Spider mites typically overwinter as females, under rough bark on trunks and cordons. They begin to emerge in early spring. If present in high numbers, they can kill the margins of growing leaves, permanently stunting leaf growth.

The initial (larval) stage of spider mites resembles the adult, except in size and the possession of only three pairs of legs. After feeding, the larvae molt and pass through the eight-legged protonymph and deutonymph states, before becoming sexually mature adults. Under favorable conditions, spider mites can pass through their life cycle in about 10 days. This can lead to explosive population increases.

Spider mites typically feed on the undersurfaces of leaves, injecting their mouth parts into epidermal cells. Initial damage results in fine yellow spots on the leaf. With extensive feeding, the foliage turns yellow in white varieties, and bronze in red varieties. Web formation is more or less pronounced, usually occurring in the angles of leaf veins. If attack is heavy, leaves usually drop prematurely. Although spider mites seldom attack the fruit, foliage damage may result in delayed ripening, or in severe cases, fruit shriveling and dehiscence.

Effective management can often be achieved by favoring conditions that diminish vine susceptibility and enhance natural predation. Grass groundcovers, where water and fertilization are ample, diminish vine susceptibility by limiting dust production. Sprinkler irrigation discourages spider mite development, without affecting its predators. Planting vegetation that maintains high levels of spider mite predators and the avoidance of pesticides known to be toxic to their predators promote effective biological control (James and Rayner, 1995). In some instances, application of natural (e.g., Canola) oils can effectively suppress spider mite populations without damaging beneficial predatory mites (Kiss et al., 1996). In Europe, effective predator phytoseiid mites include Typhlodromus pyri and several Amblyseius spp. (Duso, 1989); in California, the primary predators are Metaseiulus occidentalis and T. caudiglans. In Australia, Typhlodromus doreenae and Amblyseius victoriensis are highly effective against the distantly related erineum (eriophytid) mites (Fig. 4.69), such as Colomerus vitis. In California, Metaseiulus occidentalis has been observed actively feeding on the same eriophytid species. For several predatory mites, sheltered habitats and pollen food sources are important in maintaining high predator populations in vineyards, whereas for M. occidentalis tydeid mites act as important alternative hosts when spider mite populations are low. The minute pirate bug (Orius vicinus) is an equally important predator (Plate 4.18), but regrettably of both spider mites and their mite predators.

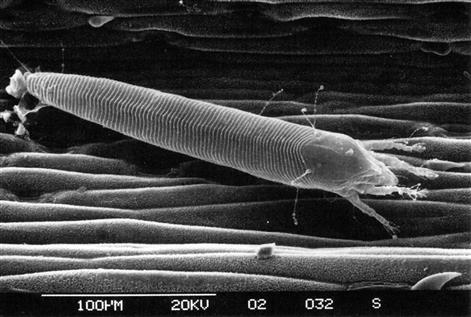

Several eriophytid mites can also induce significant damage when conditions are favorable. The most common is the rust mite (Calepitrimerus vitis) and the erineum mite (Colomerus vitis). Both are very minute (0.2 mm long and the diameter of a leaf hair), possess only two pairs of legs, and are so pale as to be hardly visible even viewed with a 10×hand lens. When abundant early in the season, and the season is cool (retarding vine growth), rust mites can cause severe leaf deformation, one of the most common examples of the syndrome termed restricted spring growth (RSG) (Bernard et al., 2005). Later in the season they can induce leaf bronzing. In contrast, the erineum mite occurs in three distinct strains, each designated by the damage it causes. The erineum strain causes gall-like deformation of the leaf, associated with excessive leaf hair growth on the undersurface of the concave puckerings. The profuse hair production accentuates the difficulty of detecting the causal agents. It is amazing how a few eriophytid mites can have such a large effect, relative to their diminutive size. The bud-mite strain limits its damage to the buds, resulting in a varied pattern of damage to leaf and shoot growth. A leaf-curling strain affects growth in the summer.

Adults tend to overwinter under the outer bud scales, or occasionally in bark crevices. Damage is often limited due to the action of the western predatory mite (Metaseiulus occidentalis). Outbreaks may result from reduced use of sulfur applied to control powdery mildew, or the application of strays that unintentionally disrupt their natural predators (Bernard et al., 2001).

Mammalian and Bird Damage

Mammals such as deer and rodents (notably gophers, voles, and rabbits) can cause considerable vine and crop damage. However, traditional control measures have become increasing complicated, due to poison and hunting restrictions. Managing bird damage can be even more intractable. Birds can cause greater economic loss than fungal diseases and grape splitting combined (Duke, 1993). Control measures include scarecrows, noise and distress-call generators, chemical repellants, and vine netting (Tracey et al., 2007). Of these, the most effective is netting. It can reduce bird damage by up to 99%. In areas where birds are a persistent pest problem, netting can be cost-effective, but coverage must be complete (Fuller-Perrine and Tobin, 1993). An electronic deterrent system (Muehleback and Bracher, 1998) employs radar to time distress calls, predator sounds, or other noises to bird arrival. The types and sequence of sounds should be varied at frequent intervals to avoid bird habituation (Berge et al., 2007). Activation of visual deterrents to bird arrival also enhances the effectiveness of devices such as flashing lights and hawk replicas. Control measures should also reflect the species involved, for example resident populations vs. migrant populations, and the type of damage caused (Bentz and Sinclair, 2005). Where feasible, encouraging predatory birds such as falcons and hawks to nest near or frequent vineyard sites can be effective, long-term deterrents (Saxton et al., 2009; Beard, 2007). Of repellant sprays, methyl anthranilate (0.75%) often remains effective for several weeks. Being nontoxic and a natural grape constituent, as well as common grape flavorant in confectionary and fruit juices (Sinclair et al., 1993), methyl anthranilate qualifies for use in organic viticulture. Although locally effective, deterrents may only move the pest problem from one vineyard to another. Long-term solutions need regional management.

