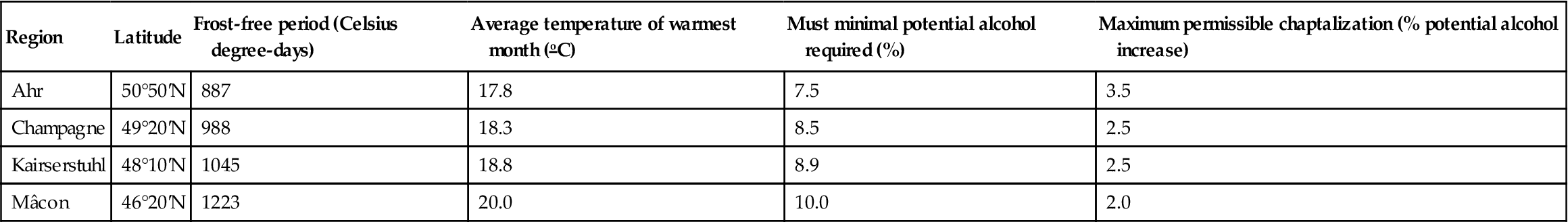

| Region | Latitude | Frost-free period (Celsius degree-days) | Average temperature of warmest month (oC) | Must minimal potential alcohol required (%) | Maximum permissible chaptalization (% potential alcohol increase) |

| Ahr | 50°50′N | 887 | 17.8 | 7.5 | 3.5 |

| Champagne | 49°20′N | 988 | 18.3 | 8.5 | 2.5 |

| Kairserstuhl | 48°10′N | 1045 | 18.8 | 8.9 | 2.5 |

| Mâcon | 46°20′N | 1223 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 2.0 |

Source: After Becker, 1977, reproduced by permission.

In addition to affecting the distribution of grape culture, climate also has a deciding influence on the potential for fine wine production. For example, most of the well-known wine regions of Europe are in mild to cool climatic zones. The absence of hot weather during ripening favors the retention of grape acidity. This gives the resulting wine a fresh taste and helps limit microbial spoilage. Cool harvest conditions also promote the development or retention of varietal flavors, and reduce the potential for overheating during fermentation. In addition, storage in cool cellars represses microbial growth that could induce spoilage. Finally, cool conditions have required that most vineyards be situated on south- or west-facing slopes, to obtain sufficient heat and light exposure. This incidentally has positioned vineyards on less-fertile, but better-drained sites. These features have restrained excessive vine vigor, while promoting fruit ripening and providing a degree of frost protection.

In contrast, the hot conditions typical of southern regions favor acid metabolism and a rise in juice pH. In addition to producing a flatter taste, the low acidity makes the wines more susceptible to oxidation and microbial spoilage. Although only approximately 0.004% of grape phenols are in a readily oxidized state at pH 3.5 (Cilliers and Singleton, 1990), they are so unstable that oxidative reactions occur readily. Even minor increases in pH can significantly increase the tendency of the wine to oxidize. Thus, protection from oxidation tends to be more critical in warm areas than in cooler regions. In addition, grapes tend to accumulate higher sugar contents under warm conditions. These increase the likelihood of premature cessation of fermentation, along with harvesting and fermentation under warm conditions. By retaining fermentable sugars, the wine is much more susceptible to undesirable forms of malolactic fermentation and microbial contamination. Warm cellar conditions further enhance the likelihood of spoilage.

Although advancements in viticulture and enology have increased the potential to produce a wider range of wine styles, prevailing conditions had a decisive and defining influence on the evolution of regional styles. Cool climates favored the production of fruity, tart, white wines. Such wines normally have been consumed alone, as sipping wines, before or after meals. More alcoholic white wines functioned primarily as food beverages. In warmer regions, red wines have tended to predominate. Here, the higher grape sugar content permitted the production of full-bodied wines, considered well suited to accompany meals. In hot Mediterranean regions, high-sugar and low-acid grapes favored the production of alcoholic wines that tended to oxidize readily. These features encouraged the development of oxidized, sweet, or flavored, high-alcoholic wines, appropriate for use as aperitifs or dessert wines.

Nevertheless, present-day viticultural and enologic techniques now permit the production of almost any wine style in southern regions. Equivalent techniques have not allowed the reverse situation in northern regions – an essentially unavailed opportunity.

Cultivars

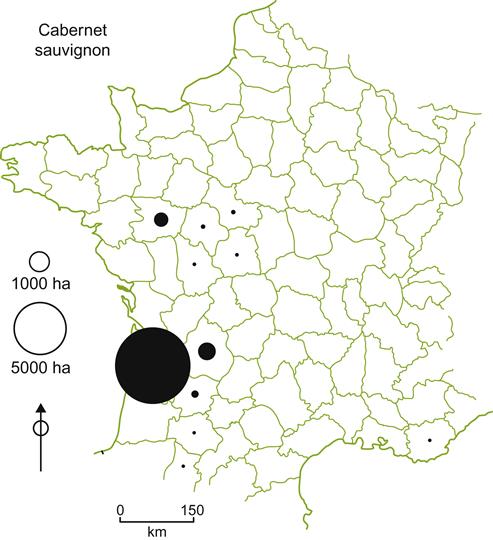

In Europe, the cultivation of grape varieties has tended to be highly localized (e.g., Fig. 10.13). This has given rise to the view that cultivar distribution reflects a conscious selection of cultivars, particularly suited to local climatic conditions. At sites where religious orders have produced wine for centuries, empirical trials may have found grape cultivars especially suited to the local climate. In most localities, however, wine was consumed within the year of its production, a situation incompatible with assessing aging potential (the sine qua non of wine quality). Also, varieties were commonly planted more or less at random within vineyards, as well as being harvested and vinified together. Thus, assessment of the relative quality of one cultivar versus another would have been essentially impossible. Finally, there is little documentation that could support, or refute, the continued cultivation of specific varieties in particular regions. Important exceptions are Riesling and Pinot noir, for which documentary information may go back to the 1400s. The best information concerning the development of indigenous cultivars comes from DNA analysis (see Chapter 2). Much of the information supports local evolution and retention. These cultivars probably arose from the incidental, uncoordinated propagation of better local strains, or were the product of accidental crossing with imported cultivars. Most selection would have been for obvious traits, such as compatibility with local climatic and soil conditions, higher sugar content, adequate acidity, better color, and aroma. Subtleties such as aging potential, development of delicate bouquets, and complexity would have been selected fortuitously. Only since the 1700s have conditions become more conducive to the intentional selection of premium-quality cultivars. Current DNA data also provide little information on when current cultivars evolved. Even some famous cultivars, such as Cabernet Sauvignon in Bordeaux, appear to have arisen comparatively recently, having documentary evidence only from the early 1800s (Penning-Rowsell, 1985).

Viticulture

In Europe, traditional cultivation has varied from dense plantings, with about 5000 to 10,000 vines/hectare, to interplanting with field crops, with trees as supports. In densely planted vineyards, each vine occupied about 1 m2, resulting in intervine competition and restrained vigor. This had the effect of reducing the level of pruning and manual labor required. Spacing was also compatible with manual or single, horse- or oxen-drawn equipment. Restrained vigor also resulted from the relegation of most vineyards to poorer soils, where cereal and other food crops would not grow well. This applied equally to sloped sites, which generally were (and are) ill-suited to annual, food-crop production. The relatively dry summer months, combined with dryland farming, equally tended to result in the early termination of vegetative growth. Combined with traditional pruning, fruit production was limited, but promoted early maturity. This had the distinct advantage of permitting an early harvest, important in regions where the onset of cold, rainy, autumn weather could ruin the crop. Hedging, when it became necessary to permit easier access for cultivation, incidentally favored nutrient direction to the fruit. In addition, hedging helped limit fruit shading, thus promoting improved coloration and flavor development.

The previous relegation of most grape culture to poorer or sloped agricultural sites, and the advantages of dense plantings, has regrettably led to the erroneous view that these conditions are necessary for grape quality. That these conditions reduce individual vine size and productivity, and favor fruit maturation, is not in question. However, as noted in Chapter 4, new training systems, involving canopy management, permit the cultivation of widely spaced vines on rich soils, without sacrificing fruit quality. In addition, fruit yield is increased and mechanization facilitated. Some of these techniques are being slowly integrated into standard European vineyard practice.

Enology

In Europe, more variation is probably found in winemaking procedures than in its viticultural practice. The differences reflect the wine styles that have evolved in response to climatic or market demands. In addition, major developments have occurred since the mid-nineteenth century. Previously, long-aging wines were matured in large-capacity wood cooperage. This applied to both white and red wines. Furthermore, red, and occasionally, white wines were produced by fermenting the juice with the seeds and skins for up to several weeks. The resulting wines were often partially oxidized and possessed higher volatile acidity than is now considered acceptable (Sudraud, 1978). Current trends have been to reduce the maceration period for both white and red wines. In addition, shorter maturation in wood is also favored. Premium white wines may receive up to 6 months in small oak cooperage, whereas premium reds often receive up to 2 years. Limited oak exposure may be used to preserve the fresh, fruity aroma of the wine. Greater emphasis is placed on the development of a reductive, in-bottle, aging bouquet than formerly.

Central Western Europe

France

France has the advantage of being the largest of the European nation states, combined with a multitude of climatic zones, and a diverse topography with few homogeneous regions. Most agricultural regions of similar geographic character are comparatively small and specialized in crop production. This multifarious nature is reflected in the country’s localized cultivar plantings and regional wine styles. Although no one soil type or geologic origin distinguishes French vineyards, many regions possess calcareous soils, or cover chalky substrata.

