Vineyard Practice

Coverage begins with an outline of the vine’s annual growth cycle and its relevant vineyard activity. This leads into vine management, including: a discussion of the yield/quality ratio; pruning and training options; row spacing and orientation; canopy and vigor management; major pruning/training systems; rootstocks; grafting and propagation; and vineyard establishment. There is a brief diversion into Roman viticultural practice and its ‘modernness.’ This is followed by an investigation of practices such as irrigation and fertilization (both organic and inorganic), as well as their relative requirements, benefits, and problems. Disease, pest, and weed control are explored, both in general terms and as applied to specific vine disorders (both biologic and environmental), including their consequences on fruit quality. Subsequently, harvest is discussed in terms of the criteria used, sampling techniques, and collection procedures and their relative benefits. The chapter concludes with an exploration of vineyard variability, its detection, and the advantages of uniformity.

Keywords

grapevine growth cycle; yield/quality ratio; training; pruning; vigor management; grafting; grapevine disorders; grape harvest; vineyard variability

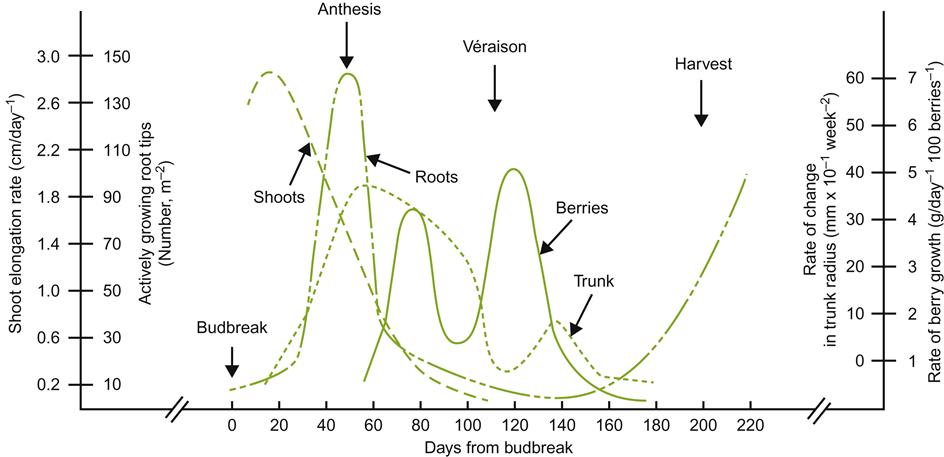

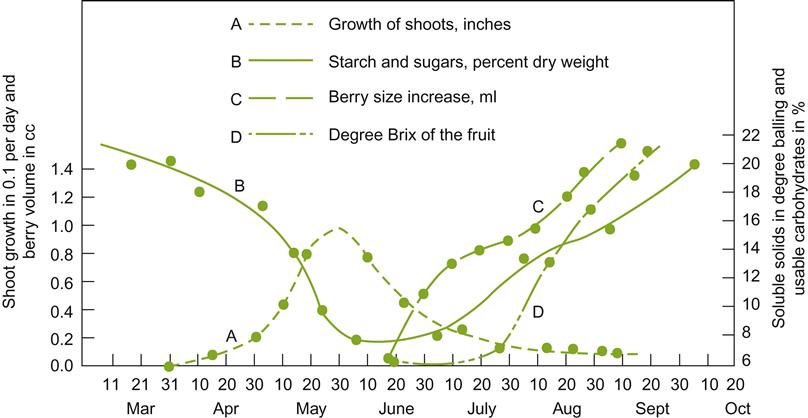

In Chapter 3, details were given concerning grapevine anatomy and physiology. In this chapter, vineyard practice, and how it impacts grape yield and quality are the central foci. Because vineyard practice is so closely allied to the yearly cycle of the vine, a brief description of this cycle and its association with vineyard activities is given below. Many of these aspects are illustrated in Fig. 4.1.

Vine Cycle and Vineyard Activity

The end of one growth cycle and preparation for another coincides, in temperate regions, with the onset of winter dormancy. Winter dormancy provides grape growers the opportunity to do many of the less urgent vineyard activities for which there was insufficient time during the growing season. In addition, pruning is conducted more conveniently when the vine is dormant – the absence of foliage permitting easier wood selection and cane tying.

With the return of warmer weather, both the metabolic activity of the vine, and the pace of vineyard endeavors quicken. Usually, the first sign of renewed activity is the ‘bleeding’ of sap from cut ends of canes or spurs. Hydrolysis of stored starch generates the turgor pressure that induces the early, upward flow of sap. The sap in spring contains organic constituents, such as sugars and amino acids (Campbell and Strother, 1996), as well as growth regulators, inorganic nutrients, and trace amounts of other organic compounds. These are critical to bud reactivation and initial growth. Reactivation of sap flow is reflected in a marked decrease in root and trunk carbohydrate reserves (Bennett et al., 2005). Between bud burst and 50% bloom, root starch and sugar reserves may decline by about 42 and 72%, respectively. Soluble sugars in the trunk can decline by 92% during the same period. These levels usually return to near winter values by leaf fall. When temperatures rise above a critical value, which depends on the variety, buds begin to burst. Bud activation progresses downward from the tips of canes and spurs, as the phloem regains its functionality. The cambium subsequently resumes its meristematic activity, producing new vascular tissues.

Typically, only the primary bud in the overwintered bud develops. The secondary and tertiary buds remain inactive, unless the primary bud has been killed or severely damaged. Once initiated, shoot growth rapidly reaches its maximum, as the climate continues to warm (Fig. 4.1). Development and enlargement of the primordial leaves, tendrils, and inflorescence clusters recommence (Fig. 4.2). As growth continues, the shoot differentiates new leaves and tendrils. Simultaneously, new buds begin to form in the leaf axils. Those that form early may give rise to lateral shoots.

Root growth typically lags behind shoot growth, often coinciding with flowering (five- to eight-leaf stage). Peak root development commonly occurs between the end of flowering and the initiation of fruit coloration (véraison). Subsequently, root development slows, with a possible second growth spurt in the autumn. Despite these trends, details can vary considerably with the rootstock, water availability, and climatic conditions.

Flower development in the spring progresses from the outermost ring of flower parts (the sepals) inward to the pistil. By the time the anthers mature and split open (anthesis), the cap of fused petals (calyptra) separates from the ovary base and is shed. In the process, self-pollination typically results as liberated pollen falls onto the stigma. If followed by fertilization, embryo and berry development commence.

Concurrent with flowering, inflorescence induction may begin in the nascent primary buds of leaf axils. These typically become dormant by mid-season, completing their development only in the subsequent season.

Several weeks after bloom, many small berries dehisce (shatter). This is a normal process in all varieties, reflecting flowers in which fertilization was unsuccessful, or the embryos aborted. Except in seedless cultivars, at least one seed is required for complete berry development.

Once shoots have developed sufficiently, they are normally tied to, or restrained by, a support system. Shoots developing from old wood on the trunk are removed. Application of disease and pest control measures commence, if these have not already begun. Irrigation, when required, and if permissible, is applied. It is usually restricted between véraison and full maturity. The latter avoids promoting continued vegetative growth after véraison. It can also negatively affect fruit maturity and quality. If necessary, irrigation may be reinitiated after harvest to avoid stressing the vine and to favor optimal cane maturation.

When berry development has reached véraison, primary shoot growth has usually ceased. Shoot topping may be practiced if primary or lateral shoot growth continues, or to facilitate machinery movement in dense plantings. Fruit-cluster thinning may be performed if potential fruit yield appears excessive. Flower-cluster thinning, early in the season, can achieve the same result. Basal leaf removal may be employed to improve cane and fruit exposure to light and air, as well as to facilitate access to disease- and pest-control agents.

As the fruit approaches maturity, vineyard activity shifts toward preparing for harvest. Fruit samples are taken throughout the vineyard for sensory and chemical analysis. Based on the results, environmental conditions, and the desires of the winemaker, a tentative harvest date is set. In cool climates, measures are put in place for frost protection, similar to those that may have been required in the spring to protect from late frost.

Once harvest is complete, vineyard activity is directed toward preparing the vines for winter. In cold climates, this may vary from mounding soil up around the shoot–rootstock union, to removing the whole shoot system from its support system for burial. In warmer climates, it entails protection of the foliage until abscission. Leaves may remain functional for several months after harvest, or continuously in tropical regions.

Management of Vine Growth

Vineyard practice is primarily directed toward obtaining the maximum yield of fruit of the desired quality. One of the major means of achieving this goal involves training and pruning. Thus, both have been extensively analyzed for at least a century, and observed empirically for millennia. The result is a bewildering array of systems. Although a full discussion of this diversity is beyond the scope here, the following provides an overview of the sources of its heterogeneity. For descriptions of local training and pruning systems, the reader is directed to regional governmental publications, universities, and research stations. However, before discussing vine management, it is advisable to define several commonly used terms.

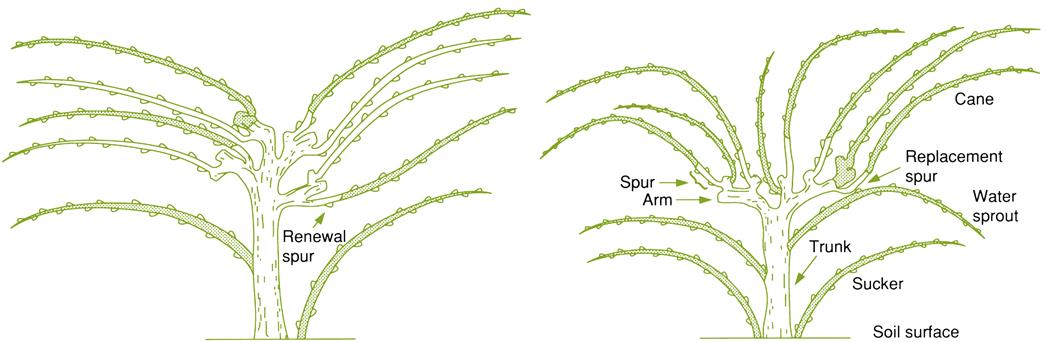

Training refers to the development of a permanent vine structure and the location of renewal wood. It is intended to position shoot growth in an environmentally favorable location. Renewal spurs often consist of short cane segments, retained as sources of new canes (bearing wood), from which fruit-bearing shoots may originate (see Fig. 4.11). Alternatively, spurs are used to reposition bearing wood closer to the head or cordon (replacement spurs). Training usually is associated with a support (trellis). Training ideally takes into consideration factors such as the prevailing climate, harvesting practices, and the fruiting characteristics of the cultivar.

Canopy management is generally viewed as positioning and maintaining bearing (growing) shoots and their fruit in a microclimate optimal for grape quality, inflorescence initiation, and cane maturation.

Pruning may involve the selective removal of canes, shoots, wood, and leaves, or the severing of roots to obtain the goals of training and canopy management. Thinning comprises the removal of whole or parts of flower and fruit clusters to improve the berry microclimate and leaf area/fruit balance. However, pruning most commonly refers to the removal of unnecessary shoot growth at the end of the season.

Finally, vigor refers to the rate and extent of vegetative growth, whereas capacity denotes the amount of growth and the vine’s ability to mature fruit.

Yield/Quality Ratio

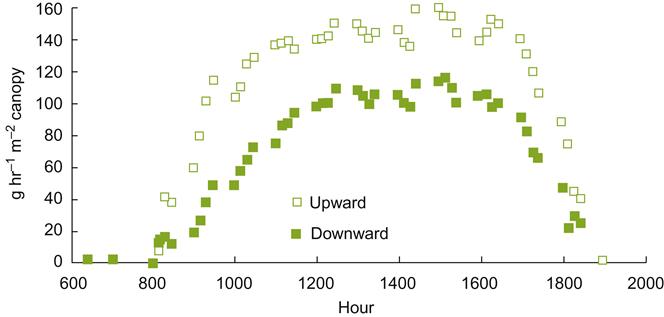

Central to all vine management systems is regulation of the yield/quality ratio. This is largely a function of the photosynthetic surface area (cm2) to fruit mass (g). It provides an indicator of the vine’s capacity to ripen the fruit. The leaf area/fruit (LA/F) ratio is related to the more familiar concept of yield per hectare. However, the LA/F ratio focuses directly on the fundamental photosynthate source/sink relationship.