Birds may become attracted to ripening grapes as their acidity levels decline, but this appears irrelevant to some species (Saxton et al., 2009). Increasing sugar level is more likely to be the significant inducement. Aromatic compounds that begin to accumulate during harvesting may also be important, for example geraniol (Saxton et al., 2004). Other aromatics, however, appear to be a deterrent, for example 2-methyl-3-isobutylpyrazine (Saxton et al., 2004). Nonetheless, the color changes associated with ripening are probably the most significant attractant, generating a bright contrast with the foliage. Birds have excellent color vision that includes an ability to see in the ultraviolet and far-red (Goldsmith, 2006).

Physiological Disorders

Grapes are susceptible to a wide range of physiological disorders, often of ill-defined etiology. This has made differentiation difficult, and has led to a profusion of expressions, whose exact equivalents are often uncertain. Nevertheless, three groups of phenomena appear to be fairly distinct. These include the death of the primary bud in compound buds (primary bud-axis necrosis); abnormal flower drop and aborted berry development shortly following fruit-set (inflorescence necrosis, shelling, early bunch-stem necrosis, coulure); and premature fruit shriveling and drop following véraison (bunch-stem necrosis, shanking, waterberry, dessèchement de la rafle, Stiellähme). A separate, somewhat similar, disorder termed berry shrivel may also exist (Krasnow et al., 2009).

Primary bud(-axis) necrosis can cause serious yield loss in several grape varieties, for example Shiraz. Rootstock, pruning method, harvesting technique, and irrigation strategy may have a significant influence on its expression (Collins and Rawnsley, 2004). In general, conditions that favor excessive shoot vigor are associated with its development. Deterioration of the primary bud becomes evident some 1–3 months after flowering, and occurs principally in basal buds. Buds may show a normal exterior or exhibit a ‘split-bud’ appearance (sunken center). Assessment of its relevance to the subsequent year’s crop requires a random selection of buds from the vineyard and their dissection. Although degeneration of the primary bud activates secondary bud development, they are rarely as fruitful.

Inflorescence necrosis (and/or coulure) refers to a series of problems resulting in flowers failing to initiate fruit development, or terminating morphogenesis as green ovaries (about 2–4 mm). An index (CI) designed to aid quantifying and studying coulure has been proposed by Collins and Dry (2009).

Coulure is associated with a wide range of conditions, such as cold wet weather during flowering and high vine vigor. It, or related phenomena, also appears to be correlated with slow berry growth rate (Intrigliolo and Lakso, 2009). Affected flowers and rachis show increasing necrosis associated with fruit abscission, usually at the base of the pedicel. Ammonia and ethylene accumulation have been implicated in inducting the disorder (Gu et al., 1991; Bessis and Fournioux, 1992). Keller and Koblet (1995) have linked both inflorescence and basal-stem necrosis (see below) with stress induced by poor light conditions, and associated carbohydrate starvation. Nitrogen deficiency has also been correlated with the phenomenon (Plate 4.19). Flower abscission has also been connected with a lack of carbohydrate reserves in buds in sensitive cultivars, such as Gewürztraminer (Lebon et al., 2004), especially when meiosis is occurring. Because abscisic acid induces abscission, Bessis et al. (2000) have suggested the application of abscisic acid inhibitors as a means of limiting coulure incidence.

‘Shot’ berries, where the fruit remain attached but fail to enlarge due to failure of ovule fertilization, is a distinct or variant disorder. It can be a symptom of zine and boron deficiency, as well as infection by fanleaf virus.

The association of NH4+ with both inflorescence necrosis and primary bud necrosis may result from protein degradation induced by carbon starvation. The resultant ammonia accumulation could damage developing apical cells. Disrupted nitrogen metabolism may also explain the observed correlation between a related phenomenon, millerandage (Plate 3.7) (unequal berry development associated with variable numbers or absence of mature seed, commonly called ‘hen and chickens’). This phenomenon has also been correlated with sustained levels of polyamines (Broquedis et al., 1995; Colin et al., 2002), as well as heightened levels of abscisic acid. The latter may, however, be just coincidental. Spraying vines with abscisic acid can increase berry set (Quiroga et al., 2009).

Bunch-stem necrosis (BSN) is associated with vine vigor and heavy or frequent rains. It starts after the onset of ripening, as expanding, soft, water-soaked regions turn into dark, sunken, necrotic spots. These develop on the rachis, its branches, or berry pedicels, usually starting around the stomata. The fruit fail to ripen properly, develop little flavor, become flaccid, and separate from the cluster. Necrosis is associated with suppressed xylem development just distal to the peduncle branching. Varieties susceptible to bunch-stem necrosis tend to develop a xylem ‘bottleneck’ at the base of the fruit (Düring and Lang, 1993). Vessel constriction presumably restricts sap flow, disrupting fruit development and resulting in the yield losses associated with the malady. Disrupted xylem connections could also explain reduced calcium uptake – calcium translocation being predominantly in the xylem. The disorder has also been associated with magnesium or calcium deficiencies. In some cases, bunch-stem necrosis has been reduced by spraying the fruit with magnesium sulfate (occasionally combined with calcium chloride), at and after véraison (Bubl, 1987). Both calcium and especially magnesium ions activate glutamine synthetase, involved in the assimilation (and detoxification) of ammonia (Roubelakis-Angelakis and Kliewer, 1983). Bunch-stem necrosis has been associated with ammonia accumulation and high nitrogen fertilization (Christensen et al., 1991). In contrast, Capps and Wolf (2000) obtained data correlating low tissue nitrogen with bunch-stem necrosis. Holzapfel and Coombe (1998) found no connection between spraying magnesium, with or without calcium, and the incidence of bunch-stem necrosis. These conflicting results may denote that bunch-stem necrosis covers a range of distinct syndromes, each with their own complex etiology.

Air Pollution

The economic damage caused by air pollution has been little studied in grapevines. Of air pollutants, ozone and hydrogen fluoride produce the most evident and visible injury. Sulfur dioxide produces injury, but at levels much higher than those found in vineyards. Even as acid rain, sulfur dioxide did not affect grapevines to any significant degree (Weinstein, 1984).

The magnitude of damage caused by air pollution has been difficult to assess or predict, due to variability in sensitivity at various growth stages. In addition, the duration, concentration, and environmental conditions of exposure significantly influence the response. Vineyard conditions, such as overcropping and other environmental stresses, appear more significant in determining the degree of damage than pollutant concentration.

