1. Rapid development of a large canopy surface area/volume ratio increases photosynthetic efficiency, as well as fruit set and ripening. Tall thin vertical canopies aligned along a north–south axis permit maximal sun exposure.

2. To avoid both excessive interrow shading and energy loss by insufficient canopy development, the ratio of canopy height to interrow width between canopies should approximate unity.

3. Shading in the renewal or fruit-bearing zone of the canopy should be minimized. Shading has several undesirable influences on fruit maturation and health. These include augmented potassium levels, increased pH and herbaceous character, retention of malic acid, enhanced susceptibility to powdery mildew and bunch rot, and reduced sugar, tartaric acid, monoterpene, anthocyanin, and tannin levels. Shading also reduces inflorescence initiation, favors primary bud necrosis, suppresses fruit set, and slows berry growth and ripening. There is no precise indication of the level of shading at which undesirable influences begin.

4. Excessive and prolonged shoot growth, causing a drain on the carbohydrate available for fruit maturation and vine storage, should be restrained by trimming or devigoration procedures (see later). There should be no vegetative growing point activity after véraison.

5. The location of different parts of the vine in distinct regions not only favors uniform growing conditions and even fruit maturation, but also facilitates mechanized pruning and harvesting.

These principles have also been combined into a training system ideotype (Table 4.5) and a vineyard score sheet (Smart and Robinson, 1991). These assess features such as the termination of shoot growth after véraison (an indicator of moderate vegetative vigor and slight water and nutrient deficit) and solar fruit exposure. Vineyard scoring has proven valuable, in association with wine assessment, in quantifying vineyard practices that are the most significant in defining grape quality.

Table 4.5

Canopy Characteristics Promoting Improved Grape Yield and Quality

| Character assessed | Optimal value | Justification of optimal value |

| Canopy characters Row orientation |

North–south | Promotes radiation interception (Smart, 1973), although Champagnol (1984) argues that hourly interception should be integrated with other environmental conditions (i.e., temperature) that affect photosynthesis to evaluate optimal row orientation for a site; wind effects can also be important (Weiss and Allen, 1976a,b) |

| Ratio of canopy height to alley width | ~1:1 | High values lead to shading at canopy bases, and low values lead to in efficiency of radiation interception (Smart et al., 1990b) |

| Foliage wall inclination | Vertical or nearly so | Underside of inclined canopies is shaded (Smart and Smith, 1988) |

| Renewal/fruiting area location | Near canopy top | A well-exposed renewal/fruiting area promotes yield and, generally, wine quality, although phenols may be increased above desirable levels |

| Canopy surface area | ~21,000 m2/ha | Lower values generally indicate incomplete sunlight interception; higher values are associated with excessive cross-row shading |

| Ratio of leaf area to surface area | <1.5 | An indication of low canopy density is especially useful for vertical canopy walls (Smart, 1982; Smart et al., 1985) |

| Shoot spacing | ~15 shoots/m | Lower values are associated with incomplete sunlight interception, higher values with shade; optimal values is for vertical shoot orientation and varies with vigor (Smart, 1988) |

| Canopy width | 300–400 mm | Canopies should be as thin as possible; values quoted are minimum likely width, but actual value will depend on petiole and lamina lengths and orientation |

| Shoot and fruit characters Short length | 10–15 nodes, ~600–900 mm length | These values are normally attained by shoot trimming; short shoots have leaf area to ripen fruit, and long shoots insufficient contribute to canopy shade and cause elevated must and wine pH |

| Lateral development | Limited, say, less than 5–10 lateral nodes total per shoot | Excessive lateral growth is associated with high vigor (Smart et al., 1985; Smart and Smith, 1988; Smart, 1988, 1990b) |

| Ratio of leaf area to fruit mass | ~10 cm2/g (range 6–15 cm2/g) | Smaller values cause inadequate ripening, and higher values lead to increased pH (Shaulis and Smart, 1974; Peterson and Smart, 1975; Smart, 1982; Koblet, 1987); a value around 10 is optimal |

| Ratio of yield to canopy surface area | 1–1.5 kg fruit/m2 canopy surface | This is the amount of exposed canopy surface area required to ripen grapes (Shaulis and Smart, 1974); values of 2.0 kg/m2 have been found to be associated with ripening delays in New Zealand, but higher values may be possible in warmer and more sunny climates |

| Ratio of yield to total cane mass | 6–10 | Low values are associated with low yields and excessive shoot vigor; higher values are associated with ripening delays and quality reduction |

| Growing tip presence after véraison | Nil | Absence of growing tip encourages fruit ripening since actively growing shoot tips are an important alternate sink to the cluster (Koblet, 1987) |

| Cane mass (in winter) | 20–40 g | Values indicate desirable vigor level: leaf area is related to cane mass, with 50–100 cm2 leaf area/g cane mass, but values will vary with variety and shoot length (Smart and Smith, 1988; Smart et al., 1990a) |

| Internode length | 60–80 mm | Values indicate desirable vigor level (Smart et al., 1990a) but will vary with variety |

| Ratio of total cane mass to canopy length | 0.3–0.6 kg/m | Lower values indicate canopy is too sparse, and higher values indicate shading; values will vary with variety and shoot length (Shaulis and Smart, 1974; Shaulis, 1982; Smart, 1988) |

| Microclimate characters | ||

| Proportion of canopy gaps | 20–40% | Higher values lead to sunlight loss, and lower values can be associated with shading (Smart and Smith, 1988; Smart, 1988) |

| Leaf layer number | 1–1.5 | Higher values are associated with shading and lower values with incomplete sunlight interception (Smart, 1988) |

| Proportion of exterior fruit | 50–100% | Interior fruit has composition defects |

| Proportion of exterior leaves | 80–100% | Shaded leaves cause yield and fruit composition defects |

Source: From Smart et al., 1990b, reproduced by permission.

Choice of Training System

Selecting a training system requires serious assessment of climate-imposed limitations. In most established regions, there are usually several well-established alternative systems. These now frequently include several modern training systems, devised to solve particular problems. However, in new viticultural regions, without clearly definable equivalents, personally designing a training system to match local conditions may be worthwhile. While novel and experimental, this offers the possibility of developing of a system specific to local conditions. It could involve selecting choices based on the principles noted above. This may be preferable to attempting to adjust existing systems to situations distinct from those for which they were designed.

Selected Training Systems

Smart and Robinson (1991) provide an exhaustive discussion of training systems designed to improve canopy management, as well as yield. What follows below is a brief discussion of some of these systems. Regrettably, the literature provides few experimental comparisons of these or other systems, on which to base judgments. The work of Wolf et al. (2003) and Gladstone and Dokoozlian (2003) are welcome exceptions.

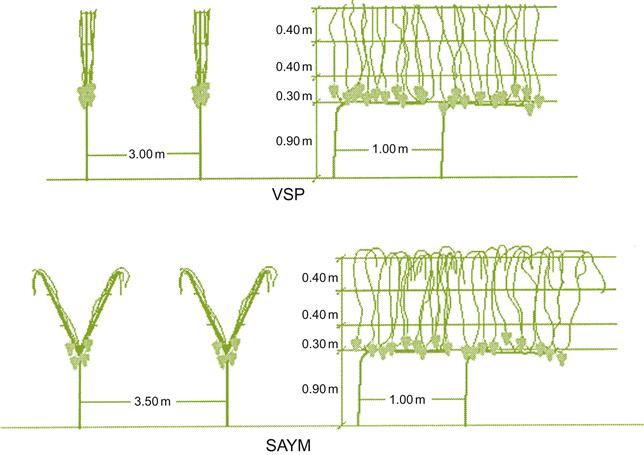

Vertical Shoot Positioning (Vsp)

Vertical shoot positioning (VPS) (Plate 4.5) refers to a group of popular training systems extensively utilized in Europe and elsewhere. They possess undivided canopies that resemble hedgerows. They are particularly useful with vines of low to medium vigor, and in regions prone to fungal disease, where the vines are planted in narrow rows (1.5–2 m apart). Where the vines are cane-pruned, four canes are usually retained. Pairs of canes are directed in opposite directions along two parallel support wires, positioned about 0.2 m apart. If the vines are spur-pruned, two cordons are directed in opposite directions along a single support wire. In both situations, the shoots are trained upwards using two foliage wires. The shoots are trimmed at the top and frequently along the sides. The result is a hedge about 0.4–0.6 m wide and 1 m high.

VSP systems position the fruit in a common zone about 1–1.2 m above the ground. This eases most vineyard activities, such as mechanical harvesting and selective fruit spraying. As long as the vines are not overly vigorous, fruit shading is usually not a problem. Where shading is likely to lower fruit quality, basal leaf removal is facilitated by the fruit zone being at chest height. Improved light and air exposure, and an efficient canopy, generally favor good to excellent fruit yield and quality.

An interesting variation of the VSP, termed SAYM, is illustrated in Fig. 4.19. It permits the canopy to be opened in a Y position to achieve some of the same benefits of the Lyre system.

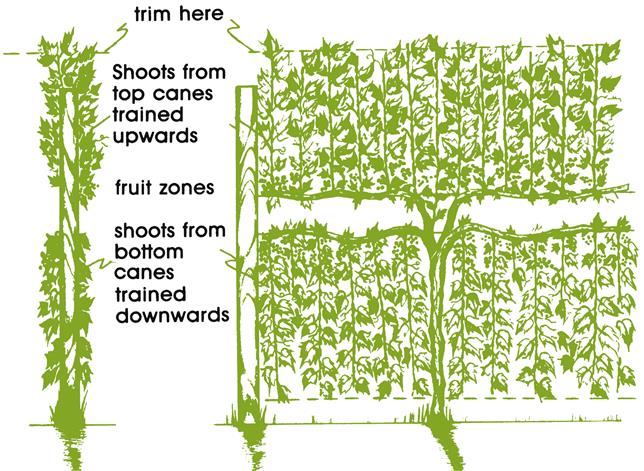

Scott Henry and Smart-Dyson Systems

The Scott Henry is another specific VSP variant. It may be either cane- or spur-pruned. With cane pruning, four canes are retained and pairs are directed in opposite directions along the row, attached either to the upper or lower support wire. It differs from a standard VSP by directing the shoots from the upper canes upward and those from the lower canes downward. With spur pruning, cordons from adjacent vines are trained alternatively to the upper and lower support wires (Fig. 4.20). Upward positioned spurs are retained on higher cordons (the direction in which the shoots will be directed), whereas downward located spurs are retained on lower cordons. Several foliage wires hold the shoots in position.

The Scott Henry generates a vertically divided canopy. It both increases the effective canopy surface area by about 60% and reduces its density. Canopy division also improves light exposure and air circulation around the crop. Because the fruit on both canes develop in approximately the same zone, they ripen essentially simultaneously. Devigoration imposed on the lower canopy by its downward direction is of value for vines of medium vigor. As a consequence, photosynthate otherwise consumed in unnecessary vegetative growth can be directed into enhanced production of high-quality fruit. Improved sugar content and reduced acidity are combined with increased yield.

The Scott Henry, as with other VSP systems, is most effective when associated with vine rows between 1.5 and 2 m apart. It is well adapted to use with conventional mechanical harvesters. Conversion from other systems is comparatively simple.

