In 1901 an anarchist named Leon Czolgoz walked up to President William McKinley at a reception in the Temple of Music at the Buffalo world’s fair, his hand wrapped in a cloth to conceal the pistol he carried. He fired two shots point-blank, striking the president’s chest and abdomen. While at first it appeared that McKinley might survive the wounds, his condition worsened after emergency surgery, and he died a week later, at 2:15 a.m. on September 14. As a shocked nation awoke to the news, a Danish immigrant named Eduard L. A. Pausch (1856–1931) was summoned to take a plaster impression of McKinley’s lifeless face, creating a historical record of his features. Pausch was a modeler of cemetery memorials and portrait monuments who had worked for a decade with a New England granite company. He had studied with several minor sculptors, including Karl Gerhardt (1853–1940), a Paris-trained artist who had made the death mask of General Ulysses S. Grant.1 In Buffalo, Pausch thus offered his expert services to McKinley’s retinue and was paid $1,200 to make the plaster mask, which he spent a month perfecting in his studio, placing it in a safety deposit vault each evening for security’s sake.2 Based on his personal measurements of the president’s head, he created not just a cast of his face but an entire head, which weighed twenty-five pounds (Figure 59). It was sent to the Smithsonian Institution, which already held plaster impressions of Abraham Lincoln’s face. Due to the omnipresence of photography in the new age of Kodakers and the increasing ease of recording a person’s appearance, interest in the death-mask format would wane in the twentieth century. But Pausch took great pride in his achievement, which he hoped would dramatically advance his career.3 When possible, sculptors used masks and measurements of famous men as the basis for scientifically accurate likenesses in portrait statues. Augustus Saint-Gaudens had considered an 1860 life mask of Lincoln, made by Leonard Wells Volk, to be so important that he joined a group of thirty-three elite citizens who purchased it as a gift to the U.S. government, selling bronze casts of the original to fund the donation. Saint-Gaudens used the cast as well as photographs as a basis for his highly regarded monument to Lincoln in Chicago, and he used another of James Garfield in making his Garfield Memorial in Philadelphia.4

Figure 59.

Eduard Pausch, Death mask of President William McKinley, 1901. Division of Political History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Pausch went on to make a bronze monument of McKinley in Reading, Pennsylvania, and a bust of McKinley for the Philadelphia post office, which he could claim to be authentic in appearance. With his combination of technical skills and studio training, he described himself as a “figure and ornamental sculptor” and worked across the blurry line that distinguished a skilled artisan from high-art sculptors such as Saint-Gaudens or Daniel Chester French, who were sought after for the most expensive and visible public commissions. While Pausch aspired to gain monumental commissions, he never matched the more famous sculptors’ skills nor displayed his work at fine-arts exhibitions such as the National Academy of Design or National Sculpture Society in New York. Rather, he remained an active participant in the commerce of the granite, monument, and deathways industries, where notions of originality and genius were often less important than issues of function, customer satisfaction, and cost. In a letter sent a few years later to Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Edwin Elwell, who was collecting information about contemporary American sculptors, Pausch noted that he had had a “plain” career, built on “hard study and work.” An early commission for a cemetery monument “brought me in that channel or class of work,” he explained.5 Pausch’s ideas about cemetery memorials as both business and art, demonstrations of artistic talent and objects suitable for multiple reproduction, differed, if sometimes only in degree, from those of Saint-Gaudens, French, and William Wetmore Story. Over time, his mask became one source for a number of honorific public sculptures of President McKinley. His angels and crosses for cemeteries also multiplied. Sculpture in multiples constituted an important part of the American system of memorialization.

Figure 60.

President McKinley’s casket is borne up the steps of the U.S. Capitol as cameramen at left film the scene. Photo from Murat Halstead, The Illustrious Life of William McKinley, Our Martyred President, 1901, p. 400.

