Specific and Distinctive Wine Styles

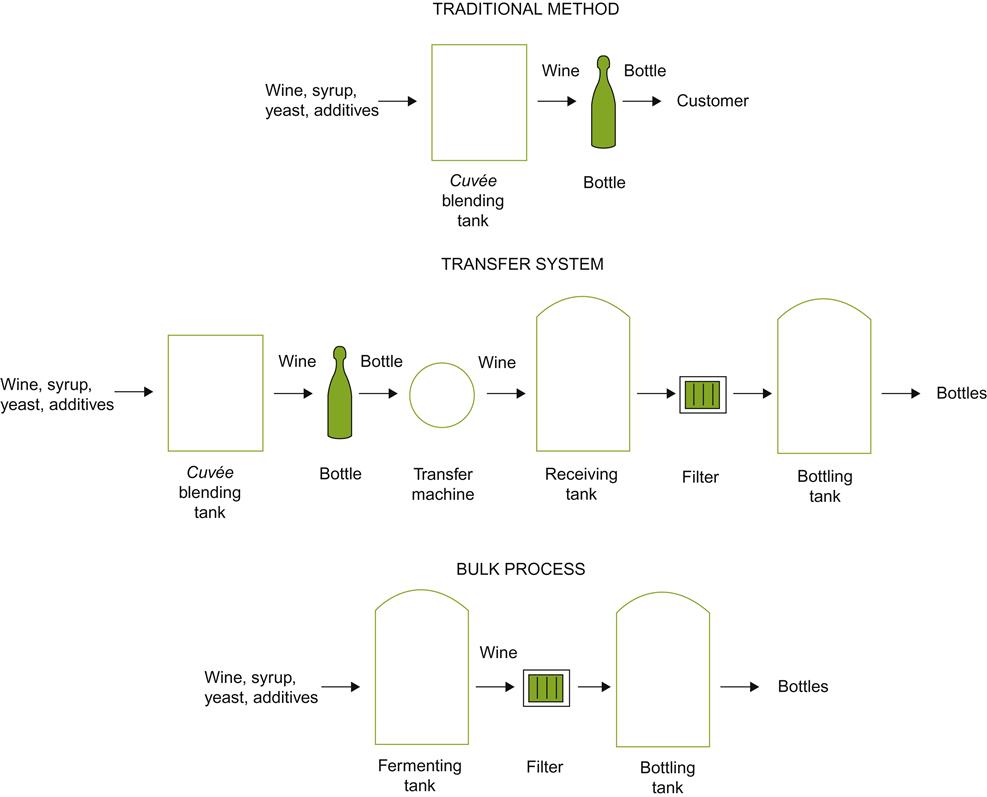

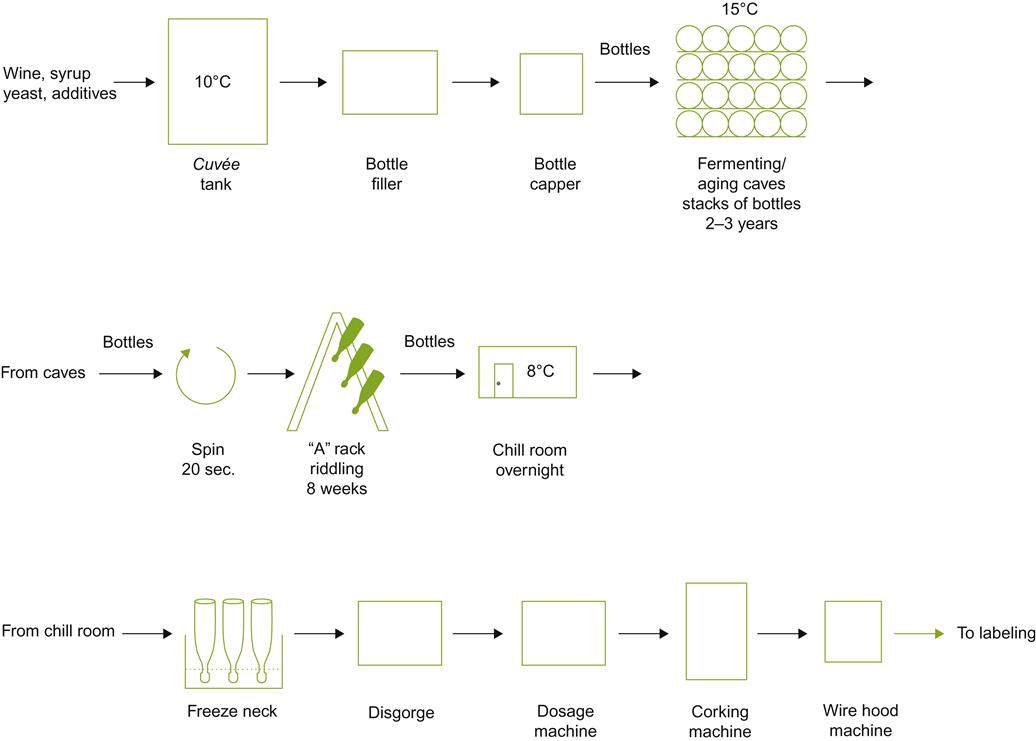

Although wine has been made for millennia, most current styles are of comparative recent origin, some having no ancient equivalent. Sweet wines were produced in the past, but largely by techniques little used today. Modern versions include those based on juice concentrated biologically (botrytized wines) or by physical processes (freezing, desiccation, or heating), or sweetened by the addition of a süssreserve. Unique red table wines examined include those involving drying (appassimento and occasionally botrytized), refermentation (governo), and carbonic maceration (e.g., Beaujolais). Production of the various types of sparkling wines is reviewed, principally those employing the traditional (méthode champagnoise) process. Also discussed is an account of the physico-chemistry of effervescence and mousse development. Subsequently, details of the production and attributes of the major stylistic forms of fortified wines are provided, notably sherries, ports, madeiras, and vermouths. This is followed by an exploration of the types, production, and characteristics of brandies.

Keywords

Sweet wines; botrytized wines; icewines; vin santo; appassimento; amarone; governo process; carbonic maceration; champagnes; effervescence; fortified wines; sherry; port; madeira; vermouth; brandies

Wine has been produced for millennia, but many modern styles have no ancient equivalent. Wine styles often reflect the unique climatic and politico-socio-economic environment under which they arose. For example, botrytized wines emerged in regions favoring the selective development of noble-rot; sparkling wine evolved under atypically cold conditions unsuitable for standard red wine production in Champagne; and port arose out of expanded trade between Portugal and England, due to conflicts and trade restrictions with France. Some of these wine styles, such as those noted, have spread throughout the world. Others have remained local specialties, if not idiosyncrasies. This chapter covers some of the more important, interesting, and unique wine styles, and their main variants.

Sweet Table Wines

Sweet table wines encompass a wide diversity of styles, possessing little in common other than sweetness. They may be white, rosé, or red; still or sparkling; and may range from aromatically simple to complexly fragrant. The most famous are those made from noble-rotted (Botrytis-infected) grapes.

Botrytized Wines

Wines made from grapes partially infected by Botrytis cinerea have probably been made for centuries. The fungus is ubiquitous. Normally, it induces a destructive bunch rot (see Chapter 4). If significant numbers of infected grapes are included in the crush, the wine made from them is unpalatable. The wine has a brownish color, shows high volatile acidity, is difficult to clarify, and possesses multiple, unpleasant, moldy odors. Nevertheless, under very specific, unique, climatic conditions, infection is restricted, generating what is termed ‘noble’ rot. These grapes beget some of the most seraphic white wines that have ever been produced. This is despite my having studied Botrytis much of my life.

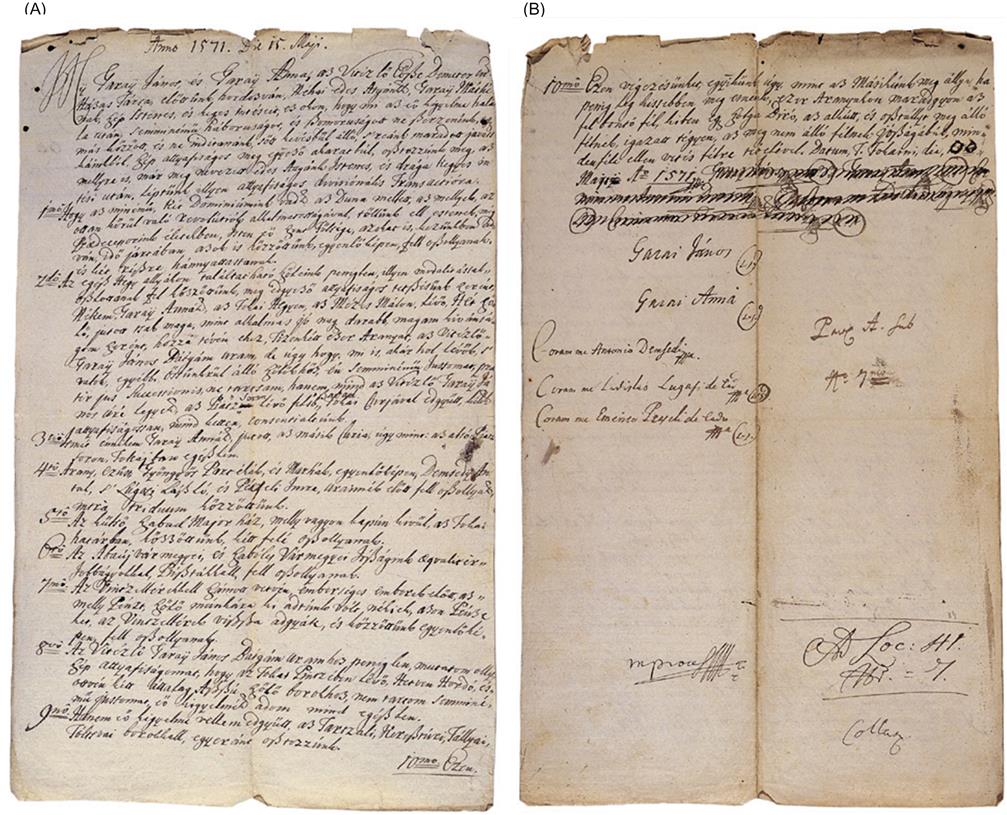

When noble-rotted grapes were first intentionally used for wine production is unknown. Historical evidence favors the Tokaj region of Hungary, in the mid-sixteenth century (ca. 1560). There is documentary evidence that wine, made specifically from botrytized (aszú) grapes, was of sufficient worth to be mentioned by name in a will, dated 1571 (Fig. 9.1). The commercial renown of this special Tokaji wine was already well established by the early 1600 s (Zimányi, 1987). Documentary evidence, denoting the production of botrytized wine at Schloss Johannisberg, Germany in 1775, and possibly earlier elsewhere, is alluded to in Johnson (1989). When the deliberate production of botrytized wines began in France is uncertain, but production appears to have been well established in Sauternes between 1830 and 1850. Isolated production of botrytized wines occurs throughout Europe, wherever conditions are favorable for noble rot development. The idea of using Botrytis-infected grapes for wine production has been slow to catch on in the New World, but botrytized wines are now produced to a limited degree in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States.

Infection

Early in the season, most infections develop from spores produced on overwintered fungal tissue, either in tissue remains or resting structures called sclerotia (Fig. 4.55). Infections begin on aborted and senescing flower parts, notably the stamens and petals. Infected flower parts, entrapped within the developing fruit cluster, may initiate infection later on in the season. Although early fruit infections usually cease as the hyphae penetrate the young berry, the hyphal cells remains viable. Reactivation of these latent infections is particularly important under dry autumnal conditions. As the fruit reaches maturity, resistance to fungal growth declines. This most likely involves the reduction in acidity, as the grapes ripen, and a decline in antifungal phenolic content. Under moist conditions, though, new infections are thought to be more important than latent infections.

Disease susceptibility, and its direction (bunch vs. noble rot), depend on several factors. Skin toughness and open fruit clusters reduce disease incidence, whereas rain, protracted moist periods, and shallow rooting increase susceptibility. The latter encourages rapid water uptake and berry splitting, both favoring bunch-rot development. In contrast, noble rot develops late in the season, under a protracted sequence of fluctuation moist/dry conditions. This typically involves cool, still nights, in vineyards adjacent to warm water. Fog development during the evening and/or early morning favors fungal growth. If this is sequentially followed by dry, sunny days, berries begin to dehydrate, slowing and severely restricting fungal growth. Repeated cycles of activation/repression result in the progressive concentration as well as modification of berry content.

