At the beginning of the twentieth century, the German Army was no stranger to the armoured train, having had the chance to observe the French versions during the War of 1870–1, but despite the widespread reports of armoured trains during the Boer War, it took some time for the Germans to recognise the advantages this weapon could bring to them. Their country being sited at the heart of Europe, in time of war they would need to have the ability to rapidly move their forces between the various fronts. The only means of doing this was by the railway network, and therefore means had to be put in hand for its protection. A glance at a map showing the length of the front lines extending from the north to the south of Poland then on into the Ukraine, and the extent of the railway network inside Germany proper, would justify the deployment of armoured trains, the only force capable of intervening rapidly over the long distances involved, at a time when motor transport was neither fully developed nor highly regarded in military circles. Then during the Second World War, the armoured trains were the only effective means of countering the depredations of roaming bands of partisans. The German Army, with the bit between its teeth, wholeheartedly pursued the armoured train adventure, in the process continually perfecting or planning improvements up until the final defeat of the Third Reich.

Following the Boxer Rebellion, the foreign Legations in China drew up a co-ordinated defence plan, and at Tsingtao the Germans commissioned a small artillery train with two wagons mounting naval guns.

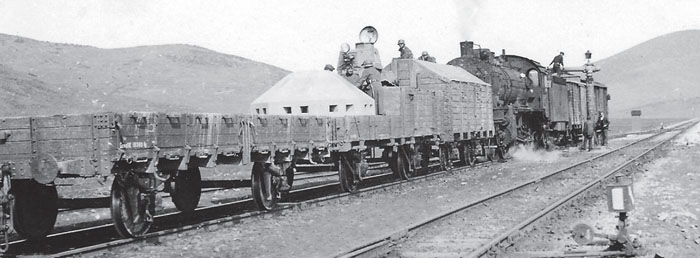

Postcard showing the German armoured train in China in 1900, with its two 8.8cm F.K. guns.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In 1904, the revolt of the Herero tribe in German South-West Africa led to the construction of a narrow-gauge armoured train. Under the command of a Lieutenant Bülow, the train was armoured at Waldau Station with corrugated iron sheets and sacks filled with earth; its armament comprised a 37mm revolver cannon from the landing detachment of the gunboat Habicht, plus the personal arms of the troops carried on board.

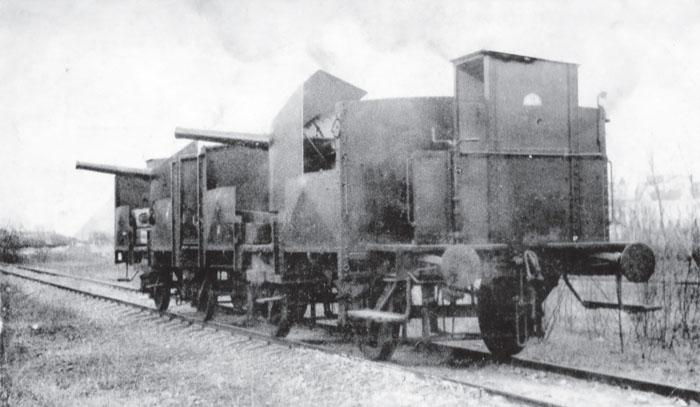

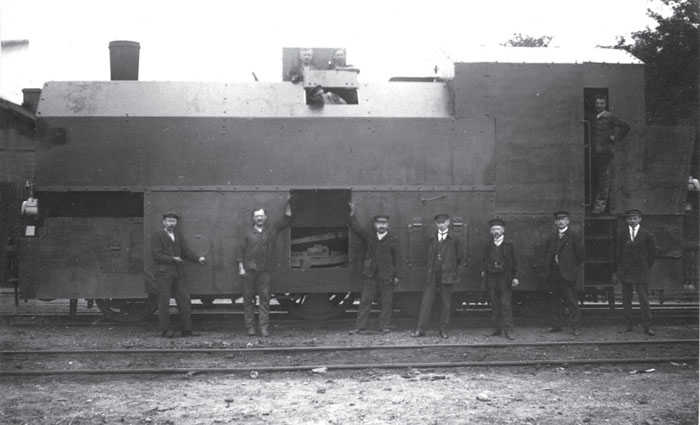

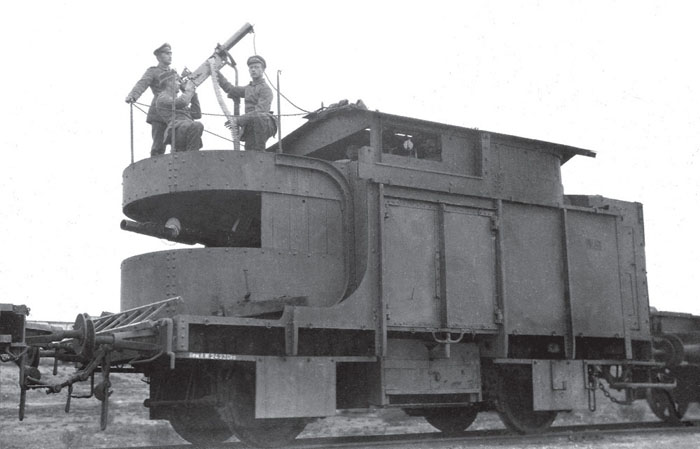

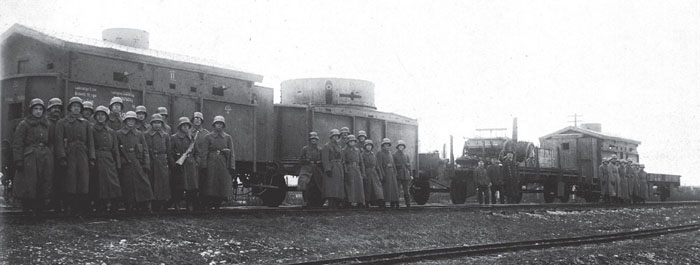

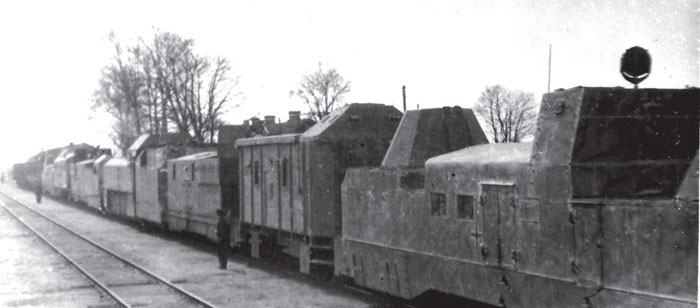

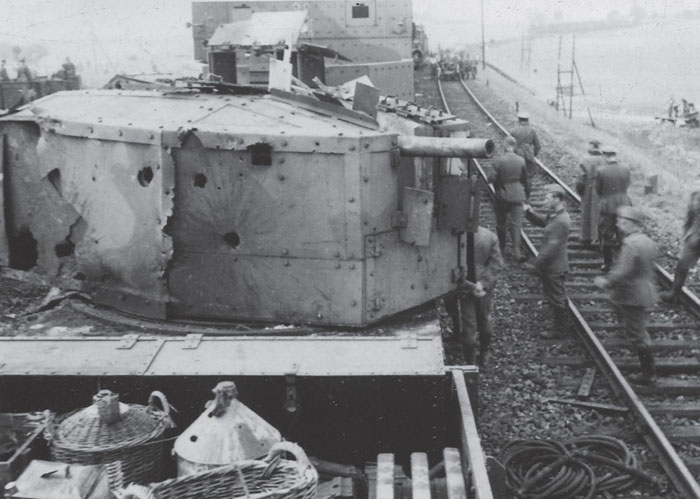

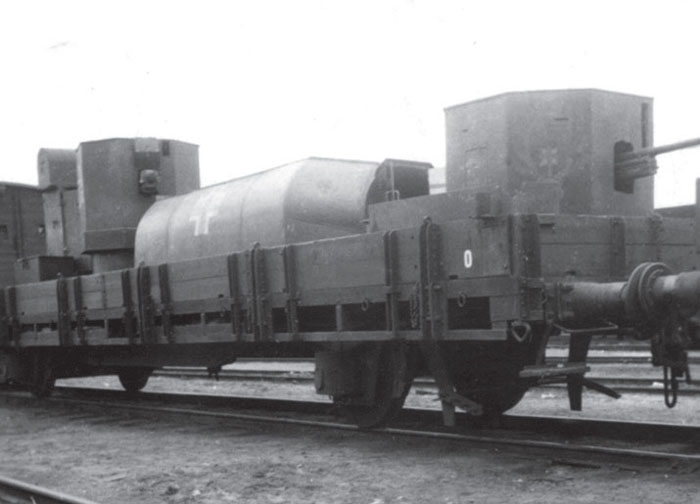

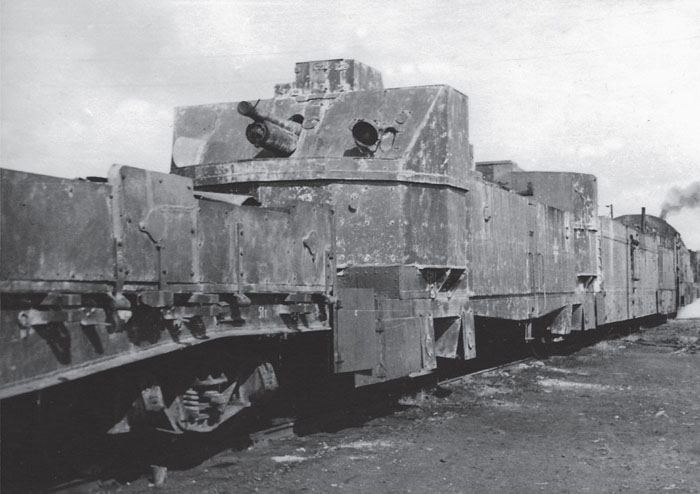

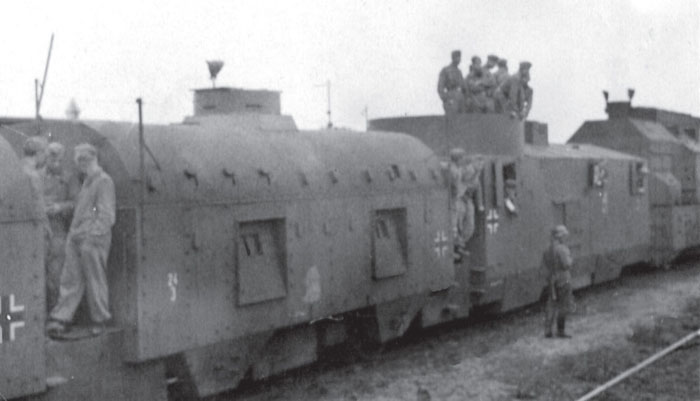

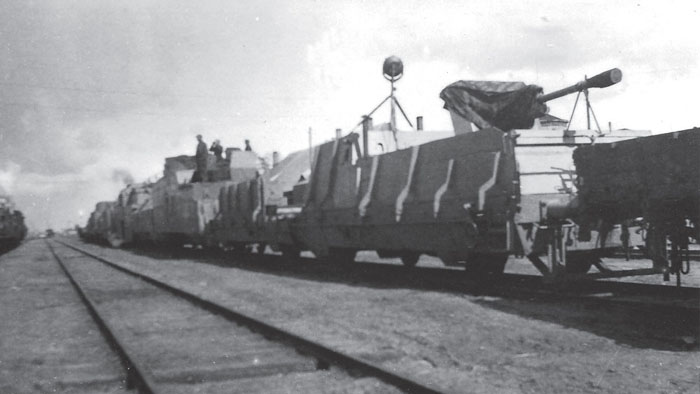

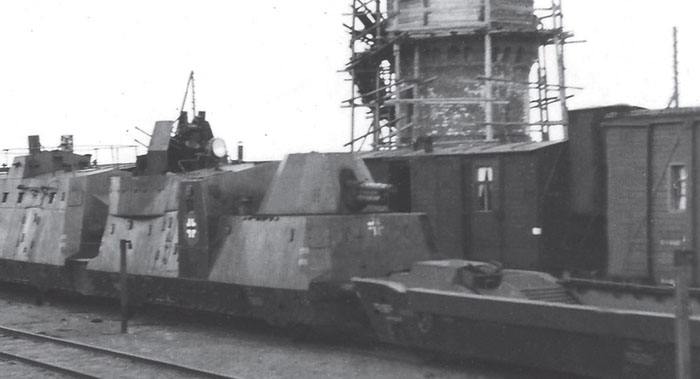

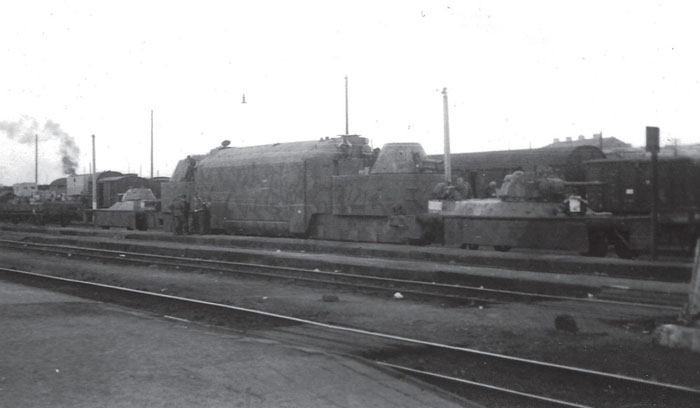

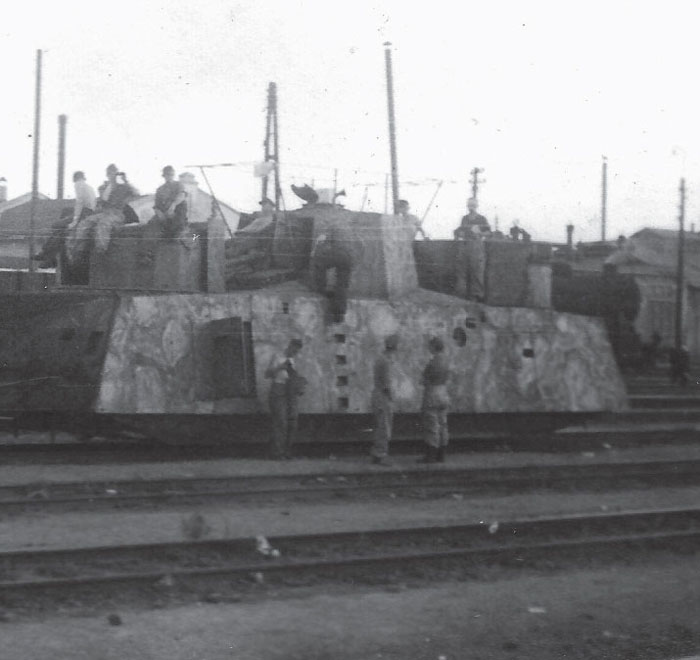

PZ III, one of the 1910-Type armoured trains seen at Lille in December 1914. The armoured wagons were converted from 40-tonne Type Omk(u) mineral wagons. One wagon was always equipped with an armoured command and observation tower, for the train commander.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

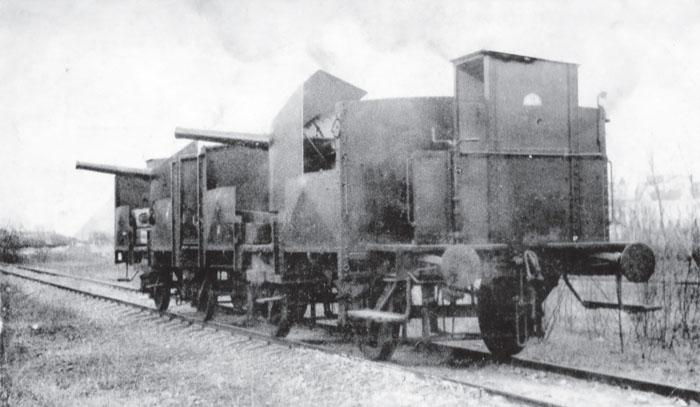

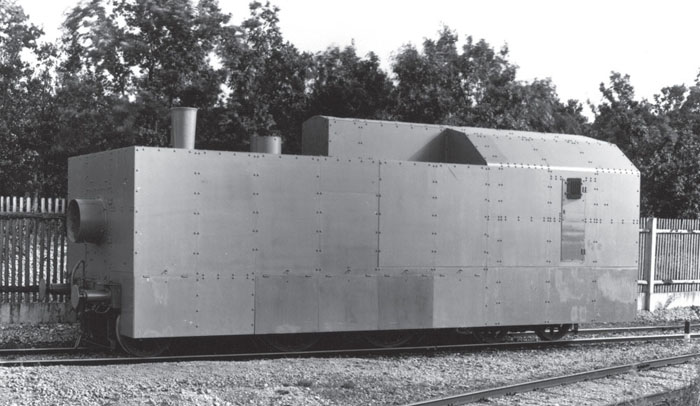

Armoured Class D XII engine built by Krauss at the turn of the century. It is not known whether this prototype was included in the 1910 Programme, but it had a relatively modern outline, even if the vertical arrangement of its armour plates betray its era.