The old modes of memory work, like Pausch’s death mask, intersected with more modern methods at the time of McKinley’s assassination, as mass-media publications rushed photographic images surrounding the president’s death to print, and Thomas Edison’s company recorded the grand rituals around his funeral and subsequent interment with a new technology: motion picture film. Due to advances in printing and transportation systems, the grieving public all across the country was able to view photographic images of memorial events with a greater immediacy and volume than ever before. Artists’ illustrations, not photographs, had been most widely circulated after the deaths of Lincoln and Garfield. Now, photos of McKinley’s body being borne up the steps of the Capitol (Figure 60) and lying in state in the White House, of memorial services decorated with elaborate floral bouquets, and of the holding vault where the president’s corpse was placed were among the many visual aspects of his passing that could quickly be featured in daily newspapers and national photogravure magazines. This was made possible by the halftone process of mechanical reproduction, which since the late 1880s had enabled photographs to be included alongside text on printed pages, and also by the national distribution systems that had flowered. The steady expansion of the steam-powered railroad and shipping lines worked a transportation revolution that permitted periodicals as well as other products to be shipped across vast geographic distances in ever-shortening times.

With the rise of the motion picture, the multiple funeral processions were also captured by the Edison Company’s cameras—first in Buffalo, where the president died at the Pan-American Exposition; then in Washington, D.C.; and in his hometown of Canton, Ohio, where pallbearers removed his flag-draped casket from a railroad car. Finally, the cameras followed his hearse on its journey to the cemetery. Edison’s cameramen made eleven short films in all of the events surrounding McKinley’s death rites, from a variety of camera angles. At the opening of the twentieth century, these were sold in packages to theaters, which showed them together with other shorts and motion pictures.6

McKinley was treated with considerable respect in death, as an American martyr. One artist’s illustration from the era shows him entering the “Hall of Martyrs” already occupied by Presidents Lincoln and Garfield, guided by allegorical figures depicting the nation’s North and South. Henry Adams’s friend John Hay, who had formerly served as Lincoln’s secretary, delivered a eulogy before the U.S. Congress. A grand mausoleum was built to house McKinley’s remains, an edifice that is still the pride of Canton, Ohio.

His passing certainly represented a unique tragedy of national dimensions. Yet the coincidence of advancing technology, a growing mass media, a more rapid and broad chain of distribution, and an attentive national audience exposed to a new wave of imagery—all observed in the public response to the president’s demise—would have an impact on wider expressions of mourning at the turn of the century. American memorialization was becoming less local and private than before. It was becoming big business. All of these developments—aspects of the increasing connectedness of things—added another element, an element of risk, to the selection of funerary memorials. Issues of morality and propriety of behavior, of good taste, and even of the soundness of financial decisions made at this time of private grief and loss became more visible—and more subject to potential critique or appropriation in an era of easy communication.

While elite patrons, museums, and expert critics came to embrace figurative bronze funerary monuments as important works of high art, appropriate for the museum as well as the cemetery, the greater world around them was changing. Decisions about memorialization were more readily susceptible to expressions of public judgment separate from specialist opinion. Readers accustomed to the strategies of mass-media publishing and advertising, and audiences familiar with the spectacle of motion pictures and vaudeville were trained in new modes of viewing and consumption involving curiosity and skepticism. The rapidly growing American press had adopted aggressive strategies for building circulation, featuring gossip and “personals,” celebrity interviews, and many human interest stories.7 In the more questioning, less polite discourse of the vernacular culture, humor and the grotesque were devices used to puncture the rich and the pompous. The rising commercial culture also worked a change on attitudes about what constituted value in modern times and how to avoid the shame of an overly sentimental, emotional, or grandiose response to death. The new monuments were not always viewed with the reverence intended. Instead, rude or romanticized counternarratives could arise, resisting and even inverting the patrons’ and artists’ goals of erecting an enduring legacy of restrained nobility in bronze and stone.

In a graveyard—which was a quasi-public place—how could a family ensure that its monument would attract dignified respect and not be subject to derision? Mistakes of cost expended and taste misjudged could subject the patron and the deceased to ridicule. This was particularly true for the wealthy, whose missteps—especially attempts at grandeur—were special fodder for a pitiless press, which loved to lampoon the pomposity of the rich in this era of rapid economic growth and frenzied speculation.

