High seed costs, the need for Rhizobium inoculation, and higher water demands can limit legume feasibility. Occasionally, these disadvantages may be avoided with self-seeding legumes, such as burr clover. Cereal crops require less water and can often penetrate and loosen compacted soil. Consequently, a mix of legumes and grasses is frequently used (Winkler et al., 1974). This has the additional advantage of providing a greater range of habitats for beneficial insects, enhancing potential pest control. Nevertheless, the habitat provided must be carefully selected to avoid favoring rodent populations. Positioning nesting or resting sites for owls and hawks in or adjacent to vineyards can help control rodent pests and have the additional advantage of minimizing bird damage (Saxton et al., 2009; Saxton and Kean, 2010).

The effect of groundcover choice on the grape flavor has rarely been considered. Work by Feng et al. (2011) is beginning to shed light on this potentially significant issue. For Pinot noir, cover crops can influence the wine’s sensory attributes.

Composting

Except for green manures, most organic fertilizers are best initially composted. Composted material is less variable in chemical composition, and its nutrient content released more slowly. Compost can also have additional benefits, such as acting as a mulch (reducing water evaporation) and helping in annual weed control. Co-composting with winery wastes (stalks, seeds, and pomace), winery or vineyard wastewater, or sewage sludge helps convert these materials into a product that can be more safely added to vineyard soils. Experimentation is required to establish an effective formula for efficient and effective composting. For example, excessive water content complicates composting. Occasionally, sewage sludge is contaminated with heavy metals, obviating its use (Perret and Weissenbach, 1991).

Simple composting involves mounding the waste into windrows, frequently 1.5 m high, 2 m wide, and 4 m or more in length. These have sufficient size to insulate the interior, permitting its temperature to rise to 55–70°C. The heat, generated by microbial activity, selects thermophilic bacteria and fungi that quickly degrade most readily decomposable organic material. The combination of heat and microbial decomposition also tends to pasteurize (but not sterilize) the waste, reducing most plant pathogens and weeds to undetectable levels (Noble et al., 2009). Its effect on grape virus inactivation appears not to have been investigated. Data on other viruses suggest that exposure to temperatures near 70°C for 3 weeks is effective in eliminating most viruses. Thus, systems that do not expose all the material to adequate temperatures are probably best avoided if the compost is to be applied to vineyards.

Because composting is most efficient when microaerobic, the mounds are turned periodically. Frequency depends on the rapidity with which the internal temperature rises. Temperatures above 65–70°C inhibit the action of the most desirable thermophilic microbes. Turning not only avoids overheating and incorporates material from the exterior, but also provides adequate oxygenation for the required microbial activity. This also avoids off-odor production from anaerobic activity. To further assist oxygen penetration, bulking agents such as wood chips, corn cobs, corn stalks, or straw are often incorporated. They provide aeration channels, as well as drainage passageways for water escape. Wood chips have the advantage that they do not decompose readily and can be separated for reuse. In so doing, they can act as a natural inoculum of desirable microbes for the next compost pile. Commercial inocula are available, but are seldom necessary if some finished compost is incorporated into the new piles.

Moisture levels ideally should be between 50 and 60%. Higher levels tend to shift metabolism toward anaerobiosis and malodor production. In addition, higher moisture levels can promote continued fermentation of ethanol to acetic acid, reducing the pH. At below 40% moisture content, decomposition is retarded.

Alternative composting techniques include windrows with aeration supplied by pumping air through perforated tubes under the static piles, silo-like vertical systems, agitated beds, plug-flow systems, and rotating drums (Arvanitoyannis et al., 2006). Choice depends primarily on space availability, need for speed, and economy. Where the first two are not of primary concern, windrows are usually the preferred choice.

Where the substrate consists primarily or solely of spent pomace, the pH must be raised to near neutral (6.5–7). This is required for activity of the thermophilic microbes involved in decomposition. Raising the pH usually involves the incorporation of lime into the mix. It is estimated that such use can return up from a third to half of all the nutrients removed at harvest back to the soil. Rates of application tend to vary between 2.5 to 10 kg/hectare. If the soil is saline or sodic, it may be necessary to add a source of calcium before application. Sodium levels may be higher in the pomace than desired, especially if winery wastewater has been incorporated. This can come from sodium-based cleansing agents used in the winery. Potassium contents may also be undesirably high. If the wastewaters come from municipal sources, additional sources of potential soil contamination can be a concern.

Once bacterial mineralization brings the carbon/nitrogen ratio close to 20:1, microbial activity in the compost slows, and the temperature falls. Further composting shifts to fungal action. The latter is particularly important in the humification of much of the remaining organic material. This partially involves the condensation of lignin-derived phenolics with ammonia. The humus so derived is refractory and mineralizes only slowly in soil. Thus, it makes an excellent soil amendment. Subsequent maturation involves degradation or volatilization of potential phytotoxins, such as ethylene oxide, ammonia, and low-molecular-weight fatty acids (notably acetic, propionic, and butyric acids). After some 12–24 weeks (depending on the temperature, moisture, and nutrient content, as well as turning frequency), the compost can be safely used as an organic amendment or mulch.

Disease, Pest, and Weed Management

Changes similar to those affecting vineyard fertilization are affecting disease, pest, and weed management. At the extreme edge of this change are schemes relying totally on organic and biodynamic concepts (Jenkins, 1991; Reeve et al., 2005). Although the latter are currently in vogue, principles of sustainable viticulture, which include advances in integrated pest management (IPM), at least have a solid scientific foundation (Broome and Warner, 2008). They are based on verifiable data, not quasi-philosophic concepts related to the long-disgraced concepts, the equivalent to élan vital. ‘Natural’ pesticides, such as phosphoric acid (Foli-R-Fos®), canola oil (Synertrol®) (Magarey et al., 1993), and potassium silicate (Reynolds et al., 1996) can occasionally be as effective as standard pesticides. This is not a consistent finding, though, with higher concentrations often being required (Schilder et al., 2002). In addition, there is no guarantee that ‘organic’ control agents are any more environmentally friendly or safe for human consumption than ‘synthetic’ control agents (Bahlai et al., 2010). After all, to be effective, they must be inherently toxic. Only those compounds or adjustments that modify the ecological niche (to the detriment of the pest) or modifications of the canopy microclimate are likely to have minimal or limited environmental impact.

Little, if any, research has been conducted on the effects of pesticides (natural or man-made) on the aromatic composition of wine. One study showed an effect, but most influences were below threshold values, with the exception of ethyl acetate and isoamyl acetate (Oliva et al., 1999). Other investigations have shown that organically produced grapes or wines can be as good quality as those traditionally produced (Henick-Kling, 1995; Hill, 1988). However, the wines were not shown to be demonstrably better. That organically produced wines are ‘healthier,’ or more beneficial to the environment, is unsubstantiated. Increases in the diversity of the soil fauna and flora are not inherently better (Lotter et al., 1999; Mäder et al., 2002). If ‘natural’ was always better, then disease should not be controlled. Disease is part of the natural environment.

That organic procedures may be adopted as a concession to vocal advocacy groups, or as part of a marketing strategy to gain access to a niche market, is one thing, but claims of superiority are another. If consumers, desiring wine produced by organic or biodynamic concepts, are willing to pay for these options, fine. What is discouraging are unsubstantiated claims that conventional procedures are inherently bad, and medieval procedures automatically good. In an ideal world, consumers would be taught the realities of pest management. Regrettably, this is neither feasible nor would it be effective against a mind set that is distrustful of agricultural firms and science in general. Blind faith is often comforting, reality uncomfortable.

Minimizing environmental damage is a laudable goal, but, as noted, natural pesticides are no more guaranteed to be safer than their synthetic counterparts. For example, Stylet-Oil reduced grapevine photosynthesis and the accumulation of soluble solids in the fruit (Finger et al., 2002). The effects were volume- and frequency-dependent. In an extensive study of natural vs. synthetic pesticides, the percentage potentially carcinogenic was the same, about half (Gold et al., 1992; Ames and Gold, 1997). (Because of their low concentration in food, none was considered to constitute a significant cancer risk.) In addition, accepted pesticides used in organic viticulture may disrupt the action of natural disease control agents. For example, sulfur can increase the mortality of Anagrus spp., a biocontrol agent of leafhoppers (Martinson et al., 2001), and suppress tydeid mite (Orthotydeus lambi) populations. This mite can reduce the incidence of powdery mildew (English-Loeb et al., 1999). These comments should not be construed as an attack on so-called ‘natural’ controls. No one, at least not me, advocates using anything more toxic or disruptive than necessary. What is required is honesty and objectivity, based on verifiable data, not apocryphal statements pontificated with missionary zeal. As more data on biological control accumulates, one will be able to establish its real value, and limitations, from potential.

In this regard, natural pesticides should require the same exhaustive assessment for efficacy, safety, and residue accumulation as synthetic agents now require. Lack of data should not inherently give rise to a false sense of security. This can lead to cases, such as with pyrethroids, where increased use leads to their accumulation in stream sediments to toxic levels for bottom dwellers (Weston et al., 2004). In addition, various oils used in organic pest control can affect the taste and odor of grapes and wine (Redl and Bauer, 1990). Although health concerns about the risks of pesticide use have induced several governments to contemplate pesticide deregistration, little thought has gone into the human health risks of the potential human health risks of increased mycotoxin contamination. This could have unconscionable consequences, as have other well-intentioned but ill-advised government reactions. Nevertheless, the inability of current pesticides and herbicides to provide adequate crop protection, and the need to reduce production costs, has wisely spurred research into alternative control measures. In addition, natural toxins can direct the search for, and synthesis of, even more effective and stable synthetic products, as has been the case with human medications (Petroski and Stanley, 2009).

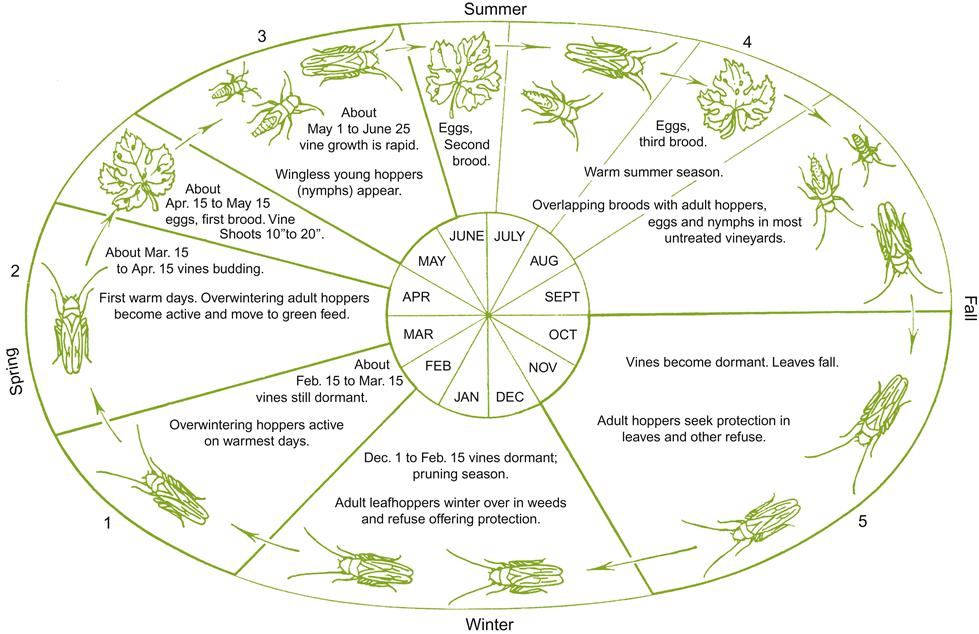

One of the main concepts generating better and more cost-effective pest and disease control is IPM. The term ‘management’ reflects a paradigm shift – that of limiting damage to an economically acceptable level (its economic threshold). Limiting damage to an economic or sensory insignificant level is more feasible and prudent than attempting what is often impossible – absolute control or eradication. Integrated pest management combines the expertise of specialists in diverse but cognate fields, notably plant pathology, economic entomology, plant nutrition, weed control, soil science, microclimatology, statistics, and computer science. Coordinated programs usually reduce pesticide use significantly (Broome and Warner, 2008), while achieving improved effectiveness. IPM programs are more pragmatic and data-based than organic or biodynamic approaches. IPM often includes factors such as environmental modification and assessment, biological control, better synchronization of pesticide use and rotation, and the avoidance or limitation of undesirable interactions. Timing pesticide application to coincide with vulnerable periods in a pathogen’s life cycle usually reduces the number of applications, while increasing effectiveness. It also promotes optimal pesticide selection and application, appropriate to the situation; for example, use of a simpler (less specific) protective agent when disease stress is low, and application of a curative agent (more selective and often systemic) when disease incidence is likely to be high. This approach is much less disruptive to indigenous biological control agents. Advances in disease forecasting, combined with monitoring pest or disease incidence, permit more accurate prediction of potential damage. Because most models have been developed with data collected over a fairly large area, their predictive value may be inappropriate at sites deviating significantly from the norm. Only with extensive use is it possible to adjust predictions to specific vineyards and vineyard conditions.

