Thou too, sail on, O Ship of State!

Sail on, O Union, strong and great!

Humanity with all its fears,

With all the hopes of future years,

Is hanging breathless on thy fate!

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The story of a flood that destroyed the world in which human and animal life was saved from extinction by a hero with a boat is almost universal in the world’s treasury of traditional literature. The (global) flood story, whose central preoccupation is the frailty of the human condition and the uncertainty of divine plans, would certainly feature as a thought-provoking entry in any Martian Encyclopaedia of the Human World. Its rich theme has inspired many thinkers, writers and painters, the topic moving far beyond the borders of scripture and the sacred to become an inspiration for modern opera and film, in addition to literature.

Many scholars have tried to collect all the specimens in a butterfly net, to pin them out and docket them for family, genus and species. Flood Stories in the broadest sense (which are sometimes booked under Catastrophe Stories, for not all possible disasters are floods) have been documented in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Syria, Europe, India, East Asia, New Guinea, Central America, North America, Melanesia, Micronesia, Australia and South America. The scholars who have contributed most to this endeavour have produced varying totals, somewhere around three hundred all told, and a range of publications will enable the devotee to sample them in abundance. Some of these narratives reduce everything to a couple of sentences, others blossom into powerful and dramatic literature, and looking them over reinforces the impression that any culture that cannot muster some form of flood story is in the minority.

The collection and comparison of traditions is always fascinating, and creating and pruning a family tree of flood narratives is probably as enticing as any other such project. It is the breadth and overall variety, however, that is more significant than any fundamental similarity. After all, the forces of nature, including rivers, rain and sea (alongside earthquakes, whirlwinds, fire and volcanoes), are irresistible by man when they are roused and are likely to underpin much traditional narrative, while in any flood, however disastrous, certain individuals always survive, usually those with boats. There is no need to strive for a complex web of origin, dissemination and interrelations on the broadest scale. One must always reckon, too, with the ‘natural’ flow of uncontaminated narrative being interrupted or influenced in a specific way at a specific moment, such as through Bible teaching by missionaries.

The central example from the collector’s standpoint represents a unique case, however, where influence and dissemination are undeniable and have been of the greatest global significance. The story of Noah, iconic in the Book of Genesis, and as a consequence, a central motif in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, invites the comparative mythologer’s greatest attention. In all three scriptures the Flood comes as punishment for wrongdoing by man, part of a ‘give-up-on-this-lot-and-start-over’ resolution governing divine relations with the human world. There is a direct and undoubted Flood continuum from the Hebrew Old Testament to the Greek New Testament on the one hand and the Arabic Koran on the other. Since the Victorian-period discoveries of George Smith it has been understood that the Hebrew account derives, in its turn, from that in Babylonian cuneiform, much older, substantially longer, and surely the original that launched the story on its timeless journey. This book focuses on the first stage of this process, looking at the various Mesopotamian stories that survive on cuneiform tablets, and investigating how it came about that the story came into our own world so effectively.

Such an approach entitles the researcher to avoid entirely the question as to whether there ever ‘really was a Flood’. People have, however, long been concerned with that very question, and been on the lookout for evidence to support the story, and I imagine all good Mesopotamian archaeologists have kept the Flood at the back of their mind, just in case. In the years 1928 and 1929 important discoveries were made on sites in Iraq that were taken to be evidence of the biblical Flood itself. At Ur, for example, deep excavation beneath the Royal Cemetery disclosed more than ten feet of empty mud, below which earlier settlement material came to light. A similar, nearly contemporaneous, discovery was made by Langdon and Watelin at the site of Kish in southern Iraq. To both teams it seemed inescapable that here was evidence of more than ancient flooding, but of the biblical Flood itself, and Sir Leonard Woolley’s fluent lectures round about the country, backed up by his versatile pen, certainly came to promote the idea that at Ur they had found proof that Noah’s Flood had really taken place.

