Imp. Caesar Divi f. Augustus VII M. Agrippa L. f. III

In January, Imp. Caesar’s consulship was renewed for the seventh time, Agrippa’s for the third.1 Caesar now faced a difficult and consequential decision. He had won the civil war and was the commander-in-chief of the majority of the armed forces. If the Roman world was at peace (or at least no longer consumed by a worldwide conflict) and there were no existential threats to its security, his mission had been accomplished. Should not Caesar now renounce his military command and restore full control of the army to the Roman People, as he had their laws and rights?2 The stakes were high, both to him personally and to the Res Publica, but he was above all a practical politician. He and his close advisers had thought long and deeply about the matter, and had reached an agreement on a plan. On 13 January, it was presented to the Senate. That day Imp. Caesar read from a prepared statement.3 To the great surprise of many of those present in the Curia Iulia, Caesar announced his resignation from the Senate.4 His supporters, who had been told in advance, responded with rehearsed pleas for him to stay on.5 The members not in the know were suddenly uncertain about what to do. No one wanted to see a return of conditions that could lead to another civil war.6 Caesar’s supporters now executed their plan. As an inducement to retain his service, several senators moved to offer him imperium proconsulare (proconsular military power) over Rome’s provinces, save for the homeland of Italy, giving him what was in effect his own personal super provincia.7 Caesar accepted. It was tantamount to a coup d’état, but through careful stage-management there had been no violence.8 To ensure his own blood would not be spilled in the days following, Caesar’s very first act was to secure a decree giving the men who would serve as his bodyguard double what was paid to the regular soldiers.9

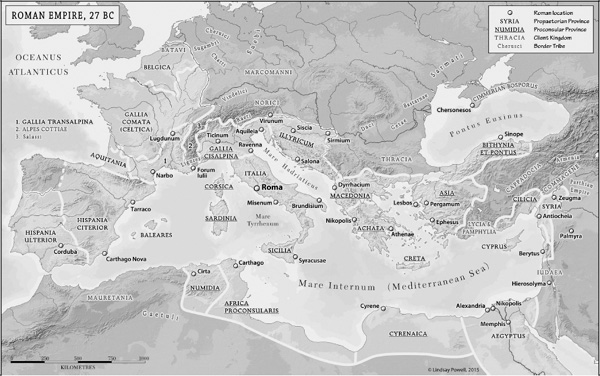

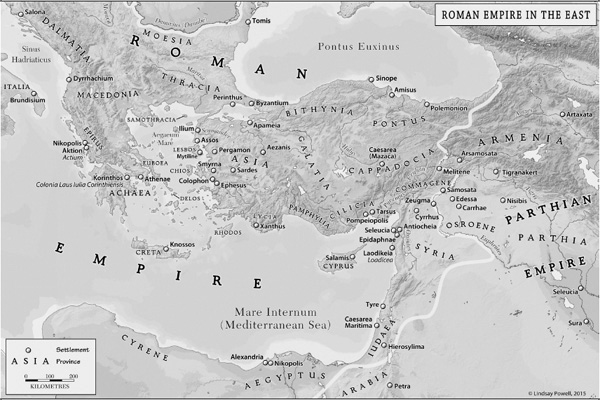

Imp. Caesar had a more nuanced plan for the management of the world ‘under the sovereignty of the Roman People’, as he called it.10 He revealed his idea when the Senate reconvened on 16 January. The empire was to be divided into proconsular and propraetorian territories, which Strabo calls respectively ‘Provinces of the People’ and ‘Provinces of Caesar’.11 Strabo, a contemporary who lived through the reforms, explains that Caesar kept:

to himself all parts that had need of a military guard (that is, the part that was barbarian and in the neighbourhood of tribes not yet subdued, or lands that were sterile and difficult to bring under cultivation, so that, being unprovided with everything else, but well provided with strongholds, they would try to throw off the bridle and refuse obedience), and to the Roman people all the rest, in so far as it was peaceable and easy to rule without arms.12

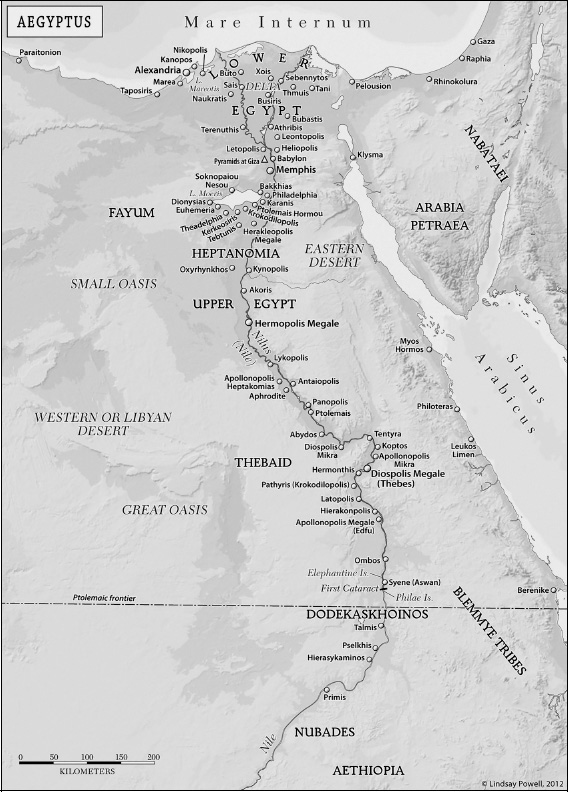

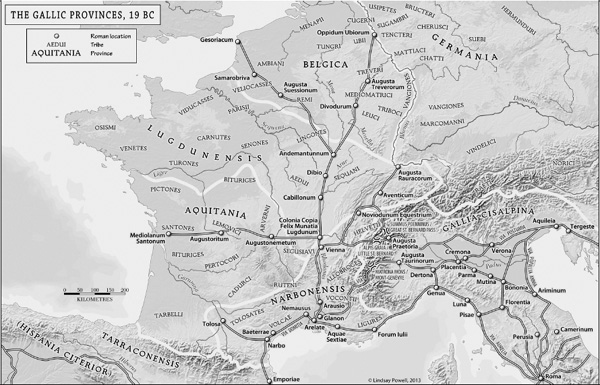

The Senate would retain control of the mainly prosperous territories around the Mediterranean Sea, those being Africa, Numidia, Asia, Greece with Epirus, Illyricium and Macedonia, Sicily, Crete and the Cyrenaica portion of Libya, Bithynia and Pontus which adjoined it, Sardinia and Hispania Ulterior (map 3).13 In keeping with the traditions of the Res Publica – that he was so keen to present as ‘restored’ – the governors of these provinces would be proconsuls, picked annually by lot by the Senate, as they had for centuries. The crucial innovation was the partnership struck between himself and the Senate. By Lex de Imperio for a period of ten years, Imp. Caesar agreed to take sole responsibility for the propraetorian provinces.14 In his provincia he now had direct control of Hispania Citerior, the three Gallic provinces of Aquitania, Gallia Comata (also known as Celtica) and Belgica, Narbonensis, Coele-Syria, Syria, Cilicia, Cyprus and newly acquired Aegyptus (fig. 2).15 Pacification continued to be the priority in these regions. The majority of the legions – twenty-two of the twenty-eight – and the auxiliary units were stationed in these territories, effectively giving Imp. Caesar command of the army (exercitus).16 It was not by coincidence. He had already made the crucial decisions about legionary deployments in 30 BCE, very likely with this long-range goal of his control of them in mind.17

Crucially, Imp. Caesar was granted the right in law to appoint the men to run them. These men were his hand-picked legates, each one deputized to act in his name and serve him for a period of three years.18 They were selected from among the ex-consuls, ex-praetors or ex-quaestors, or one of the positions between praetor and quaestor.19 Their official title, legati Augusti pro praetore, indicated they were subordinate to Imp. Caesar (operating under his auspices and deriving their imperium from him) and they could not claim the glory or spoils they won in carrying out their duties.20 (These would accrue to Caesar.) Moreover, the commander-in-chief could take over at any time or appoint any of his chosen friends or family to do so. Dio reports:

The following regulations were laid down for them all alike: they were not to raise levies of soldiers or to exact money beyond the amount appointed, unless the Senate should so vote or the emperor so order; and when their successors arrived, they were to leave the province at once, and not to delay on the return journey, but to get back within three months.21

His legati were required to wear the panoply of a military officer, in contrast to the proconsuls who wore the national attire of a civilian toga with the purple strip.22 Their rank was junior to the governors of proconsular provinces too, and to emphasize the fact, they had five rather than a full complement of six lictors.23

Grateful for his generosity and willingness to term-limit his powers, the Senate sought a suitable title for him in recognition. Imp. Caesar knew not to demand the title of dictator perpetuo as his great uncle had. Dio records that Caesar was rather keen on the name Romulus, after the city’s legendary founder; sensitive to its negative associations with royalty, however, he desisted from pushing the matter.24 At the suggestion of Munatius Plancus – a crafty man who had switched sides many times during his career before settling on Caesar’s – the Senate unanimously voted him the honorific title Augustus, a word meaning ‘the revered one’.25 The name did not carry any inherent hard power – he already had abundant auctoritas (the prestige or personal influence derived from his victories, political achievements and legacy as heir of Iulius Caesar), as well as legal military power (imperium) conferred on him by virtue of being an elected consul of the Res Publica. Yet it did come with the soft power derived from its religious connotation, indicating that a person so named was sacred or worthy of worship.26 From that day forth it was the name by which he was called – and is still best known today.27

Map 3. The Roman Empire, 27 BCE.

