1. Adamchuk VI, Lund E, Dobermann A, Morgan MT. On-the-go mapping of soil properties using ion-selective electrodes. In: Stafford J, Werner A, eds. Precision Agriculture. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Wageningen Adacemic Publishers; 2003:27–33.

2. Adamchuk VI, Hummel JW, Morgan MT, Upadhyaya SK. On-the-go soil sensors for precision agriculture. Comput Electron Agric. 2004;44:71–91.

3. Adams WE, Morris HD, Dawson RN. Effects of cropping systems and nitrogen levels on corn (Zea mays) yields in the southern Piedmont region. Agron J. 1970;62:655–659.

4. Addison P. Chemical stem barriers for the control of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in vineyards. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2002;23:1–8.

5. Agrios GN. Plant Pathology fourth ed. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1997.

6. All JN, Dutcher JD, Saunders MC, Brady UE. Prevention strategies for grape root borer (Lepidoptera, Sesiidae) infestations in Concord grape vineyards. J Econ Entomol. 1985;78:666–670.

7. Allen T, Herbst-Johnstone M, Girault M, et al. Influence of grape-harvesting steps on varietal thiol aromas in Sauvignon blanc wines. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:10641–10650.

8. Alley CJ. Grapevine propagation VII The wedge graft – a modified notch graft. Am J Enol Vitic. 1975;26:105–108.

9. Alley CJ, Koyama AT. Grapevine propagation, XVI Chip-budding and T-budding at high level. Am J Enol Vitic. 1980;31:60–63.

10. Alley CJ, Koyama AT. Grapevine propagation, XIX Comparison of inverted with standard T-budding. Am J Enol Vitic. 1981;32:20–34.

11. Alsina MM, Smart DR, Bauerle T, et al. Seasonal changes of whole root system conductance by a drought-tolerant grape root system. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:99–109.

12. Amati A, Piva A, Castellalri M, Arfelli G. Preliminary studies on the effect of Oidium tuckeri on the phenolic composition of grapes and wines. Vitis. 1996;35:149–150.

13. Amerine JA, Roessler EB. Field testing of grape maturity. Hilgardia. 1958;28:93–114.

14. Ames BN, Gold LS. Environmental pollution, pesticides, and the prevention of cancer: misconceptions. FASEB. 1997;11:1041–1052.

15. Anderson CP. Source-sink balance and carbon allocation below ground in plants exposed to ozone. New Phytol. 2003;157:213–228.

16. Angelini E, Filippin L, Michielini C, Bellotto D, Borgo M. High occurrence of Flavence dorée phytoplasma early in the season on grapevines infected with grapevine yellows. Vitis. 2006;45:151–152.

17. Anonymous. A Grower’s Guide to Choosing Rootstocks in South Australia Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia 2003.

18. Anonymous. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma’, a taxon for the wall-less, non-helical prokaryotes that colonize plant phloem and insects. Int J System Bacteriol. 2004;54:1243–1255.

19. Antolín MC, Ayari M, Sánchez-Díaz M. Effects of partial rootzone drying on yield, ripening and berry ABA in potted Tempranillo grapevines with split roots. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2006;12:13–20.

20. Araujo FJ, Williams LE. Dry matter and nitrogen partitioning and root growth of young field-grown Thompson seedless grapevines. Vitis. 1988;27:21–32.

21. Arbuckle K. The flavour is in the shade. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2011;568:20–21.

22. Archer E. Effect of plant spacing on root distribution and some qualitative parameters of vines. In: Lee T, ed. Proc 6th Aust Wine Ind Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Australian Industrial Publishers; 1987:55–58.

23. Archer E, Strauss HC. Effect of plant density on root distribution of three-year-old grafted 99 Richter grapevines. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 1985;6:25–30.

24. Archer E, Strauss HC. The effect of plant spacing on the water status of soil and grapevines. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 1989;10:49–58.

25. Archer E, van Schalkwyk D. The effect of alternative pruning methods on the viticultural and oenological performance of some wine grape varieties. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2007;28:107–139.

26. Archer, E., Swanepoel, J.J., Strauss, H.C., 1988. Effect of plant spacing and trellising systems on grapevine root distribution. In: The Grapevine Root and its Environment (J.L. van Zyl, comp.), Technical Communication No. 215, Department of Agricultural Water Supply, Pretoria, South Africa, pp. 74–87.

27. Arvanitoyannis IS, Ladas D, Mavromatis A. Wine waste treatment methodology. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2006;41:1117–1151.

28. Atallah SS, Gómez MI, Fuchs MF, Martinson TE. Economic impact of grapevine leafroll disease on Vitis vinifera cv Cabernet franc in Finger Lakes vineyards of New York. Am J Enol Vitic. 2012;63:73–79.

29. Austin CN, Grove GG, Meyers JM, Wilcox WF. Powdery mildew severity as a function of canopy density: associated impacts on sunlight penetration and spray coverage. Am J Enol Vitic. 2011;61:23–31.

30. Avisar D, Eilenberg H, Keller M, et al. The Bacillus thuringensis delta-endotoxin Cry1C as a potential bioinsecticide in plants. Plant Sci. 2009;176:315–324.

31. Aziz A, Trotel-Aziz P, Dhuicq L, Jeandet P, Couderchet M, Vernet G. Chitosan oligomers and copper sulfate induce grapevine disease reactions and resistance to grey mold and downy mildew. Phytopathology. 2006;96:1188–1194.

32. Bacon PE, Davey BG. Nutrient availability under trickle irrigation – phosphate fertilization. Fertilizer Res. 1989;19:159–167.

33. Bahlai CA, Xue Y, McCreary C, Schaafsma AW, Hallett RH. Choosing organic pesticides over synthetic pesticides may not effectively mitigate environmental risk in soybeans. Plos One. 2010;5:e11250 DOI. 10.137/journal.pone.0011250.

34. Bailey PT, Ferguson KL, McMahon R, Wicks TJ. Transmission of Botrytis cinerea by light brown apple moth larvae on grapes. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 1997;3:90–94.

35. Barata A, González S, Malfeito-Ferreira M, Querol A, Loureiro V. Sour rot-damaged grapes are sources of wine spoilage yeasts. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008;8:1008–1017.

36. Barlass M, Skene KGM. In: vitro propagation of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) from fragmented shoot apices. Vitis. 1978;17:335–340.

37. Barlass M, Skene KGM. Tissue culture and disease control. In: Lee T, ed. Proc 6th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Australian Industrial Publ.; 1987:191–193.

38. Baroffio CA, Siegfreid W, Hilber UW. Long-term monitoring for resistance of Botryotinia fuckeliana to anilinopyrimidine, phenylpyrrole, and hydroxyanilide fungicides in Switzerland. Phytopathology. 2003;87:662–666.

39. Barratt BJP, Howarth FG, Withers TM, Kean JM, Ridley GS. Progress in risk assessment for classical biological control. Bio Control. 2010;52:245–254.

40. Barron AF. Vines and Vine Culture fourth ed. London: Journal of Horticulture; 1900.

41. Barrow JR, Lucero ME, Reyes-Vera I, Havstad KM. Do symbiotic microbes have a role in plant evolution, performance and plant response to stress? Commun Integ Biol. 2008;1:69–73.

42. Basler P, Boller EF, Koblet W. Integrated viticulture in eastern Switzerland. Practic Winery Vineyard. 1991;May/June:22–25.

43. Bath GI. Vineyard mechanization. In: Stockley CS, ed. Proc 8th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1993:192.

44. Battany MC, Grismer ME. Rainfall runoff and erosion in Napa Valley vineyards: effects of slope, cover and surface roughness. Hycrol Process. 2000;14:1289–1304.

45. Bauer C, Schulz TF, Lorenz D, Eichhorn KW, Plapp R. Population dynamics of Agrobacterium vitis in two grapevine varieties during the vegetation period. Vitis. 1994;33:25–29.

46. Baumberger I. Regenwürmer – Schütenwerte Nützlinge im Boden. Weinwirtschaft Anbau. 1988;124(6):19–21.

47. Bavaresco L. Relationship between chlorosis occurrence and mineral composition of grapevine leaves and berries. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1997;28:13–21.

48. Bavaresco L, Eibach R. Investigations on the influence of N fertilizer on resistance to powdery mildew (Oidium tuckeri), downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) and on phytoalexin synthesis in different grape varieties. Vitis. 1987;26:192–200.

49. Bavaresco L, Fogher C. Lime-induced chlorosis of grapevine as affected by rootstock and root infection with arbuscular mycorrhiza and Pseudomonas fluorescens. Vitis. 1996;35:119–123.

50. Bavaresco L, Lovisolo C. Effect of grafting on grapevine chlorosis and hydraulic conductivity. Vitis. 2000;39:89–92.

51. Bavaresco L, Zamboni M, Corazzina E. Comportamento produttivo di alcune combinazioni d’innesto di Rondinella e Corvino nel Bardolino. Rev Vitic Enol. 1991;44:3–20.

52. Bavaresco L, Fregoni M, Perino A. Physiological aspects of lime-induced chlorosis in some Vitis species, II Genotype response to stress conditions. Vitis. 1995;34:232–234.

53. Beachy RN, Loesch-Fries S, Tumer NE. Coat protein-mediated resistance against virus infection. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1990;28:451–474.

54. Beard R. Harriers land a job as vineyard protectors. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2007;526:73–74.

55. Bell CR, Dickie GA, Harvey WLG, Chan JEYF. Endophytic bacteria in grapevine. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:46–53.

56. Ben Ghozlen N, Cerovic ZG, Germain C, Toutain S, Latouche G. Non-destructive optical monitoring of grape maturation by proximal sensing. Sensors. 2010;10:10040–10068.

57. Bennett J, Jarvis P, Creasy GL, Trough MC. Influence of defoliation on overwintering carbohydrate reserves, return bloom, and yield of mature Chardonnay grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 2005;56:386–393.

58. Bentz CM, Sinclair RG. Know thine enemies: using bird behaviors to determine effective management strategies. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2005;502:56–57.

59. Berge A, Delwiche M, Gorenzel WP, Salmon T. Bird control in vineyards using alarm and distress calls. Am J Enol Vitic. 2007;58:135–143.

60. Bergqvist J, Dokoozlian N, Ebisuda N. Sunlight exposure and temperature effects on berry growth and composition of Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache in the Central San Joaquin Valley of California. Am J Enol Vitic. 2001;52:1–7.

61. Berisha B, Chen YD, Zhang GY, Xu BY, Chen TA. Isolation of Pierce’s disease bacteria from grapevines in Europe. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1998;104:427–433.

62. Bernard M, Horne PA, Hoffmann AA. Preventing restricted spring growth (RSG) in grapevines by successful rust mite control – spray application, timing and eliminating sprays harmful to rust mite predators are critical. Aust N Z Grapegrower Winemaker. 2001;452(16–17):19–22.