Ozone

Ozone is the most injurious of common air pollutants. Grapevines were one of the first crops in which damage was detected. Ozone normally forms when oxygen absorbs shortwave ultraviolet radiation in the upper atmosphere, or during lightning. However, most of the ozone in the lower atmosphere is generated indirectly from automobile exhaust. Nitrogen dioxide (NO2), released in vehicle emissions, is photochemically split into nitric oxide and singlet oxygen (O). The oxygen radical reacts with molecular oxygen (O2) to form ozone (O3).

Nitrogen dioxide would reform by a reversal of the reaction were it not for the associated release of hydrocarbons in engine exhaust. The hydrocarbons react with nitric oxide, forming peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN). This reaction limits the reformation of nitrogen dioxide and results in the accumulation of ozone. Ozone is the most significant air pollutant affecting grapevines in North America and severely limited grape yields in some areas. Catalytic converters, now standard on modern vehicles, have significantly reduced the incidence of ozone pollution.

Ozone primarily diffuses into grapevine leaves through the stomata. Ozone, or a by-product, reacts with membrane constituents, disrupting cell function. The palisade cells are the most sensitive, often collapsing after exposure. Their collapse and death generate small brown lesions on the upper leaf surface. These coalesce to produce the interveinal spotting called oxidant stipple. A severe reaction produces a yellowing or bronzing of the leaf, and premature leaf fall. Basal leaves, and mature portions of new leaves, are particularly susceptible to ozone injury. Damage may result in reduced yield in the current year and, by depressing inflorescence induction, in the subsequent year. The severity of damage is markedly affected by cultivar sensitivity and prevailing climatic conditions. Sensitivity to ozone damage may be reduced by maintaining relatively high nitrogen levels, avoiding water stress, planting cover crops, and spraying with antioxidants such as ethylene diurea.

One of the most significant effects of ozone damage is on the root system. Reduced photosynthetic ability and the reallocation of carbohydrate transport away from the roots to damaged shoots result in mycorrhizal starvation and fine root abortion (Anderson, 2003).

Hydrogen Fluoride

Hydrogen fluoride is an atmospheric contaminant derived from industrial emissions, such as aluminum and steel smelting, ceramic production, and the fabrication of phosphorus fertilizer. Although the leaves do not accumulate fluoride in large amounts, grapevines are still one of the more sensitive plants to this pollutant.

Symptoms begin with the development of a gray-green discoloration at the margins of younger leaves. Subsequently, the affected regions expand and turn brown, often being separated from healthy tissue by a dark-red, brown, or purple band, and a thin chlorotic transition zone. Young foliage is more severely affected than are older leaves.

Application of calcium salts may protect vines from fluoride damage. Thus, spraying vines with the fungicide Bordeaux mixture, which contains slaked lime (Ca(OH)2), can gratuitously provide protection against hydrogen fluoride injury.

Chemical Spray Phytotoxicity

Herbicide drift onto grapevines can cause a wide variety of leaf malformations and injuries, depending on the herbicide involved. Several fungicides also produce phytotoxic effects, notably Bordeaux mixture and sulfur when applied at above 30°C. In addition, some pesticides induce leaf damage under specific environmental conditions, or if applied improperly, notably endosulfan, phosalone, and propargite. Details are given in Pearson et al. (1988).

Weed Control

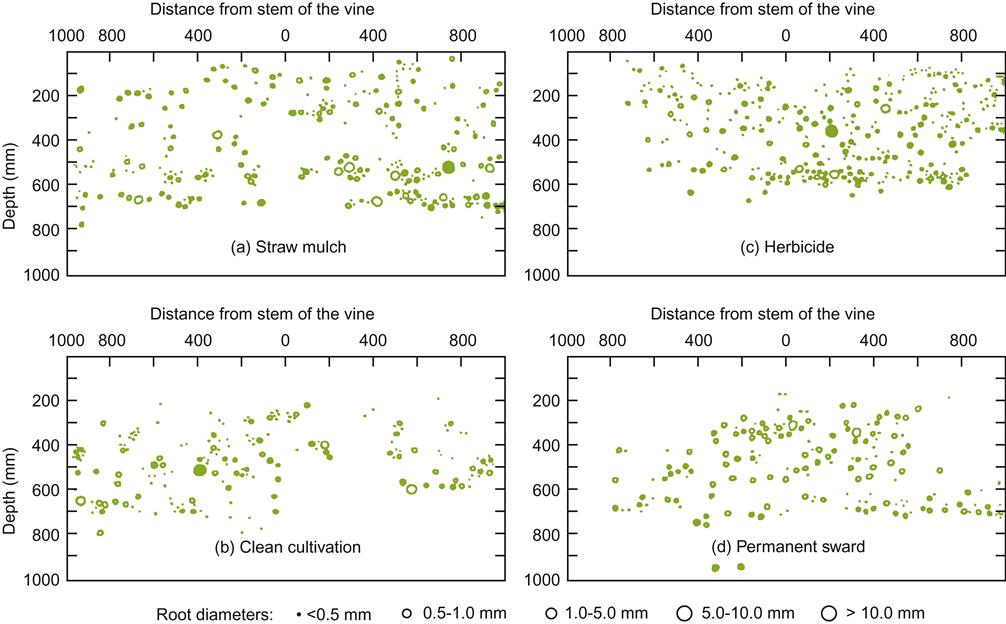

Weed control is as old as agriculture. The first significant advance over hand-pulling, the hoe, is still useful on slopes, where mechanical tillage is impractical, and in establishing a vineyard. Until comparatively recently, tillage was the principal method of weed control. Increasing energy and labor costs, combined with the availability of effective herbicides in the 1950s, reduced reliance on tillage. Modern environmental concerns have again shifted practice toward biological methods of weed control, such as mulches and groundcovers. Because each technique differentially affects relative weed-species abundance, vine root distribution (Fig. 4.70), water and nutrient supply, disease control, vine vigor, and fruit quality, and influences frost risk, irrigation, and training procedures, no system can be ideal under all situations. In addition, implementation costs, government regulations, and restrictions with regards to organic viticulture may influence grower decision. Actual need is another factor. In situations were excessive vine vigor is a concern, limiting competition from weeds may not be necessary. Nonetheless, in the latter situation use of a groundcover will provide a degree of vigor control not possible with uncontrolled weed growth.