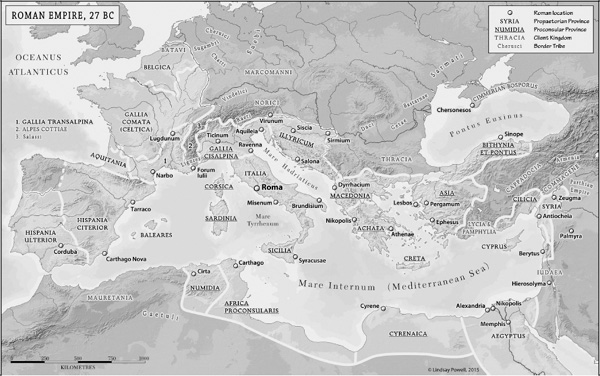

Figure 2. Augustus presented himself as a commander-in-chief, taking Imperator as his first name. He counted the imperatorial acclamations of his deputies as his own (see Res Gestae 4).

Imp. Caesar Divi filius Augustus was also voted a slate of new honours, many using ancient symbols designed to evoke old traditions borne of success in war. By ending the conflict he had saved the lives of countless fellow citizens (expressed on coins and inscriptions by the phrase ob cives servatos) (plate 12), in recognition of which he was permitted to grow a laurel tree outside his house on the Palatinus Hill, while from his front door he could hang a crown made of leafy oak twigs, emblems of peace and victory, images that were promoted on coins (plate 13).28

The Senate also granted him the right to display a round ‘Shield of Virtue’ (clipeus virtutis) (plate 14) in the Curia, upon which were inscribed his cardinal virtues of ‘courage, clemency, justice and duty’.29 It hung close to the statue of winged Victory.30

While political control of the army transferred peacefully in Rome, her troops were engaged in the bloody business of combat operations elsewhere. Shrewdly, Caesar Augustus decided it would be wise to absent himself from Rome for a while. Shortly before 4 July, leaving Rome in M. Agrippa’s care, he headed north by land. Augustus was keen to make his mark on the world. He had ambitions for conquest beyond the present borders of Empire. In his chronicles Dio records:

He also set out to make an expedition into Britannia, but on coming to the provinces of Gallia lingered there. For the Britons seemed likely to make terms with him.31

Years before, Iulius Caesar had launched two amphibious campaigns to the island, in 55 and 54 BCE. Neither amounted to much more than raids, but he won great notoriety as the first Roman to traverse the British Ocean and gained political capital from the story.32 By actually conquering Britannia, Augustus would achieve something his adoptive father had not.33

The chance for glory had to be offset by the need for pragmatics. The deceased commander had failed to begin, let alone complete, the process of pacification of the Gallic territories that he had spent a decade conquering. In 27 BCE, ‘the affairs of the Gauls were still unsettled, as the civil wars had begun immediately after their subjugation’, writes Dio.34 The security of the people of the provinces had remained precarious for a generation. The presence of a semi-permanent Roman army in the region is implied, but the historical sources give no indication as to the number, type or whereabouts of units. The confederacy of fourteen nations forming the Aquitani (between the Garonna and Liger rivers) had rebelled while Agrippa had been governor in 39/38 BCE, and had been quelled by him.35 In 27 BCE they rose up again. M. Valerius Messalla Corvinus (consul of 31 BCE) was dispatched to deal with the problem; with him was Albius Tibullus, a young officer who ‘was his tent companion in the war in Aquitania and was given military prizes’.36 Indeed, Corvinus would celebrate his success with a triumph in fine style in Rome on 25 September this year.37 But there had been other sporadic uprisings since in Belgica, and incursions by Germanic bandits from across the Rhine.38

After war came the opportunity to make peace. The Romans had a plan for post-war pacification.39 Independent tribes would be transformed into urban Romanized communities with a national identity. Army surveyors would mark out the foundation of new towns in which to resettle the people from their hilltop strongholds. The leading families would be assimilated into the political system modelled on the institutions of the Res Publica. It began with a census to assess the size of the population and its wealth in coin and ability to produce grain, fruit, hides and the basic necessities. This would, in part, pay in coin and kind for the army based there to defend it.40 The information-gathering process took time and was conducted by the staff of the legatus Augusti pro praetore. Augustus likely wintered at Colonia Copia Felix Munatia (modern Lyon). It was the leading city of the Gallic region, from which metalled roads built by Agrippa radiated and along which troops and officials could move unhindered.41

On 25 July, M. Licinius Crassus celebrated his triumph for his victories in Thracia and the territory that would later become known as Moesia (see Table 6). Also this year, Polemon Pythodorus of Pontus was recognized as an ally of the Roman People.42 He was among the first of many allied kings who had supported M. Antonius now seeking to reconcile with the victor of the Battle of Actium and ‘First Man’ in Rome.

Imp. Caesar Divi f. Augustus VIII T. Statilius T. f. Taurus II

Having played a crucial part at Actium and recently performed with distinction in the Iberian Peninsula, Statilius Taurus was rewarded with a second term as consul alongside Augustus, now serving his eighth term.43 On 26 January, Sex. Appuleius (cos. 29 BCE) celebrated his triumph in Rome for victories in Hispania Citerior.44 Meanwhile, Augustus sought an opportunity for military glory for himself. Remote Britannia might provide it. In assessing the chance of success, he may have hoped for a quick campaign to take the island, or at least to make all or parts of it a client kingdom, but the politics were complex: there were numerous tribes – some pro- and others anti-Roman – many of which were warring with each other. Kings Dumnobellaunus and Tincomarus are known to have sought the friendship of the Romans, and likely met Augustus in person.45 His attempts at diplomacy with the Britons, however, failed when the people with whom the Romans were negotiating refused to agree terms.46 The information that has come down to us is too cryptic to determine the extent and seriousness of Augustus’ ambitions for annexing the land over the ocean.47 The conquest of Britannia would have to wait. There were other matters now needing his urgent consideration.

Satisfied that public affairs in Aquitania, Gallia Comata and Belgica were under control, Augustus proceeded to the Iberian Peninsula, intending to ‘establish order there also’.48 Augustus arrived in Segisama (Sasamon, west of Burgos) and made it his forward base of operations.49 Roman forces had been active for almost a decade in the region between the Basque Country and Cantabria (as the recent discovery of a military installation at Andagoste (Cuartango) shows), but they had failed to stop the violent resistance of the local people.50 Despite Statilius Taurus’ successes in the region three years before, the Astures and the Cantabri in the north and northwest of the peninsula continued to resist full annexation.51 They also represented a threat to territory recently acquired by Romans, for ‘not content with defending their liberty, they tried also to dominate their neighbours and harassed the Vaccaei, the Turmogi and the Autrigones by frequent raids’.52 Banditry (latrocinium) was a particular problem:

There was a robber named Corocotta, who flourished in Iberia, at whom he [Augustus] was so angry at first that he offered a million sestertii to the man that should capture him alive; but later, when the robber came to him of his own accord, he not only did him no harm, but actually made him richer by the amount of the reward.53

Augustus decided that only a full-blooded military campaign using overwhelming force would finally break these unyielding peoples and that he, personally, would lead it.54 In preparation for the campaign, he assembled an immense force, including Legiones I Augusta, II Augusta, IIII Macedonica, V Alaudae, VI Victrix, VIIII Hispana, X Gemina and XX55 (see Order of Battle 1). They were supported by auxiliary cavalry from Ala Augusta, Ala II Gallorum, Ala Parthorum and Ala II Thracum Victrix Civium Romanorum; and auxiliary infantry from Cohors II Gallorum and Cohors IV Thracum Aequitata.56 The total land force deployed was up to 52,000 troops. The number of enemy troops they would face is not recorded.

Augustus had with him two experienced legati.57 The first, C. Antistius Vetus (serving with him as suffect consul in 30 BCE), was the former proconsul of Gallia Narbonnensis who had lost the war with the Salassi; nevertheless, he brought experience of mountain warfare and, perhaps, now older and wiser, sought an opportunity to redeem himself.58 He now replaced Sex. Appuleius as legatus Augusti pro praetore.59 The second legate, P. Carisius, had served in the war against Sex. Pompeius in Sicily on Imp. Caesar’s side, and was eager to take on a senior command role.60 Also accompanying Augustus was Ti. Claudius Nero (his stepson by Livia) and M. Claudius Marcellus (his nephew by his sister Octavia); both aged 16, they were beginning their military careers as tribunus militum.61

Order of Battle 1. Cantabria and Asturia, 26–19 BCE. Several units of ethnic auxilia are recorded as having served in Hispania including Cohors II Gallorum and Cohors IV Thracum Aequitata as well as Ala Augusta, Ala II Gallorum, Ala Parthorum and Ala Thracum Victrix C.R.

