Born from the geographical reordering of Europe at the end of the First World War, Czechoslovakia was formerly a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The efforts to meet the national aspirations of the Czechs and Slovaks and to integrate them into the Allied camp had begun in 1916.

The key to understanding how this army came into being, before the birth of its nation state, is the fact that the Czechs and the Slovaks had long been submerged in a multi-national empire, which paid scant attention to their individual aspirations, power being vested in the more populous constituent nations. Two famous individuals laboured to promote the interests of these two peoples: Thomàs G Masaryk, a philosophy professor, and Edouard Beneš, one of his pupils who himself became a philosophy professor. In the course of numerous negotiations, the Allies, who at that point included the Russian Empire, began to consider that the enmity the Czechs and Slovaks bore towards the Austrians could be turned to their advantage. As early as 18 October 1914, the Czechs and Slovaks in Russian prisoner-of-war camps began to be separated from other Austro-Hungarian prisoners. Then in February 1915, the 11th Austrian Regiment, composed of a majority of Slavs, refused to fight the Serbs, and the 36th Regiment mutinied against its officers.

The National Council of the Czech Peoples was created in Paris with the support of Aristide Briand. Also in Paris, the popular artist and illustrator Alphonse Mucha also laboured tirelessly to promote Czech nationhood. At the Front, the embryonic Czech Army, the Česka Družina scored its first victories and took its first prisoners. In 1915, there were 4000 Czech prisoners of war in France, 50,000 in Russia and 10,000 in Italy. Their potential employment against the Austro-Hungarians would weigh heavily against the Central Powers. By 1916, there were 300,000 in Russia, and the decree recognising the existence of the Czech Army was signed. The Russian Revolution upset the existing situation, however, and an agreement between the Bolsheviks and the Czechs allowed for the latter to move to the Western Front. The Germans, however, stood in the way of this redeployment, and the Czechs began their long withdrawal to the East over the Trans-Siberian Railway, with the 1st Regiment acting as rearguard throughout.

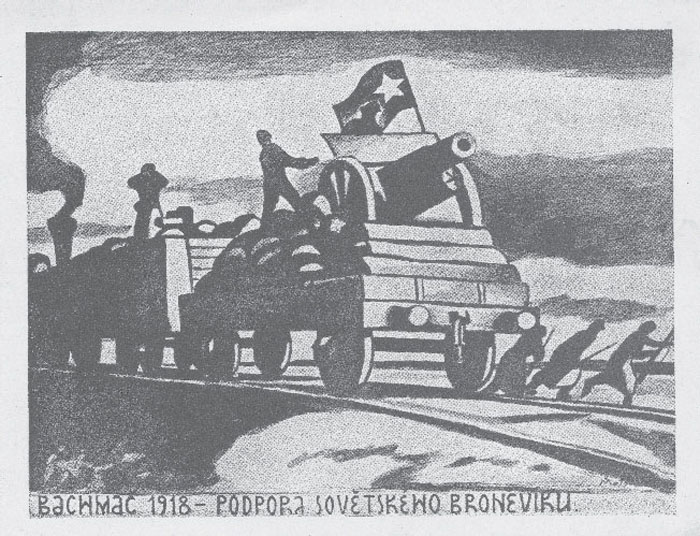

Their route followed the railway, and their primary concern was the security of the rearguard, especially when the Reds began attacking them. To hold the critical junction at Bakhmach, Captain Cervinks, commanding the 6th Regiment, set in hand the construction of an armoured train in March 1918, comprising a steam engine, a van and three mineral wagons. Protection was provided by sandbags, and it was armed with machine guns and the crews’ rifles. On 1 June the train gained a field gun in the chase position, greatly improving its firepower, and its patrol missions ensured the safe passage of the Czech troops. Thus the armoured trains were born out of the mission assigned to the Czechoslovaks by General Janin, head of the French Military Mission, which was to guard the railway lines. The territory they controlled extended for 10km (6¼ miles) on either side of the tracks, and by 1919 this so-called neutral band was the only territory not in the hands of the Reds. The protection of certain parts of the line was assured by the Polish Legion, which deployed three armoured trains.

Of the twelve regiments taking part in the withdrawal, it appears that only two, the 5th and 11th, did not possess armoured trains. Construction and entry into service of the armoured trains took place principally from May to September 1918, even though certain trains did not see the light of day until 1919, such as those of the 8th and 9th Regiments. Other trains were not incorporated into regiments, such as the anti-aircraft train built by Captain Kulikovski in late September 1918 at Chaytanka. The armoured train of the Attack Battalion was built between the 16 and 20 June 1918 at Kansk, and took part in the battles covering the retreat as far as Lake Baikal in July–August 1918.

The 1st Regiment possessed one train, built near Kinel in June 1918, armed with a 76.2mm Putilov gun in the leading wagon. Designated No 3, it was destroyed during the battle of Bouzoulouk on the 25th of the same month.

Of the four armoured trains of the 2nd Regiment, the two equipped and manned by the First Platoon were destroyed, one on the Volga on 23 October 1918, and the other on the River Ik. The train commanded by Lieutenant Netik had to its credit a Red armoured train knocked out on 26 June 1918.

The 3rd Regiment was the most prolific user of armoured trains, but the size and armament of each of its trains was relatively modest: in general one single wagon with a chase gun, and several bogie wagons protected by sleepers and sandbags. These trains were all built in June 1918, and instead of individual train names they were known by the name of their commander: Malek, Lt. Iijnsky, Lt. Sembatovic, Captain Nemcinov, Captain Urbanek (of which the command passed to Captain Troka on 6 July) and Nepras.

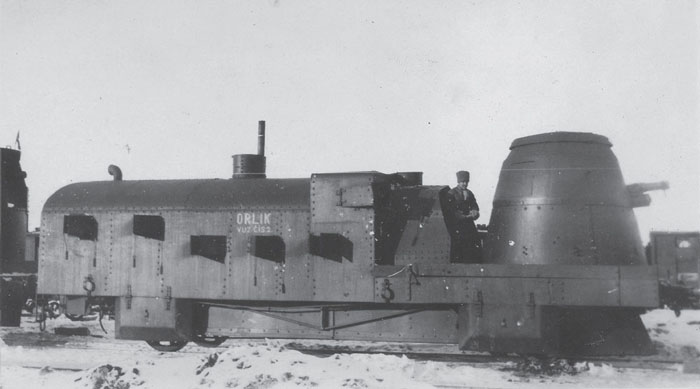

The 4th Regiment possessed the most famous armoured train of the Civil War period, Orlik2 (see also the chapters on Russia and China). Bearing the name Lenin, it was captured intact from the Reds at Simbirsk on 22 July 1918 and was renamed Orlik two days later. It immediately went into action on the Simbirsk-Tchita line. In October 1918 it was split into Orlik I and Orlik II, which operated from Priytovo and Abdulino respectively. Once more combined into one train, it assured the security of the Trans-Siberian during the Summer of 1919, at a time when the line was suffering continual sabotage. When the train was based at Irkoutsk Station, General Janin noted that the area was calm and that ‘Armoured Train Orlik … guaranteed order’. At Tchita on 8 April 1920, it was involved in an incident when the Japanese forced the crew of four officers and 100 men to hand over the train to them. Following diplomatic exchanges, the train was handed back to its crew on the 13th. After the last Czech troops departed on 20 May 1920, the train once more came into the possession of the Japanese, who were occupying the region, but the Americans insisted it be handed to the White Russians. The latter used it up until Autumn 1922, but when Vladivostok fell to the Reds, Orlik joined the army of Zhang Zongchang in China.

The name of this train was popular with the Czechs, as the 4th Regiment possessed another Orlik, built at Penza in May 1918. Commanded by Captain Sramek, it had a crew of sixty men, and carried an armament of nine machine guns and two armoured cars. In late May a flat wagon carrying an artillery piece was added, but the train was seriously damaged the very same day. In a single night, it was rebuilt using new wagons. Its crew was reinforced, to a total of six officers and 200 men. It took part in the battles of Abdulino and Tchichma on 3 July. On that date it assumed the name of Orlik I to avoid confusion with the ex-Lenin of the same name, and was in action continuously up until the battle of Simbirsk on 8th and 9th September, where its leading wagon was destroyed and its gunners killed or wounded, along with the train commander. Shortly after withdrawing to Kindiakovka it was taken out of service.

The 4th Regiment built an Orlik II which was in action from July to November 1918. After the fighting before Bougoulma in early August, it was hit by fire from a Red train and was forced to retreat. It then covered the retreat from Bougoulma to Zlatoust, where its combat damage was repaired, then on 20 November it was decommissioned.

Armoured Train Grozny, built at Penza in May 1918 and armed with an artillery piece and three machine guns, had a crew of 107 men. It was given the unenviable role of covering the rearguard of the 4th Regiment during the retreat, this regiment being now the rearguard of the entire Czech Legion. The most powerful part of its armament was the rear flat wagon, on which was mounted a Putilov-Garford armoured truck. It was reorganised twice: on the first occasion its crew was increased to 160 men and its armament to two guns and ten machine guns. Two armoured bogie wagons were added on 24 June. In August 1918 it was again transformed, being split into two: the part retaining the name Grozny kept the armoured truck. Its crew were forced to sabotage it on 23 October 1918. The other part kept the second gun and the ten machine guns, under the designation ‘Armoured Train No 29’. It too had to be sabotaged in September.

Little is known about Armoured Train Sirotek, but a last train operated by the 4th Regiment was improvised by Captain Snajor to replace Grozny and continue its mission of supporting the rearguard.

The 6th Regiment, in addition to its first train built in March 1918, equipped three armoured trains (two in early June and the third in August). One ‘Train of the 6th Regiment’ counted among its battle honours the destruction of a Red armoured train on 27 June.

The sole train operated by the 7th Regiment was built on 25 May at Mariinsk. During its first action it comprised just one bogie wagon armed with two machine guns. Its armament was then increased by the addition of an artillery piece. On 26 June, it was hit by fire from a Red train but was able to retreat to Lake Baikal, where it took part in the fighting at Koultouk on 18 July, before continuing to cover the withdrawal.

The 8th Regiment operated Armoured Trains Mariinsk and Těšín, and also a train formed on 1 July 1918 at Ougolnaya in Manchuria, at first armed just with machine guns, but later naval guns were added. Towards the end of the fighting, it operated in the Oussouri sector between Vladivostok and Khabarovsk.

Armoured Train Údernik of the 9th Regiment saw service in May–June 1919.

The 10th Regiment lost its only armoured train, built at Nijne-Oudinsk in June 1918, when it was captured by the Reds on the 22nd of that month.

The 12th Regiment employed an armoured train about which little is known, apart from it taking part in the battle of the Ekaterinenbourg junction in October 1918.

Six trains were deployed in May–June 1919 to secure the central line of the Trans-Siberian to the west of Ienissei and assure the freedom of movement so vital to the Czechs. They were: the train of the Light Battery (not attached to a regiment), Armoured Train Údernik of the 9th Regiment, and Armoured Trains Těšín and Mariinski of the 8th Regiment; the zone to be patrolled extended from Taiga/Tomsk to Atchinsk, a distance of some 300km (190 miles), and in the Summer of 1919 this became the responsibility of Armoured Trains Tajšet and Spasitel of the 1st Regiment.

