It’s your business and your budget—which means the size of your paycheck is entirely up to you. But while the freedom of setting your own salary sounds great in theory, in practice most business owners find it a tough call. Should you pay yourself what you need to cover expenses? What your business can afford? The salary you left behind to launch your business?

Your best bet is to factor in all three—and a whole lot more. Obviously, you want your business to succeed and may be willing to accept a temporary drop in income to make that happen. Or if you’re side-gigging in addition to a day job, perhaps you can afford to put the profits right back into your business instead of taking a larger paycheck. On the other hand, paying yourself far less than you’re worth, or nothing at all, paints an unrealistic picture of the viability of your business for both you and any investors you hope to appeal to now or in the future.

What You Need

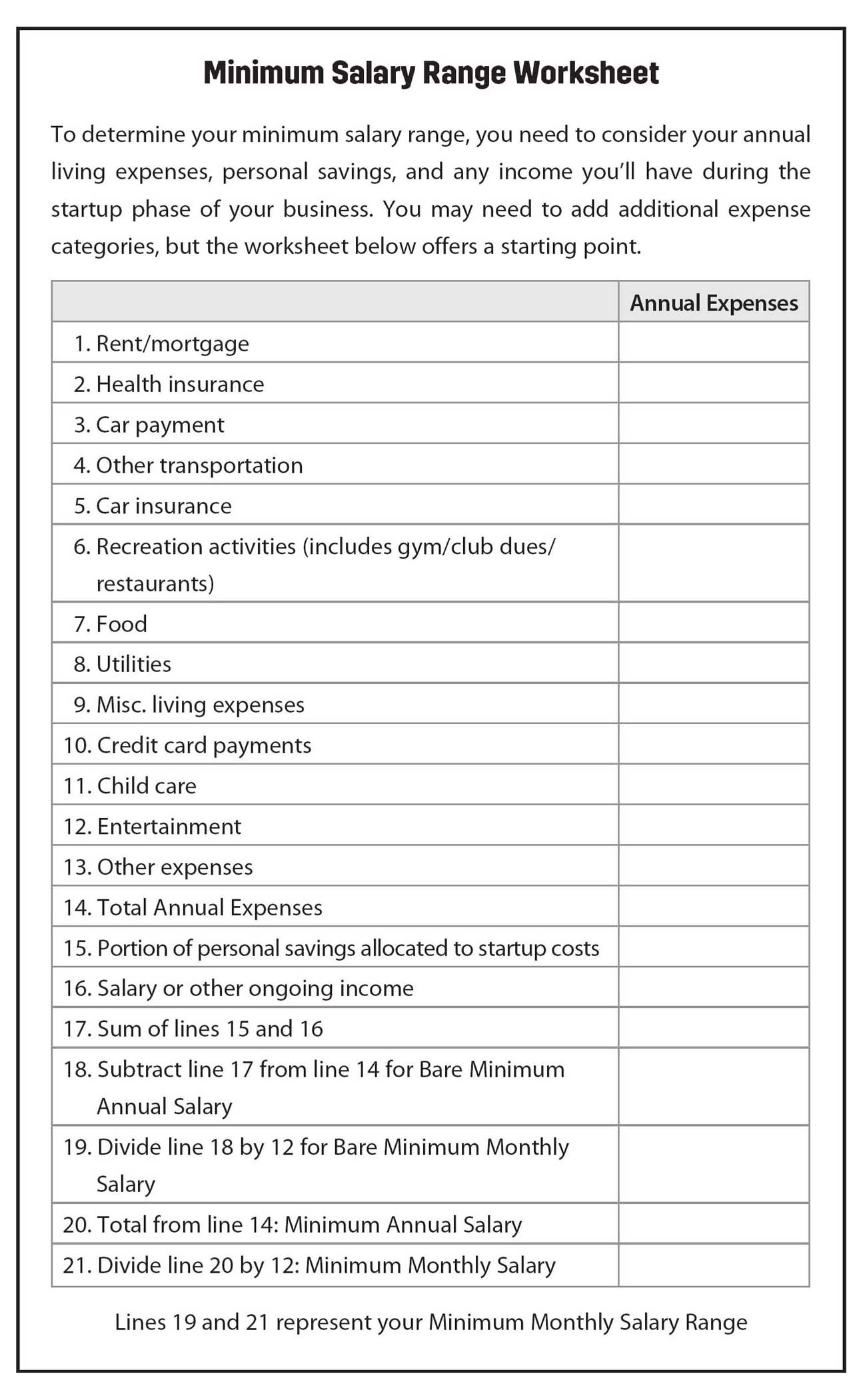

Your salary needs will depend on your living expenses, financial situation, and comfort level with drawing on personal savings. The first step in planning your pay is to put together a comprehensive list of your expenses. Be sure to include all annual, quarterly, and monthly expenses, including your rent or mortgage; car payments, car insurance, and gasoline bills; credit cards with outstanding balances; gym membership; grocery bills; and everything else you’ll spend money on in the coming year. Underestimating personal expenses is one of the biggest mistakes new business owners can make. If you slip into the red, chances are your business will, too.

aha!

Talk to your accountant about whether a deferred salary—setting a salary but not collecting it until your company becomes profitable—is an option for your company. The salary becomes a liability for the company, offsetting taxable future profits, which you’ll get back with interest when revenue comes in.

When you’ve computed your annual personal expenses, divide by 12 to come up with the monthly salary you’ll need to receive to keep from dipping into your savings. Next, decide what portion of your savings you’ll feel comfortable drawing on during the early stages of your company—these must be savings separate from the funds you’ll use to launch your business. If you plan to keep your job, add your annual salary to the personal savings figure. Subtract this number from your total annual personal expenses, and divide by 12. This gives you the minimum monthly salary you’ll need even if you choose to supplement your startup salary with personal savings or employment income. Now you have a range that runs from the minimum salary needed to cover all your personal expenses to the bare minimum salary you can afford to take by supplementing your income—your minimum salary range. (To figure out your minimum salary, use the worksheet on page 740.)