Although the effect of Appellation Control laws has tended to stabilize cultivar plantings in AOC- and VDQS-regions, marked changes in the varietal composition have occurred in nondesignated regions. For example, the proportion of French-American hybrid varieties rose dramatically after the phylloxera pandemic in the late 1800s, but has declined from about 30% in 1958 to less than 5% by 1988 (Boursiquot, 1990). It is supposedly to go to 0% by 2010. Remarkable in terms of worldwide trends is the increase in red cultivar plantings. In France, the hectarage of red V. vinifera cultivars has grown by 9% since 1958, whereas the planting of white cultivars has declined by 7%. White cultivars cover only about 30% of French vineyards. Of these, about 40% of the yield is used in the production of brandies, notably cognac and armagnac.

During the mid- to late-twentieth century, plantings of several well-known white cultivars decreased, whereas others came close to extinction. For example, Sémillon and Chenin blanc plantings declined by about 50%, and Viognier fell to only 82 ha (Boursiquot, 1990). Subsequently, Viognier cultivation has rebounded to over 5000 ha. Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc are other white cultivars to see significant cultivation increases, now taking second and third spots in white vineyard coverage. The most marked expansion in cultivar plantings has occurred with Syrah, whose hectarage has amplified so much that it is now the third most cultivated red grape in France. Other red varieties with significantly expanded plantings are Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet franc, Merlot (currently the most cultivated cultivar in France) and Pinot noir.

Although France is particularly famous for one of its sparkling wines (champagne), the vast majority of French wines are still (about 3 million hL vs. 40 million hL). As in other major wine-producing and -consuming countries, most French wines are red. Only a few sweet or fortified wines are produced. In contrast, vast quantities of brandy are produced.

Although wine is produced commercially in most regions of France, only a few regions are widely represented in world trade, notably Alsace, Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, Loire, and the Rhône. These regions are briefly discussed here, along with the less prestigious, but most important wine-producing region (in terms of volume), the Midi (Languedoc-Roussillon).

Alsace

Alsace is one of the most culturally distinctive regions of France. This reflects its German–French heritage and alternate French and German nationalities. Not surprisingly, wines from Alsace bear a varietal resemblance to German wines, but a stylistic similarity to French wines. It is also the one ‘French’ region where varietal origin is typically and prominently displayed on the label.

Alsatian vineyards run from north to south, along the eastern side of the Vosges Mountains (47°50′ to 49°00′N). The vineyard region possesses three structurally distinctive zones. The zone running along the edge of the mountains has excellent drainage, and benefits from solar warming of its shallow, rocky, siliceous soil. The foothill region is predominantly calcareous and generally possesses the best microclimate for grape cultivation. The soils of the plains are of more recent alluvial origin and possess excellent water-retention properties. Most vineyards occur at an altitude ranging between 170 and 360 m.

Alsace produces predominantly dry white wines, although some sweet and sparkling wines are produced. Yearly production averages about 0.9 million hL. Predominant cultivars are Gewürztraminer (20%), Pinot blanc (18%), Riesling (20%), and Silvaner (21%), with small plantings of Chasselas, Muscat, Auxerrois, Pinot gris, and Pinot noir.

Because of the coolish climate, grapes are often harvested high in acidity and the wines treated to promote malolactic fermentation. Local strains of lactic acid bacteria may be involved in generating some of the distinctive regional flavor found in many Alsatian wines.

Bordeaux

Bordeaux is the largest of the famous French viticultural regions (44°20′ to 45°30′N). It runs southeast for about 150 km along the banks of the Gironde, Dordogne, and Garonne Rivers. The vineyards cover about 112,000 ha, and annual production averages more than 6 million hL.

The Bordeaux region, located near the mouth of the Aquitaine Basin, is trisected by the junction of the Dordogne and Garonne Rivers to form the Gironde. These zones are divided into some 30 variously sized AOC areas. The best-known are those on the western banks of the Gironde (Haut Médoc) and the Garonne (Graves and Sauternes), and the eastern bank of the Dordogne (Pomerol and Saint-Émilion). Although Bordeaux is best known for its red wines, about 40% are white. White wines are produced primarily in Graves and Entre-Deux-Mers. The best vineyard sites are generally on shallow slopes or alluvial terraces adjacent to the Gironde, or low-lying regions along the Garonne and Dordogne Rivers at altitudes between 15 and 120 m.

Geologically, Bordeaux shows relatively little diversity. The bedrock is predominantly composed of Tertiary marls or sandstone, intermixed with limestone inclusions. The substrata are usually covered by alluvial deposits of gravel and sand of Quaternary origin, topped with silt. The soils are generally poor in humus and exchangeable cations. This is partially offset at better sites by the soil depth, often 3 m or more. Deep soils also provide vines with access to water during periods of drought, and good drainage in heavy rains.

The presence of extensive forests to the east and south protects Bordeaux vineyards from direct exposure to cool winds off the Atlantic. Nevertheless, proximity to the ocean and rivers provides some protection from rapid temperature changes, but limits summer warmth. Wet autumns occasionally cause difficulty during harvest, causing fruit to split, encouraging bunch rot, and diluting the sugar and flavor content of the grapes. Soil depth and drainage, along with local microclimate, appear to be more significant to quality than soil type or geologic origin (Seguin, 1986). This is not too surprising in a region of variable rainfall, where avoiding water logging and drought are problems and irrigation prohibited.

Unlike the wines of some French viticultural regions, Bordeaux wines typically are blends of wines produced from two or more cultivars. Depending on the AOC, the predominant cultivar can vary. In the Haut Médoc, the prevailing variety in red wines is Cabernet Sauvignon, whereas in Pomerol, it is Merlot. This partially results from Cabernet Sauvignon being more herbaceous on the clay soils of Pomerol, but less so on the sandy and gravelly soils of the Haut-Médoc. Maturing somewhat earlier and reaching a higher °Brix, Merlot is also more forgiving of the slower warming of the clay soils in Pomerol.

The presence and percentage of each cultivar in a vineyard often varies considerably among estates. In addition, the proportion used in any blend can vary annually. This flexibility permits the winemaker to compensate for yearly deficiencies in the base wines. Wine not incorporated into the premier blend may be bottled under an alternate (second) label, or sold to negotiants for use in preparing non-estate-bottled blends. The standard red cultivars are Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet franc, Petit Verdot, and Malbec. The first three constitute about 90% of red cultivar planting in Bordeaux. Although Cabernet Sauvignon is the best-known Bordeaux grape, and grown particularly in the Haut-Médoc, the related Merlot constitutes about 60% of the red grapes grown in Bordeaux. Petit Verdot and Malbec constitute only a small proportion of the hectarage.

White bordeaux also tends to be a blend of wines, based from two or more cultivars. In most areas, the predominant cultivar is Sauvignon blanc, with Sémillon coming in second. The 2:1 proportion of these cultivars is reversed in Sauternes and Barsac, in which sweet, botrytized, wines tend to be produced. In contrast to German botrytized wines, those from Bordeaux tend to be high in alcohol content (14–15%). Other permitted white cultivars are Muscadelle, Ugni blanc, and Colombard.

Because of good harbor facilities, proximity to the climate-moderating ocean, and a long-established association with discriminating, wine-importing countries, Bordeaux was well positioned to capitalize on the benefits of many winemaking developments. It was one of the first regions to initiate the modern practice of estate bottling and in-bottle aging (ceasing the practice of transporting wine in barrels). It also influenced the shift from tank to barrel maturation of wine. Except for some white wines, Bordeaux wines are tank- or vat-fermented, rather than in-barrel fermented, as in Burgundy. This situation reflects the relatively large size of many Bordeaux estates (châteaux), and their considerable production volume, in contrast to the plethora of small Burgundy producers. Most Bordeaux vineyards cover 5–20 ha, with some encompassing 40–80 ha.

Burgundy

Burgundy is often considered to include several regions beyond the strict confines of Burgundy proper (the Côte d’Or). The ancillary regions include Chablis, to the northwest, and the more southern areas of Challonais, Mâconnais, and Beaujolais. Their total production averages about 1.5 million hL/year.

