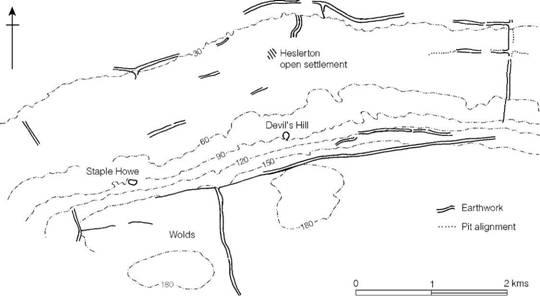

The best known of the Yorkshire Wold settlements is the site of Staple Howe, situated on a chalk hillock overlooking the Vale of Pickering (Figure 14.1). Here a farmstead dating to the seventh to fifth centuries has been substantially excavated, revealing an oval palisaded enclosure, subsequently remodelled, containing several huts and a massively constructed five-post rectangular granary. The excavator has suggested that in the first phase the only hut in use was an oval structure which was subsequently replaced by two circular huts. While the circular huts are of generalized type similar to those found over most of southern Britain, the oval hut is more unusual: its roof appears to have been constructed around a horizontal ridge-post supported on two verticals, while the lower ends of the rafters would have rested on the ground or upon dwarf walls constructed of turf or chalk. In addition to large quantities of pottery and a range of imported bronze objects referred to below (p. 458), the surviving material remains included masses of animal bones, principally of cattle, sheep and swine, together with an amount of carbonized grain, all of which proved to be club wheat (Triticum compactum).

The same general pattern of economy is reflected in the evidence from the hillfort of Grimthorpe, which occupies a somewhat similar position on the west edge of the Yorkshire Wolds, overlooking a low-lying area of densely wooded Keuper marl. Within the defences of the fort were found eight four-post granaries, emphasizing the importance of cereal growing. The animal bones showed a preponderance of cattle – 55 per cent compared with 25 per cent sheep; pigs (7.8 per cent) were only a little more plentiful than horses (7.3 per cent). If these figures are corrected for actual meat yield, beef consumption would be seen to amount to about 82.4 per cent of the total meat intake. A more detailed examination of the cattle bones shows that more than 70 per cent of the herd was maintained over two winters before eventual slaughter. Sheep, on the other hand, were killed off at a constant rate. The implications are clear enough: the economy was sufficiently stable for extensive over-wintering, a fact which in itself adds support to the view that corn growing, producing straw fodder, played a significant part in balancing the complex processes of food production. Clearly, then, mixed farming was practised – indeed, there is very little difference between the socio-economic basis of Staple Howe and Grimthorpe and that of a typical Wessex farm, except for the absence of querns and storage pits. Since, however, storage pits were rare or unknown among the southern sites before the fifth century BC, their absence from the early Yorkshire sites is hardly surprising. The lack of querns is a little puzzling, but this may be nothing more than an accident of survival.

Figure 14.1 Staple Howe, Yorks. (source: Brewster 1963).

Staple Howe, Grimthorpe and Thwing belong to the first half of the first millennium BC and it was probably in this period that the linear ditch systems which traverse the Wolds were constructed (Ramm 1978; Manby 1980; Stoertz 1997). These boundaries are similar in form and date to those found in Wessex and on the North York Moors, and presumably reflect a need to demarcate social territories possibly associated with grazing rights. A very clear example of the relationship between linear boundaries and settlement is provided by a study of part of the northern scarp of the Wolds, where the two enclosed settlements of Staple Howe and Devil’s Hill situated prominently on the chalk scarp slope overlook the open settlement of Heslerton (Powlesland 1988) (Figure 14.2). Heslerton comprised at least seven roundhouses, enclosures and four-post ‘granaries’ and appears to have been occupied for several centuries. Though the exact contemporaneity of the three sites has still to be convincingly argued, their apparent relationship to boundaries formed by linear earthworks and pit alignments argues for a high degree of social organization.

Some indication of the developing settlement pattern in the valleys is provided by an extensive and straggling settlement excavated at Garton and Wetwang Slack. The settlement consisted of a number of circular houses 9 to 12 m in diameter, built of timbers placed in bedding trenches. The discovery of carbonized grain, grain storage pits, often within the houses, and four- and six- post granaries, is a fair indication that cereal growing played an important part in the economy. A date in the fifth/fourth century is indicated by a single radiocarbon date. By the third and second centuries changes were taking place. The straggling settlement was now replaced by a nucleated settlement with associated fields, while an extensive cemetery was allowed to develop along the valley road. The cemetery was carefully defined by a linear earthwork. A little later, in the first century, ditched enclosures, possibly for animals, were added.

Figure 14.2 Boundary systems on the north scarp of the Yorkshire Wolds (source: Powlesland 1988).

The type of linear settlement so vividly demonstrated by the excavation of Garton and Wetwang seems to have been widespread in the Wolds, where they are usually referred to as droveways or ladder settlements and are known largely from air photographs. A typical settlement of this kind usually has ditched enclosures running for up to a kilometre along a droveway, with field systems defined by ditches beyond. Settlements of this kind have been examined at Rudston, North Cave and Brantingham.

The settlement pattern on the Wolds, together with the extensive evidence for burial practice (pp. 546–50), is now beginning to allow broader discussion of the relationship of the living and the dead within the landscape. The Yorkshire Wolds are unique in providing such a range of data (Bevan 1997, 1999).

The North York Moors

The Moors are essentially an upland zone fringed with lower-lying areas of better-quality soil. The upland areas were divided into great tracts of pasture land by natural features enhanced by a series of linear earthworks and by pit alignments (Spratt 1982; Vyner 1995), suggesting a predominantly pastoral use formalized in the early first millennium BC and presumably continuing throughout the Iron Age. However, the distribution of beehive querns, an artefact of the first century BC and first century AD, which corresponds precisely to the distribution of good arable land, suggests that by the first century BC the agrarian base of the economy was becoming well established (Hayes, Hemingway and Spratt 1980). Settlements are not well known but sub- rectangular or D-shaped enclosures containing circular houses have been recorded at Great Ayton Moor, Levisham Moor and Roxby (Spratt 1990, 142–54).

The Pennines and the west Pennine fringes

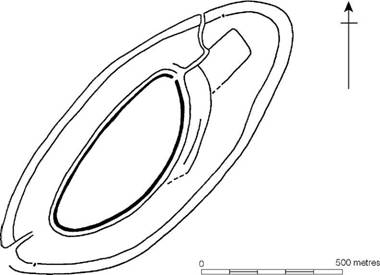

West of the Vale of York lie the Pennines, offering three basic environments to potential settlers: the upland limestone areas of Derbyshire and the Yorkshire Dales, the acid ill-drained moors of the coal measures and millstone grit, and the wide valleys floored with glacial drift which dissect the range. Little is known of the area in the pre-Roman Iron Age, but several large hillforts are recorded. At Castle Hill (Almondbury), Yorks. (Figure 14.3), overlooking the valley of the Holme, substantial annexes were added close to the main entrance of the fort, and later an outer series of banks and ditches were constructed to enclose the annexes and the original fort together with a considerable hectareage of protected pasture. Such an arrangement, which has parallels in the Welsh borderland and Wessex, strongly suggests the increasing importance of livestock, which needed protection.

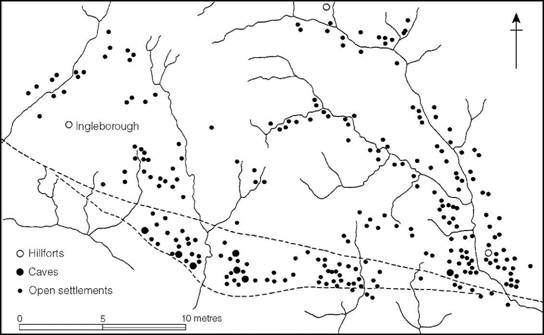

The limestone hills and valleys between the rivers Wharfe and Greta, where intensive field- work has been carried out, were densely settled (Raistrick 1939; White 1988) and there is no reason to suppose that other limestone areas were any less thickly inhabited (Figure 14.4). Three types of settlement have been defined, the most common being the isolated hut, or sometimes a pair, set in a small embanked enclosure with a field or two nearby. This type is found mainly on the limestone plateau. The second type of settlement is the larger nucleation of huts which might reasonably be referred to as a village. One of the best-known examples, at Grassington in Wharfedale, consists of about 0.8 ha of huts and enclosures associated with about 33 ha of rectangular fields. The third type of site is the inhabited cave, quite often with a group of small fields laid out close by. The nature of the economy seen through the material culture is clear enough: grain was grown but in relatively small quantities, the principal food-sources being meat and milk from the flocks and herds. The relative percentages of cattle and sheep are uncertain, but the equipment of spinning and weaving occurs in quantity and the limestone pastures would have been far better suited to sheep than to cows.

Although most of the sites in the area are difficult to date and a number were occupied throughout the Roman period, it is highly likely that many of them began earlier. Indeed, in all probability the Roman settlement pattern closely reflected that of the preceding period. It cannot, however, be demonstrated that there were no substantial changes in the economic system consequent upon the Conquest. All that can be safely said at present is that the land supported a considerable population who, by the Roman period at least, were cultivating fields as well as maintaining flocks and herds. Until the large-scale excavation of some of the settlements has been undertaken, further conclusions are impossible.

The general absence of hillforts in the northern Pennines, with the exception of Ingleborough, Yorks., is notable. Presumably the pastoral emphasis of the economy prevented the development of politically cohesive tribes requiring defended foci. The dissected nature of the landscape would also encourage the isolation of smaller groups.

