The first Italian foray into the realm of armoured trains occurred in 1891, when an Italian officer, conscious of the difficulty of defending the long coastlines of his country, laid before Parliament a proposal to defend Sicily with armoured trains. Although the idea was not taken up at the time, the Italians, like the British, were well aware of the possibilities offered by using armoured trains for coastal defence.

The story of Italian armoured trains began after the Treaty of Lausanne was signed on 18 October 1912, recognising Italy’s occupation of Libya. The conquest of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica had begun on 29 September 1911 with naval operations and landings. Benghazi was occupied on 20 October and Tripolitania was annexed on 5 November. There followed a year of fighting and an expansion of the revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The Treaty of Lausanne put an end to the war, but sporadic uprisings continued until 1931 when Sheikh Omar Al Mokhtar, the ally of the Senussi, was executed. Beginning in 1912, the Italians built a 95cm gauge network in Tripolitania and to guarantee security, put into service an armoured train comprising an engine and two armoured wagons based on a pair of flats used to transport long loads such as gun barrels.

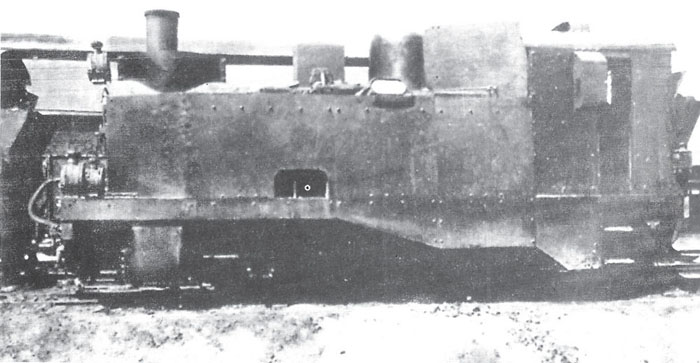

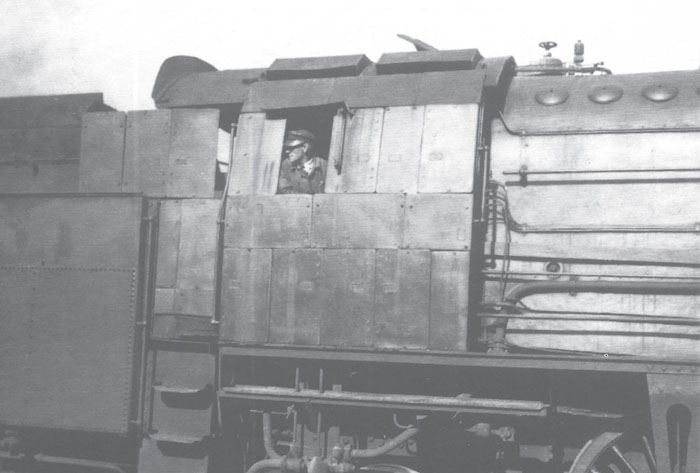

The engine intended to haul the train, fitted with fairly comprehensive armour protection, including an armoured lookout on each side of the cab.

(This photo and the two following: Nicola Pignato and Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano (Volumes 1 and 2), by kind permission of the Ufficio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito – USSME)