63. Bernard MB, Horne PA, Hoffmann AA. Eriophytid mite damage in Vitis vinifera (grapevine) in Australia: Calepitrimerus vitis and Colomerus vitis (Acari: Eriophytidae) as the common cause of widespread ‘Restricted Spring Growth’ syndrome. Exp Appl Acarol. 2005;35:83–109.

64. Bernard MB, Wainer J, Carter V, Semeraro L, Yen AL, Wratten SD. Beneficial insects and spiders in vineyards: predators in South-East Australia. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2006;512:37–38 40, 42, 44–46, 48.

65. Bertran E, Sort X, Soliva M, Trillas I. Compositing winery waste: sludges and grape stalks. Biores Technol. 2004;95:203–208.

66. Beslic Z, Todic S, Tesic D. Validation of non-destructive methodology of grapevine leaf area estimation on cv Blaufränkish (Vitis vinifera L.). S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2010;31:22–25.

67. Bessis MR. Étude en microscopie electronique à balayage des rapports entre l’hôte et le parasite dans le cas de la pourriture grise. C R Acad Sci Paris, Sér D. 1972;274:2991–2994.

68. Bessis R, Fournioux JC. Zone d’abscission en coulure de la vigne. Vitis. 1992;31:9–21.

69. Bessis R, Charpentier N, Hilt C, Fournioux J-C. Grapevine fruit set: physiology of the abscission zone. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2000;6:125–130.

70. Bextine B, Lauzon C, Potter S, Lampe D, Miller TA. Delivery of a genetically marked Alcaligenes sp to the glassy-winged sharpshooter for use in a paratransgenic control strategy. Curr Microbiol. 2004;48:327–331.

71. Bindon K, Dry P, Loveys B. Influence of partial rootzone drying on the composition and accumulation of anthocyanins in grape berries (Vitis vinifera cv Cabernet Sauvignon). Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2008;14:91–104.

72. Bishop AA, Jensen ME, Hall WA. Surface irrigation systems. In: Hagan RM, ed. Irrigation of Agricultural Lands. Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy; 1967:865–884. Agronomy Monograph 11.

73. Biswas TK, McCarthy M. Subsurface drip irrigation (SDI) in wine grapes for managing salt nutrients and soil structure. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2008;537:60–63.

74. Blaich R, Stein U, Wind R. Perforation in der Cuticula von Weinbeeren als morphologischer Faktor der Botrytisresistenz. Vitis. 1984;23:242–256.

75. Blakeman JP. Behaviour of conidia on aerial plant surfaces. In: Coley-Smith JR, ed. The Biology of Botrytis. New York: Academic Press; 1980:115–151.

76. Blom PE, Tarara JM. Rapid and nondestructive estimation of leaf area on field-grown Concord (Vitis labruscana) grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 2007;58:393–397.

77. Boscia D, Greif C, Gugerli P, Martelli GP, Walter B, Gonsalves D. The nomenclature of grapevine leafroll-associated putative closterviruses. Vitis. 1995;34:171–175.

78. Boubals D. Les németodes parasites de la vigne. Prog Agric Vitic. 1954;71:141–173.

79. Boubals D. Étude de la distribution et des causes de la résistance au Phylloxera radicicole chez les Vitacées. Ann Amelior Plant. 1966;16:145–184.

80. Boubals D. Conduite pour établer une vigne dans un milieu infecté par l’anguillule ou nématode des racines (Meloidogynae sp.). Prog Agric Vitic. 1980;3:99.

81. Boubals D. Note on accidents by massive soil applications of grape byproducts. Prog Agric Vitic. 1984;101:152–155.

82. Boubals D. La maladie de Pierce arrive dans les vignobles d’Europe. Bull O.I.V. 1989;62:309–314.

83. Boulay H. Absorption différenciée des cépages et des porte-greffes en Languedoc. Prog Agric Vitic. 1982;99:431–434.

84. Bouquet A, Hevin M. Green-grafting between Muscadine grapes (Vitis rotundifolia Michx.) and bunch grapes (Euvitis spp.) as a tool for physiological and pathological investigations. Vitis. 1978;17:134–138.

85. Brady NC. The Nature and Properties of Soils eighth ed. New York: Macmillan; 1974.

86. Bramley R, Proffitt T. Managing variability in viticultural production. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999;427(11–12):15–16.

87. Bramley RGV. Understanding variability in winegrape production systems 2 Within vineyard variation in quality over several vintages. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2005;11:33–42.

88. Bramley RGV, Hamilton RP. Understanding variability in winegrape production systems 1 Within vineyard variation in yield over several vintages. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2004;10:32–45.

89. Bramley, R.G.V., Lamb, D.W., 2003. Making sense of vineyard variability in Australia. In: Ortega, R., Esser, A. (Eds.), Precision Viticulture. Proc. Int. Symp. IX Congreso Latinoamericano de Viticultura y Enologia, Santiago, Chile, pp. 35–54.

90. Bramley RGV, Le Moigne M, Evain S, et al. On-the-go sensing of grape berry anthocyanins during commercial harvest: development and prospects. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2011a;17:316–326.

91. Bramley RGV, Ouzman J, Thornton C. Selective harvesting is a feasible and profitable strategy even when grape and wine production is geared towards large fermentation volumes. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2011b;17:298–305.

92. Bramley RGV, Trought MCT, Pratt J-P. Vineyard variability in Marlborough, New Zealand: characterising variation in vineyard performance and options for the implementation of Precision Viticulture. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2011c;17:72–78.

93. Branas J. Viticulture France: J. Branas, Montpellier; 1974.

94. Brancadoro L, Rabotti G, Scienza A, Zocchi G. Mechanisms of Fe-efficiency in roots of Vitis spp in response to iron deficiency stress. Plant Soil. 1995;171:229–234.

95. Bravdo B, Hepner Y. Irrigation management and fertigation to optimize grape composition and vine performance. Acta Hortic. 1987;206:49–67.

96. Brewer MT, Milgroom MG. Phylogeography and population structure of the grape powdery mildew fungus, Erysiphe necator, from diverse Vitis species. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:268.

97. Briceño EX, Katore BA, Bordeu E. Effect of Cladosporium rot on the composition and aromatic compounds of red wine. Sp J Agric Res. 2009;7:119–128.

98. Brimmer TA, Borland GJ. A review of the non-target effects of fungi used to biologically control plant diseases. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2003;100:3–16.

99. Broderick NA, Raffa KF, Handelsman J. Midgut bacteria required for Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal activity. PNAS. 2006;103:15196–15199.

100. Broome JC, Warner KD. Agro-environmental partnerships facilitate sustainable wine-grape production and assessment. Cal Agric. 2008;62(4):133–141.

101. Broome JC, English JT, Marois JJ, Latorre BA, Aviles JC. Development of an infection model for Botrytis bunch rot of grapes based on wetness duration and temperature. Phytopathology. 1995;85:97–102.

102. Broquedis M, Lespy-Labaylette P, Bouard J. Role des polyamines dans la coulure et le millerandage. Act Colloque C.I.V.B Bordeaux 1995:23–26.

103. Brunetto G, Ventura M, Scandellari F, et al. Nutrient release during the decomposition of mowed perennial ryegrass and white clover and its contribution to nitrogen nutrition of grapevine. Nutr Cycl Agroecosys. 2011;90:299–308.

104. Bubl W. Control of stem necrosis with magnesium and micronutrient fertilizers during the period 1983 to 1985. Mitt Klosterneuburg. 1987;37:126–129.

105. Buckerfield J, Webester K. Compost as mulch for vineyards. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999a;426a(112–114):117–118.

106. Buckerfield J, Webster K. Pellets for soil improvement at planting. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999b;430:31–33.

107. Bugaret Y. L’influence des traitements anti-mildiou et de la récolte méchanique sur l’état sanitaire des bois. Phytoma. 1988;399:42–44.

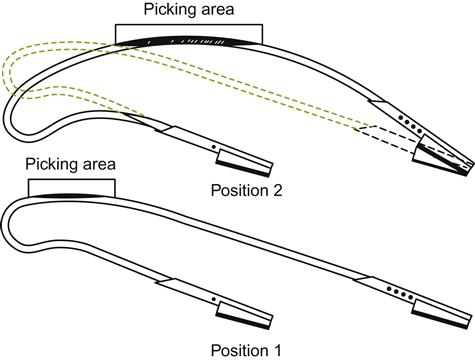

108. Burke D. Bow picking rod innovation explained. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1996;386:72–74.

109. Burr TJ, Reid CL, Yoshimura M, Monol EA, Bazzi C. Survival and tumorigenicity of Agrobacterium vitis in living and decaying grape roots and canes in soil. Plant Dis. 1995;79:677–682.

110. Burr TJ, Reid CL, Splittstoesser DF, Yoskimura M. Effect of heat treatments on grape bud mortality and survival of Agrobacterium vitis in vitro and in dormant grape cuttings. Am J Enol Vitic. 1996;47:119–123.

111. Burr TJ, Bazzi C, Süle S, Otten L. Crown gall of grape: biology of Agrobacterium vitis and the development of disease control strategies. Plant Dis. 1998;82:1288–1297.

112. Burruano S, Alfonzo A, Piccolo L, et al. Interaction between Acremonium byssoides and Plasmopara viticola. Phytopathol Medit. 2008;47:122–131.

113. Cabrera JA, Wang D, Schneider SM, Hanson BD. Effect of methyl bromide alternatives on plant parasitic nematodes and grape yield under vineyard replant conditions. Am J Enol Vitic. 2011;61:42–48.

114. Campbell JA, Strother S. Seasonal variation in pH, carbohydrate and nitrogen of xylem exudate of Vitis vinifera. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1996;23:115–118.

115. Campbell PA, Latorre BA. Suppression of grapevine powdery mildew (Uncinula necator) by acibenzolar-S-methyl. Vitis. 2004;43:209–210.

116. Canals R, Llaudy MC, Valls J, Canals JM, Zamora F. Influence of ethanol concentration on the extraction of colour and phenolic compounds from the skin and seeds of Tempranillo grapes at different stages of ripening. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:4019–4025.

117. Cançado GMA, Ribeiro AP, Piñeros MA, et al. Evaluation of aluminum tolerance in grapevine rootstocks. Vitis. 2009;48:167–173.

118. Candolfi MP, Wermelinger B, Boller EF. Influence of the European red mite (Panonychus ulmi KOCH) on yield, fruit quality and plant vigour of three Vitis vinifera varieties. Wein Wiss. 1993;48:161–164.

119. Candolfi-Vasconcelos MC, Koblet W. Yield, fruit quality, bud fertility and starch reserves of the wood as a function of leaf removal in Vitis vinifera – Evidence of compensation and stress recovering. Vitis. 1990;29:199–221.