The Magnesian limestone hills provide an environment more congenial to an agrarian-based economy and aerial photography is beginning to show something of the complexity of the ancient landscape with its trackways, linear boundaries and extensive field systems (Riley 1976, 1977, 1978; Chadwick 1999). Two settlement sites of considerable significance have been examined. At Ledston, Yorks., the part of the site excavated produced concentrations of rectangular storage pits, four-post ‘storage’ structures and circular buildings associated with beehive querns and weaving combs, while at Dalton Parlours, Yorks. (Figure 14.5), an agglomeration of ditched enclosures was found, several of them containing circular houses, four-post structures and rectangular storage pits. The radiocarbon dates suggest that the occupation spanned the period from the fourth to second centuries but pottery hints at a continuity of use until the late first century AD. A considerable number of querns and the animal bones recovered reflect a balanced mixed economy. Both Ledston and Dalton Parlours share most of the characteristics of the farming settlements of the south.

Figure 14.3 Castle Hill, Almondbury, Yorks. (source: Varley 1976).

West of the Pennines

The large tract of lowland between the Pennines and the Irish Sea – the Lancashire and Cheshire plain – is not yet well known archaeologically, but around the upland fringes and along the mid- Cheshire ridge there is a scattering of hillforts in use in the Early Iron Age but not, apparently, after the fourth century BC. Across the lowlands a number of enclosures are now coming to light (Matthews 1999, 2002) but published detail is still sparse.

The Tees–Forth region

The settlement pattern of the eastern part of northern Britain, centred upon the Tees–Forth region but extending to the north and south of it, is well known as the result of intensive field- work (Jobey 1962b, 1965, 1966a, 1966b, 1971a, 1971b; RCHM(S) Peeblesshire, Argyll and Roxburghshire; Haselgrove 1982; MacInnes 1982; Ralston, Sabine and Watt 1983), backed up by limited but carefully planned excavation. Most of the known sites now lie in the foothills of the main mountain ranges, on marginal land which has escaped recent ploughing, but aerial photography is showing that occupation extended on to the richer boulder clays of the lowlands, where all surface indications have long since disappeared (Haselgrove 1982). In addition to the settlement data a number of overviews of other aspects of Iron Age culture have been published – on crop regimes (van der Veen 1992), pottery (Evans 1995, Willis 1999) and quernstones (Gwilt and Heslop 1995) – all adding to our understanding of life in the region. Broader discussions offering an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the available database include those by Hingley (1992), Haselgrove (1999), Willis (1999) and Armit (1999).

Figure 14.4 Distribution of settlements in the Wharfedale area of Yorkshire. The broken lines represent geological fault lines with limestone to the north (source: Raistrick 1939).

The earliest first-millennium BC settlements to be identified are the unenclosed groups of circular houses which now survive in upland areas beyond the limits of present-day agriculture and up to about 380 m OD (Gates 1983; Jobey 1985), of which the best known is the settlement at Green Knowe, Peeblesshire. Such radiocarbon dating evidence as there is for unenclosed settlements suggests a span from the mid-second to mid-first millennium, one of the latest being Dryburn Bridge, East Lothian, where the settlement can be shown to post-date a palisaded enclosure, of the type described below, for which a date of c. 750 BC is suggested.

Surveys in the immediate environment of many of the Northumberland sites (Gates 1983) show them to be associated with clearance cairns and field walls, the latter occasionally lapped by minor lynchets caused by ploughing. The pollen evidence provides further support for the view that even the settlements at the highest altitudes were engaged in some agricultural activities, albeit on a limited scale. These questions will be returned to in chapter 16.

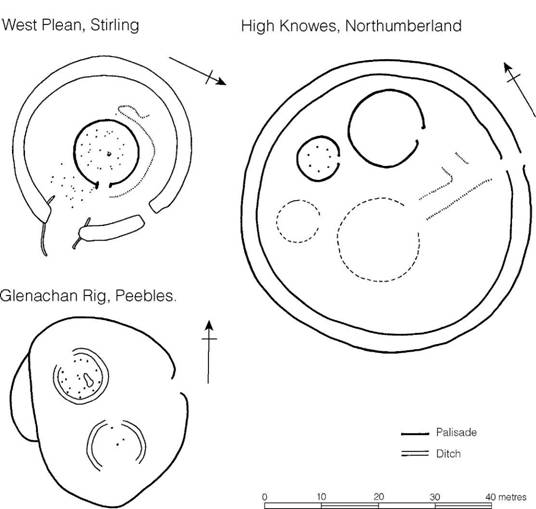

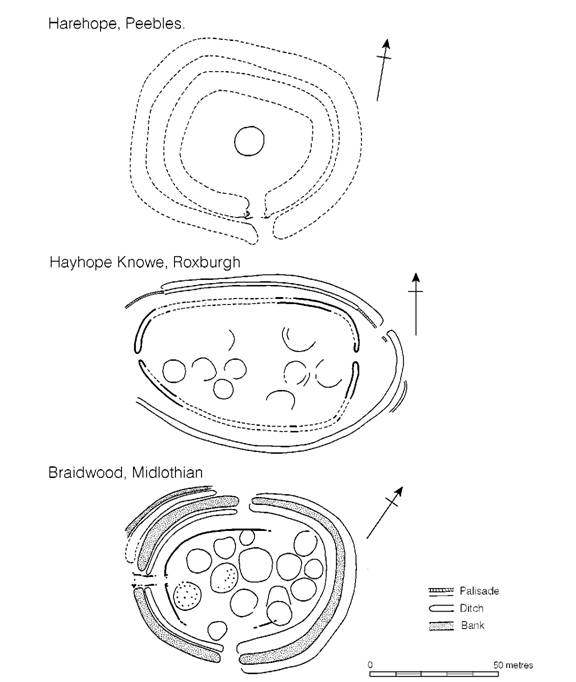

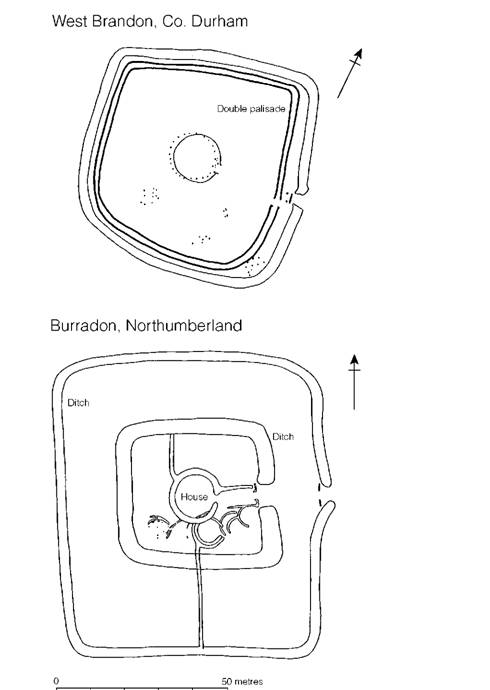

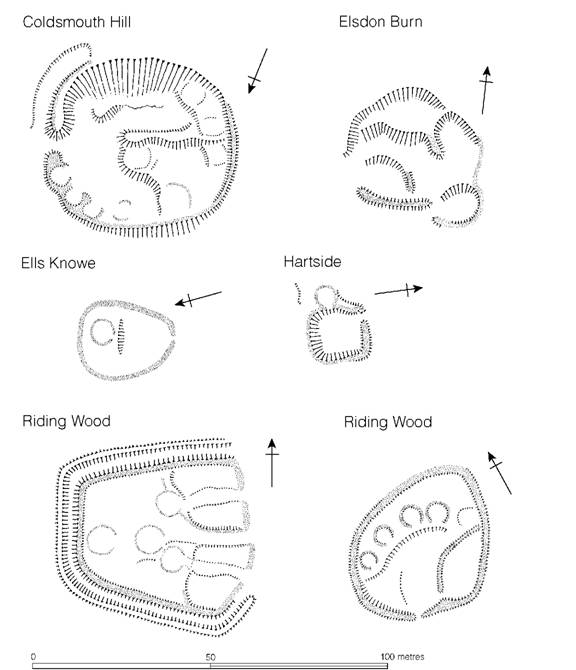

From the eighth century BC onwards, one of the commonest forms of settlement, numerous examples of which are now recorded, is the palisaded enclosure (Figure 14.6): a circular, oval or sub-rectangular area surrounded by a continuous palisade trench in which close-spaced vertical timbers were wedged. A variety of plans is known (Figures 14.7–14.9). At one of the largest of the sites, White Hill, Peebles., two concentric palisades were erected 6.1–15.2 m apart, the inner enclosing an area of 0.7 ha. Hayhope Knowe, Roxburgh. (Figure 14.8), follows much the same arrangement, the only difference being that here the inner palisade was double, while at Castle Hill (Horsburgh), Peebles., both inner and outer palisades were double. These examples were all provided with simple opposed entrances, but others are known with only one entrance. At the thoroughly excavated site of West Brandon, Co. Durham (Figure 14.9), the simple double palisade ended in four large gate-posts in the centre of one side, and at Harehope, Peebles. (Figure 14.8), a single central gate was provided in each of the two periods represented; in the second, however, it was flanked with substantial timber-built towers. Harehope is atypical in another way since the palisades, instead of being set in a rock-cut trench, were bedded in a shallow bank of soil and rubble. The method of construction is not unlike that practised in Late Bronze Age contexts in southern Britain.