Similar deposits were identified at other archaeological sites, but in due course doubts were raised whether all such empty layers were really archaeologically contemporary, or indeed whether they were all water-deposited. In recent times this sort of would-be tangible evidence has fallen out of consideration. Certainly strata of empty mud confirm that human habitation in ancient Iraq was subject to disastrous and destructive flooding, and in general background terms such discoveries do much to enhance our appreciation of the extent to which ancient Mesopotamia was, in fact, vulnerable in this way, but few today would claim such discoveries concern the Flood described in the Book of Genesis. Sir Leonard, apparently, could hardly be surpassed as a persuasive speaker once he got going on the subject of Ur; Lambert told me in a rare confessional moment that it was as a schoolboy on the edge of his seat in a Birmingham cinema, listening to Woolley lecturing about discoveries, that he determined on his own life’s work as an Assyriologist.

In recent times the hunt for archaeological flood-levels for their own sake has rather fallen out of fashion, while further such discoveries depend on evidence that can only come from very deep and extensive excavations which are hardly practical today. In more recent times scholars have turned to geological rather than archaeological investigation, pursuing data about earthquakes, tidal waves or melting glaciers in the hunt for the Flood at a dizzying pace, but it is far beyond the scope of this book to follow in their footsteps.

Psychologically it is not surprising that a flood myth should be deeply embedded in the Mesopotamian psyche, for it derived from and reflected the very landscape in which they found themselves. Their dependence on the Tigris and Euphrates waters was absolute and inescapable, but the awe-inspiring emptiness of the deep sky above them, the suddenness of storm and the tangible powers of the ancient gods like the Sun, the Moon and the god of the Storm meant that even the most sophisticated individuals were never far from the reality of nature’s forces. The flood, an ungoverned power that could sweep civilisation before it like a modern tsunami, was for sure no safe and comfortable bogeyman with which to frighten children but something that enshrined remote memory of a real disaster or disasters. Probably some version of the story had been told for millennia.

Culturally the Flood functioned as a horizon in time, according to which crucial events preceded it or followed it. Great Sages lived ‘before the Deluge’, and all the elements of civilisation were bestowed on mankind thereafter. Very occasionally in cuneiform literature the use of the phrase, ‘Before the Flood’, which acquires the ring of cliché, reminds one ever so slightly of the expression ‘Before the Great War …’

The universal flood was intended as an efficient kind of ‘new broom’ approach that would allow the gods to start recreating more appropriate forms of life afterwards in a clean and empty world. The god Enki (clever, humorous, rebellious) is appalled at the proposal and seemingly alone in anticipating the consequences, so he picks out one suitable human being to rescue human and other life. The Flood Story was thus the very stuff of oral literature. Its central theme affected everybody and all listeners. All men and women knew that, if the gods so wished it, they were doomed; and that stoppage of the very life-giving water of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers would be their undoing if that happened, or if it swelled into a monstrous, all-encompassing water of chaos. The Flood Story is full of fearful drama, human struggle and, at the last minute, Hollywood-like, escape.

Many Mesopotamian stories, in Sumerian or Akkadian, bear indications that they derive from an older time before such compositions were written down. Repetition of key passages, for example, makes a long story easier to remember and promotes familiarity in listeners who might well come to ‘join in’ at certain parts, as small children do when a favourite book is read and re-read. Quite soon after writing had reached the point of recording language in full, at the beginning of the third millennium BC, we see that narrative concerning the gods came to be written down.

Very early clay tablets from southern Iraq contain narrative literature in which the gods feature, although to a large extent these first examples still defy translation. The Flood Story, in contrast, does not seem to have made it ‘into print’ at such an early date. The earliest tablets with any part of the story appear in the second millennium BC, a thousand years or more after the first experiments with writing on clay. We can only imagine how Sumerian and Babylonian storytellers might have spun tales of the Great Flood in the meanwhile, for it must long have been a staple of their craft. By the early second millennium, however, when it does start to appear in written form, we do not have just one Mesopotamian Flood Story, but separate compositions in which the Flood is a central component. This in itself is an indication of the antiquity of the subject, for the power and drama of the flood narrative was unending, preoccupying poets and storytellers as long as the cultures of Mesopotamia endured, if not beyond.

