Inner Product Spaces, Orthogonality

7.1 Introduction

The definition of a vector space V involves an arbitrary field K. Here we first restrict K to be the real field R, in which case V is called a real vector space; in the last sections of this chapter, we extend our results to the case where K is the complex field C, in which case V is called a complex vector space. Also, we adopt the previous notation that

Furthermore, the vector spaces V in this chapter have finite dimension unless otherwise stated or implied.

Recall that the concepts of “length” and “orthogonality” did not appear in the investigation of arbitrary vector spaces V (although they did appear in Section 1.4 on the spaces Rn and Cn). Here we place an additional structure on a vector space V to obtain an inner product space, and in this context these concepts are defined.

7.2 Inner Product Spaces

We begin with a definition.

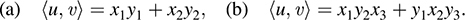

DEFINITION: Let V be a real vector space. Suppose to each pair of vectors u, υ ∈ V there is assigned a real number, denoted by  u, υ

u, υ . This function is called a (real) inner product on V if it satisfies the following axioms:

. This function is called a (real) inner product on V if it satisfies the following axioms:

[I1] (Linear Property):  au1 + bu2, υ

au1 + bu2, υ = a

= a u1, υ

u1, υ + b

+ b  u2, υ

u2, υ .

.

[I2] (Symmetric Property):  u, υ

u, υ =

=  υ, u

υ, u .

.

[I3] (Positive Definite Property):  u, u

u, u ≥ 0.; and

≥ 0.; and  u, u

u, u = 0 if and only if u = 0.

= 0 if and only if u = 0.

The vector space V with an inner product is called a (real) inner product space.

Axiom [I1] states that an inner product function is linear in the first position. Using [I1] and the symmetry axiom [I2], we obtain

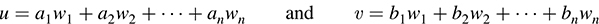

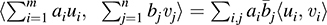

That is, the inner product function is also linear in its second position. Combining these two properties and using induction yields the following general formula:

That is, an inner product of linear combinations of vectors is equal to a linear combination of the inner products of the vectors.

EXAMPLE 7.1 Let V be a real inner product space. Then, by linearity,

Observe that in the last equation we have used the symmetry property that  u, υ

u, υ =

=  υ, u

υ, u .

.

Remark: Axiom [I1] by itself implies  0, 0

0, 0 =

=  0υ, 0

0υ, 0 = 0

= 0 υ, 0

υ, 0 = 0. Thus, [I1], [I2], [I3] are equivalent to [I1], [I2], and the following axiom:

= 0. Thus, [I1], [I2], [I3] are equivalent to [I1], [I2], and the following axiom:

If u ≠ 0, then

If u ≠ 0, then  u, u

u, u is positive.

is positive.

That is, a function satisfying  is an inner product.

is an inner product.

Norm of a Vector

By the third axiom [I3] of an inner product,  u, u

u, u is nonnegative for any vector u. Thus, its positive square root exists. We use the notation

is nonnegative for any vector u. Thus, its positive square root exists. We use the notation

This nonnegative number is called the norm or length of u. The relation ||u||2 =  u, u

u, u will be used frequently.

will be used frequently.

Remark: If ||u|| = 1 or, equivalently, if  u, u

u, u = 1, then u is called a unit vector and it is said to be normalized. Every nonzero vector υ in V can be multiplied by the reciprocal of its length to obtain the unit vector

= 1, then u is called a unit vector and it is said to be normalized. Every nonzero vector υ in V can be multiplied by the reciprocal of its length to obtain the unit vector

which is a positive multiple of υ. This process is called normalizing υ.

7.3 Examples of Inner Product Spaces

This section lists the main examples of inner product spaces used in this text.

Euclidean n-Space Rn

Consider the vector space Rn. The dot product or scalar product in Rn is defined by

where u = (ai) and υ = (bi). This function defines an inner product on Rn. The norm ||u|| of the vector u = (ai) in this space is as follows:

On the other hand, by the Pythagorean theorem, the distance from the origin O in R3 to a point P(a, b, c) is given by  . This is precisely the same as the above-defined norm of the vector υ = (a, b, c) in R3. Because the Pythagorean theorem is a consequence of the axioms of Euclidean geometry, the vector space Rn with the above inner product and norm is called Euclidean n-space. Although there are many ways to define an inner product on Rn, we shall assume this inner product unless otherwise stated or implied. It is called the usual (or standard) inner product on Rn.

. This is precisely the same as the above-defined norm of the vector υ = (a, b, c) in R3. Because the Pythagorean theorem is a consequence of the axioms of Euclidean geometry, the vector space Rn with the above inner product and norm is called Euclidean n-space. Although there are many ways to define an inner product on Rn, we shall assume this inner product unless otherwise stated or implied. It is called the usual (or standard) inner product on Rn.

Remark: Frequently the vectors in Rn will be represented by column vectors—that is, by n × 1 column matrices. In such a case, the formula

defines the usual inner product on Rn.

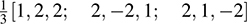

EXAMPLE 7.2 Let u = (1, 3, −4, 2), υ = (4, −2, 2, 1), w = (5, −1, −2, 6) in R4.

(a) Show  3u − 2υ, w

3u − 2υ, w = 3

= 3 u, w

u, w − 2

− 2 υ, w

υ, w .

.

By definition,

Note that 3u − 2υ = (−5, 13, −16, 4). Thus,

As expected, 3 u, w

u, w − 2

− 2 υ, w

υ, w = 3(22) − 2(24) = 18 =

= 3(22) − 2(24) = 18 =  3u − 2υ, w

3u − 2υ, w .

.

(b) Normalize u and υ.

By definition,

We normalize u and υ to obtain the following unit vectors in the directions of u and υ, respectively:

Function Space C[a, b] and Polynomial Space P(t)

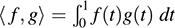

The notation C[a, b] is used to denote the vector space of all continuous functions on the closed interval [a, b]—that is, where a ≤ t ≤ b. The following defines an inner product on C[a, b], where f(t) and g(t) are functions in C[a, b]:

It is called the usual inner product on C[a, b].

The vector space P(t) of all polynomials is a subspace of C[a, b] for any interval [a, b], and hence, the above is also an inner product on P(t).

Consider f(t) = 3t − 5 and g(t) = t2 in the polynomial space P(t) with inner product

(a) Find  f, g

f, g .

.

We have f(t)g(t) = 3t3 − 5t2. Hence,

We have [f(t)]2 = f(t)f(t) = 9t2 − 30t + 25 and [g(t)]2 = t4. Then

Therefore,  .

.

Matrix Space M = Mm,n

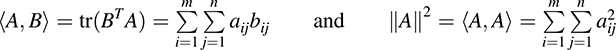

Let M = Mm,n, the vector space of all real m × n matrices. An inner product is defined on M by

where, as usual, tr( ) is the trace—the sum of the diagonal elements. If A = [aij] and B = [bij], then

That is,  A, B

A, B is the sum of the products of the corresponding entries in A and B and, in particular,

is the sum of the products of the corresponding entries in A and B and, in particular,  A, A

A, A is the sum of the squares of the entries of A.

is the sum of the squares of the entries of A.

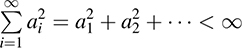

Hilbert Space

Let V be the vector space of all infinite sequences of real numbers (a1, a2, a3,…) satisfying

that is, the sum converges. Addition and scalar multiplication are defined in V componentwise; that is, if

then

An inner product is defined in υ by

The above sum converges absolutely for any pair of points in V. Hence, the inner product is well defined. This inner product space is called l2-space or Hilbert space.

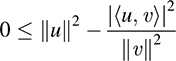

7.4 Cauchy–Schwarz Inequality, Applications

The following formula (proved in Problem 7.8) is called the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality or Schwarz inequality. It is used in many branches of mathematics.

THEOREM 7.1: (Cauchy–Schwarz) For any vectors u and υ in an inner product space V,

Next we examine this inequality in specific cases.

(a) Consider any real numbers a1, …, an, b1, …, bn. Then, by the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality,

That is, (u · υ)2 ≤ ||u||2||υ||2, where u = (ai) and υ = (bi).

(b) Let f and g be continuous functions on the unit interval [0, 1]. Then, by the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality,

That is, ( f, g

f, g )2 ≤ ||f||2||υ||2. Here V is the inner product space C[0, 1].

)2 ≤ ||f||2||υ||2. Here V is the inner product space C[0, 1].

The next theorem (proved in Problem 7.9) gives the basic properties of a norm. The proof of the third property requires the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

THEOREM 7.2: Let V be an inner product space. Then the norm in V satisfies the following properties:

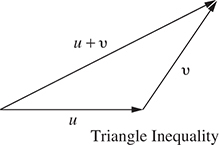

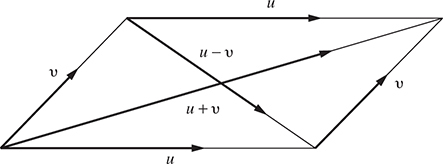

The property [N3] is called the triangle inequality, because if we view u + υ as the side of the triangle formed with sides u and υ (as shown in Fig. 7-1), then [N3] states that the length of one side of a triangle cannot be greater than the sum of the lengths of the other two sides.

Angle Between Vectors

For any nonzero vectors u and υ in an inner product space V, the angle between u and υ is defined to be the angle θ such that 0 ≤ θ ≤ π and

By the Cauchy–Schwartz inequality, −1 ≤ cos θ ≤ 1, and so the angle exists and is unique.

(a) Consider vectors u = (2, 3, 5) and υ = (1, −4, 3) in R3. Then

Then the angle θ between u and υ is given by

Note that θ is an acute angle, because cos θ is positive.

(b) Let f(t) = 3t − 5 and g(t) = t2 in the polynomial space P(t) with inner product  . By Example 7.3,

. By Example 7.3,

Then the “angle” θ between f and g is given by

Note that θ is an obtuse angle, because cos θ is negative.

7.5 Orthogonality

Let V be an inner product space. The vectors u, υ ∈ V are said to be orthogonal and u is said to be orthogonal to υ if

The relation is clearly symmetric—if u is orthogonal to υ, then  υ, u

υ, u = 0, and so υ is orthogonal to u. We note that 0 ∈ V is orthogonal to every υ ∈ V, because

= 0, and so υ is orthogonal to u. We note that 0 ∈ V is orthogonal to every υ ∈ V, because

Conversely, if u is orthogonal to every υ ∈ V, then  u, u

u, u = 0 and hence u = 0 by [I3]. Observe that u and υ are orthogonal if and only if cos θ = 0, where θ is the angle between u and υ. Also, this is true if and only if u and υ are “perpendicular”—that is, θ = π/2 (or θ = 90º).