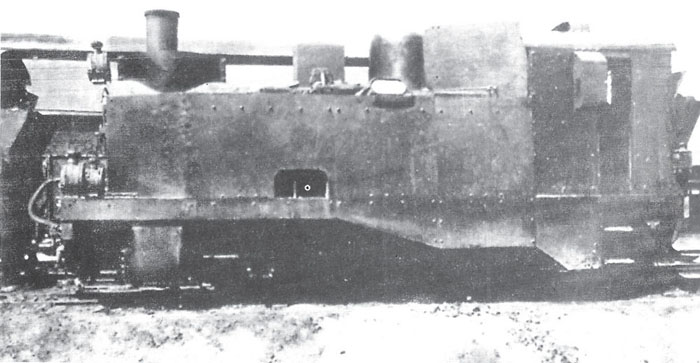

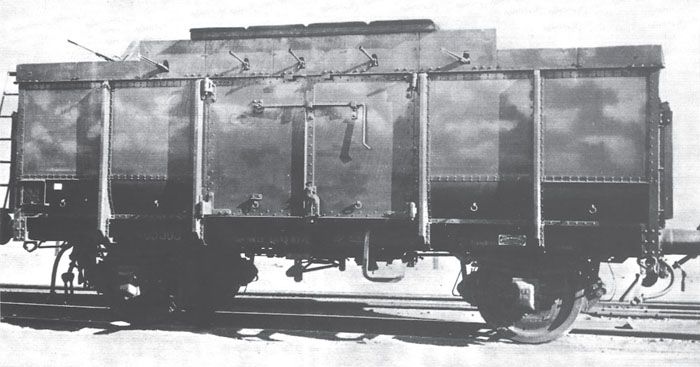

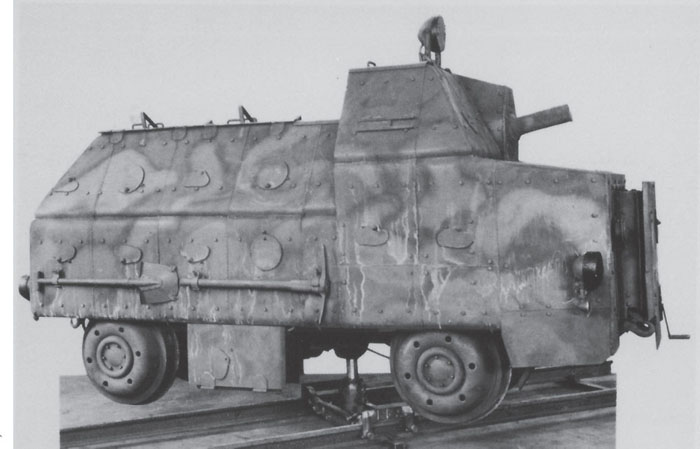

Two external views of one of the armoured wagons, with personal weapons (Carcano carbines) ready to fire from a standing position. This type of wagon would be effective against the types of light armament possessed by its opponents at the time it was introduced.

Note the access door at the engine end. The five Maxim machine guns could train over a wide arc. The central part of the roof was left open. Photographed in the workshop with the wagon on a short length of temporary track.

During the First and Second World Wars, the concern about coastal defence resulted in the ‘Treni Armati’ (‘Armed Trains’) which were operated by the Regia Marina (Italian Navy). We will not study them in this work, as they are railway artillery rather than armoured trains in the true sense.

On the other hand, rail trolleys, not all armoured, were used in sensitive areas such as the Libyan-Egyptian frontier. In the absence of other photographic records we have to return to the works of Nicola Pignato and Filippo Cappellano for a poor-quality but nevertheless unique image.

Armoured trolley used on the frontier between Libya and Egypt.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