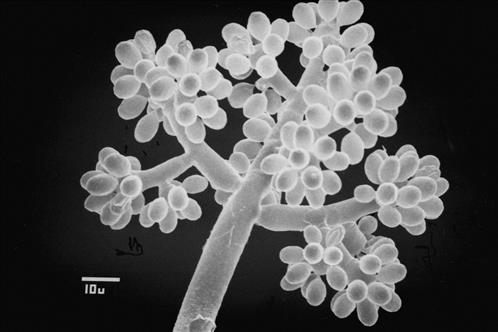

Depending on the temperature and humidity, spores (conidia) are produced on specialized, branched hyphae (conidiophores) that erupt through the berry skin. The shape of the spore clusters (Fig. 9.2) so resembles grape clusters that the botanical name for the fungus is derived from the Greek word meaning ‘grape cluster’ – βοτσυς. Because the microclimate of the fruit cluster markedly affects fungal development, various stages of healthy, noble-, and bunch-rotted grapes may frequently occur within the same cluster (Plate 9.1).

During infection, several hydrolytic enzymes are released by Botrytis. Particularly destructive are the pectolytic enzymes. They degrade the components that hold plant cells together. The enzymes also incite disruption, resulting in the collapse and death of adjacent tissue. With loss of physiological control, the fruit can easily begin to dehydrate under dry conditions. Disruption of the vascular connections between the pedicel and the fruit, as ripening advances, means that moisture lost via evaporation is not replaced from the vine. Additional water may be lost by evaporation through conidiophores, which can act as wicks.

The resultant dehydration is a crucial factor in determining disease development. Drying retards fungal growth and appears to modify its metabolism. This may result from the combined influences of the increasing osmolarity and acidity of the juice. Juice concentration is also a feature crucial in the development of the wine’s sensory properties. Finally, water loss limits secondary invasion by saprophytic bacteria and fungi. Invasion by fungi, including Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Mucor, probably generates most of the moldy off-odors and tastes associated with bunch rot. For example, P. frequentans produces plastic and moldy off-odors, via the synthesis of styrene (Jouret et al., 1972) and 1-octen-3-ol (Kaminiski et al., 1974), respectively. Saprophytic fungi are commonly present during the development of Botrytis bunch rot, but almost completely absent during noble-rotting. In addition, the phenolic flavors, commonly associated with wines made from botrytized red grapes, is undetectable in botrytized white wines. This may result from pressing being conducted without prior crushing, and the lower phenolic content of white grapes. Despite this, noble rot is associated with a color change in the grape skins. White grapes take on a pink to purplish coloration (Plate 9.1). This presumably results from pigment formation as leucoanthocyanins (flavan-3,4-ols) oxidize.

One of the typical chemical indicators of Botrytis infection is the presence of gluconic acid. Although B. cinerea produces gluconic acid, the acetic acid bacterium, Gluconobacter oxydans, is even more active in this regard. Because they frequently invade grapes infected by Botrytis, they are probably responsible for most of the gluconic acid found in diseased grapes (Sponholz and Dittrich, 1985). The bacteria also produce acetic acid and ethyl acetate. Thus, their action may be partially responsible for the elevated concentrations of these compounds in some botrytized wines. The elevated sugar content of the juice is also known to accentuate the production of volatile acidity and ethyl acetate. Inoculation with Torulaspora delbrueckii has been suggested to reduce the likelihood of this potential fault in botrytized wines (Renault et al., 2009).

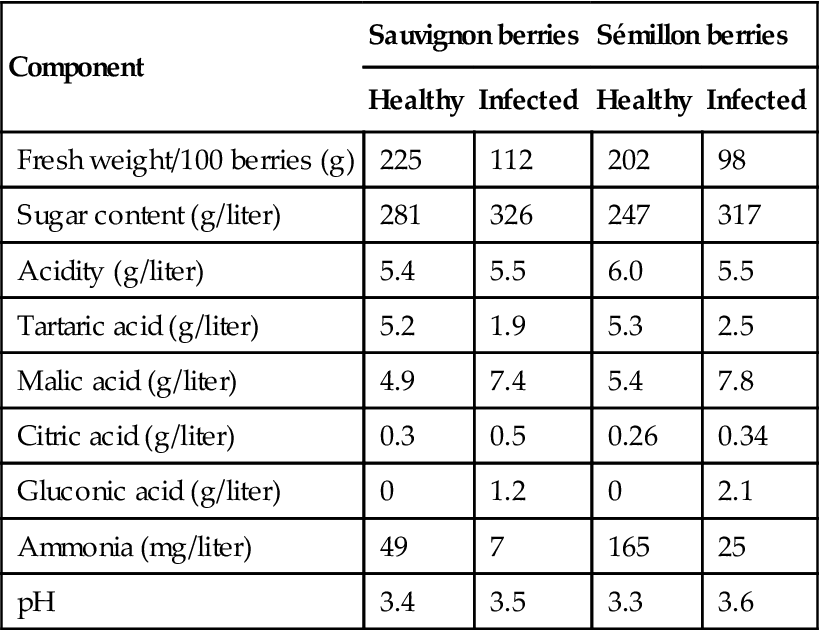

Chemical Changes Induced in Association with Noble Rotting

Berry dehydration, combined with the metabolic action of Botrytis, are the principal causes of the sensorial influences of noble rotting. Some of the effects of drying simply have concentrating effects, such as the increase in the citric acid content (Table 9.1). With other compounds, fungal metabolism is sufficiently active to result in a decrease, despite the concentrating effect of water loss. This is particularly noticeable with tartaric acid and ammonia (Table 9.1). The selective metabolism of tartaric acid, versus malic acid, is crucial in avoiding a marked decline in pH. In addition, the enhanced acidity, associated with the relative increase in malic acid content, counteracts the cloying effect of the wine’s high, residual sugar content.

Table 9.1

Comparison of juice from healthy and Botrytis-infected grapes

| Component | Sauvignon berries | Sémillon berries | ||

| Healthy | Infected | Healthy | Infected | |

| Fresh weight/100 berries (g) | 225 | 112 | 202 | 98 |

| Sugar content (g/liter) | 281 | 326 | 247 | 317 |

| Acidity (g/liter) | 5.4 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 5.5 |

| Tartaric acid (g/liter) | 5.2 | 1.9 | 5.3 | 2.5 |

| Malic acid (g/liter) | 4.9 | 7.4 | 5.4 | 7.8 |

| Citric acid (g/liter) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.26 | 0.34 |

| Gluconic acid (g/liter) | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 2.1 |

| Ammonia (mg/liter) | 49 | 7 | 165 | 25 |

| pH | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

Source: After Charpentié (1954) from Ribéreau-Gayon et al., 1980, reproduced by permission.

One of the most notable changes during noble rotting is the increase in sugar content. This occurs in spite of the metabolism of up to 35–45% of the original grape sugars. With Brix levels reaching up to 60 or above, there is a corresponding decline in osmotic potential. This may explain the inability of B. cinerea to metabolize a higher proportion of sugars, and other metabolic disturbances during infection (Sudraud, 1981). Occasionally, selective glucose metabolism is reflected in an atypically high fructose/glucose ratio. The breakdown of pectins and grape polysaccharides also results in the accumulation of sugars, such as arabinose, galactose, mannose, rhamnose, xylose, and the sugar acid, galacturonic acid.

Production of glycerol during infection and fermentation, combined with the concentrating effect of berry dehydration, can result in values reaching or exceeding 30 g/L. At such levels, it could augment the smooth mouth-feel of the wine. This potential may be enhanced by the simultaneous synthesis and concentration of other polyols, such as arabitol, erythritol, myo-inositol, sorbitol, xylitol, and, in particular, mannitol (Magyar, 2011).

A distinctive feature of noble rotting is a general loss in varietal aroma. This is particularly noticeable with Muscat cultivars. Aroma impairment is explained largely by the degradation of terpenes that give these varieties their distinctive fragrance. Examples are the metabolism of linalool, geraniol, and nerol to less volatile compounds, such as β-pinene, α-terpineol, and various furan and pyran oxides (Bock et al., 1986, 1988). These may be involved in the phenolic and iodine-like odors reported in some botrytized wines (Boidron, 1978). Botrytis also produces esterases that can degrade fruit esters, that give many young white wines their fruity character (Dubourdieu et al., 1983). The significance of these effects depends on their relative importance to wine fragrance. Muscat varieties often lose more character than they gain from Botrytis, whereas Riesling and Sémillon generally gain more aromatic complexity than they lose in varietal distinctiveness. Another potential flavorant, seemingly destroyed by B. cinerea, is 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene (TDN) (Sponholz and Hühn, 1996). At subthreshold levels, it contributes to an aged bouquet, but above about 20 μg/L, it can donate a kerosene-like odor.

An exception to the typical loss of varietal character applies to some thiols, notably those generated in cultivars such as Sauvignon blanc. In this instance, the concentrations of S-3-(hexanol-1-ol)-L-cysteine (Cys-3MH) in grapes, and 3-mercaptohexanol (3MH) in wines, increases in association with botrytization (Thibon et al., 2009). Additional thiols, derived from precursors formed during infection, are liberated as a consequence of fermentation (Thibon et al., 2010). Some of those present in young sauternes, possessing roasted or citrus resemblances, are undetectable after several years (Bailly et al., 2009).

In addition to the frequent reduction in varietal distinctiveness, Botrytis provides its own special attributes. One of the more significant flavorants appears to be sotolon. In combination with other aromatics, found or produced in botrytized wines, sotolon was considered to contribute to the honey-like fragrance of many botrytized wines (Masuda et al., 1984). Nonetheless, no correlation between the degree of botrytization and sotolon content has been detected (Sponholz and Hühn, 1993). Infected grapes also contain the mushroom alcohol, 1-octen-3-ol. Its relevance to the fragrance of botrytized wines appears in doubt, though, as it can be converted by Saccharomyces cerevisiae to a less aromatic ketone, 1-octen-3-one (Darriet et al., 2002). Among additional compounds found are terpene derivatives. More than 20 terpenes have been isolated from infected grapes (Bock et al., 1985). Additional compounds, typical of botrytized sauternes, have been identified by Sarrazin et al. (2007). Some of these include homofuraneol, theaspirane, γ-decalactone and abhexon (Bailly et al., 2009). During aging theaspirane accumulates. It appears to be associated with an apricot odor, a characteristic attribute of botrytized wines.

Infection by Botrytis cinerea not only affects the wine’s taste and fragrance, but it also restricts harvesting options. By disrupting skin integrity, rupture is facilitated. Correspondingly, harvesting is done manually. Surprisingly, infection retards separation of the berry from the pedicel (Fregoni et al., 1986).

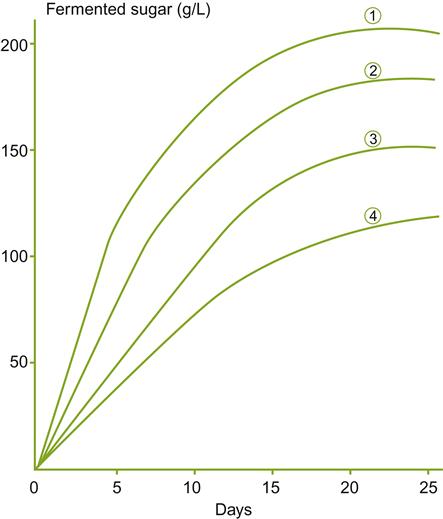

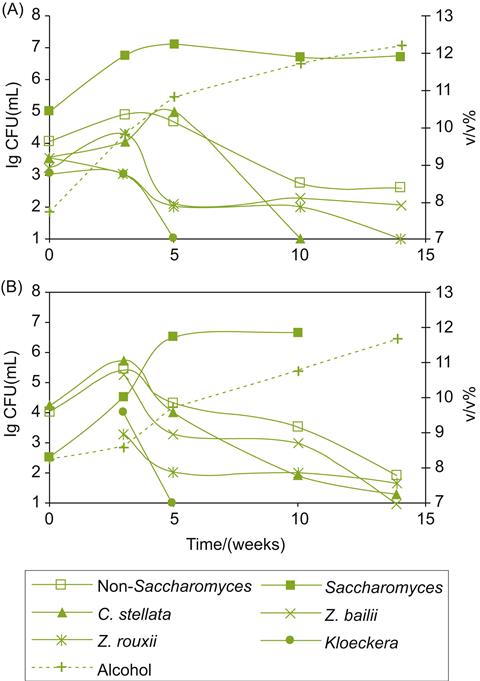

Infection by Botrytis affects the activity of other microorganisms on and in grapes and juice before, during (Fig. 9.3), and after fermentation. In the vineyard, infection facilitates secondary invasion by acetic acid bacteria and several saprophytic fungi. Infection also affects the epiphytic yeast flora, both increasing their numbers and modifying species composition. For example, Candida stellata, Torulaspora delbrueckii, and Saccharomyces bayanus may dominate the yeast flora of infected grapes. In tokaji, Candida pulcherrima may be the dominant yeast on botrytized grapes. This shifts to C. stellata after collection, transport to, and storage at the winery (Bene and Magyar, 2004; Fig. 9.4). The dependence of T. delbrueckii on oxygen may partially explain its early demise during fermentation (Mauricio et al., 1991), whereas the high population of Candida is probably associated fructose metabolism (Mills et al., 2002). In addition, molecular techniques have detected the presence of viable, but nonculturable, populations of Candida and Hanseniaspora at the end of fermentation (Mills et al., 2002). Saccharomyces uvarum appears to be particularly able to withstand the high sugar concentration, and low nitrogen, sterol and thiamine conditions, as well as the cool temperatures typically associated with botrytized wine fermentation.

