Site Selection and Climate

In vineyard development, site selection affects the range and quality of the types and styles of wine potentially generated. The chapter discusses both terrestrial and atmospheric conditions relative to grape production. Soil factors explored include its geologic origin, texture, structure, drainage and water availability properties, depth, fauna and flora, pH and nutrient contents, color, and organic content. Topographic influences covered include solar exposure, wind direction, altitude, and drainage. Atmospheric features explored include: climatic indicators; the major importance of the seasonal temperature regime; chilling and frost injury, and control; factors affecting solar exposure and its physiological effects; wind influences and its modulation; and seasonal precipitation patterns.

Keywords

vineyard; site selection; soil influences; topographic effects; atmospheric factors; chilling; frost injury

The view that vines need to ‘suffer’ to produce great wines is long established in wine folklore. However, if ‘stress’ is interpreted as restrained grapevine vigor, open-canopy development, and fruit yield consistent with capacity, the concept of vine suffering has more than just an element of truth. These factors have already been discussed in Chapter 4. Regions where local conditions inherently have imposed these features have come to be noted for their better-quality wines. In addition, vineyard practices that enhance these natural tendencies are well known. Nonetheless, sites may possess undesirable properties that viticultural practice cannot offset. These beneficial and detrimental aspects of soil, topography, microclimate, and macroclimate form the basis of avoiding such situations and choosing a favorable viticultural site. Assessing the properties of a site has recently been facilitated with advances in both on-site and remote sensing (e.g., Bramley et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2010). This knowledge allows grape growers not only to produce better-quality grapes in traditional wine-producing regions, but also to rationally expand production into new viticultural areas.

It is a natural tendency to assume that modern science has made great strides in assessing which site properties are most appropriate for grape cultivation, and indeed it has. Nonetheless, it is humbling to read Columella’s (4–70 AD) De Re Rustica (3.1). His counsel is cogent, empirical, and surprisingly modern. Even subtleties such as varietal selection for moist, disease prone climates and comments on the advantages of basal leaf removal are clearly enunciated. Scientist he was not; a very astute observer he was.

Probably the first feature recognized as favoring finer grape production was limited soil fertility. Soils with just adequate nutrient levels restrict vegetative growth. This favors a higher proportion of photosynthate being directed to fruit maturation. This is particularly important near the end of ripening, when most flavor formation develops but photosynthetic efficiency may be declining. In addition, many low-nutrient soils are highly porous. This feature improves drainage. (Although increasing the potential for water deficit, waterlogging is avoided.) It also favors rapid warming of, and heat radiation from, the soil. This, in turn, can improve the microclimate around the vine, minimizing or avoiding frost damage. Excellent drainage also promotes early-spring growth and limits fruit cracking following heavy rains. Finally, vines grown on well-drained soil develop fewer micro and macro berry fissures, which favor infection by fungi and bacteria as well as attracting some insect pests.

Another feature recognized early on as benefitting grape quality was medium to low rainfall. These conditions also generate a climate unfavorable to the majority of vine pathogens. In Europe, most southern (Mediterranean) regions receive the majority of their precipitation during the winter. Thus, sufficient moisture is available for early growth, but subsequent water deficit tends to induce shoot growth termination by mid-summer. Avoidance of marked water stress is most important in the spring and early summer, up to the beginning of ripening (véraison). Subsequently, restricted water availability tends to enhance fruit quality and advance ripening. With restricted vegetative growth, more nutrients can be directed toward fully ripening the fruit. Because grapevines have the potential to root deeply, they often can avoid serious water deficit in deep soils, even during periods of drought. The ability of grapevines to root deeply has also probably helped limit the development of severe nutrient deficiencies in impoverished soils. Grapevines are one of the few crops that do well on relatively nutrient-poor soil.

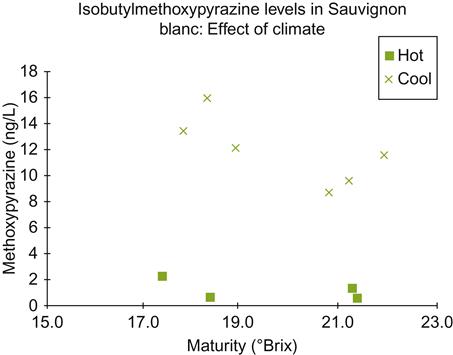

During the Roman expansion of vineyards into central Europe, it must have become apparent that growing cultivars near the northern limit of fruit ripening had both benefits and disadvantages. Wines from cooler mountainous sites in Italy were already acknowledged in Roman times for their superior quality. Cool conditions are now known to retain fruit acidity, improving a wine’s microbial and color stability. Temperate conditions also appear to favor the development and retention of grape aroma compounds. Although usually considered desirable, aroma retention can occasionally be a disadvantage. For example, the concentration of methoxypyrazines remains considerably higher in cooler than warmer climates (Fig. 5.1). In addition, clement weather has value in relation to winemaking and storage (in the absence of refrigeration), independent of its effects on viticulture. Nonetheless, growing grapevines at the higher latitude (or altitude) limits of viticulture carries increased risks of crop failure, due to the shorter growing season. It also enhances the likelihood of frost damage. This is probably how the benefits of solar-facing slopes and proximity to large water bodies were discovered.

Soil Influences

Of climatic influences, soil type (e.g., fluvisols, podsols, spodosols) appears to be the least significant factor affecting grape and wine quality (Rankine et al., 1971; Wahl, 1988). It is also poorly correlated with wine characteristics (Morlat et al., 1983; Noble, 1979; Maltman, 2008). Soil influences tend to be expressed indirectly through features such as heat retention, water-holding capacity, and nutritional status. For example, soil color and textural composition affect heat absorption by the soil and, thereby, fruit ripening and frost protection. Thus, when discussing soil, it is more useful and precise to focus specifically on its distinctive physicochemical attributes – textural composition, aggregate structure, nutrient availability, organic content, effective depth, pH, drainage, and water availability – and how each individually influences vine growth. Soil uniformity can occasionally be more important than any of its other attributes. Soil variability throughout a vineyard can be a significant source of asynchronous berry development, and lower wine quality.

Geologic Origin

The geologic origin of the soil and its underlying rock strata often has little influence on grape quality. Fine wines are produced on any of the three basic rock types – igneous (derived from molten magma, e.g., granite, basalt), sedimentary (originating from consolidated sediments, e.g., shale, chalk, and limestone), or metamorphic (arising from transformed sedimentary rock, e.g., slate, quartzite, and schist). There is also no incontrovertible evidence that any wine type is exclusively better based on the geological origin of the soil.

The uppermost few meters of the soil, in which the roots grow, may be of foreign origin, coming from tens to hundreds of miles away. This certainly applies to surface layers derived from alluvial deposits, former lake or ocean sediments, glacial till, and windblown deposits such as silt and loess, volcanic ash, or pyroclastic flows. Even when the soil is directly derived from the underlying rock strata, notably on slopes, it is usually markedly weathered, being both structurally and chemically modified. This is particularly so with the smallest category of soil particles – clay. With clay, whatever unique mineral composition existed in the parental rock has disappeared. In addition, it is well known that fine wines can be produced on almost any soil.

Examples of famed wine regions where the soils are primarily derived from a single rock type are Champagne (chalk), Chablis (Kimmeridgian limestone), Jerez (limestone), Porto (schist), and Mosel (slate). However, equally famous wine regions have soils derived from a mixture of rock types, and are nonhomogeneous across the region. Examples of this situation are the Rheingau, Bordeaux, and Beaujolais (Wallace, 1972; Seguin, 1986). Some cultivars have been reported to do better on soils composed of specific rock types (Fregoni, 1977; Seguin, 1986). This could be a simple case of correlation, not causation. The successful production of wine from most popular European cultivars on the range of soils in the New World argues against any clear cultivar/soil type connection. Even the supposedly famous chalk of Champagne limits access to essential minerals, such as zinc and iron, due to its alkalinity. Regrettably, marketing does not ‘demand the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.’

What geologic history does impose is a site’s basic topography. This, in turn, affects solar exposure, temperature, precipitation and airflow patterns, soil structure, nutrient content, and drainage attributes. Thus, indirectly, geologic history sets limits to what viticulture can achieve, and the types of wine that can be produced most successfully. Although affecting conditions as circumscribed as individual sites within a vineyard, these features rarely if ever impose distinctive sensory attributes on a wine. They are far too subtle and modified beyond sensory recognition during vinification and maturation. For further discussion of the influence of geology on wine attributes see Maltman (2008).

Texture

Soil texture refers to the size and proportion of its mineral content. Internationally, four standard categories are recognized – coarse sand, fine sand, silt, and clay. Chapman’s (1965) recognition of a larger number of categories, including gravels, pebbles, and cobbles, is particularly relevant when dealing with several important vineyard regions. Nonetheless, most agricultural soils are classified only by their relative sand, silt, and clay contents. In the common vernacular, heavy soils have a high proportion of clay, whereas light soils have a high proportion of sand.

Particles larger than sand consist of unmodified rock material. Sand consists primarily of resistant residues, mostly silicates, incorporating some other mineral salts, oxides, and hydroxides, notably iron and aluminum. In contrast, clay particles are chemically and structurally transformed minerals, bearing little resemblance to their parental origin. Clay consists primarily of a complex of adherent, microscopic plates. These may be stacked, more or less irregularly, on top of each other. These can form crystals, especially when plates of alumina are sandwiched between sheets of silica. Montmorillonites are an example. In this formulation, water can readily penetrate between the plates, causing swelling. This increases their effective surface area, water and nutrient holding capacity, and ability to slide relative to one another. A predominance of monovalent sodium increases the tendency for aqueous enlargement, whereas more bivalent calcium produced more cross attractions, reducing swelling in water. Clay particles, such as kaolinite, based on single sheets of silica and alumina, bind together more strongly. They do not expand significantly when hydrated, and may form edge-to-face aggregates as opposed to parallel sheets. Silt particles are those intermediate in size. They possess properties transitional between sand and clay.

With its large surface area to volume (SA/V) ratio, plate-like structure, and net negative charge, clay can have a major influence on the physical and chemical attributes of a soil. Clay particles are so minute that they possess colloidal properties. Thus, they tend to be gelatinous and slippery when wet (the plates slide relative to one another), but hard and cohesive when dry. After hydration, clay particles with weak interplate bonding, such as montmorillonites, expand like a sponge. As water infiltration forces the plates apart, the diameter of the space (pores) separating individual clay particles decreases. This can markedly reduce water percolation and air infiltration into, and through, soils high in clay content. The large SA/V ratio, combined with the net negative charge, permits clay plates to attract, retain, and exchange large quantities of positively charged ions (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and H+). Bivalent cations and water help bind individual plates of clay crystals together. This is a central facet in the formation and maintenance of the aggregate structure of good agricultural soils. The large SA/V ratio also allows a clayey soil to absorb large quantities of water. However, the bonding is so strong that much of the water associated with clay particles is unavailable to plants. In contrast, soils with a coarse texture allow most of the water to percolate through and into the subsoil, out of reach to most vine roots. What remains in the upper soil layer is held weakly, but can be readily extracted by plant roots.

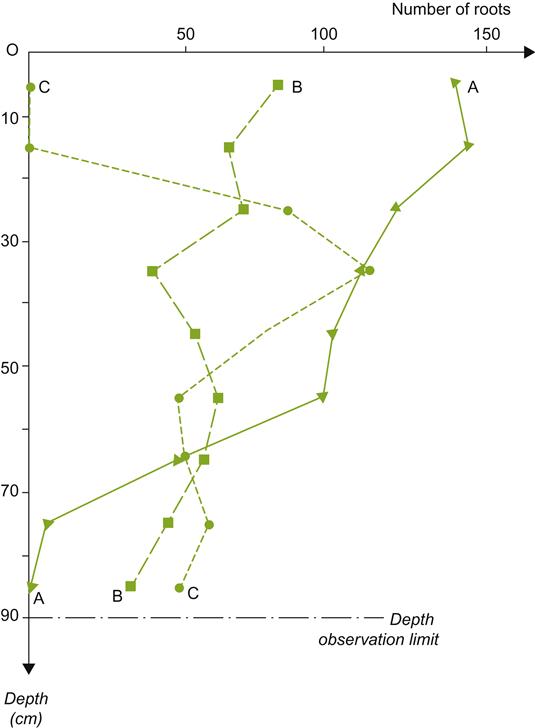

Because features such as aeration, as well as water and nutrient availability, are markedly influenced by soil texture, this property can significantly affect vine growth and fruit maturation, notably via influences on root growth and distribution. In addition, anecdotal reports suggest that phylloxera infestation is minimal in sandy soils, possibly by severely restricting insect movement in the soil. Although there are comparatively few reports that have directly studied the effects of soil texture on vine growth, Fig. 5.2 provides an example.