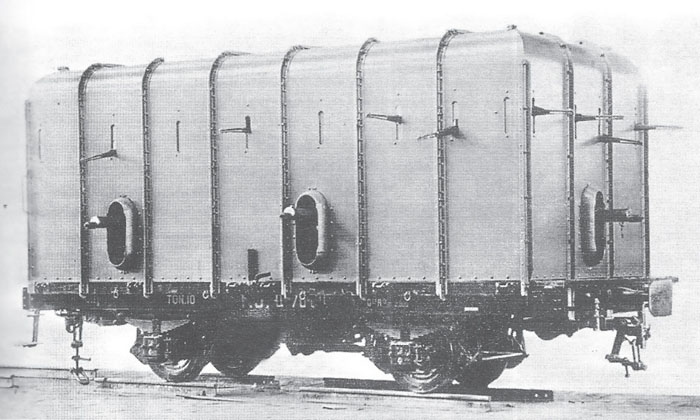

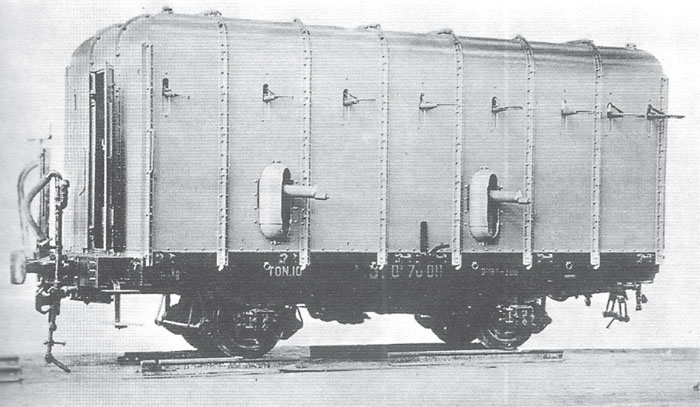

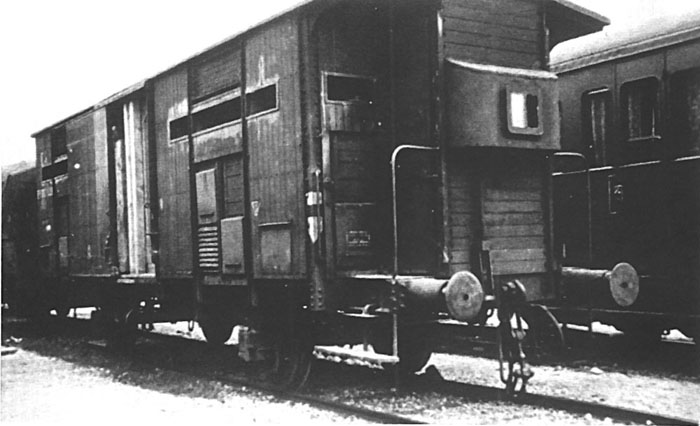

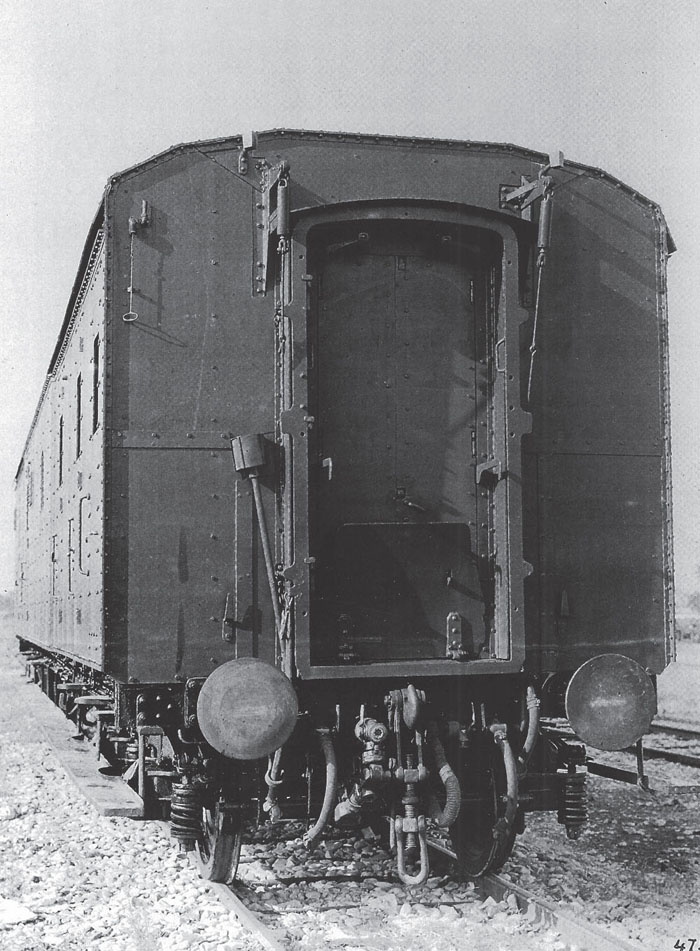

A type of escort wagon converted from a Type 1905 F van, with minimal armour protection and large loopholes.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

One of the first of the armoured trains, intended for coastal defence, with a Breda 20mm cannon and a 47mm Model 32 anti-tank gun.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

In the Balkans, the Italian zone of occupation included Slovenia, the Dalmatian coastline and the islands. Montenegro and Albania had already been included in the Italian Empire. At the time of the Italian invasion of Greece, Albanian resistance movements were disrupting communications routes, but when the Germans joined in the occupation of the Balkans, it was they who took over responsibility for the defence of the railway networks.

The Compagnia Autonoma Autoblindo Ferroviairie (Independent Railway Armoured Car Company) was created in Yugoslavia on 15 May 1942. In order for it to carry out its mission, which was to control the railway lines, several improvised armoured trains were converted from bogie wagons. The Littorina Blindate (‘Libli’) railcars, Model 42 trolley and the rail version of the AB 40 will be considered later.

