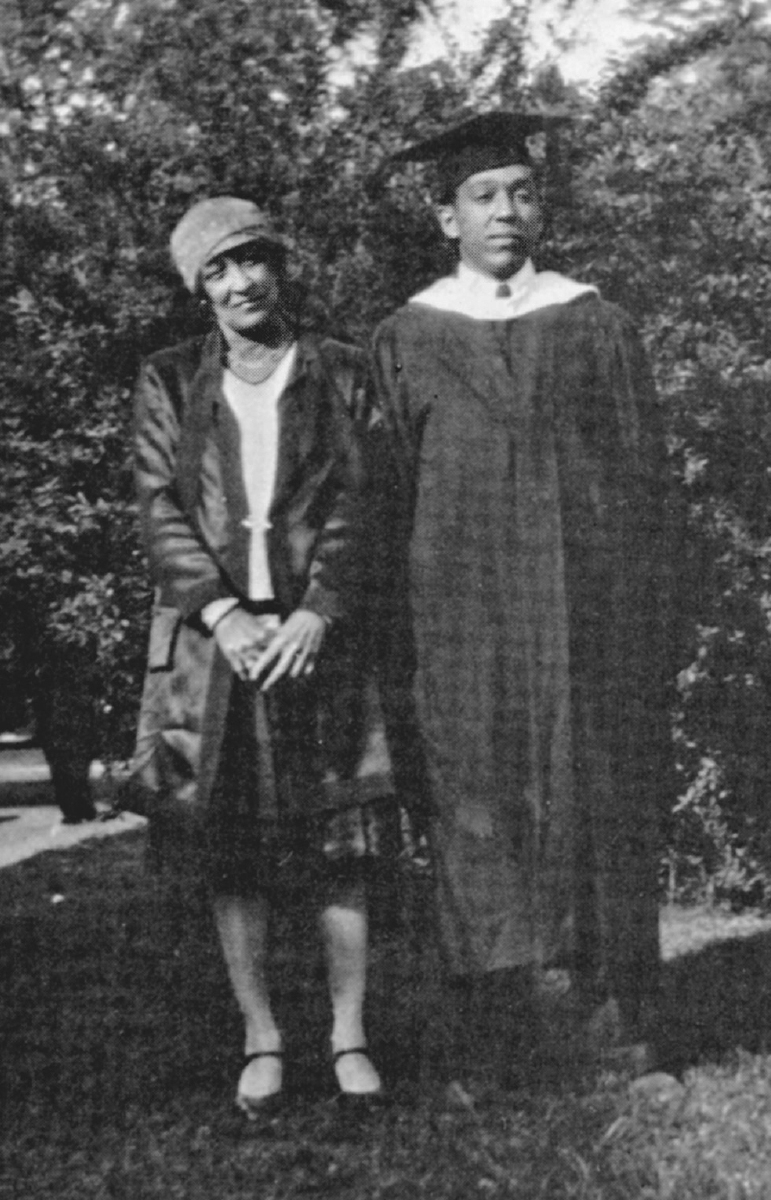

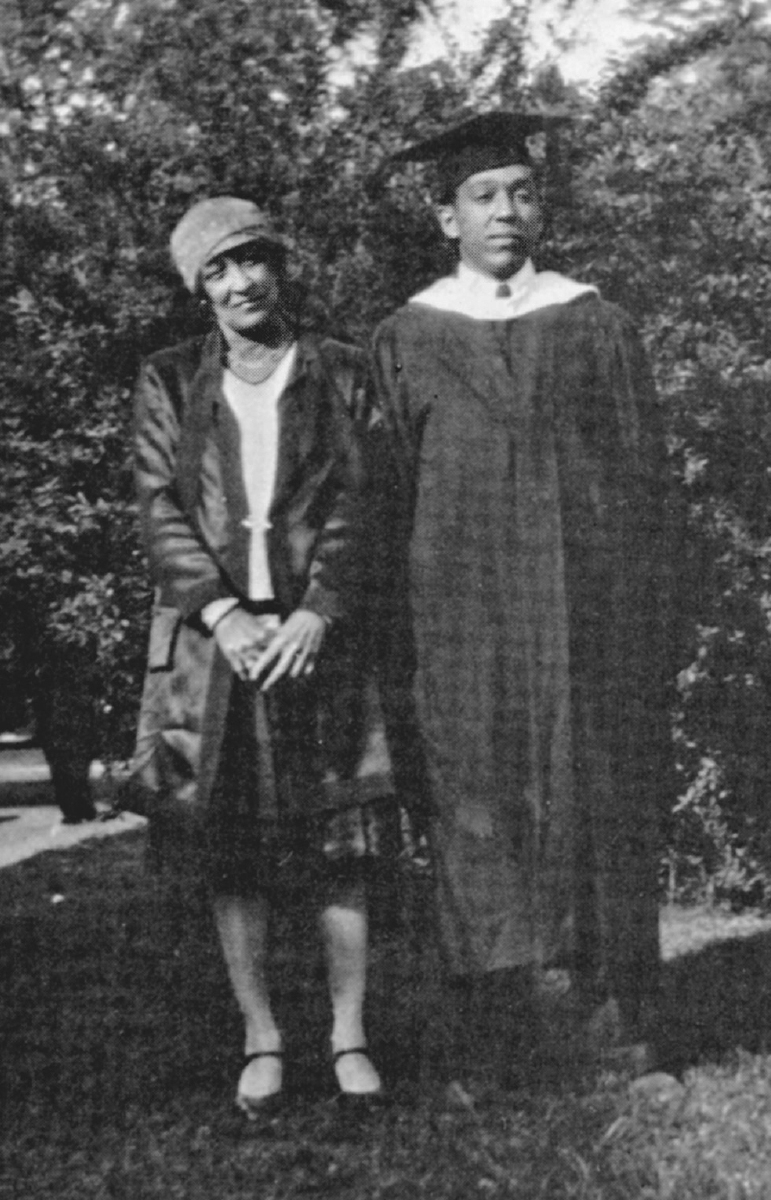

With his mother Carrie Clark at graduation, Lincoln University, 1929 (illustration credit 7)

I got the Weary Blues

And I can’t be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can’t be satisfied—

I ain’t happy no mo’

And I wish that I had died.