= 0 and hence u = 0 by [I3]. Observe that u and υ are orthogonal if and only if cos θ = 0, where θ is the angle between u and υ. Also, this is true if and only if u and υ are “perpendicular”—that is, θ = π/2 (or θ = 90º).

(a) Consider the vectors u = (1, 1, 1), υ = (1, 2, −3), w = (1, −4, 3) in R3. Then

Thus, u is orthogonal to υ and w, but υ and w are not orthogonal.

(b) Consider the functions sin t and cos t in the vector space C[−π, π] of continuous functions on the closed interval [−π, π]. Then

Thus, sin t and cos t are orthogonal functions in the vector space C[−π, π].

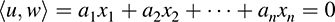

Remark: A vector w = (x1, x2, …, xn) is orthogonal to u = (a1, a2, …, an) in Rn if

That is, w is orthogonal to u if w satisfies a homogeneous equation whose coefficients are the elements of u.

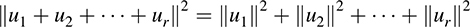

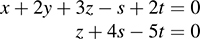

EXAMPLE 7.7 Find a nonzero vector w that is orthogonal to u1 = (1, 2, 1) and u2 = (2, 5, 4) in R3.

Let w = (x, y, z). Then we want  u1, w

u1, w = 0 and

= 0 and  u2, w

u2, w = 0. This yields the homogeneous system

= 0. This yields the homogeneous system

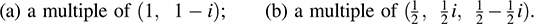

Here z is the only free variable in the echelon system. Set z = 1 to obtain y = −2 and x = 3. Thus, w = (3, −2, 1) is a desired nonzero vector orthogonal to u1 and u2.

Any multiple of w will also be orthogonal to u1 and u2. Normalizing w, we obtain the following unit vector orthogonal to u1 and u2:

Orthogonal Complements

Let S be a subset of an inner product space V. The orthogonal complement of S, denoted by S⊥ (read “S perp”) consists of those vectors in V that are orthogonal to every vector u ∈ S; that is,

In particular, for a given vector u in V, we have

that is, u⊥ consists of all vectors in V that are orthogonal to the given vector u.

We show that S⊥ is a subspace of V. Clearly 0 ∈ S⊥, because 0 is orthogonal to every vector in V. Now suppose υ, w ∈ S⊥. Then, for any scalars a and b and any vector u ∈ S, we have

Thus, aυ + bw ∈ S⊥, and therefore S⊥ is a subspace of V.

We state this result formally.

PROPOSITION 7.3: Let S be a subset of a vector space V. Then S⊥ is a subspace of V.

Remark 1: Suppose u is a nonzero vector in R3. Then there is a geometrical description of u⊥. Specifically, u⊥ is the plane in R3 through the origin O and perpendicular to the vector u. This is shown in Fig. 7-2.

Remark 2: Let W be the solution space of an m × n homogeneous system AX = 0, where A = [aij] and X = [xi]. Recall that W may be viewed as the kernel of the linear mapping A:Rn → Rm. Now we can give another interpretation of W using the notion of orthogonality. Specifically, each solution vector w = (x1, x2, …, xn) is orthogonal to each row of A; hence, W is the orthogonal complement of the row space of A.

EXAMPLE 7.8 Find a basis for the subspace u⊥ of R3, where u = (1, 3, −4).

Note that u⊥ consists of all vectors w = (x, y, z) such that  u, w

u, w = 0, or x + 3y − 4z = 0. The free variables are y and z.

= 0, or x + 3y − 4z = 0. The free variables are y and z.

(1) Set y = 1, z = 0 to obtain the solution w1 = (−3, 1, 0).

(2) Set y = 0, z = 1 to obtain the solution w2 = (4, 0, 1).

The vectors w1 and w2 form a basis for the solution space of the equation, and hence a basis for u⊥.

Suppose W is a subspace of V. Then both W and W⊥ are subspaces of V. The next theorem, whose proof (Problem 7.28) requires results of later sections, is a basic result in linear algebra.

THEOREM 7.4: Let W be a subspace of V. Then V is the direct sum of W and W⊥; that is, V = W ⊕ W⊥.

7.6 Orthogonal Sets and Bases

Consider a set S = {u1, u2, …, ur} of nonzero vectors in an inner product space V. S is called orthogonal if each pair of vectors in S are orthogonal, and S is called orthonormal if S is orthogonal and each vector in S has unit length. That is,

Normalizing an orthogonal set S refers to the process of multiplying each vector in S by the reciprocal of its length in order to transform S into an orthonormal set of vectors.

The following theorems apply.

THEOREM 7.5: Suppose S is an orthogonal set of nonzero vectors. Then S is linearly independent.

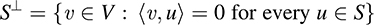

THEOREM 7.6: (Pythagoras) Suppose {u1, u2, …, ur} is an orthogonal set of vectors. Then

These theorems are proved in Problems 7.15 and 7.16, respectively. Here we prove the Pythagorean theorem in the special and familiar case for two vectors. Specifically, suppose  u, υ

u, υ = 0. Then

= 0. Then

which gives our result.

(a) Let E = {e1, e2, e3} = {(1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), (0, 0, 1)} be the usual basis of Euclidean space R3. It is clear that

Namely, E is an orthonormal basis of R3. More generally, the usual basis of Rn is orthonormal for every n.

(b) Let V = C[−π, π] be the vector space of continuous functions on the interval −π ≤ t ≤ π with inner product defined by  . Then the following is a classical example of an orthogonal set in V:

. Then the following is a classical example of an orthogonal set in V:

This orthogonal set plays a fundamental role in the theory of Fourier series.

Orthogonal Basis and Linear Combinations, Fourier Coefficients

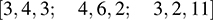

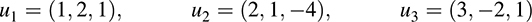

Let S consist of the following three vectors in R3:

The reader can verify that the vectors are orthogonal; hence, they are linearly independent. Thus, S is an orthogonal basis of R3.

Suppose we want to write υ = (7, 1, 9) as a linear combination of u1, u2, u3. First we set υ as a linear combination of u1, u2, u3 using unknowns x1, x2, x3 as follows:

We can proceed in two ways.

METHOD 1: Expand (*) (as in Chapter 3) to obtain the system

Solve the system by Gaussian elimination to obtain x1 = 3, x2 = −1, x3 = 2. Thus, υ = 3u1 − u2 + 2u3.

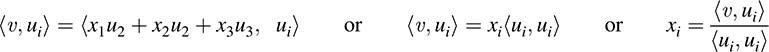

METHOD 2: (This method uses the fact that the basis vectors are orthogonal, and the arithmetic is much simpler.) If we take the inner product of each side of (*) with respect to ui, we get

Here two terms drop out, because u1, u2, u3 are orthogonal. Accordingly,

Thus, again, we get υ = 3u1 − u2 + 2u3.

The procedure in Method 2 is true in general. Namely, we have the following theorem (proved in Problem 7.17).

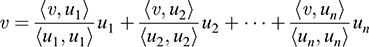

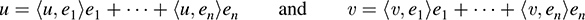

THEOREM 7.7: Let {u1, u2, …, un} be an orthogonal basis of V. Then, for any υ ∈ V,

Remark: The scalar  is called the Fourier coefficient of υ with respect to ui, because it is analogous to a coefficient in the Fourier series of a function. This scalar also has a geometric interpretation, which is discussed below.

is called the Fourier coefficient of υ with respect to ui, because it is analogous to a coefficient in the Fourier series of a function. This scalar also has a geometric interpretation, which is discussed below.

Projections

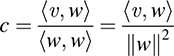

Let V be an inner product space. Suppose w is a given nonzero vector in V, and suppose υ is another vector. We seek the “projection of υ along w,” which, as indicated in Fig. 7-3(a), will be the multiple cw of w such that υ′ = υ − cw is orthogonal to w. This means

Accordingly, the projection of υ along w is denoted and defined by

Such a scalar c is unique, and it is called the Fourier coefficient of υ with respect to w or the component of v along w.

The above notion is generalized as follows (see Problem 7.25).

THEOREM 7.8: Suppose w1, w2, …, wr form an orthogonal set of nonzero vectors in V. Let υ be any vector in V. Define

where

Then υ′ is orthogonal to w1, w2, …, wr.

Note that each ci in the above theorem is the component (Fourier coefficient) of υ along the given wi.

Remark: The notion of the projection of a vector υ ∈ V along a subspace W of V is defined as follows. By Theorem 7.4, V = W ⊕ W⊥. Hence, υ may be expressed uniquely in the form

We define w to be the projection of υ along W, and denote it by proj(υ, W), as pictured in Fig. 7-3(b). In particular, if W = span(w1, w2, …, wr), where the wi form an orthogonal set, then

Here ci is the component of υ along wi, as above.

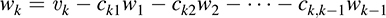

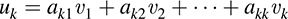

7.7 Gram–Schmidt Orthogonalization Process

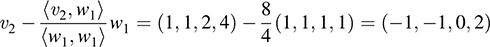

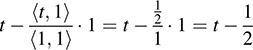

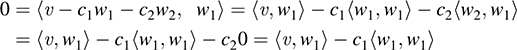

Suppose {υ1, υ2, …, υn} is a basis of an inner product space V. One can use this basis to construct an orthogonal basis {w1, w2, …, wn} of V as follows. Set

In other words, for k = 2, 3, …, n, we define

where cki =  υk, wi

υk, wi /

/ wi, wi

wi, wi is the component of υk along wi. By Theorem 7.8, each wk is orthogonal to the preceeding w’s. Thus, w1, w2, …, wn form an orthogonal basis for V as claimed. Normalizing each wi will then yield an orthonormal basis for V.

is the component of υk along wi. By Theorem 7.8, each wk is orthogonal to the preceeding w’s. Thus, w1, w2, …, wn form an orthogonal basis for V as claimed. Normalizing each wi will then yield an orthonormal basis for V.

The above construction is known as the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process. The following remarks are in order.

Remark 1: Each vector wk is a linear combination of υk and the preceding w’s. Hence, one can easily show, by induction, that each wk is a linear combination of υ1, υ2, …, υn.