Because Botrytis cinerea significantly lowers juice thiamine content, small amounts of the vitamin (0.5 mg/L) are frequently added before fermentation (Dittrich et al., 1975; Dubourdieu, 1999). This limits the decrease in keto-acid decarboxylation, associated with low thiamine levels, and the undesirable, marked increase in SO2-binding carbonyl compounds.

There is considerable variation in the influence of different strains of Botrytis cinerea on yeast growth. Suppression may result from the release of toxic fatty acids by fungal esterases. In addition, some Botrytis strains produce compounds that can either stimulate (Minárik et al., 1986) or suppress (Dubourdieu, 1981) yeast metabolism.

Little is known about the specific effects of noble rotting on malolactic fermentation. The presence of high residual sugar and glycerol contents presumably could favor its development. However, the addition of up to 200 or 250 mg/L SO2, to retain a noticeable residual sugar content free from undesirable microbial activity during maturation and after bottling, precludes malolactic fermentation. Although the addition of sulfur dioxide rapidly reduces the culturable yeast population, a variable portion enters a viable, but nonculturable state (Divol and Lonvaud-Funel, 2005). Depending on conditions, these cells may reinitiate growth, causing spoilage.

Laccases are one of the most significant enzymes produced by B. cinerea. Their pathologic function is uncertain, but it is suspected that they inactivate antifungal grape phenolics, such as pterostilbene and resveratrol (Pezet et al., 1991). Different laccases are induced in grape juice, and in the presence of gallic and p-coumaric acids. In addition, pectin may augment laccase synthesis in the presence of phenolic compounds (Marbach et al., 1985). In wine, laccases oxidize a wide range of phenolics, including p-, o-, and some m-diphenols, diquinones, anthocyanins, tannins, and a few other compounds, such as ascorbic acid. This may partially explain the comparatively high phenolic content of botrytized wines, and the atypical absence of hydroxycinnamates. In addition, the oxidation of 2-S-glutathionylcaftaric acid may contribute to much of the golden coloration of botrytized white wine (see Macheix et al., 1991).

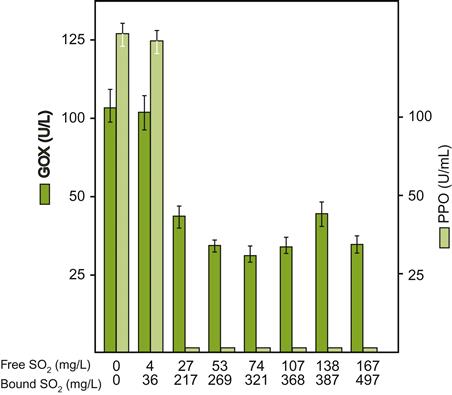

Unlike grape polyphenol oxidase, laccase is particularly active at wine pH values, as well as in the presence of typical levels of sulfur dioxide used in other wines. Concentrations of about 50 mg/L SO2 at pH 3.4 are required to inhibit the action of laccase in wine (about 125 mg/L added to the must) (Kovać, 1979). Another difference between grape and fungal phenol oxidases is the minimal effect their oxidized by-products have on laccase activity (Dubernet, 1974). In contrast, hydrogen sulfide can completely inhibit laccase activity at contents as low as 1–2.5 mg/L (added as a sulfide salt) (see Macheix et al., 1991).

The activity and stability of laccase in must and wine have serious consequences for red wines. Because laccase rapidly and irreversibly oxidizes anthocyanins, even low levels of infection can result in considerable browning and loss of red coloration. In contrast, the gold color produced from oxidized phenolics in white grapes is considered a positive quality feature. Color shifts depend largely on the grape variety, as well as the degree and nature of infection.

In addition to laccase, B. cinerea synthesizes other oxidases, for example, glucose, amine and glycerol oxidases, catalase, and peroxidase. Of these, only glucose oxidase is of significance in must or wine, due to its stability, activity at low pH values, and relative insensitivity to sulfur dioxide (Fig. 9.5). These properties make it likely that it is one of the most significant oxidases in botrytized grapes and juice (Vivas et al., 2010). By oxidizing glucose to gluconic acid, it releases hydrogen peroxide. It subsequently oxidizes other compounds, for example, tartaric acid, ethanol, and glycerol, respectively to glyoxylic acid, acetaldehyde, and glyceraldehyde. These, in their turn, can interact with catechins and proanthocyanins, generating yellowish pigments.

During infection, Botrytis synthesizes a series of high-molecular-weight polysaccharides. These form two distinct subgroups. One group consists primarily of polymers of mannose and galactose, with small amounts glucose and rhamnose. They vary in mass between 20,000 and 50,000 Da, and induce increased production of acetic acid and glycerol during fermentation (Dubourdieu, 1981). The other group consists of branched, β-1,6 glucan chains. These polymers can range from 100,000 to 1,000,000 Da. They have little, if any, effect on yeast metabolism, but form strand-like lineocolloids in the presence of alcohol. As little as 2–3 mg/L can seriously retard filtration (Wucherpfennig, 1985). Consequently, they can cause serious plugging problems during clarification. If assessed to be a problem, they can be degraded by the addition of β-glucanases. To minimize their release, botrytized grapes are usually harvested manually and pressed whole. This is effective because of their localization just underneath the skin, in association with the fungal cells that produce them.

Botrytis may also induce a form of calcium salt instability. The fungus produces an enzyme that oxidizes galacturonic acid (a breakdown product of pectin) to mucic (galactaric) acid. Mucic acid slowly binds with calcium, forming an insoluble salt. This may produce the sediment that occasionally forms in bottles of botrytized wines.

In addition to the direct and indirect effects of Botrytis infection, changes result from the action of secondary invaders – notably the synthesis of gluconic acid by acetic acid bacteria. Often used as an indicator of Botrytis infection, gluconic acid has no known sensory significance. The sweetness of its intramolecular cyclic esters (γ- and δ-gluconolactone) is apparently too slight to be perceptible. However, these lactones, combined with two other bacterial by-products, notably 5-oxofructone and dihydroxyacetone, constitute the principal SO2-binding compounds in botrytized must and wine (Barbe et al., 2002). High concentrations of hydroxypropanedial (a triose reductone) may even further reduce free sulfur dioxide concentrations and, thereby, its antioxidative and antimicrobial effects. It is also another chemical indicator of Botrytis (and other fungal) infections (Guillou et al., 1997).

As typical of fine wines, they cannot be produced inexpensively. Dehydration results in a marked loss in juice volume; there are considerable risks in leaving grapes on the vine to overmature; and fermentation and clarification can be difficult. Nevertheless, their production is one of the crowning achievements of winemaking.

Types of Botrytized Wines

As with any style, having had independent origins in different locations and times, there is considerable variation in the cultivars used, viticultural techniques practiced, and production procedures employed. Thus, it should not be surprising that botrytized wines can be remarkably diverse. Nonetheless, there is still a noticeable similarity, imposed by the action of Botrytis cinerea, and the effects of juice concentration. They are all characterized by high residual sugar, acid, and glycerol content, and the presence of a distinctive fragrance. This is typically characterized as resembling apricot, peach, pear, and honey. Despite residual sugar contents often being above 200 g/L, the acid content is usually adequate to avoid the wine being either cloying or syrupy.

Tokaji Aszú

Documentary evidence strongly supports tokaji having been the first, intentionally produced, botrytized wine (Fig. 9.1). The grapes are grown and the wine produced in a relatively small, semi-mountainous, region of northeastern Hungary (Tokaj Hegyalja). The traditional cultivars are Furmint (70%), and Hárslevelű (25%), although in recent times, Muscat lunel, and Zéta have been cultivated, along with the return of an ancient local cultivar, Kövérszőlő. The region is sheltered by the Zemplén hills, permitting a late harvest, associated with humidity coming from the Tisza and Bodrog rivers.

Its most famous version, tokaji eszencia, is derived from juice that spontaneously seeps out of highly botrytized (aszú) berries. These have historically been placed in small wicker tubs. About 1–1.5 liters of eszencia (juice that seeps out on its own) is obtained from 30 liters of aszú berries. After several weeks, the collected eszencia is transferred to small wooden barrels for fermentation and maturation (~10 °C). Because of the very high sugar content (occasionally more than 50%), fermentation occurs slowly, seldom reaching 5% alcohol before termination. After fermentation ceases, the bungs may be left slightly ajar. Oxygen uptake was thought to be restricted by the growth of a common cellar mold, Racodium cellare, growing on the wine’s surface (Sullivan, 1981). Despite its common development on humid cellar walls (Plate 9.2), the fungus is not known to grow on the wine’s surface. Any velum cover is more likely of yeast origin. Velum development is no longer favored, except for certain dry szamorodni styles (Atkin, 2001), to which it donates a slight sherry-like attribute. The juice used in its production comes from both healthy and aszú clusters (extracted by pressing). Fermentation employs standard white wine production techniques. After a variable period, the barrels of tokaji eszencia are bunged tight. Up to 20 years in-barrel maturation may ensue before bottling. Although occasionally bottled and sold by itself, the eszencia is more commonly used for blending with aszú style wines (Eperjesi, 2010).

Aszú style wines are made from mixing young or fermenting white wine, made from healthy grapes, with various proportions of shriveled aszú paste, or occasionally berries. The paste is produced by gently crushing the berries. The aszú proportion may come from grapes before or after the eszencia (free-run) has drained away. Legislation detailing the latter process was passed in 1655 (Asvany, 1987).

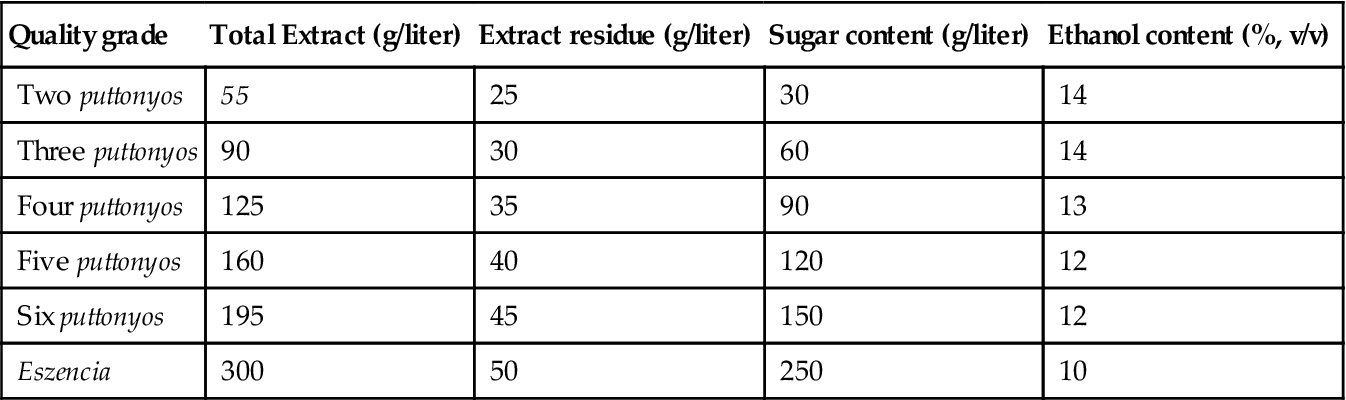

The various designations of tokaji auzú wines were originally based on the amount (number of puttony) of aszú paste added to the traditional (Gönci) barrel, before being topped up with wine made from healthy grapes. The Gönci had a capacity of 136 liters, and a puttony contained about 20–22 kg of paste. Regulations for each category are now based on minimum sugar content (60, 90, 120, and 150 g/L for 3, 4, 5 and 6 puttony aszú wines, respectively). For example, a 5 puttonyos aszú would be derived from 100 (5×20) kg aszú paste combined with about 100 kg juice or wine (Eperjesi, 2010). For continuity, the old puttonyos designations have been retained on the label. The mixture is macerated for 24–48 h, during which material is extracted from the paste. This is followed by gentle pressing and clarification by natural settling. Subsequently, the juice is transferred to small barrels (holding ~136 liters) for a continuation of, or re-fermentation. Because of cool cellar temperatures, and the presence of alcohol (if wine is used), fermentation typically proceeds slowly. Traditionally, the barrels were left partially empty, and the bung left loose for 1–3 months. This produced an oxidized attribute not found in other botrytized wines. This is attested to by the concentrations of acetaldehyde, acetals, and acetoin in the wine (see Schreier, 1979). This practice has ceased, except as noted above for certain dry szamorodni styles. The wines are only lightly sulfited. Thus, residual sulfur dioxide contents range in the level of 20 to 30 mg/L (Magyar, 2011). Fermentation may take several weeks to months to finish. Alternately, the mixture may be placed in larger cooperage. If fermentation needs to be terminated prematurely, to retain a predetermined residual sugar content, this is more commonly achieved by filtration than by sulfiting. Because of these potential variations in cellar procedures, wines from different producers often show marked individuality.