The Mesopotamian Flood Story surfaces in three distinct cuneiform incarnations, one in Sumerian, two in Akkadian. These are the Sumerian Flood Story, and major narrative episodes within the Atrahasis Epic and the Epic of Gilgamesh respectively. Each incarnation has its own flood hero. This means that it is only partly appropriate to speak of a ‘Mesopotamian Flood Story’ as such, for there are important differences between them, although the essence of the story is common to all three. Within these three traditions, different versions of the flood story text were in circulation, some substantially different, where format, number of writing columns or even plot elements could vary as well as language. What we call the Atrahasis Epic was undoubtedly popular, appearing in many formats, never to be fully ‘canonised’, whereas the Epic of Gilgamesh, did eventually become fixed into an agreed literary format. First-millennium Gilgamesh tablets with the Flood Story from the Royal Library at Nineveh are true duplicates of one another that literally tell one and the same story. There are no Atrahasis versions of the Mesopotamian Flood Story so far from the first millennium BC. We need some.

Flood Story tablets distribute themselves over the following broad time periods:

| Old Babylonian | 1900–1600 BC |

| Middle Babylonian | 1600–1200 BC |

| Late Assyrian | 800–600 BC |

| Late Babylonian | 600–500 BC |

Here are the nine known tablets which contribute to our picture of the Mesopotamian story of the Flood and aid us in understanding and appreciating the newly found Ark Tablet.

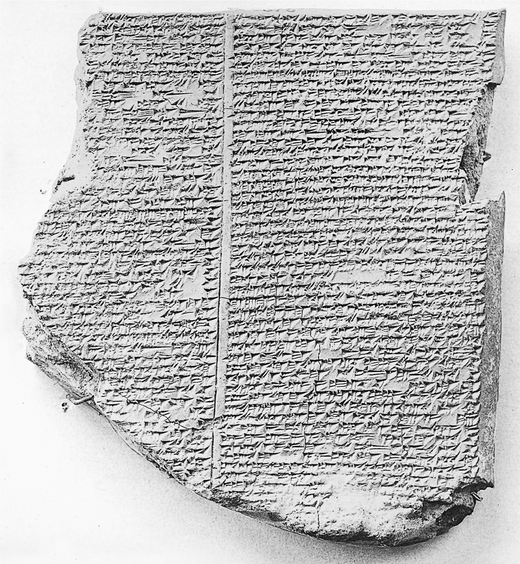

The Sumerian account of the Flood is found on a justly famous cuneiform tablet in the University Museum in Philadelphia. Once it had three columns of writing on each side, but approximately two-thirds is missing altogether so our grasp of the whole remains shaky. It was written down in about 1600 BC at the Sumerian city of Nippur, an important religious and cultural centre where many literary tablets have been excavated.

The Sumerian Flood Story tablet from Philadelphia.

Although this story comes to us in the Sumerian language there are features about the wording – such as odd verb forms – that led its translator, Miguel Civil, to conclude that the theme of the Flood which destroys mankind probably does not belong within the main body of Sumerian literary traditions. While it does look as if this Sumerian Flood Story account derives from a Babylonian account, its source must have been a version that we have never seen, and it is worth pointing out that separate Sumerian versions of the story, unknown to us, might have been in circulation too.

In this tablet, the great gods, long after the founding of the cities, decide on the destruction of the human race (although we don’t know why), despite the pleas of the creator-goddess, Nintur. It fell to King Ziusudra to build the boat and rescue life, which he did successfully, deservedly becoming immortal:

Then, because King Ziusudra

Had safeguarded the animals and the seed of mankind,

They settled him in a land overseas, in the land of Dilmun,

where the sun rises.