The Smart–Dyson Trellis is a modification of the Scott Henry (Smart, 1994b). It involves using a single cordon to generate both the upward- and downward-facing canopies. These are derived from upward- and downward-facing spurs, respectively. The timing and manner of shoot positioning are essentially the same as the Scott Henry. The primary advantage of the Smart–Dyson modification is its adaptation to mechanical pruning – all the cutting can be conducted in a single plane. Establishment costs are also somewhat less.

For spur-pruned, cordon-trained vineyards desiring an inexpensive retrofit to a divided-canopy system, Smart (1994a) suggests the Ballerina modification of the Smart–Dyson. Because the cordons do not possess buds originating on the underside, some of the shoots are trained upward, whereas others are trained outward and downward.

Geneva Double Curtain (GDC)

The Geneva Double Curtain (GDC) was the first training system based on microclimate analysis (Shaulis et al., 1966) (Fig. 4.15B). It is a tall (1.5–1.8 m) bilateral cordon system, pruned to spurs possessing four to six buds. Those selected are downward directed. The cordons diverge laterally and then bend, to be held about 1.2 m apart by parallel wires running along the row. Alternatively, two short lateral cordons are pruned to four long canes. The latter are supported on wires. The bearing shoots of upright-growing V. vinifera cultivars must be positioned downward about flowering time with the aid of movable catch wires. The system works well for vines of medium to high vigor, and with rows about 3–3.6 m apart. This provides interrow canopy spacings of about 2.4 m. Some further shoot positioning during the season may be necessary to keep the two canopies separate and minimize shading.

Initially developed for V. labrusca varieties, such as Concord, the GDC has been used with French-American hybrids and V. vinifera cultivars in several parts of the world. Consistent with its divided canopy and increased bud retention, fruit quality is often excellent and yield enhanced. Although the GDC system demands more in terms of skill and materials, the higher yield (excellent sun exposure for inflorescence induction) usually more than offsets the higher establishment costs. The use of hinged side supports on the trellis can easily permit the canopies to be pulled toward the post, facilitating mechanical pruning and harvesting (Smith, 1991).

Because the GDC positions the fruit-bearing or renewal zone at the apex of the canopy, it is especially valuable where maximal direct-sun exposure is desired, as in regions with considerable cloud cover during the summer. In some regions, however, this can result in increased fruit sunburn, hail injury, and bird damage. Locating the arms on the upper portion of the cordon, or arranging for less shoot arching, may enhance foliage protection of the fruit. Because trailing shoots need little support, GDC has the lowest wiring costs of any divided-canopy system.

Lyre or U System

The Lyre is a divided-canopy system appropriate for vines of medium vigor (Carbonneau, 1985). The system consists of a short trunk branching into bilateral cordons. These diverge laterally, each branching into two cordons that now run parallel along cordon wires positioned about 0.7 m apart (Plate 4.6). The bearing wood consists of equidistantly positioned spurs. The shoots are trained to two inclined trellises, supported by fixed and movable catch wires. Rows are placed about 3–3.6 m apart, with about 2.4 m separating vines within the row. The Lyre has been described as an inverted GDC. Trimming excessive growth may be needed to keep the canopies separate and minimize basal shading.

The inclined canopies are ideally suited for maximizing direct sun exposure in the morning and afternoon, when photosynthetic efficiency is at its maximum. However, this advantage comes at the cost of extensive shading at the exterior base of the canopy by the overhanging inclined vegetation (Fig. 4.21). In addition, its establishment costs are higher than standard wide-row systems, including an increase in the number of foliage wires required.

The Lyre disperses capacity over a large canopy. It generates increased yield, with equal or better quality fruit than that produced using more traditional dense plantings, such as with the double Guyot (Carbonneau and Casteran, 1987; Carbonneau, 2004). In Bordeaux, the value of the Lyre system is particularly evident on less-favored sites and during poorer vintage years. These advantages may arise from the increased canopy size and the beneficial microclimate generated. Also, it has been noted that Lyre-trained vines are less susceptible to winter injury and inflorescence necrosis (coulure). The system is amenable to both mechanical harvesting and pruning, with adjustment to existing equipment.

When vines are converted from vertical training to the Lyre system, there is no concomitant increase in root volume (Hunter and Volschenk, 2001). The result is an increase in cordon length to root volume ratio. Total cane growth increases although individual canes are shorter.

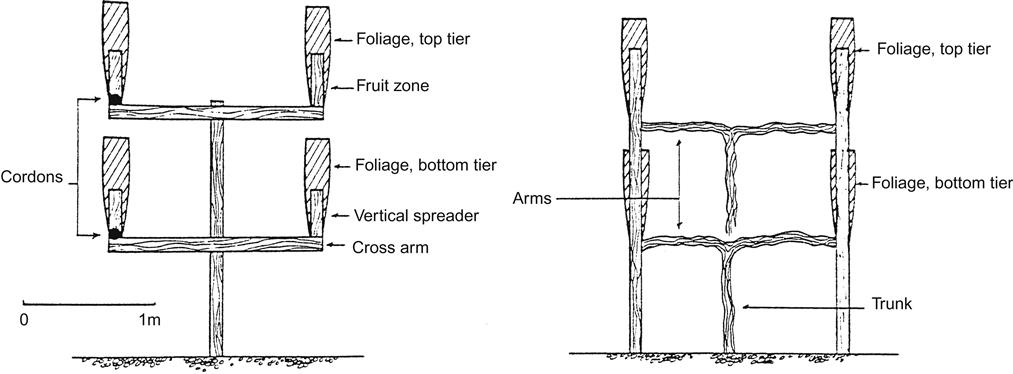

Ruakura Twin Two Tier (RT2T)

The Ruakura Twin Two Tier (RT2T) system was specifically developed for high-fertility conditions. It differs from the previous systems by dividing the canopy both vertically and laterally (Fig. 4.22). Each cordon bends along, and is supported by, wires running parallel to the row (Plate 4.7). Spur pruning facilitates both equal and uniform distribution of the canopies along the row. The RT2T system is compatible with mechanical pruning. Vertical canopy division is achieved by training alternate vines high and low, to higher and lower cordon wires, respectively. This is necessary to avoid gravitrophic effects on growth in individual vines, where buds positioned higher on a vine tend to grow more vigorously than those nearer the ground. Rows are placed 3.6 m apart. As the between-row canopies are positioned 1.8 m apart, the same as the within-row canopies, all canopies are equally separated. Also, as the combined height of the two vertical canopies (tiers) is equivalent to the width between the canopies, the ratio of canopy height to interrow canopy separation is unity. Individual vines are planted about 2 m apart in the rows.

To limit shading of the lower tier, trimming maintains a gap of about 15 cm (6 in) between the two canopies. An alternative technique places the two cordons of each tier about 15 cm apart, with the upper canopy trained upward and the lower trailing downward. By positioning the fruit-bearing regions of both tiers under approximately the same environmental conditions, chemical differences between the fruit from both tiers is minimized.

Advantages of RT2T training involve a high leaf surface area to canopy volume ratio and extensive cordon development. The former favors the creation of a limited water deficit that helps restrict shoot growth following blooming. As a result, most of the photosynthate is available for fruit development or storage. The formation of 4 m of cordon per row meter provides many well-spaced shoots per vine; these further act to limit vine vigor by restricting internode elongation and leaf enlargement, thereby lessening canopy shading. Increased shoot numbers also enhance vine productivity, and a desirable canopy microclimate maintains or enhances grape quality. Because of the strong vigor control provided by RT2T training, it is particularly useful for vigorous vines grown on deep rich soils with an ample water supply.

Although RT2T systems are more complex and expensive to establish than traditional systems, wide-row spacing limits planting costs. Also, the narrow vertical canopies ease mechanical pruning and harvesting, and increase the effectiveness of protective chemical application.

Tatura Trellis

Several training systems have been developed from canopy management principles designed for tree fruit crops. An example is the modified Tatura Trellis (van den Ende, 1984). It possesses a 2.8 m high, V-shaped trellis arranged with support wires to hold six tiered, horizontally arranged cordons on both inclined planes. Each vine is divided near the base into two inclined trunks. Each trunk gives rise to six short cordons, three on each side that run parallel to the row. Alternately, the vines are trained either high or low to limit gravitrophic effects, while still providing six cordon tiers. The vines are spur-pruned. A third placement system consists of using the bilateral trunks directly as inclined cordons (van den Ende et al., 1986). The vines are then pruned with alternate regions of the trellis used for fruit and replacement shoot development.

In the Tatura Trellis, the vines are densely planted at one vine per row meter, with rows spaced 4.5–6 m apart. Because of root competition between the closely spaced vines, and the large number of shoots developed, excessive vigor is restricted, shading is limited, and fruit productivity is increased. The Tatura Trellis favors the early development of the vine’s fruiting potential.

The most serious limitation of the Tatura Trellis is its tendency to concentrate fruit production in the upper part of the trellis. In addition, the vine must be trained, pruned, and harvested manually, as it is unsuited to mechanical harvesting and pruning.

Minimal Pruning (Mpct)

Problems with the tendency to overprune, combined with a desire to reduce production costs, led to the development of the minimal pruning system (Plate 4.8). Without significant pruning, many cultivars come to regulate their own growth and yield good-quality fruit. Although vines may overcrop or undercrop in the first few years, especially young vines, this typically ceases by the fifth year. Spontaneous dehiscence of immature shoots largely eliminates the need for pruning old growth.

Minimally pruned vines produce more but smaller shoots; possess fewer, more closely positioned nodes; and develop smaller, paler leaves. Nevertheless, net photosynthesis and carbon gain are significantly higher than with other systems, for example VSP (Weyand and Schultz, 2006). The more open canopy also reduces the incidence of fungal diseases, notably bunch rot. Most cultivars maintain their shape and vigor when minimally pruned. Vines not already cordon-trained are so developed on a high (1.4–1.8 m) single wire. Summer trimming is limited to a light skirting along the sides and bottom, as deemed necessary to facilitate machinery movement.

Crop yield is either sustained or considerably enhanced, depending on the variety, clone, and rootstock employed. The fruit is carried on an increased number of bunches, each containing fewer and smaller berries. Commonly, the fruit is borne uniformly over the outer portion of the vine, in well-exposed locations. Fruit maturity is generally delayed about one to several weeks. Grape soluble solids may be slightly reduced, pH decreased, and acidity increased (McCarthy and Cirami, 1990). Fruit color in red cultivars is generally diminished slightly, but this may be offset by mechanical thinning, i.e., passing a mechanical harvester through the vineyard about a month after flowering. The effect is to reduce yield by about 30%, increase soluble solids, improve acidity, elevate the proportion of ionized anthocyanins, and enhance the color density of the resultant wine (Clingeleffer, 1993; Petrie and Clingeleffer, 2006; Diago et al., 2010). Data from trials in eastern North America are given in Fendinger et al. (1996).