The alcohol content of the finished wine often tends to be in the 10 to 13% range. During the Communist era, a distillate made from tokaji wine was often added to prematurely terminate fermentation, to achieve an even sweeter finish, or to replace volume lost by evaporation during maturation. This may explain the alcohol contents noted for the sweeter versions listed in Table 9.2. The principal yeast involved in fermentation is Saccharomyces bayanus. Candida stellata and C. zemplinina may also be active (Sipiczki 2003).

Table 9.2

Chemical composition of Tokaji wines

| Quality grade | Total Extract (g/liter) | Extract residue (g/liter) | Sugar content (g/liter) | Ethanol content (%, v/v) |

| Two puttonyos | 55 | 25 | 30 | 14 |

| Three puttonyos | 90 | 30 | 60 | 14 |

| Four puttonyos | 125 | 35 | 90 | 13 |

| Five puttonyos | 160 | 40 | 120 | 12 |

| Six puttonyos | 195 | 45 | 150 | 12 |

| Eszencia | 300 | 50 | 250 | 10 |

Source: After Farkaš (1988), reproduced by permission.

German Botrytized Wines

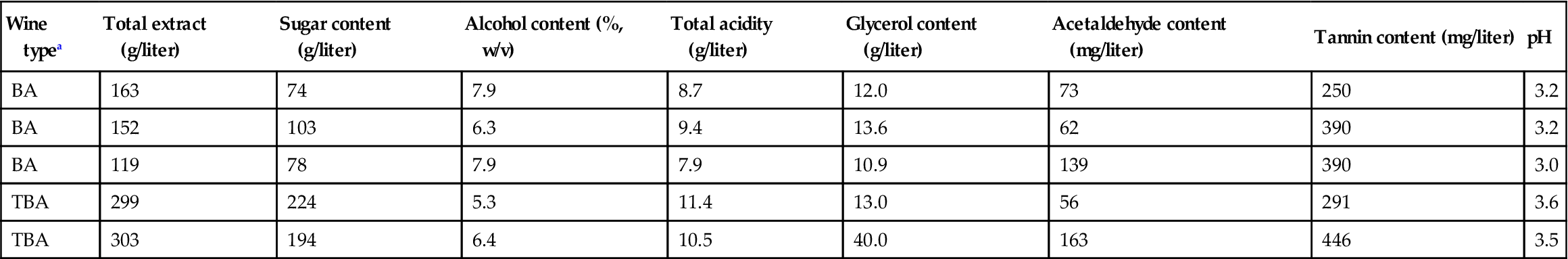

German botrytized wines come in a variety of categories. Their basic characteristics are indicated by their Prädikat designation: auslese, beerenauslese and trockenbeerenauslese. Auslesen wines are derived from specially selected clusters (or parts thereof) of late-harvested fruit. Beerenauslesen (BA) and trockenbeerenauslesen (TBA) wines are derived, respectively, from individual berries, or dried berries, selected from clusters of late-harvested fruit. Auslesen is typically botrytized, but not necessarily (Anonymous, 1979). In contrast, BA and TBA versions require Botrytis-induced concentration. Each category is also characterized by an increasingly high minimum grape sugar content (see Table 10.1). The chemical and sensory attributes of TBA wines are very similar to those of a 6 puttony tokaji aszú.

Riesling is the preferred cultivar for producing botrytized wines. Nonetheless, other cultivars are occasionally used. These may include Gewürztraminer, Ruländer, Scheurebe, Silvaner, and Huxelrebe. Similar wines are produced in Austria, but frequently from Pinot blanc, Pinot gris, Welsch Riesling, Neuburger, and other cultivars. The most renowned region for their production is Ruster, where vines are grown adjacent to Lake Neusiedl. The most propitious locations in Germany are along the Rhine and Mosel rivers, notably the Rheingau and central Mosel-Saar-Ruwer regions, respectively.

BA and TBA juices typically contain more sugar than is converted to alcohol during fermentation. The wines are consequently sweet and low in alcoholic strength, commonly 6–8% (Table 9.3). Auslesen wines may be fermented dry or may be processed to retain residual sweetness, depending on the preferences of the winemaker.

Table 9.3

Composition of some 1971 Beerenauslesen and Trockenbeerenauslesen wines

| Wine typea | Total extract (g/liter) | Sugar content (g/liter) | Alcohol content (%, w/v) | Total acidity (g/liter) | Glycerol content (g/liter) | Acetaldehyde content (mg/liter) | Tannin content (mg/liter) | pH |

| BA | 163 | 74 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 12.0 | 73 | 250 | 3.2 |

| BA | 152 | 103 | 6.3 | 9.4 | 13.6 | 62 | 390 | 3.2 |

| BA | 119 | 78 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 10.9 | 139 | 390 | 3.0 |

| TBA | 299 | 224 | 5.3 | 11.4 | 13.0 | 56 | 291 | 3.6 |

| TBA | 303 | 194 | 6.4 | 10.5 | 40.0 | 163 | 446 | 3.5 |

aBA, beerenauslese; TBA, trockenbeerenauslese.

Source: Data from Watanabe and Shimazu (1976).

The other main Prädikat wine categories, namely, Kabinett and Spätlese, may be derived from botrytized grapes, but seldom are. Their sweetness is usually derived from the addition of süssreserve – unfermented or partially fermented juice kept aside for sweetening. Süssreserve is added just before bottling to a dry wine, produced from the majority of the harvest. Various techniques have been used to restrict microbial growth in the süssreserve. These include high doses of sulfur dioxide, storage at temperatures near or below freezing, and hyperbaric CO2.

French Botrytized Wines

In France, the best-known botrytized wines are sauternes. The confluence of two rivers, the Garonne and a tributary, the Ciron, tends to generate misty conditions that favor noble rot development at harvest time. Over a period of several weeks, noble-rotted grapes may be selectively harvested from clusters in the vineyard. This technique is also used in Tokaj to maximize the collection of the largest number of aszú grapes. Because of the cost of multiple harvesting, most producers may harvest only several times, selecting the more botrytized clusters or portions for sauternes production. This is similar to the procedure followed in Germany, except that there, different styles are produced depending on the proportion of healthy grapes included and the degree of botrytization. Uninfected grapes are separately used in the production of dry white bordeaux.

When noble-rotted grapes are not individually harvested, the whole or partial clusters are pressed without stemming. This facilitates juice escape, while leaving most of the glucan polymers in the pomace. The juice may be left to soak in some of the pomace overnight, to augment flavor extraction. Because of the high viscosity of the juice, a slow, gentle, repeat, pressing is required to extract the juice. As with carbonic maceration (see below), the second and subsequent pressings tend to have the highest quality. Because of the high pressures required to extract the juice, the must or grapes may be pretreated to cryoextraction (cooling to below freezing). This ruptures cell membranes, facilitating juice release (Dubourdieu, 1999).

Typically, only one sweet style is produced for sauternes production, in contrast to the gradation of botrytized styles in Germany, Austria, and Tokaj. The hierarchical system of wine classification is based on historical prestige of the various Sauternes producer/vineyards.

A major stylistic difference between French and most German botrytized wines is the alcohol level attained. French styles commonly exceed 11–13% alcohol, whereas German versions seldom exceed 10%. Additional differences arise from whether the wines are matured in oak (up to 2 years for sauternes, or more for tokaji, but little to none in Germany), and the preferred fermentation temperatures. For example, in Sauternes, temperatures in the range of 20–24 °C are typical (Ribéreau-Gayon et al., 2006), and occasionally reach 28 °C (Donèche, 1993). In contrast, cool cellar temperatures are preferred and typical in Germany and Tokaj. The other main sensory differences come from the varieties used in their production. For example, the use of Sauvignon blanc and Sémillon explains the presence of a wide range of thiols in sauternes (Bailly et al., 2006), and their general absence in German or Hungarian botrytized wines.

Occasionally, sauternes is spoilt by yeast reactivation (Divol et al., 2006). These are strains that presumably went temporarily into a nonculturable state. They possess characteristics similar to flor yeasts, being highly resistant to sulfite, acetaldehyde, ethanol, and high concentrations of sugar. The addition of sufficient sulfur dioxide usually prevents its occurrence. The application of ethidium monoazide and quantitative PCR may permit the differentiation between viable (nonculturable) and nonliving yeasts (Shi et al., 2012).

Sweet botrytized wines are produced, in a more or less similar manner, in other French regions. The main locations are Alsace and the Loire Valley. In the Loire, Chenin blanc is the preferred cultivar, whereas in Alsace, Gewürztraminer is the principal cultivar used. It produces wines termed Sélection de Grain Nobles. Alternative cultivars used in Alsace include Riesling, Pinot gris, and Muscat.

Desirable Varietal Attributes

As noted, many grape varieties are used in the production of botrytized wines. Their appropriateness depends on several factors. Essentially all are white cultivars, thus avoiding the brown coloration produced by anthocyanin oxidation. Most varieties mature late, thus, the time of ripening coincides with weather conditions suitable for noble rot development. Late maturity also retains endogenous systems of resistance up until the early fall, reducing the likelihood of early bunch rot. The cultivars are also relatively thick-skinned. Because of the tissue softening induced by Botrytis, harvesting infected varieties with soft skins would be very difficult. Thick-skinned varieties are also less susceptible to splitting and bunch rot.

Induced Botrytization

The production of botrytized wines is both a risky and an expensive procedure. Leaving mature grapes on the vine increases the likelihood of bird damage, bunch rot, and other fruit losses. These dangers may be partially diminished by successive harvesting, but labor costs limit its use to only the most expensive estate-bottled wines. In Germany, most of the crop is usually harvested to produce a nonbotrytized wine. Only a variable portion is left on the vine for noble rot development or eiswein production.

Where climatic conditions are unfavorable for noble-rot development, harvested grapes have occasionally been exposed to conditions that favor its development (Nelson and Amerine, 1957). The fruit is sprayed with a solution of B. cinerea spores. They are subsequently placed on trays and held at about 90–100% humidity for 24–36 h at 20–25 °C. These conditions encourage spore germination and fruit penetration. Subsequently, cool dry air is passed over the fruit to induce partial dehydration and restrict fungal development. After 10–14 days, infection has developed sufficiently that the fruit can be pressed and the juice fermented. Induced botrytization has been used successfully, but only on a limited scale in California and Australia.

Inoculation of juice with spores or mycelia of B. cinerea, followed by aeration, apparently induces many of the desirable sensory changes that occur in vineyard infections (Watanabe and Shimazu, 1976). It appears not to have been used commercially. In addition, whether the artificial nature of its production might limit consumer acceptance is unknown. It does not have the ‘romance’ of the vagaries of nature.

Nonbotrytized Sweet White Wine

Sweet, nonbotrytized, white wines are produced in most, if not all wine-producing regions. Most have evolved slowly into their present-day forms. On the other hand, several modern versions have developed quickly, in response to perceived consumer preferences. Coolers are a prime example.

In most modern versions, some form of sweet reserve is used. This may even have ancient precursors. The ancient Romans occasionally placed grape clusters in cold water (e.g., a well) until late winter or early spring. The juice extracted (semper mustum) was added to sweeten dry wine.