Sumerian Flood Story: 258–60

For a long time the Sumerian Flood Story tablet was unique, but a second fragment has been found in the Schϕyen Collection in Norway. This tells us that King Ziusudra, whom it prefers to call ‘Sudra’, was a gudu-priest of the god Enki. The hero Ziusudra was thus king and priest together, a joint appointment that was probably often the case in early times. The Instructions of Shuruppak, already mentioned in Chapter 3, considered Ziusudra’s father to be a character called Shuruppak, providing a convincing-looking lineage:

Shuruppak, son of Ubar-Tutu

Gave advice to Ziusudra, his son.

Shuruppak was in fact a Sumerian city. The indispensable Sumerian King List, which records kings and reign-lengths before and after the Flood, tells us that Ubar-Tutu was king in the city of Shuruppak for 18,600 years and the last to rule before the Flood, but mentions neither Shuruppak – otherwise known to be a wise man and sometimes called the ‘Man from Shuruppak’ – nor Ziusudra! In another document called the Dynastic Chronicle, however, Ubar-Tutu is succeeded at Shuruppak before the Flood by his son Ziusudra, thus confirming that he was the hero who underwent the Great Deluge. This is a sizeable can of worms, but I think we can excuse our valiant chroniclers for getting confused about dates and lineage for kings who lived before the Flood, even though, according to Greek testimony, important cuneiform texts had been buried before the Flood for safekeeping.

The name Ziusudra is very suitable for an immortal flood hero, since in Sumerian it means something like He-of-Long-Life. The name of the corresponding flood hero in the Gilgamesh Epic is Utnapishti, of roughly similar meaning. In fact, we are not sure whether the Babylonian name is a translation of the Sumerian or vice versa.

The Atrahasis Epic is a three-tablet literary production of which no one should speak slightingly, for it is among the most significant works of Mesopotamian literature and wrestles with timeless human issues. The story of the Flood and the Ark for which it is best known is only part of a much wider narrative. The whole would make, I dare say, a corking opera.

The curtain rises on a very strange world. Man has not yet been created, and the junior gods are obliged to do all the necessary work. They mutter and rebel, finally burning their tools. Their complaint is not without justification; the senior gods will see to it that man, Lullû, is created instead to do the work. The birth goddess Mami, also known as Nintu and Bēlet-ilī, is called in, but she declares that she cannot create this being alone, so the god Enki announces to all that their fellow god We-ilu will be slaughtered and man created (see the quotations in Appendix 1). Mankind has now been doing the work for the gods, but, at the same time, reproducing itself enthusiastically without being subject to death. In their profusion mankind is extremely noisy. As Enlil puts it to his fellow gods,

“The noise of mankind has become too intense for me,

With their uproar I am deprived of sleep.”

The dreadful racket warrants a plague to wipe out mankind altogether. Ea (Sumerian Enki), one of the senior gods responsible for the creation of man, thwarts this plan. Enlil’s frustration increases and this time he resolves to wipe out human beings by starvation, so he withholds the rain. Again it is Ea who intervenes and reinstates the rain and restores life. Enlil’s third plan is to send an annihilating flood once and for all, and it is to circumnavigate this disaster that Ea instructs Atra-hasīs to build his ark and save human and animal life. The gods, ultimately, are pleased at Ea’s intervention. The Atra-hasīs family members are made immortal and human life is allowed to go on, although death is now added to the mixture, and barrenness, celibate priestesses and childbirth mortality are instituted for the first time to keep a cap on numbers.