![]() Taxing Matters

Taxing Matters

Tax ramifications are another factor to keep in mind when deciding what to pay yourself and how to structure your compensation, especially considering the federal tax reform that was implemented in 2018. Your tax situation was determined when you chose a business structure (see Chapter 9).

If you’re a sole proprietor, for instance, the IRS considers you and your company to be a single entity. Profits from your business are funneled directly onto your tax return as taxable personal income, whether you draw them out as a salary or leave them in your business account as cash holdings. Similarly, partnership profits flow directly through to the partners, who report their share of the business’ profits or losses on their tax returns—again, whether the profits are left in the business or drawn out as compensation. In both cases, profits retained in the business and later withdrawn by a sole proprietor or partner in subsequent tax years are not taxed again. However, sole proprietors and partners are liable for self-employment tax, which was 15.3 percent in 2018. .

On the other hand, if you form a corporation, your business is a separate legal entity and must file its own return and pay taxes on any profits earned. On the plus side, since the IRS views you and any other owners of the business as employees, any salary you draw is considered a deductible expense.

Corporations also have the option of distributing profits in the form of dividends, typically as cash or company stock. But dividends distributed to shareholders are taxed twice—once as corporate profit and again as income for the recipient—so salaried compensation is a far more tax-efficient way of taking profits from your business. However, the IRS is all too aware of the incentive to distribute profits as salaries and requires that executive salaries be “reasonable.” The IRS prohibits salary deductions it identifies as being “disguised dividends” and assesses hefty penalties for the transgression. Since the tax code doesn’t provide a clear definition of reasonable compensation, it’s wise to check with your tax advisor to ensure your salary is in line with the company’s revenues and expenses or with those at comparative companies.

There are two equally valid methods for computing your market worth:

1. Open market value. Given your experience and skills, what would you be paid by an employer in today’s market? While this salary won’t take into account the additional time you’ll put into a startup, the income you’re sacrificing to start your business is a useful benchmark in setting your salary.

2. Comparable companies. What do the owners of similarly sized firms in the same industry and geographic region pay themselves? To get comparable salaries, check with trade associations, other entrepreneurs in your industry, or the local Small Business Development Center.