(Photo: Krauss-Maffei)

Apart from these local improvisations, in 1910 official German documents foresaw the necessity of building armoured trains in the case of hostilities. Based on the observations of Count von Schlieffen who had studied the Boer War, the Army High Command placed orders for thirty-two armoured trains. However, the financial situation that year obliged them to reduce the order to just fourteen. By the outbreak of war, manoeuvres carried out with the first trains had given some idea of their value. The standard composition of each train was:

– an armoured engine positioned centrally, in general a Class T 9.3 but also Prussian Class G 7.1, or a Class T.3 (as allocated to PZ IX), etc.

– twelve wagons protected against small-arms fire.

– an observation tower fitted on one of the wagons.

The trains required twenty-four hours’ notice to prepare them for operations, crewed by railwaymen and soldiers from the regular army, up to a company in strength with four machine guns.

In Belgium several improvised trains were built and used by the right wing of the invading armies. In September 1914 an ‘intervention section’ was created, its mission being to fight franc-tireurs, cyclist troops and Allied cavalry. One armoured train, built by the Engineers, participated in these actions, one of which involved foiling a Belgian ‘phantom train’. If the employment of these armoured trains in Belgium could be qualified as satisfactory, on the other hand they were criticised for their thin armour and weak armament. The crews asked for internal telephones and searchlights. Beginning in November 1914 these defects were remedied, and in 1915 the number of trains reached the fourteen planned five years earlier. In that year, the front stabilised in the West, and the war of movement continued in the East. Out of the fourteen trains, seven were demobilised in 1916, and the seven others retained only their engineering crew members.

In 1916, Panzerzug I and II, which had been sent to Romania, received a new wagon armed with a 76.2mm Putilov 02 in an armoured casemate pivoting on a set of rollers.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari-DGEG Collection)

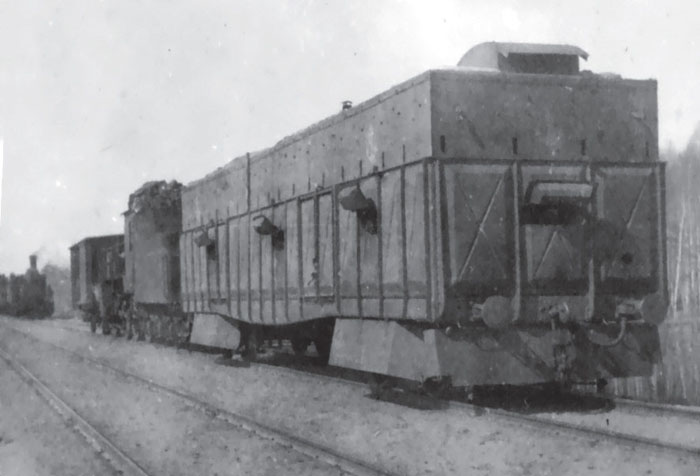

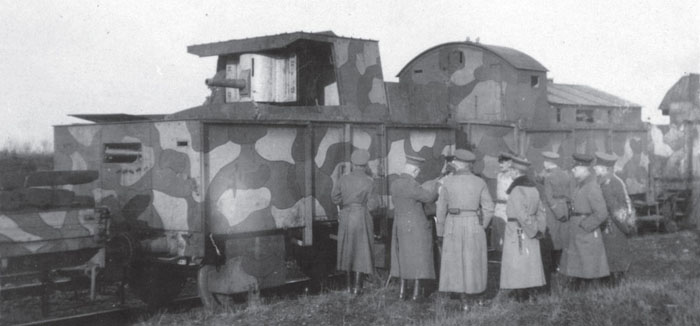

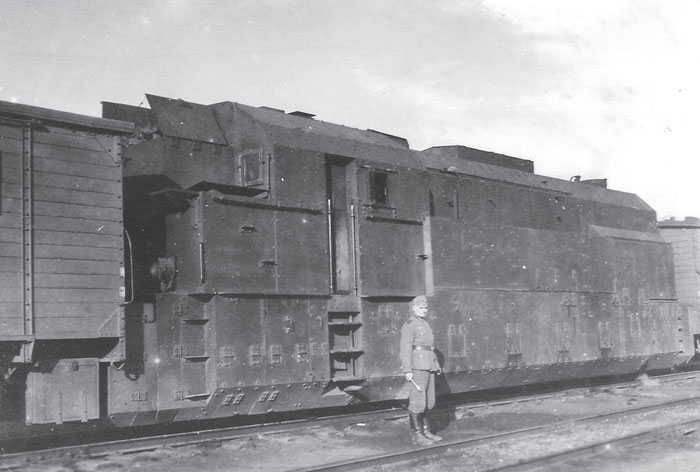

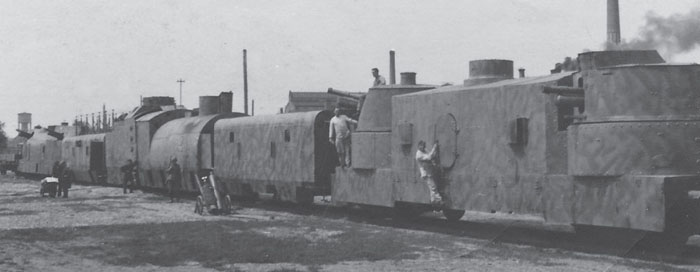

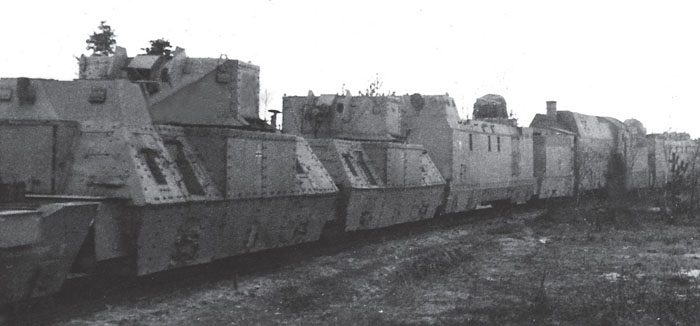

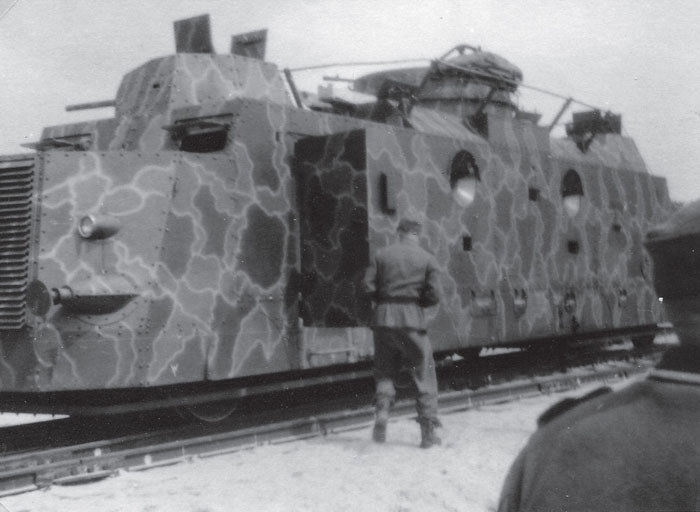

Between 1916 and 1918 a certain number of armoured trains were built to carry out different missions depending on the front where they were engaged. Some wagons now carried Gruson 53mm portable fortress turrets and others were roofed over.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari-DGEG Collection)

The Prussian Class T 9.3 was a tank engine, and the two additional unarmoured tenders were attached to increase its range. The practical speed of a Panzerzug in fighting configuration was in the range of 25–30km/h (15–18mph), whereas on the main lines, with the engine at the front, they could reach 60km/h (38mph).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

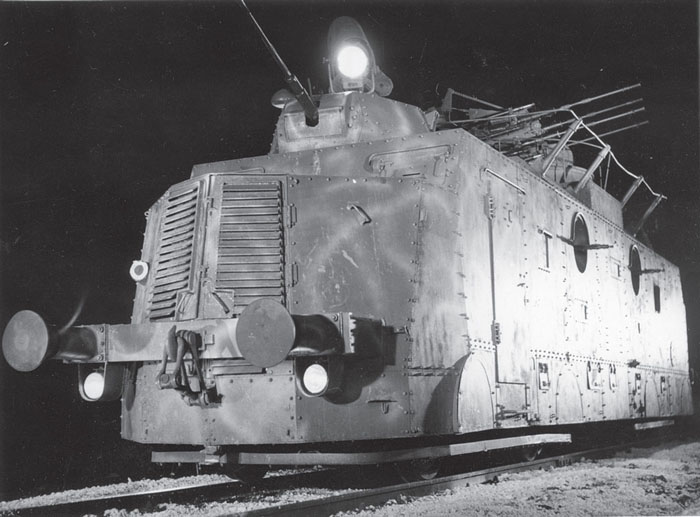

Photographed in Hamburg in January 1918, this Class T 9.3 engine is armoured overall, which distinguished it from the other standard engines. It was attached to either PZ II, V or VII.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

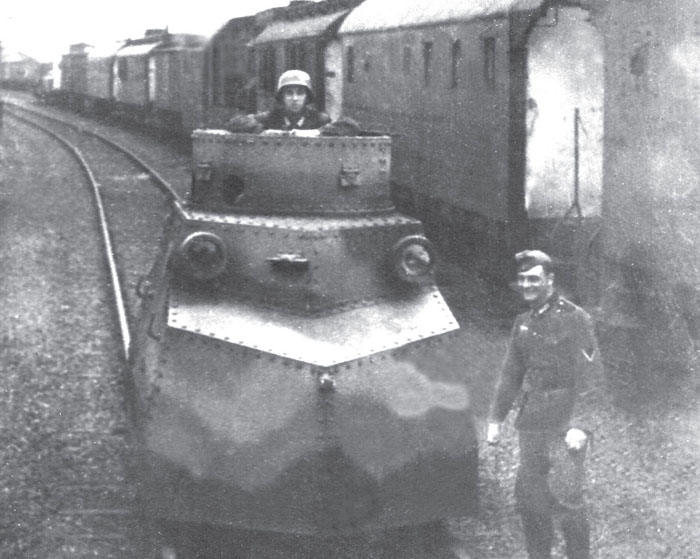

The leading wagon of PZ III, converted from a 20-tonne mineral wagon. This train would be renumbered as PZ 54 in March 1919. Note the 37mm revolver cannon with a 180-degree field of fire. It is fitted with a front armour plate and muzzle cover with retaining chain, just as on the smaller Maxim 08. Also note the lateral machine gun in the upper casemate. The anti-aircraft machine gun is a 7.62mm Maxim which was not part of the original armament of this train.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Patrol train on which elements of armour can be seen, such as on the engine cab, and the wagon sides, photographed on 19 June 1918 at Potiflis.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari-DGEG Collection)

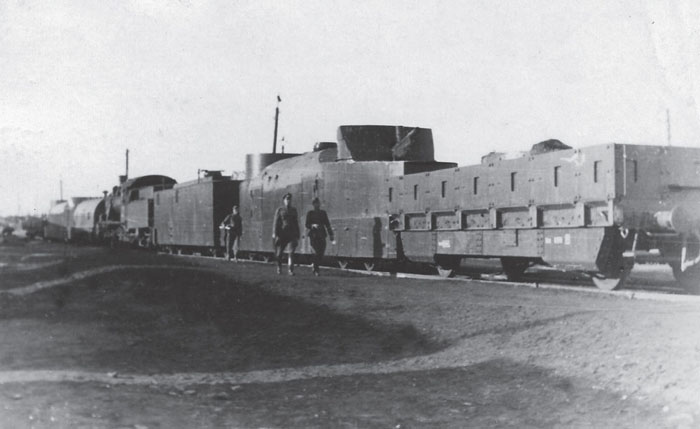

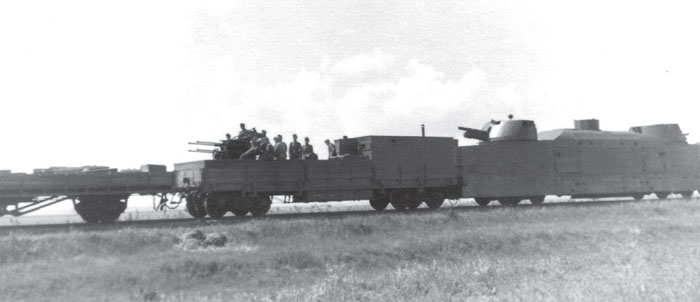

The German advance into the Ukraine involved building four trains for the Russian broad gauge, of differing design and with variable armour disposition, and also with the addition of captured wagons. Their armament was either German, using the 7.7cm field gun, or Russian with the 76.2mm.

On other fronts, armoured trains served in the German colonies: in the fighting in Cameroon against the French troops under General Dobell, a wagon was converted and used notably to defend the bridge over the Dibamda with its single machine gun. To the best of our knowledge, no photo of it was ever taken. In Palestine in 1918, German personnel of the Asien-Korps formed part of the crews of Turkish armoured trolleys (see the chapter on the Ottoman Empire). During the Finnish War of Independence, the Germans used only one train, captured from the Reds probably at Helsinki on or around 13 April 1918, armed with two Russian guns and four machine guns.

Armoured wagon captured during the advance into Russia and reused by German troops to the east of Gomel.

(Photo: Paul MalmassariDGEG Collection)

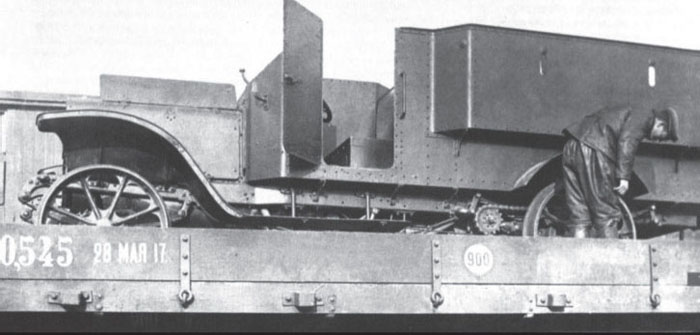

A rare vehicle during the First World War, this armoured trolley captured by the Russians is an armoured Daimler lorry converted for use on rails. Note the firing ports in the rear side plating.

(Photo: Wolfgang Sawodny Collection)

Humiliated by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, undermined by their defeat and declining social conditions at home, Germany was easily destabilised by the export of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Strikes, troubles and acts of sabotage multiplied, and led to the reactivation of the old armoured trains and the improvisation of many others. In late 1918, all the armoured trains, irrespective of the front where they were situated, were renumbered, beginning with 20 and ending in 55, plus several Roman numerals. The deployment of the trains became general in March 1919, when they operated principally in Halle, Magdeburg, Braunschweig, Leipzig and Munich. On the ‘Red’ side, in Leuna, where the factories were completely surrounded on 28 March 1919, a rudimentary armoured train was built by the revolutionaries, but it was captured intact.