Remark 2: Because taking multiples of vectors does not affect orthogonality, it may be simpler in hand calculations to clear fractions in any new wk, by multiplying wk by an appropriate scalar, before obtaining the next wk+1.

Remark 3: Suppose u1, u2, …, ur are linearly independent, and so they form a basis for U = span(ui). Applying the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to the u’s yields an orthogonal basis for U.

The following theorems (proved in Problems 7.26 and 7.27) use the above algorithm and remarks.

THEOREM 7.9: Let {υ1, υ2, …, υn} be any basis of an inner product space V. Then there exists an orthonormal basis {u1, u2, …, un} of V such that the change-of-basis matrix from {υi} to {ui} is triangular; that is, for k = 1, …, n,

THEOREM 7.10: Suppose S = {w1, w2, …, wr} is an orthogonal basis for a subspace W of a vector space V. Then one may extend S to an orthogonal basis for V; that is, one may find vectors wr+1, …, wn such that {w1, w2, …, wn} is an orthogonal basis for V.

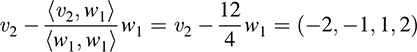

EXAMPLE 7.10 Apply the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to find an orthogonal basis and then an orthonormal basis for the subspace U of R4 spanned by

(1) First set w1 = υ1 = (1, 1, 1, 1).

(2) Compute

Set w2 = (−2, −1, 1, 2).

(3) Compute

Clear fractions to obtain w3 = (−6, −17, −13, 14).

Thus, w1, w2, w3 form an orthogonal basis for U. Normalize these vectors to obtain an orthonormal basis {u1, u2, u3} of U. We have ||w1||2 = 4, ||w2||2 = 10, ||w3||2 = 910, so

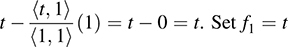

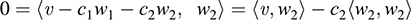

EXAMPLE 7.11 Let V be the vector space of polynomials f(t) with inner product  dt. Apply the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to {1, t, t2, t3} to find an orthogonal basis {f0, f1, f2, f3} with integer coefficients for P3(t).

dt. Apply the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to {1, t, t2, t3} to find an orthogonal basis {f0, f1, f2, f3} with integer coefficients for P3(t).

Here we use the fact that, for r + s = n,

(1) First set f0 = 1.

(2) Compute  .

.

(3) Compute

Multiply by 3 to obtain f2 = 3t2 = 1.

Multiply by 5 to obtain f3 = 5t3 − 3t.

Thus, {1, t, 3t2 − 1, 5t3 − 3t} is the required orthogonal basis.

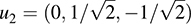

Remark: Normalizing the polynomials in Example 7.11 so that p(1) = 1 yields the polynomials

These are the first four Legendre polynomials, which appear in the study of differential equations.

7.8 Orthogonal and Positive Definite Matrices

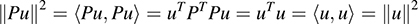

This section discusses two types of matrices that are closely related to real inner product spaces V. Here vectors in Rn will be represented by column vectors. Thus,  u, υ

u, υ = uTυ denotes the inner product in Euclidean space Rn.

= uTυ denotes the inner product in Euclidean space Rn.

Orthogonal Matrices

A real matrix P is orthogonal if P is nonsingular and P−1 = PT, or, in other words, if PPT = PTP = I. First we recall (Theorem 2.6) an important characterization of such matrices.

THEOREM 7.11: Let P be a real matrix. Then the following are equivalent: (a) P is orthogonal; (b) the rows of P form an orthonormal set; (c) the columns of P form an orthonormal set.

(This theorem is true only using the usual inner product on Rn. It is not true if Rn is given any other inner product.)

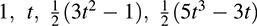

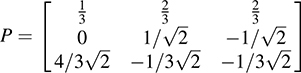

(a) Let  . The rows of P are orthogonal to each other and are unit vectors. Thus P is an orthogonal matrix.

. The rows of P are orthogonal to each other and are unit vectors. Thus P is an orthogonal matrix.

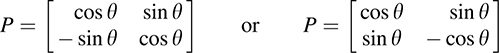

(b) Let P be a 2 × 2 orthogonal matrix. Then, for some real number θ, we have

The following two theorems (proved in Problems 7.37 and 7.38) show important relationships between orthogonal matrices and orthonormal bases of a real inner product space V.

THEOREM 7.12: Suppose E = {ei} and  are orthonormal bases of V. Let P be the change-of-basis matrix from the basis E to the basis E′. Then P is orthogonal.

are orthonormal bases of V. Let P be the change-of-basis matrix from the basis E to the basis E′. Then P is orthogonal.

THEOREM 7.13: Let {e1, …, en} be an orthonormal basis of an inner product space V. Let P = [aij] be an orthogonal matrix. Then the following n vectors form an orthonormal basis for V:

Positive Definite Matrices

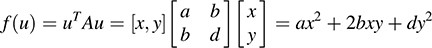

Let A be a real symmetric matrix; that is, AT = A. Then A is said to be positive definite if, for every nonzero vector u in Rn,

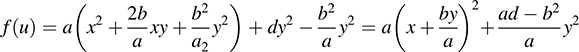

Algorithms to decide whether or not a matrix A is positive definite will be given in Chapter 13. However, for 2 × 2 matrices, we have simple criteria that we state formally in the following theorem (proved in Problem 7.43).

THEOREM 7.14: A 2 × 2 real symmetric matrix  is positive definite if and only if the diagonal entries a and d are positive and the determinant |A| = ad − bc = ad − b2 is positive.

is positive definite if and only if the diagonal entries a and d are positive and the determinant |A| = ad − bc = ad − b2 is positive.

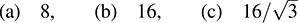

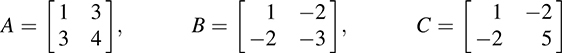

EXAMPLE 7.13 Consider the following symmetric matrices:

A is not positive definite, because |A| = 4 − 9 = −5 is negative. B is not positive definite, because the diagonal entry −3 is negative. However, C is positive definite, because the diagonal entries 1 and 5 are positive, and the determinant |C| = 5 − 4 = 1 is also positive.

The following theorem (proved in Problem 7.44) holds.

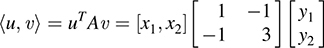

THEOREM 7.15: Let A be a real positive definite matrix. Then the function  u, υ

u, υ = uTAυ is an inner product on Rn.

= uTAυ is an inner product on Rn.

Matrix Representation of an Inner Product (Optional)

Theorem 7.15 says that every positive definite matrix A determines an inner product on Rn. This subsection may be viewed as giving the converse of this result.

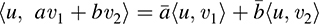

Let V be a real inner product space with basis S = {u1, u2, …, un}. The matrix

is called the matrix representation of the inner product on V relative to the basis S.

Observe that A is symmetric, because the inner product is symmetric; that is,  ui, uj

ui, uj =

=  uj, ui

uj, ui . Also, A depends on both the inner product on V and the basis S for V. Moreover, if S is an orthogonal basis, then A is diagonal, and if S is an orthonormal basis, then A is the identity matrix.

. Also, A depends on both the inner product on V and the basis S for V. Moreover, if S is an orthogonal basis, then A is diagonal, and if S is an orthonormal basis, then A is the identity matrix.

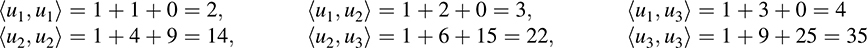

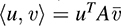

EXAMPLE 7.14 The vectors u1 = (1, 1, 0), u2 = (1, 2, 3), u3 = (1, 3, 5) form a basis S for Euclidean space R3. Find the matrix A that represents the inner product in R3 relative to this basis S.

First compute each  ui, uj

ui, uj to obtain

to obtain

Then  . As expected, A is symmetric.

. As expected, A is symmetric.

The following theorems (proved in Problems 7.45 and 7.46, respectively) hold.

THEOREM 7.16: Let A be the matrix representation of an inner product relative to basis S for V. Then, for any vectors u, υ ∈ V, we have

where [u] and [υ] denote the (column) coordinate vectors relative to the basis S.

THEOREM 7.17: Let A be the matrix representation of any inner product on V. Then A is a positive definite matrix.

7.9 Complex Inner Product Spaces

This section considers vector spaces over the complex field C. First we recall some properties of the complex numbers (Section 1.7), especially the relations between a complex number z = a + bi, where a, b ∈ R, and its complex conjugate  :

:

Also, z is real if and only if  .

.

The following definition applies.

DEFINITION: Let V be a vector space over C. Suppose to each pair of vectors, u, υ ∈ V there is assigned a complex number, denoted by  u, υ

u, υ . This function is called a (complex) inner product on V if it satisfies the following axioms:

. This function is called a (complex) inner product on V if it satisfies the following axioms:

The vector space V over C with an inner product is called a (complex) inner product space. Observe that a complex inner product differs from the real case only in the second axiom  . Axiom

. Axiom  (Linear Property) is equivalent to the two conditions:

(Linear Property) is equivalent to the two conditions:

On the other hand, applying  and

and  , we obtain

, we obtain

That is, we must take the conjugate of a complex number when it is taken out of the second position of a complex inner product. In fact (Problem 7.47), the inner product is conjugate linear in the second position; that is,

Combining linear in the first position and conjugate linear in the second position, we obtain, by induction,

The following remarks are in order.

Remark 1: Axiom  by itself implies that

by itself implies that  0, 0

0, 0 =

=  0υ, 0

0υ, 0 = 0

= 0 υ, 0

υ, 0 = 0. Accordingly,

= 0. Accordingly,  ,

,  , and

, and  are equivalent to

are equivalent to  ,

,  , and the following axiom:

, and the following axiom:

That is, a function satisfying  ,

,  , and

, and  is a (complex) inner product on V.

is a (complex) inner product on V.

Remark 2: By  ,

,  . Thus,

. Thus,  u, u

u, u must be real. By

must be real. By  ,

,  u, u

u, u must be nonnegative, and hence, its positive real square root exists. As with real inner product spaces, we define

must be nonnegative, and hence, its positive real square root exists. As with real inner product spaces, we define  to be the norm or length of u.

to be the norm or length of u.

Remark 3: In addition to the norm, we define the notions of orthogonality, orthogonal complement, and orthogonal and orthonormal sets as before. In fact, the definitions of distance and Fourier coefficient and projections are the same as in the real case.