The first to publish extensively on this relationship was Winkler (1958). Regrettably, application of the LA/F ratio is limited by the absence of a simple, rapid means of obtaining the requisite data (Tregoat et al., 2001). Suggestions by Lopes and Pinto (2005), Blom and Tarara (2007), Tsialtas et al. (2008), Beslic et al. (2010), and Guisard et al. (2010) are attempts to provide more effective means of assessing leaf area. Multispectral remote sensing (Johnson et al., 2003) also has potential as it can be readily correlated with field data. In addition, Costanza et al. (2004) and Siegfried et al. (2007) have shown a strong correlation between shoot length and leaf area. There is also the need for more accurate, continuous measures of potential yield. With these, real-time data for the application of LA/F ratio predictions in practical viticultural should be possible.

Appropriate and practical interpretation of the data include the effects of nutrient and water status, temperature and light conditions, disease pressures, and pruning and training systems on photosynthetic efficiency and carbohydrate shunting throughout the vine. For example, LA/F values between 8 and 12 cm2/g and 5 and 8 cm2/g were obtained for single- and divided-canopy systems (Kliewer and Dokoozlian, 2005). Increasing shoot numbers decreases the LA/F ratio (Myers et al., 2008). Ratios to fully ripen the fruit can vary between 7 and 14 cm2/g. In addition, the relationship tends not to be linear, becoming increasing negative as the ratio falls below a broad acceptable range (Kliewer and Dokoozlian, 2005).

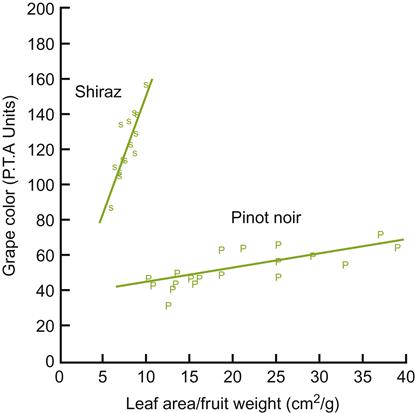

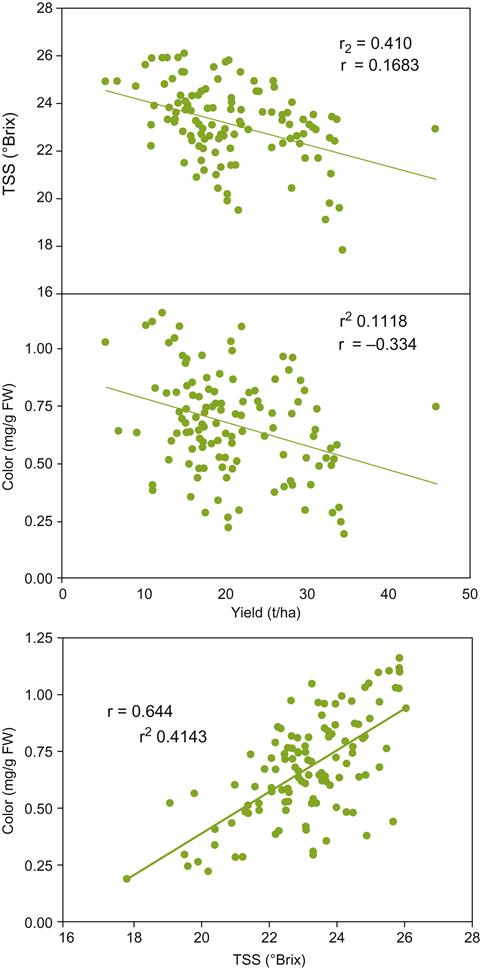

Another source of variability involves cultivar response (Fig. 4.3). For most effective use, the values derived should incorporate data only from leaves significantly contributing to vine growth (eliminating young, old, and heavily shaded leaves). When data from different canopy configurations are compared, variations in the proportion of exterior to interior leaf canopy must be considered.

A simplistic view would suggest that an increased leaf area should directly correlate into an increased ability to produce additional, fully ripened fruit. However, the grapevine is an uncommonly complex and adaptive plant. In addition, the fruit-bearing capacity of the current year’s growth is largely defined in the previous year. Most of the flower clusters of the current season were initiated within a 4-week period, bracketing the blooming of the past season’s flowers. Thus, as typical with other perennial crops, conditions in the previous year place outer limits on the current season’s crop. This is particularly marked in cool climatic regions, where seasonal variations are often pronounced. Nutrient availability and growth may also be markedly influenced by vine health, and the ability to store nutrients during the previous year.

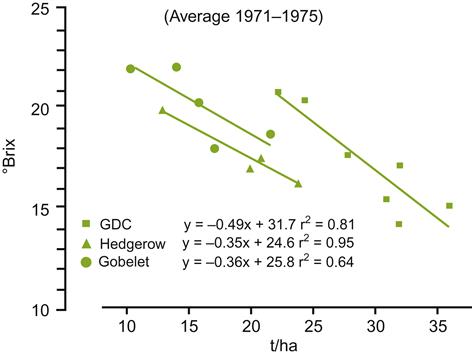

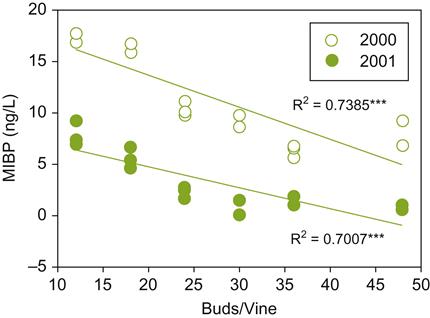

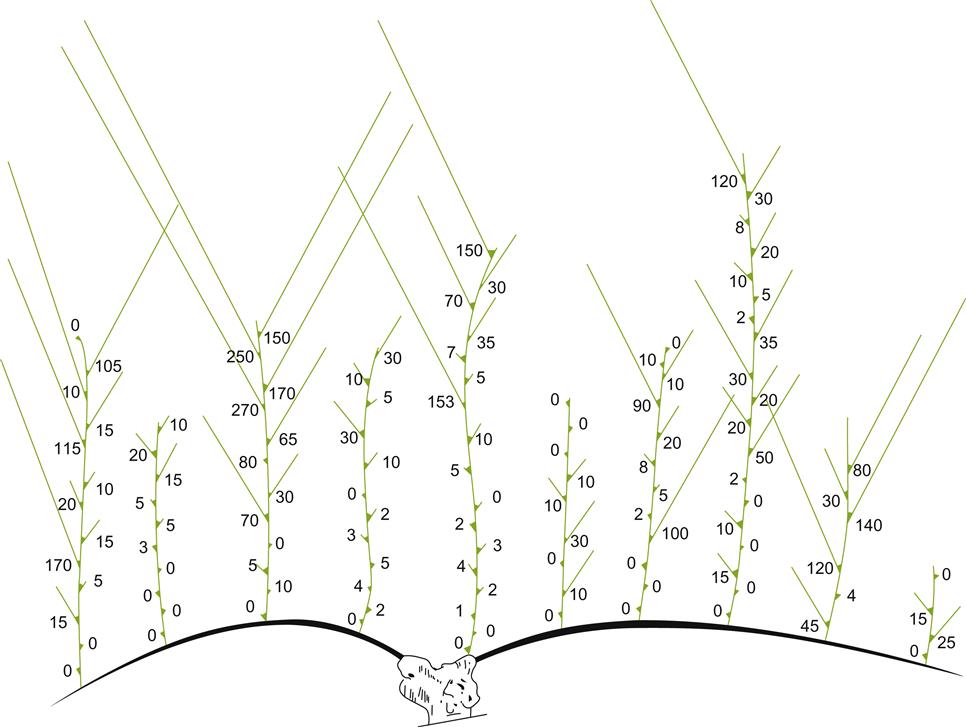

Another problem with simple yield/quality associations is the potential of some cultivars to produce several shoot sets per year. Lateral shoots, and any clusters they produce, not only retard ripening of the primary fruit, but also reduce overall uniformity at harvest. Induction of a second (or third) crop can be caused by overly zealous pruning, especially on fertile, moist soils. In contrast, heavy pruning of vines grown on comparatively nutrient-poor dry soils can direct photosynthetic capacity to fully ripen a restricted fruit load. Figure 4.4 illustrates how different training systems affect the yield/°Brix ratio. There can also be marked variation between individual vines (Fig. 4.5), sites, or vintages (Plan et al., 1976). Sensory quality may actually decrease with reduced yield, by enhancing the presence of undesirable flavorants (Fig. 4.6) and diminishing varietal aroma (Chapman et al., 2004a). Thus, a universal relationship between vine yield and grape (wine) quality does not exist. Life (or the vine) is not that simple.

The desire for a universal yield/quality ratio is especially in jeopardy when pruning techniques developed for dry low-nutrient hillside sites are applied to vines grown on moist, nutrient-rich lowland sites. Severe pruning may spur excess vegetative growth, rather than limiting it. Nutrients are directed to shoot growth, and dormant buds activated; this can result in increased shading, enhanced disease incidence, and delayed and nonuniform fruit maturation. Furthermore, cool climatic conditions provide less opportunity for the vine to compensate for temporary poor conditions, in contrast to the extended growing season and higher light intensities that typify warmer Mediterranean climates (Howell, 2001).

The important question is not whether there is some ideal yield/hectare ratio, but what is the optimal canopy size and placement to adequately nourish the crop to an optimal state of ripeness. Insufficient leaf surface can be as detrimental to quality as is excessive cover.

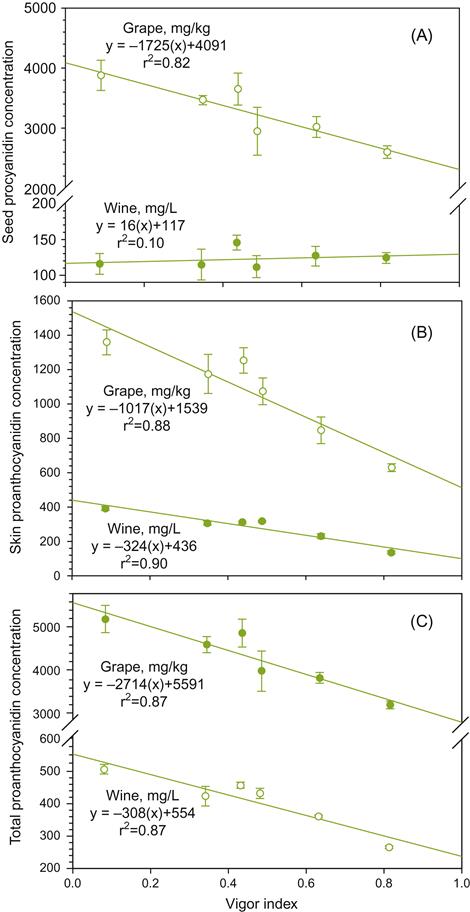

A centuries-old view holds that when vines are grown on relatively nutrient-poor soils, and experience moderate water limitation, the potential for vigorous growth is restrained and fruit ripens optimally. Although reasonable, scientific validation has been difficult to obtain. However, a recent study from Oregon has compared data from two commercial vineyards, with vines of the same clone, rootstock, age, and vineyard management practices (Cortell et al., 2005). In sites expressing reduced vine vigor, proanthocyanidin, epigallocatechin, and pigmented polymer contents were significantly higher than from vines in blocks showing higher vigor. The differences in vine vigor were correlated to differences in soil depth and water holding capacity at the two sites. The results also indicate that for Pinot noir, the relative contribution of skin to seed proanthocyanidins increases with reduced vine vigor (Fig. 4.7). Although enhancing potential wine color, this is not necessarily associated with improved wine flavor (Chapman et al., 2004a). In addition, data from Chapman et al. (2004a, 2005) indicate that the manner of yield reduction (pruning vs. water deficit) may be more significant than yield reduction itself. This indicates that more needs to be done to understand how vineyard practice affects not only soluble solids and color, but also the concentration of varietal flavorants and wine flavor.

