Living with Health, Happiness, and Freedom

Now that you’ve made it through the 4×4 and the reintroduction phase, the big question is—what’s next? You’ve most likely discovered that some foods don’t make you feel good, while others are just fine. Or maybe you didn’t have any negative reactions, but you’d like to reduce your overall intake of certain foods for health reasons. While it would be easy to tell you to just eliminate those foods and leave it at that, we know how challenging it can be to make changes long-term without feeling deprived or getting stuck in the shame cycle (because yes, we’ve been there).

No strict elimination diet is successful in the long run, and you don’t need to always be “on” the 4×4 to be healthy. Temptations, situations, and priorities come and go. This is perfectly fine. In fact, we actively embrace the messiness of life. Health is not about perfection; it’s about being well—physically, mentally, and emotionally.

To help you facilitate the appropriate mind-set and live with health, happiness, and freedom beyond the 4×4, we’ve put together a list of the most important factors in supporting your physical and mental health. These principles will help you see how the 4×4 fits into the bigger picture, and protect you from living out the rest of your days trapped in the diet mentality.

SUPPORTING YOUR PHYSICAL HEALTH

When it comes to supporting your physical health long-term, there are three key principles to follow: (1) remain flexible, (2) eat nutrient-dense foods, and (3) optimize digestion and gut health. By focusing on these three things, you will create an incredibly solid foundation to operate from.

1. REMAIN FLEXIBLE

Now that you know which foods work best for your body, the number one thing you can do for your health is remain flexible. Your body doesn’t have the exact same needs from day to day because it is dynamic and ever-changing. This means the number of calories and quantities of macronutrients you need will change, too. By staying in tune with what your body needs, you give yourself the freedom to fluctuate. You allow yourself to work with your body instead of against it.

Many people get stuck because they believe that if something works now, it will work forever. Or they think they need to always limit their calories to a set amount each day. This mind-set can be disastrous long-term, as it can lead to calorie and nutrient deficiencies that can stress your body. A body that is under chronic stress is unable to function optimally, especially when it comes to metabolizing food.

So remember this: there is nothing more important than eating enough and providing your body with all the nutrients it needs. Focus on meeting your minimums (as described in chapter 1) and add more food as you see fit. Some days, 2,000 calories may be just right. On others, you may need much more. The same goes for the amount of protein, carbs, and fats you consume. While you may feel best eating more fat right now, in a year or two you may feel better eating more carbs. There is no set number of calories (or carbs) you must limit yourself to in order to be healthy long-term. Simply focus on eating the foods that make you feel good, and eating enough of them.

2. EAT NUTRIENT-DENSE FOODS

Western culture tends to classify a food as “good” or “bad” based on the number of calories it contains. While calories—the energy a food provides—do play a part in how a food affects the body, they don’t actually say anything about the food’s nutritional value. For example, a single serving of Froot Loops cereal has 150 calories, while two fried eggs have about 180 calories. Some conventional advice would say that the better choice would be the cereal because it has fewer calories and less fat, although its nutritional value is much less overall. This thinking led to the explosion of cereals, breads, and bagels as breakfast foods in place of traditional, nutrient-dense foods such as eggs.

Focusing on nutrient density often means you’re much more satisfied with less food. Studies have found that consuming eggs not only increases satiation, but also results in eating up to 400 calories less throughout the day when compared to an equal-calorie breakfast of a bagel.1, 2

When you stop restricting calories and instead focus on food quality, your body functions better. You have more energy, you feel more satiated after meals, and you are better able to trust your body to tell you how much to eat and when to stop. This is what it’s like to have a healthy relationship with food. You eat when you are hungry, and you eat the things that make you feel good—both physically and emotionally.

In chapter 2, we talked about the Big Four—foods that tend to cause negative reactions and can actively deplete the body of nutrients. These foods are not inherently bad, but a diet high in these foods can absolutely lead to nutrient deficiencies. In contrast, there are many foods that enrich the body’s nutrient status. Here we’ve included a list of the big hitters when it comes to nutrient density. As a general rule, we recommend consuming each of these at least two or three times a week.

DARK LEAFY GREENS

It’s no secret—vegetables are good for you. They’re anti-inflammatory and rich in antioxidants, which protect the body from damage caused by harmful molecules like free radicals. Vegetable-rich diets have repeatedly been linked to lower incidences of disease and better immune system function, as well as reduced risks for heart disease and cancer. In short, there is almost no such thing as eating too many vegetables.

Some of the most nutrient-dense vegetables are dark leafy greens. These include spinach, kale, chard, lettuce, collard greens, beet greens, endive, arugula, and mustard greens. Dark leafy greens are rich in vitamins A, C, E, and K; B vitamins; folate; and calcium. They’re particularly important for women who are pregnant or trying to get pregnant, as folate is crucial for the development of the baby’s brain and spinal cord.