EXAMPLE 7.15 (Complex Euclidean Space Cn). Let V = Cn, and let u = (zi) and υ = (wi) be vectors in Cn. Then

is an inner product on V, called the usual or standard inner product on Cn. V with this inner product is called Complex Euclidean Space. We assume this inner product on Cn unless otherwise stated or implied. Assuming u and υ are column vectors, the above inner product may be defined by

where, as with matrices,  means the conjugate of each element of υ. If u and υ are real, we have

means the conjugate of each element of υ. If u and υ are real, we have  . In this case, the inner product reduced to the analogous one on Rn.

. In this case, the inner product reduced to the analogous one on Rn.

(a) Let V be the vector space of complex continuous functions on the (real) interval a ≤ t ≤ b. Then the following is the usual inner product on V:

(b) Let U be the vector space of m × n matrices over C. Suppose A = (zij) and B = (wij) are elements of U. Then the following is the usual inner product on U:

As usual,  ; that is, BH is the conjugate transpose of B.

; that is, BH is the conjugate transpose of B.

The following is a list of theorems for complex inner product spaces that are analogous to those for the real case. Here a Hermitian matrix A (i.e., one where  ) plays the same role that a symmetric matrix A (i.e., one where AT = A) plays in the real case. (Theorem 7.18 is proved in Problem 7.50.)

) plays the same role that a symmetric matrix A (i.e., one where AT = A) plays in the real case. (Theorem 7.18 is proved in Problem 7.50.)

THEOREM 7.18: (Cauchy–Schwarz) Let V be a complex inner product space. Then

THEOREM 7.19: Let W be a subspace of a complex inner product space V. Then V = W ⊕ W⊥.

THEOREM 7.20: Suppose {u1, u2, …, un} is a basis for a complex inner product space V. Then, for any υ ∈ V,

THEOREM 7.21: Suppose {u1, u2, …, un} is a basis for a complex inner product space V. Let A = [aij] be the complex matrix defined by aij =  ui, uj

ui, uj . Then, for any u, υ ∈ V,

. Then, for any u, υ ∈ V,

where [u] and [υ] are the coordinate column vectors in the given basis {ui}. (Remark: This matrix A is said to represent the inner product on V.)

THEOREM 7.22: Let A be a Hermitian matrix (i.e.,  ) such that

) such that  is real and positive for every nonzero vector X ∈ Cn. Then

is real and positive for every nonzero vector X ∈ Cn. Then  is an inner product on Cn.

is an inner product on Cn.

THEOREM 7.23: Let A be the matrix that represents an inner product on V. Then A is Hermitian, and XTAX is real and positive for any nonzero vector in Cn.

7.10 Normed Vector Spaces (Optional)

We begin with a definition.

DEFINITION: Let V be a real or complex vector space. Suppose to each υ ∈ V there is assigned a real number, denoted by ||υ||. This function ||·|| is called a norm on V if it satisfies the following axioms:

[N1] ||υ|| 0; and ||υ|| = 0 if and only if υ = 0.

[N2] ||kυ|| = |k|||υ||.

[N3] ||u + υ|| ≤ ||u||+||υ||.

A vector space V with a norm is called a normed vector space.

Suppose V is a normed vector space. The distance between two vectors u and υ in V is denoted and defined by

The following theorem (proved in Problem 7.56) is the main reason why d (u, υ) is called the distance between u and υ.

THEOREM 7.24: Let V be a normed vector space. Then the function d(u, υ) = ||u − υ|| satisfies the following three axioms of a metric space:

[M1] d(u, υ) ≥ 0; and d (u, v) = 0 if and only if u = υ.

[M2] d(u, υ) = d(υ, u).

[M3] d(u, υ) ≤ d (u, w)+ d (w, υ).

Normed Vector Spaces and Inner Product Spaces

Suppose V is an inner product space. Recall that the norm of a vector υ in V is defined by

One can prove (Theorem 7.2) that this norm satisfies [N1], [N2], and [N3]. Thus, every inner product space V is a normed vector space. On the other hand, there may be norms on a vector space V that do not come from an inner product on V, as shown below.

Norms on Rn and Cn

The following define three important norms on Rn and Cn:

(Note that subscripts are used to distinguish between the three norms.) The norms ||·||∞, ||·||1, and ||·||2 are called the infinity-norm, one-norm, and two-norm, respectively. Observe that ||·||2 is the norm on Rn (respectively, Cn) induced by the usual inner product on Rn (respectively, Cn). We will let d∞, d1, d2 denote the corresponding distance functions.

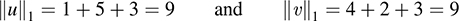

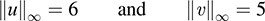

EXAMPLE 7.17 Consider vectors u = (1, −5, 3) and υ = (4, 2, −3) in R3.

(a) The infinity norm chooses the maximum of the absolute values of the components. Hence,

(b) The one-norm adds the absolute values of the components. Thus,

(c) The two-norm is equal to the square root of the sum of the squares of the components (i.e., the norm induced by the usual inner product on R3). Thus,

(d) Because u − υ = (1 −4, −5 −2, 3 + 3) = (−3, −7, 6), we have

EXAMPLE 7.18 Consider the Cartesian plane R2 shown in Fig. 7-4.

(a) Let D1 be the set of points u = (x, y) in R2 such that ||u||2 = 1. Then D1 consists of the points (x, y) such that  . Thus, D1 is the unit circle, as shown in Fig. 7-4.

. Thus, D1 is the unit circle, as shown in Fig. 7-4.

(b) Let D2 be the set of points u = (x, y) in R2 such that ||u||1 = 1. Then D1 consists of the points (x, y) such that ||u||1 = |x|+|y| = 1. Thus, D2 is the diamond inside the unit circle, as shown in Fig. 7-4.

(c) Let D3 be the set of points u = (x, y) in R2 such that ||u||∞ = 1. Then D3 consists of the points (x, y) such that ||u||∞ = max(|x|, |y|) = 1. Thus, D3 is the square circumscribing the unit circle, as shown in Fig. 7-4.

Norms on C[a, b]

Consider the vector space V = C[a, b] of real continuous functions on the interval a ≤ t ≤ b. Recall that the following defines an inner product on V:

Accordingly, the above inner product defines the following norm on V = C[a, b] (which is analogous to the ||·||2 norm on Rn):

The following define the other norms on V = C[a, b]:

There are geometrical descriptions of these two norms and their corresponding distance functions, which are described below.

The first norm is pictured in Fig. 7-5. Here

This norm is analogous to the norm ||·||1 on Rn.

The second norm is pictured in Fig. 7-6. Here

This norm is analogous to the norms ||·||∞ on Rn.

SOLVED PROBLEMS

Inner Products

(a)  5u1 + 8u2, 6υ1 − 7υ2

5u1 + 8u2, 6υ1 − 7υ2 ,

,

(b)  3u + 5υ, 4u 6υ

3u + 5υ, 4u 6υ ,

,

(c) ||2u − 3υ||2

Use linearity in both positions and, when possible, symmetry,  u, υ

u, υ =

=  υ, u

υ, u .

.

(a) Take the inner product of each term on the left with each term on the right:

[Remark: Observe the similarity between the above expansion and the expansion (5a–8b)(6c–7d) in ordinary algebra.]

7.2. Consider vectors u = (1, 2, 4), υ = (2, 3, 5), w = (4, 2, 3) in R3. Find

(a) Multiply corresponding components and add to get u · υ = 2 − 6 + 20 = 16.

(b) u · w = 4 + 4 − 12 = −4.

(c) υ · w = 8 − 6 − 15 = −13.

(d) First find u + υ = (3, −1, 9). Then (u + υ) · w = 12 − 2 − 27 = −17. Alternatively, using [I1], (u + υ) · w = u · w + υ w = −4 − 13 = −17.

(e) First find ||u||2 by squaring the components of u and adding:

(f) ||υ||2 = 4 + 9 + 25 = 38, and so  .

.

7.3. Verify that the following defines an inner product in R2:

We argue via matrices. We can write  u, υ

u, υ in matrix notation as follows:

in matrix notation as follows:

Because A is real and symmetric, we need only show that A is positive definite. The diagonal elements 1 and 3 are positive, and the determinant ||A|| = 3 − 1 = 2 is positive. Thus, by Theorem 7.14, A is positive definite. Accordingly, by Theorem 7.15,  u, υ

u, υ is an inner product.

is an inner product.

7.4. Consider the vectors u = (1, 5) and υ = (3, 4) in R2. Find

(a)  u, υ

u, υ with respect to the usual inner product in R2.

with respect to the usual inner product in R2.

(b)  u, υ

u, υ with respect to the inner product in R2 in Problem 7.3.

with respect to the inner product in R2 in Problem 7.3.

(c) ||υ|| using the usual inner product in R2.

(d) ||υ|| using the inner product in R2 in Problem 7.3.

(a)  u, υ

u, υ = 3 + 20 = 23.

= 3 + 20 = 23.

(b)  u, υ

u, υ = 1 · 3 − 1 · 4 − 5 · 3 + 3 · 5 · 4 = 3 − 4 − 15 + 60 = 44.

= 1 · 3 − 1 · 4 − 5 · 3 + 3 · 5 · 4 = 3 − 4 − 15 + 60 = 44.

(c) ||υ||2 =  υ, υ

υ, υ =

=  (3, 4), (3, 4)

(3, 4), (3, 4) = 9 + 16 = 25; hence, |υ|| = 5.

= 9 + 16 = 25; hence, |υ|| = 5.

(d) ||υ||2 =  υ, υ

υ, υ =

=  (3, 4), (3, 4)

(3, 4), (3, 4) = 9 − 12 − 12 + 48 = 33; hence,

= 9 − 12 − 12 + 48 = 33; hence,  .

.

7.5. Consider the following polynomials in P(t) with the inner product  :

:

(a) Find  f, g

f, g and

and  f, h

f, h .

.

(b) Find ||f|| and ||g||.

(c) Normalize f and g.

(b)

(c) Because  and g is already a unit vector, we have

and g is already a unit vector, we have

7.6. Find cos θ where θ is the angle between:

(a) u = (1, 3, −5, 4) and υ = (2, −3, 4, 1) in R4,

(a) Compute:

Thus,

(b) Use  , the sum of the products of corresponding entries.

, the sum of the products of corresponding entries.

Use  , the sum of the squares of all the elements of A.

, the sum of the squares of all the elements of A.

Thus,

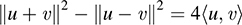

7.7. Verify each of the following:

(a) Parallelogram Law (Fig. 7-7): ||u + υ||2 + ||u − υ||2 = 2||u||2 + 2||υ||2.