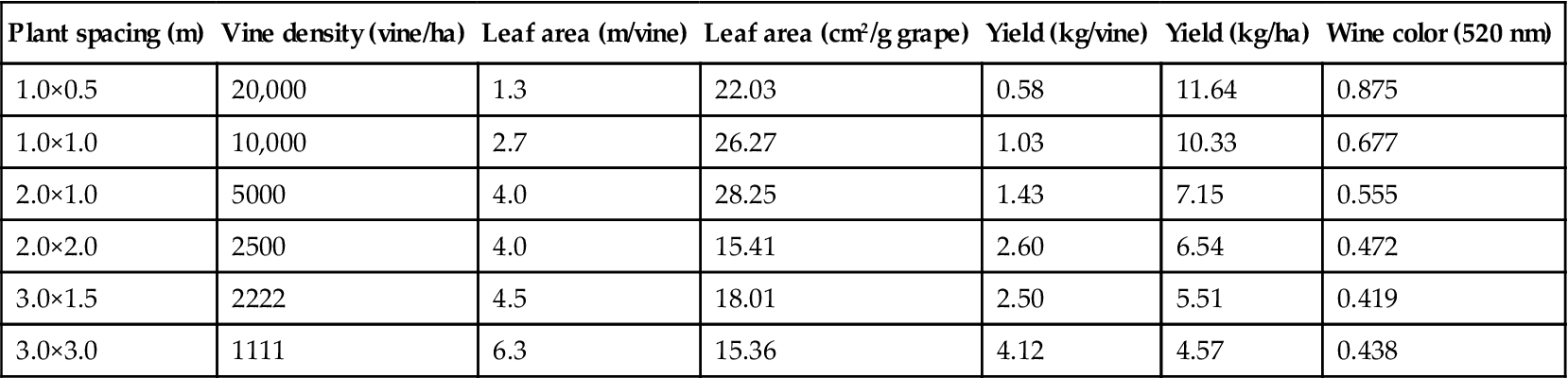

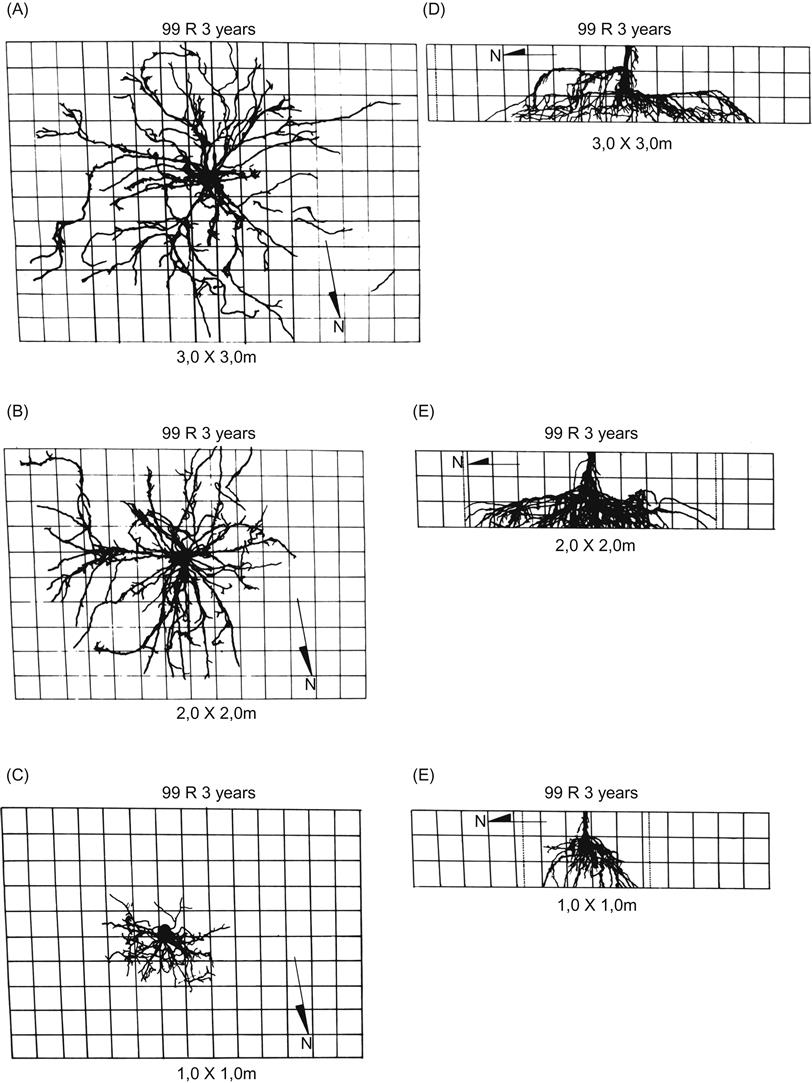

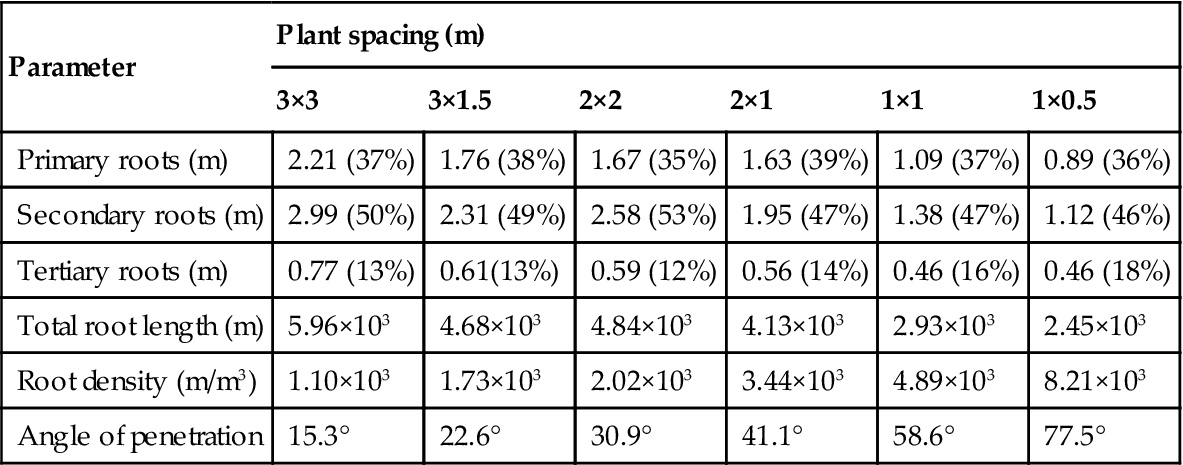

One of the techniques historically used to reduce yield has been dense planting. Intervine competition tends to promote the production of many fine roots. This, in turn, may enhance nutrient extraction from the soil. Some roots may also grow deep enough to reach subsurface supplies of water. The severe pruning associated with dense planting, however, can delay budbreak, as well as suppress fruiting potential (by removing fruit buds).

In the New World growers have had the luxury, not available in most European regions, to plant grapevines on rich, loamy soil, with ample supplies of moisture. Wide vine spacing, appropriate for standard farm equipment, further encouraged vigorous growth. Under such conditions, it is essential that the increased capacity be directed toward fruit production, not pruned away, causing dormant bud activation and excessive vegetative growth. The modern view is that when an appropriate functional LA/F ratio is developed, both fruit yield and wine quality can be simultaneously enhanced on fertile soils.

The development of training systems, based partially on achieving an optimal LA/F ratio, is one of the major success stories of modern viticulture. The first practical application of the concept of balancing photosynthetic capacity to yield was the Geneva Double Curtain. This has been followed by others, more appropriate for V. vinifera cultivars. Examples are Vertical Shoot Positioning (VSP), the Scott Henry, the Smart–Dyson, the Lyre, and Ruakura Twin Two Tier (see below).

These training systems, in addition to favoring an optimal LA/F ratio, provide better fruit exposure to light and air. These features promote good berry coloration, flavor development, fruit health, and inflorescence initiation. Optimal LA/F ratios tend to equate to 5–6 mature main leaves per medium-size grape cluster (Jackson, 1986). LA/F ratios lower than 6–10 cm2/g (0.6–1.0 m2/kg) are generally insufficient to fully ripen fruit, depending on the cultivar and growing conditions (Kliewer and Dokoozlian, 2005). Significantly higher values often indicate excessive shading, reduced anthocyanin content, delayed ripening, and inadequate °Brix values. However, as shown in Fig. 4.3, the relationship between the LA/F ratio and grape color can vary markedly between cultivars. Within limits, higher LA/F ratios favor earlier and more intense fruit coloration. Such features have usually been associated with enhanced wine flavor (Iland et al., 1993).

Physiological Effects of Pruning

Pruning is often used for several separate but related reasons. It permits the grape grower to establish a particular training system and manipulate vine yield. It is also a means by which bearing wood (spurs and canes) can be selected, thereby influencing the spacing, location, and development of the canopy. This, in turn, can affect grape yield, health, and maturation, as well as pruning and harvesting costs.

These influences should theoretically also affect wine quality, but until recently experimental evidence was lacking. A fascinating comparison of three pruning systems (as well as irrigation treatments) has been conducted by Holt et al. (2008a,b). Their data confirm anecdotal evidence of slight, but statistically significant, differences in fruit quality. Interestingly, small berry size and higher anthocyanin contents did not translate into darker colored wines or higher quality scores, possibly due to some aspect associated with higher tannin levels.

As noted, grapevines, like most temperate zone perennial fruit crops, show inflorescence initiation a season in advance of final development. However, unlike most orchard crops, inflorescence development occurs opposite leaves on vegetative shoots. In contrast, fruit development on pomaceous and stone fruit crops occurs on specialized, short, determinant spurs.

The property of inflorescence initiation, a year in advance of flower production, allows the grape grower to limit fruiting capacity by bud removal long before flowering. Winter pruning is the primary means by which grapevine yield is managed. However, as a perennial crop, the vine stores considerable energy reserves in its woody parts. Thus, pruning removes nutrients that can limit the initiation of rapid spring growth, notably in young vines. Vines with little mature wood are less able to fully ripen their crop in poor years than vines possessing large cordons or trunks. Some of these influences may also result from the balance between growth regulators, such as cytokinins and gibberellins (from the roots), and auxins (derived primarily from the shoot system). When performed judiciously, pruning can limit shoot vigor, permitting the vine to fully ripen its fruit load.

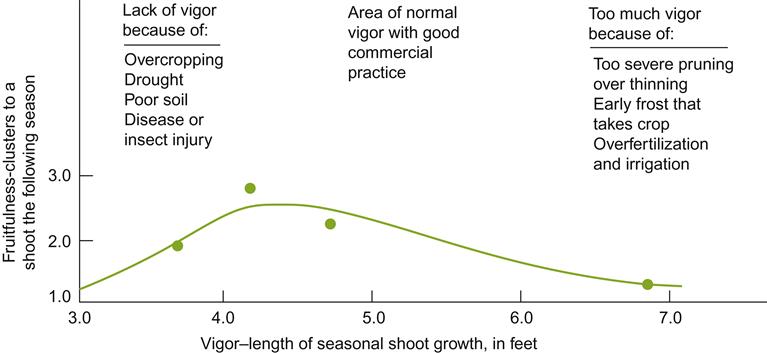

Both excessive pruning and excessive overcropping suppress vine capacity (Fig. 4.8). The reduced capacity associated with overcropping has long been known. It has been part of the rationale for the annual removal of 85–90% of any year’s shoot growth. However, as noted, severe pruning can lead to both reduced yield and grape quality. Severe pruning also delays budbreak and leaf production, in addition to potentially activating dormant buds. While beneficial in some climates, and with certain cultivars, delayed activation can result in leaf production continuing well into the fruiting period. This can limit photosynthate translocation to the ripening fruit.