120. Candolfi-Vasconcelos MC, Koblet W. Influence of partial defoliation on gas exchange parameters and chlorophyll content of field-grown grapevines – Mechanisms and limitations of the compensation capacity. Vitis. 1991;30:129–141.

121. Capone DL, Jeffery DW. Effects of transporting and processing Sauvignon blanc grapes on 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol precursor concentrations. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:4659–4667.

122. Capone DL, Black CA, Jeffery DW. Effects on 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol precursor concentration from prolonged storage of Sauvignon blanc grapes prior to crushing and pressing. J Agric Food Chem. 2012a;60:3515–3523.

123. Capone DL, Jeffery DW, Sefton MA. Vineyard and fermentation studies to elucidate the origin of 1,8-cineole in Australian red wine. J Agric Food Chem. 2012b;60:2281–2287.

124. Capps ER, Wolf TK. Reduction of bunch stemm necrosis of Cabernet Sauvignon by increased tissue nitrogen concentration. Am J Enol Vitic. 2000;51:319–328.

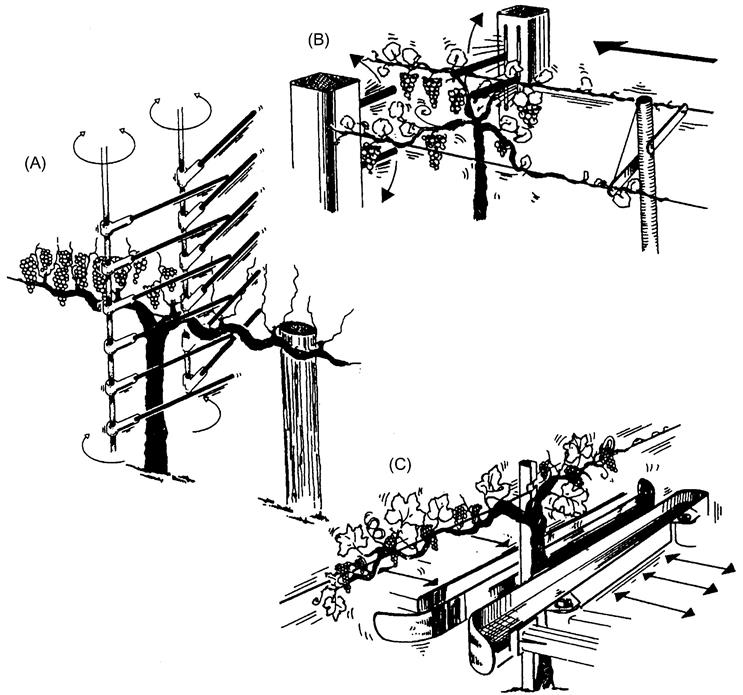

125. Carbonneau A. The lyre trellis for viticulture. Bulletin 2004:4242 <http://agspsrv34.agric.wa.gov.au/agency/pubns/bulletin/bull4242/>.

126. Carbonneau A, Casteran P. Optimization of vine performance by the lyre training systems. In: Lee T, ed. Proc 6th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Australian Industrial Publishers; 1987:194–204.

127. Carbonneau A. Trellising and canopy management for cool climate viticulture. In: Heatherbell DA, ed. Int Symp Cool Climate Vitic Enol. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University; 1985:158–183. OSU Agriculture Experimental Station Technical Publication No. 7628.

128. Cargnello G, Piccoli P. Vendemmiatrice per vigneti a pergola e a tendone. Inf Agrario. 1978;35:2813–2814.

129. Caspari HW, Neal S, Taylor A, Trought MCT. Use of cover crops and deficit irrigation to reduce vegetative vigour of ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ grapevines in a humid climate. In: Henick-Kling T, ed. Proc 4th Int Symp Cool Climate Vitic Enol. Geneva, NY: New York State Agricultural Experimental Station; 1996; pp. II-63–66.

130. Cass A, McGrath MC. Compost benefits and quality for vineyard soils. In: Christensen P, Smart D, eds. Proceeding of the Soil Environment and Vine Mineral Nutrition Symposium. Davis, CA: American Society for Enology and Viticulture; 2005:135–143.

131. Cass A, Lanyon D, Hansen D. Mounding and mulching to overcome soil restrictions. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2004;485a:27–30.

132. Caudwell A, Larrue J, Boudon-Padieu E, McLean GD. Flavescence dorée elimination from dormant wood of grapevines by hot-water treatment. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 1997;3:21–25.

133. Celotti E, de Prati CC. The phenolic quality of red grapes at delivery: objective evaluation with colour measurements. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2005;26:75–82.

134. Chacón JL, García E, Martínez J, Romero R, Gómez S. Impact of the water status on the berry and seed phenolic composition of ‘Merlot’ (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivated in a warm climate Consequences on the style of wine. Vitis. 2009;48:7–9.

135. Champagnol F. Fertilisation optimale de la vigne. Prog Agric Vitic. 1978;95:423–440.

136. Champagnol F. Elements de Physiologie de la Vigne et du Viticulture Générale Montpellier, France: F. Champagnol; 1984.

137. Champagnol F. Incidences sur la physiologie de la vigne, de la disposition du feuillage et des opérations en vert de printemps. Prog Agric Vitic. 1993;110:295–301.

138. Chapman DM, Matthews MA, Guinard J-X. Sensory attributes of Cabernet Sauvignon wines made from vines with different crop yields. Am J Enol Vitic. 2004a;55:325–334.

139. Chapman DM, Thorngate JH, Matthews MA, Guinard J-X, Ebeler SE. Yield effects on 2-methoxy-3-isobutylpyrazine concentration in Cabernet Sauvignon using a solid phase microextraction gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method. J Agric Food Chem. 2004b;52:5431–5435.

140. Chapman DM, Roby G, Ebeler SE, Guinard J-X, Matthews MA. Sensory attributes of Cabernet Sauvignon wine made from vines with different water status. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2005;11:339–347.

141. Chatterjee S, Almeida RPP, Lindow S. Living in two worlds: the plant and insect lifestyles of Xylella fastidiosa. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2008;46:234–271.

142. Chen F, Guo YB, Wang JH, Li JY, Wang HM. Biological control of grape crown gall by Rahnella awuatilis HX2. Plant Dis. 2007;91:957–963.

143. Choné X, van Leeuwen C, Chéry P, Ribéreau-Gayon P. Terroir influence on water status and nitrogen status of non- irrigated Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera) vegetative development, must and wine composition (Example of a Medoc top estate vineyard). S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2001a;22:8–15.

144. Choné X, van Leeuwen C, Dubourdieu D, Gaudillère JP. Stem water potential is a sensitive indicator of grapevine water status. Ann Bot. 2001b;87:477–483.

145. Choné X, Lavigne-Cruège V, Tominaga T, et al. Effect of vine nitrogen status on grape aromatic potential: flavor precursors (S-cysteine conjugates), glutathione and phenolic content of Vitis vinifera L cv Sauvignon blanc grape juice. J Int Sci Vigne Vin. 2006;40:1–6.

146. Christensen LP. Nutrient level comparisons of leaf petioles and blades in twenty-six grape cultivars over three years (1979 through 1981). Am J Enol Vitic. 1984;35:124–133.

147. Christensen LP, Kasimatis AN, Kissler JJ, Jensen F, Luvisi D. Mechanical Harvesting of Grapes for the Winery Agricultural Extension Publ No 2365 Berkeley, CA: University of California; 1973.

148. Christensen LP, Boggero J, Bianchi M. Comparative leaf tissue analysis of potassium deficiency and a disorder resembling potassium deficiency in Thompson seedless grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 1990;41:77–83.

149. Christensen LP, Boggero J, Adams DO. The relationship of nitrogen and other nutritional elements to the bunch stem necrosis disorder waterberry. In: Rantz JM, ed. Proc Int Symp Nitrogen Grapes Wine. Davis, CA: American Society of Enology Viticulture; 1991:108–109.

150. Christoph N, Bauer-Christoph C, Geßner M, Köhler HJ, Simat TJ, Hoenicke K. Bildung von 2-Aminoacetophenon und Formylaminoacetophenon im Wein durch Einwirkung von schwefliger Säure auf Indol-3-essigsäure. Wein-Wissenschaft. 1998;53:79–86.

151. Cifre J, Bota J, Escalona JM, Medrano H, Flexas J. Physiological tools for irrigation scheduling in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) An open gate for improving water-use efficiency? Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2005;106:159–170.

152. Clancy T. Infiltration is assisted by ryegrass root system. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2010;561:29–30.

153. Clark MF, Adams AN. Characteristics of the microplate method of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). J Gen Virol. 1977;34:475–483.

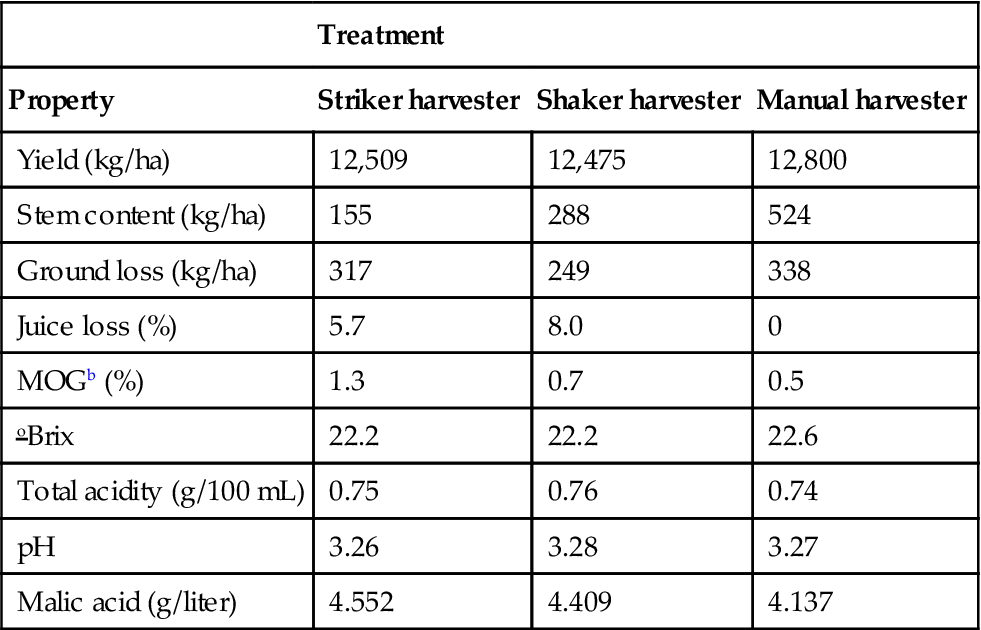

154. Clary CD, Steinhauer RE, Frisinger JE, Peffer TE. Evaluation of machine- vs hand-harvested Chardonnay. Am J Enol Vitic. 1990;41:176–181.