Neither of these methods takes into account the additional work you’ll be taking on as an owner nor the risk you’re taking in starting a business. Some entrepreneurs boost market-worth-based salaries by 3 to 5 percent to offset the added responsibilities and risk. Others look at the potential long-term advantage of owning a successful business as compensation for these factors.

warning

Before you boost your compensation, check your balance sheet to ensure that the increase in the rest of your overhead hasn’t outpaced the bump in revenue. A bump beyond inflation—such as an office rent hike or new hire—may require adjusting your plans for a salary boost.

What Your Business Can Afford

Once you know the salary you need and deserve, it’s time to balance those figures against your business’ finances. You’ll need to check the cash-flow projection in your business plan to ensure you have enough money coming in to cover your own draw, in addition to your other operating expenses. In an ideal scenario, your cash flow will have a surplus large enough to pay your market-worth salary, reinvest funds in the business, and leave a little margin for error. Unfortunately, that’s unlikely. Since most startups initially operate at a loss—generally for at least six months and possibly for as long as two years—you should plan to start with compensation within the minimum salary range. You can ratchet up toward a market-worth salary as your business reaches a break-even point and continues to grow.

Because your business income may ebb and flow initially, a base salary with a bonus structure that kicks in when your business reaches the break-even point is usually the best way to handle owner’s compensation in an early-stage company. You might, for example, decide that when your business moves into the black, you’ll take a percentage of profits every fiscal quarter as a bonus. Bonus percentages range widely, depending on an owner’s goals for the business, personal financial needs, and philosophy on reinvesting business earnings. But while your aim may be to reach your market-worth salary rapidly, it’s a good idea to leave some profits in your business as a safety net and to fund future growth.

tip

Planning to take no salary and funnel your profits back into your business? Before you go that route, be sure to take retirement planning into account. The amount you can contribute to an IRA, Keogh, or other qualified retirement plan is based on a percentage of eligible compensation. Without earnings, you won’t be able to fund your retirement with pretax dollars.

When the business reaches a point of consistent profitability, it’s time to re-evaluate your salary. Typically, this means taking a salary increase equal in percentage to the business’ annual growth rate and then reinvesting the remaining profit in your business. But as with your bonus structure, there is no silver-bullet equation for determining the appropriate salary hike. You’ll want to factor in the nature of your industry and your business goals. For example, if you’re in a turbulent or cyclical industry, you may want to retain the quarterly bonus structure and the flexibility it affords. Or if your business has the potential for rapid growth, you may want to forego the salary boost and use the extra capital to fund new products, expansion plans, or marketing initiatives.

Figure 40.1. Minimum Salary Range Worksheet

![]() Added Value

Added Value

Salaries, bonuses, and dividends aside, here are some other ways to get value from your business:

![]() Hire family members. Hiring your spouse, son, or daughter to work for you can help you keep money in the family. The caveat? The family member must actually perform work for your company, not just collect a paycheck.

Hire family members. Hiring your spouse, son, or daughter to work for you can help you keep money in the family. The caveat? The family member must actually perform work for your company, not just collect a paycheck.

![]() Pick up perks. Club or association memberships, company cars, travel, and other attractive perks are among tax-deductible expenses business owners can write off—provided they have a legitimate business purpose. If you’re caught disguising personal expenses as business ones, you’ll incur hefty IRS penalties, so check with your accountant first.

Pick up perks. Club or association memberships, company cars, travel, and other attractive perks are among tax-deductible expenses business owners can write off—provided they have a legitimate business purpose. If you’re caught disguising personal expenses as business ones, you’ll incur hefty IRS penalties, so check with your accountant first.

![]() Be a borrower. You can take loans from your company, as long as it’s documented in writing, includes a market-rate interest and repayment schedule.

Be a borrower. You can take loans from your company, as long as it’s documented in writing, includes a market-rate interest and repayment schedule.

Whatever you decide in the early phase of your business, plan to reassess your compensation every six months. As your business evolves, its cash-flow model and capital needs may change dramatically—as may your own. A regular assessment enables you to adjust accordingly.