GRASS-FED BEEF AND OTHER RUMINANT MEAT

Meat, particularly red meat, has been unfairly blamed as the root cause of many health issues, particularly heart disease. Every year or two, a new study comes out, is turned into a sensational headline, and is shared on social media, and the myth continues. But you can rest assured that almost all of the research that shows that red meat is “bad” comes from observational studies, which only demonstrate that there’s a statistical relationship between reported red meat intake and health, and not that red meat intake is the cause of poor health. The people in these studies are eating red meat mostly from fast food, which is sourced from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). There is no regard for quality or source.

Additionally, these studies are flawed because of the “healthy user bias”—that is, because red meat has been vilified for years, the people who eat less of it are healthier because they are also likely to participate in other healthy behaviors such as exercising regularly and eating less sugar and fast food. The reality is that traditional cultures consumed greater amounts of red meat and still remained free of the chronic and degenerative diseases that plague our modern culture. We might have ninety-nine health problems, but meat (especially grass-fed meat) in our diet isn’t one.

Beef, lamb, bison, game, and other ruminant (grazing) animals are incredibly nutrient-dense sources of essential amino acids, as well as important vitamins such as B vitamins (including B12), vitamin D, iron, zinc, and more. When it comes to how an animal was treated as it lived on the earth, it’s often said that “you are what they eat.” For this reason, it’s best to prioritize grass-fed meat, ideally from local farms and producers. (See here for more information on the differences between grass-fed and grain-fed beef.)

LIVER AND OTHER ORGAN MEATS

Liver is possibly the most nutrient-dense food, packed with enough vitamin A in one pound to nourish a family of five for a month. It is also the best source of all the B vitamins and contains copper, iron, and fat-soluble vitamins, including A, D, E, and K. Liver from nearly any animal will pack a nutrient-dense punch, but liver from grass-fed cows is especially powerful because it contains vitamin K2, which is essential for a healthy metabolism, heart, bones, and skin.

Liver is the most nutrient-dense organ meat, though hearts and kidneys are also great options.

EGGS

Contrary to popular belief, studies show that a diet rich in eggs will not cause heart disease or lead to unwanted weight gain. In fact, eggs contain tons of vitamins (we often call eggs “nature’s multivitamins”). One of these is choline, a very rare but very important nutrient that prevents fatty liver disease and supports the body’s natural detox mechanisms.

Importantly, the vast majority of an egg’s nutrients are contained in the yolk. This means you’ll want to eat the whole egg in order to get all the wonderful benefits.

WILD-CAUGHT FISH AND OTHER SEAFOOD

Salmon and other fatty fish contain high levels of vitamins D and A, as well as omega-3 fats. This supports the immune system, enhances cardiovascular health, strengthens the metabolism, and is key for having a healthy, happy brain. Examples of wild-caught fish dense in omega-3 fats include salmon, trout, and sardines. Examples of nutrient-rich shellfish include scallops and oysters, both of which are high in zinc.

BONE BROTH

Bone broth (or stock) is a nutritional powerhouse rich in collagen, amino acids, and the minerals necessary for strong bones, teeth, and skin, especially as you age. It also has a rare and important effect of helping to heal the gut lining. It’s easy to make (see here) and you can use it in soup and stew recipes, or sip it from a mug in the morning.