Alternatively, sugars may be retained by prematurely terminating fermentation. This can be achieved by filtering out the yeasts; by allowing CO2 pressure to rise in reinforced fermentors; or from the addition of sulfur dioxide. In the latter, at least 50 mg/L free sulfite in required (Donèche, 1993). Because of the high concentration of SO2-binding carbonyls in juice, and that accumulate during fermentation, achieving this level of free sulfur dioxide may require the addition of sulfite at 200–300 mg/L (Divol et al., 2006). Further additions are required during aging to prevent the reinitiation of fermentation. Consequently, up to 400 mg/L total sulfur dioxide is permitted in European sweet wines. A supplementary benefit of this sulfite level is its limiting of the oxidizing action of laccase. Despite this, there is a desire to reduce the value. One possibility showing promise is the selective removal of SO2-binding carbonyls, notably acetaldehyde, pyruvic acid, 2-oxoglutaric acid, and 5-oxofructose. This has been achieved with phenylsulfonylhydrazine, attached to a porous polymer support (Blasi et al., 2008). It apparently does not cause noticeable wine quality deterioration.

Because the residual sugar content makes the wine microbially unstable, stringent measures must be taken to avoid microbial spoilage. Sterile filtration of the wine into sterile bottles, sealed with sterile corks, is common. Sterile bottling has supplanted the previous standard use of high sulfite additions at bottling.

Drying

Drying is probably the oldest and simplest procedure used in producing sweet wines. This traditionally involved placing grape clusters on mats or trays in the sun, or shade, to dehydrate. Alternatively, grapes grown in hot sunny climates were left on the vine to dehydrate. Because of the high sugar contents obtained, the wines often reached alcohol contents in the range of fortified wines, without the addition of fortifying spirits. A modern alternative, hot-air drying, can speed the process, avoiding potential browning due to sunburn, or fungal attack if drying is too slow or delayed. Drying rate largely depends on berry size and skin toughness, cuticle and wax thickness.

After several weeks or months, partially dehydrated grapes are crushed, and the concentrated juice fermented. Variations on these procedures are common throughout southern Europe, leading to a wide variety of wines, under an equally extensive proliferation of names. These may carry specific stylistic names, such as vin santo or vino tostado, or generic terms, such as recioto, passito, passiti1, appended to the name of the cultivar used, and/or its provenance. Examples are Recioto di Soave, Greco di Bianco Passito, or Passito di Pantelleria. In Friuli, sweet wine made from Picolit may be made either from grapes dried on mats or left on the vine to raisin. The latter are often affected with noble rot and, thus, possess a character combining passito and botrytized attributes. Drying grapes on mats are also used in the production of fortified sweet wines, notably Marsala, Malága, and Sherry.

Drying not only concentrates grape constituents, but also modifies grape metabolism and chemistry. Many of the changes, such as increases in abscisic acid (Costantini et al., 2006) and proline content, presumably reflect only a response to water stress. They are not known to have any sensory significance. However, activation of lipoxygenases can increase the concentration of hexanal, hex-1-enol, and hex-2-enal, whereas alcohol dehydrogenase activation promotes the synthesis of ethanol and acetaldehyde. Increased respiration and ethylene production provoke a loss in volatiles and changes in polyphenol content. An example of the latter is the synthesis of type A and type B vistins (Marquez et al., 2012). The requisite pyruvic acid and acetaldehyde for these cycloaddition pigments apparently results from the activation of anaerobic metabolism in the grapes. Additional metabolic alterations may increase the concentration of higher alcohols (Bellincontro et al., 2004). Franco et al. (2004) found that sun-drying was associated with enhanced concentrations of isobutanol, benzyl alcohol, 2-phenylethanol, 5-methylfurfural, γ-butyrolactone and γ-hexalactone. Modification in terpene content also reflects the drying method (Eberle et al., 2007).

Variations in style often depend on the grape variety or varieties used, and the treatments applied before, during, or after fermentation. For example, Moscato grapes in Sicily may be cured in a solution of saltwater and volcanic ash (at least in the past), before being crushed and fermented.

Vin santo is one of the more internationally available sweet wines derived from partially dehydrated grapes (reaching °Brix of 30 and above). It is produced in several northern Italian regions, but is particularly a specialty of Tuscany. An aromatic style is also produced on the Greek island of Santorini. The grape cultivars used in different regions are usually distinct, including both aromatic and nonaromatic varieties, such as Malvasia Bianca and Trebbiano, respectively. Occasionally, red cultivars are employed, such as Sangiovese and Canaiolo. They are used to make a slightly rosé version (occhio di pernice – eye of the partridge). Varieties possessing thicker skins and open clusters are more suitable, due to their greater resistance to infection during drying. Sulfite salts may be applied to limit mold growth.

In Italy, grapes used to produce vin santo are partially dehydrated on trays, arranged in naturally ventilated rooms (fruttaio) for up to 4 months. The degree of juice concentration depends on the preferences of the producer. The juice must reach a legal minimum of 26% sugar, but can almost double that. During drying, there may be a progressive increase in the presence of Metschnikowia pulcherrima (Balloni et al., 1989), or apiculate yeasts such as Hanseniaspora uvarum and Kloeckera apiculata. These alternations in yeast flora appear to enhance the aromatic complexity of the wine (Domizio et al., 2007). Of particular importance, due to the high osmolarity of the juice, may be the activity of osmotolerant species, such as Candida zemplinina and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii. These may facilitate the subsequent dominance of Saccharomyces yeasts under warmer (16–18 °C) conditions.

After any decayed fruit is removed, the grapes are pressed, and the juice allowed to clarify for several days, before fermentation. Fermentation typically occurs in small barrels (caraelli) of 50 to 200 L capacity (Stella, 1981; Domizio and Lencioni, 2011). These may be coopered from chestnut, cherry, or oak, preferably untoasted. Maturation in partially (80% to 90%) filled barrels can vary from 2 to 6 years, often occurring in attics (vinsantaia). Here the wine is exposed to the annual cycle of temperature extremes. Several rackings are typical during maturation.

The finished wine can vary from light to dark golden, to orange, or amber. Its sensory attributes are characterized, as typical of wines permitted oxidative aging, of raisin, nuts, and hay, with elements of honey, caramel, and cream. Alcohol content can vary from 14% to 17% (or up to 21% in dry styles). They can also range from dry (secco) to sweet (dolce).

Heating

Another ancient technique entails concentrating the juice or semisweet wine by heating or boiling. A classic version is vino catto, produced in the Marche and Abruzzo regions of Italy. It involves heating Trebbiano, Passerina, or Moscato musts in copper vessels over a fire to 80–95 °C, until reduced by 30 to 70%. The treatment results in a loss in varietal character, but generates a caramelized or baked odor, dark melanoidin pigments, and raises the sugar content up to about 55%. After cooling to 35 °C, fresh must is added to contribute some varietal attributes. The mixture is fermented in large cooperage at about 25 °C for 6 weeks. Fermentation involves osmotolerant strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida apicola, C. zemplinina, and Zygosaccharomyces bailii (Tofalo et al., 2009). Aging occurs in barrel. Depending on production procedures, the alcohol content can vary from 8 to 16%, and residual sugar levels range from 83 to 350 g/L (Di Mattia et al., 2007).

Cooked must is also used in the production of marsala in Sicily, and added for color to oloroso sherries in Spain and some madeiras. Another use of heat in wine production is employed in the maturation of madeira.

Icewine

Juice concentration can also be achieved as grapes freeze and most of their water content turns to ice. If the grapes are harvested and pressed frozen, the juice can be used to make icewine (eiswein). Eiswein is reported to have been first produced in Germany in the late 1700s. More recently, the process has spread, and is now a standard technique used in cool viticultural regions, for example Canada and China.

For icewine production, grapes are left on the vine until winter temperatures fall to or below−7 °C to−8 °C (Plate 9.3). During the prolonged overmaturation period, grape chemistry changes, partially due to dehydration. In some cultivars, this has been correlated with thickening of the skin (Rolle et al., 2010). This could be of value in protecting the fruit from splitting in rainy spells; the cellular disruption induced by partial freezing, before temperatures reaching permissible values for harvesting; and may limit invasion by saprophytic or parasitic microbes. Those cultivars typically used in icewine production inherently have relatively thick skins, for example, Vidal and Riesling. Other desired cultivar traits are late maturity, fruit retention at maturity, high acidity, and winter hardiness.

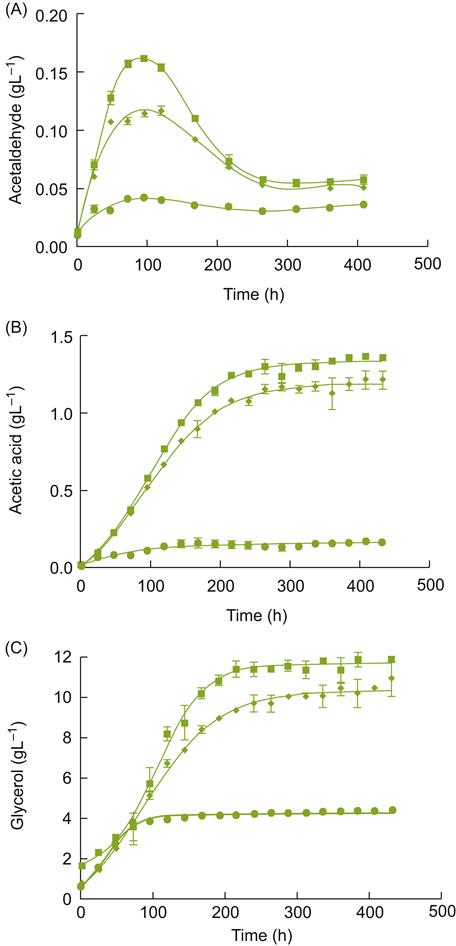

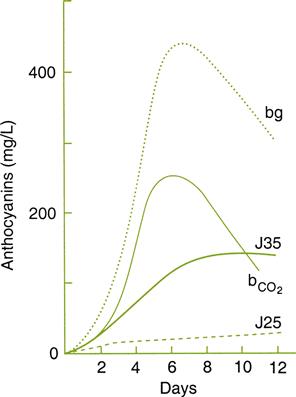

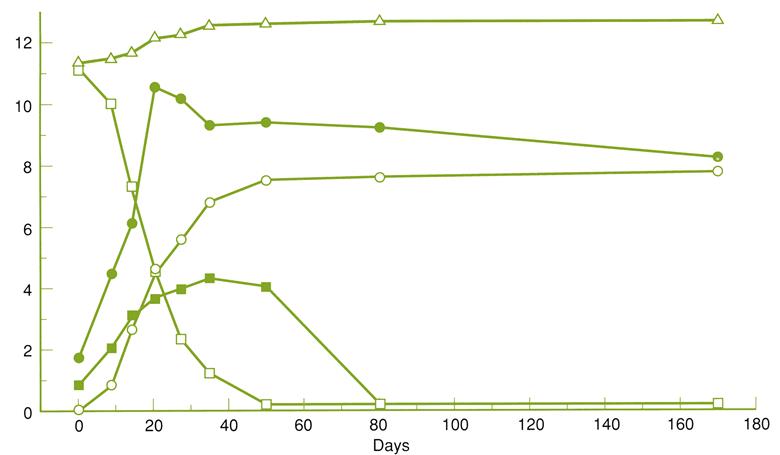

At−7 °C to−8 °C, most of the water in the fruit forms ice crystals, forcing out dissolved substances into the remaining liquid. Harvesting and pressing (under freezing temperatures – Plates 9.4, 9.5 and 9.6) minimize thawing as the concentrated juice slowly escapes. The ice remains in the press with the seeds and skins. Pressing can take upward of 12 h. The presence of stalks facilitates juice escape by producing drainage channels. Rice hulls may also be added, to further assist in juice flow (Plate 7.2). Juice yield is estimated to be about 15% to 20% of what it would have been from the same grapes at regular harvest time. The sugar concentration is typically so high (often above 35°Brix) that fermentation occurs very slowly and stops prematurely, leaving the wine with a high residual sugar content. Incomplete fermentation probably results from the stresses of the high sugar content, combined with the accumulation of ethanol, acetic acid, and toxic C8 and C10 carboxylic acids. One of the adaptations yeasts make to these unfavorable conditions involves aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALD3) (Pigeau and Inglis, 2005). The enzyme converts acetaldehyde to acetic acid. Acetic acid accumulates partially due to a downregulation of enzymes converting acetic acid to acetyl CoA, and its use in fatty acid synthesis. The energy so derived appears to be used to augment glycerol synthesis (Fig. 9.6). Glycerol helps provide osmotolerance by limiting water loss from the cytoplasm.

