In the 1890s two grieving expatriate artists—the tousle-haired painter Frank Duveneck and the aging literary lion and sculptor William Wetmore Story—each designed exceptional funerary monuments in Italy to their lost wives. These memorials, conceived with a full awareness of European sculptural traditions, became well known through photographs and copies back home in the United States, where they were viewed as each man’s highly individual and emotional response to personal tragedy.

The tomb effigy that Duveneck (1848–1919), a German American artist from Cincinnati, modeled would remain forever in a cemetery in Florence, the city where he and artist Elizabeth Boott Duveneck (1846–1888) lived and worked during a portion of their brief marriage. Like her acquaintance Marian Hooper, Lizzie Boott was born in Boston to a respectable family with an abiding interest in high culture, and she had a close relationship with her protective father. The two women shared a network of friends in elite circles that often overlapped on both sides of the Atlantic. Elizabeth’s mother died early, apparently of tubercular pneumonia, when the child was little more than one year old. Her widowed father, unhinged by this loss and the earlier death of an infant son, decided to raise his daughter abroad, ultimately settling in Florence’s intellectual expatriate community, where his sister lived. On their six-week sea voyage to the Continent the Bootts shared company with the Story family and would remain lifelong acquaintances.1 Lizzie grew up in Italy under the paternal guidance of Francis Boott and the watchful care of a beloved nurse, Ann Shenstone, moving to different apartments or pensions in the first years and finally settling in a villa on the hill of Bellosguardo above the city of Florence. There her father, a Harvard graduate and dedicated musical dilettante, refined his talents as an amateur composer and by all accounts devoted himself to her education and happiness, sharing with her his love for opera, theater, and art. That he succeeded—providing tutors in everything from painting and piano to voice, multiple languages, and swimming—is made clear by Henry James’s comment that Elizabeth was among the most exquisitely “produced” young women he had ever met. James called her “the admirable, the infinitely civilized and sympathetic, the markedly produced Lizzie” and described her as a “delightful girl” who had been “educated, cultivated, accomplished, toned above all, as from steeping in a rich, old medium.”2

Florence was an affordable place to live and study in those years for thousands of Americans. Some families came annually for several months at a time; thus, it seemed that all Boston passed through. Lizzie could count among her extended relations the sculptor Horatio Greenough, who had settled there until shortly before his death in 1852; his younger brother Henry married Lizzie’s aunt Fanny (Frances Boott Greenough). Touring Americans visited the studios of artists like the Cincinnati-bred sculptor Hiram Powers, Thomas Ball, and eventually Ball’s son-in-law William Couper. The Bootts also spent some winters in Rome, maintaining their family friendship with the poet-sculptor Story, who held court there for the expatriate community. At age five, Lizzie took part in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Story’s apartments in the Palazzo Barberini; she played one of Titania’s fairies, and James Russell Lowell acted the part of Bottom.3

Her father’s chamber music was also performed there. The art songs he wrote, setting often sentimental poetry by Story, Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and others to music, were favored back home in Boston, where he returned with Lizzie when she reached age nineteen to cement her American connections. During his lifetime, Boott published many albums of his songs (Figure 8), from cradle songs and nostalgic serenades to dirges, hymns, and patriotic tunes, including “Ah, When the Fight Is Won,” a tribute to Robert Gould Shaw’s Civil War regiment. Although they did not head home to Boston until the end of the Civil War, the Bootts had visited with the Shaw family numerous times on their European travels and followed accounts of the war and of “Bob’s” stirring service at the head of the Fifty-Fourth African American unit.4

In 1869, when the Bootts spent the month of July at the James family’s summer house in Connecticut, Henry James’s brother William advised a male friend to make Lizzie’s acquaintance quickly, because she was among those “first-class young spinsters” who might not stay single long. “Miss B.,” he confided, “although not overpoweringly beautiful, is one of the very best members of her sex I ever met.… I never realized before how much a good education … added to the charms of a woman.” The James family and the Bootts remained close over the years, with Henry especially writing scores of affectionate letters to Lizzie and her father.5