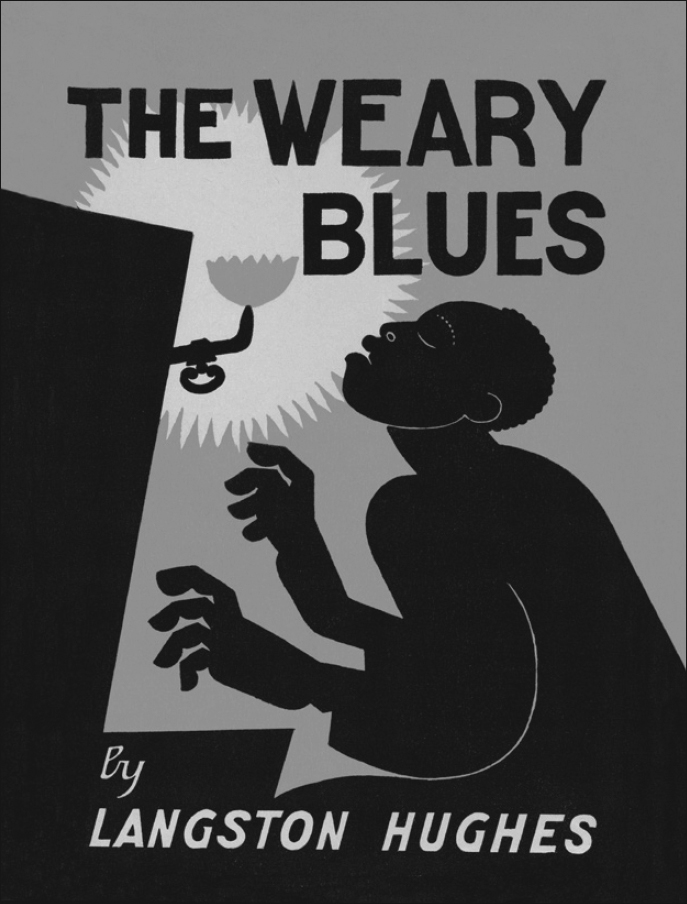

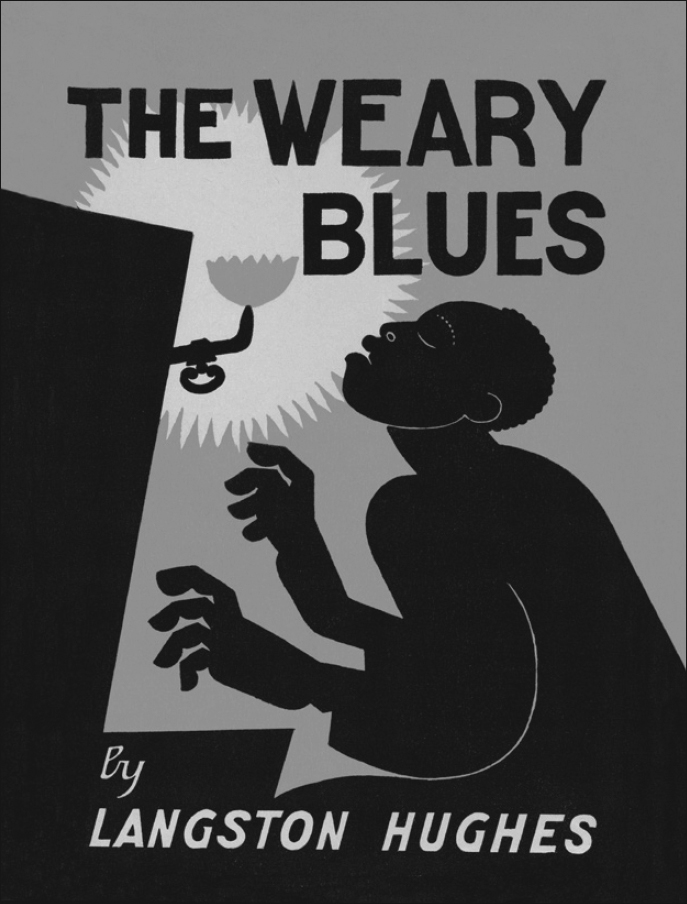

Returning to the United States in November 1924, Hughes lived with his mother and stepbrother in Washington, D.C., for just over a year. While he worked at various low-paying jobs, he continued to explore the blues, jazz, and other African American forms in his verse. In 1925, “The Weary Blues” won the top prize for poetry in a contest run by the magazine Opportunity. From that moment Hughes was seen as one of the stars of the Harlem Renaissance. His first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, appeared in 1926, the same year that he enrolled in Lincoln University, a historically black school in Pennsylvania. While critics liked his first book, some were scathing about his second, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927), because of its sympathetic emphasis on “low-class” black culture. But Hughes was defiant on this matter. In the June 23, 1926, issue of The Nation, he had proclaimed his rebellious credo in his most famous essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” He declared: “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter.… If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”

1917—3rd Street N.W.,

Washington, D.C.,1

December 14, 1924.

Dear Harold:

What’s the New York news?

I’ve got another job since you left. I’m working on the “Washington Sentinel” now, one of the colored weeklies here, breaking in on a newspaper.2 The work’s all right, just so it yields the bucks.

Did you get home safe and sound? Teaching yet? Why don’t you go South and get a school? It would be warm down there (in more ways than one!). But seriously, you’re the type of young man they need down there, and you’d be doing more racial good spreading culture where culture isn’t, than you would teaching in New York City or Washington. Don’t you think so? And there they need you.

Oh—How I love to give advice! Take it!

Write to me soon.

Sincerely yours,

Langston Hughes

TO HAROLD JACKMAN [ALS]

Dear Harold:

Very glad to get your letter. Thanks, too, for the one you sent on. It contained lots of news from Europe.

No news at all over here. Except that I have a new job—about the twenty-third since you left. I’m with the Associated Publishers now, Dr. Woodson’s Journal of Negro History, you know.3 It’s a “position,” if you please! with very decent hours. I think I’m anchored here forever.

I hope you’ll be teaching during the new term.

Sincerely,

Langston

1749-S-Street, N.W.,

Washington, D.C.,

January thirteenth |1925|.

1749 S Street, N. W.

Washington, D.C.

May 15, 1925.

Dear Friend,4

I would be very, very much pleased if you would do an introduction to my poems. How good of you to offer. I am glad you liked the poems in the new arrangement and I do hope Knopf will like them, too. It would be great to have such a fine publisher!

About your paper on the Blues,5—Sunday I am going to type some old verses for you that I used to hear when I was a kid, and that you may or may not have heard. You probably have. On the new records I think the Freight Train Blues (one of the many railroad Blues) is rather good, and Reckless Blues, and Follow the Deal on Down. Did you ever hear this verse of the Blues?

I went to the gypsy’s

To get my fortune told.

Went to the gypsy’s

To get my fortune told.

Gypsy done told me

Goddam your un-hard-lucky soul!

I first heard it from George, a Kentucky colored boy who shipped out to Africa with me,—a real vagabond if there ever was one.6 He came on board five minutes before sailing with no clothes, nothing except the shirt and pants he had on and a pair of silk sox carefully wrapped up in his shirt pocket. He didn’t even know where the ship was going. And when somebody on board gave him a suit he traded it in the first port to sleep with a woman. He used to make up his own Blues,—verses as absurd as Krazy Kat7 and as funny. But sometimes when he had to do more work than he thought necessary for a happy living, or, when broke, he couldn’t make the damsels of the West Coast believe love |was| worth more than money, he used to sing about the gypsy who couldn’t find words strong enough to tell about the troubles in his hard-luck soul.

I did like the Blind Bow-boy. I hope you will send Peter Whiffle.8 Do you know any Negro Pauls in Harlem—those decorative boys who never do any work and who have some surprisingly well-known names on their lists? In a really perfect world <,though,> people who are beautiful or amusing would be kept alive <anyway> solely because they are beautiful and amusing, don’t you think?

About the story of my life,—I don’t know what you want it for, and for me to sit down seriously and think about it and write it would take a long, long time. I mean,—to show cause and effect, soul-peregrinations, and all that sort of thing. <How serious it sounds!> But I will send you an outline sketch of external movements; an essay I did for the Crisis Contest on the Fascination Of Cities;9 and a semi-autobiographical poem I did for the Crisis, but which I don’t think they’re publishing. Out of all that junk you’ll perhaps get something. And then if you would know more, just ask me, and I’ll be glad to answer.

I’m having some pictures taken here, but they may not be as good as the Muray10 ones, so perhaps you’d better get him to give you one of his if you wish one.

I am anxiously awaiting the June Vanity Fair. I like the magazine, and Countee |Cullen| does such lovely things. What’s become of John Peale Bishop?11 I liked his work and I don’t believe I’ve read anything of his lately. And Nancy Boyd’s clever essays?12

Remember me to Harlem.

Sincerely,

Langston

TO CARL VAN VECHTEN [TLS]

Thursday |June 4, 1925|

Dear Carl,

I have been thinking about what you said concerning the histoire de ma vie and the making of a book out of it. I would rather like to do it and yet there are a number of reasons why I wouldn’t like to do it. The big reason is this: There are so many people who would have to be left out of the book, and yet they are people who have been the cause of my doing or not doing half the important things in my life, but they are or have been my friends, for that reason I couldn’t write them up as I would like to. Besides most of them are still very definitely connected with my life in a negative or positive way. So you see, unless I showed effects without causes, or else fictionalized a good deal (which might be interesting) the book wouldn’t be all that it ought to be. Do you get me? And then I’m tired. I’ve had a very trying winter and don’t feel like doing anything all summer except amusing myself. And writing prose isn’t amusing after a day of reading censuses in an office. I can’t be bored both night and day and I don’t want to be driven back to sea from sheer boredom. I ought to give college another trial. Besides, I think I will like Howard.

I’ve just discovered a number of little bars here frequented by southern Negroes where they come to play the banjo and do clog dances. There may be a chance to pick up some new songs and one certainly sees some interesting types.

When you mentioned Bessie Smith you reminded me that I once wrote a Blues for her but never did anything with it. It’s nothing unusual but I’m sending it to you. If you see her ask her if she likes it. She used to be quite amusing when she was doing her old act in small-time houses. And when she sang He May Be Your Man at the big anniversary performance of Shuffle Along in New York (were you there?) she was a “riot,” but the last time I saw her she didn’t seem so good. But I like her records,—and speaking of Blues, have you heard Clara Smith13 sing If You Only Knowed? It’s a real, real sad one! Do hear it. But I believe our tastes in Blues differ. You like best the lighter ones like Michigan Waters and I prefer the moanin’ ones like Gulf Coast and Nobody Knows the Way I Feel This Morning. Have you seen one Ozzie McPhearson?14 She does a low-down single that is really good, but I expect she’ll cut half the rough stuff when she plays New York and then she won’t be so funny. When will your paper on the Blues appear? And is Campaspe in Firecrackers?15 I hope so.