In conclusion, during their withdrawal to Vladivostok via the Trans-Siberian Railway, which was their only chance of returning to Western Europe, the Czech Legion used thirty-two armoured trains, three of which were captured from the Reds. In all, in the course of the campaign, they captured twenty-five Bolshevik armoured trains, and destroyed two more.

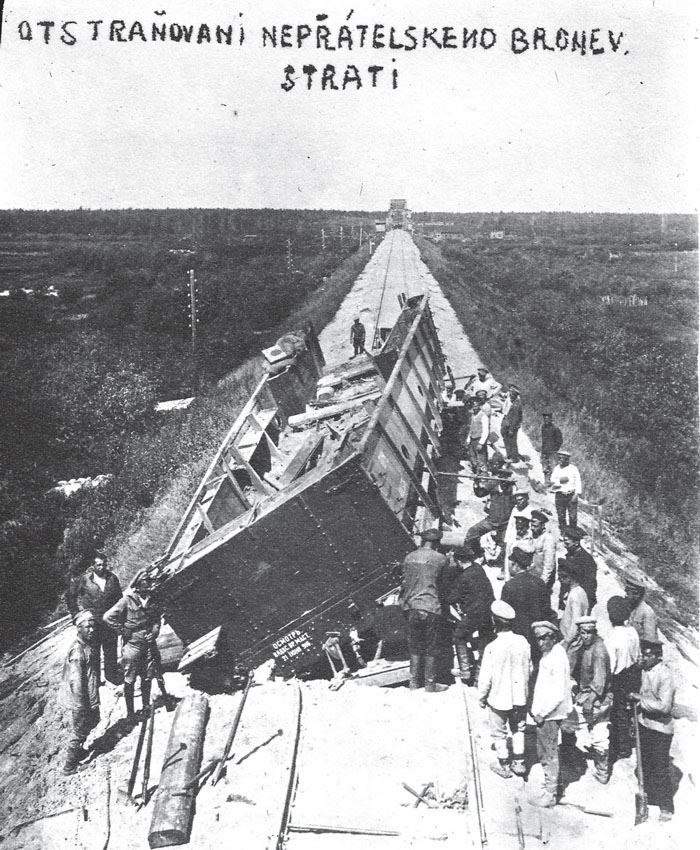

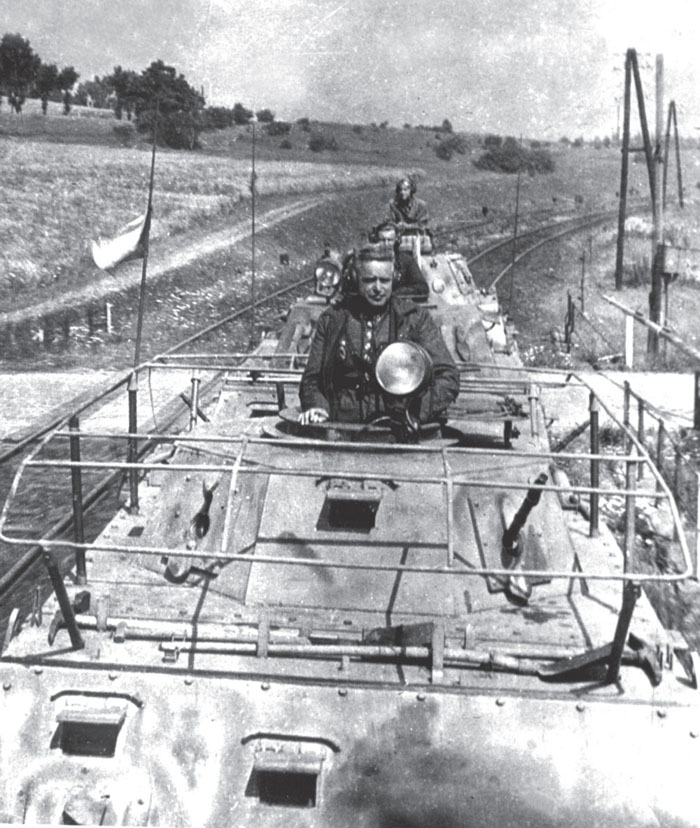

Despite the apparent sense of security in the open countryside, the trains, armoured or otherwise, used by the Czech Legion in its long journey towards Vladivostok suffered continual attacks.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A well-known photograph taken at Oufa. It is interesting as it shows the considerable firepower provided by at least six machine guns mounted on each side of the wagon. On the left are 7.62mm Maxim Model 1905/1910s, and on the right the first machine gun is a Colt-Browning M1895 ‘Potato Digger’, of which several thousand were ordered by Russia in 1914 in 7.62mm calibre.

(Photo: Vojenský Ústřední Archív, Vojenský historický archiv – VÚA-VHA)

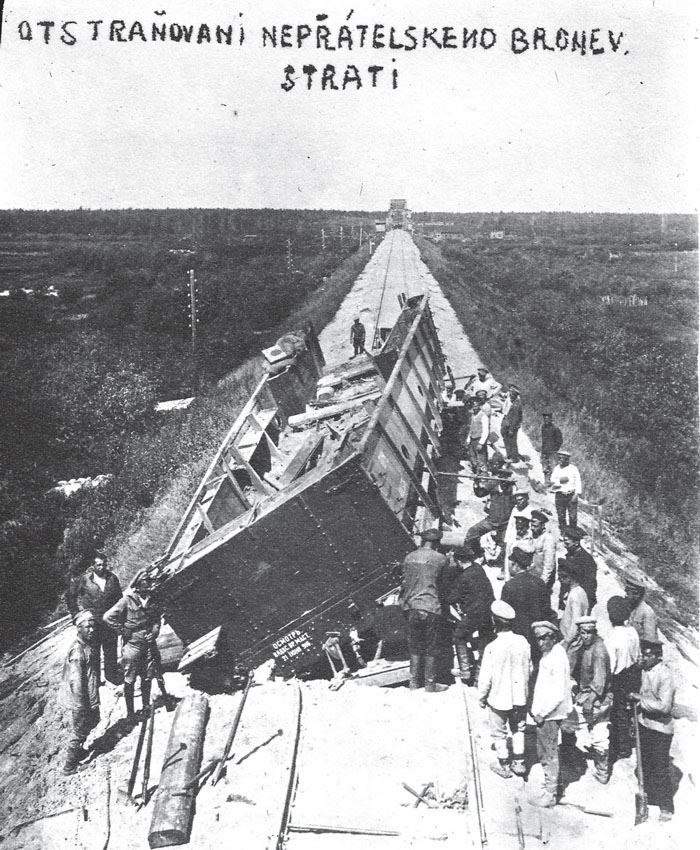

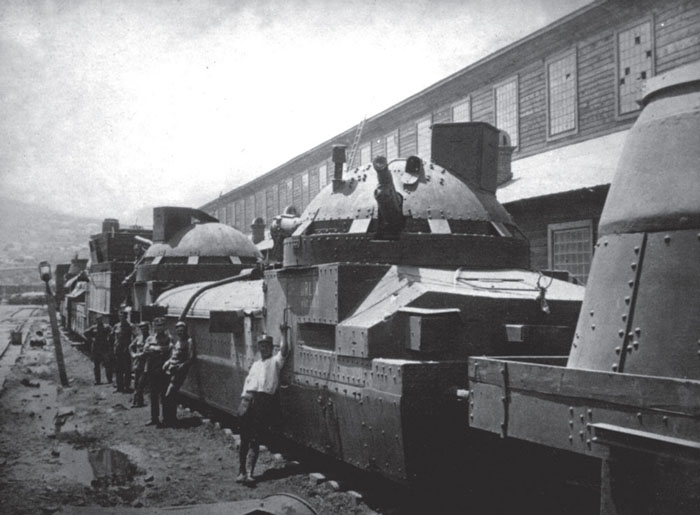

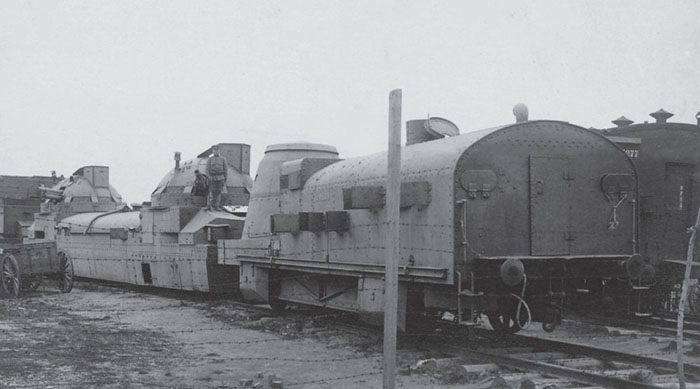

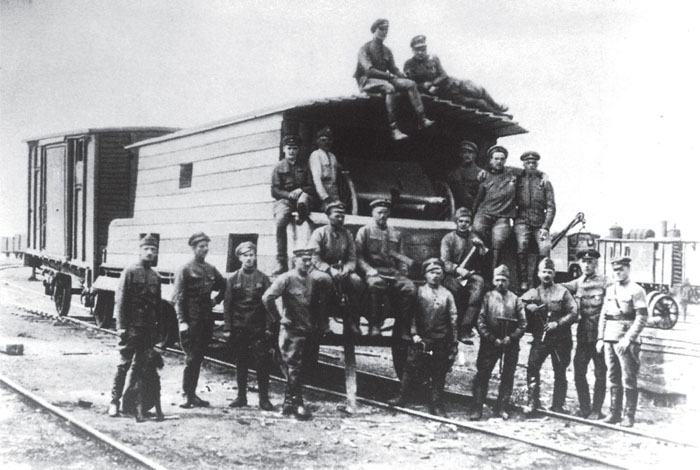

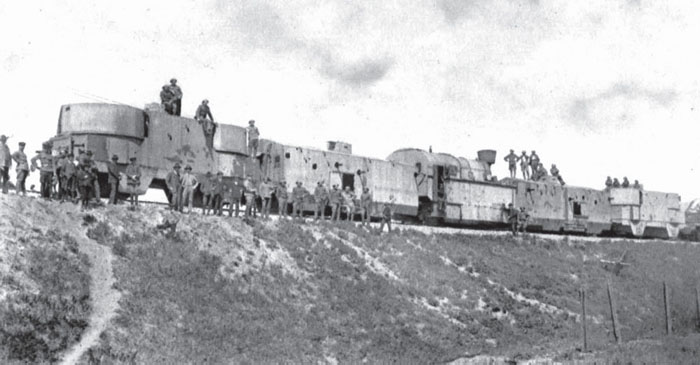

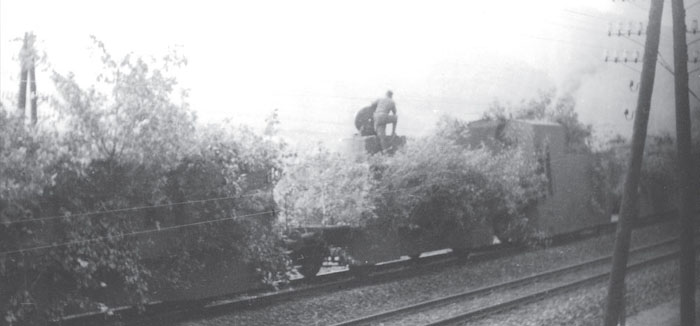

One of the first improvised armoured trains, probably No 6, seen here at Tcheliabinsk in 1918. Note the limited protection, even on the engine which has only the cab protected, but sufficient at the start of the conflict to cut a path through the bands of marauding Bolsheviks.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