In addition, risk assessment (the cost/benefit ratio) is being increasingly used to regulate if, and when, application is warranted. For example, spider mites are often considered a serious grapevine pest; however, little significant effect on yield and quality may develop even with heavy infestations of the European red mite (Panonychus ulmi) (Candolfi et al., 1993). Vine capacity may be less affected than appearance might suggest, due to compensation by the root and/or shoot system to foliage damage (Hunter and Visser, 1988; Candolfi-Vasconcelos and Koblet, 1990; Fournioux, 1997). Compensation is more evident early in the season; less so later.

Timing applications has been greatly facilitated by the combination of developments in computer hardware and software, miniaturization of solar-powered weather stations (Plate 4.13) (Hill and Kassemeyer, 1997), and geographic information system (GIS) technology. Their joint use has permitted the development of expert systems that can predict the incidence of disease and pest outbreaks, similar to weather forecasts. Such systems can also provide data to adjust irrigation schedules. Computer programs are now available for major diseases in several viticultural regions.

Although the economic and ecologic benefits of IPM are obvious, its successful implementation has been far from simple. The major factor involves its considerable developmental costs. It takes years to develop an effective program, requiring the dedication of specialists in many fields. Without their various skills, forecasting consequences with the requisite accuracy would be impossible. For example, the most efficient fungicides against a particular plant pathogen may be toxic to parasites of an equivalently significant pest. As well, reduction in pesticide use may lead to secondary pest outbreaks. For example, adoption of an IPM program, largely dependent on biological control agents for the western grape leafhopper in California, coincided with an infestation of variegated leafhoppers. Even seemingly unrelated changes in viticultural practice can affect IPM efficiency. For example, herbicide use to reduce loss of soil organic matter, and eliminate sites for pest overwintering, can increase the incidence of certain fungal diseases. In addition, improved nitrogen availability can diminish inherent disease resistance.

IPM systems must also be sufficiently flexible to accommodate variability in disease/pest severity, associated with regional and annual climatic fluctuations. Finally, predicting the economic benefits of IPM programs is fraught with enigmas. In most instances, the financial losses actually ascribable to specific pest and disease agents are guesstimates at best. In some instances, reduced yield may permit the optimal ripening of the remaining fruit. Thus, calculating the cost/benefit ratio of control strategies is fraught with difficulty. Pesticide application is too often driven more by fear than need – the ‘ounce of prevention’ concept. As a result, full implementation of IPM strategies tends to be regional, and more directed toward the most economically significant disease and pest agents. Although not perfect, IPM offers a more integrated and rational approach to disease and pest management than any other process. It can also deliver both economic savings and environmental benefits.

Although IPM is preferable, individual components can be of considerable value alone. For example, research on pesticide combinations can avoid potential mutual interference, and reduce application rates and frequency (Marois et al., 1987). Improvements in nozzle and sprayer design now provide better and more uniform chemical spread, reducing runoff and drift, while achieving better pest or pathogen contact. Assuring that a greater percentage of the target receives a toxic dose can delay the development of resistant strains. In contrast, sublethal doses selectively favor the survival (and reproduction) of pathogens and pests that inherently possess partial resistance to the control agent.

The most efficient nozzles available are those that give a small negative charge to the droplets as they are released (electrostatic sprayers). Plant surfaces (positively charged) attract the droplets, facilitating their uniform deposition, and limit removal by rain. Restricted variation in droplet size (optimum between 25 and 100 μm), and reduced water volume, minimize runoff and drift (from the vaporization of very small droplets). Improved uniform coverage also has the advantage of reducing the development of pesticide resistance. Non-uniform spread facilitates resistance evolution by selectively eliminating susceptible and moderately tolerant strains, leaving only the most insensitive to propagate and multiply. Greater efficiency of application may be achieved by spraying at night, when conditions are calm and evaporation from droplets is retarded. In addition, assessment of effective leaf area can be used to fine-tune dosage application (Siegfried et al., 2007).

IPM emphasizes a diversity of control measures rather than any one technique (Basler et al., 1991). Experience has indicated that dependence on any single control measure is likely to be ultimately unsuccessful. The same is equally probable with biological or genetic control schemes, especially if used to the exclusion of other control procedures. Because most pathogenic agents multiply and can evolve exceedingly rapidly, they are disappointingly adept at developing resistance to single selective pressures. They outnumber us by multiple orders of magnitude – a pathology example of ‘For many are called, but few are chosen’ (Matthew 22:14).

Pathogen Control

Chemical Methods

Faced with increasing pesticide resistance, and the difficulty and expense of finding new control agents, limiting resistance development has become imperative (Staub, 1991). Relatively nonselective contact agents are best used when prophylactic protection against a wide range of pathogenic fungi and bacteria is required – their broad-spectrum action minimizes the likelihood of them developing tolerance. Conversely, their broad-spectrum action is also one of their disadvantages – they are likely to be toxic to biological control agents as well. Nonetheless, occasional use, as needed, can preserve the selective and curative action of systemic agents for critical situations, where their precise action is most needed. By being incorporated into the plant, and frequently translocated beyond the site of application, systemic agents can inactivate pathogens and pests within host tissues, something contact pesticides cannot do. Systemic agents also tend to be less toxic to other organisms, notably the host. As such they are likely to be less toxic, or nontoxic, to potential biocontrol agents. In addition, they can often be applied at lower dosages. Dosage rates for contact agents tend to be in the range of 1000–3000 g/ha, whereas systemic application rates are more in the 400–500 g/ha range. Disease forecasting, the prediction of disease outbreaks based on meteorological data, is particularly useful in timing their application. It reduces the need for frequent application, and increases the effectiveness of what is applied. Where disease forecasting is not available, appropriate timing of application can often be scheduled based on the phenologic (growth) stage of the vine, and the pathogen’s life cycle. The precision permitted by the Modified E–L System (see Fig. 4.2) is well adapted to the spray timing.

Resistance to nonspecific (contact) pesticides tends to be slow to nonexistent. Single mutations are unlikely to provide adequate protection against the nonselective, extensive disruption of membrane structure and enzyme function induced by contact pesticides. When the availability of many nonselective fungicides began in the late 1940s, the destructive potential of several marginally important pests was forgotten. Their potential destructiveness reappeared only when the use of selective pesticides began to replace nonselective pesticides (Mur and Branas, 1991). For example, the increased incidence of the omnivorous leafroller in California can be partially attributed to reduced use of nonselective pesticides against grape leafhoppers (Flaherty et al., 1982). This has, in the case of organic viticulture, encouraged the use of nonselective pesticides, such as oils (e.g., Stylet-Oil), plant poisons (e.g., pyrethroids), or bacterial toxins (e.g., Bt toxin).

In contrast, selective and systemic agents tend to have highly specific toxic actions. These usually involve precise molecular sites on, for example, a particular mitochondrial enzyme or specific membrane component. Regrettably, this specificity facilitates their inactivation (tolerance) by single mutations in the pathogen. Initially, resistant populations tend to be less viable, due to a partial impairment of the active site associated with the mutation. However, after prolonged selective pressure, subsequent mutations may restore biological fitness, such as overexpression of genes of an alternative metabolic pathway. Other examples of competitively neutral resistance factors could involve mutations regulating ABC (ATP-binding cassette) and MFS (major facilitators super-family) transport proteins (Del Sorbo, 2000). These have the capacity to translocate fungicides out of the cell before they can produce significant metabolic damage. At this point, terminating application of the particular pesticide has minimal effect in reducing the population of resistant strains. They have become as ecologically competitive as pesticide-sensitive strains. Thus, for long-term effectiveness, selective and systemic chemicals are best limited to use only in situations where their precise in-tissue toxicity is required (Delp, 1980; Northover, 1987).

Another approach, which tends to prolong the effective ‘life span’ of selective pesticides, involves rotational application. By alternating among pesticides that have differing modes of action, the advantage of resistance genes against any one control agent may be delayed, if not completely avoided. Furthermore, absence of sustained pesticide pressure minimizes the likelihood of enhanced ecologic fitness being selected amongst resistant strains. Unfortunately, success in retarding the accumulation of resistance using rotation is not guaranteed (Baroffio et al., 2003).

An alternative approach involves a combination of nonselective and selective pesticides. Nonselective fungicides nonspecifically reduce the size of the pest or pathogen population – thereby reducing the likelihood of resistant gene selection in those escaping a toxic exposure. This approach has been accredited with delaying the emergence of resistance genes in some pathogen populations (Delp, 1980). Surveying resistance in local populations is an important component in assessing the continuing efficacy and value of any pesticide.

Another approach to delaying the development of stable pesticide resistance is the joint application of two or more selective pesticides. Theoretically, this vastly reduces the chances of resistance development. For example, if the probability of insensitivity to any one agent were equal to 1×10−8, the combined likelihood of any organism surviving (possessing or developing simultaneous resistance) to both agents would be (1×10−8)(1×10−8)=1×10−16. If three pesticides were applied together, the likelihood of a pest developing resistance to all three would fall to 1×10−24 (effectively nil). Although feasible, the cost of such application argues against it. An alternative is the joint application of a less expensive contact with the selective agent.