3. OPTIMIZE DIGESTION AND GUT HEALTH

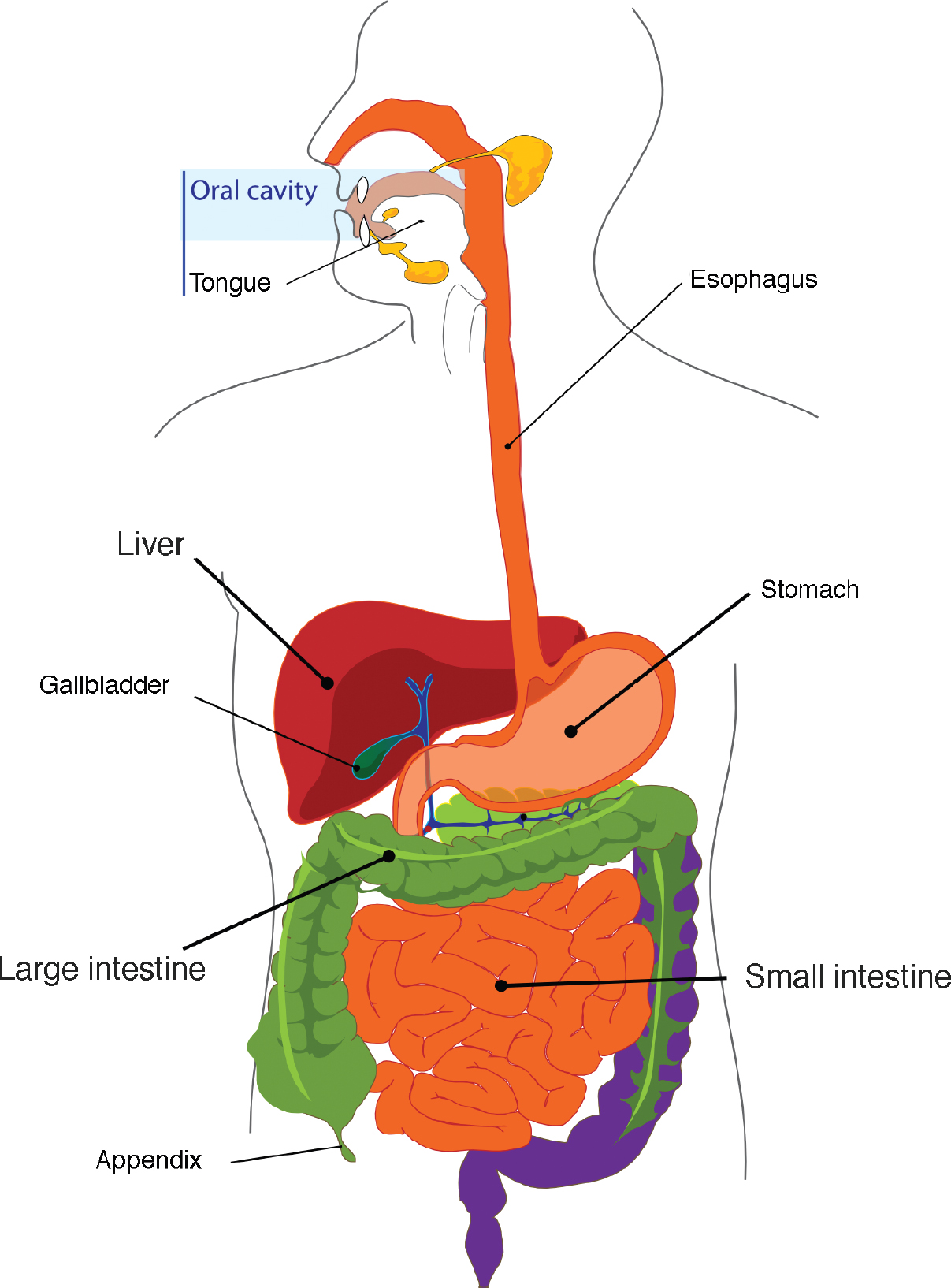

The evidence is clear. In order to have a healthy body, you must also have a healthy gut. The gut, also known as the gastrointestinal tract, is the long tube that’s responsible for digesting the food you eat. In order to have a healthy gut, all the digestive processes must be supported and working properly.

THE PROCESS OF DIGESTION

When you sit down to a meal, the sight and smell of food triggers both saliva and stomach acid production, which prepare your body to eat food. Studies show that merely talking about food can stimulate digestive fluids, which is why commercials that talk about how wonderful a food tastes while showing you beautiful, appetizing images make you immediately want to eat the screen.

Once food is in the mouth, chewing mechanically breaks it down and mixes it with saliva. Saliva is much more than a mouth-moistening system: it actually contains electrolytes, antimicrobial agents, and enzymes that begin the chemical breakdown of food. This is why chewing food thoroughly before sending it downstream to be further digested is incredibly important.

Swallowing the chewed food (now called a bolus) sends it down the esophagus, and the cardiac sphincter at the bottom of the esophagus opens to allow the bolus to pass into the stomach. The stomach then secretes gastric juices to help “churn and burn” food. Both stomach acid and pepsinogen (a proenzyme that turns into the enzyme pepsin when it comes in contact with stomach acid) help to break down proteins into smaller strings of amino acids. Once the gastric juices have done their duty, the partially digested food (now called chyme) is released into the small intestine through the pyloric sphincter.

The Organs Involved in Digestion

The small intestine is the star of the show when it comes to digestion. Essentially, it’s a twenty-foot-long muscular tube that is responsible for the absorption of nutrients from food. When chyme enters the first part of the small intestine, the acidity triggers the secretion of two hormones into the bloodstream, secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK). These two hormones communicate to other organs in the body that nutrients have entered the small intestine. Secretin stimulates the pancreas to release pancreatic juices into the small intestine, which raises the pH of the chyme and further breaks down the nutrients it contains, and CCK stimulates the gallbladder to release bile, which helps to emulsify fats so they can be absorbed into the body.

As the chyme travels through the small intestine, it becomes almost completely digested. Millions of villi and macrovilli (those tiny, finger-like projections lining the walls of the small intestine) absorb the nutrient molecules and pass them into the bloodstream.