I believe Vanity Fair is using some of my stuff. They sent me a telegram for some more. Otherwise I haven’t heard from them. I’m glad if they liked some of it.

Zora Neale Hurston is a clever girl, isn’t she?16 I would like to know her. Is she still in New York?

What a magnet New York is! Better to be a dish washer there than a very important person in one’s own home town seemingly. A young student friend of mine <from Mexico> has finally arrived there,—to work in a hotel. And yesterday a letter came from Africa, from a boy in Burutu, saying that he intends to stowaway for New York the first chance that offers! And half the Italian boys I knew in Desenzano swear that in a few years they will all be waiters at the Ritz!

Thanks for telling me what the songs are in They Knew What They Wanted.17 And for the suggestions toward writing the book.

I sent you one of the new pictures. Out of four poses I am not sure it is the best, but perhaps you will like it. It looks somewhat like me anyhow. But to relieve the seriousness I am enclosing some snapshots taken with the office girls here.

I would like to come up to New York again but can’t make it for at least two months yet. My expenditures are always ahead of my income and my monthly check is gone before it comes. But I am going to exercise economy, as I have been so often advised, if I can find anything to exercise it on. Being broke is a bore. That’s one reason why I like the sea,—the old man always advances money in port and at sea one doesn’t need any, but on land one needs money all the time and I don’t believe I’ve ever had enough money at any one time to last me more than a day. If it’s a quarter it goes, if it’s fifty dollars it goes just the same, and the next day.… one looks for some more. Today is only the fourth yet my pockets show no signs of having received anything on the first. And June is a long month. All months are.

Write to me soon.

I send pansies and marguerites to you, too,18

Sincerely,

Langston

TO CARL VAN VECHTEN [TLS]

Friday |October 9, 1925|

Dear Carl,

I have been trying to write you for the last two weeks. I have a new job now working in a hotel.19 The hours are longer but I have the whole afternoon off. Almost every day some one comes in, tho, so I get nothing done. I wished I lived in an apartment like you with a hall boy so I could telephone down: Nobody home.… When one gets real famous one must have to be bored with a lot of uninteresting people,—no?

A few days ago I sent you some new Blues. I want to dedicate the best one to you, if any of them are ever published,—and if you like it. I think the Po’ Boy Blues is the best and if you know anyone who would like to do music for one or two of them, please hand them over to them. I’ve got any number of verses, but haven’t been able to put anything together that I think The Mercury20 would like. I wish I could. I don’t think they’d want just a plain song like I sent you, do you?

Jessie Fauset was down here for a week-end a short time ago. She is enthusiastic about your book on cats.21 Says it’s the best thing of yours she has read. Everybody here likes your article on the Negro theatre in Vanity Fair, too. Locke wishes he could have had it for his book. I like your suggestions for improving the revues, especially the one about the choruses: why they don’t use black choruses for a colored show, I don’t know. They can usually sing better and certainly work harder than the yellow girls. A cabaret scene would be a scream, too, if they’d do it right. Irvin Miller22 did have one in one of his shows once. Did you see it, where a black man kept following a high yellow girl around the cabaret floor until his shoes wore out?

The autobiography is coming. I believe it is going to be interesting. I want to have it ready by the first of the year. What’s the news about my other book, do you know? And your Negro novel?….. Are you still thinking of going abroad?… How did Hotsy-Totsy go in Paris?23

Would Knopf object to my reading the Weary Blues over the radio? There’s a bare chance of my getting an engagement at a rate that would be more than a month’s salary at the hotel. The man has asked to see my poetry and is thinking of arranging a Blues accompaniment for The Weary Blues, so I have been told.

Your article with my poetry in Vanity Fair has brought me a number of letters from the various places where I used to live. And there was quite a piece in the Lincoln, Ill. paper about me, followed later by a letter from one of my former teachers telling about how well she remembered me and what a bright boy I was in her classes. You’d think I was famous already! Lots of people seemed to like the Fantasy in Purple.24

Did I tell you in my last letter that Hall Johnson had done the music for a new show that they hope to put on Broadway? I believe it is ready for rehearsals now.

Today is pay-day, so I must go back to work early before the money runs out. Last time I left half my pay in my locker and somebody stole it. This time I shall not be so stupid. I shall buy some new Blues records and pay my rent.… The place I work is quite classy. There are European waiters and it caters largely to ambassadors and base-ball players and ladies who wear many diamonds. It is amusing the way they handle food. A piece of cheese that everybody carries around in <his> hands in the kitchen needs two silver platters and six forks when it is served in the dining room.

Write to me soon.

This time purple asters and autumn leaves,

Sincerely,

Langston

<1749 S Street,

North west.>

TO THE DEAN OF LINCOLN UNIVERSITY [ALS]

1749 S Street, N.W.,

Washington, D.C.,

October 20, 1925.

Dean of the College,

Lincoln University, Pa.

Dear sir,

I wish to become a student at Lincoln University.25 I am a graduate of Central High School, Cleveland, Ohio, and I have been for one year at Columbia College in New York City. I was forced to leave Columbia for lack of funds, but since then I have worked my way to Africa, have spent seven months in Paris and three months in Italy, and on the vessel in which I earned my passage home I visited many of the Mediterranean ports. I have also spent some time in Mexico where, after my high school graduation, I taught English. I have a fair knowledge of both French and Spanish.

My high school record admitted me to Columbia without my taking the entrance examinations. Some of my offices and honors in high school are as follows: Member of the Student Council, President of the American Civic Association, Secretary of the French Club, First Lieutenant Cadet Corps, a letter for work on the track team, and in my senior year, Class Poet and Editor of the Year Book.

For some time I have been writing poetry. Many of my verses have appeared in “The Crisis” and “Opportunity.”26 “The Survey Graphic,” “The Forum,” “The World Tomorrow,” “Vanity Fair,” “The Messenger,”27 and “The Workers’ Monthly,”28 as well as a number of news papers have also published my poems. Some of them have been copied by papers in Berlin, London, and Paris. A poem of mine, “The Weary Blues,” received first prize in the recent Opportunity Contest and, in the Amy Spingarn Contest conducted by The Crisis, my essay received second prize. Early in the new year Alfred A. Knopf will publish my first book of poems.

I want to come to Lincoln because I believe it to be a school of high ideals and a place where one can study and live simply. I hope I shall be admitted. Since I shall have to depend largely on my own efforts to put myself through college, if it be possible for me to procure any work at the school, I would be deeply grateful to you. And because I have lost so much time, I would like to enter in February if students are admitted then. I have had no Latin but I would be willing to remove the condition as soon as possible. I must go to college in order to be of more use to my race and America. I hope to teach in the South, and to widen my literary activities to the field of the short story and the novel.

I hope I shall hear from you soon.29

Yours very sincerely,

Langston Hughes

[Surviving draft of a letter]

|c. December 1925|

Dear Vachel Lindsay,30

I have <been> a long time writing to thank you for your gift.31 I had been away from the hotel with a severe cold and when I came back it was there for me. I don’t know just how to thank you. But perhaps if I say,—and if you will believe me sincere,—that the gift, which you gave me in the way quiet way you did, is one of the most delightful things my poetry ever brought me.

![]() (You will understand how much I value it.) And certainly I am deeply pleased, and honorred by the beauty of your giving.

(You will understand how much I value it.) And certainly I am deeply pleased, and honorred by the beauty of your giving.

Something of what you tell me in your letter on the fly leaves I already knew. I have long admired Amy Lowell and have read several of her booksx of her books of verse but none of her prose. Thank you for telling me about them and for giving me the John Keats which I had wanted to read but never hoped to own.