The enhanced yield of minimally pruned vines may result from nutrients stored in the shoots (not lost as a result of pruning). The ready availability of nutrients may also explain the rapid completion of canopy development following bud burst. This helps limit leaf–fruit competition during berry development. An additional advantage of minimal pruning comes from easier fruit removal during mechanical harvest. Also, fewer leaves are removed along with the fruit due to canopy flexibility.

An unexpected benefit of minimal pruning has been a reduction in the incidence of diseases such as Eutypa dieback. The elimination of most pruning wounds, especially on wood 2 or more years old, decreases incidence of the disease. However, the retention of canes may lead to an increased incidence of Phomopsis cane and leaf spot, a rare disease in conventionally pruned vineyards (Pool et al., 1988).

Minimal pruning appears to be best suited to situations in which the vines are moderately vigorous, are grown in dry climates, and with cultivars that ripen relatively early. The system appears to be less suitable for vines grown in poor soils, in arid conditions without the option of irrigation, or in cool wet climates. In cool regions, ripening may be critically delayed and vine self-regulation less pronounced. When used in appropriate climates, the fruit produces well-balanced wine, although occasionally lighter in color than those derived from vines trained and pruned traditionally.

Outside Australia, minimal pruning has found particular favor with V. labrusca growers in the eastern United States. Vines initiate growth earlier, producing canopies of similar size, but significantly in advance of heavily pruned vines (Comas et al., 2005). Yield is also increased. More efficient light use appears to be the source of the increased fruit productivity. Root development tends to be more shallow, initiate earlier, and be more extensive (by up to 24%) than balance-pruned vines. It has also been used successfully in Germany with Riesling and Pinot noir (Schultz et al., 2000) and South Africa with a variety of cultivars (Archer and van Schalkwyk 2007). However, results in other European regions have been inconsistent, possibly due to climatic variables or use with late maturing cultivars. In this regard, Intrieri et al. (2011) have investigated a modification that incorporates many of the advantages of minimal pruning without the problems associated with some cultivars. It is termed semi-minimal-pruned hedging (SMPH). Additional details are found in Intrieri and Filippetti (2012).

Although different in several aspects, all these systems are designed to direct the benefits of improved plant health and nutrition toward enhanced fruit yield and quality. These goals are achieved by reducing individual shoot vigor and increasing sun and air exposure. The simpler divided-canopy systems are more suitable for vines of lower capacity (~0.5 kg/m prunings), whereas the more complex systems are more appropriate for vines of high capacity (~1.5 kg/m prunings). Although losing their advantages under situations of marked water and disease stress, poor drainage, or salt buildup, divided-canopy systems provide long-term economic benefits in several situations. Whether the yield and quality improvements justify their additional costs will depend on the profit derived when compared with more traditional procedures.

Ancient Roman Example

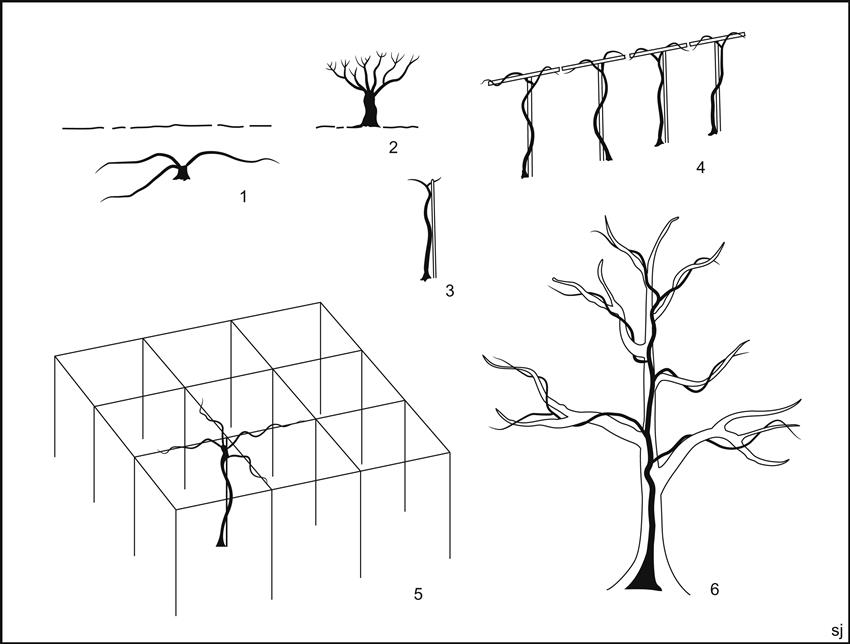

Although much has been learned about training systems in the past several decades, it is somewhat humbling to realize how many of our present ‘discoveries’ were known to the ancients. What follows is a short digression into Roman viticulture.

Descriptions of ancient viticultural practice come from the writings of Roman authors, notably Columella, Pliny the Elder, Varro, and Cato. For a discussion of some of Columella’s and Virgil’s views see Santon (1996) and Johnston (1999), respectively. Thankfully, direct access to English versions of these ancient texts is now available to anyone via the Internet. Their descriptions often give detailed instructions on how to plant vineyards, providing recommended distances between vines, advice on training and pruning, and suggested yields, as well as specifics on how to get the best out of one’s slaves. Their comments make it evident that they were well aware of the yield/quality conundrum; the advantages of fruit shading in hot sunny climates; basal leaf removal to improve fruit ripening; and site selection for particular cultivars. Nonetheless, some practices seem archaic, such as very deep planting of cutting and rooted shoots and ablaqueation (surface root pruning/exposure a few inches from the young trunk) (Columella, De Re Rustica 4.8).

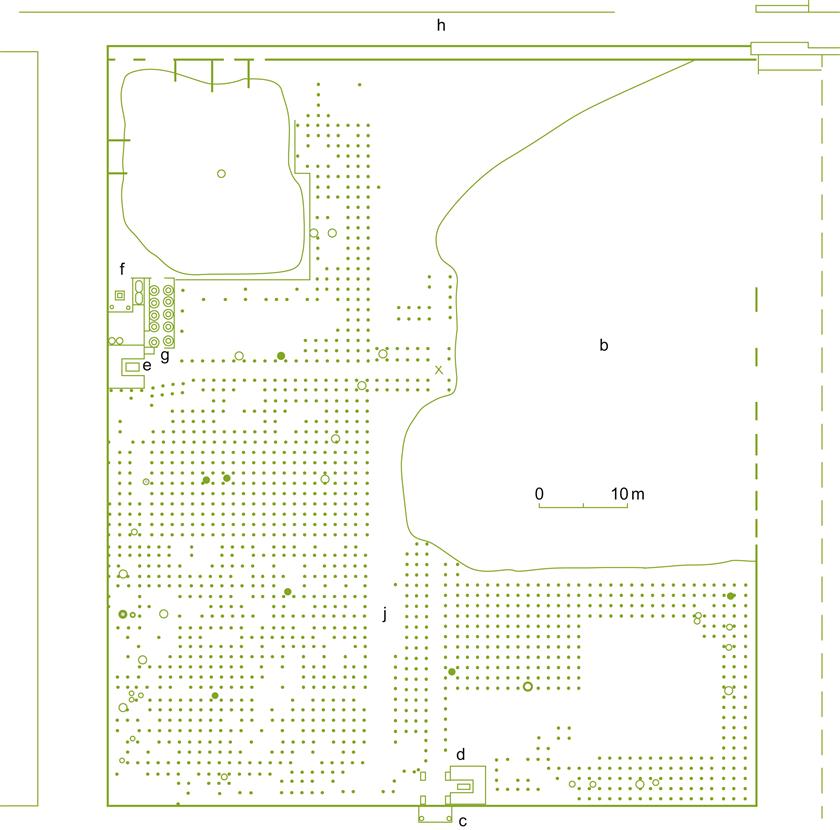

Until the late 1960s, no vineyards had been discovered that could confirm that the views of these Roman authors were applied. In 1968, Jashemski began excavating a site in Pompeii. Her work uncovered the largest known vineyard in the ancient world (Jashemski, 1968, 1973). The eruption of Vesuvius, in late August 79 A.D., buried the city under lapilli and volcanic ash, forming a time-capsule of Roman life. The site of the vineyard (Foro Boario) was first investigated in 1755, but mistakenly identified. Only some 200 years later was its actual function realized. It has revealed how closely vineyard layout followed the directions noted by Roman authors. Additional corroborative information can be obtained in Rossiter (1981, 2007). The winery associated with an ancient Roman villa has also been investigated in France (Languedoc) (Mauné, 2003).

The vineyard studied in Pompeii was comparatively small (about 0.56 ha), probably being operated by a single family. Many vineyards in Italy were in the range of about 12.5–25 ha (50–100 iugera) (Purcell, 1985). The site also contains a press room and fermentation area, as well as a wine shop and portico. Here the produce was sold, probably to patrons of the nearby amphitheater. The site also included two triclinia (stone lounges), associated with relaxed outdoor dining in the Roman manner.

The vineyard was planted with about 4000 vines (~7200 vines/ha) (Fig. 4.23). The vines were spaced about 4 Roman feet apart (~1.2 m). Although Columella suggested rows 5 ft apart for hand cultivation (at least 7 ft for cultivation with oxen and a plow), Pliny the Elder proposed 4 ft spacing on rich volcanic soils, such as those around Pompeii. Each vine was supported by a stake averaging 2.5–5.5 cm in diameter. The vines were probably pergola trained. This system was highly recommended by ancient authors for hot dry climates such as Pompeii. This and other Roman training systems are illustrated in Fig. 4.24. Many of these systems were in common use during medieval times, with some still being applied in various forms. Most vines also showed several depressions around the vine, presumably designed to catch rain. The vineyard was divided into quadrants by two paths between the vines (producing sections approximating those suggested by Columella (De Re Rustica 4.18). Columella recommends this practice because it should help the grower recognize the special needs of each plot in the vineyard. Furthermore, the paths facilitate transporting material in and out of the vineyard. Their sloped sides acted as sites for water drainage during downpours. Because of the presence of large diameter roots along the paths, and the thicker stakes in this region, it is suspected that the paths also functioned as vine arbors. A third path occurred along the northern edge of the vineyard.

Another characteristic feature illustrated by the vineyard was the implantation of trees. Not only was there a row of trees around the edges of the vineyard (usually between the second and third rows from the wall), but also a few trees randomly interspersed and widely spaced trees between the first and second rows along the central paths. These trees were often fruit bearing, such as fig, pear, plum, cherry or apple, along with poplar or willow (used as a source of stakes for training vines). The lower yield associated with growing vines on trees (arbustum) was considered to yield finer wines (Pliny, Historia Naturalis 17.166).

Although there is no evidence of the method or frequency of soil cultivation, ancient authors agree on its importance. Frequent hoeing was strongly recommended to control weeds and grass, their remains being left on the ground as a mulch. Columella specifically encouraged root pruning every 3 years in established vineyards. Other approaches recommended by ancient authors include basal leaf removal, monoculture, and the removal of unripe grapes from clusters before fermentation. Layering was the preferred method of propagation.

