The Milmore Memorial emerged from a different process of creation and from a more distant, businesslike relationship between the sculptor Daniel Chester French and his patrons. Unlike Henry Adams, who insisted on a veil of privacy and a strategy of indirection, the Milmore heirs wanted the monument to cement the public fame of the departed sculptor brothers. Joseph Milmore’s widow and son insisted that the Milmore name be prominently incised on the memorial and on later replicas. The resulting monument can also be viewed as offering a gently hopeful narrative in comparison with the more questioning attitude presented by the Adams Memorial. Its universalizing drama of youth cut off in its prime by death touched viewers from many backgrounds who saw in it a variety of themes related to Christian love, the value of creative labor, memories of war, and the ultimate mystery of death.

Little correspondence survives about the monument commission, but it seems certain that James Bailey Richardson, the prominent Boston lawyer who was co-executor of the Milmore estate, discussed it with French soon after Joseph’s will was settled, finally concluding an agreement in late 1889 for an “artistic” bronze monument of “heroic” scale.1 The sculptor was given considerable liberty—as much or perhaps even more than Saint-Gaudens—in conceiving and composing the memorial design.2 He quickly abandoned the idea, suggested in the Milmore wills, of including busts of each of the brothers as well as a portrait of their mother, in favor of a large, bronze, high-style tableau featuring a majestic angel reaching out to stay the hand of a young sculptor.

“I am working on the design for the Milmore memorial, which will test my abilities to do an ideal thing,” French wrote his brother William, director of the Art Institute of Chicago, in February 1889, welcoming the opportunity to make a major sculpture drawn from his imagination.3 French had been seeking an opportunity to design an angelic grouping, especially following the recent loss of his own sister and father. In her biography Journey into Fame, his daughter Margaret Cresson says the Milmore project “interested him greatly. It looked as though at last he would be asked to do his ‘Angel of Death,’ an idea that he had been turning over in his mind for a long time.”4 French knew well that this sculpture, so different from the historical and portrait monuments he had been creating in his early career, would be viewed as part and parcel of his own legacy as well as the Milmores’ renown. It was also his first high relief, a form in which he would prove his mastery again and again over time. He likely publicized the project to promote his career; in July 1889, for example, the Magazine of Art would report the news that “A monument to Martin Millmore [sic], the sculptor, is to be erected in the Forrest [sic] Hill Cemetery.… It will be the work of Daniel Chester French.”5

French was just completing his formative years as a sculptor and ambitious to take his place in the art world. Born in 1850 in New Hampshire, he had moved with his three siblings and widowed father, a lawyer-farmer who later became assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury, to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and then to Concord a little to the north, where his family became acquainted with some of the surviving members of the transcendentalist literary community.6 He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a year but struggled in subjects like chemistry and algebra and never completed his studies there. With the help of tools loaned by artist May Alcott (a younger sister of writer Louisa May Alcott), he began modeling small portraits and animal figurines at home. After a month of training in the studio of sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward in New York in 1870 and lessons during two winters in Boston from artists William Rimmer and William Morris Hunt, the young man won a local commission to make a statue of a vigilant Minuteman (1875) for the centennial of the Battle of Concord in the American Revolution. He labored two years on the monument, first envisioned in granite and then finally cast in bronze. Owing to his inexperience, French asked only to be paid his expenses for this single-soldier statue, which launched his career, but he was awarded an additional $1,000 after philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, among other influential citizens, praised the result. “If I ask an artist to make me a silver bowl and he gives me one of gold I cannot refuse to pay him for it if I accept it,” Emerson wrote.7 Shortly before the dedication of the Minuteman, French headed to Italy for a year and a half, accepting an invitation to live in Florence with the family of his friend Preston Powers, the son of sculptor Hiram Powers, and to work in the nearby studio of Thomas Ball, who became a lifelong mentor for him as he would also be for Martin Milmore. After his return to the United States in 1876, French made portrait busts, including one of Emerson, and designed a statue of benefactor John Harvard for Harvard University. His father’s position as a high official in the Treasury Department in Washington in those years also helped him to secure contracts for several projects decorating government buildings.