Over many years the warriors of the two aboriginal peoples had proved very able to resist the Romans. From strongholds in the hills and valleys of the craggy Cantabrian Mountains, they forced a guerrilla-style war upon an enemy trained to fight set-piece battles on open plains.62 The trouser and tunic-wearing warrior of the Astures and Cantabri preferred light equipment optimized for ambuscades and skirmishes. He fought with either a leaf-shaped dagger (pugio) a short, straight double-edged stabbing sword (gladius hispaniensis) or a curved, singleedged falcata, or more commonly with darts or spears; he defended himself with a buckler (caetrae) – concave in shape and made from wood and leather, two feet in diameter – or a rectangular scutum; and on his head wore a leather hood to cover his long hair or, if he could afford one, a bronze helmet.63 The Cantabrians alone among the Celt-Iberian peoples used the double-headed axe (bipennis).64 Their cavalry were renowned for their tight formation fighting, notably the circulus Cantabricum in which a single file of riders rode in a circle while launching a volley of missiles; and the Cantabricus impetus, a fast, massed charge at the enemy troops.65 An infantryman might ride into battle seated behind a cavalryman and dismount to engage the opponent on foot.66

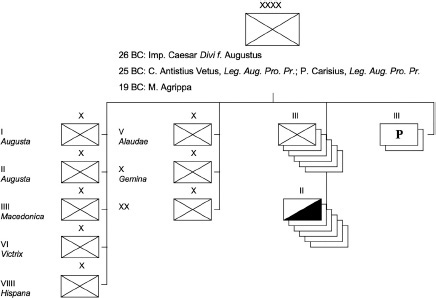

While Dio writes ‘Augustus himself waged war upon the Astures and upon the Cantabri at one and the same time,’ in practice he treated them as two separate targets.67 The first mission was to reduce to submission the Cantabri. In a coordinated three-pronged offensive, he led one of the army groups from Segisama in the south, while Vetus and Carisius commanded the other two (map 4).68 The first recorded battle of the campaign was fought under the walls of Attica or Vellica (modern Helechia), 5 miles south of the base of Legio IIII.69 It was a swift victory. Beaten, the Cantabri grudgingly withdrew to Mons Vindius or Vinnius (possibly Peña Santa) – described as ‘a natural fortress’ – in the expectation the Romans would not to follow them into the mountains, where they could exploit the terrain to their advantage.70 The enemy the Romans faced was agile, cunning and resilient. Dio writes:

But these peoples would neither yield to him, because they were confident on account of their strongholds, nor would they come to close quarters, owing to their inferior numbers and the circumstance that most of them were spear-throwers, and, besides, they kept causing him a great deal of annoyance, always forestalling him by seizing the higher ground whenever a manoeuvre was attempted, and lying in ambush for him in the valleys and woods.71

Despite the massive resources Augustus had deployed, the campaign was not delivering the results he sought. Vindius only fell to him when the people trapped inside began to starve and surrendered.72 He opened a new front on the northern side when he ordered transports to sail from Aquitania with troops – perhaps of Cohortes Aquitanorum Veterana formed from men of the fleet at Forum Iulii – who ‘disembarked while the enemy were off their guard’.73 At the city of Aracillum or Racilium (possibly modern Aradillos or Espina del Gallego), the rebels held out, before finally succumbing to Augustus’ troops.74 With Roman forces now advancing upon the rebels on several sides, they gradually ‘enclosed its fierce people like wild beasts in a net’, as one historian described the attack.75 The war began to turn in the Roman commander-in-chief’s favour. Indeed it may have been during this campaign that Legio VIIII received its honorific title Hispana or Hispaniensis for victory in battle. Archaeological investigations demonstrate the intensive use of artillery (both large and small calibre) to overwhelm the native defenders of the hilltop stronghold at the oppidum of Monte Bernorio.76

Map 4. Military operations in Asturia/Cantabria, 25–23 BCE.

When not assessing military strategies and tactics, Augustus attended to official matters. His mind also turned to a new project by P. Vergilius Maro – not a military man but a poet of high regard from Mantua. He had come to the princeps’ attention through his close friend Maecenas, who was patronizing poetic talents for his amusement and edification. Impressed by his work thus far, Augustus had commissioned Vergil to compose an epic poem two years earlier. Called the Aeneid, it would describe the flight of the warrior Aeneas from Troy after its fall to the Greeks and his epic journey to Italy, ultimately leading to the foundation of Rome.77 The mythological story greatly appealed to the princeps. It would be an allegorical narrative for the new age of renovation and restoration he was pioneering, glorifying old Roman values and appealing to the nation’s belief in its exceptionalism. Augustus was impatient to see evidence of progress on it even as he was fighting the Cantabri. He:

demanded in entreating and even jocosely threatening letters that Vergil send him ‘something from the Aeneid’; to use his own words, ‘either the first draft of the poem or any section of it that he pleased’.78

The harassed poet obliged and from then on sent him regular instalments.

In Egypt, allegations of serious misconduct were being levelled against the equestrian official Augustus had personally appointed in 30 BCE. Cornelius Gallus had seemed like a good choice for Praefectus Aegypti at the time, but the trappings of near absolute power and the sycophancy shown by the Egyptian bureaucrats had corrupted his good judgment, and accentuated his natural arrogance and determination:

He indulged in a great deal of disrespectful gossip about Augustus and was guilty of many reprehensible actions besides; for he not only set up images of himself practically everywhere in Egypt, but also inscribed upon the pyramids a list of his achievements.79

Gallus’ comrade and closest friend Valerius Largus informed Augustus of the man’s indiscretions and bizarre behaviours.80 Emboldened by the informant, others soon came forward with their own examples of the prefect’s impropriety and overindulgence. The Senate voted to arraign him to face charges in Rome, urging that his punishment should be exile and the confiscation of his assets.81 Gallus could not look to Augustus for help: he had committed the cardinal sin of betraying the princeps’ trust and friendship. He knew his career was over. Before the decree of the Senate was even served and took effect, Gallus ended his own life.82

Largus was an ambitious man who thought that he would assume Gallus’ office. He was, in fact, becoming powerful by attracting a large following.83 However, a certain Proculeius:

conceived such contempt for Largus that once, on meeting him, he clapped his hand over his nose and mouth, thereby hinting to the bystanders that it was not safe even to breathe in the man’s presence.84

It was a calculated and very public snub. The choice of successor was not Largus’ decision to make, but that of Augustus, and he had already chosen another man. The new Praefectus Aegypti was C. Aelius Gallus.85 He took over the position this year. Thereafter Largus vanishes from recorded history.

Imp. Caesar Divi f. Augustus IX M. Iunius M. f. Silanus

In the western Alps, the Salassi nation rose up in revolt. This Iron Age ‘Celtic’ people occupied a strategically important position: they mined gold and levied tolls on the road between Gallia Narbonensis and Gallia Cisalpina, but they also engaged in banditry, all of which drew the interest of the Romans.86 An attempt to subjugate them in 35 BCE by the then proconsul of Gallia Narbonensis, C. Antistius Vetus, and another by Messalla, had both failed.87 To deal with the ongoing problem, this time Augustus dispatched A. Terrentius Varro. Nothing is known of his background; he seems, however, to have been a competent field commander.88 Geography largely determined how he would have to run his campaign. The Salassi lived in a deep glen at the confluence of the Buthier and the Dora Baltea, at the intersection of the Great and Little St Bernard routes, accessible only by passes which they themselves controlled, including the main road from Italy.89 Varro employed a multi-pronged attack approach, invading their territory at different points simultaneously.90 It worked: in Livy’s economical phrasing, ‘the Salassi, an Alpine people, were subdued.’91 They had been unable to meet their opponents either with sufficient numbers or to unite together to repel them. In a single campaign, Varro had won an important victory for Augustus.92 Their punishment was heavy:

After forcing them to come to terms he demanded a stated sum of money, as if he were going to impose no other punishment; then, sending soldiers everywhere ostensibly to collect the money, he arrested those who were of military age and sold them, on the understanding that none of them should be liberated within twenty years.93

The prisoners of war were taken to nearby Eporedia (modern Ivrea) – Strabo claims 36,000 were captured, of which 8,000 were men at arms – and sold as slaves.94 Where Varro had struck his camp he founded a new colonia, a city for some 3,000 retiring soldiers, among them Praetorians in whose honour it was granted the name Augusta Praetoria Salassorum (modern Aosta).95 The presence of so many veterans would help keep the peace in the region and ensure the allimportant road through the western Alps stayed open.

Further north, perhaps in retribution for the actions of C. Carrinas back in 30 BCE, Roman traders travelling on the Right Bank of the Rhine found themselves under attack, taken prisoner and brutally executed.96 The new proconsul of Gallia Comata and Belgica, M. Vinicius, led a punitive raid into Germania Magna. No details survive of the course of the campaign, nor from where along the river it was launched, but it was considered a success. His troops acclaimed Augustus as imperator, who counted it as his eighth cumulative award.