Separate from the escort wagons of the Milizia Ferroviairia (Railway Militia) which were included in goods trains, ten armoured trains were built, beginning in 1941, to assure the security of the lines in the Italian occupation zone in Yugoslavia. They were of simple design, converted from goods wagons, with armoured sides, and were initially armed with infantry weapons. In each train, two wagons were equipped with a 47mm 47/32 Model 35 anti-tank gun, able to fire at 90 degrees to the track by opening doors which gave a horizontal field of fire of around 120 degrees. Each gun covered one side of the track. Another wagon was armed with 20mm Breda Model 37 cannon. With the partisan threat increasing in intensity, the trains later incorporated wagons (up to six) with improved armour protection, having a central covered compartment (of wood or steel) with firing loopholes, and at either end an open-topped firing position for an 8mm Fiat/Revelli Model 14/35 machine gun. The armament was completed by a 45mm Brixia Model 35 mortar.

A goods wagon base armed with a 47mm Model 37 gun fitted with a small shield. The canvas covers add a degree of comfort in a region where the winters are particularly harsh.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

A different form of protection on a Type L wagon, completely enclosed, the sides extended upwards and armoured, but once again armed with a 47mm gun with a very restricted field of fire.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

Machine-gun wagon converted from a goods wagon. Note the camouflage scheme.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

This photo shows an interesting combination: the armoured body of a narrow-gauge wagon has been mounted on a standard-gauge wagon, leaving a slight gap between the two. The result is an armoured wagon which is perhaps more resistant to mines.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

An overall view of Armoured Train No 3 at Novo Mesto, where it was stationed from August 1943. The muzzle of a 47mm Model 32 can just be seen protruding from the side of the third wagon.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

Goods trains were hauled by modern Class 06 engines, with extensive armour protection on the cab, including the door for the crew. The armoured trains were powered by Class FS 910 tank engines.

(Photo: Nicola Pignato & Filippo Cappellano, Gli Autveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano, Volume 2)

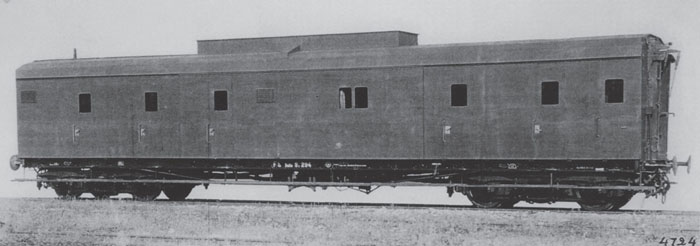

Saloon coach S 294 fitted with armour, seen here in July 1942.

(Photo: Archivo Ferrovie dello Stato Italiano)

In Slovenia and Dalmatia, the Second Army used several Series Dpz and DI coaches, armoured against small-arms fire, to form a command train with ‘passive’ protection, with no heavy armament and organised like a troop transport train, with sleeping accommodation, kitchen and so on. The windows were replaced by several armoured blinds.

A view of the end of the coach. The armour plates have been riveted to the original bodywork.

(Photo: Archivo Ferrovie dello Stato Italiano)

A view of the former baggage van Dpz 1913 converted into an armoured coach, intended for the command train SLODA (for SLOvenia-DAlmazia).

(Photo: Archivo Ferrovie dello Stato Italiano)

Although improvements to the protection and the armament of the wagons can be observed as the occupation continued, the Italian trains in the Balkans were not intended for an offensive role, which would be the province of the railcars and trolleys.