The armoured train of the ‘Leuna Arbeiter’, converted from hopper wagons during the uprising inspired by Max Hoelz in Saxony between 23 and 29 March 1919. The industrial complex was recaptured by troops led by Colonel Bernhardt Graf von Paninski.

(Photo: Wolfgang Sawodny Collection)

The legend of Leuna was perpetuated by means of souvenirs such as a metal model train, and these plaques dated 1921, not 1919.

(Items: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The front part of PZ 45, seen in 1920. This train was built in March 1919 for the Lin. Kommando X (Stettin). From left to right: the machine-gun wagon (Type OmK) Breslau 55292; the artillery wagon (OmK) Essen 126 585, with its turret armed with a Krupp 8.8cm L/30 U-Boat gun on a C/16 mounting; a safety wagon; finally the machine-gun wagon (OmK) Cologne 62 455, with its armoured brakesman’s cabin. The trooper sixth from the left in the front rank has an MP 18 sub-machine gun, and to his left is a soldier with a holstered Artillery Luger.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

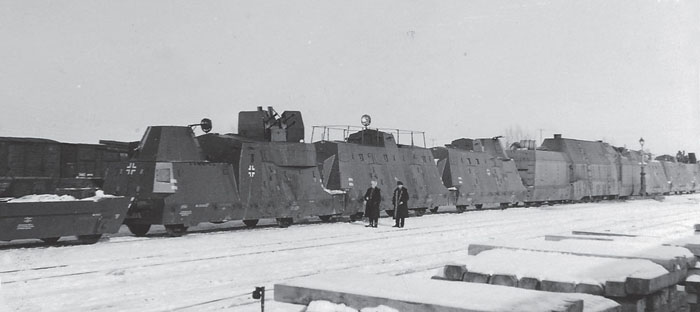

In February 1919, PZ VII (the ex-PZ XII of 1914) added two wagons from PZ II and operated in Lithuania. When the German troops withdrew in November 1919, the Lithuanians took over the train and renamed it Gediminas. Note the searchlight in its armoured tower on the left.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

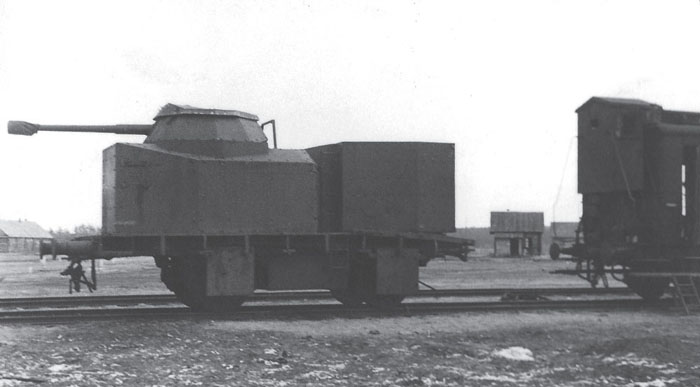

The Kapp Putsch in March 1920 involved six armoured trains in Berlin, numbered 30, 40, 46, 47, 55 and IV (seen here). The Gruson portable turrets were commonly used on armoured trains, but more usually inside a mineral wagon, and not mounted on a flat wagon as here.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 48 (built in Dresden) was broken up at the end of 1920 after having intervened at Chemnitz among other places. Its 5.7cm Maxim-Nordenfelt L/36.3 gun seems to have been lifted complete from an A7V tank.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The rear half of PZ 45. On the right, armoured Class T.9.3, Stettin 7308; then the assault troop wagon, Cassel 14680; mortar wagon (OmK) Berlin 28630 with its characteristic inclined armour protection; finally machine-gun wagon (OmK) Cologne 64303. Note the two MP 18s, and the portable MG 08/15 beside the soldier sixth from the right.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

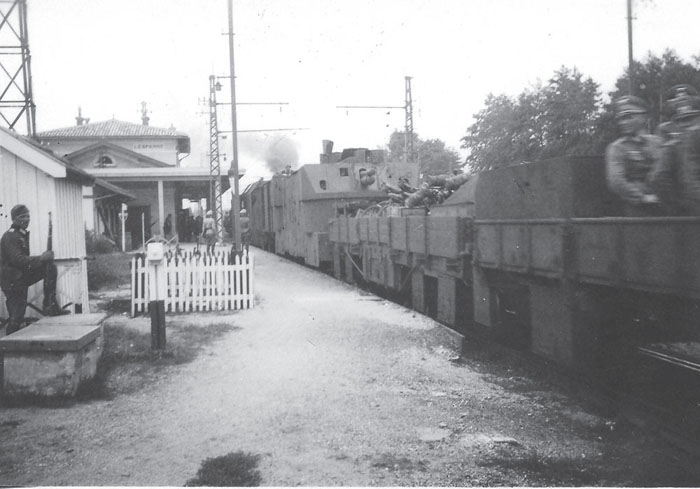

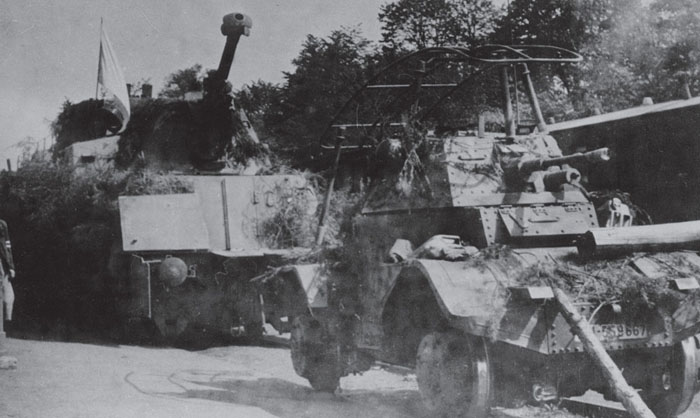

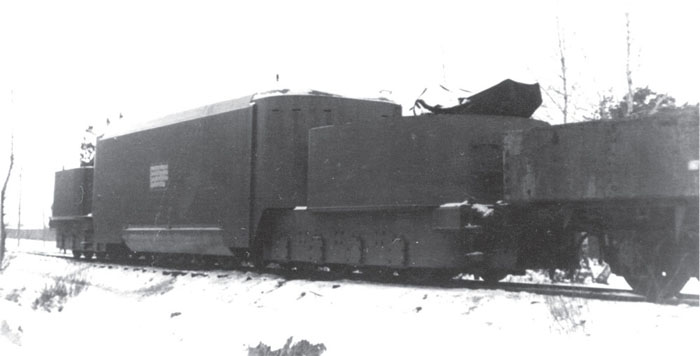

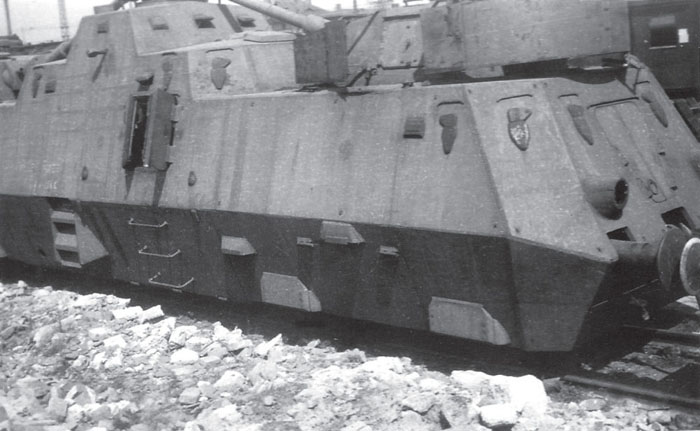

An example of the armoured trains used during the Silesian uprising of 1921: this is the train of the Rossbach Free Korps. Behind the Type Om wagon is an armoured wagon fitted with an observation tower. Note the black-white-red flag of the German Empire, still used by the Reichswehr even when the black-red-gold flag was the official version.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

These interventions were aimed at securing as much German territory as possible before the frontiers were definitively fixed. German troops were in action in the Baltic States, in Western Prussia and in Upper Silesia. Facing the three Polish uprisings, armoured trains were only deployed on the German side in the last two areas. In the Baltic States, a certain number of trains were also in action, including Panzerzug V in support of the Iron Division deployed in Riga in May 1919, and which was captured at Mittau.

For two years, Germany noted that armoured trains were not mentioned in the text of the Treaty of Versailles and demanded the right to keep some to maintain internal order and put down strikes. But on 5 May 1921, an ultimatum sent from London forced the German Government to accept ‘without reservation’ by letter of 20 May 1921 the handing over of all the trains. On 30 May 1925, the Inter-Allied Military Control Commission recorded having carried out the destruction of thirty-one armoured trains.

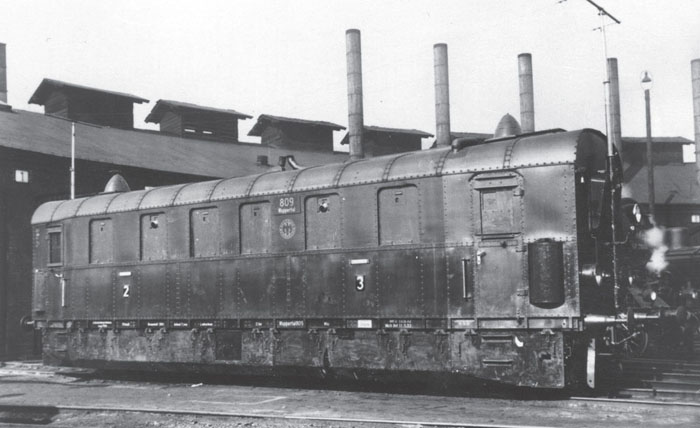

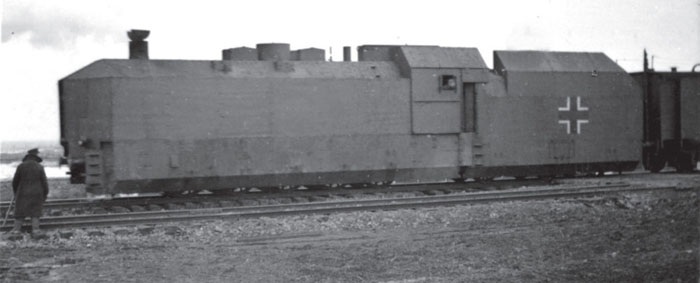

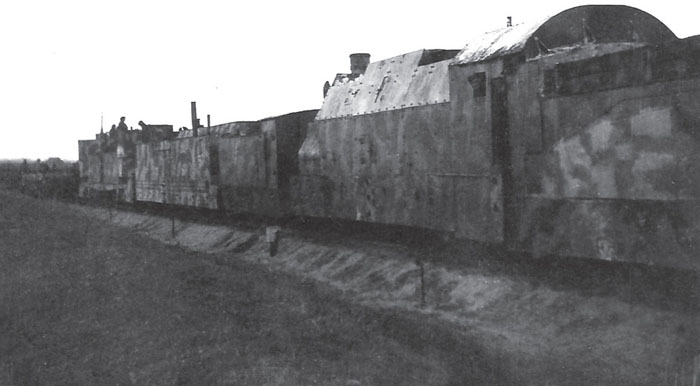

The period 1921 to 1939 saw the renaissance of the German armoured trains. Even if the Reichswehr (which existed from March 1919 to March 1935) had no armoured trains, the Reichsbahn possessed twenty-two track security trains, which would form the backbone of the future Panzerzug. However, according to the Railway Department (Section 5) of the Army High Command, these trains were in poor shape, and only by amalgamating their individual rakes could they constitute ‘two trains which could actually be used’. Hauled by unarmoured Class BR57 or BR93 engines, the wagons were simple units reinforced with sleepers, or with concrete poured between two layers of wood. The first military armoured trains (Panzerzug 1 to 4, 6 and 7) were created from these units, under the rearmament programmes launched in 1935, but Section 5 did not accord them a high priority. In fact, the High Command thought these trains could be used to cover a withdrawal and that they would be expendable. For wartime operations they preferred armoured railcars armed with artillery and machine guns. Thus it was that during this intermediate period five Type VT railcars (Nos 807 to 811) were armoured, and at least one road-rail vehicle was the subject of a study based on the Schupo-Sonderwagen 21 from Daimler.

Wuppertal’s armoured railcar No VT 809. The increase in weight required the installation of an extra central axle. Note the observation cupolas at each end of the roof and the wire of the radio antenna.

(Photo: BA)

Security train based in Munich, the future PZ 3, with its Type G vans armoured internally, and its radio masts deployed. Only the engine has overall armour. Note the observation cupola on the first van.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

As military operations became imminent, on 23 July 1938 the seven Bahnschtzzug2 (security trains) were reactivated. However, only four of them (Nos 3, 4, 6 and 7) were selected for combat operations on the basis of their offensive and defensive qualities and equipped accordingly, the others (Nos 1, 2 and 5) being reserved for railway security duties behind the front lines.

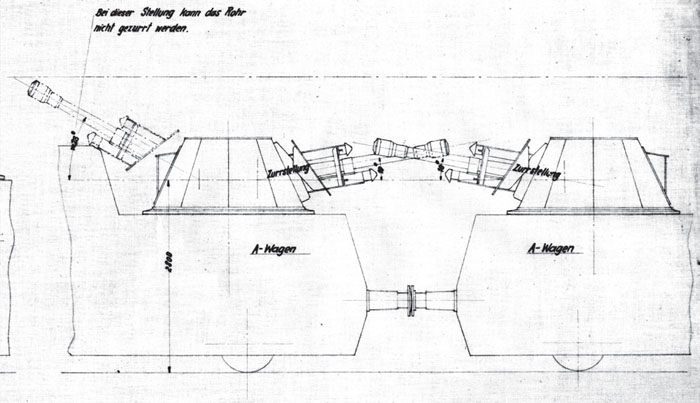

This project begun on 13 December 1940 envisaged an armoured train comprising an armoured railcar capable of being used singly or coupled to other units, able to fight on road or rail, with the conversion even under fire taking only a few seconds. In addition, the armoured tank-transporter wagons would be self-propelled. In view of the complexity of the project, it was envisaged that production of the various units would extend over a period of time: as an urgent measure firstly the Type Omm flat wagons for carrying tanks, then the armouring of the locomotive, next the special wagons (auxiliary units, assault troop carrier, kitchen, infirmary), finally the conversion of all the wagons to self-propelled units. In actual fact only the Type Omm wagons would be built in 1941, and which were added to PZ 26-31.

Also launched on 13 December 1940, this project included seven armoured wagons powered by a 1260hp diesel locomotive, which was capable of moving 600 tonnes at up to 50km/h (31mph) on the level. The train was to comprise: a command wagon, an assault section wagon, three tank-transporter wagons and two safety wagons, the whole being capable of running on standard and Russian broad gauge; the command wagon and/or any of the other armoured wagons was to be capable of independent operation. The tank-transporter wagons should be capable of unloading their tank in ten minutes and of re-embarking it in fifteen. The armament was to comprise 7.5cm guns in turrets, 2cm Flakvierling and machine guns. The diesel locomotive was to have been built by L-H-W and the rest by Berliner Maschinen Bau A.G. The design study was to have been finalised by September 1942 with the first train available by the Summer of 1943. The project was never started, and the designs were probably absorbed into those of Panzerzug BP 42/44 and PT 16.

As the Panzerzug 1941 and SP 42 were not begun, in January 1942 the firm of Linke-Hofmann in Breslau was commissioned to build new armoured trains under the designation ‘BP 42’ (Behelfmässischer Panzerzug or ‘makeshift armoured train’, which suggests that this was to be a temporary solution), while Krupp was to fit the armour to the Class BR57 engines. The technical specifications were laid down in document K.St.N./K.A.N. 1169x3 dated 17 August 1942. This document standardised the composition of the armoured trains along with their armament. Thus, in addition to those trains built in 1942, the previous trains would be brought up to the same standard at each major reconstruction.