Another important property, partially based on the soil’s textural character, is heat retention. Fine-textured soils reflect more heat than heavy soils (a function of the albedo). In addition, much of the heat absorbed from the sun may be transferred to water as it evaporates. Because of the high specific and latent heat attributes of water, this can result in considerable heat loss as water evaporates and diffuses into the air, delaying soil warming in the spring. However, once warmed, it stays warm longer. In contrast, stony soils retain more of the heat they absorb within their structural components, but it is easily reradiated back into the air at night. The heat thus liberated can significantly moderate the vine microclimate, reducing the likelihood of frost damage and accelerating fruit ripening in the autumn (Verbrugghe et al., 1991). Soil compaction can also influence the temperature in vine rows, potentially reducing frost damage on cool nights (Bridley et al., 1965).

Structure

Soil structure refers primarily to the association of soil particles into complex aggregates. Aggregate formation starts with the binding of mineral (clay) and organic (humus) colloids via bivalent ions, water, microbial filamentous growths, and plant, microbial, and invertebrate mucilages. These aggregates bind with particles of sand and silt, as well as organic residues, to form a variety of agglomerates of differing size and stability (see Fig 4.49). These are subsequently rearranged or modified by the burrowing action of the soil fauna, root growth, and frost action.

Soils high in aggregate structure are friable, well aerated, and easily penetrated by roots; have high water-holding capacities; and are considered to be agriculturally superior. Heavy clay soils are more porous, but the small diameter of these pores compromises root penetration, and results in poorly aerated conditions when wet. As a consequence, roots remain at or near the surface, exposing vines to severe water deficit under drought conditions. Lighter soils are well drained and aerated, but the large pores retain relatively little water. Nonetheless, vines on light soils may experience less severe water deficit under drought conditions, if the soil is sufficiently deep to permit root access to groundwater. Soil depth may also offset the nutrient-poor status of many light soils. The negative effects of the small and large pores of heavy and light soils, respectively, may be counteracted by humus. Humus modulates pore size, facilitating the upward and lateral movement of water; increases water absorbency; and retains water at tensions readily accessible to roots. Alternatively, soil crumb structure may be improved, benefitting grapevine performance, with the use of a cover crop or mulch (Wheaton et al., 2008).

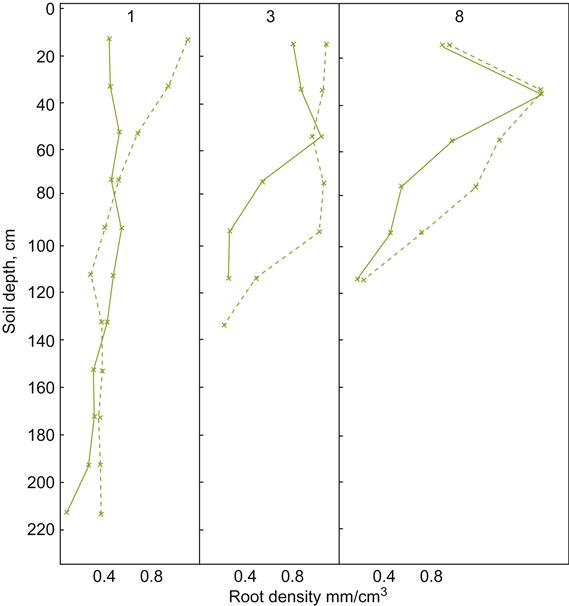

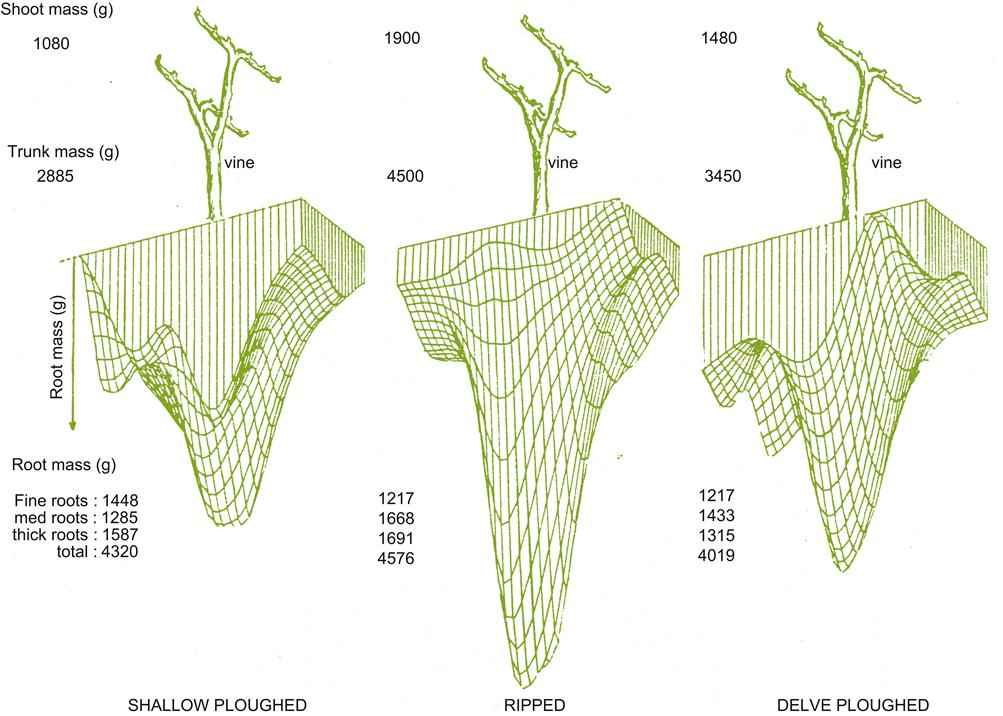

Although soil structure affects aeration, as well as mineral and water availability, its effects may be modified by vineyard practices such as tillage. Consequently, the effects of soil structure are not a constant feature of a site, and their significance to grape and wine quality is difficult to assess accurately. Under zero tillage, the number, diameter, and pore area are significantly greater than under cultivation. Conventional tillage results in greater total porosity, but this consists primarily of a few large irregularly shaped cavities (Pagliai et al., 1984). Generally, root development is better under zero tillage (Fig. 5.3). Under no-till conditions, most root development occurs in the upper portion of the soil, whereas conventional cultivation limits root ramification within the tilled zone. Under grass cover, root distribution is relatively uniform in the top one meter. Cultivated vineyards show lower levels of organic material (Pagliai et al., 1984). This may result from enhanced aeration and solar heating. Both stimulate microbial mineralization of the soil’s organic content.

Drainage and Water Availability

As mentioned, both soil texture and structure have effects on water infiltration. Both properties also affect water availability. Once water has moved into the soil, water may be bound to colloidal materials by electrostatic forces, adhere to pore surfaces by cohesive forces, or percolate through the soil under the action of gravity. Depending on the clay content, and its tendency to swell (constricting soil-pore diameter), the rate of infiltration will slow. Capillary flow is also dependent on pore diameter. Because of variation in pore diameter, and its discontinuity in the soil, water rarely rises more than 1.5 m above the water table. Only water retained by cohesive forces or sorbed to soil colloids remains available for root uptake after percolation has come to completion.

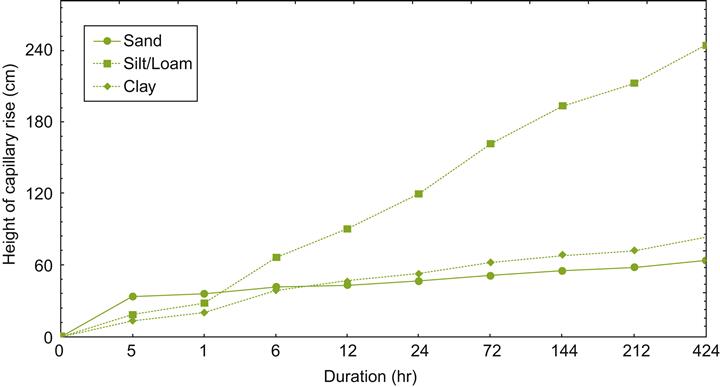

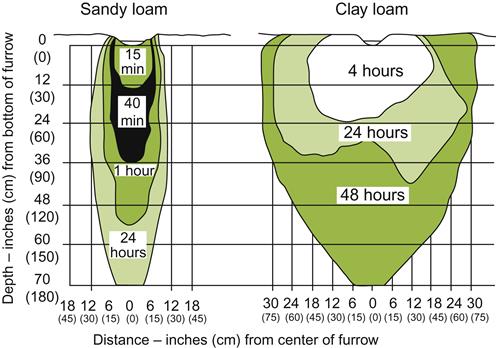

Capillary water is important because cohesive forces permit both upward (Fig. 5.4) and lateral (Fig. 5.5) movement. Often it is the rate, not the distance traversed that is the critical factor influencing the importance of capillary flow. For example, the soil surface can dry to the wilting point even when the water table is less than a meter below the surface. As indicated in Fig. 5.4, capillary flow has its greatest significance in silty soil. Capillary movement is rapid in sandy soils, but limited, whereas in clayey soils it is marked, but too slow to be of much significance. In most situations, the rate of capillary flow is less than the rate at which plant roots absorb water, often requiring continued root growth into new sites. Additional details of the relationship between soil texture and hydraulic properties can be obtained from Saxton (1999) and Saxton et al. (1986).

Water that fills large pores (free water) rapidly percolates into the subsoil, becoming lost to the plant, unless the root system penetrates deeply. Hygroscopically bound water is largely unavailable for root extraction. During drought, however, hygroscopic water may evaporate and move upward in the soil. If it condenses as the soil cools at night, it may become available to the roots. This phenomenon may be of importance in sandy soils, in which high porosity permits greater air circulation.

In Bordeaux, the ranking of cru classé estates has been correlated with the presence of deep, coarse-textured soils, located on elevations close to rivulets or drainage channels (Seguin, 1986). These features promote rapid drainage, and are thought to permit deep root penetration. Free water can percolate to a depth of 20 m within 24 h. Thus, grapevines are less likely to suffer waterlogging in heavy rains or water deficit during drought. Although some cultivars are relatively tolerant of waterlogged soils (Kraft and Conklin, 1976), high soil-moisture content can accentuate cracking of the berry skin and susceptibility to bunch rot (Seguin and Compagnon, 1970).

Even in shallow soils, unique features may diminish the development of water deficit under drought conditions, or of waterlogging during rainy spells. For example, the compact limestone underlying the shallow soils in St. Émilion permits the effective upward flow of water from the water table. It was estimated that 70% of the water uptake by vines in 1985 came from this source (Seguin, 1986). Other regions where the water retentive characteristics of the bedrock can be important in vine growth are Coonawarra (Hancock and Huggett, 2004) and the Mosel (Ashenfelter and Storchmann, 2001). In the Upper Douro, the potential for root penetration into the schistose bedrock, versus the impervious granite of other sites, probably explains their preference in the ranking of sites in the region (Maltman, 2008).

In general, good vineyard soil has been characterized by the following water infiltration and retentive attributes (Cass and Maschmedt, 1998):

500 mm infiltration rate per day

500 mm infiltration rate per day

>150 mm total available water in the root zone (water extracted by roots<−0.15 MPa)

>150 mm total available water in the root zone (water extracted by roots<−0.15 MPa)

>75 mm of readily available water in the root zone (water extracted by roots<−0.2 MPa)

>75 mm of readily available water in the root zone (water extracted by roots<−0.2 MPa)

<1 MPa penetration resistance at field capacity (or 3 MPa at wilting point)

<1 MPa penetration resistance at field capacity (or 3 MPa at wilting point)

<1 d soil saturation per irrigation cycle or rainfall occurrence.

<1 d soil saturation per irrigation cycle or rainfall occurrence.

Where drainage is poor, waterlogging can be a recurring problem. Not only does it retard vine growth, favor the development of chlorosis in lime soils, and encourage attack by several root pathogens, it causes problems with the movement of machinery through a vineyard. Some problems are caused by the combined effects of reduced oxygen availability in soil (oxygen diffuses about four magnitudes more slowly in water than in air) and increased concentrations of carbon dioxide and ethylene. Under prolonged waterlogging, toxic amounts of hydrogen sulfide may accumulate, due to the anaerobic metabolism of soil bacteria. In arid regions, poor drainage significantly enhances salt buildup in the root zone. This results from insufficient leaching of salts, transported upward in capillary water by water evaporation at the soil surface.