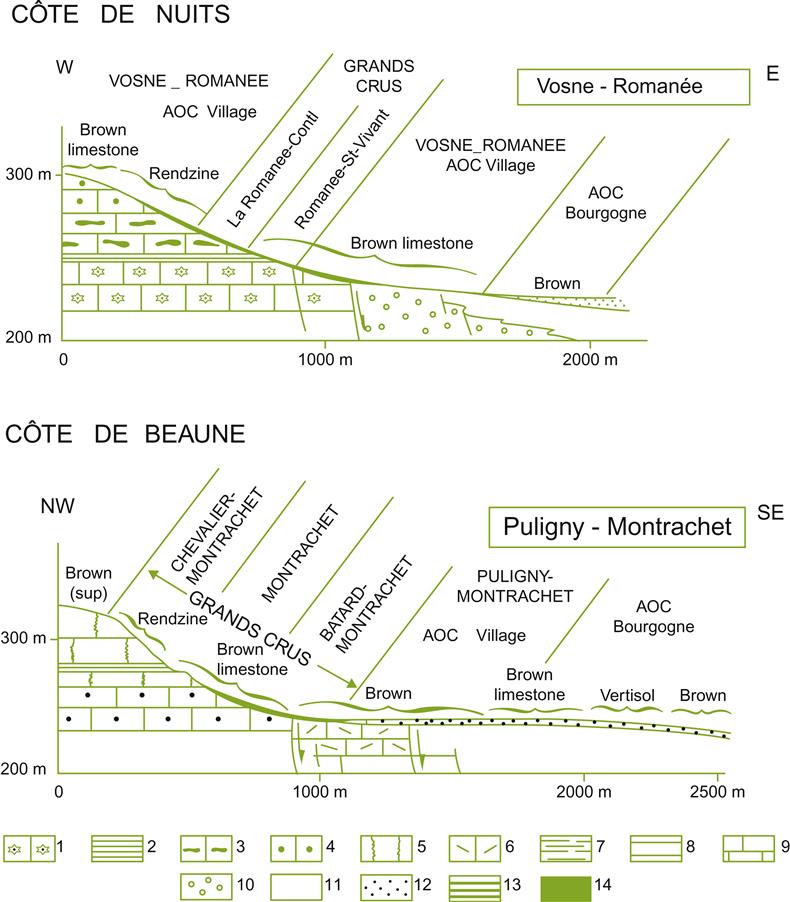

For all its fame, the Côte d’Or consists of just a narrow strip of land, seldom more than 2 km wide. The strip runs about 50 km from Chagny to Dijon (46°50′ to 47°20′N), in a northeasterly direction along the western edge of the broad Saône Valley. Although the vineyards are in a river valley, the Saône River is too distant (≥20 km) to have a significant effect on vineyard microclimate. A major physical feature favoring viticulture in the region is the southeasterly inclination of the valley wall. The porous soil structure and 5–20% slope promote good drainage and favor early-spring warming of the soil. Sites located partially up the slope, at an altitude between 250 and 300 m, are generally preferred (Fig. 10.14). Wine produced from grapes grown on higher ground or on the alluvial soils of the valley floor are generally regarded as inferior.

The Côte d’Or is divided into two subregions, the northern Côte de Nuits and the southern Côte de Beaune. Although there are exceptions, the Côte de Nuits is known more for its red wines, whereas the Côte de Beaune is more renowned for its white wines. This difference is commonly ascribed to the steeper slopes and limestone-based soils of the Côte de Nuits versus the shallower slopes and marly clays of the Côte de Beaune. Whether this is a case of mistaken correlation with causation is unknown.

The predominant cultivars planted in the Côte d’Or are both early maturing – Pinot noir and Chardonnay. These cultivars produce some of the best-known wines in the world. The cool climate slows ripening, a factor often considered to limit the loss of important varietal flavors, especially with Pinot noir.

Pinot noir can produce delicately fragrant, subtle, smooth wines of great quality under ideal conditions. Regrettably, optimal conditions occur notoriously rarely, even in Burgundy. Climatic factors seem to influence the flavor characteristics of Pinot noir wines more than other varieties (Miranda-Lopez et al., 1992). In addition, there is the infamous clonal diversity of Pinot noir. Further complicating an already difficult situation is the multiple ownership of most of the vineyards. Individual owners frequently possess a few rows of vines at numerous sites scattered throughout the region. Thus, grapes are fermented in small lots (to maintain site identity) by producers whose technical skill and equipment are highly variable. The wines are usually fermented and matured in older, small, oak cooperage. New oak is not considered the quality feature here that it is in Bordeaux.

Although Pinot noir matures early, it is not intensely pigmented. Thus, to improve color extraction, part of the crop may be subjected to thermovinification. However, the trend is a return to the tradition of cold maceration before fermentation. Frequent punching down of the cap during fermentation is usually necessary. Because of the onerous nature of punching down, considerable interest has been shown in using small-capacity (~50-hL) rotary fermentors. They frequently and automatically mix the pomace with the fermenting juice.

White wine is primarily produced from Chardonnay grapes, although some comes from Aligoté. If so, its presence must be designated on the label. Most white wines are fermented in barrels or small tanks. In the region of Macon, about 5–10% of the Chardonnay clones possess a muscat character. These are considered to give the region’s wines its distinctive aroma. Some rare, pink-skinned Chardonnay clones are grown in the northern part of the Côte d’Or.

Because of the cool climate, chaptalization is commonly required to reach the alcohol content considered typical (12–13%). Malolactic fermentation is promoted for its beneficial deacidification effect. As a consequence, the wines usually are racked infrequently. The associated long contact with the lees (sur lies maturation) tends to influence the character of Burgundian wines. It is also thought by some that the accumulation of yeasts and tartrate on the insides of the barrel limits an excessive uptake of oak flavor.

Except for a few large estates under single control, most sites in Burgundy are under multiple ownership. This leads to a bewildering variety of wines from a single appellation. Combined with limited production, relative to demand, this means that high prices abound despite often lackluster quality.

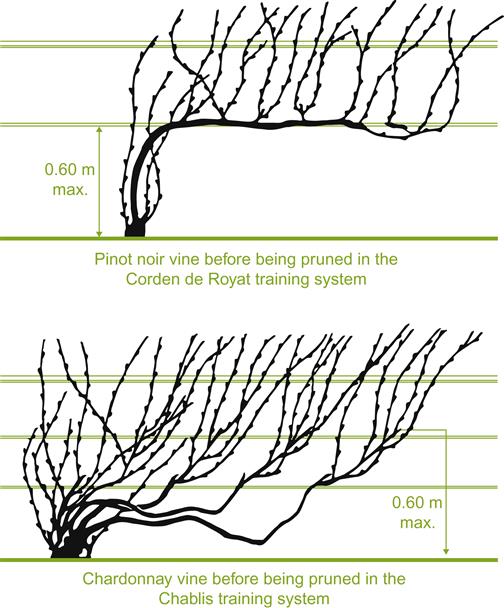

Chablis is a delimited region some 120 km northwest of the Côte d’Or (47°48′ to 47°55′N), just east of Auxerre. The region is characterized by a marly subsoil topped by a limestone- and flint-based clay. Sites located on well-exposed slopes (15–20%) are preferred to achieve better sun exposure and drainage. This is especially important because the region frequently suffers severe late-spring frosts. To further enhance protection against frost damage, the vines are trained low to the ground. Cordon de Royat and short-trunk double Guyot training systems are common (Fig. 10.15). Shoot growth seldom reaches more than 1.5 m above ground level. Thus, the vines remain close to heat radiated from the soil. The wines typically have little (subtle) fragrance and are more acidic than equivalent wines from central Burgundy. Chardonnay is the only authorized cultivar in Chablis. Yield varies from approximately 50,000 to 100,000 hL from 1500 ha planted with vines.

Beaujolais is the most southerly region in Burgundy (45°50′ to 46°10′N). It runs approximately 70 km as a broad strip of hilly land from just north of Lyon to just south of Mâcon. Most vineyards are located on slopes that are part of the eastern edge of the Massif Central. Here, the subsoil is deep and derived from granite and schist. The soil has considerable clay content and may be admixed with calcareous and black-shale deposits.

The most distinctive feature of Beaujolais has been its retention of an old production technique, closely resembling what is termed carbonic maceration (see Chapter 9). The procedure can generate wines that are pleasantly drinkable within weeks of production. It also results in the development of a distinctively fresh, fruity fragrance. A light style became very popular in the late 1960s – beaujolais nouveau. The red cultivar grown in the region, Gamay noir, responds well to carbonic maceration. Nevertheless, the technique can also yield wines that age well. These come predominantly from several villages in the northern portion of Beaujolais. Possibly to distance themselves stylistically from nouveau wines, most producers in these villages (crus) avoid mentioning Beaujolais on their labels. Beaujolais produces approximately 1 million hl wine/year, with more than 60% going into beaujolais nouveau.

Champagne

Champagne is probably France’s best-known wine, so much so that its name has been adopted as a synonym for sparkling wines, both to their benefit and chagrin.

The designated region of Champagne is quite large, covering about 30,000 ha (3% of French vineyard hectarage). The annual production of approximately 3 million hL is largely, but not exclusively, used for the production of sparkling wine. Most of the region lies east-northeast of Paris, spanning out equally on both sides of the Marne River for about 120 km. The other main section lies to the southeast, in the Aube département. Nevertheless, the greatest concentration of vineyards (~50%), and the sites most highly regarded, occur within the vicinity of Épernay (49°02′N). Here lie two prominences (falaises) that rise above the valley floor. The Montagne de Reims creates steep south- and east-facing slopes along the Marne River, and more gentle slopes northward toward Reims, some 6 km away. The Côte des Blancs, just south of Épernay, provides steeply sloped vineyard sites facing eastward. Soil cover is shallow (15–90 cm) and overlies a hard bedrock of chalk. Because of the slope, the topsoil needs to be periodically restored.

All three authorized grape cultivars are planted in the Épernay region, but the pattern of distribution varies among regions. The north and northeastern slopes of the Montagne de Reims are planted almost exclusively with Pinot noir, whereas along the eastern and southern inclines, both Pinot noir and Chardonnay are cultivated. On the eastern ascent of the Côte des Blancs essentially only Chardonnay is grown. The best vineyards are considered to lie between 140 and 170 m altitude (about halfway up the slopes) and possess eastern to southern orientations. Pinot Meunier may be grown on the falaises as well, but it is primarily cultivated along the Marne Valley and other delimited regions. In the valley, soils are more fertile and less calcareous than those of the falaises, but the area is more susceptible to frost damage. Although the cultivar is less preferred, about 48% of Champagne plantings are Pinot Meunier, with the rest divided about equally between Pinot noir and Chardonnay.