The armament planned for these units was to be a 76.2mm F.K.-295/1(r) and a 2cm Flakvierling for the artillery wagons (AWagen), a 10.5cm le.F.H.14/19(p) for the gun wagon (G-Wagen), and machine guns. The PzKpfw 38(t) tanks to be carried should be capable of combat off the train. The armour protection was to be 30mm thick. Despite shortcomings in the armour thickness, for lack of suitable materials, the remainder of the armoured train corresponded to the standard laid down.

Combat experience quickly showed that the four 76.2mm or 10.5cm calibre guns were incapable of successfully engaging Russian tanks, and an expedient resorted to at the front was the mounting of the hull of a tank (PzKpfw IV or T-34) in order to use its turret armament. In parallel, a design study initiated by L-H-W resulted in the construction of a ‘Panzerjägerwagen’ (tank destroyer wagon) in 1944, equipped with the turret of a PzKpfw IV armed with a 7.5cm L/48 gun. On 6 September 1944 the Army High Command ordered the construction of 12 PZ of a new type to be designated BP 44, which complied with these latest standards. In parallel with the coupling of two Panzerjägerwagen at each end of the train, the 10.5cm guns were replaced with 15cm le FH 18 howitzers.

In use, the BP 42 and BP 44, which represented the high point of the art, proved themselves highly efficient at maintaining the morale of troops fighting bands of partisans, but suffered from the weaknesses due to their conservative design: steam power, their extreme length, lack of flexibility and limited armour protection. As a result, in August 1944 a front-line officer proposed an armoured train comprising a diesel locomotive coupled in the centre of two heavily-armoured wagons and six Panzerjägerwagen.

10.5cm guns on the G-Wagen (top) and the A-Wagen (bottom) of the BP 44-type trains.

(Drawings: Official German Military Archives)

The trains in this category were not expected to comply with any existing standards apart from those required by combat in their particular locality. They were the improvised trains (‘Behelfmässiger Panzerzug’) which would be used particularly in Yugoslavia, in Italy and in Eastern Europe. Under the order dated 12 July 1943 they took on the designation of ‘Streckenschützzug’ (SSZ or track protection train).

The official German classification system laid down the following list:

– Gleiskraftträder = unarmoured self-propelled rail vehicle.

– Eisenbahnpanzerzug (leichter Spähwagen) = light reconnaissance vehicle.

– Eisenbahnpanzerzug (schwerer Spähwagen) = heavy reconnaissance vehicle.

– Eisenbahnpanzerzug-Triebwagen = armoured railcar.

– Panzerjäger-Triebwagen = tank destroyer railcar.

Trains were made up of a rake of these trolleys as follows: two sets of five trolleys (le.SP built by Steyr) or eleven trolleys (s.Sp also built by Steyr), alternating armed trolleys, command trolleys with radio antenna and trolleys with a tank turret. The train thus arranged was completed at each end by a Panzerjägerwagen slightly different to those used with the BP 42 and BP 44 type trains.

The organisation of the Eisb.Panz.Zg (le.Sp) was laid down in K.St.N. 1170P dated 1 October 1943, that of the Eisb.Panz.Zg (s.Sp) in K.St.N. 1170x dated 1 August 1944, that of the Pz. Triebwagen Littorina by K.St.N. 1170i dated 10 April 1944, and finally that for the Pz. Triebwagen ‘a’ and the Panzerjäger Triebwagen by K.St.N. 1170a dated 1 January 1945.

Near the end of the war a road-rail vehicle project was studied, but the Nazi defeat put an end to it before any production vehicles resulted.

Initially the armoured trains were under the control of the Railway Troops, up until 9 August 1941. On that date, with the attachment of Rapid Deployment Troops, it proved necessary to concentrate technical and tactical information in a single command centre, to permit their rapid deployment under a technician with intimate knowledge of armoured trains: the Armoured Trains Commanding Officer attached to the Army High Command, a function which remained in force up until March 1945. On 1 April 1942, the armoured train force, which by then counted some 2000 men drawn from different units, was grouped together administratively under the control of a new centre created at Warschau-Rembertow (the Ersatz-Abteilung für Eisenbahn-Panzerzug-WarschauRembertow, or WK I). A further reorganisation came into effect on 1 April 1943, the armoured trains henceforth becoming an integral part of the ‘Panzerwaffe’4 instead of the Rapid Deployment Troops. In late 1944, the Armoured Trains Centre at Warsaw-Rembertow was transferred to Millowitz in the Protectorate of Bohemia.

PZ 1 was created on 26 August 1939. It did not take part in the Polish Campaign and in 1940 was in the region of Düsseldorf on guard duty facing the West. It advanced into Holland on 10 May 1940 in the direction of Gennep, then Mill, where it was knocked out by a mine. It was repaired in Darmstadt, where it received wagons from the demobilised PZ 5. In 1941, it participated in the invasion of the Northern USSR, with the 4th Panzergruppe in the direction of Leningrad, then operated on the Central Front around Vitbesk and Smolensk. After suffering major damage on 28 November 1943, it was completely rebuilt in Königsberg to the new standards. Up until early 1944 it remained with Army Group Centre, notably carrying out security missions as part of the 221st Sicherung-Division based at Minsk. It was destroyed by its crew on 27 June 1944 during the Soviet summer offensive.

PZ 1 derailed at Mill on 10 May 1940. The armour on the engine has been deformed by the impact with the leading wagons. Note that all but one of the armoured wagons are converted from passenger coaches.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Even if the engine is still the same, most of the wagons have been replaced by captured Soviet wagons. By comparison with the BP 42 production versions, the number of field artillery and anti-aircraft pieces remains the same, but distributed differently. The command wagon with its armoured casemate is the original GWagen which has been modified.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Close-up of the 2cm Flakvierling 38 mounting. All the trains brought up to the BP 42 standard had the same overall outline.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 1 (on the right) inherited a Polish Tatra T-18 trolley as proved by the camouflage scheme (see the chapters on Poland and Czechoslovakia).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

BR93 058 was the engine attached to PZ 2 ever since it was formed as the security train for Stettin. In 1945, the engine was the motive power for PZ 78.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 2 seen from the rear. The original 75mm gun is still in place in the ex-Czech wagon but the turret behind it has been rearmed with a 2cm Flak.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The casemate destroyed at Könitz, with the 7.5cm F.K. M16 in the revolving turret.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Shortly after it was activated in July 1938 PZ 2 participated in the occupation of the Sudetenland. It was next in action during the invasion of Russia. Between the Winter of 1941/42 and June 1944 it was under the orders of Army Group Centre in the region of Smolensk, then to the north-west of Kovel where it carried out anti-partisan security missions and troop transportation. It was updated to BP 42/44 standard, then was withdrawn from service in November 1944.

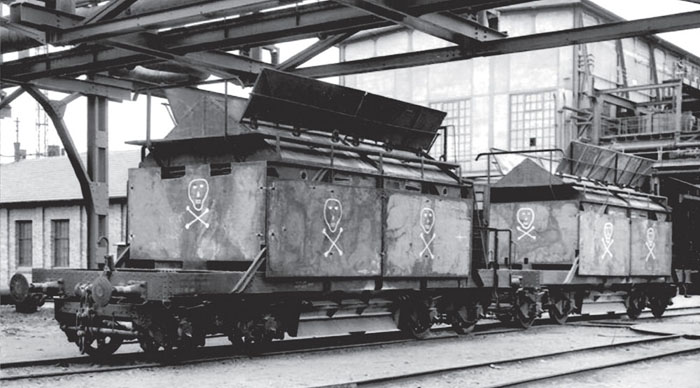

PZ 3 is one of the rare examples where it is possible to illustrate each phase of its career, which began prior to 1938 and ended in October 1944. PZ 2 (the former BSZ München) was reactivated on 23 July 1938 and placed under the orders of the General Kommando, VII.Armee-Korps in Munich. An SdKfz 231 railway reconnaissance vehicle was attached to it.5 After 15 March 1939, when Germany invaded what was left of Czechoslovakia, PZ 3 returned to Brno passing through Austria. PZ 3 along with PZ 4 and 7 were in at the very start of the Second World War, going into action on 1 September 1939.6 A direct hit from a Polish anti-tank gun destroyed the command turret, killing Lieutenant Euen, the train commander, and his second-in-command Lieutenant Zetter immediately took over. Withdrawing under fire, the train was stopped by a demolished bridge, whereupon Polish shells caused serious damage, destroying the leading wagon, setting fire to the wagons behind it, and knocking the train out of action. During subsequent repairs, the interior armour protection was enhanced and the destroyed turret replaced by a fixed casemate with an embrasure allowing a degree of training for the gun.

Following repairs, PZ 3 was sent to Lublin. On 10 May 1940 it crossed the Dutch frontier. But it could not fulfil its mission to seize the bridges over the Ijssel as the Dutch had sufficient time to blow them up. It then passed through the Halberstadt workshops where the wagons at each end were fitted with a turret from the abandoned BN10H programme for an anti-tank halftrack, mounting a 7.5cm L/40.8 gun, an elevated command/observation casemate and an anti-aircraft position (2cm Flak7 in a tub, replaced in March 1941 by a 2cm Flakvierling8). To compensate for the subsequent increase in weight, a third axle was added centrally. PZ 3 thus became one of the better armed and protected of the first-generation trains.

The leading artillery wagon of PZ 3 after leaving the repair shops in Danzig. Note the new command casemate and the replacement 7.7cm F.K. 96 gun in its fixed casemate. The painted death’s-head is temporary.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

SdKfz 231 armed with a 2cm cannon knocked out by anti-tank shells in front of the Ijssel bridges. This was the trolley attached to PZ 3, but the registration plate is a mystery, denoting a Bavarian Police unit.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari-Regenberg Collection)

PZ 3 at Veliki Luki in December 1942. The quadruple Flak mounting is clearly visible.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

For Operation ‘Barbarossa’, PZ 3 crossed the River Bug on the night of 22 June 1941 heading for Grajevo. In late October 1941, it returned to Königsberg for repairs. On 1 April 1942, it was blown up by a mine, and in the fighting which followed eight partisans were killed. On the 22nd, a remote-controlled mine destroyed an artillery wagon and derailed the two following wagons,9 leaving seven dead and nine wounded among the crew.

Following serious battle damage in May, PZ 3 was sent for repair, then between 11 September 1943 and 12 July 1944 it was unavailable, being modernised to BP 42 standards in the Königshütte workshops in Upper Silesia (K.st.n./K.A.N. 1169x). The day after it left the workshops, the Russians launched an offensive towards the Baltic in the Dünaburg-Rositten zone, and on 24 July PZ 3 and PZ 21 counter-attacked at Kowno. On 1 August, a few kilometres after starting a mission, PZ 3 was derailed, and had to return for repairs.

A rare photo: the forward gun wagon was literally cut in two by a mine at Newel on 22 April 1942 and was recovered later, in this unusual configuration.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

One of the few photos of PZ 3 in its final configuration, conforming to K.st.n./K.A.N. 1169x. From right to left, the G-Wagen armed with a 10cm le.F.H. 19(p), then the K-Wagen, and finally the A-Wagen with its 2cm Flakvierling 38.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

One of the non-motorised Panzerjägerwagen of PZ 3. They were not equipped with Schürzen nor hull up-armouring. On the left is the tank-transporter wagon. This arrangement of these two wagons back-to-back is very unusual.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The ambush at Kowno in July 1944, where PZ 3 was derailed. Note the original form of the G-Wagen, and one can just make out the Flakvierling wagon in the background. It would seem that this view and the previous one are the last-known photos of PZ 3.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

An impressive view of the engine from PZ 4, with its virtually integral armour, notably in the smokebox area which has streamlined armour protection.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This wagon, which is characteristic of PZ 4, is armed with a 3.7cm in the front turret (later replaced by a 4.7cm Pak) and a 7.5cm infantry gun in the rear turret, followed by an armoured rangefinder position. The semi-circular centre section is an ammunition shelter.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

On 5 October 1944 the Russians attacked the front of the Third Panzer Army and cut the German forces in two when they reached the Baltic. On 10 October 1944, the train was cut off by Russian tanks and had to be sabotaged by its crew.

PZ 4 was put into service on 11 August 1939. During the Winter of 1941/42, PZ 4 was in the south of Russia in the region of Dniepropetrovsk. Between April and June 1944 it was under repair, then in December 1944 it no longer appeared in the active list, its units being broken up. Its number was passed to a new train.

Entering service at the same time as the other trains operated by the Reichsbahn, PZ 5 crossed into Poland on 15 September 1939, then from the 20th carried out security patrols around Lvov during the discussions on the demarcation line between the Russians and the Germans. It was readied for the campaign against the Dutch in which it was to support commandos disguised as Dutch soldiers. On 10 May it was halted by the destruction of the bridge over the Ijssel and was severely damaged by Dutch anti-tank guns. It was broken up in June 1940 and its wagons were transferred to PZ 1.

PZ 6 was formed on 10 July 1939, and although incomplete, contributed to the capture of the town of Grajewo in Poland. Between 3 and 18 October 1939, it was in the Königsberg workshops being completed. It participated in the invasion of Holland but was blocked by a swing bridge being left open, and it then returned to Germany. During the Winter of 1941/42, it took part in ‘Barbarossa’ in Latvia then in Estonia, and finally in the region around Novgorod. Repaired after suffering serious damage, it was sent to Croatia. It was never brought up to BP 42 standards, and was destroyed in Serbia on 1 October 1944.

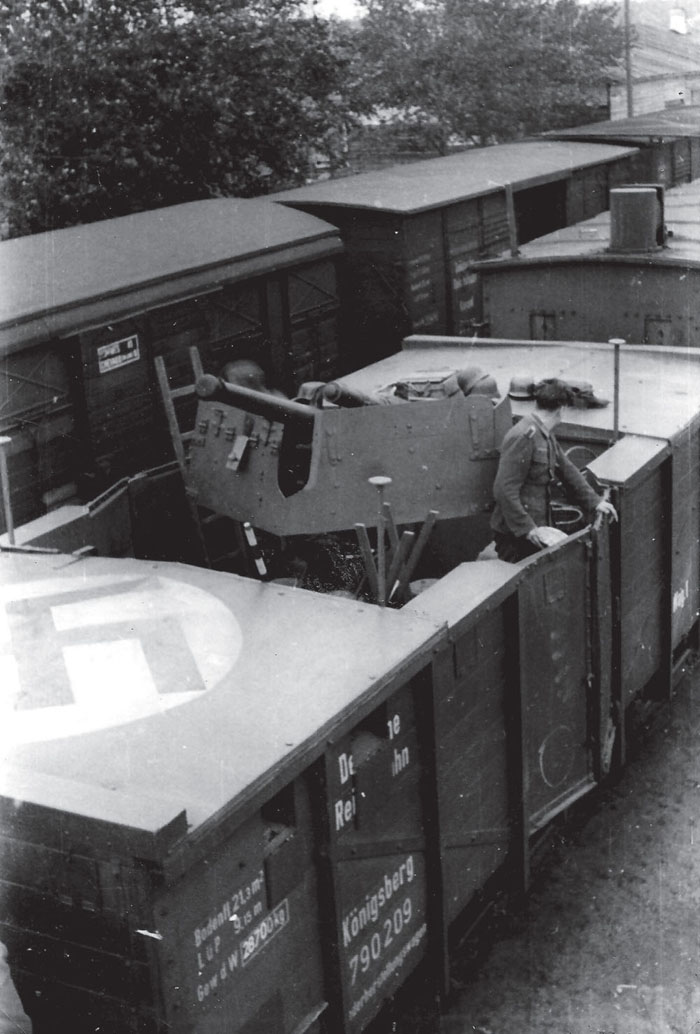

A rare view from above of the artillery position in the Type O wagon added after the Polish campaign, with the swastika added for aerial recognition. The gun appears to be a 7.5cm naval gun. Note the firing embrasures on the next wagon which seem to be useless in this configuration but which would have been used if the wagon was at the head or tail of the rake.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

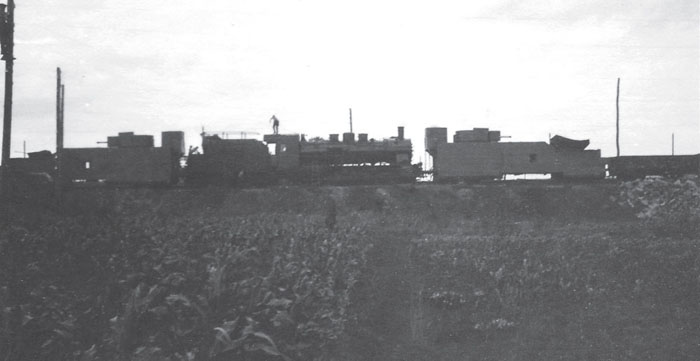

An overall view of the complete train, which shows its rough-and-ready external appearance, even though the armour was effective against small-arms. But the absence of heavy guns and howitzers soon brought about improvised solutions by adding wagons. At the rear of the train is just visible one of the ex-Soviet MBV-2 railcars used as artillery wagons since the Autumn of 1942.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 7 was created on 1 August 1939. It participated in the Polish campaign, then was used for security duties around Warsaw. On 8 March 1941 it was reinforced by 2cm Flak 38 mountings. In November, it participated in the invasion of the USSR (but on standard-gauge lines), then it returned to Germany for repairs. It returned to Russia and fought as part of Heeres-Gruppe Süd in the Kovel region. In June 1944, it was at the Warschau-Rembertow centre for modernisation, and was withdrawn from service in late 1944.