Elizabeth determined, however, to become a painter rather than a wife, and her father supported her quest for a serious artistic career. She studied in Boston with artist William Morris Hunt, who offered an influential women’s class, and she also attended lectures there by sculptor William Rimmer before working with the French Salon painter Thomas Couture near Paris. She first met Frank Duveneck in the role of a gifted art student seeking his instruction. She and her father had purchased one of Duveneck’s paintings in 1875 after visiting an exhibition of his work in Boston, and she was impressed with the bold, expressive style this rough-mannered and rambunctious-spirited midwesterner had honed during his studies in Munich in the early 1870s. The exuberant confidence of his freely painted, coloristic pictures like Whistling Boy (1872), which demonstrate his absorption of the painterly principles of Frans Hals, Diego Velázquez, and Rembrandt, appealed to this sophisticated young woman.6

Figure 8.

Francis Boott, “Garden of Roses,” with words by W. W. Story and music by F. Boott (Boston: Ditson, 1863). Sheet music cover. Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library of the Harvard College Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In 1879 Lizzie Boott, by then in her early thirties, joined Duveneck in Bavaria (in the village of Polling, outside Munich) for private studies. He had established a moveable “school,” and his loyal students were dubbed the “Duveneck boys.” Lizzie persuaded them to decamp to Florence to hold classes there for female students, a situation that offered the artists steady income and patronage. Duveneck and his “boys” began a pattern of spending winters in Tuscany, where he painted Lizzie’s father in an imposing aristocratic pose in 1881, and summers in Venice.7

An on-again, off-again courtship also began, in which Duveneck wooed Miss Boott and she gently resisted over the years. While he wandered about Italy, she traveled to Spain with other women artists and exhibited her oil and watercolor paintings in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia in 1883, 1884, and 1885. Reviewers spoke of the vigor, intensity, and “curiously unfeminine” handling of her oil painting as well as the mastery of color and harmony in her pictures of flowers (Figure 9), animal heads, still-life scenes, and portraits, which included depictions of black and gypsy sitters as well as elite mothers and children.8 Finally, in the fall of 1885, she surrendered to Duveneck’s ardent pursuit despite the severe disapproval of her father and others, including Henry James, who worried about her suitor’s reliability, gentility, and financial health and acumen. Duveneck, James wrote, was creating work that was “remarkably strong and brilliant” but suffered from “an almost slovenly modesty and want of pretension” and a lack of drive for worldly success. While James admired the couple’s “unconventionalism” and found Duveneck to be “an excellent fellow” in some respects, he commented at one point: “Her marrying him would be, given the man, strange (I mean given his roughness, want of education, of a language, etc.).” To another correspondent, he confided in even stronger terms, “He is illiterate, ignorant, and not a gentleman.”9

Figure 9.

Elizabeth Lyman Boott, Narcissus on the Campagna, about 1872–73. Oil on panel, 15 7/8 × 7 in. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Robert Jordan Fund, 1993.630. Photograph © 2014 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Objections aside, the couple married in Paris on March 25, 1886, with the vows exchanged before a magistrate in the Bootts’ apartment there. According to one account, Duveneck understood so little French that Lizzie had to prompt him to respond during the ceremony. Her father agreed to join them only after Duveneck signed a prenuptial agreement relinquishing any claim to her estate.10

The romance of Lizzie Boott and Frank Duveneck was an oddly appealing meeting of two opposing worlds. Here was Elizabeth, a motherless only child who had spent her life at the center of a sophisticated and comfortable world dedicated to her welfare. Duveneck must have offered something she still found missing—a spontaneous sweetness and unconditional, uncultivated love. “He is a child of Nature but a natural gentleman,” she wrote. “He seems to have led the queerest, most vagrant sort of existence among monks and nuns and convents in America and rough art students here. He is the frankest, truest, kindest hearted of mortals, and the least likely to make his way in the world.”11 By all accounts, Duveneck was an extraordinary and inspiring teacher, whose adoring circle of friends worried about his lack of personal ambition. Though financially impoverished, he was energetically affectionate and illogically generous to those around him. “He seems to be perfectly reckless to give away all his sheckles [sic] to his friends,”12 Lizzie told friends. While she was fluent in French, Italian, and German, he is said to have spoken an almost comedic mix of English and German in the European years and was so poor that he had to borrow $100 to cover his wedding costs.

