In the four decades between 1969 and 2009, a total of 5,586 people were killed in terrorist attacks against the United States or its interests, according to a May 2011 report by a conservative Washington policy institute, the Heritage Foundation. This number includes those killed in the terror attacks within the United States on September 11, 2001.1 By comparison, more than 30,000 people were killed by guns in the United States every single year between 1986 and 2010, with the exception of four years in which the number of deaths fell slightly below 30,000—1999, 2000, 2001, and 2004. In other words, the number of people killed every year in the United States by guns is about five times the grand total of Americans killed in terrorist attacks anywhere in the world since 1969.2

Here is another perspective. In 2010, five Americans were killed worldwide by terrorist attacks.3 In the same year, fifty-five law enforcement officers were killed by guns in the United States—out of a total of fifty-six officers killed feloniously.4 (The fifty-sixth officer was killed by a motor vehicle.) In plain words, more than ten times the number of law enforcement officers were killed by guns in the United States in 2010 than all of the Americans killed by terrorism anywhere in the world that year.

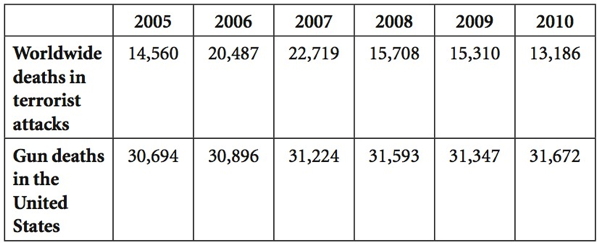

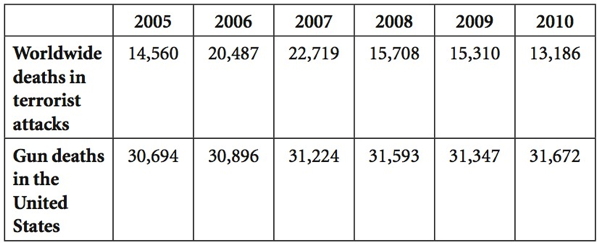

It gets even worse. Every year, more Americans are killed by guns in the United States than people of all nationalities are killed worldwide by terrorist attacks. Figure 1 compares the number of people killed worldwide in terrorist attacks in the six years 2005 through 2010 with the number of people killed by guns in the United States in the same years.

Figure 1. Worldwide Terrorism Deaths and U.S. Gun Deaths, 2005–10

Terrorism deaths, U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Terrorism, 2008 and 2010; gun deaths, 2005–2010, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WISQARS, “2001–2010, United States Firearm Deaths and Rates per 100,000.”

America has engaged in a “War Against Terrorism” at tremendous social and financial cost since the so-called 9/11 attacks of September 11, 2001. As of March 2011, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and a program called Operation Noble Eagle to enhance security at military bases, had cost American taxpayers $1.283 trillion.5 In addition to the money spent on these wars, increased federal, state, and local costs for “homeland security” totaled more than $1 trillion over the decade between September 2001 and September 2011.6 The scholars who compiled this number concluded in their 2011 book on the subject that “most enhanced homeland security expenditures since 9/11 fail a cost-benefit assessment, it seems, some spectacularly so, and it certainly appears that many billions of dollars have been misspent.”7 According to Ohio State University professor John Mueller, one of the authors of the homeland security cost study, an American’s chances of being killed in an automobile accident are about one in 7,000 or 8,000 per year; of being a victim of homicide, about one in 22,000 per year; and of being killed by a terrorist, about one in 3.5 million per year.8

There is little sign that this “counterterrorism state unto itself”—as the conservative Washington Times called it—is likely to wither away soon.9 The Department of Homeland Security’s budget request was $56.3 billion for fiscal year 2011, $57 billion for FY 2012, and $39.5 billion for FY2013.10 In contrast, the combined budget request for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry was $11.3 billion for FY2012 and $11.2 billion for FY2013.11

The specter of terrorism that drives these costs also has inspired infringements on civil liberties that at least some would have thought unthinkable before the attacks.12 “The courts have been failing terribly,” law professor Susan N. Herman, the president of the American Civil Liberties Union, told the New York Times in 2011. “The Fourth Amendment has been seriously diluted.”13 One of the features of the war on terror most salient to this book’s subject has been what former attorney general John Ashcroft called “a new paradigm,” which among other things added the “new priority . . . of prevention” of terrorism to the Justice Department’s traditional focus on criminal prosecution.14

The questions compel themselves.

Why is there no equivalent “war” against gun violence, which takes and shatters the lives of more Americans than does terrorism by many, many times every single year?