In the Iberian Peninsula, the war of conquest began anew. As he so often did during a military campaign, Augustus fell ill. Dio suggests over-exertion and anxiety, while Suetonius says ‘he was in such a desperate plight from abscesses of the liver’, though it is entirely possible that it was typhus.97 He was moved urgently from the war zone to Tarraco (modern Tarragona) on the Mediterranean coast, where he remained in the care of his wife, Livia, and personal physician, Antonius Musa.98 He would remain there for several months in intensive care. Augustus had pushed himself too far. He would never again lead a military campaign in person. From now on he would rely completely on his legati to fight his wars for him.

‘Meanwhile,’ writes Dio:

Caius Antistius fought against them and accomplished a good deal, not because he was a better commander than Augustus, but because the barbarians felt contempt for him and so joined battle with the Romans and were defeated. In this way he captured a few places, and afterwards Titus Carisius took Lancia, the principal fortress of the Astures, after it had been abandoned, and also won over many other places.99

Florus elaborates on the events leading to the siege of Lancia. Carisius’ army had pitched three marching camps over the winter beside the Astura (Esla) River.100 The Astures came down from their snow-capped mountain retreats en masse and, dividing into three groups, settled close to the Romans in preparation for an allout attack.101 Outnumbered, the Romans faced annihilation, but their luck held. Having been forewarned by the Brigaecini – whose act was seen as treachery by the Astures – Carisius arrived just in time with reinforcements. Carisius engaged the enemy in the open and defeated them, and though he took casualties, the addition of the relief troops turned the odds firmly in the Romans’ favour. The Astures withdrew to stage a desperate last stand:

The well-fortified city of Lancia opened its gates to the remains of the defeated army; here such efforts were needed to counteract the natural advantage of the place, that when firebrands were demanded to burn the captured city, it was only with difficulty that the general won mercy for it from the soldiers, on the plea that it would form a better monument of the Roman victory if it were left standing than if it were burnt.102

The last recorded battle in the Bellum Cantabricum et Asturicum is the siege of Mons Medullius (possibly Peña Sagra) ‘towering above the Minius [Miño] River’.103 To seal in the rebels, the Roman army surrounded it with a continuous earthwork comprising a ditch and palisade 15 or 18 miles long.104 The blockade then began. Time was on the side of the Romans. With supplies unable to get in and all routes of escape cut off, the defenders trapped inside were eventually forced to submit. Once in Roman hands, Carisius erected the traditional tropaeum of a victor. On a tree trunk staked in a mound covered with round shields, daggers, swords and double-headed axes captured from the Astures, hung the bloody panoply of an unnamed, vanquished rebel commander.105 The proud legatus Augusti later commemorated the sacred victory monument on coins (plates 15 and 16).106 The veterans (men who had served sixteen years or more) of Legiones V Alaudae, X Gemina and XX were honourably discharged and settled in a new colonia, founded – most likely by Carisius – especially for them with grants of land in the newly conquered region, at Augusta Emerita (modern Mérida).107

There were also developments in the kingdoms of the allies. King Iuba II (plate 24) was a handsome man in his mid-20s, clean-shaven with short hair, who had an inquiring mind and a talent for writing. After his capture by Iulius Caesar he had been educated in Italy. Since then he had become a good friend of his heir, ruled a kingdom in Africa. He was asked to yield parts of Gaetulia and Numidia to the Romans in exchange for Mauretania and lands formerly ruled by Bokchus and Bogud.108 He complied without contest. In the East, Amyntas, king of Lycaonia and Galatia, unexpectedly died. An ambitious regent, he had been waging a war against bandits from the Homonadeis nation living in his kingdom and may have been killed in an ambush or a plot.109 Formerly an ally of M. Antonius, he had switched his allegiance to Augustus and since proved loyal to him. By prior agreement, his kingdom was to pass into the possession of the Roman People as a Province of Caesar. Rome now had a major territory right in the centre of Asia Minor. Its first governor was M. Lollius, a promising and ambitious novus homo from a plebeian family who had fought with Caesar at Actium.110 As legatus Augusti pro praetore, he began the process of integrating the territory into the Roman Empire, which included assimilating its army. It was reconstituted as Legio XXII Deiotariana (named after Amyntas’ antecedent Deiotarus II). The city formerly known as Antiocheia was refounded in the new province as a colonia called Caesarea for Roman veterans of Legiones V Gallica and VII.111

Though Augustus himself ended the year in uncertain health, the Senate received with delight his reports of successes across his provincia:

A triumph, as well as the title, was voted to Augustus; but as he did not care to celebrate it, a triumphal arch was erected in the Alps in his honour and he was granted the right always to wear both the crown and the triumphal garb on the first day of the year.112

While Roman soldiers fought in far-away lands, the doors of the precinct of Ianus in Rome had stayed open. With the campaign season’s victories and the ending of wars, Augustus closed them for the second time.113

Imp. Caesar Divi f. Augustus X C. Norbanus C. f. Flaccus

Augustus recovered sufficiently to leave Tarraco and depart for Rome.114 The Roman Senate and People expressed their relief when he reached the city:

Various other privileges were accorded him in honour of his recovery and return. Marcellus was given the right to be a senator among the ex-praetors and to stand for the consulship ten years earlier than was customary, while Tiberius was permitted to stand for each office five years before the regular age; and he was at once elected quaestor and Marcellus aedile.115

As the next legatus Augusti pro praetore of Hispania Citerior he appointed, according to one source, L. Aelius Lamia, to another L. Aemilius Paullus Lepidus (cos. 34 BCE).116 The contemporary historian Velleius Paterculus describes Lamia as ‘a man of the older type, who always tempered his old-fashioned dignity by a spirit of kindliness’.117 His mild nature would be tested by both the rugged Cantabrian Mountains and its tough, resourceful peoples. To prove they were still unbeaten, the Astures and Cantabri rebelled once again. They hatched an elaborate, but cruel, subterfuge:

Sending word to Aemilius, before revealing to him the least sign whatever of their purpose, they said that they wished to make a gift to his army of grain and other things. Then, after securing a considerable number of soldiers, ostensibly to take back the gifts, they conducted them to places for their purpose and murdered them.118

Lamia (or Lepidus) now showed how tough-minded a vir antiquissimi could be. He ordered his troops to devastate the rebels’ lands and mete out harsh punishments to anyone taken captive. To ensure no future revolts, the hands of all the prisoners of war were cut off. Within the year the revolt was over.119

In Egypt, the new Praefectus Aegypti had initiated a war against neighbouring Arabia Felix.120 According to Strabo, who knew Gallus and may have been a friend, Augustus personally authorized the expedition:

He was sent by Augustus Caesar to explore the tribes and the places, not only in Arabia, but also in Aethiopia, since Caesar saw that the Troglodyte country which adjoins Aegyptus’ neighbours upon Arabia, and also that the Arabian Gulf, which separates the Arabians from the Troglodytes, is extremely narrow. Accordingly he conceived the purpose of winning the Arabians over to himself or of subjugating them.121

There were economic attractions to annexing the territory. The Arabians were wealthy from trading in spices, gold, silver and gemstones with merchants in the Near East, northern and eastern Africa and even India.122 It was a prize worth having and, so he thought, ripe for the taking.

Gallus assembled an expeditionary force of 10,000 infantry, comprising men of the Roman garrison of province Aegyptus and of allies – 500 Jewish troops were provided by Herodes, and 1,000 Nabataeans arrived from Petra with their administrator, Syllaeus.123 Expecting to engage the enemy on the sea, the prefect invested in eighty vessels (biremes, triremes and light boats) built at the shipyard at Kleopatris (or Arsinoê, modern Suez), located on a canal which connected the Nile River to the Gulf.124

Setting off in early summer, Gallus met no opposition initially, and when he did encounter resistance his army was able to overwhelm and defeat the attackers.125 Gallus had been assured by Syllaeus that he would provide whatever guidance he could.126 By his personal assurances he had won the complete confidence of the Roman commander.127 Unknown to the praefectus, however, Syllaeus was operating duplicitously. Strabo surmises that he intended to reconnoitre the lands they entered so that he could later annex them for his own nation of Nabataea.128 To that end he took the expeditionary force on a long detour down the coast, where there were no natural harbours for the ships to berth but, instead, shallows and reefs or strong tides that presented real dangers to them. By the time the expeditionary force reached the entrepôt of Leukê Komê (meaning White Village) a fortnight later, several of the ships had already been lost to accidents, not to warfare.

The soldiers had suffered too. The harsh terrain, the fierce heat of the sun and the poor quality of the potable water took a heavy toll on his men, to the extent that he lost the larger part of his army to sickness.129 Dio describes the symptoms:

[they] attacked the head and caused it to become parched, killing forthwith most of those who were attacked, but in the case of those who survived this stage it descended to the legs, skipping all the intervening parts of the body, and caused dire injury to them.130

A cure proved to be a blend of olive oil and wine – taken orally and applied as an ointment – but few had access to the remedy. Strabo provides an alternative interpretation: the men suffered from stomacacce, a form of paralysis around the mouth, and scelotyrbe, lameness of the legs – both afflictions allegedly being caused by consuming the local water and herbs.131 So many men were afflicted with ailments that Gallus had to suspend operations for the rest of the season until they could recover.