Elizabeth’s dark hair, which she parted down the center and pulled back into a chignon, set off an open face with large and luminous brown eyes, arched eyebrows, high cheekbones, an aquiline nose, and a strong chin. She was not a delicate flower, but a tall, slender, European-bred beauty. Duveneck, by contrast, came from Covington, Kentucky, a tight-knit working-class German American immigrant community near Cincinnati. His parents ran a neighborhood beer garden and an ale-bottling business. He had at first set his sights, as an impressionable teenager who had demonstrated an unusual artistic facility, on becoming a decorative painter for Roman Catholic churches and seminaries. After arriving in Munich, however, he left the Church and these intentions behind and adopted the life of a Bohemian artist creating picturesque, Halsian paintings of everyday people in dark settings. Handsome in his youth, he was five foot nine and sturdily built, with blond or light brown hair and a thick mustache. Deep-set blue eyes and a distinctive cleft in his chin marked his strong facial features. On his return home from Europe in the 1870s, he swung a cane and affected a Munich cape draped back from his shoulders.13

The couple lived at first with Lizzie’s father and painted together in Florence for a time before they moved to Paris with their son, who was born in December 1887 and named Francis Boott Duveneck after his grandfather.14 A portrait of the newlyweds with Francis Boott and nurse Shenstone (Figure 10) on the terrace at Bellosguardo hints at the sometimes tense dynamics of the new arrangement, as Lizzie hovers devotedly near her protective father, enthroned in a rattan armchair. Her husband is left to pose stiffly in the background with the beloved family servant who had helped to raise Lizzie. At the same time, the couple’s poses are uncannily parallel, his cane matching her umbrella held perfectly vertically by a gentle gloved hand.

Both Lizzie and Frank planned submissions to the next Salon in Paris. But in the spring of 1888, Lizzie died of pneumonia after a brief illness. They had been married for only two years and she was just forty-one years old when she passed away on March 22, 1888. For her father, history must have seemed to be repeating itself, as he clung to the three-month-old infant she had left for others to raise.

Just before she died Lizzie sat for a portrait in her wedding costume, a brown dress with muff, cape, and bonnet—a picture that Duveneck would submit to the Paris Salon (Plate 6). “Frank has painted a picture of me full length with which Papa is delighted and also all those who have seen it,” she wrote on March 13, but complained of exhaustion: “This has taken much of his time and of mine and I am always much occupied with the baby.”15

Figure 10.

Elizabeth Boott Duveneck, Francis Boott, Frank Duveneck, and Ann Shenstone, ca. 1886 / unidentified photographer. Frank and Elizabeth Boott Duveneck Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Duveneck wrote his brother Charles, “She died yesterday morning at half past seven after four days of great suffering. I can hardly get used to understand this sad blow.”16 Having long ago ceased attending church services, the artist did not appear to seek religious consolation. Rather, he wrote Charles mournfully: “I suppose I must understand it like many others must and in fact all of us must experience [death’s blow] sooner or later.… I shall try and make the best of it.… This morning my wife was taken to a temporary resting place and in the month of May we will take her to Florence her favorite home where she has lived most of her life, there to rest in that beautiful country of flowers and cypresses she so dearly loved.”17

Elizabeth Boott Duveneck was buried in the Cimitero Evangelico degli Allori (Evangelical Cemetery of the Laurels), located on the outskirts of Florence near the Bootts’ Bellosguardo home. As in Catholic Rome, Protestant foreigners in Florence had to be interred outside the city walls. From 1828 to 1877 the peaceful Cimitero degli Inglesi (English Cemetery) on a hill just outside the city’s Porta Pinti gate had been the burial place of many distinguished foreigners, including Hiram Powers, poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Henry Adams’s sister Louisa. Nearly ninety Americans were interred there among the fourteen hundred graves, primarily the remains of Anglo-Florentines, Swiss, and sometimes Russian expatriates, or Italian Protestants. During the Risorgimento movement to unify Italy, however, the capital was moved from Florence to Rome in mid-1871; the Florentine city walls were torn down and the “English Cemetery,” no longer outside the city boundaries, was closed. The Cimitero Evangelico degli Allori was designated as the new burial site for non-Catholics.18