); chaptalized diluted icewine juice, 35.6°Brix (♦); and diluted icewine juice, 21.3°Brix (

); chaptalized diluted icewine juice, 35.6°Brix (♦); and diluted icewine juice, 21.3°Brix ( ) were inoculated with the commercial yeast K1-V1116. Acetaldehyde (A), acetic acid (B) and glycerol (C) were measured daily throughout the course of the fermentations. Values represent the average±standard deviation of the mean of duplicate fermentations. (From Pigeau and Inglis, 2007, reproduced by permission.)

) were inoculated with the commercial yeast K1-V1116. Acetaldehyde (A), acetic acid (B) and glycerol (C) were measured daily throughout the course of the fermentations. Values represent the average±standard deviation of the mean of duplicate fermentations. (From Pigeau and Inglis, 2007, reproduced by permission.)Because of the difficult fermentation conditions, yeasts are often acclimated before being added to the must (Kontkanen et al., 2004). However, this practice is not universal. Kontkanen et al. (2005) have shown that acclimation and nutrient supplementation can significantly modify the flavor characteristics of the wine. Thus, these procedures may be a means by which the wine can be given a distinctive character, varying from raisiny, buttery and spicy, to peach/terpene-like, to honey and orange, or pineapple/alcoholic. Choice of yeast strain has also been found to significantly affect the accumulation of acetic acid, glycerol, reduced-sulfur odors, and color (Erasmus et al., 2004). Inoculation with about 0.5 g/L active dry yeast is normally required to achieve the preferred 10% alcohol content.

Prolonged overripening may result in a loss of aromatic compounds, but concentration appears to more than compensate for the loss (Bowen and Reynolds, 2012). Cold weather conditions result in an absolute loss in acidity (potassium tartrate crystallization), but juice concentration again assures sufficient acidity to balance the high residual sugar content in the wine (frequently>12.5%). The golden color probably results from the joint effects of juice concentration, caftaric acid oxidation, and the release of catechins on freezing. This counters the reduction in flavonoid and non-flavonoid phenolics associated with overmaturation and partial dehydration at cool temperatures (Kilmartin et al., 2007; Mencarelli et al., 2010).

Although eiswein has been made for at least two centuries in Germany, the worldwide popularity of icewines is comparatively recent. This appears to be correlated with its production in southern Ontario and neighboring portions of the United States. The climatic conditions in these regions seem particularly favorable to fine icewine production. Despite its newfound fame, there is a surprising lack of technical information on the biochemistry involved. Thus, little is known about the changes that occur during overripening, pressing, and fermentation, or the microbiology of its production.

One of the major problems connected with icewine production involves protecting the fruit from birds and other predators, awaiting the first occurrence of an adequately hard freeze. Additional problems include molding during rainy spells, and the less than ideal conditions for manual harvesting and pressing (Plate 9.7). From 20 to 60% of the fruit may be lost before sufficient freezing occurs. Difficulties in achieving adequate fermentation are another frequent complication.

In regions where climatic conditions do not permit natural icewine production, cryoextraction can provide its technological equivalent. This has the advantage of permitting the degree of juice concentration to be selected in advance (Chauvet et al., 1986). It also avoids the risks of leaving the fruit on the vine for months, and the difficulties of harvesting and crushing grapes during frigid winter weather. Reverse osmosis has also been used to produce concentrated juices for making icewine-like wines. These techniques, however, seem to lack the flavor changes that develop during long vineyard overripening. They also lack the mystique, so often important in consumer appeal.

Addition of Juice Concentrate (Sweet Reserve)

The addition of unfermented grape juice (sweet reserve, süssreserve) to dry wine is a widespread technique, first perfected in Germany. It has the advantages of retaining the varietal distinctiveness of the juice, as well as producing no supplemental flavors. If the juice is derived from the same grapes used in making the wine, varietal, vintage, and appellation of origin are not compromised. It may also augment varietal distinctiveness, which is occasionally lost during fermentation. Furthermore, the procedure is technologically simpler and more easily controlled than most other sweetening processes.

If storage is short, refrigeration at or just below 0 °C is adequate, requiring no sulfiting. However, prolonged storage at low temperatures requires the addition of sulfur dioxide (100 mg/L), or cross-flow microfiltration to restrict yeast growth. Several spoilage yeasts are known to grow at near 0 °C. Another option is to treat the juice with heavy sulfiting (~1000 mg/L). Prior to use, the sulfur dioxide is reduced to about 100 mg/L by flash-heating with steam, followed by rapid cooling; heating with nitrogen sparging; or use of a spinning cone apparatus.

An alternative procedure noted above, and typical of many botrytized wines, involves terminating fermentation prematurely. Although successful in retaining residual sugars, it also affects the wine’s chemical composition, retaining the attributes of the fermentation stage at which it ceased (see Figs. 7.21 and 7.22).

Red Wine Styles

Recioto-Style Wines

In contrast to white wines, few red wines are produced with a sweet finish. In this regard, Italy is probably the major producer. The wines are often produced with moderate petillance, for example, Lambrusco from Emilia Romagna, or fortified, as with the Vin Doux Naturels from southern France. The latter is characterized by oxidative and Maillard fragrances (Schneider et al., 1998; Cutzach et al., 1999).

Even fewer red wines are produced from dried (passito) grapes. The process is ancient, being noted by Cassiodorus (A.D. c.485–c.585) in his book Acinatico. The following describes the process being used in the Veneto:

… in the autumn grapes are chosen in the domestic bowers, hung up by the bottom tip, then conserved in jars and in ordinary repositories. They hardened during time, do not liquefy, useless humors are exuded, and the grapes become sweet. This goes on until December, until winter begins, and wine becomes new when in all the wine cellar it is already old.

The recioto wines of Veneto (Valpolicella) and Lombardy are particularly unique in that a portion of the grapes frequently develop noble rot during the drying phase. It appears to develop from grapes possessing quiescent Botrytis cinerea infections, presumably established early in berry development. Usseglio-Tomasset et al. (1980) appear to have been the first to have noticed, or at least published on this occurrence.

Recioto Valpolicella is made from a variable blending of musts from Corvina, Corvinone, Rondinella and Molinara. Nebbiolo or Groppello are used in Lombardy. In Valpolicella, sweet (amabile), sparkling (spumante) and dry (amarone) versions may be produced from the partially dried (passito) grapes. Of these, the most famous and internationally well known is the dry, amarone style. Another example of a red wine, using at least some partially dried grapes, is traditionally made chianti wines, involving what is termed the governo process.

Drying affects grape constituents, notably the total phenol as well as caftaric and coutaric acid contents. The specific influences depend on the temperature at which dehydration occurs, and the degree of dehydration (Mencarelli et al., 2010). Stilbene and flavanol contents may also be enhanced, notably with moderate drying (10 to 20%) at 20 °C. During fermentation, the wines develop a distinctive fragrance and flavor, presumably derived from the processes occurring in the fruit before fermentation. In amarone, the fragrance often contains elements that resemble the sharp phenolic odor of tulip and daffodil flowers. This may arise from phenolic oxidation by laccases (Boubals, 1982). However, this distinctive attribute is limited if the grapes are unaffected by Botrytis. The relative occurrence of B. cinerea probably depends on conditions during flowering. These significantly affect the incidence of nascent grape infections. For the consumer, it is regrettable that the action of Botrytis is not specified, as it is it that donates the most distinctive (desirable) attributes. Otherwise, the result is only slightly different from overmaturation on the vine, and generation of an overly alcoholic wine.

Recioto wines typically have a higher than usual alcohol content, but should have a smoother, more harmonious taste than the majority of full-bodied red wines. Because of the unique botrytized fragrance, recioto wines supply winemakers with an additional means of producing wines with a distinctive character.

Production of Amarone

Healthy, fully mature clusters, or their most mature portions, are placed in a single layer on trays designed to ease air flow around the fruit. The trays are stacked in rows several meters high, in well-ventilated storage areas (fruttaio) (Fig. 9.7; Plate 9.8). Natural ventilation may be augmented with fans to keep the relative humidity below 90%. The grapes are left under cool ambient temperatures to partially dry for several months. The fruit is usually turned every few weeks to promote uniform dehydration. Cool temperatures (3–12 °C), and humidity levels below 90% are crucial to restricting microbial spoilage. Some producers are now experimenting with sophisticated means for controlling humidity and temperature (see Paronetto and Dellaglio, 2011). It is hoped that, by selecting to regulate the drying process (appassimento), it will not reduce the action of Botrytis cinerea.

During the 3–4 month storage period, the physical and chemical characteristics of the grapes undergo major changes These relate partially to the activation of genes associated with dehydration stress (Zamboni et al., 2008). The most obvious effect is the 25 to 40% drop in moisture content. Other critically important changes appear to accrue from the action of B. cinerea. As noted, fungal growth likely originates from latent fruit infections acquired in the spring following berry inception. Under the dry, cool, storage conditions, the fungus reinitiates a slow development. Grape coloration may change from bluish purple to pale red (with less dehydration) (Plate 9.9), or remain typical (with more marked dessication). Surface fungal sporulation, so characteristic of botrytized grapes in the vineyard, is seldom observed in fruttaio.

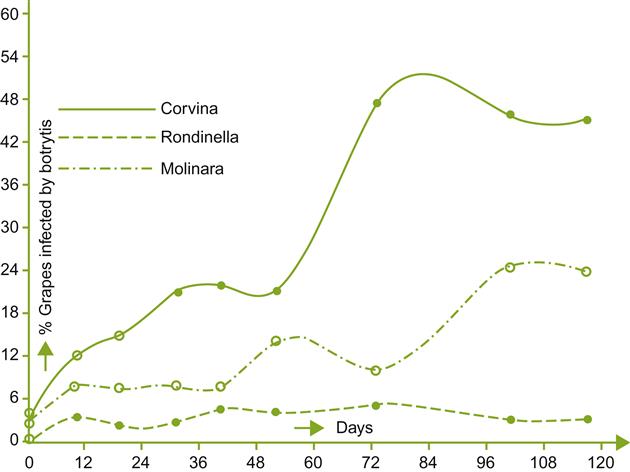

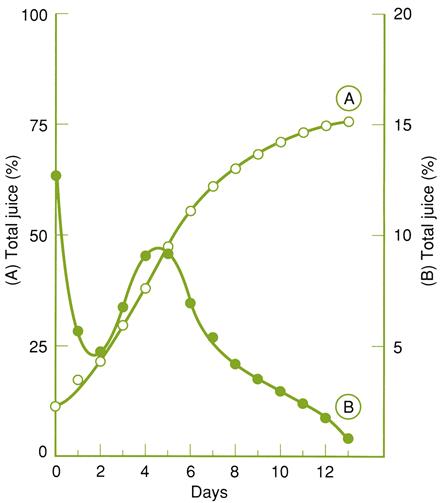

The percentage of fruit showing infection usually increases in relation to the duration of storage, the actual percentage depending on the vintage and variety (Fig. 9.8). Corvina seems the most susceptible, Rondinella the most resistant, and Molinara moderately resistant (Usseglio-Tomasset et al., 1980). The proportion of each cultivar used can vary considerably from producer to producer, but roughly in the following proportions: Corvina (and Corvinone) (40–70%), Rondinella (20–40%), and Molinara (5–25%).