(b) Polar form for  u, υ

u, υ (which shows the inner product can be obtained from the norm function):

(which shows the inner product can be obtained from the norm function):

Expand as follows to obtain

Add (1) and (2) to get the Parallelogram Law (a). Subtract (2) from (1) to obtain

Divide by 4 to obtain the (real) polar form (b).

7.8. Prove Theorem 7.1 (Cauchy–Schwarz): For u and υ in a real inner product space V,  u, u

u, u 2 ≤

2 ≤  u, u

u, u υ, υ

υ, υ or |

or | u, υ

u, υ | ≤ ||u|| ||υ||.

| ≤ ||u|| ||υ||.

For any real number t,

Let a = ||u||2, b = 2 u, υ), c = ||υ||2. Because ||tu + υ||2 ≥ 0, we have

u, υ), c = ||υ||2. Because ||tu + υ||2 ≥ 0, we have

for every value of t. This means that the quadratic polynomial cannot have two real roots, which implies that b2 − 4ac ≤ 0 or b2 ≤ 4ac. Thus,

Dividing by 4 gives our result.

7.9. Prove Theorem 7.2: The norm in an inner product space V satisfies

(a) [N1] ||υ|| 0; and ||υ|| = 0 if and only if υ = 0.

(b) [N2] ||kυ|| = |k|||υ||.

(c) [N3] ||u + υ|| ≤ ||u|| + ||υ||.

(a) If υ ≠ 0, then  υ, υ

υ, υ > 0, and hence,

> 0, and hence,  . If υ = 0, then

. If υ = 0, then  0, 0

0, 0 = 0. Consequently,

= 0. Consequently,  . Thus, [N1] is true.

. Thus, [N1] is true.

(b) We have ||kυ||2 =  kυ, k υ

kυ, k υ = k2

= k2 υ, υ

υ, υ = k2||υ||2. Taking the square root of both sides gives [N2].

= k2||υ||2. Taking the square root of both sides gives [N2].

(c) Using the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, we obtain

Taking the square root of both sides yields [N3].

Orthogonality, Orthonormal Complements, Orthogonal Sets

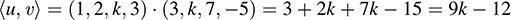

7.10. Find k so that u = (1, 2, k, 3) and υ = (3, k, 7, −5) in R4 are orthogonal.

First find

Then set  u, υ

u, υ = 9k − 12 = 0 to obtain

= 9k − 12 = 0 to obtain  .

.

7.11. Let W be the subspace of R5 spanned by u = (1, 2, 3, −1, 2) and υ = (2, 4, 7, 2, −1). Find a basis of the orthogonal complement W⊥ of W.

We seek all vectors w = (x, y, z, s, t) such that

Eliminating x from the second equation, we find the equivalent system

The free variables are y, s, and t. Therefore,

(1) Set y = −1, s = 0, t = 0 to obtain the solution w1 = (2, −1, 0, 0, 0).

(2) Set y = 0, s = 1, t = 0 to find the solution w2 = (13, 0, −4, 1, 0).

(3) Set y = 0, s = 0, t = 1 to obtain the solution w3 = (−17, 0, 5, 0, 1).

The set {w1, w2, w3} is a basis of W⊥.

7.12. Let w = (1, 2, 3, 1) be a vector in R4. Find an orthogonal basis for w⊥.

Find a nonzero solution of x + 2y + 3z + t = 0, say υ1 = (0, 0, 1, −3). Now find a nonzero solution of the system

say υ2 = (0, −5, 3, 1). Last, find a nonzero solution of the system

say υ3 = (−14, 2, 3, 1). Thus, υ1, υ2, υ3 form an orthogonal basis for w⊥.

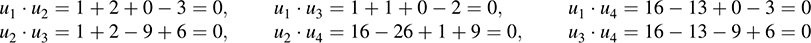

7.13. Let S consist of the following vectors in R4:

(a) Show that S is orthogonal and a basis of R4.

(b) Find the coordinates of an arbitrary vector υ = (a, b, c, d) in R4 relative to the basis S.

(a) Compute

Thus, S is orthogonal, and S is linearly independent. Accordingly, S is a basis for R4 because any four linearly independent vectors form a basis of R4.

(b) Because S is orthogonal, we need only find the Fourier coefficients of υ with respect to the basis vectors, as in Theorem 7.7. Thus,

are the coordinates of υ with respect to the basis S.

7.14. Suppose S, S1, S2 are the subsets of V. Prove the following (where S⊥⊥ means (S⊥)⊥):

(a) S ⊆ S⊥⊥.

(b) If S1 ⊆ S2, then  .

.

(c) S⊥ = span (S)⊥.

(a) Let w ∈ S. Then  w, υ

w, υ = 0 for every υ ∈ S⊥; hence, w ∈ S⊥⊥. Accordingly, S ⊆ S⊥⊥.

= 0 for every υ ∈ S⊥; hence, w ∈ S⊥⊥. Accordingly, S ⊆ S⊥⊥.

(b) Let  . Then

. Then  w, υ

w, υ = 0 for every υ ∈ 2 S2. Because S1 ⊆ S2,

= 0 for every υ ∈ 2 S2. Because S1 ⊆ S2,  w, υ

w, υ = 0 for every υ = S1. Thus,

= 0 for every υ = S1. Thus,  , and hence,

, and hence,  .

.

(c) Because S ⊆ span(S), part (b) gives us span(S)⊥ ⊆ S⊥. Suppose u ∈ S⊥ and υ ∈ span(S). Then there exist w1, w2, …, wk in S such that υ = a1w1 + a2w2 + … + akwk. Then, using u ∈ S⊥, we have

Thus, u ∈ span(S)⊥. Accordingly, S⊥ ⊆ span(S)⊥. Both inclusions give S⊥ = span(S)⊥.

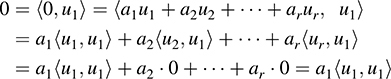

7.15. Prove Theorem 7.5: Suppose S is an orthogonal set of nonzero vectors. Then S is linearly independent.

Suppose S = {u1, u2, …, ur} and suppose

Taking the inner product of (1) with u1, we get

Because u1 ≠ = 0, we have  u1, u1

u1, u1 ≠ 0. Thus, a1 = 0. Similarly, for i = 2, …, r, taking the inner product of (1) with ui,

≠ 0. Thus, a1 = 0. Similarly, for i = 2, …, r, taking the inner product of (1) with ui,

But  ui, ui

ui, ui ≠ 0, and hence, every ai = 0. Thus, S is linearly independent.

≠ 0, and hence, every ai = 0. Thus, S is linearly independent.

7.16. Prove Theorem 7.6 (Pythagoras): Suppose {u1, u2, …, ur} is an orthogonal set of vectors. Then

Expanding the inner product, we have

The theorem follows from the fact that  ui, ui

ui, ui = ||ui||2 and

= ||ui||2 and  ui, uj

ui, uj = 0 for i ≠ j.

= 0 for i ≠ j.

7.17. Prove Theorem 7.7: Let {u1, u2, …, un} be an orthogonal basis of V. Then for any υ ∈ V,

Suppose υ = k1u1 + k2u2 +…+ knun. Taking the inner product of both sides with u1 yields

Thus,  . Similarly, for i = 2, …, n,

. Similarly, for i = 2, …, n,

Thus,  . Substituting for ki in the equation υ = k1u1 +…+ knun, we obtain the desired result.

. Substituting for ki in the equation υ = k1u1 +…+ knun, we obtain the desired result.

7.18. Suppose E = {e1, e2, …, en} is an orthonormal basis of V. Prove

(a) For any u ∈ V, we have u =  u, e1

u, e1 e1 +

e1 +  u, e2

u, e2 e2 +…+

e2 +…+ u, en

u, en en.

en.

(b)  a1e1 +…+ anen, b1e1 +…+ bnen

a1e1 +…+ anen, b1e1 +…+ bnen = a1b1 + a2b2 +…+ anbn.

= a1b1 + a2b2 +…+ anbn.

(c) For any u, υ ∈ V, we have  u, υ

u, υ =

=  u, e1

u, e1

υ, e1

υ, e1 +…+

+…+ u, en

u, en

υ, en

υ, en .

.

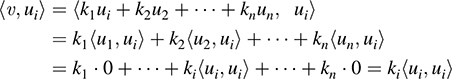

(a) Suppose u = k1e1 + k2e2 +…+ knen. Taking the inner product of u with e1,

Substituting  u, ei

u, ei for ki in the equation u = k1e1 +…+ knen, we obtain the desired result.

for ki in the equation u = k1e1 +…+ knen, we obtain the desired result.

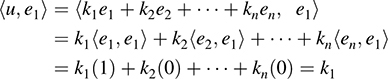

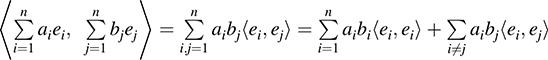

(b) We have

But  ei, ej

ei, ej = 0 for i ≠ j, and

= 0 for i ≠ j, and  ei, ej

ei, ej = 1 for i = j. Hence, as required,

= 1 for i = j. Hence, as required,

(c) By part (a), we have

Thus, by part (b),

Projections, Gram–Schmidt Algorithm, Applications

7.19. Suppose w ≠ 0. Let υ be any vector in V. Show that

is the unique scalar such that υ′ = υ − cw is orthogonal to w.

In order for υ′ to be orthogonal to w we must have

Thus,  . Conversely, suppose

. Conversely, suppose  . Then

. Then

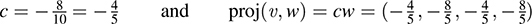

7.20. Find the Fourier coefficient c and the projection of υ = (1, −2, 3, −4) along w = (1, 2, 1, 2) in R4.

Compute  υ, w

υ, w = 1 − 4 + 3 − 8 = −8 and ||w||2 = 1 + 4 + 1 + 4 = 10. Then

= 1 − 4 + 3 − 8 = −8 and ||w||2 = 1 + 4 + 1 + 4 = 10. Then

7.21. Consider the subspace U of R4 spanned by the vectors:

Find (a) an orthogonal basis of U; (b) an orthonormal basis of U.

(a) Use the Gram–Schmidt algorithm. Begin by setting w1 = u = (1, 1, 1, 1). Next find

Set w2 = (−1, −1, 0, 2). Then find

Clear fractions to obtain w3 = (1, 3, −6, 2). Then w1, w2, w3 form an orthogonal basis of U.