Elizabeth’s body was placed in a grave at the Allori cemetery in late April amid rows of tall cypresses. “Great masses of flowers were heaped upon it and her Florentine friends gathered in large numbers to say farewell,” James recalled.19 With Duveneck’s apparent assent, Francis Boott took young “Frankie” back to Boston for a correct New England upbringing by a wealthy relation, Arthur Lyman, who had already raised a large brood of his own children. Boott clearly realized that the boy was Lizzie’s most enduring memorial and wanted him to be nearby. With his own rearing in an elite Boston family and his decades spent in a highly educated Anglo-American community abroad, Boott apparently did not feel the child could be properly raised by a single artist-father in distant Covington, where Duveneck would return to be near his mother and siblings. Duveneck may have doubted his own parental abilities as well.20 Although the Cincinnati area had a long and distinguished history as a midwestern center of art, Boott and his circle did not grant it any measure of equality to New England. Henry James wrote snidely to a friend of the “strange fate” that Lizzie had lived just long enough “to tie those two men [Duveneck and her father] with nothing in common, together by that miserable infant and then vanish into space leaving them face to face!” He added, “The child is the complication—without it he and Duveneck could go their ways respectively.”21 Mrs. Lyman noted in her journal that Duveneck had “burst into tears and sobbed aloud” after she told him, “You must come to see [Frankie] often.”22

Each man would memorialize Lizzie in his own way. Boott’s orchestration of a psalm that had often been recited to accompany the burial of the dead was published that year, with the singers repeating “Miserere mei Deus” (Have Mercy on me, O God).23 Duveneck’s portrait of Lizzie was transformed into a memorial when it was exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston a month after her death above a laurel wreath, with five of her paintings grouped around it in the main gallery.24

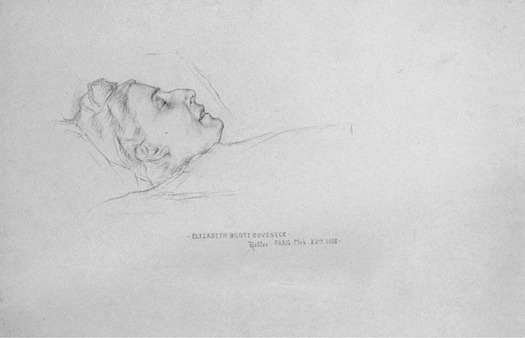

After spending an extended time in Boston, Duveneck returned home to the Cincinnati area carrying a deathbed drawing of Lizzie by his friend Louis Ritter (Figure 11).25 To ease his pain and create a permanent memorial that would be a gift to his father-in-law and son, he collaborated with a younger sculptor named Clement J. Barnhorn (1857–1935) on modeling a recumbent figure of his dead wife, to be cast in bronze. The moving sculpture that resulted would win Duveneck a kind of redemption from her circle of relations and admirers. A number of replicas were eventually displayed in U.S. museums, making the sculpture well known to the American public and keeping the image of Elizabeth Boott Duveneck alive on both sides of the Atlantic.

Figure 11.

Louis Ritter. Post-Mortem Portrait of Elizabeth Boott Duveneck. Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of Frank Duveneck, 1913.880.

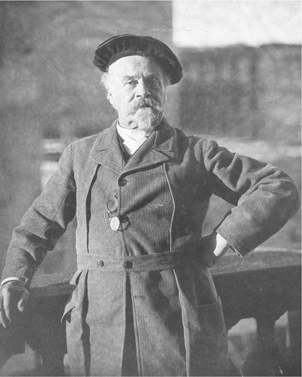

While the scrappy Duveneck had difficulty winning acceptance among the Boston elite, William Wetmore Story (1819–1895) and his wife, Emelyn Eldredge (1820–1894), had once been held in the highest regard of New England society. During a large share of their five decades of marriage, Story, a sculptor, poet, and raconteur of international renown, and Emelyn had been at the center of a literary and artistic circle of Americans and Europeans who made Italy their mecca. From the Brownings to Nathaniel Hawthorne (who wrote Story into his novel The Marble Faun), the expatriate community found itself drawn to the couple’s home in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome, where the family settled at midcentury. For their visitors, the Storys often expressed a lighthearted approach to life. The Boston-bred Story (Figure 12)—also an amateur dramatist and musician, Harvard-educated lawyer, and biographer of his famous father, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story—could be boyishly sprightly and “wildly funny.” Described by his admirers as an inspired genius and cosmopolitan social charmer with a “beautiful smile,” he wrote “little parlor comedies, in which he would act himself, with his children.” And he joined in song and conversation, the “gay talker of the company.” He had a flair for mimicry, a taste for the hilariously histrionic, and fondness for the theatrical, one observer recalled. He was such a man of the world that he once jested, “I am an Italian, born by mistake in Salem,” Massachusetts.26

Figure 12.