Figure 14.5 Dalton Parlours, West Yorkshire (source: Sumpter 1988).

Stylistically the palisaded settlements have parallels among early sites further south which belong to the eighth to fifth centuries. At Dryburn Bridge, E. Lothian, a series of radiocarbon dates suggest a construction date for the palisaded enclosure in the eighth century or even earlier. A radiocarbon date for charcoal from one of the palisade trenches at Huckhoe, Northumberland, indicated a date in the seventh or sixth century while the palisade at Burnswark has been dated to the sixth century. Clearly, then, the northern palisades are of the same broad date as those in the south. Some are, however, later. At Hayknowes Farm, Dumfries and Galloway, a palisaded enclosure dates to the third to first centuries BC while excavation at Tower Knowe, Northumberland, has suggested that these palisaded enclosures could have continued to have been built as late as the first century AD. A further point of similarity to the south is that some of the palisades were later rebuilt as earthwork-enclosed sites. A good example of such a refurbishing can be seen at West Brandon, where a ditch was dug outside the palisades, the rampart without revetment being piled up behind, sealing the original palisade trenches. At Huckhoe both the inner and outer lines of palisade, 15 m apart, were replaced by stone-faced ramparts, while at Castle Hill (Horsburgh) the two palisades were again echoed in later earthworks but enclosed a more restricted area. At Kennel Hall Knowe, Northumberland, the later earthwork enclosed a more considerable area than the earlier palisades.

Figure 14.6 Distribution of settlements defended by palisades (source: Ritchie 1970 with additions).

The sequence, from palisade to earthwork can be shown to be generally secure, though in detail the situation is more complex (Hill 1982b; Armit 1999) and the change can no longer be assumed to represent a narrow chronological horizon. At Huckhoe the earthworks must have been built immediately after the destruction of the palisade by fire in the sixth century, but radiocarbon dates in the fourth century for Brough Law and the fourth to second centuries for Ingram Hill, both in Northumberland, show that not all the earthworks were as early, while at Kennel Hall Knowe radiocarbon dates for houses associated with the early palisades centre on the first century BC and first century AD. Here the earthwork phase is likely to be Roman.

Figure 14.7 Comparative plans of palisaded enclosures (sources: West Plean, Steer 1958; High Knowes, Jobey and Tait 1966; Glenachan Rig, Feachem 1961).

A point worthy of emphasis is that many of the sites, both palisaded or earthwork-enclosed, were provided with multiple lines of defence, commonly though not invariably 15 m or so apart. While there can be no certainty on the matter, it is very tempting to see such an arrangement as the deliberate provision of protected corralling space for livestock, comparable with the multiple- enclosure forts of the south-west. Pastoral activities must have played a significant part in the economy but the general lack of faunal material renders any detailed assessment of the composition of flocks and herds difficult. Some quantification for sites in the Tees–Tyne region, however, showed cattle to predominate (Haselgrove 1982, 80). This is borne out by the assemblage from Thorpe Thewles, Cleveland.

Figure 14.8 Comparative plans of palisaded settlements (sources: Harehope, Feachem 1962; Hayhope Knowe, C.M. Piggott 1951; Braidwood, S. Piggott 1960).

Figure 14.9 Comparative plans of rectangular enclosures (sources: West Brandon, Jobey 1962a; Burradon, Jobey 1970).

Cultivation was by no means neglected, as the four saddle querns from West Brandon and the rotary quern from Harehope show. Huckhoe has also provided evidence of what could be interpreted as a four-post granary, but the storage pits and corn-drying hollows of the south are entirely lacking. However, environmental sampling at Coxhoe and Thorpe Thewles has produced carbonized remains of spelt, six-row hulled barley and probably emmer wheat, establishing the presence of a clear, but unquantifiable, arable component in the subsistence economy (van der Veen 1992).

The size of the settlements varies considerably from homesteads of one house like West Brandon to hamlets or even villages like the sixteen houses of Hayhope Knowe. Unless the house plans actually overlap, however, it is difficult to be sure how many phases of replacement were involved. This problem is clearly demonstrated by the excavation of the native settlement at Hartburn, Northumberland, where no fewer than thirty-six houses were discovered representing a minimum of twelve replacement phases. Quite possibly occupation was continuous from the middle of the first millennium to the second century AD.

While the majority of settlements conform to homestead or hamlet type it is evident that the complex defences of some quite small sites distinguish them as settlements of high status. An example of such a site is Broxmouth hillfort, E. Lothian, substantially excavated in 1977–8. The enclosed area was small, less than 80 m across, but after an open phase there followed five successive phases of enclosure, each incorporating at least one aggrandized entrance. The contrast with the neighbouring settlement at Dryburn Bridge, only 3 km away, where a simple palisaded settlement was replaced by an open settlement, can best be explained as a difference of status. Status may also be reflected in a society’s access to rare commodities. This is to some extent exemplified by the settlement at Thorpe Thewles, Cleveland. In the Middle Iron Age the settlement appears to have conformed to the local norm, with a roundhouse set within a rectangular ditched enclosure. In the later phase (first century BC–first century AD) the enclosure was replaced by a large open settlement of undefined extent which was in receipt of a range of luxury items including gold and silver, imported through the southern trade networks. The potential exists, therefore, to allow settlements in the Tees–Forth region to be ranked, but without a programme of large-scale excavation and a firm chronological framework it is unlikely to be realized.

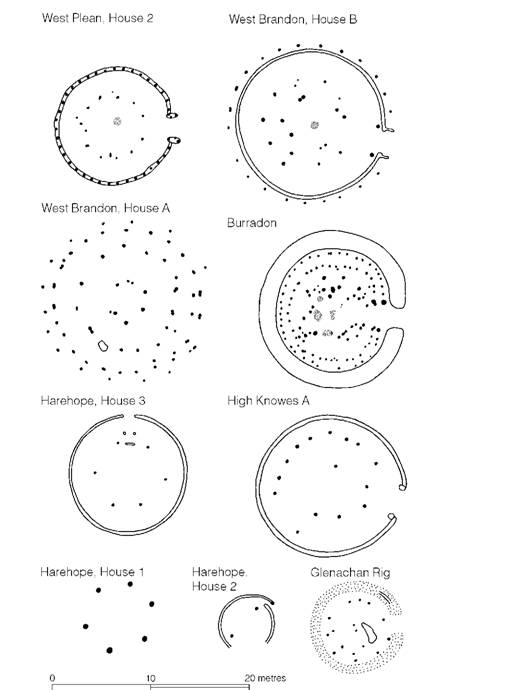

Houses were invariably circular, ranging from about 6 to 15 m in diameter (Figure 14.10). The simplest were merely circular settings of posts like Harehope house 1 and the house which pre-dates the palisades at West Brandon. A slightly more complex arrangement occurs at Gle- nachan Rig, where a central post was provided to support the roof and the lower ends of the rafters were bedded in a shallow trench, thus providing some storage space behind the verticals. The earliest house in the palisaded enclosure at West Brandon is even more elaborate, with a roof taken on three concentric circles of posts, the outermost being 15 m in diameter. Beyond this is a further set of stake-holes, perhaps to tie down the roof-timbers, while the entrance passage seems to have been provided with double doors. In size and sophistication, the house rivals Little Woodbury, Wilts., and Pimperne Down, Dorset.

The earliest house at West Brandon was replaced by a structure of similar size, the outer wall of which was bedded in a continuous trench. Inside, a multiple setting of individual posts would have supported the main weight of the roof, while again an outer setting of stakes was provided, presumably as anchors for the rafters. A closely similar house was found at West Plean in period 2 – similar even to the extent of having the same type of short porch. The period 3 house at Harehope belonged to this general category but in this case it would appear that the outer wall was made of split timbers erected as a continuous wall rather than wattle infilling between individual posts.

Figure 14.10 Types of north British house plans (sources: West Plean, Steer 1958; West Brandon, Jobey 1962a; Burradon, Jobey 1970; Harehope, Feachem 1962; High Knowes, Jobey and Tait 1966; Glenachan Rig, Feachem 1961).

A variety of the circular house, commonly known as the ‘ring ditch’ house, is found only in Scotland. It is characterized by a central area separated usually by a timber ring or partition from a sunken peripheral area which is sometimes paved. Examples have been excavated at Gle- nachan Rig, Harehope, Broxmouth, Dryburn Bridge and Douglasmuir and the type has been widely discussed (Hill 1982a, 12–21; 1984; Reynolds 1982; Reid 1989). No convincing reason has been put forward for the separation of the two zones but the possibility that the type may in some way be associated with the over-wintering of cattle has much to commend it.

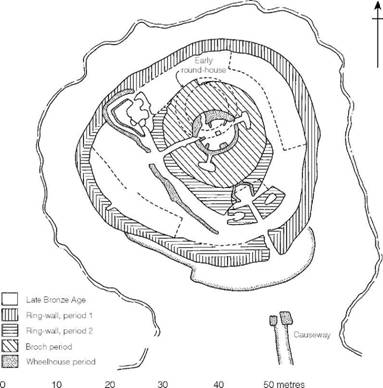

Turning now to the end of the Iron Age, one development, well represented among settlements discovered in Northumberland, is the appearance of stone-walled huts set in enclosures sometimes overlying the defences of hillforts (Figure 14.11). Such settlements are normally so sited as to make use of sheltered slopes, comfort being more important than defensive potential. Some regional differences are evident. In the Cheviot foothills the usual type of enclosure is circular, containing a number of huts fronting on to a sunken yard which is sometimes paved. Further south in Northumberland rectilinear plans prevail, the enclosures containing four or five round huts opening on to a pair of cobbled yards divided by a central pathway leading to the rear of the enclosure. The huts show no significant variation in size or complexity, suggesting little social differentiation, but in some areas larger settlements arise as the result of gradual growth and addition to a basic nucleus. Nucleation of this kind is not, however, common and the normal settlement unit remained throughout more appropriate to the family and the extended family than to more complex social groupings.