Tillage

Tillage to a depth of 15–20 cm has been typical in weed control. Tillage can also have secondary benefits, such as breaking up compacted soil, improving fertilizer incorporation, preparing soil for sowing a cover crop, and burying diseased and infested plant remains. However, awareness of its disadvantages has combined with other factors to curtail its use. Disruption of soil aggregate structure is among its major drawbacks. This can lead to ‘puddling’ under heavy rain, and the progressive formation of a hardpan under the tilled layer; the latter results from the transport, and subsequent accumulation, of clay particles deeper in the soil. Hardpans delay water infiltration, increase soil erosion, reduce water conservation, limit root penetration and tend to restrict root development to near the soil surface. Soil cultivation progressively disrupts soil porosity (impeding water penetration and making it increasingly difficult for roots to penetrate the soil); reduces earthworm activity; and destroys aeration channels produced by cracks in the soil. The latter is most marked when the soil is cultivated when wet. In addition, by facilitating oxygen infiltration, tillage increases the rate of soil microbial action. This favors humus mineralization, reduces crumb structure, and favors soil nutrient loss. Finally, soil compaction by heavy equipment can limit root growth between rows in shallow soils (van Huyssteen, 1988b).

Herbicides

No-till cultivation, permitted with herbicide use, has become and remains popular due to its economic benefits (Tourte et al., 2008) and avoidance of the disadvantages of tillage.

Herbicides generally are categorized as pre- and post-emergent. Pre-emergent herbicides, such as simazine, kill seedlings upon germination, but do not affect existing weeds. They are typically nonselective and chiefly useful in controlling annual weeds. Herbicides such as diquat and paraquat destroy plant vegetation on contact, whereas those such as aminotriazole and glyphosate begin their destructive action after being translocated throughout the plant. To limit vine damage, herbicides are usually applied before budbreak and with special rigs designed to direct application to the base of vines. In addition, the use of controlled droplet applicator spray heads has become common. They can markedly reduce the amount of chemical needed by reducing runoff. Herbicide application may be limited to just under the vine, especially when drip irrigation is used. Mid-row regions are seeded to a cover crop. Nonetheless, herbicide application during the first 3 years of vineyard establishment is usually restricted to avoid possible vine damage. In addition, herbicide use is usually restricted to mid- to high-trained vines.

Although some herbicides, such as paraquat, decompose slowly in soil, most degrade comparatively quickly (Colquhoun, 2006). Their persistence in soil and infiltration into groundwaters depend principally on climatic and soil conditions, notably the amount and intensity of rainfall, soil temperature (affecting the rate of abiotic and microbial degradation), as well as soil structure, texture, and organic content. Nevertheless, concern about environmental pollution is increasing opposition to herbicide use; for example, an increase in the incidence of some pest problems, such as the omnivorous leafroller, has been attributed to reliance on herbicide use (Flaherty et al., 1982). In addition, some herbicides reduce the population of desirable biological control agents, such as predatory mites (Jörger, 1990). Finally, the activity of a wide range of microbes and soil invertebrates (notably earthworms) decreases in association with herbicide use (Encheva and Rankov, 1990; el Fantroussi et al., 1999; Weckert et al., 2005). The reduction in the soil flora and fauna is viewed as negative, despite our inability to accurately measure their effect (Kirk et al., 2004). It is estimated that only about 1% of the soil’s bacterial population and much of its fungal flora cannot be cultured, and thus accurately enumerated, or their actual importance studied or confirmed (Rappé and Giovannoni, 2003). Thus, the actual extent of herbicide influence on the soil’s biological population remains largely speculation. Most of the observed reduction in soil flora and fauna associated with herbicide use probably results as an indirect effect of reducing the soil’s organic content, the consequence of clean cultivation. Weeds and/or cover crops add organic content that sustains the soil’s fauna and flora. Nonetheless, direct effects of herbicides on these organisms are indisputable.

Another feature influencing herbicide use is the development of resistance. Weed resistance is a regrettable and almost inevitable outcome of overreliance on single products. As with fungicides, it is preferable to vary the product used. This limits the selective pressure generated by the sole use of a particular herbicide.

Mulches

Straw mulches have long been used in weed control and water conservation (Walpole et al., 1993). Alternative materials have included bark compost, leaf and twig compost, and sewage sludge. Solid waste from municipal compost is usually avoided, due to potential contamination with heavy metals (Pinamonti, 1998). Despite their benefits, organic mulches have seen limited use in viticulture.