Seeing that other artists of his generation were training in Paris rather than Italy, the young sculptor also considered going to France to study. He finally went in October 1886 after his father’s death late the previous year. He accompanied his stepmother, Pamela Prentiss French, who was struggling with her bereavement, on the trip to Europe. She was described as making “a pathetic picture in her deep black dress … her grief … too living to witness calmly,” and friends suggested that travel overseas would help her to recover.8

In Paris, French worked on a marble statue of Michigan senator Lewis Cass for the U.S. Capitol, took drawing classes, signed up for Antonin Mercié’s evening sculpture class, and studied firsthand the sculpture in museums and the work of French contemporaries such as Paul Dubois and Emmanuel Frémiet.9 His experience in France was different from that of Saint-Gaudens, however. He admitted a real shyness about his ability to speak the language, relying in part on Anglophone acquaintances.10 In addition, he was older when he arrived and came from a more refined social and professional background than many French sculptors. He said later that he wished he had gone to Paris earlier. While previous generations of American sculptors had looked to Italy as their training ground, the art of neoclassicists such as William Wetmore Story was by this time spurned as outdated. Story, for his part, denounced France’s artistic influence as a contagion afflicting U.S. art—a system in which mastery of technique was given priority over ideas, resulting in “a debauched imagination” and a corruption of sentiment.11 But Story’s was the voice of the past. Saint-Gaudens was seen as the leading edge of the post–Civil War generation that chose to study in Paris, modeling more naturalistic figures, which they produced in bronze instead of marble and in contemporary or historical dress instead of togas, putting greater emphasis on use of the life model to understand anatomy, on learning technique through systematic training, and on melding sculpture with other media in Beaux-Arts architectural settings. Daniel Chester French straddled all of these traditions in his training. Writer-sculptor Lorado Taft said French may actually have gained an advantage by his late arrival in the City of Light and by his abbreviated stay there: his approach already partly shaped, his oeuvre retained a particularly “American” character, in that Chicago critic’s view, and French was not seduced by an overly facile European artfulness. Regardless of questions of style, skill, or artistic affiliation, the years in Boston, Florence, and Paris helped the sculptor forge a network of useful connections.

French was a handsome young man, with large eyes, a strong chin, and a bushy mustache, but his head of thick dark hair was already beginning to thin above the forehead. Tall and slim, he loved the outdoors; photos show him walking, canoeing, and on horseback. At the time of the Milmore commission, he had just recently married his cousin Mary French, after wavering over the possible controversy the match with a close relation might inspire. The couple moved to cosmopolitan New York in part to assure acceptance. While there, French worked on his portrait statue of Thomas Gallaudet for the Columbia Institution for the Deaf (now Gallaudet University) in Washington, D.C., which demonstrated his new skill in multifigure composition. Gallaudet, a pioneering educator of the deaf, is shown teaching his first student to form the letter A in sign language. By this time, Saint-Gaudens was often consulted about public commissions, and French chided him half-jokingly in mid-1887 about venturing into “my huckle-berry patch” for having lent possible support to a different (deaf) sculptor for the Gallaudet project. Saint-Gaudens chalked this up to a misunderstanding,12 and later aided French by advising him to lengthen the figure’s legs. This suggestion wound up delaying French’s wedding, but the young man expressed gratitude, saying, “[W]hen you can pin Saint-Gaudens down and get a real criticism from him, it is better than anybody’s, and so what can I do except give the Doctor an inch or two more of leg.”13 Saint-Gaudens would become an important booster of French’s career, helping him, for instance, to gain a key role in the decoration of the 1893 world’s fair in Chicago. French, in return, would later push the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to acquire works by Saint-Gaudens for its influential American sculpture collection.14

By the fall of 1889 French had completed a small maquette (Figure 40) for his Milmore Memorial.15 French had an unusual ability to conceive his work in three dimensions at an initial stage. Ball had advised him that “the closer we adhere to our small models if they have been studied carefully, the more grand and broad our large work will be.”16 In this respect French put less emphasis on the fluidity of process preferred by Saint-Gaudens, who could begin a sculpture with a primitive stick figure and allow it to emerge over time through myriad instances of trial and error. French’s early sketch for the Milmore Memorial established the basic elements of the final composition: a majestic winged angel at left facing a sculptor, both figures modeled in high relief. The monument’s focal point is the angel’s beautiful gesture, reaching across to touch the sculptor’s chisel and arrest the surprised youth’s attention. She stands ready to guide him on an untimely journey to another realm. In the maquette, even more than in the final version, the angel’s movement recalled—and at the same time inverted the meaning of—the famous scene in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling in which God stretches out his hand to give life to Adam. Given that sculpture in this period had limited means (for instance, lack of color range and a restricted ability to include background and atmosphere), gesture was a vital tool, and French recognized in laying out his dramatic narrative that touch could be the most moving gesture of all. From the beginning, the choice of a high-relief format contributed to a pictorial quality for the sculpture—requiring a frontal view and not allowing the greater multiplicity of perspectives found in works in the round like the Adams Memorial. French was aware that a relief format was well suited to his narrative theme, implying a passage of events over time: the angel’s arrival, the youth’s recognition, and their imminent departure together.