Dating evidence, where it exists, shows that many of the sites were occupied during the second century AD – a fact which, together with the rectangularity of the plans, has suggested direct Roman inspiration – but the discovery of a rectangular enclosed homestead at Burradon and others elsewhere in Northumberland (Figure 14.9), dating to the middle of the first millennium BC, shows that little can be based on plan alone. In all probability, enclosures with stone-walled huts developed out of the strong local tradition and may even have come into use before Roman interference in the area. There is often an element of continuity in choice of site between the small defended hillforts and the settlements: on some occasions the settlements actually overlie lengths of the disused defences. In such a case it is possible that a direct continuity of occupation took place. Elsewhere, the proximity of settlements to hillforts could be interpreted as a community moving to a more hospitable site nearby when need for defence was removed.

Another type of settlement, less well known, is the so-called ‘scooped enclosure’: a group of hut platforms terraced into the hillside and enclosed by a bank or wall (Figure 14.11). Dating is at present uncertain but typologically a Late Iron Age or early Roman context would seem to be most likely.

The replacement of palisades with earthworks has given many of the early homesteads and settlements the appearance of hillforts, but not only do most of them not exceed 1.2 ha in overall extent, the siting of many is clearly not defensive. For this reason, there is some uncertainty in the use of the term ‘hillfort’ in Scotland: many of the 1,500 or so recorded (at least three-quarters of them in the Tyne–Forth region) are no more than rampart-enclosed homesteads and settlements. To avoid confusion Feachem (1966) has used the term ‘minor oppidum’ to describe fortifications of a more massive size, 2.4–16.2 ha in extent, sited with an eye to the defensive possibilities of the land. These are far less numerous – some fifteen within the region under discussion. Many of them enclosed massive settlements: more than 500 houses within the 16.2 ha of Eildon Hill North, Roxburgh., and at least 130 within the 5.3 ha of Yeavering Bell, Northumberland (Ridout, Owen and Halpin 1992, 139–43).

Figure 14.11 Settlement sites from Northumberland (source: Jobey 1966a).

These north British sites with their ten to twelve huts per half hectare were three times more densely settled than those of north-west Wales. However, not all the huts were in use at one time and construction may have been spread over many centuries. Excavation of Traprain Law, East Lothian, which at one time reached 16 ha, has shown that here at least occupation began in the Late Bronze Age and may have continued sporadically throughout the Iron Age until extensive reuse in the Roman period; the same complexity of occupation may well be true of the other large ‘oppida’ of the region. This is certainly so at Eildon Hill where the ramparts and earliest hut circles are Late Bronze Age. Thereafter the site seems to have been abandoned until the Roman period. At Dunion, Roxburgh., on the other hand, occupation in the outermost enclosure was under way in the third or second century BC and continued to the first century AD. It is impossible to know without excavation how many of the huts were in use at any one time or what the density of occupation was in the Iron Age compared with the Late Bronze Age and the Roman period. However, it remains possible that by the later part of the Iron Age some of these oppida had developed into nucleated settlements which may have commanded the allegiance of the inhabitants of the surrounding countryside.

The broad stretch of eastern Britain, from the Tabular Hills in the south to the foothills of the Grampian Highlands – a distance of some 450 km – encompasses a number of sub-regions each offering different constraints and opportunities for settlement and survival. Something of the regional patterning can be seen in the distribution patterns of pottery of distinctive fabrics (Evans 1995) and of quernstones quarried from localized outcrops (Gwilt and Heslop 1995). It is also apparent in differences in settlement morphology (MacInnes 1982) but what impresses overall is the general similarity of settlement over the whole region. The norm was the single family unit, though sometimes sites large enough for more than one family are indicated. Where settlements were long-lived, as they very often were, the earlier phases were usually enclosed within a timber palisade while the later showed a preference for boundaries defined by banks and ditches. There were, of course, exceptions to the rule, and some sites, like Broxmouth, by virtue of the impressive size or complexity of their enclosing earthworks, may have become the homesteads of élite lineages. Of hillforts (the ‘minor oppida’) there is little that can usefully be said except that few seem to have been in use after the eighth or seventh century BC or before the first century AD. Together the evidence strongly suggests that the entire region was without centralizing tendencies, yet by the Roman period a number of tribal confederacies are historically attested. Evidently society was structured in such a way that bonds of allegiance allowed communities, scattered over considerable areas, to accept a level of common purpose.

Much has been learned of the economy of the region over the last three decades. It is now widely accepted that agriculture played a significant part in the economy alongside animal husbandry. In the Tees lowlands, spelt became dominant in the second and first centuries BC, but further north emmer remained the most common wheat, though often with barley dominating. Cultivation plots, once so elusive, are now being recognized in the systems of cord rig, which resembles medieval rig and furrow but in miniature. In all probability these fields were hand dug. Palynological work in Scotland has suggested that extensive forest clearance was under way in the third and second centuries BC (Dumayne-Peaty 1998) (see later, p. 442). Thus the north-eastern communities emerge as self-sufficient in providing for their own needs, independent and with few archaeological signs of there being a significant differentiation in status between homesteads.

Western Scotland and the Western and Northern Isles

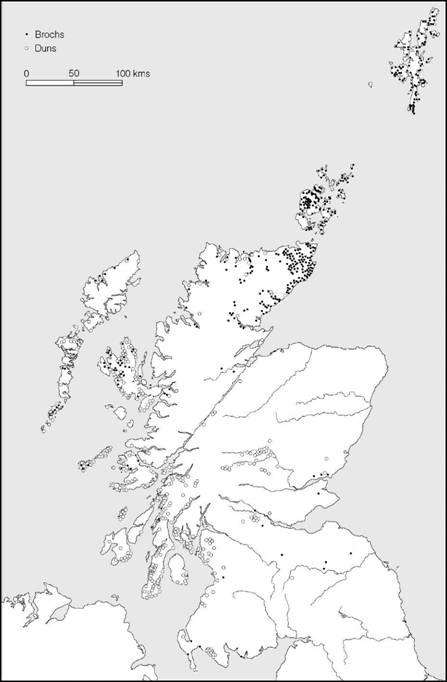

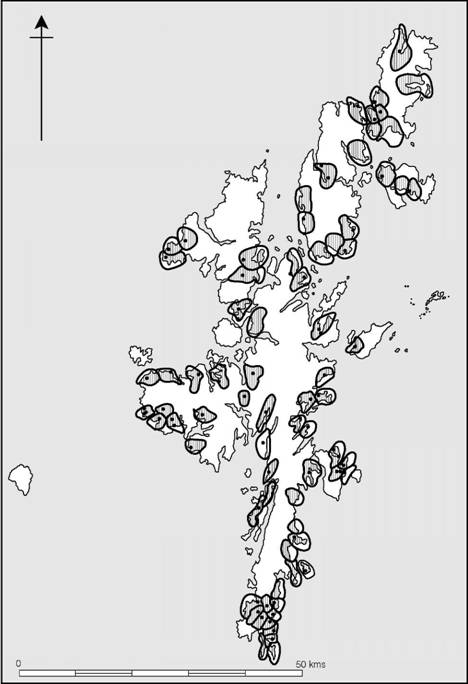

The north-western part of Scotland, together with the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland, still retains one of the best-preserved Iron Age settlement patterns of any part of the British Isles (Barrett 1982; Hingley 1992). The most evident structures are the stone-built brochs and duns, many hundreds of which survive in recognizable form (Figure 14.12). So dramatic are they that they have inspired a considerable literature and many attempts at classification have been offered. Against this background it is surprising how little systematic excavation had been carried out until comparatively recently. A number of sites were examined in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but techniques of recovery were ill-developed and the record is, on the whole, poor. In the post-war period a new phase of study began with the excavation of Jarlshof, Shetland, and there are now twenty or so well-excavated sites providing sequences useful for assessing settlement development. The more significant of these will be considered in the paragraphs to follow.

The terminology used to describe the settlements of the north-west has evolved over the years. Gordon Childe, impressed by the defensive strength of the settlements, referred to them as the ‘castle complex’ (Childe 1935b) while recognizing the variety covered by his generalization. By the 1960s it was conventional to divide the sites into two broad types, brochs and duns, which have complementary though overlapping distributions (Figure 14.12). But each of these broad categories can be further subdivided. As long ago as 1947 Scott argued that the brochs were essentially overgrown roundhouses, and although this view did not prove to be popular at the time, the belief being that the brochs were tower-like structures, it is now accepted that many of the brochs were comparatively low in height and far more like elaborate houses (Fojut 1992; Armit 1990a, 1990b), though a few, such as Mousa on Shetland and Dun Telve, Skye and Lochalsh, grew to exceptional proportions and can reasonably be regarded as towers. MacKie has also introduced the term semi-broch for broch-like structures situated on the edge of a promontory or precipice so that one side of the building can be omitted or represented by a low parapet (MacKie 1965c, 1992). He argued that the type may have been ancestral to circular brochs. The duns are now generally divided into two rather different categories: small, circular, strongly fortified dwellings and larger enclosures protecting smaller houses (Harding 1984; Nieke 1990). These larger enclosures are more akin to small forts and may be placed in the same general category as the promontory forts or cliff castles particularly prevalent in the Northern Isles (Lamb 1980). A version of the promontory fort – the so-called blockhouse – appears only on Shetland. Finally there is the wheelhouse which may be characterized as a circular stone-built structure the interior of which is divided by short radial piers projecting from the wall. Wheel- houses are well represented on the Western Isles and on Shetland but are unknown on Orkney.