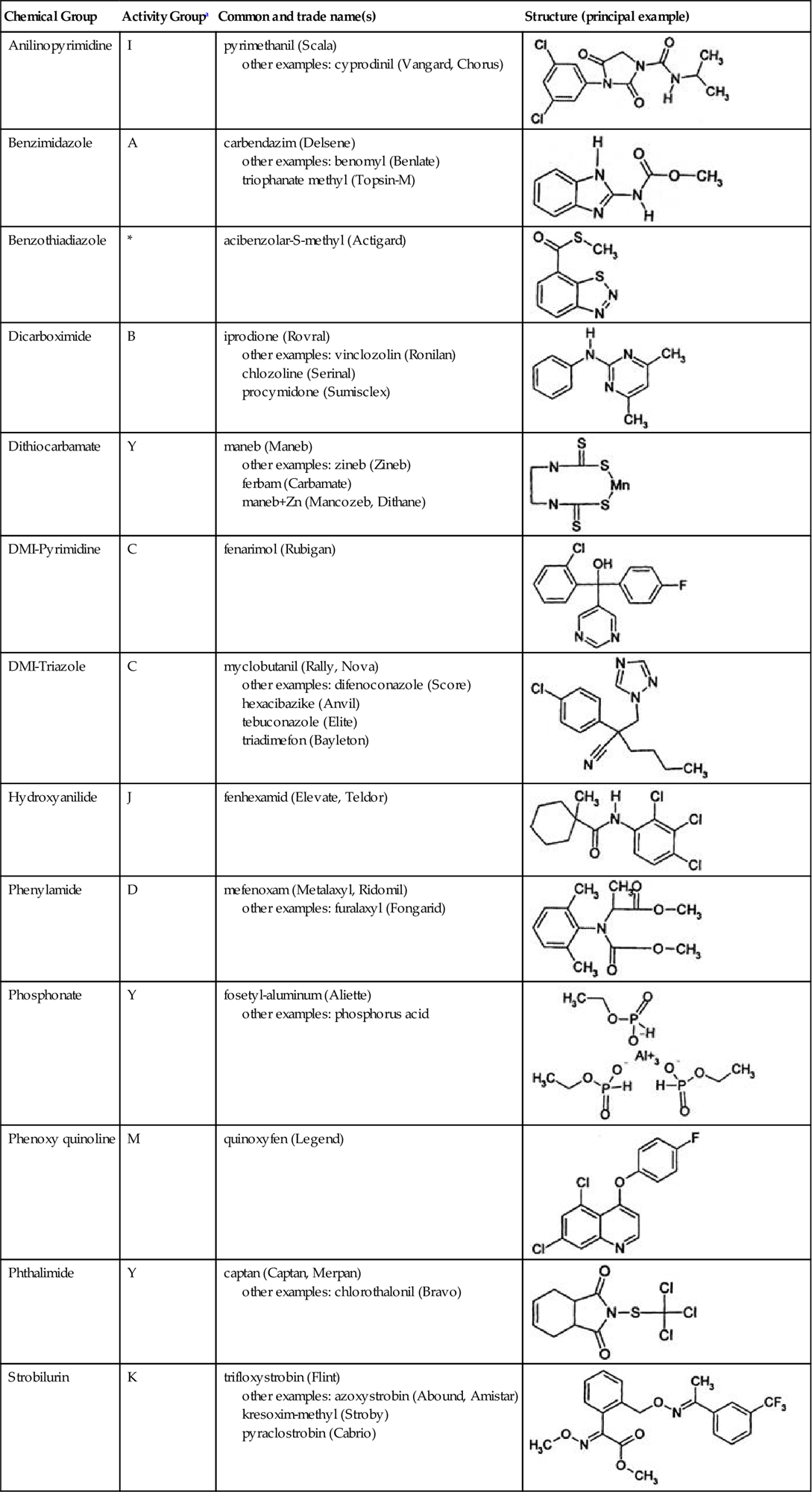

In both approaches it is important that each agent possesses unrelated toxic actions, typically associated with being in different chemical groups (Table 4.13). If the chemicals have similar modes of toxicity, the selective pressures they produce are likely to be equivalent. In this situation, resistance to any member of a group may donate resistance to other members of the group – a phenomenon termed cross-resistance.

Table 4.13

Examples of Fungicides Used in Controlling Grape Diseases, Arranged According to Chemical Family

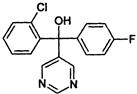

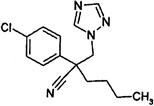

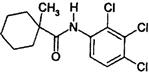

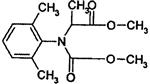

| Chemical Group | Activity Groupa | Common and trade name(s) | Structure (principal example) |

| Anilinopyrimidine | I | pyrimethanil (Scala) other examples: cyprodinil (Vangard, Chorus) |

|

| Benzimidazole | A | carbendazim (Delsene) other examples: benomyl (Benlate) triophanate methyl (Topsin-M) |

|

| Benzothiadiazole | * | acibenzolar-S-methyl (Actigard) |  |

| Dicarboximide | B | iprodione (Rovral) other examples: vinclozolin (Ronilan) chlozoline (Serinal) procymidone (Sumisclex) |

|

| Dithiocarbamate | Y | maneb (Maneb) other examples: zineb (Zineb) ferbam (Carbamate) maneb+Zn (Mancozeb, Dithane) |

|

| DMI-Pyrimidine | C | fenarimol (Rubigan) |  |

| DMI-Triazole | C | myclobutanil (Rally, Nova) other examples: difenoconazole (Score) hexacibazike (Anvil) tebuconazole (Elite) triadimefon (Bayleton) |

|

| Hydroxyanilide | J | fenhexamid (Elevate, Teldor) |  |

| Phenylamide | D | mefenoxam (Metalaxyl, Ridomil) other examples: furalaxyl (Fongarid) |

|

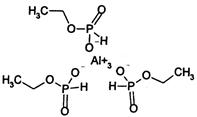

| Phosphonate | Y | fosetyl-aluminum (Aliette) other examples: phosphorus acid |

|

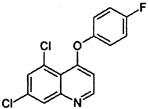

| Phenoxy quinoline | M | quinoxyfen (Legend) |  |

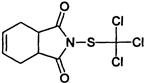

| Phthalimide | Y | captan (Captan, Merpan) other examples: chlorothalonil (Bravo) |

|

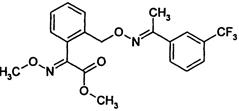

| Strobilurin | K | trifloxystrobin (Flint) other examples: azoxystrobin (Abound, Amistar) kresoxim-methyl (Stroby) pyraclostrobin (Cabrio) |

|

aGrouping of fungicides by their similar mode of action.

Another valuable means of retarding pesticide resistance is to improve application effectiveness. This frequently involves the use of better sprayers (Furness, 2002), combined with improved assessment of spray coverage (Furness 2009). Uniform crop cover is important. Sites where pesticide coverage is inadequate provide conditions favoring resistance development (selectively favoring the most resistant strains). The incorporation of adjuvants (stickers and/or spreaders) into spray mixtures can also improve the likelihood of agent effectiveness (MacGregor et al., 2003). Spreaders facilitate uniform dispersion over plant surfaces (by reducing surface tension that can disrupt distribution), whereas stickers minimize washoff. Regrettably, stickers also limit redistribution of the agent over leaf and fruit surfaces as they enlarge. Adjuvants, due to their action on cuticular wax structure, may also disrupt one of the pre-existing plant defenses against invasion. This is one of the potential problems with all soap/oil mixtures used in pest management.

Dusts, by virtue of their generally smaller mass, tend to spread more uniformly and disperse more effectively into dense canopies than droplets of a wettable agent. Conversely, dusts tend to settle and adhere more poorly to plant surfaces, with more potential for wastage due to wind drift.

Finally, application of other control measures (sanitation, environmental modification, etc.) can further delay the development of pesticide resistance. Because mutation is largely a random event, and therefore partially dependent on population size, the smaller the pest population, the less likely (i.e., more slowly) resistant mutations are to occur and be propagated.

None of these techniques will necessarily prevent the eventual development of resistance, but they can significantly delay its occurrence. The delay will depend on factors such as the widespread use of protective measures, the number of growth cycles per year, existing genetic diversity in the pest or pathogen population, the population size, and the facility with which the pest or pathogen is dispersed.

Traditionally, control agents have been either applied as liquid sprays or dusts. Both have potential problems, such as loss due to drift and washoff, dilution by rain, contamination of ground water, and damage to other organisms. Direct injection of systemically translocated compounds into the trunk would counter many of these factors. The application of metalaxyl against downy mildew by this method is as effective as spraying (Düker and Kubiak, 2009). Its disadvantage is the complexity of injecting individual vines.

Recently, a new and novel class of control agents has entered the market. They work by inducing systemic acquired resistance in the host. Their appearance is encouraging, as they take a distinctly different and ‘natural’ approach to disease and pest management. Examples are β-aminobutrytic acid, which enhances vine resistance to downy mildew (Cohen, 2002; Harm et al., 2011); acibenzolar-S-methyl, which is effective against powdery mildew (Campbell and Latorre, 2004); benzothiadiazol, which limits the development of bunch rot (Iriti et al., 2004) and downy mildew (Harm et al., 2011); and jasmonic acid against Pacific spider mites (Tetranychus pacificus) and phylloxera (Omer et al., 2000). Methyl jasmonic acid is a naturally synthesized, intracellular regulator mediating several diverse defense responses in plants. One of these involves a marked increase in the production of resveratrol and related stilbene phytoalexins (Vezzulli et al., 2007).

Partially limiting the application of some of the procedures noted above are archaic regulations, not only in the region of production, but also in importing countries (e.g., restrictions on pesticide residues). Because these regulations too often vary from year to year, and region to region, the issue is far more complicated than it needs to be and is discouraging to innovation.

Biological Control

Although synthetic and organic pesticides are likely to remain the main arsenal of agents against pests and diseases into the foreseeable future, increasing emphasis is being placed on biological control. Although some insect predators have developed pesticide resistance (Englert and Maixner, 1988), most remain sensitive to insecticides. Thus, to use indigenous insect or mite control agents, pesticide applications must be delayed, minimized, or avoided.

In addition to restricting insecticide use, it is often necessary to maintain a broad diversity of plants in the vicinity (Thomson and Hoffmann, 2009). These supply the variety of alternate hosts, food sources (pollen or nectar), and protection to support a sufficiently high population of control agents. Their population numbers often cycle considerably throughout the seasons (Bernard et al., 2006). Maintenance is also aided by providing interrow crops of flowering plants (Scarratt et al., 2007), but may still not be sufficient for meaningful control (English-Loeb et al., 2003). Thus, the release of commercially reared competitive species may also be required to effectively control pest populations. By establishing themselves on the host, competitors restrict the colonizing potential of the pest species. An example of competitive exclusion is the action of the Willamette spider mite (Eotetranychus willamettei) against the Pacific spider mite (Karban et al., 1997). Various fungi, yeasts, and bacteria can also displace fungal pathogens from their invasion sites.

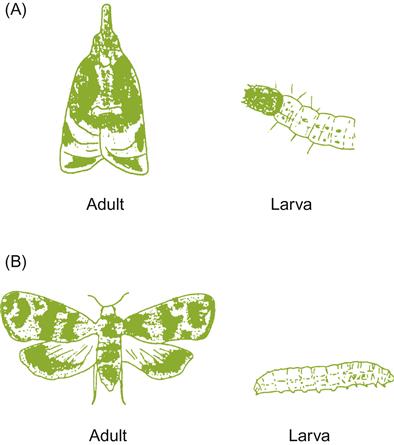

Although insects are susceptible to many bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens, few have shown promise in becoming effective biocontrol agents. Exceptions include the granulosis virus against the western grape leaf skeletonizer (Harrisina brillians) (Stern and Federici, 1990) and Beauveria bassiana (GHA strain) against western flower thrips. The major success story, though, has been Bt toxin, produced by Bacillus thuringiensis. The toxin is active against several lepidopteran pests, such as the omnivorous leafroller (Platynota stultana) and the grape leaffolder (Desmia funeralis).

Bt toxin produces ‘holes’ in the intestinal lining of insects, permitting intestinal bacterial access to the hemolymph (insect ‘blood’). The latter can induce septicemia (Broderick et al., 2006). In some regions, where Bt toxin has been extensively used, signs of resistance have appeared. This may be countered by the use of a subgroup of Bt toxins, in the Cry1Ca complex. They are toxic to lepidopteran insects currently resistant to standard Bt toxin (Avisar et al., 2009). An unsuspected benefit of its widespread use on some crops, such as corn and cotton, has been area-wide suppression of pests in varieties and crops not possessing the Bt toxin (Naranjo, 2011). Nonetheless, the development of resistance, and some expression difficulties in transgenetic varieties (De Rocher et al., 1998), may make the expense of engineering cultivars to produce Bt toxins of short-term value. The same fate might also befall genetically engineering grapevines to possess arthropod resistance with the Galanthus nivalis aggulitin (GNA) gene, or fungal resistance supplied by endochitinase genes from Trichoderma harzianum (Lorito et al., 2001).