William Wetmore Story, ca. 1870 / unidentified photographer. Charles Scribner’s Sons Art Reference Department records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

On the occasion of their fiftieth wedding anniversary, “Congratulations poured in from wheresoever the English language was spoken. The presents on this occasion filled several rooms,” a journalistic acquaintance recalled of the couple’s October 31, 1893, celebration in Rome. “It is to be doubted whether the golden wedding of any Americans on the continent ever attracted more attention than did that of Mr. and Mrs. Story.”27

Now, however, this rich life was near its end. Story, in his seventies, had become a gray eminence, still beloved only to a dwindling circle of friends for whom he represented the lingering graciousness of an earlier era. His sculptural career was derided by others as a remnant of a moldering past. While he enjoyed the attentions of his three children and his grandchildren, the new generation of American artists had shifted its focus to Paris and adopted a Beaux-Arts aestheticism, favoring bronze sculpture and rejecting his brand of highly narrative white marble neoclassicism. Story, whose first commission had been a sculpture of his father for the chapel of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, went on to create a series of brooding mythological, literary, and biblical figures. These imaginative portrayals of powerful or emotionally wrought women—from Cleopatra and Medea to Sappho, Judith, and Delilah—earned him a wide reputation in the 1860s and 1870s (Figure 13). Henry James, who at the request of the sculptor’s family wrote (with some personal reluctance) a highly complimentary biography of Story, noted that his melodramatic works appealed to the public in those decades because of “the sense of the romantic, the anecdotic, the supposedly historic, the explicitly pathetic. It was still the age in which an image had, before anything else, to tell a story.” The sculptor, James added, “told his tale with … a strong sense both of character and of drama, so that he created a kind of interest for the statue which had been, without competition, up to that time, reserved for the picture. He gave the marble something of the color of the canvas.”28

Figure 13.

William Wetmore Story, Medea, 1865; executed 1868. Marble, 82 1/4 × 26 3/4 × 27 1/2 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of Henry Chauncey. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Even Story’s portraits of leading Americans, more popular back home, eliminated any vestiges of the modern trouser and presented them with suggestions of antique garb or without any clothing at all. Marian Adams was one of the touring Americans who visited his studio but who, as a representative of a younger generation, did not appreciate his narrative, classicizing style. In an 1873 letter she commented with disdain, “Oh! How he does spoil nice blocks of white marble.” She then compared what she found there with a hometown icon: “Nothing but sibyls on all sides.… Call him a genius! I don’t see it. I think Dr. Bigelow’s Mt. Auburn sphinx is as good really as anything in his [Story’s] shop.” Story, she warned with an acid irony, “will have to ornament tombs in a year or two if he goes on at this rate.”29

At times Story poured out the melancholy of his life experiences, including the loss of a son, in his poetry. Francis Boott published a song in D flat, “I Am Weary with Rowing,” in 1857 after one of Story’s compositions: “I am weary with rowing, with rowing, Let me lay down and dream … I can struggle no longer, no longer; Here in thy arms let me lie … In these arms which are stronger, are stronger Than all of this earth, Let me die, let me die.”30

By the late 1880s Story’s sculptural imagery, based on the imagination, and his artistic and often sentimental literary goals were perceived as outdated. While he had been given the honor of writing the catalogue entry for the American section of the 1876 world’s fair, his entry Salome for the 1889 fair in Paris was deemed “old fashioned” and spurned by the jury. It ultimately won a space in the American exhibition there only because the weighty female figure had already been shipped to France and Story’s son Julian and others appealed for its display, citing the sculptor’s fame and advanced age.31

Along with this decline in reputation, Story witnessed the advancing illness of his wife, long an indefatigable and active force in his career. “She was my life, my joy,” he recalled later. He reportedly fainted when a doctor informed him of his wife’s fragile health some years before her death.32