In Champagne, the most northerly French vineyard region, the vines are trained low to the ground. As previously noted, the best sites are on slopes that direct the flow of cold air away from the vines, and out onto the valley floor. The inclination of the sites can also provide conditions that enhance spring and fall warming. Although the slopes tend to be shallow, solar gain is still better than on level sites. Surprisingly, some excellent Pinot noir vineyards face northward, possibly improving winter survival by retaining more snow cover. In Champagne, optimal color development in the grapes and phenol synthesis are not essential to wine quality. The limited anthocyanin content simplifies the extraction of uncolored juice from red grapes. In addition, delayed fruit ripening probably aids the harvesting of healthy grapes – a prerequisite for producing white wines from red grapes. Pinot noir becomes very susceptible to bunch rot at maturity. With maturation delayed, the fruit remains relatively resistant to Botrytis infection. The significance of this is accentuated due to infection-favoring precipitation occurring predominantly in the late summer and fall.

That grapes are harvested somewhat immature is not the disadvantage it would be with other wine styles. It favors the production of wines low in alcohol content (~9%). This facilitates the initiation of the second, in-bottle fermentation, so integral to champagne production. If the acidity is excessive, deacidification can be achieved with malolactic fermentation or blending. Although training vines close to the ground makes mechanical harvesting impossible, this is acceptable because red varieties must be handpicked to avoid berry rupture. Mechanical harvesting would unavoidably result in some berry rupture, and the associated diffusion of pigment into the juice. Manual harvesting also permits the selective removal of diseased fruit before pressing.

Although many wines are ranked relative to their vineyard origin, champagnes are rarely vineyard designated. Champagnes are usually a blend of wines from different sites and vintages, to generate consistent house styles. Each champagne firm (house) creates its own proprietary style(s). The procedure also helps cushion variations in annual yield and quality, and tends to stabilize prices. In exceptional years, vintage champagnes may be produced. In vintage champagnes, at least 80% of the wine must come from the stated vintage.

Loire

The Loire marks the northern boundary of commercial viticulture in western France (~47°N), a full degree latitude south of Champagne. This apparent anomaly results from proximity and access of the Loire Valley to cooling winds off the Atlantic Ocean. The region consists of several distinct subregions, stretching from the mouth of the Loire River near Nantes, to Pouilly sur-Loire, some 450 km upstream. Most regions specialize in varietal wines produced from one or a few grape cultivars. Loire vineyards cover some 61,000 ha and annually produce approximately 3.5 million hL of wine.

Nearest the Atlantic Ocean is the Pays Nantais. It produces white wines from the Muscadet (Melon) and Gros Plant varieties. About 100 km upstream is Anjou-Saumur. Here, Chenin blanc is the dominant cultivar. Although Chenin blanc usually produces dry white wines, noble-rotted fruit produce sweet wines high in alcohol content (~14%). Rosés are also a regional speciality, coming from the Cabernet franc and Groslot varieties. In the central district of Touraine, light-red wines are derived from Cabernet franc and Cabernet Sauvignon (Chinon and Bourgueil), and white wines from Chenin blanc (Vouvray). In Vouvray, dry, sweet, (botrytized), and sparkling wines are produced. The best-known upper-Loire appellations are Sancerre and Pouilly sur-Loire. Their wines come primarily from Sauvignon blanc, although some wine is also made from Chasselas.

In the Loire Valley, vineyard slope becomes significant only in the upper reaches of the river, around Sancerre and Pouilly sur-Loire. Here, chalk cliffs rise to an altitude of 350 m. In most regions, moisture retention, soil depth, and drainage are the most significant factors influencing the microclimate (Jourjon et al., 1991).

Southern France

Progressing south from the union of the Saône and Rhône Rivers, just below Beaujolais, the climate progressively takes on a Mediterranean character. Total precipitation declines, and peak rainfall shifts from the summer to winter months. The average temperature also rises considerably. Here, red grapes consistently develop full pigmentation. Not surprisingly, red wines are the dominant type produced. Because of the longer growing season, cultivars adapted to such conditions predominate.

Syrah is generally acknowledged to be the finest red cultivar in southern France. Syrah has shown a marked increase in cultivation, following a decline associated with and following the phylloxera devastation of the 1870s. A similar fate befell many other cultivars, such as Roussanne, Marsanne, Viognier, and Mataro (Mourvèdre). They are also showing renewed cultivation. The fruitfulness of French-American hybrids, developed initially to avoid the expense of grafting in phylloxera control, induced further displacement of the indigenous varieties during much of the twentieth century. The shift of vine culture from cooler highland slopes to the hotter, rich plains resulted in overcropping and a reduction in wine quality. Thus, wines from southern regions, ranked as highly as Bordeaux in the mid-1800s, are little known today.

Generally, the best-known regions are those in the upper Rhône Valley. In regions such as the Côte Rôtie (45°30′N) and Hermitage (45°N), the best sites are on steep slopes. In the Côte Rôtie, ‘Syrah’ is often cofermented with 10% Viognier. This adds a distinctive fruitiness from the white cultivar. In some areas, the slopes are terraced, for example Condrieu. One exception is Châteauneuf-du-Pape (44°05′N). It is in the center of the lower Rhône Valley and situated on shallow slopes. The Rhône Valley possesses approximately 38,000 ha of vines and produces about 2 million hL wine/year.

In the upper Rhône, most of the wines are produced from a single cultivar. Progressing southward, the tendency shifts to the blending of several to many cultivars. Also, the predominant cultivar changes from Syrah in the upper Rhône, to Grenache in the lower Rhône, to Carignan in the Midi (primarily Languedoc and Roussillon).

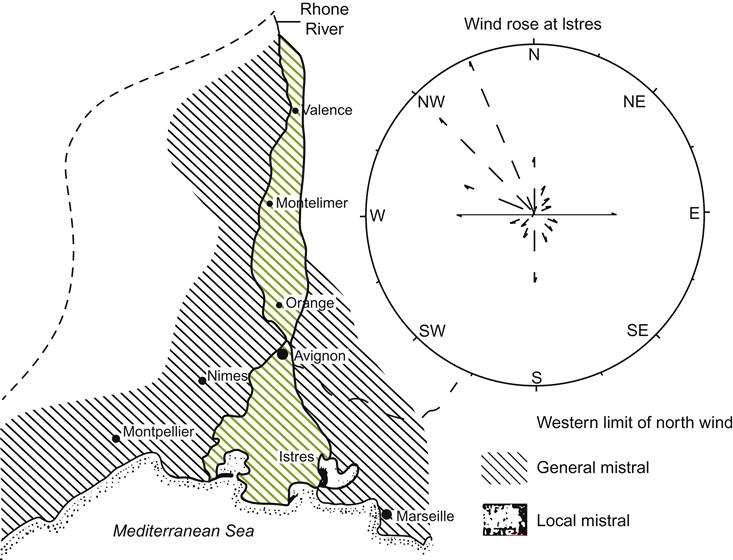

With a tendency for long, hot, dry summers in the south, vegetative growth ceases early, producing short sturdy shoots. This, and the value of fruit shading, have promoted the continued use of Goblet training. Its bushy form was presumed to minimize water loss by ground shading. However, data from van Zyl and van Huyssteen (1980) counter this view. The system also obviates the need for a trellis and yearly shoot positioning. In addition, the short vine stature and sturdy shoots are less vulnerable to the strong, southerly, mistral winds, common in the lower Rhône and Rhône Delta (Fig. 10.16). Windbreaks are a common feature in the area.

Although the upper Rhône Valley, and to a lesser extent the lower Rhône, produces several wines of international reputation, this is rare in the Midi. Only some sweet wines, such as Banyuls, appear to have gained an international clientele. Much of the nearly 33 million hL production is sold in bulk or converted to industrial alcohol. Grapes are the single most important crop in the region.

Improvement in wine quality in the Midi will depend on planting better cultivars, eliminating overcropping, and adopting mechanized winemaking equipment and techniques. However, this is difficult to achieve in an economically depressed area, where most vineyards are small and too often owned by poorly trained producers. The situation is not aided by a mentality accustomed to subsidized prices for wine destined largely for distillation into industrial alcohol. Amazingly, this regrettable situation is not due to a lack of research facilities. One of France’s premier centers for studying wine is located in Montpellier. Access to, and application of, knowledge are not synonymous.

Germany

Germany’s reputation for quality wines far exceeds its significance in terms of quantity. It produces only about 3% of the world’s supply. However, much of the international repute comes from a small quantity of botrytized and drier Riesling Prädikat wines. Nevertheless, much fine wine comes from the lesser-known cultivar Muller-Thurgau. The reputation of German wines, despite the high latitude of its vineyards, partially reflects the high technical skill of its grape growers and winemakers, and the assistance provided by the many excellent research facilities throughout the country.

The high latitude of Germany’s vineyard regions (47°40′ to 50°40′N), and the resulting cool climate and relatively short growing season, favor the retention of fruit flavors and refreshing acidity. The ‘liability’ of low °Brix levels has been turned into an asset by producing naturally light, low-alcohol wines (7.5–9.5%). With the advent of sterile filtration in the late 1930s, crisp semi-sweet wines with fresh fruity and floral fragrances could be produced consistently and in quantity. These wines ideally fit the role they have often played in Germany, namely, light sipping wines consumed before or after meals. The botrytized specialty wines have for centuries been favorite dessert replacements. As befits their use, more than 85% of all German wines are white. Even the red wines come in a light style, often more resembling a rosé than standard red wines. Although most German wines generally are not considered ideal meal accompaniments, several producers are developing dry versions to meet the growing demand for this style in Germany.