Bacterial toxins also possess the potential for controlling fungal pathogens. Examples are syringomycin E and rhamnolipids, produced by Pseudomonas syringae and P. aeruginosa, respectively. Their combination is effective against a range of fungal pathogens (Takemoto et al., 2010).

Pheromones are another agent in the arsenal of biocontrol agents available for insect management. Pheromones are species-specific, airborne hormones produced by insects to locate mates. Thus, they can selectively attract particular insects to pesticide traps, or induce mating disorientation when applied throughout a vineyard. An alternative attractant that could selectively attract pests to traps are grape volatiles. Some of these are used by fertile females to locate oviposition sites on grapes (Tasin et al., 2005).

Another technique that has been used with some success has been the release of large numbers of artificially reared, but sterile, individuals during the mating season. This can so disrupt successful mating as to achieve effective control.

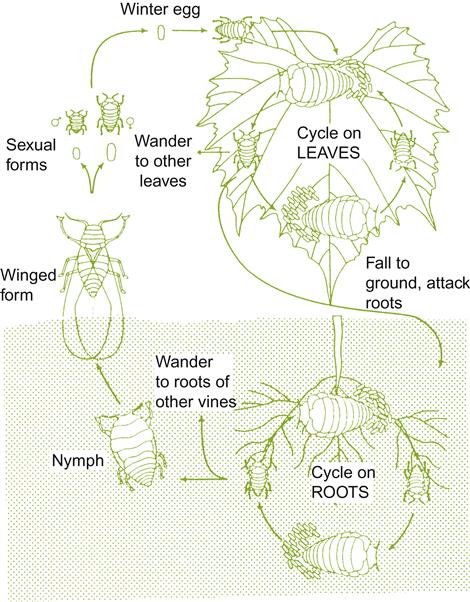

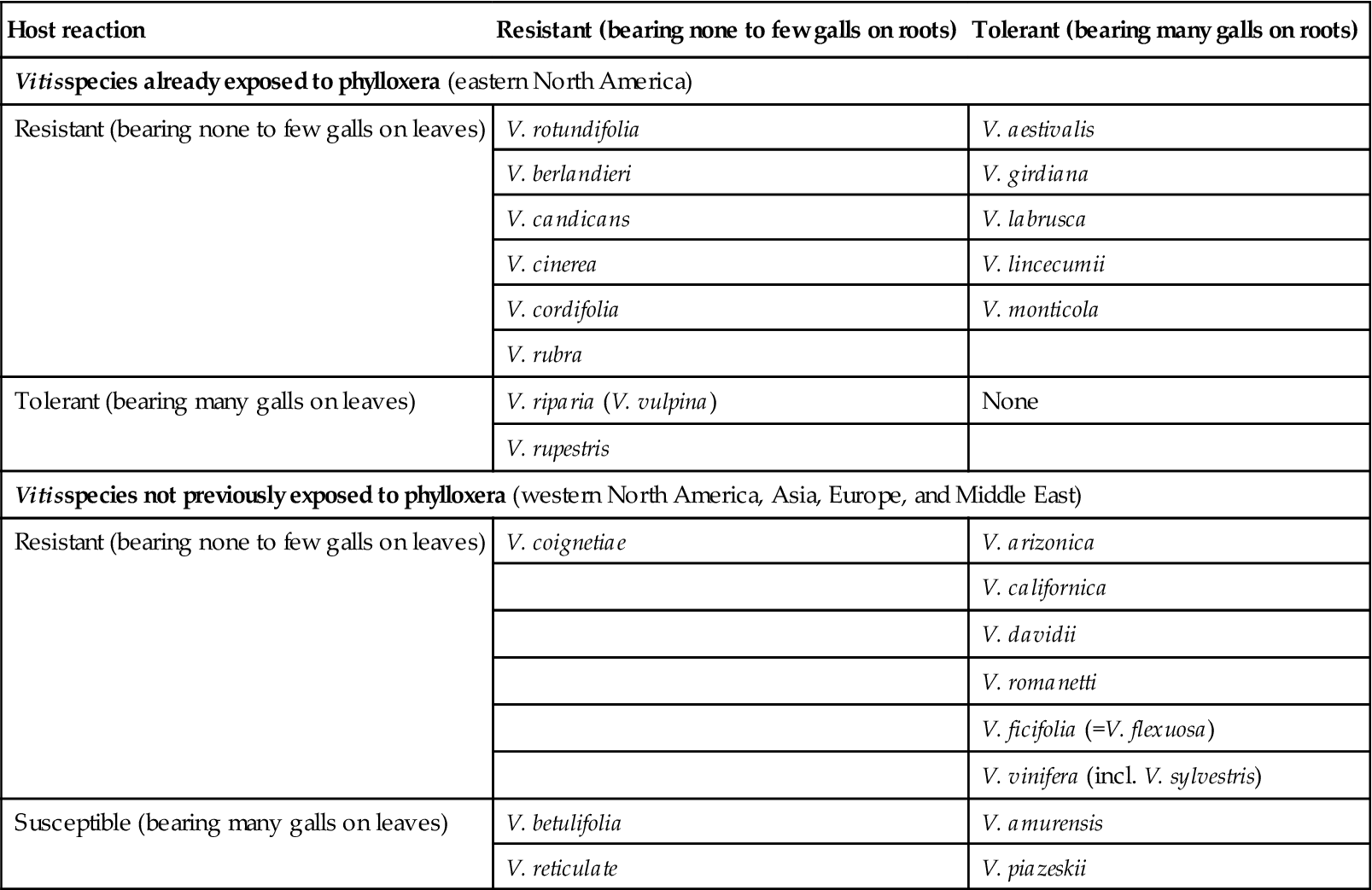

Although the initial cost of grafting to resistant rootstocks is considerable, its beneficial effects are long term. In some cases, grafting may be the only effective means of limiting pest or disease damage. This strategy was first used in the late 1800s to control the phylloxera infestation in Europe. Resistant or tolerant rootstocks are also one the principal means by which the damage of several nematodes, viruses, and soil-based toxicities is limited. Little investigated, however, is the role of grapevine rootstocks in limiting damage by leaf and fruit pathogens (Erb et al., 2009).

The biological control of fungal pathogens is less developed than for arthropod pests. This partially reflects the growth of fungal pathogens within plants, away from exposure to parasites or predators. Nevertheless, inoculation of leaf surfaces with epiphytic microbes may prevent the germination and subsequent penetration of fungal pathogens. The phylloplane flora may inhibit pathogens by competing for organic nutrients required for germination, activating systemic host defenses, inciting mycoparasitism, or provoking antibiosis. A commercially successful example involves Trichoderma harzianum (Trichodex®). It and related agents are especially effective against wood-invading fungi, such as those inducing Eutypa, Esca, and Petri diseases (Hunt, 1999). In contrast, control of Botrytis cinerea is inadequate and requires rotation with conventional fungicides. Of commercial biofungicides, the most effective against B. cinerea appears to be Greygold®. It is a mixture of the filamentous fungus Trichoderma hamatum, the yeast Rhodotorula glutinis, and the bacterium Bacillus megaterium. With powdery mildew, where the mycelium remains predominantly on the plant surface, the mycoparasite Ampelomyces quisqualis (AQ10®)has proven commercially effective (Falk et al., 1995) in some cases.

Another new and fascinating approach being investigated involves endophytes. Endophytes are microbes that grow and multiply asymptomatically within plant tissues. They are typically considered to be symbiotic and beneficial (Rodriguez and Redman, 2008), though some may be latent pathogens (see below). Their presence is detected primarily by the presence of distinctive DNA or fatty acid sequences, or by culturing. Only occasionally can they be observed microscopically within plant tissues, such as with Trichoderma. Endophytes may be localized in the xylem, as with most endophytic bacteria, or the root cortex, as with Trichoderma. Some are also found throughout the plant.

Those found in annual crops can desensitize the host to a variety of environmental stresses, such as salinity, heavy metals, drought, or heat; improve nutrient availability; or enhance disease resistance. The latter can involve activation of various systemic defense mechanisms, or synthesizing antibiotics (Barrow et al., 2008; Shoresh et al., 2010). The ability and diversity of endophytic organisms in reducing susceptibility to a wide range of environmental stresses has led some researchers to advocate their use in lieu of more expensive and controversial genetic breeding procedures (Barrow et al., 2008; Rodriguez et al., 2008). This could be expanded to include adjustment of the rhizoflora in and around roots (Pineda et al., 2010). In this regard, the presence of strains of Pseudomonas spp., carrying the biocontrol genes ph1D and hchAB, has been correlated with improved photosynthesis and grape aroma (Svercel et al., 2010). These strains were isolated from vineyards under long-term viticulture, but not young vineyard soils. This is an interesting example of long-term monoculture appearing to be associated with a beneficial effect.

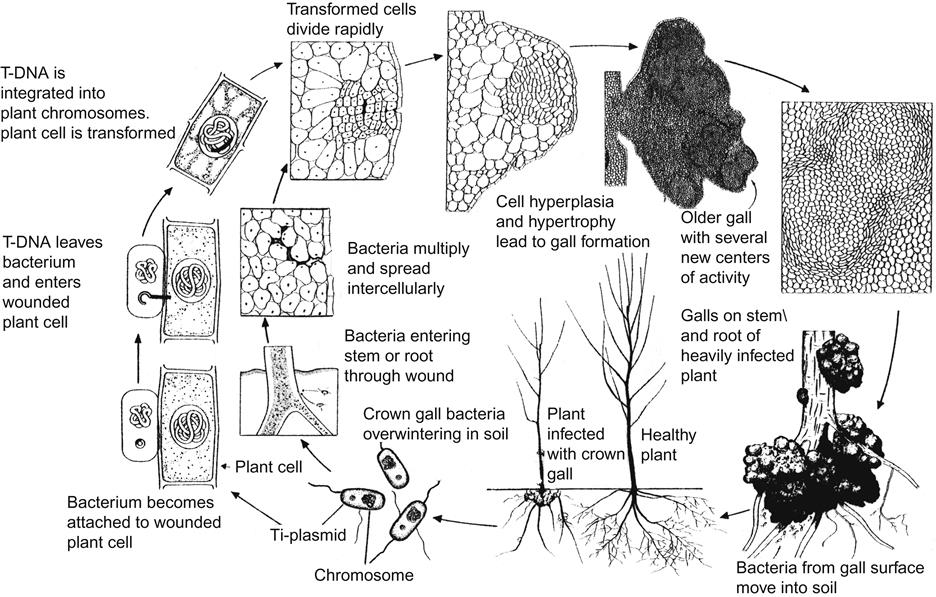

Most bacterial endophytes appear to be neutral to beneficial, with the exception of latent strains of Rhizobium (Agrobacterium) vitis. Most are fastidious, xylem-inhabiting strains of Pseudomonas and Enterobacter. They are distinct from those found in the rhizosphere (Bell et al., 1995). In contrast, the endophyte Burkholderia colonizes both the rhizosphere and internal tissues (Compant et al., 2005). West et al. (2009) found that entrance occurred primarily via pruning wounds. Endophytic strains of Pseudomonas flourescens and Bacillus subtilis have been shown to reduce the size of crown gall in infected plants (Eastwell et al., 2006).