155. Clingeleffer PR. Production and growth of minimal pruned Sultana vines. Vitis. 1984;23:42–54.

156. Clingeleffer PR. Development of management systems for low cost, high quality wine production and vigour control in cool climate Australian vineyards. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1993;358:43–48.

157. Coelho E, Rocha SM, Barros AS, Delgadillo I, Coimbra MA. Screening of variety- and pre-fermentation-related volatile compounds during ripening of white grapes to define their evolution profile. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;597:257–264.

158. Cohen YR. β-Aminobutrytic acid-induced resistance against plant pathogens. Plant Dis. 2002;86:448–457.

159. Colin L, Cholet C, Geny L. Relationship between endogenous polyamines, cellular structure and arrested growth of grape berries. J Grape Wine Res. 2002;8:101–108.

160. Collins C, Dry P. Manipulating fruitset in grapevines. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2006;509a:38–40.

161. Collins C, Dry PR. Response of fruitset and other yield components to shoot topping and CCC application. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2009;15:256–267.

162. Collins C, Rawnsley B. National survey reveals primary bud necrosis is widespread. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2004;485a:46–49.

163. Collins M, Fuentes S, Barlow S. Water-use of grapevines to PRD irrigation at two water levels A case study in North-Eastern Victoria. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2005;502:41–45.

164. Colquhoun J. Herbicide Persistence and Carryover University of Wisconsin Extension 2006; Publ. # A3819. p. 18.

165. Comas LH, Anderson LJ, Dunst RM, Lakso AN, Eissenstat DM. Canopy and environmental control of root dynamics in a long-term study of Concord grape. New Phytol. 2005;167:829–840.

166. Comménil P, Brunet L, Audran J-C. The development of the grape berry cuticle in relation to susceptibility to bunch rot disease. J Expt Bot. 1997;48:1599–1607.

167. Compant S, Reiter B, Sessitsch A, Nowak J, Clément C, Ait Barka E. Endophytic colonization of Vitis vinifera L by plant growth-promoting bacterius Burkholderia sp strain PsJN. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1685–1693.

168. Conradie WJ. Effect of soil acidity on grapevine root growth and the role of roots as a source of nutrient reserves. The Grapevine Root and its Environment South Africa: Department of Agricultural Water Supply, Pretoria; 1988; (van Zyl, J.L., comp.), pp. 16–29. Technical Communication No. 215.

169. Conradie WJ. Partitioning of nitrogen in grapevines during autumn and the utilization of nitrogen reserves during the following growing season. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 1992;13:45–51.

170. Conradie WJ, Myburgh PA. Fertigation of Vitis vinifera L cv Bukettraube/110 Richter on a sandy soil. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2000;21:40–47.

171. Conradie WJ, Saayman D. Effects of long-term nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilization on Chenin Blanc vines I Nutrient demand and vine performance. Am J Enol Vitic. 1989;40:85–90.

172. Constable FE, Connellan J, Nicholas P, Rodoni BC. Comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for the reliable detection of Australian grapevine viruses in two climates during three growing seasons. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2012;18:239–244.

173. Cook JA. Grape nutrition. In: Childers NF, ed. Nutrition of Fruit Crops Temperate, Sub-tropical, Tropical. Somerville, NJ: Somerset Press; 1966:777–812.

174. Coombe BG. Adoption of a system for identifying grapevine growth stages. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 1995;1:100–110.

175. Coombe B, Dry P, eds. Viticulture. vol. 2. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1992.

176. Coombe BG, McCarthy MG. Identification and naming of the inception of aroma development in ripening grape berries. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 1997;3:18–20.

177. Cortell JM, Halbleib M, Gallagher AV, Righetti TJ, Kennedy JA. Influence of vine vigor on grape (Vitis vinifera L cv Pinot noir) and wine proanthocyanidins. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5798–5808.

178. Cosmo I, Comuzzi A, Polniselli M. Portinesti della Vite Bologna, Italy: Agricole; 1958.

179. Costanza P, Tisseyre B, Hunter JJ, Deloire A. Shoot development and non-destructive determination of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) leaf area. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2004;25:43–47.

180. Cozzolino D, Dambergs RG. Instrumental analysis of grape, must and wine. In: Reynolds AG, ed. Managing Wine Quality Vol. I. Viticulture and Wine Quality. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publ. Ltd.; 2010:134–161.

181. Creaser M, Wicks T, Edwards J, Pascoe I. Identification of Grapevine Trunk Diseases Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia 2002; <http://www.phylloxera.com.au/vine%20health/pdfs/Trunkdiseases.pdf>.

182. Creasy GL. Aroma evaluation of grape juices of different maturities. Aust N Z Grapegrower Winemaker. 2001;449:51–53.

183. Daane KM, Cooper ML, Triapitsyn SV, et al. Vineyard managers and researchers seek sustainable solutions for mealy bugs, a changing pest complex. Cal Agric. 2008;62(4):167–176.

184. Daane WM, Yokata GY, Rasmussen YD, Zheng Y, Hagen KS. Effectiveness of leafhopper control varies with lacewing release methods. Cal Agric. 1993;47(6):19–23.

185. Dahlin S, Kirchmann H, Katterer T, Gunnarsson S, Bergstrom L. Possibilities for improving nitrogen use from organic materials in agricultural cropping systems. Ambio. 2005;34:288–295.

186. Darriet P, Bouchilloux P, Poupot C, et al. Effects of copper fungicide spraying on volatile thiols of the varietal aroma of Sauvignon blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot wines. Vitis. 2001;40:93–99.

187. Darriet P, Pons M, Henry R, et al. Impact odorants contributing to the fungus type aroma from grape berries contaminated by powdery mildew (Uncinula necator); incidence of enzymatic activities of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:3277–3282.

188. Das DK, Nirala NK, Reddy MK, Sopory SK, Upadhyaya KC. Encapsulated somatic embryos of grape (Vitis vinifera L.): an efficient way for storage and propagation of pathogen-free plant material. Vitis. 2006;45:179–184.

189. de Bei R, Cozzolino D, Sullivan W, et al. Non-destructive measurement of grapevine water potential using near infrared spectroscopy. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2011;17:62–71.

190. De Benedictis JA, Granett J, Taormino SP. Differences in host utilization by California strains of grape phylloxera. Am J Enol Vitic. 1996;47:373–379.

191. de Klerk, C.A., and Loubser, J.V., 1988. Relationship between grapevine roots and soil-borne pests. In: The Grapevine Root and Its Environment (J. L. van Zyl, comp.), Technical Communication No. 215, pp. 88–105. Department of Agricultural Water Supply, Pretoria, South Africa.

192. De Rocher EJ, Vargo-Gogola TC, Diehn SH, Green PJ. Direct evidence for rapid degradation of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin mRNA as a cause of poor expressing in plants. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:1445–1461.

193. de Souza, C.R., Maroco, J.P., Chaves, M.M., dos Santos, T., Rodriguez, A.S., Lopes, C., et al. (2004) Effects of partial root drying on the physiology and production of grapevines composition. In: Vallone, R.C. (Ed.), Int. Symp. Irrig. Water Relat. Grapevine Fruit Trees. Acta Hortic. 646, 121–126.

194. Del Sorbo G. Fungal transporters involved in efflux of natural toxic compounds and fungicides. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;30:1–15.

195. Delp CJ. Coping with resistance to plant disease. Plant Dis. 1980;64:652–657.

196. Dhekney SA, Li ZT, Gray DJ. Grapevines engineered to express cisgeneic Vitis vinifera thaumatin-like protein exhibit fungal disease resistance In Vitro. Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2011;47:458–466.

197. Di Gaspero G, Cipriani G, Adam-Blondon A-F, Testolin R. Linkage maps of grapevine displaying the chromosomal locations of 420 microsatellite markers and 82 markers for R-gene candidates. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114:1249–1263.

198. Diago MP, Vilanova M, Blanco JA, Tardaguila J. Effects of mechanical thinning on fruit and wine composition and sensory attributes of Grenache and Tempranillo varieties (Vitis vinifera L.). J Grape Wine Res. 2010;16:314–326.

199. Díaz I, Barrón V, Del Campillo MC, Torrent J. Vivianite (ferrous sulfate) alleviates iron chlorosis in grapevine. Vitis. 2009;48:107–113.

200. Dietrich A, Wolf T, Eimert K, Schröder MB. Activation of gene expression during hypersensitive response (HR) induced by auxin in the grapevine rootstock cultivar ‘Börner’. Vitis. 2010;49:15–21.

201. Dimitriadis E, Williams PJ. The development and use of a rapid analytical technique for estimation of free and potentially volatile monoterpene flavorants of grapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 1984;35:66–71.

202. Dolci M, Galeotti F, Curir P, Schellino L, Gay G. New 2-napthyloxyacetates from trunk sucker growth control on grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2004;44:47–52.

203. Donaldson DR, Snyder RL, Elmore C, Gallagher S. Weed control influences vineyard minimum temperatures. Am J Enol Vitic. 1993;44:431–434.

204. dos Santos TP, Lopes CM, Rodrigues ML, et al. Partial rootzone drying: effects on growth and fruit quality of field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera). Funct Plant Biol. 2003;30:663–671.

205. Downton WJS. Photosynthesis in salt-stressed grapevines. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1977;4:183–192.

206. Dry IB, Feechan A, Anderson C, et al. Molecular strategies to enhance the genetic resistance of grapevines to powdery mildew. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2010;16:84–105.

207. Dry P, Loveys BR, Johnstone A, Sadler L. Grapevine response to root pruning. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1998;414a(73–74):76–78.

208. Dry PR. How to grow cool climate grapes in hot regions. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1987;283:25–26.

209. Dry PR, Loveys BR, Botting DG, Düring H. Effects of partial root-zone drying on grapevine vigour, yield, composition of fruit and use of water. In: Stockley CS, ed. Proc 9th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1996:128–131.

210. Dry PR, Loveys BR, McCarthy MG, Stoll M. Strategic irrigation management in Australian vineyards. J Int Sci Vigne Vin. 2001;35:129–139.

211. Du YP, Zhai H, Sun QH, Wang ZS. Susceptibility of Chinese grapes to grape phylloxera. Vitis. 2009;48:57–58.

212. Due G. Big growth increases with vineguards depend on soil. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999;430:34–36.

213. Duke GF. The evaluation of bird damage to grape crops in southern Victoria. In: Stockley CS, ed. Proc 8th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1993:197.

214. Düker A, Kubiak R. Stem application of metalaxyl for the protection of Vitis vinifera L (‘Riesling’) leaves and grapes against downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola). Vitis. 2009;48:43–48.

215. Dunn, G.M. (2010) Yield Forecasting. Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation, Australia. <http://www.gwrdc.com.au/webdata/resources/factSheet/GWR_066_Yield_Forecasting_Fact_Sheet_FINAL.pdf>.