German viticultural regions reflect the typical European regional specialization with particular cultivars. Nevertheless, in only a few regions does one cultivar predominate. In addition, modern cultivars are grown extensively. For example, Müller-Thurgau is the most extensively grown German cultivar (24%), ahead of the more well-known Riesling (21%). Nearly half the vineyards are planted with varieties developed in the ongoing German grape-breeding programs. Their earlier maturity, higher yield, and floral fragrance have made them valuable in producing wines at the northern limit of commercial viticulture. Both new cultivars, and clonal selection of established varieties, have played a significant role in raising vineyard productivity, without resulting in a loss in wine quality. Of red cultivars, the most frequently planted are Spätburgunder (Pinot noir) and Portugieser.

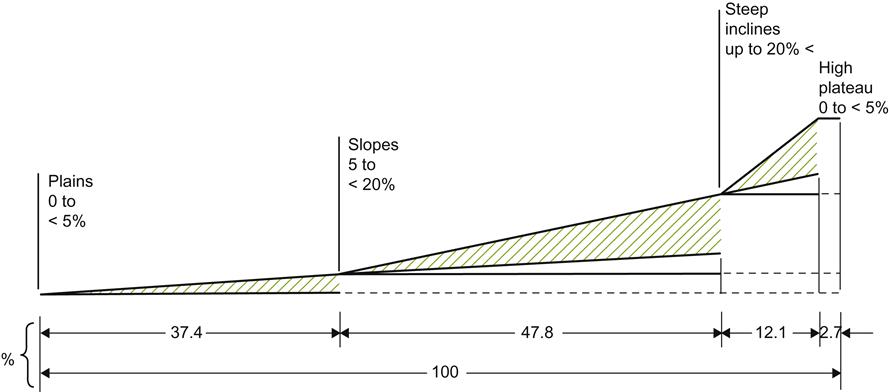

One of the most distinctive features of German viticulture is the high proportion of vineyards on slopes (Fig. 10.17). This has meant that viticulture did not compete with other crops for land. Most of the famous sites are on valley walls, unsuitable for other crop cultivation. Although steep inclinations may produce favorable microclimates for grape growth, they were incompatible with most mechanized vineyard activities until recently. Thus, to facilitate viticulture, vineyard consolidation has been encouraged in several regions, as well as structural modification to produce terraces suitable for mechanization (Luft and Morgenschweis, 1984).

Formerly, vines were trained on short trunks (10–30 cm), as is still common in northern France. This has changed to trunks between 50 and 80 cm high. Not only is cultivation and harvesting easier with taller trunks, but the vines are less susceptible to disease, due to better air circulation and surface drying of the fruit and foliage. Trellising also helps position shoot growth and leaf production for optimal light exposure. This is important because long summer days (≥16.5 h) and abundant precipitation promote rapid development of a large photosynthetic assimilation area. In addition, by locating shoot-bearing wood low on the vine, and directing shoot growth upward, grapes are kept as close as possible to heat radiated from the soil. Only on particularly steep slopes, notably along the Mosel–Saar–Ruwer, are vines still trained to individual stakes with two arched canes.

On all but the steepest inclines, narrow-gauge tractors permit many vineyard activities to be mechanized. In addition, small tractors are required if they are to pass amongst densely planted vines.

Although German vineyard regions have a cool, temperate climate, the southernmost viticultural portions of Baden possess warmer and wetter conditions than elsewhere in Germany. They occur on the windward side of the Black Forest, across from Alsace. The Baden region consists of a series of noncontiguous areas spanning 400 km, from the northern shores of Lake Constance (Bodensee) (47°40′N) to the Tauber River, just south of Würzburg (49°44′N). Most of the vineyards occur in the 130-km stretch between Freiburg and Baden-Baden. The most favored sites are located on the volcanic slopes of the Kaiserstuhl and Tuniberg.

Spätburgunder (Pinot noir) is often grown on the well-drained south-facing slopes of Baden, and produces about 90% of Germany’s Spätburgunder wines. On heavier, loamy soils, Müller-Thurgau, Ruländer, and Gutendal (Chasselas) tend to predominate. Gutendal is especially well adapted to the more humid portions of the region. Wine production is largely under the control of several large, skilled cooperatives. The region has been particularly active in vineyard consolidation and terrace construction.

Directly north of Alsace, on the western side of the Rhine Valley, is the Rheinpfalz. It continues as the Rheinhessen to where the Rhine River turns westward at Mainz. Combined, these regions possess almost one-half of all German vineyards (48,000 ha), and produce most of the wine exported from Germany. The region consists largely of rolling fertile land at the northern end of the Vosges (Haardt) Mountains. Liebfraumilch is the best-known regionally exported wine. The regions span latitudes from 49° to 50°N.

As with other German wine regions, the best vineyard sites occupy south- and east-facing slopes, and are planted primarily with Riesling. Occasional black basalt outcrops, as found around Deidesheim, are thought to improve the local microclimate and provide extra potassium. The longer growing cycle of Riesling demands the warmest, sunniest microclimates to reach full maturity. In the Rheinpfalz, Riesling constitutes the second most commonly cultivated variety (17%), whereas in the Rheinhessen, it covers only 7% of vineyard hectarage. In both regions, Müller-Thurgau is the dominant cultivar, covering about 22% of vineyard sites. Many new cultivars are grown and add fragrance to the majority of wines produced. Soil type varies widely over both regions. Combined, the regions are up to 30 km wide and together stretch about 150 km in length.

At Mainz, the Rhine River turns and flows southwest for about 25 km until it turns northwest again past Rüdesheim (~50°N). Along the northern slope of the valley are some of the most famous vineyard sites in Germany. The region, called the Rheingau, possesses approximately 3000 ha of vines. The soil type varies along the length of the region and up the slope. Along the riverbanks are alluvial sediments. Further up, the soil becomes more clayey, and finally changes to a brown loess. The soil is generally deep, well-drained, and calcareous. Although soil structure is important, factors such as slope aspect and inclination, wind direction and frequency, and sun exposure are of equal or greater importance. Because the river widens to 800 m in the Rheingau section, it significantly moderates the climate. Mists that arise from the river on cool autumn evenings, combined with dry sunny days, favor the development of noble-rotted grapes (edelfäule). This development is crucial to the production of the most prestigious wines of the region.

Riesling is the predominant cultivar grown in the Rheingau (82%), followed by Spätburgunder (6.7%). The latter is cultivated almost exclusively on the steep slopes between Rüdesheim and Assmannshausen, where the course of the river turns northward again. On less-favored sites, new cultivars such as Müller-Thurgau, Ehrenfelser, and Kerner may be grown.

Vineyards continue to be planted along the slopes of the Rhine and its tributaries up to Bonn, as the river continues its flow toward the Atlantic. Red wines from Spätburgunder and Portugieser are produced along one of the tributaries, the Ahr. Heat retained by the volcanic slate and tufa of the steep slopes may be crucial in permitting red wine production in this northerly location (50°34′N). However, most of the region, called the Mittelrhein, cultivates Riesling along its steep banks. As in the more southerly regions of the Nahe and Neckar valleys, most of the wine is sold locally and seldom enters export channels.

A major artery joining the Rhine at Koblenz is the Mosel River. Along the banks of the Mosel are vineyards with a reputation as high as those of the Rheingau. The Mosel-Saar-Ruwer region stretches from the French border to Koblenz (49°30′ to 50°18′N) and has 13,000 ha of vines. Although the overall orientation is northwest, the Mosel snakes extensively for 65 km along its middle section. This section possesses many steep slopes (Plate 10.1) with southern aspects between the Eifel and Hunsruck mountains. This stretch of the river, and its tributaries, the Saar and Ruwer, are planted almost exclusively with Riesling. The central section, called the Mittelmosel, is blessed with a slate-based soil that favors heat retention. Thus, not only does the soil possess excellent drainage, but it also provides frost protection and promotes grape maturation. The Mittelmosel contains most of the region’s most famous vineyards.

The final German river valley, particularly associated with viticulture, is the Main. The Main flows westward and joins the Rhine at Mainz, the eastern beginning of the Rheingau. Vineyards in the Main Valley are upstream and centered around Würzburg (~49°N). The region, called Franken, is noted for Silvaner wines and its squat green bottle, the bocksbeutel. Franken is notable in its minimal use of slim wine bottles. Although best known for Silvaner wines, Franken’s has a continental climate more suited to the cultivation of the newer, earlier maturing cultivars, such as Müller-Thurgau. The latter covers almost half of the 5500 vineyard hectarage in Franken, whereas Silvaner covers only about 20%.

Switzerland

Although a small country, Switzerland has vineyards covering approximately 15,000 ha, with an annual wine production of close to 1.0 million hL. The ethnic diversity and distribution of its inhabitants are reflected in the wines it produces. Along the northern border, Switzerland produces light wines resembling those in neighboring Baden. In the southwest, wines are more alcoholic, similar to those across the frontier in France. In the southeast, the Italian-speaking region specializes in producing full-bodied red wines.

Although the southern vineyard regions of Switzerland parallel the Côte de Nuits (~46°30′N), the higher altitude, between 400 and 800 m, produces a cooler climate than its similar latitude with Burgundy might suggest. Consequently, most vineyards are on south-facing slopes, adjacent to lakes or river valleys. The southwestern vineyards of the Vaud and Valais hug the northern slopes of Lake Geneva and the head of the Rhône River, whereas those of the west occur along the eastern slopes of Lake Neuchâtel and associated tributaries. In northern Switzerland, the vineyards congregate around the Rhein, Rheintal, and Thurtal river valleys and the south-facing slopes of Lake Zürich. In the southeast (Ticino), vines embrace the slopes around Lakes Lugano, Maggiore, and their tributaries. All of the regions are associated with headwaters of three great viticultural river valleys, the Rhine, the Rhône, and the Po. As in Germany, the use of steep slopes has avoided competition with most other agricultural uses.