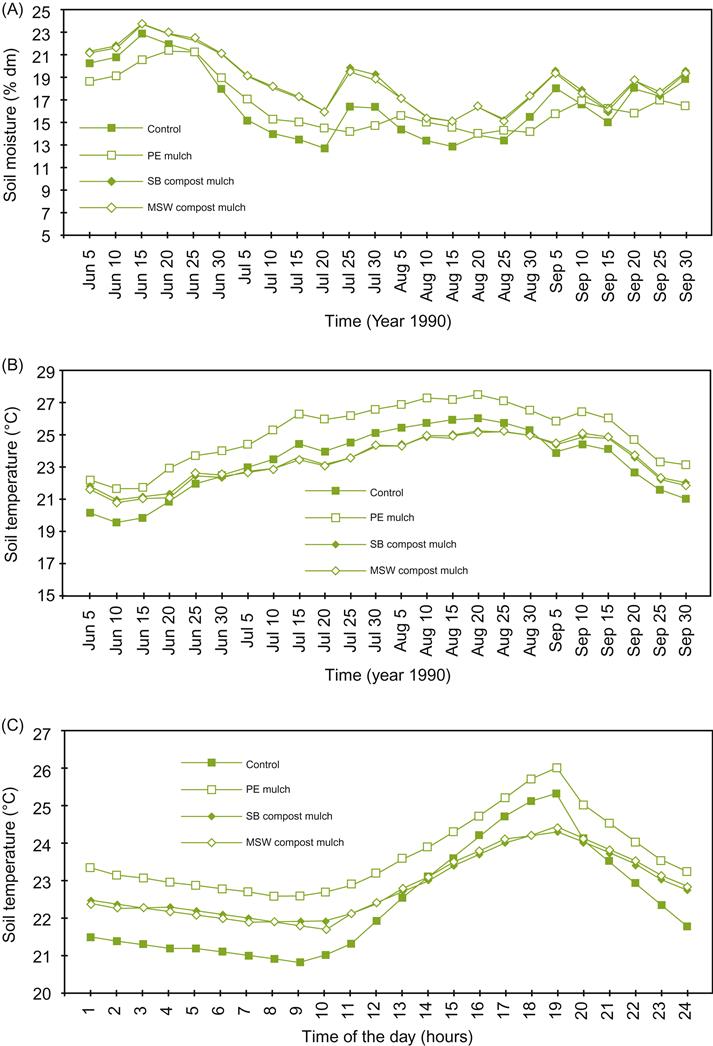

Potential advantages include cooler soil-surface temperatures and reduced fluctuation (Fig. 4.71); enhanced root activity in the upper soil horizon; reduced likelihood of erosion (Goulet et al., 2004); increased invertebrate and microbial activity (improving soil structure); reduced salt-encrustation, by diminishing upward water flow and surface evaporation; and moderation of some pathogen problems (Hoitink et al., 2002). Mulches can also facilitate vine establishment by promoting root development (Mundy and Agnew, 2004), enhance yield (especially in low-rainfall regions), and reduce irrigation water use in dry climates (Buckerfield and Webester, 1999a).

Disadvantages with organic mulch use include their being a potential overwintering site for pests and pathogens (in the case of Botrytis cinerea this may be countered by applying the biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum); slower initiation of vine growth in the spring (due to cool moist soils); enhanced risk of frost damage (reduced heat absorption by soil during the day and retarded release at night); acting as a site for rodent nests; and aggravating poor soil-drainage problems. The latter may be offset by planting vines on raised mounds (see Cass et al., 2004).

In contrast, geotextile mulches have had more success in penetrating viticultural practice, probably due to lower cost and easier and more consistent access. Unlike organic mulches, which are more often used only under the vines, geotextile mulches are more often used in lieu of a groundcover between rows. Geotextiles may be composed of a variety of materials, both natural (straw, jute, wood fibers) and woven man-made (polyethylene) fibers. Polyethylene fibers or sheets can also be engineered to be wavelength-selective. Thus, they can be designed to exclude photosynthetically active radiation (retarding weed growth) but allow penetration of far-red radiation (permitting soil warming). As such, plastic mulches have proven particularly useful in establishing vineyards, where they maintain higher moisture levels near the soil surface, promoting faster root development. Enhancing surface rooting does not impede deep root development (van der Westhuizen, 1980). Plastic mulches also enhance vine vigor and fruit yield and eliminate the potential damage caused by hoeing or herbicide application around young vines (Stevenson et al., 1986).

Plastic mulches may consist of either impermeable or porous woven sheets. Porous sheeting has the advantage of improved air and water permeability, but increases evaporative water loss. Black plastic has been the form most commonly used, but white plastic may provide better heat and photosynthetic light reflection up into the canopy (Hostetler et al., 2007). In most instances, this effect appears not to have had a significant influence on fruit ripening or quality. In contrast, the reported effects of a surface-reflective, natural-stone layer on vineyard microclimate and grape ripening can apparently be reproduced by applying a gravel mulch (Nachtergaele et al., 1998). Jute matting has the advantage of biodegradeability, but its application difficulties and cost do not recommend its use.

The cost/benefit ratio of mulch use will vary considerably from site to site (climate, need for water preservation, availability, costs of alternative weed control measures, etc.). Small trials over several years are required to establish its relative and on-site benefits/disadvantages.

Cover Crops

Planting cover crops is another, but more ecologically complex, weed control method. It may variously complement and complicate disease and pest control. It can both provide food and shelter for pest parasites and predators, as well as the pathogens or pests themselves. Thus, choosing an appropriate groundcover depends on disease conditions, as well as climate and other issues.

Depending on the purpose (see the section above on 'Green Manures'), cover crops may form a complete undercover or, more commonly, be restricted to between-row strips (Smith et al., 2008). A strip about 0.5–1 m wide under the vines is kept weed-free with herbicides, mulch, or cultivation. This is to limit immediate competition for water, nutrients, and light. Cover crops also reduce runoff, erosion, nutrient leaching, and soil compaction by machinery, and enhance the porosity and organic content of the soil (Goulet et al., 2004; Ingels et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2008). It is essentially the living equivalent of a mulch.

Although cover crops usually contain a particular selection of grasses and legumes, natural vegetation may be used. Where natural vegetation is used, application of a dilute herbicide solution may be necessary to restrict excessive and undesirable seasonal growth (Summers, 1985). This is particularly valuable early in the season, about a month after bloom. It has the benefit of limiting water competition during this critical period of vine and berry growth. Dilute herbicide may also be needed to restrict seed production and, thereby, limit self-seeding under the vines.

Another option is mowing or mulching the cover crop, sometimes in alternate rows, to restrict nitrogen demand and limit seed production (W. Koblet, 1992, personal communication). Mowing (slashing) is less effective in reducing water competition. Nitrogen fertilization may be necessary to compensate for competition between a perennial grass cover and the vines. This is unnecessary with most legume crops, such as Lana woollypod vetch (Vicia villosa spp. dasycarpa) (Ingels et al., 2005), or with a mix of clover (Trifolium repens) and ryegrass (Lolium perenne). In the latter instance, transfer of nitrogen from the mowed interrow cover crop was slow (Brunetto et al., 2011)

Seeding a cover crop usually occurs during the fall or winter months, depending on the periodicity of rainfall and the desirability of a winter groundcover. Cover crops usually possess a mixture of one or more grasses (rye, oats, or barley) and legumes (vetch, bur clover, or subterranean clover). Rye, for example, has the advantage of providing supplemental weed control due to its allelopathic effects. This can help reduce garden weevil populations by decreasing the taprooted weeds on which weevils overwinter (Hibbert and Horne, 2001). Rye grass may also significantly improve soil structure (due to decomposition of its extensive roots system and rhizosheath structures). This can significantly add organic matter, as well as facilitate water penetration (due to cavities generated by its decomposed root system) (Clancy, 2010). In Mediterranean climates, native perennial grasses may be of particular value. They grow primarily during the winter months, thus avoiding competition with vines when they are dormant. Interesting results have also been reported from Australia with summer-growing Atriplex semibacatta, a dense prostrate bush (Lazarou, 2010).