If the ancient proprietor in Pompeii followed accepted practice, one can assume that each vine was pruned to two buds on each of four spurs. This would have resulted in at least 16 clusters per vine. This equates to about 29 tons/ha, or some 160 hL of wine per ha. This estimate seems reasonable in terms of the volume of wine that could have been produced in the 10 dolia (large earthernware containers imbedded into the floor of the cella vinaria). Each dolium could contain up to about 10 hL (the equivalent of 40 amphoras). Although this currently would be considered overcropping, it is consistent with yields noted by Varro and Cato. It also would coincide with the recommendations of Columella that on level land (not optimal for grape quality), quantity be aimed for.

In 1996, Piero Mastroberardino was permitted to replant several vineyard regions in Pompeii (Thomson, 2004). The vines chosen were those presently grown in Campania, and which most resemble those shown in frescos found in Pompeii. The principal varieties are two red cultivars, Sciascinoso and Piedirosso. These are thought to correspond to the varieties Vitis oleagina and Columbina purpurea described by Pliny in Historia Naturalis. The vines have been planted in a manner similar to that of the Foro Boario vineyard described above, following instructions given by Pliny. Despite the ancient viticultural methods, the wine produced from the vineyards (called Villa dei Misteri) is made to modern specifications.

Vigor Regulation (Devigoration)

As noted previously, the rich soils of many New World vineyards promote vegetative growth, to the potential detriment of fruit quality. This feature may be accentuated by the use of vigorous rootstock, irrigation, fertilization, weed control, and the elimination of viral infections. The problem is not that the vines grow too well, but that too much capacity goes toward generating vegetative growth – an excess pruned away at the end of the season. The intention of vigor control is to limit vegetative growth and redirect the enhanced capacity into increased yield and improved fruit quality.

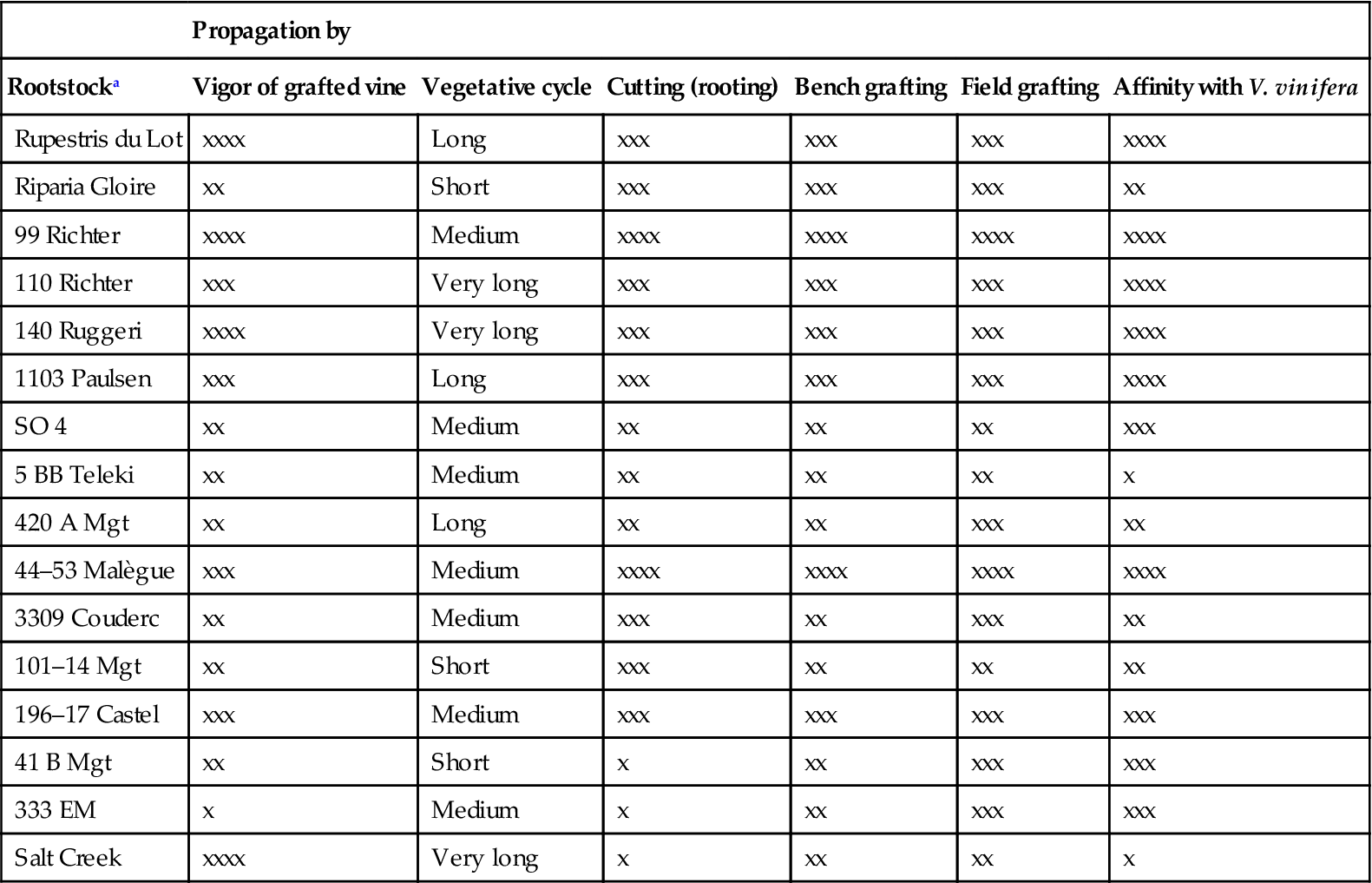

An old technique restricting vine vigor is hedging. However, the effect expresses itself slowly and risks inducing lateral bud activation and additional vegetative growth on fertile soils. Other vigor-limiting techniques include high-density planting (Table 4.4), the use of a ground cover (restricting root growth) (Hatch et al., 2011), or root pruning (Dry et al., 1998). However, permanent vigor restriction is achieved when a devigorating rootstock is used, for example 3309 Couderc, 420 A, 101-14 Mgt, and Gloire de Montpellier. In contrast, rootstock cultivars such as 99 Richter and 140 Ruggeri accentuate vine vigor (Table 4.6).

Table 4.6

Important Cultural Characteristics, other than Resistance to Phylloxera, of Commercially Cultivated Rootstocks

| Propagation by | ||||||

| Rootstocka | Vigor of grafted vine | Vegetative cycle | Cutting (rooting) | Bench grafting | Field grafting | Affinity with V. vinifera |

| Rupestris du Lot | xxxx | Long | xxx | xxx | xxx | xxxx |

| Riparia Gloire | xx | Short | xxx | xxx | xxx | xx |

| 99 Richter | xxxx | Medium | xxxx | xxxx | xxxx | xxxx |

| 110 Richter | xxx | Very long | xxx | xxx | xxx | xxxx |

| 140 Ruggeri | xxxx | Very long | xxx | xxx | xxx | xxxx |

| 1103 Paulsen | xxx | Long | xxx | xxx | xxx | xxxx |

| SO 4 | xx | Medium | xx | xx | xx | xxx |

| 5 BB Teleki | xx | Medium | xx | xx | xx | x |

| 420 A Mgt | xx | Long | xx | xx | xxx | xx |

| 44–53 Malègue | xxx | Medium | xxxx | xxxx | xxxx | xxxx |

| 3309 Couderc | xx | Medium | xxx | xx | xxx | xx |

| 101–14 Mgt | xx | Short | xxx | xx | xx | xx |

| 196–17 Castel | xxx | Medium | xxx | xxx | xxx | xxx |

| 41 B Mgt | xx | Short | x | xx | xxx | xxx |

| 333 EM | x | Medium | x | xx | xxx | xxx |

| Salt Creek | xxxx | Very long | x | xx | xx | x |

aRootstocks that have proved insufficiently resistant to phylloxera, and for this reason abandoned nearly everywhere (e.g., 1202 C, ARG, and 1613 C), are not included.

Source: From Pongrácz (1983), reproduced by permission. Summarized from data of Branas (1974), Boubals (1954, 1980), Cosmo et al. (1958), Galet (1971,1979), Mottard et al. (1963), Pàstena (1972), Pongrácz (1978), and Ribérau-Gayon and Peynaud (1971).

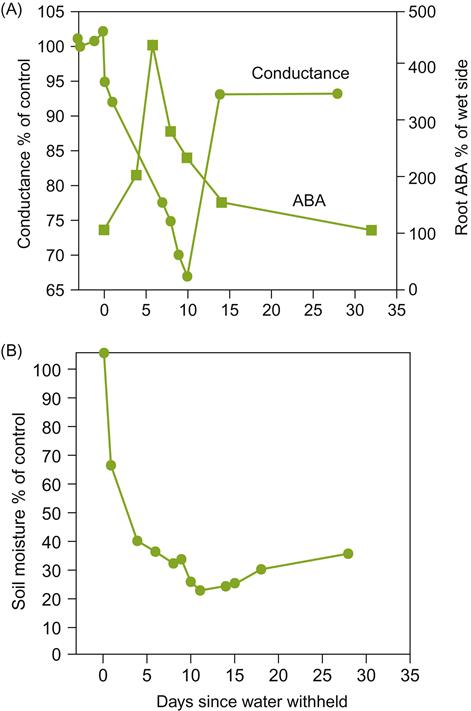

Additional measures employed to restrain vigor may involve restricting nitrogen fertilization and irrigation. Limiting fertilization, notably nitrogen, tends to minimize vegetative growth, as does limited water deficit. For example, shoot growth can terminate more than 1 month early under water deficit conditions (Matthews et al., 1987). This is of particular value as it has its most pronounced effect on lateral shoots (Williams and Matthews, 1990). Divided-canopy systems (with their increased transpiration) can have a similar effect by generating a mild water deficit. Where applicable, a trailing growth habit can also retard shoot elongation and restrain lateral shoot initiation.

Although soil type can indirectly affect vine vigor, choosing soil type is an option only when selecting a vineyard site. For example, restricted access to water and nutrients on stony to sandy soils limits vegetative vigor.

Another alternative involves the application of growth regulators, such as ethephon and paclobutrazol. Although effective, they may have undesirable secondary effects; for example, ethephon reduces photosynthesis (Shoseyov, 1983).

Ideally, devigoration should be obtained by directing any potential for excessive vegetative growth into additional fruit production and improved grape quality. For example, increased fruit yield, associated with higher bud retention in divided-canopy and minimal-pruning systems limits vegetative growth. As long as a favorable canopy microclimate is developed, the increased fruit load has a good chance of maturing fully, without adversely affecting subsequent fruitfulness or vine life span. However, the use of mechanical pruning must be initially carefully watched. There is the possibility that weaker vines may be permitted to repeatedly overproduce. This can lead to extensive reserve loss, leading to vine death (Miller et al., 1993).

Rootstock

The initial rationale for grafting was to control the destruction being caused by phylloxera. Although still the principal reason for grafting, rootstocks can also limit the damage caused by other soil factors. In addition, rootstock choice can modify scion attributes. Thus, rootstock selection offers the grower an opportunity to modulate varietal traits, without genetically modifying the scion. The significance of this underestimated potential is becoming more apparent as our understanding of the significance of the root system in regulating the shoot system increases. In addition to hormonal ‘cross-talk,’ the root system can participate in mobilizing defenses against foliar pest and pathogen attack (Erb et al., 2009).