Finally, after several weeks had passed, his men had recuperated and Gallus ordered them to march on. They now entered regions of the Arabian Peninsula where there was no water and all supplies had to be carried on camels’ backs. Syllaeus’ connivance took the Romans on a roundabout journey until thirty days later they reached the country of Aretas, a kinsman of a certain Obodas, where they were able to replenish basic provisions.132 For the next fifty days they trudged over tracts of desert before reaching Negrani (Negrana), a municipality set in a lush landscape. Its king, Sabos, seeing the large army marching towards the settlement, had apparently fled and left it undefended. Gallus seized the town; but the king returned six days later, bringing with him an army of his own. The two opposing forces met at the river and fought. Strabo states that the Arabians took 10,000 casualties to only two Roman. He explains that the Arabians’ weapons – bows and arrows, spears, swords, slings and double-headed axes – and their combat skills were no match for the Romans’ equipment. The Romans then besieged Asca, which had also been abandoned by its king, and took it too. After acquiring nearby Athrula, Gallus installed a garrison which foraged for provisions, including grain and dates. His army then moved on Marsiaba, which belonged to the Rhammanitae nation, who were subjects of a certain Ilasarus. After six days the city still would not fall to Gallus and, with his water rations depleting, he was forced to suspend the siege.133

When interrogated, the prisoners his men had captured informed him that the lands that produced the famous spices he had come to find were just two days’ march away. The secret was out. He now realized that Syllaeus had duped him into wandering around the peninsula for almost six months in search of them. He quickly formulated his own plan to return to Egypt without the Nabataean’s help. The march back took just sixty days. Reaching the Myus Harbour, the few remaining Roman survivors who had endured the campaign’s hardships marched to Coptus and finally arrived at Alexandria. Remarkably, of the expeditionary force which had left half-a-year before, only seven men were lost to fighting, the rest having died from sickness, hunger or fatigue.

Strabo did not blame Gallus for the failure. He writes, ‘indeed, if Syllaeus had not betrayed him, he would even have subdued the whole of Arabia Felix.’134 Perhaps echoing Gallus’ own words, Strabo explains, ‘this expedition did not profit us to a great extent in our knowledge of those regions, but still it made a slight contribution.’135 Dio offers a more generous assessment:

These were the first of the Romans, and, I believe, the only ones, to traverse so much of this part of Arabia for the purpose of making war; for they advanced as far as the place called Athlula [modern Baraquish in Yemen], a famous locality.136

Augustus himself presented the venture as a great imperial success.137

While Aelius Gallus was away, the imperial province of Aegyptus also came under surprise attack. An army of 30,000 of the Kushite (or Nubian) kingdom of Meroë in Ethiopia led by King Teriteqas invaded Triakontaschoenus Aethopiae and crossed the Roman Empire’s southernmost border at the First Cataract (map 5).138 They reached the Island of Elephantine in the Nile and sacked the city of Syene, taking captives. They pulled down a bronze statue of Augustus and hauled its head away, burying it in the steps of a victory temple they erected at Meroë.139 Notwithstanding the positive spin on the failed campaign in Arabia Felix, Gallus’ high-profile career was over; his replacement, C. Petronius, was already on his way.140 The Nabataean Syllaeus was tried in Rome for betraying his friendship with the Romans, as well as other crimes, and beheaded.141

| Imp. Caesar Divi f. Augustus XI | A. Terentius A. f. Varro Murena | |

| suff. | L. Sestius P. f. Quirinalis | Cn. Calpurnius Cn. f. Piso |

Augustus’ health had not improved since leaving Tarraco. Although voted the consulship for the eleventh time, he felt so sick that he decided it would be wise to make arrangements for the transfer of his responsibilities over his provincia and the armed forces in it. He convened a private meeting of magistrates, the leading senators and equestrians.142 Resigning the consulship, he gave the suffect consul Cn. Calpurnius Piso ‘the list of the forces and of the public revenues written in a book, and handed his ring to Agrippa’.143 Many began to believe the worst, that he had just days to live. There were speculations about who would succeed him: would it be his nephew, Marcellus, or his right-hand man, Agrippa? Then, having tried everything else but failed to find a cure, his personal physician Antonius Musa put his patient on a course of cold treatments. To everyone’s surprise – and relief – Augustus staged a near-miraculous recovery.144

Map 5. Egypt.

His young nephew Marcellus, however, was not so fortunate. Despite treatment administered by Musa, he died – perhaps from typhus – at Baiae (modern Baia), aged just 19.145 He was given a public funeral in Rome with eulogies and his ashes were placed in Augustus’ own mausoleum.146 During a subsequent private reading of Books 2, 4 and 6 of the draft Aeneid to the imperial family, the teenager’s mother Octavia fainted at hearing the name of her son.147

Agrippa, the 40-year old man now popularly regarded as Augustus’ successor, left Rome and took up an assignment supervising the provinces in the East. His seemingly hasty departure led some to wonder about the state of his relationship with the ‘First Man’ in Rome.148 Agrippa set up his office in Mytilene rather than at Antiocheia in Syria, the preferred base of visiting Roman officials when in the region – a decision that only added to the speculation about his mission.149

An embassy from Parthia arrived in Rome to meet with Augustus.150 It had been sent by Frahâta (Phraates) IV (plate 18), who requested that Augustus return his son in involuntary exile in the city. His captor, Tiridates II, had briefly occupied the Parthian throne at the time of the Battle of Actium but been ousted by Frahâta and fled, seeking sanctuary among the Romans in 26 BCE; he had taken Frahâta’s son with him as a hostage.151 Augustus refused the king’s demand, but, seeing an opportunity, suggested that he could consider an exchange of the Parthian prince for the captured signa and survivors from the defeat of M. Licinius Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BCE and of M. Antonius in 40 and 36 BCE in the region.152 Romans could accept tactical defeats, but the loss of the legionary aquila was considered graves ignominias cladesque – ‘a grave and severe disaster’ – leaving the nation feeling infamia, ‘shame’ or ‘humilation’.153 With this diplomatic trade Augustus saw a chance to expunge the stain on the country’s honour and raise his own prestige. The emissaries promptly left to present the Roman leader’s counteroffer to their king. It would be months before they crossed the border of the Parthian Empire.

In Hispania Citerior, Carisius was asserting his position as Augustus’ deputy in the region. The mint in the new colonia at Emerita poured out silver coins to fill the veterans’ purses, each bearing his name and title, as well as images of rebel arms and equipment captured in the recent war.154 Where he had shown foresight in saving a community of Astures in the aftermath of battle, he now manifested signs of blindness in his dealings with the same people in peacetime. Unwittingly, he was sowing seeds for a new crop of discontentment.

In Italy Tiberius (plate 23), now 19 years old, served out his term as quaestor.155 One of his tasks was:

the investigation of the slave-prisons throughout Italy, the owners of which had gained a bad reputation; for they were charged with confining not only travellers, but also those for whom dread of military service had driven to such places of concealment.156

A stern disciplinarian, Augustus had no tolerance for deserters.157

M. Claudius M. f. Marcellus Aeserninus L. Arruntius L. f.

For the first time in eight years, Augustus did not hold the consulship. By unfortunate coincidence, the conditions in the homeland were dire this year: in Rome, the Tiber had flooded its banks, inundating parts of the city, while a pestilence had spread throughout Italy and famine gripped the population.158 Connecting Augustus’ decision not to stand as consul with the nationwide affliction, many people urged him to assume the powers of dictator (awarded to a single individual only at a time of emergency). The Senate objected. For refusing to accede to their wishes, a mob locked them in the Curia while the People voted in their Assembly for the proposition to make it law.159 Augustus adamantly refused to accept the plebiscite, tearing at his clothes to express his exasperation at the People’s persistence, though he relented to their wishes that he accept the post of commissioner for the grain supply.160

Augustus’ patience was tested again this year when a case went before the courts which seemed to challenge the transparency with which he applied his war-making powers. The proconsul of Macedonia, M. Primus, had initiated an unauthorized war against the Odrysae.161 When called to explain himself, Primus said he had made war with the approval of Augustus, but then later changed his story to say it was consul M. Claudius Marcellus who had authorized it. Hearing his name was being dragged through the courts, Augustus appeared in person. The praetor presiding over the case put the question directly to the Princeps Senatus: had he authorized the war? Augustus replied he had not; Macedonia was a proconsular not a propraetorian province, which mean he had no authority over it. Dio records the ensuing contretemps:

And when the advocate of Primus, Licinius Murena, in the course of some rather disrespectful remarks that he made to him, enquired: ‘What are you doing here, and who summoned you?’ Augustus merely replied: ‘The public weal’.162

Many of the bystanders laughed at the retort. On a vote of the jury Primus was acquitted. The verdict upset many in the aristocracy, however. Plots to assassinate the princeps were hatched. One, an amateurish affair in which the outspoken Murena was himself implicated, was discovered and the conspirators were tried in secret.163 Another, conceived by senator Ignatius Rufus, also ended badly for the would-be assassin.164