Figure 40.

Daniel Chester French, clay maquette for the Milmore Memorial, 1889. Courtesy of the Chesterwood Archives, Chapin Library, Williams College, gift of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Chesterwood, a National Trust Historic Site in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

A photograph of this maquette was no doubt the basis for the December 1889 memo of agreement that French signed with Richardson for a monument to be called The Angel of Death Stay the Hand of the Sculptor. “It shall consist in part of two bronze figures of heroic size, and such other bronze background placed in stone, as shall be required to give it the best artistic effect,” the contract said, promising that the final sculpture would be “substantially like the design heretofore submitted in photograph.” French agreed to finish the project within two years in exchange for payments totaling $9,400.17

What sparked French’s interest in angels? French was not a churchgoing man, although his wife, like her mother, aunt, and older sister, had attended the all-girls Convent of the Visitation high school associated with Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and must have had a thorough religious education there.18 A letter he received from Sarita Brady, a family relation, after the 1881 assassination of President James Garfield suggests the kind of language he was surrounded with when discussions of death took place. Brady, also raised a Roman Catholic, noted that the president “had passed into the Great Mystery of Death.”19 French would later talk about the Milmore Memorial as expressing hopefulness about a sweet hereafter, regardless of one’s beliefs.20 Yet when Thomas Ball’s wife, Ellen Louisa Wild, died in early 1891, French wrote of his sheer inability to express his painful feelings, telling his former teacher, “I grieve with you and [your daughter] Lizzie. O my dear, dear friend and master, I find I cannot write to you now. The poor offering of my sorrow and pity and sympathy is too inadequate to bring you at this time even though I know you will value it.”21

French’s interest in angels was inspired in part by his passion for nature. As he prepared his working model for the Milmore monument, he requested specimens of bird wings from his boyhood friend William “Will” Brewster, who had become curator of ornithology at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. He and Brewster had tramped Cambridge fields together on birding excursions and pored over Audubon and Nuttall ornithology handbooks during their childhood. “The Judge” (as French’s father was often called) also loved birds and knew something about taxidermy, so he had shown them how to stuff birds. French kept a bird book in his youth. He and Brewster stayed in touch over the passing decades via letters and occasional visits. After the death of French’s younger sister Sallie, for example, Brewster sent word in 1883 of his deep sympathy: “[S]uch blows must come to all of us, sooner or later, and we must bear them with what strength we may. Only believe that I am feeling very strongly for you and that I would do anything that I could to help or comfort you.”22

On October 5, 1890, French wrote Brewster “on a matter where our pursuits join hands. I have this winter to model an angel and it occurred to me the other day that you might help me in the study of wings.” Wondering if his friend could get him “a lot of them” on an upcoming trip to Umbagog Lake, which straddles the New Hampshire–Maine border, he said, “I should like a half dozen pairs or so of different kinds and sizes, not with a view of copying any one particular specimen, but for the purpose of studying up on the subject. They would serve my purpose best, dried just as they naturally close.”23 Mere “copying” was not his goal; French once commented that his objective instead was to look to nature but improve on it.

French was also a longtime friend of artist and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer, best known today for his large oil paintings of his children with angelic wings based on real, feathered reconstructions. Although one of these paintings is entitled Angel (Figure 41), Thayer most often referred to his images of idealized women and cherubic children simply as “winged figures” and said the feathers were added primarily to lift his models out of the commonplace. He recognized that the wings provided an “exalted atmosphere” and majesty outside of or beyond Christian iconography,24 and his paintings remain popular with museum audiences today. When French was in Paris he would have seen the many ways in which European sculptors used wings to add a sense of motion, of the supernatural, or to indicate that a figure is an allegory, representing an abstract idea. These would have included the celebrated winged figures, for example, of Dance, Lyrical Drama, Instrumental Music, and Harmony in front of the Paris Opéra, entirely unrelated to solemn Christian themes.