Open ditches may provide adequate drainage in regions with shallow grades, especially when covered with grass to minimize erosion. However, the laying of drainage tiles or pipes is required in most situations where waterlogging is a problem. It is desirable to have unrestricted drainage to a depth of at least 2–3 m in most situations. Where a shallow hardpan is the source of poor drainage, deep ripping to break the layer may be the best solution (Fig. 5.6). For details on drainage systems consult Webber and Jones (1992).

Soil Depth

In addition to texture and structure, effective soil depth influences water availability. Hardpans near the surface reduce the usable soil depth and enhance the tendency of soil to waterlog in heavy rains and fall below the permanent wilting percentage under drought conditions. Limiting root growth to surface layers also influences nutrient access. For example, potassium and available phosphorus tend to predominate near the surface, especially in clayey soils, whereas magnesium and calcium more commonly characterize the lower horizons. Soils characteristically vary in nutrient content throughout their various horizons.

Establishing a desirable effective soil depth is clearly best achieved before planting. Breaking existent hardpans by soil ripping is standard in several countries. An alternative procedure is mounding topsoil in regions where the vines are to be planted. This is particularly useful in situations where high water tables are unavoidable, and under saline conditions. Planting a permanent groundcover or mulching helps to minimize erosion from the mounds. Where root penetration is limited by high acidity in one or more soil horizons, soil slotting can significantly increase root soil exploration.

Effective soil depth may decrease as a consequence of various viticultural techniques. For example, cultivation promotes microbial metabolism and the degradation of organic material. This weakens crumb structure, leading to the release and downward movement of clay particles. In addition, salinization as a result of improper irrigation can disrupt aggregate structure, releasing clay particles. In either instance, movement of clay particles downward tends to plug soil capillaries. Over time, this can result in the formation of a claypan.

Soil Fauna and Flora

The detrimental effect of soil pathogens is well known, as are the beneficial influences of mycorrhizal fungi. Far less appreciated is the activity of the thousands of other members of the soil fauna and flora. These include innumerable species of bacteria, fungi, algae, protozoans, nematodes, springtales (Collembolae), insect larvae, mites, and earthworms. Bacteria occur in numbers in excess of 108 cells/g soil. It is variously estimated that from 30 to 80% of soil bacteria have as yet to be cultured and identified, due to their complex nutritional requirements and/or symbiotic relationships. Most of the fauna are the soil equivalent of terrestrial herbivores, but in miniature. Figure 5.7 illustrates the relative size and shape of some of the biota found in small soil aggregates. Most of their effects are known only in general, and from investigations unrelated to viticulture.

Among the major beneficial effects of the soil fauna and flora is the generation of the soil’s aggregate structure, and, over centuries, weathering of rock to silt and finally clay. Bacteria are especially active in releasing polysaccharides that bind them to soil particles and, consequently, soil particles to each other. Fungi and actinomycetes further accentuate this binding action with their long, branched, filamentous growths. Their subsequent decay probably forms the microtrenches and microridges occasionally seen in clay accretions (Sullivan, 1995). Additional mucilaginous secretions are released by root tips, and by the feeding activities of earthworms and browsing microfauna.

Although algae and some bacteria are net producers of soil organic material, the majority of the nutrients on which the soil biota live come from green plants. These are derived primarily from leaves and from the death of feeder roots. The initial decomposers are bacteria and fungi. These are in turn grazed by the fauna, notably protozoa, nematodes, and mites, or consumed along with soil during the feeding of earthworms or various insect larvae. Their feeding releases inorganic nutrients bound in the microbial flora, which promotes additional rounds of microbial decomposition on the defecated material. The faunal grinding action also speeds the degradation of the morphological and cellular structure of plant remains. This especially helps expose plant cell-wall constituents to direct microbial enzyme action. If conditions are favorable (warm and moist), most organic material (with the exception of woody tissues) is rapidly mineralized. However, in cooler or drier conditions, mineralization is slow and partial. What remains tends to be a collection of highly complex (refractory), oxidized, phenolic materials. It forms the bulk of what is called humus. Humus, along with polysaccharides released by the soil fauna and flora, constitutes the bulk of organic components forming the aggregate structure of the best agricultural soils.

Another significant contribution of the soil microbiota, notably several genera of bacteria, is in the interconversion of various forms of nitrogen. Ammonia, released during decomposition or added as fertilizer, is converted to nitrate by nitrifying bacteria. Other bacteria, under anaerobic conditions (such as the anoxigenic centers of soil aggregates), perform the reverse reaction – ammonification. In addition, anaerobic bacteria can release nitrogen gas from nitrate, in a process termed denitrification. Under low nitrogen conditions, other groups of bacteria fix nitrogen gas, releasing nitrates into the soil. Nitrogen fixation is particularly well known, relative to the action of rhizobial bacteria in the root nodules of legumes. Nonetheless, it also occurs in free-living, nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria and cyanobacteria.

Acids released by bacterial and fungal metabolism are also important in the extraction (and eventual solubilization) of nutrients from the soil’s mineral matter. By facilitating solubilization, soil microbes participate in the transformation of sand and silt to clay.

Nutrient Content and pH

Nutrient availability in soil is influenced by many, often interrelated, factors. These include the parental rock material, particle size, humus and water content, pH, aeration, temperature, root surface area, the rhizoflora, and mycorrhizal development. Nonetheless, the ultimate source comes from the rock substrata or material transported in from elsewhere. Consequently, it has been thought that the superiority of certain vineyard sites might be due to the nutrient status of its inorganic content. This can vary widely. Differences in soil nitrogen status have been associated with wine quality (Ough and Nagaoka, 1984). However, this has no connection with the soil’s mineral base. Fregoni (1977) interpreted differences in wine quality as resulting from mineral differences in their associated vineyard soils. Although interesting, few researchers would readily accept such correlations as being causally related, without supporting experimental evidence. In Bordeaux, prestigious vineyard sites have been noted as possessing higher humus and available nutrient content than less highly ranked sites (Seguin, 1986). Occasionally, such data have been used to explain the historical ranking of these sites. However, their nutrient status may be equally and possibly even better explained as a result of the appropriate maintenance and a long history of manure addition (Fig. 4.48). This may be a case where a marginally better site leads to better wine, and higher financial returns. This permits and may encourage better soil management. This could result in even further improvements in grape quality, better wine production, increased recognition, demand, and enhanced profit; the repeating cycle generating a wonderful upward spiral of increasing differentiation from initially only marginally dissimilar sites – the opposite of a ‘Catch 22.’

Soil pH is one of the most well-known factors affecting mineral solubility and, thereby, availability (Fig. 4.39). Nevertheless, actual absorption by the vine is primarily regulated by root physiology, genotype, and mycorrhizal association. Thus, grapevine mineral content reflects but does not directly mirror the soil’s mineral content. In addition, excellent wines may be derived from grapes grown on marginally acidic, neutral, and alkaline soils. Thus, apart from where deficiency or toxicity are involved, there seems little justification for assuming that wine quality is dependent on either a specific soil pH or mineral composition.

Color

Soil color is influenced by its mineral composition as well as water and organic contents. For example, soils high in calcium tend to be white, those high in iron are reddish, and those high in humus are dark brown to black. Soil needs only about 5% organic material to appear black when wet. Soil color is also a reflection of its age, and the temperature and moisture characteristics of the climate. Thus cooler regions tend to have grayish to black topsoils, due to the accumulation of humus. In moist warm regions, soils tend to be more yellowish-brown to red, depending on the hydration of ferric oxide and extensive weathering of the soil's parental mineral content. Rapid mineralization of the organic content in warm moist regions means that insufficient humus accumulates to have a major impact on soil color. Arid soils tend to be light in color (little staining from the low organic content), and primarily express the color of their mineral content.

Following rain, water temporarily darkens the soil’s color by increasing light absorption. In addition, moisture can have long-term effects on soil color. For example, under anaerobic waterlogged conditions, iron oxides occur primarily in the ferrous state. These can give the soil a subtle bluish-gray tint. A mottled rusty or streaked appearance, in a grayish matrix, may indicate variably or improperly drained soils. A blackish color, in the absence of organic material, may indicate staining by manganese oxides.

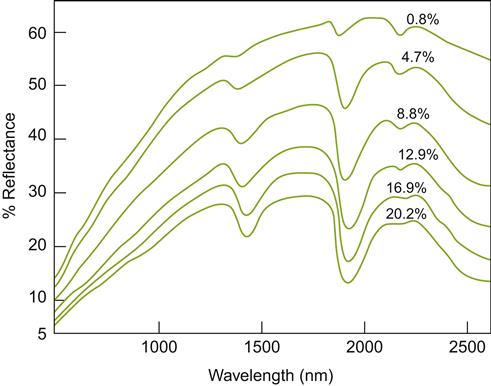

Color influences the rate of soil warming in the spring, and cooling in the fall. Dark soils, irrespective of moisture content, absorb more heat than do more reflective, light-colored soils (Oke, 1987). Soils of higher moisture content, being darker, absorb more solar radiation (Fig. 5.8), but warm more slowly than drier soils. This apparent anomaly arises from the high specific heat of water – it consumes large amounts of energy during warming. Consequently, the surfaces of sandy and coarse soils both warm and cool more rapidly than do clayey soils of the same color. Rapid cooling (heat loss) from the soil at night can generate significant warming of the air and fruit close to the ground. Reflective groundcovers can slow warming of the soil during the spring, but moderate its decline during the fall. Analogous variation in daily soil temperature occurs under mulches (Whiting et al., 1993; see Fig 4.71). In contrast, plastic mulches often enhance early vineyard soil warming (Ballif and Dutil, 1975).

The microclimatic effects of soil color and moisture content on temperature are most significant during the spring and fall. In the summer, temperature differences caused by soil surface characteristics and shading generally have little effect on vine growth and fruit maturity (Wagner and Simon, 1984). Nonetheless, warm soils may enhance microbial nitrification, enhance potassium uptake, and depress magnesium and iron absorption by the vine.

Occasionally, red varieties have been selectively grown in dark soils and white varieties in light-colored soils. In marginally cool climates, this could provide the greater heat needs required for full color development in red cultivars. Nevertheless, excellent results can be obtained where the cultivation of white and red varieties on light and dark soils is reversed (Seguin, 1971).

Soil color can also influence vine growth directly by reflecting photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) into the canopy. It can influence grape yield; sugar, anthocyanin, polyphenol, and free amino acid contents (Robin et al., 1996); and carotenoid synthesis and conversion to norisoprenoids (Razungles et al., 1996). In contrast, in a study on geotextile mulches, reflection from a white surface appeared to increase yield, but did not significantly affect fruit ripening or composition (Hostetler et al., 2007).

Organic Content

The organic content of soil improves water retention and permeability, as well as enhancing its aggregate structure, nutrient availability, and buffering capacity (see Chapter 4). Thus, its benefits are indirect, roots typically absorbing only inorganic compounds. Important exceptions are systemic control agents and highly volatile compounds, such as ethylene (released by many soil microorganisms). Thus, there is no evidence supporting the common contention that soil directly contributes to the aromatic (organic-based) character of wine. The ‘earthy,’ ‘manure,’ and ‘flinty’ qualities of certain regional wines arise during wine production and maturation, and are not derived from the soil. Some ‘terroir’ attributes actually originate from improper barrel hygiene and the development of ‘Brett’ off-odors. These may be euphemistically described as ‘barnyardy.’ Even metallic sensations do not arise from a wine’s metal content, being derived instead from oxidized fatty acids (Lawless et al., 2004). Thankfully, the aromatic compounds produced by manure, the earthy odors generated by actinomycetes, and the thiols generated by anaerobic bacterial action in soil aggregates are not absorbed and translocated to ripening grapes.

In situations where the organic content is low (sandy soils), or has been reduced by cultivation, the most common means of increasing the humus content is with compost or a groundcover. Where available, well-aged farm manure is an excellent means of enriching the soil’s organic content (see Fig. 4.48). Straw used as a mulch is much less effective, and its incorporation into the soil slow. Earthworms eventually incorporate the straw into the soil, along with the production of macropores that aid water infiltration. However, because of its high carbon/nitrogen ratio, straw incorporation (and decomposition) can generate temporary nitrogen deficiency. Thus, nitrogen may need to be added to compensate for the consumption of nitrogen by decay microorganisms, until humifaction of the straw is complete.