At least some fungal endophytes appear to be latent or non-damaging strains of pathogens, for example Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium spp. (Halleen et al., 2003). In contrast, other fungal endophytes parasitize pathogens, for example Acremonium byssoides and Alternaria alternata on Plasmopara viticola (Burruano et al., 2008; Musetti et al., 2006). Mycorrhizae (specialized semiendophytic fungi that reside primarily outside the plant) can also provide resistance to some pest and disease agents.

One of the more challenging aspects in using biocontrol agents can be the special requirements for storing and application. Because spores and biological toxins often have relatively short half-lives, they need to be kept under cool, dry conditions. In addition, they are often quickly inactivated on exposure to solar UV radiation. Thus, if applied to aerial parts of the vine, they are best sprayed in the evening to extend their effective period. These limitations have retarded grower acceptance (Hofstein et al., 1996).

One of the more intriguing examples of biological control involves cross-protection. Cross-protection is a phenomenon in which virally infected cells are immune to subsequent infection by related or more virulent strains of the virus. Transforming vines with viral coat or dispersal genes can potentially have the same effect (Beachy et al., 1990; Krastanova et al., 1995).

Another component in many biological control schemes is augmentation of the soil’s organic content, either by the application of manure, compost, or a mulch (Hoitink et al., 2002). It has its greatest applicability when dealing with root pests and pathogens. The effect is thought to arise primarily by suppression of the growth and survival of the pathogenic agent, by enhancing the complexity and activity of the soil’s microflora and fauna. This applies especially to the region just around the roots – the rhizosphere. Thus, some of the benefits may also accrue from improved vine nutrition. This could involve better access to soil nutrients (directly or via mycorrhizal association), and, thereby, direct augmentation of host defenses.

Similar in concept is the application of a solution of organic nutrients (e.g., liquid manure). Augmentation of the phylloplane flora may both directly and indirectly suppress the germination or growth of leaf and fruit pathogens (Sackenheim et al., 1994).

Biological control has generally been assumed to be safer to humans and the environment than chemical control. Risk assessment concerning non-target organisms has usually supported this view, but improved techniques may limit the chance of exceptions (Barratt et al., 2010). For example, the fungal biocontrol agents Trichoderma and Gliocladium may provoke allergic respiratory problems and a range of cellular toxic effects in humans, respectively (see Brimmer and Borland, 2003). In other instances, some agents have shown action against beneficial mycorrhizal associations; may disrupt plant metabolism; or, when used prophylactically, induce energy expenditure in activating unnecessary systemic plant defenses. Like all defense mechanisms, they are a drain on plant metabolism.

Environmental Modification

Modifying the microclimate around plants has long been known to potentially minimize disease and pest incidence. By improving the light and air exposure around grapevines, canopy management can increase the toughness and thickness of the epidermis and its cuticular covering. An open canopy structure also facilitates the rapid drying of fruit and foliage surfaces. This reduces the time available for fungal penetration, and may limit or inhibit spore production. Furthermore, an exposed canopy enables more efficient application of pesticides, synthetic or organic.

Berry exposure can be enhanced by applying gibberellic acid. It promotes cluster stem elongation and separation of the fruit (Plate 3.9). Reduced berry compactness also favors production and retention of a typical epicuticular wax coating (Fig. 4.52). However, the effect of gibberellic acid on grape composition is complex, and appears to be cultivar-specific (Teszlák et al., 2005). For example, it can affect grape coloration, phenolic content, and mineral content. In addition, it can increase the formation of o-aminoacetophenone (Christoph et al., 1998; Pour Nikfardjam et al., 2005b), a compound frequently associated with the development of an ‘untypical aged flavor’ in wine. By suppressing the action of IAA oxidase, gibberellic acid can increase auxin content. It appears to favor o-aminoacetophenone synthesis (Pour Nikfardjam et al., 2005a). Less compact clusters also occur in association with minimal pruning. This probably explains part of the reduced incidence of some diseases, notably Botrytis bunch rot, with minimal pruning.

Fruit exposure may also be enhanced by basal leaf removal. The technique has been so successful in reducing dependence on fungicidal sprays that several wineries have written the practice into their contracts with growers (Stapleton et al., 1990). Basal leaf removal also eliminates most first-generation nymphs of the grape leafhopper (Erythroneura elegantula) (Stapleton et al., 1990). This can improve subsequent biological control by Anagrus epos, a parasitic wasp. It provides more time for wasp populations to increase, and spread to grapevines from overwintering sites on wild blackberries and other plants.

Balanced plant nutrition generally favors disease and pest resistance, by promoting optimal development of anatomical and physiological defenses. Nutrient excess or deficiency can have the inverse effect. For example, high nitrogen levels suppress the synthesis of a major group of grape antifungal compounds, the phytoalexins (Bavaresco and Eibach, 1987). They also favor cell elongation, associated with weaker walls, as well as promoting vigorous growth, dense foliage, and the development of high inner-canopy humidity.

With adequate irrigation, the consequences of nematode root damage are often mitigated. Adequate irrigation also avoids the serious consequences of water deficit. Conversely, excessive irrigation can favor disease development by promoting luxurious canopy development and increasing berry-cluster compactness. This is particularly important for cultivars that inherently produce compact clusters, notably Zinfandel and Chenin blanc.

Weed control usually reduces disease incidence. This may result from the removal of alternate hosts, on which pests and disease-causing agents may survive and propagate. For example, dandelions and plantain are often carriers of tomato and tobacco ringspot viruses, and Bermuda grass is a reservoir for sharpshooter leafhoppers – the primary vectors of Pierce’s disease. Conversely, cover crops are generally viewed as beneficial, supporting populations of biocontrol agents. Nonetheless, if not well chosen they can also be carriers of vine pests and disease.

Soil tillage can occasionally be beneficial in disease control. For example, the burial of Botrytis cinerea, sclerotia, and infected vine tissue promotes their degradation in the soil. In addition, the emergence of adult grape root borers (Vitacea polistiformis) is restricted by burial of the pupae (All et al., 1985).

Although environmental modification can limit the severity of some pathogens, it can enhance other problems. For example, soil acidification, used in the control of Texas root rot (Phymatotrichum omnivorum), has increased the incidence of phosphorus deficiency in Arizona vineyards (Dutt et al., 1986). The elimination of weeds may inadvertently limit the effectiveness of some forms of pest biological control (removing survival sites for pest predators and parasites). The carrier of one pest may be the reservoir of predators for another.

Genetic Control

Improved disease resistance is one of the major goals of grapevine breeding. It was first seriously investigated as an alternative to grafting in phylloxera control. Subsequently, breeding has focused primarily on developing rootstocks possessing improved drought, salt, lime, virus, and nematode resistance. Work has also progressed, but more slowly, on developing new scions, with improved pest and disease resistance. Regrettably, consumer (and especially critic) resistance to new varieties has limited acceptance. However, at the lower end of the market, new varieties often have a distinct advantage. Their production costs are reduced and their yield higher. Resistant varieties are probably most appropriate for ‘organic’ viticulture, where synthetic control agents are proscribed and varietal origin may have less marketing value.

Although valuable sources of disease resistance may exist in remnants of the original population of wild vinifera vines, most potentially useful resistance genes occur in other Vitis species. Regrettably, the EU has passed legislation against the use of interspecies crosses, as well as genetically modified crops. In so doing, they have cut themselves off from almost all sources of disease resistance. Genetic engineering has the best chance of enhancing cultivar disease resistance, without modifying enologically essential varietal traits.

It is only with rootstocks that traditional breeding has much potential to improve vine resistance to root and/or shoot diseases. This is especially the case with the recently discovered potential of roots to influence defense against foliar diseases and pests (Erb et al., 2009).

In addition to pre-existing structural and chemical defenses, plants possess two broad response-based defense mechanisms against pathogen attack. The first, often referred to as non-host resistance, appears to depend on transmembrane receptors recognizing penetration. Activating factors include constituents of most fungal cell walls (chitin), peptides typically found on bacterial flagella, and mechanical pressure (as applied during fungal penetration). Plant response activates cytological and histochemical responses that may prevent successful penetration and infection (Dry et al., 2010). Jasmonic acid and ethylene-dependent signaling pathways are though to be involved, but are not necessarily crucial to effectiveness (Glazebrook, 2005; Humphry et al., 2006).

Pathogens that overcome these primary defenses may prompt a second line of defense. This depends on specialized receptor (R) proteins. They induce a cascade of reactions involving hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide. When rapid and intense, localized tissue death results in what is termed a hypersensitive response. If effective, it kills the invading pathogen (Tameling and Takken, 2008). As part of the cascade, a salicylic acid-dependent signaling pathway is activated (Jung et al., 2009). It primes plant defenses throughout the plant, a phenomenon termed systemic acquired resistance (Gurr and Rushton, 2005a,b). Unfortunately, excessively and unnecessary activation of the response can ‘stress’ the plant, compromising growth.

Traditionally, enhanced disease resistance has involved the resistance (R) genes noted above. They act in a dominant manner, donating immunity to the pathogen; that is, until the pathogen mutates to circumvent the resistance. Thus, the breeder and pathogen are often interlocked in a cat-and-mouse game of adding new R gene alleles, and the pathogen mutating to negate their effects. Nonetheless, R-type genes from V. rotundifolia, such as Run1 and Rvp1, appear to exhibit durability (Dry et al., 2010). Run1 donates resistance to powdery mildew. Ren1 from Vitis vinifera has a similar effect.

An alternative, and potentially longer-term approach, may involve adjustment to components of non-host resistance – the general immunity of plants to the vast majority of pathogens. One element of this phenomenon, in relation to powdery mildew, is the absence of specific MLO proteins. Grapevines possess up to 17 variants in the MLO gene family (Winterhagen et al., 2008). Homozygosity for recessive (mlo) alleles results in unsuccessful penetration by the more than 100 species of powdery mildew, except Uncinula necator (Humphry et al., 2006). Which of these variants are dominant, presumably generating susceptibility to U. necator, is under investigation (Dry et al., 2010). Inactivation of those variants might donate immunity to U. necator, equivalent to that which they possess against other powdery mildew species.

Resistance to some pathogens is also associated with the production of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins. Examples are the chitinases, associated with haze production in wines. Enhancing their earlier activation or overexpression might improve disease resistance. This has been shown to enhance disease resistance in several transgenic crops. Enhancing baseline phytoalexin production is another potential approach.

Another option, using genetic engineering, but not involving resistance genes per se, would be the incorporation of genes coding for one of several viral genes. As noted earlier, these can induce immunity (cross-protection) against the source virus.

In most instances, complete resistance (immunity) to infection is preferred. However, even slowing the rate of disease spread (tolerance) may provide adequate protection in most years, especially where several cycles of pathogen/pest reproduction are required for the expression of severe damage. Regrettably, tolerance to one pest can occasionally favor infection by another (e.g., tolerance to Xiphinema index increases the likelihood of grapevine fanleaf virus transmission). In addition, tolerance to a systemic pathogen (by masking presence) favors the likelihood of its spread by grafting or other forms of mechanical transmission.

The increasing availability of molecular markers, such as SSRs, has begun to simplify mapping the location of resistance genes (Fischer et al., 2004; Di Gaspero et al., 2007). This potentially facilitates their isolation, amplification, and subsequent insertion via transduction. In addition, these markers can be used as indicators of the presence of resistance genes in the progeny – in a process termed marker-assisted breeding (Eibach et al., 2007). The similarity of many of these genes in other plants also aids identification of potentially useful genes in grapevines. Locating a useful allele in one cultivar or related species would theoretically permit its transfer via genetic engineering, without crossing broad generic boundaries. The latter is a frequent complaint leveled against most GM plants. The difference is termed cisgenic vs. transgenic engineering (Schouten et al., 2006). In addition, it would not disrupt existing cultivar traits. Dhekney et al. (2011) have recently isolated the VVTL-1 gene from Chardonnay, modified it to become constitutive, and reinserted it into Thompson Seedless. It expresses significantly enhanced disease resistance to several serious fungal grapevine pathogens.