Without pruning, shoot growth develops rapidly and fruit development starts early. However, extensive shoot growth can delay berry maturation. Yields can be 2.5 times that of pruned vines. This can also suppress fruit production in subsequent years, by reducing inflorescence initiation and diminishing nutrient reserves in old wood. However, if left unpruned, the vine eventually self-regulates itself, and good- to excellent-quality fruit may be obtained (see the ‘Minimal Pruning’ section on p. 176).

Because both inadequate and excessive pruning can compromise fruit quality, and diminish long-term fruitfulness, it is crucial that pruning be matched to vine capacity. The general relationship of shoot to berry growth and the concentration of carbohydrate in the shoot and fruit are illustrated in Fig. 4.9.

Winter pruning is the most practical, but least discriminatory type of pruning. Capacity can be only imprecisely predicted. In contrast, fruit thinning is the most precise type of pruning but the most labor-intensive, due to the difficulty of selectively removing clusters partially obscured by foliage. The typical method is judicious winter pruning, followed by remedial flower-cluster thinning in the spring, but only if deemed necessary. This solution limits potential fruit production, while delaying final adjustment until a more accurate estimate of grape yield is possible. It also favors early budbreak, maximizing carbohydrate production over the year, while minimizing competition between foliage and fruit during berry ripening. Where advisable, budbreak can be delayed by performing pruning in late winter/early spring.

Additional augmentation in vine capacity and fruit quality may be obtained with canopy management, by improving the microclimate in and around the grape cluster. Positioning the basal region of shoots in a favorable light environment improves inflorescence induction and helps maintain fruitfulness from year to year.

Clonal selection, the elimination of debilitating viruses, improved disease and pest control, irrigation, and fertilization have significantly amplified potential vine vigor. Thus, one of the challenges of modern viticulture is to channel this potential into enhanced fruit and wine quality, and away from undesirable, excessive, vegetative growth. Interest has been shown in minimal pruning, based on the potential of the vine to self-regulate fruit production. However, as the applicability of this technique to most cultivars and climates is unestablished, most of the following discussion deals with the fundamentals of traditional pruning.

In general, the principles of pruning enunciated by Winkler et al. (1974) are as valid today as ever:

1. Pruning reduces vine capacity by removing both buds and stored nutrients in canes. Thus, pruning should be kept to the minimum necessary, to permit the vine to fully ripen its fruit.

2. Excessive or inadequate pruning depresses vine capacity for several years. To avoid this, pruning should attempt to match bud removal to vine capacity.

3. Capacity partially depends on the ability of the vine to rapidly generate a leaf canopy. This usually requires light pruning, followed by cluster thinning to balance crop production to the existing canopy.

4. Increased crop load and shoot number depress shoot elongation and leaf production during fruit development and, up to a point, favor full ripening. Moderately vigorous shoot growth is most consistent with vine fruitfulness.

5. In establishing a training system, the retention of one main vigorous shoot enhances growth and suppresses early fruit production. Both speed development of the permanent vine structure. With established vines, balanced pruning augments yield potential.

6. Cane thickness is a good indicator of bearing capacity. Thus, to balance growth throughout the vine, the level of bud retention should reflect the diameter of the cane. Alternatively, if bud numbers should remain constant, the canes or spurs retained should be relatively uniform in thickness.

7. Optimal capacity refers to the maximal fruit load that the vine can ripen fully within the normal growing season. Reduced fruit load has no effect on the rate of ripening. In contrast, overcropping delays maturation, increases fruit shatter, and decreases berry quality. Capacity is a function of the current environmental conditions, those of the past few years, and the genetic potential of the cultivar.

Pruning Options

When considering specific pruning options, features such as the prevailing climate, genetic attributes of both rootstock and scion (shoot section), soil fertility, and training system need assessment. Several of these factors are considered below.

The prevailing climate imposes constraints on where and how grapevines can be grown. In cool continental climates, severe winter temperatures may kill most buds. Equally, late-spring frosts can damage or destroy newly emerged shoots and inflorescences. Where such losses occur frequently, more buds need to be retained than theoretically ideal, to compensate for potential bud kill. Subsequent disbudding, or flower-cluster thinning, can adjust the potential yield downward if required. Alternatively, varieties may be pruned in late winter or very early spring to permit the pruning level to reflect actual bud viability and/or delay bud burst. Another possibility, with spur-pruned wines, is to leave a few canes as insurance (Kirk, 1999). Because buds at the base of canes usually break late, they may survive and replace emerging shoots killed by late frosts. There may also be some apical dominance delay in the buds on spurs, imposed by those on the canes. If no frost damage occurs, the canes can be easily removed before significantly affecting growth from the spurs.

As deep fertile soil enhances vigor, moderate pruning is often employed to permit sufficient early shoot growth to restrict late vegetative growth during fruit ripening. Vines on poorer soils usually benefit from more extensive pruning. This channels nutrient reserves into the remaining buds, assuring sufficient capacity for canopy development, fruit ripening, and inflorescence initiation. Nutrients discarded during pruning are compensated for by the higher proportion of old wood in established vines.

Varietal fruiting characteristics, such as bunches per shoot, flowers per cluster, berry weight, and bud position along the cane, can influence the extent and type of appropriate pruning. Some cultivars, such as Sultana and Nebbiolo, produce sterile buds near the base of the cane. As spur pruning would leave few if any fruit buds, these varieties need to be cane-pruned. Varieties showing strong apical dominance may also fail to bud out from the base to the middle of the cane (Fig. 4.10). Arching and inclining the cane downward can reduce apical dominance in varieties where this is a problem, and balance budbreak along the cane. Alternatively, spur pruning limits the expression of apical dominance.

Varieties tending to produce small clusters are left with more buds than those bearing large clusters, to correlate yield with varietal fruiting characteristics. Many of the more renowned cultivars produce small clusters, for example Riesling, Pinot noir, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Sauvignon blanc. Large-clustered varieties include Chenin blanc, Grenache, and Carignan. The susceptibility of varieties such as Gewürztraminer to inflorescence necrosis (coulure) also demands adjustment of how many buds should be retained. In addition, the ideal number of buds retained depends on the tendency of the variety to produce fertile buds along the cane. Examples of cultivars having a high percentage of fertile buds are Muscat of Alexandria and Rubired.

Harvesting method (manual vs. mechanical) can also influence the choice of pruning and training. Spur pruning along a cordon is generally more adapted to mechanical harvesting than cane pruning. It is also easier for inexperienced pruners to learn than cane pruning.

Not least among grower concerns is the expense of pruning. Although the most economical is winter pruning, it is the most difficult to employ skillfully because it is impossible to predict bud viability. This can be periodically assessed with selective bud dissection. However, to reflect actual potential the procedure must be conducted near the end of winter, which would delay pruning more than is usually practical (relative to other essential vineyard activities) or preferred (vineyardist philosophy). Cluster and fruit thinning permit precise yield regulation, but are costly. Pragmatism generally favors winter pruning as the method of choice.

Pruning Level and Timing

Widely spaced vines of average vigor and pruning degree may produce up to 25 canes, possessing about 30 buds each by the end of the season. Thus, before pruning, the vine may possess upward of 750 buds. Even without pruning, only a small number of the buds (about 100–150) would burst the following spring. Despite this, they would generate a fruit load considerably in excess of the wine’s ability to mature fully. Thus, pruning is traditionally required. However, as noted, excessive removal can undesirably impact fruit maturity and subsequent fruitfulness. Thus, determining the appropriate number of buds to retain is one of the critical yearly vineyard tasks. The job is made all the more complex because actual fruitfulness is known only in the spring, after winter pruning is complete.

This has led to several attempts to improve yield-potential assessment. One method involves direct observation of sectioned buds just prior to pruning. Although reliable, it is another expense, but can be worth it for the peace of mind it gives in cold climatic regions. No electronic device currently assesses bud viability. Another option for assessing bud retention involves a ‘hedging one’s bets’ approach – balanced pruning. It estimates the vine’s capacity, based on the weight of cane cuttings removed during pruning. From this, an optimal number of buds for retention is established. Depending on previous experience, additional buds may be retained to account for possible bud mortality during the winter. Based on bud burst, the excess is removed. Only buds separated by obvious internodes are counted, as base (noncount) buds usually remain dormant.

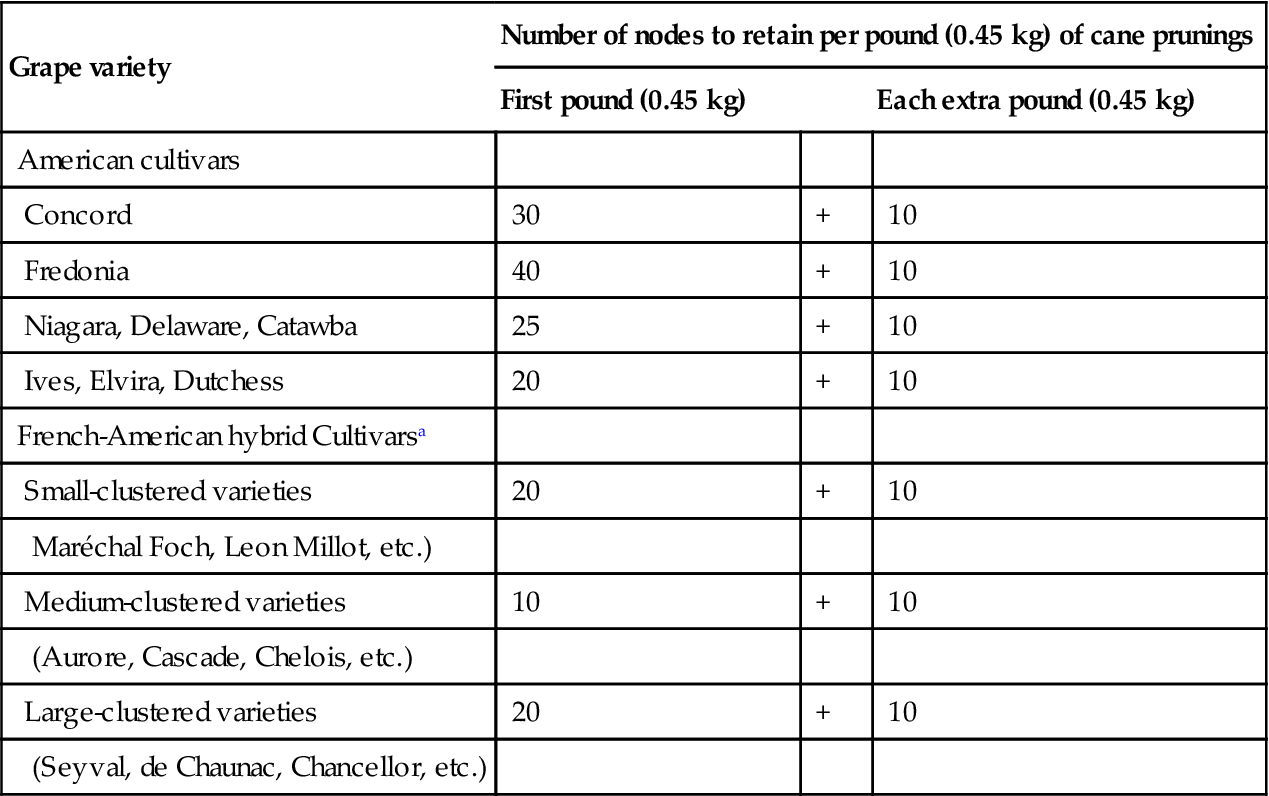

In balanced pruning, the number of buds retained is indicated in increments (weight-of-prunings) above a minimum, established empirically for each cultivar (see Table 4.1). Pruning recommendations are usually given in parentheses, for example (30+10). The first value indicates the number of buds (count nodes) retained for the first pound of prunings, and the second value suggests the number of buds to retain for each additional pound of prunings. ‘Pound of prunings’ (assessed by a direct weighing of bundling cuttings from individual vines) is taken as an indicator of last year’s vine capacity and a predictor of current potential. Values for vinifera cultivars under Australian conditions are in the range of 30–40 buds/kg of prunings (Smart and Robinson, 1991). Vines producing less than a minimum weight-of-prunings are pruned to less than the suggested basic number of buds.