Topographic Influences

Similar to the data on soil attributes, much of the information on slopes is circumstantial. Nevertheless, the effects tend to become more evident with increasing latitude and/or altitude. The beneficial influences of sunward-angled sites include enhanced exposure to visible and infrared radiation; earlier soil warming; diminished frost severity; and improved drainage. For the grapevine, photosynthetic potential is increased; fruit ripening advanced; berry color and sugar–acid balance improved; and the growing season extended. Microclimatic disadvantages include increased potential for soil erosion, nutrient loss (leaching), water deficit, and earlier loss of snow cover. The potential for bark splitting during the winter is enhanced, and cold acclimation may be lost prematurely. In addition, as the slope increases, the performance of vineyard activities becomes progressively more difficult, soon making most mechanization impossible. The net benefit of a sloped site often depends on its inclination (vertical deviation), aspect (compass orientation), latitude, and soil type, as well as cultivar and viticultural choices.

Solar Exposure

When the beneficial influences of a sloped vineyard are sufficient, they may offset the difficulties associated with performing vineyard activities. Of particular significance is the improved solar exposure created by a solar aspect. The benefits of an inclined location become progressively important with increased vineyard latitude and/or altitude. Not surprisingly, Germany, the most northerly major wine-producing region in Europe, is renowned for its steep, south-facing vineyards.

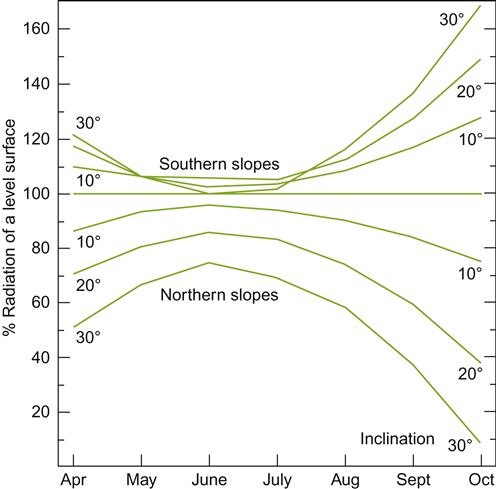

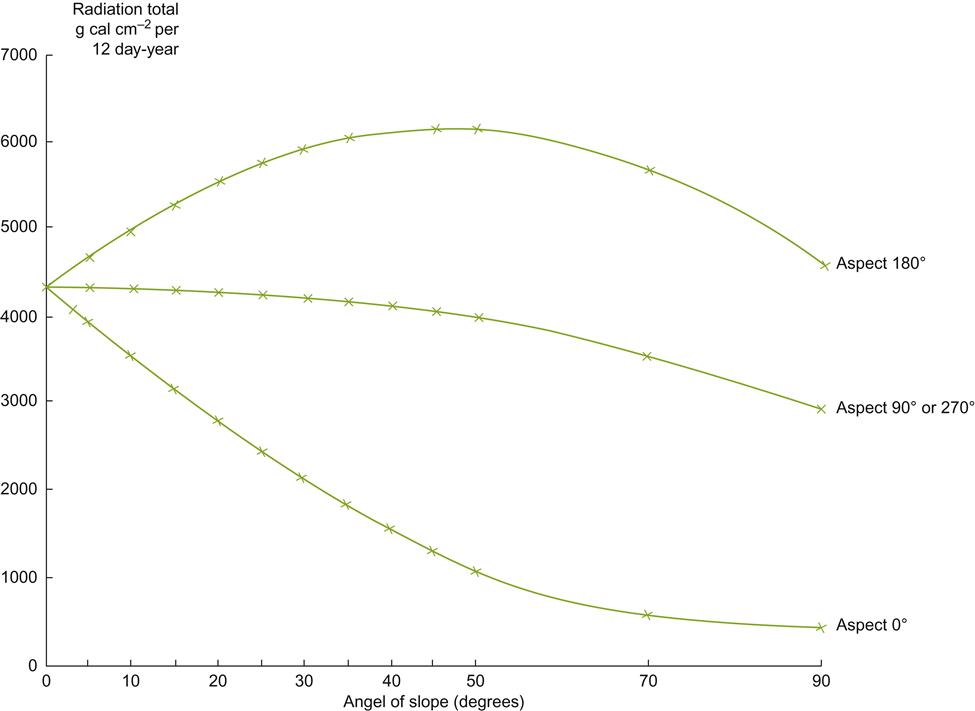

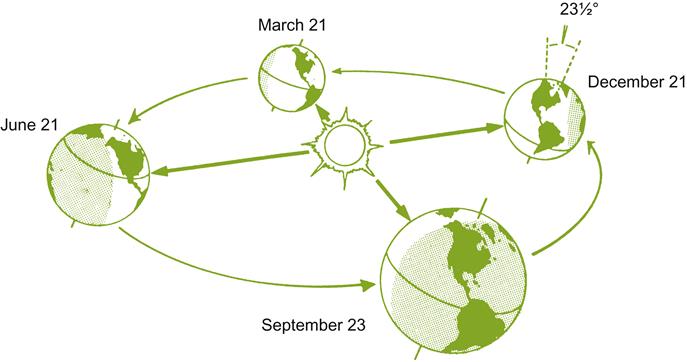

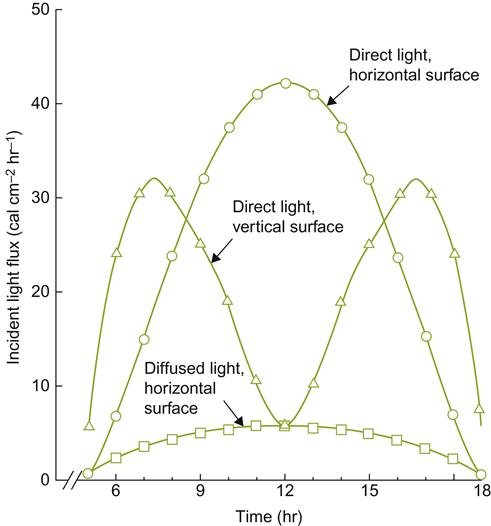

The primary advantage created by a favorable slope orientation and inclination relates to the reduced angle of incidence at which solar radiation impacts the vineyard. This increases both light exposure and heating. At the highest latitudes for commercial viticulture (∼50°), the optimal inclination for light exposure on a sun- facing slope is about 50°. Although slopes this steep are too difficult to work, solar exposure is only slightly less at a slope of 30° (Pope and Lloyd, 1974). This is generally considered the upper limit for manual vineyard work. Machines seldom work well at inclinations much above 6° (a slope of 10.5%). Sun exposure on east- and west-facing slopes is little affected by inclination, apart from those above 50°. Polar-facing slopes have a correspondingly negative effect on solar input. Figures 5.9 and 5.10 illustrate the influence of slope inclination and aspect on seasonal influences and yearly solar inputs. These influences are most marked when the altitude of the sun (position above the horizon) is lowest (winter), and least noticeable when the solar altitude is highest (summer).

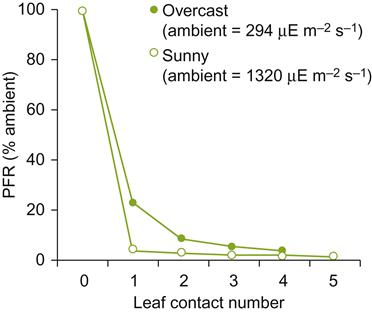

Another factor influencing the significance of slope on light incidence is the frequency of cloudiness. Cloud cover, by dispersing solar radiation across the sky, eliminates the solar influences of equatorial-facing slopes. Cloud cover also eliminates the reflection of heat and photosynthetic radiation off water surfaces (see below and Munez et al., 1972). Occasionally, this reduced effect can be beneficial in the spring. It could diminish premature cold deacclimation and budbreak, and the associated increase in the likelihood of frost damage. In contrast, sunny weather in the fall is desirable as it favors maximal light reflection from water and supplements heat accumulation during ripening and harvest.

For maximal solar exposure, the best slopes are those directed toward the equator. In practice, however, the ideal aspect may be influenced by local factors. If fog commonly develops during cool autumn mornings, the preferred aspect may possess a westward aspect. The scattering of light by fog eliminates the radiation advantage of a solar-directed slope. In the late afternoon, when skies are more commonly clear, a southwest aspect provides optimal solar exposure in the Northern Hemisphere. Such situations are not uncommon along the Mosel and Rhine rivers in Germany, and the Neusiedler See in Austria.

Another important property of sunward-facing slopes is radiation reflected from water and soil surfaces (albedo). This is particularly significant at low sun altitudes. At high solar elevations, the albedo off water is low (2–3% from a smooth surface and 7–8% off a rough surface). However, at low sun elevations (<10°) reflected solar radiation can reach more than 50% of that received directly from the sun (Büttner and Sutter, 1935). Consequently, light reflected from water bodies is especially significant during the spring and fall. This has particular value for sloped vineyards in high latitudes – the steeper the slope, the greater the potential interception of reflected radiation. Radiation reflected off the Main River in Germany (49°48′N) can constitute 39% of the total radiation received by south- facing vineyards in early spring (Volk, 1934). This level of additional exposure could advance snow cover loss, promote early growth initiation, and enhance photosynthesis and fruit ripening in the autumn. The potential significance of reflected light is indicated in a series of experiments conducted by Robin et al. (1996).

The reflection of solar radiation off water does not directly augment heating. Most of the infrared radiation is absorbed by the water, even at low sun altitudes. Nonetheless, heating can result indirectly from the absorption of the additional visible and UV radiation received.

Although augmenting solar exposure is generally beneficial at high latitudes and altitudes, the opposite may be true at low latitudes. Here, diminished sun exposure may favor a cooler microclimate, leading to retention of more acidity and grape flavor. Correspondingly, east-facing slopes may be preferable. An eastern aspect exposes vines to the cooler morning sun and provides increased shading from the hot afternoon sun.

Only rarely are polar-directed slopes considered of viticultural value. However, some of the best sites for Pinot noir in Champagne are on the north-facing slope of the Montagne de Reims. This may result from the reduced color of the grapes, facilitating the production of a white (sparkling) wine from these ostensibly red grapes.

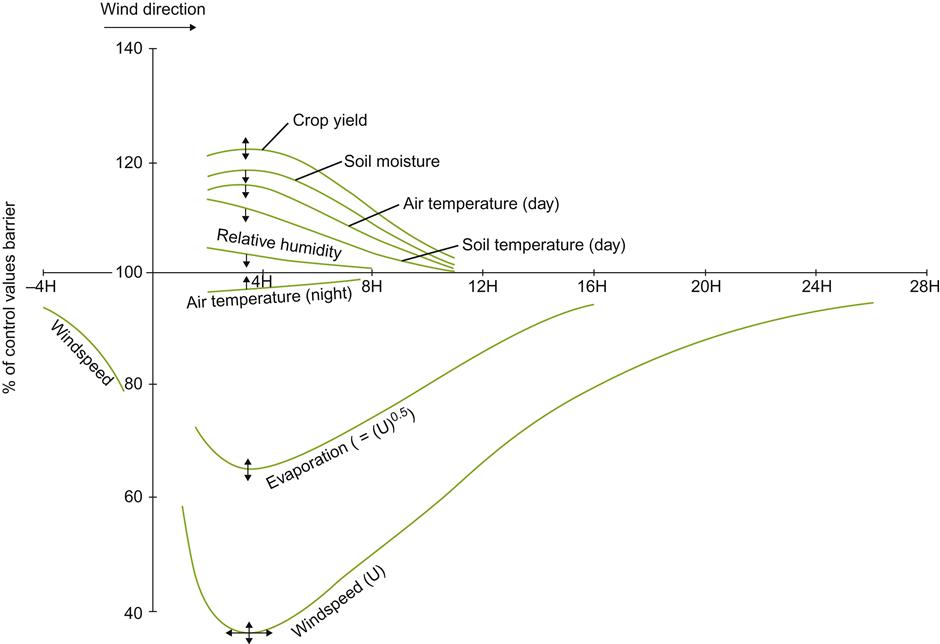

Wind Direction

Prevailing wind direction can significantly influence the features provided by a slope and the desirability of a particular row orientation. The heat accumulation achieved on sunward slopes can be lost if winds greater than 7 km/h frequently blow down vineyard rows. Crosswinds require twice the velocity to produce the same effect (Brandtner, 1974). Updrafts through vineyards may also diminish the heat accumulation potential of sun-facing slopes (Geiger et al., 2003).