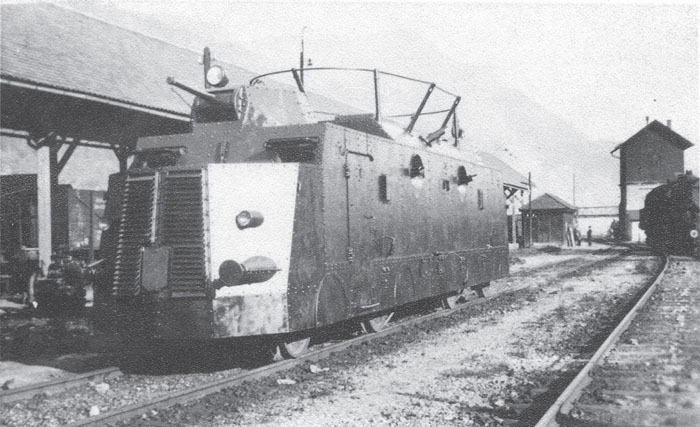

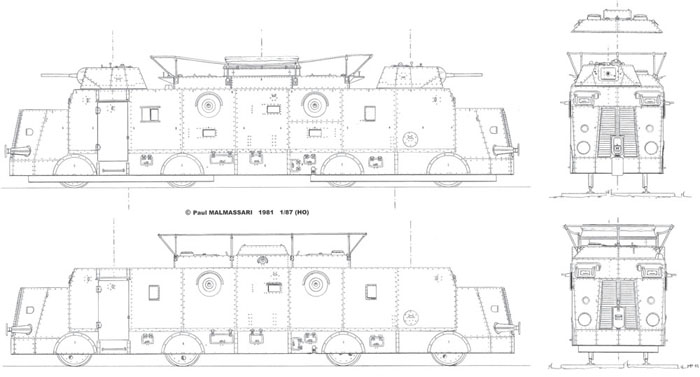

In 1942 it was decided to armour the ALn-556 railcars of the Ansaldo firm, for service in Yugoslavia. The Railway Engineers chose models produced from 1936 to 1938. They had to be shortened by 5.60m (18ft 4½in). The prototype was tested in the Ansaldo-Fossati workshops in Genoa, and was adopted on 5 September 1942, with several recommended changes, with the designation ‘Littorina blindata mod. 42 (Li.Bli 42)’. The first production model was rolled out on 20 September and joined the 1o Compagnia Autonoma Littorine Blindate. This company would receive eight railcars in total, and was made up of ten officers, twelve NCOs and 167 men. The 8.5mm armour protection was built in one piece, pierced only by access and maintenance hatches, and firing ports.

Armed with two tank turrets mounting 47mm guns, two versions were used at the same time. The first version had two openings in the roof to allow firing two 81mm Model 35 mortars, or flamethrowers through side apertures. The second had a circular tub with a pedestal-mounted 20mm Breda Model 35 cannon. The 8.5mm armour protection was built in one piece, pierced only by access and maintenance hatches, and firing ports.

When the Italian Armistice was signed, the ‘Liblis’ were based at Karlovac, Ogulin and Split (Croatia), Ljubljana and Novo Mesto (Slovenia) and Suse (in Italy, 30km/19 miles west of Turin). A series of machines was then ordered for the Wehrmacht in 1943 (see the chapter on Germany).

The Independent Railway Company saw hard service up until the Armistice of 1943, and suffered heavy losses. In particular two ‘Libli’ were destroyed, the first at Split in October 1942 and the second at Ogulin on 12 February 1943.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

| Length: | 13.50m (44ft 71/2in) |

| Width: | 2.42m (7ft 111/4in) |

| Height: | 3.57m (11ft 81/2in) |

| Weight: | 39.5 tonnes |

| Motor: | FIAT 355C, 80hp at 1700 rpm |

| Fuel: | Diesel |

| Maximum speed: | 80km/h (50mph) |

| Range: | 450km (280 miles) |

| Armour thickness: | 8.5mm |

| Armament: | 2 turrets similar to those fitted to the M13/40 tank, with 47mm/L32 gun with 195 rounds and 8mm Breda 38 machine gun Either 2 x 81mm Mod. 35 mortars with 576 bombs Or 1 x 20mm Breda Mod. 35 anti-aircraft cannon 2 Mod. 40 flamethrowers 4 x 8mm Breda 38 machine guns in side ball mountings with 8,040 rounds The personal arms of the crew and hand grenades |

| Crew: | 1 officer, 2 drivers, 2 gunners, 2 loaders, 6 machine gunners, 2 mortar specialists, 2 flamethrower engineers, 1 radio operator |