Table 4.1

Suggested Pruning Severity for Balanced Pruning of Mature Vines of Several American (Vitis labrusca) and French-American varieties in New York State

| Grape variety | Number of nodes to retain per pound (0.45 kg) of cane prunings | ||

| First pound (0.45 kg) | Each extra pound (0.45 kg) | ||

| American cultivars | |||

| Concord | 30 | + | 10 |

| Fredonia | 40 | + | 10 |

| Niagara, Delaware, Catawba | 25 | + | 10 |

| Ives, Elvira, Dutchess | 20 | + | 10 |

| French-American hybrid Cultivarsa | |||

| Small-clustered varieties | 20 | + | 10 |

| Maréchal Foch, Leon Millot, etc.) | |||

| Medium-clustered varieties | 10 | + | 10 |

| (Aurore, Cascade, Chelois, etc.) | |||

| Large-clustered varieties | 20 | + | 10 |

| (Seyval, de Chaunac, Chancellor, etc.) | |||

aAll require suckering of the trunk, head, and cordon during the spring and early summer.

Source: After Jordan et al., 1981, reproduced by permission.

Alternative measures of pruning level are presented in terms of buds retained per vine, or per meter row. For example, under Australian conditions and at 3 m row spacing, severe, moderate, and light pruning are noted as<20, 20–70, and>75 nodes per meter row, respectively (Tassie and Freeman, 1992).

Balanced pruning has been used primarily with labrusca varieties in eastern North America. The application of the technique to other varieties has been less successful. When used, pruning recommendations must account for cultivar fertility and prevailing climatic conditions. For example, varieties with low fertility need more buds to improve yield potential, whereas bud retention must be adjusted downward in regions with short growing seasons to permit full crop ripening. In addition, the tendency of buds to produce more than the standard two clusters per bud (up to four), and the production of flower clusters from shoots derived from noncount (base) buds, has limited the usefulness of balanced pruning with most French-American hybrids (Morris et al., 1984). Preliminary evidence indicates that flower cluster and shoot thinning may be more effective means of limiting overcropping for hybrids (Morris et al., 2004), though results can vary from cultivar to cultivar.

Balanced pruning has found particular value in research, where objective values are required (values of 0.3–0.6 kg/m prunings are frequently considered optimal). Taking measurements has found less use under commercial practice. Good pruners intuitively learn to adjust bud number to vine capacity by visual assessment, without the need for quantification.

Alternative measures for assessing pruning level employ data collected over several years. This involves programing in bud retention data to obtain a formula appropriate for a specific target. The desired yield is divided by vine density to obtain yield per vine. The yield per vine is divided by anticipated (desired) bunch weight to determine the number of bunches per vine. This is, in turn, divided by the number of bunches typical per shoot. This supplies the number of buds to retain per vine. Final adjustments are based on the capacity (relative size) of individual vines, cultivar characteristics, information on bud viability prior to harvesting, and data on actual/likely frost and freeze damage subsequent to pruning.

With the development of mechanical pre-pruners, it is far more economical to have the major job done by machine, with manual pruning limited to fine-tuning bud number and distribution to match individual vine capacity (see Tassie and Freeman, 1992). Pre-pruners were initially designed for spur-pruned vines, but advances have adapted machines for cane-pruned vines. This requires manually tying down the desired canes. The machine sequentially cuts off the excess, pulls out the cut canes, and mulches them as it moves down each row. Pruners can follow, removing cane remnants and supplying any fine-tuning required. Recent development with robotics, combined with artificial intelligence, and real-time, stereoscopic, camera feedback may eliminate even the need for manual clean-up (Smith, 2009). The machine could be programmed with GPS data to work by itself, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, as required.

Winter pruning may be conducted from leaf fall until after budbreak. The earliest commencement is set by when the phloem has sealed itself with callose for the winter. This avoids nutrient loss and the activation of partially dormant buds. Winter pruning has many advantages, notably a dearth of other vineyard activities. Also, bud counting and cane selection are easier with bare vines. Equally, prunings can be more easily disposed of, either by chopping for soil incorporation or, as common in the past, burning. Wet periods should be avoided, both for human comfort and as a precaution against infection by xylem-infecting pathogens, notably Eutypa lata.

For tender varieties, pruning is normally performed late, when the danger of killing frost has passed. The proportion of dead buds can then be assessed directly by cutting a sample. Dead buds show blackened primary and possibly secondary buds (Plate 5.1). An alternative is double pruning – most of the pruning and clean-up occurring during the winter, with a final removal delayed until budbreak. The slight delay in bud burst induced by this technique has been used for frost protection. It can retard budbreak by one to several weeks in precocious varieties. Late pruning has also been used to delay budbreak in regions experiencing serious early season storms, such as the Margaret River region of Western Australia. Friend and Trought (2007) also found that late pruning improved fruit set, presumably due to flowering occurring under warmer conditions favorable to fertilization. Because the delay induced by late pruning often persists through berry maturity, harvesting may be equally retarded. Thus, the advantages of delayed budbreak must be weighed against the potential disadvantages of deferred ripening. For some cool-climate cultivars, delayed maturation can be desirable when grown in warm regions as it can produce fruit higher in acidity, enriched in color, and augmented in flavor (Dry, 1987). Regrettably, it can also reduce yield, although this could also be an advantage depending on the conditions. Late pruning can also be used as a means to reduce the incidence of Eutypa dieback. In contrast, early budbreak may be desired in hot climates. This adjusts flowering and fruit set to a period when temperature conditions are more likely conducive to their occurrence.

Pruning and thinning in late spring and early summer involve adjustments, and are designed as much to improve vine microclimate or minimize wind damage as to limit fruit production. These activities may involve disbudding, pinching, suckering, topping, and thinning of flower or fruit clusters. However, due to their cost and increasing complexity, it is preferable to limit their use as much as possible by appropriate winter pruning.

Disbudding is commonly used in training young vines to a desired mature form. It is also employed to remove unwanted base or latent buds that may have become active. Early removal economizes nutrient reserves and favors strong shoot growth.

Once growth has commenced, summer pruning may involve the partial or complete removal of shoots. Repeat activation of suckers and water sprouts (Fig. 4.11) throughout the growing season is often a sign of overpruning and insufficient energy being directed to fruit production. Removal avoids excessive foliage density that enhances disease severity, impedes disease and weed control, complicates mechanical harvesting, and reduces inflorescence induction, fruit yield, and grape quality. Alternatively, application of naphthalene acetic acid (NAA), mixed with latex paint or asphalt, can control suckers for 2–3 years. The incorporation of hexyl 2-naphthyloxyacetate in the mix increases NAA solubility, reduces the concentration required, and extends the effective application period (Dolci et al., 2004). Trunk application is best conducted after budbreak on the bearing wood.

Although the growth of suckers is undesirable, some water sprouts can occasionally be of use. If favorably positioned, they can act as replacement spurs in repositioning the vine growing point(s) (Fig. 4.11). As the vine grows, the location of renewal wood tends to move outward. Replacement spurs reestablish, and thus can maintain the vine’s shape and training system. The necessity of such procedures has been long known, having been clearly enunciated by Roman authors such as Columella (Re De Rustica, 4.21). Depending on their position, water sprouts may also supply nutrients for fruit development.

Shoot thinning at flowering can correct imperfections in the positioning of shoots, or remove weak or nonbearing shoots. If the vine is in balance, and winter’s cold or late frosts have not caused extensive bud or shoot kill, the need for shoot thinning should be negligible.

Partial shoot removal, called trimming, can vary widely in degree and timing. Pinching refers to the removal of the uppermost few centimeters of shoot growth. More extensive trimming is called tipping, topping, or hedging, depending on the timing and relative amount removed. In general, trimming is kept to the bare minimum. If extensive, it is less physiologically disruptive if performed periodically and moderately, rather than all at once.

Pinching, if used, is usually conducted in early season. When performed during flowering, fruit set may be enhanced (Collins and Dry, 2006). The procedure may reduce inflorescence necrosis in varieties predisposed to this disorder, presumably by reducing carbohydrate competition between the developing leaves and embryonic fruit at this critical period. Pinching can also be used to maintain shoots in an upright position. The activation of limited lateral shoot growth may provide desirable fruit shading in hot sunny climates.

Tipping (topping) occurs later and may be repeated periodically throughout the growing season. It usually removes only the shoot tip and associated young leaves, leaving at least 15 or more mature leaves per shoot. Depending on the timing, it can reduce competition between developing flowers or fruit and young leaves for photosynthate, redirecting carbohydrate movement to the fruit (Quinlan and Weaver, 1970). Tipping can also improve canopy microclimate by removing undesirable draping leaf cover. In windy environments, tipping produces shorter, more sturdy, upright shoots less susceptible to wind damage. However, tipping can reduce cane and pruning weights and the number of shoots and grape clusters in the succeeding year (Vasconcelos and Castagnoli, 2000).

Hedging (trimming of the vine to produce vertical canopies resembling a hedge) removes entangling vegetation that can impede machinery movement through the vineyard. This is often necessary where vines are densely planted (rows≤2 m wide). Like tipping, it reduces carbohydrate competition between new expanding leaves and the fruit, but also lowers vine capacity. Hedging increases the number of shoots but reduces their relative length, tending to increase light and atmospheric exposure of the leaves and fruit.

Trimming shoots to less than 15 leaves is generally undesirable. If this occurs during or before fruit set, it can stimulate undesirable lateral bud activation. The extent to which this occurs is partially dependent on the variety and the form of training (upright vs. downward shoot growth) (Poni and Intrieri, 1996). In contrast, late trimming (after véraison) seldom activates lateral growth. However, a deficiency in photosynthetic potential may persist, delaying both fruit and cane maturation as well as decreasing cold-hardiness. Physiological compensation by the remaining leaves, through delayed leaf senescence and higher photosynthetic rates, is usually inadequate. The degree to which these problems manifest themselves depends on the severity of trimming.

Trimming can variously affect fruit composition, depending on its timing, severity, and vine capacity. Many of the effects resemble those of basal leaf removal discussed below. The potassium content of the fruit increases more slowly and peaks at a lower value (Solari et al., 1988). The rise in berry pH and the decline in malic acid content associated with ripening may be less marked. Total soluble solids may be little influenced, or reduced, in trimmed vines. Anthocyanin synthesis may be adversely affected in varieties such as de Chaunac (Reynolds and Wardle, 1988). This tendency presumably is not found in Bordeaux, where hedging is common. Improvements in amino acid and ammonia nitrogen levels associated with light trimming shortly after fruit set (Solari et al., 1988) may be one of the more desirable features induced by trimming.

Considerable interest has been shown in single, or repeat, partial leaf removal around and slightly above fruit clusters (basal leaf removal). Leaf removal selectively improves air and light exposure around the clusters. This can modify fruit attributes as well as yield. It also eases the effective application of protective agents to the fruit. The reduced incidence of bunch rot was one of the first benefits detected with basal leaf removal. This has been attributed to the increased evaporative potential, wind speed, higher temperature, and improved light exposure in and around the fruit (Thomas et al., 1988).