Although seed costs are considerably higher for native species than for common annuals, and establishment may take longer, their usual perennial nature often means that they are self-sustaining. Thus, establishment costs can be amortized over several years.

Strain selection can be as important as species selection. Water and nutrient use often vary considerably among strains. This is of particular concern on shallow soils under nonirrigated, dryland conditions (Lombard et al., 1988). Competition may be regulated either by mowing or plowing under. Alternatively, application of a throwdown herbicide, such as Roundup® or Touchdown®, usually just before vine flowering, can be effective. Where cover crops are also used to regulate vine vigor, limiting cover growth may be delayed to have the desired effect. Seeded annual cover crops usually require one mowing per year to prevent self-seeding.

In addition to weed control, groundcovers can promote the development of a desirable microbial and invertebrate population in the soil, and limit soil erosion. The latter is particularly valuable on steep slopes, but can also be useful on level ground. Vegetation breaks the force of water droplets that can destroy soil-aggregate structure. Cover crop roots and their associated mycorrhizal fungi improve soil structure by binding soil particles, thus limiting sheet erosion. In addition to limiting soil erosion, cover crops can improve water conservation by reducing water runoff. Conversely, in high rainfall areas, cover crops can increase evapotranspiration of excess rainfall.

As roots decay, water infiltration is improved and organic material is added to the soil. This is especially so for legumes, which incorporate organic nitrogen into the soil. Poorly mobile nutrients, such as potassium, are translocated down into the soil by the roots (Saayman, 1981), as well as by the burrowing action of soil invertebrates. Cover crops may also be selected to limit nutrient availability and vine vigor on nutrient-rich soils. Through either assisting or limiting vine growth, cover crops can be a means of influencing flavor development in the fruit, and consequently wine aroma (Xi et al., 2011). Furthermore, cover crops can facilitate machinery access to vineyards, notably when the soil is wet.

Groundcovers of diverse composition can provide a variety of habitats and pollen sources for parasites and predators of vineyard pests, for example ladybugs, green lacewings, spiders, and a myriad of parasitic wasps. Mowing, if done, should involve alternate rows to maintain a continuing habitat for biocontrol agents. Species heterogeneity in the groundcover can also enhance earthworm populations. In arid regions, ground vegetation can restrict dust production, and thus assist minimizing mite damage. Nonetheless, cover crops may equally be potential carriers of grapevine pest and disease-causing agents. For example, creeping red fescue is a host for the larvae of the black vine weevil; common and purple vetch is a host of root-knot and ring nematodes (Flaherty et al., 1992); grasses can support populations of sharpshooter leafhoppers; and legumes can be hosts for light-brown apple moths. In addition, dieback or mowing of the cover crop can disturb and precipitate movement of pests to vines.

Because cover crops usually suppress vine root growth near the soil surface (Fig. 4.72), the applicability of cover crops can depend on soil depth, water availability, and desired vine vigor. For example, restricting growth may be a desired consequence in deep fertile soils with abundant water, whereas it can be a disadvantage in arid or poor-nutrient soils. In the latter situation, tilling every second row, adding fertilizer such as farmyard manure, or periodic irrigation are possible solutions where a groundcover is desired. In some locations, the possibility of groundcovers increasing the likelihood of frost occurrence (by lowering the rate of heat radiation from the ground) may outweigh their advantages (Fig. 4.73). For this purpose, herbicides such as Roundup® or Stomp® may be applied along a relatively narrow strip down the length of each row, to leave the soil bare directly underneath the vines. During the growing season, however, groundcovers appear to have little significance on vineyard interrow temperatures (Lombard et al., 1988).

Biological Control

One of the newest techniques in weed control involves the use of weed pests and diseases. Although less investigated than other biocontrol strategies, biological control may become an adjunct to other techniques in weed control.

Another, rather novel, biologic approach to weed control is sheep grazing (Mulville, 2011; Plate 4.20). It has the advantages of combining limited water use, a reduced need for machine-based equipment, and improved organic soil amendment status. The method is a modern adaptation of an ancient technique formerly used in Mediterranean vineyards. For maximum benefit (during the growing season), it requires the installation of an electrified deterrent system to keep the sheep from feeding on the vines (Plate 4.21). By appropriate adjustment of the deterrent system, the sheep can also perform effecting vine suckering. One caveat is the potential for pesticide residues accumulating in the sheep, if they are milked or their meat subsequently sold for human consumption.

Harvesting

The timing of harvest is probably the single most important viticultural decision taken each season. The properties of the fruit at harvest set limits on the quality of the wine potentially produced. Many winemaking practices can ameliorate deficiencies in grape quality, but they cannot fully offset inherent flavor deficiencies. Timing is most critical when all the fruit is harvested concurrently. Selective harvesting over an extended period is only rarely economically feasible.

Where the grape grower is also the winemaker, and premium quality a priority, there is little difficulty in justifying the time and effort involved in precisely assessing fruit quality. However, when the grape grower is not the winemaker, adequate compensation for producing and harvesting of fruit at its optimal quality is required. The practice of basing grape payment simply on variety, weight, and sugar content is inadequate. Greater recognition and remuneration for practices enhancing grape quality could improve wine quality beyond its considerable, present-day standards.