Because of frequent strong winds, the shoots are tied early and topped to promote stout cane growth in most Swiss vineyard regions. Abundant rainfall has fostered the use of open canopy configurations to favor foliage drying and minimize fungal infection. Soil management typically employs the use of cover crops or mulches to minimize the need for herbicide use and for erosion control. There is increasing interest in the use of several French-American hybrids. Their greater disease resistance is compatible with the growing popularity of organically produced wines (Basler and Wiederkehr, 1996).

The moist, cool climate usually necessitates chaptalization if standard alcohol levels are to be achieved. Malolactic fermentation is used widely to reduce excessive wine acidity. The short growing season requires the cultivation of early-maturing varieties, such as Müller-Thurgau in the north and Chasselas doré in the southwest. There has been a recent trend to replace Chasselas with other indigenous cultivars, such as Petit Arvine, Cornalin, Armine, and Humagne Rouge. Although many white cultivars are grown, there is a shift toward red wine production. The demand has resulted in a marked increase in the planting of Pinot noir in the north and both Pinot noir and Gamay in western regions. In the southeast, Merlot is the dominant red cultivar.

Czech Republic and Slovakia

The former Czechoslovakia covers a primarily mountainous region, divided along most of its length by the Carpathian Mountains to the east and the Moravian Heights and Sumava in the west. The latter separate the small northern vineyard area of Bohemia (50°33′N) from the warmer, more protected, southern regions of Moravia and Slovakia (~48°N).

In Bohemia, the vineyards are located on slopes along the Elbe River Valley, about 40 km northwest of Prague. Low altitude and the use of a variety of rootstocks differentially affecting bud break help to cushion the influence of the cool and variable climate of the region (Hubáčková and Hubáček, 1984). The predominant cultivars are Riesling, Traminer, Müller-Thurgau, and Chardonnay. The small size of the viticultural region, and its proximity to Germany, probably explain the resemblance of the cultivars and wine styles to those of its neighbor to the west.

In the south-central portion of the Czech Republic, most vineyard sites are positioned on the slopes of the Moravia River valley, north of Bratislava. The Moravian vineyards (12,000 ha) cultivate primarily white varieties, such as Riesling, Traminer, Grüner Veltliner, and Müller-Thurgau, similar to their Austrian neighbors. Small amounts of red wine are produced from Portugieser, Limberger, and Vavřinecké.

Most of the Slovakian vineyards (35,000 ha) adjoin the Danube basin, along the southern border of the country. In common with adjacent viticultural regions, most of Slovakia’s wines are white. Although many western European cultivars are grown, the junction of the region with eastern Europe is equally reflected in the cultivation of eastern varieties. This is particularly marked in the most easterly viticultural region. The area is an extension of the Tokaj region of Hungary. Here, the varieties Furmint and Hárslevelű are the dominant cultivars. The wines are similar in style to those of the adjacent Hungarian region.

Austria

The mountains of the region restrict the 48,000 ha of Austrian vineyards to the eastern flanks of the country. Much of the wine-growing area is in low-lying regions along the Danube River and Danube basin to the north (~48°N) and the Hungarian basin to the east. A small section, Steiermark, is located across from Slovenia (~46°50′N).

The best-known viticultural regions are the Burgenland (Rust-Neusiedler-See), Gumpoldskirchen, and Wachau. The Burgenland vineyards adjacent to the Neusiedler See (47°50′N) occur on rolling slopes at an altitude between 150 and 250 m. The shallow, 30-km-long lake creates autumn evening mists that, combined with sunny days, promote the development of highly botrytized grapes and lusciously sweet wines. Here, Riesling, Müller-Thurgau, Muscat Ottonel, Weissburgunder (Pinot blanc), Ruländer, and Traminer predominate. Vineyards located north and south of Vienna produce light dry wines. These are derived primarily from the popular Austrian variety Grüner Veltliner. Other varieties grown are Riesling, Traminer, and in Gumpoldskirchen, south of Vienna, the local specialities Zierfändler and Rotgipfler. Most of the vineyards in the latter region are positioned on southeastern slopes at an altitude between 200 and 400 m. About 65 km west of Vienna is the Wachau region. Vineyards in Wachau lie on steep, south-facing slopes of the Danube, just west of Krems. They occur at altitudes of between 200 and 300 m. The predominant cultivar is Grüner Veltliner. Although most Austrian wine is white, some red wine is produced. The most important red cultivar is the new variety Zweigelt (Mayer, 1990).

Austria annually produces approximately 2.5 million hL wine, but only a small proportion is exported. Most of the production is consumed early and locally. As in Germany, the wines usually have the varietal origin and grape maturity noted on the label. The designations from Qualitätswein to Trockenbeerenauslese are the same, except that the requirements for total soluble solids (Oechsle) are higher than in Germany.

United Kingdom

Although the United Kingdom is not a viticulturally important region on the world scene, UK vineyards indicate that commercial wine production is possible up to 54°45′N. The extension of wine production further north than German vineyards results from both the moderating influence of the Gulf Stream and the cultivation of early-maturing varieties, notably Müller-Thurgau and Seyval blanc. Other potentially valuable cultivars are Auxerrois, Chardonnay, Madeleine Angevine, and several new German cultivars. Improved viticultural and enologic practices have also played an important role in reestablishing winemaking in England. The cooling of the European climate in the thirteenth century (Le Roy Ladurie, 1971), combined with French-speaking Norman rule, which also controlled Bordeaux and its vineyards, probably explain the demise of English viticulture during this period.

Southern Europe

Although French and German immigrants were seminal in the development of much of the wine industry in the New World, the basic practices used in Central Europe were originally introduced from Southern Europe. During the Classical period, Greece and Italy were considered, albeit by themselves, to be the most famous wine-producing countries. With the fall of these civilizations, economic activity languished for almost a millennium. The result was a marked reduction in both the quantity and quality of wine production throughout Europe.

At the end of the medieval period, the rebirth of centralized governments and improved economic conditions north of the Alps favored the renewed production of fine wine. In contrast, grapes continued to be grown admixed with other crops in much of southern Europe. In Italy, this occasionally followed an old technique used in Roman times, where vines were trained up trees, intermingled amongst field crops (Fregoni, 1991). In the absence of monoculture, yield control as well as fruit quality were neither possible, nor seemingly of importance. Subsistence farming was incompatible with the exacting demands of quality viticulture. In addition, lack of a large, discriminating, middle class provided little incentive for the production of much more than minimal quality wines for washing down food. Only in those parts of Italy, associated with the rebirth of trade, and eventually the Renaissance, did the production of better wine again begin to become lucrative. Regrettably, political division at the local scale, associated with the rise of aggressive nation-states in Central and Western Europe, resulted in the periodic return to economic stagnation, social devastation, political turmoil, and disruption in quality wine production.

In Greece, repeated invasion by oppressive foreign regimes severely restricted the redevelopment of a vibrant wine industry, as in much of eastern Europe. Although Spain and Portugal avoided similar fates, their initial colonial prowess did little to produce lasting economic benefits at home, at least in enology and viticulture. The absence of a growing, prosperous, middle class may explain why wine skills languished in much of southern Europe until recently.

Mediterranean wines tended to be alcoholic, oxidized, and low in total acidity, but high in volatile acidity. Inadequate temperature control often resulted in wines with residual sugar contents favorable to spoilage. In contrast, wines produced north of the Alps tended to be more moderate in alcohol, fresh, dry, flavorful, and more microbially stable.

With the subsequent growth and spread of technical skill, the standard of winemaking has improved dramatically throughout all of southern Europe. Regrettably, implementation of many advances was limited because the economic returns were, until comparatively recently, insufficient to support major improvements. Better-known regions, producing wines able to command higher prices, were those best and first able to benefit from technical advances.

Italy

Italy and France often exchange top ranking in terms of grape and wine produced. Annual production has fallen considerably over the past 30 years, and now stands at about 45–50 million hL, but still accounts for about one-fifth of world production. Italy’s vineyard area is about the same as France’s (868,000 vs. 887,000 ha), but a higher proportion involves table grapes in Italy than in France (7% vs. 2%).

Italian vineyards are predominantly exposed to a Mediterranean climate, receiving most of the rain during the winter months. Nevertheless, nearly one-third of Italy (the Po River valley and the Italian Alps) possesses a more continental climate, without a distinct dry summer season. Also, the Apennines running down the middle of the Italian Peninsula, provide a cooler, more moist climate along leeward slopes of the mountains. The mountains in Italy produce considerable variation in yearly precipitation, from more than 170 cm on some slopes to less than 40 cm in southern areas. The predominantly north–south axis of Italy results in coverage of over 10° latitude, from 46°40′N, parallel with Burgundy, to 36°30 N, parallel with the northern tip of Africa. Nonetheless, a common feature of the country, apart from mountainous regions, is a mean July temperature of between 21 °C and 24 °C. Combined with a wide range of soil types and exposures, Italy possesses an incredible variety of viticultural microclimates.

In addition, Italy possesses one of the largest and oldest collections of grape varieties, plus about a 2600-year-old history of wine production. Thus, it is not surprising that Italy produces an incredible range of wine styles. Many regions produce several white and red wines in dry, sweet, and slightly sparkling (frizzante) versions. Although this may give confusion to those outside the region, it supplies a diverse range of styles desired by the local clientele. Many regions also produce limited quantities of wine, using distinctive, often ancient, techniques not found elsewhere.