Anything that is left over, including indigestible (insoluble) fiber, bile, water, and sloughed-off cells, then passes through the ileocecal valve into the large intestine. Here the water and nutrients are absorbed, and gut bacteria ferment indigestible materials and produce vitamins such as vitamins K and B12 and butyric acid. These nutrients are crucial for helping the digestive system function properly, as they nourish the gut lining and have even been shown to protect against colon cancer.

Any remaining undigested material ends its travels in the rectum and is eventually excreted.

DIGESTION: WHEN THINGS GO WRONG

In the Brain

When the body perceives stress, digestive functions are down-regulated in order to divert resources to the “fight or flight” response. Eating food in a stressed, or sympathetic, state can lead to issues such as gas, bloating, and diarrhea and disrupt the gut microbiome long-term. The body needs to be in “rest and digest” mode—or a parasympathetic state—for digestive processes to work properly. To help your body transition into a parasympathetic state before you eat, take 1 to 3 minutes to breathe deeply, or take a moment to pray or feel thankful for your food. It’s also important to avoid eating in a stressful environment, such as at your desk at work or when driving, and to proactively seek out places that allow you to eat in a calm state.

In the Stomach

Stomach acid is a digestive fluid secreted in the stomach. It’s responsible for breaking down food, killing any pathogenic bacteria that may have come along for the ride, and maintaining an acidic pH (1.5 to 3.0) in the stomach. It’s estimated that 90 percent of people have chronically low stomach acid due to eating too fast, not chewing their food well enough, stress, nutrient deficiencies, and diets high in refined foods. When stomach acid isn’t sufficient, large, undigested food particles and pathogens make it into the intestines, which can cause bloating, gas, diarrhea, constipation, and dysbiosis. To support stomach acid production, always chew your food thoroughly and prioritize eating in a parasympathetic state. If you suspect you have low stomach acid, drink 1 teaspoon apple cider vinegar in 1 cup water prior to meals.

In the Gallbladder

The gallbladder is a small organ located just beneath the liver that stores and releases bile. Though small in size, the gallbladder is a big player in digestion. When gallbladder function is impaired, which can be caused by, among other things, a diet high in vegetable oils, the body is unable to break down fats or absorb fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K. Common symptoms of a sluggish gallbladder include bloating, indigestion, fatigue after meals, light-colored stools, and diarrhea. If you suspect you aren’t digesting fats properly, consuming beets regularly can help stimulate bile flow from the gallbladder. If your gallbladder has been removed entirely, it’s important to take an ox bile supplement when eating a meal that contains fat; the ox bile will break down the fat in place of the bile from the gallbladder.

TAKING CARE OF YOUR GUT

While all the organs involved in digestion are important, much of the focus in the last decade has been on the health and integrity of the small and large intestines. This is because they are the primary surface of the body where an exchange happens between us and the exterior world. As a result, more than 70 percent of the immune system resides in the intestines.

That’s big news, so it’s worth repeating: your gut is inextricably linked with your immune system.

There are two parts to consider when talking about gut health: the microbiome, which is essentially all the bacteria that live in the gut, and the lining of the intestines. There are trillions of microorganisms in the gut—three to four pounds of bacteria, to be exact—and the health of your microbiome directly impacts the lining of your gut. Research shows that the health of the gut microbes and the integrity of the gut wall both have a profound effect on the body’s ability to fight disease. Because of this connection, research surrounding some of the most complex diseases is now focused on the health of the gut and its relations to those diseases.

Unfortunately, many aspects of Western civilization have drastically decreased our exposure to beneficial microorganisms. Since the industrialization of food began in the late nineteenth century, consumption of traditional cultured and fermented foods, which are packed with probiotics, has taken a nosedive. Western children also spend more time inside and less time outdoors in nature, which helps inoculate the gut with microbes early in life.

The many other factors that can negatively impact gut health include:

- Antibiotics

- Medications such as NSAIDs and birth control

- Processed foods high in refined sugars and vegetable oils

- Exposure to foods the body is intolerant to

- Chlorine (typically found in tap water)

- Meat from animals exposed to antibiotics

- Chronic stress

- Nutrient deficiencies

- Lack of sleep

- Recurring gut infections

While the best way to maintain a healthy gut is to remove each one of these stressors, for most of us, that’s unrealistic. This is why it’s incredibly important to incorporate intentional gut-health strategies long-term.

Gut-Healing Strategy #1: Consume Probiotic Foods

Probiotics are live microorganisms that have beneficial qualities. While probiotics are everywhere, they’re mainly found in soil and food and can be cultivated through preservation techniques such as fermentation. Popular fermented foods include raw (unpasteurized) sauerkraut, kombucha, kimchi, pickles, kvass, and grass-fed kefir and yogurt.

Regularly consuming probiotic-rich foods helps maintain a healthy balance of bacteria in the gut. When gut bacteria are healthy and flourishing, digestion functions appropriately and the immune system is balanced and able to fight disease.