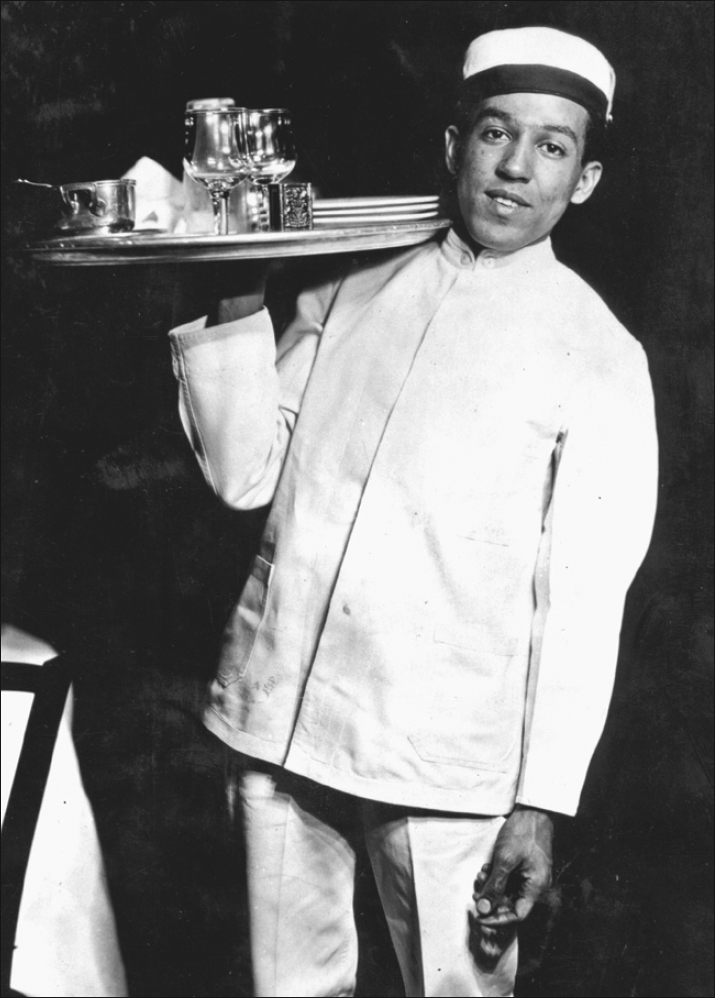

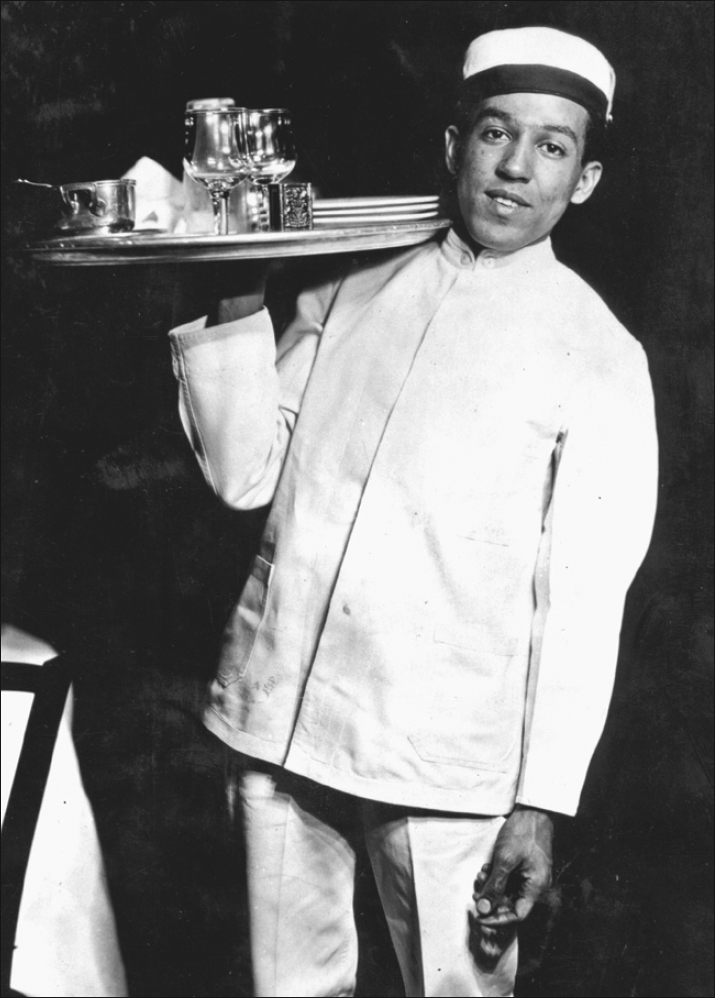

Taken soon after Hughes met Vachel Lindsay at the Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C., 1925 (illustration credit 8)

Thank you |for| the advice too. I am wary of lionizers. I <do> avoid invitations to receptions and teas. I’m afraid of public dinners. And people who tell me my verse is good I seldom believe. I see no factions to which I could belong and if I did I think should p<r>efer to walk alone,—to be myself.32 Don’t be afraid. I will not become conceited. If anything is important, it is my poetry not myself <me>. I do not want people <folks> to know me but if they know and like some of my poems I am glad. Perhaps the mission of an artist is to interpret beauty to the people,—the beauty within themselves. That is what I want to do, if I con<s>ciously want to do anything with poetry. I think I write it most because I like it. With it I seek nothing except not to make work out of it for so much |as| a line |of| propaganda for this cause or that. I want to keep it for the beauty<ful> thing it is.

Many of you of the “New Poetry” <movement> have, yourself, Carl Sandburg,33 Lola Ridge34 have helped me to feel the worth of expressing beauty. I thank you <all> for that. And I thank you again for your kindness and your generousity to me here.

May you make many more beautiful poems.

In all sincerity,

1749 S Street, N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

December 29, 1925.

My dear Mrs. Spingarn,35

I have been thinking a long time about what to say to you and I don’t know yet what it should be. But I believe this: That you do not want me to write to you the sort of things I would have to write to the scholarship people. I think you understand better than they the kind of person I am or surely you would not offer, in the quiet way you do, the wonderful thing you offer me.36 And if you were the scholarship people, although I might have to, I would not want to accept it. There would be too many conditions to fulfill and too many strange ideals to uphold. And somehow I don’t believe you want me to be true to anything except myself. (Or you would ask questions and outline plans.) And that is all I want to do,—be true to my own ideals. I hate pretending and I hate untruths. And it is so hard in other ways to pay the various little prices people attach to most of the things they offer or give.

And so I am happier now than I have been for a long time, more because you offer freely and with understanding, than because of the realization of the dream which you make come true for me.… Words are clumsy things. I hope you understand what I mean.

I do want to go to Lincoln in February. But I had not expected to be able to do so. Strange that in the middle of a seemingly hopeless winter you should be the person to make “trees grow all around with branches full of dreams.” But that is what you have done. You are surely the spirit of Christmas.

From February to June all expense at Lincoln may be covered by $200 or $225. A room deposit of $15 must be made before January 15th. The rest due the school may be paid upon entrance. I am very, very glad I am going to be able to go and the school wants me to come there.

I liked your little book immensely. You must have a number of good poems in order to be able to select twelve such very nice ones. I particularly like the Campanile one, L’Harmonie, and Change. Blue Water is lovely,—Round Lake, too,—and Pain is fine and true. It is an entirely beautiful little book. Thank you so much for letting me see it.

I am glad you liked my play for the children.37 I am sending you some new poems. One, A House in Taos, nobody understands.

If you’ve ever wanted anything, and then have stopped wanting it because you were sure you wouldn’t get it, then you maybe understand how glad I am, and how surprised, about going in February to Lincoln.

I am happy. What can I say to you to make you understand how very happy?

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

1749 S St., N.W.,

Washington, D.C.,

January 16, 1925 |1926|.

Dear Block,38

Thanks for your letter and those announcements of the reading. They are beauties. The program last night went off well and there was a fair sized crowd in spite of four definitely conflicting gatherings: the annual meeting of the Penguin Club from which I would have drawn the larger part of my white attendance, the annual meeting of the N.A.A.C.P. which subtracted from my colored audience, a student council party at Howard which held the students, and a big society ball. But it wasn’t so bad at that. There was a gang of teachers there and it took me longer to shake hands with everybody than it did to read my poems. We had a Blues interlude between the two sections of the reading,—that is between my jazz poems and The Weary Blues, and it went well. If you could get a real Blues piano player to play said Interlude at the New York reading it ought to be a wow! But he ought to be a regular Lenox Avenue Blues boy. The one we had here was too polished. The powers behind the tickets didn’t want the one I had chosen so they got a nice piano player who knew how to read Blues but not play them. Result: nice music, but nothing grotesque and sad at the same time, nothing primitive, and nothing very “different.” But maybe |Alain| Locke was right when he said our audience wouldn’t get Blues in the rough.…. The Blues in between relieves the monotony of so much reading and gives the proper atmosphere for my cabaret poems too. Would you like to have it in New York? Carl |Van Vechten| ought to be able to help you find a player and it would be a novelty. Poetry recitals are usually such darn dull affairs.