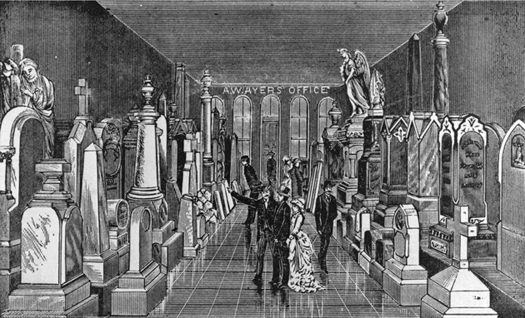

At the turn of the century, monument making was a multimillion-dollar industry. Purchasers, presented with an expanding array of choices (Figure 61), needed to determine which decisions would be rewarded by an enduring tribute and which might lead down the path of public shame. Shame involved a denial of honor and dignity at just the moment when these goals seem most poignant and important after a personal loss. Shame is not much discussed in the twenty-first century (in fact, some have talked about the death of shame), but it was a crucial concern for patrons at the turn of the twentieth century. A strong desire to avoid errors of taste influenced the course of vernacular and fine-art memorialization in cemeteries. Salesmen and artists alike exploited these concerns in their transactions with prospective patrons, who wanted to do the right thing for their loved ones.

Just after the year 1900, selection of a simple grave marker was no longer a decision necessarily made in a face-to-face encounter with a nearby stone dealer who might carve the monument locally. Rather, suppliers ranged from import companies to large domestic monument firms, which were associated with quarries in places like Westerly, Rhode Island, and Barre, Vermont, to the mass-produced inventory advertised in Sears Roebuck & Co. mail-order catalogues, or a more selective, customized array of crosses, ledger monuments, and mausoleums offered by Tiffany Studios. All of these spoke in terms of high-quality memorial “art,” but many of them offered stock designs such as angel number T23 and lettering no. M44 to choose from with examples pictured in catalogues or displayed in showrooms.

Figure 61.

A. W. Ayers. Trade card for monuments and mantels, Elmira, New York, ca. 1883. Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur, Delaware.

Well-to-do or high-status individuals like William Vanderbilt II often chose grand sarcophagi or the security of the mausoleum, especially after thieves stole department store mogul A. T. Stewart’s corpse from a Manhattan churchyard in November 1878. “The Grave-Yard Robbery” case was front-page news for thirteen straight days after its discovery, and the search for the “Ghouls” or “Resurrectionists” who took Stewart’s body became a matter of wide public lore.8 These elite patrons favored classicizing, medieval, or Egyptian styles for their mausoleums, sometimes selecting the same architects and contractors who had created their homes in life. Or they selected customized stone monuments or figurative sculptures in stone or bronze that afforded them a greater individual identity than the less privileged. Their monuments were on bigger lots, often more prominently placed, adding to a sense of class stratification in the cemetery. But with any of these, wealthy patrons sometimes unintentionally became the butt of public humor. In their book The Gilded Age, Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner had punctured the greed and pomposity of this period of vast new wealth; they lampooned the years after the Civil War as an era when a thin layer of gold veiled a society characterized by materialism, inequality, waves of immigration, and the drudgery of industrial labor. In the cemetery, excess of cost, excess in the amount of stone piled up (sometimes to gigantesque heights), or excess of sentimentality in the epitaph or figure could cross the fine line from sparking tribute to inspiring jokes. Monument firms concerned with profit margins encouraged patrons to use the greatest possible amount of stone, as if more stone signaled greater virtue on the part of the deceased. This seems to have been true in the case of Hope, Faith and Charity, a colossal monument constructed by prosperous businessman William Hoyt in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery after the death of his daughter and her three children in a theater fire in 1903.9 Or consider the towering Corinthian column in the same cemetery erected to George Pullman, inventor of the Pullman sleeping car, whose body was placed in an elaborate concrete bunker beneath to ensure that it was never vandalized or stolen. Pullman’s family had feared retaliation after a bitter 1894 strike over workers’ wages and rents. But the excessive security around his monument became the topic of ironic commentary in guidebooks and newspaper accounts from the early days.10 High security also was required around the graves of such moguls as Jay Gould, who was entombed in an Ionic temple on a large swathe of land in New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery as a crowd of idlers looked on, making “irreverent chatter.”11 Newspapers reported that Gould was carried from his home, also surrounded by onlookers, to the cemetery in an “extremely plain hearse” accompanied by eight carriages, and his mausoleum bears no name on the outside, to avoid attracting the wrong sort of attention. Similarly, the magnificent mausoleum in the form of a classical temple built by the Stanford family in California after the death of their son drew ridicule as well as respect, with the Los Angeles Times commenting at one point that it was a monument not only to “a very commonplace youth” and the grief of his parents, but also to “the vanity which prompted them to believe that they could render a name immortal that represented but a few years of a life interesting to them alone.”12 The Adams Memorial itself was sometimes dubbed a monument to “despair” or more commonly “Grief,” in the media, breaching Henry Adams’s desires for reverent contemplation and privacy.