One half of PZ 7 probably being used as an artillery battery, profiting from the height of the line. The field gun is a 76.2mm F.K.295/1(r). One must suppose that the other half of the train is not far away.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Created on 26 November 1941, PZ 10 was divided into two combat trains, Kampfzug I (one howitzer, two flak mountings, one anti-tank gun, two 10cm field guns and nineteen machine guns, from PP 53 Śmiały) and II (one flak mounting, one anti-tank gun, four 7.5cm and 10cm field guns and nineteen machine guns, from PP 51 Marszalek). The wagons were ex-Polish, adapted for the broad gauge. After entering the USSR, it moved to the Kiev region and became part of Army Group South up until early 1944. During this period it covered the retreat of the German forces after the defeat at Stalingrad. During operations near Sarny-Kovel, PZ 10a participated in the breakout from the Russian encirclement of that town, was heavily damaged but escaped. Intended to be repaired at Rembertow, it underwent an artillery bombardment in the second half of April. Its crew was therefore transferred to the ground troops and PZ 10 was abandoned.

PZ 10 as it appeared between June 1942 and March 1944. The infantry wagon came from PZ 29. Between the ex-Polish wagon from Śmiały and the engine is an ex-Soviet wagon Type PL 35 or 37. On the far side of the engine is the infantry wagon from Bartosz Głowacki.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The ex-Soviet DTR trolley, used by PZ 10 as an armoured wagon. It had previously been used as a self-propelled reconnaissance vehicle.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

When PZ 10 was separated into PZ 10a and PZ 10b on 1 April 1943, the latter was used on security operations on the Tarnapol (broad gauge) line, and received the number PZ 11. Between the middle of March and July 1944 it was taken out of service to be brought up to BP 42/44 standard. Railcars PT16 and PT18 were attached to it between the Summer of 1944 until January 1945. It was destroyed on 13 January 1945 near Chęciny to the south of Kielce, blocked along with PZ 25 by a destroyed bridge over the Nida.

Created on 10 June 1940 from ex-Polish rolling stock, PZ 21 moved to the Eastern frontier where it was based in the ‘Germano-Russian zone of interest’ from 22 July 1940. It remained in Poland, under the orders of the 5th Panzer Division, up until April 1941 when it moved to France. There it came successively under the control of the 94th Infantry Division then the 337th Infantry Division up until July 1942. On 17 July it left for the Eastern Front and the Rshev sector, where it carried out anti-partisan missions for the 286th and 78th Security Regiments up until 6 February 1943. From 6 February 1943 up until the end, it remained in central Russia and in July, it went into action to the south of the Kursk Salient during that battle. In early 1944, it operated against partisans in the Pripet region to the east of Brest-Litovsk. PZ 21 was captured by the Russians on 30 October in Lithuania.

From June 1942, Class BR57 No 1064 from the series BR5710-35 (armoured at Kharkov), was attached to PZ 11 as replacement for the ex-Polish Class Ti3 engine.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

An interesting view showing, in front of the artillery wagon, a Russian-type safety wagon, with armoured sides fitted with firing loopholes similar to those of the BP 44 trains.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In its initial configuration, from front to rear PZ 21 was made up of: the artillery wagon from PP 54 Groźny (100mm howitzer and 75mm gun), then the assault group wagon from PP 11 Danuta (without its antenna frame), Class Ti3-13 engine No 54 654, the assault group wagon from PP 54 Groźny (with its antenna), and finally the artillery wagon from PP 52 Piłsudczyk.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The two Polish training wagons would join PZ 21. Here is the one without lower armour protection.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Two anti-aircraft flat wagons mounting 2cm Flakvierling were added in the Spring of 1941. The gun seen on the artillery wagon, on which the original armour has been reinforced by plates with loopholes, is a 100mm howitzer.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 22 was created on 10 July 1940, using captured Polish rolling stock. It remained in Poland up until the end of March 1941, and on 10 April 1941 it arrived in France, where it was based at Tours. On 6 September, it was transferred to Niort, then moved to the Mediterranean coast. It remained there up until the middle of 1944 and only just escaped capture during the landings in Provence. It was then sent to Poland, where it was destroyed on 11 February near Sprottau.

Created on 1 March 1940 from captured Czechoslovak rolling stock, PZ 23 took part in the invasion of Denmark then was stood down on 2 October 1940. Reactivated on 19 June 1941, on the 27th it officially received the number 23. It moved to the Balkans where it reinforced the three Croat armoured trains already there. It remained in Croatia up to the end of the war, notably operating in the Belgrade region.

PZ 22 at Lesparre (50km/30 miles north of Bordeaux) in 1942. Behind the safety wagons is the artillery wagon from PP 54 Groźny armed with two 75mm guns.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This 2-8-0 Class 140C armoured engine (from the Paris Depot, number unknown) powered PZ 22 from the Spring of 1944, replacing Polish Class Ti3-4 engine No 54651. The photo probably dates from June 1944, at Lons-le-Saunier.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

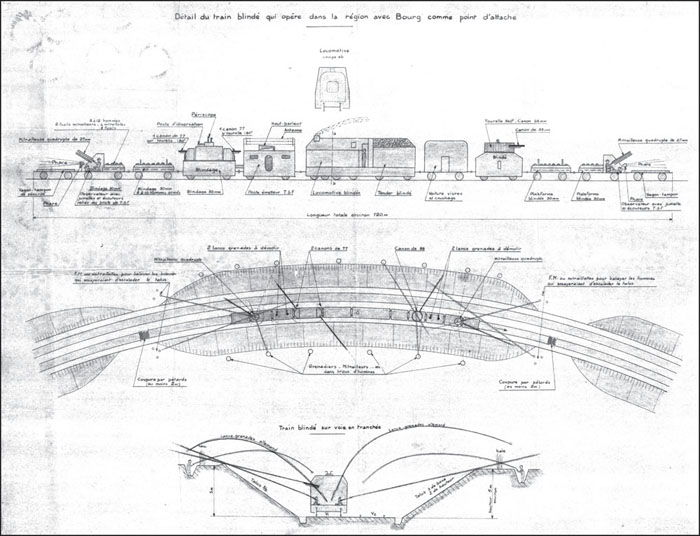

An exceptional document: a sketch made by the Resistance for the Allies, describing quite precisely the composition of the train, notably the Flak wagons and the ex-Polish training wagon.

(Drawing: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The initial version of PZ 23, with only the death’s-head insignia differentiating it from its Czechoslovak version. The leading flat wagon is the one which carried the Tatra T-18 trolley (see the chapter on Czechoslovakia).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A photo which illustrates the dramatic situation in Yugoslavia: the Royalist Chetniks finished up allied with the Germans in their common fight against the Communist partisans. By now PZ 23 had received Class BR93 engine No 220 which remained with the train up until late 1943.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Put into service on 1 March 1940, the early career of PZ 24, also composed of ex-Czechoslovak rolling stock, was identical to that of PZ 23. Reactivated on 19 June 1941, it took its number 24 on the 26th of that month. Up until 1943 it was in Serbia, then it moved to Italy. In early 1944 it was recalled to the rear for repairs. It moved to France where it was based from mid-1944 up until the landings in Provence on 15 August 1944. Recalled to the Eastern Front in the Winter of 1944/45, it was destroyed by its crew in Poland on 16 April 1945.

During the Winter of 1942/43, PZ 23 was rebuilt to BP 42 standards, including a Class BR57 engine. Here it is seen in Sisak (Croatia).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The rear of PZ 24. In front of the Czechoslovak artillery wagon is S Wagon 150.271 (ex-Austro-Hungarian PZ VII, afterwards Czechoslovak Armoured Train No 2), wagon 140.914 (PZ II, Czechoslovak Armoured Train No 1) and MÁV engine No 377.482.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Class BR57 engine No 2043 was attached to PZ 24 after December 1941. Note the Czechoslovak infantry wagon added in June, on which a 2cm anti-aircraft cannon position has been fitted.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A photo probably taken in August or September 1943, when PZ 25 had been transferred to Italy where it carried out coast-defence missions. The PzKpfw 38(t) tanks have replaced the Somuas.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Created on 1 March 1940 as No 9 from ex-Czechoslovak rolling stock, PZ 25 was stood down, then reactivated on 10 December 1941 under the number 25. At that point, Eisb.-Panzer.-Triebwagen 15 was attached to it. The train was sent directly to France, at the moment when PZ 21 was sent from France to the Eastern Front. The main armament of PZ 25 consisted of two 7.5cm guns and two Somua S35 tanks, replaced later by PzKpfw 38(t) tanks. From late 1943 up until 1 March 1944, it patrolled between Albenga and Nice, then from south-west of Nîmes to Montpellier. Following the landings in Provence, PZ 25 went to the Eastern Front where it was destroyed on 13 January 1945 in the region of Kielce.

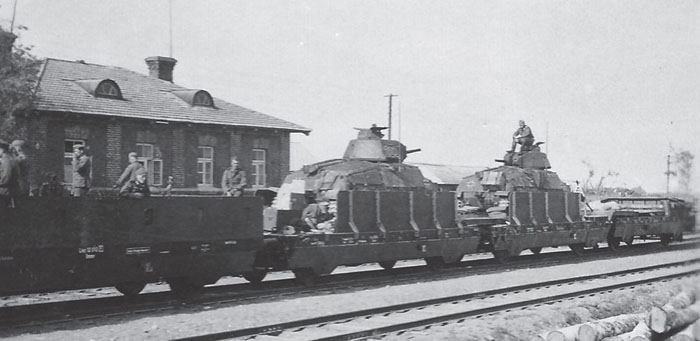

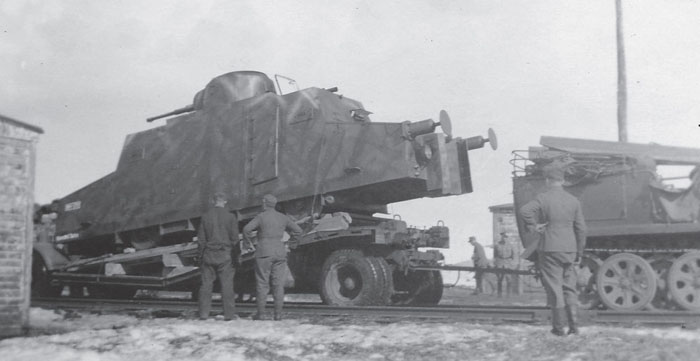

As the start date for ‘Barbarossa’ approached, the Panzerzug 41 programme had not yet begun, and only the tank-transporter wagons had been designed. It was decided to use fifteen captured Somua tanks to create six armoured trains for the Russian broad gauge, to be numbered from 26 to 31. A lack of appreciation of the partisan menace (to say nothing of the weather, which was even more surprising) led the designers to provide open wagons, while only the cab of the Class BR57 engines was armoured.

PZ 26 was activated on 26 May 1941. It comprised a Class G 10 armoured engine, three Type Omm wagons (wheelbase 6m /19ft 8in; length over the buffers either 10.1m /33ft 1½in or 10.8m/ 5ft 5in) each carrying a Somua, and two safety wagons. In December 1941 it was in the Leningrad area. During the Summer of 1942, certain wagons and the engine were replaced by Soviet units. Shortly afterwards, it was modified to run on the standard-gauge lines that the German engineers were laying down as and when the front advanced, replacing the Russian tracks. Between March 1943 and April 1944 it was in Germany to be modified, then it returned to the Eastern Front where it was deployed in the region of Idritza and Polozk. During the Winter of 1944/45, it saw action in Courland as part of the H. Gr.-Nord. It was captured on 8 May 1945 at Libau in Latvia.

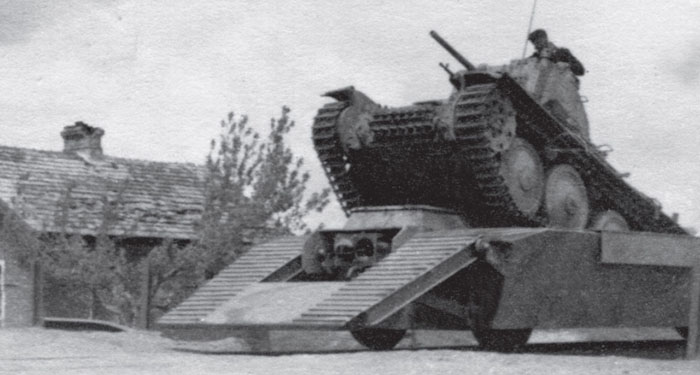

The front of PZ 26, with two Somua tanks leading, a configuration used only on the first three trains. The tank was able to descend from the Type Omm wagon, but the procedure was not straightforward and hazardous when under fire: the safety wagon in front carried the ramp, and it was necessary to uncouple this wagon in order to lower the ramp for the tank.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In early 1942 a Soviet wagon of the ‘Krasnoye Sormovo’ type was added, and by modifying one of the two turrets it was possible to provide the train with an anti-aircraft defence position.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

After the train was rebuilt in 1943, the 2cm Flakvierling was installed on a wagon converted from one of the old infantry wagons (with side armour protection extending below the level of the floor). The overall construction of the train was similar to that of PZ 1 and PZ 23.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

During the Winter of 1941/42, PZ 27 operated in the region of Briansk and Kursk and was then reconverted to standard gauge. On 30 May 1942 it was stood down and was not put back in service until 13 July using Soviet rolling stock, then in November 1942 it was converted to BP 42 standard. It was then engaged in the Pripet Marshes region and in March-April 1944 in the region of Brest-Litovsk to the north-west of Kovel. During the breakthrough at the ‘Cauldron’, it was immobilised by a direct hit to its engine, and several wagons were then destroyed. The remaining vehicles, together with those from PZ 66 took part in a counter-attack. Withdrawn to Warschau-Rembertow for repairs, it was abandoned there.

PZ 27 at Roslavl, in its initial configuration. Here we see one of the reasons for the limited height of the vertical armour protection beside the Somua: while it protected the tracks it also needed to allow access via the side hatch. Note the rail which allowed alignment of the tank on its platform. Also, the Somua tank turret marked with the number of the train has not had its cupola replaced by a hatch.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The assault group wagon from PP Pierwszy Marszałek has been converted to an anti-aircraft wagon in late 1942. The original Class BR57 engine No 2300 is now completely armoured.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Commissioned on 1 June 1941 at the Police Barracks in Teschen-West, PZ 28 entered Russia as part of Army Group Centre and operated with PZ 27 in the region of Terespol. During the Winter of 1941-42, it was in the zone Briansk-Orel-Kursk. In late March 1942, the Type Om infantry wagons were replaced with Soviet armoured wagons with 76.2mm guns. The engine was also ex-Soviet, an armoured Class Ob or Oa. Transferred to Army Group South in early 1944, it was at Nikolaiev for repairs then returned to the Warschau-Rembertow centre. It was destroyed in June 1944, during operations in the Carpathians.