Simply inserting the protein-coding component of a resistance gene is not necessarily adequate for activity. It requires the insertion of appropriate promoter, terminator, and controller regions for proper function. Thankfully, most resistance loci possess several related R genes, as well as control regions (see Dry et al., 2010). This may enhance durable resistance, especially necessary with grapevines possessing prolonged vineyard ‘life spans.’

Finally, a caveat for all such research is the possibility that improving a particular property may unexpectedly negatively impact another. Thus, as always, field trials over several years, and in diverse locations with different climates, are necessary to determine whether the benefits are both sustainable and outweigh any potential disadvantages. All this adds expense, something governments and agricultural industries seem increasingly loath to do, at a time when it is increasingly urgent to do so.

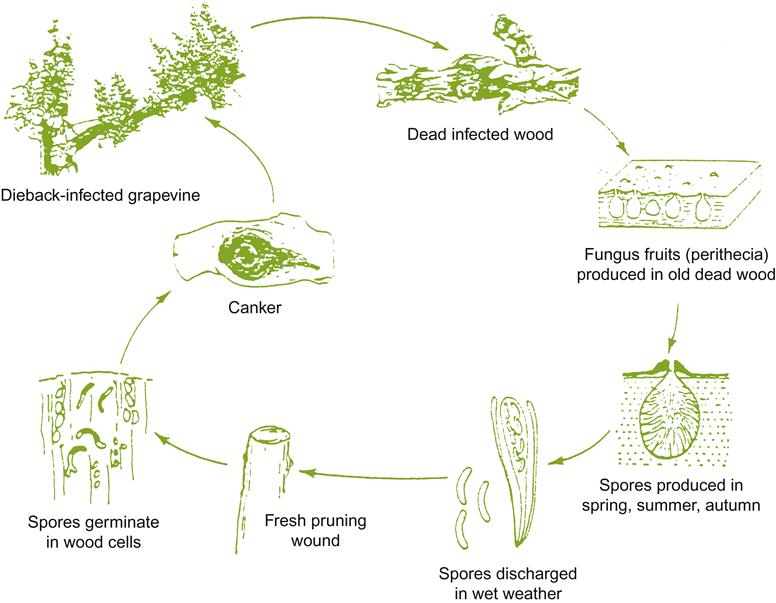

Eradication and Sanitation

In most situations, the eradication of established pathogens is impossible, due to their survival on alternative hosts, such as weeds or native plants. Eradication has greater potential for success with newly introduced, exotic pathogens. In this situation, it is normal practice to destroy all the vines in affected areas. Clearly, this induces extreme hardship on the owners involved, and requires at least financial compensation from the government. Consequently, studies are in progress to assess the feasability of reducing the impact of eradication. For above ground pathogens, removing the vine down to the crown is being investigated. The production of new shoots from long dormant buds permits the more rapid reestablishment of the vineyard. The upper parts of the vines are either burnt or buried, with a straw layer applied to aid in the decomposition of any residual infected material (Sosnowski et al., 2009).

Seed propagation is frequently used to eliminate (eradicate) host-specific systemic pathogens from a crop. However, this is inapplicable with grapevines – it would disrupt the combination of genetic traits that makes each cultivar unique (see Chapter 2). Thus, except where disease-free individuals can be found, the elimination of systemic pathogens from cultivars must involve thermotherapy, meristem culture, or a combination of both.

Thermotherapy can vary from placing young rooted shoots at 35–38°C for 2–3 months to dormant canes being given higher temperature treatment, but for shorter periods. The treatment is effective against several viruses, such as the grapevine fanleaf, tomato ringspot, and fleck viruses, as well as the leafroll agent (typically associated with closteroviruses). Hot-water immersion is also appropriate and preferable for other pathogens – the specifics depending on the pathogen and it location, i.e., external vs. internal. It can be effective in eliminating pathogens such as the bacteria Xylella fastidiosa, Xanthomonas ampelina, and Rhizobium (Agrobacterium) vitis; the phytoplasmas associated with grapevine yellows diseases (e.g., flavescence dorée); the fungus Phytophthora cinnamoni and those causing Petri disease; and root nematodes, such as Xiphinema index and Melidoyne spp. Procedures and recommended precautions for hot-water treatment are given in Hamilton (1997), Waite et al. (2001), and Waite (2005).

Because hot-water treatment stresses vine tissues, it is recommended that treated cuttings be protected from adverse weather conditions, usually in a greenhouse or equivalent, for several months prior to planting out in field nurseries. Following treatment, the cutting may be dipped in a combination of biocontrol agents to reduce the incidence of reinfection (Graham 2007). Treating vines infected by several systemic pathogens may require a combination of procedures.

The use of thermotherapy and meristem culture in the preparation of nursery stock is often of concern to growers. The treatment can modify the morphological and physiological traits of the treated vines. Expression of juvenile traits, such as spiral phyllotaxy, reduction in tendril production, more jagged and pubescent leaves, stem coloration by anthocyanins, and reduced fertility are fairly typical. These usually disappear, though, as individual vines mature or are propagated repeatedly (Mullins, 1990; Grenan, 1994).

For systemic pathogens that are not eliminated by heat treatment, but do not invade meristematic tissues, elimination is often possible by culturing meristematic sections. Direct propagation from these small fragments has often been used to eliminate viruses, such as grapevine fanleaf virus (GFLV) and grapevine leafroll-associated virus-1 (GLRaV-1); the virus-like agents of stem pitting, corky bark, and leafroll; the viroid of yellow speckle; and the bacterium Rhizobium (Agrobacterium) vitis.

Once freed of systemic pathogens, vines usually remain disease-free, if grafted to disease-free rootstock and planted in pathogen-free environments. Most serious grapevine viruses are not insect transmitted, but resistant rootstock is advisable where soil is infested with root-feeding nematodes. Alternatives are leaving the land fallow for up to 10 years, or fumigating the soil.

Sanitation and hygiene may not eliminate disease or pest problems, but they usually reduce their severity by destroying resting stages or by removing survival sites.

Quarantine

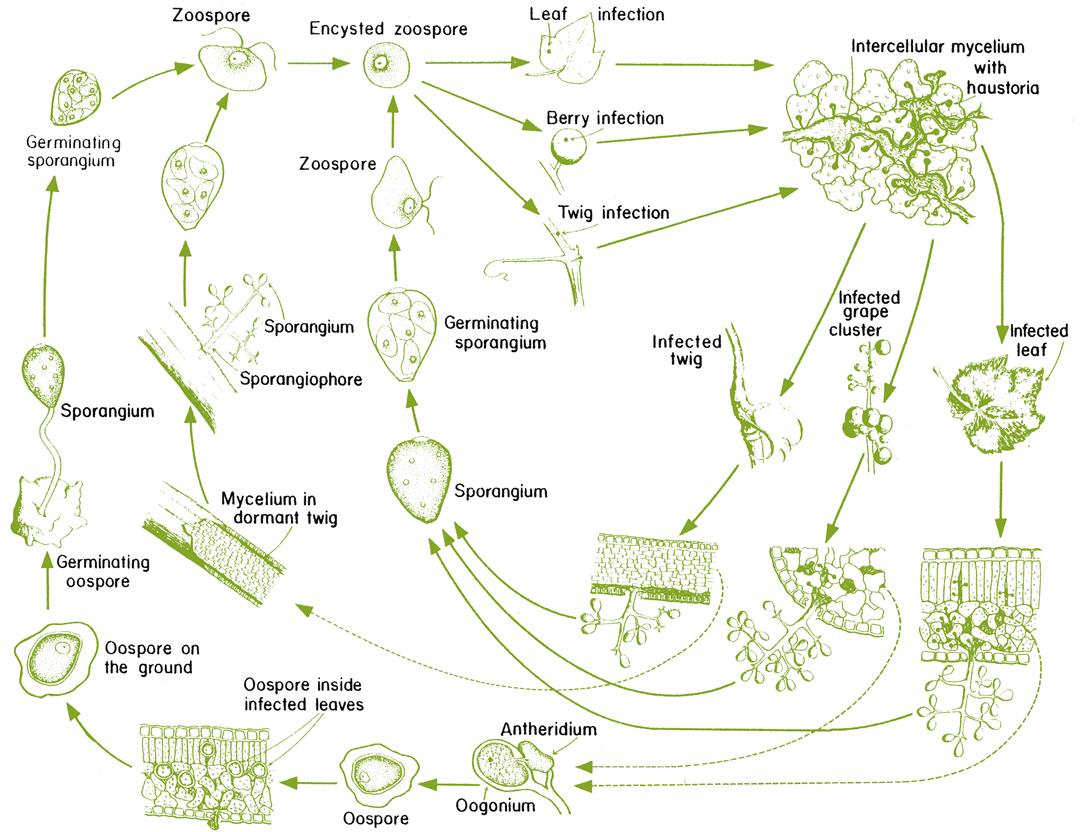

Most, if not all, wine-producing countries possess laws regulating the importation of grapevines. Some of the best examples illustrating the need for quarantine laws are those involving grapevine pathogens. Two of the major grapevine diseases in Europe (downy and powdery mildew) were imported unknowingly from North America in the nineteenth century. The phylloxera root louse was also accidentally introduced, probably on rooted cuttings. Several viral and virus-like agents are now widespread in all major wine-growing regions. They are thought to have been spread, surreptitiously, through the importation of asymptomatic, but infected, rootstocks or scions. Examples are the agents causing leafroll, corky bark, and stem pitting.

Thankfully, some other potentially devastating diseases have as yet to become widespread. For example, Pierce’s disease is still largely confined to southeastern North America and Central America. However, it is causing severe problems in parts of California, due to spread by the glassy-winged sharpshooter. Although phylloxera is present in most wine-producing regions, it has not spread throughout all parts of the countries in which it occurs. Thus, limiting grapevine movement within regions can still have a significant impact on the spread of those pathogens with limited natural means of dispersal. Disinfection of footwear and machinery is another component of limiting spread, both within and between vineyards.

Because it is difficult to detect the presence of some pests and disease-causing agents, only dormant canes are permitted entrance into most jurisdictions. This impedes the introduction of root and foliar pathogens. Nonetheless, fungal spores, insect eggs, and other minute dispersal agents may go undetected. Consequently, imported canes are typically quarantined for several years, until they are determined to be free, or freed, of known pathogens. Most pests, as well as fungal and bacterial pathogens, express their presence during the detention period. For latent viruses and viroids, detection usually requires grafting or mechanical transmission to indicator plants. Detection of systemic pathogens, through their transmission to sensitive (indicator) plants, is termed indexing. Less time-consuming analytic techniques, such as ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) (Clark and Adams, 1977), cDNA (Koenig et al., 1988), or PCR probes (Constable et al., 2012) can both facilitate and speed the detection of systemic pathogens. Nonetheless, because no technique is 100% perfect all the time, repeat sampling is advisable. For example, it may take up to a year after infection for some viruses to become reliably detectable. Even with these caveats, modern assessment techniques permit the earlier release of imported stock.

Unfortunately, quarantine is not only expensive, but can also irritatingly delay importer access to new material. A possible solution is the development of encapsulated somatic embryos (Das et al., 2006). Being produced under sterile conditions, and from healthy tissue, they could be shipped directly to propagation facilities in the host country. Theoretically, this should completely avoid the potential for incidental pathogen introduction along with cuttings.