To our minds, noise abatement as justification for the total annihilation of life looks a bit over the top. There can be no doubt, however, that this was the reason: seething human clamour had reached an intolerable point. Enlil’s irritation in Atrahasis always makes me think of old people in deckchairs after lunch on the beach annoyed by other peoples’ children and radios; it is a far cry from the moral standpoint of the Old Testament. Some Assyriologists have argued, unconvincingly, that the key Babylonian word, rigmu, ‘noise’, might here be a euphemism for bad behaviour but the real issue at stake is overpopulation. The noise is due to excessive numbers of persons and the Flood is a remedy for an antediluvian world situation in which none of the population ever actually had to die. Enlil meant what he said, though: there are cuneiform spells to quieten a single fractious baby whose rigmu, ‘noise’, disturbs important gods in heaven to the point of ungovernable annoyance all over again. The Flood Story is, therefore, woven into Atrahasis as one episode in a structured sequence. The hero of the day is Atra-hasīs himself, whose name means Exceedingly-wise.

The most famous copy of the whole Atrahasis epic in Akkadian was written by a scribe called Ipiq-Aya, who lived and worked in the southern Mesopotamian city of Sippar in the seventeenth century BC. The Assyriologist Frans van Koppen has not only settled the long-running problem of how to read this great man’s name but has investigated his biography too. As a young man he wrote out the whole of the Atrahasis story on three large cuneiform tablets between 1636 and 1635 BC, carefully recording the date and his own name. Ipiq-Aya would be put out to learn that the results of his labours are scattered today between the museums of London, New Haven, New York and Geneva. Together the three tablets originally contained 1,245 lines of text, of which we have all or part of about 60 per cent.

The crucial episode about the Ark and the Flood occurs in Ipiq-Aya’s Tablet III, referred to regularly in this book as Old Babylonian Atrahasis. This tablet is now in two pieces. The larger, known as C1, might just possibly join C2 if they could ever be manoeuvred into the same room, but the former is in the British Museum and the latter in the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Geneva. One day I will try out the join …

There are six further tablets or pieces of the Akkadian Atrahasis Epic that survive from the Old Babylonian period, which, though obviously the ‘same story’, reveal four distinct versions. Only one of these tablets happens to contain Flood narrative.

This recently published tablet, also in the Schøyen Collection, is textually strongly independent of those previously known, and earlier in date than Old Babylonian Atrahasis by about a hundred years. This is the passage in this tablet that is relevant here:

“Now, let them not listen to the word that you [say],

The gods commanded an annihilation,

A wicked thing that Enlil will do to the people.

In the assembly they commanded the Deluge, (saying):

‘By the day of the new moon we shall do the task.’ ”

Atra-hasīs, as he was kneeling there,

In the presence of Ea his tears were flowing.

Ea opened his mouth,

And said to his servant:

And that, tantalisingly, is the final line of Old Babylonian Schϕyen. Judging by the well-known continuation of the story, the subsequent tablet written by this scribe – if we had it – would have begun with the same lines that open the Ark Tablet.

This important tablet fragment was excavated at the site of Ugarit (Ras Shamra) in modern Syria, and is still the only piece of the Flood Story to have come to light at a site outside of Iraqi Mesopotamia itself. Its presence there is a good example of how literature and learning was exported from the centre of the cuneiform world to important cities of the Middle East where Babylonian was not the predominant local language. It has been suggested that Middle Babylonian Ugarit, in contrast to the other Atrahasis accounts, is written in the first person, but the lines that seem to suggest this are in direct speech and the narration is in the third person. The text as far as we have it is also quite distinct from other versions.

This tablet fragment, like Old Babylonian Sumerian, was also excavated at the city of Nippur, southern Iraq, and is now kept in the University Museum, Philadelphia.

This first-millennium text in Assyrian script gives us a glimpse of a different and abbreviated recounting of the story. It also has the peculiarity of having been copied from a tablet that was damaged in one or two places, marked as such by the scribe (as described in Chapter 3).

This is the historic flood fragment excavated at Nineveh by George Smith and understandably taken by him to be part of the Gilgamesh story. The abbreviation by which it is classified in the British Museum, DT 42, commemorates the generosity of his sponsor, the Daily Telegraph newspaper.