(b) Normalize the orthogonal basis consisting of w1, w2, w3. Because ||w1||2 = 4, ||w2||2 = 6, and ||w3||2 = 50, the following vectors form an orthonormal basis of U:

7.22. Consider the vector space P(t) with inner product  . Apply the Gram–Schmidt algorithm to the set {1, t, t2} to obtain an orthogonal set {f0, f1, f2} with integer coefficients.

. Apply the Gram–Schmidt algorithm to the set {1, t, t2} to obtain an orthogonal set {f0, f1, f2} with integer coefficients.

First set f0 = 1. Then find

Clear fractions to obtain f1 = 2t − 1. Then find

Clear fractions to obtain f2 = 6t2 − 6t + 1. Thus, {1, 2t − 1, 6t2 − 6t + 1} is the required orthogonal set.

7.23. Suppose υ = (1, 3, 5, 7). Find the projection of υ onto W or, in other words, find w ∈ W that minimizes ||υ − w||, where W is the subspace of R4 spanned by

(a) u1 = (1, 1, 1, 1) and u2 = (1, −3, 4, −2),

(b) υ1 = (1, 1, 1, 1) and υ2 = (1, 2, 3, 2).

(a) Because u1 and u2 are orthogonal, we need only compute the Fourier coefficients:

Then  .

.

(b) Because υ1 and υ2 are not orthogonal, first apply the Gram–Schmidt algorithm to find an orthogonal basis for W. Set w1 = υ1 = (1, 1, 1, 1). Then find

Set w2 = (−1, 0, 1, 0). Now compute

Then w = proj(υ, W) = c1w1 + c2w2 = 4(1, 1, 1, 1) + 2(−1, 0, 1, 0) = (2, 4, 6, 4).

7.24. Suppose w1 and w2 are nonzero orthogonal vectors. Let υ be any vector in V. Find c1 and c2 so that υ′ is orthogonal to w1 and w2, where υ′ = υ − c1w1 − c2w2.

If υ′ is orthogonal to w1, then

Thus, c1 =  υ, w1

υ, w1 /

/ w1, w1

w1, w1 . (That is, c1 is the component of υ along w1.) Similarly, if υ′ is orthogonal to w2, then

. (That is, c1 is the component of υ along w1.) Similarly, if υ′ is orthogonal to w2, then

Thus, c2 =  υ, w2

υ, w2 /

/ w2, w2

w2, w2 . (That is, c2 is the component of υ along w2.)

. (That is, c2 is the component of υ along w2.)

7.25. Prove Theorem 7.8: Suppose w1, w2, …, wr form an orthogonal set of nonzero vectors in V. Let υ ∈ V. Define

Then υ′ is orthogonal to w1, w2, …, wr.

For i = 1, 2, …, r and using  wi, wj

wi, wj = 0 for i ≠ j, we have

= 0 for i ≠ j, we have

The theorem is proved.

7.26. Prove Theorem 7.9: Let {υ1, υ2, …, υn} be any basis of an inner product space V. Then there exists an orthonormal basis {u1, u2, …, un} of V such that the change-of-basis matrix from {υi} to {ui} is triangular; that is, for k = 1, 2, …, n,

The proof uses the Gram–Schmidt algorithm and Remarks 1 and 3 of Section 7.7. That is, apply the algorithm to {υi} to obtain an orthogonal basis {wi, …, wn}, and then normalize {wi} to obtain an orthonormal basis {ui} of V. The specific algorithm guarantees that each wk is a linear combination of υ1, …, υk, and hence, each uk is a linear combination of υ1, …, υk.

7.27. Prove Theorem 7.10: Suppose S = {w1, w2, …, wr}, is an orthogonal basis for a subspace W of V. Then one may extend S to an orthogonal basis for V; that is, one may find vectors wr+1, …, wn such that {w1, w2, …, wn} is an orthogonal basis for V.

Extend S to a basis S′ = {w1, …, wr, υr+1, …, υn} for V. Applying the Gram–Schmidt algorithm to S′, we first obtain w1, w2, …, wr because S is orthogonal, and then we obtain vectors wr+1, …, wn, where {w1, w2, …, wn} is an orthogonal basis for V. Thus, the theorem is proved.

7.28. Prove Theorem 7.4: Let W be a subspace of V. Then V = W ⊕ W⊥.

By Theorem 7.9, there exists an orthogonal basis {u1, …, ur} of W, and by Theorem 7.10 we can extend it to an orthogonal basis {u1, u2, …, un} of V. Hence, ur+1, …, un ∈ W⊥. If υ ∈ V, then

Accordingly, V = W + W⊥.

On the other hand, if w ∈ W ∩ W⊥, then  w, w

w, w = 0. This yields w = 0. Hence, W ∩ W⊥ = {0}.

= 0. This yields w = 0. Hence, W ∩ W⊥ = {0}.

The two conditions V = W + W⊥ and W ∩ W⊥ = {0} give the desired result V = W ⊕ W⊥.

Remark: Note that we have proved the theorem for the case that V has finite dimension. We remark that the theorem also holds for spaces of arbitrary dimension.

7.29. Suppose W is a subspace of a finite-dimensional space V. Prove that W = W⊥⊥.

By Theorem 7.4, V = W ⊕ W⊥, and also V = W⊥ ⊕ W⊥⊥. Hence,

This yields dim W = dim W⊥⊥. But W ⊆ W⊥⊥ (see Problem 7.14). Hence, W = W⊥⊥, as required.

7.30. Prove the following: Suppose w1, w2, …, wr form an orthogonal set of nonzero vectors in V. Let υ be any vector in V and let ci be the component of υ along wi. Then, for any scalars a1, …, ar, we have

That is, Σ ciwi is the closest approximation to υ as a linear combination of w1, …, wr.

By Theorem 7.8, υ − Σ ckwk is orthogonal to every wi and hence orthogonal to any linear combination of w1, w2, …, wr. Therefore, using the Pythagorean theorem and summing from k = 1 to r,

The square root of both sides gives our theorem.

7.31. Suppose {e1, e2, …, er} is an orthonormal set of vectors in V. Let υ be any vector in V and let ci be the Fourier coefficient of υ with respect to ei. Prove Bessel’s inequality:

Note that ci =  υ, ei

υ, ei , because ||ei|| = 1. Then, using

, because ||ei|| = 1. Then, using  ei, ej

ei, ej = 0 for i ≠ j and summing from k = 1 to r, we get

= 0 for i ≠ j and summing from k = 1 to r, we get

This gives us our inequality.

Orthogonal Matrices

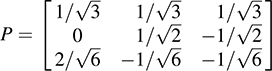

7.32. Find an orthogonal matrix P whose first row is  .

.

First find a nonzero vector w2 = (x, y, z) that is orthogonal to u1—that is, for which

One such solution is w2 = (0, 1, −1). Normalize w2 to obtain the second row of P:

Next find a nonzero vector w3 = (x, y, z) that is orthogonal to both u1 and u2—that is, for which

Set z = −1 and find the solution w3 = (4, −1, −1). Normalize w3 and obtain the third row of P; that is,

Thus,

We emphasize that the above matrix P is not unique.

7.33. Let  . Determine whether or not: (a) the rows of A are orthogonal;

. Determine whether or not: (a) the rows of A are orthogonal;

(b) A is an orthogonal matrix; (c) the columns of A are orthogonal.

(a) Yes, because (1, 1, −1) · (1, 3, 4) = 1 + 3 − 4 = 0, (1, 1 − 1) · (7, −5, 2) = 7 − 5 − 2 = 0, and (1, 3, 4) · (7, − 5, 2) = 7 − 15 + 8 = 0.

(b) No, because the rows of A are not unit vectors, for example, (1, 1, −1)2 = 1 + 1 + 1 = 3.

(c) No; for example, (1, 1, 7) · (1, 3, −5) = 1 + 3 − 35 = −31 ≠ 0.

7.34. Let B be the matrix obtained by normalizing each row of A in Problem 7.33.

(a) Find B.

(b) Is B an orthogonal matrix?

(c) Are the columns of B orthogonal?

Thus,

(b) Yes, because the rows of B are still orthogonal and are now unit vectors.

(c) Yes, because the rows of B form an orthonormal set of vectors. Then, by Theorem 7.11, the columns of B must automatically form an orthonormal set.

7.35. Prove each of the following:

(a) P is orthogonal if and only if PT is orthogonal.

(b) If P is orthogonal, then P−1 is orthogonal.

(c) If P and Q are orthogonal, then PQ is orthogonal.

(a) We have (PT)T = P. Thus, P is orthogonal if and only if PPT = I if and only if PTT PT = I if and only if PT is orthogonal.

(b) We have PT = P−1, because P is orthogonal. Thus, by part (a), P−1 is orthogonal.

(c) We have PT = P−1 and QT = Q−1. Thus, (PQ)(PQ)T = PQQTPT = PQQ−1P−1 = I. Therefore, (PQ)T = (PQ)−1, and so PQ is orthogonal.

7.36. Suppose P is an orthogonal matrix. Show that

(a)  Pu, Pυ

Pu, Pυ =

=  u, υ

u, υ for any u, υ ∈ V;

for any u, υ ∈ V;

(b) ||Pu|| = ||u|| for every u ∈ V.

Use PTP = I and  u, υ

u, υ = uTυ.

= uTυ.

(a)  Pu, Pυ

Pu, Pυ = (Pu)T(Pυ) = uTPTPυ = uTυ =

= (Pu)T(Pυ) = uTPTPυ = uTυ =  u, υ

u, υ .

.

(b) We have

Taking the square root of both sides gives our result.

7.37. Prove Theorem 7.12: Suppose E = {ei} and  are orthonormal bases of V. Let P be the change-of-basis matrix from E to E′. Then P is orthogonal.

are orthonormal bases of V. Let P be the change-of-basis matrix from E to E′. Then P is orthogonal.

Suppose

Using Problem 7.18(b) and the fact that E′ is orthonormal, we get

Let B = [bij] be the matrix of the coefficients in (1). (Then P = BT.) Suppose BBT = [cij]. Then

By (2) and (3), we have cij = δij. Thus, BBT = I. Accordingly, B is orthogonal, and hence, P = BT is orthogonal.