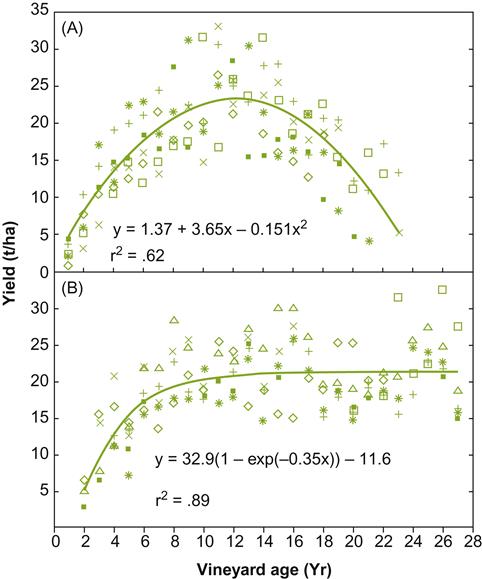

Consequences of Pathogenesis for Fruit Quality

The negative influence of pests and diseases is obvious in symptoms such as blighting, distortion, shriveling, decay, and tissue destruction. More subtle effects involve vine vigor, berry size, and fruit ripening. Sequelae such as reduced root growth, poor grafting success, decreased photosynthesis, and increased incidence of bird damage on weak vines (Schroth et al., 1988) are more easily missed. In some instances, detection of infection is impeded by minimal symptoms or the absence of uninfected individuals for comparison. This was initially the case with several viral and viroid diseases.

Most pest and disease research is concerned with understanding the pathogenic state and how its effects can be minimized. However, in making practical decisions on disease control, it is important to know the effects of disease not only on vine health and yield, but also on grape and winemaking quality.

All pests and disease agents disrupt vine physiology to some degree and, therefore, potentially influence fruit yield and quality. For example, the sensory quality of wine was detectably reduced from vineyards possessing as little as 5% Esca-affected vines (Lorrain et al., 2012). However, agents that attack berries clearly have the greatest impact on fruit quality. These include three of the major fungal grapevine pathogens – Botrytis cinerea, Plasmopara viticola, and Uncinula necator. Grapevine viruses and viroids, being systemic, can both directly and indirectly affect berry characteristics. For example, leafroll-associated viruses reduce grape °Brix, increase titratable acidity, and delay ripening. Insect pests can cause fruit discoloration and malformation, as well as create lesions favoring invasion by pathogens and saprophytes as well as secondary pests.

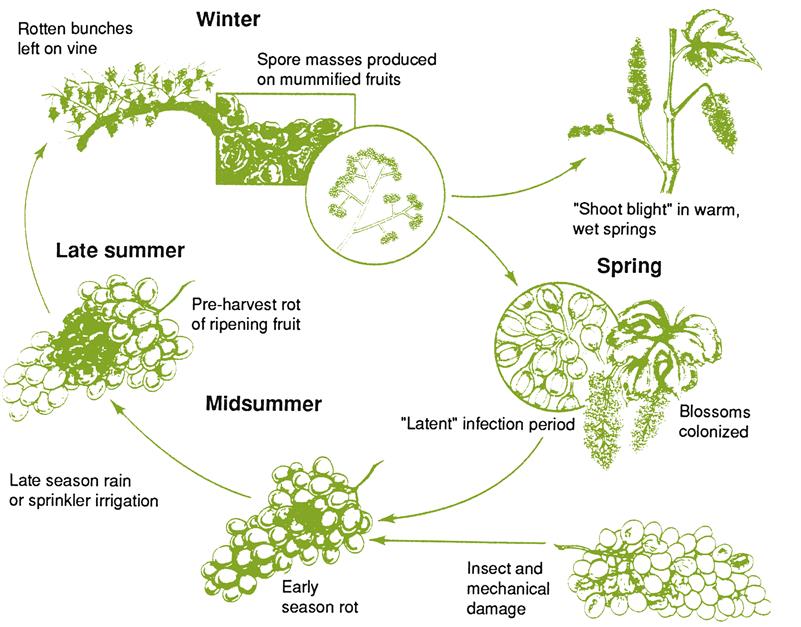

Of fruit-infecting fungi, the effects of Botrytis cinerea have been the most extensively studied. Under special environmental conditions, infection produces a ‘noble’ rot, yielding superb wines (see Chapter 9). Typically, however, the fungus produces a bunch (ignoble) rot. Subsequent invasion by acetic acid bacteria probably explains the high levels of fixed and volatile acidity in the fruit.

Under moist conditions, secondary invaders, such as Penicillium and Aspergillus, contribute additional off-flavors, such as geosmin, 2-methylisoborneol, 1-octen-3-one, and 1-octen-3-ol (La Guerche et al., 2006). These saprophytes can also produce mycotoxins. Examples are isofumigaclavine, festuclavine, and roquefortine, produced by Penicillium spp. (Moller et al., 1997); ochratoxin A, primarily derived from Aspergillus carbonarius (O’Brien and Dietrich, 2005); fumonisins, synthesized by Aspergillus niger (Mogensen et al., 2010); and trichothecenes, generated by Trichothecium roseum (Schwenk et al., 1989). In sufficient amounts, they can be mammalian cytotoxins and carcinogens. The presence of secondary saprophytes, such as Mucor species, can disrupt the activity of lactic acid bacteria during malolactic fermentation (San Romáo and Silva Alemáo, 1986). B. cinerea produce several phytotoxins, but none known to affect humans (Krogh and Carlton, 1982). Their presence may be the source of the disrupted yeast growth noted by Blakeman (1980).

In addition to increased fixed and volatile acidity, fungi associated with bunch rots reduce nitrogen and sugar contents. This can create difficulties during fermentation. Large accumulations of β-glucans, synthesized by B. cinerea, can create clarification problems. More than a minimal level of bunch rot generally excludes their use in the making of red wines, if for no other reason than the oxidation of anthocyanins and other grape phenolics by fungal laccases. Cladosporium bunch rot also reduces the quality (color and flavor) of wines produced from affected red grapes (Briceño et al., 2009). Botrytis infection can also increase problems associated with protein haze (Girbau et al., 2004). This appears to result from the enhanced production of thaumatin-like (PR) proteins.

The effects of sour rot on wine quality has been studied by Barata et al. (2008). Sour rot is the result of microbial invasion of the fruit by a diverse set of agents, notably following feeding by insects and birds. Other than the origin of a sweet, honey-like note, generated by marked increases in ethyl phenylacetate and phenylacetic acid, and reduction in fatty acid and their esters, it is uncertain what specific feature(s) trigger consumer rejection.

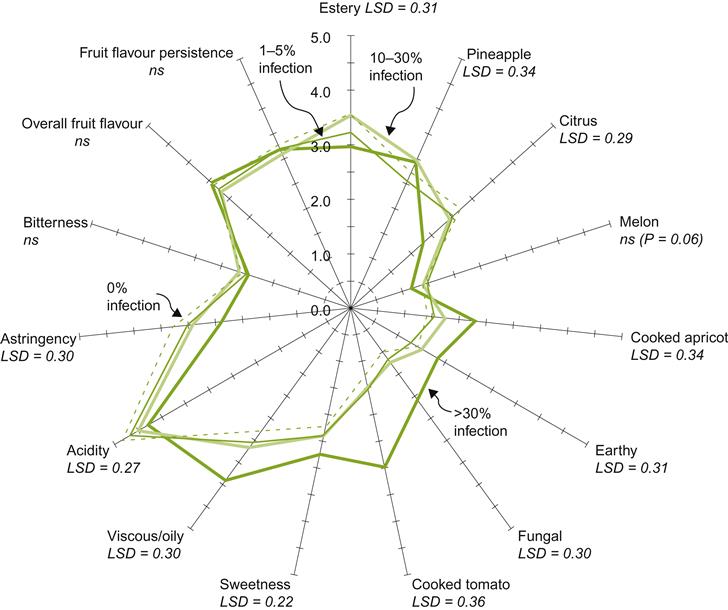

Little information is available on the direct consequences of most pathogens on grape and wine quality. One exception is the higher pH and phenol contents of wine produced from fruit infected by powdery mildew. They may donate a bitterish attribute (Ough and Berg, 1979), or other flavor modifications (Fig. 4.53). Reduced anthocyanin content appears to be due to physiologic disruption during grape development (Amati et al., 1996). The flavor consequences of infection are augmented with increased skin contact, prior to or during fermentation. This may involve the conversion of several ketones to 3-octanone and (Z)-5-octen-3-one (Darriet et al., 2002). Flavor distortion has been noted in wine made from grapes with as little as 1–5% infection (Stummer et al., 2005), although not consistently. This anomaly may be related to the degree to which diseased grapes are colonized by secondary saprophytes. Yield, Brix, and anthocyanin synthesis in red grapes are reduced as a consequence of infection (Amati et al., 1996). Browning is common, but can be partially offset by the bleaching action of sulfur dioxide in white wines. Infected white grapes also possess higher concentrations of haze-producing proteins. Fermentation may also take up to twice as long to complete (Ewart et al., 1993).

In flavescence dorée, the production of a dense, bitter pulp makes commercial wine production from affected fruit virtually impossible. Of virus and virus-like infections, leafroll has been the most investigated relative to grape and winemaking quality. Potassium transport is affected and berry titratable acidity decreased. This typically generates wines of higher pH and poorer color. Sugar accumulation in the berries is usually decreased, due to suppressed transport from the leaves. Ripening is often delayed. GLRaV-1 and rugose wood viruses shift the relative proportion of phenolics from seeds and skins, but do not appear to affect grape anthocyanin or total phenolic contents (Tomažič et al., 2003). In contrast, the level of the more stable (oxidation-resistant) anthocyanins is reduced in Nebbiolo grapes, in association with joint infection with GFV and GFkV viruses (Santini et al., 2011).

The physiological disorder, bunch-stem necrosis (dessèchement de la rafle, Stiellähme), causes grape shriveling and fruit fall around and after véraison. Wines produced from grapevines so affected often lack balance, are high in acidity, and low in ethanol, as well as several higher alcohols and esters (Ureta et al., 1982). Susceptibility to this disorder most likely has a genetic basis, as some cultivars (i.e., Silvaner and members of the Pinot family) are particularly resistant to its development.

The effects of disease on aroma have seldom been reported. Exceptions are the reduced varietal character of grapes infected by B. cinerea, or their modification by the presence of the ajinashika virus (Yamakawa and Moriya, 1983).

Although not a direct consequence of pathogenesis, the application of protective chemicals may indirectly affect wine quality. For example, the copper in Bordeaux mixture can compromise the quality of Sauvignon blanc wines and related cultivars. It can reduce the concentration of important varietal aroma compounds, such as 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one. This effect can be reduced by prolonged maceration (Hatzidimitriou et al., 1996), or avoiding the use of Bordeaux mixture (Darriet et al., 2001). Fungal and pest control agents, as well as herbicides, may also have phytotoxic effects on the vine. These can vary from direct visible damage, as caused by sulfur at high temperatures, to more subtle changes, such as reduced sugar accumulation in berries (Hatzidimitriou et al., 1996), and disruptions to photosynthesis (Saladin et al., 2003). Even more indirect influences may affect the soil flora and fauna. For example, long-term use of Bordeaux mixture has resulted in the substantial accumulation of copper in vineyards worldwide – being in the range of 130–1280 mg/kg in European vineyards (Wightwick et al., 2010). This partially results from copper’s binding with organic matter in the soil, but mainly from the formation of copper and iron oxyhydroxides; the latter bind tightly to the soil’s clay fraction. The highest concentrations tend to be found in the upper layers of the soil. An indirect effect is suppression of the soil’s microbial activity, and an indirect augmentation of its organic content (Parat et al., 2002).