One of the complexities in grafting has been the difficulty in predicting how its two components will interact. It presumably is based on the mutual exchange of nutrients and growth regulators. A clear example is how different rootstocks affect scion vigor. However, the influence is also bilateral, with scion traits influencing rootstock vigor (Tandonnet et al., 2010). The method used in this study was particularly intriguing, involving grafting to two different rootstocks. More subtle examples include induced phylloxera leaf galling in scions grafted to rootstocks susceptible to leaf galling (Wapshere and Helm, 1987), and a reduction in rootstock sensitivity to lime-induced chlorosis when grafted to particular scions (Pouget, 1987). In the latter instance, citric acid translocated to the roots enhances the formation of ferric citrate. This in turn facilitates transport of iron up to the leaves. Budbreak has also been correlated with cytokinin content in the sap from different rootstocks (Smith and Holzapfel, 2002).

Because climatic and soil conditions can modify expression of both rootstock and scion traits, their interaction can vary from year to year and location to location. Thus, although general trends are noted in Tables 4.6 and 4.7 (see also Howell, 1987; Ludvigsen, 1999; Anonymous, 2003), the applicability of particular rootstocks with specific scions must be assessed empirically, and ideally in consultation with the experience of local growers and viticultural specialists.

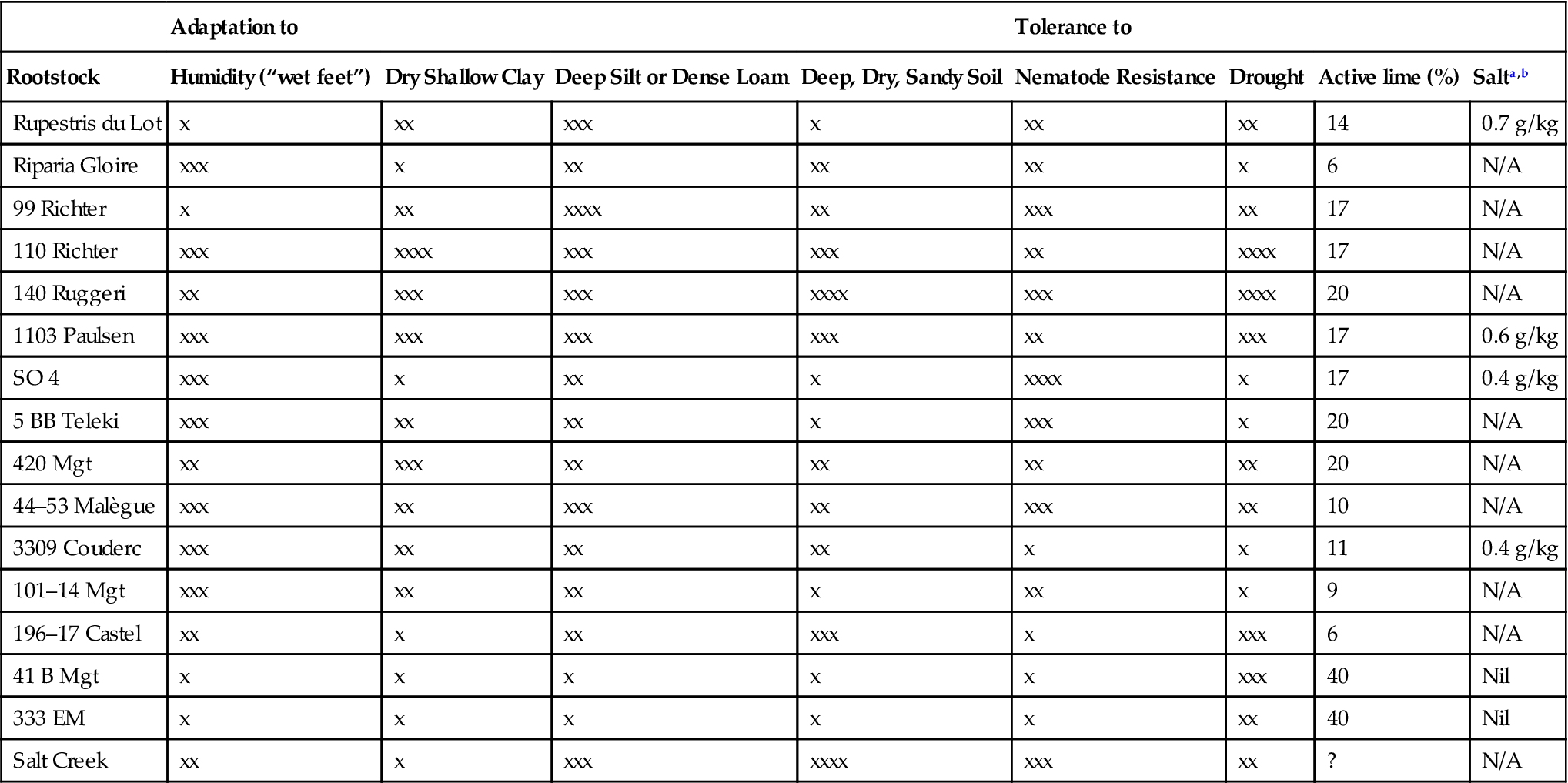

Table 4.7

Important Cultural Characteristics of Commercially Cultivated Rootstocks

| Adaptation to | Tolerance to | |||||||

| Rootstock | Humidity (“wet feet”) | Dry Shallow Clay | Deep Silt or Dense Loam | Deep, Dry, Sandy Soil | Nematode Resistance | Drought | Active lime (%) | Salta,b |

| Rupestris du Lot | x | xx | xxx | x | xx | xx | 14 | 0.7 g/kg |

| Riparia Gloire | xxx | x | xx | xx | xx | x | 6 | N/A |

| 99 Richter | x | xx | xxxx | xx | xxx | xx | 17 | N/A |

| 110 Richter | xxx | xxxx | xxx | xxx | xx | xxxx | 17 | N/A |

| 140 Ruggeri | xx | xxx | xxx | xxxx | xxx | xxxx | 20 | N/A |

| 1103 Paulsen | xxx | xxx | xxx | xxx | xx | xxx | 17 | 0.6 g/kg |

| SO 4 | xxx | x | xx | x | xxxx | x | 17 | 0.4 g/kg |

| 5 BB Teleki | xxx | xx | xx | x | xxx | x | 20 | N/A |

| 420 Mgt | xx | xxx | xx | xx | xx | xx | 20 | N/A |

| 44–53 Malègue | xxx | xx | xxx | xx | xxx | xx | 10 | N/A |

| 3309 Couderc | xxx | xx | xx | xx | x | x | 11 | 0.4 g/kg |

| 101–14 Mgt | xxx | xx | xx | x | xx | x | 9 | N/A |

| 196–17 Castel | xx | x | xx | xxx | x | xxx | 6 | N/A |

| 41 B Mgt | x | x | x | x | x | xxx | 40 | Nil |

| 333 EM | x | x | x | x | x | xx | 40 | Nil |

| Salt Creek | xx | x | xxx | xxxx | xxx | xx | ? | N/A |

aApproximate levels of tolerance are as follows: American species, 1.5 g/kg absolute maximum; V. vinifera, 3 g/kg absolute maximum.

bnot available.

Source: From Pongrácz (1983), reproduced by permission. Summarized from data of Branas (1974), Cosmo et al. (1958), Galet (1971), Mottard et al. (1963), Pàstena (1972), Pongrácz (1978), and Ribéreau-Gayon and Peynaud (1971).

In selecting a rootstock, ranking desired properties is necessary as each rootstock has both advantages and disadvantages. Selection cannot be taken lightly. Once a rootstock has been chosen, it remains a permanent component until vineyard replanting.

The most basic criterion for acceptability is compatibility between the components. Compatibility refers to the formation of a stable graft union. Early and complete fusion of the adjoining cambial tissues is critical to effective translocation between the rootstock and scion. Areas that do not join shortly after grafting never fuse. Such gaps leave weak points, providing potential sites for the invasion of pests and disease-causing agents. Recommendations on cultivar compatibility are given in Furkaliev (1999).

For many rootstock varieties, data are available on basic properties (see Table 4.6). Views from a variety of countries are presented in Wolpert et al. (1992), and are usually available from regional specialists. In many regions, desirable rootstock combinations that match local cultivars and conditions have already been established. However, for new scion–rootstock combinations, or in new viticultural regions, existing data can only provide a guide as to what appears justifiable for field trials.

Because of the large number of rootstock–scion combinations, there has been a desire to predict unsuitable combinations. Although the parentage of a rootstock gives hints as to relative compatibility, accurate prognostication remains illusive. Whether compatibility can be determined using electrophoretic similarity between potential matches, as suggested by Masa (1989) and Gökbayrak et al. (2007), remains contentious.

Although incompatibility may originate from unexplained physiological disparities between the components, poor union between otherwise compatible pairs may be caused by pathogens. Grafting healthy scions to rootstock infected with GLRaV-2, RSPaV, and fleck viruses can result in a poor union. This is often expressed as a swelling at the graft site or in xylem disruption (Golino, 1993). The presence of several fungi has also been associated with graft failure, notably Phaeoacremonium parasiticum (often associated with Petri disease) and Botryosphaeria spp. (causal agents of several Diplodia diseases).

In rootstock trials conducted in the late 1800s, the most successful selections were from V. riparia, V. rupestris, crosses between these two, or V. cinerea var. helleri (V. berlandieri). Their progeny still constitute the bulk of rootstock cultivars (Howell, 1987). Subsequently, breeding has incorporated traits from species such as V. vinifera, V. mustangensis (V. candicans), and V. rotundifolia.

In regions where phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae) is now established, grafting V. vinifera cultivars to resistant rootstock is standard. Even where phylloxera is not present, serious consideration should be given to its use. If past history is any indication, it is only a matter of time before the presence of phylloxera in vineyards will be universal.

The existence of several D. vitifoliae biotypes, along with the presence of differential tissue sensitivity in various grapevine species, indicates that phylloxera resistance is complex (Wapshere and Helm, 1987). Phylloxera biotypes often are distinguished on the basis of their rates of multiplication on particular (tester) rootstocks. For example, biotype B phylloxera multiplies twice as rapidly as biotype A on A×R#1 (Ganzin 1) (Granett et al., 1987). When A×R#1 became the predominant rootstock in much of northern California, the eventual occurrence of a biotype capable of multiplying on this rootstock was probably inevitable. Although most commercial rootstock cultivars derived from V. riparia, V. rupestris, or V. cinerea var. helleri (V. berlandieri) possess some phylloxera resistance, additional potential sources of resistance are V. rotundifolia, V. mustangensis (V. candicans), V. cinerea, and V. vulpina (V. cordifolia).