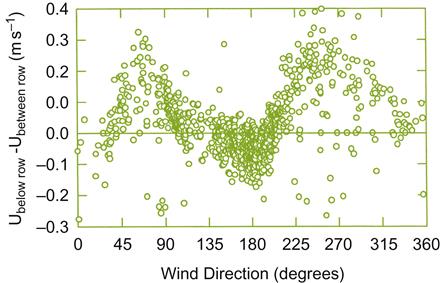

At high latitudes, vine rows commonly are planted directly up steep slopes to facilitate cultivation. Offsetting row orientation to minimize the negative influences of the prevailing wind direction is generally impractical under such conditions. Figure 5.11 illustrates the effect of wind direction on wind speed below and between vine rows. However, terracing vineyards on slopes may permit some row alignment relative to the prevailing winds. Regrettably, wide terracing partially eliminates some of the advantages of steeply sloped sites. In addition, unless appropriately designed, terracing may increase soil erosion (Luft et al., 1983).

In humid climates, positioning vine rows 90° to the prevailing winds can increase foliage drying by enhancing wind turbulence. This could reduce the need for fungicide application in disease control. If the vineyard faces sunward, the enhanced solar radiation further speeds the drying action of the wind. In dry environments, rows aligned parallel to the prevailing winds may reduce foliage wind drag and potentially reduce evapotranspiration (Hicks, 1973), whereas a perpendicular alignment may lead to increased water deficit due to stomata remaining open longer during the day (Freeman et al., 1982). Thus, the most appropriate row alignment will depend on the climatic limitations it is designed to alleviate. The presence of natural or artificial shelterbelts (see later in the chapter), modifying the velocity, turbulence, and wind flow, may further influence optimal row alignment and slope orientation.

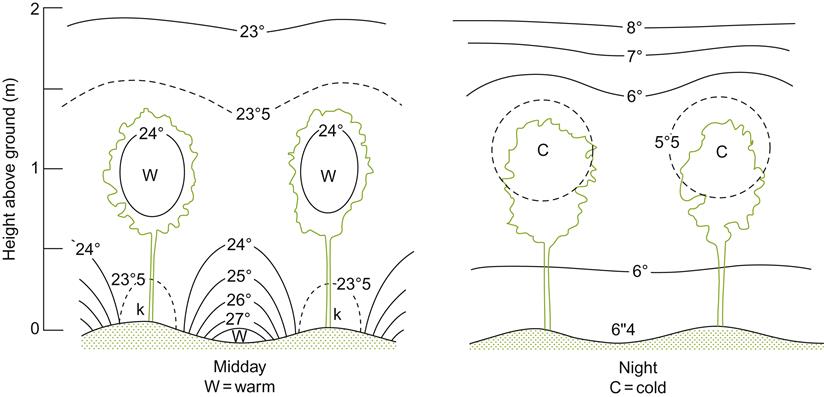

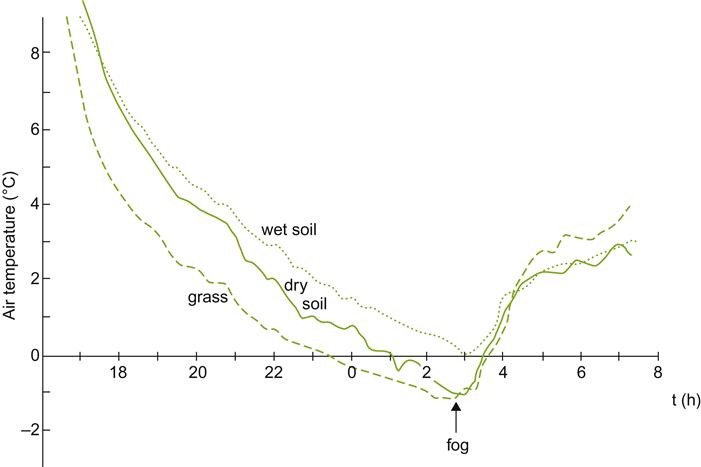

Frost and Winter Protection

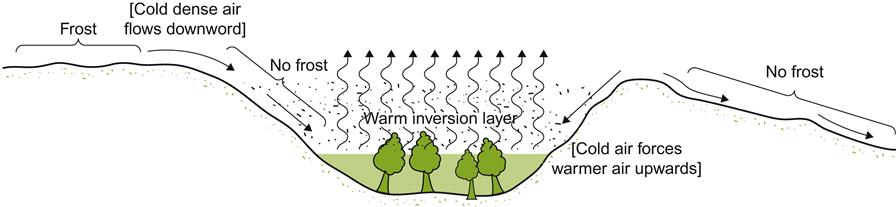

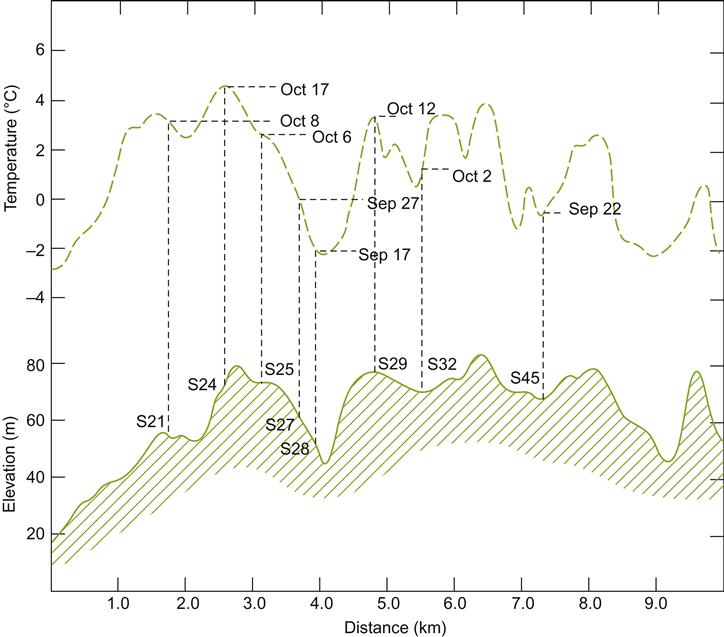

Sun-facing slopes have the potential to provide additional frost-free days in cool climates. This benefit results not only from improved heat accumulation, but also from the downward flow of cold air away from the vines. Under cool, clear, atmospheric conditions, heat radiation from the soil and grapevines can be considerable. Without wind turbulence, an inversion layer can form, resulting in temperatures falling near or below freezing at ground level during the spring or fall. Sloped sites often experience some protection from this phenomenon. Cold air flowing downward and away from the vines into low-lying areas can extend the frost-free season on slopes by several days or weeks (Fig. 5.12). Conversely, it can shorten it along the valley floor. Depending on the elevation and length of the slope, maximal protection may be achieved either at the top or, more commonly, in the mid-region of the slope. The degree of protection often depends on wind barriers, such as tree shelters, or topographical features. These influence airflow among and away from the vines (Fig. 5.13). Although this is most well known on the meso-scale of sloped vineyards, similar phenomena occur on a microclimatic scale with undulations in the terrain. Differences in elevation of 0.5 m can be significant to relative bud or fruit damage.

Such airflow can be significant, not only to frost development, but also to chill damage. Exposure to temperatures below 10°C has been reported to permanently disrupt fruit maturation in some varieties (Becker, 1985a). Another feature, often of greater significance than the actual temperature drop, is the rate of the decline, and, corresponding, the ability of cells to adjust to the change.

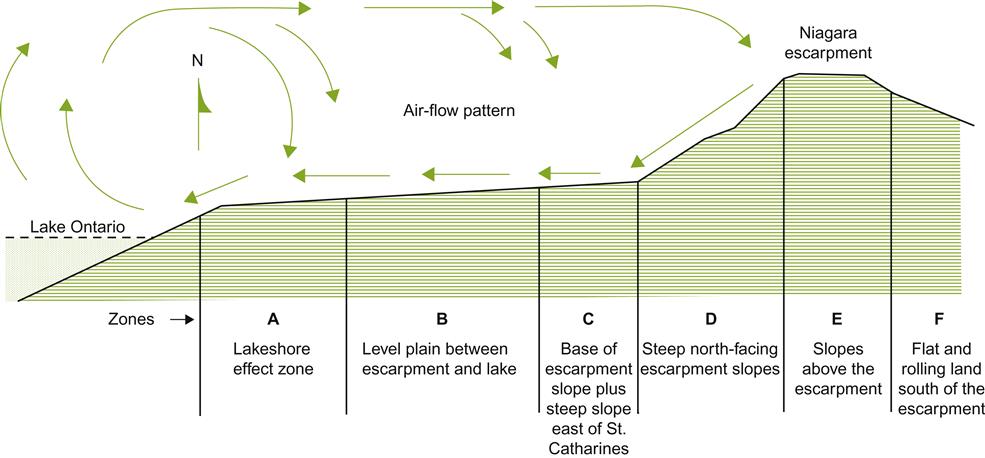

Where sloped sites are associated with lakes and rivers, the water can further modify vineyard microclimate. By acting both as a heat source and sink, water can buffer major temperature fluctuations. Large lakes and oceans generate even more marked modulation of the climate by significantly modifying airflow patterns (see Fig. 5.24).

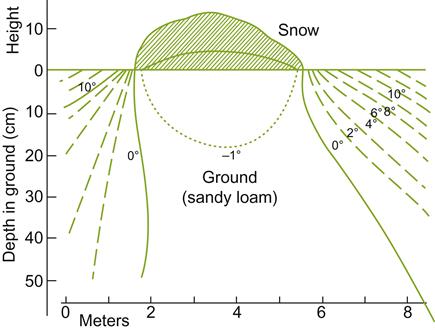

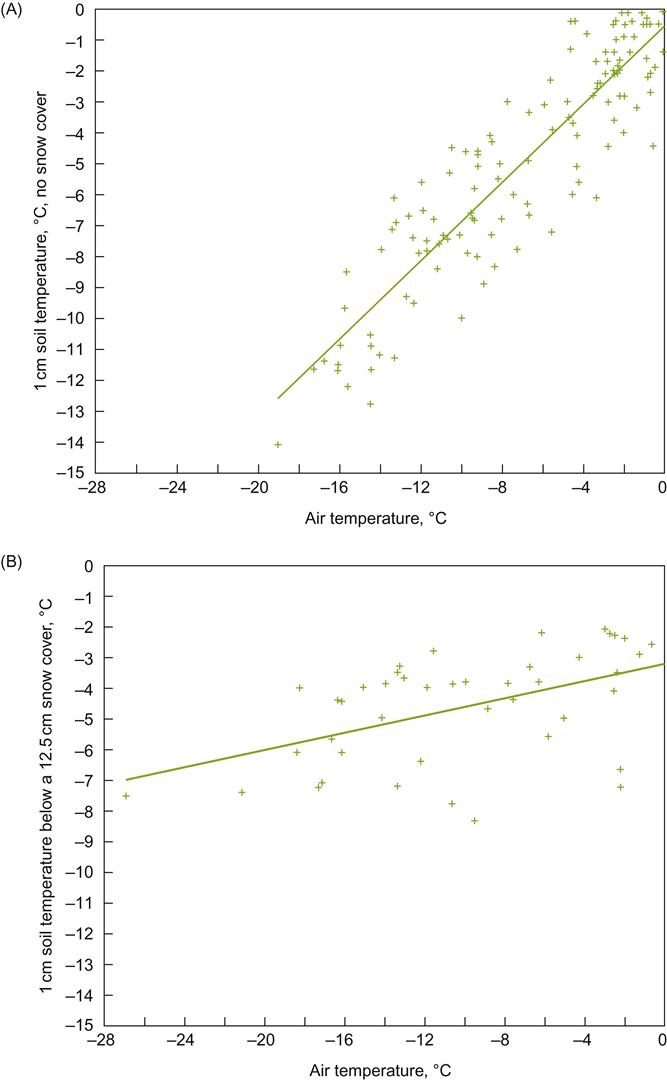

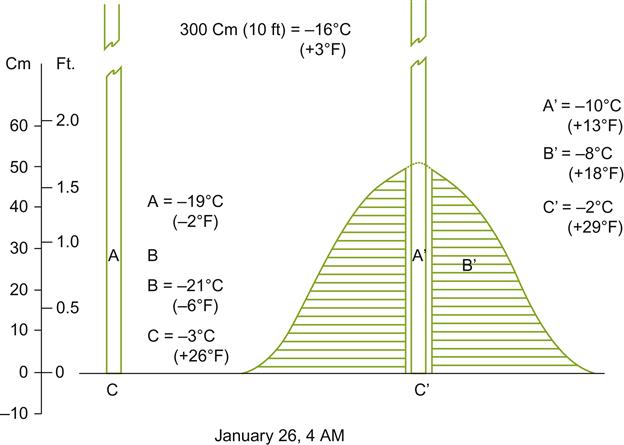

In regions frequently experiencing severe winter conditions, east- or west-facing slopes may be preferred. For example, in the Finger Lakes region of New York, south-facing slopes promote the early loss of an insulating snow cover. The insulating properties of snow are clearly evident in Figures 5.14 and 5.15. South-facing slopes may also increase the likelihood of bark splitting due to sudden fluctuations in temperature provoked by rapid changes in sun exposure, and the ‘black-body’ effect of dark-colored bark.