Locke is coming to New York tonight. If you see him don’t tell him I didn’t like his Blues player. <I told him.>

It’s one in the morning and I am very tired so I won’t write any more. I’ve gone back to bussing dishes again. Had to. Rent day came, passed, and had been long gone and I haven’t yet paid the lady.

I have an offer to read in Baltimore soon, also in Cleveland. And another in New York at the Civic Club on February 28th. So you see last night was good practice.

I like my book. I hope you will let me autograph a copy for you when I come to town.

Sincerely

Langston

<See Locke’s review of “The Weary Blues” for Palms39 which I am sending Mrs. Knopf.>

February 21, 1926

Lincoln University, Pa.

Dear Carl,

Because I wanted to have time to sit down and write you a decent letter, I haven’t written you at all. When I came back from New York I got in just in time to make a dinner engagement and from then on it was something every day and every night until I left. Negro History Week, with the demand for several readings, the public dinner at the “Y” in honor of |Alain| Locke’s book and mine, the before leaving parties given by people who wouldn’t have looked at me before the red, yellow, and black cover of the Weary Blues hit them in the eye, teas and telephones, and letters! Golly, I’m glad to get away from Washington.

Miguel Covarrubias’s illustration for the dust jacket of The Weary Blues (illustration credit 19)

I read last Saturday night in Baltimore for Calverton and “The Modern Quarterly” group.40 Had quite a nice time, stayed with them Sunday, and came on over here. They want to use some Blues, too.

I had a letter from Handy a couple of weeks ago about doing music for them.41 I have said nothing yet. We can talk it over this week-end when I come up. I think I’m reading for the Civic Club next Sunday.

Hall Johnson tried music for the Midwinter Blues. It’s the only one anyone has attempted. So Lament Over Love that you gave Rosamond,42 or any of the others, are free.…. I hear The Reviewer is no longer being published, but if it is, I’m glad you’ve given them five of my Blues.43 I hope that leaves some for a try at Poetry.44

I like the school out here immensely. We’re a community in ourselves. Rolling hills and trees and plenty of room. Life is crude, the dorms like barns but comfortable, food plain and solid, first bell at six-thirty, and nobody dresses up,—except Sunday. Other days old clothes and boots. The fellows are mostly strong young chaps from the South. They’ll never be “intellectuals,”—probably happier for not being,—but they have a good time. There are some exceptions, though. Several boys from Northern prep schools, two or three who have been in Europe, one who danced at the Club Alabam’. And then there are the ones who are going to be preachers. They’re having revival now. But nothing exciting, no shouting. No spirituals. You might find it amusing down here, tho, if you come. I room with the campus bootlegger. The first night I was here there was an all night party for a departing senior. So ribald did it become that the faculty heard about it and sent five Juniors “out in the world.” And are trying to find out who else was there. There is perhaps more freedom than at any other Negro school. The students do just about as they choose.

I think I’ll be in New York Friday. Of course, I want to come see you some time during the week-end, if you’ll let me. Miss Sergeant said something about my meeting Mable Dodge,45 too, and also this trip I am supposed to meet A’Lelia Walker.46 Last time she sent two books for me to autograph for her, but I didn’t get to see her.

Miguel47 and |Harry| Block and Walter48 made it very pleasant for me last trip, and I enjoyed the dinner and evening with you immensely.

Did Meta49 get her book? I sent it.

I’m anxious to see “Lulu Belle.”50 Some of my poems were in the Herald Tribune last Sunday, I heard, but I didn’t see it out here. However a check came so they must a been there.

Sincerely,

Langston

March 9, 1926

Lincoln University

Dear Harry

Nothing exciting’s happened since my return. Only I have been swamped by letters and have been working overtime to get them answered.… Still in love with the school and shall probably be eight years in graduating,—if I keep on cutting classes. By that time I’d be writing bucolics. That’s what one writes in the country, isn’t it?.… There’s a good review of my book in the Messenger this month. Have you seen it? Let me know if anything interesting comes out of the New York papers. And when the New Republic uses my Blues51.… I’m reading in Trenton Saturday and may get on up to New York, but don’t think so. Better save the bucks for Easter.…. Have been reading around the country-side with the college quartet making a few dollars and some country meals that didn’t taste so bad.… Have got a lot of clippings from the Southern papers (white papers) that have been publishing The Weary Blues. And even a front page story in a Georgia paper. Maybe you saw it.… Had to turn down the Indianapolis reading because we couldn’t get the dates fixed. Wasn’t anxious about going to that far-off town anyway. Walter White’s going out April 12th, they told me, to speak.

I’m enclosing the publicity dope I promised. Hope you will be able to get something out of it,—if you’re on publicity. Are you? It’s written up in outline for someone else to make the story from. Put in a good word for the school.

I’m reading in Cleveland on April 16th at the Y.M.C.A. auditorium. Could you get some advance publicity stories in the Cleveland papers? And would you send whatever advertising material you can, along with a picture, or a cut,—not that dopey looking one,—and a mat of Miguel |Covarrubias|’s cover such as you used on the New York bills to the man in charge: Mr. Sidney B. Thompson, 2216 East 40th Street, Cleveland, Ohio, as soon as possible. You might also have them asked how many books they wish to sell that evening.…. Could you have sent, too, a copy of the Borzoi Broadside52 with the Negro books checked to Mr. Peter Thomas, Lagos, Nigeria, British West Africa. They tell me he’s a big book buyer.… And please have half dozen Weary Blues sent to me here. Some of the boys want to buy them. Have them billed against my royalties.… And while you are sending out reading pictures might as well get one to Susie Elvie Bailey, Johnson College, Oberlin, Ohio, who is in charge of arrangements there53.…. I’m sorry to bother you with all of this.

Say Howdy to Covarrubias and help him finish that Blues drawing for Vanity Fair. And if review copies of Poppy Juice54 are being sent out to the world, or if there are any extra proof sheets lying around, I’d like to get a slant at it. If it touches South Sea folks or Negroes anywhere I could review it.

See you Easter—Sincerely—Langston

Dear Carl,

Yesterday brought a nice telegram from Lenore Ulric thanking me for The Weary Blues I sent her.55 This morning one of my classmates committed suicide, or tried to, with a razor. He isn’t dead yet. “Negroes are ’posed to cut one another with razors, but when they start to cuttin’ themselves, they’re gettin’ too much like ’fay folks,” is the most expressive comment of the student body on the case. I’m hoping the poor boy dies if he wants to, but naturally they had to tie his neck up and try to save him.

|W. C.| Handy sent me what I believe to be a good contract for setting music to my Blues. I’ll let you read it when I come up.… Hall Johnson’s singers came off well at their recital, he tells me. He said you were there.

Some copies of the second printing of my book came to me this week.… I read in the Times where Vachel Lindsay was giving a talk on it Tuesday in New York. Also see where it was put out of the library in Jacksonville, Fla.… The Times review last Sunday was interesting. I can’t see, though, why they chose “Poëme d’Automne” to illustrate my troubadour-like qualities.

In Trenton where I read for the colored Teacher’s Association a couple of weeks ago I called them “intellectuals” in saying that they might not “get” my cabaret poems, but that night they retaliated by giving a Charleston party to show me how wild they could be.… Are you still in New York! I think I’ll be in town Thursday for the Easter week-end. I’m due to read at Martin’s Book Shop on Friday. Will there be any chance of meeting Rebecca West?56 I’d like to. I think I’ll be staying at Hall Johnson’s, but I’ll give you a ring soon as I get in. I’m broke but hope to get a ride up on the mushroom trucks that go to market nightly, or else borrow from the school. They are good about lending money out here. Lincoln is more like what home ought to be than any place I’ve ever seen.

I hope “Nigger Heaven” ’s successfully finished.57 It is, isn’t it?

Tulipanes à tu,

Langston

March 26, 1925 |1926|

Lincoln University, PA

Lincoln University, Pa.,

April 27, 1926.

Dear Mrs. Knopf,58

I am sorry about being so late in returning the Bryn Mawr Alumnae book which you sent me to sign but it came while I was away,—Cleveland, Oberlin, and Indianapolis, giving readings, and a slight auto accident kept me out there a few days overtime to get patched up. The book was sent, too, to my Washington address, which I am no longer using, so please have it taken off your files.