To help gut microbes flourish, you also need prebiotics, which are nondigestible carbohydrates that act as food for probiotics in the gut. Prebiotics are found naturally in certain foods, including onions, garlic, asparagus, bananas, and leeks.

It’s important to note that while probiotic supplements definitely have their place, building a healthy, robust, diverse colony of gut microbes is best done with a coordinated effort that includes both fermented foods and supplements.

If you’re new to fermented foods, consume a small amount (1 to 2 tablespoons) each day for one to two weeks. After that, slowly increase your consumption until you’re eating at least one serving (for example, ¼ cup sauerkraut or 1 cup kombucha) daily. Experiment with different kinds of probiotic foods, and consider switching up the types of foods you’re consuming each week, as different probiotic-rich foods contain different probiotic strains.

Keep probiotic supplements on hand for times when you can’t consume fermented foods, such as when you’re traveling. Supplements are also good when digestive issues strike (constipation, diarrhea, and so on) that could disrupt gut microbes, and when you’re taking antibiotics, which wipe out good and bad bacteria indiscriminately. Stick with high-quality probiotic supplements that have at least 10 billion CFU per capsule, and switch brands occasionally to diversify your exposure to probiotic strains.

Gut-Healing Strategy #2: Drink Bone Broth

After a long period of simmering in water, the bones, bone marrow, tendons, cartilage, and ligaments of pasture-raised animals release healing compounds, including collagen, proline, glycine, glucosamine, chondroitin sulphates, and glutamine. While all these nutrients are incredibly beneficial for the body, glutamine and collagen have specific gut-healing qualities.

Glutamine is an amino acid that is the primary fuel source for gut cells, and has been shown to enhance gut barrier function. Collagen is vital for the body and lends strength and structure to tendons, muscles, skin, hair, bones, and joints. The breakdown of animal collagen in bone broth produces gelatin, which soothes the gut lining, improves gut integrity and digestive function, and can increase gastric acid secretion. Bone broth is also packed with minerals, including calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, silicon, sulfur, and other trace minerals, in forms the body can easily absorb.

Bone broth is easy to make (you’ll find our recipe here), and we recommend drinking 4 to 6 ounces of bone broth daily (or using it in soups and stews). You can of course adjust the amount you consume depending on your body’s needs. You can add collagen to your diet by supplementing with grass-fed beef gelatin or collagen peptides, which are both available in powder form. Beef gelatin will gel when added to liquids, making it great for homemade gummies, like the Watermelon-Lime Gummies. Collagen peptides do not gel and can be stirred into hot or cold liquids, smoothies, soups, or stews without adding any noticeable flavor.

Gut-Healing Strategy #3: Manage Stress

It’s highly likely that, as an individual living in the twenty-first century, you’re familiar with stress and experience it on a regular basis. Stress—put simply—is the body’s response to a specific physiological or psychological demand, or stimulus. While the majority of stress is negative, stress can also be positive and lead to beneficial adaptations.

Despite being well aware of the harmful effects chronic stress can have on health, most people aren’t proactively doing anything to mitigate their stress level. Managing stress often means changing or modifying established behaviors, and, well—that can be stressful. Unfortunately, without stress management, the body is much more susceptible to disease.

When we are under stress, whether from driving in traffic, sleep deprivation, working in a high-stress environment, or eating foods that create an inflammatory reaction, the body must divert resources to respond to that stress. If stress isn’t managed appropriately and becomes chronic, many of these resources become depleted, and a chronic elevation of hormones involved in the stress response, such as cortisol, can create major imbalances in the body.

Studies show that chronic stress is linked to a number of conditions, including blood sugar dysregulation, weight gain, depression and anxiety, hormonal imbalances, a weakened immune system, cardiovascular disease, and damage to gut wall integrity. In short, if you aren’t managing stress, all efforts to improve gut health will be ineffective.

While all the typical recommended stress-relieving activities can help, perhaps the best way to manage stress is to be mindful of it. Simply taking one to three minutes to breathe deeply and clear your mind when you feel anxious or stressed will help your body shift from a sympathetic state into a parasympathetic state. Incorporating intentional parasympathetic shifts into your day will help you have more control over your inner response to stress and prevent the “flight or fight” response from dominating everyday life. Other activities that can effectively facilitate this shift include spending time outdoors, listening to music, massage, acupuncture, going for a short walk, and meditating.

SUPPORTING YOUR MENTAL HEALTH

We firmly believe your mental health is just as important as your physical health. Unfortunately, many people become overly focused on controlling the things that impact their physical appearance—like food and exercise—and sacrifice their mental health in the process. This is largely because of the messaging we receive starting at a young age: It is better to be smaller, and your worth as a human being is directly linked to what you look like.