| Radio equipment: | Marelli RF2CA or RF3M set |

| Various: | Turret searchlights, track repair equipment. |

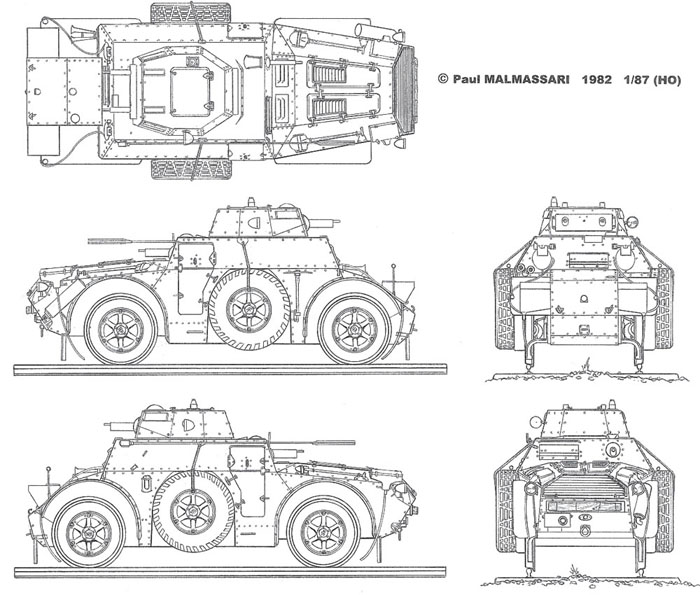

To supplement the ‘Libli’ railcars, a request was made on 24 July 1942 for the conversion of twenty AB 40 and AB 41 armoured cars into road/rail vehicles, to be used equally on the road or on rails simply by changing the wheelsets. The modifications also included adding sanding boxes to the front and rear wings, and one swivelling headlight. The first version could be recognised by its low turret armed with two 8mm Breda Model 38 machine guns. The AB 41 received a higher turret, an automatic 20mm 20/65 cannon and one Breda machine gun. Lastly, the AB 43, of which only an experimental model existed in road/rail form, mounted a 47mm gun.

An AB 40 of the 2o Raggrupamento genio ferrovieri. The sanding boxes and delivery pipes are clearly visible. The armament comprised three 8mm Breda 38 machine guns, two in the turret and one in the hull rear. Stoneguards were fitted in front of each rail wheel to aid in pushing aside small obstacles.

(Photo: Daniele Gugglielmi Collection)

We are unable to say whether this camouflaged AB 41 is still in Italian hands or if it has been taken over by the Germans. The cannon is a 20mm Breda 35. This machine had a rear driving position, and therefore had no need for a turntable.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

| Length: | 5.20m (17ft) |

| Width: | 1.935m (6ft 4in) |

| Height: | 2.44m (8ft) |

| Ground clearance: | 35cm (133/4in) |

| Weight: | Between 6.9 tonnes and 7.7 tonnes |

| Motor: | FIAT-SPA ABM1, 6 cyl inline |

| Power: | AB 40: 88hp at 2700 rpm; AB 41: 108 hp at 2800 rpm |

| Fuel: | Petrol |

| Maximum speed (road): | 78km/h (49mph) AB 40; 81km/h (51 mph) AB 41 |

| Range (road): | 400km (250 miles) AB 40: 350km (215 miles) AB 41 |

| Armour thickness: | 8mm |

| Armament: | 3 x 8mm Breda 38 machine guns (AB 40); 1 x 20mm Breda 35 cannon and 2 machine guns (AB 41) |