The desirability of basal leaf removal depends largely on its timing and cost/benefit ratio. If the vine canopy is open and the fruit adequately exposed to light and air, leaf removal is probably unnecessary and undesirable, as it removes photosynthetic potential. In hot sunny climates late basal leaf removal could expose the fruit to sunburn, delay maturity, and reduce (modify) wine quality (Greer et al., 2006).

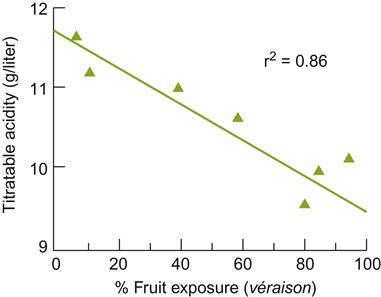

An effect generally associated with basal leaf removal is a decline in titratable fruit acidity (Fig. 4.12). This is associated with a reduction in potassium uptake and enhanced malic acid degradation. Tartaric and citric acid levels are seldom affected. The amino acid content tends to be modified, being particularly noticeable in a reduced proline content. Anthocyanin levels generally are significantly enhanced, as is the flavonol content, whereas total phenol content may rise or remain unchanged. Berry sugar content is seldom affected significantly.

Relative to flavor content, grassy, herbaceous, or vegetable odors tend to decline, as do the levels of methoxypyrazines. Fruity aromas may rise or remain unaffected. Depending on the cultivar, terpene (Table 4.2), norisoprenoid (Marais et al., 1992a), and fruity-smelling thiol precursor contents (Murat and Dumeau, 2005) may increase. In Riesling grapes, basal leaf removal may increase the glycosyl-glucose concentration (Zoecklein et al., 1998), an indicator of flavor potential. Although usually beneficial, excessive production of some norisoprenoids, for example 1,1,6- trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene (TDN), as well as their precursors, can generate undesirable kerosene-like fragrances in Riesling wines (Marais et al., 1992b).

Table 4.2

Aroma Profile Analysis and Protein Content of Sauvignon blanc Fruit with and without Basal Leaf Removal

| Control | Basal leaf removal | |

| Free aroma constituents (µg/liter) | ||

| Geraniol | 1.6 | 9.5 |

| trans-2-Octen-1-al | 0.3 | 3.1 |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 2.4 | 6.6 |

| trans-2-Octen-1-ol | 6.5 | 11.7 |

| trans-2-Penten-1-al | 4.6 | 12.7 |

| α-Terpineol | 1.9 | 4.1 |

| Potential volatiles (µg/liter) | ||

| Linalool | 23 | 49 |

| trans-2-Hexen-1-ol | 29 | 61 |

| cis-3-Hexen-1-ol | 5.1 | 6.3 |

| trans-2-Octen-1-ol | 321 | 830 |

| 2-Phenylethanol | 17.9 | 50 |

| β-Ionone | 26 | 66 |

| Protein (mg/liter)a | ||

| Molecular weight>66,000 | 32 | 33 |

| Molecular weight<20,000 | 62 | 81 |

aBased on bovine serum albumin as standard.

Source: From Smith et al., 1988, reproduced by permission.

Most studies have not noted a change in bud cold-hardiness or fruitfulness (see Howell et al., 1994). This probably results because leaf removal typically occurs after inflorescence initiation has occurred and involves the more mature buds near the base of the shoot.

The effects of basal leaf removal depend considerably on timing. Its benefits show most clearly when occurring after flowering and before véraison. Earlier removal (during bloom) tends to increase inflorescence necrosis, reduce inflorescence initiation (Candolfi-Vasconcelos and Koblet, 1990), and promote flower abscission (Lohitnavy et al., 2010). Basal leaves are typically the primary exporters of carbohydrate to flowers and during fruit set (import of carbohydrate reserves from perennial parts of the vine has usually ceased by this time). Later removal, when more leaves have matured, does not significantly affect fruit set nor the initial stages of fruit development (Vasconcelos and Castagnoli, 2000). However, removal after véraison may be detrimental by reducing sugar accumulation (Iacono et al., 1995), or show few benefits (Hunter and Le Roux, 1992).

The impact of basal leaf removal is clearly influenced by the number of leaves removed. Removal usually involves only the leaves positioned immediately above, below, and opposite the fruit cluster. The vine may compensate for the photosynthate lost by increasing the number of leaves produced on lateral shoots, delaying leaf senescence, or enhancing the photosynthetic efficiency of the remaining leaves (Candolfi-Vasconcelos and Koblet, 1991).

By adjusting carbohydrate supply during flowering by basal leaf removal (or tipping and lateral shoot removal), the grower can increase or decrease fruit set, as well as influence fruit ripening. These canopy management activities affect the average age and photosynthetic productivity of the canopy. Improved fruit set will be desirable in cultivars showing poor fruit set (e.g., Gewürztraminer), whereas reduced fruit set can be beneficial in cultivars susceptible to bunch rot.

In practice, basal leaf removal has been limited, presumably because of its expense. This may change with the introduction of efficient mechanical leaf-removers. One model involves suction that draws leaves toward a set of cutting blades.

Pre-bloom defoliation (Poni et al., 2006, 2009) is another leaf removal procedure. It is primarily aimed at yield reduction and fruit quality improvement. It is an alternative to the complexities of manual cluster thinning. In addition, it can reduce the concentration of 3-isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine in cultivars such as Cabernet franc and Merlot (Scheiner et al., 2010).

Another method of adjusting fruit yield involves flower- or fruit-cluster (bunch) thinning. Its principal purpose is to prevent overcropping. In this regard, flower-cluster thinning has a similar effect to delayed winter pruning, in permitting a more precise adjustment of fruit load to vine capacity. Fruit-cluster thinning can be even more precise, but is more difficult, owing to the more advanced state of canopy development. Fruit-cluster thinning is especially useful with French-American hybrids, in which overcropping is a potential problem due to base-bud activation. As fruit set tends to suppress the growth of lateral shoots, delaying crop reduction (as results with fruit-cluster thinning) can achieve the desired level of fruit production, without promoting undesirable bud activation. Bunch thinning may also be considered if leaf damage from pathogen or pest attack is severe. By reducing the carbohydrate sink, the remaining clusters will have a better chance of fully ripening, and the vine can regain strength for subsequent growth.

Occasionally, flower-cluster thinning favors the development of more, but smaller, berries in the remaining clusters. This can be valuable in reducing bunch rot in varieties that form compact clusters, such as Seyval blanc and Vignoles (Reynolds et al., 1986). However, within the usual range of vine capacity, fruit-cluster thinning may show marginal or insignificant improvement in fruit chemistry (Keller et al., 2005), and no detectable effect on wine quality (McDonald, 2005). Thus, the yield losses incurred by cluster thinning, and its expense, must be weighed against the potential benefits it may provide. It may be of value only with cultivars or clones that overproduce regularly (Bavaresco et al., 1991). This, of course, depends on accurate estimates of yield potential. Various methods have been devised for predicting this statistic (Tarter and Keuter, 2008; Dunn, 2010). Once established, Preszler et al. (2010) have proposed a model for assessing the cost/benefit ratio of the procedure. Yield control is, however, more frequently and economically achieved by selective pruning, shoot thinning, and the various means of vigor control.

Bearing Wood Selection

Although balancing yield to capacity is important, it is equally important to choose the best canes for fruit bearing. The proper choice of bearing wood is especially significant in cool climates. Fully matured healthy canes produce buds that are the least susceptible to winter injury. Canes that develop in well-lit regions of the vine also tend to be the most fruitful. Browning of the bark is the most visible sign of cane maturity. Typical internode distances are also a varietally useful indicator of fruitfulness. The presence of short, mature lateral shoots on a cane often signifies good bearing wood. Canes of moderate thickness (about 1 cm) are generally preferred as their buds tend to be the most fruitful. Canes of similar diameter tend to be of equal vigor and, thus, maintain balanced growth throughout the vine. Other indicators of healthy, fruitful canes are the presence of round (vs. flattened) buds, brown coloration to the tip, and hardness to the touch.

Where canes of different diameters are retained, the number of buds (nodes) per cane should reflect the capacity of the individual cane. Thus, weaker canes are pruned shorter than thicker canes.

Equally important to balanced growth is an appropriate spacing of the bearing wood. Retained canes should permit the optimal positioning of the coming season’s bearing shoots for photosynthesis and fruit production. Thus, canes are normally selected that originate from similar positions on the vine. If the vine is cordon-trained, canes originating on the upper side of the cordon are preferred.

Pruning Procedures

Manual pruning requires extensive knowledge of how varietal traits influence vine capacity. An assessment of the health of each vine and the appropriate location, size, and maturity of individual canes is needed. This demands considerable skill from the labor force, a property which is becoming increasingly difficult to find and retain. With the savings obtained using machine harvesting, pruning has become one of the major costs of vineyard maintenance. These factors have led to increased interest in mechanical pruning, which can frequently result in a cost reduction of 40–45%, compared with pneumatic manual pruning (Bath, 1993). With spur pruning, variation in spur length can be equivalent to that of manual pruning (Intrieri and Poni, 1995). Variation can come from irregularities in the terrain, cut angle, and anomalies in cordon shape. Some remedial manual pruning may be required to retain only spurs about 12 cm apart, in order to minimize shoot crowding and fruit congestion.

Mechanical pruning has been most successful with cordon-trained, spur-pruned vines. The cutting planes can be adjusted easily to remove all growth except that in a designated zone around the cordon (Plate 4.1). The cutting planes can also be adjusted for skirting or hedging to ease mechanical harvesting. Pivot cutting arms, associated with a feeder device, minimize damage to the trunk or trellis posts. If a clean-up, manual pruning is required, the mechanical component is called pre-pruning. However, experience may demonstrate that this is unnecessary, due to reduced budbreak compensating for extra bud retention. Mechanical pruning can significantly reduce pruning time by up to 70–80%. The applicability of mechanical pruning is often cultivar-dependent. For example Malbec, Barbera, Riesling, and Sémillon may respond well, whereas others such as Shiraz and Sangiovese may not.

With some cultivars, mechanical pruning has the additional advantage of generating more uniform vines. These tend to produce smaller but more numerous grape clusters. The yield may initially be higher than with manual pruning, due to the retention of a higher bud number. Nonetheless, subsequent self-adjustment results in average yield being unaffected.

A distinctly novel approach to pruning has been suggested by work initially conducted in Australia (Clingeleffer, 1984). The experiments have shown that some cultivars regulate their own growth, and can yield good-quality fruit without regular pruning. The results have spawned the minimal pruning system, now fairly common in many parts of Australia. It usually involves only light mechanical pruning – along the sides or at the base of the vine during the winter, and possibly some summer trimming (skirting) to prevent shoot trailing on the ground. Initially, vines may overcrop, but this diminishes as vines reduce the number of buds that mature and become active in subsequent years. Spontaneous abscission of most immature shoots in the autumn essentially eliminates the need for a major winter pruning.

Minimal pruning was initially developed for Sultana, grown in hot, irrigated vineyards. It has subsequently been applied with considerable success to several premium grape varieties, such as Riesling, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Shiraz. Some of Australia’s most prestigious vineyards are minimally pruned. It has proven successful in both hot and cooler viticultural regions in Australia.

In viticulture, pruning normally refers to the removal of aerial parts of the vine. In other perennial crops, such as fruit trees, pruning frequently entails root trimming. Although much less common in viticulture, root pruning has been investigated as a technique to restrict excessive shoot vigor (Dry et al., 1998). Clear cultivation in the vineyard, by repeatedly severing surface feeder roots, may have the same effect. A similar treatment was strongly recommended by Columella in Roman times.