The underlying tone of you aren’t good enough is pervasive in our culture. Shame sells, and if you feel like you need to be something else in order to be worthy, valued, and happy, you’ll buy whatever is being sold that promises to help you get there. Constant exposure to this kind of messaging—which is pervasive in the diet and weight-loss industry—has resulted in most women feeling incredibly dissatisfied with their bodies. And oddly enough, the more women engage with diets or special fitness challenges that promise to “fix” them, the worse it gets.

We do not want that life for you. We both lived it for years—constantly chasing after a “better” body, hoping to finally find happiness in the next diet plan or fitness protocol. It’s an endless road, and it almost never leads to health or a happier life. What does is pursuing health from a place of self-love, and knowing there is absolutely nothing “wrong” with you. You don’t need to change your physical appearance to be worthy of love and attention: you are worthy of it right now.

Approaching health with this mind-set can change everything. It can change how you feel about your body and the actions you take to care for it. To help you facilitate this mind-set, we’ve compiled five important truths to live by. Understanding these truths will allow you to break down many of the lies you’ve been told and rebuild new conversations around your body, food, and health.

1. SELF-LOVE IS UNCONDITIONAL

Here is an incredibly important fact, perhaps the most important of all: You are supremely lovable, no matter what you eat, how you look, or the status of your health. You do not have to be a certain weight, shape, or size to love your body. You are worthy, right now—in this moment. There is no correlation between changing your outward appearance—like becoming leaner or gaining a six-pack—and becoming more lovable. Your worth is valid because you are human. There are no conditions to this.

The diet and weight-loss industry is masterful at getting us to believe that if we achieve a specific body weight or shape, we’ll become more desirable, attractive, and happy. When you believe this—and see your worth as conditional upon it—behavior change is driven by negativity. When your actions are rooted in negativity, you prioritize choices that provide short-term solutions. You eat less even though you feel hungry. You work out longer even though you feel overly fatigued. You judge yourself—and others—more harshly and start comparing yourself to every person you come in contact with.

While this might come as a surprise, operating from a place of self-hate doesn’t actually lead to health, happiness, or more satisfaction with your body. In fact, it results in exactly the opposite. It puts you in a position to constantly fight your body to make it become something else. In contrast, when you pursue health from a place of self-love, you make decisions according to what is going to be right for your body. You know that you are not more or less of a person because of the foods you choose to eat or your ability to maintain a six-pack. You are free to make the choices that are right for you—even if they are “off plan.”

The truth that forever remains is this: Your body is always on your side, always trying to be healthy. You have a body that is strong, alive, and capable of amazing things, and the number of things it does right outweighs everything else. There is no wrong way to have a body, and you can be healthy at a variety of weights, sizes, and shapes. Pursuing health with this understanding will allow you to see health—and your body—in an entirely different light.

2. FOOD DOES NOT HAVE MORALITY

If you’ve ever eaten a food that is unhealthy, or deemed “bad” by all the health gurus, you haven’t done anything wrong. There is no need to feel guilt or shame or beat yourself about it. You aren’t lazy, worthless, or less than. You don’t need to be punished. And you certainly aren’t a bad person. Furthermore, no one is better than you because they do or don’t eat certain foods—and vice versa. If someone chooses to eat differently from you, that doesn’t make them “good” and you “bad”—it just means you made a different decision.

Food does not have morality, and therefore it is neither “good” nor “bad,” so your food choices have no bearing on your morality. Of course, some foods are more nutrient-dense than others, and there may be foods that are detrimental to your health and don’t make you feel well. But this does not mean those foods are inherently bad. Food is simply stuff you eat. Food is neutral.

Giving food morality means giving the power to the food, and when food has the power, your interactions with food will be accompanied by fear, anxiety, and judgment. This makes it virtually impossible to have any sort of balance or consistency when pursuing health. Punishing behaviors such as negative self-talk, overexercising, and caloric restriction are used to balance the scorecard and make “wrong” actions “right” again. Choices aren’t made from a place of self-love; they are made to eliminate shame.

We invite you to remember that you are human and vulnerable. It is normal to want to be loved, respected, and desired. This yearning creates in you—in all of us—the fear of being rejected. It creates a fear of inferiority. It creates a fear of failure, a fear of being unacceptable. We both know this very, very well. We have suffered through years of self-tortured, self-defeating agony. After years of dieting, the number of times we’ve beaten ourselves up by going to the gym or starving ourselves after eating like we “shouldn’t” is more than we can count. In the end, it never led us to a place of greater physical—and certainly never psychological—health. It always made us more entrenched, more self-critical, and more prone to uncertainty and doubt.