Although phylloxera resistance is the prime reason for most rootstock grafting, nematode resistance is more significant in some regions. Grapevine roots may be attacked by several pathogenic nematodes, but the most important are root-knot (Meloidogyne spp.) and dagger (Xiphinema spp.) nematodes. Dagger nematodes are also transmitters of fanleaf degeneration. Because V. rotundifolia is particularly resistant to fanleaf degeneration as well as nematode damage, it has been used in breeding several new rootstocks, notably VR O39-16 and VR O43-43 (Walker et al., 1994). Regrettably, lime-susceptibility and sensitivity to phylloxera limit the use of VR 043-43 to noncalcareous soils and regions devoid of phylloxera. Another valuable source of nematode resistance is V. vulpina. Some of its resistance genes have been incorporated into varieties such as Salt Creek (Ramsey), Freedom, and possibly 1613 C.

Soil factors can significantly influence rootstock choice. For example, tolerance to high levels of active lime (CaCO3) is essential throughout much of Europe. There, varieties such as Fercal or 41 B are preferred. In contrast, low sensitivity to aluminum is crucial in some acidic Australian, South African, and Brazilian soils. Secretion of citric acid by the rootstock may donate aluminum tolerance (Cançado et al., 2009). Because of the importance of soil factors, most commercial rootstocks have been studied to determine their tolerance to such factors (see Table 4.7). Where conditions vary considerably within a single vineyard, the use of several rootstocks may be required.

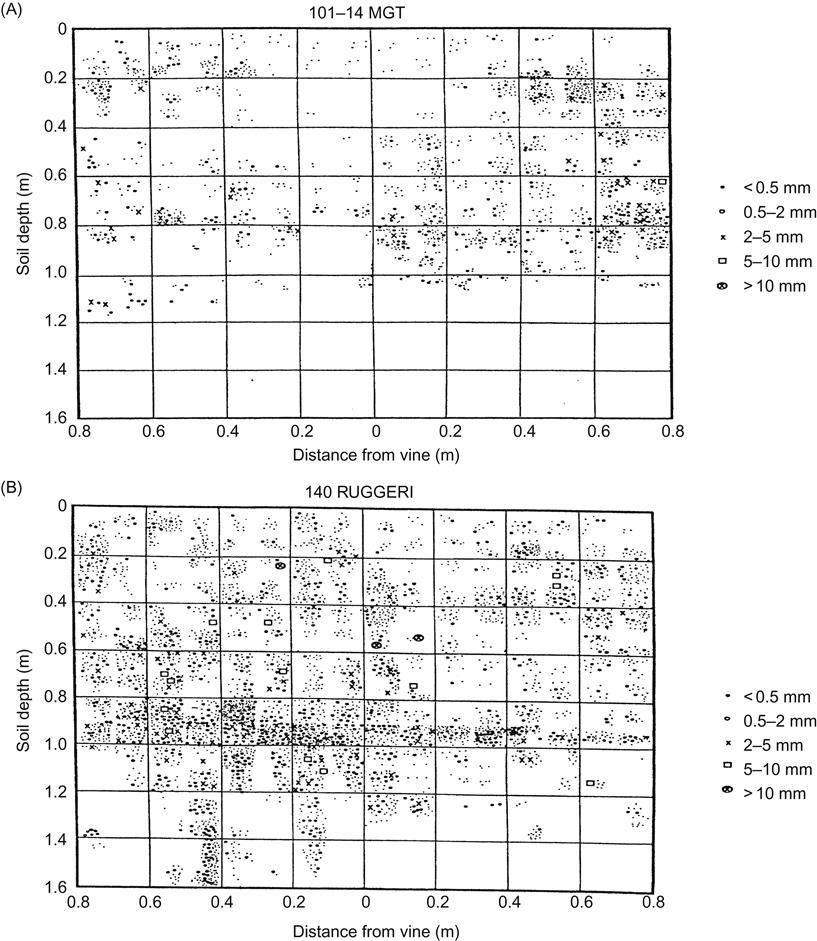

Drought tolerance can be another factor crucial in rootstock selection, especially in arid regions where irrigation is limited, unavailable, or not permitted. As with most traits, drought tolerance is based on complex physiological, developmental, and anatomical properties. Differences in root depth, distribution, and density appear to be partially involved (Fig. 4.25). Several drought-tolerant varieties reduce stomatal conductance in the scion. In addition, 110 Richter may induce the production of fewer and smaller stomata (Scienza and Boselli, 1981; Düzenli and Ergenoğlu, 1991). However, some rootstock varieties have their benefits without affecting scion transpiration efficiency (Virgona et al., 2003). The merits of using a drought-tolerant rootstock may be even more valuable under conditions that restrict root growth, such as high-density plantings.

Although V. cinerea var. helleri is one of the most drought-tolerant grapevine species, expression of the trait varies considerably in V. cinerea var. helleri-based rootstocks. Vitis vulpina-based rootstocks are often particularly useful on shallow soils in drought situations.

In regions having short growing seasons, early fruit ripening and cane maturation are essential. Most rootstocks that favor early maturity have V. riparia in their parentage. Where yearly variation in cold severity is marked, random grafting of vines to more than one rootstock may provide some protection against climatic vicissitudes (Hubáčková and Hubáček, 1984).

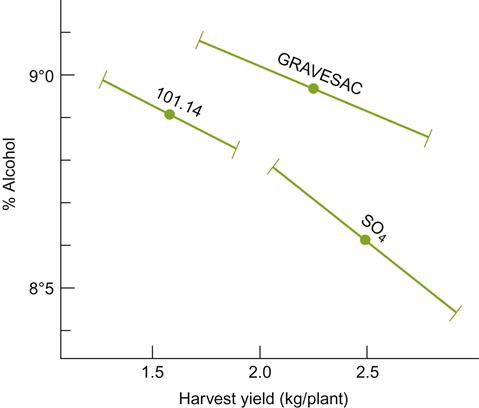

Another vital factor influencing rootstock selection is its effect on grapevine yield. Although the rapid establishment of a vineyard is aided by vigorous vegetative growth, this property may be undesirable in the long term. Thus, rootstocks may be chosen to induce devigoration. This property of 3309 C has made it particularly popular under dryland viticultural conditions. Devigorating rootstocks usually not only restrict yield and favor improved fruit quality, but also limit expression of physiological disorders such as inflorescence and bunch-stem necrosis. Fruit yield generally shows a weak negative correlation with quality, as measured by sugar content (see Fig. 3.54). The specific yield vs. quality influence of any rootstock can vary considerably (Fig. 4.26), depending on vineyard layout and canopy management, as well as irrigation (Whiting, 1988; Foott et al., 1989).

Some of the effects on vine vigor and fruit quality may accrue from differential nutrient uptake. For example, preferential accumulation of potassium can antagonize the uptake of other cations. For rootstocks such as SO 4 and 44–53 M this can lead to magnesium deficiency (Boulay, 1982). Limited zinc uptake by Rupestris St. George may be a source of poor fruit set in the scion (Skinner et al., 1988). Because stored nitrogen (much of it in the root) supplies most of the nitrogen required for early growth (Conradie, 1988), variation in rootstock nitrogen uptake and storage may influence scion fruitfulness. The importance of rootstock selection in limiting lime-induced chlorosis has already been mentioned. Although most of these effects are undoubtedly under the direct control of the rootstock, some variation may result indirectly from differential mycorrhizal colonization. Thus, where grafted vines are planted in fumigated soils, it is recommended that the rootstock be inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi prior to planting (Linderman and Davis, 2001).

Rootstock selection can also influence scion fruit composition. By affecting berry size, the rootstock can influence the skin/flesh ratio and, thereby, wine attributes. Additional indirect effects on fruit composition may result from increased vegetative growth, augmenting leaf–fruit competition and shading. For example, the use of Ramsey for root-knot nematode control and drought tolerance in Australia has inadvertently increased problems associated with excessive vine vigor. Nevertheless, other rootstock effects are probably more direct, via differential mineral uptake from the soil (see Fig. 4.42). The rootstock’s impact on potassium uptake (Ruhl, 1989) and its accumulation in the vine (Failla et al., 1990) can be especially important. Potassium distribution affects not only growth, but also juice pH and potential wine quality. Rootstock modifications of fruit amino acid content have been correlated with the rate of juice fermentation (Huang and Ough, 1989). Thus, rootstock choice can be a long-term component of the arsenal a grape grower may use to influence fruit quality (Kodur et al., 2010).

Few studies have investigated the significance of rootstock on grape aroma. As an indication of the complexity of such a relationship, some studies have shown a decrease in monoterpene content, associated with rootstocks promoting high yield (McCarthy and Nicholas, 1989), whereas others have found little correlation, with changes in yield of up to 250% (Whiting and Noon, 1993).

Although rootstock grafting can be a valuable, if not an essential, component of vineyard management, it is expensive. In addition, the cost of special rootstocks may be higher, owing to limited demand or propagation difficulties. These features can also make them difficult to obtain. Nevertheless, the long-term benefits of using the most suitable rootstock usually outweigh the additional expenditure associated with their procurement.

One of the unanticipated problems occasionally associated with rootstock use has been that of errors in identification. Many of the cultivars are morphologically similar, making amphelographic recognition difficult. This should become less frequent due to the introduction of genomic fingerprinting (Guerra and Meredith, 1995).

A regrettable consequence of grafting has probably been the surreptitious spread of many grapevine viruses and viroids around the world (Szychowski et al., 1988). Identification of viruses, as an agent of plant disease, occurred long after the global dispersal of rootstocks. Graft unions may also act as pest invasion sites. Nevertheless, the grafting procedure itself can apparently induce, at least temporarily, resistance to infection and transmission of tomato ringspot virus (Stobbs et al., 1988).

In the popular press, romantic musing over the presumed superior quality of prephylloxera wines has been frequent. In most situations, the question is purely academic. Grape culture in many parts of the world would be commercially nonviable without grafting. As in other aspects of grape production, choice of a rootstock can either enhance or diminish grape and wine quality. In addition, regions or sites where grafting is still unnecessary are not uniquely renowned for the excellence of their wines.

Vine Propagation and Grafting

Grapevines are propagated by vegetative means to retain their unique genetic constitution. Sexual reproduction, by rearranging genetic traits, disrupts desirable gene combinations. Thus, seed propagation is limited to breeding cultivars, where new genetic arrangements are desired.

Several techniques may be used to vegetatively propagate grapevines. The method depends on pragmatic matters, such as the number of plants required, the rapidity of multiplication, when propagation is conducted, whether grafting is involved, and, if so, the thickness of the trunk. Regardless of the method, some degree of callus formation occurs.