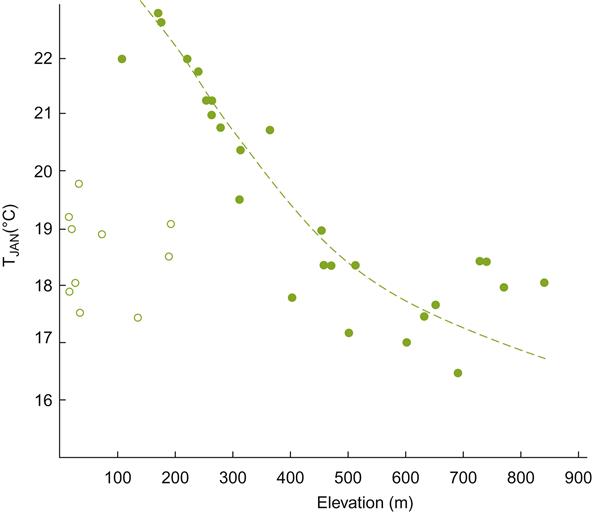

Altitude

The annual temperature (isotherm) tends to decrease by about 0.5°C/100 m elevation (Hopkin’s bioclimatic law). Thus, altitude can significantly affect grape maturation and growing season. This feature can be significantly enhanced or diminished by the relative proximity to large water bodies (Fig. 5.16; Kopec, 1967). Typically, lower altitudes are preferable at high latitudes, and higher altitudes more desirable at lower latitudes. The intensity of visible, and especially ultraviolet, radiation increases with altitude. These influences can, however, be substantially modified by local climatic features, notably the percentage and density of cloud cover.

Few direct investigations on the effects of altitude on grape and wine quality have been conducted. Thus, the data presented by Scrinzi et al. (1996) are of particular interest. They studied the effects of altitude and soil conditions on the characteristics of Sauvignon blanc wines in the alpine region of Trentino, Italy. From their investigation, they were able to make specific recommendations on vineyard location, relative to the flavor characteristics found in the wine. Mateus et al. (2001) also found clear correlations between altitude and the production and types of proanthocyanins accumulated by Touriga Nacional and Touriga Francesca in the Douro, Portugal. This has relevance to the classification of vineyards in the region (see Chapter 10).

Drainage

Because of erosion, soils on slopes tend to be coarsely textured. This provides better drainage, and permits soil surfaces to dry more quickly. Thus, less heat is expended in the vaporization of soil moisture from the surface, and sun-facing slopes warm more quickly. For example, it takes at least twice as much heat to raise the temperature of a moist soil compared with its dry equivalent.

Improved water drainage is primarily of advantage if the region has regular periods of excessive rainfall, thereby avoiding waterlogging. It can, however, be a disadvantage in arid conditions, facilitating water percolation and increasing the likelihood of water deficit development. Slopes also increase the potential for erosion and nutrient leaching. Correspondingly, soils at the top of a slope are typically comparatively thin and nutrient poor compared with soils on much of the slope and valley floor. Traditionally, this has required the periodic application of soil and manure to the slope. Enhanced drainage may also increase the potential for groundwater pollution from nutrients added as fertilizer.

As noted, drainage of cold air away from the vines can also significantly mollify the effects of either late-spring or early-autumn frosts.

Atmospheric Influences

Minimum Climatic Requirements

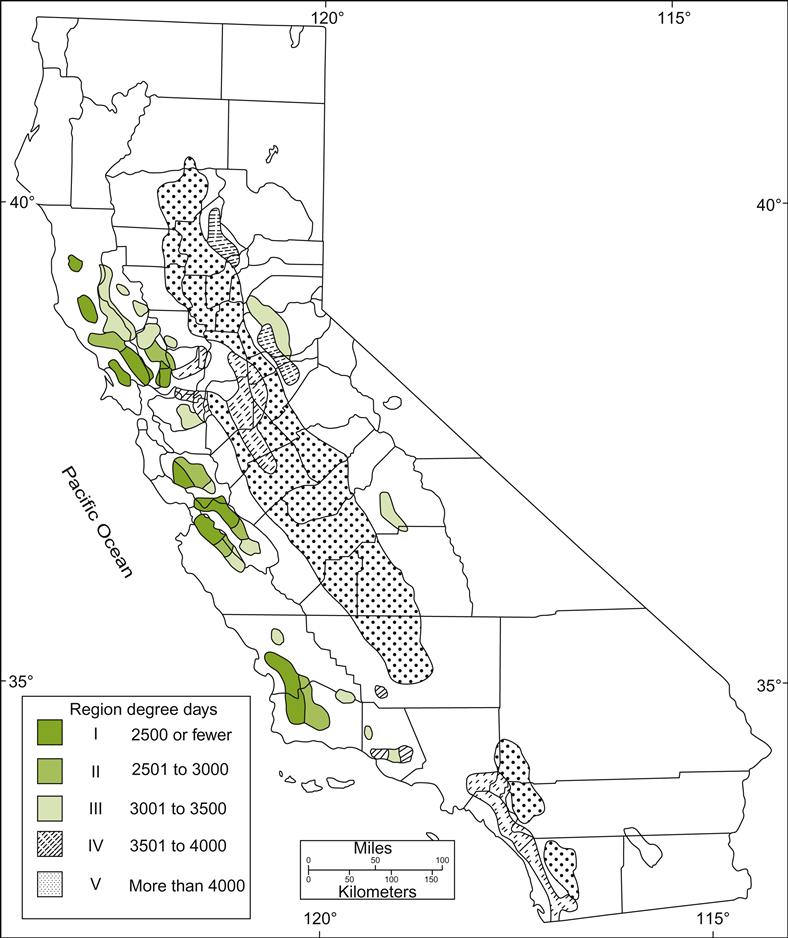

Historically, cultivars acclimated to a particular region were discovered empirically. How well they grew and the quality of the fruit indicated suitability. Improvements in measuring a region’s physical parameters have provided objective indicators of probable adaptation, and can be used to classify regions relative to varietal compatibility. The most well-known is the heat-summation system devised by Amerine and Winkler (1944). The units, called degree-days, are calculated for months having average temperatures above 10°C (50°F). For those months, a sum is calculated by multiplying the number of days in the month by their respective average temperatures (minus 10). For example, the corresponding degree-day values for days with average monthly temperatures of 15 and 25°C would be 5 and 15, respectively. The 10°C cut-off point was chosen because many of the standard varieties were thought not to initiate significant growth below this temperature. Using this system, they divided California into five climatic regions (Fig. 5.17). A comparison of the Winkler and Amerine viticultural climatic regions based on Celsius and Fahrenheit degree-day ranges is provided in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1

Comparison of viticultural climatic regions based on equivalent ranges of Celsius and Fahrenheit degree-days

| Region | Celsius degree-days | Fahrenheit degree-days |

| I | <1390 | <2500 |

| II | 1391–1670 | 2501–3000 |

| III | 1671–1940 | 3001–3500 |

| IV | 1941–2220 | 3501–4000 |

| V | >2220 | >4000 |

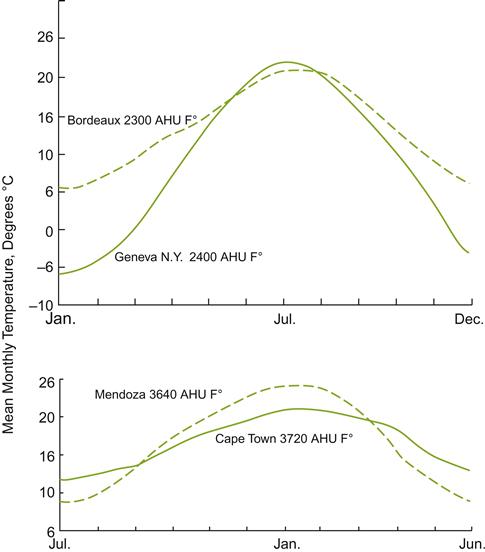

Since its introduction, the degree-day formula has been used widely in many countries. It tends to work well when comparing different sites in similar regions. However, it may give a false impression of similarity between disparate regions (Fig. 5.18), due to the regional significance of other climatic factors (McIntyre et al., 1987). Thus, it has not met with universal success, even in California. In an attempt to find a more generally applicable indicator, various alternative climate predictive models have been suggested. These have included the incorporation of parameters, such as humidity and water deficit, or modifications to the temperature formula. One of the modified formulas is the latitude-temperature index (Jackson and Cherry, 1988). It is calculated as the product of the mean temperature (°C) of the warmest month multiplied by 60 (minus the latitude). Another system plots sites in relation to the mean highest and lowest temperatures of the warmest month, and the lowest temperature of the coldest month (Bentryn, 1988). These systems have been used to predict precipitation patterns, latitude, and humidity, or the mean temperature and daily relative humidity of the warmest month. Tonietto and Carbonneau (2004) have presented a new worldwide climatic classification. It incorporates factors such as a cool night index (CI), a dryness index (DI), and Huglin’s heliothermal index (HI). Recently, a phenological model has been proposed to predict the timing of flowering and véraison (Parker et al., 2011).

Whether attempts to produce worldwide models are worth the effort is a moot point. All such schemes are only crude indicators at best, which is probably all that should be expected. In addition, meso- and microclimatic conditions are often of paramount importance in cultivar selection at the individual vineyard level. For example, regions affected by continental influences may have more than twice the average day–night temperature variation than an equivalent maritime region. Furthermore, differences in north–south slope orientation become increasingly important with increasing latitude.

In an attempt to obtain more sensitive indicators of local climatic conditions, some researchers have recommended use of floristic maps to determine cultivar–site compatibility (Becker, 1985b). Because of the marked climatic sensitivity of native plants, they can be amazingly accurate indicators of the long-term meso- and microclimatic conditions of a local area. In new undisturbed areas, the distribution of native plants may be a precise indicator of soil and climatic conditions across a site.

In long-established vineyard regions, there is little need for climatic models. Cultivar compatibility is already known. However, for new viticultural regions, the prediction of cultivar–site suitability can avoid expensive errors and replanting. For some Vitis vinifera cultivars, there are generally accepted, empirical data indicating minimum and preferred climatic conditions. For example, Becker (1985b) noted that cool-adapted cultivars typically require more than 1000 (Celsius) degree-days, a 180-day frost-free period, an average coldest monthly temperature not less than−1°C, temperatures below−20°C occurring less than once in 20 years, and an annual precipitation greater than 400–500 mm. Phenologic stages, such as bud burst, flowering, and fruit maturation, are also well established for several major cultivars (Galet, 1979; McIntyre et al., 1982). Unfortunately, similar data are not available for the majority of cultivars.