Figure 41.

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Angel, 1887. Oil, 36 1/4 × 28 1/8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.112.

In the Milmore Memorial, the angel linked the sculptural grouping securely to another significant tradition, winged figures made for American cemeteries in the nineteenth century. These angels, who are depicted guiding souls, guarding graves, recording in books, and pointing up toward heaven, appear in large numbers and in a wide array of poses. Their wings enable them to travel between earth and the world beyond, scholar Elisabeth Roark notes, and are “a sign of super-human spirituality, power, and swiftness.”25 Many of these sculptures were insipid marble or granite angels manufactured by local quarries or funerary monument companies. But the Milmore Memorial angel could also be interpreted as a specific allusion to Martin Milmore’s own Coppenhagen angel, a female figure holding a bronze trumpet in one hand and raising her other hand, created for Mount Auburn Cemetery in 1872 (see Plate 5).26 The trumpet will sound on Resurrection Day. French’s angel, however, is far more decorative and majestic, an updated angel. It represents a great stylistic stride as well from their mentor Thomas Ball’s stone Jonas Chickering Memorial in the same cemetery, which shows a boyish Angel of Death Lifting a Veil from the Eyes of Faith (1872).27

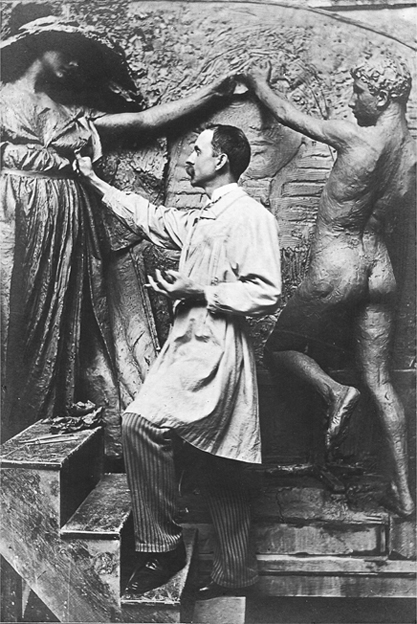

A later photograph of French at work in his New York studio on the full-size clay model for the Milmore monument, eight feet wide and nearly eight feet high (Figure 42), gives us a fascinating picture of its evolution. The monument occupied most of one end of his studio. The partly defined head of a sphinx in low relief can now be seen, the unfinished carving on which the sculptor has been intently working. The picture shows that French first modeled the youth in the nude, presumably from sessions with a life model, and added the figure’s work apron and tightly fitting leggings only later on. The youth’s body is taking form as vital and healthy, and he now stands taller on his straight right leg than in the maquette, more nearly the same height as the majestic angel. The sculptor’s arm is drawn back, mallet in hand, ready to strike his poised chisel; he is immersed in his work, concentrating his mind as well as his physical being on the task. While his head remains in profile, his body is turned more fully away from the viewer in contrast to the angel’s frontal form. The two figures’ arms no longer form a straight line but join in a graceful balletic gesture, as if they are participating in an elegant, stylized dance of life and death. A cloak sweeps across the formerly uncovered head of the angel, casting its face in shadow; its face is also more fully in profile with eyes open but looking into the distance rather than directly at the youth. The drapery, which hung straight down in the maquette, is now a complex play of sweeping curved forms, spread out in a decorative, almost abstract, play of lines and shapes. French might have used a live model (Figure 43) as well as a lay figure, a jointed model that can be posed in any attitude (as seen at left of the memorial in Figure 44), to capture the play of the drapery.

Figure 42.

Daniel Chester French at work on the Milmore Memorial in his New York studio. Courtesy of the Chesterwood Archives, Chapin Library, Williams College, gift of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Chesterwood, a National Trust Historic Site in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Figure 43.

A model poses in Daniel Chester French’s studio. Undated photograph. Courtesy of the Chesterwood Archives, Chapin Library, Williams College, gift of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Chesterwood, a National Trust Historic Site in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Figure 44 also shows one important feature of the sculpture’s design that was cut off in the best-known, more tightly focused picture of French at work: the angel originally held a horn or trumpet, a common attribute of the angel of the resurrection in cemetery sculpture such as Milmore’s Coppenhagen angel. This horn was later tellingly replaced by poppies, which shift the references from Christian iconography to time-honored equations of sleep (poppies are the source of the narcotic opium) and death. For period audiences the poppies might have summoned up themes popular among the British Pre-Raphaelite painters, including especially Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix (1872), in which a dove brings a poppy of sleep to the artist’s languid, dying wife. John Everett Millais’s dead Ophelia also carries one blood-red poppy. French had visited the studios of such British artists as Sir Frederick Leighton, Edward Burne-Jones, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema in London on his 1886 European trip and was familiar with these themes.28

Figure 44.