To overcome this mentality, we encourage you to dig into your psyche and expose your insecurities. If you do experience shame or guilt when you eat certain foods, ask yourself why. Dig deep into your attitude, your beliefs, and your history. Grab a pen and paper, and explore your feelings. Figure out what fears and motivations live deep inside you. Are you afraid of losing perceived authority? Are you afraid of not being in control? Or are you afraid of gaining weight? If you are, ask yourself why. Is it because society has made you believe you are unlovable or unworthy if you gain weight? If this is true—as it is for many people—it is important to convince yourself that you are wrong (which, to be clear, you are). If you feel the need to meet a certain arbitrary standard of beauty set by, for example, a particular group of your friends or acquaintances, it might be time to find new ones. Life is short, and yours shouldn’t be wasted on people who are quick to judge or don’t share your values.

3. THERE IS NO WAGON

Virtually everyone who has been on a diet or adopted a new way of eating has eventually broken the rules and made a mistake. This occurrence is commonly known as “falling off the wagon,” and represents failure, inadequacy, and lack of willpower. While people tend to put an enormous amount of pressure on themselves to stay on the wagon, the truth is, there is no wagon. In fact, the wagon mentality is often why many people struggle to remain consistent.

The wagon we all refer to is really just a strict set of rules we hope will give us more control over our health, body, or other people’s perception of us. When you’re following the rules, you’re in the wagon, and when you break a rule—you’re out. This mentality can be incredibly ineffective at creating long-term behavior changes because it turns the pursuit of health into an all-or-nothing gambit: instead of enjoying a cookie, then going back to eating the foods that make you feel your best, breaking a rule results in working your way through an entire tub of cookie dough in a matter of hours.

Worst of all, the wagon mentality keeps you stuck in the shame cycle (see here). Falling off the wagon results in feelings of guilt and shame, and that shame often drives people straight into the arms of punishing behaviors such as more restriction and more rules, which become the new wagon. Each time perfection isn’t maintained, it results in defeat, self-criticism, and desperation, and the only way to rectify these feelings is to get back on the wagon, which starts the process over again. This never-ending cycle is incredibly physically, mentally, and emotionally taxing, and can drain all the enjoyment from experiences involving food.

To stop the cycle, you must get out of the imaginary wagon. This does not mean throwing in the towel on pursuing health. It simply means understanding that the pursuit of health is a journey. There is no “on” or “off”—there is life, and your experiences help you learn what is going to serve you best in the long run. This allows you to nourish your body throughout all seasons of life without having to muster up the motivation to start over or wait until the conditions are just right.

It also means recognizing that health is the result of a number of different factors, including your mental, emotional, and social well-being. It’s not just about what you eat, and eating perfectly is not a requirement of health. Often the mental banter that accompanies stressing about food is more detrimental than the food you are worried about. You can eat a cupcake in good company, enjoy it, and move on. You get to live with more flexibility and mindfulness as you pursue becoming more capable and experiencing all that life has to offer.

This does not mean that abstaining from something that is not serving you is wrong or ineffective. Not being “on the wagon” gives you the freedom to make choices that are right for your body without fear or judgment, or the obsession that often occurs when you categorize a food as “bad” or perceive you can’t have something. All foods are available to you, and you get to make the choice about what you want to eat. There is no such thing as where you “should” be. Not with your body, and not with the food you eat. There is simply where you are and where you are going.

4. YOU DON’T NEED “MORE” WILLPOWER

A lot of people think willpower is the key to health. Eating healthfully is a chore, and you must rise to the occasion. You must set an alarm for five a.m. You must also make sure you work out on a daily basis. Then you must have a protein smoothie for breakfast and an organic kale salad for lunch. If you don’t do these things, you are lazy and less than. You don’t have enough willpower. The people who do work harder at it. They are the ones who make good decisions and deserve praise.

While this is generally accepted as how it all works, willpower is not an inherent quality of the morally superior. It isn’t something you can have “more” or “less” of. Willpower is a skill that is shaped by how you set up your environment. Studies show willpower is a learned behavior. Like strengthening a muscle, the more you use it, the better you get at it. When people are successful at enacting willpower in their lives, it’s largely because they have learned how to minimize the need for it.

You can think of willpower like a glass of water. You pour more water into your glass with positive inputs such as sleeping, eating nutrient-dense food, and using stress-management techniques. Each time you need to use willpower, you “drink” from the glass. Making yourself stay focused at work, resisting the urge to go out for lunch, and holding back from buying a pair of shoes you love all tap into your available water. By the end of the day, you’re dehydrated and running on empty—without any willpower to your name.

To minimize the need for willpower, you must first eliminate fatiguing decisions. This is perhaps the most powerful way to support your mental and emotional health when making changes or following a protocol like the 4×4. If you’d like to stop eating a specific food because it doesn’t make you feel well, removing that food from your home eliminates the need to continually choose not to eat it. Instead of waiting until the morning to decide whether you are going to go for a walk, make the decision the night before. When you get up, move right into it.