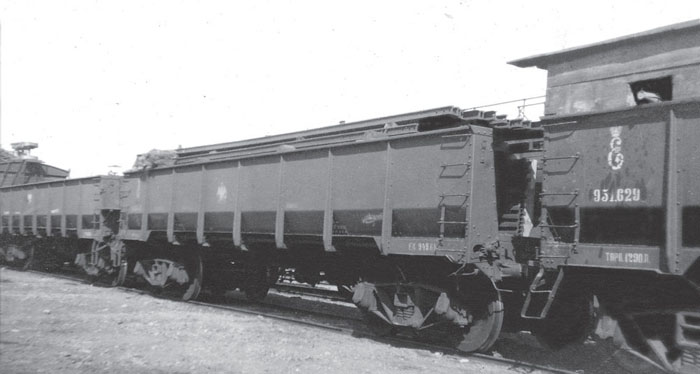

Seen from this angle, the train appears unarmoured, but over and above those trains formally designated as ‘armoured’, all the Czech trains were fitted with a certain minimum level of protection.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

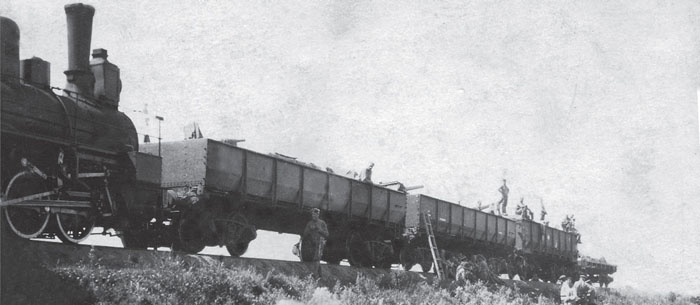

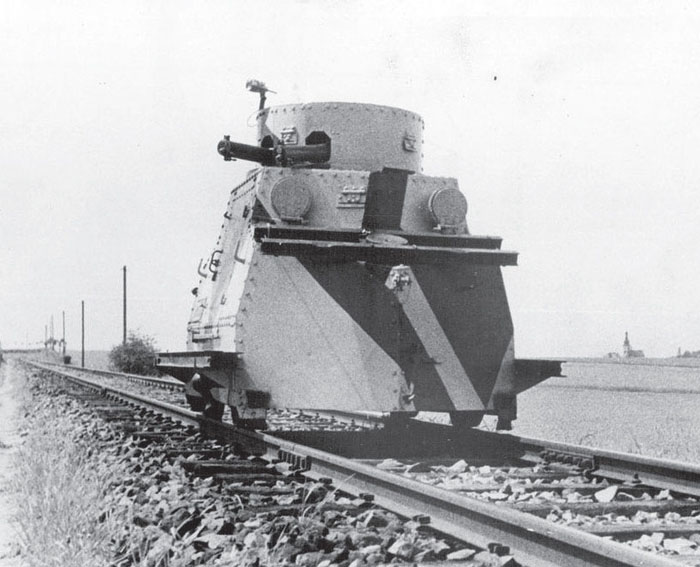

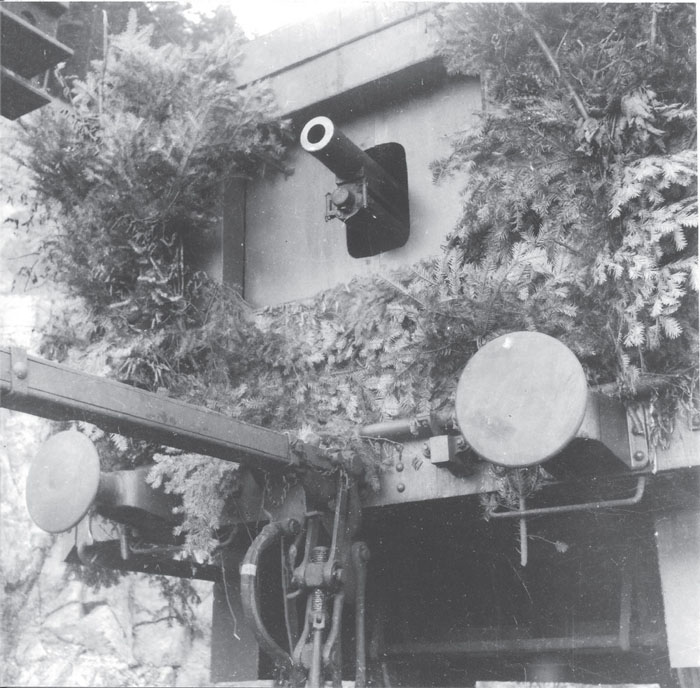

A typical shot of one end of an armoured bogie wagon armed with a Russian 76.2mm gun. Note that only a small amount of training is possible. Obviously, the work to fit the internal armour has not yet been completed.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

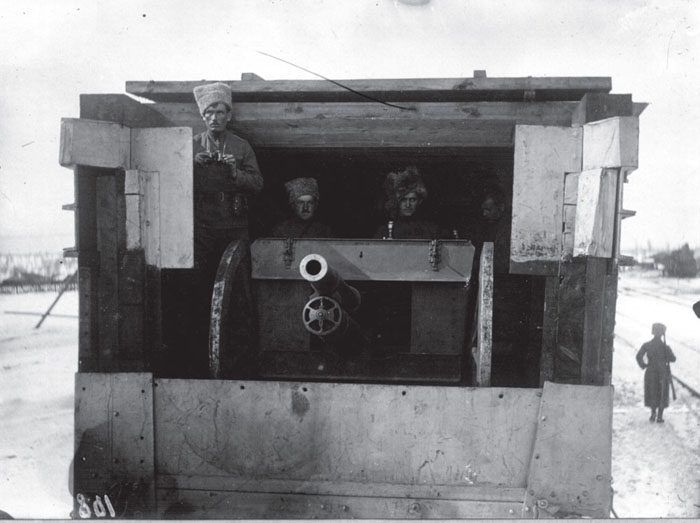

Perhaps another shot of the same wagon. The 76.2mm Putilov Model 1902 gun, with a range of more than 8000m (5 miles), was the standard armament of the Czech trains.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

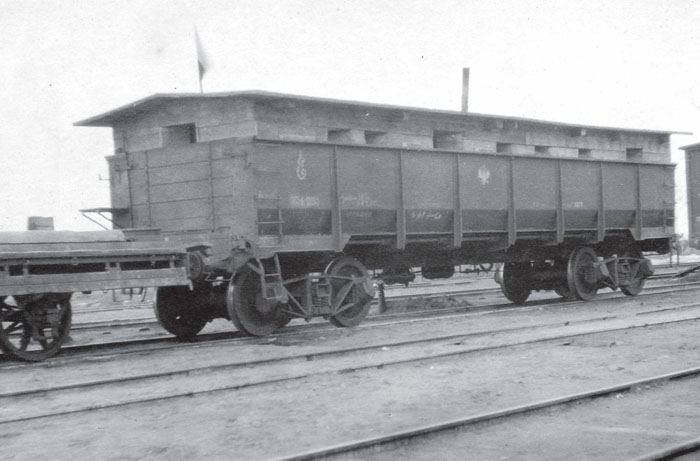

One of the various types of armour protection on the bogie wagons used by the Czech Legion. The sides have been raised, and the V-shaped armour prevents projectiles from remaining on the roof before exploding. In addition, loopholes have been pierced in the wagon sides. Unusually, the armament appears to be a German 7.58cm Minenwerfer (trench mortar) neuer Art.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

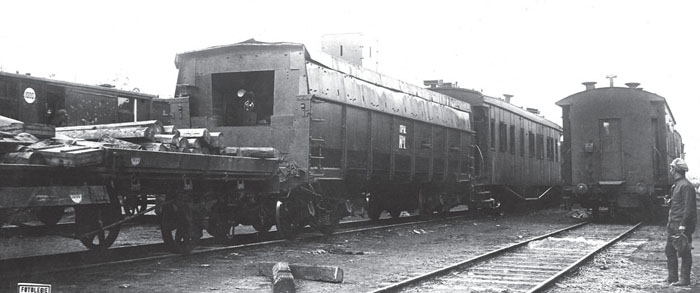

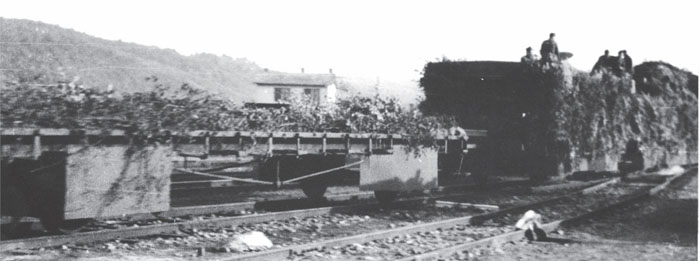

This wagon coupled behind the engine shows the typical features of the first armoured trains: increasing the height and roofing over of the sides, particularly to protect the crewmen against the extreme cold (note the stove chimney). Clearly visible are the diamond bogies which were particularly adapted to the often-irregular track found on the Trans-Siberian.

(Photo: ECPA-D)

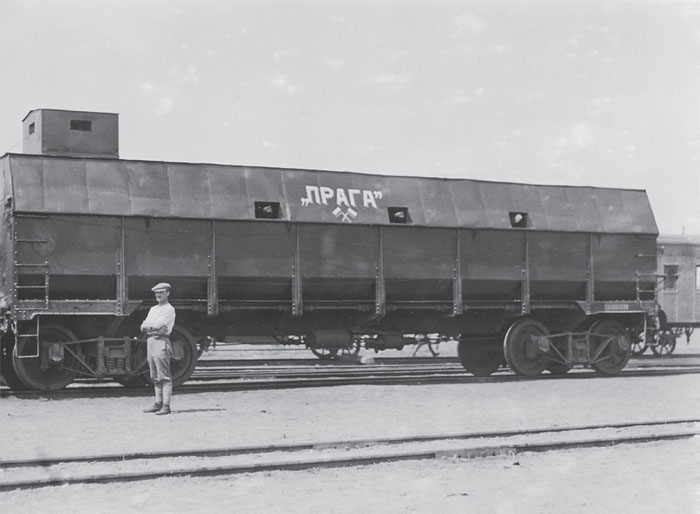

A wagon from Armoured Train Praha, proudly displaying the national flag. The armour is well-designed, again fitted on a standard Russian Railways wagon.