Criteria for Harvest Timing

The major problem facing the grape grower in choosing the optimal harvest time is knowing how to most appropriately assess grape quality (Reynolds, 1996). Objective criteria demand chemical or physico-chemical measurements. Unfortunately, the chemical basis of wine quality is still ill-defined, and varies with cultivar and style. For example, grapes of intermediate maturity may produce fruitier, but less complex wines than fully mature grapes (Gallander, 1983). Champagne-style sparkling wines prefer grapes with muted varietal characteristics, so that processing-derived flavors will not be masked, whereas the reverse is the preferred situation with Asti-style sparkling wines. Without a precise chemical recipe for quality, suggesting criteria for choosing the harvest date is still partially a situation of ‘the blind leading the blind.’ It depends more on empirical knowledge than precise science. This may be acceptable for boutique wineries catering to a known and accepting clientele, but is unacceptable for major winery firms supplying a variable and fickle public.

Even with vast improvements in analytic procedures, no direct relationship has been established between the data generated and sensory quality. Perceived quality is based principally on a small fraction of the aromatic compounds found in grapes (and wine). Effectively, quality originates from the judicious, but still inscrutable, balance between impact and modifier compounds. This element of imprecision actually provides producers with a marketing advantage, assuring the continuing mystique of wine individuality, vintage distinction, and terroir magic. Nonetheless, researchers still seek the holy grail of quality – its definition in physico-chemical terms. This approach has led to marked improvements, supplying wine that is both affordable and of excellent quality. Superior wines have probably always existed, but too often they were born out of historical coincidence of place and time. Much of the continuing appeal of ‘prestige’ wines is maintained by those attracted by the allure of exclusivity.

Historically, harvest date depended (assuming favorable weather conditions) on visual, textural, and flavor clues, tempered and directed by the combined experience of generations of winemakers. Except for Muscat cultivars (Park et al., 1991), juice extracted from grapes in the vineyard is often relatively odorless, regardless of ripeness (Murat and Dumeau, 2005). This situation may change, however, if the grapes are crushed, pressed, and allowed to settle overnight, generating invaluable information relative to harvest date selection (Creasy, 2001). Readily detectable flavorants often appear to accumulate abruptly, and late during ripening. The late sensory detection probably results from their concentration finally rising above their detection threshold (McCarthy, 1986; Creasy, 2001). In addition, many varietal flavorants occur primarily as nonvolatile complexes, such as glycosides or S-cysteine conjugates, as with Sauvignon blanc. Thus, they remain essentially undetectable even in mature grapes. These may be released in sensory significant amounts only due to the action of enzymes activated during crushing (Iglesias et al., 1991), as a consequence of fermentation (Murat, 2005), or during aging (Strauss et al., 1987). This does not deny that for specific sites and cultivars, and with experience, a correlation between perceivable grape favor and eventual wine character cannot be developed. Centuries of anecdotal accounts support this view. Nevertheless, subjective criteria, based on personal experience, are unlikely to be sufficiently satisfactory for large-scale commercial operations, using a variety of cultivars, and originating from a diversity of sites.

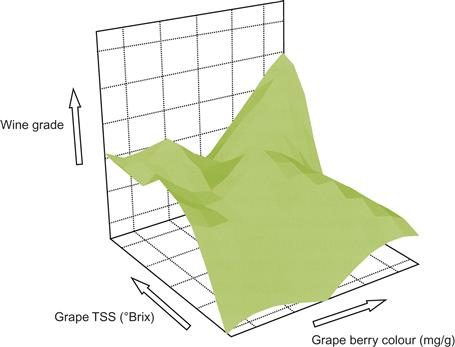

The shift from purely subjective to objective criteria by which to set harvest date began more than 100 years ago. This occurred with the development of convenient means for measuring the concentration of grape sugars and acids. They have now become the standard indicators of fruit maturity and harvest timing. Near harvest, °Brix may increase by about 2°/week (Sadras and Petrie, 2011, 2012). For red grapes, color intensity is another standard, but, until recently, difficult to quantify effectively and easily in the field. Currently, hand-held fluorescence-based optical sensors can measure fruit anthocyanin concentrations in the vineyard (Ben Ghozlen et al., 2010; Plate 4.22). In some cultivars, maturity is signaled when anthocyanin content begins to decline. Regrettably, depth of color does not necessarily directly correlate with ease of extraction (e.g., Rustioni et al., 2011), wine color, or its stability. Advances in near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) may assist by soon permitting rapid (real-time), inexpensive, and accurate winery assessment of sugar, acid, and color indicators (Cozzolino and Dambergs, 2010; Tuccio et al., 2011). Even features such as skin hardness can affect the fragility of cell walls and the ease with which important skin phenolics are released (Rolle et al., 2011b). The complexity of trying to correlate wine quality with chemical measurements is illustrated in Fig. 4.74. Grape quality is a multifactorial relationship, as is wine quality. In addition, it undoubtedly varies with the cultivar, location, and vintage. Furthermore, what is desirable for one style will almost assuredly be different for another.

The sugar/acid ratio has usually been the preferred maturity indicator in temperate climates. Desirable changes in both factors occur more or less concurrently, making the ratio a good index of grape ripeness. In many parts of the world, the sugar/acid ratio is as important as yield limitations in assessing the price given growers for their crop. In contrast, in cool climates, where insufficient sugar content is a primary concern, reaching the desired °Brix has often taken precedence as the principal harvest indicator. In hot climates, adequate levels of soluble solids are typical, but avoiding an excessive rise in pH (drop in acidity) is important. Thus, harvesting may be timed to avoid pH values greater than 3.3 for white wines, and 3.5 for red wines.

As noted, a close correlation between sugar content (soluble solids) and flavor has often been found. For example, development of varietal flavorants in Fernão-Pires accumulated exceptionally rapidly after véraison, then fell quickly (Coelho et al., 2007). Traditional harvest date, based on sugar/acid ratio, corresponded with peak flavorant concentration in terpenes, norisoprenoids, C6 aldehydes, and C6 alcohols. Despite the frequent synchrony between terpene, norisoprenoid, and anthocyanin accumulation with sugar content, it is not consistently found (Ristic et al., 2010). The association is often complex and time-dependent (Dimitriadis and Williams, 1984; Roggero et al., 1986). Marked variation in the types, concentrations, and dynamics of flavorant accumulation occurs among cultivars (Gholami et al., 1996). For example, the concentration of β-ionone increases during maturation in Pinotage, but decreases in Cabernet Sauvignon (Waldner and Marais, 2002). With Sauvignon blanc, significant accumulation of 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol precursors occurs subsequent to harvest (Capone and Jeffery, 2011). Regulating the length of time between harvesting and crushing could adjust the levels of these important flavorants (Capone et al., 2012a).