216. Durán-Patrón R, Hernández-Galán R, Collado IG. Secobotrytriendiol and related sesquiterpenoids: new phytoxic metabolites from Botrytis cinerea. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:182–184.

217. Duran-Vila N, Juárez J, Arregui JM. Production of viroid-free grapevines by shoot tip culture. Am J Enol Vitic. 1988;39:217–220.

218. Düring, H. (1990) Stomatal adaptation of grapevine leaves to water stress. In Proc. 5th Int. Symp. Grape Breeding pp. 366–370. (Special Issue of Vitis) St. Martin, Pfalz, Germany.

219. Düring H, Lang A. Xylem development and function in the grape peduncle Relations to bunch stem necrosis. Vitis. 1993;32:15–22.

220. Düring H, Dry PR, Loveys BR. Root signals affect water use efficiency and shoot growth. Acta Hortic. 1996;427:1–13.

221. Duso C. Role of the predatory mites Amblyseius aberrans (Oud.) Typhlodromus pyri Scheuten and Amblyseius andersoni (Chant) (Acari, Phytoseiidae) in vineyards, I The effects of single and mixed phytoseiid population releases on spider mite densities (Acari, Tetranychidae). J Appl Entomol. 1989;107:474–492.

222. Dutt EC, Olsen MW, Stroehlein JL. Fight root rot in the border wine belt. Wines Vines. 1986;67(3):40–41.

223. Düzenli S, Ergenoğlu F. Studies on the density of stomata of some Vitis vinifera L varieties grafted on different rootstocks trained up various trellis systems. Doğa – Tr. J. Agric. For. 1991;15:308–317.

224. Eastwell KC, Sholberg PL, Sayler RJ. Characterizing potential bacterial biocontrol agents for suppression of Rhizobium vitis, causal agent of crown gall disease in grapevines. Crop Protect. 2006;25:1191–1200.

225. Edwards J, Pascoe I. Incidence of Phaeoconiella chlamydospore infection in symptomless young vines. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2003;473a:90–92.

226. Eibach R, Zyprian E, Welter L, Töpfer R. The use of molecular markers for pyramiding resistance genes in grapevine breeding. Vitis. 2007;46:120–124.

227. Eifert J, Varnai M, Szöke L. Application of the EUF procedure in grape production. Plant Soil. 1982;64:105–113.

228. Eifert J, Varnai M, Szöke L. EUF-nutrient contents required for optimal nutrition of grapes. Plant Soil. 1985;83:183–189.

229. Eisenbarth HJ. Der Einfluss unterschiedlicher Belastungen auf die Ertragsleistung der Rebe. Dtsch Weinbau. 1992;47:18–22.

230. el Fantroussi S, Verschuere L, Verstrawte W, Top EM. Effect of phenylurea hervicides on soil microbial communities estimated by analysis of 16S rRNA gene fingerprints and comunity-level physiological profiles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:982–988.

231. Elrick DE, Clothier BE. Solute transport and leaching. In: Stewart BA, Nielsen DR, eds. Irrigation of Agronomic Crops. Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America Publication; 1990:93–126. Agronomy Monograph 30.

232. Encheva K, Rankov V. Effect of prolonged usage of some herbicides in vine plantation on the biological activity of the soil (in Bulgarian). Soil Sci Agrochem (Prchvozn. Agrokhim.). 1990;25:66–73.

233. Englert WD, Maixner M. Biologische Spinnmibenbekämp-fung im Weinbau durch Schonung der Raubmilbe Typhlodromus pyri. Schonung und Förderung von Nützlingen. Schriftenr Bundesminist Ernährung, Landwirtschaft Forsten, Reihe A: Angew Wiss. 1988;365:300–306.

234. English-Loeb G, Norton AP, Gadoury DM, Seem RC, Wilcox WF. Control of powdery mildew in wild and cultivated grapes by a tydeid mite. Biol Cont. 1999;14:97–103.

235. English-Loeb G, Rhainds M, Martinson T, Ugine T. Influence of flowering cover crops on Anagrus parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Mymaridae) and Erythroneura leafhoppers (Homoptera: Cicadellidae) in New York vineyards. Agric Forest Entomol. 2003;5:173–181.

236. Erb M, Lenk C, Degenhardt J, Turlings TCJ. The underestimated role of roots in defense against leaf attackers. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:653–659.

237. Ermolaev AA. Resistance of grape to phylloxera on sandy soils (in Russian). Agrokhimiya. 1990;2:141–151.

238. Escalona J, Flexas J, Medrano H. Drought effects on water flow, photosynthesis and growth of potted grapevines. Vitis. 2002;41:57–62.

239. Evans T. Mapping vineyard salinity using electromagnetic surveys. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1998;415:20–21.

240. Ewart AJW, Walker S, Botting DG. The effect of powdery mildew on wine quality. In: Stockley CS, ed. Proc 8th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1993:201.

241. Fabbri A, Lambardi M, Sani P. Treatments with CCC and GA3 on stock plants and rootings of cuttings of the grape rootstock 140 Ruggeri. Am J Enol Vitic. 1986;37:220–223.

242. Failla O, Scienza A, Stringari G, Falcetti M. Potassium partitioning between leaves and clusters, Role of rootstock. Proc 5th Int Symp Grape Breeding Pfalz, Germany: St. Martin; 1990; pp. 187–196. (Special Issue of Vitis).

243. Falconer R, Liebich B, Hart A. Automated color sorting of hand-harvested Chardonnay. Am J Enol Vitic. 2006;57:491–496.

244. Falk SP, Gadoury DM, Pearson RC, Seem RC. Partial control of grape powdery mildew by the mycoparasite Ampelomyces quisqualis. Plant Dis. 1995;79:483–490.

245. Fardossi A, Barna J, Hepp E, Mayer C, Wendelin S. Einfluß von organischer Substanz auf die Nährstoffaufnahme durch die Weinrebe im Gefäßversuch. Mitt Klosterneuburg. 1990;40:60–67.

246. Fendinger AG, Pool RM, Dunst RM, Smith RL. Effect of mechanical thinning of minimally pruned ‘Concord’ grapevines on fruit composition. In: Henick-Kling T, ed. Proc 4th Int Symp Cool Climate Vitic Enol. Geneva, NY: New York State Agricultural Experimental Station; 1996; pp. IV-13–17.

247. Feng H, Skinkis P, Qian MC. Cover-crop management on free and bound volatiles of cv Pinot noir grapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 2011;62:405A–406A.

248. Fergusson-Kolmes L, Dennehy TJ. Anything new under the sun? Not phylloxera biotypes. Wines Vines. 1991;72(6):51–56.

249. Fernández JE, Cuevas MV. Irrigation scheduling from stem diameter variations: a Review. Agric Forest Metereol. 2010;150:135–151.

250. Fernández JE, Green SR, Caspari HW, Diaz-Espejo A, Cuevas MV. The use of sap flow measurements for scheduling irrigation in olive, apple and Asian pear trees and in grapevines. Plant Soil. 2007;305:91–104.

251. Ficke A, Gadoury DM, Seem RC, Dry IB. Effects on ontogenic resistance upon establishment and growth of Uncinula necator on grape berries. Phytopathology. 2003;93:556–563.

252. Fidelibus MW, Cathline KA, Burns JK. Potential abscission agents for raisin, table, and wine grapes. HortScience. 2007;42:1626–1630.

253. Finger SA, Wolf TK, Baudoin AB. Effects of horticultural oils on the photosynthesis, fruit maturity, and crop yield of winegrapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 2002;53:116–124.

254. Fischer BM, Salakhutdinov I, Akkurt M, et al. Quantitative trait locus analysis of fungal disease resistance factors on a molecular map of grapevine. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108:501–515.

255. Flaherty, D.L., Jensen, F.L., Kasimatis, A.N., Kido, H., and Moller, W.J. (1982) Grape Pest Management. Publication No. 4105. Cooperative Extension, University of California, Oakland, CA.

256. Flaherty DL, Christensen LP, Lanini WT, Marois JJ, Phillips PA, Wilson LT. Grape Pest Management second ed. Oakland, CA: Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California; 1992; Publication No. 3343.

257. Flexas J, Escalona JM, Medrano H. Water stress induces different levels of photosynthesis and electron transport rate regulation in grapevines. Plant Cell Environ. 1999;22:39–48.

258. Flexas J, Bota J, Escalona JM, Sampol B, Medrano H. Effects of drought on photosynthesis in grapevines under field conditions: an evaluation of stomatal and mesophyll limitations. Funct Plant Biol. 2002;29:461–471.

259. Foott JH. A comparison of three methods of pruning Gewürztraminer. Cal Agric. 1987;41(1):9–12.

260. Foott JH, Ough CS, Wolpert JA. Rootstock effects on wine grapes. Cal Agric. 1989;43(4):27–29.

261. Forde CG, Cox A, Williams ER, Boss PK. Associations between the sensory attributes and volatile composition of Cabernet Sauvignon wines and the volatile composition of the grapes used for their production. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:2573–2583.

262. Forneck A, Huber L. (A)sexual reproduction – a review of life cycles of grape phylloxera, Daktulosphaeria vitifoliae. Emtomol Exp Appl. 2009;131:1–10.

263. Forneck A, Walker MA, Blaich R. Genetic structure of an introduced pest, grape phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae Fitch), in Europe. Genome. 2000;43:669–678.

264. Forneck A, Kleinmann S, Blaich R, Anvari SF. Histochemistry and anatomy of phylloxera (Daktulospaira vitifoliae) nodosities on young roots of grapevine (Vitis spp.). Vitis. 2002;41:93–98.

265. Fourie PH, Halleen F. Proactive control of Petri disease of grapevine through treatment of propagation material. Plant Dis. 2004;88:1241–1245.

266. Fourie PH, Halleen F. Chemical and biological protection of grapevine propagation material from trunk disease pathogens. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2006;116:255–265.

267. Fournier E, Giraud T, Albertini C, Brygoo Y. Partition of the Botrytis cinerea complex in France using multiple gene genealogies. Mycologia. 2005;97:1251–1267.

268. Fournioux JC. Influences foliaires sur le développement végétativ de la vigne. J Int Sci Vigne Vin. 1997;31:165–183.

269. Francis IL, Kassara S, Noble AC, Williams PJ. The contribution of glycoside precursors to Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot aroma: sensory and compositional studies. In: Waterhouse AL, Ebeler SE, eds. Chemistry of Wine Flavour. Washington, DC: Amer. Chem. Soc.; 1999:13–30.

270. Francis L, Armstrong H, Cynkar W, Kwiatkowski M, Iland P, Williams P. A national vineyard fruit composition survey – evaluating the G-G assay. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1998;414a(51–53):55–58.

271. Freese P. Here’s a close look at vine spacing. Wines Vines. 1986;67(4):28–30.

272. Fregoni M. Exigences d’éléments nutritifs en viticulture. Bull O.I.V. 1985;58:416–434.

273. Friend AP, Trought MCT. Delayed winter spur-pruning in New Zealand can alter yield components of Merlot grapevines. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2007;13:157–164.