| Crew: | 4 |

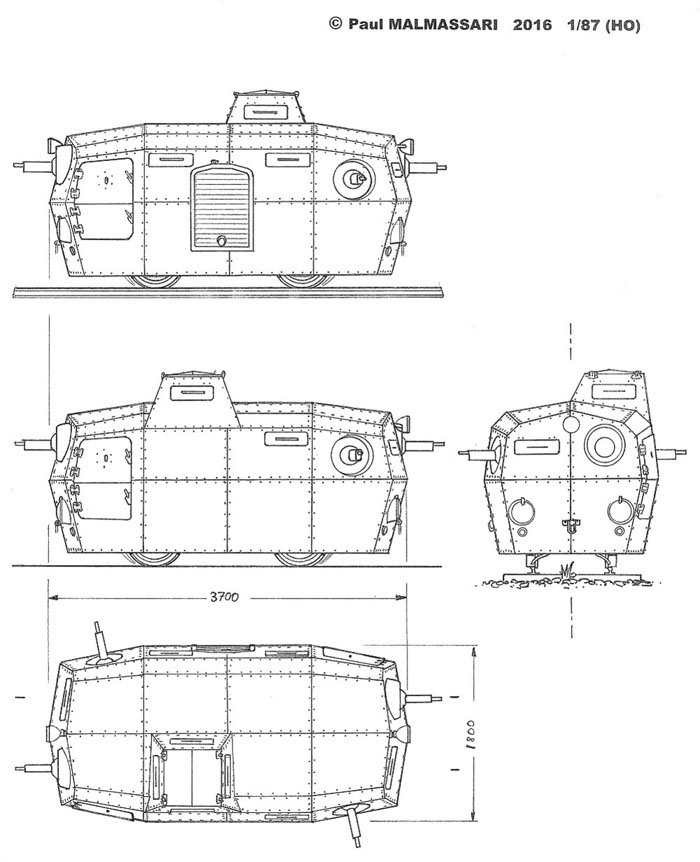

Derived from the Autocarretta OM36, twenty examples were built for the Railway Engineers. After prototype testing in late 1942, the machines were put into production in early 1943 and entered service in May 1943 on the narrow gauge (76cm/2ft 6in) lines in Dalmatia and Slovenia. After 8 September 1943, they continued in use with the Wehrmacht.

Technical specifications:

| Length: | 3.83m (12ft 63/4in) |

| Width: | 1.535m (5ft 01/2in) |

| Height: | 2m (6ft 63/4in) |

| Ground clearance: | 12.5cm (5in) |

| Weight: | 3.2 tonnes |

| Motor: | FIAT-SPA AM, 4 cyl inline, 20hp at 2400 rpm |

| Fuel: | Petrol |

| Maximum speed: | 15km/h (10mph) |

| Range: | 350km (215 miles) |

| Armour thickness: | 8mm |

| Armament: | 1 x 8mm Breda 38 machine gun |

| Crew: | 6 |

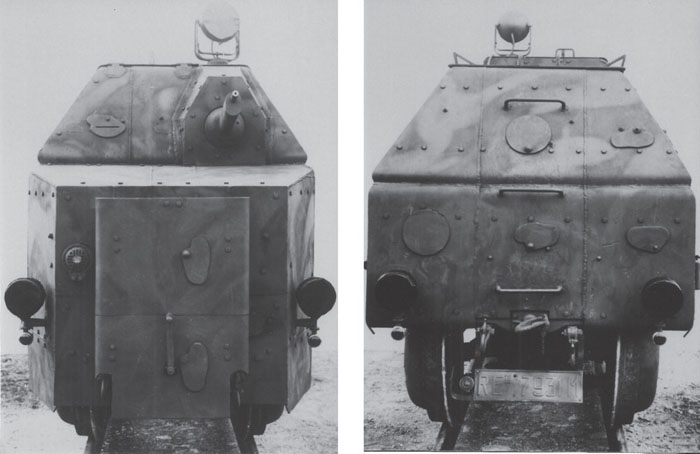

This three-quarter front view shows clearly the turning mechanism of the type normally used on asymmetrical trolleys, but which was extremely dangerous to operate under combat conditions. Note also that the only means of access is via the roof, making a turning manoeuvre even more perilous.

(Three Photos: Daniele Guglielmi Collection)

The front view shows the modest dimensions of the machine, which would have been relatively uncomfortable for its crew. The front plate, pierced by the emergency starting-handle, protects the radiator air intake.

In this rear view of the trolley, note the numerous firing and observation loopholes, plus the handrails which were the only means of climbing on the vehicle.