(Photo: ECPA-D)

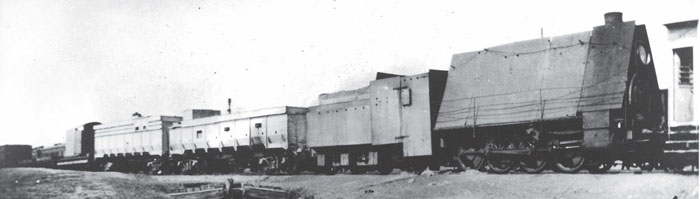

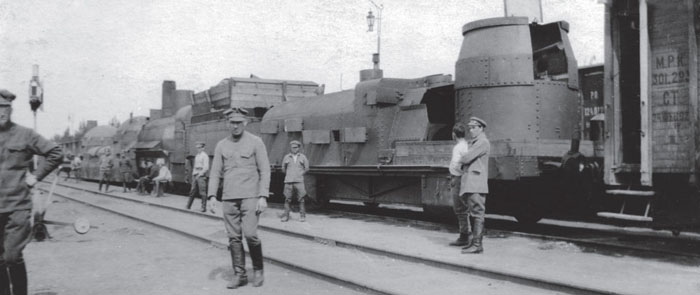

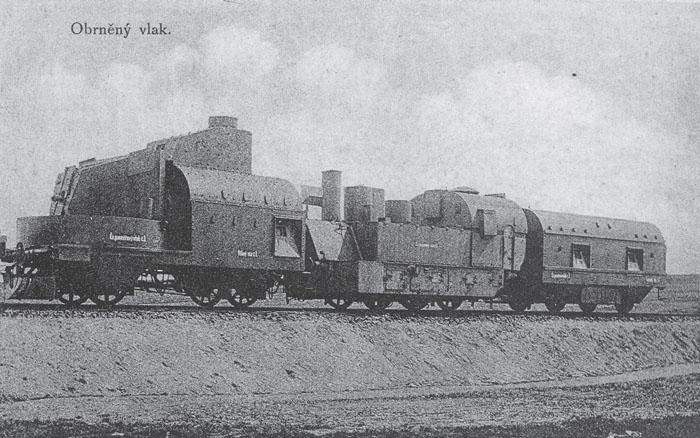

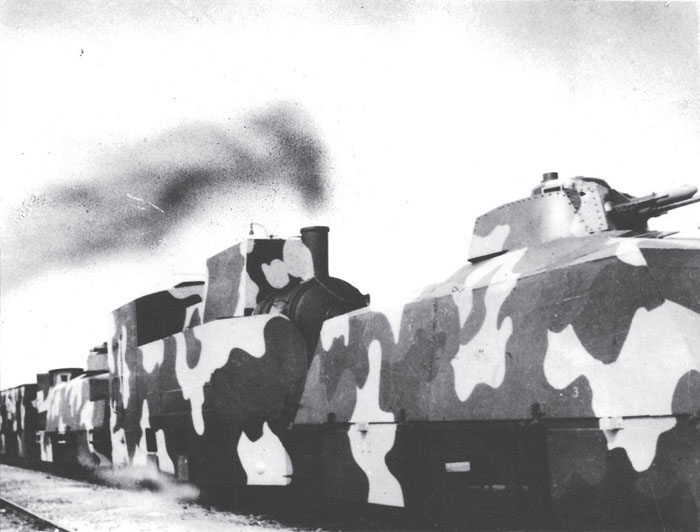

A well-known postcard of the period showing a Czech armoured train assembled from Russian rolling stock. The protection on the engine, seen here from the front right, is relatively simple, and the armoured wagons have all been built on the base of standard high-sided bogie wagons. As time passed, the design of the armour protection would evolve significantly.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another example of an armoured bogie wagon on the Trans-Siberian. This one is perhaps a captured Bolshevik wagon, with its 76.2mm gun in the chase position.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

On the other hand, this wagon is instead devoted to close-in protection of the train, with loopholes for small arms, and perhaps also a machine gun, as suggested by the larger central embrasure.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This interesting view allows us to clearly see the roof protection provided by lengths of rail, and through the rear opening more rails arranged to form an internal partition, separated from the sides of the wagon by a layer of wood.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

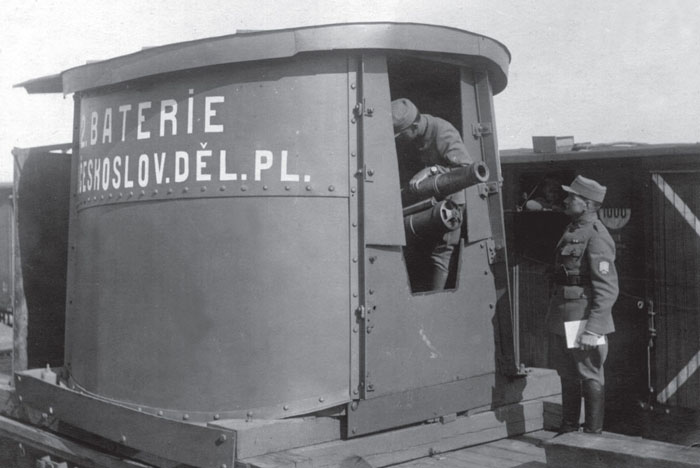

Seen in 1918, one of the revolving casemates of the armoured train of the Second Battery of the 1st Artillery Regiment. The van to the right bears the usual ‘X’ marking denoting explosives.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

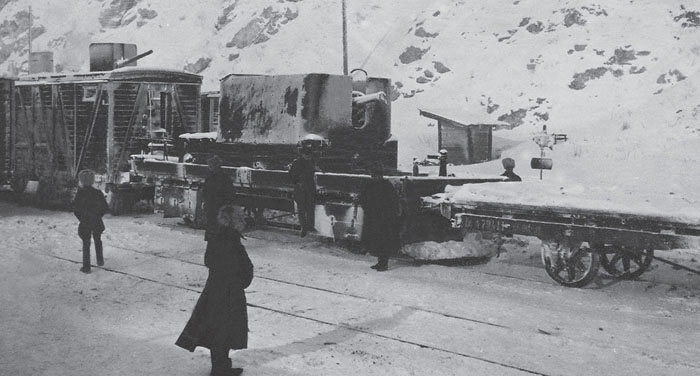

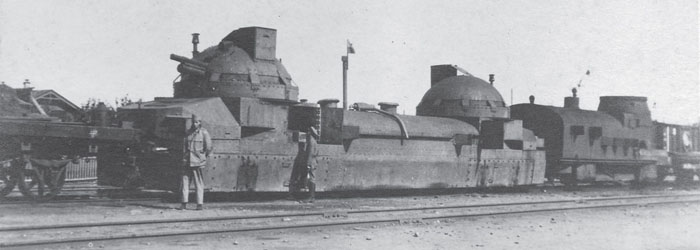

It is difficult to tell whether this train is Czech or White Russian. Nonetheless, the revolving casemate is rudimentary but interesting. Note the the cowcatcher, and also that the van next in line has an upper firing position and an observation cupola.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

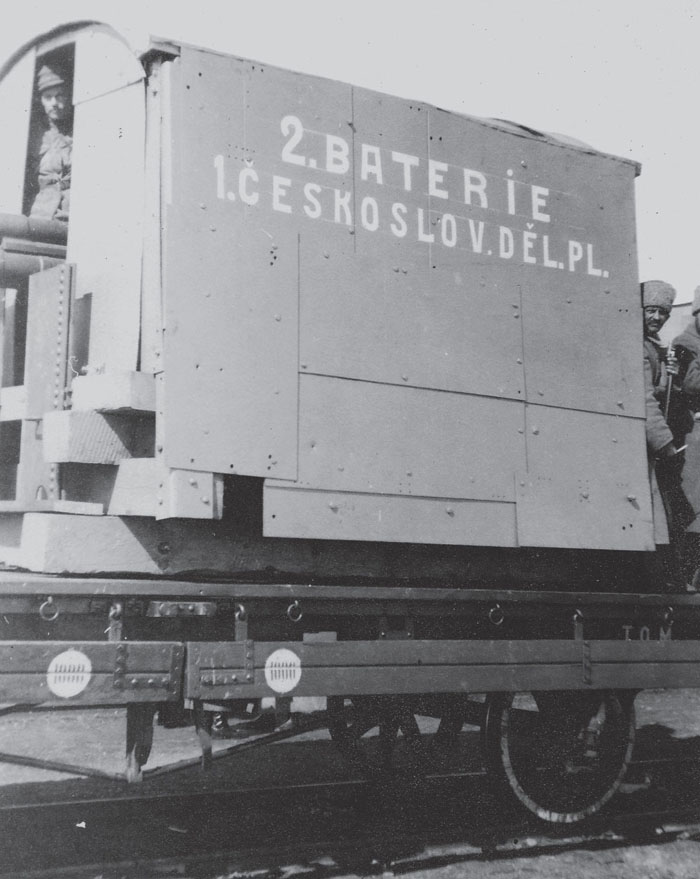

The other casemate of this battery shows the construction technique used, with plates fastened over an internal framework.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This photo of the leading wagon of the same train, probably taken later in the campaign, show how it has evolved, notably in the profile of the casemate. Cowcatchers have by now become standard, and also double as snowploughs.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

An interesting shot showing the final version of Orlik, on 2 June 1918. The Austin armoured car was used as a machine-gun wagon. Note the open door of the van in which a field gun is installed.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

Orlik as a complete train, with the railcar Zaamurietz coupled immediately behind the engine. Note the Czech flag.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

One of several views of the self-propelled element which made up Orlik I when operating independently of the rest of the train.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

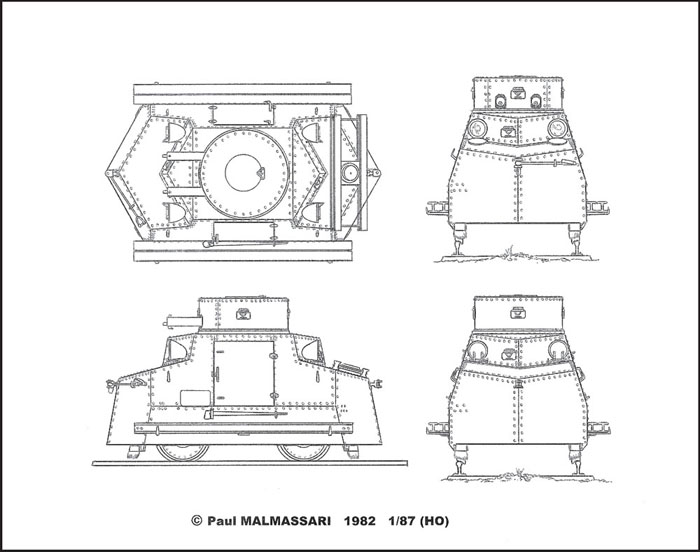

Designed in 1915, later changes involving principally its armament, this railcar had a modern configuration, much more advanced than most later designs.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

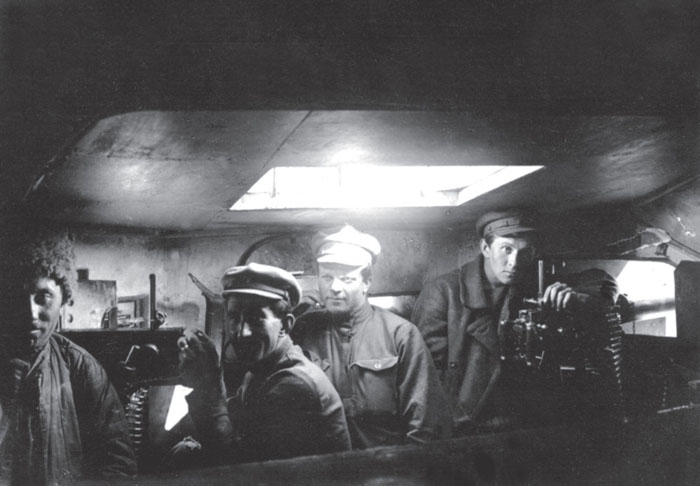

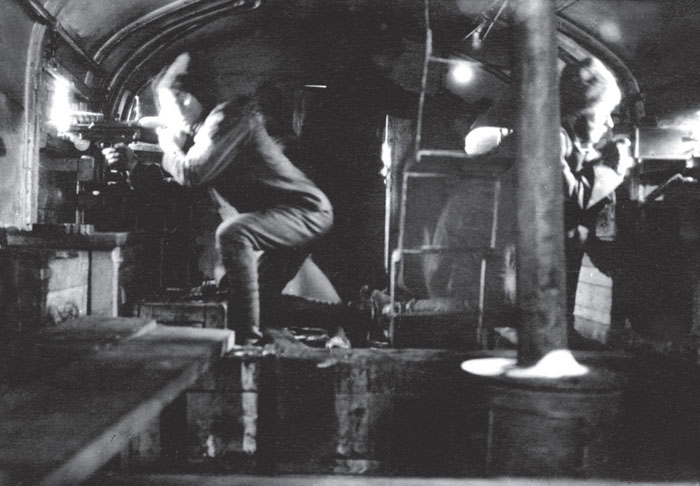

A shot showing the interior of an end compartment on Orlik, with the two corner machine guns and the access hatch open.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