Two captured Soviet wagons, the one on the right with the 2cm Flakvierling 38, and on the left, a 2cm Flak 36.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Faced with the threat of Russian tanks, before the anti-tank wagons were built, guns were placed on the leading flat cars: 7.5cm Pak, 3.7cm Pak etc. Here is a 76.2mm Soviet ZIS-3 installed in the Spring of 1944 at the head of PZ 28 in the place of a Somua tank.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 29 was activated on 1 June 1941 and placed under the orders of Army Group Centre in the region of Platorow. It was partially destroyed on 21 December 1941 when it lost three wagons in a ditch dug by partisans. Various demolitions (track, bridges) prevented the recovery of the wagons, and finally the train was broken up, the engine returned to the depot and its remaining wagons were shared between PZ 27 and 28.

A rare view of the WR 360C diesel locomotive with its frame antenna.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 30 entered Russia with Army Group North and operated in the Eydtkau region with Panzerzug 26. In December 1942, it left the front to be brought up to BP 42 standards, but using captured Soviet wagons. In early 1944 it was in southern Ukraine, then it was forced to retreat to the west of the Nicolaiev-Odessa line. Its engine was replaced by a Soviet Class S engine. In late April 1945, it returned to the Warschau-Rembertow centre for repairs, then participated in the defence of Danzig against the Russians. It was destroyed on 21 March 1945 near Gross-Katz.

Engine BR57 1504 on which the armoured cab is clearly visible.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 30 in its final configuration. The Soviet wagon at the front has received an observation cab, and the Soviet origin of the infantry/command wagon, with its 2cm Flakvierling covered with a tarpaulin, is also evident. The armoured passages between wagons have been added at the same time as the protection for the couplings.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Very few photos of PZ 29 are known. Note that the flanks of the Somua lack protection, but that the infantry wagons have received protection from the weather. Note also the diesel locomotive fourth in line. In the background are a Soviet BP 35 wagon and engine.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 31, the last of the trains specifically built for ‘Barbarossa’, was activated on 19 May 1941. Initially it was attached to the Sondertruppen, then as with the other trains, it came under the Heerestruppen. It entered Russia in 1941 in support of Army Group South and operated in the region of Zuravicav then Poltava. In early Summer 1942, it was equipped with Soviet vehicles, and soon afterwards was converted to run on the standard gauge. It was destroyed in December 1943 in Russia, but its crew escaped and were transferred to France, where they manned PZ 32.

Profile shot of PZ 31 with its BR57 engine between Soviet vehicles, in which the degree of comfort compared with the open Type Om wagons was certainly appreciated by the crew.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This photo is interesting as shows the conversion of one of the Soviet gun-armed turrets to an anti-aircraft position with a 2cm Flakvierling, the barrels of which have not yet been installed. From later photos it appears the 76.2mm gun was also retained on the mounting. Just visible on the left is one end of the (Russian) infantry wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

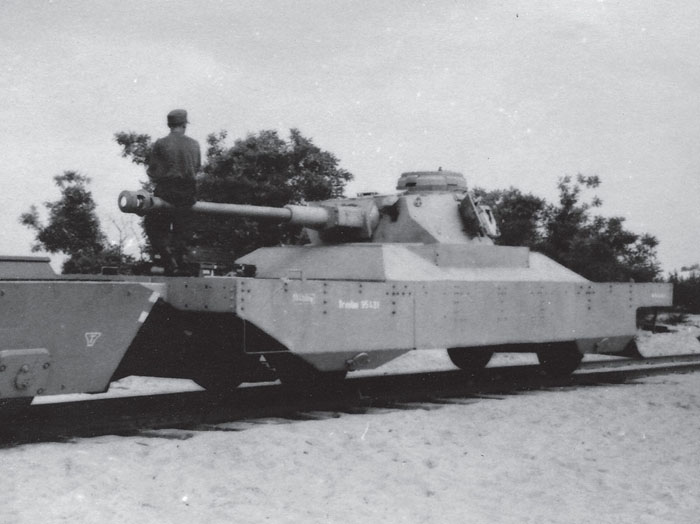

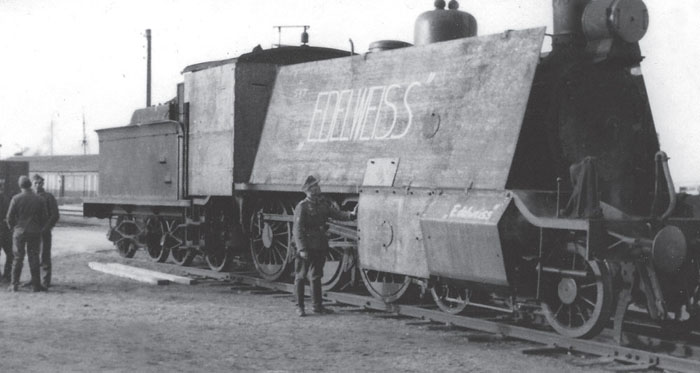

PZ 32 is probably the most famous of all the German armoured trains. It was immortalised by René Clément in his film La Bataille du Rail in which it – quite involuntarily – had the starring role. Its K-, G- and A-Wagen (the latter with 10cm 14/19 guns) were built in the Somua workshops at Lyon Vénissieux, the 0-10-0 engine (050A 33) was armoured in the Schneider workshops in Le Creusot, and the two tank-transporter wagons arrived complete from the Linke-Hofmann factory in Breslau. But as the Pz 38(t) tanks were delayed, they were replaced by two 122mm howitzers on GwLrs (Lorraine Schlepper). Its crew came from PZ 31. PZ 32 had an extremely short career in German hands: at 08.45 on 7 September 1944, as it entered Berain-surDheune Station, the train came into contact with French tank destroyers from the 3rd Squadron of the 9th RCA. At around 11.00 a shell from a tank destroyer shattered one of the coupling rods of the engine, which was repairable, but at 13.50, a shell hit to the boiler finally immobilised the train. The crew escaped, but did not have time to destroy the train. With the end of the war, PZ 32 embarked on a cinema career which was mysteriously ended by the torches of the scrap merchants.

0-10-0 engine 050A 33 of PZ 32 was armoured at Le Creusot. Its overall form followed the style of the engines of the BP 42/44 trains. Note that it was attached to the depot of Alès (Gard).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The A-Wagen of PZ 32 was in fact a Type BP42 G-Wagen, equipped with a 37mm Flak 36 anti-aircraft mounting. This modification reinforced the anti-aircraft defences of the train at a time when the Allies dominated the skies.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The K-Wagen. Note the shortened antenna, probably for the purpose of filming La Bataille du Rail.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In January 1942, PZ 51 was formed using Soviet rolling stock under the name of SSZ Stettin. It then became PZ ‘A’ on 10 May 1942, and finally PZ 51 on 16 June 1942. It operated within Army Group North, where it remained for the whole of the war. In early 1944 it was between Dno and Tchichatchevo, then in the region of Novgorod. In March it conducted operations against the partisans of the Idritza-Polozk region. It was destroyed in combat on 28 August 1944 in the region of Walk in Estonia.

PZ 52 was created in June 1944 by reinforcing the Streckenschützzug Blücher (seen here at Idriza). After fighting in Russia, it was destroyed near Danzig during the defence of that town in March-April 1945.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 60 (PZ R) was the training unit for the Rembertow Battalion. It was a Type BP 42 but does not appear in the official listing under that definition. In February 1944, it was in combat in the Lemburg region under the designation ‘R’. Then it was engaged in security operations to the west of Tarnopol. Seriously damaged in March 1944 it returned to Warschau-Rembertow for repairs, which were never carried out.

These two views (above and below} show PZ 60, which had all the features of the new Type BP 42 trains. It served as the training unit and was then sent into combat.

(Photos: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The three specialised wagons (A-Wagen, K-Wagen and G-Wagen) were built on Type Omm wagons with 6m (19ft 8¼in) wheelbase, 10.1m (33ft 1½in) long overall, coupled symmetrically in rakes on the BP 42 trains and asymmetrically on the BP 44s.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The armament of PZ 51 was made up of four 4.5cm KwK(r) guns in turrets from BT-7 tanks complete with coaxial machine guns, plus the turret guns of the PzKpfw 38(t) tanks carried on flat wagons after April 1944. In front of the engine is a Type OO wagon converted into a command wagon, and equipped with a Flak mounting.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Created on 1 September 1942, PZ 61 was the first of the initial series (Nos 61 to 66) of the new Panzerzug BP 42-type trains. It joined its operational area during the counter-offensive towards Velikiye-Liki in late December 1942, and remained in the Velisch-Dorogobouch zone, then in that of Vitebsk, up until the end of 1943. On 22 February 1944 it had to undergo repair, then rejoined the fighting in the Polok-Molodetchno-Wilna zone. On 27 June 1944 it was destroyed in the region of Bobruisk during the Soviet summer offensive.

PZ 61 probably undergoing maintenance, with its tanks not present, the Flak mounting with its side armour panels folded down, and the muzzle-cover on the gun. Note the reinforcement under the sides of the tank-transporter wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 62 was created on 15 August 1942, and it received its official number on 1 September. Sent to the Eastern Front, it joined Army Group South, where it still was in 1944 on the ChristinovkaTalnovie line. It next carried out security operations and joined in the counter-attacks launched to the South-East of Stanislav. During the Winter of 1944/45, it joined Army Group ‘A’ in Poland, where it was destroyed in January 1945.

This type of wagon was a modification of the Type R wagon, which allowed the tank to reverse into a protected well which sheltered its running gear. Extra protection was provided by four plates each side, folded outwards during the entry and exit of the tank. The permanently-fixed ramp required the adoption of mixed coupling types, a classic type at the rear and a Scharfenberg at the front. This arrangement allowed for a safety wagon to be coupled in front of the Panzerträgerwagen.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This photo of PZ 62 allows us to see a normally concealed feature, namely the raised central section of the floor which served to guide the tank into the well, and certainly increased the rigidity of the chassis.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

As the tank itself was armoured, the armour of the tank-transporter wagon was very thin (only 10mm as against 30mm for the other wagons), as a crew member demonstrates here, following the impact of a Soviet anti-tank round.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A fine shot of one anti-tank wagon followed by a second, made up of the complete hull of a PzKpfw IV placed on the safety wagon, thus providing a second 7.5cm gun capable of firing over the top of the wagon in front. Note that the casemate of the anti-tank wagon is fitted with additional vertical armour.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 63 was attached to Army Group North immediately on being commissioned, where it stayed until 1944, operating against the partisans on the Pleskau-Luga line. In early 1944 it transferred to the reserve of Army Group South and in April went into action around Lemberg. It was destroyed on 17 July 1944 to the East of Krasne. It was one of the trains most often photographed for propaganda reasons.

The A-Wagen of PZ 63, with its special camouflage scheme. The 2cm Flakvierling mounting is placed quite high, and by folding down the side armour it could engage ground targets.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The armoured tender was provided with hatches over the top of the coal supply. Nevertheless the demand was always greater than the standard quantity carried, as this extra pile of coal shows. On certain trains, the carrying capacity was increased with vertical planking. An identical tender was coupled to the front of the engine.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 64 in Croatia in July 1943, probably at lunchtime judging by the crowd gathered next to the G-Wagen.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 64 was created on 1 October 1942. It became operational on 18 June 1943 and was sent to the southern zone of the Eastern Front. In early 1944 it was required in the Balkans where it fought the partisans in Croatia, and in late 1944 it was sent to Hungary. During the Winter of 1944/45, it was reinforced by the attachment of Panzertriebwagen 19. During fighting in February 1945 one of its PzKpfw 38(t) tanks was destroyed. The train was captured 30km (18 miles) to the north of Graz on 9 May 1945.

Created on 1 November 1942, PZ 65 immediately went to Croatia where it was placed under the orders of the Security Troops High Command. It ultimately withdrew into Germany where it was captured by the Americans at Hotlthusen.

PZ 66 was the last train of the first order for the Type 42. Sent to the East, it operated on the Minsk-Orscha line, then to the south of Mogilev. In April 1944 it participated in the counterattack to the North of Kovel, and patrolled in the zone Brest-Barano-Vitchi. During the retreat in the Summer of 1944, it was destroyed near Warsaw on 30 July.

The first train of the second order for BP 42 types, PZ 67 became operational on 15 March 1943 and was sent to the East. In early 1944 it was in the region of Polozk where it operated as part of the 281st Security Division. On 28 August 1944 it was damaged near Mitau in Courland and the crew sabotaged it. PZ 68 was formed on 1 August 1943, and by early 1944 it was in the Pripet region where it operated against the partisans. It was destroyed in April 1945 during the battle for Danzig. On 22 March 1944, PZ 69 was heavily damaged and was finally destroyed by its crew near Tarnopol. PZ 70 operated from March 1944 in the region of Slobodka-Birsula (Army Group South). On 4 April 1944 its crew found themselves blocked by the destruction of the track in Radelsnaya Station, and they destroyed the train during the Soviet breakthrough. PZ 71 was created on 16 September 1943 then operated in the region of Tarnopol in January-February 1944. In late April 1944 it was at Lublin for maintenance work, and it was sabotaged at Slanic (Romania) on 31 August 1944.

The case of PZ 72 was different: created on 23 November 1943, in the Spring of 1944 it was converted into two armoured command trains, Befehls Panzerzug 72a and 72b. The former became part of Army Group Vistula from 2 February 1945 and participated in the defence of East Prussia. It was destroyed during the fighting for Kolberg on 16 March 1945. Befehls Panzerzug 72b was sent to the Warsaw region where it only just escaped being surrounded, only to be destroyed on 28 March 1945 near Danzig.

This command train carried an unusual form of antenna on its K-Wagen.

(Photo: Frédéric Carbon Collection)

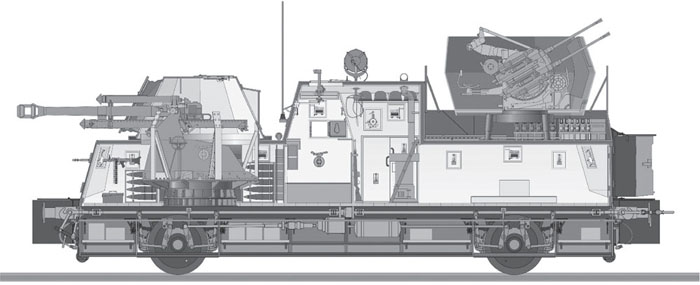

A sectional view (no scale) of an A-Wagen of a Type BP 44 PZ, in a special version where the quadruple Flak mounting was protected by a turret similar to that of the Wirbelwind (Whirlwind) anti-aircraft tank.

(Drawing: Marcel Verhaaf)

The Panzerjägerwagen is the surest way to identify a Panzerzug BP 44 (and earlier trains brought up to that standard). Designed by the LHW Company, this wagon had a 5m (16ft 4¾in) wheelbase. Sloping armour protected the sides and the axle boxes, while a stoneguard in the shape of a snowplough was fixed to the front end. This wagon could propel itself independently at modest speed thanks to four rollers placed in front of the rail wheels. The coupling system was mixed: standard at the front and Scharfenberg at the rear.

(Photo: Frédéric Carbon Collection)

The turret from a PzKpfw IV AusF H, armed with a 7.5cm KwK40 L/48 was mounted on a well-shaped casemate, provided with firing and observation ports; in general the turret and casemate would have had additional external armour plates fitted.