Cutting large-diameter roots of grapevines to a depth of 60 cm can promote shoot growth under conditions in which growth is retarded by soil compaction. Under such conditions, root pruning is recommended in adjacent rows in alternate years (van Zyl and van Huyssteen, 1987). Susceptibility of the roots to pathogenic attack does not seem enhanced by the procedure. New lateral-root development may occur up to 5 cm back from the pruning wound. Thus, there may be long-term benefits, despite potentially undesirable short-term reduction in shoot growth.

Training Options and Systems

Training involves the development and maintenance of the vine’s woody structures in a particular form. It is one of the principal means by which optimal fruit quality and yield is achieved, consistent with prolonged vine health and economic vineyard operation. Because grapevines have remarkable regenerative powers, established vines can buffer the effects of a change in training system for several years. Thus, studies on training systems must be conducted over many years in order to assess their actual long-term effects. In addition, factors such as varietal fruiting habits, prevailing climate, disease prevalence, desired fruit quality, type of pruning and harvesting, and grape pricing can all influence choice. Most of these factors are similar to those that affect pruning choices just discussed. Regrettably, tradition and appellation control intransigence have retarded the adoption of newer, more efficient systems in some European regions.

Because many training systems are only of local interest, and new and improved ways of training are constantly being developed, the discussion below focuses primarily on the components that distinguish training systems. Illustrations outlining the establishment of several common training systems are given in Pongrácz (1978). Details on regional training systems are generally available from provincial or state viticulture research stations.

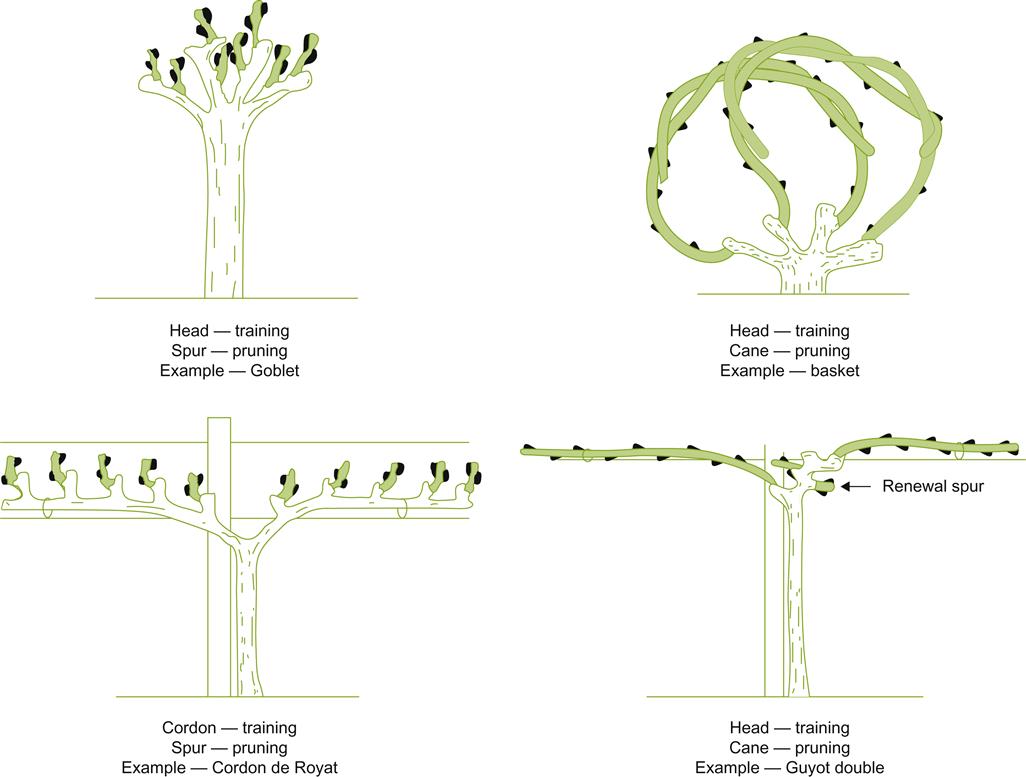

There is no universally accepted system of classifying training systems. Nonetheless, most systems can be organized by the origin and length of their bearing wood – head vs. cordon, and cane vs. spur, respectively. These groupings can be further subdivided by the height and position of the bearing wood, the placement of the bearing shoots, and the number of trunks retained. Ancient systems where vines are permitted to grow up on trees do not conveniently fit into this classification, and resemble natural grapevine growth or crude arbors.

Bearing Wood Origin

One of the most distinguishing features of a training system relates to the origin of its bearing wood. On this basis, most training systems can be classed as either head trained or cordon trained (Fig. 4.13). Head training positions the canes or spurs that generate the fruit-bearing shoots radially from a swollen apex, or as several radially positioned short arms at the trunk apex (Plate 4.2). In contrast, cordon training positions the bearing wood equidistantly along angled portion(s) of the trunk (cordons). In most cordon-trained systems, the cordon is developed along a horizontal plane, usually parallel to the row. Occasionally, however, cordons may be inclined at an intermediate angle, or initially directed outward at right-angles to the row.

Historically, head training was common in much of southern Europe. Its simplicity made it easy and inexpensive to develop. Maintenance was also fairly simple. The bearing shoots of one season often provided the bearing wood for the next year’s crop. As the vine matured and the trunk thickened, the vine became self-supporting, avoiding the expense and complexity of a trellis and shoot positioning. The lack of support wires also permitted cross-cultivation, desirable when weed control involved manual or animal labor. Head training was also particularly suitable with soils of low fertility and where water availability was limited.

The major drawback of head training is shoot crowding – especially where vines have medium to high vigor. Shoot crowding leads not only to undesirable fruit, leaf, and cane shading, but also to higher canopy humidity. The latter favors disease development, whereas other aspects often lead to poorer fruit maturation, as well as reduced photosynthesis, bud fruitfulness, and cane maturation. In hot dry sunny climates these features could be partially beneficial. They avoid some of the potential problems with severe pruning, but in so doing created others, notably curtailed yield and delayed shoot development. Severe pruning can also accentuate vegetative growth, to the detriment of fruit development and maturation. Because limited bud retention increases the potential damage caused by early frosts, head training has rarely been used in cool climate regions.

The disadvantages of head training, except for vines of low vigor, are augmented if combined with spur pruning. Spur pruning increases the tendency to produce compact canopies. Although it provides useful fruit shading in hot dry climates, it favors disease development and poor maturation in more temperate moist climates. These effects may be partially offset by using fewer, but longer spurs. However, this makes maintaining vine shape more difficult. Moreover, head-trained, spur-pruned systems are unsuited to mechanical harvesting. They most commonly have been used in dry Mediterranean-type climates, even though they may lead to higher evapotranspiration rates than other training systems (van Zyl and van Huyssteen, 1980). This may result from increased evaporation from soil not protected by foliage from wind and sun exposure. The Goblet training system, traditionally used in southern Europe (see Fig. 4.13) is a classic example of a head-trained, spur-pruned system. It is suitable only for cultivars with medium-size fruit clusters that produce fruitful buds to the base of the cane.

In contrast, head training associated with cane pruning has been more common in cooler moister climates. In addition to providing a more favorable canopy microclimate, cane pruning retained and dispersed more fruit-bearing shoots away from the head. This enhanced yield with cultivars bearing small fruit clusters, such as Riesling, Chardonnay, and Pinot noir. Larger-clustered varieties, such as Chenin blanc, Carignan, and Grenache, or those with very fruitful buds, such as Muscat of Alexandra and Rubired, tend to overproduce with cane pruning. The Mosel Arch (see Fig. 4.16A) is a novel and effective approach, by which cane bending supplies both shoot support and diminished apical dominance along the cane. Shoot dispersion, possible with cane pruning, normally requires the use of a trellis and wires along each row to support the crop. It provides both better light exposure and enhanced yield. With this system, canes may eventually arch or roll downward. In cooler climates this may be desirable to provide direct fruit exposure to the sun. In hot dry climates this is usually undesirable, favoring fruit burn. Under such conditions, additional foliage-support (catch) wires may be used to raise the foliage and provide necessary shading, or simply to support the shoots to prevent excessive arching. Thus, although improved exposure of the fruit to the sun is usually considered beneficial, especially for red cultivars, it can be a mixed blessing for white grapes. Besides sunburn, light exposure can affect flavor development, both beneficial or detrimental, depending on what attributes are desired in the wine. For example, reduced sun exposure limits the accumulation of flavonols, such as quercetin and kaempferol.

In making any decision, there is nothing better than the local experience of others, combined with personal, goal-oriented experimentation and record keeping. ‘Paint-by-numbers’ vitiviniculture has never (or at least rarely) made great wine.

In cane pruning, it is necessary to select renewal spurs (Fig. 4.11). They are required because the canes of one season cannot be used as bearing wood for the next season. Their use would quickly result in relocating the bearing wood away from the head. The same tendency occurs with spur pruning, but at a slower pace. The conscious selection of renewal shoots may be reduced if water sprouts develop from the head. Common examples of head-trained, cane-pruned systems are the Guyot in France and the Kniffin in eastern North America.

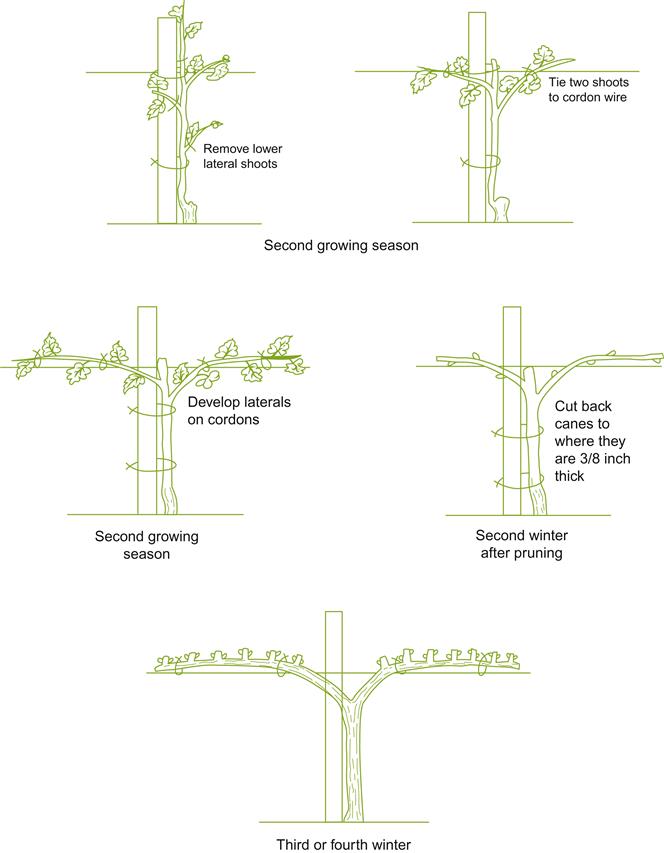

In contrast to the central location of the bearing wood in head training, cordon training positions the bearing wood along the upper portion(s) of one or more elongated trunks. Most systems possess either one (unilateral) or two (bilateral) horizontally positioned cordons. Figure 4.14 illustrates the development of a bilateral cordon-trained vine. Occasionally, the cordons are initially directed at right-angles (laterally) to the vine row. These subsequently branch into two cordons running in opposite directions, parallel to the row. This is termed quadrilateral cordon training. Vertical (upright) cordon systems are uncommon, due to apical dominance and shading combining to promote growth at the top. These features complicate maintaining a balanced cordon system. Vertical cordons are also poorly adapted to mechanized pruning and harvesting. Despite these problems, several obliquely angled cordon-trained systems were historically popular in northern Italy.