Augustus left Rome and departed for Sicily, taking Tiberius with him.165 On the island he established a colonia for retired soldiers at Syracusae (modern Siracusa).166 He was aware that he needed to show progress was being made in pacifying his provincia. To that end he returned to the Senate both ‘Cyprus and Gallia Narbonensis as districts no longer needing the presence of his armies’, but in the process gained Illyricum.167 In Hispania Citerior, however, his army was still essential. Peace in the north of that country remained as elusive as ever. Rome’s old enemies, the Astures and Cantabri, rebelled once again.168 Dio ascribes the cause of their uprising this time to the excesses and cruelties of Carisius. He had been joined by C. Furnius, a man who had impressed Augustus when, years before, he appealed to him in person to save the life of his father, a known supporter of M. Antonius.169 His boldness and filial loyalty earned him the princeps’ respect and a place among the ex-consuls.170 He was now to show some of that boldness in the Iberian Peninsula. If the warriors of the mountains thought he would be easy to beat, they soon discovered he was as resolute as his colleague in breaking their will.171 He had briefed himself well on the situation among the tribes. In tandem the Roman commanders used a divide and conquer strategy. Furnius engaged the rebels, working with Carisius to reduce the Astures further west.172 The Astures, in response, besieged one of the Roman army camps, hoping to destroy the men within its wooden palisade. They were unable to take it, and later were themselves defeated in open battle. Through attrition, their national resistance collapsed. Many were taken as prisoners of war. The Cantabri fought on desperately until, resigned to imminent defeat, many took their own lives by sword, poison or immolation rather than be captured by the Romans and sold as slaves. The legates also subdued the Gallaeci in the far northwest of the Iberian Peninusla.173

In Egypt, C. Petronius was determined to re-establish Roman control over Triakontaschoenus Aethopiae, which had been invaded by Teriteqas two years before. Three legions and several cohorts of auxiliaries were under his direct command. From them he drew some 10,000 infantry and 800 cavalry. Eschewing the ‘lightning war’ strategy of his predecessor Cornelius Gallus, Petronius took a more diplomatic approach.174 Leading the Meroites was Amanirenas Kandake (Queen Candace). She might be the widow of Teriteqas. Strabo characterizes her as ‘a masculine sort of woman, and blind in one eye’ – a description which probably owes more to a Roman stereotype of barbarian queens in general than an accurate portrait of her.175 Petronius sent envoys to demand to know why the Ethiopians had started the war and to request the return of the stolen goods and prisoners. The Ethiopians replied that the nomarchs (the local senior officials who administered the nomes into which Egypt was divided) had wronged them. The Roman emissaries explained that they did not rule the country but Caesar did. The Ethiopians then asked for three days to deliberate the issue. Growing impatient at the delay, Petronius forced them to engage him in battle. The Ethiopian warriors – carrying axes, pikes and swords and defending themselves with large oblong shields covered with ox hide – retreated when faced with the heavily armed and well-equipped Roman alliance troops. Casualties were light, however. Some made their way to Pselchis. Others fled to a nearby island in the Nile or into the desert. The rest were taken alive, forced on to rafts and ships and sailed up river to Alexandria. Petronius then moved on Premnis (present day Qasr Ibrim) and captured it.

From her location near the royal capital Napata (modern Karima in Northern Sudan), Kandake sent her own ambassadors to Petronius to negotiate a truce.176 She offered to return all the Roman prisoners and booty. The prefect gave his answer in fire. Roman troops poured into Napata, snatched its treasures, took its inhabitants as slaves and razed the city. Kandake’s son, Akinidad, only just managed to evade capture.177 As further punishment, Petronius imposed a tribute on the Ethiopian nation.178 The praefectus could have marched still further south, but the practicalities of waging a war in a foreign country factored into his calculus. Instead he ordered his troops to turn around and march home. En route they improved the fortifications at Premnis in Triacontaschoenus Aethopiae and installed a garrison there with enough supplies to support 400 men for two years. When finally back in the provincial capital, Petronius sold most of the captives but, eager to avoid his predecessor’s fate, he sent a thousand of them to Augustus.

M. Lollius M. f. Q. Aemilius M’. f. Lepidus

At the beginning of the year riots broke out in Rome when the public, believing one of the two curule chairs was intended for Augustus, was disappointed to learn that he had declined it and that the position was actually still open for election.179 M. Lollius, recently returned from a successful tour of duty in province Macedonia and now rewarded with a consulship, found himself unexpectedly, and rather awkwardly, serving alone. Two men, Q. Aemilius Lepidus and L. Silvanus, bitterly contested the open consulship. Lollius appealed to Augustus to return to settle the matter, but he refused and summoned the rival candidates to meet him in Sicily.180 Following a stern lecture from him, the chastened senators returned to Rome. When they arrived, riots more violent than the first erupted, only ceasing when Lepidus was finally chosen and sworn in.

Augustus expected trouble in his own provincia, which is why he had an army, but not at home. Dio writes:

Augustus was displeased at the incident, for he could not devote all his time to Rome alone and did not dare leave the city in a state of anarchy; accordingly, he sought for someone to set over it, and judged Agrippa to be most suitable for the purpose.181

M. Agrippa could always be relied upon to carry out his assigned duty unquestioningly and efficiently. It was time to recall him from the East and publicly recognize his special status. Binding his best friend and the Roman Empire’s finest commander closer to him, Augustus offered Agrippa his only daughter, Iulia Caesaris, to be his wife; they were married that year.182 But even the popular Agrippa could not quell the civil unrest in Rome when a protest erupted on the city’s streets over the election of the Praefectus Urbi Feriarum Latinarum Causa (the official who represented both consuls at the Latin Games held in the Alban Hills).183 Agrippa was in no mood to compromise. To settle the matter, he suspended the election altogether and the year passed with the post of Prefect of the City remaining vacant.

The populations of other cities were restless too, using different ways to express their grievances. Augustus decided he was needed in the East (map 6). In his entourage were Tiberius and a young man from Cremona, P. Quinctilius Varus, serving as his quaestor.184 Over the winter of 22/21 BCE, Augustus sailed from Sicily to Greece and visited Sparta and Athens. The Athenians had no particular love of the Romans, having suffered abuses under Sulla, Iulius Caesar and his legate Q. Fufius Calenius, and resentments still festered.185 Augustus was also conscious that the Athenian populace had supported Antonius during the Actian War. When he arrived in Athens there was an act seemingly calculated to cause him personal offence. According to a modern reconstruction of the events recorded by Dio, a statue of Athena on the Acropolis, which had been erected facing the east, was found to have been deliberately turned around to face the west, that is, in the direction of Rome; provocatively, blood had been sprinkled from the mouth and down the front of the statue to create the impression that Athena, the patron goddess of Athens, had spat blood at the Romans.186 Augustus’ response was typically thoughtful but deliberate. He hurt the Athenians in a way they understood – financially. He took from them the administration of Aigina and Eretria, from which they received tribute, and he forbade them to make anyone a citizen in exchange for their money.187 He himself spent part of the winter on Aigina (where he wrote that he was angered by the Athenians’ welcome) and part on Samos.188

During his sojourn on Samos, he received a deputation of Ethiopians. Following her defeat by C. Petronius in Egypt the year before, an outraged Amanirenas Kandake had rallied her people for a counteroffensive. With thousands of warriors, she had marched on Premnis. According to Strabo, Petronius arrived at the fortress before she did and was ready for them.189 In the meantime, he strengthened its defences, making it virtually impregnable to the lightly equipped Ethiopian army. When her emissaries approached the Romans to parlay, they were told to petition Augustus. They proclaimed they did not know who or where he was. Petronius provided them with an escort and delivered them to Samos, where Augustus was residing. He listened to their pleas and acceded to them, even remitting the tribute which Petronius had imposed.

There was, as yet, still no word from the king of Parthia in response to his diplomatic counteroffer. In the spring, Augustus travelled through Bithynia and Asia Minor.190 Appalled to discover that the citizens of Kyzikos (Cyzicus), a major town of Mysia in Anatolia, had rioted, flogged and summarily executed several Roman citizens, he condemned the inhabitants of the city to slavery.191

Map 6. The Eastern Roman Empire.

Arriving in Syria and learning that the people of Tyre and Sidon had rioted violently there too, and with loss of life, he responded with the same harsh punishment.192 Among the kings and potentates loyal to Rome, Augustus reassigned territories following the death of Archelaos the Mede who had ruled them: Iamblichus, the son of Iamblichus, received his ancestral dominion over the Arabs; Tarcondimotus, the son of Tarcondimotus, was given the kingdom of Cilicia, which his father had once held.193 To Herodes he entrusted the tetrarchy of a certain Zenodoros; and to one Mithridates, though still only a boy, he gave Commagene, because its king had put the boy’s father to death.194 It was shrewd politics. As their patronus, Augustus would sponsor and represent each client king’s causes – and, should they arise, grievances – in the Senate or courts in Rome; in return they would support him with troops and matériel as and when called upon to supply them, saving the Romans the additional expenditure.