Daniel Chester French’s New York studio, including his Gallaudet Memorial at left and Milmore Memorial. At this stage, the angel holds a trumpet. Courtesy of the Chesterwood Archives, Chapin Library, Williams College, gift of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Chesterwood, a National Trust Historic Site in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

French’s angel represents a gentle guide rather than a grim or violent personification of Death. It was compared and contrasted with such well-known images as George Frederic Watts’s Love and Death (Figure 45), which was mentioned by a number of critics, and the somber Angel of Death in Elihu Vedder’s illustrations for Khalil Gibran’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Both of these offered humanized depictions of death that were gentler than the skeletons and cadavers found in art of past centuries.29 In Watts’s well-known painting, which exists in multiple versions, a small boy representing winged Love tries in vain to stop the approach of a looming white-draped Death. Love’s fragile wings are crushed as he struggles to hold off the inevitable. Death tramples the roses in its path as it advances, yet leaves a living dove untouched at lower right. Vedder included a moody “Angel of the Darker Drink” in the illustrations he composed for the Rubáiyát, which achieved unparalleled success, its first edition selling out in Boston in 1884. His turbaned male angel garbed in white offers a cup of death to a beautiful young woman who cannot resist its force. The angel, with outstretched wings, turns his head to avoid the swooning figure’s eyes, but he may soon fold her in his arms as she collapses. Vedder’s image fuses Christian references to resurrection and wine with the Persian poet’s verses.30 William Wetmore Story’s highly personal Angel of Grief performed her prostration with an all-too-human sense of despair and loss and is of a quite different register from these and from French’s comforting escort. Yet all share a common function.

Figure 45.

George Frederic Watts, Love and Death, 1877–87. Oil on canvas, 97 × 46 in. Tate Britain, London. Courtesy of Tate Images.

French exhibited his Milmore Memorial in fine-arts settings under the title The Angel of Death and the Sculptor but referred to it most often in correspondence simply as “Death and the Sculptor.” Robert Kastenbaum, a scholar of the ways in which societies deal with death, has noted that personifications can help individuals and societies to cope with death by “objectifying an abstract concept that is difficult to grasp with the mind alone … expressing feelings that are difficult to put into words…[and] serving as a coin of communication among people who otherwise would hesitate to share their feelings.” They provide symbols, he added, “that can be repeatedly reshaped to stimulate emotional healing and cognitive integration.”31 In a letter to sculptor-critic F. Wellington Ruckstuhl, French expressed similar ideas about visual consolation, offering an open-ended explanation for his memorial:

My message, if I had any to give, was to protest against the usual representation of Death as the horrible, gruesome preserve that it has been represented to be ever since the Christian era. It has always seemed to me that this was in direct opposition to the teachings of Christ which represent the next world as a vast improvement over this one. “That men may be content to live, the Gods have hidden from them that it is sweet to die” was the utterance of a Greek philosopher.32

French used the form of an angel to accomplish his goal. During the late nineteenth century angels moved from biblical and religious contexts into the mass culture of the industrial world, as writer Paul Gardella has explained. They proliferated in parks as well as cemeteries and public war memorials, prints, and fictional accounts. Angels appeared, for example, in the writings of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Herman Melville, the spiritualist best-seller Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman, and in the lithographs of Currier and Ives, such as The Angels of the Battlefield, which shows a winged figure coming to guard the spirit of a dying soldier.33 They were mentioned in consolation literature, epitaphs, and in the Protestant hymns developed in the nineteenth century.34 The Gates Ajar (1868), Phelps’s immensely popular serialized fictional dialogue about the afterlife, identified “any servant of God” as an angel in this critical time. Consolation literature like George Wood’s The Gates Wide Open, or Scenes in Another World (1870) and Letters from Heaven (1887) talked in terms of personal guardian angels assigned to each of those who passed away, guiding them to a pleasant new home in heaven, similar to the one on earth. A bronze Angel of the Waters by sculptor Emma Stebbins was commissioned for a fountain in New York’s Central Park in the 1870s and became much beloved. French would go on to be the greatest American master of angelic sculpture, making at least ten major sculptures. As Gardella notes, artists like French used angels in the late nineteenth century to invoke “spiritual power without dogma, contributing to a new realm of nondenominational religion.”35