Examples of Grapevine Diseases and Pests

Grapevines can be attacked by a wide diversity of biologic agents. There is insufficient space in this book to deal with all these maladies. Thus, only a few of the more important and/or representative examples of the major categories of grapevine disorders are provided. Detailed discussions of grapevine maladies for specific countries can be found in specialized works such as Pearson and Goheen (1988) and Flaherty et al. (1992) (North America), Galet (1991) and Larcher et al. (1985) (Europe), and Coombe and Dry (1992) and Nicholas et al. (1994) (Australia).

Fungal Pathogens

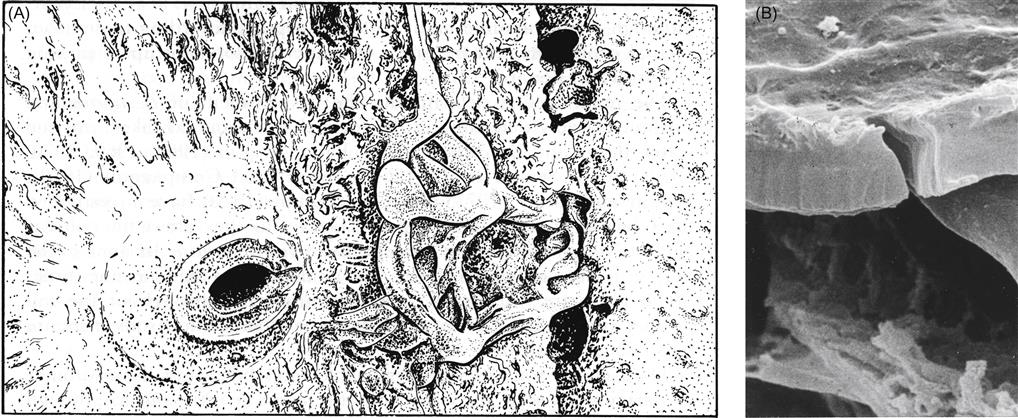

With few exceptions, fungal pathogens grow as long, thin, branching, microscopic filaments called hyphae, and collectively termed mycelia. Most fungi produce cell-wall ingrowths along the hyphae termed septa. The ingrowths are usually incomplete and leave a central opening through which nutrients, cytoplasm, and cell organelles may pass. Thus, fungi possess the potential to adjust the number and proportion of nuclei and various organelles within the organism as they grow. This gives fungi a degree of genetic flexibility unknown in other organisms. The filamentous growth habit also provides them with the ability to physically puncture plant-cell walls. This property, combined with their degradative powers (by secreting hydrolytic enzymes) and prodigious spore production, helps explain why fungi are the predominant disease-causing agents of plants.

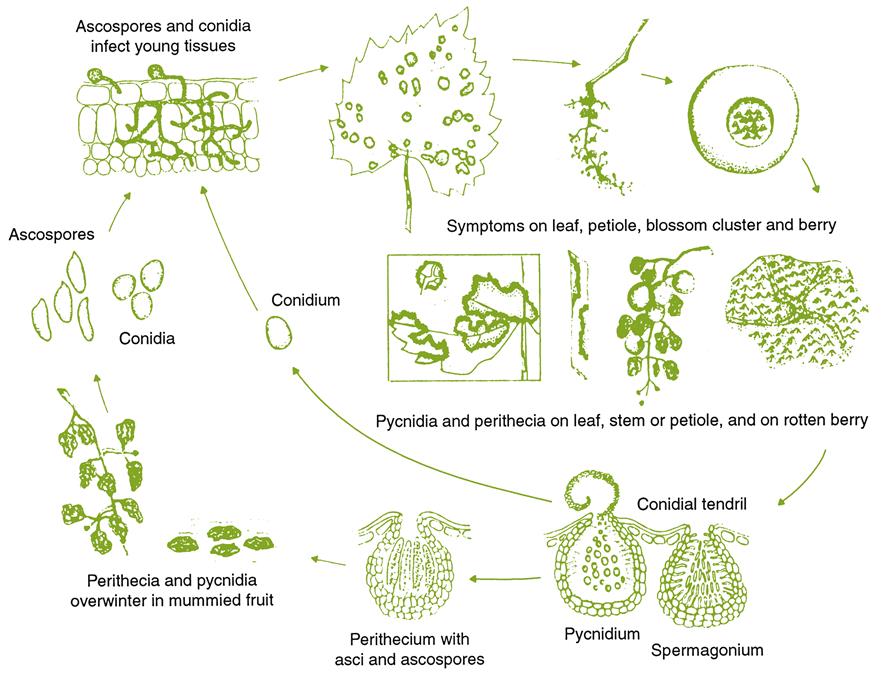

Most parasitic fungi reproduce primarily by forming asexually generated spores, commonly termed conidia. They may or may not be produced in an enclosing structure. They may also produce spores generated by meiosis, usually in the spring. The latter are named relative to their taxonomic grouping (ascospores – Ascomycota, basidiospores – Basidiomycota, and oospores – Oomycota). Fungi that primarily reproduce without a sexual mode are variously termed hyphomycetes (members of the Fungi Imperfecti).

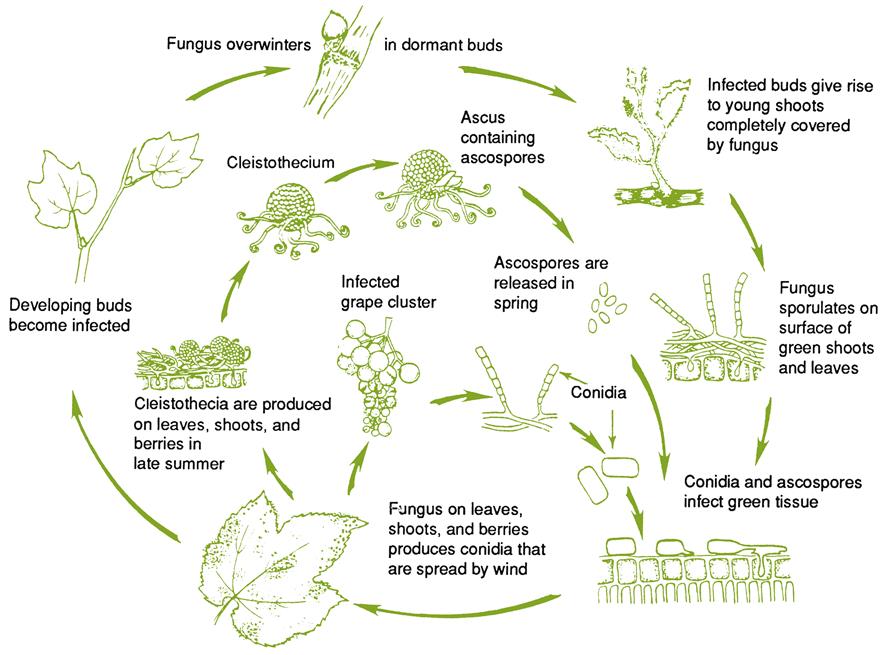

Botrytis Bunch Rot

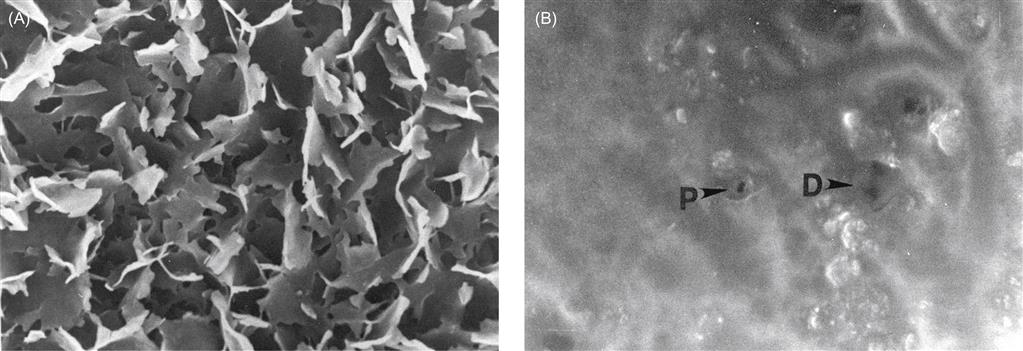

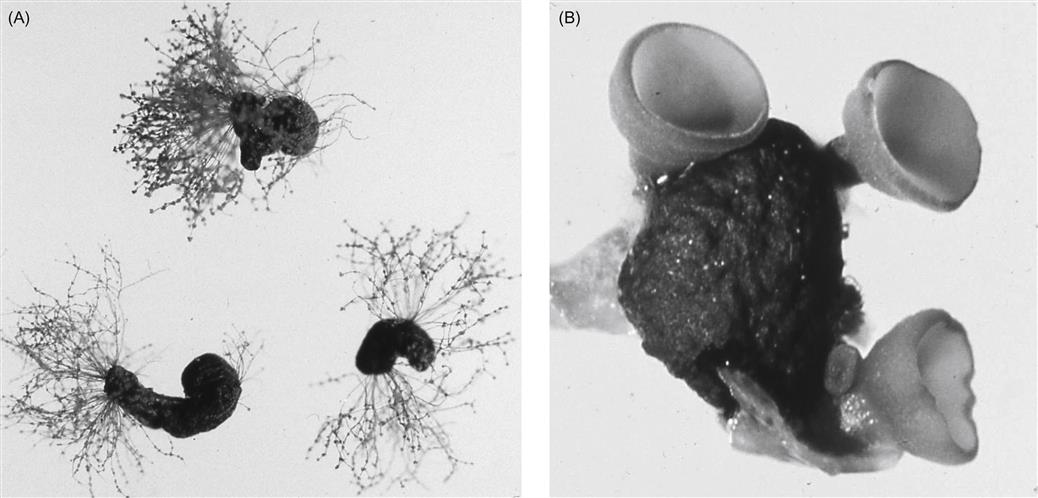

Several hyphomycetes can induce bunch rot, either alone or together. However, the principal causal agent is Botrytis cinerea. The pathogen appears to exist as two co-inhabiting subpopulations (Fournier et al., 2005), with Group II divided into two divisions based on features such as fungicide resistance, virulence, compatibility, and transposable elements. All forms infect grapevines and may occur sympatrically, but tend to possess different frequencies of fungicide resistance. Unlike many grape pathogens, B. cinerea is a necrotroph – attacking primarily damaged or senescent tissues, and provoking tissue necrosis in advance of penetration. In addition, unlike most other Botrytis species (Staats et al., 2005) B. cinerea is a nonspecialized pathogen, infecting a wide diversity of plants and tissues. As a consequence, spores infecting grapes may arise from a wide range of host species, within and around vineyards. Nonetheless, most early infections develop from spores produced on overwintered mycelia within the vineyard (Jacometti et al., 2007) (Fig. 4.54). In addition, another source of spores may arise from black, multicellular, resting structures called sclerotia (Fig. 4.55A). In both instances, these are usually conidia (asexual spores). Occasionally, ascospores may be produced from the sclerotia. They are generated in multicellular fructifications called apothecia (Fig. 4.55B).

Pathogenesis results from the combination of a wide range of toxins and enzymes. The first to be studied extensively were pectinases. They have a macerating action, by degrading the pectins that hold plant cells together. Their action is likely aided by the production of oxalic acid. By lowering the pH of intercellular fluids, it would favor the activity of pectinases. Pectinases may also initiate disruption of the cell membrane. This action, combined with the release of phytotoxic chemicals (such as secobotrytriendiol [Durán-Patrón et al., 2000], botcinolide, and botrydial), necrosis and ethylene-inducing proteins (NEP1 and NEP2) (Staats et al., 2007), as well as laccase, probably induces tissue necrosis. The potent polyphenol oxidase activity of laccase can generate a wide range of toxic quinones. The release of cutinases and lipases undoubtedly aids the penetration of plant surfaces by B. cinerea.