(Photo: MHI)

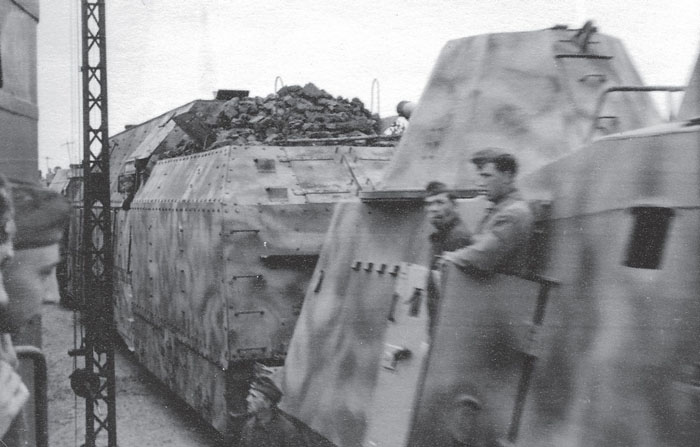

Here we see PZ 75 being emptied of its equipment and ammunition, which is being piled on the passage between wagons. The camouflage foliage appears reasonably fresh. One can only regret that practically no elements of any of these captured trains has survived, and that no technical reports – which must have been prepared at the time – have come to light.

(Photo: MHI)

PZ 73 was created on 19 November 1943, then operated in Italy up until mid-1944, where it was captured intact at the end of the war. Powered by a Class BR93 engine with a different armour arrangement to the rest of the series, it had served as the prototype for the Panzerzug Type BP 44.

The first Type BP 44 train, PZ 74 went into action on 25 July 1944 while it was still at Rembertow in an unfinished state, and on the 29th it was destroyed in an attack by T-34 tanks.

As with PZ 74, PZ 75 went into action in an unfinished state, near Warsaw on 15 July 1944 then with Army Group Vistula, as Instructional Train No 5. In this capacity it transferred to the base at Millowitz in October 1944. It returned to operations on 31 December, and was captured intact by American troops at Hagenow.

PZ 76 was created in April 1944 and sent to Poland to join Army Group Centre, where it covered the retreat of the German troops to the north of Warsaw. It was destroyed on 14 April 1945 near Königsberg in Sambie.

Despite the camouflage, the shape of the 10.5cm turret is clearly visible. Note the two tubular structures which may be limiters to prevent the turret from firing into the tender. This photo seems to have been taken at Millowitz when PZ 76 was being demonstrated.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Created in May 1944, PZ 77 was attached to Army Group Vistula and was at Millowitz from February 1945. It was destroyed on 26 February in Pomerania.

PZ 78 was created in late May 1944 and attached to Army Group South. In February 1945 it moved to Hungary where it remained for the most part. On 9 May, after the news of the German surrender, the train made its way to Thalheim where it was abandoned. Its crew succeeded in escaping to the American Zone.

PZ 77 was destroyed in combat on 26 February 1945 at Bubitz. Note the creation of a storage space out of sleepers, on the rear of the anti-tank wagon in the foreground.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 78 captured intact at Thalheim on 9 May 1945. One special feature of this train was the A-Wagen with a turret similar to that on the Wirbelwind AA tanks.

(Photo: RAC-Tank Museum)

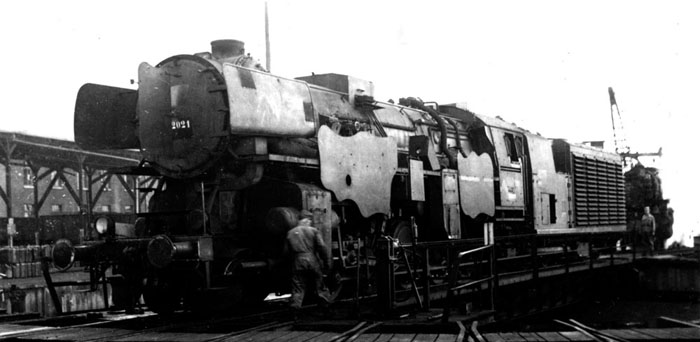

Armoured engine BR52 1965 K (Condenser) in Czechoslovakia post-1945. It is not known whether the armour was fitted by the Germans or the Czechoslovaks, and for which of three possible trains.

(Photo: Glöckner Collection)

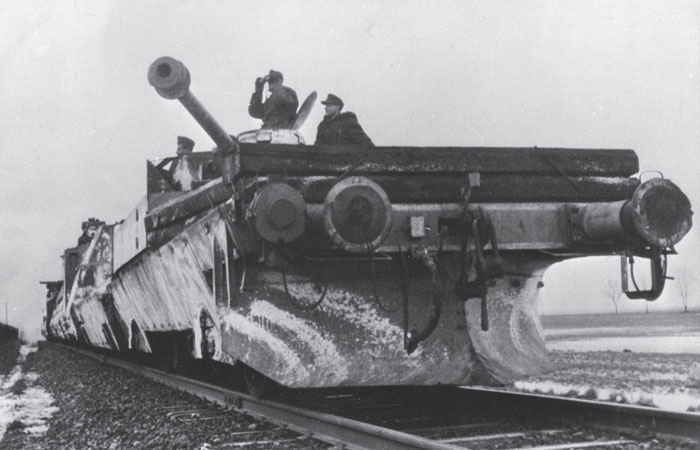

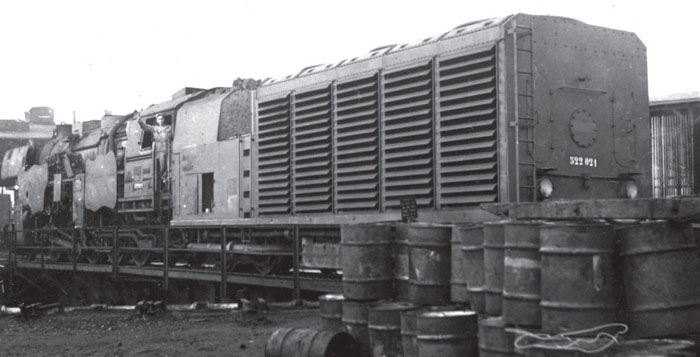

BR52 K 2021 with partial armour protection. This engine was part of PZ 80. Here it is seen after the war, in the American Occupation Zone, in use by the 740th Railway Operating Battalion.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Railway modellers will know that the firm of Mikrometalkit used the same serial number for their BR52 K armoured engine.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

PZ 81 seen after its surrender in Czechoslovakia, at Pisak in 1945. It was powered by BR52 7305. PZ 82 was completed just before the end of the war and included BR52 1965.

(Photo: Tomáš Jakl Collection)

Evidently taken in the Summer of 1945 (it is in the process of being dismantled: note the missing buffers) in this photo of a PzJgWn with an American soldier we see a forward observation position, which precludes the 7.5cm gun from depressing below the horizontal. This could be from PZ 73.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

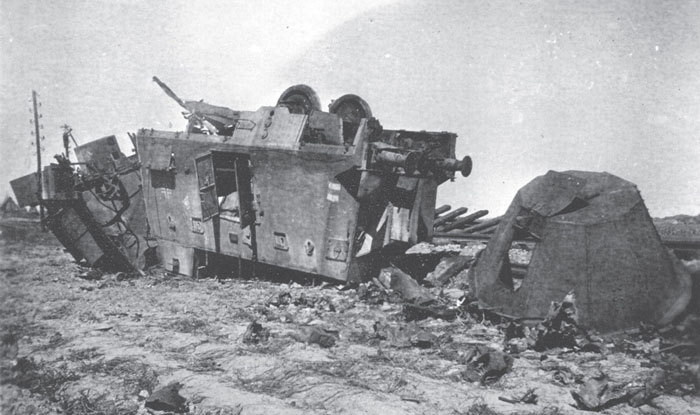

Here this PZ has shared the fate of so many armoured trains on the Eastern Front. Evidently several days have passed since it was destroyed, judging by the fact that the armament has been removed and there is a deal of rust on the overturned K-Wagen.

(Photo: Frédéric Carbon Collection)

Following the 1940 invasions, then the occupation, of various European countries, ‘protected’ trains were put into service as for example in Norway with trains Norwegen, Bergen etc …

The Russian Front saw the use of numerous makeshift armoured trains such as the security trains (Streckenschützzug) Polko, Michael, Max etc, and it is difficult to appreciate why they were not considered as ‘regulation’ armoured trains. Certain ones were later transformed into armoured trains and given a number, as with Blücher which became PZ 52, and others which were listed as Panzerzug.

In early 1945, security train ‘350’ operated with Army Group Vistula and in February 1945 was in the Krupp-Drückenmüller workshops for upgrading.

In the final days of the war in Europe, armoured trains were being put together using a variety of materials, such as the trains under construction in the Linke-Hofmann factory in Breslau.

In Greece, security trains Nos 204 to 214 were put into service, but the actions they took part in are poorly documented.

One of the security trains in Norway, with an interesting method of mounting the gun, allowing it to fire at an angle forward, and small openings used as observation/firing slots, also on the following wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A Norwegian 4-6-0 engine, probably a Class 18, hastily armoured. On later photos this engine was also named Sandhase (‘Sand-hare’, German slang for an infantryman).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Bergen, showing its unusually low silhouette compared with other contemporary armoured trains. Note that the two wagons in front of and behind the FlaK wagon are open-topped, despite the climate.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

One of the wagons of Blücher, converted from a Russian bogie wagon on which a PzKpfw II was encased in wooden protection, no doubt doubled internally with steel plates.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

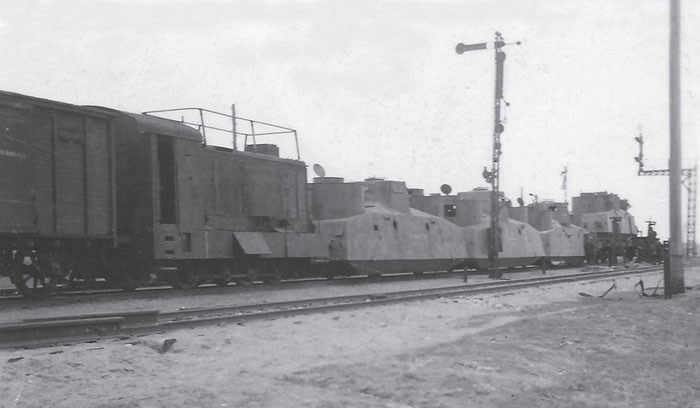

SSZ Polko, formed out of captured Soviet rolling stock, including an artillery wagon from BP 1, the engine, a flat wagon equipped with an anti-aircraft mounting and safety wagons.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The front of S.S.Z.350, with its infantry wagon, a Flak wagon (in fact a wagon with sides protected by concrete, leaving firing slots, with a Flakvierling mounting), then a leading wagon carrying the hull of a PzKpfw IV.

(Photo: Wolfgang Sawodny Collection)

Security train Leutnant Marx made up by the 221st Sicherungs Division, which operated in the area of Orel and Livno. In 1942, this train was transferred to the 707th Infantry Division stationed at Rembertow.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

On entering Germany, at Ohringen American troops found wagons probably intended for the anti-aircraft defence of train rakes, provided with a concrete tub protecting the gunners. Note the rungs to climb up into the fighting position.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

Security train in Greece, with its concrete blockhouse and a Renault FT tank, here armed with a 37mm gun. The engine is a Class Zd, obtained by Greece following the First World War.10 Another such train was powered by a Class La engine.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This wagon (ex-command wagon of PP Pierwszy Marszałek, No 3930.88) was the sole armoured element on this train.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Security train in Latvia, formed of several four-wheel wagons with the hulls of BT-5 tanks.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The light armoured reconnaissance trains Panzerzug (le.Sp) 301 to 304 created on 16 September 1943 were sent to the Balkans. No 301 operated in March and April in Serbia in the Ujse-Raska region and was destroyed at the end of the year. No 303 would be captured at the end of the war and No 304 was destroyed. To the best of our knowledge only one of these trolleys survives, in Trieste, being the one used by the British in their zone (see the chapter on Great Britain).

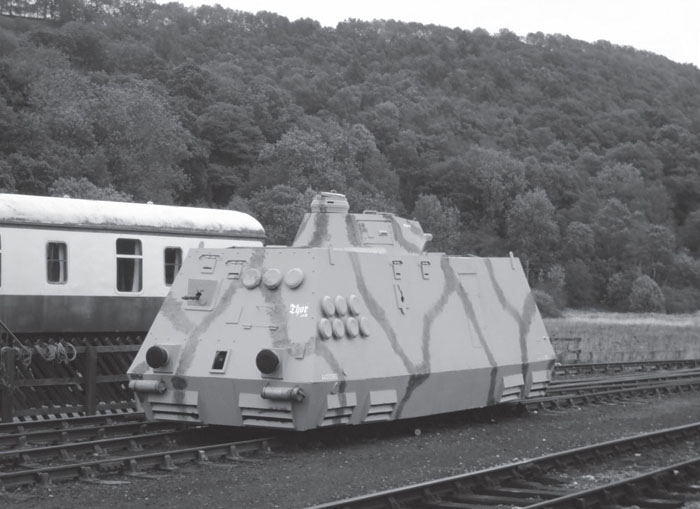

Steyr built the trolleys which would form the heavy reconnaissance armoured trains Eisenbahn-Panzerzug (s.Sp) Nos 201 to 210 on the mechanical base (chassis and motor) of the le.Sp. Train PZ (s.Sp) 201 was created on 5 January 1944 then was sent to the Balkans, where it would be captured at the end of the war. Nos 202, 203 and 204 became operational on 10 January 1944, 21 February 1944 and 23 March 1944 respectively, and were also sent to the Balkans. Nos 205 to 208 were built between April and June 1944. The last two in the series were not completed, at least one of them being captured at Millowitz in April 1945 (see the chapters on Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia).

These machines are popular with enthusiasts who are passionate about armoured trains, probably because they resemble tanks on rails. In 2013 one was reconstructed by mounting a hull and turret built of plywood on a flat wagon. The turret revolved and could even fire blanks. It was planned to dismantle it in late 2015 to recover the original flat wagon for the railway preservation society collection.

PZ (le.Sp) 304 at Amorion in Greece on 30 August 1944, following its capture by partisans led by V Kassapis, seen here perched on the side of the vehicle.