Why, when other articles of the Bill of Rights—such as those involving searches, wiretaps, and preventive arrests—are “balanced” against the fear of terrorism, is the Second Amendment fiercely claimed to be “untouchable” by the gun lobby and by the politicians who hew to its line, and is slavishly protected by activist conservative judges? Why do even many who favor some form of gun control continue to focus on “illegal guns” and the prosecution of criminals instead of adding “a new paradigm” of prevention?

Given the lack of widespread public outcry for a reordering of our national priorities, Americans and their political leaders appear either to be ignorant of, or to have become inured to, the endless torrent of civilian gun violence in the United States. Why?

And finally, why has the subject of gun control become, even among influential “moderate” Democrats, the “third rail” of politics?

This book examines and answers those questions. It documents in detail each of the following factors that contribute to the unique position of the United States as the world’s dark archetype of gun violence:

• Levels of gun death and injury that mark the United States as a frightening aberration among industrialized nations.

• Deliberate suppression of data regarding criminal use of firearms, gun trafficking, and the public health consequences of firearms in the United States.

• The almost universal failure of the American news media to report on, even to understand, the continuing hurricane of gun violence in America.

• Aggressive “hypermarketing” of increasingly lethal weapons by a faltering industry.

• Militarization of the civilian gun market as the driving force in that marketing.

• Indifference by policy makers who might be expected to lead on gun control, and widespread acquiescence by elected officials to the gun lobby’s unrelenting legislative campaigns.

The intricate interweaving of these factors is aptly illustrated by an incident that occurred on Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado on November 21, 2011. On that date, at about ten o’clock in the morning, Airman First Class Nico Cruz Santos barricaded himself in a building, armed with his personal handgun.15 The base, located near Colorado Springs, is home to the Fiftieth Space Wing, responsible for operating U.S. Department of Defense space satellites.16

Santos was serving in a squadron that “provides physical security, force protections measures and law enforcement services” to the wing.17 He appears to have been a troubled person, reacting to his imminent discharge from the air force and possible imprisonment after having pleaded guilty in a civilian court to a charge of attempted sexual exploitation of a child.18 Airman Santos surrendered without violence at about eight P.M.

The building in which Santos barricaded himself was a personnel processing center, a facility in which airmen are prepared for deployment. That fact brought immediately to mind the events of November 5, 2009, when U.S. Army Major Nidal M. Hasan is alleged to have gone on a rampage with his personal handgun in a similar deployment center at Fort Hood, Texas. Hasan left a total of thirteen dead and thirty-two wounded.19 Major Hasan was subdued only after he was shot several times by police.

In the interval between the two events, and as a direct consequence of the Pentagon’s reaction to Major Hasan’s attack at Fort Hood, Congress imposed a significant restriction on the Department of Defense. Sandwiched between two sections of the defense authorization bill for fiscal year (FY) 2011, mandating public access to Pentagon reports and establishing criteria for determining the safety of nuclear weapons, was a new provision, Section 1062, “Prohibition on infringing on the individual right to lawfully acquire, possess, own, carry, and otherwise use privately owned firearms, ammunition, and other weapons.”20 As a result of that change in law, General Peter Chiarelli, the army’s second-in-command, told the Christian Science Monitor in November 2011, “I am not allowed to ask a soldier who lives off post whether that soldier has a privately owned weapon.”21 The prohibition covers both members of the military and civilian employees of the Defense Department.

The massacre of which Major Nidal Hasan is accused generated a great deal of attention from the news media, policy makers, and politicians. However, most of this attention focused on two points: whether the mass shooting should be classified as a terrorist attack by “violent Islamist extremism,”22 and where blame should be assigned within the nation’s military and intelligence apparatuses for failure to anticipate and head off the rampage.23

Little media reporting and virtually no official scrutiny has been devoted to the singular implement with which Major Hasan is accused of mowing down forty-five of his comrades-in-arms within ten minutes. This was an FN Five-seveN, a 5.7mm high-capacity semiautomatic pistol manufactured by the Belgian armaments maker FN Herstal (FN).24

In one significant example, the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs issued a report purporting to address the “counterterrorism lessons” to be drawn from the Fort Hood matter. But the committee’s report emphasized that it had not “examined . . . the facts of what happened during the attack.”25 The word gun or firearm appears nowhere in the committee’s report, much less the make, model, and caliber of the efficient killing machine Major Hasan is accused of using. The committee described the incident itself in two sentences, as a “lone attacker” striding into the center, and “moments later,” thirteen “employees” of the Defense Department “were dead and another 32 were wounded,” all by some unnamed cause.26 This is the remarkable equivalent of issuing a “lessons learned” report on the notorious 1995 bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City without mentioning the truck bomb by which its principal perpetrator, Timothy McVeigh, carried out his attack, or presenting a lecture on the implications of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, without addressing the use of commandeered jetliners as flying bombs. The omission is all the more remarkable because the committee chairman and co-author of the report, Senator Joseph I. Lieberman, had stated in a May 2010 hearing on terrorists and guns that “the only two terrorist attacks on America since 9/11 that have been carried out and taken American lives were with firearms.”27 he cited the Fort Hood shooting and the 2009 murder of an army recruiter in Little Rock, Arkansas, as the two attacks.