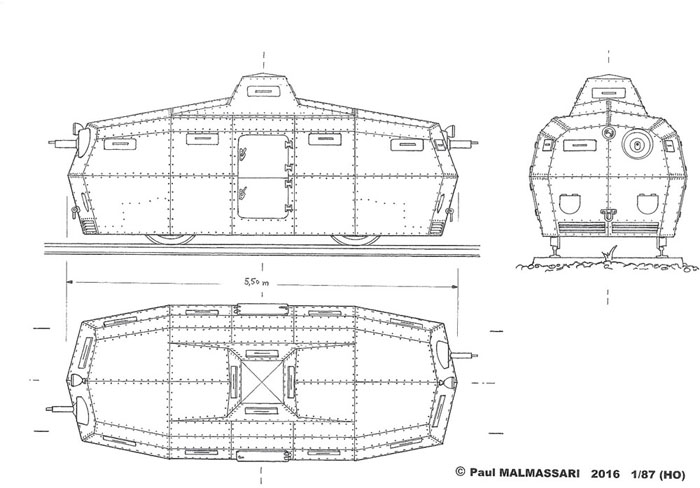

Two further projects were being studied in the Summer of 1943: the firm of Viberti had designed two trolleys (one for the narrow gauge and the other for the standard gauge) which did not go into production because of the Armistice. Extremely compact, they had probably benefitted from experience gained with the Autocarretta Mod. 42, despite the weakness of its armament and armour protection.

It would be simple to see in the defeat of the Axis Powers in the Balkans the failure of the means of defending the railway network. It is the case that the Italians were never able to prevent sabotage of the communications links, but the escort missions and the reconnaissance patrols carried out day after day by the Independent Company and the Railway Militia prevented the complete paralysis of the communications and supply lines in the Balkans. Lastly, the excellent qualities of the ‘Liblis’ are attested by the production orders and use by the Wehrmacht after 8 September 1943 in the zone which would now be known as the OZAK (Operationszone Adriatisches Küstenland, Adriatic Coast Operations Zone).

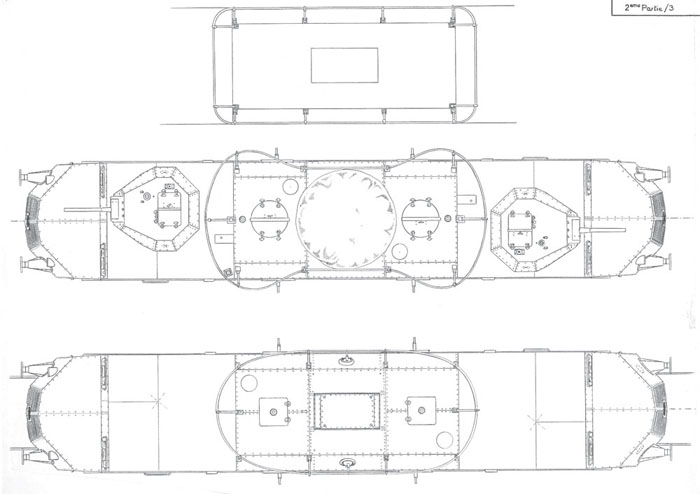

At some time, probably in the early 1920s, Anslado proposed an armoured engine, and also an armoured railcar. Although the drawing for the railcar is annotated in French, no record of a specific request for this project has come to light in the French archives. The inclusion of Saint Etienne Model 1907 machine guns in the plan suggest it was intended for use in French North Africa, probably Morocco. Interestingly, the plan also depicted the Ansaldo version of the stroboscopic observation device on the turret, similar in concept to that fitted to the French FCM Char 2C.

SOURCES:

Benussi, Giulio, Treni armati treni ospedale 1915-1945 (Parma: Ermanno Albertelli Editore, 1983).

Guglielmi, Daniele, Italian Armour in German Service 1943-1945 (Fidenza: Roadrunner, 2005).

Luparelli Albion, Filippo Ettore, La Sicilia nella probabilità di una invasione francese (Palermo: Michele Amenta, 1884).

Pignato, Nicola, Atlante mondiale dei mezzi corazzati, i carri dell’Asse (Bologna: Ermanno Albertelli Editore, 1971, 1983).

____________, Un secolo di autoblindate in Italia (Fidenza: Roadrunner, 2008).

____________, and Cappellano, Filippo, Gli Autoveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano (Volume 1) (Rome: Uffico Storico SME, 2002).

________________________________, Gli Autoveicoli da combattimento dell’Esercito Italiano (Volume 2) (Rome: Uffico Storico SME, 2002).

Plan of the Viberti trolley for the narrow gauge (76cm).

Plan of the Viberti trolley for the standard gauge.

1. The story of the Italian armoured trains in Libya ends in 1943, when Italy lost control of the country, renouncing all rights to Libya in 1947, the last Italian colonists being expelled in October 1970.