In an attempt to clarify the situation Ian Armit has introduced a new terminology (Armit 1990b, 1990c, 1990d, 1992, 2002). He accepts the validity and the distinctive nature of the wheelhouses but has proposed to call all other domestic structures Atlantic roundhouses, incorporating within this category both brochs and duns but excluding the fort-like enclosures which had previously been classified with the duns. The Atlantic roundhouses he divides into two types, simple and complex, the difference being that the complex Atlantic roundhouses employ some or all of a set of architectural traits, including hollow-walled construction, scarcement ledges, intra-mural stairs and guard-cells, which he collectively calls broch architecture. Thus the complex Atlantic roundhouses include galleried duns, brochs and broch towers.

Figure 14.12 Distribution of brochs and duns (source: Rivet 1966).

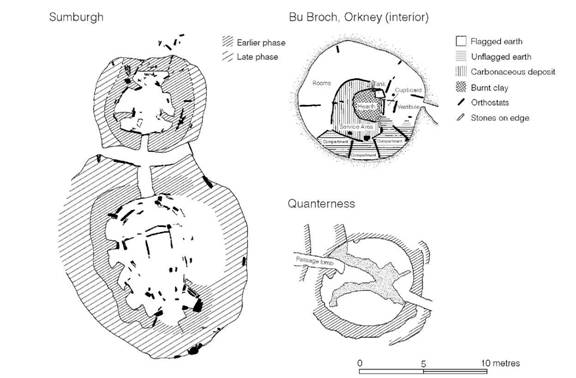

A number of significant excavations undertaken in the last half century or so have provided useful sequences allowing the development of settlement architecture to be studied and local sequences to be established, while the use of radiocarbon dating and an assessment of stratified artefacts are beginning to provide a broad dating framework. Cellular houses of the Late Bronze Age (above, p. 60) begin to be replaced on the Northern Isles by simple Atlantic roundhouses best known on Orkney at Quanterness, Bu (Figure 14.13), Pierowall and Tofts Ness, and on Shetland at Clickhimin. Radiocarbon dating suggests that this process was under way in the seventh century BC and that houses of this kind were being built and occupied throughout the Early Iron Age (600–400 BC). From about 400 BC complex Atlantic roundhouses began to be built, presumably as a development of the indigenous tradition. Examples include Howe, Orkney, and Crosskirk, Caithness, both of which appear to be the focal structures of more extensive settlement complexes protected by an outer enclosure. The appearance of the true broch tower is rather more difficult to date, but since a number of broch towers, like Gurness, dominate sites that were in use before the appearance of the rotary quern in the area it is possible that they could date to as early as 200 BC (Armit 1992). The origin of wheelhouses is also difficult to date. In the Outer Hebrides a fine example of a wheelhouse at Sollas, North Uist, could be shown by radiocarbon dating to have been in use in the first and second centuries AD, and similar dating is indicated on Shetland at Jarlshof and Clickhimin where wheelhouses were built after the brochs had been in use for some time. It is quite possible, however, that wheel- houses developed earlier, in the first century BC or even earlier, evolving from the simple Atlantic roundhouse tradition. The early house at Quanterness, Orkney, dating to c. 700 BC, already shows many of the basic characteristics of the wheelhouse though, it should be noted, wheel- houses do not appear to have been a feature of later Iron Age Orcadian settlement. It is on the Hebrides or Shetland that we might eventually be able to trace a thread of continuity from the simple Atlantic roundhouse to the wheelhouse.

Simple Atlantic roundhouses and early fortifications

Excavations at Bu, Pierowall and Quanterness, all on Orkney, have brought to light well-preserved examples of simple roundhouses belonging to the early stages of the Iron Age (c. 700–400 BC) (Figure 14.13) (Gilmour 2002). Bu Broch with its massive wall 4–5 m thick is of broch-like proportions but lacks the refinements of broch architecture. Access is via a narrow entrance passage which leads through a vestibule into a central area, dominated by a hearth, beyond which peripheral rooms are arranged, some with flagged floors. The Quanterness roundhouse was somewhat smaller and had a less well-defined inner arrangement, and its walls were much less massive. At Pierowall only a small sector of the building was exposed but it had an external diameter of at least 16 m, with walls 3 m thick.

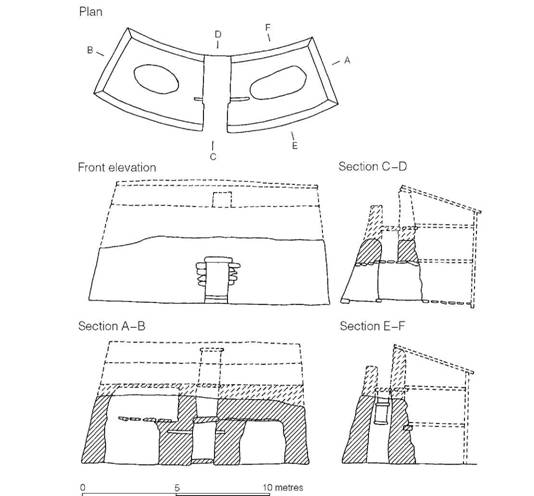

On Shetland the long-inhabited settlement which developed on an island in the loch of Click- himin provides convincing evidence of the place of the simple Atlantic roundhouse within a sequence of occupation (Figure 14.14). The earliest settlement (period I) consisted of an oval- shaped cellular house built entirely of stone, dating to the Late Bronze Age. The building belongs to the same tradition as the cellular structures which lie at the beginning of the settlement sequences at Jarlshof (Figure 3.19) and at Sumburgh (Figure 14.13). This was replaced by a large roundhouse (period II) associated with carinated pottery. Eventually (period III) the house was encircled with a defensive fort wall, inside which lay a blockhouse, to protect the entrance. At this time the accommodation was greatly increased by the construction of timber ranges around the inside of the fort wall, probably standing to a height of two storeys with stalls below and living space above. The blockhouse is a remarkable structure (Figure 14.15). Originally it would have been three storeys high with an attached timber-built range behind. At ground-floor level a central passage was provided in the masonry, leading to the dwelling space behind, while at first-floor level a door gave access between the rooms of the timber range and mural cells constructed within the thickness of the blockhouse masonry; the second floor was probably a wall-walk to provide a vantage point. It seems likely that the blockhouse was intended to have been integral with the main defensive wall, but this was never achieved. In the final pre-broch phase at Clickhimin (period IV), after repair of the outer fort wall and the demolition of the timber ranges, work began on the construction of an inner ring-wall around the island, butting up to the original Iron Age circular hut, which remained in use. The work was, however, unfinished by the time that the broch was constructed.

Figure 14.13 Roundhouses of the Northern Isles (sources: Sumburgh, Downes and Lamb 2000; Bu Broch, Hedges 1987; Quanterness, Renfrew 1979).

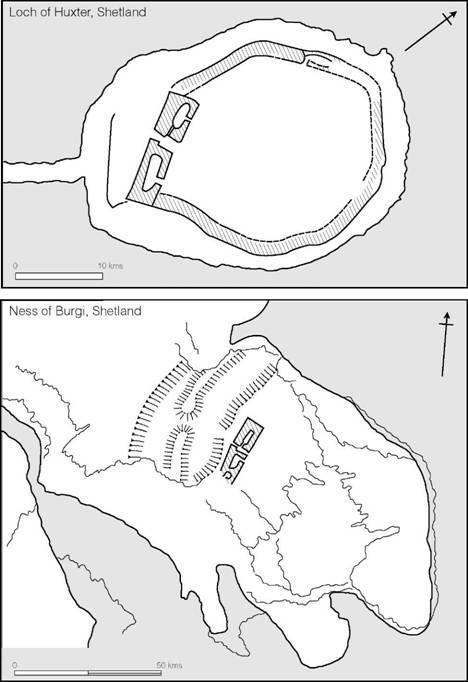

Blockhouses of the kind recorded at Clickhimin are known from three other Shetland sites: at Ness of Burgi and Scatness on the Sumburgh peninsula, and on a small islet in the Loch of Huxter (Figure 14.16). The last has a wall encircling the islet attached to it but the other two are free-standing on promontories protected by banks and ditches (Carter et al. 1995). The four known blockhouses are curious structures. All, in their initial stages, were free-standing, all were sited on promontories or islands, and none makes sense as defence or as settlement. It is tempting to suggest that in their style of architecture – appearing as monumental gateways – and their liminal locations they may have served as foci for rituals associated with the passage between land and sea.

Figure 14.14 Plan of the settlement at Clickhimin, Shetland (source: J.R.C. Hamilton 1968).

The Clickhimin sequence is of great value in that it presents a complete and unbroken development spanning the period from the seventh to the first century before the broch was built. It has been suggested (Hamilton 1968) that the blockhouse architecture should be considered to be immediately ancestral to the development of the brochs, implying that brochs originated somewhere in the Northern Isles – perhaps on Orkney, where the building stone is eminently suitable. The problem, however, is a difficult one and will be considered again below (pp. 334–5).

At Sumburgh, at the southern extremity of Shetland, a complex sequence of building was examined spanning the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages (Figure 14.13). In the Early Iron Age two houses, one large and one small, were in contemporary use, so arranged that they shared a common entrance passage. The interior arrangements owe much to the cellular Late Bronze Age tradition but the associated pottery indicates an Early Iron Age date.