Second, prepare and have a plan. If your goal is to cook dinner at home during the week, plan out your meals a few days in advance and prep food for those meals if possible. This will allow you to move right into making dinner when the time comes. It’s also important to plan for the unexpected. If you end up having only twenty minutes to work out instead of an hour, having shorter workouts that you can shift to makes the decision to still work out quick and easy. (Lucky you—this book can help with both of those things!)

Lastly, make the action you want to take the path of least resistance. Small, simple steps can make a huge difference when it comes to deciding whether to take action. By laying out your workout clothes the night before and having your workout space already prepared, you have very little resistance to actually getting up and working out. When you set up these practices, they become habit. When they become routine, they stop being hard. They become easy, normal things about your life that you do every day. This is how you make it sustainable in the long run.

You can also support your mental health by facilitating a mind-set that recognizes your success. Some ways to do this are by positively reinforcing yourself and confidently acknowledging your skills. When you have a “win,” celebrate it! Don’t put pressure on yourself to perform or to be perfect. That isn’t necessary for health, and health and happiness aren’t destinations to be achieved. They are part of the journey. Find ways to feel gratitude for the opportunity to move your body and make healthy choices. Get excited about the potential impact the 4×4 is going to have on your life. If progress feels slow, remind yourself that these things can take time. Anything you can do to give yourself a sense of patience, a sense of gratitude, a sense of excitement, and love for yourself and your new approach to health and wellness will make your journey easier and more joyful.

5. HAVING BODY FAT DOES NOT MAKE YOU UNHEALTHY

The science is now clear: people can be healthy and live long lives at a variety of weights and shapes. It remains true that there is an association between obesity and certain health conditions such as heart disease, but the correlation is much looser than scientists previously thought. In fact, current research has found that body fat does not necessarily create negative health consequences. Instead, weight gain is often a symptom of a disease state in the body. When looking at the validity of how we assess someone’s body fatness—and health—there are also huge inconsistencies. A recent study out of UCLA looked at 40,420 individuals and found that nearly half of “overweight” people and 29 percent of “obese” people (according to the BMI scale) were quite healthy. On the flip side, more than 30 percent of people who were at a “normal” weight were metabolically unhealthy.3 In short, being overweight doesn’t mean being unhealthy, and being thin is no guarantee of good health.

The only way to truly tell if someone is healthy is to know exactly how their body is functioning. Blood tests that look at insulin sensitivity, inflammatory markers, immune function, nutrient status, and hormonal secretions are all great indicators of health status and longevity. These numbers do not necessarily correlate with weight. And in some cases, having more fat on your body is healthier. For example, people who suffer from certain cancers appear to benefit from having more body fat. The basic idea here is that body fat can protect you. Body fat is a rich source of energy. It is also where the body stores all the fat-soluble vitamins you need for good health. Women who have higher body fat percentages also tend to live longer than those who do not. This isn’t the case 100 percent of the time, but it is good reason to refrain from being judgmental about anyone’s size, including your own.

In sum, you do not need to fear your body or your body size. Western society puts significant pressure on people—especially women—to adhere to a specific body type: small, lean, with little body fat. We see no problem with this body type, but we also see no problem with larger ones, too. These high-pressure norms come from media outlets that do their best to make you feel bad about yourself; they actually have very little to do with your health. If anything, they are attempting to worsen your health by making you feel self-conscious and unhappy and driving you to do things like go on crash diets over and over again.

If you do wish to lose weight, that is also totally okay. We have absolutely no problem with the desire to change your body, as long as that desire comes from a place of self-love, and as long as you know you do not need to become something else to be worthy. By eating 2,000 calories a day and setting minimums instead of maximums, it is totally possible and likely that weight loss will happen, especially if your health improves. Changes in body fat percentages that are sustainable and real happen over the long-term when the body feels safe, fed, and healed. There is no way to force weight loss using quick fixes and have the body stay that way. Weight loss must start with healing, first and foremost in your body and mind. Then it simply takes place as a downstream effect.

When approaching health, we encourage you to embrace your body and enjoy all that it is capable of. True happiness doesn’t come from what your body is—what size, what shape—it comes from what your body does. When your happiness is contingent on a specific state of being, happiness is fleeting and fluctuating because bodies fluctuate and change, which is totally normal. Thinking these fluctuations are wrong or bad or make your body unacceptable is the number one way to derail yourself from a healthy way of eating and fall into despair. But how amazing and wonderful would life be if all of us could stop judging ourselves and one another and simply appreciate our bodies for their abilities to sustain life? While this may seem easier said than done, we know it is possible. If we were both able to break free of our judgment of, shame about, and anxiety around our bodies, food, and health, anyone can. All it takes is some time; some good, hard introspection; and a heaping dose of commitment to overcoming what society tries to make you feel about yourself. We hope this book facilitates that journey for you.