274. Frost B. Eriophytid mites and grape production in Australian vineyards. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1996;393(25–27):29.

275. Fuentes S, Camus C, Rogers G, Conroy J. Precision irrigation in grapevines under RDI and PRD Wetting Pattern Analysis (WPA©), a novel software tool to visualise real time soil wetting patterns. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2004a;485a(120–122):125.

276. Fuentes S, Conroy J, Collins M, Kelley G, Mora R. A soil-plant-atmosphere approach to evaluate PRD on grapevines (Vitis vinifera L var Shiraz). Aust N Z Grapegrower Winemaker. 2004b;490:54–58.

277. Fuller-Perrine LD, Tobin ME. A method for applying and removing bird-exclusion netting in commercial vineyards. Wildlife Soc Bull. 1993;21:47–51.

278. Furkaliev DG. Hybrids between Vitis species – The development of modern rootstocks. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999;426a(18–22):24–25.

279. Furness G. A new fan for multi-head, air-assisted sprayers offers major improvement in disease and pest management. Aust N Z Grapegrower Winemaker. 2002;463 35–36, 38, 40, 42–43.

280. Furness G. Setting pesticide dose using spray volume calculation. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2009;547:32–35.

281. Gadoury DM, Pearson RC, Riegel DG, Seem RC, Becker CM, Pscheidt JW. Reduction of powdery mildew and other diseases by over-the-trellis applications of lime sulfur to dormant grapevines. Plant Dis. 1994;78:83–87.

282. Gadoury DM, Seem RC, Ficke A, Wilcox WF. Ontogenic resistance to powdery mildew in grape berries. Phytopathology. 2003;93:547–555.

283. Gadoury DM, Seem RC, Wilcox WF, et al. Effect of diffuse colonization of grape berries by Uncinula necator and bunch rots, berry microflora, and juice and wine quality. Phytopathology. 2007;97:1356–1365.

284. Galet P. Précis d’Ampélographie Dehan, Montpellier 1971.

285. Galet P. A Practical Ampelography – Grapevine Identification Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1979; (L. T. Morton, trans.).

286. Galet P. Précis de Pathologie Viticole France: Dehan, Montpellier; 1991.

287. Gallander JF. Effect of grape maturity on the composition and quality of Ohio Vidal Blanc wines. Am J Enol Vitic. 1983;34:139–141.

288. Gargiulo AA. Woody T-budding of grapevines – Storage of bud shields instead of cuttings. Am J Enol Vitic. 1983;34:95–97.

289. Geraudie V, Roger JM, Ojeda H. Development of a tool allowing the prediction of grape maturity using near-infrared spectroscopy. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2010;557a(10):12–16.

290. Gholami M, Coombe BG, Robinson SP, Williams PJ. Amounts of glycosides in grapevine organs during berry development. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 1996;2:59–63.

291. Girbau T, Stummer BE, Pocock KF, Baldock GA, Scott ES, Waters EJ. The effect of Uncinula necator (powdery mildew) and Botrytis cinerea infection of grapes on the levels of haze-forming pathogenesis-related proteins in grape juice and wine. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2004;10:125–133.

292. Gishen M, Dambergs B. Some preliminary trials in the application of scanning near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for determining the compositional quality of grape wine and spirits. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1998;414a 43–45, 47.

293. Gishen M, Iland PG, Dambergs RG, et al. Objective measures of grape and wine quality. In: Blair RJ, Williams PJ, Høj PB, eds. 11th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf Oct 7–11, 2001, Adelaide, South Australia. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 2002:188–194.

294. Gladstone EA, Dokoozlian NK. Influence of leaf area density and trellis/training system on the light microclimate within grapevine canopies. Vitis. 2003;42:123–131.

295. Glazebrook J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2005;43:205–227.

296. Glidewell SM, Williamson B, Goodman BA, Chudek JA, Hunter G. A NMR microscopic study of grape (Vitis vinifera). Protoplasma. 1997;198:27–35.

297. Gobbin D, Jermini M, Loskill B, Pertot I, Raynal M, Gessler C. Importance of secondary inoculum of Plasmopara viticola to epidemics of grapevine downy mildew. Plant Pathol. 2005;54:522–534.

298. Gökbayrak Z, Söylemezoğlu G, Akkurt M, Çelik H. Determination of grafting compatibility of grapevine with electrophoretic methods. Sci Hortic. 2007;113:343–352.

299. Gold LS, Slone TH, Stern BR, Manley NB, Ames BN. Rodent carcinogens: setting priorities. Science. 1992;258:261–265.

300. Goldhamer DA, Fereres E. Irrigation scheduling protocols using continuously recorded trunk diameter measurements. Irrig Sci. 2001;20:115–125.

301. Goldsmith TH. What birds see. Sci Am. 2006;295(1):68–75.

302. Goldspink BH, Pierce CA. Post-harvest nitrogen applications, are they beneficial? In: Stockley CS, ed. Proc 8th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1993:202.

303. Golino DA. Potential interactions between rootstocks and grapevine latent viruses. Am J Enol Vitic. 1993;44:148–152.

304. Gong H, Blackmore DH, Walker RR. Organic and inorganic anions in Shiraz and Chardonnay grape berries and wine as affected by rootstock under saline conditions. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2010;16:227–236.

305. Goulet E, Dousset S, Chaussod R, Bartoli F, Doledec AF, Andreux F. Water-stable aggregates and organic matter pools in a calcareous vineyard soil under four soil-surface management systems. Soil Use Manage. 2004;20:318–324.

306. Graham AB. Integration of hot water treatment with biocontrol treatments improves yield and sustainability in the nursery. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2007;524 33–36, 38.

307. Granett J, Goheen AC, Lider LA, White JJ. Evaluation of grape rootstocks for resistance to Type A and Type B grape phylloxera. Am J Enol Vitic. 1987;38:298–300.

308. Granett J, Walker A, de Benedictis J, Fong G, Lin H, Weber E. California grape phylloxera more variable than expected. Cal Agric. 1996;50(4):9–13.

309. Granett J, Omer AD, Pessereau P, Walker MA. Fungal infections of grapevine roots in phylloxera-infested vineyards. Vitis. 1998;37:39–42.

310. Greer DH, Rogers SY, Steel CC. Susceptibility of Chardonnay grapes to sunburn. Vitis. 2006;45:147–148.

311. Grenan S. Multiplication In vitro et caractéristiques juvéniles de la vigne. Bull O.I.V. 1994;67:5–14.

312. Gu S, Lombard PB, Price SF. Inflorescence necrosis induced by ammonium incubation in clusters of Pinot noir grapes. In: Rantz JM, ed. Proc Int Symp Nitrogen Grapes and Wine. Davis, CA: American Society of Enology Viticulture; 1991:259–261.

313. Gubler WD, Ypema HL. Occurrence of resistance in Uncinula necator to triadimefon, myclobutanil, and fenarimol in California grapevines. Plant Dis. 1996;80:902–909.

314. Guennelon, R., Habib, R., and Cockborn, A.M. (1979) Aspects particuliers concernant la disponibilité de N, P et K en irrigation localisée fertilisante sur arbres fruitiers. In Séminaires sur l’Irrigation Localisée I, pp. 21–34. L’Institut d’Agronomie de l’Université de Bologne, Italy.

315. Guerra B, Meredith CP. Comparison of Vitis berlandieri×Vitis riparia rootstock cultivars by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Vitis. 1995;34:109–112.

316. Guisard Y, Birch CJ, Tesic D. Predicting the leaf area of Vitis vinifera L cvs Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz. Am J Enol Vitic. 2010;61:272–277.

317. Gurr SJ, Rushton PJ. Engineering plants with increased disease resistance: what are we going to express? Trends Biotechnol. 2005a;23:275–282.

318. Gurr SJ, Rushton PJ. Engineering plants with increased disease resistance: how are we going to express it? Trends Biotechnol. 2005b;23:283–290.

319. Hagan, R.M. (1955) Factors affecting soil moisture-plant growth relations. In: Report 14th Int. Hortic. Cong. The Hague, The Netherlands, pp. 82–102.

320. Hajrasuliha S, Rolston DE, Louie DT. Fate of 15N fertilizer applied to trickle-irrigated grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 1998;49:191–198.

321. Hall A, Lamb DW, Holzapfel B, Louis J. Optically remote sensing applications in viticulture – a review. J Grape Wine Res. 2002;8:36–47.

322. Halleen F, Holz G. An overview of the biology, epidemiology and control of Uncinula necator (powdery mildew) on grapevine with reference to South Africa. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2001;22:111–121.

323. Halleen F, Crous PW, Petrini O. Fungi associated with healthy grapevine cuttings in nurseries, with special reference to pathogens involved in the decline of young vines. Australasian Pl Pathol. 2003;32:47–52.

324. Hamilton R. Hot water treatment of grapevine propagation material. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1997;400:21–22.

325. Hamilton RP, Coombe BG. Harvesting of winegrapes. In: Coombe BG, Dry PR, eds. Viticulture, Vol 2, (Practices). Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1992:302–327.

326. Hanson B, Peters D, Orloff S. Effectiveness of tensiometers and electrical resistance sensors varies with soil conditions. Calif Agric. 2000;54:47–50.

327. Hanson BR, Bendixen WE. Drip irrigation controls soil salinity under row crops. Calif Agric. 1995;49:19–24.

328. Hanson BR, Dickey GL. Field practices affect neutron moisture meter accuracy. Calif Agric. 1993;47(6):29–31.

329. Hardie WJ, Martin SR. A strategy for vine growth regulation by soil water management. In: Williams PJ, ed. Proc 7th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1990:51–57.

330. Harm A, Kassemeyer H-H, Seibicke T, Regner F. Evaluation of chemical and natural resistance inducers against downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) in grapevine. Am J Enol Vitic. 2011;62:184–192.

331. Harris JM, Kriedemann PE, Possingham JV. Anatomical aspects of grape berry development. Vitis. 1968;7:106–119.

332. Hashem M, Omranm YAMM, Sallam NMA. Efficacy of yeasts in the management of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita, in Flame Seedless grapevines and the consequent effect on the productivity of the vines. Biocont Sci Technol. 2008;18:357–375.

333. Hatch TA, Hickey CC, Wolf TK. Cover crop, rootstock, and root restriction regulate vegetative growth of Cabernet Sauvignon in a humid environment. Am J Enol Vitic. 2011;62:298–311.

334. Hatzidimitriou E, Bouchilloux P, Darriet P, et al. Incidence d’une protection viticole anticryptpgamique utilisant une formulation cuprique sur le niveau de maturité des raisins et l’arôme variétal des vins de Sauvignon Bilan de trois années d’expérimentation. J Intl Sci Vigne Vin. 1996;30:133–150.