Elsewhere in north and west Scotland positive evidence of early occupation is scarce, but survey work has shown that hut circles are not uncommon and in Sutherland alone there are estimated to be some 2,000 still surviving. One group, at Kilphedir, has been thoroughly examined. Here, two phases of occupation are represented, the first, dated by a single radiocarbon assessment to the fifth century BC, consisted of five circular huts with stone outer walls and with roofs supported on settings of internal vertical timbers. Around them it would seem that the land had been cleared for limited agricultural use, leaving a scatter of clearance cairns. The second phase of occupation was represented by a single, more massively built, hut, the walls of which had been extended on either side of the entrance to create a narrow entrance passage 3 m long. In plan the structure was not unlike a primitive form of broch. This phase was dated by radiocarbon to the second century BC and it was probably in this period that a group of irregular fields lined with boulders were laid out.

Figure 14.15 The blockhouse at Clickhimin, Shetland (source: J.R.C. Hamilton 1968).

A survey of similar settlements in the vicinity has shown that most are found between the 60 and 120 m contours. It is probable that the land below this, in the river valleys, was densely wooded, while above, the exposed position and poor soils would have been too inhospitable for settlement. The Kilphedir evidence is interesting in that it suggests the sporadic rather than continuous occupation of marginal land.

Figure 14.16 Comparative blockhouses on Shetland (source: J.R.C. Hamilton 1968).

The early settlements of the west coast and Western Isles are less well known, but at Dun Mor Vaul on Tiree (Argyll.) a pre-broch midden of the fifth to third centuries has been examined, and at Dun Lagaidh near Ullapool a vitrified fort with radiocarbon dates of the sixth to fifth centuries BC has been shown to pre-date a broch. There are however no known examples of cellular houses of the Late Bronze Age on the Western Isles, though roundhouses of the Late Bronze or Early Iron Age have been identified (Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999, 364).

Complex Atlantic roundhouses: brochs and duns

Brochs and duns are a common feature of the Iron Age landscape of the north and west of Scotland (Figure 14.13).

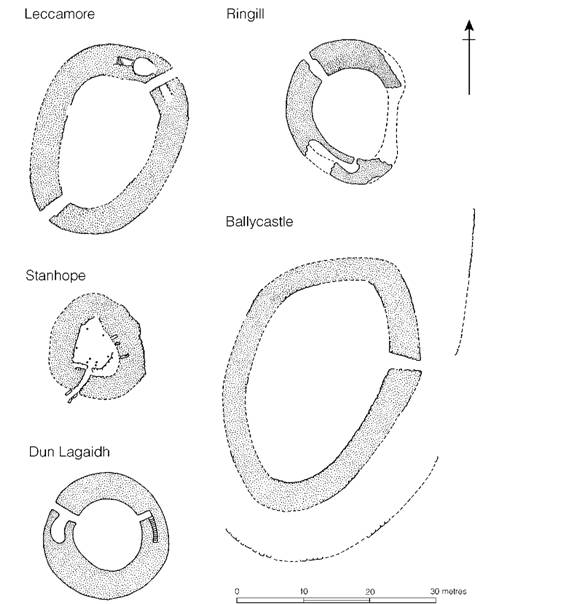

Duns are essentially dry-stone walled enclosures seldom exceeding 370 square metres in internal area (Figure 14.17). The walls, originally about 3 m high, were normally solid but some were provided with mural galleries or simple mural cells. According to the definition proposed by Armit, those with sophisticated architectural features like hollow-walled construction, scarce- ment ledges, intra-mural stairs and guard-cells belong to the category of complex Atlantic roundhouses. In the majority of the unexcavated examples, however, it is impossible to tell if these features are present or not.

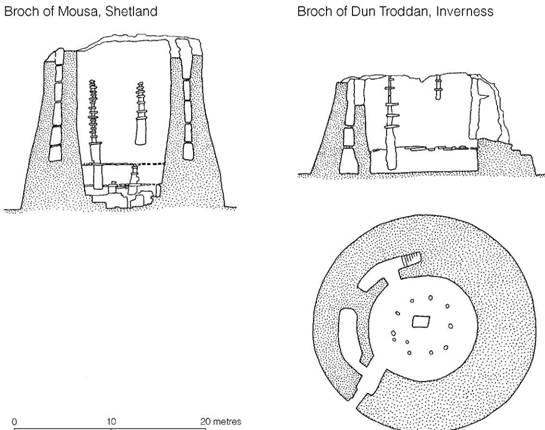

Brochs, also classed as Atlantic roundhouses, were generally taller and more regular in plan, with a few rising to 9 m or more in height, and are characterized by the cellular nature of their wall structure, which consisted of two concentric skins about 1 m apart, held together by rows of stone lintels inserted every 1.5 or 1.8 m in vertical intervals and bonded into both walls (Figure 14.18). This arrangement resulted in the creation of superimposed mural galleries interlinked by stone staircases. The outer walls are always built solid, with no openings save the single ground-floor entrance, but in some examples the inner wall-face is broken by vertical openings divided by horizontal lintels placed at intervals. The main entrance is always a long narrow passage passing through both walls, frequently with a cell or guard-chamber opening off one side of the passage (Martlew 1983).

The inner wall-face was usually provided with at least one ledge or scarcement 1.5 m or so above floor level. This, together with settings of posts within the broch, gives some hint of the treatment of the upper part of the structure. One view is that the scarcement and posts supported a gallery (MacKie 1965c, 104–5) but it is equally possible that a complete upper floor was provided at this level. Additional ledges may have supported further floors, with the uppermost ledge taking the eaves of a roof. In the majority of cases, however, there may have been no upper floors, the scarcement serving for the roof.

The excavation of the buildings of Bu and Howe and the reconsideration of Gurness, all on Orkney, leave little doubt that in their original forms the structures were designed to house single family units. The common arrangement was to divide the interior into a central communal space, surrounded by a peripheral zone subdivided into a series of small cells (Figure 14.19). The central zone contained the hearth and boiling tank. The peripheral zone was probably used for storage and as sleeping compartments. Such an internal arrangement is closely comparable to that of the wheelhouses and to certain of the crannogs (e.g. Milton Loch). The concept of the central living area with peripheral sleeping and storage space can also be postulated for the larger timber houses of the Forth–Tees region and of parts of southern England. In a few examples, e.g. Gurness and Burrian, the interiors were later rearranged in a manner which suggests occupation by more than one family group (Hedges 1985; Reid 1989, 14–15). This may be a reflection of social changes consequent upon contact with the Roman world.

Figure 14.17 Plans of Scottish duns (sources: Stanhope, Peebles., MacLaren 1962; Ringill, Skye, Young 1964; Dun Lagaidh, Ross and Cromarty, MacKie 1968; Leccamore and Ballycastle, Argyll., RCHM(S) Argyll.).

Figure 14.18 Brochs (source: Mousa and Dun Troddan, Curle 1927).

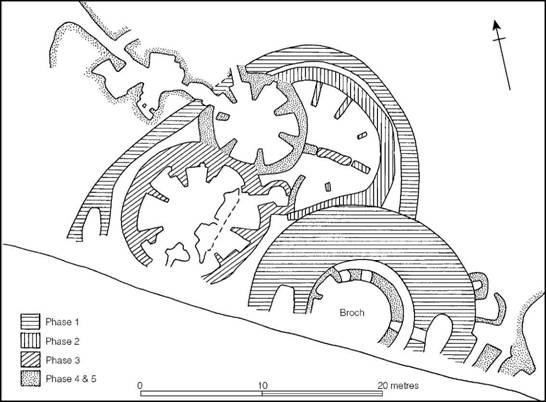

Some brochs form the central element of considerable settlements. The best known of these is Gurness on Orkney (Figures 14.19 and 14.20) where fourteen conjoined buildings cluster around the broch, all lying within the protection of a double-walled enclosure. Similar settlements are found at Howe, Midhouse and Lingro. In the case of Gurness and Howe there is evidence that the external settlements were broadly contemporary with the main occupation of their broch. In these instances we are clearly dealing with large social groupings, the extra broch settlement presumably housing the dependants of the broch owner. A consideration of routes of access through the settlement to the broch supports the view that in these complexes the brochs would have housed the élite (Foster 1989).

Mention of the defences around the brochs raises the difficult question of the promontory fortifications which occur around the coasts of Orkney, Shetland and Caithness (Lamb 1980). While a number are evidently associated with brochs, others are not. Only in one case, Crosskirk, Caithness, is it possible to show that the promontory fort pre-dates a broch. In the general absence of dating evidence elsewhere, all that can be said is that some of these structures may be of Iron Age date.

Figure 14.19 Brochs with adjacent settlements (sources: Gurness, Hedges 1987; Howe, Carter, Haigh, Neil and Smith 1984).

Figure 14.20 The broch of Gurness, Orkney (photograph: Crown Copyright reserved).

Regional varieties of brochs have been defined (MacKie 1965c, 105–10), but the details cannot be examined here except to say that those of Caithness, Sutherland and Orkney tend to be more sophisticated in structure. Another difference is one of siting: while those in the Western Isles are usually built in isolation, the northern group more often stand in fortified enclosures of masonry or earth-and-rubble construction.