7.38. Prove Theorem 7.13: Let {e1, …, en} be an orthonormal basis of an inner product space V. Let P = [aij] be an orthogonal matrix. Then the following n vectors form an orthonormal basis for V:

Because {ei} is orthonormal, we get, by Problem 7.18(b),

where Ci denotes the ith column of the orthogonal matrix P = [aij]: Because P is orthogonal, its columns form an orthonormal set. This implies  . Thus,

. Thus,  is an orthonormal basis.

is an orthonormal basis.

Inner Products And Positive Definite Matrices

7.39. Which of the following symmetric matrices are positive definite?

Use Theorem 7.14 that a 2 × 2 real symmetric matrix is positive definite if and only if its diagonal entries are positive and if its determinant is positive.

(a) No, because |A| = 15 − 16 = −1 is negative.

(b) Yes.

(c) No, because the diagonal entry −3 is negative.

(d) Yes.

7.40. Find the values of k that make each of the following matrices positive definite:

(a) First, k must be positive. Also, |A| = 2k − 16 must be positive; that is, 2k − 16 > 0. Hence, k > 8.

(b) We need |B| = 36 − k2 positive; that is, 36 − k2 > 0. Hence, k2 < 36 or −6 < k < 6.

(c) C can never be positive definite, because C has a negative diagonal entry −2.

7.41. Find the matrix A that represents the usual inner product on R2 relative to each of the following bases of R2: (a) {υ1 = (1, 3), υ2 = (2, 5)}; (b) {w1 = (1, 2), w2 = (4, 2)}:

(a) Compute  υ1, υ1

υ1, υ1 = 1 + 9 = 10,

= 1 + 9 = 10,  υ1, υ2

υ1, υ2 = 2 + 15 = 17,

= 2 + 15 = 17,  υ2, υ2

υ2, υ2 = 4 + 25 = 29. Thus,

= 4 + 25 = 29. Thus,  .

.

(b) Compute  w1, w1

w1, w1 = 1 + 4 = 5,

= 1 + 4 = 5,  w1, w2

w1, w2 = 4 − 4 = 0,

= 4 − 4 = 0,  w2, w2

w2, w2 = 16 + 4 = 20. Thus,

= 16 + 4 = 20. Thus,  .

.

(Because the basis vectors are orthogonal, the matrix A is diagonal.)

7.42. Consider the vector space P2(t) with inner product  .

.

(a) Find  f, g

f, g , where f(t) = t + 2 and g(t) = t2 − 3t + 4.

, where f(t) = t + 2 and g(t) = t2 − 3t + 4.

(b) Find the matrix A of the inner product with respect to the basis {1, t, t2} of V.

(c) Verify Theorem 7.16 by showing that  f, g

f, g = [f]TA[g] with respect to the basis {1, t, t2}.

= [f]TA[g] with respect to the basis {1, t, t2}.

(b) Here we use the fact that if r + s = n,

Then  . Thus,

. Thus,

(c) We have [f]T = (2, 1, 0) and [g]T = (4, −3, 1) relative to the given basis. Then

7.43. Prove Theorem 7.14:  is positive definite if and only if a and d are positive and |A| = ad − b2 is positive.

is positive definite if and only if a and d are positive and |A| = ad − b2 is positive.

Let u = [x, y]T. Then

Suppose f(u) > 0 for every u ≠ 0. Then f(1, 0) = a > 0 and f(0, 1) = d > 0. Also, we have f(b, −a) = a(ad − b2) > 0. Because a > 0, we get ad − b2 > 0.

Conversely, suppose a > 0, d > 0, ad − b2 > 0. Completing the square gives us

Accordingly, f(u) > 0 for every u ≠ 0.

7.44. Prove Theorem 7.15: Let A be a real positive definite matrix. Then the function  u, υ

u, υ = uTAυ is an inner product on Rn.

= uTAυ is an inner product on Rn.

For any vectors u1, u2, and υ,

and, for any scalar k and vectors u, υ,

Thus [I1] is satisfied.

Because uTAυ is a scalar, (uTAυ)T = uTAυ. Also, AT = A because A is symmetric. Therefore,

Thus, [I2] is satisfied.

Last, because A is positive definite, XTAX > 0 for any nonzero X ∈ Rn. Thus, for any nonzero vector υ,  υ, υ

υ, υ = υTAυ > 0. Also,

= υTAυ > 0. Also,  0, 0

0, 0 = 0TA0 = 0. Thus, [I3] is satisfied. Accordingly, the function

= 0TA0 = 0. Thus, [I3] is satisfied. Accordingly, the function  u, υ

u, υ = Aυ is an inner product.

= Aυ is an inner product.

7.45. Prove Theorem 7.16: Let A be the matrix representation of an inner product relative to a basis S of V. Then, for any vectors u, υ ∈ V, we have

Suppose S = {w1, w2, …, wn} and A = [kij]. Hence, kij =  wi, wj

wi, wj . Suppose

. Suppose

Then

On the other hand,

Equations (1) and (2) give us our result.

7.46. Prove Theorem 7.17: Let A be the matrix representation of any inner product on V. Then A is a positive definite matrix.

Because  wi, wj

wi, wj =

=  wj, wi

wj, wi for any basis vectors wi and wj, the matrix A is symmetric. Let X be any nonzero vector in Rn. Then [u] = X for some nonzero vector u ∈ V. Theorem 7.16 tells us that XTAX = [u]TA[u] =

for any basis vectors wi and wj, the matrix A is symmetric. Let X be any nonzero vector in Rn. Then [u] = X for some nonzero vector u ∈ V. Theorem 7.16 tells us that XTAX = [u]TA[u] =  u, u

u, u > 0. Thus, A is positive definite.

> 0. Thus, A is positive definite.

Complex Inner Product Spaces

7.47. Let V be a complex inner product space. Verify the relation

Using  ,

,  , and then

, and then  , we find

, we find

7.48. Suppose  u, υ

u, υ = 3 + 2i in a complex inner product space V. Find

= 3 + 2i in a complex inner product space V. Find

7.49. Find the Fourier coefficient (component) c and the projection cw of υ = (3 + 4i, 2 − 3i) along w = (5 + i, 2i) in C2.

Recall that c =  υ, w

υ, w /

/ w, w

w, w . Compute

. Compute

Thus,  . Accordingly,

. Accordingly,

7.50. Prove Theorem 7.18 (Cauchy–Schwarz): Let V be a complex inner product space. Then | u, υ

u, υ | ≤ ||u|| ||υ||.

| ≤ ||u|| ||υ||.

If υ = 0, the inequality reduces to 0 ≤ 0 and hence is valid. Now suppose υ ≠ 0. Using  (for any complex number z) and

(for any complex number z) and  , we expand ||u −

, we expand ||u −  u, υ

u, υ tυ||2 ≤ 0, where t is any real value:

tυ||2 ≤ 0, where t is any real value:

Set t = 1/||υ||2 to find  , from which |

, from which | u, υ

u, υ |2 ≤ ||u||2||υ||2. Taking the square root of both sides, we obtain the required inequality.

|2 ≤ ||u||2||υ||2. Taking the square root of both sides, we obtain the required inequality.

7.51. Find an orthogonal basis for u⊥ in C3 where u = (1, i, 1 + i).

Here u⊥ consists of all vectors s = (x, y, z) such that

Find one solution, say w1 = (0, 1 −i, i). Then find a solution of the system

Here z is a free variable. Set z = 1 to obtain y = i/(1 + i) = (1 + i)/2 and x = (3i − 3)2. Multiplying by 2 yields the solution w2 = (3i − 3, 1 + i, 2). The vectors w1 and w2 form an orthogonal basis for u⊥.

7.52. Find an orthonormal basis of the subspace W of C3 spanned by

Apply the Gram–Schmidt algorithm. Set w1 = υ1 = (1, i, 0). Compute

Multiply by 2 to clear fractions, obtaining w2 = (1 + 2i, 2 − i, 2 − 2i). Next find  and then

and then  . Normalizing {w1, w2}, we obtain the following orthonormal basis of W:

. Normalizing {w1, w2}, we obtain the following orthonormal basis of W:

7.53. Find the matrix P that represents the usual inner product on C3 relative to the basis {1, i, 1 − i }.

Compute the following six inner products:

Then, using  , we obtain

, we obtain

(As expected, P is Hermitian; that is, PH = P.)

Normed Vector Spaces

7.54. Consider vectors u = (1, 3, −6, 4) and υ = (3, −5, 1, −2) in R4. Find

(a) ||u||∞ and ||υ||∞, (b) ||u||1 and ||υ||1, (c) ||u||2 and ||υ||2,

(d) d∞(u, υ), d1(u, υ), d2(u, υ).

(a) The infinity norm chooses the maximum of the absolute values of the components. Hence,

(b) The one-norm adds the absolute values of the components. Thus,

(c) The two-norm is equal to the square root of the sum of the squares of the components (i.e., the norm induced by the usual inner product on R3). Thus,

(d) First find u − υ = (−2, 8, −7, 6). Then

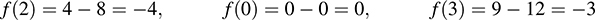

7.55. Consider the function f(t) = t2 4t in C[0, 3].

(a) Find ||f||∞, (b) Plot f(t) in the plane R2, (c) Find ||f||1, (d) Find ||f||2.

(a) We seek ||f||∞ = max(|f(t)|). Because f(t) is differentiable on [0, 3], |f(t)| has a maximum at a critical point of f(t) (i.e., when the derivative f′(t) = 0), or at an endpoint of [0, 3]. Because f′(t) = 2t 4, we set 2t 4 = 0 and obtain t = 2 as a critical point. Compute

Thus, ||f||∞ = |f(2)| = | − 4| = 4.

(b) Compute f(t) for various values of t in [0, 3], for example,

Plot the points in R2 and then draw a continuous curve through the points, as shown in Fig. 7-8.

(c) We seek  . As indicated in Fig. 7-3, f(t) is negative in [0, 3]; hence, |f(t)| = −(t2 − 4t) = 4t − t2

. As indicated in Fig. 7-3, f(t) is negative in [0, 3]; hence, |f(t)| = −(t2 − 4t) = 4t − t2

Thus,

(d)

.

.

Thus,

.

.

7.56. Prove Theorem 7.24: Let V be a normed vector space. Then the function d(u, υ) = ||u − υ|| satisfies the following three axioms of a metric space:

[M1] d(u, υ) ≥ 0; and d(u, υ) = 0 iff u = υ.

[M2] d(u, υ) = d (υ, u).

[M3] d(u, υ) ≤ d (u, w) + d(w, υ).