But according to testimony at a pretrial hearing, Major Hasan himself paid keen attention to selecting the weapon he used. He chose the FN Five-seveN pistol, and the accessories of laser aiming devices and high-capacity ammunition magazines, precisely because they suited his purpose of efficiently attacking a large number of people.28 Thus, before buying the handgun on August 1, 2009, Hasan asked a salesman at the Guns Galore gun dealer in Killeen, Texas, for “the most high-tech gun” available. Another witness, Specialist William Gilbert, a soldier and self-described “gun aficionado” who was in the store when Major Hasan made his inquiry, testified that the accused also sought maximum ammunition magazine capacity. Specialist Gilbert further testified that he owned an FN Five-seveN himself, and that he had recommended that model to Major Hasan because it met the officer’s stated specifications. “It’s extremely lightweight and very, very, very accurate,” said Specialist Gilbert. “It’s easy to fire and has minimum recoil.”29 The soldier testified that he gave Major Hasan a forty-five-minute “full tactical demonstration” of the handgun’s capabilities.30 According to the manufacturer, those capabilities are considerable. “Five-seveN Tactical handguns and SS190 ball ammunition team up to defeat the enemy in all close combat situations in urban areas, jungle conditions, night missions, etc. and for any self-defense action.”31

Specialist Gilbert and the salesman both noted that Major Hasan seemed to know nothing about handguns. The accused officer videotaped on his cell phone the salesman’s demonstration of how to load and clean the weapon so that he could review these procedures later.

In the several months between his purchase of the handgun and the shootings at Fort Hood, Major Hasan also bought several extra ammunition magazines and magazine extenders that increased to thirty the number of rounds available to be fired in each loading of the gun, from the usual twenty.32 He bought two expensive laser aiming devices, a green one for use in daylight and a red one for use at night. The major also bought hundreds of rounds of the 5.7x28mm ammunition the gun fires, including boxes of a variant specifically designed to penetrate body armor. According to testimony at the hearing, the line of ammunition in question had been ordered off the U.S. civilian market, but dealers were allowed to sell their existing stocks.33

Major Hasan was a frequent visitor to Stan’s Outdoor Shooting Range, near Fort Hood, where he took a course to qualify for a concealed-carry permit. Witnesses said Major Hasan practiced at the range repeatedly. He specifically sought training in shooting at human targets from as far away as a hundred yards. Instructor John Coats testified that after one afternoon’s tutelage, Major Hasan progressed from being an erratic shot to routinely hitting each target’s head and chest. This is consistent with FN’s boast that “the flat trajectory of the 5.7x28mm ammunition guarantees a high hit probability up to 200 m. Extremely low recoil results in quick and accurate firing.”34

On the morning of November 5,2009, Major Hasan allegedly put his high-tech weapon and training to use when he opened fire with his FN Five-seveN in a crowded waiting area near the entrance to Building 42003, a facility for processing soldiers being deployed. Ten minutes later, he lay paralyzed from the chest down, shot by police. When the bloodbath ended, twelve soldiers and one civilian had been shot dead. An additional thirty-one soldiers and one police officer were wounded. A number of other people were injured in the scramble to escape the methodical shooting. Army investigators found more than 200 spent 5.7mm rounds in and around Building 42003. So many rounds were fired that shell casings lodged in the tread of the shooter’s boots, survivors testified, so that they could hear a clicking noise at every step he took. “You could hear the clack, clack, clack at the same time you could hear the bang, bang, bang of the guns,” one testified.35 Major Hasan had another 177 unfired rounds in high-capacity magazines when he was stopped.