The second Akkadian incarnation of the Flood Story is at once the most famous and the least ancient. It occurs in the Epic of Gilgamesh, so far the only Babylonian composition to make it as a Penguin Classic and unquestionably the crown jewel of Akkadian literature. In this very polished work the story of the Flood and the Ark is incorporated as a single episode in Tablet XI within a much longer literary achievement, which in its completed form ran to twelve separate tablets. From our perspective the Flood narrative originally formed part of a completely independent story that was central not to the life and times of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, but rather to the behaviour and near-destruction of the human race at large, not to mention the animals. Within the Gilgamesh Epic as a whole the recycled story has felt to many readers today to be something of an afterthought.

Tablet XI of the Gilgamesh Epic in which George Smith read the Flood Story for the first time in 1872; a reproduction of the first published photograph.

While it is certain that the Late Assyrian Gilgamesh Ark-cum- Flood narrative derives from earlier accounts written in the second millennium BC, there is no known example of an Old Babylonian Gilgamesh story that deals with these iconic events. All our Flood Story sources from that time belong to Atrahasis. We will consider in Chapters 7 and 8 the extent to which our earlier second-millennium Ark Tablet, likewise an example of Atrahasis, stands behind the latter first-millennium account in Gilgamesh XI.

In the Assyrian Gilgamesh story the hero of the Flood is called Utnapishti. This name means I-found-life (or He-found-life), and was directly inspired by, if not meant to be a translation of, the Sumerian name Ziusudra. When he appears in the Gilgamesh story he is called either Utnapishti, son of Ubar-Tutu, or the Shuruppakean, son of Ubar-Tutu.

In none of the surviving copies of Atrahasis (as far as I can see) is the hero ever referred to as a king. Utnapishti, too, is never referred to as a king, and there is no real reason to think he was one, except for one point in the Flood Tablet where a palace is suddenly mentioned (discussed later on), but this, in my view, has been stuck into the text, reflecting contamination from the historical chronicle tradition where Ziusudra – with whom Utnapishti is identified – really was a king.

The relationship between Enki and Atra-hasīs or Ea and Utnapishti is conventionally portrayed as that between master and servant. If neither Atra-hasīs nor Utnapishti was a king but, so-to-speak, a private citizen, this does raise the question of the grounds on which these ‘proto-Noahs’ were selected from among their peers to fulfil their great task. It is not evident that either was an obvious choice as, say, a famous boat-builder. There is some indication of temple connections, but nothing to indicate that the hero was actually a member of the priesthood. Perhaps the selection was on the grounds that what was needed was a fine, upright individual who would listen to divine orders and carry them out to the full whatever his private misgivings, but we are not told.

As investigation goes forward in this book now we will pursue what happened to the Flood Story as it translated itself beyond the cuneiform world into the Hebrew of the Book of Genesis and the Arabic of the Koran. In addition, there is the testimony of the excellent Berossus to round out the picture.

Just when the old cuneiform world was on the wane and rule over ancient Mesopotamia was in the hands of Aramaic and Greek speakers, a Babylonian priest known to us as Berossus compiled a work about everything Babylonian known to him which he called Babyloniaka (Babylonian things). His name is the Greek version (Βήρωσσος) of a proper Babylonian proper name, very likely to be reconstructed as Bel-re’ushu, ‘The Lord – or Bel – is his shepherd’. Berossus lived in the ancient Iraq of the third century BC, spoke Babylonian (as well as Aramaic and Greek) and could no doubt read cuneiform fluently. Since he was employed in the Marduk Temple at Babylon he had access to all the cuneiform tablets he could possibly want (on top of which they were probably all perfectly complete, too). With their aid he compiled his great work, which he dedicated to the king, Antiochus I Soter (280–261 BC).