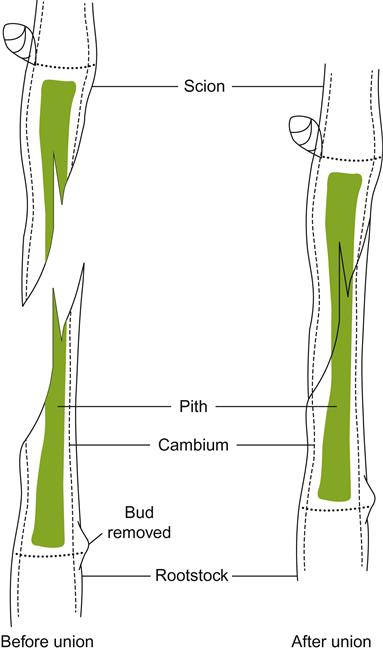

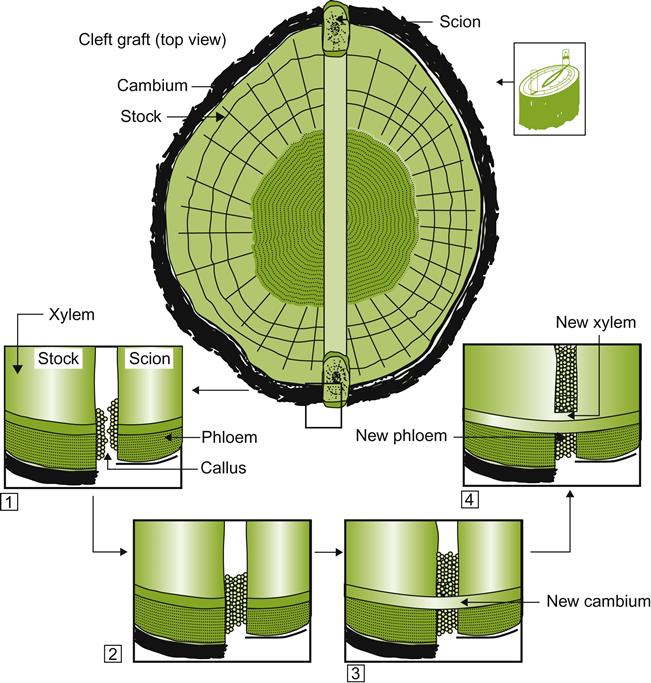

Callus tissue consists of undifferentiated cells that develop in response to physical damage. Callus cells develop most prominently in and around meristematic tissues. In grafting, this initiates around the cambium. It is the callus tissue that establishes the union between the adjacent vascular and cortical tissues of the rootstock and scion (Fig. 4.27). For the union to persist, it is critical that the thin cambial layer of both rootstock and scion be aligned next to one another. Callus formation also is associated with, but not directly involved in, the formation of roots from cuttings. New (adventitious) roots typically develop from or near cambial cells between the vascular bundles of the cane. Most roots emanate from a region adjacent to the basal node of the cutting. Finally, callus cells that develop in tissue culture may differentiate into shoot and root meristems, from which whole plants may develop (Plate 2.5).

Callus tissue formation, being metabolically active, is favored by warm conditions and ample oxygen. Because of the undifferentiated state of the tissue, its thin-walled cells are very sensitive to drying and sun exposure. Correspondingly, the union is covered by grafting tape until protective layers have formed over the graft site.

Multiplication Procedures

The simplest, and presumably oldest, propagation technique is layering. It involves bending a cane down and mounding soil over the section. Once rooted sufficiently, connection to the parent plant can be severed. Layering has the advantage that water and nutrients are available from the parent throughout root formation and development. This is particularly useful with difficult-to-root vines, such as muscadine cultivars. Other than for this reason, layering is seldom used today. Other techniques are often as effective, easier to commercialize, and do not interfere with viticultural practices, such as cultivation and weed control.

Grapevine propagation typically involves cane cuttings. Cane sections are usually selected from prunings collected during the winter. The best sections tend to be 8–13 mm in diameter, uniformly brown, and possess internode lengths typical of the variety. These features indicate that cane development occurred under favorable conditions and is well matured. If the section is to be self-rooted, or is designed to be a rootstock, the sections need to be about 35–45 cm in length. This is sufficiently long to supply the new root and shoot system with ample nutrients, until the section has developed adequately to be self-sufficient. Cane length may also depend on the water retention properties of the soil into which the vine is to be planted, and/or the availability of irrigation water subsequent to planting. Soaking the sections in a disinfectant for a few minutes, such as 8-hydroxyquinoline sulfate, guards against infection from pathogens such as Botrytis cinerea. If deemed necessary, submersion in hot (50–55°C) water can inactivate some pests, such as nematodes, and several contaminant or systemic fungal and bacterial pathogens.

A lower perpendicular cut is made just below a node, and an upper 45°diagonal cut made about 20–25 mm above the uppermost bud. The diagonal cut facilitates rapid identification of the apical direction. This is important because the original apical–basal orientation of the cutting must be retained when rooted. Cane polarity restricts root initiation to the basal region of the cutting. In addition, the diagonal section provides some physical protection for the terminal bud. Protecting this bud is especially important in rootstock varieties. In this case, all buds except the terminal one are removed before rooting to limit subsequent rootstock suckering. Its presence is essential as the sole source of auxin activating root development.

If grafted cuttings are to be rooted directly into a vineyard, it is important to leave about 10 cm of the cane above ground. This minimizes the likelihood of scion rooting. If scion rooting were to occur, its roots might outgrow those of the rootstock, only to succumb to the conditions for which grafting was conducted.

The canes of most V. vinifera varieties root easily. The same is also the case for most rootstock cultivars that are selections of V. rupestris and V. riparia, hybrids between them, or hybrids with V. vinifera. Most rootstocks containing V. cinerea var. cinerea, V. cinerea var. helleri, V. mustangensis, V. vulpina, or V. rotundifolia heritage are, to varying degrees, difficult to root (see Table 4.6). The most effective activators include soaking in water for 24 hours; dipping in a solution of about 2000 ppm indolebutyric acid (IBA); applying bottom heat (25–30°C) to the rooting bed; and periodic misting to maintain high humidity. Additional factors of potential value have involved spraying parental vines with chlormequat chloride (CCC) in spring prior to cane selection (Fabbri et al., 1986), and aquaculturing after callus formation (Williams and Antcliff, 1984).

Rooting canes of V. aestivalis cultivars, such as Norton, also pose difficulties. To improve success, Keeley et al. (2004) recommend, in addition to the standard procedures noted above, that cuttings be chilled (≤7°C) for at least 2300 h, be taken from basal and middle portions of canes, and treated with five times the normal amount of IBA.

Rooting success with V. vinifera is best when sections are rooted directly after harvesting. If rooting is to be delayed, the cuttings should be stored in a refrigerated (1–5°C), moist, mold-free environment. Upright storage in moist sand or sawdust is common. During this period, a basal callus forms. It is from this callus that roots develop.

An alternative rapid, propagation procedure involves green cuttings. These are single-node pieces cut from growing shoots. Rooting occurs under mist propagation in a greenhouse. It is particularly useful when source material is scarce. The procedure is also valuable for cultivars that do not root well from cane wood, notably Vitis cinerea var. helleri (V. berlandieri) and V. rotundifolia. The technique is more complex and demanding, both in equipment and protection, after rooting. In addition, the tender nature of green cuttings requires considerable caution in hardening the rooted plants to withstand vineyard conditions.

Although rooting cane sections is the most common means of grapevine propagation, it may be inadequate for the rapid multiplication of speciality stock. Micropropagation from axillary buds is the simplest tissue culture method. In some instances, as with Vitis×Muscadinia crosses, it may be the only convenient method (Torregrosa and Bouquet, 1996). If the financial incentive is adequate, vines can be multiplied even more quickly using shoot–apex fragmentation (Barlass and Skene, 1978) and somatic embryogenesis (Reustle et al., 1995; Zhu et al., 1997).

More complex and demanding than other reproduction techniques, tissue culture is the only means of mass propagating a cultivar. Regrettably, micropropagation is complicated by the need to adjust the procedure, relative to the cultivar and tissue (Martinelli et al., 1996). However, because strict sanitation is required, infection of disease-free stock is avoided.

Grafting

Where conditions obviate the need for grafting, self-rooted scion cuttings are often directly planted in the vineyard. However, in most viticultural sites, profitable grape cultivation requires grafting to a suitable rootstock. This typically involves inserting one-bud scion sections to the apex of a rootstock. When done indoors, as in a nursery or greenhouse, it is referred to as bench grafting. When grafting occurs at or shortly following planting in the vineyard, it is termed field grafting. The other major use of grafting is converting (topworking, grafting over) existing vines to another fruiting variety. When the scion piece consists of a cane segment, the process is called grafting, to distinguish it from the use of small side pieces of a cane, designated as budding.

Bench grafting has the advantage of being amenable to mechanized mass production. It can also be performed over a longer period, as it commonly uses dormant cuttings. To facilitate proper cambial alignment, it is necessary to presort the rootstock and scion pieces by size. After making the cuts, and joining the two sections (Fig. 4.28), the grafted cutting is placed in a callusing room under moist warm conditions. This favors rapid callus development and graft union. Grafting machines permit junctions of sufficient strength that grafting tape is not needed. If the grafted rootstock has already been rooted, the vine is ready for planting shortly after the union has formed, and the exposed callus has been hardened off and coated with wax. If an unrooted, but difficult-to-root dormant rootstock is used, the base may be treated with IBA and placed in a heated rooting bed, while the upper graft union is kept cool. This favors root development before the scion bud bursts, placing unsustainable water demands on the rootstock. With easily rooted rootstock, canes usually root sufficiently rapidly to supply the needs of the developing scion without special treatment.

Occasionally, actively growing shoots are grafted directly onto rootstocks in a process termed green grafting. Graft union is usually rapid and highly successful. With distantly related Vitis species, it reduces incompatibility problems that otherwise might plague successful graft union (Bouquet and Hevin, 1978). In most cases, though, the higher labor costs and more demanding environmental controls usually do not warrant its use. Nevertheless, technical advances are reducing the expense of green grafting (Pathirana and McKenzie, 2005).

Where labor and timing are appropriate, field grafting is the most economic grafting procedure. Preferably, it should occur shortly after growth has commenced in the spring. At this time, the cambia of both rootstock and scion piece are active, and the graft union can develop rapidly. This also favors prompt scion bud activation. The rootstock section is planted with about 8–13 cm projecting above the ground. This discourages adventitious root development from the scion section, and places the root system sufficiently deep to minimize damage during manual weeding. Grafting unrooted rootstock in the field is not recommended due to its poor success rate.

Commonly used manual grafting techniques include whip grafting and chip budding. Whip grafting requires scion and rootstock canes of equivalent diameter (Fig. 4.29). Two cuts are made about 5 mm above and below a scion bud. The upper cut is shallowly angled and directed away from the bud to identify scion polarity. The lower cut is long and steep (15–25°), usually 2.5 times longer than the diameter of the cane. A ‘tongue’ is produced in the lower cut by making an upward slice and gently pressing outward away from the bud with the pruning knife. An inverse set of cuts is made in the rootstock to receive the scion. After connection and alignment, the union is secured with grafting tape, raffia, or other appropriate material. Plastic grafting tape is popular because it is both quickly and easily applied, will not cause girdling, and helps limit drying at the graft union.

Whip grafting provides an extensive area over which the union can establish itself. Its main disadvantage is the skill and time required in performing the procedure. In addition, the juncture produces a large potential invasion site for a complex of wood decay fungi. Over many years, these could weaken the trunk and cause progressive yield decline.

Chip budding provides less union surface than whip grafting, but the smaller scion piece demands less contact area. Chip budding is often preferred because it requires less skill in preparing matching cuts. Also, because the scion source does not need to be identical in diameter to the rootstock, time is saved by avoiding matching scion and rootstock segments.