Newspapers always questioned the equity of memorial expenditures, noting, for example, the oddity of the situation when Cleveland millionaire H. A. Lozier left $2,500 in his will for his own tombstone while directing that a $200 monument be erected over his mother’s grave.13 At the same time art critics like Mariana Van Rensselaer counseled restraint, warning against cemeteries full of “big monuments, bad in design, that simply shout out their names with a crude and vulgar voice.”14 Saint-Gaudens himself wrote later in an urban planning report about modern cemeteries: “[T]here is certainly nothing that suffers more from vulgarity, ignorance and pretentiousness on the one side, and grasping unscrupulousness on the other.… [T]he eye and the feelings are constantly shocked by the monstrosities which dominate in all modern cemeteries.”15

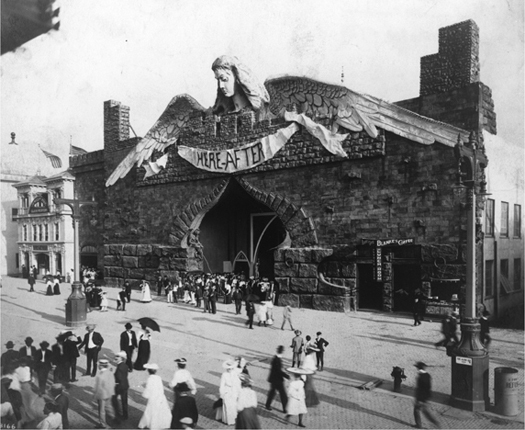

By the turn of the century, after decades of debate about science, religion, and human evolution had tempered the literalism of at least some Americans’ beliefs in heaven and hell, humor about death and the hereafter was permitted in certain circumstances. For example, Hereafter was the name of an entertainment pavilion on the Pike at the St. Louis world’s fair in 1904, loosely based on Dante’s Inferno (Figure 62).16 Visitors who paid twenty-five cents could cross the River of Death and travel to Hades and the underground throne room of Satan himself, experiencing a variety of mechanical effects, before heading to the Gates of Paradise and another exhibit about Creation.

Public figures like Mark Twain frequently jested about funerals and neglected tombstones. Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn attend their own funeral, listening to eulogies before revealing themselves, and they and other characters visit cemeteries and make sundry graveyard jokes.17 The nagging wife’s tombstone and other gravestone references were a stock feature of vaudeville at the turn of the century.18 Mentions in period newspapers of the word “tombstone” are often connected with jokes or puns, such as humorous epithets placed on such stones or imagined by writers. One example repeated in the New York Times was about a man named Mud: “Here lies Matthew Mud / Death did him no hurt / When alive he was Mud and now dead, he is dirt.”19 Actual lengthy inscriptions on grave monuments were viewed as outdated, since other means such as newspaper obituaries had in essence replaced the need to outline the character of the deceased in stone; longer or more sentimental epithets were thus often mocked with doggerel.20