The readings were all successful. Good crowds, good publicity in the local papers, an interview in Cleveland, forty-five books sold in Indianapolis, and return dates for next winter. I met Mary Rennels of Burrow’s in Cleveland, whom I think you know, and signed several books for Beach’s Book Shop in Indianapolis.

The New Orleans Times Picayune devotes nearly a column to a review of my book (April 4th).59 Unusual for a Southern paper I thought. Several other good reviews have come in recently.

Did you find the foreign list of folks to whom I suggested sending books? I hope so. “The Weary Blues” and “Jazzonia” appeared in French translation in an excellent article on Negro poetry recently in a Liège paper. The colored papers and magazines copy foreign write-ups, so they make good publicity over here.

I’d like, if there is another printing, to have corrected an error made in the second printing. In the poem “Negro Dancers” (this page) the quotation marks (“) should be placed after the sixth line of the poem, at the end of the verse, and not after the third line.

And would you please have sent me, here at the school, six copies of “The Weary Blues.” Merci.

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

Tuesday,

Lincoln University, Pa.

|January 1927|

Dear Locke,

Here’s Mulatto.60 My book will be ready this week.61 Then you will have all the poems from which to make a selection. Exams begin soon so I won’t be in New York anymore until the 29th. Will you be there then, too?

Did I tell you about the Knopf’s party New Year’s? Yasha Heifitz,62 Ethel Barrymore,63 Steffansson,64 Fannie Hurst,65 and almost everybody was there.

I’m doing six short stories with the West African coast and a steamship as the background. I haven’t been able to do anything else but write on them for the past week. Two are finished. I wish the ideas hadn’t struck me just at exam time,—and a million of unanswered letters lying around, too.

If you want to do me a grand favor

![]() you can mail me a ten $ until the first when my royalties come due again. Otherwise my strength may fail me, and I won’t get my stories done. (Where do you suppose I can sell them? They’re about sailors, and missionaries’ daughters, and port-town girls.)66

you can mail me a ten $ until the first when my royalties come due again. Otherwise my strength may fail me, and I won’t get my stories done. (Where do you suppose I can sell them? They’re about sailors, and missionaries’ daughters, and port-town girls.)66

Hope I’ll see you in New York.

Sincerely,

Langston

|February 1927|

Dear Walter,

Here’s a note for your publicity service,—I’ve been invited to read my poems at Walt Whitman’s house in Camden on March first. Invitation comes from the Walt Whitman Foundation and because I admire his work so much it seemed a great honor for me to read my humble poems in the house where he lived and worked.

“Fine Clothes” has been getting some good reviews.67

Hope you’ve gotten rested up. You looked tired when I saw you.

“Hello” to Jane and Gladys.68

Langston

Lincoln University, Pa.

May 28, 1927.

Dear Claude,

It’s a shame to answer your letter on such paper,—that mighty welcome letter I had been waiting for so damn long,—but I’m in the midst of packing up to leave here for The South,—Nashville (Fisk), Marshall and Hollister, Texas, where I’m to read poetry to student groups, and then “on the bum” through the flood district69 to New Orleans, and then back up to New York (working my way on the fruit-boats). This will take all summer, I guess, and ought to yield some grand experiences. I’ve never been South before, and I’ve always wanted to go. Am still pretty broke, but what I make from the readings ought to help me through. They only last (I’m glad to say) till June 15th, then I’m free for the summer …… That’s great about your novel. I hear the jacket has already been designed by Aaron Douglas.70 I’m surely glad you’re better and things are going pretty well again. I know how it is about writing, and didn’t think you had forgotten me at all,—only I was worried about you,—and ashamed because I’ve been broke all the time, too, and couldn’t help you any.… Tried writing lyrics for Broadway shows but none of them have been put on so far.… The best of the lot, now in rehearsal, I had to drop on account of school and their unwillingness to give an advance to make it worthwhile losing a semestre. The theatre is too unsure a place to work in.… Thanks for what you say about my book |Fine Clothes to the Jew|. Colored critics razed it to death, but the big papers and magazines were very kind. It goes into another edition this month. “Weary Blues” will always be the most popular book, I think. It’s more “poetically” poetic.…. Didn’t leave N.Y. last summer.… Hope you do come home soon. Lord knows I’d like to see you.… Write c/o Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 730 Fifth Avenue, N. Y. When you get this I’ll be in Texas which must be a lonesome place! Think about me.

Good luck, ole boy!

Langston

Memphis,71

June 11, |1927|

Dear Carl,

Last night at a revival I heard what was to me a brand new train song with this refrain:

“We’s bound fo’ de

heavenly depot,

“Where de angel

porters wait.”

It’s the first time I’d ever heard angels referred to as Red Caps!

Beale Street is not what it used to be according to its present inhabitants. But it’s still full of Blues coming out of alleys and doorways. Yesterday I spent the afternoon in a barrel house at 4th and Beale where three musicians, all of whom claimed to have been with |W. C.| Handy, played all kinds of Blues until they were overcome with gin. And the girl who won the amateur contest at the vaudeville show last night sang a Flood Blues something like Bessie |Smith|’s on the record.

“The National Grand United Order of Wise Men and Women of the World” meets nightly just across the street in front of my windows, over the Yellow Pine Cafe. The “P. Wee Saloon” is just down the block.

Tomorrow I’m going to Vicksburg, Miss. and the flood region, then on to New Orleans. My address there for mail will be

3444 Magnolia St.,

c/o Mrs. Jackson.

“Ain’t gonna sing it no mo’,”—

Langston

Havana, Cuba,72

July 15, 1927.

Dear Carl,

Havana is not all it might be at this time of year, yet I’ve rather enjoyed it so far. There is a marvelous Chinatown here where I went last night with some of the Chinese fellows from our crew. They have cousins there waiting to be smuggled into New Orleans or New York. We had some very good food and a jar of Chinese whiskey (and I’m bringing a jar to you, if it ever gets there. It ought to make grand cocktails.—I hope you haven’t stopped drinking again.) Then we went to a house where there are girls in little shuttered rooms built around an open courtyard. There are three floors, and literally hundreds of Chinese walking around and around looking at them. It’s right near the Chinese theatre and is always crowded.… I am the only “colored” colored person on my ship. The crew is all mixed up,—Spaniards, German, South Americans, Philipinos and Chinese. The confusion of languages is amusing. We are loading sugar here and I think we’re going directly back to New Orleans in a few days.… Just the day before I sailed I met Walter |White|’s brother-in-law and he told me about the little new Carl.73 Great!.… I’m glad it was a boy and that it has been so well named.…. Walter’s brother-in-law is a very nice fellow. I’m going to see him when I go back.…. By the way, I was in New Orleans three weeks without meeting a single “dicty” person,—then someone took me to the Aristocrats Club, I believe the name was, and then invitations began to come in to go places,—and the next day I got this job to Cuba,—so I’m saved.… There’s a street called Poydras Street where one can hear Blues all night long,—and most of the day, too. A stevedore called Big Mac is particularly good and seems to know a thousand verses. I never heard any of these before:

Did you ever see peaches

Growin’ on a watermelon vine?

Did you ever see peaches

On a watermelon vine?

Did you ever see a woman

I couldn’t take for mine?

If you shake that thing I’ll

Buy you a diamond ring.

If you shake that thing I’ll

Buy you a diamond ring,—

But if you don’t shake it

I ain’t gonna buy you a thing.

Yo’ windin’ and yo grindin’

Don’t have no ’fect on me.

Yo’ windin’ and grindin’

Don’t have no ’fect on me

Cause I can wind and grind

Like a monkey climbin’ a cocoanut tree.

Throw yo’ arms around me

Like de circle round de sun.

Throw yo’ arms around me

Like de’ circle round de sun

and tell me, pretty mama,

How you want yo’ lovin’ done.

I lived for a week on Rampart Street which is the Lenox Avenue down there, then I moved into the Vieux Carré just in front of St. Louis Cathedral, in a house with stone floors, wooden blinds, an open court and balconies,—a very old place and quite charming.…. To me, New Orleans, seems much like a southern European city. Everything is cheap, and everything is wide open. There is good wine at 30¢ a bottle and even whiskey at 5¢ a drink in some bars.… I met the caretakers of the old St. Louis Cemetery,—Creole fellows who do little work and can be found any afternoon behind some cool tomb, with a few bottles of white wine at hand. They took me to meet their families and to several jolly Creole parties and gumbo suppers.