Horizontal cordons experience little apical dominance because of the uniform height of the buds. However, cordons experience considerable stress at their junction with the trunk. This necessitates one or more support wires to carry the weight of the shoot system and crop. Cordons are usually associated with spur pruning, with the bearing wood located uniformly along the cordon. This generates a canopy microclimate favorable to optimal fruit ripening. Higher yields can result from improved net photosynthesis, production of more fruitful buds, and increased nutrient reserves associated with an enlarged woody vine structure.

Location of the fruit in a common zone along the row also makes cordon training well suited to mechanical harvesting. Positioning the bearing wood in a narrow region above or below the cordon further facilitates mechanical pruning.

The disadvantages of cordon training include its higher costs, involving the use of a strong trellis and support wires; the time and expense required in its establishment; and the greater skill demanded in selecting and positioning the arms that bear the spurs or canes. In cool climates the more synchronous budbreak can increase the damage caused by late-spring frosts. Because cordon-trained vines tend to be more vigorous, they are commonly spur-pruned to minimize overcropping. This feature limits its use to varieties that bear fruit buds down to the base of the cane.

Cane pruning in association with cordon training is usually applicable only to strong vines capable of maturing a heavy fruit crop. The extensive woody component increases the number of base (noncount) buds that may become active, accentuating any tendency to overcrop. Thus, it is inappropriate for most French-American hybrids.

Because of the many advantages of cordon training, most newer training systems, such as the Geneva Double Curtain, Lyre and Scott Henry, employ it. Several older systems are also examples of cordon training, for example the Cordon de Royat (France), the Hudson River Umbrella (eastern North America), the Dragon (China), and pergolas (Italy).

Bearing Wood Length

As noted, the choice of spur vs. cane pruning often depends on the training system used. Conversely, the training system may be chosen based on the advantages provided by spur or cane pruning.

Cane pruning is especially appropriate for cultivars producing small clusters. These often benefit from the retention of the extra buds along the length of a cane. However, for the development of an optimal canopy microclimate, the variety must also possess relatively distant internodes to minimize shoot overcrowding. In addition, cane pruning enhances vine capacity by retaining more apically positioned buds. These are generally more fruitful than basally positioned buds (see Fig. 3.8). Cane pruning is particularly important, and spur pruning inappropriate, for cultivars that produce sterile base buds. Furthermore, cane pruning allows precise shoot positioning along the row, as well as the use of wide-topped trellises that extend both along and perpendicular to the row. Cane-pruned vines also tend to develop their canopy sooner in the season. This is particularly valuable for varieties susceptible to inflorescence necrosis, such as Gewürztraminer and Muscat of Alexandra, or with vigorous vines.

The disadvantages of cane pruning include the expense involved in trellising and tying the shoots. Because the crop develops from only a few canes, particular care must be taken in their selection. Thus, it is best performed by skilled workers. In addition, damage or death of even one cane can seriously reduce vine yield. A further complicating factor is the removal of the current year’s intertwined bearing wood. However, if the selected canes are tied down, a mechanical pruner can cut and remove most of the unwanted canes.

Bearing wood for the next season’s crop typically comes from shoots that develop from renewal spurs. The length of the bearing wood can result in uneven shoot development owing to apical dominance. This can lead to nonuniform canopy development and asynchronous fruit ripening. Arching or positioning the canes obliquely downward can often minimize apical dominance, but it places the bearing shoots and fruit in diverse environments. Converting a vine from spur to cane pruning often results in temporary overcropping.

Spur pruning tends to show properties that are the inverse of cane pruning. Because of its greater simplicity and uniformity, spur pruning requires less skill in selection. Because spur pruning tends to restrict fruit production to predetermined locations, it is particularly amenable to mechanical harvesting. If the spurs are located equidistant from the ground, the resulting absence of apical dominance favors uniform budbreak.

The tendency of spur pruning to limit productivity can be either beneficial or detrimental, depending on the vigor and capacity of the vine. Up to a point, decreased productivity may be compensated for by leaving more buds. Berry size is generally reduced with spur pruning. This can have the possible advantage of increasing the fruit surface area/volume ratio, thereby potentially enhancing wine flavor and color. Spurs are usually left with two count nodes, but occasionally may be reduced to one node for bountiful varieties such as Muscat Gordo. For other varieties, a combination of two- and four- to six-node spurs (‘finger and thumb’ pruning) has proven appropriate.

Restricting yield may be a desirable feature in cool climates or under nutrient-poor conditions, but tends to be less important in warm climates on deep rich soils. As noted, spur pruning is inappropriate for varieties that possess sterile base buds, or are susceptible to inflorescence necrosis. The delay in leaf production associated can result in increased competition between expanding leaves and young developing fruit. Delayed canopy production may also explain the higher concentration of methoxypyrazines (delayed degradation) in Cabernet Sauvignon. Finally, without removal of malpositioned spurs, shoot crowding is likely.

Commonly accepted norms for most V. vinifera cultivars are about 15 shoots per meter (positioned more or less equidistantly along the cordon), with each shoot bearing no more than 12–18 count nodes. These values can vary depending on features such as row spacing, vine density, soil fertility, water availability, likelihood of winter kill, rootstock and scion cultivar, and the flavor attributes desired or demanded by the winemaker. Yield to pruning weight ratios of 6–7:1 are generally desirable for most cultivars. For others, such as Pinot noir, this ratio may be high.

Shoot Positioning

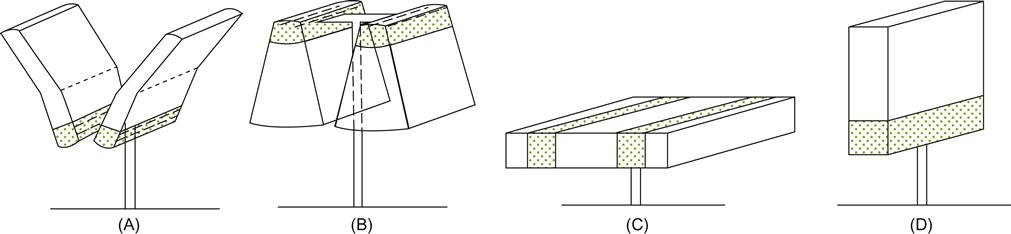

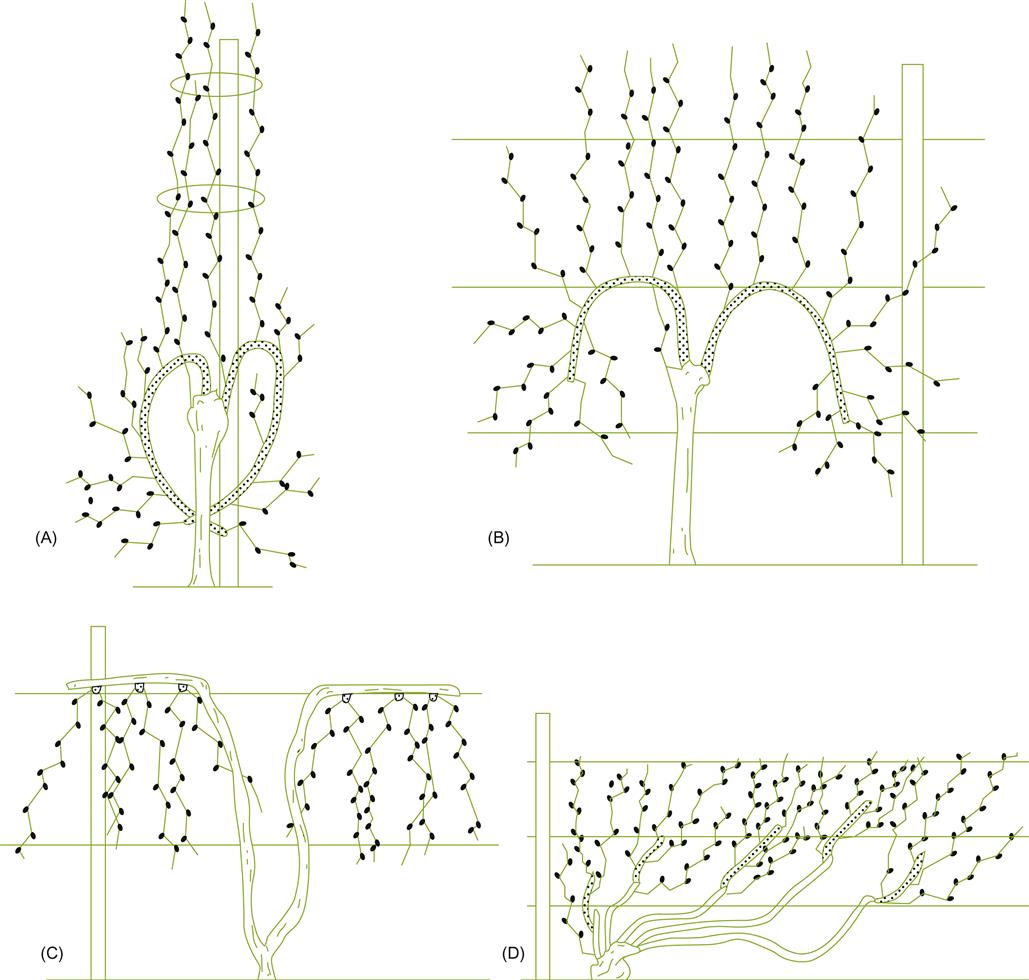

As with locating the vine’s woody structure, shoot placement can be used to promote vertical, horizontal, or inclined growth (Fig. 4.15). In addition, shoots may be prevented from or permitted or encouraged to arch and grow downward (Fig. 4.16).

The training of shoots vertically upward (by raising catch wires) is generally favored. It has several distinct advantages, including suitability with mechanical harvesting and pruning. The fruit’s central location on the vine provides largely unobstructed access to most vineyard practices, as well as providing some protection against hail, sunburn, strong winds, and bird damage. In addition, vertically trained vines generally are more vigorous and have higher capacities. Fruit ripening may occur earlier, even though flowering is delayed (Kliewer et al., 1989).

In contrast, pendulous or trailing growth commonly induces vine devigoration and reduced crop yield. This seems to result from a narrowing of the xylem vessels, reducing sap flow (Fig. 4.17). This influence is systemic and not limited to the bent regions. Trailing growth also requires little shoot tying, allowing flexibility that can aid mechanical harvesting. Nevertheless, vines need to be trained high, if not skirted, to avoid shoots trailing on the ground.

With low to moderately vigorous vines, arching or direct trailing can expose the basal portions of the shoot to direct sun exposure and wind. This favors cane maturation, bud fruitfulness, fruit maturation, and vine health. However, fruit sunburn is a potential problem in hot sunny climates. The tendency of most vinifera cultivars to grow upright complicates the formation of trailing vertical canopies, but is the natural habit with most labrusca cultivars.

Upright vertical canopies can be more expensive to maintain, and may generate heavy fruit shading if vine growth is vigorous. This may require hedging. Positioning long shoots in an upright position usually requires tying the shoots to several wires. This is costly, both in terms of material and complications with pruning (because of shoot entanglement in support wires). The latter can be minimized by trimming to short, stout shoots. Another potential disadvantage of upright canopies is the location of the fruit and renewal zones at the base of the canopy. However, with adequate canopy division, sufficient light reaches the base to permit adequate fruit ripening, inflorescence initiation, and cane maturation.

Canopy Division

A clearer understanding of canopy microclimate and its importance have been the major driving forces in the design of newer training systems. The first was the Geneva Double Curtain (GDC) (Shaulis et al., 1966). It has subsequently been modified for use with mechanical harvesting and pruning. Other examples are the Ruakura Twin Two Tier (RT2T) (Smart et al., 1990c), the Lyre (Carbonneau and Casteran, 1987), and the Scott Henry (Smart and Robinson, 1991). By dividing the canopy into separate components, sun exposure of the fruit and vegetation has been enhanced, fluctuation in berry temperature augmented, humidity decreased, and transpiration increased.