Grape Species and Varieties

The distinctive structural and genetic nature of genus Vitis is covered, followed by a discussion of its geographic origin and distribution, notably V. vinifera – the wine grape. Subsequently, the domestication of V. vinifera is explored, as well as modern views on the likely origins of grape cultivars, their selection, and spread. This includes the development of rootstocks, demanded as a consequence of the European invasion by phylloxera. Standard as well as modern breeding techniques are noted, including clonal selection. The chapter ends with a discourse on the methods used in cultivar identification, origin studies, and the distinctive attributes of some of the more significant cultivars.

Keywords

Vitis; Vitis vinifera; wine grapes; grape cultivars; cultivar origin; rootstocks; grape breeding; cultivar identification

Introduction

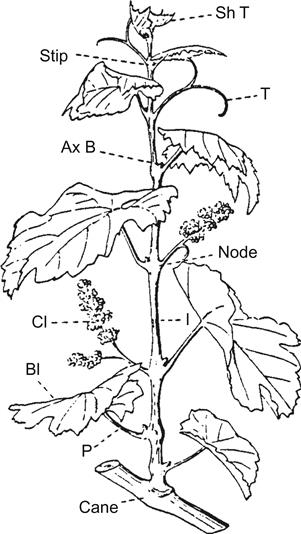

Grapevines are classified in the genus Vitis, within the Vitaceae. Other well-known members of the family are the Boston Ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata) and Virginia Creeper (P. quinquefolia). Members of the Vitaceae are typically woody, show a climbing habit, have leaves that develop alternately on shoots (Fig. 2.1), and possess swollen or jointed nodes. These may generate tendrils or flower clusters opposite the leaves. The flowers are minute, uni- or bisexual, and occur in large clusters. Most flower parts appear in groups of fours or fives, with the stamens developing opposite the petals. The ovary consists of two carpels, partially enclosed by a receptacle that develops into a two-compartmented berry. The fruit contains up to four seeds.

The Vitaceae is predominantly a tropical to subtropical family, containing about 900 species, divided among some 14 genera (Galet, 1988). In contrast, Vitis is primarily a temperate-zone genus, occurring indigenously only in the Northern Hemisphere. Related genera include Acareosperma, Ampelocissus, Ampelopsis, Cayratia, Cissus, Clematicissus, Cyphostemma, Nothocissus, Parthenocissus, Pterisanthes, Pterocissus, Rhoicissus, Tetrastigma, and Yua.

The Genus Vitis

Grapevines are distinguished from related genera primarily on floral characteristics. The flowers are typically functionally unisexual, being either male (possessing erect, functional anthers, and lacking a fully developed pistil) or female (containing a functional pistil, and either producing recurved stamens and sterile pollen, or lacking anthers) (Fig. 2.2). The petals are fused, forming a calyptra or cap. The petals remain connected at the apex, only splitting along the base at maturity, when the calyptra is shed (see Plate 3.6). Occasionally, though, the petals may separate at the top, while remaining attached at the base (Plate 2.1). These ‘star’ flowers possess an appearance resembling typical flowers. This situation characterizes some members of the Vitaceae, for example Cissus. In some cultivars, star flower production is induced by cool temperatures, whereas in others it is a constitutional property (Longbottom et al., 2008). The trait is not genetically transmissible because star flowers are sterile, generating seedless berries (Chardonnay), or no fruit (Shiraz).

Swollen nectaries occur at the base of the ovary (see Fig. 3.25C). Despite their name, they do not produce nectar, but they produce a mild fragrance that attracts pollinating insects. The sepals of the calyx form only as vestiges and degenerate early in flower development. The fruit is juicy and acidic.

The genus has typically been divided into two subgenera, Vitis1 and Muscadinia. Vitis (bunch grapes) is the larger of the two subgenera, containing all species except V. rotundifolia and V. popenoei. The latter are placed in the subgenus Muscadinia (muscadine grapes). The two subgenera are sufficiently distinct to have induced some taxonomists to separate the muscadine grapes into their own genus, Muscadinia.