Scholar Michael Leja in his book Looking Askance has shown how the public in the years around 1900 was prepared for trickery in its viewing habits. Americans had become attuned to the showmanship of P. T. Barnum, bearded ladies exhibited as curiosities, and a climate of confidence men and hucksterism. In addition to exposure to spirit photos, deceptive advertising images, and newspaper sensationalism, they had witnessed scientific revelations of the previously invisible, such as X-ray technology. How could they then judge the visual culture that surrounded them at the turn of the century? “To function successfully, even to survive, every inhabitant of the modern city, every target of competitive marketing, every participant in the new mass culture, every beneficiary of modern science and technology, every believer in spiritual realms had to process visual experiences with some measure of suspicion, caution, and guile,” Leja wrote.21 Amid this fluid new environment, monument dealers, undertakers, sculptors, and cemetery patrons also concerned themselves with questions of duplicity, shame, and its avoidance in memorialization. In fact, an aggressive salesmanship of fear arose in these uncertain times. Monument company salesmen played on tombstone patrons’ anxieties about expending the correct amount of money to erect appropriate grave markers and choosing the correct design and materials. Questions about propriety, personal values, and gullibility were in the forefront. In a discussion with writer-editor Norman Hapgood in 1906 revisiting the “horrible desecration” of American cemeteries, Saint-Gaudens complained, “You know it is awful, the monumental granite men lay around like sharks,” ready to persuade the emotionally vulnerable.22

Figure 62.

On the Pike: Hereafter, Official Photographic Company, 1904. Photo of world’s fair midway attraction. Missouri History Museum, St. Louis.

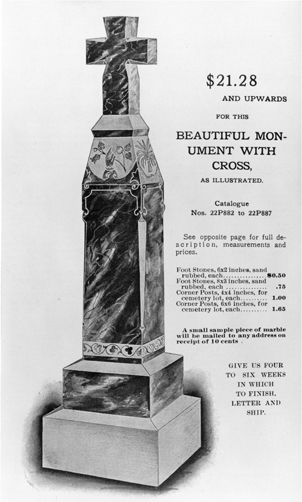

Both Sears and Tiffany addressed these concerns as they developed national advertising and distribution campaigns. Sears appealed to the most primal fear, the fear of being cheated at a time of special susceptibility. By 1900 Sears had established a Department of Memorial Art, and by 1902 it offered a special mail-order catalogue for tombstones and monuments. The catalogue noted that the purchase of a gravestone was a “perhaps once in a life time” decision, for which few people are well prepared.23 “[I]t is a peculiar line of goods, a line of goods on which the intending buyer is not so likely to question the matter of price” and “is inclined to be liberal” about cost when visiting a local dealer who charges an inflated rate, it said. Sears promised to deliver top value and good materials, hand cut by “expert artisans,” at half the usual cost. It said it could deliver high-quality products more cheaply because of its large factory and the quantity it was able to sell, citing the cost-efficiency of its bulk sales, departmentalized lines of manufacturing combined with mail-order distribution, and the modesty of the company’s profit. Customers could have tombstones shipped by rail anywhere in the country within four to six weeks for a five-dollar deposit, and if a monument did not prove satisfactory, they could ship it back at no cost. This enabled the company to market its work to far-flung customers previously limited to local markets, at a time when a third of the U.S. population lived west of the Mississippi. Examples pictured in the catalogue include the $18.40 Father Mother stone, with space for other appropriate lettering at 2 1/2 cents per letter in a certain style. Or the $21.28 Beautiful Monument with a Cross (Figure 63), or The Most Magnificent Monument, which “can be owned by you at $90 and upwards, according to size.” Clients could write their own inscriptions or choose among the most popular, such as “God’s finger touched him, and he slept” (75 cents) or “Gone but not forgotten” (47 cents), to cite some of the shortest ones, each classified by catalogue number.24

Figure 63.