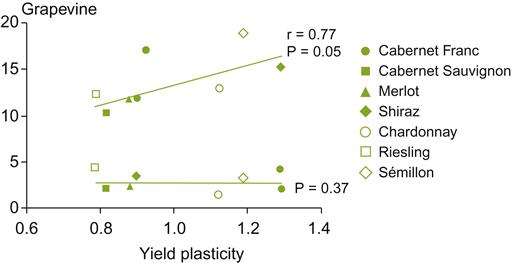

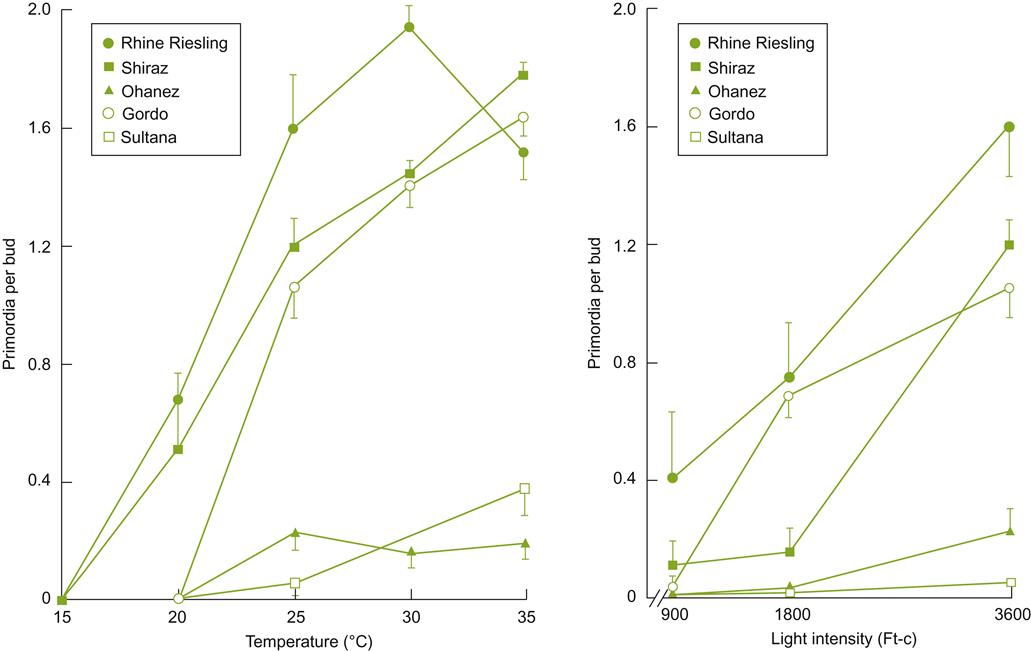

Phenological models were initially developed to assist in selecting cultivar/site combinations. Subsequently, their use has been extended to preparing disease prediction models; assisting in viticultural decisions relative to features such as the timing of bud burst, flowering, véraison, and maturity; and now, calculations of the effects of global warming. To develop more robust models, recent approaches are being based on individual components of grapevine physiology (Caffarra and Eccel, 2010). Data provided by Sadras et al. (2009) suggest that phenological responses, from bud burst to flowering, are much more informative as an indicator of cultivar plasticity than later stages. Cultivars differ markedly in their response to these parameters (Fig. 5.19). Whether these stages are equally significant indicators of the chemical attributes that generate wine quality has yet to be established.

Because the plasticity of cultivars to climatic variation can vary, the relevance of climatic indicators can be cultivar-specific. European beliefs relative to climate-cultivars' specificity are thus suspect. They have often been found too restrictive, based on the trial-and-error experience in New World viticultural regions.

As a whole, Vitis species grow over a wide range of climates, from the continental extremes of northern Canada, Russia, and China to the humid subtropical climes of Central America and northern South America. Nevertheless, most individual species are limited to a much narrower range of latitudes and environmental extremes (see Fig. 2.6). For Vitis vinifera, adaptation includes the latitude range between 35 and 50°N, including Mediterranean, maritime, and moderate continental climates (see Fig. 2.8). These are characterized by wet winters and hot dry summers, relatively mild winters and dry cool summers, and cold winters and warm summers with comparatively uniform annual precipitation, respectively.

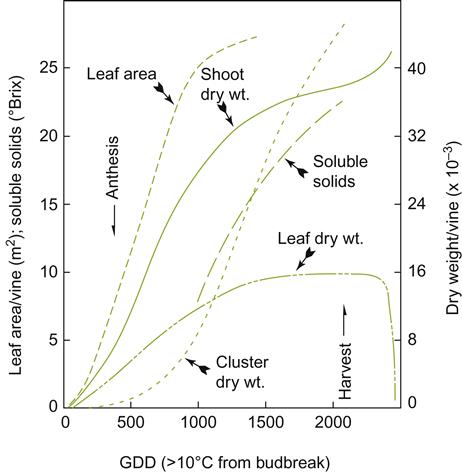

Temperature

Grapevine growth is markedly affected by site latitude and altitude, largely through their influence on the periodicity and intensity of solar radiation. It is equally influenced by annual temperature changes. One of the more recent demonstrations of the subtlety of these influences can be seen in the effect of climate warming. The duration between budbreak and harvest appears to shorten by about 8 d/1°C climate warming, with this being most evident in early ripening varieties (Tomasi et al., 2011). Another example is the season-long effect of warm spring temperatures on shoot development (Keller and Tarara, 2010).

The major impact of temperature is also seen in the predominant influence of cooling autumn temperatures on cold acclimation, not, as in many other plants, the shortening of the photoperiod. The loss of endogenous dormancy in buds does not require a specific cold treatment, but is facilitated by exposure to cold temperatures (see Fig. 3.7). In contrast, activation of bud growth (termination of exogenous, environment-induced dormancy) responds progressively to temperatures above a cultivar-specific minimum (Moncur et al., 1989). Above this temperature, budbreak and other phenological responses become increasingly rapid, up to an optimum temperature (Fig. 5.20). This type of response suggests that temperature control is relatively nonspecific, and functions through its effects on the shape or flexibility of specific regulator proteins and cell-membrane lipids. This interpretation is strengthened by the nonspecific enhancement of cellular respiration during budbreak by a diverse range of treatments (Shulman et al., 1983). Up to a maximum value, every 10°C increase in temperature tends to double the reaction rate of biochemical processes. However, as different cellular reactions have dissimilar temperature–response curves, overall vine response depends on the combined effects of temperature on multiple reactions.

The slow activation of bud growth in the spring may reflect the ancestral trailing-climbing habit of the vine. For several cultivars, the average minimal temperature for budbreak and leaf production are 3.5 and 7.1°C, respectively (Moncur et al., 1989). Delay in grapevine budbreak permitted potential shrub and tree supports to partially produce their foliage, before the vine commenced its growth. Thus, the vine could position its leaves optimally for light exposure, relative to the foliage of the support plant. During the remainder of the growing season, lateral bud activation appears to be regulated by growth substances, notably auxins, released from apical meristematic regions. This plasticity, and the vine’s indeterminate growth habit, permit the vine to respond to favorable environmental conditions, or foliage loss, throughout much of the growing season.

Temperature has substantial and critical effects on both the duration and effectiveness of flowering and fruit set. Flowering typically does not occur until the average temperature reaches 20°C (18°C in cool regions). Low temperatures slow anthesis, as well as pollen release, germination, and pollen-tube growth. For example, pollen germination is low at 15°C, but high at 30–35°C (see Fig. 3.26). Style penetration and fertilization may take 5–7 days at 15°C, but only a few hours at 30°C (Staudt, 1982). If fertilization is delayed significantly, ovules abort. Cold temperatures slowly reduce pollen viability.

Although pollen germination and germ tube growth are favored by warm temperatures, optimal fertilization and subsequent fruit set become progressively poorer as temperatures rise above 20°C. Ovule fertility, seed number per berry, and berry weight are greater at lower than at high temperatures. Even soil temperature can affect vine fertility; for example, cool soil temperatures tend to suppress budbreak but enhance the number of berries produced per cluster (Kliewer, 1975).

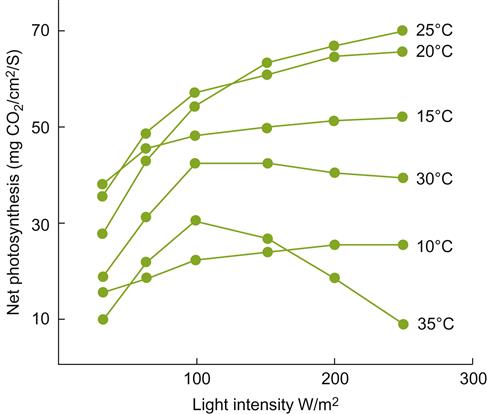

Temperature conditions affect the photosynthetic rate, but they are not known to dramatically influence overall vine growth under normal conditions. In fact, leaves partially adjust to seasonal temperature fluctuations by slightly changing their optimal photosynthetic temperature. In midsummer, the optimal range generally varies between 25 and 32°C, but may decline to 22–25°C by autumn (Stoev and Slavtcheva, 1982).

For centuries, it has been known that temperature has a pronounced effect on berry ripening and quality. This is the basis of the degree-day formula for site selection. Temperature also differentially affects specific reactions that occur during berry maturation. Consequently, fruit composition and potential wine quality can be significantly affected by both average and extreme temperatures.

Higher temperatures generally result in increased sugar levels, but reduced malic acidity. Because taste, color, stability, and aging potential are all influenced by grape sugar and acid contents, temperature conditions throughout the season have a prominent effect on delineating grape quality at harvest. Based on the sugar and malic acid contents, the optimal temperature range for grape maturation lies between 20 and 25°C; for anthocyanin synthesis, slightly cooler temperatures may be preferable (Kliewer and Torres, 1972). Daytime temperatures appear to be more important than night-time temperatures, relative to pigment formation. Although moderate temperature conditions often favor fruit coloration, cool temperatures limit the commercial cultivation of red varieties due to poor coloration.

Surprisingly little research has been conducted on the generally held view that cool temperatures favor varietal aroma development in grapes. Cool temperatures do increase the frequency of vegetable odors in Cabernet Sauvignon, whereas berry aroma formation was favored under warmer conditions (Heymann and Noble, 1987). With Pinot noir, several aroma compounds appear to be produced in higher amounts during long cool seasons compared with early hot seasons (Watson et al., 1988). The distinctive character of Marlborough Sauvignon blanc wines from New Zealand has often been attributed to the marked diurnal temperature fluctuations of the region.

Chilling and Frost Injury

Although cooler sites may be beneficial in warm to hot climatic regions, prolonged exposure to temperatures below 10°C can induce irreversible physiological damage, retarding ripening (Becker, 1985a). This type of damage, called chilling injury, is usually reversible when of short duration. Injury apparently results from the excessive gelling of the semifluid cell membrane. This reduces cellular control over membrane permeability, resulting in electrolyte loss and the disruption of respiratory, photosynthetic, and other cellular functions (George and Lyons, 1979; Bertamini et al., 2005). In addition, several plant enzymes may be irreversibly denatured by cool temperatures, for example chloroplast ATPase and RuBP carboxylase. Sensitive species are generally characterized by higher proportions of saturated fatty acids in their cell membranes. Saturated fatty acids maintain appropriate membrane fluidity at high temperatures, but make the membrane overly rigid at cool temperatures. In some plants, exposure to cool temperatures increases the proportion of linolenic acid (an unsaturated fatty acid) in cellular membranes, increasing fluidity.

Cool temperatures also enhance the potential for dew formation, by raising atmospheric relative humidity (lowering the water-holding capacity of air). Dew on vine surfaces can increase the frequency and severity of several fungal diseases.

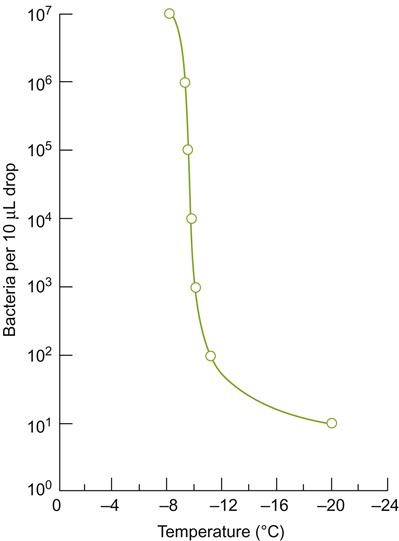

Although pure water melts at 0°C, the actual freezing point on plant surfaces varies depending on the presence of solutes and ice-nucleation sites. The latter usually involves the presence of epiphytic, ice-nucleating bacteria. They release proteins that by unknown mechanisms favor heterogenous crystallization of surface moisture. Ice crystallization can spread into plant tissues through surface cracks or stoma (Wisniewski and Fuller, 1999). Additional nucleation sites may also form intrinsically within plant tissues. As ice crystals develop within intercellular spaces and cell walls, water diffuses (or sublimes) out of the cytoplasm to replace the extracellular water that crystallizes. The resulting dehydration induces cytoplasmic shrinkage, as the plasma membrane pulls away from the cell wall. Both are a consequence of increased protoplasmic concentration and osmolarity. This, in turn, initiates protein and nucleic acid denaturation. If the tissues are not sufficiently cold acclimated, these changes can create irreversible damage, causing cell death (Guy, 2003). The degree of dehydration that results depends largely on the osmotic potential of the cell – the lower the osmotic potential, the less likely the chance of damaging dehydration. In addition, the reduced osmotic potential partially explains the enigmatic phenomenon of supercooling (Wisniewski and Arora, 1993).

If heat continues to be lost from the tissue, water in larger xylem vessels begins to freeze, provoking further dehydration. At a certain point, the supercooled water begins to crystallize, inducing irreparable cytoplasmic damage. This is thought to result from cellular membrane puncturing, as ice crystals form and enlarge intracellularly. On a molecular level, the precise sequence of events leading to cell death remains unclear. Further damage may result from tissue deformation, caused by differential expansion of the phloem and xylem (Meiering et al., 1980).