335. Haynes RJ, Naidu R. Influence of lime, fertilizer and manure applications on soil organic matter content and soil physical conditions: a review. Nutr Cycl Agrosyst. 1998;51:123–137.

336. Hendson M, Purcell AH, Chen D, Smart C, Guilhabert M, Kirkpatrick B. Genetic diversity of Pierce’s disease strains and other pathotypes of Xylella fastidiosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:895–903.

337. Henick-Kling, T. (1995). Summary of effects of organic and conventional grape production practices on juice and wine composition. Special report, New York Agricultural Experiment Station, Geneva. 69, 67–75.

338. Hibbert D, Horne P. IPM: how inter-row cover crops can encourage insect population in vineyards. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2001;452:76.

339. Hill BL, Purcell AH. Multiplication and movement of Xylella fastidiosa within grapevine and four other plants. Phytopathology. 1995;85:1368–1372.

340. Hill, G.K. 1988. Organic viticulture in Germany – practical experiences and organization. Smart. In: Smart, R.E. et al., (Eds.), Proc. 2nd Int. Symp Cool Climate Vitic. Oenol., Jan. 11–15, 1988, Auckland, NZ, NZ Soc. Vitic. Oenol.

341. Hill, G.K., Kassemeyer, H.-H. (Organizers) 1997. Proc 2nd Int. Workshop Grapevine Downy Powdery Mildew Modeling Wein Wiss. 3–4, 115–231.

342. Hoffman LE, Wilcox WF. Using epidemiological investigations to optimize management of grape black rot. Phytopathology. 2002;92:676–680.

343. Hoffman LE, Wilcox WF, Gadoury DM, Seem RC, Riegel DG. Integrated control of grape black rot: influence of host phenology, inoculum availability, sanitation, and spray timing. Phytopathology. 2004;94:641–650.

344. Hofstein R, Daoust RA, Aeschlimann JP. Constraints to the development of biofungicides: the example AQ10, a new product for controlling powdery mildews. Entomophaga. 1996;41:455–460.

345. Hoitink HAJ, Wang P, Changa CM. Role of organic matter in plant health and soil quality. In: Blair RJ, Williams PJ, Høj PB, eds. 11th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf Oct 7–11, 2001, Adelaide, South Australia. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 2002:57–60.

346. Holt HE, Francis IL, Field J, Herderich MJ, Iland PG. Relationships between wine phenolic composition and wine sensory properties for Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera L.). Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2008a;15:162–176.

347. Holt HE, Francis IL, Field J, Herderich MJ, Iland PG. Relationships between berry size, berry phenolic composition and wine quality scores for Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera L.) from different pruning treatments and different vintages. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2008b;15:191–202.

348. Holzapfel BP, Coombe BG. Interaction of perfused chemicals as inducers and reducers of bunchstem necrosis in grapevine bunches and the effects on the bunchstem concentrations of ammonium ion and abscisic acid. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 1998;4:59–66.

349. Holzapfel BP, Rogiers S, Degaris K, Small G. Ripening grapes to specification: effect of yield on colour development of Shiraz grapes in the Riverina. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999;428(24):26–28.

350. Holzapfel BP, Smith JP, Mandel RM, Keller M. Manipulating the postharvest period and its impact on vine productivity of Semillon grapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 2006;57:148–157.

351. Hopkins DL, Purcell AH. Xylella fastidiosa: cause of Pierce’s disease of grapevine and other emergent diseases. Plant Dis. 2002;86:1056–1066.

352. Hostetler GL, Merwin IA, Brown MG, Padilla-Zakour O. Influence of geotextile mulches on canopy microclimate, yield, and fruit composition of Cabernet franc. Am J Enol Vitic. 2007;58:431–442.

353. Howell GS. Vitis rootstocks. In: Rom RC, Carlson RF, eds. Rootstocks for Fruit Crops. New York, NY: John Wiley; 1987:451–472.

354. Howell GS. Sustainable grape productivity and the growth-yield relationship: a review. Am J Enol Vitic. 2001;52:165–174.

355. Howell GS, Miller DP, Edson CE, Striegler RK. Influence of training system and pruning severity on yield, vine size, and fruit composition of Vignoles grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 1991;42:191–198.

356. Howell GS, Candolfi-Vasconcelos MC, Koblet W. Response of Pinot noir grapevine growth, yield, and fruit composition to defoliation the previous growing season. Am J Enol Vitic. 1994;45:188–191.

357. Huang Z, Ough CS. Effect of vineyard locations, varieties, and rootstocks on the juice amino acid composition of several cultivars. Am J Enol Vitic. 1989;40:135–139.

358. Hubáčková M, Hubáček V. Frost resistance of grapevine buds on different rootstocks (in Russian). Vinohrad. 1984;22:55–56.

359. Hubbard S, Rubin Y. The quest for better wine using geophysics. Geotimes. 2004;49(8):30–34.

360. Huglin, P. (1958) Recherches sur les bourgeons de la vigne. Initiation Florale et Dévéloppement Végétatif. Doctoral Thesis, University of Strasbourg, France.

361. Huisman S, Hubbard S, Redman D, Annan P. Monitoring soil water content with ground-penetrating radar: a review. Vadose Zone J. 2003;2:476–489.

362. Humphry M, Consonni C, Panstruga R. Mlo-based powdery mildew immunity: silver bullet or simply non-host resistance? Mol Plant Pathol. 2006;7:605–610.

363. Hunt JS. Wood-inhabiting fungi: protective management in the vineyard. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999;426a:125–126.

364. Hunter JJ. Plant spacing implications for grafted grapevine, II Soil water, plant water relations, canopy physiology, vegetative and reproductive characteristics, grape composition, wine quality and labour requirements. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 1998;19:35–51.

365. Hunter JJ, Le Roux DJ. The effect of partial defoliation on development and distribution of roots of Vitis vinifera L cv Cabernet Sauvignon grafted onto rootstock 99 Richter. Am J Enol Vitic. 1992;43:71–78.

366. Hunter JJ, Visser JH. The effect of partial defoliation, leaf position and developmental stage of the vine on the photosynthetic activity of Vitis vinifera L cv Cabernet Sauvignon. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 1988;9(2):9–15.

367. Hunter JJ, Volschenk CG. Effect of altered canopy: root volume ratio on grapevine growth compensation. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2001;22:27–31.

368. Hunter JJ, Volschenk CG, Fouché GW, Le Roux DJ, Burger E. Performance of Vitis vinifera L cv Pinot noir/99Richter as affected by plant spacing. In: Henick-Kling T, ed. Proc 4th Int Symp Cool Climate Vitic Enol. Geneva, NY: New York State Agricultural Experimental Station; 1996; pp. I-40–45.

369. Iacono F, Bertamini M, Scienza A, Coombe BG. Differential effects of canopy manipulation and shading of Vitis vinifera L cv Cabernet Sauvignon Leaf gas exchange, photosynthetic electron transport rate and sugar accumulation in berries. Vitis. 1995;34:201–206.

370. Iglesias JLM, Dabiila FH, Marino JIM, De Miguel Gorrdillo C, Exposito JM. Biochemical aspects of the lipids of Vitis vinifera grapes (Macabeo var.) Linoleic and linolenic acids as aromatic precursors. Nahrung. 1991;35:705–710.

371. Iland PG, Gawel R, Coombe BG, Henschke PM. Viticultural parameters for sustaining wine style. In: Stockley CS, ed. Proc 8th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1993:167–169.

372. Iland PG, Gawel R, McCarthy MG, et al. The glycosyl-glucose assay – Its application to assessing grape composition. In: Stockley CS, ed. Proc 9th Aust Wine Ind Tech Conf. Adelaide, Australia: Winetitles; 1996:98–100.

373. Ingels CA, Scow KM, Whisson DA, Drenovsky RE. Effects of cover crops on grapevines, yield, juice composition, soil microbial ecology and gopher activity. Am J Enol Vitic. 2005;56:19–29.

374. Intrieri C, Filippetti I. A new grape training system to suit machine pruning. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2012;580 41–42, 44–45, 47–48.

375. Intrieri C, Poni S. Integrated evolution of trellis training systems and machines to improve grape quality and vintage quality of mechanized Italian vineyards. Am J Enol Vitic. 1995;46:116–127.

376. Intrieri C, Silvestroni O, Rebucci B, Poni S, Filippetti I. The effects of row orientation on growth, yield, quality, and dry matter partitioning in Chardonnay wines trained to simple curtain and spur-pruned cordon. In: Henick-Kling T, ed. Proc 4th Int Symp Cool Climate Vitic Enol. Geneva, NY: New York State Agricultural Experimental Station; 1996; pp. I-10–15.

377. Intrieri C, Filippetti I, Allegro G, Valentini G, Pastore C, Colucci E. The semi-minimal-pruned hedge: a novel mechanized grapevine training system. Am J Enol Vitic. 2011;62:312–318.

378. Intrigliolo DS, Lakso AN. Berry abscission is related to berry growth in Vitis labruscana ‘Concord’ and Vitis vinifera ‘Riesling’. Vitis. 2009;48:53–54.

379. Iriti M, Rossoni M, Borgo M, Faoro F. Benzothiadiazole enhances resveratrol and anthocyanin biosynthesis in grapevine, meanwhile improving resistance to Botrytis cinerea. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:4406–4413.

380. Iriti M, Vitalini S, Di Tommaso G, D’Amico S, Borgo M, Faoro F. New chitosan formulation prevents grapevine powder mildew infection and improves polyphenol content and free radical scavenging activity of grape and wine. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2011;17:263–269.

381. Jackson DI. Factors affecting soluble solids, acid, pH, and color in grapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 1986;37:179–183.

382. Jacometti MA, Wratten SD, Walter M. Management of understorey to reduce the primary inoculum of Botrytis cinerea: enhancing ecosystem services in vineyards. Biol Cont. 2007;40:57–64.

383. Jacometti MA, Wratten SD, Walter M. Review: alternatives to synthetic fungicides for Botrytis cinerea management in vineyards. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2010;16:154–172.

384. James DG, Rayner M. Toxicity of viticultural pesticides to the predatory mites Amblyseius victoriensis and Typhlodromus doreenae. Plant Protect Quart. 1995;10:99–102.

385. Jashemski WF. Excavation in the Foro Boario at Pompeii: a preliminary report. Am J Archaeol. 1968;72:69–73.

386. Jashemski WF. The discovery of a large vineyard at Pompeii: University of Maryland Excavations, 1970. Am J Archaeol. 1973;77:27–41.

387. Jenkins A. Review of production techniques for organic vineyards. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1991;328 133, 135–138, 140–141.

388. Jermini M, Blaise P, Gessler C. Quantitative effect of leaf damage caused by downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) on growth and yield quality of grapevine ‘Merlot’ (Vitis vinifera). Vitis. 2010;49:77–85.