In chip budding, two oblique downward cuts are made above and below the scion bud (Fig. 4.30). The upper cut is more acute and meets the lower incision, making a wedge-shaped chip about 12 mm long and 3 mm deep at the base. A matching section is cut out, about 8–13 cm above ground level on the rootstock. The chip is held in position with grafting tape or equivalent material.

With either grafting technique, it is imperative that each set of cuts, and insertion of the scion piece, be performed rapidly to avoid drying. Drying of the cut surfaces dramatically reduces the likelihood of successful union.

Various techniques are used in converting (topworking) existing vines to another fruit-bearing cultivar. For trunks less than 2 cm in diameter, whip grafting is commonly used, whereas for trunks between 2 and 4 cm in diameter, side-whip grafting is often preferred. Trunks more than 4 cm in diameter may be notch-, wedge-, cleft- or bark-grafted (Alley, 1975). In all size classes, chip budding can be used, whereas T-budding is largely limited to trunks more than 4 cm in diameter. Budding techniques are often preferred to the use of larger scion pieces. They require less skill and can be as successful (Steinhauer et al., 1980). Conversion high on a trunk allows most of the existing trunk to be retained, thus speeding the vine’s return to full productivity.

T-budding derives its name from the shape of the two cuts produced in the vine being converted. After making the cuts, the bark is pulled back to form two flaps. This generates a gap into which the scion piece (bud shield) is slid. The bud shield is produced by making a shallow downward cut behind the bud on the source material. The slice begins and ends about 2 cm above and below a bud. A second oblique incision below the bud liberates the bud shield. To facilitate better union, Alley and Koyama (1981) recommend that T-cuts in the trunk be inverted. In the inverted-T graft (Fig. 4.31), the rounded upper end of the bud shield is pushed upward and the bark flaps cover the bud shield. In the original version of the technique, failure of the top of the shield to join well with the trunk created a critical weakness zone. Wind could easily split the growing shoot from the trunk, requiring shoots to be tied to a support shortly after emergence. This occurrence is much less likely with inverted T-budding.

Depending on trunk diameter, several bud shields may be grafted around the trunk. The shoots so derived are necessary to provide sufficient photosynthate for the trunk and root system. Each bud shield is grafted at the same height to conserve grafting tape, speed grafting, but primarily to avoid apical dominance.

T-budding has the advantage of requiring the least skill of any vine conversion technique. In addition, demands on cold storage space are minimized. Bud shields rather than cuttings need only be stored (Gargiulo, 1983). Nonetheless, it has the disadvantage of the short period during which it can be performed. The grape grower must wait until the bark can be easily separated from the wood to permit insertion of the bud shield (shortly after budbreak). Postponing T-budding much beyond this point delays budbreak and may result in poor shoot maturation by autumn.

In contrast, chip budding can be performed earlier, thereby allowing the grape grower greater flexibility in timing budding-over. With chip budding, it is necessary to use a section of the trunk with a curvature similar to that of the chip. Otherwise, the cambial alignment may be inadequate and the union may fail. Depending on trunk thickness, two or more buds are grafted per vine. Because of the hardness of the wood, cutting out slots for chip budding is more difficult than for T-budding. Nevertheless, the longer period over which chip budding can be performed may make it preferable. The success rate of chip budding is usually equivalent to T-budding (Alley and Koyama, 1980).

Although vine conversion is usually performed in the spring, this has the disadvantage of losing the full year’s crop. It is necessary to remove the existing top to permit the newly grafted scion pieces to develop into the new top. To offset this loss, chip budding may be performed in early autumn, when the buds have matured but weather conditions are still favorable (≥15°C) (Nicholson, 1990). Full union is usually complete by leaf fall, the buds remaining dormant until spring. Angling the upper and lower cuts away from the bud produces a bud chip that slides into a matching slot made in the host vine. Although the technique is more complex, interlocking assures a firm connection with the vine. Grafting tape protects the graft site from drying. In the spring, the tape is cut to permit the bud to sprout. An encircling incision above the grafted buds stimulates early budbreak while restraining growth of the existing top. This technique allows the vine to bear a crop while the grafted scion establishes itself. At the end of the season, the existing top is removed and the grafted cultivar trained as desired.

The older techniques of cleft, notch, and bark grafting are still used, but less frequently. Not only do the older techniques require more skill in cutting and aligning the scion and trunk cambia, but they also take longer and require grafting compound to protect the graft while the union forms. Readers desiring details on these and other grafting techniques are directed to standard references (e.g., Winkler et al., 1974; Alley, 1975; Weaver, 1976; Alley and Koyama, 1980, 1981).

Despite the advantages of grafting, the process has its disadvantages. It definitely increases the cost of establishing a vineyard, as well as facilitates pathogen invasion. This not only involves pathogens entering via the graft site, but also their transfer from infected rootstocks to scions. Additional problems arise from rootstock/scion incompatibility and other forms of disruption at the graft site. An example is reduced hydraulic conductivity leading to a lack in vine vigor. That this is strictly a consequence of the grafting procedure is evidenced by its occurrence in self-grafted vines (Bavaresco and Lovisolo, 2000).

Soil Preparation

Ideally, the soil should first be analyzed and prepared to receive vines. The degree of preparation required depends on the soil’s texture, degree of compaction, previous usage, drainage conditions, any nutrient deficiencies or toxicities, pH, irrigation needs, and endemic diseases and pests. If the land is virgin, noxious perennial weeds and rodents should be eliminated, as much as feasible, and obstacles to efficient cultivation removed. Where the soil has already been cultivated, providing sufficient drainage and soil loosening for excellent root development are the primary concerns. The effects of soil characteristics on root distribution are illustrated in Plates 4.9, 4.10, 4.11, and 4.12.

Where soil conditions are unfavorable to root development (e.g., acidic, saline, sodic, waterlogged, nutrient deficient or toxic), local recommendations should be obtained from regional authorities. What may be possible will depend on a multiple of factors, including scion and rootstock genetics.

Inadequate drainage is most effectively improved by laying drainage tiles. Winkler et al. (1974) recommended draining soil to a depth of about 1.5 m in cool climates, and to 2 m in warm to hot climates. Narrow ditches are a substitute, but can complicate vineyard mechanization. In addition, ditches remove valuable vineyard land from production. Drainage efficiency may be further improved by correcting impediments to water percolation.

Deep ripping (0.3–1 m), used to break hardpans and improve percolation, also loosens deep soil layers. This is especially valuable in heavy, nonirrigated soils where enhanced soil access can minimize water deficit under drought conditions (van Huyssteen, 1988a). Ripping can also improve soil homogeneity, further favoring effective soil use (Saayman, 1982; van Huyssteen, 1990). Nevertheless, ripping can incorporate nutrient-poor, deep soil horizons into the topsoil, as well as enhance erosion on slopes. It may also create water flow channels in nonporous soils, requiring the installation of drainage at row ends to carry away the runoff (Smith, 2002). Ripping should be avoided when the soil is wet, as it can generate columns of compacted soil between the rows, complicating rather than improving drainage.

In sites possessing considerable heterogeneity, earth moving, leveling, and mixing may be advisable. This can minimize serious local variations in soil acidity, nutrient status, and water availability. These can lead to lack of fruit uniformity at harvest, a feature generally viewed as inimical to wine quality (Long, 1987; Bramley and Hamilton, 2004; Cortell et al., 2005).

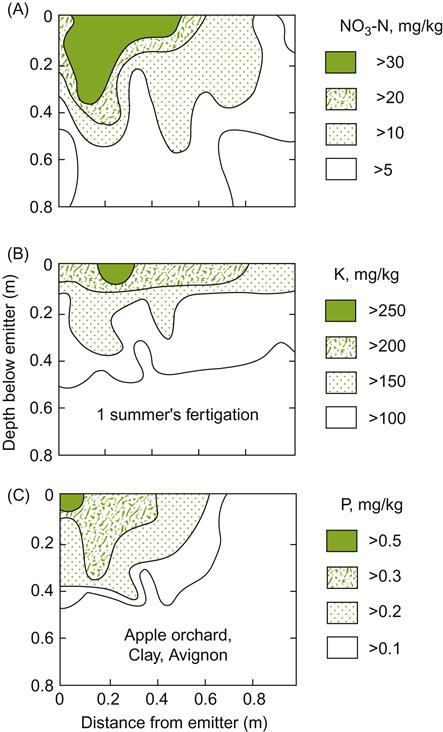

Where soils are deficient in poorly mobile nutrients, this is the optimum time to incorporate elements such as potassium and zinc. This is also the occasion to fumigate the soil, if nematodes are likely to be a problem, regardless of whether nematode-resistant rootstocks are used. Fumigation reduces the level of infestation and enhances the effectiveness of resistant or tolerant rootstocks in maintaining healthy vines.

Where surface (furrow) irrigation is desired, the land must be flat, or possess only a slight slope. Thus, land leveling may be required if this irrigation method is planned, and economically feasible.

Vineyard Planting and Establishment

Mechanized planting is favored both because of its time and cost savings. Where bare-rooted cutting are planted, it is critical to protect the plants from drying. Because roots are trimmed to the size of the planting hole, the opening should be sufficiently large to optimize root retention. Direct planting of rooted cuttings from tubes or pots is preferable because it maximizes root retention, but is more expensive. If sufficiently acclimated to field conditions, potted vines suffer minimal transplantation shock. This approach also gives the grape grower more flexibility in scheduling planting.

Where permanent stakes are not already in position, it is advisable to angle the planting hole away from the stake’s future location. This minimizes root damage from the use of posthole diggers and cultivators. Often, soil is hilled around the exposed portion of vine until shoot development is well established. Alternatively, planting may take place on mounds of earth covered by meter-wide sheets of black plastic or mulch pellets (Buckerfield and Webster, 1999b). These techniques promote root development and minimize the manual weeding normally required during the first year.

Proper hole preparation is important to assure adequate root development. Poor development can lead to restricted vine growth, not only in the first few years, but also later when fruit production increases demand on a confined system. Vertical root penetration promotes greater access to water in dry spells and provides better use of mobile nutrients such as nitrogen. Conversely, horizontal proliferation has the benefit of reaching poorly mobile nutrients such as phosphate.

When planting is conducted manually, Louw and van Huyssteen (1992) recommend square holes. Finishing with a garden fork produces uneven sides and loosens the bottom. Although beneficial, the expense of these measures must be weighed against the economy of automated planting systems.

Only soil of the same type and texture should be used to fill the hole. Lighter textured soil favors root confinement within the planting hole, rather than penetration into the surrounding soil. This not only favors a pot-bound effect, but increases the likelihood of water logging, poor soil aeration, and soil pathogen problems.

Roots tend to penetrate soil pores of a diameter equal to or greater than the diameter of the growing root tip. Thus, smearing moist soil, as with an auger, can seal off most soil cavities, resulting in roots restricted within a zone circumscribed by the planting hole. Thus, soil moisture conditions must be ideal for auger use.

With use of an automatic planting machine, or water lance (a jet of water that creates a hole), care should be taken to assure that air pockets do not remain below the roots. This is frequently corrected by a gentle downward push on the soil.