As the inscription in Czech confirms, this wagon belongs to the part of the train made up of the wagons and the engine (Vuz cis. 2 = Part No 2, Part No 1 comprising the railcar operating independently). The turret is armed with a Russian 76.2mm Model 02, which can train through approximately 270 degrees.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The machine-gun positions in the central section of the railcar. Note the essential element present in all the armoured trains and even the wagons on the Trans-Siberian, the stove.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

A view of the other end of the artillery wagon, here coupled to the railcar.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The other artillery wagon of Orlik. Despite the fact that the two wagons were built on the same base vehicle, the turret with all-round traverse installed in place of the original chase gun has a different armament, a 76.2mm Model 1904 mountain gun.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A fact never previously published: Armoured Train Orlik received the French Croix de Guerre (top left of the pennant) from General Janin on 24th March 1920, for its service during the entire Trans-Siberian conflict. This pennant bearing Orlik’s insignia no longer exists.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

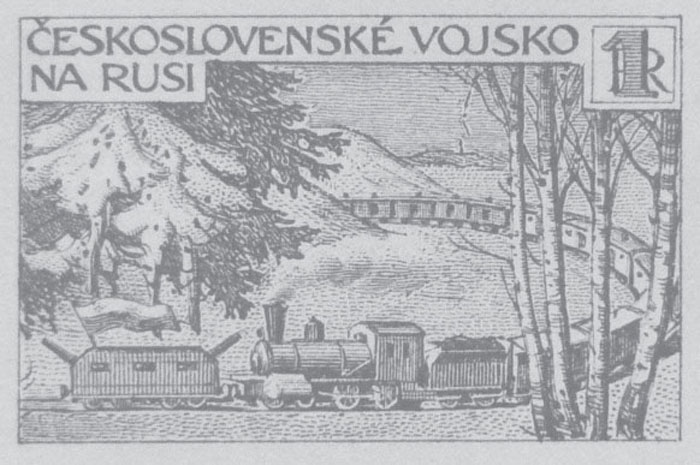

Interestingly, a postal service was set up to convey the correspondence of the Czech Legion, but also that of the local Russians, whose postal service had collapsed because of the Revolution. It began to operate on 18 September 1918, over an initial distance of 4000km (2500 miles), and was then extended to 7000km (4375 miles), taking two weeks to travel the length of the line to Vladivostok. Among several different images used on the stamps was one featuring Armoured Train Orlik, on a stamp of the second issue which appeared in 1919.3

The yellow-gren 50-kopeck issue.

(Stamp: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A series of three stamps, printed in red, bistre and green, was also issued to commemorate the Czech soldiers who made the epic crossing of Siberia to build their nation, here featuring the bi-colour flag of the period flying from the armoured wagon at the head of the troop train.

(Stamp: Paul Malmassari Collection)

While the Družina was forging the national spirit of Czechoslovakia by fighting its way across Siberia, the new army was also being created in the homeland. Called to fight on the new national borders, it used armoured trains firstly of foreign origin then those produced at home. The Czech Army subsequently maintained a force of six standardised armoured trains up until 1938.

With the defeat of the Central Powers in 1918, PZ II (MÁV engine 377.116, wagons Nos 140.914 and S150.003) and several wagons and a steam engine from Austro-Hungarian PZ I and IV were captured in Prague. On 18 November 1918 the first Czech armoured train, numbered II, left for the Slovak Front and added a new infantry wagon (S150.271) from the ex-Austro-Hungarian PZ VII. It was then divided into two, one part forming the principal armoured train proper (PV II-a) and the other the support train (PV II-b). The first part remained in Slovakia from December 1917 to the following Spring, to secure the new borders. It next fought the Hungarians, and on 12 June in particular, it employed a technique unique to armoured trains, sending a safety wagon loaded with ballast to crash into a Hungarian armoured train parked in Hronská Breznice Station. The Hungarian train was certainly damaged, but having expended its safety wagon, the Czech train set off a mine the following day. Renumbered as No 1 on 21 July, it defended the border between Luèenec and Filakovo up until March 1920.

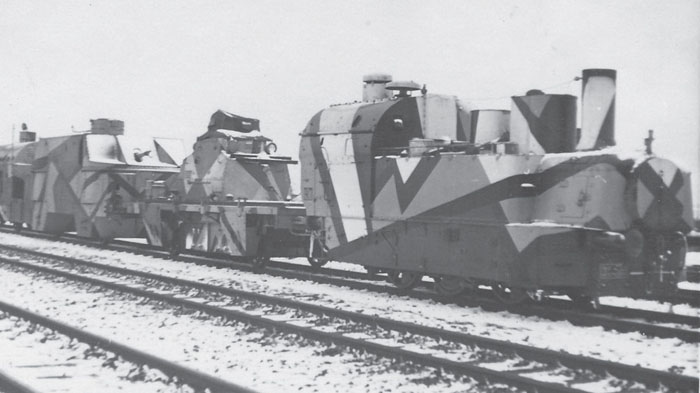

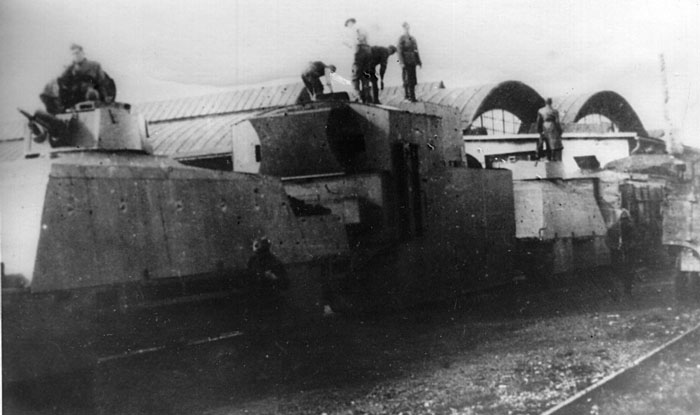

A composite of two ex-Austro-Hungarian armoured trains, as confirmed by the presence of a wagon on the left from a Type B (see the chapter on Austria-Hungary) and from a Type A on the right.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

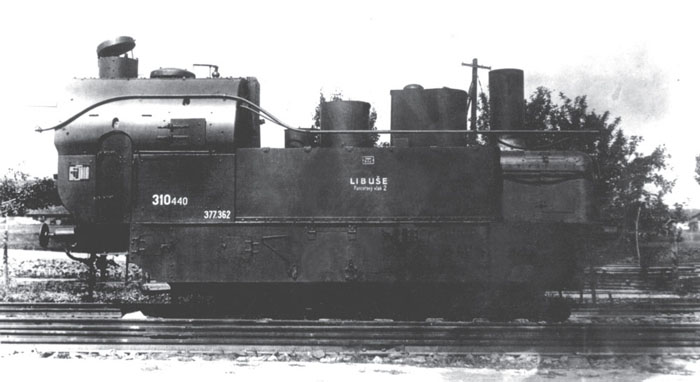

Armoured engine 310.440 (ex-MÁV 377.362). The name ‘Libuše’ refers to a legendary prophetess, granddaughter of Cech, the mythical founder of the Czech people, who chose a husband to favour the national interest over her personal feelings. Note the observation cupola above the cab, as well as the pipe enabling the transfer of water between the engine and the wagons.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

PV II-b went into service on 15 December 1918 and left Prague for the Sudetenland border. In the region of Kosice, it was integrated into the 6th Division of the Italian Legion until May 1919. On 1 May it attacked the Hungarian station of Miœkolec and enabled the Czechs to recover engines and wagons captured by the Hungarians in the Slovak zone. It was renumbered as No 2 on 21 June 1919.

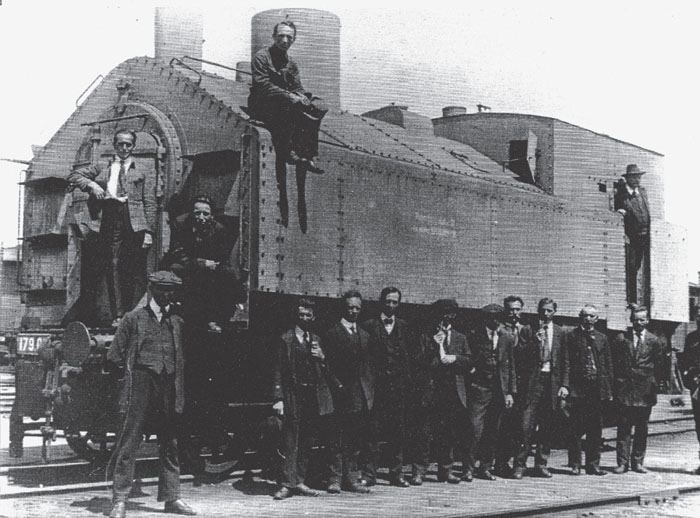

Engine 179.01 of Armoured Train General Štefányk seen here in 1919.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

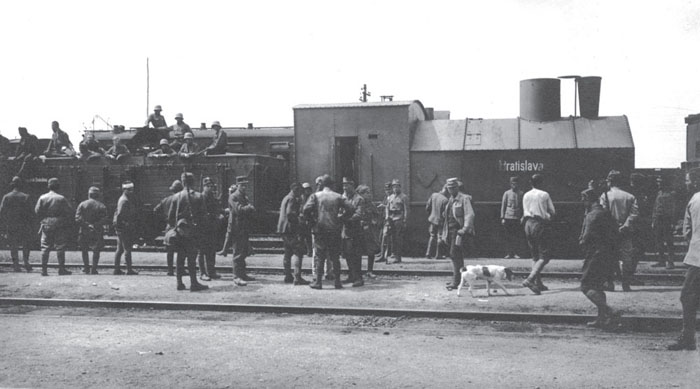

Armoured Train Bratislava at Slovensky Meder Station.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

An unidentified armoured train, dating from the period when the Czechs were forced to intervene militarily against their new neighbours. Its construction is interesting: the body has symmetrical openings at both ends, probably mounting two 76.2mm Putilov guns, and two-thickness wooden protection visible. Either the van at the rear is badly overloaded at one end, or the springs at that end have seen better days.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

On the left, wagon Kn 141.172, on the right wagon 149.902, and in between engine 377.455 of PV No 3. Note that this postcard features the tricolour Czechoslovak flag and not the bicoloured (red and white) original version, which dates this photo to later than 30 March 1920.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In late 1918 Armoured Train Brno was built in three weeks in the state armament factory in the Moravian capital. It comprised an armoured engine and two wagons. The leading wagon was armed with two Maxim machine guns in the chase position, and a 75mm M15 Škoda mountain gun in a turret; the other wagon was armed with two Schwarzlose machine guns. After having seen action against the Poles, it remained in service up until December 1920 when it was demobilised and put in reserve. Profiting from the experience gained, it was decided to build two similar trains, No 3 Bratislava and No 4 General Štefányk. Each train included a safety wagon, an artillery wagon and two infantry wagons.