Write to me c/o Mrs. A. C. Johnson, 3444 Magnolia Street, N.O. or else to Tuskegee after July 25….. Wish you’d send me Eddie Wasserman’s address, too, so I can drop him a card.74 I’m not sure I remember it correctly. Tell him “hello” for me.

Pañal and Bacardi to you,

Langston

P.S. You can buy all sorts of voodoo stuff in Poydras Street, too,—Follow Me Powder, War and Confusion Dust, Black Cats’ Blood, etc. I thought I’d bring you a bottle of Good Luck Water, but I think you’d rather have the Chinese licker.

Carl Van Vechten, 1932 (illustration credit 10)

1 On October 5, after a tough month stranded in Genoa, Hughes was put aboard the West Cawthorn as a “consular” passenger working for the ship in return for his passage home. Arriving in Harlem in late November, he went to see Countee Cullen, who gave Hughes a letter from his mother, Carrie Clark. In it, she invited him to join her in Washington, D.C., where she was then living with prosperous relatives. One of her uncles, John Mercer Langston (1829–1897), had been an abolitionist, a U.S. congressman, a U.S. diplomat in Haiti, and the first dean of the Howard University law school.

2 Hughes had taken a job at the Washington Sentinel, a weekly for which he sold advertising space on commission. He did poorly and soon left the newspaper.

3 Quitting his job at the Washington Sentinel, Hughes worked in a wet-wash laundry and as a pantry man in an oyster house. He then joined the staff of Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950), a Harvard-trained African American historian, a founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, and the editor of its Journal of Negro History. He also founded, in 1926, Negro History Week (which later became Black History Month). Hughes’s main task was to help prepare for publication Woodson’s current project, Free Negro Heads of Families in the United States in 1830, a list of some thirty thousand names.

4 Carl Van Vechten (1880–1964), a prominent writer suddenly enthralled by black culture, first met Hughes at a benefit party on November 19, 1924, in Harlem. He later introduced Hughes to Alfred and Blanche Knopf (of Alfred A. Knopf, Van Vechten’s main publisher). Van Vechten persuaded them to bring out Hughes’s first book of poems, The Weary Blues (1926). He also befriended and promoted the careers of several other major figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including Zora Neale Hurston and Wallace Thurman.

5 Van Vechten’s essay “The Black Blues: Negro Songs of Disappointment in Love: Their Pathos Hardened with Laughter” was published in Vanity Fair (August 1925) as part of a series of articles on African American songs that he wrote for the magazine.

6 Hughes writes about George in The Big Sea.

7 The comic strip Krazy Kat, created by George Herriman in 1913, ran in many American newspapers through the mid-1940s.

8 The Blind Bow-Boy (1923) and Peter Whiffle: His Life and Works (1922) are novels by Van Vechten.

9 Hughes’s autobiographical essay “The Fascination of Cities” won second prize in the August 1925 Crisis essay competition. The Crisis published it in January 1926.

10 Born Miklós Mandl, Nickolas Muray (1892–1965) was a Hungarian-born photographer based in New York City. By the mid-1920s, he had become widely admired for his portraits in Harper’s Bazaar and elsewhere.

11 John Peale Bishop (1892–1944), a former managing editor of Vanity Fair, published many critical essays, four books of poetry, a volume of short stories, and a novel.

12 Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1950), deeply admired as a poet by Hughes, published prose under the pseudonym Nancy Boyd.

13 Clara Smith (1894–1935), a groundbreaking African American blues singer, was sometimes called “Queen of the Moaners.”

14 In 1925, blues singer Ozie McPherson recorded the songs “You Gotta Know How” and “Outside of That He’s All Right with Me” for Paramount Records in Chicago.

15 Van Vechten’s Firecrackers: A Realistic Novel (1925) features Campaspe Lorillard, who also appears in his novels The Blind Bow-Boy (1923) and Nigger Heaven (1926).

16 Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960), from Eatonville, Florida, was an African American folklorist, playwright, and fiction writer who studied anthropology at Columbia University under Franz Boas and received a BA from Barnard College in 1928. Her most influential works include the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) and her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road (1942).

17 Sidney Howard (1891–1939) won the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for his play They Knew What They Wanted.

18 Van Vechten closed his letter to Hughes of June 4 with the wish “pansies and marguerites to you!” Similar closing flourishes are common throughout their correspondence.

19 Hughes worked as a busboy at the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington at a salary of $55 per month.

20 The iconoclastic magazine The American Mercury was founded by H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan in 1924. Van Vechten contributed several articles to the periodical in 1925 and 1926, but it published none of Hughes’s poems.

21 Van Vechten’s The Tiger in the House was published in 1922.

22 Irvin C. Miller (1884–1967), a Fisk University graduate, was a writer, producer, and actor. He wrote the book for and performed in the musical comedy Liza (1923).

23 “Hotsy-Totsy” alludes to La Revue Nègre, an all-black revue produced by Caroline Dudley Reagan that made Josephine Baker an overnight star in Paris. The show opened there at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on October 2, 1925.

24 Four of Hughes’s poems, including “Fantasy in Purple,” appeared with an introduction by Van Vechten in the September 1925 issue of Vanity Fair.

25 Founded in 1854, Lincoln University was the first historically black college or university to offer degrees. With an all-white faculty, it attracted some of the best students in the United States and beyond. Its many distinguished alumni include Justice Thurgood Marshall of the U.S. Supreme Court (1908–1993) and Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972), the first president of Ghana.

26 Opportunity magazine was founded by the National Urban League in 1923 and edited initially by Charles S. Johnson (on Johnson, see note for letter of February 27, 1928).

27 The Messenger, a socialist monthly magazine edited by A. Philip Randolph (1889–1979) and Chandler Owen (1889–1967), ran from 1917 to 1928. Hughes’s first published short stories (apart from those in his high school magazine), as well as sixteen of his poems, appeared in The Messenger.

28 The Workers Monthly was a leftist magazine published by the Chicago-based Workers Party from November 1924 until February 1927. Hughes published five poems in the journal in 1925: “Drama for Winter Night” in March; “Poem to a Dead Soldier,” “Park Benching,” and “Rising Waters” in April; and “To Certain ‘Brothers’ ” in July.

29 Acting at once, the dean wrote on October 22 to admit Hughes.

30 In November 1925, when the famed poet Vachel Lindsay (1879–1931) came to the Wardman Park Hotel to give a public reading, Hughes quietly slipped him the texts of three poems. On stage, Lindsay announced dramatically that he had discovered a genuine poet working as a busboy at the hotel. As proof, he then read aloud the three poems. The resulting publicity included a widely circulated photograph of Hughes hoisting a tray on the job.

31 The poet Amy Lowell (1874–1925) had published that year a two-volume biography of John Keats (1795–1821). Lindsay elaborately inscribed a copy as a gift to Hughes.

32 In his message (dated December 6, 1925) handwritten on the fly leaves of the biography, Lindsay warned Hughes: “Don’t let lionizers stampede you. Hide and write and think. I know what factions can do. Beware of them. I know what flatterers can do. Beware of them.”

33 The poet Carl Sandburg (1878–1967) was already noted for his lively use of free verse and American vernacular forms, including blues and jazz. He later wrote the biographies Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926) and the Pulitzer Prize–winning Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939). He was a major early influence on Hughes, who later recalled him as “my guiding star.”

34 Lola Ridge (1873–1941) was a well-known poet and anarchist whose first collection, The Ghetto and Other Poems, appeared in 1918.

35 The daughter of a rich businessman, Amy Einstein Spingarn (1883–1980) was an artist and a poet (she published a poem in 1924 in The Crisis under the name Amy Einstein) who had studied art history, literature, and foreign languages at Barnard College and Columbia University and in Europe. She successfully proposed marriage to Joel Elias Spingarn (1875–1939), at that time a stellar professor of literature at Columbia University, with whom she would have four children. She quietly enlisted in the suffragette and civil rights causes after he left Columbia in 1911 and became an NAACP leader. Hughes sent her a thank-you note after winning two cash prizes in the August 1925 Crisis literary contest that she had funded. Mrs. Spingarn then invited him to her Manhattan home at 9 West Seventy-third Street. At this meeting, Hughes told her about his wish to attend historically black Lincoln University, and about his need for money to do so.

36 Amy Spingarn surprised Hughes with a letter offering him a loan of $300 to attend Lincoln. Her letter reached Hughes on Christmas Eve 1925.