In Rome, on 12 October, L. Sempronius Atratinus drove a gilded chariot in celebration of his full triumph for victories in Africa through the streets of the city to cheering crowds of onlookers.195

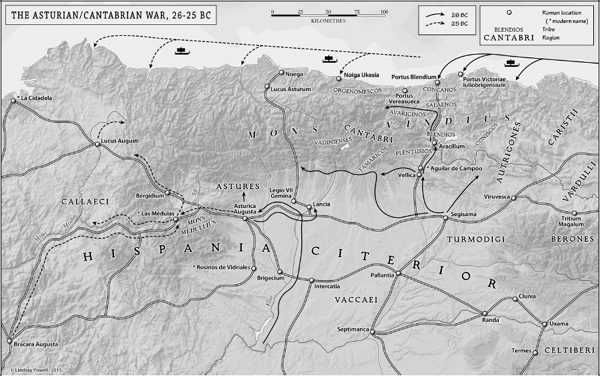

M. Appuleius Sex. f. P. Silius P. f. Nerva

In Syria, Augustus received emissaries from Armenia. They requested his help to replace the incumbent king, Artaxes, with his brother, Tigranes, who had been a refugee in Rome for a decade.196 Augustus agreed to the demand. Assigned the unusual, and potentially risky, mission of taking an army to assist in the ousting of the king of Armenia was his stepson Tiberius.197 Even as Roman troops marched into the country, the Armenians themselves murdered their king.198 Tiberius finally reached the capital city and personally crowned Tigranes (fig. 3).199 The installation of a pro-Roman regent in Armenia tipped the balance of power in the region. Word reached Tiberius that the king of Parthia – apparently ‘awed by the reputation of so great a name’ – was prepared to accept the terms of the settlement proposed three years before.200 Augustus’ stepson now unexpectedly found himself responsible for overseeing the historic recovery of signa and war prisoners in a formal ceremony, which took place on the banks of the Euphrates River (plate 17).201 His stepfather was delighted:

Figure 3. Determining the fate of Armenia was a key point in negotiations between Augustus, his envoy and the Parthian ‘king of kings’. On this coin Augustus claims ‘Armenia Captured’ for the Roman People (see Res Gestae 27 and 29).

Augustus received them as if he had conquered the Parthian in a war; for he took great pride in the achievement, declaring that he had recovered without a struggle what had formerly been lost in battle.202

After such a success it was time to leave the East. Reaching Samos, Augustus decided to spend the winter there. While residing on the Aegean island he received several foreign leaders and even a guest from India.203

C. Petronius, the man who had dealt successfully with an invasion of Ethiopians, had since become unpopular in his own province. A ‘countless multitude of Alexandrians rushed to attack him with a throwing of stones’, writes Strabo, but the mob was no match for well-armed and trained soldiers, and ‘he held out against them with merely his own bodyguard, and after killing some of them put a stop to the rest’.204

Along the southern border of neighbouring province Africa, the Garamantes raided into Roman-held territory. Determined to stop the incursions, the proconsul L. Cornelius Balbus, son of the Jewish financier and consul, launched a punitive campaign against them.205 By temperament an extrovert, he was an attention-seeker given to carrying out acts of bravado. Against the backdrop of the Libyan desert, his dash and daring were on full display. The commander and his legion pursued the enemy to its strongholds to the south. Together they captured fifteen settlements, including Garama (Gherma), ‘the most famous capital of the Garamantes’.206 The Senate was impressed by his exploits, not least because he was not even a Roman, but a native of Hispania Ulterior. Pliny notes that:

Cornelius Balbus was honoured with a triumph, the only foreigner indeed that was ever honoured with the triumphal chariot, and presented with the rights of a Roman citizen; for, although by birth a native of Gades, the Roman citizenship was granted to him.207

The award was both deserved and overdue.

| C. Sentius C. f. Saturninus | Q. Lucretius Q. f. Vespillo | |

| suff. | M. Vinicius P. f. |

The year started badly. Fighting broke out between gangs of supporters for different candidates for the consulship. C. Sentius Saturninus had secured one sella curulis in the Senate House, but the other remained vacant when Augustus declined to accept it.208 Fear gripped the city as thugs committed murders. Sentius was assigned a bodyguard, but he refused it. The Senate dispatched two envoys, accompanied by two lictors each, to seek Augustus’ counsel.209 Augustus chose one of the two men before him, Q. Lucretius Vespillo, which proved a popular choice.

With calm restored in Rome, on 27 March the extrovert Cornelius Balbus, now proudly Roman after his naturalization, celebrated his triumph.210 It was a spectacular event, combining the familiar trappings of the standard military procession augmented this time with the exotic spoils of the African continent. Its unfamiliar place names were painted upon fercula to inform and impress the crowds as the triumphal parade passed by:

There is also this remarkable circumstance, that our writers have handed down to us the names of the cities above-mentioned as having been taken by Balbus, and have informed us that on the occasion of his triumph, besides Cidamus and Garama, there were carried in the procession the names and models of all the other nations and cities, in the following order: the town of Tabudium, the nation of Niteris, the town of Miglis Gemella, the nation or town of Bubeium, the nation of Enipi, the town of Thuben, the mountain known as the Black Mountain, Nitibrum, the towns called Rapsa, the nation of Discera, the town of Decri, the Nathabur River, the town of Thapsagum, the nation of Tamiagi, the town of Boin, the town of Pege, the Dasibari River; and then the towns, in the following order, of Baracum, Buluba, Alasit, Galsa, Balla, Maxalla, Cizania, and Mount Gyri, which was preceded by an inscription stating that this was the place where precious stones were produced.211

Midway through the year, M. Vinicius, the man who had led a successful raid into Germania, was elected suffect consul; he replaced C. Sentius Saturninus, who had reportedly carried out his duties in the severest way.212 In Macedonia the new proconsul, M. Lollius, following a successful term as governor of Galatia-Pamphylia, came to the assistance of his neighbour, Roimetalkes of Thracia (plate 25), who was involved in a war against the Bessi nation.213 By working together the two men defeated their common foe.

At about the same time, news arrived of strife in the Gallic provinces (map 7). Without specifying which nation, Dio says the Galli were quarrelling amongst themselves, and the situation was made worse by raids of Germanic war bands from the Rhineland.214 With Augustus still in transit from the East, Agrippa felt obliged to go to the region in person to deal with it. Having reached Colonia Copia Felix Munatia to assess the situation, Dio cryptically states that Agrippa ‘put a stop to those troubles’.215 The fact is all the more remarkable because Agrippa had not participated in active combat since he had faced the forces of M. Antonius and Kleopatra in 31 BCE.

Solving the ongoing Germanic menace required a different approach. The Rhine River was a permeable natural barrier. There was still no standing army on the left bank to intercept brigands (latrones) when they raided Roman territory in search of rich pickings. As he had done twenty years before, Agrippa travelled to the border country to assess the situation for himself. He found the Ubii once again attacked at their rear by the Suebi, who were moving ever southwestwards and encroaching aggressively on the territory of their neighbours.216 The Ubii sent a deputation to their Roman allies to plead with them to provide sanctuary. Agrippa made an extraordinary decision. ‘By their own consent,’ writes Strabo, ‘they were transferred by Agrippa to the country this side of the Rhenus.’217 He founded for them a settlement called Oppidum Ubiorum (the precursor to modern Cologne). There were conditions attached, however. The Ubii would be relocated specifically to assist the Romans in guarding that section of the Rhine.218 It may have been at this time that work also began on an urban settlement for the Treveri nation, whose territorium extended between the Rhine and Maas rivers.219 Later called Augusta Treverorum, the new city was established on the banks of the Mosella (Moselle) River (and would become modern Trier).220 In combination with the Ubii, some 190 kilometres (118 miles) to the north, Agrippa had effectively established a buffer zone between the people across the Rhine and the Galli to the south, where local allies – rather than Roman troops – provided the soldiers to defend their land from invaders from the north. At least one Cohors Ubiorum Peditum et Equitum and one Ala Treverorum are known.221

Map 7. Tres Galliae, 19 BCE.

Just as the northern border seemed settled, bad news reached Agrippa from the Iberian Peninsula. The Cantabri were in revolt yet again. Dio reports:

It seems that the Cantabri who had been captured alive in the war and sold, had killed their masters in every case, and returning home, had induced many to join in their rebellion; and with the aid of these they had seized some positions, walled them in, and were plotting against the Roman garrisons.222

True to his character, Agrippa immediately departed for Hispania Citerior to evaluate the situation for himself with the Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of Hispania Citerior, P. Silius Nerva.223 What he found was an army demoralized in spirit, fatigued from endless fighting and on the verge of mutiny. When ordered to fallin, ‘his soldiers would not obey him’, writes Dio.224 Now 44 years old, this was the first recorded time in his life that Agrippa had faced open insubordination by his own troops. Even before he could fight the rebels, he first had to restore discipline and revitalize the morale of his own men – and do so quickly. He adopted a ‘carrot and stick’ approach and applied it with his usual patience and persistence.225 ‘Partly by admonishing and exhorting them and partly by inspiring them with hopes,’ writes Dio, ‘he soon made them yield obedience.’226