Bratislava went into action in Slovakia in July 1919 against the Hungarians. Seriously damaged at Nové Zámky, it was dismantled at the Škoda factory in August and its number transferred to the Hungarian train being repaired in the same workshops. General Štefányk was completed too late to take part in the fighting against the Hungarians, but remained in service until 1925, with PV 1 first at Lučenec then at Milovicer.

In 1919, the railway workshops at Vrútky built a fourth armoured train following the pattern of the Austro-Hungarian trains (engine No 377.83, but flat wagons protected with concrete slabs), carrying the No 7. Then in January 1920 PV 3 went into service, being the units of the Hungarian train captured at Seèovce which had been repaired by Škoda.

Škoda built two complete armoured trains in 1919, Pilzen (No 5) and Praha (No 6), each one having two Class 99 armoured engines with protection 6mm thick, two safety wagons, two artillery wagons, two infantry wagons and an ammunition wagon, all the wagons being protected by 8mm of armour. Each train could also be divided up into two smaller units. Their crews numbered three officers and eighty-eight men.

The period 1919 to 1938 also saw the introduction of the Tatra-Škoda armoured trolley. During the 1920s the firm of Koprivnice built a reconnaissance trolley, which also interested the Poles, who purchased some twenty examples in 1926. It could be used coupled to a train (with the driving axle disconnected) or as an independent vehicle. The Armoured Trains Company received the only example purchased by the Czechoslovak Army in 1927.

Tatra-Škoda Czech Armoured Trolley

Technical specifications:

| Overall length: | 3.68m (12ft 03/4in) |

| Width: | 1.75m (5ft 9in) |

| Overall height: | 2.14m (7ft 01/4in) |

| Ground clearance: | 0.14m (51/2in) |

| Armour thickness: | 6mm to 10mm |

| Weight empty: | 2.5 tonnes |

| Crew: | 3 to 5 men |

| Armament: | 2 x 7.92mm Hotchkiss machine guns |

| Motor: | 2-cylinder 4-stroke water cooled |

| Cylinder capacity: | 1.1 litre |

| Fuel capacity: | 80 litres (21 Imperial gallons) |

| Maximum speed: | 45km/h (28mph) |

| Range: | 700km (435 miles) |

Opinions differ as to the existence of a reconnaissance road-rail vehicle. According to Major Heigl,4 Tatra was to have designed a 6x6 armoured vehicle of this type, with the following specifications, armament: two machine guns in diagonally-offset turrets; length: 7.6m (24ft 91/4in); width: 1.86m (6ft 11/4in); height: 3.1m (10ft 2in); speed: 60km/h (37mph) on roads, 80km/h (50mph) on rails. According to M. Caiti,5 this vehicle could have been created from the conversion of all the PA 1 and PA 5 armoured cars. To date we have found no evidence as to the existence of such a road/rail vehicle.

The Czech model Tatra, here armed with two Schwarzlose vz.7/24 machine guns.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

Armoured Train No 3 in Slovakia.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

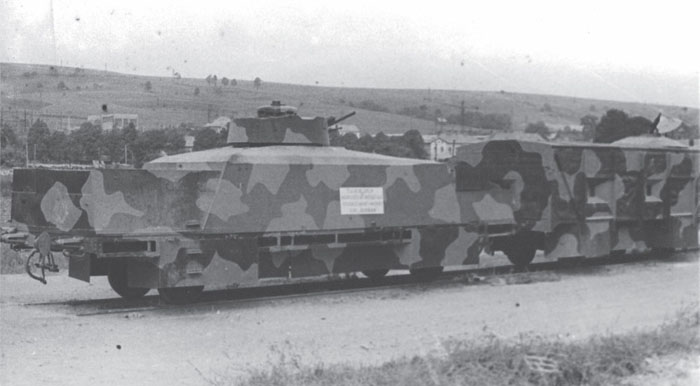

A rare photo showing the Czech Tatra armoured trolley with a modified turret, mounted on a special flat wagon which perhaps could allow it to dismount without external support. Note that when it is so mounted, its armour descends to the level of the flat car (it is also possible that the hull has been mounted without its wheels). Of interest is the complex camouflage scheme carried by Czechoslovak armoured trains, which remained unchanged when they were taken over and reused by the Wehrmacht.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The artillery wagon of Armoured Train No 4, seen from the safety flat wagon. It possessed a powerful armament capable of end-on fire, comprising a 75mm gun and two machine guns.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The six armoured trains remained in southern Slovakia between 1919 and 1923. On 7 July 1922 they were formed into an armoured battallion based at Milovice. In order to reduce the cost of hiring rolling stock, the railway company reclaimed the unarmoured wagons in 1925, leaving just the armoured engines and wagons. Then the armour plating was dismounted from the Class 99 engines and put into store, on condition that it would be refitted on the engines after giving two days’ notice to the railway authorities. Finally, in 1933 the unit became a regiment.

By 1934, the existing armoured trains were wearing out, and plans were made to build new units. The first option was the construction of armoured railcars weighing between 54 and 70 tonnes, with 32mm of armour and armed with 66mm and 80mm guns in turrets. ČKD and Škoda proposed designs, that of the latter firm was chosen, and and a model was built. The German occupation put a stop to these plans. The second option considered was to put improvised armoured trains into service to defend the frontiers, with rapidly-added protection, to be manned by reservists. Their armament was to be the classic 8cm vz.5/8 in the chase position plus several machine guns. A total of twelve such trains was envisaged.

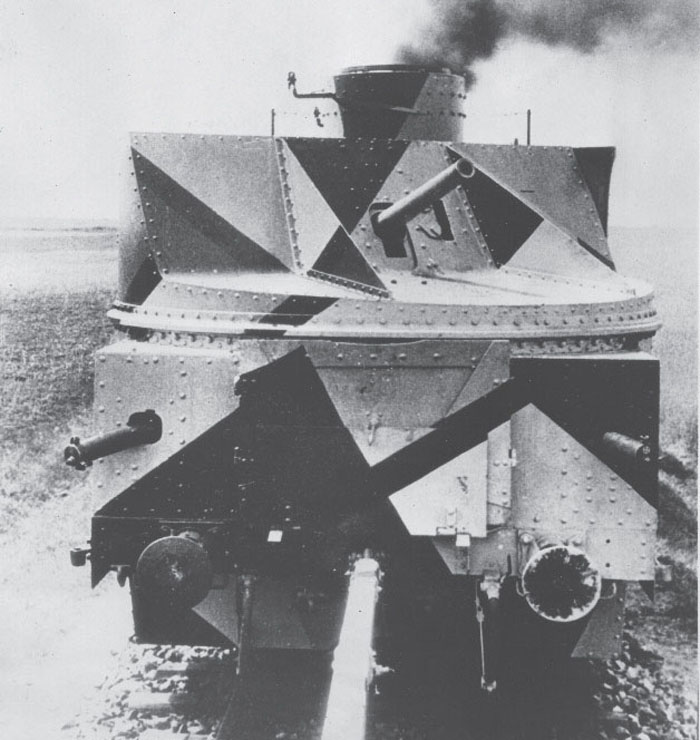

This type of wagon was designed and built by Škoda. Here is PV No 4. The machine-gun armament initially came from four different countries, standardised on 7.92mm German Maxim Model 08s, replaced in 1925 by 8mm Hotchkiss, and ending in 1929 with Schwarzlose vz.7/24 models.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Long before the negotiations leading up to the Munich agreement, separatist agitation broke out in Slovakia and Ruthenia. But on 30 September, the day before the agreement was signed, Czechoslovakia mobilised and put on alert the twelve improvised armoured trains to contain the Freikorps insurgents in the Sudetenland.

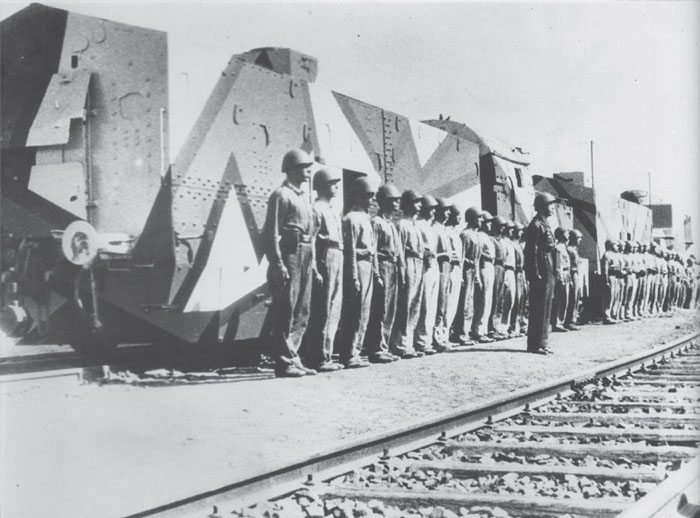

Overall view of a train with the second infantry wagon (also designated a machine-gun wagon) coupled at the rear, followed by a Class 377 engine, then the first infantry wagon and finally the artillery wagon. A safety wagon is only coupled at the front end of the train.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

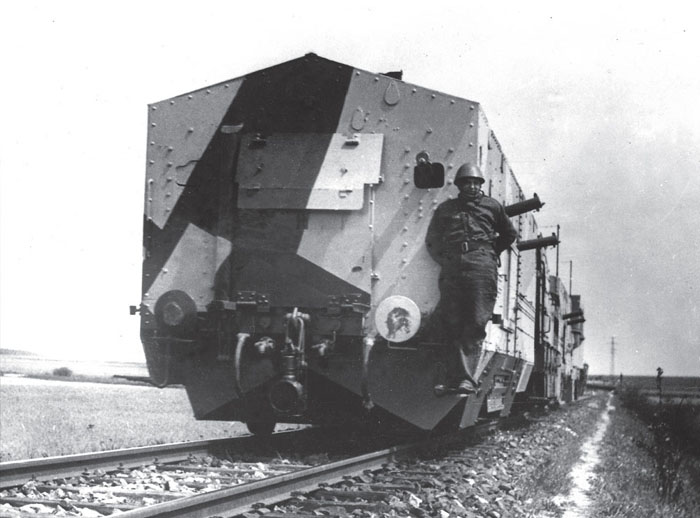

In this rare photo of an improvised armoured train at the time of mobilisation in 1938, note the hastily-applied camouflage on the wagon, and the ill-fitted armour plates on the engine. The gun is an 8cm Feldkanone M.5. The large number of crew members probably comprise the personnel of both the armoured train and the (unarmoured) support train. On the right in the front row is a railway employee of the CSD. In the centre of the front row is the train commander with the rank of captain (five-pointed star) and his sub-lieutenant assistant (three-pointed star). Finally, it appears that these reservists, assembled for the occasion, are wearing new uniforms.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Each train had a crew of two officers, one NCO and between eighty and ninety-one men (apart from Train No 3 which had only seventy-four men).