The degree of disruption often depends as much on the rate of cooling or subsequent thawing, as on the minimum temperature reached. If the temperature falls rapidly, extracellular water crystallization occurs more rapidly than water can diffuse out of the cytoplasm. As a result, the cytoplasm has little chance to supercool sufficiently quickly to avoid intracellular crystallization. Rapid thawing can be as damaging as rapid temperature drops.

The stem tissues most sensitive to winter and spring cold damage are those of the primary bud (Plates 5.1 and 5.2), followed by the phloem and cambium of the bearing wood. Xylem tissue is the least vulnerable, but can be damaged, typically starting at the pith and moving outward. Pool (2000) and Goffinet (2004) present beautifully illustrated articles on the anatomical damage caused by freezing in the winter and spring, respectively.

If damage to woody tissues is limited, there may be recovery. This involves undamaged cells in the region dedifferentiating into embryonic cells. They form callus tissue from which new cambial and subsequently phloem and xylem cells develop. The rapidity of recovery depends on the extent to which nutrient flow can occur in the shoot. If severely disrupted, bud growth and development are poor. Inadequate hormonal stimuli from the shoot apex can also retard development of new vascular tissue. Full recovery, if it occurs, can take months.

During the autumn and winter months, vine tissues progressively develop a degree of freeze tolerance, termed cold acclimation. It is associated with, but usually after, the development of endogenous dormancy in the buds (Welling and Palva, 2006). The rate of cold acclimation appears to be time- and temperature-dependent (shorter periods at cold temperatures being equivalent to longer exposure at less frigid temperatures).

Xylem vessels, being nonliving, can withstand considerable ice crystal formation. Nevertheless, as winter approaches, water flow ceases and xylem vessels evacuate. This increases their relative insensitivity to cold damage. In the phloem, callose builds up at the cell plates, inhibiting nutrient and water flow. In buds, pectinaceous material appears to isolate the bud from shoot vascular tissues (Jones et al., 2000). Anatomical features (Goffinet, 2004) are also thought to severely restrict the migration of water crystallization into buds from the shoot. Supercooling in bud cells further diminishes the likelihood of intracellular ice formation. This has been associated with increased levels of soluble sugars (Wample and Bary, 1992), oligosaccharides of the raffinose group (Hamman et al., 1996), concentrations of proline (Aït Barka and Audran, 1997), and partial tissue dehydration (Wolpert and Howell, 1985). All of these features decrease the osmotic potential and freezing point of the sap and, correspondingly, reduce the likelihood of ice-crystal formation in the cytoplasm. In addition, there is the synthesis of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA)-like proteins in bud tissue (Salzman et al., 1996). In other plants, dehydrins (a subgroup of LEA proteins) are known to protect several enzymes and cellular membranes from frost damage. Other changes modify the lipid composition of membranes (Moellering et al., 2010), providing a degree of cold tolerance. Finally, many organisms are known to produce extracellular antifreeze proteins (Griffith and Antikainen, 1996). Acclimation is especially marked in the vascular tissue and dormant buds. These tissues eventually can withstand temperatures down to−20°C or below.

Cold acclimation is speculated to have evolved from responses to high salinity and drought (Guy, 2003). The molecular changes involved are similar to those that developed in response to osmotically related stress reactions.

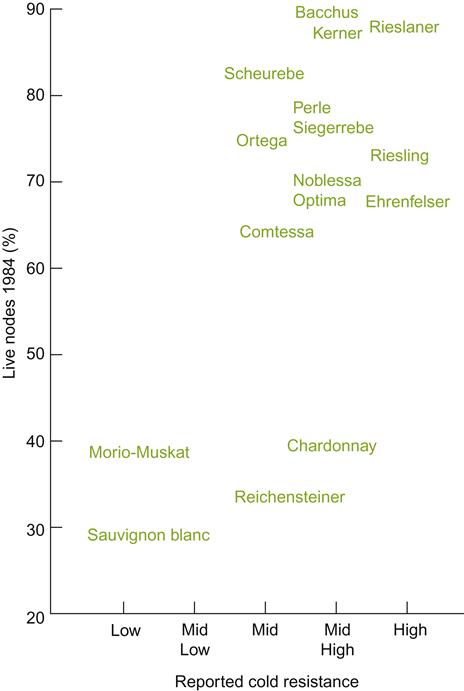

Frost tolerance varies markedly among V. vinifera cultivars (Fig. 5.21), as well as Vitis species (Table 5.2). For example, Riesling, Gewürztraminer, and Pinot noir are relatively winter hardy, being able to withstand short exposures to temperatures down to−26°C (when the vines are fully acclimated). Varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Sémillon, and Chenin blanc possess moderate hardiness, suffering damage at−17 to−23°C. Grenache is considered tender and may suffer severe damage at−14°C. Vitis labrusca and French-American hybrid cultivars are relatively cold hardy, and some V. amurensis hybrids can survive prolonged exposure to temperatures well below−30°C.

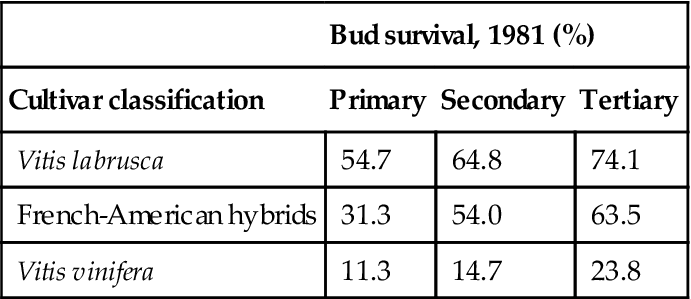

Table 5.2

Cultivar classification and bud survival after minimum temperatures of−20 to−30 °C on December 24, 1980

| Bud survival, 1981 (%) | |||

| Cultivar classification | Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

| Vitis labrusca | 54.7 | 64.8 | 74.1 |

| French-American hybrids | 31.3 | 54.0 | 63.5 |

| Vitis vinifera | 11.3 | 14.7 | 23.8 |

From Pool and Howard, 1985, reproduced by permission.

Winter-hardiness is a complex factor and inadequately represented by the minimum temperature a cultivar can withstand. Cold-hardiness is influenced by many genetic, viticultural, and environmental conditions. In addition, various parts of the vine show differential sensitivity to frost and winter damage. In the dormant bud, the most differentiated (primary) bud is the most sensitive whereas the least differentiated (tertiary bud) is the most cold-hardy. Buds and the root system are generally less winter-hardy than old wood. Soil structure and snow cover further influence vine response. These features affect the rate and depth of frost penetration during the winter (see Fig. 5.15) and thawing in the spring. Frost penetrates deeper in rough textured soils, but thaws more quickly. The reverse is the situation in moist, organic soils (Kreutz, 1942). For roots, cold sensitivity is probably associated with their lower sugar and higher moisture contents.

Although cold-hardiness is primarily a physiological property, anatomical features influence frost sensitivity. For example, hardy rootstocks generally have less bark tissue, containing relatively small phloem and ray cells, and possess woody tissues with narrow xylem vessels. In addition, winter-hardy rootstocks appear to increase the resistance of the scion to cold damage. This may result indirectly from factors such as restrained scion vigor, modified synthesis of growth regulators, and earlier limitation of water availability.

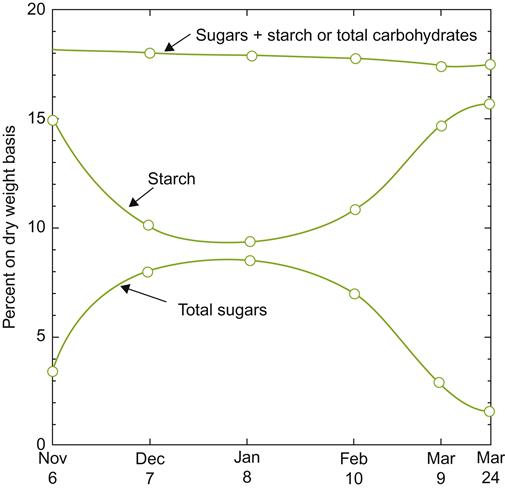

In general, small vines have been considered more cold-tolerant than large vines, apart from where vine size is restricted by stress factors such as disease, overcropping, or lime-induced chlorosis. Although this view has been challenged (Striegler and Howell, 1991), there is little doubt that late-season growth prolongs cellular activity and delays cold acclimation. This may develop because of growth-regulator or nutrient influences. Reduced carbohydrate accumulation could limit supercooling. During cold acclimation, starch is hydrolyzed to oligosaccharides and simple sugars (Eifert et al., 1961; Fig. 5.22). Fluctuations in the levels of glucose, fructose, raffinose, and stachyose are particularly associated with cold-hardiness in Chardonnay and Riesling (Hamman et al., 1996). Such changes affect the osmotic potential of the cytoplasm and correspondingly the freezing point.

The ability of surviving buds to replace winter-killed tissues is often crucial to commercially viable viticulture in cool climates. The tendency of the base buds of French-American hybrids to burst and develop flowering shoots often compensates for periodic severe winter damage. Even some V. vinifera cultivars, such as Chardonnay and Riesling, can withstand severe (80–90%) bud kill, and produce a substantial crop from activation of the remaining buds (Pool and Howard, 1985); hence the need for adequate bud retention on well-matured canes for producing profitable yields in cold viticultural regions.

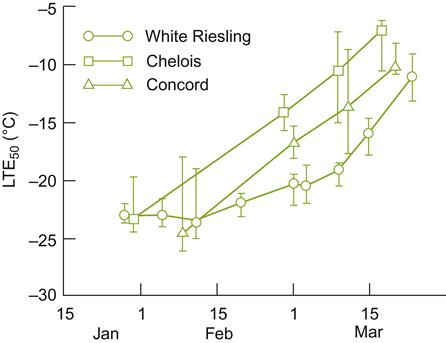

The rates of cold acclimation and deacclimation can also be decisive to varietal success. With several cultivars, such as Concord (V. labrusca), Chelois (French-American hybrid), and Riesling (V. vinifera), winter-hardiness is inversely proportional to the rate of deacclimation during the winter (Fig. 5.23).

Bud cold acclimation is often assessed in terms of the depression in a tissue’s low temperature exotherm1 (LTE) (Mills et al., 2006). Freezing can be directly viewed with a high-resolution, infrared thermography camera (Wisniewski et al., 2008). As cold acclimation is influenced, albeit slightly, by the rootstock, appropriate rootstock choice may augment commercial viability in particular sites (Miller et al., 1988). Because rapid temperature change is often particularly destructive, the frequency of rapid temperature fluctuations can be more limiting than the lowest yearly temperature.

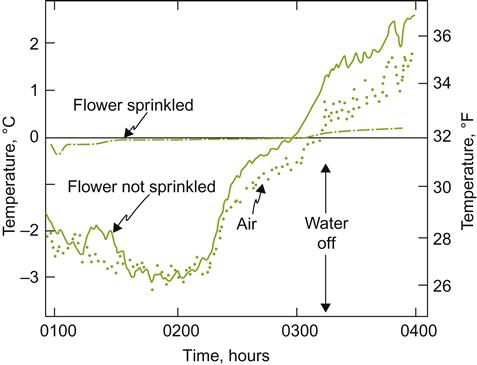

Minimizing Frost and Winter Damage

In an ideal world, vineyards would be situated in locations devoid of damaging frosts. However, avoiding frost-prone regions is often unrealistic. Thus, assessing the likelihood of frost and winter damage, and preparing strategies for their limitation, is often an unavoidable necessity. If the vineyard is distant from a regional meteorological station, on-site data, collected over several seasons, may show whether there is a strong correlation with regional averages and local vineyard conditions. Because the cost-effectiveness of preventive measures varies considerably, the type, timing (relative to budbreak, shoot development, and fruit maturity), and likely severity of damage are the best indicators for selecting among the multiple options. Where such data are not already available, climatic/phenological models such as Moncur et al. (1989) may be helpful. For examples of approaches to risk assessment see Trought (2004) and Zironi et al. (2002). Regrettably, lack of understanding of what induces freezing under any specific set of circumstances still makes choosing the most appropriate option problematic. Nonetheless, the least expensive option, but also the least practical, is to choose a site where frost occurrence is infrequent and passive avoidance likely.

For frost protection, choices can vary depending on whether the most frequent damage is caused by advective or radiative frost. Advective frost results from the inflow of cold air, whereas radiative frost develops as heat is lost to the sky on cool, still nights.