Berossus recounts the Flood Story in very recognisable terms in his Book 2, after a list of ten kings and their sages. Unfortunately, his writings (possibly also including those of a pseudo-Berossus) have only survived in quotations by later authors, and the chain of transmission is rather a tortuous one. What we have today are twenty-two quotations or paraphrases of his output, known as the Fragmenta, and eleven statements about the man himself, called Testimonia. These are the work of classical, Jewish and Christian writers, few of whom are household names today. It is interesting that good Mesopotamian details are preserved in Berossus’s account of the flood that do not appear in the Genesis account version, such as the dream motif – or in either earlier tradition – such as the name of the month, or the burying of the inscriptions, an idea which actually does appear in a different cuneiform text altogether.

Berossus writes according to Polyhistor (as preserved by Eusebius):

After the death of Ardates (variant Otiartes: this is Ubar-Tutu!) his son Xisuthros ruled for eighteen sars and in his time a great flood occurred, of which this account is on record:

Kronos appeared to him in the course of a dream and said that on the fifteenth day of the month Daisos mankind would be destroyed by a flood. So he ordered him to dig a hole and to bury the beginnings, middles, and ends of all writings in Sippar, the city of the Sun(-god); and after building a boat, to embark with his kinsfolk and close friends. He was to stow food and drink and put both birds and animals on board and then sail away when he had got everything ready, If asked where he was sailing, he was to reply, ‘To the gods, to pray for blessings on men.’

He did not disobey, but got a boat built, five stades long and two stades wide, and when everything was properly arranged he sent his wife and children and closest friend on board. When the flood had occurred and as soon as it had subsided, Xisuthros let out some of the birds, which, finding no food or place to rest, came back to the vessel. After a few days Xisuthros again let out the birds, and they again returned to the ship, this time with their feet covered in mud. When they were let out for the third time they failed to return to the boat, and Xisuthros inferred that land had appeared. Thereupon he prised open a portion of the seams of the boat, and seeing that it had run aground on some mountain, he disembarked with his wife, his daughter, and his pilot, prostrated himself to the ground, set up an altar and sacrificed to the gods, and then disappeared along with those who had disembarked with him. When Xisuthros and his party did not come back, those who had stayed in the boat disembarked and looked for him, calling him by name. Xisuthros himself did not appear to them any more, but there was a voice out of the air instructing them on the need to worship the gods, seeing that he was going to dwell with the gods because of his piety, and that his wife, daughter and pilot shared in the same honour. He told them to return to Babylon, and, as was destined for them, to rescue the writings from Sippar and disseminate them to mankind. Also he told them that they were in the country of Armenia. They heard this, sacrificed to the gods, and journeyed on foot to Babylon. A part of the boat, which came to rest in the Gordyaean mountains of Armenia, still remains, and some people scrape pitch off the boat and use it as charms. So when they came to Babylon they dug up the writings from Sippar, and, after founding many cities and setting up shrines, they once more established Babylon.

Berossus writes according to Abydenus:

After whom others ruled, and Sisithros, to whom Kronos revealed that there would be a deluge on the fifteenth day of Daisios, and ordered him to conceal in Sippar, the city of the Sun(-god), every available writing. Sisithros accomplished all these things, immediately sailed to Armenia, and thereupon what the god had announced happened. On the third day, after the rain abated, he let loose birds in the attempt to ascertain if they would see land not covered with water. Not knowing where to alight, being confronted with a boundless sea, they returned to Sisithros. And similarly with others. When he succeeded with a third group – they returned with muddy feathers – the gods took him away from mankind. However, the boat in Armenia supplied the local inhabitants with wooden amulets as charms.

Keep the excellent Berossus in mind; we will call upon him later.

The life of Nuh (Noah) before the Flood is described in Sura 71 of the Koran. He was the son of Lamech, one of the patriarchs from the generations of Adam. Nuh was a prophet, called to warn mankind and encourage the people to change their ways. The following quotations collect what we learn about Nuh and his ark from the Koran (the translation uses Noah throughout):

We saved him and those with him on the Ark and let them survive.