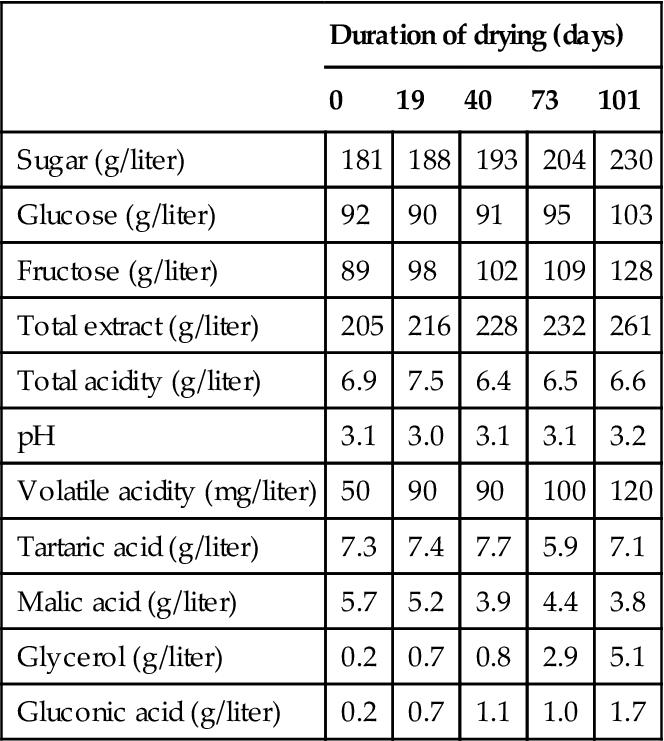

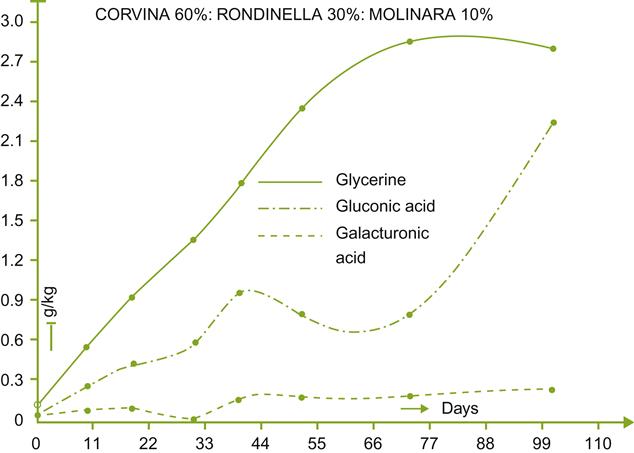

As infection progresses, the grapes become flaccid, and the skin loses its strength. The visual and mechanical manifestations of infection are reflected in even more pronounced chemical alterations (Table 9.4). These changes can show the distinctive effects of noble rotting. Although fungal metabolism reduces the absolute sugar content, water loss results in a marked relative increase in sugar concentration. The °Brix can rise from 25° to over 40° in heavily noble-rotted grapes. Due to the selective metabolism of glucose, the relative proportion of fructose rises. The grapes can also show a marked (10- to 20-fold) increase in gluconic acid and glycerol concentration (Fig. 9.9). Total acidity declines marginally, if at all. Despite dehydration, the tartaric acid concentration remains relatively constant (B. cinerea metabolizes tartaric acid), whereas that of malic acid declines. These data may indicate that selective acid metabolism by B. cinerea during storage differs from that occurring in the vineyard. Alternatively, the atypically low malic acid content may reflect the metabolic action of grapes during prolonged storage.

Table 9.4

Changes in must composition during the drying of grapes for recioto wines

| Duration of drying (days) | |||||

| 0 | 19 | 40 | 73 | 101 | |

| Sugar (g/liter) | 181 | 188 | 193 | 204 | 230 |

| Glucose (g/liter) | 92 | 90 | 91 | 95 | 103 |

| Fructose (g/liter) | 89 | 98 | 102 | 109 | 128 |

| Total extract (g/liter) | 205 | 216 | 228 | 232 | 261 |

| Total acidity (g/liter) | 6.9 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.6 |

| pH | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Volatile acidity (mg/liter) | 50 | 90 | 90 | 100 | 120 |

| Tartaric acid (g/liter) | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 5.9 | 7.1 |

| Malic acid (g/liter) | 5.7 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.8 |

| Glycerol (g/liter) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 5.1 |

| Gluconic acid (g/liter) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.7 |

Source: Data from Usseglio-Tomasset et al. (1980).

Browning and red color loss are noticeable, but are less marked than might be expected, considering the presence of B. cinerea. Reduced synthesis, or the relative inactivity, of laccase seems supported by the resveratrol content of amarone, being up to 10 times higher than in regular (nonbotrytized) Valpolicella (Brenna et al., 2005). This may result from suppression by the high grape sugar content (Donèche, 1991), skin tannins (Marquette et al., 2003), poorly understood factors (Guerzoni et al., 1979), or the resistance of some varieties to infection. In visibly infected botrytized grapes, the must concentration of laccase was about five times higher than that in healthy must (Tosi et al., 2012). Still, this seems considerably lower than that found for botrytized white grapes (Grassin and Dubourdieu, 1989), albeit measured with a different assay technique.

Following storage, the grapes are stemmed, crushed, and allowed to ferment under the action of indigenous yeasts. When a noticeable residual sweetness is desired, the must is kept cool (≤12 °C) throughout alcoholic fermentation. For the dry amarone style, the must may be warmed to, or allowed to rise to, about 20 °C during fermentation. Despite fermentation commencing at 4–6 °C, the alcohol content and temperature can rise to 14–16% and 16–18 °C, respectively, within 3 to 4 weeks (Usseglio-Tomasset et al., 1980).

Fermentation temperature influences the relative presence of different endemic yeasts. Studies have associated various Saccharomyces species with spontaneous amarone fermentations, notably S. uvarum and S. cerevisiae (Usseglio-Tomasset et al., 1980; Dellaglio et al., 2003; Tosi et al., 2009). Each affects the aromatic chemistry of the wine differently. S. uvarum may predominate under cool temperatures, finally giving way to S. cerevisiae as the ferment warms. Fermentation can vary from 20 to 40 days.

Alcoholic fermentation may recommence when ambient temperatures rise in the spring. This may be either prevented by yeast removal (filtration for the amabile style) or encouraged (for production of the spumante style).

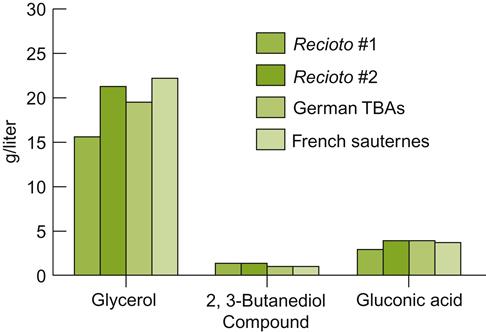

Figure 9.10 shows that the concentrations of glycerol, 2,3-butanediol, and gluconic acid are roughly comparable to those expected of highly botrytized wines. The high levels of both glycerol and alcohol contribute to the smooth texture of the wine. The smooth sensation is undoubtedly aided by the limited extraction of tannins during the cool fermentation phase. Cool temperatures also encourage the production and retention of fragrant esters. In a comparison of amarone wines, derived from healthy and noble-rotted grapes, the presence of 1-octen-3-ol, typically produced by fungi, was surprisingly not increased (Tosi et al., 2012). In addition, there were significant increases in the concentration of phenylacetaldehyde, furaneol, and γ-nonalactone, but a decrease in sherry lactones (diastereoisomers of 5-hydroxy-4-hexanolide). Unexpectedly, there were negligible changes in terpene content.

Because of the cool storage conditions, and wine’s high alcohol content, it is usually necessary to inoculate to induce malolactic fermentation. Alternately, simultaneous inoculation with an acclimated culture of Oenococcus oeni and yeast achieves earlier malic acid reduction (Zapparoli et al., 2009). Spontaneous malolactic fermentation is more likely to occur in the spring and summer in sweet recioto versions. Malolactic fermentation may be the source of the carbon dioxide that occasionally gives the amabile style a slight effervescence.

Amarone wines commonly are aged in oak for 3 years before bottling. This is considered to improve the wine’s fragrance and harmony. For example, tentative studies have shown that benzenoid derivatives (e.g., benzaldehyde, phenyl acetaldehyde, syringaldehyde and vanillin) show significant increases, while most sulfide compounds decrease (Fedrizzi et al., 2011). This is in contrast to similar wine not exposed to the appassimento process. Old cooperage is preferred, to avoid giving the wine a marked oaky character.

Governo Process

Another uniquely Italian process, partially involving grapes undergoing appassimento is the governo process. About 3 to 10% of the grape harvest is kept aside. During a 2-month storage period, these grapes undergo slow partial drying, and associated changes to their chemistry and flora. The population of apiculate yeasts, such as Kloeckera apiculata declines markedly, whereas the proportion of Saccharomyces cerevisiae increases (Messini et al., 1990).

After storage, the grapes are crushed and allowed to commence fermentation. At this point, the fermenting must is added to wine previously made from the main portion of the crop. The cellar may be heated to facilitate the slow refermentation of the mixture. The second yeast fermentation, induced primarily by S. cerevisiae, donates a light frizzante that enhances the early drinkability of the wine. The process also appears to delay the onset, if not the eventual occurrence, of malolactic fermentation.

Few studies of this traditional process have been conducted. This is regrettable, not only for this, but also for other traditional but regional procedures. Knowledge and experience, developed over centuries, if not, millennia, are at risk of being lost, under the relentless advance of market dictates and economics.

Carbonic Maceration Wines

In its simplest form, a procedure resembling carbonic maceration may be as old as winemaking itself. The involvement of incidental berry autofermentation in winemaking was probably widespread until the introduction of efficient mechanical crushers in the nineteenth century. Mechanical crushers permitted complete, rather than partial fruit crushing – the result of treading underfoot or other procedures. Regrettably, for historians, there is little direct recorded evidence of its involvement. Nonetheless, from descriptions of how wines were made at estates, such as Château Lafite in the 1800s, berry autofermentation must have been common (Henderson, 1824; Cocks, 1846). In addition, grape pressing, often a week or more after harvesting, appears to have been extensive in Champagne (Guyot, 1861). Depending on how they were stored, autofermentation is a distinct possibility. The procedure’s beneficial effect was considered common knowledge, such that Louis Pasteur (1876) could say ‘… tout le monde sait …’. Currently, only in a few regions, notably Beaujolais, has this process remained an integral, essential, and dominant feature of wine production. Documentary evidence of its extensive use is noted in Chauvet (1971).

The classic beaujolais procedure differs from carbonic maceration in not flushing the grapes with carbon dioxide in the fermentor; uses a shorter autofermentation period (5 to 6 days); involves some pumping over; and is associated with about 20% berry rupture during fermentor loading. Little sensory difference between the two procedures was noted (Chauvet, 1971). The use of a carbonic maceration-like process is reported to have been used in Rioja, Spain, at least as early as 1947 (Amerine and Ough, 1968). Its use is probably much older.

Grapes are well known to metabolize malic acid, especially during ripening under warm conditions. Although carbonic maceration favors malic acid decarboxylation, the process is not specifically used for de-acidification. Its primary intent has been to produce early maturing wines. This certainly would have been a desirable feature during the so-called Dark Ages. In addition, the presence of a unique and distinctly fruity aroma, combined with creative marketing, generated the Beaujolais Nouveau est ici frenzy of the 1980 and 1990s. The craze still gushes, but more tranquilly today. Nevertheless, their image as light, quaffable wines has led to many critics to unjustly malign all wines produced using carbonic maceration or its variants.

Because of the technique’s largely regional use, the study of grape berry fermentation has garnered little attention outside southern France and parts of Italy. With the popularity of nouveau-type wines, interest in the process expanded. The Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique in Montfavet, France has been the primary center for investigation. Interestingly, the study of autofermentation evolved not out of an interest in nouveau-style wines, but as a means of extending berry storage. Grapes were placed under a blanket of carbon dioxide, similar to that used commercially for apple storage. Although unsuccessful in its intended purpose, submerging grapes in an atmosphere of carbon dioxide resulted in Flanzy proposing a new vinification procedure (Flanzy, 1935). The process came to be called carbonic maceration. Incidentally, it shed light on the ancient, and now traditional, process used in producing beaujolais, and to a limited extent, other European wines. The coiners of the term are opposed to extending its use to these ancient procedures (personal communication). Nonetheless, much of the world has adopted carbonic maceration to describe all winemaking procedures involving the extensive use of grape berry autofermentation. This practice is applied here.