The origin of the brochs has been a subject of much debate. The excavation of Bu with its early construction date of c. 600 BC is of some significance to the debate because, while Bu does not possess the refinements of classic broch architecture, its basic form and unusually thick walls suggest that it is a direct ancestor of the more complex broch structures. Among the other thoroughly excavated sites, at the broch of Crosskirk, Caithness, radiocarbon dates suggest a construction date of about 200 BC, but the broch continued in use well into the second century AD. At Howe, Orkney, a roundhouse of uncertain form dating to the fourth to third centuries BC was replaced by an early broch which may have been contemporary with Crosskirk, if not earlier. The broch was later rebuilt in the first century AD at which time a settlement developed around the structure. Occupation continued into the fourth century AD. Dun Ardtreck, a semi-broch on Skye, produced a second-century BC assessment for charcoal from the rubble foundations, while from Dun Mor Vaul, on Tiree, dates of the first century AD for a primary floor level and the second to third centuries AD for rubble which accumulated in the first wall gallery indicate a late first-century BC or early first-century AD construction date. A number of brochs have also produced artefact assemblages showing that occupation continued throughout the first and second centuries AD. Further south, at Leckie, Stirlingshire, the broch was not built until the late first century AD.

The available evidence therefore suggests that the main period of use of the brochs was from the second century BC to the second century AD but the Bu radiocarbon dates would allow that the tradition of broch building began much earlier, on Orkney at least (Hedges and Bell 1980b). The radiocarbon dating, together with an assessment of the associated material culture, suggests that brochs, with all their architectural refinements, may have begun around 400 BC (Armit 1992).

The origin of the brochs has been a matter of some dispute but it is now generally agreed that they developed somewhere in the Atlantic province. One suggestion is that they originated in the Caithness–Orkney region, in the area of their greatest concentration (Childe 1935b, 204; Hamilton 1962, 82); another is that they arose in the west, possibly on Skye, where there is a considerable variety of stone structures, including a concentration of semi-brochs which might be thought to be ancestral to the true brochs (MacKie 1965c, 124–6). In support of this latter view, it has been argued that the broch was more appropriate to the defence of the small pockets of farmland typical of the western Highlands and Islands and is strictly alien to the more open countryside of Caithness and Sutherland. The early precursor at Bu and the early dates of Crosskirk and Howe would favour an origin in the Caithness–Orkney region. Added support for a northern origin is also provided by Caufield’s study of querns (1980), which shows that a significant number of northern brochs had the early type of saddle quern in primary layers whereas the western brochs have produced only the later rotary type.

Several excavations should be mentioned because of the light they throw on the relative position of brochs in the structural development of the individual sites. In each case there is clear proof of some degree of continuity of occupation. At Dun Mor Vaul the broch was shown to have been built on a site already occupied for several hundred years, but at Dun Lagaidh, Wester Ross, the later structure was built over part of a vitrified fort for which a sixth-century radiocarbon date is available, suggesting a period of abandonment between periods of occupation. At Dun Vulan, on South Uist, the broch was built, probably in the second or first century BC, on a site that had already been occupied in the Late Bronze Age, and continued to be used until the eighth century AD. At Crosskirk, Caithness, the broch was erected inside an already existing promontory fort while at Howe, on Orkney, a long sequence of houses existed before the broch was built to replace them. Clickhimin, Shetland, provides the most complete sequence of fortification at present available; the broch was built late in the history of the site but the presence of the earlier blockhouse, which embodies several of the constructional techniques of the broch- builders, evidently represents a stage of construction towards the beginning of the complex sequence which must lie behind the eventual emergence of the fully fledged broch.

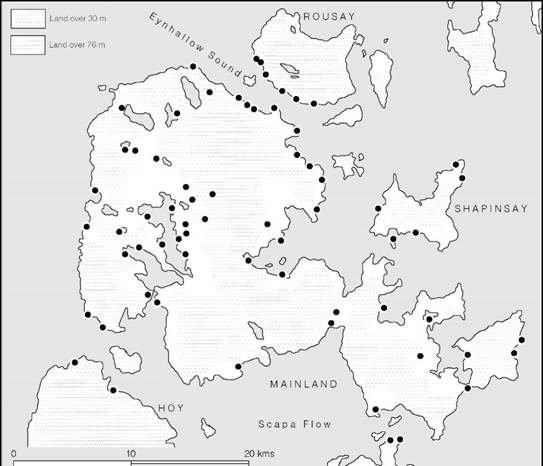

Many brochs are sited close to the sea, and evidently depended to a considerable extent on seafood. On Orkney, for example, brochs are found regularly spaced along the shores, particularly of the more sheltered waters, like Eynhallow Sound between Mainland and Rousay (Figure 14.21). Each was sited so that its resource potential would have included upland sheep grazing, a length of coastal shelf suitable for crop growing, the shore zone itself for shellfish collecting, and the sea, providing a range of possible food sources. Even the inland brochs on Orkney show a distinct preference for siting near lochs. Evidently fish must have played a significant part in the economy. On Skye, too, the brochs and duns favoured a coastal location but clustered on areas of good arable and pasture land (MacSween 1985), while on South Uist the brochs opt for the exposed west coast, choosing sites on the interface between the moorland to the east and the fertile machair and blacklands to the west, with the ocean beyond (Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999, 10–12). A detailed survey of the brochs on Shetland (Fojut 1982b) has shown a similar preference for siting brochs close to the sea but within easy reach of good-quality farming land (Figure 14.22). The survey has further suggested that the majority of the broch territories were self-sufficient but there may have been some localized redistribution of consumer goods between neighbours. An even more interesting conclusion was that, in spite of the considerable density of settlements, the population was far below the holding capacity of their island territory. The desire for fortification was not therefore occasioned by stress brought about by uncomfortably high population levels.

Figure 14.21 The siting of brochs on Orkney (source: RCHM(S) Orkney and Shetland).

Wheelhouses

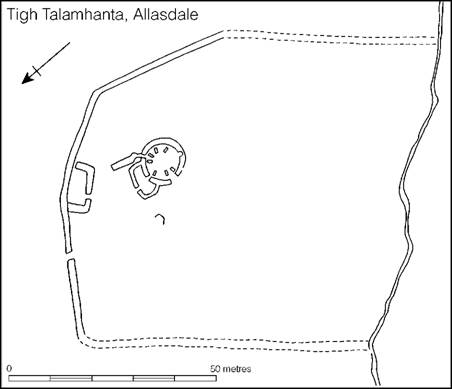

The wheelhouse represents a somewhat different type of structure (Crawford 2002). They are found in the same region as the brochs, except that no wheelhouses have been identified on Orkney, and are broadly contemporary with them. A wheelhouse is a circular stone-built structure, the interior of which is divided by short radial stone piers projecting from the wall but leaving the interior clear. The piers presumably supported the roof of wood and turf in much the same way as internal settings of vertical posts would have done in the timber-built houses of the south. In some examples, known as aisled wheelhouses, the piers are free-standing but are joined to the outer wall by lintels.

Figure 14.22 The brochs of Shetland indicating their possible economic territories (source: Fojut 1982b).

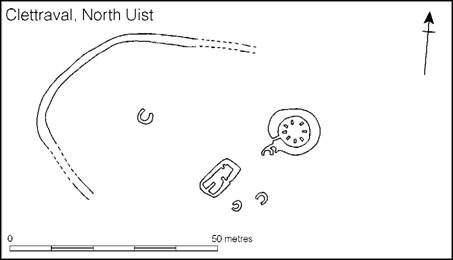

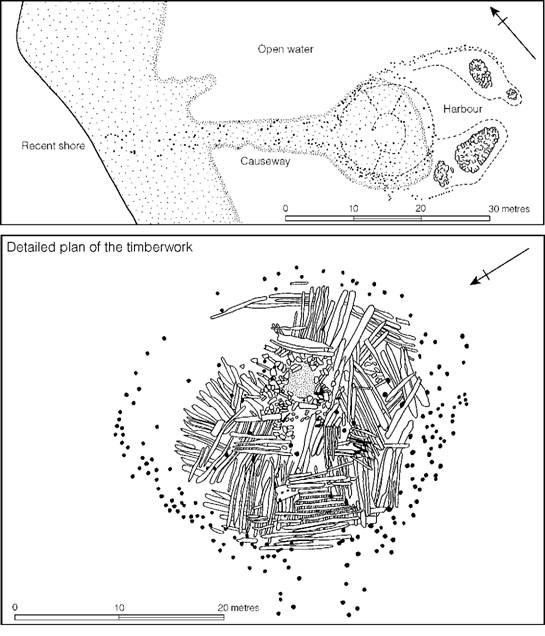

Some wheelhouses, like Tigh Talamhanta (Allasdale) and Clettraval in the Hebrides (Figures 14.26 and 14.27), were built as free-standing houses surrounded by a farmyard enclosure containing working areas as well as subsidiary structures like byres or barns. Others, like Sollas, North Uist, were embedded in sand dunes. At Jarlshof, Shetland, on the other hand, the first aisled wheelhouse was built into the yard attached to the broch with a byre close by (Figures 14.23–14.25). This building is of particular interest because in its original stage the roof was supported on vertical timbers which were only later replaced by free-standing stone piers. Later still the original aisled wheelhouse was dismantled and replaced by a conjoined pair of wheel- houses, superbly built with radial piers corbelled out at the top to roof the individual bays. Jarlshof, then, appears to demonstrate the entire sequence of wheelhouse development. Elsewhere on Shetland, as for example at Clickhimin, most of the wheelhouses were found to be inserted into brochs. This same sequence is evident at the spectacularly well-preserved site of Old Scatness (Figure 14.28), where the broch, dated to within the period 400–200 BC, forms the nucleus of a settlement later dominated by wheelhouses.