While the Milmore Memorial could be interpreted as less focused on an interior questioning and self-reflection than the Adams Memorial, it did suggest universal themes with much wider resonance than the specific story of the three Milmore sculptor-brothers. Americans, familiar with such publications as John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and with Thomas Cole’s allegorical paintings, often saw life as a kind of journey. The Milmore angel can be seen as arriving to lead the young sculptor on the final leg of that journey, sooner than expected. Similarly, a guardian angel watched over the life of one man, from childhood to old age, in Cole’s celebrated four-painting series The Voyage of Life (1840). Angels surrounded the Virgin Mary or the risen Jesus in myriad ascension scenes from the Renaissance and baroque periods, and they also take George Washington aloft in a well-known American print and in the apotheosis scene in the dome of the U.S. Capitol. Viewers with different understandings of religious faith thus might bring to the Milmore sculpture their own expectations and interpretations.36

Eventually, French worked out the costume of the sculptor, which had been suggested in his early maquette. The young man wears an apron, tight leggings, a sleeveless shirt, and soft slippers. The final figure is not a gentleman sculptor but a youthful laborer more akin to an idealized artisan or quarry worker. Yet his deep concentration and aura of internal serenity suggest that he possesses a native genius and authentic, natural nobility. In this way, he seems a close descendant of a variety of figures of “primitive” people with a Rousseauean spirit deemed to be superior to the academically trained, overcultivated, and well-to-do. One close example is Jules Joseph Lefebvre’s Young Painter Painting a Greek Mask (1865), which shows a Greek youth, also facing away from the viewer with one leg lifted on a bench, as he focuses with almost childlike intensity on painting a theatrical mask (Figure 46). That lithe figure shares a lack of awareness of his observer. Lefebvre, a teacher at the Académie Julian, where many Americans trained, stressed to his students a need for precision in life drawing and painted many beautiful nude figures. He had just won the grand prize at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris and was highly celebrated at the time French was creating his Milmore Memorial.37 Images such as these suggested the “natural” talent and creative vigor of youth in the production of art.

Figure 46.

Jules-Joseph Lefebvre, Young Painter Painting a Greek Mask, 1865. Oil on canvas, 13 × 7.9 in. Photo: René-Gabriel Ojèda. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes, France. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Accounts of Martin Milmore’s career had often talked more about the “immense amount of labor” involved in projects like his colossal Sphinx for Mount Auburn Cemetery or the grand Boston Common soldiers’ monument than of his aesthetic achievements. “No artist works harder or longer every day than Milmore,” said one newspaper report about the expatriate community in Italy.38 The sculptor in the Milmore Memorial is thus shown as an older-style artisan, carving hard stone, presumably marble or limestone, instead of fashioning a clay model with his fingers for future casting in bronze in the Beaux-Arts style. Those who worked hard in life and took pride in their achievements might see themselves in the figure of the sculptor. While the Adams Memorial might be viewed as more about the head than the body or heart, this sculpture could speak of the real exigencies and pleasures of creative labor. Death becomes a rest from a life filled with work. A number of turn-of-the-century cemetery memorials sounded this theme, as for example Karl Bitter’s later Henry Villard monument (1904) in New York’s Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, dedicated to a railroad financier whose capital employed many workers, and Charles Niehaus’s Drake Memorial in Woodlawn Cemetery, Titusville, Pennsylvania. They all question the meaning of life’s labors, creativity, and the surcease of work.

The horizontal ledge upon which the youth rests his knee, together with the vertical edges of the relief and the curving top line, frame the low-relief sphinx that appears within the larger tableau. While surviving photos show that the head of the sphinx faced forward in an earlier design, it is seen in profile in the final iteration (see Plate 2), behind and between the angel and the youth. Their faces are also in profile, and the creature becomes the third major element in the sculptural grouping, uniting the whole. French said later that the choice of a sphinx such as Milmore had made for Jacob Bigelow was a “coincidence.” He insisted that he added the sphinx solely to introduce an element of mystery, “in this case the mystery of life and death.”39 But his comment seems disingenuous. The Bigelow sphinx was by far the most famous emanation of this Egyptian form in the American landscape of death. And French’s own diary entry documents his early personal awareness of the sphinx in Mount Auburn Cemetery, a major Civil War monument that lingered in viewers’ minds.