389. John S, Wicks TJ, Hunt JS, Scott ES. Colonisation of grapevine wood by Trichoderman harzianum and Eutypa lata. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2008;14:18–24.

390. Johnson H. Vintage: The Story of Wine New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 1989; pp. 109,124.

391. Johnson LF, Roczen DE, Youkhana SK, Nemani RR, Bosch DF. Mapping vineyard leaf area with multispectral satellite imagery. Computers Electronics Agric. 2003;38:33–44.

392. Johnston AE. Soil organic matter, effects on soils and crops. Soil Use Manage. 1986;2:97–105.

393. Johnston PA. Huc pater O Lenaee veni: the cultivation of wine in Vergil’s. Georgics J Wine Res. 1999;10:207–221.

394. Jones HG. Monitoring plant and soil water status: established and novel methods revisited and their relevance to studies of drought tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:119–130.

395. Jones HG, Stoll M, Santos T, de Sousa C, Chaves MM, Grant OM. Use of infrared thermography for monitoring stomatal closure in the field: application to grapevine. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:2249–2260.

396. Jordan TD, Pool RM, Zabadal TJ, Tomkins JP. Cultural Practices for Commercial Vineyards Ithaca, NY: New York State College of Agriculture, Cornell University; 1981; Miscellaneous Bulletin 111.

397. Jörger V. Ökasystem Weinberg aus der Sisht des Bodenlebens, Teil I Grundlagen der Untersuchungen und Auswirkungen der Herbizide. Wein Wiss. 1990;45:146–155.

398. Joscelyne VL, Downey MO, Mazza M, Bastian SEP. Partial shading of Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz vines altered wine color and mouthfeel attributes, but increased exposure had little impact. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:10888–10896.

399. Jung HW, Tschaplinski TJ, Wang L, Glazebrook J, Greenberg JT. Priming of systemic plant immunity. Science. 2009;324:89–91.

400. Karagiannidis N, Velemis D, Stavropoulos N. Root colonization and spore population by VA-mycorrhizal fungi in four grapevine rootstocks. Vitis. 1997;36:57–60.

401. Karban R, English-Loeb G, Hougen-Eitzman D. Mite vaccinations for sustainable management of spider mites in vineyards. Ecol Applic. 1997;7:183–193.

402. Keeley K, Preece JE, Taylor BH, Dami IE. Effects of high auxin concentrations, cold storage, and cane position on improved rooting of Vitis aestivalis Michx Norton cuttings. Am J Enol Vitic. 2004;55:265–268.

403. Keller M. Can soil management replace nitrogen fertilisation? – A European perspective. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1997;408 23–24, 26–28.

404. Keller M, Koblet W. Stress-induced development of inflorescence necrosis and bunch-stem necrosis in Vitis vinifera L in response to environmental and nutritional effects. Vitis. 1995;34:145–150.

405. Keller M, Arnink KJ, Hrazdina G. Interaction of nitrogen availability during bloom and light intensity during veraison I Effects on grapevine growth, fruit development, and ripening. Am J Enol Vitic. 1998;49:333–340.

406. Keller M, Kummer M, Vasconcelos MC. Reproductive growth of grapevines in response to nitrogen supply and rootstock. J Grape Wine Res. 2001;7:12–18.

407. Keller M, Viret O, Cole FM. Botrytis cinerea infection in grape flowers: defense reaction, latency and disease expression. Phytopathology. 2003;93:316–322.

408. Keller M, Mills LJ, Wample RL, Spayd SE. Cluster thinning effects on three deficit-irrigated Vitis vinifera cultivars. Am J Enol Vitic. 2005;56:91–103.

409. Kennedy JA, Matthews MA, Waterhouse AL. Effect of maturity and vine water status on grape skin and wine flavonoids. Am J Enol Vitic. 2002;53:268–274.

410. Kennelly MM, Gadoury DM, Wilcox WF, Magarey PA, Seem RC. Primary infection, lesion productivity, and survival of sporangia in the grapevine downy mildew pathogen Plasmopara viticola. Phytopathology. 2007;97:512–522.

411. Khmel IA, Sorokina TA, Lemanova NB, et al. Biological control of crown gall in grapevine and raspberry by two Pseudomonas spp with a wide spectrum of antagonistic activity. Biocont Sci Technol. 1998;8:45–57.

412. King PD, Rilling G. Further evidence of phylloxera biotypes, variations in the tolerance of mature grapevine roots related to the geographical origin of the insect. Vitis. 1991;30:233–244.

413. Kirchhof G, Blackwell J, Smart RE. Growth of vineyard roots into segmentally ameliorated acid subsoils. Plant Soil. 1990;134:121–126.

414. Kirchmann, H., Ryan, M.H., 2004. Nutrients in organic farming – are there advantages from the exclusinve use of organic manures and untreated minerals? In: 4th Int. Crop Science Cong. New Directions for a Diverse Planet Sept. 26 to Oct. 1, Brisbane, Australia, p. 32.

415. Kirchmann H, Thorvaldsson G. Challenging targets for future agriculture. Eur J Agron. 2000;12:145–161.

416. Kirchmann H, Johnston AEJ, Bergström LF. Possibilities for reducing nitrate leaching from agricultural land. Ambio. 2002;31:404–408.

417. Kirchmann H, Haberhauer G, Kandeler E, Sissitsch A, Gerzabek HH. Effects of level and quality of organic matter input on soil carbon storage and microbial activity in soil – Synthesis of a long-term experiment. Global Biogeochem. 2004;18:GB4011.

418. Kirk JL, Beaudette LA, Hart M, et al. Methods of studying soil microbial diversity. J Microbiol Meth. 2004;58:169–188.

419. Kirk JTO. Performance of ‘frost insurance’ canes at Clonakilla during the 1998/1999 season. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 1999;247:61–62.

420. Kiss J, Szendrey L, Schlösser E, Kotlár I. Application of natural oil in IPM of grapevine with special regard to predatory mites. J Environ Sci Health. 1996;B31:421–425.

421. Klausner S. Managing animal manures. Organic Grape Wine Symp 21–22 March, 1995 Geneva, NY: New York State Agricultural Experimental Station; 1995; <http://www.nyases.cornell.edu/hort/faculty/pool/organicvitwkshp/%208Klausner.pdf>.

422. Kliewer WM. Methods for determining the nitrogen status of vineyards. In: Rantz JM, ed. Proc Int Symp Nitrogen Grapes and Wine. Davis, CA: American Society of Enology Viticulture; 1991:133–147.

423. Kliewer WM, Dokoozlian NK. Leaf area/crop weight ratios of grapevines: influence on fruit composition and wine quality. Am J Enol Vitic. 2005;56:170–181.

424. Kliewer WM, Bowen P, Benz M. Influence of shoot orientation on growth and yield development in Cabernet Sauvignon. Am J Enol Vitic. 1989;40:259–264.

425. Koblet W, Candolfi-Vasconcelos MC, Zweifel W, Howell GS. Influence of leaf removal, rootstock, training system on yield and fruit composition of Pinot noir grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 1994;45:181–187.

426. Kobriger JM, Kliewer WM, Lagier ST. Effects of wind on water relations of several grapevine cultivars. Am J Enol Vitic. 1984;35:164–169.

427. Kodur S, Tisdall JM, Tang C, Walker RR. Accumulation of potassium in grapevine rootstocks (Vitis) grafted to ‘Shiraz’ as affected by growth, root-traits and transpiration. Vitis. 2010;49:7–13.

428. Koenig R, An D, Burgermeister W. The use of filter hybridization techniques for the identification, differentiation and classification of plant viruses. J Virol Methods. 1988;19:57–68.

429. Komar V, Vigne E, Demangeat G, Fuchs M. Beneficial effect of selective virus elimination on the performance of Vitis vinifera cv Chardonnay. Am J Enol Vitic. 2007;58:202–210.

430. Kondo N. Harvesting robot based on physical properties of grapevine. Jpn Agr Res Q. 1995;29:171–178.

431. Kontoudakis N, Esteruelas M, Fort F, Canals JM, De Freitas V, Zamora F. Influence of the heterogeneity of grape phenolic maturity on wine composition and quality. Food Chem. 2011;124:767–774.

432. Kopf A, Schirra K-J, Schropp A, Blaich R, Merkt N, Louis F. Effect of nitrogen fertilisation on the development of phylloxera root damage in laboratory and field trials. Aust Grapegrower Winemaker. 2000;440(56):58–62.

433. Kopyt M, Ton Y. Trunk and berry size monitoring: applications for irrigation. Aust NZ Grapegrower Winemaker. 2007;517:33–39.

434. Koundouras S, Hatzidimitriou E, Karamolegkou M, et al. Irrigation and rootstock effects on the phenolic concentration and aroma potential of Vitis vinifera L cv Cabernet Sauvignon grapes. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:7805–7813.

435. Kramer PJ. Water Relations in Plants New York, NY: Academic Press; 1983.

436. Krasnow M, Weis W, Smith RJ, Benz MJ, Matthews M, Shackel K. Inception, progression, and compositional consequences of a berry shrivel disorder. Am J Enol Vitic. 2009;60:24–34.

437. Krastanova S, Perrin M, Barbier P, et al. Transformation of grapevine rootstocks with the coat protein gene of grapevine fanleaf nepovirus. Plant Cell Reports. 1995;14:550–554.

438. Kretschmer M, Kassemeyer H-H, Hahn M. Age-dependent grey mould susceptibility and tissue-specific defence gene activation of grapevine berry skins after infection by Botrytis cinerea. J Phytopath. 2007;155:258–263.

439. Kriedemann PE, Smart RE. Effects of irradiance, temperature, and leaf water potential on photosynthesis of vine leaves. Photosynthetica. 1971;5:6–15.

440. Krogh P, Carlton WW. Nontoxicity of Botrytis cinerea strains used in wine production. In: Webb AD, ed. Grape and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings 1980. Davis, CA: University of California; 1982:182–183.

441. Kruckeberg AR. California serpentines: flora, vegetation, geology, soils and management Problems. Univ Cal Publ Bot. 1986;78:180.

442. Kubečka D. I’influence exercée par l’espacement sur le système radiculaire de la vigne. Rev Hortic Vitic. 1968;17:193–199.

443. La Guerche S, Chamont S, Blancard D, Dubourdieu D, Darriet P. Origin of (−)-geosmin on grapes: on the complementary action of two fungi, Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2005;88:131–139.

444. La Guerche S, Dauphin B, Pons M, Blanchard D, Darriet P. Characterization of some mushroom and earthy off-odors microbially induced by the development of rot on grapes. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:9193–9200.

445. Lacroux F, Tregoat O, van Leeuwen C, et al. Effect of foliar nitrogen and sulphur application on aromatic expression of Vitis vinifera L cv Sauvignon blanc. J Int Sci Vigne Vin. 2008;42:125–132.