While there is some evidence to suggest that elements of wheelhouse architecture were developing on Shetland before the brochs, possibly in the third and second centuries BC, and may well derive from simple circular houses of the type found at Sumburgh, the major occurrence of wheelhouses dates to after the brochs had begun to go out of use as defended structures. The range of stratified Roman imports suggests a first- to third-century AD date and in the Outer Hebrides houses of this type can be shown to span the period from the first to fourth centuries AD. At Old Scatness radiocarbon dates show that wheelhouses remained in use into the ninth century AD.

The economy of the north and west was largely self-sufficient: sheep and cattle were kept, deer were hunted, cereals were grown, while the sea provided seals, whales, fish, shellfish and sea- birds. Throughout the period, tools tended to be made in local materials like bone, slate and quartz, while utensils were manufactured in pottery, steatite and presumably leather. Apart from a restricted range of bronze and iron tools and ornaments, metal was never common. It seems, therefore, that for much of the early part of the Iron Age, communities lived peacefully in open settlements but gradually defences multiplied, giving rise to a densely fortified landscape in which almost every homestead was defended. Such a process may well have developed in parallel with the increased emphasis on defence apparent in most other parts of the country. There is no need to introduce the idea of an alien breed of ‘castle-builders’ to explain a process which in all probability was the result of widespread pressures created by internal social development. Over much of the western area the land was broken into isolated fertile pockets by natural barriers such as mountains and deep inlets. Inevitably, in such conditions, communities tended to remain isolated and settlements failed to nucleate.

Some time in the third century BC or a little earlier a specialized type of fortified house – the broch – perfectly adapted to the requirements of society and its environment became the dominant type. It is hardly surprising that it spread (possibly at the instigation of expert builders) over the whole of the Atlantic province, even into areas like Caithness and Sutherland, where the more gentle undulating land might be thought to be less suitable for such a specialized form of fortification. Brochs continued to dominate the landscape into at least the second century AD, but in the more peaceful conditions which then arose they ceased to be built and were superseded (and sometimes physically replaced) by wheelhouses, which represented the resurgence of the indigenous house type, deeply rooted in the native building traditions of the area.

Figure 14.23 The settlement at Jarlshof, Shetland, beginning with the construction of the broch (source: J.R.C. Hamilton 1956).

The massive nature of the various types of complex roundhouse and the longevity of most of the sites imply a degree of stability in landholding and the willingness to invest effort in creating and maintaining structures that dominate the landscape. This has led to debates focusing on the social status of the inhabitants and has raised questions of whether a peasant class, archaeologi- cally largely invisible, existed scattered in the landscape between the more massive roundhouses. In the Outer Hebrides, where the settlements have been extensively studied, Armit (2002) has argued that different patterns can be traced. On North Uist and Barra it would seem that the houses were occupied by a variety of social units from élites to tenant farmers, whereas on South Uist, where the number of large roundhouses is many fewer, it could be argued that the land- holding system was differently organized, with lower-status households unable, or unwilling, to invest in massive structures. Whatever the explanation is, differences of this kind are a salutary reminder that social patterns probably varied considerably from one area to another. At best the archaeological evidence merely allows us to glimpse these differences.

Throughout the period under discussion the communities of the Atlantic province remained dependent on the sea as a means of communication as well as for food gathering and protection. While the sea linked the far-flung parts of this north-western province together, it seems to have isolated it from the rest of the country.

Figure 14.24 Jarlshof, Shetland: the aisled roundhouse and wheelhouse (photograph: Crown Copyright reserved).

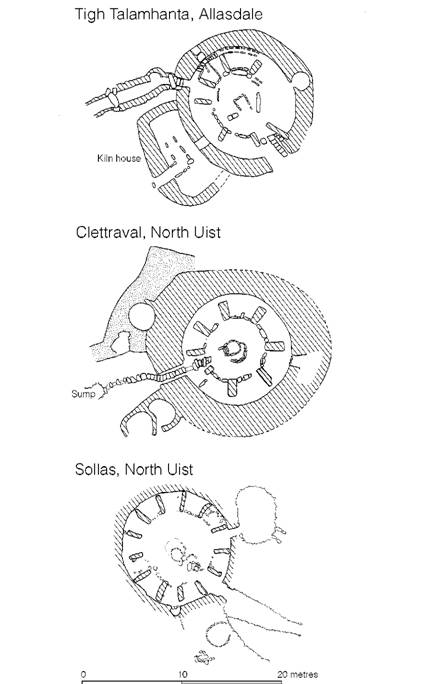

Crannogs and island duns

A specialized type of settlement, known as the crannog, has been identified in many parts of Scotland and particularly in the west of the country (Dixon 1982; Morrison 1985; Henderson 1998; Hale 2000; Harding 2000a). Crannogs were usually built at the edge of lochs and consisted of artificial islands composed of layers of brushwood and rubble sometimes revetted around the edges with vertical piles. In some cases they were surfaced with logs of oak. Upon these artificial platforms stood single buildings constructed either of timber or of stone, the whole structure being joined by a causeway to the shore.

Among the many hundreds of sites known a few have been dated, showing a spread of occupation ranging from the Late Bronze Age to the Middle Ages but with a significant concentration in the Iron Age (Henderson 1998). One of the best known of the crannogs is on Milton Loch, Kirkcudbright., where the artificial island and its associated jetty and small harbour were totally excavated (Figure 14.29). The platform was largely occupied by a large circular timber-built house 12.8 m in diameter, divided internally into a series of rooms. The building was surrounded by a narrow platform to provide access from the causeway to the harbour facing on to deep water behind. Radiocarbon assessments for an ard found during excavation and for one of the piles of the crannog indicate a date in the fifth century BC.

Figure 14.25 Jarlshof, Shetland: the interior of the wheelhouse (photograph: Crown Copyright reserved).

Crannogs are best seen as a specialized type of homestead built, possibly for defensive purposes, offshore from a lake edge. In size they are comparable to their land-based equivalent, the dun, as Morrison was able to demonstrate by comparing the crannogs and the duns on Loch Aire (Morrison 1985, figure 4.6).

A variant of the crannog is the ‘island dun’ which, as the name implies, involves the use of an offshore island as the location for a dun or a broch. Two thoroughly explored examples of this type are known from the island of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, one at Loch Bharabhat, Cnip, the other at Loch na Beirgh at Riof. In both cases complex Atlantic roundhouses occupy small islands 20–30 m from the loch shore, joined to the mainland by a causeway. In these examples the entrances to the houses are on the opposite side to the causeway and face outwards to open water. In neither case can precise dates be assigned to the construction of the houses but evidence suggests that they were built in the second half of the first millennium BC.

Figure 14.26 Farmsteads in north-west Britain (sources: Clettraval, Scott 1948; Tigh Talamhanta, Young 1955).

Figure 14.27 Wheelhouses (sources: Clettraval, Scott 1948; Tigh Talamhanta, Young 1955; Sollas, E. Campbell 1992).

Figure 14.28 Excavation in progress at Old Scatness, Shetland in 2003. The central broch forms the focus of a long-lived settlement later dominated by wheelhouses (photograph: Steve Dorrell).

While it is conventional to believe that the choice of islands or artificial crannogs as sites for houses is the result of a desire for greater defensive capability, it remains a possibility that other factors may have been at work. Islands might be perceived to be liminal places and as such to endow supernatural power and protection. Similar beliefs might have lain behind the siting of brochs or other settlements on exposed promontories girded by the seas. These are issues deserving further attention.

Summary

From the above survey it will be apparent that the communities living in the north and west of Britain differed in many ways from those of the central and north-eastern regions, not least in their skilled use of stone to create houses impressive in their size and strength. In each of these broad regions there are distinctive sub-regions each with their own styles of building and social arrangements. In most areas it would seem that the single family farmstead was the norm, there being little attempt at creating larger agglomerations of people, but in some regions, for example on Orkney and in eastern Scotland, villages are known, and in the eastern Scottish region a scattering of hillforts suggests even more complex social arrangements able to wield the coercive power required to build and maintain the forts. Thus across the north we are looking at a variety of social systems in operation, conditioned, to a large extent, by the opportunities and constraints offered by the differing landscapes.

Figure 14.29 Milton Loch Crannog, Dumfries and Galloway Region (source: C.M. Piggott 1955).

In all regions settlements show change with time. The eighth to seventh centuries represent a horizon of transition noticeable in many regions with the emergence of large dominant circular houses. Later, in the fourth century, there is another widespread change, with settlements becoming more complex and in places enclosing earthworks being built to replace slighter boundaries. It was at about this time that more settlements were built and land was cleared for the first time, suggesting an expansion in population. Further widespread changes in the first century AD may, at least in part, have been caused by the proximity or the actual presence of the Roman army.

Since the 1970s there has been a dramatic enhancement in our knowledge of the Iron Age settlement of central and northern Britain. Although material-poor when compared with the south, the settlement archaeology is unusually rich not least because of the use of stone which, in the north-western region, provides a wealth of structural information, better preserved and more varied in its detail than any other region of Britain.

The way forward must now be to focus on thorough regional surveys linked to a programme of excavation and the systematic study of data, especially material culture, derived from earlier work. Already projects in the Outer Hebrides (Parker Pearson and Sharples 1998), Dumfriesshire (Halliday 2002) and Caithness (Heald and Jackson 2001) are making major advances in our understanding of the complexity of Iron Age settlement in its landscape setting. Through this approach the social dynamics of the disparate communities will begin to come into focus.