French referred at least twice in letters to the fact that Milmore had made the sphinx as a “war memorial” or “soldiers monument.” While his Milmore monument clearly contains specific references to the Milmore brothers’ lives, therefore, it also must be remembered that it was created at a time of renewed recollections of the Civil War and should be interpreted in that context as well. In 1888, the year French took on the commission, the nation marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the war with large-scale veterans’ reunions and many other events and publications. A popular series of war reminiscences in Century magazine from 1884 to 1887, for example, had become the basis for a four-volume collection, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Magazines specifically devoted to the war, such as Confederate Veteran (1893–1932), reached their peak circulation at the turn of the century. Battlefield parks were being developed, and large numbers of regimental monuments were erected by veterans groups and by groups formed by the sons and daughters of veterans to mark the passing of the war generation.40

Figure 47.

Daniel Chester French, Death and Youth, Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul, St. Paul’s School, Concord, New Hampshire, 1929. Marble group. Courtesy of the Chesterwood Archives, Chapin Library, Williams College, gift of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Chesterwood, a National Trust Historic Site in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Against this backdrop, the sculpted youth whose life is shown ending prematurely after giving his all to his labors might be a stand-in for the many young men who died during the war as well as for the bodies of the Milmore brothers buried at the Roxbury gravesite. Its essential theme is life cut off, for which an extensive iconography existed, seen in endless repetitions in American cemeteries of broken columns, rose petals dropped to the ground, drooping flowers, and sleeping lambs. French would return to this theme much later in his moving war memorial, Death and Youth, a marble group depicting an angel supporting a dying soldier in the chapel at St. Paul’s School, Concord, New Hampshire. Dedicated in 1929, it paid tribute to students who had died in World War I. French explained the Concord sculpture (Figure 47) in terms like those used for his Milmore Memorial, saying that he had intended it to counter ideas about the terrors of death, and adding, “It is this that I should like to have my group convey;—that the angel who is taking the youth in her protecting arms is ushering him into a higher and better life.”41 During the Civil War, when soldiers died far from home and without the presence of ministers, families were sometimes reassured by letters from witnesses confirming that their sons or husbands or fathers had faced death peacefully, with self-control and with a confident patriotic purpose.42 A sculpture such as French’s Milmore group could be another form of consolation for those who had lost young ones in the war after a life of duty and sacrifice. The death it portrays is quiet and beautiful, not violent, retaining a sense of wonder and mystery.

In choosing the sphinx, French selected a symbol that was both specific and universal, and one that resonated with the times. A newspaper sketch shows that the artist completed the hybrid creature last, after adding clothing to his youth.43 French’s sphinx for the Milmore Memorial wears a royal head cloth, and the sculptor is shown at work defining its crown. In his published description of the memorial, Lorado Taft also suggested that the sphinx was introduced as a fortuitous afterthought, noting that the figure of the young sculptor was not meant to be a portrait of Milmore but a concept, and arguing that the same was true of the sphinx, which can be a multivalent symbol.44 A sphinx, of course, summoned up thoughts of ancient Egyptian pyramids, with their emphasis on guarding the bodies and souls of the dead. Egyptian culture and its eternal mysteries were of current interest after the obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle arrived in New York in 1881, covered with indecipherable hieroglyphics; Egyptian themes would be sounded on the midway as well at the 1893 world’s fair, suggesting their expanding popularity. In the 1880s and 1890s, the word sphinx was widely used in the media and even in the advertising world for any object (or person) that conceals secrets. For example, one political cartoon showed U.S. Senator George Hoar as “ ‘uncommitted,’ solid as a sphinx”; another described prominent public figure James Blaine as “the political sphinx of the republican party. The riddle is: what does he mean to do—to run, to decline to run, to withdraw.” “Sphinx’s Eyes” was an optical illusion used in advertisements. Octave Feuillet’s play Sphinx was presented in New York and then Boston after a run in Paris. A Sphinx senior society was founded in 1886 at Dartmouth, where both French’s father and executor Richardson were alumni. Elite tourists like Henry and Marian Adams as well as orientalist artists had enjoyed cruises down the Nile to see the original, and painters such as Vedder and later John Singer Sargent included the sphinx in their productions. The Adams Memorial was often later referred to as a “sphinx” because of its indecipherability.45