Advertisement for a Sears grave monument. Sears Roebuck & Co., Tombstones and Monuments (Chicago: Sears Roebuck & Co., 1902).

Sears applied modern consumer sales methods to win the trust of the public, strategies that worked with other kinds of goods such as sewing machines, garden tools, or watches. Its plainspoken ads emphasized that no trickery was used (such as applying acid to carve a stone) and promised that the company would control the quality of stone from the Acme Blue Marble Quarries of Vermont. A sample piece of veined marble could be ordered in advance for a few pennies. To assuage the concerns of prospective clients who feared being duped by slick urban entrepreneurs, the Sears catalogue included reassuring testimonials from satisfied customers about the enduring handsomeness of monuments and the reliability of their delivery. Among these printed testimonials, G. W. Stuller, for example, mentioned that his stone, on arrival, was just “as represented in [the] catalogue.” Sadie B. Hubbard commented that it is “one of the best I ever saw for the money. The quality being, I consider, tip top.”25 The Sears sales pitch took advantage of another worry: lawsuits that were sometimes described in newspapers. Heirs sometimes brought legal actions complaining that too much was being spent on a monument, that such an expenditure went beyond reason and was a form of immorality. In a Long Island, New York, court in 1897, a family member challenged the outlay of more than $1,000 for the erection of a grave marker for David C. Smith. Niece Julia Betts argued “that the monument was a piece of extravagance” and said she would “try to show that one costing not more than one-third of the amount would have been good enough.”26 For Americans like Betts, the purchase of an acceptable monument at a fair price was a matter of funerary virtue and of fairness to survivors whose inheritances could be affected. Sears catalogues did not urge people to seek originality in style but, rather, stressed functionality, durability, and avoidance of fraud and derision.

Figure 64.

Townsend, Townsend & Co. advertisement, “Italian Statuary,” 1892. Monumental News.

Other choices for those willing to spend a bit more money on memorials included finished Italian imports, often purchased through a middleman such as a regional dealer, that promised a degree of aesthetic security. Townsend, Townsend & Co. guaranteed in its 1901 ads that each of its statues imported from Italy would be “Works of Art” (Figure 64). American granite quarries developed strong presences in the marketplace at the end of the nineteenth century, and after 1900 U.S. quarries, foundries, and monument manufacturers increasingly hawked their grave sculptures nationally as being in the highest artistic taste, offering a blanket of aesthetic security. Charles Bianchi & Sons of Barre, Vermont, for example, pictured one of its stone angels in an advertisement with the headline, “Artistic Monuments and Mausoleums Built for the Connoisseur.”27

Firms like the Smith Granite Company in Westerly, Rhode Island, offered catalogues with stock designs, some prepared by second-tier sculptors such as Eduard Pausch, who had taken the death mask of President McKinley.28 Pausch had worked with the Smith company for ten years after training in his youth with Carl Conrads, an older sculptor who had a long association with another monument firm, New England Granite Works. Many monument companies and quarries developed their own designers, usually men (but occasionally women) who had learned their trade by working with others rather than in any formal academic system. They were sometimes skilled immigrants who had experience as carvers or modelers before their arrival in the United States, but usually they had not had the luxury of studying in a system like the École des Beaux-Arts.29 Their work as “tombstone sculptors” or “monument men” might be exhibited at trade expositions or showrooms rather than fine-arts shows or museums. Monument dealers such as Charles F. Schroeder of Philadelphia moved to more elaborate display methods of their own in later years, when Schroeder installed a large window with elaborate night lighting to attract passersby to its sculpted angels.30 The monument companies fiercely protected their own designs from rival firms.