Now he could turn his attention to the enemy in the foothills. The details of the ensuing war of 19 BCE are entirely lost. The sources imply that it was one of the toughest wars Agrippa ever fought. ‘In fighting against the Cantabri,’ writes Dio, ‘he met with many reverses.’227 His opponents were battle-hardened and motivated, ‘for not only had they gained practical experience, as a result of having been slaves to the Romans, but also despaired of having their lives granted to them again if they were taken captive’.228 There is a story of a mother, who seeing her husband and sons chained and fettered ready for transportation, grabbed a sword and slew them all; another prisoner, summoned before his drunken captors, threw himself upon a pyre.229 Faced with this kind of desperate courage, Agrippa ‘lost many of his soldiers’ and his opponents ‘degraded many others because they kept being defeated’.230 He was particularly disappointed by the performance of Legio I Augusta. Its inability to beat its adversary led Agrippa to strip the unit of the honorific title given it by Augustus – a deeply humiliating act for the troops, who had probably won it for gallantry during the campaign of 26–25 BCE.231 Yet Agrippa was a determined man who would never give up if there was a chance of success. ‘Finally Agrippa was successful,’ records Dio, and ‘he at length destroyed nearly all of the enemy who were of military age, deprived the rest of their arms, and forced them come down from their fortresses and live in the plains.’232 Writing at the time of these events, Strabo noted the achievement:

At the present day, as I have remarked, all warfare is put an end to, Augustus Caesar having subdued the Cantabri and the neighbouring nations, amongst whom the system of pillage was mainly carried on in our day.233

For winning the last Bellum Cantabricum, the Senate voted Agrippa a triumph.234 While the Roman Commonwealth was grateful to the commander, his own reaction hints that he was not particularly proud of the victory:

Yet he sent no communication concerning them to the Senate, and did not accept a triumph, although one was voted at the behest of Augustus, but showed moderation in these matters as was his wont.235

He did, however, accept a corona muralis, the military honour of a crown decorated with turrets, awarded to the first man to scale the wall of a besieged city.236 On coins and statues, Agrippa would now be shown wearing it in combination with his corona navalis.237 His defeat of the Cantabri ended a struggle to conquer the Iberian Peninsula that had lasted two centuries. In gratitude, three altars were dedicated to Augustus on a promontory (perhaps Cape Finsiterre or on Monte Louro) in northwestern Hispania Citerior, called the Sestianae after the man who set them up: L. Sestius Quirinalis Albinianus (suffect consul of 23 BCE) may have replaced P. Carisius as legatus in the region in 19 BCE.238 Cohorts of troops recruited from the Astures, Cantabri and Gallaeci nations entered the service of the Roman army from this time.239

Arriving in Athens on their return from the East, Augustus and his entourage happened to meet the poet Vergil. He was editing the final version of his Aeneid.240 There was only one copy of the epic poem in existence and Augustus was acutely concerned to own it lest anything unfortunate should happen either to the great work or its author.241 He convinced the poet to accompany him back to Italy, ensuring that the boxes containing the handwritten scrolls were kept secure on the return journey. At Megara, the 51-year old poet, who was known to have a weak constitution, caught a fever.242 His condition worsened as the ship sailed across the Adriatic Sea. Upon landing at Brundisium, on 21 September he died. Vergil had left clear instructions with his executors for his poem to be burned upon his death, but Augustus countermanded the order, arranging for it to be published instead, even with the incomplete edits.243 The Aeneid was too important a document to the leader of the Roman world to consign to oblivion. Among many evocative scenes, in particular, in Book 1 of the great work were the climactic words spoken by Jupiter to the itinerant hero Aeneas:

To these I give no bounded times or power,

but empire without end. Yea, even my Queen,

Juno, who now chastiseth land and sea

with her dread frown, will find a wiser way,

and at my sovereign side protect and bless

the Romans, masters of the whole round world,

who, clad in peaceful toga, judge mankind.

Such my decree!244

Hearing that Augustus was in Italy, a group of praetors and tribunes left the city to greet him in Campania, the first time it had been done. 245 On the night of 12 October, Augustus entered Rome bringing with him the precious Aeneid and the signa received from the Parthian king.246 The next day, he ordered sacrifices to be made. His arrival from Asia was an occasion for public celebration. The Senate voted him several honours, all but two of which he refused.247 Firstly, he accepted an altar to Fortuna Redux to be erected beside the Temple of Honour and Courage (Honos et Virtus) at the Porta Capena (fig. 4), which was dedicated on 15 December of that year; and, secondly, he permitted the day of his return to be celebrated as an annual holiday, which came to be known as the Augustalia.248 Augustus ‘rode into the city on horseback and was honoured with a triumphal arch’.249 Not since Actium had he felt such a deep sense of military accomplishment. A series of coins issued at the time expresses the princeps’ evident pride in the result, achieved entirely without bloodshed.250

The recovered signa were taken to the Capitolium and placed in the old Temple of Mars Ultor (fig. 5).251 It would suffice for the time being, but such important artefacts would need a grander home for their display and veneration. Augustus chose this year to break ground on a vast, new precinct behind the Forum Romanum and adjacent to the Forum Iulium. He paid 100 million sestertii to buy the land from its private owners, but soon discovered that even he could not acquire all the land he wanted for the project.252 It would take years to complete the construction work on the landmark project.

Figure 4. Returning from the East in 19 BCE, the Senate voted Augustus an altar to Fortuna Redux (the goddess who oversaw safe returns from dangerous journeys) beside the Porta Carpena, Rome. The annual Augustalia was held to mark the occasion.

Figure 5. The military standards that were recovered from Parthia under Augustus’ auspices in 20 BCE were kept temporarily in the round Temple of Mars Avenger in Rome while the Forum Augustum was constructed.

Horace, now the favourite poet and a friend of Augustus, expressed in verse the celebratory mood of the times:

Thy age, great Caesar, has restored

To squalid fields the plenteous grain,

Given back to Rome’s almighty Lord

Our signa, torn from Parthian fane

Has closed Quirinian Ianus’ gate,

Wild passion’s erring walk controll’d,

Heal’d the foul plague-spot of the state,

And brought again the life of old,

Life, by whose healthful power increased

The glorious name of Latium spread

To where the sun illumes the east

From where he seeks his western bed.253

Among rewards and recognitions issued, he promoted Tiberius to the rank of ex-praetor and to his younger brother, Nero Claudius Drusus, he granted the privilege of standing for public office five years earlier than stipulated – the same gift given to his older brother five years previously.254

Under his auspices, Augustus and his subordinates had achieved much over the previous decade. Cyprus and Gallia Narbonensis, now pacified, had been passed over to the Senate to administer. The project to subjugate the entire Iberian Peninsula had finally been completed after two centuries of struggle. New territory had been added in the Italian Alps and in Anatolia. Enemies who had invaded from the Rhineland and Ethiopia had been punished. A rebellion had been quelled in Aquitania. Roman troops had explored deep into Arabia. Under the Pax Parthorum, Rome’s eastern nemesis changed from an ongoing threat into a partner in peace. Augustus had been acclaimed an unprecedented nine times. Yet there was still much to be done. Across the German Ocean the island of Britannia beckoned, and in the Orient lay other prizes:

O shield our Caesar as he goes

To furthest Britannia, and his band,

Rome’s harvest! Send on Eastern foes

Their fear, and on the Red Sea’s strand!255

The deployment of the army reflected the strategic imperatives of the previous decade (table 1). There was a high concentration of manpower in the West: nineteen legions (67 per cent) out of twenty-eight were spread between the Iberian Peninsula, Gaul and the Balkans. With the subjugation of the Astures and Cantabri, resources could be redirected to military projects elsewhere. Where was yet to be decided.

In the meantime, Augustus consolidated his own position politically under the guise of ensuring social cohesion:

And inasmuch as there was no similarity between the conduct of the people during his absence, when they quarrelled, and while he was present, when they were afraid, he accepted an election, on their invitation, to the position of supervisor of morals for five years, and took the authority of censor for the same period and that of consul for life, and in consequence had the right to use the twelve fasces always and everywhere and to sit in the curule chair between the two men who were at the time consuls.256

Table 1. Dispositions of the Legions, Summer 19 BCE (Conjectural).

| Province | Units | Legions |

| Hispania Citerior | 8 | I Augusta, II Augusta, IIII Macedonica, V Alaudae, VI Victrix, VIIII Hispana, X Gemina and XX |

| Aquitania / Gallia Comata (Celtica) / Gallia Belgica | 3 | XVII, XIIX, XIX |

| Gallia Cisalpina | 4 | XIII Gemina, XIV Gemina, XVI Gallica, XXI Rapax |

| Illyricum | 4 | IIII Scythica, VIII Augusta, XI, XV Apollinaris |

| Galatia-Pamphylia | 2 | V, VII |

| Syria | 3 | III Gallica, VI Ferrata, X (Fretensis) |

| Aegyptus | 3 | III Cyrenaica, XII Fulminata, XXII Deiotariana |

| Africa | 1 | III Augusta |

Sources: Appendix 3; Lendering (Livius.org); M’Elderry (1909); Mitchell (1976); Sanders (1941); Šašel Kos (1995); Syme (1933).

Augustus’ power was now confirmed as summum imperium auspiciumque, superior to all other consuls, proconsuls or magistrates of equal rank to his.257 He could intervene in any and all provinces of the Empire – even those under the management of the Senate – and exercise supreme military command there.

At the end of December, however, Augustus’ ten-year imperium over his vast province would expire and with it control of the army.258 The question for Augustus and the Senate was what would happen next?