(Photo: V Kassapis via Georges Handrinos)

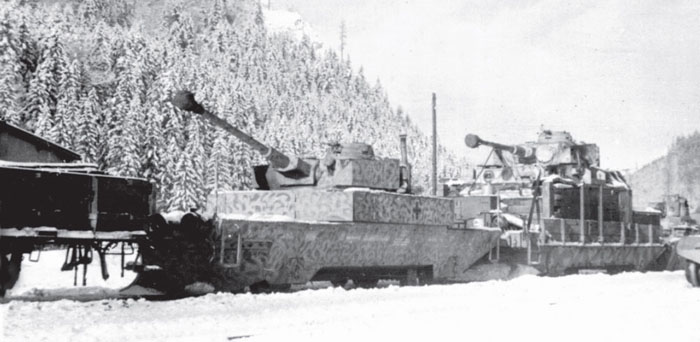

A train formed of heavy trolleys being inspected by American soldiers at Dachau in 1945. Note that the coupling hooks have been removed. Although Steyr was responsible for building the hulls, the PzKpfw III turrets were fitted by Kraus Maffei in Munich.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

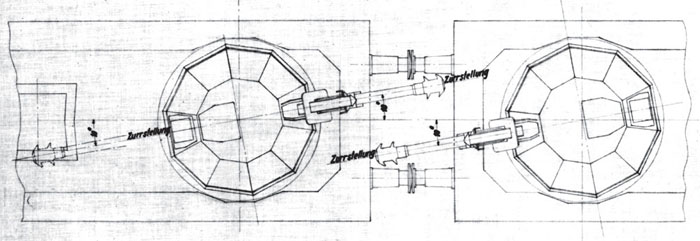

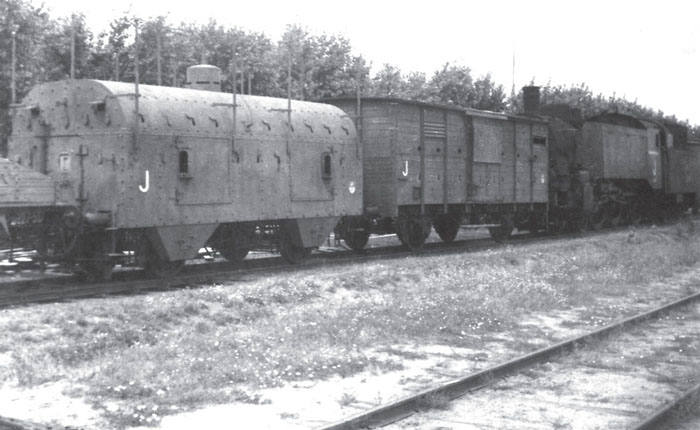

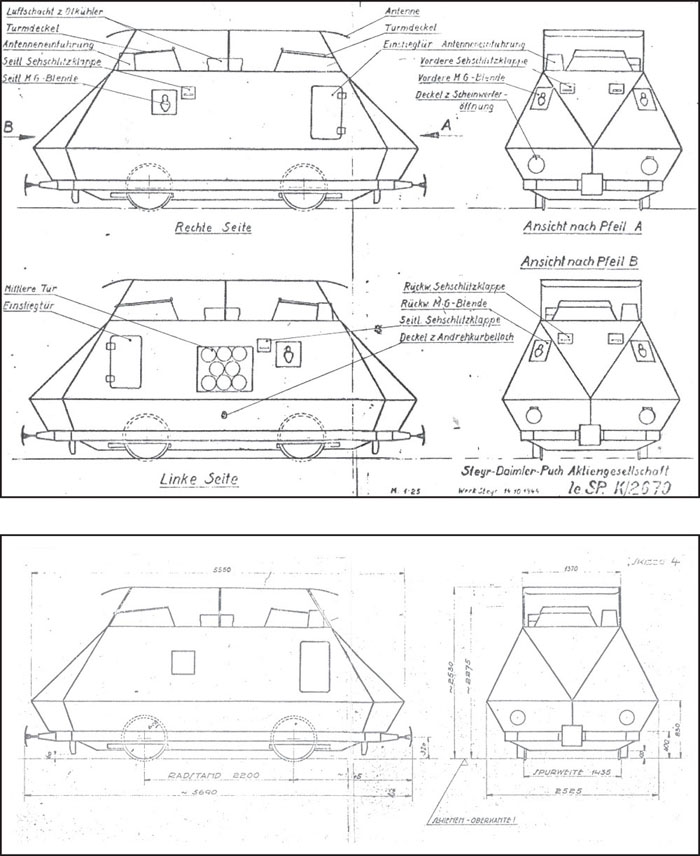

Two original drawings of the le.Sp Steyr trolley. The number ‘K/2670’ often found in literature is in fact the number of the plan drawing. Note that the form of the armoured air intakes corresponds to the final production model. The same chassis was used as the base for the heavy trolleys, and the difficulty of adapting it to carry the increased weight slightly delayed the production of the s.Sp.

(Drawings: Steyr-Daimler-Puch Archives)

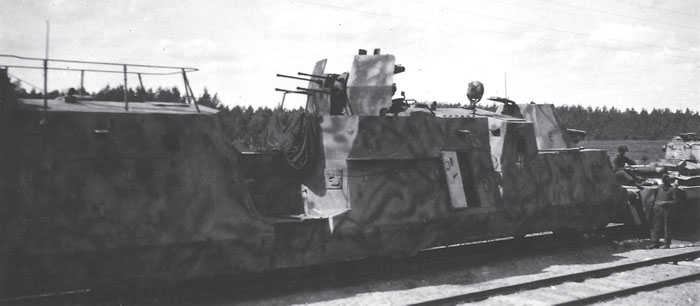

A rare shot from above showing a train of heavy trolleys captured by the Americans in South Germany. Why none of these units has been preserved and that no technical report has come to light (if one was established, which is unsure) remains a mystery.

(Photo: Stuart Jefferson Collection)

The reproduction s.Sp trolley named Thor built by the Levisham Historical Re-enactment Group (North Yorkshire) seen on 11 October 2013.

(Photo: Mark Sissons)

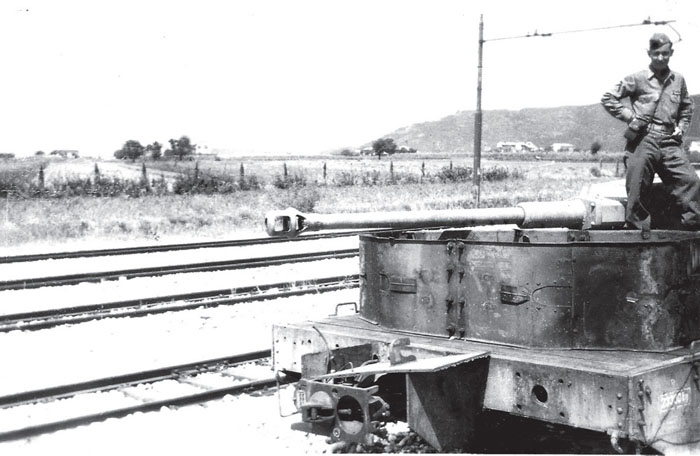

Eisb.-Pz.-Triebwagen 15, the only railcar put back into service after having been used by the Reichsbahn, was sent to France in 1942, then in 1944 to the Larissa region in Greece.

TR 15 seen in Greece.

(Photo: Wolfgang Sawodny Collection)

Eisb.-Pz.-Triebwagen 16, activated on 27 January 1944, was the most powerful railcar built for the Wehrmacht, by Schwarzkopf at Berlin-Wildau, on the base of diesel locomotive WR 550 D 14. The armour protection was fitted by Berliner Maschinenbau AG in Wildau. In the Summer of 1944, it was associated with PZ 11 (along with PT 18) and operated in the Ukraine. In July, the train and its two PTs broke out of a Soviet encirclement in the Rawa-Russka region then participated in the defence of Lublin. It retreated towards the River San on 27 and 28 July. On 12 January 1945, it was surrounded during the Soviet offensive, but succeeded in breaking out of the encirclement by a remarkable action on the part of its crew, who constructed a track on which to escape. Today PT 16 is preserved in the State Railway Museum in Warsaw (see the chapter on Poland).

In its original form, PT 16 had no turrets, just two antiaircraft positions each with a 2cm Flakvierling mount but no shields. Hitler having found it to be under-armed for its size (200 tonnes, with two layers of side armour each 100mm thick!), the order was given to equip it with artillery turrets armed with 7.62cm F.K. 295/1(r) cannons.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

An outstanding photograph taken in August 1944, showing probably for the first time PT 16 in its final form with one tank destroyer unit at each end, built around T-34 tank hulls secured on flat wagons. They are armed with one T-34/76 E Model 43 to the right, and T-34/76 Model 42 to the left. Note that the wagon side armour is low above the tracks, while the armour was only protecting the axles some months before. Here PT 16 is seen from the rear left, and the commander’s cupola is open above the front compartment.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari collection)

Eisb.-Pz.-Triebwagen 17 to 20 were formed of ex-Soviet MBV D-2 railcars repaired, re-armed and re-engined. PT 17 was activated in April 1943. Remaining on the Eastern Front, it was destroyed in August 1944 near Warsaw. PT 18, 19 and 20 were activated on 20 November 1943 and were sent respectively to Poland, to Army Group Centre, and to the camp at Lissa on the Elbe. All were armed with 7.62cm F.K. 295/1(r) guns. PT 20 was attached to PZ 11 from the Summer of 1944, and was destroyed on 16 January 1945 at Kielce.

After PZ 29 was broken up, its diesel locomotive was used for other tasks, as here hauling ex-Soviet MBV D-2 railcars intended to be put back into service.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Railcar from the PT 17 to 23 series. Note the frame antenna, the position of the exhaust silencers, and the additional armour added around the base of the turrets. The machine measured 10.30m (33ft 9½in) long on a wheelbase of only 3.90m (12ft 9½in).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In this photograph taken in August 1944, PT 18 is shown in its final version, namely with an additional armour covering the front half of each turret. Note the unusual camouflage scheme. PT 18 remained in service along with PT 16 until the 1945 fighting in Poland. It received several hits on 13 January 1945 and had to be abandoned in Kielce.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari collection)

Eisb.-Pz.-Triebwagen 30 to 38 were the Italian LiBli Type Aln-56 railcars, one of which had been seized at the Italian Armistice in 1943. Eight of the anti-aircraft version were ordered new from the Italian constructors, making a total of nine LiBli operated by the Wehrmacht. The first three units, TR 30 to 32, were activated on 12 May 1944.

Panzerjägertriebwagen 51, 52 and 53. Built in late 1944, but never put into service, these tank-destroyer railcars were armed with turrets from PzKpfw IV Ausf H or J. One of them was captured and put into storage in an American depot in Augsburg, and the other two were damaged by bombing in the Linke-Hofmann factory in Breslau.

One of the three railcars Nos 30 to 32, probably photographed at Millowitz.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Either PT 30 or 31 in Serbia after extensive modification: apart from the installation of a 2cm Flakvierling in place of the roof armament of the Italian version, note the 2cm cannon in the turret and a new arrangement of the buffers.

(Photo: Aleksandar Smiljanic Collection)

Photographed in Augsburg at the end of the war in Europe were several rail vehicles, including the only complete example (in service?) of the tank destroyer railcar No 51. Note the unprotected buffers and couplings, perhaps intended to be armoured later, as well as the protected left headlight. As was done on all captured pieces of equipment, a white ‘ALLIED FORCES’ is painted on the side.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This exceptional close-up allows us to note that the two sides were not the same, this side having only one door and the antenna base.

(Photo: Stuart Jefferson Collection)

Forty of the 190 Panhard 178 armoured cars captured during the Battle of France were converted to trolleys and attached in pairs to each Type BP armoured train. The rail wheels were made by two firms: Gothaer Waggonfabrik and Bergische Stahlindustrie (Remscheid). Certain examples were fitted with buffers.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

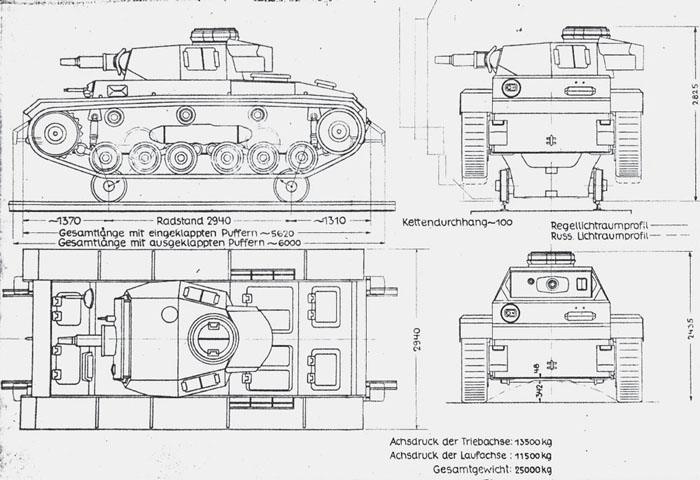

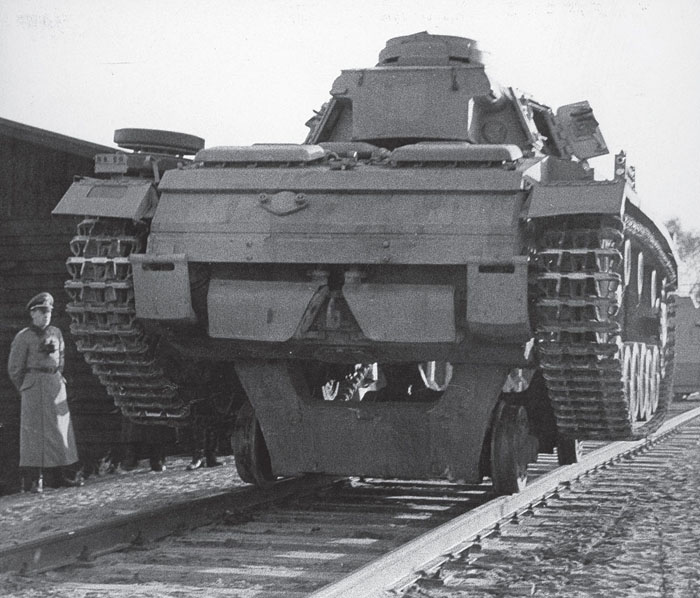

Trials and demonstrations took place in the grounds at Arys11 in October 1943, with two or three PzKpfw III Ausf L/N of the final series, armed with the 7.5cm KwK L/24. The machine was given the designation of ‘SK 1’ meaning ‘Schienenkampfwagen 1’ (Rail Tank No 1). The transmission, motor and cooling system were identical to those of the original tank, the last three torsion bars of the suspension needed modifying. With the added parts under the tank the ground clearance decreased from 48cm (1ft 7in) to 34.2cm (1ft 1½in). The drive on the rails was transmitted via the forward axle, the other being free-rotating. No matter how well the system performed, and the speed and haulage capacities were impressive, by 1943 the PzKpfw III was completely outclassed as a fighting vehicle.

SK 1 Technical specifications:

| Length (buffers folded): | 5.62m (18ft 51/4in) |

| Length (buffers extended): | 6.00m (19ft 61/4in) |

| Width: | 2.94m (9ft 73/4in) |

| Height (on road): | 2.435m (8ft) |

| Height (on rails): | 2.825m (9ft 31/4in) |

| Weight: 25 tonnes Motor type: | 12-cylinder Maybach HL 120 TRM |

| Horsepower: | 320hp at 3000rpm |

| Transmission: | Fichtel & Sachs six-speed gearbox |

| Speed on rails (maximum): | 100km/h (62mph) |

| Speed on rails (normal): | 60km/h (37mph) |

| Wheelbase on rails: | 2.94m (9ft 73/4in) |

| Gauge (European standard): | 1435mm (4ft 81/2in) |

| Gauge (Russian): | 1524mm (5ft) |

| Fuel capacity: | 350 litres (921/2 Imperial gallons) |

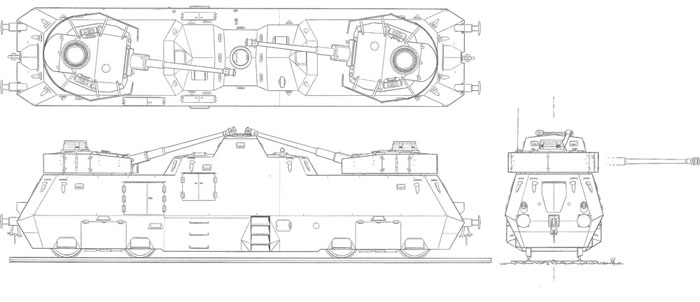

Drawing of the SK 1 tank.

(Saurer Archives)

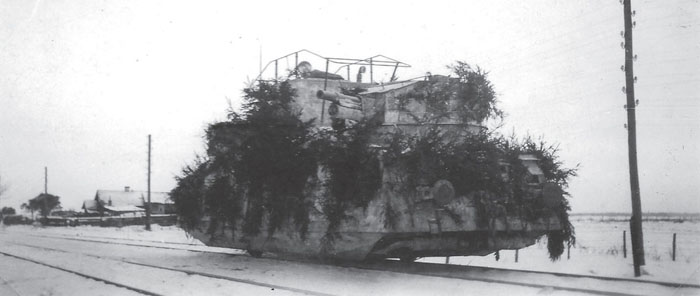

This machine was built in Finland from Russian components: the doors came from Komsomoletz artillery tractors, the turret from a BA-10, and so on. It was used on the Kemijärvi-Salla-Alakurtti branch, which straddled the frontier with Russia.12

The trolley in Salla Station (Finland) which allows a good view of the camouflage scheme and allows an extrapolation onto the horizontal panels. The serial number marked on the hull side is ‘WH-E.P. 1’ which could indicate it was intended as the first of a series of such builds.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)