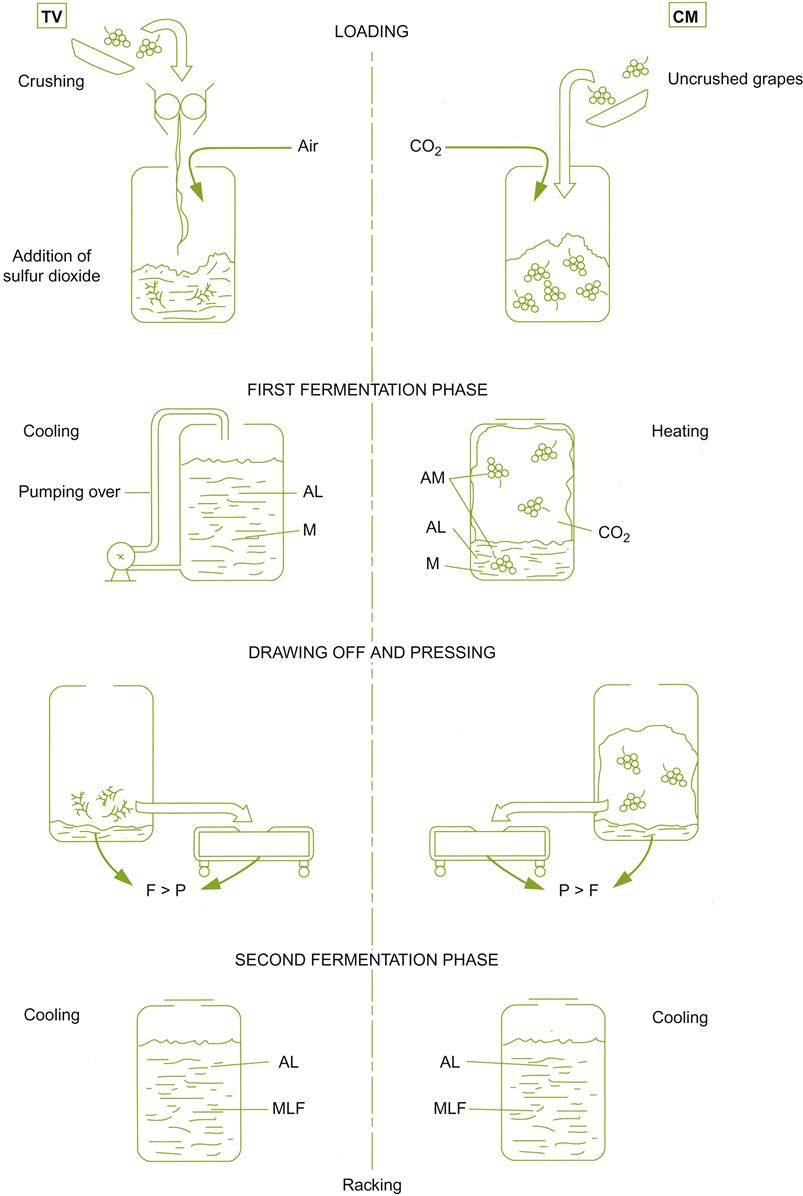

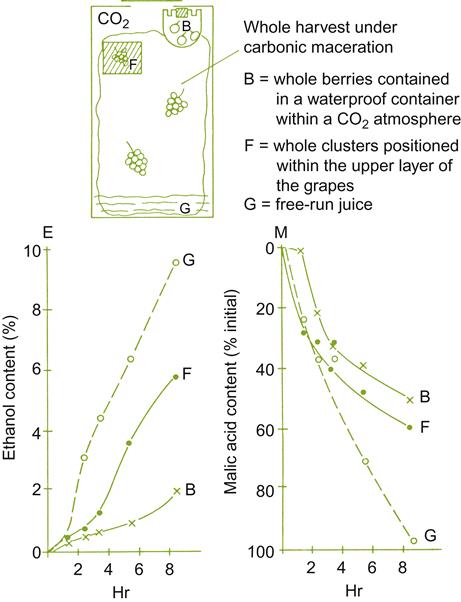

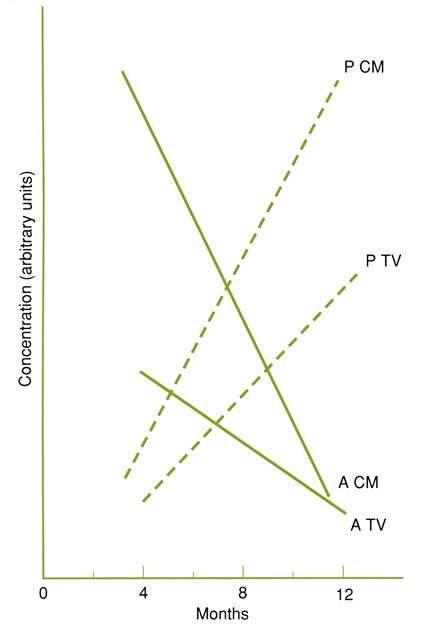

Figure 9.11 compares carbonic maceration-based vinifications with traditional vinification. Carbonic maceration differs fundamentally from standard procedures in that the berries undergo self-fermentation, before being crushed and the onset of standard alcoholic and malolactic fermentations. For maximal benefit, it is essential that the fruit be harvested with minimal breakage.

Typically, beaujolais-style carbonic maceration involves the presence of a small amount of must. It is released when some of the fruit ruptures when being loaded into the fermentor. Thus, berry fermentation typically occurs simultaneously with limited alcoholic (yeast) fermentation.

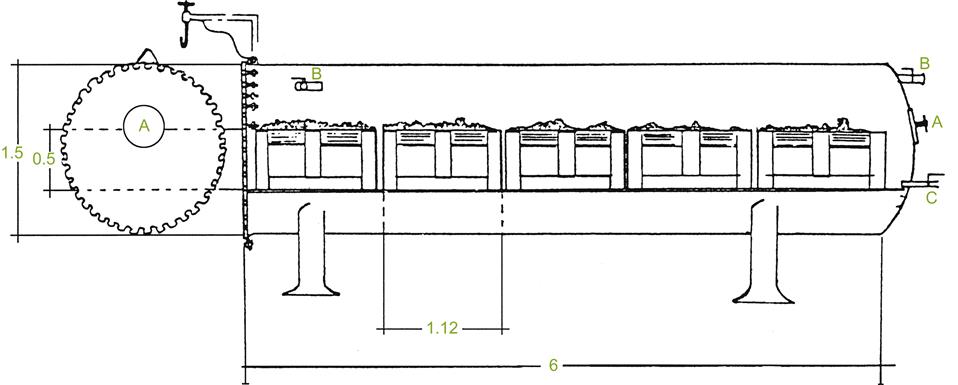

If fruit is not dumped into the fermentor, anaerobic maceration occurs (at least initially) in the absence of free juice – pure carbonic maceration. This occurs when grapes, still in their harvest containers, are placed in sealed chambers (Fig. 9.12), or left in the containers in which they were transported to the winery, and then wrapped in plastic film (e.g., polyvinylidene chloride). Pigment extraction during this phase is usually poor. Thus, the juice is left to ferment in contact with the seeds and skins after crushing, until the desired color has been achieved. If, however, deep coloration is not critical, sufficient berries may collapse and rupture during carbonic maceration to achieve adequate pigmentation.

Typically, the whole harvest undergoes initial carbonic maceration. However, in some regions, only part of the crop may undergo carbonic maceration. For example, carbonic maceration may be used to partially mask the intense aroma of cultivars, such as Concord (Vitis labrusca) (Fuleki, 1974), or several French-American hybrids (Garino-Canina, 1948). With Bordeaux cultivars, such as Cabernet, more than 85% of the fruit must undergo carbonic maceration for the varietal aroma to be suppressed (Martinière, 1981). Thus, modifying the uncrushed proportion of the crop has the potential to adjust the relative contribution of carbonic maceration vs. varietal character. The intensity of the carbonic maceration aroma may also be modified by influencing its duration and temperature. Alternatively, carbonic maceration wine may be blended with must vinified by standard procedures.

At the end of carbonic maceration, the grapes are pressed and the juice allowed to ferment to dryness by yeast action. Malolactic fermentation typically occurs shortly after the termination of alcoholic fermentation. After completing malolactic fermentation, the wine typically receives a light dosing with sulfur dioxide (20–50 mg/L). This helps prevent further microbial action. Racking commonly occurs at the same time. Racking may be delayed for several weeks, however, to derive flavor attributes donated by yeast autolysis.

Although carbonic maceration is used most extensively in the production of light, fruity, red wines, it can yield wines capable of long aging. The procedure has also been used to a limited extent in producing rosé and white wines.

Advantages and Disadvantages

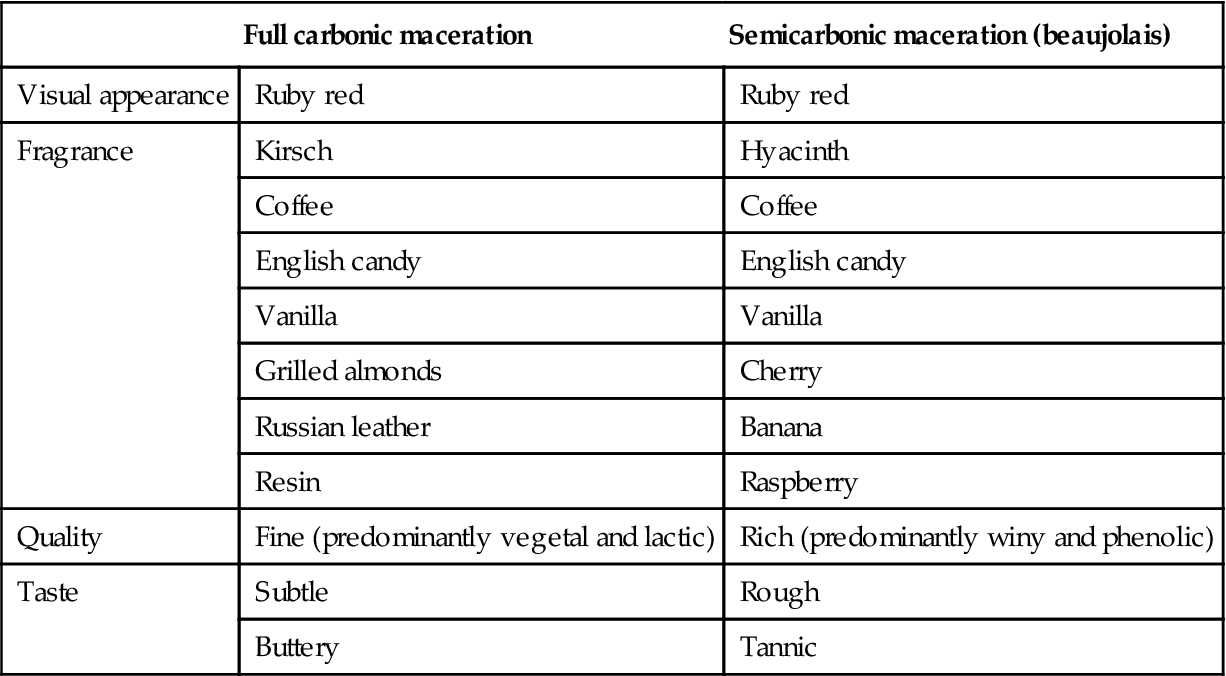

Carbonic maceration donates a unique, fruity aroma. This feature has been variously described as possessing kirsch, cherry, or raspberry aspects. Additional descriptors are noted in Table 9.5.

Table 9.5

Sample descriptors used to describe certain carbonic maceration wines

| Full carbonic maceration | Semicarbonic maceration (beaujolais) | |

| Visual appearance | Ruby red | Ruby red |

| Fragrance | Kirsch | Hyacinth |

| Coffee | Coffee | |

| English candy | English candy | |

| Vanilla | Vanilla | |

| Grilled almonds | Cherry | |

| Russian leather | Banana | |

| Resin | Raspberry | |

| Quality | Fine (predominantly vegetal and lactic) | Rich (predominantly winy and phenolic) |

| Taste | Subtle | Rough |

| Buttery | Tannic |

Source: After Flanzy et al. (1987). © INRA, Paris, reproduced by permission.

For relatively neutral varieties, such as Aramon, Carignan, and Gamay, carbonic maceration provides an appealing fruitiness that standard vinification does not yield. With cultivars, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Concord, carbonic maceration may, to varying degrees, mask the varietal aroma. This may be desirable or not, depending on the appeal of the aroma. With other cultivars, such as Syrah and Maréchal Foch, carbonic maceration has been reported to enhance the complexity of the varietal fragrance. The observed reduction in the herbaceous character of several French-American hybrids may result from the curtailed production of hexan- and hexen-ols (Salinas et al., 1998). Carbonic maceration has even been reported to enhance the varietal aroma detected in some white wines (Bénard et al., 1971).

Because standard vinification extracts more tannins than carbonic maceration (Pellegrini et al., 2000), the process may be preferable when used with highly tannic grapes. The potential for deacidification might also partially justify its use with acidic grapes.

Carbonic maceration wines seldom demonstrate a yeasty bouquet after completing vinification. The wine, which also has a smoother taste, can thus be enjoyed sooner. This has financial benefits, because the wines can be bottled and sold within a few weeks of production. Thus, capital is not tied up for years in cellar stock.