Witnesses testified that the defendant reloaded often and effortlessly as he calmly walked though the building. One survivor, Specialist Logan Burnett, tried to rush the shooter when he saw an expended magazine fall from the pistol, but was shot in the head before he could reach the gunman. Another soldier contemplated also charging, but testified that the shooter reloaded magazines too quickly for him to act.36

Virtually none of the detailed testimony at Major Hasan’s pretrial hearing has been reported in the news media. With the exception of newspapers in Texas and a handful of articles in other states, the details of Major Hassan’s alleged massacre were not “newsworthy.” And although mass shootings, cop-killings, and family annihilations have become virtually weekly events in the United States, their coverage by the news media is spotty. For all of the attention the Fort Hood affair generated in the media and particularly in the Congress, its toll of dead and injured was no greater than a number of civilian mass shootings involving handguns. These include the April 2009 shooting at the American Civic Association in Binghamton, New York (thirteen dead, four wounded), the April 2007 shooting at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia (thirty-two dead, seventeen wounded), and the October 1991 shooting at Luby’s Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas (twenty-three dead, twenty wounded). Many other civilian mass shootings have taken somewhat lesser tolls, such as the January 2011 shooting in Tucson, Arizona, in which U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords was gravely injured (six dead, thirteen wounded).37

Like the news media, the Department of Defense also appears to have missed the significance of the incredible level of firepower that was easily available to Major Hasan. After the Fort Hood shooting, Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates appointed Togo D. West Jr., a former secretary of the army, and Admiral Vernon E. Clark, a former chief of naval operations, to conduct a review of the incident. The review focused primarily on how well the Defense Department was prepared to meet similar incidents in the future and how the department’s policies might better deal with personnel like the alleged shooter. Aside from a single reference to an unnamed “gunman” having “opened fire,” the report of the review neither described nor inquired into the means—the FN Five-seveN pistol, the high-capacity ammunition magazines, and the laser aiming devices—by which Major Hasan allegedly wreaked such great havoc in so short a time.38 An appendix to the report, however, stated the finding that “the Department of Defense does not have a policy governing privately owned weapons,” and recommended that the department “review the need for DoD privately owned weapons policy.”39

Three months later, the Department of Defense announced its follow-up action on twenty-six of the seventy-nine recommendations of the independent review.40 A detailed list accompanying Secretary Gates’s action memorandum noted with respect to privately owned weapons that each of the individual armed services had developed its own policies and had delegated authority to base commanders to generate specific rules.41 According to media reports, the commanders of some bases—including Fort Campbell, Kentucky; Fort Bliss, Texas; and Fort Riley, Kansas—required personnel living off post to register their personal firearms. In the case of Fort Riley, civilian dependents were also required to register their firearms.42 The list attached to Secretary Gates’s memorandum stated that the undersecretary of defense for intelligence was tasked to prepare department-wide guidance on personal guns, which would then be incorporated into the department’s physical security regulations.43

These actions were sufficient to galvanize the National Rifle Association (NRA), the principal voice of the gun industry lobby.44 One month after Secretary Gates’s announcement, U.S. Senator Jim Inhofe introduced the “Service Member Second Amendment Protection Act of 2010,” which was designed to forbid any action by the Defense Department that might affect personal weapons.45 “Adding more gun ownership regulations on top of existing state and federal law does not address the problems associated with Hasan’s case,” Senator Inhofe stated in a press release. Referring to the proposed Defense Department regulations, he continued, “Political correctness and violating Constitutional rights dishonors those who lost their lives and is an extreme disservice to those who continue to serve their country.”46

Senator Inhofe offered his bill as an amendment to the Defense Department’s authorization bill for FY 2011. It was adopted by the Senate, and although no similar provision had been passed in the House version of the authorization bill, it was included in the legislation as enacted, and thus passed into law.47 Chris W. Cox, executive director of the NRA’s lobbying arm, the Institute for Legislative Action (ILA), took credit for the legislation, announcing in a “Political Report” on the matter that “your NRA has sought, and achieved, remedies to some of the worst abuses our service members have suffered, through legislation recently passed by the Congress and signed into law.”48

The FN Five-seveN and the accessories chosen by Major Hasan are neither aberrant nor unusual products on the U.S. civilian gun market. They are, rather, typical examples of the military-style weapons that define that market today. There is no mystery in this militarization. It is simply a business strategy aimed at survival: boosting sales and improving the bottom line in a desperate and fading line of commerce.49 The hard commercial fact is that military-style weapons sell in an increasingly narrowly focused civilian gun market. True sporting guns do not.