The Munich agreement did not put a stop to Hitler’s ambitions, and his annexation of Bohemia and Moravia led to the collapse of Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939. This led to the incorporation of the Czechoslovak trains in the list of German armoured trains, and at that period these units comprised the most modern elements of it. Their component wagons would continue to be divided up and regrouped until the end of the Second World War. The German trains composed of Czechoslovak elements would be PZ 23, PZ 24 and PZ 25. On the other hand, one of the improvised armoured trains of 1938, No 40, stationed at Zvolen, would join the newly-formed Slovak Army on 14 March 1939.

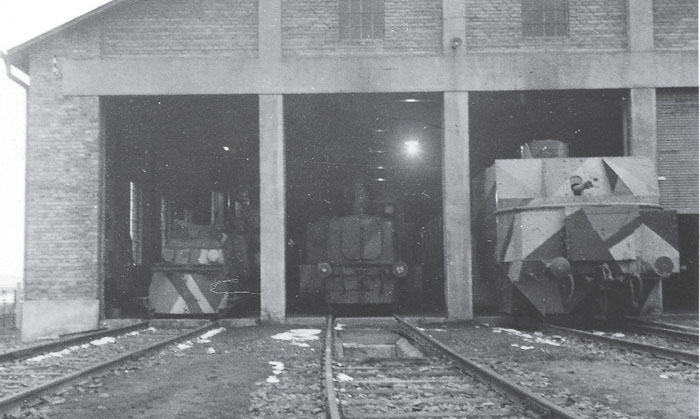

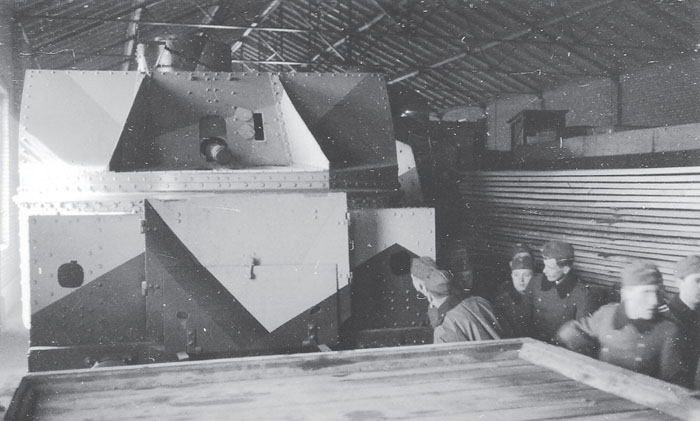

In March 1939, German soldiers photographed the depot at Milovice where all the armoured trains were gathered together (on the right, an artillery wagon of Train No 4, and on the left, the sole Tatra trolley mounted on its flat wagon).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Inside the depot, the artillery wagon (photo above) and the trolley (next photo) have aroused a great deal of interest. Several months later these units, still wearing their distinctive camouflage, would form new German armoured trains.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Note the device for moving from one track to the other, mounted on the bonnet of the trolley.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This uprising which started in Slovakia had as its aim the restoration of the former Czechoslovakia created in 1918, as proved by the names given to the three armoured trains taking part.

In Slovakia, resistance to the pro-German puppet government had begun during the invasion of the Soviet Union, when Slovak tank commanders and maintenance units deliberately returned broken-down tanks to Slovakia for possible future use against the regime. The initial ‘anti-fascist’ units were formed in late 1943, in the mountain regions. Their development was accelerated under the impetus given by the approach of the Red Army, by way of Poland towards north-east Slovakia. Two divisions of the Slovak Army officially tasked with supporting the Wehrmacht in reality were part of the plans for the Uprising, and were to make contact with the advancing Russians. The centre of gravity of the whole operation was the Banská Bystricka–Brezno–Zvolen triangle. The uprising began on 27 August, the towns were seized, and railway traffic was halted. In addition to equipment recovered from the Slovak Army, three armoured trains were built to compensate for the lack of armoured vehicles, since the majority of the Slovak tanks belonged to the two divisions in the East, which were immediately disarmed by the Germans. On 1 October, the insurgents deemed themselves to be the First Czechoslovak Army in Slovakia, in order to mark their return to their former country. On 18 October, the Germans counter-attacked from Hungary, and Banská Bystricka, the epicentre of the uprising, had to be evacuated on the 27th. The end of the uprising was notified to the government-in-exile in London the following day. The conflict then devolved into a guerrilla campaign which ended on 3 November.

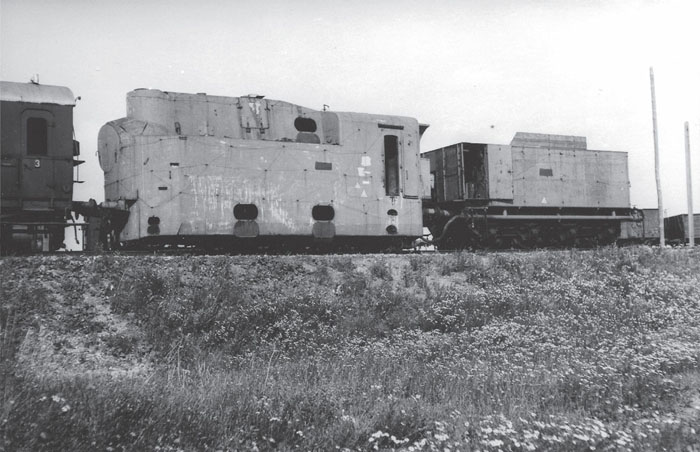

PZ 23 formed from ex-Czechoslovak units. The flat wagon which carried the Tatra trolley seen earlier is on the right of the photo, now used as the safety wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The three improvised armoured trains (IPV = Improvizovaný pancierový vlak) bearing the names of famous national personalities, Štefánik,6 Hurban7 and Mazaryk,8 were built in that order, in record time (five weeks in total) in the Zvolen workshops, under the direction of Colonel Štefan Čáni, with the technical assistance of Engineer Lieutenant Hugo Weinberger. Lacking recent experience, the technicians and workers turned to an old regulation laying down rules for the construction of improvised armoured trains. The faults shown up in the first train, in particular the insufficient armour protection, were corrected in Hurban and Masaryk, which were of superior construction. It is our opinion that the description of these trains as ‘improvised’ should by no means be considered pejorative, as they demonstrated practices found on contemporary production armoured trains.

Each armoured train was accompanied by a support train, with sleeping accommodation, sickbay, kitchen etc. The makeup of each train differed, but all were powered by a Class 320.2 steam engine, and included a leading gun wagon plus several artillery wagons mounting turrets from Czech LT-35 tanks.9

Armoured Train Štefánik10 was built between 4 and 18 September. Commanded first by Lieutenant Anton Tököly then Captain František Adam, its crew numbered seventy men. On 27 September it went into action on the line from Hronskà to Kremina, and on 4 October supported a counter-attack from Stará Kremnička. Its engine was hit, but following repairs it operated on the line from Zvolen to Kriváň up until the end of October. On the 25th, it left Zvolen in order to reach Ulmanka, where it found itself trapped. The crew destroyed the train’s armament and joined the partisans.

Armoured Train Hurban was begun on 25 September and completed in just eleven days. Under the command of Captain Martin Ďuriš Rubansky, it went into action on line from Hronská Dúbrava to Žiar nad Hronom up until 4 October, when it moved to the line from Banska Bystricá to Diviaky. On the same day, it fought German forces near Čremošné, where it suffered several casualties. At the end of October it had to be abandoned in Horný Harmanec Station.

Armoured Train Masaryk was completed on 14 October. It was the most sophisticated of the three units, and its engine had complete armour protection. The high-quality armour plates came from the Podbrezová steelworks. Under its commander Captain Jan Kukliš it operated on the line from Brezna to Červená Skala where it was damaged on 21 October. On the 24th, the engine was destroyed by a direct hit, and the commander, driver and fireman were killed. Beyond repair, it was towed to the tunnel at Horný Harmanec Station, where its crew destroyed its armament and joined the crew of Hurban. Captured when that town fell, both trains were sent to Milowitz for repairs before being shared out between SSZ Max and Moritz.

To celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), Utrecht Museum organised an exhibition on trains in warfare. For the occasion, Štefánik was restored and partly reconstructed. After having been one of the major attractions at the exhibition, it returned to Zvolen in September 2013.

One of the three armoured trains at the Zvolen workshops. The artillery wagons were built using as a base Type U coal wagons. The protection was formed from two sheets of wood each 5cm thick separated by 15cm of gravel ballast.

(Múzeum Slovenského nároného povstania, SNP)

The handing-over ceremony of Štefánik at the Zvolen workshops on 18 September 1944. Engineer Lieutenant Hugo Weinberger (codename ‘Velan’) is second from the right. The civilian in the centre is Engineer Ivan Víest, Director of the Railways of Slovakia, with Colonel Štefan Čáni immediately to his left.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

At the head of IPV I Štefánik is the 80mm vz 5/8 gun, seen during a halt at Viglas. The safety platform wagon is not coupled directly to the train, but is propelled by a timber beam.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

An overall view of IPV I Štefánik seen from in front, with its safety platform wagon, the leading cannon wagon, the two turret wagons armed with 37mm guns and the tail wagon.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

This shot of Štefánik and the photo on the right clearly show the difference between the tail wagon (with an embrasure for a 37mm gun) and the leading wagon with its large opening for the 8cm FK.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

The Class 320.2 steam engine of Štefánik. The initial camouflage tones were white, green and red-brown. Subsequently, all the trains would be repainted an overall green shade.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

Interior view of the infantry wagon of IPV I Štefánik, with one of the lateral 7/24 Schwarzlose machine guns.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

Štefánik in its overall green paint scheme under foliage camouflage, far more discrete than the original three-colour scheme.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

The chase gun mounted on all three trains (here we see IPV II Hurban) was an ex-Austro-Hungarian 8cm FK M 05 or 05/08, also used by the Wehrmacht during the Second World War. Thanks probably to the successive improvements included in each of the trains, the embrasure of Hurban is virtually closed by an armour plate which was not present on Štefánik.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

A fine view of the tail wagon of Hurban. The cupola does not appear to have observation slits, but it has a frame to mount a machine gun for close-in or anti-aircraft protection.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

An impressive view of Hurban wearing camouflage, with its crew disembarked. After the uprising was crushed, they would be forced to join the partisans in the mountains.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

Leading safety wagon of IPV III Masaryk in camouflage, which however fails to disguise the fact that the wagon sides are vertical.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

The main armament of the trains – seen here on Hurban – was an LT-35 tank turret armed with a 37mm gun and a co-axial 7.92mm machine gun. In Wehrmacht service, this tank was designated the PzKpfw 35 (t). Note in this photo the roof of the hull of the tank, enveloped in the armour protection which leaves only the hatches visible.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

The armoured steam engine of Masaryk seen in 1946, in one of the depots where all the equipment retrieved from the various wartime fronts was collected.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

Hurban restored during the post-war period. Note the cupola of the infantry wagon to the right.