In New York, sugar and pH seem to be poor predictors of grape flavor potential (Henick-Kling, personal communication). In another cool climatic region (British Columbia), the concentration of varietal flavors, based on monoterpenes, does not readily correlate with values of soluble solids, acidity, or pH (Reynolds and Wardle, 1996). Finally, the assessed quality of Gewürztraminer wines was not correlated with the accumulation of monoterpenes in South Africa (Marais, 1996). Thus, no simple or fully adequate means of assessing grape flavor content is currently available (or may ever be). Unfortunately, there is a tendency among some winemakers to directly associate increased sugar content with more flavorful wines. However, this only assures that the wine (if fermented to dryness) will have a higher alcohol content. Although alcohol content affects the volatility of wine aromatics, whether this is desirable is highly contentious.

Because of the clear importance of anthocyanins and tannins to red wine quality, grape color is assumed to be a good indicator of grape (and subsequent wine) quality. Regrettably, there is little objective support for this belief, partially because precise measurement of color in the field was, until recently (Plate 4.22), difficult, and the correlation between total grape anthocyanin content and wine color is inconsistent. Wine color is influenced by many factors unrelated to grape anthocyanin composition (see Chapter 6 and 7). Nonetheless, Skinkis et al. (2010) found that grape color was correlated with monoterpene content in Traminette, an amber colored cultivar. In addition, Celotti and de Prati (2005) detected a strong correlation between objective color measurements of must at the winery and total grape polyphenolics. Recently, Bramley et al. (2011a) have shown success with the use of an on-the-go sensing of grape berry anthocyanin content attached to a commercial harvester. Thus, in the comparatively near future, anthocyanin content may play a more direct role in harvest decisions.

Older indicators of the potential color and flavor in red wines were based on berry size (Singleton, 1972; Somers and Pocock, 1986). This view was based on a crude, inverse relationship between berry volume and surface area, and the localization of anthocyanin pigments in the skin. Nonetheless, the correlation between phenolic and anthocyanin content, and subsequent wine quality, often appears weak (Somers and Pocock, 1986; Roggero et al., 1986; Holt et al., 2008a and b). Divergences between the results of various researchers may arise from differences in assessment technique; which phenolics were included; the proportions of various anthocyanins; measurements being based on small samples; and the influence of vinification practices on uptake, retention, and the physicochemical properties of the wine.

Another technique under investigation is grape berry texture (Rolle et al., 2011a). This involves a series of measures involving compression, puncture, and skin thickness. Initial studies have shown that with Nebbiolo there is a close inverse correlation between these measures and the relative extractability of flavanols vs. proanthocyanidins. As grapes mature, degradation of pectinaceous material in the cell walls softens the berry. Where the presence of flavonoids is important to the features desired by the winemaker, harvesting based on grape textural attributes could prove of value. The frequent tendency of grape growers to chew a selection of grapes, to assess potential harvest date, is a crude indicator of this property.

Greater success has been achieved in correlating grape flavor content with wine quality in cultivars dependent on terpenes for much of their varietal aroma. In some varieties, the volatile monoterpene content continues to increase for several weeks, after appropriate sugar and acid levels have been reached (Fig. 4.75). This may, however, also be associated with increased conversion to nonvolatile forms. Although free terpenes are important in the fragrance of some young wines, high levels of nonvolatile terpenes have been correlated with age-related flavor and quality development. The slow hydrolysis of glycosidically bound forms could release free (volatile) terpenes, sustaining or augmenting their concentration.

With several rosé wines, fruit flavor has been associated with the presence of 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol, 3-mercaptohexyl acetate, and phenethyl acetate. The first two (volatile thiols) are derived from a grape precursor (glutathionyl-3-mercaptohexan-1-ol) during fermentation. Its presence has been correlated with flavor development. Thus, precursor concentration may serve as a useful index directing viticultural practice and harvest timing (Murat and Dumeau, 2005). Regrettably, for most cultivars there are no simple, precise, accurate measures of grape varietal flavor.

Where flavor development is not concurrent with optimal sugar/acid balance, the grape grower is placed in a major dilemma. The solution requires a knowledge of the sensory significance of particular flavorants, as well as of the acceptability and applicability of sugar and acid adjustment procedures. For example, where alcohol potential is an important legal measure of quality, and chaptalization illegal, harvesting at an appropriate °Brix may be more important than grape flavor content. However, where flavor is the primary quality indicator, harvesting when flavor content is optimal, and adjusting the sugar and acid content after crushing, would be preferable, if permissible.

Another potential indicator of wine flavor, and therefore harvest timing, involves measuring the grape glycosyl-glucose (G-G) content. Because many grape flavorants are weakly bound to glucose, assessment of the G-G content (Williams, 1996; Francis et al., 1999) has been viewed as a potentially useful measure of berry flavor potential (Iland et al., 1996; Williams et al., 1996). The G-G content is more general than the volatile terpene content. It estimates not only the content of glycosidic monoterpenes, but also glycosidic norisoprenoids, as well as some volatile phenolics and aliphatic flavorants. Free and potential volatile terpene (FVT and PVT) contents are relevant only to varieties whose aroma is largely dependent on terpenes. It should be noted, however, that many grape glycosides are not associated with aromatic compounds. For example, the G-G measurement must be adjusted in red grapes to account for the glucose glycosidically bound to anthocyanins.

In warm regions, the sugar content of red grapes is closely correlated with the G-G content (Francis et al., 1998), possibly due to the close association between anthocyanin synthesis (and its glucose component) with sugar accumulation. However, even when the glucose component associated with anthocyanins was removed, the red-free G-G content showed a marked increase only during the final stages of ripening (Fig. 4.76).