Like the tobacco industry, the gun lobby has gone to extreme lengths to draw a veil of secrecy over the facts surrounding its terrifying impact on American life. The tobacco industry successfully fought regulation for decades after its products were known to be pestilential. But a crack in the industry’s wall of deceit and influence was opened through the process of discovery in private tort lawsuits. Putting aside compensation for the ravaging illnesses tobacco caused its victims, “litigation forced the industry to reveal its most intimate corporate strategies in the tobacco wars.”50 Discovery revealed that the tobacco industry “had not been dealing straightforwardly with the public but had been acting in deceptive ways to ease its customers’ growing anxieties over the health charges.”51 This revealing light on the industry’s darkest schemes helped accelerate tighter regulation—“perhaps the most significant change was the public recognition of the industry’s extensive knowledge of the harms of its product, and its concerted efforts to obscure these facts through scientific disinformation and aggressive marketing.”52

Knowing that the gun industry could only lose in any public forum in which information about the consequences of its products was freely available, the gun lobby’s strategists marked well the tobacco industry’s defeats in court. After tort litigation was brought against the industry by innocent victims of its lethal products and reckless marketing, the NRA succeeded in pushing though Congress the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, which President George W. Bush signed into law in 2005.53 This extraordinary federal law shields the gun industry against all but the most carefully and artfully crafted private lawsuits.

Another prong of the NRA’s assault on freedom of information about the gun industry has been a series of so-called riders—prohibitory amendments attached to appropriations bills—that began in 2003 and have collectively come to be known as the Tiahrt amendments, after their perennial sponsor, former representative Todd Tiahrt of Kansas. These amendments have forbidden the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) from releasing to the public useful information about gun trafficking and gun crimes. Although some information may be released to law enforcement agencies and ATF occasionally publishes its own limited summary reports, the agency’s top officials have chosen to broadly interpret these prohibitions, virtually shutting down their responses to information requests from the general public and researchers.54

Section 1062 of Public Law 111–383 forbids the Department of Defense to “collect or record” any information about the private firearms of members of the military or its civilian employees, unless they relate to such arms on a defense facility proper, and further directs the department to destroy within ninety days of the date of its enactment any such records it may have previously assembled.

It was noted above that the word gun appears nowhere in the report of the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs regarding the shootings at Fort Hood. Like much of what goes on in Congress, the report’s drafting was done behind closed doors, but some clue as to why the authors of the report chose not to mention Major Hasan’s wondrously deadly weapon may be found in the words of one co-author, the committee’s ranking Republican member, Senator Susan Collins, in her opening statement at the committee’s hearing Terrorists and Guns: The Nature of the Threat and Proposed Reforms.

For many Americans, including many Maine families, the right to own guns is part of their heritage and way of life. This right is protected by the Second Amendment.

And so this Committee confronts a difficult issue today: how do we protect the constitutional right of Americans to bear arms, while preventing terrorists from using guns to carry out their murderous plans?55

One way to “protect the constitutional right” is simply to ignore the consequences of that right. This has increasingly been the choice of the nation’s political leadership. In the words of Jim Kessler, vice president for policy at Third Way, a group distinguished both by its poll-driven policy proposals and its influence among moderate Democrats, “guns seem like the third rail.”56

Although Congress and the White House are perfectly prepared to “balance” other constitutional rights in pursuit of the so-called war on terror, neither has even the slightest inclination to do so in the case of gun rights, notwithstanding the massively disproportionate harm guns inflict on Americans. In 2009, for example, when U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder had the temerity to suggest that Congress should reenact the expired federal assault weapons ban, then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi swiftly squelched the idea. “Echoing the position often taken by advocates of gun rights,” according to the New York Times, Pelosi observed, “On that score, I think we need to enforce the laws we have right now.”57 The issue is considered “toxic” to Democrats, according to many political observers.58

Staying clear of the third rail of gun control thus has become a political byword in Washington. If there was any debate at all on Senator Inhofe’s amendment to the defense authorization bill, none of it appears in the public record. The proceedings both of the Senate Armed Services Committee and of the committee that reconciled the different versions of the House and Senate were closed to the public. No public statement in opposition was issued by any member of Congress nor by the Obama administration.

Thus, as the Fort Hood affair demonstrates, the gun lobby has successfully shut down information, intimidated any political opposition, and endangered all Americans by its reckless militarization of our public space. The consequences for public health and the safety of ordinary Americans are grim. We all are placed in danger by the gun lobby’s actions and by the deafening silence in response from America’s political leaders.

This book sets out to expose this shameful and entirely preventable record of inaction in the face of needless death and injury and to sound a sensible, fact-based call to action to end the needless bloodshed.

Chapters 1–3 mount a thorough inquiry into the numbing level of gun violence and its effects in America.

Chapters 4–6 explain the fundamental cause of that violence: a mercenary industry and a cynical gun lobby, working hand in hand to sell the last gun to the last buyer.

Chapters 7–9 counter the conventional wisdom that the pro-gun forces in America are too powerful to be broken. They ask, “What would happen if Americans decided to take on the industry and its powerful allies?” The chapters’ answer is that the gun lobby can be defeated, and that well-framed, fact-driven solutions work to save lives.