(Photo: Múzeum SNP)

A monument to the Slovak National Uprising, in the form of a reconstruction of IPV I Štefánik at Zvolen with T-34/85 turrets altered to resemble those of PzKpfw 35(t)s.

(Photo: Fréderic Guelton)

In 1974 this medal was struck to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the uprising.

(Private Collection)

On 6 April 1945, the day after the liberation of Bratislava in Slovakia, a coalition government was established in Košice, and on 5 May Prague rose up and the Wehrmacht was driven out in the course of fighting which lasted until 11 May. A large quantity of German rolling stock was captured, including PZ 27, PZ 80 and PZ 81, the PZ (s.Sp trolleys) 205 and 206, including several heavy railcars, security train Moritz, PT 36 (Littorina) and several anti-aircraft trains. The latter units were put back into service and formed twelve improvised armoured trains. Two other armoured trains (ex-German vehicles) were activated in Prague and Milovice (Milowitz, the former Czechoslovak armoured train base). Lastly, Type BP 44 wagons were discovered at Česká Lipa during the reconquest of the Sudetenland at the end of the month. One complete ex-German armoured train, less certain elements, was put back into service and used up until 1948.

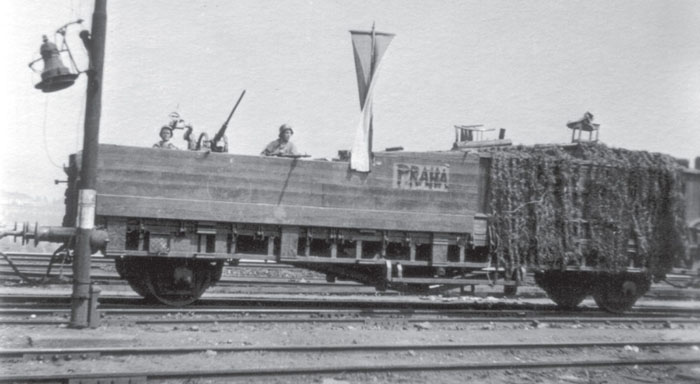

Armoured Train Praha (‘Prague’) made up from assorted wagons, including this hull of a Panzerjäger IV placed on a four-wheel mineral wagon.

(Photo: Tomáš Jakl Collection)

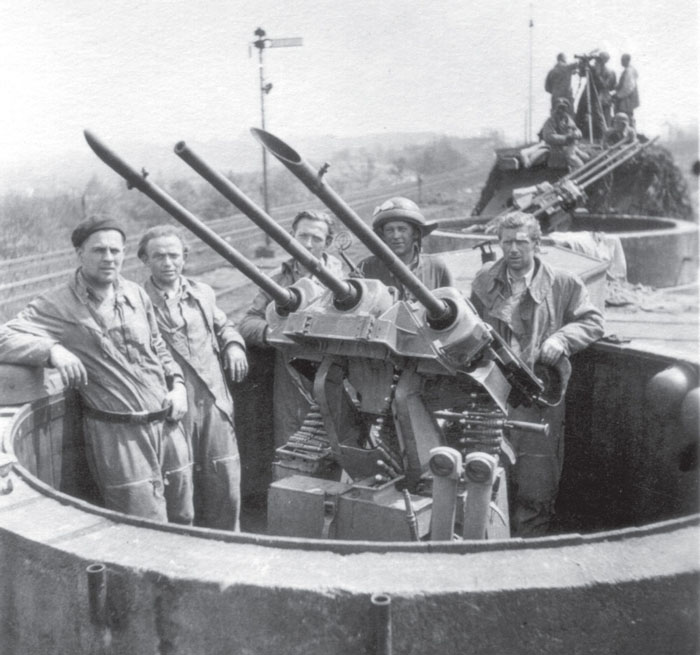

A fine view of the 20mm Flugabwehr-MG 151/20 (Drilling) mounted on the anti-aircraft trains in concrete tubs.

(Photo: Tomáš Jakl Collection)

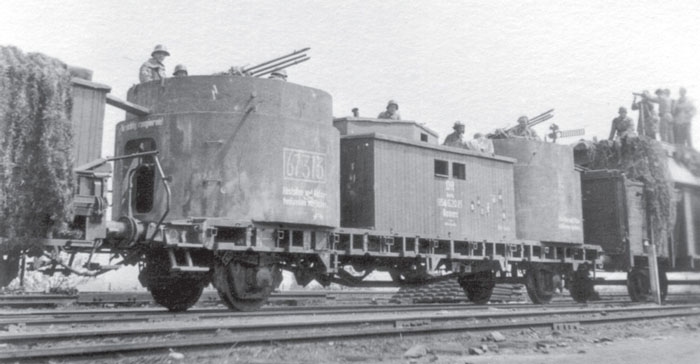

Complete view of an anti-aircraft wagon.

(Photo: Tomáš Jakl Collection)

Type 1 FlaK wagon, with the armour strengthened by the addition of a layer of wood.

(Photo: Tomáš Jakl Collection)

A completely improvised low-sided wagon, with earth piled up between a central compartment and the side planking. Notwithstanding, earth would be quite effective in stopping small-arms projectiles. Note the German helmets worn by the crew.

(Photo: Tomáš Jakl Collection)

Armoured Train Uhřiněves composed of various flak wagons grouped together in 1945. The engine is unarmoured.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

The new Czechoslovak Army included an Armoured Train Company in its establishment, created on 1 October 1945, based at Nymburg (modern Nymburk), and placed under the command of the 11th Tank Brigade. This company had two platoons. One platoon was comprised of armoured trains, with each unit organised as follows: one artillery wagon, two infantry wagons, two tank transporter wagons, command wagon, engine and a trolley. The other platoon was composed of reconnaissance trolleys, made up into rakes comprising a command wagon, PT 36, two artillery wagons, and three infantry wagons. In addition, an armoured train and a trolley intended for training were activated. With the addition of new armoured rolling stock, the Company became a Battalion in September 1946, with a separate command structure, support units and three companies:

– 1st Company (steam engines): Armoured Trains Benes, Masaryk, Štefánik and Svoboda.

– 2nd Company (petrol locotractors): Armoured Trains Pavlik, Stalin, Hurban and one armoured trolley.

– Reserve and Training Company: Armoured Train Orlik.

These trains included five artillery wagons with a 2cm Flakvierling but with different main turrets: one with a 10.5cm le.Fh 18, two PzKpfw IIs and two PzKpfw IVs. The tank transporter wagons carried LT vz.38 tanks (ex-PzKpfw 38 (t)). The remaining units were infantry, mortar and command wagons.

The Battalion was reorganised in Autumn 1949: the 2nd Company was based at Sopot (100km/ 63 miles to the south-east of Prague) while the 1st remained in Nymburg, these two centres bringing together all the armoured trains, which on this occasion lost their names and were thereafter referred to by numbers. However, the armoured train units were dissolved in 1954–5 and the rolling stock was scrapped, except for several infantry wagons used in a stationary role, notably by the Air Force.

Reduced to a propaganda weapon, these trains had not been able to play a decisive role in the battles of liberation which stressed the actions of the partisans and paratroops.

The elements of two Panzerzüg (s.Sp) formed a train which comprised three turret-equipped trolleys, a command trolley (with frame aerial) and an infantry trolley. Note the Czechoslovak flag on the side of the leading unit.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

This view shows the tool set of an infantry trolley, with the jack which is identical to that carried by tanks.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

The opposite view of a turreted trolley, to be able to compare the two ends. Here is the motor end, identifiable by the semi-spherical armoured domes.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

The command trolley, with its frame aerial.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

Note the lack of a coupling hook on this unit. Regretably, none of these vehicles have been preserved in a museum.

(Photo: VÚA-VHA)

SOURCES:

Archives:

SHD, boxes 17 N 629.

Múzeum Slovenského nároného povstania, Banská Bystrica.

Vojenský Ústředni Archív, Prague.

Vojenský historický ústav, Bratislava.

Books:

Catchpole, Paul, Steam and Rail in Slovakia (Chippenham: Locomotives International, 1998).

Hyot, Edwin P., The Army without a Country (New York: MacMillan Company, 1967).

Jakl, Tomáš, Panuš, Bernard, and Tintěra, Jiří, Czechoslovak Armored Cars in the First World War and Russian Civil War (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2015).

Janin, General, Ma Mission en Sibérie 1918-1920 (Paris : Payot, 1933).

Kliment, Charles K, and Francev, Vladimir, Czechoslovak Armoured Fighting Vehicles 1918-1948 (Atglen (PA): Schiffer Publishing, 1997).

Kmet, Ladislav, Povstalecké Pancierové Vlaky (Zvolen, Slovakia: self-published, 1999).

Lášek, Pavel, and Vanĕk, Jan, Obrn ná drezína TATRA T 18 (Prague: Corona, 2002).

Richet, Roger, Les émissions de la Légion Tchécoslovaque en Sibérie (1918-1920) (Bischwiller: L’échangiste universel, nd).

Rouquerol, Général J., L’Aventure de l’amiral Koltchak (Paris: Payot, 1929).

Uhrin, Marian, Pluk utocnej vozby v roke 1944 (Zvolen, Slovakia: Múzeum Slovenského Národného Povstania, 2013).

Journal articles:

‘Československé obrnĕné vlaky 1818 až 1939’, Železnice No 3/94 (1994), pp 23–6.

Chen, Edgar & Van Burskirk, Emily, ‘The Czech Legion’s Long Journey Home’, MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History Vol 13, No 2 (Winter 2001), pp 42–53.

Kudlicka, Bohumir, ‘Orlik Armoured Train of the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia’, The Tankograd Gazette No 15 (2002), pp 27–30. Militär-Wochenblatt, No 44 (1937), pp 2744–5.

‘Povstalecky improvizovany pancierovy vlak Stefanik’, Modelar Extra No 20 (June 2013), pp 37–49.

In 1948, the Czechoslovak authorities published this postcard, which tended to overlook the exploits of the Czech Legion in favour of the Reds, using a fictional portrayal of an armoured train.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

1. In Czech: Pancéřový vlak, or PV. Alternatively in Slovak; Obrnĕný vlak.

2. ‘Little Eagle’ in Czech, and also the name of a castle.

3. The stamp issue, known as ‘silhouettes’, was printed at Irkoutsk by printers Makusin and Posochin: 35,520 examples of the 50-kopeck yellow-green stamp were printed. The third issue (for the Yugoslavs) and the fourth series (commemorative, which appeared between October 1920 and March 1921) show slight variations in the design.

4. Heigl, Fritz, Taschenbuch des Tanks, Vol II p 577.

5. Caiti, Pierangelo, Atlante mondiale delle artiglierie: artiglierie ferroviarie e treni blindati (Parma: Ermanno Albertelli Editore 1974), p 25.

6. Milan Ratislav Štefánik (1880–1919), airman, Vice-President of the Czechoslovak National Council then War Minister, Slovak General.

7. Jozef Miloslav Hurban (1817–86), one of the leaders of the Slovak Uprising of 1848, Member of the Slovak National Council.

8. Tomáš Garrigue Mazaryk (1850–1937), President of the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris, then President of Czechoslovakia from 1920 to 1935.

9. Several LT-35 tanks were stationed in the Slovak zone on the partition of Czechoslovakia.

10. Štefánik and Hurban were popular subjects for photographers, and a comparison of the resulting images shows that often the captions were attributed in error, which means that it is not possible today to be absolutely certain of positively identifying either train.