The diversity of wine styles found in many Italian regions has probably hindered their acceptance internationally. Also confusing to many consumers is a lack of consistency in wine designation. In some regions, the wines are varietally designated, whereas in others by geographic origin, producer, or by mythological names. This situation may be explained by the long division of Italy into many separate city-states, duchies, kingdoms, and papal dominions, and the all-too-frequent incursion of foreign powers. The difficulty of land transport within a divided Italy, combined with a stagnant economy and limited middle class, impeded wine shipments throughout the country. As a consequence, improvements in viticultural and enologic practice, and the development of a uniform wine-designation system, came only recently.

For many centuries, poverty in most Italian regions resulted in subsistence farming. Only in a few regions, such as northwestern Italy and Castelli Romani in central Italy, was pure viticulture practiced. Today, the old polyculture has essentially vanished, and Italian viticulture is similar to other parts of the world. There is, however, a remarkable range of training systems in practice, many used only locally. In several areas, high pergola or tendone training is used, either to favor light and air exposure for disease control, or to limit sun- and wind-burning of the fruit. Low training is more common in the hotter, drier south. This may minimize water stress and promote sugar accumulation, desirable in the production of sweet fortified wines. Irrigation may be practiced in southern regions, where protracted periods of drought occur during the hot summer months.

In most regions, enologic practice is now modern. It has had a profound effect on improving wine quality. Modernization is also affecting a shift from the traditional long maturation in large wooden cooperage (≥5 years) to shorter aging in smaller cooperage (≤2 years). There is considerable debate concerning the relative merits of oak flavor in Italian wine. Nevertheless, several unique and distinctive winemaking styles are practiced. Regrettably, most have been little investigated scientifically. Hopefully, they will be studied adequately before they potentially fall victim to standardized winemaking practices.

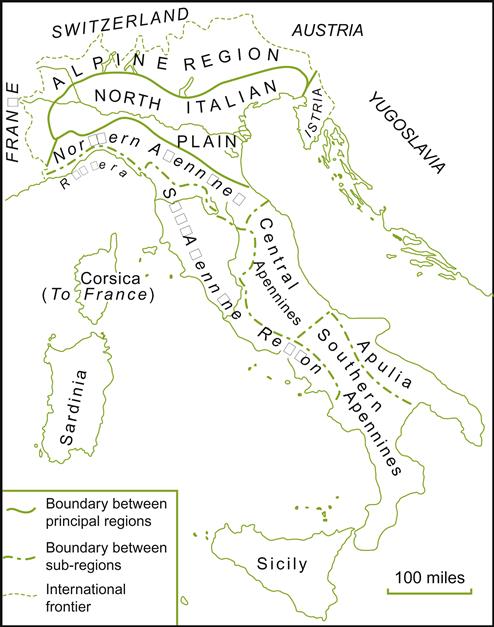

Northern Italy

Much of the Italian wine sold internationally, except for that sold in bulk, comes from northern Italy. Most of the regions involved are situated on the slopes of the Italian Alps, or along the North Italian Plain (Fig. 10.18). These regions possess a mild continental climate, without a distinct drought period. The arch of the Alps, which forms Italy’s northern frontier, usually protects the region from cold weather systems coming from the north, east, and west.

The most northerly area is Trentino-Alto Adige. Although the vineyard area covers only about 13,000 ha, and annually produces approximately 1.5 million hL wine, production in Trentino-Alto Adige constitutes almost 35% of Italy’s total bottled-wine exports. The region also leads in the proportion of DOC appellations. Unlike most Italian wines, the label usually indicates the name of the grape variety used, associated with its regional origin.

Trentino-Alto Adige contains a wide diversity of climatic and soil conditions. The climate ranges from Alpine in the north to subcontinental, and finally sub-Mediterranean along the coast. Soils equally vary considerably, depending largely on the slope and altitude. Along the valley floor, the soil is generally alluvial and deep, shifting to sandy clay-loam on the lower slopes. On the steeper, upper slopes, the soil is shallow with low water-holding capacity.

The vineyards in the northern half of the Trentino-Alto Adige often line the narrow portion of the Adige River valley on steep slopes, at altitudes between 450 and 600 m. The region called Alto Adige (South Tyrol) stretches 30 km, both north and south from Bolzano (46°31′N). The considerable German-speaking population of the region is reflected in the style and care with which the wines are produced. The region produces many white and red wines. Whites may be produced from cultivars such as Riesling, Traminer, Silvaner, Pinot blanc, Chardonnay, and Sauvignon blanc. The regions red wines are frequently derived from distinctively local cultivars, such as Schiava and Lagrein, or French cultivars, such as Pinot noir and Merlot.

In contrast to Alto Adige, Trentino covers a 60-km strip of gravelly alluvial soil on the valley floor that widens 20 km north of Trento (46°04′N). Here the vineyards are no higher than 200 m in altitude. The most famous wine of the region comes from the local red cultivar Teroldego. The vines are trained on supports resembling an inverted L (pergola trentino). This is designed to increase canopy exposure to light and air. Many different white and red wines are produced, primarily from the same varieties cultivated in Alto Adige. In addition to standard table wines, the region produces a vin santo (see Chapter 9) from the local white cultivar Nosiola, and considerable quantities of dry sparkling wine (spumante) from Pinot noir and Chardonnay.

Veneto is the major wine-producing region adjacent to Trentino, where the Alps taper off into foothills and the broad Po Valley. The vineyard area in Veneto covers some 80,000 ha and annually produces approximately 8 million hl wine. Internationally, the best-known wines come from the hilly country above Verona (45°28′N), where the Adige River turns eastward. The dry white wine Soave comes primarily from the Garganega grape, cultivated on the slopes east of the city. The vineyards producing the grapes used in Valpolicella are situated north and east of Verona, whereas those involved in making Bardolino are further west, along the eastern shore of Lake Garda. Both red wines are produced primarily from Corvina grapes, with slightly different proportions of Molinara and Rondinella. Negrara may also be part of the Bardolino blend. Grapes for Valpolicella are generally grown on higher ground (200–500 m) than those for Bardolino (50–200 m), and produce a darker red wine. The most distinctive Valpolicellas come from specially selected, and partially dried grape clusters, using the recioto process (see Chapter 9). During vinification, fermentation may be stopped prematurely to retain a detectable sweetness, or continued to dryness to produce an amarone.

Two other regions in Veneto are also fairly well known internationally. These are Breganze, 50 km northeast of Verona, and Conegliano, 50 km north of Venice. Although Breganze produces both red and white wines, it is most famous for a sweet white wine made from the local cultivar Vespaiolo. The grapes are processed similarly to those used to produce red recioto wines. In Conegliano, another local white cultivar, Prosecco, is used to produce still, frizzante, and spumante wines. The frizzante and spumante wines may contain some Pinot bianco and Pinot grigio. In addition to regional cultivars, Conegliano also cultivates several widely grown Italian and French varieties.

Although fine wines are produced in Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Lombardy, provinces to the east and west of Veneto, respectively, Piedmont in the northwest is the most internationally recognized region. The largest and best-known of Piedmontese wine areas are centered around Asti (44°54′N), in the Monferrato Hills. This subalpine region receives abundant rainfall, with moderate precipitation peaks in the spring and autumn. The latter is often associated with foggy autumn days at lower altitudes. The area is famous for full-bodied reds, sweet spumante, and bittersweet vermouths. As a whole, Piedmont possesses a vineyard area of about 60,000 ha (mostly on hillsides) and yields almost 4 million hL wine/year.

The most renowned red wines of the region come from the Nebbiolo grape, grown north and south of Alba (44°41′N). They are especially associated with the villages of Barbaresco and Barolo. In both appellation regions, the best sites are located on higher portions of either east- or south-facing slopes. Those associated with Barolo are generally at a higher altitude, and less likely to be fog-covered in the fall than the slopes around Barbaresco. Nebbiolo is grown in other areas of the Piedmont, notably the northwest corner, and in northern Lombardy. In both areas, regional names such as Spanna and Chiavennasca predominate. Many Nebbiolo wines are named after the town from which they come, without mention of the cultivar.

Lombardy’s Nebbiolo region (Valtellina) occurs on steep, south-facing slopes lining the Adda River, where it leaves the Alps and flows westward into Lake Como. The vineyards along this 50-km strip often occur on 1–2 m wide, constructed terraces. Owing to the strong westerly winds, the canes of the vines are often intertwined. In addition, the vines are trained low to gain extra warmth from the soil and garner protection from winter storms. Recioto-like wines are occasionally produced in Valtellina, where they are called Sfursat or Sforzato.

Most Piedmontese wines are produced from indigenous grape varieties. Most are red, such as Barbera (about 50% of all production), Dolcetto, Bonarda, Grignolino, and Freisa. Some white wines are produced, primarily from cultivars such as Moscato bianco, Cortese, Chardonnay, and Arneis. Moscato bianco is used primarily in the production of the sweet, aromatic, sparkling wine, Asti Spumante. Cortese is commonly used to produce a dry still white wine in southern Piedmont, but it is also employed in the production of some frizzante and spumante wines.

Pure varietal wines, rather than blends, are the standard in Piedmont. Modern fermentation techniques are common. However, for some wines – notably those from Nebbiolo – aging in large oak casks for several years is still common. Extensive experimentation with barrel aging is in progress. Carbonic maceration is used to a limited extent to produce vino novello wines, similar to those of beaujolais nouveau.