In contrast to Sears’s high-pitched advertising about reliability and price, the Tiffany firm, best known as a high-end purveyor of jewelry and interior design products, stressed art and a refined elegance in its mortuary line (Figures 65, 66), telling its customers that the period after the loss of a loved one is no time to scrimp on spending. Its ads stated that value lay in a tasteful design, not in the number of dollars paid out or stingily saved. Tiffany’s 1898 catalogue, entitled Out-of-Door Memorials: Mausoleums, Tombs, Headstones, and All Forms of Mortuary Monuments, and other publications explained why the firm had opened a special department related to cemetery memorials. Most memorials to date, often sold in multiples like Sears’s stock, had been “common-place to the last degree” and even “repellent … commercial, crude, uninteresting and completely devoid of all artistic merit,” it declared in its literature. Thus, “people of taste and discernment, from time to time, have come to us, and insisted upon our making designs and supervising their realization,” seeking the twin qualities of beauty of design and durability associated with the Tiffany name.31

Harmony of design and color were related in Tiffany’s sales promotions to qualities of morality and virtue. To raise fears of a shameful result, its catalogue showed illustrations of poor-quality monuments, ill-kempt and surrounded by weeds, and featuring a cluttered array of letters. “[I]f … the design is of no value the memorial will only excite a spirit of derision and criticism, thereby defeating the object of its existence,” it warned. “If on the other hand the design is a work of art the memorial will be a constant source of delight to all, and a sure means of keeping alive the memory of the departed.”32

The 1898 catalogue described an artistic monument as one in which each part of the form is in proper proportion, with the accompanying ornamentation, with the environment, and with a correct choice of color. “Competition of cost should never enter into the matter,” it concluded. “Let the sum to be expended be frankly given,” it counseled, so that the best design can result.33

Figure 65.

“A Tiffany Monolith.” Celtic cross designed by Tiffany studios and dated 1901 for the gravesite of Captain Thomas Mayhew Woodruff Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia. Illustrated in Tiffany Studios, Memorials in Glass and Stone, 1913.

Figure 66.

Out-of-Door Memorials: Mausoleums, Tombs, Headstones, and All Forms of Mortuary Monuments (New York: Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company, 1898).

Despite these statements, today’s viewers might be surprised by the limited range of design elements Tiffany offered as an appropriate antidote to poor funerary design. Louis Comfort Tiffany had long loved the intricate design of Irish carving, and the Tiffany Studios Ecclesiastical Department, under which mortuary materials were placed, featured a variety of small or large Celtic crosses as options for memorials, as well as ledger stones, table monuments, sarcophagi, and monoliths featuring bas-reliefs, decorated with leafy lilies symbolizing resurrection and passionflowers, all at a range of costs. The cross, once avoided by Protestants as a sign of “popery,” was widely adopted in funerary decoration at the turn of the century.34 Tiffany mausoleums also combined mosaics and Tiffany windows. These products demonstrated a careful study of ornamental patterns from a variety of traditions, including Attic grave markers from the classical world, patterns from such sources as Owen Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament (1868), and the Celtic revival, which was spurred by the Arts and Crafts movement and the ideas of John Ruskin and William Morris promoting handmade products to counter the increasingly industrial nature of society.

There were few figurative designs, although some of the rare Tiffany company monoliths are of exceptional quality, ranging from the unusual Egyptian low-relief figure featured on the Edmund Augustus Cummings Monument (before 1900) in Oak Park, Illinois, to the later Coburn Haskell Monolith (1927) in Cleveland and the Spencer Monument (copyrighted 1927–28), a very low-relief angel emerging from an enormous block of white stone at Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C., and the freestanding Benjamin Rose Monument (1904) in Cleveland.35 In the teens, Tiffany bought his own quarry at Cohasset, Massachusetts, so that his memorials could be made of “Tiffany stone.”