The sphinx could become a metaphor for the way a work of art conceals the “intimate thought” it embodies and the ways it can help unlock life’s riddles, notes author Scott C. Alan, who calls the sphinx the “mother of all symbols.”46 It has long been a popular assumption that at the last moment of life, the mortally ill departing this earth have a “privileged insight into the meaning of life and mystery of death.”47 Is it that Milmore, carving the sphinx as he seeks to puzzle out life’s ultimate riddle, actually sees the heavy three-dimensional angel that appears before him in the sculpture? Or does his angelic visitor appear only in his mind’s eye as at the last breath, standing before the sphinx, the famous oracle, he gets a glimpse of the true understanding of the cycles of life and death, faith and hope? A perfect rush of insight about the wholeness and interconnectedness of the universe, heaven and earth, may flood his mind and spirit—a tantalizing glimpse of a higher consciousness for which Gilded Age visitors yearned.

In October 1891 French returned to Paris, this time to have his Milmore tableau cast in bronze and to begin a three-foot model of his colossal figure of the Republic for the upcoming Chicago world’s fair.48 He took a studio not far from the Arc de Triomphe and next to the atelier of French sculptor Emmanuel Frémiet, and made final modifications there.49 On January 5, 1892, French wrote his brother jubilantly that more than one hundred people had come to see the final plaster of the Milmore monument during a “big reception” at his studio. “Some French sculptors, Frémiet among them, came before the reception-day, and really, William, it looks as if I had done tolerably well this time. [American sculptor Paul Wayland] Bartlett says Frémiet almost never praises anything, and he said some really civil things about my relief.”50

French contracted with the E. Gruet Jeune Foundry in Paris to make the bronze cast, which was not completed, however, until after his return to the United States to prepare for the world’s fair. Thus he was not in France to personally approve the cast or to see his work exhibited, first at the original Salon on the Champs-Élysées and then at the smaller new Salon on the Champ-de-Mars, which was seen as more welcoming to foreign artists; there he was awarded a third-class medal, and he reported that “the Paris papers are speaking respectfully of the Milmore.”51 Thomas Ball kindly wrote that he too had seen and admired “your beautiful monument to Martin Milmore” in Paris.52

This was a time of terrific excitement for French, a famously soft-spoken man with a patient demeanor, as he worked with a production team for the Chicago fair. French wrote his brother on February 3, 1893, that successful exhibitions of the plaster Milmore relief had also been arranged at the Society of American Artists and Architectural League shows in New York. “The exhibition of the Milmore here was a ten stroke. The Society Am. Artists had it first then the Architectural League … gave it the place of honor. The newspapers have puffed it and the Century [magazine] is to picture it in March or April and I am likely to be impoverished giving away photographs.”53

French also showed the plaster at the 1893 world’s fair, where it attracted considerable attention, while the original was finally quietly installed in August of that same year in the Forest Hills Cemetery to serve its original function as a private memorial.54 The bronze for the cemetery, inscribed with the artist’s name “D C French” and the year 1891, was placed in a stone setting designed by C. Howard Walker, the adequacy of which became a long-standing source of contention between the estate and the sculptor. It is clear that French, busy with his grand productions for the world’s fair, did not work closely with Walker, as Saint-Gaudens had with White, and that the setting was more of an afterthought than an integral part of the design. French admitted later there was little money left to devote to it after the casting and shipping of the bronze. The gravesite became a less visible emanation of the memorial design, which was better known in public fine-art displays. Fragments of correspondence that survive suggest the setting became a significant issue of tension between French and the estate immediately after the installation, when French apparently even considered withdrawing the original bronze. A resolution was finally reached, however, and there was no more mention about discontent with the setting until about 1914, when a new exchange with the family occurred about the need to repair and maintain it.55

Following delicate negotiations with James Bailey Richardson, co-executor of the estate, plaster replicas were approved for placement in major American museums in Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, and Philadelphia, and discussions were held about sending one to a European institution. A marble version was later created for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.56 The sculpture, quickly entering the realm of fine art, helped to cement French’s emerging career. It would be interpreted over time as being both about the Milmores’ lives and about ideas extending beyond the Milmore brothers’ achievements.