Within a few months after the anniversary celebration, Emelyn experienced “progressive paralysis” and then a second stroke.33 She passed away on January 7, 1894. At a crowded funeral service in St. Paul’s American Church on the Via Nazionale, Story “sat in a front seat bent low under the weight of his grief, supported on either side by his son … and his daughter-in-law,” the New York Herald reported. Emelyn’s coffin was covered with flowers, as was the floor around it. Flowers have often been a symbol of life’s ephemerality, its brief beauty and inevitable end. The wealth of blooms at the funeral were said to visualize the love and sympathy of Rome’s upper-class English-speaking community, which had established the Episcopal church (also known as St. Paul’s Within the Walls) in the late 1850s.34

Emelyn was described in newspaper tributes as the “wife of the famous American sculptor,” and Story said his own “reputation as an artist and man of letters … is largely indebted” to her. In an obituary notice placed in the Boston Transcript, he wrote that the death of this “remarkable woman … closes the book of a past generation.” He recalled in his florid, poetic manner the long, flaxen curls of her youth and years of companionship, and declared, “What is left seems to be but a blank of Silence, a dead wall which, when I cry out … only echoes back my own voice.”35 In a letter to Julian, he expressed similar feelings: “I know not what I shall do without her—all my thoughts all my memories every place is filled by her and yet she is not here.… I can only cry out in my desolation.”36

Story arranged for his wife’s burial in the beautiful Protestant Cemetery in Rome, the resting spot for expatriates from many nations, including the English poets John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley. It was Shelley who once wrote that the site, famed for its terraced slopes, cypresses, and vistas, was so sweet a place that it almost “makes one in love with death.” The cemetery, near the Testaccio hill and the Cestius Pyramid, was once called Cimitero Acattolico, the place—as in Florence—set aside for burial of non-Catholics outside the ancient walls of the city. The Storys were Episcopalians and had interred their first son in the cemetery as early as 1853.37 Encouraged by his children and friends, Story soon began a monument for Emelyn’s gravesite there. It was to be his final completed project.38

Story had previously created at least one tomb sculpture, a stiff recumbent figure of founder Ezra Cornell, for Cornell University, where it was placed in the memorial mausoleum of Sage Chapel in the mid-1880s. Now designing the sculpture in his wife’s memory seemed to allow him to carry on, converting grief and loneliness through his special skills into a new creative force. He turned from classicizing restraint and the simmering emotion found in his most celebrated works to a figure that symbolized desolation and the unregulated release of feelings, a weeping angel almost human in its frailty, vulnerability, and sorrowful response to God’s will (see Plate 4). “I am making a monument to place in the Protestant Cemetery,” the widower wrote a relative in the spring of 1894. “And I am always asking myself if she knows it and if she can see it. It represents the angel of Grief, in utter abandonment, throwing herself with drooping wings and hidden face over a funeral altar. It represents what I feel. It represents Prostration. Yet to do it helps me.”39

Many letters from family members mentioned concern that Story had stopped eating following Emelyn’s death. After visiting the aged sculptor in late 1895 at the Palazzo Barberini, Henry James wrote to Francis Boott, “I saw poor W.W. in Rome.… he was the ghost, only of his old clownship—very silent and vague and gentle. It was very sad and the Barberini very empty and shabby.”40

In October 1895 Story died at his daughter’s country villa at Vallombrosa, a former Medici hunting lodge outside Florence. Hundreds attended his funeral at St. Paul’s Within the Walls, and the event was widely noted in the international press.41 Story was laid to rest with Emelyn beneath his kneeling angel, leaving three children to carry on his legacy. The barefoot angel rests her head on one lithesome arm, with the other arm extended dejectedly but beautifully before her. The tips of her sagging wings touch the pedestal, and her gown flows downward in long, sad lines. On the front of the white marble monument, the name EMELYN STORY is inscribed within a stone garland. The rest of the inscription reports that she was born in Boston and died in Rome, key moments and places in her life’s trajectory. On the east side of the monument were added the words:

THIS MONUMENT

THE LAST WORK OF W.W. STORY.

EXECUTED IN MEMORY OF HIS BELOVED WIFE / ROMA 1895

HE DIED AT VALLOMBROSA OCTOBER 7TH 1895

AGED 78 YEARS