Sura 10:73

It was revealed to Noah, ‘None of your people will believe, other than those who have already done so, so do not be distressed by what they do. Build the Ark under Our [watchful] eyes and with Our inspiration. Do not plead with Me for those who have done evil – they will be drowned.’ So he began to build the Ark, and whenever leaders of his people passed by, they laughed at him. He said, ‘You may scorn us now, but we will come to scorn you: you will find out who will receive a humiliating punishment, and on whom a lasting suffering will descend.’ When Our command came, and water gushed up out of the earth, We said, ‘Place on board this Ark a pair of each species, and your own family – except those against whom the sentence has already been passed – and those who have believed,’ though only a few believed with him. He said, ‘Board the Ark. In the name of God it shall sail and anchor. My God is most forgiving and merciful.’ It sailed with them on waves like mountains, and Noah called out to his son, who stayed behind, ‘Come aboard with us, my son, do not stay with the disbelievers.’ But he replied, ‘I will seek refuge on a mountain to save me from the water.’ Noah said, ‘Today there is no refuge from God’s command, except for those on whom He has mercy.’ The waves cut them off from each other and he was among the drowned. Then it was said, ‘Earth, swallow up your water, and sky, hold back,’ and the water subsided, the command was fulfilled. The Ark settled on Mount Judi, and it was said, ‘Gone are those evildoing people!’ Noah called out to his Lord, saying, ‘My Lord, my son was one of my family, though Your promise is true, and You are the most just of all judges.’ God said, ‘Noah, he was not one of your family. What he did was not right. Do not ask Me for things you know nothing about. I am warning you not to be foolish.’ He said, ‘My Lord, I take refuge with You from asking for things I know nothing about. If You do not forgive me, and have mercy on me, I shall be one of the losers.’ And it was said, ‘Noah, descend in peace from Us, with blessings on you and on some of the communities that will spring from those who are with you.’

Sura 11:36–48

Noah said, ‘My Lord, help me! They call me a liar,’ and so We revealed to him: ‘Build the Ark under Our watchful eye and according to Our revelation. When Our command comes and water gushes up out of the earth, take pairs of every species on board, and your family, except for those on whom the sentence has already been passed – do not plead with me for the evildoers: they will be drowned – and when you and your companions are settled on the Ark, say, “Praise be to God, who delivered us from the wicked people,” and say, “My Lord, let me land with Your blessing: it is You who provide the best landings.” ’ There are signs in all this: We have always put [people] to the test.

Sura 23:26–30

He said, ‘My Lord, my people have rejected me, so make a firm judgement between me and them, and save me and my believing followers.’ So We saved him and his followers in the fully laden ship, and drowned the rest.

Sura 26:117–20

We sent Noah out to his people. He lived among them for fifty years short of a thousand but when the Flood overwhelmed them they were still doing evil. We saved him and those with him on the Ark (safina). We made this a sign for all people.

Sura 29:14–15

So We opened the gates of the sky with torrential water, burst the earth with gushing springs: the waters met for a preordained purpose. We carried him along on a vessel of planks and nails that floated under Our watchful eye, a reward for the one who had been rejected.

Sura 54:11–14

But when the Flood rose high, We saved you in the floating ship, making that event a reminder for you: attentive ears may take heed.

Sura 69:10–12

It is an exciting matter to compare the new Ark Tablet – dating to the Old Babylonian Period, probably about 1750 BC – with all these familiar and less familiar accounts. There are sixty new lines of literary Babylonian to occupy us, and poking about among the words certainly uncovers interesting things concerning the Flood Story as it developed within ancient Mesopotamian literature and beyond. The Ark Tablet packs in crucial and dramatic sections of the broader story which we will investigate in the following chapters, at the same time comparing what we have already known from these versions in Sumerian, Babylonian, Hebrew, Greek and Arabic.

Our task now is to see what evidence can be wrung out of each new line of cuneiform writing. Many new ideas come and some old ones will have to be upset, not least the shape of the famous Ark in the Epic of Gilgamesh, as we will see.