Piedmont is also the center of vermouth production in Italy. The fortified herb-flavored aperitif was initially produced from locally grown Moscato bianco grapes. However, most Moscato grapes are now used in the production of Asti Spumante. The majority of the wine used in producing vermouth currently comes from further south.

Central Italy

Although wine is produced in all Italian provinces, chianti is the wine most commonly associated with Italy in the minds of many wine consumers. Chianti is Tuscany’s (and Italy’s) largest appellation. It includes seven separate subregions that constitute about 70% of the 83,000 ha of Tuscan vines. These cover a 180 km-wide area in central Tuscany. The most famous section, Chianti Classico, incorporates the central hilly region between Florence and Siena (~43°30′N). Vineyards grow mostly Sangiovese. Sangiovese makes up between 75 and 90% of the blend. Canaiolo and Colorino are the two other red varieties. Wine from two white cultivars (Trebbiano and Malvasia) may also be employed. Addition of must from white cultivars improves color development by supplying missing phenolic compounds involved in copigmentation.

The total region encompassed by Chianti includes a wide range of soils, from clay to gravel, although most of the region is calcareous. Slopes in this predominantly hilly zone vary considerably in aspect and inclination, with altitudes extending mostly from 200 to 500 m. These geographic differences, combined with the flexibility in varietal content, and occurrence of many clones, confer on chianti the potential for as much variation in character as bordeaux. There is a tendency to increase vine density (from the standard 2000–2500 vines per hectare to some 5000 vines per hectare) and to shift from the outdated Guyot system to spur-pruned cordons.

Although most versions of chianti are made using standard vinification techniques, several winemakers are returning to the ancient governo process (see Chapter 9). It is particularly advantageous when making light, early-drinking wines (Bucelli, 1991) – the features that initially made Chianti famous. A similar technique is also used by several producers in Verona.

In addition to chianti, several other Tuscan red wines are made from the Sangiovese grape. These wines may involve the use of non-Italian grape varieties, such as the inclusion of Cabernet Sauvignon in Carmignano, or the production of a pure Sangiovese wine, such as Brunello di Montalcino. Although Sangiovese is the most common name for the variety, vernacular names such as Brunello and Prugnolo may also be employed. Superior clones, such as Sangioveto, have also been individually named.

On the eastern side of central Italy are several wine producing regions. The most well known, due to its expensive exports of Lambrusco wine, is Emilia-Romagna. Although shunned by critics, the bubbly, semi-sweet, cherry-fruit-like fragrance of this red wine is highly appreciated by millions of consumers. A well-made wine, without fault, that sells widely should be considered a success. Not everyone wants, or can afford, to drink a liquid art object.

In addition to Lambrusco, the regions of Emilia-Romagna, Marche and Abruzzi possess a wide range of indigenous cultivars. Their potential is largely unknown. Until vintners with sufficient capital seriously study their potential, they will continue to languish in possibly undeserved ignominy. All one has to think of are the difficulties producers still have with Pinot noir. How would it have faired had it occurred in the backwaters of some landlocked valley in Italy, rather than under the hands of rich monasteries in Burgundy?

Southern Italy

Southern Italy produces most of the country’s wine, much of it going into inexpensive Euroblends or distilled into industrial alcohol. The application of contemporary viticultural and enologic practices is gradually increasing the production of better wines, bottled and sold under their own name. Examples of local cultivars producing fine red wines are Aglianico in Basilicata and Campania, Gaglioppo in Calabria, Negro Amaro, Malvasia nera and Primitivo in Apulia, Cannonau in Sardinia, and Nerello Mascalese in Sicily. Several indigenous cultivars, such as Greco, Fiano, and Torbato, also generate interesting dry white wines. It is far better that these regions concentrate on the qualities of local cultivars than produce another variation-on-a-theme of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, or Chardonnay.

Reflecting the hot dry summers in southern Italy, sweet and fortified wines have long been the best wines of the region. These can vary from dessert wines made from Malvasia, Moscato, and Aleatico, to sherry-like wines from Vernaccia di Oristano, to marsala produced in Sicily.

Spain

Along with Portugal, Spain forms the most westerly of the three major Mediterranean peninsulas, the Iberian Peninsula. It is the largest and consists primarily of a mountain-ribbed plateau averaging 670 m in altitude. The altitude and the mountain ranges along the northern and northwestern edges produce a long rain shadow over most of the plateau (Meseta). With its Mediterranean climate, most of Spain experiences hot, arid to semiarid conditions throughout the summer.

Climatic conditions have markedly influenced Spanish viticultural practice. Because of a shortage of irrigation water, most vines are trained with several low trunks or arms (≤50 cm), each pruned to two short spurs. Where irrigation is feasible, recent experimentation has shown that yield can be increased while maintaining grape quality (Esteban et al., 1999). The short, unstaked bushy vines may limit water demand and shade the immediate soil, where most surface roots are located. Vine density is kept as low as 1200 vines/ha in the driest areas of the Meseta (La Mancha) to ensure sufficient moisture during the long hot summers. Daytime maxima of 40 to 44 °C are not uncommon. In areas with more adequate and uniform precipitation, such as Rioja, planting densities average between 3000 and 3600 vines/ha. In most of Europe, planting densities of 5000 to 10,000 vines/ha may occur. Thus, although Spain possesses more vineyard area than any other country (~1.2 million ha), it ranks third in wine production (~43 million hL/year). Its yield per hectare is about one-third that of France, currently averaging about 36 hL/ha.

In the northern two-thirds of Spain, table wines are the primary vinous product, whereas in the southern third (south of La Mancha), fortified sweet or sherry-like wines are produced. In the past, wine production in most regions was unpretentious. Although the wines were acceptable as an inexpensive local beverage, they had little broad appeal, except for use in blending. They often supplied the deep color and alcohol lacking in many French wines, a practice now banned except for Euroblend wines. Reminders of ancient practices are evident in the continuing but diminishing use of tinajas. These large-volume, amphora-like, ceramic fermentors are occasionally employed in southern Spain (Valdepeñas and Montilla-Moriles). The Penedés region, south of Barcelona, is a major center for enologic and viticultural innovation. Nevertheless, traditional centers of wine excellence, such as Rioja in the north, and the Sherry region in the south, are involved in considerable experimentation and modernization. Modern trends also affect grape and wine production in the major producing areas of central Spain, and have begun to provide wines that can compete internationally under their own appellations.

Although the reputation of fine Spanish wines is based largely on indigenous cultivars, such as Tempranillo, Viura, and Palomino, most wines are produced from the varieties Airen and Garnacha. So widely are these grown that they were, and may still be, the two most extensively cultivated varieties in the world.

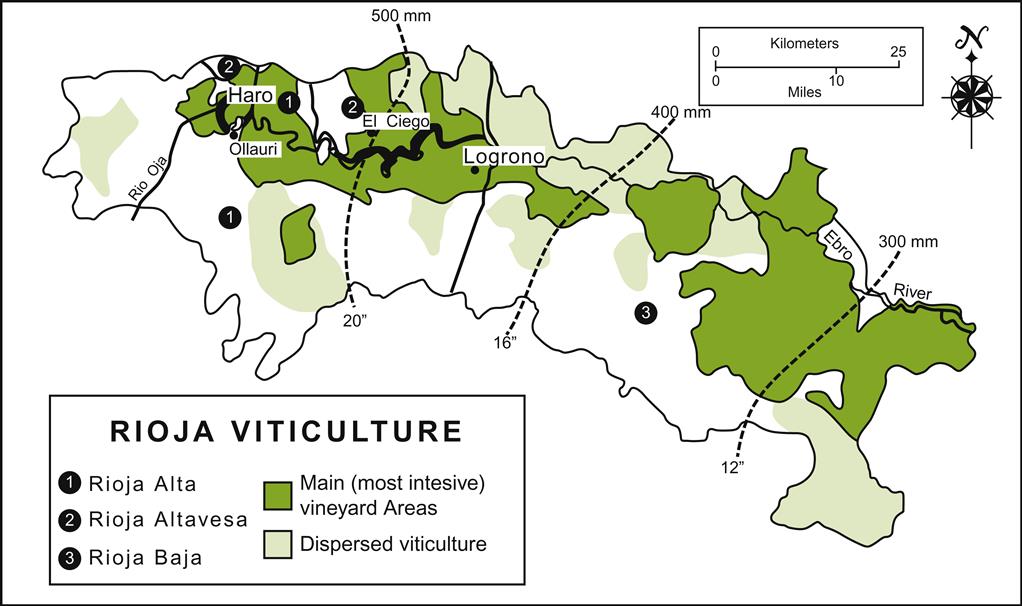

Rioja

Rioja has a long tradition of producing the most highly regarded table wines in Spain. The region spans a broad 120-km section of the Ebro River valley and its tributaries, from northwest of Haro (42°35′N) to east of Alfaro (42°08′N). The upper (western) Alta and Alavesa regions are predominantly hilly and possess vineyards mostly on slopes rising nearly 300 m above the valley floor. The altitude of the valley floor drops steadily eastward, from 480 m in the west to about 300 m at Alfaro. The lower (eastern) Baja region generally possesses a rolling landscape with many vineyards on level expanses of valley floor.

The south-facing slopes of the northern Sierra Cantábrica possess a primarily stony, calcareous, clayey soil, whereas the south side of the valley and the north-facing slopes of the southern Sierra de la Demanda possess a calcareous subsoil, overlaid by stony ferruginous clay or alluvial silt. The parallel sets of mountain ridges that run east and west along the valley help shelter the region from the cold north winds and hot blasts off the Meseta to the south.