If u ≠ υ, then u − υ ≠ 0, and hence, d(u, υ) = ||u − υ|| > 0. Also, d(u, u) = ||u − u|| = ||0|| = 0. Thus,

[M1] is satisfied. We also have

and

Thus, [M2] and [M3] are satisfied.

SUPPLEMENTARY PROBLEMS

Inner Products

7.57. Verify that the following is an inner product on R2, where u = (x1, x2) and υ = (y1, y2):

7.58. Find the values of k so that the following is an inner product on R2, where u = (x1, x2) and υ = (y1, y2):

7.59. Consider the vectors u = (1, −3) and υ = (2, 5) in R2. Find

(a)  u, υ

u, υ with respect to the usual inner product in R2.

with respect to the usual inner product in R2.

(b)  u, υ

u, υ with respect to the inner product in R2 in Problem 7.57.

with respect to the inner product in R2 in Problem 7.57.

(c) ||υ|| using the usual inner product in R2.

(d) ||υ|| using the inner product in R2 in Problem 7.57.

7.60. Show that each of the following is not an inner product on R3, where u = (x1, x2, x3) and υ = (y1, y2, y3):

7.61. Let V be the vector space of m × n matrices over R. Show that  A, B

A, B = tr(BTA) defines an inner product in V.

= tr(BTA) defines an inner product in V.

7.62. Suppose | u, υ

u, υ | = ||u|| ||υ||. (That is, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality reduces to an equality.) Show that u and υ are linearly dependent.

| = ||u|| ||υ||. (That is, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality reduces to an equality.) Show that u and υ are linearly dependent.

7.63. Suppose f(u, υ) and g(u, υ) are inner products on a vector space V over R. Prove

(a) The sum f + g is an inner product on V, where (f + g)(u, υ) = f(u, υ) + g(u, υ).

(b) The scalar product kf, for k > 0, is an inner product on V, where (kf)(u, υ) = kf(u, υ).

Orthogonality, Orthogonal Complements, Orthogonal Sets

7.64. Let V be the vector space of polynomials over R of degree ≤2 with inner product defined by  . Find a basis of the subspace W orthogonal to h(t) = 2t + 1.

. Find a basis of the subspace W orthogonal to h(t) = 2t + 1.

7.65. Find a basis of the subspace W of R4 orthogonal to u1 = (1, −2, 3, 4) and u2 = (3, −5, 7, 8).

7.66. Find a basis for the subspace W of R5 orthogonal to the vectors u1 = (1, 1, 3, 4, 1) and u2 = (1, 2, 1, 2, 1).

7.67. Let w = (1, −2, −1, 3) be a vector in R4. Find

(a) an orthogonal basis for w⊥, (b) an orthonormal basis for w⊥.

7.68. Let W be the subspace of R4 orthogonal to u1 = (1, 1, 2, 2) and u2 = (0, 1, 2, −1). Find

(a) an orthogonal basis for W, (b) an orthonormal basis for W. (Compare with Problem 7.65.)

7.69. Let S consist of the following vectors in R4:

(a) Show that S is orthogonal and a basis of R4.

(b) Write υ = (1, 3, −5, 6) as a linear combination of u1, u2, u3, u4.

(c) Find the coordinates of an arbitrary vector υ = (a, b, c, d) in R4 relative to the basis S.

(d) Normalize S to obtain an orthonormal basis of R4.

7.70. Let M = M2,2 with inner product  A, B

A, B = tr(BTA). Show that the following is an orthonormal basis for M:

= tr(BTA). Show that the following is an orthonormal basis for M:

7.71. Let M = M2,2 with inner product  A, B

A, B = tr(BTA). Find an orthogonal basis for the orthogonal complement of (a) diagonal matrices, (b) symmetric matrices.

= tr(BTA). Find an orthogonal basis for the orthogonal complement of (a) diagonal matrices, (b) symmetric matrices.

7.72. Suppose {u1, u2, …, ur} is an orthogonal set of vectors. Show that {k1u1, k2u2, …, krur} is an orthogonal set for any scalars k1, k2, …, kr.

7.73. Let U and W be subspaces of a finite-dimensional inner product space V. Show that

Projections, Gram–Schmidt Algorithm, Applications

7.74. Find the Fourier coefficient c and projection cw of υ along w, where

(a) υ = (2, 3, −5) and w = (1, −5, 2) in R3.

(b) υ = (1, 3, 1, 2) and w = (1, −2, 7, 4) in R4.

(c) υ = t2 and w = t + 3 in P(t), with inner product

(d)  and

and  in M = M2,2, with inner product

in M = M2,2, with inner product  A, B

A, B = tr(BTA).

= tr(BTA).

7.75. Let U be the subspace of R4 spanned by

(a) Apply the Gram–Schmidt algorithm to find an orthogonal and an orthonormal basis for U.

(b) Find the projection of υ = (1, 2, −3, 4) onto U.

7.76. Suppose υ = (1, 2, 3, 4, 6). Find the projection of υ onto W, or, in other words, find w ∈ W that minimizes ||υ − w||, where W is the subspace of R5 spanned by

7.77. Consider the subspace W = P2(t) of P(t) with inner product  . Find the projection of f(t) = t3 onto W. (Hint: Use the orthogonal polynomials 1, 2t − 1, 6t2 − 6t + 1 obtained in Problem 7.22.)

. Find the projection of f(t) = t3 onto W. (Hint: Use the orthogonal polynomials 1, 2t − 1, 6t2 − 6t + 1 obtained in Problem 7.22.)

7.78. Consider P(t) with inner product  and the subspace W = P3(t).

and the subspace W = P3(t).

(a) Find an orthogonal basis for W by applying the Gram–Schmidt algorithm to {1, t, t2, t3}.

(b) Find the projection of f(t) = t5 onto W.

Orthogonal Matrices

7.79. Find the number and exhibit all 2 × 2 orthogonal matrices of the form  .

.

7.80. Find a 3 × 3 orthogonal matrix P whose first two rows are multiples of u = (1, 1, 1) and υ = (1, −3, 2), respectively.

7.81. Find a symmetric orthogonal matrix P whose first row is  . (Compare with Problem 7.32.)

. (Compare with Problem 7.32.)

7.82. Real matrices A and B are said to be orthogonally equivalent if there exists an orthogonal matrix P such that B = PTAP. Show that this relation is an equivalence relation.

Positive Definite Matrices and Inner Products

7.83. Find the matrix A that represents the usual inner product on R2 relative to each of the following bases:

7.84. Consider the following inner product on R2:

Find the matrix B that represents this inner product on R2 relative to each basis in Problem 7.83.

7.85. Find the matrix C that represents the usual basis on R3 relative to the basis S of R3 consisting of the vectors u1 = (1, 1, 1), u2 = (1, 2, 1), u3 = (1, −1, 3).

7.86. Let V = P2(t) with inner product  .

.

(a) Find  f, g

f, g , where f(t) = t + 2 and g(t) = t2 − 3t + 4.

, where f(t) = t + 2 and g(t) = t2 − 3t + 4.

(b) Find the matrix A of the inner product with respect to the basis {1, t, t2} of V.

(c) Verify Theorem 7.16 that  f, g

f, g = [f]TA[g] with respect to the basis {1, t, t2}.

= [f]TA[g] with respect to the basis {1, t, t2}.

7.87. Determine which of the following matrices are positive definite:

7.88. Suppose A and B are positive definite matrices. Show that:

(a) A + B is positive definite and

(b) kA is positive definite for k > 0.

7.89. Suppose B is a real nonsingular matrix. Show that: (a) BTB is symmetric and (b) BTB is positive definite.

Complex Inner Product Spaces

More generally, prove that  .

.

7.91. Consider u = (1 + i, 3, 4 − i) and υ = (3 − 4i, 1 + i, 2i) in C3. Find

7.92. Find the Fourier coefficient c and the projection cw of

7.93. Let u = (z1, z2) and υ = (w1, w2) belong to C2. Verify that the following is an inner product of C2:

7.94. Find an orthogonal basis and an orthonormal basis for the subspace W of C3 spanned by u1 = (1, i, 1) and u2 = (1 + i, 0, 2).

7.95. Let u = (z1, z2) and υ = (w1, w2) belong to C2. For what values of a, b, c, d ∈ C is the following an inner product on C2?

7.96. Prove the following form for an inner product in a complex space V:

[Compare with Problem 7.7(b).]

7.97. Let V be a real inner product space. Show that

(i) ||u|| = ||υ|| if and only if  u + υ, u − υ

u + υ, u − υ = 0;

= 0;

(ii) ||u + υ||2 = ||u||2 +||υ||2 if and only if  u, υ

u, υ = 0.

= 0.

Show by counterexamples that the above statements are not true for, say, C2.

7.98. Find the matrix P that represents the usual inner product on C3 relative to the basis {1, 1 + i, 1 − 2i}.

7.99. A complex matrix A is unitary if it is invertible and A− = AH. Alternatively, A is unitary if its rows (columns) form an orthonormal set of vectors (relative to the usual inner product of Cn). Find a unitary matrix whose first row is:

Normed Vector Spaces

7.100. Consider vectors u = (1, −3, 4, 1, −2) and υ = (3, 1, −2, −3, 1) in R5. Find

7.101. Repeat Problem 7.100 for u = (1 + i, 2 − 4i) and υ = (1 − i, 2 + 3i) in C2.

7.102. Consider the functions f(t) = 5t − t2 and g(t) = 3t − t2 in C [0, 4]. Find

7.103. Prove (a) ||·||1 is a norm on Rn. (b) ||·||∞ is a norm on Rn.

7.104. Prove (a) ||·||1 is a norm on C[a, b]. (b) ||·||∞ is a norm on C[a, b].

ANSWERS TO SUPPLEMENTARY PROBLEMS

Notation: M = [R1; R2; …] denotes a matrix M with rows R1, R2, … Also, basis need not be unique.

7.60. Let u = (0, 0, 1); then  u, u

u, u = 0 in both cases

= 0 in both cases

7.65. {(1, 2, 1, 0), (4, 4, 0, 1)}

7.66. (−1, 0, 0, 0, 1), (−6, 2, 0, 1, 0), (−5, 2, 1, 0, 0)

7.95. a and d real and positive,  and ad − bc positive.

and ad − bc positive.

7.98. P = [1, 1 −i, 1 + 2i; 1 + i, 2, −1 + 3i; 1 − 2i, −1 − 3i, 5]