Sometimes Tiffany’s worked with major architects, as in the beautiful McKim, Mead & White Twombly Memorial in a classicizing style at Woodlawn Cemetery, where New York’s upper crust were buried and dozens of Tiffany headstones or structures stand. But styles ran the gamut so that we can also find the Webb mausoleum there purchased from Tiffany, which looks like a Victorian gingerbread cake, or the rough-hewn David Belasco mausoleum (1913) in Brooklyn. In 1914 Tiffany published a catalogue focusing solely on mausoleums, many featuring his famous stained-glass windows, often with the River of Life design, a landscape in which a gleaming blue stream wanders through the countryside, often a spring or autumn scene with jewel-like colors, speaking of the cycles of fading life and new life.36

These options eschewed some of the more maudlin appeals to emotion that had dominated nineteenth-century tomb sculpture. And while Sears charged by the letter for its sometimes lengthy gravestone epitaphs, Tiffany suggested that its patrons abandon old-style inscriptions and simply include the family name. The Tiffany catalogue quoted the old saying, “Praises on tombs are trifles vainly spent: a good man’s name is his best monument.” Fulsome eulogies are “transparently absurd,” one of its catalogues said and, even appealing to patriotism, noted, “The word ‘Washington’ on a tomb at Mount Vernon is better than long periods of Latin panegyric.”37

Although most Tiffany monuments were erected in the Northeast, the studio’s memorials can be found in thirty-two states across the country, and Tiffany claimed to be personally responsible for improving America’s cemeteries.38 He said all of his monuments, even if not created by an “artist,” were “original” works created “under the supervision of an artist.” Renderings were prepared for client review, and a polite diplomacy marked the transactions.39 It could take a year or more for a project to be completed. Tiffany’s literature argued for the value of the “original” versus the multiple, for artistic taste and hand-workmanship versus the mechanical, for a willingness to spend enough money to get true quality versus a short-term bargain. Tiffany copyrighted his designs and publicly warned others not to breach this legal claim. Despite the seeming modesty of some of the gravestones, the Tiffany name, as with the firm’s other products, was used most of all to guarantee the buyer of one thing, an absence of risk. Surely you were safe from criticism if you owned a “Tiffany” gravestone.

Figure 67.

Gutzon Borglum, Ffoulke Memorial (Rabboni), installed 1912. Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. Photo from Rock Creek Cemetery, Rock Creek Church Yard, Washington, D.C. (pamphlet), 1933.

It was in this context that elite Americans continued to make their own decisions about memorialization and value in the years after Henry Adams and the Milmore family commissioned their memorials and Frank Duveneck and William Wetmore Story realized theirs. Many wealthy individuals still chose enormous amounts of granite. But a few who wished to establish a distinctive memorial legacy chose original high-style monuments, figurative compositions made of bronze by well-known sculptors whose work appeared in museums and fine-arts expositions, to distinguish themselves from the masses. Works like the Hubbard Memorial by Karl Bitter in Green Mount Cemetery in Montpelier, Vermont (Plate 8); the Marshall Fields Memorial by Daniel Chester French in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery; the “Rabboni” sculpture (Figure 67) for the Ffoulke family in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C., by Gutzon Borglum; and the Pulitzer monument in New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery and Kauffmann Memorial in Rock Creek Cemetery by William Ordway Partridge are among those that stand out in this new wave of funerary sculpture.40 Memorials from this period by fine-art sculptors Adolf Weinman, James Earle Fraser, Philip Martiny, and Lorado Taft also decorate cemeteries, as well as contributions from Paul Bartlett, Bela Pratt, Robert Aitken, Augustus Lukeman, Andrew O’Connor, and Hans Schuler, among many others.

The patrons for the new bronze monuments of the era recognized the value of the truly original work of art in the cemetery, concluding that art was not merchandise, and that the ability to rise above the desires and tastes produced in mass culture signaled an authentic identity and a legacy of great value.41 They could distinguish themselves and their loved ones from the masses in death as well as life. As discussed in the previous chapter, sculptors’ efforts were validated by exhibition of cemetery memorials at high-art venues and inclusion of models in collections of museums like the Metropolitan. In their ardent desire to separate themselves from the commercial context, these fine-art sculptors and patrons took great offense when monument companies hired artisans to make illicit copies of memorials. They felt that unapproved reproduction and reinterpretation diluted and vulgarized their original contributions, which had been intended to mark the deceased as extraordinary people. The singularity of a monument was supposed to suggest the exceptional quality of an individual’s morality, public service, and taste. But this was another area of risk, the risk of visual piracy.