37 “The Gold Piece,” Hughes’s one-act play for children, appeared in the June 1921 edition of The Crisis.

38 Henry C. Block, known as “Harry,” was a senior editor at Knopf.

39 Palms, an American poetry magazine, was published in Mexico from 1923 to 1940. The work of several writers of the Harlem Renaissance appeared there.

40 V. F. Calverton (1900–1940), a Baltimore leftist (whose real name was George Goetz), founded the influential Modern Quarterly in 1923 and edited it until his death. Calverton invited Hughes to give a public reading in Baltimore, which Hughes did on Saturday, February 13. He later sent Calverton several blues poems, but Modern Quarterly used only “Listen Here Blues” (May–July 1926).

41 William Christopher Handy (1873–1958), an African American composer and musician, is often called the “Father of the Blues” because of his historic standardization of this form when he published “Memphis Blues” (1912). In 1914, Handy wrote the renowned “St. Louis Blues.” He set Hughes’s “Golden Brown Blues” to music in 1927.

42 John Rosamond Johnson (1873–1954), a singer, pianist, and composer, was the brother of James Weldon Johnson, also a skilled musician as well as a diplomat and writer. In 1899 the brothers composed “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” which is often called the black American national anthem.

43 From 1924 to 1925, Paul Green (1894–1981) and his wife, Elizabeth, edited The Reviewer in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Green was a noted white playwright who explored African American themes with success; his In Abraham’s Bosom won the Pulitzer Prize in 1927. The Greens turned The Reviewer into one of the few avant-garde, progressive journals in the South. Later it was folded into The Southwest Review of Dallas.

44 The Chicago-based monthly Poetry: A Magazine of Verse published four blues or blues-influenced poems by Hughes in November 1926 (“Suicide,” “Hard Luck,” “Po’ Boy Blues,” and “Red Roses”).

45 Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant (1881–1965), a journalist, was a friend of Mabel Dodge Luhan (1879–1962), herself a patron of the arts and a friend of Van Vechten. Although Hughes’s bleakly modernist poem “A House in Taos” is often taken to be about Luhan’s home there, it was published in November 1925, long before he had a chance to meet her or see the house.

46 A’Lelia Walker (1885–1931), daughter of Madame C. J. Walker (1867–1919), was probably the richest black woman in America in the 1920s, thanks to the success of her late mother’s pioneering hair-care business aimed at the needs of black women. A patron of the Harlem Renaissance, A’Lelia Walker established in a part of her Harlem home a tearoom salon named “The Dark Tower,” after Countee Cullen’s popular poem “From the Dark Tower.”

47 Miguel Covarrubias (1904–1957) was a popular Mexican artist and caricaturist whose work appeared regularly in The New Yorker and Vanity Fair. Covarrubias, at the behest of Van Vechten, illustrated the dust jacket of Hughes’s The Weary Blues.

48 Blond and blue-eyed but proudly African American, the Atlanta-born Walter White (1893–1955) was a major figure in the NAACP. From 1931 to 1955 he led the organization. He was also a writer. In 1924 Knopf published The Fire in the Flint, his novel about racial violence in the South.

49 Hughes refers to Meda Fry, the Van Vechtens’ housekeeper.

50 In February 1926, the Broadway production by David Belasco (1853–1931) of Lulu Belle, a melodrama of Harlem street life, featured the white actress Lenore Ulric appearing in blackface along with several black actors. The play contributed to Harlem’s sudden popularity with adventurous whites.

51 The New Republic published “Midwinter Blues,” “Gypsy Man,” and “Ma Man” in its April 14, 1926, issue.

52 Blanche Knopf designed the original Borzoi, or Russian wolfhound, as the logo for Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. The Borzoi Broadside was a monthly magazine aimed at publicizing Knopf books.

53 Susie Elvie Bailey (1903–1996) had invited Hughes to speak at Oberlin College. In 1928, she hosted him again at Hampton Institute in Virginia, where she taught music. There she introduced him to another young instructor, Louise Thompson (Patterson), who became one of his lifelong friends. In 1932, Bailey married the noted black theologian Howard Thurman (1899–1981).

54 Probably “Poppy Juice,” a dramatic narrative poem by Genevieve Taggard (1894–1948). First published in Words for the Chisel (Knopf, 1926), “Poppy Juice” tells a story of hula girls, smugglers, opium, and leprosy.

55 Lenore Ulric (1892–1970) had recently played the lead in Lulu Belle (see Hughes to Van Vechten, February 21, 1926).

56 Rebecca West (1892–1983) was an English novelist whose work was published frequently in The New Republic and The New Yorker.

57 Knopf published Van Vechten’s controversial, best-selling novel of Harlem life, Nigger Heaven, later that year.

58 The daughter of a Viennese-born jeweler in New York, Blanche Wolf Knopf (1894–1966) was vice president of the publishing house named after her husband, who incorporated the firm with her in 1918. She was crucial to its success, seeking out foreign authors such as Sigmund Freud, Albert Camus, Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, André Gide, and Thomas Mann. She remained Hughes’s editor there until she succeeded Alfred as president of the firm in 1957.

59 The Times-Picayune, which traces its origins to 1837, is a distinguished, white-owned newspaper based in New Orleans.

60 Hughes’s poem “Mulatto,” on one of the most compelling themes in his writings, appeared in The Saturday Review of Literature on January 29, 1927. It helped to shape a major short story (“Father and Son”) in The Ways of White Folks (1934), his Broadway play Mulatto (1935), and his Broadway opera The Barrier (1950).

61 Fine Clothes to the Jew, Hughes’s second book of poems, published by Knopf in January 1927.

62 Jascha Heifetz (1901–1987) was a Russian-born American violin virtuoso.

63 Ethel Barrymore (1879–1959), an Academy Award–winning actress and Broadway performer, was a member of one of America’s best-known acting families.

64 Probably Harold Jan Stefansson, the nephew of the explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson (1879–1962). The younger Stefansson lived at this time in Harlem with his close friend Wallace Thurman at 267 West 136th Street. Zora Neale Hurston dubbed their home “Niggeratti Manor” because it attracted many of the younger black writers and artists. Stefansson helped Thurman produce the only issue of the magazine Fire!! (1926).

65 Fannie Hurst (1889–1968) was an American novelist most famous perhaps for her Imitation of Life (1933), about a pale-skinned “black” woman who tragically defies and denies her mother in passing for white. Zora Neale Hurston worked as Hurst’s assistant during Hurston’s early years in New York.

66 These stories were “Luani of the Jungles” (Harlem, November 1928) and, appearing in The Messenger: “Bodies in the Moonlight” (April 1927); “The Young Glory of Him” (June 1927); and “The Little Virgin” (November 1927).

67 In a wan reference to pawnbrokers serving the black poor, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927) took its title from the last two lines of the first stanza of Hughes’s poem “Hard Luck.” He later conceded that “it was a bad title, because it was confusing and many Jewish people did not like it. I don’t know why the Knopfs let me use it, since they were very helpful in their advice about sorting out the bad poems from the good, but they said nothing about the title.” In fact (unknown to him) the Knopfs, who were Jewish, disliked the title but gave in after Van Vechten vigorously defended it. Almost certainly, as with The Weary Blues, Van Vechten himself had suggested the title. While reviews by whites of Fine Clothes to the Jew were positive, most notices in the African American press were extremely hostile because of its championing of lower-class black culture.

68 Gladys White was married to Walter White, and Jane was their daughter.

69 In April 1927, the swollen Mississippi River flooded more than 23,000 square miles in the most destructive inundation in American history.

70 Aaron Douglas (1899–1979) is the illustrator, painter, and muralist most closely identified with the Harlem Renaissance. He designed the cover of Wallace Thurman’s magazine Fire!! in 1926 and the dust jacket for McKay’s novel Home to Harlem (1928).

71 After reading his poems in June at Commencement at Fisk University in Nashville, Hughes stopped in Memphis to explore Beale Street and the notorious blues district around it. He also visited Cuba and New Orleans, before returning north in a car driven by Zora Neale Hurston.

72 Eager to see Cuba, Hughes sailed from New Orleans to Havana as a mess boy aboard the freighter Munloyal. He returned to New Orleans on July 20.

73 Walter and Gladys White had named their baby Carl in honor of their friend Van Vechten.

74 Eddie Wasserman, reputedly an heir to a banking fortune, was a noted bon vivant and a close friend of Carl Van Vechten. In The Big Sea, Hughes mentions the lively interracial parties that Wasserman hosted.