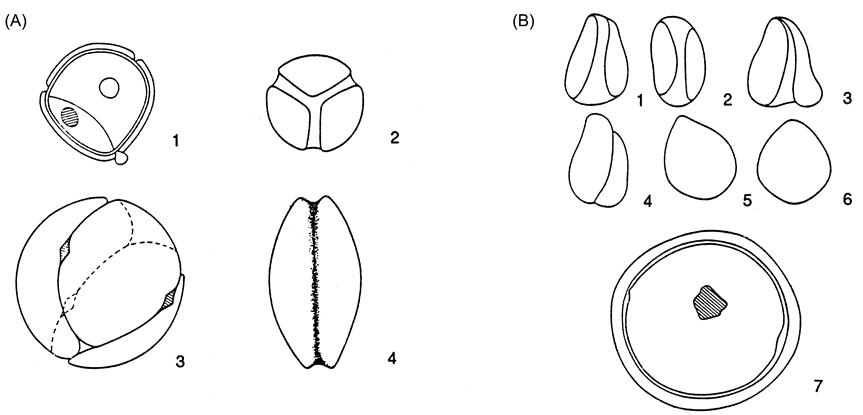

Members of the subgenus Vitis are characterized by having shredding bark, nonprominent lenticels, a pith interrupted at nodes by woody tissue (the diaphragm), tangentially positioned phloem fibers, branched tendrils, elongated flower clusters, berries that adhere to the fruit stalk at maturity, and pear-shaped seed possessing a prominent beak and smooth chalaza. The chalaza is a pronounced, circular, depressed region on the dorsal (back) side of the seed (Fig. 2.3C). In contrast, species in the subgenus Muscadinia possess a tight, nonshredding bark, prominent lenticels, no diaphragm interrupting the pith at nodes, radially arranged phloem fibers, unbranched tendrils, small floral clusters, berries that separate individually from the cluster at maturity, and boat-shaped seed with a wrinkled chalaza. Some of these characteristics are diagrammatically illustrated in Fig. 2.3. Plate 2.2 illustrates the appearance of Muscadinia grapes and leaves.

The two subgenera also differ in their chromosomal composition. Vitis species contain 38 chromosomes (2n=6x=38), whereas Muscadinia species possess 40 chromosomes (2n=6x=40). The symbol n refers to the number of chromosome pairs formed during meiosis, and x refers to the number of chromosome complements (genomes that were involved in their evolution).

Successful crosses can be experimentally produced between species of the two subgenera, primarily when V. rotundifolia is used as the pollen source. When V. vinifera is used as the male plant, the pollen germinates, but does not effectively penetrate the style of the V. rotundifolia flower (Lu and Lamikanra, 1996). This may result from the synthesis of inhibitors, such as quercetin glycosides in the pistil (Okamoto et al., 1995). Although generally showing vigorous growth, the progeny frequently are infertile. This probably results from imprecise pairing of the unequal number of chromosomes (19+20) and the consequential imbalanced separation of the chromosomes during meiosis. The genetic instability so produced disrupts pollen growth, resulting in infertility.

The evolution of the Vitaceae appears to have involved hybridization and subsequent chromosome doubling, a feature common in many plants (Soltis and Soltis, 2009). In the Vitaceae, three separate whole-genome duplication events are suspected, based on DNA genomic analyses (Jaillon et al., 2007; Velasco et al., 2007). Their proposals differ basically only in the timing of the duplications – whether the last duplication occurred before or after the progenitors of the Vitaceae split from other rosid dicotyledons. Velasco et al. (2007) consider that the last duplication involved at least 10 chromosomes. These views differ from the proposals of Patel and Olmo (1955). They viewed the timing of the ploidy events occurring after the genus Vitis evolved from other Vitaceae. Patel and Olmo used cytogenetic evidence to envision two duplication events – the first involving hybridization between progenitors with six and seven chromosome pairs (6+7=13, doubling to 26). Later, a second set of hybridization events of such tetraploids, with diploids of 12 and 14 chromosomes respectively, followed by chromosome doubling, gave rise to current day hexaploids – the subgenera Vitis (13+6=19, doubling to 38) and Muscadinia (13+7=20, doubling to 40) (Fig. 2.4). Variations in the chromosome numbers of other genera in the Vitaceae could be viewed as later modifications, involving phenomena such as chromosome loss, fusion, translocation, and/or doubling. For example, other Vitaceae possess 22 chromosomes (Cyphostemma); 22, and occasionally 44 (Tetrastigma); 24, and occasionally 22 or 26 (Cissus); 32, 72, or 98 (Cayratia), and 40 (Ampelocissus and Ampelopsis).

Older cytogenetic evidence, consistent with polyploidy, involves the apparent association of four nucleoli in species possessing 24 and 26 chromosomes, and six nucleoli-related chromosomes in species possessing 38 or 40 chromosomes. Typically, diploid species possess two nucleoli-related chromosomes. Chromosome structure itself provides little information concerning evolutionary events in the Vitaceae, due to their minute size (0.8–2.0 μm) and morphological similarity (Fig. 2.5)

Although polyploidy was involved in the evolution of the Vitaceae, members also appear to have undergone diploidization, similar to other polyploid angiosperms (Soltis and Soltis, 1999; Cui et al., 2006). Diploidization typically involves a relatively rapid and significant genomic reorganization (usually involving transposons). This is expressed in a structural modification of duplicate homologous genes from the combined genomes. This may explain why only two nucleoli appear prominently in the cells of Vitis spp. (Haas et al., 1994), in contrast to the six that might otherwise be expected.

The increased potential for adaptation to environmental change provided by polyploidy (mutational modification of unnecessary, duplicate genetic traits) seems to have been the principal evolutionary feature favoring hybridization and chromosomal doubling (Fawcett et al., 2009). Alternatively, gene duplicates are silenced, becoming nonfunctional (null) pseudogenes. This modification converts polyploids into functional diploids. An important secondary consequence of these structural modifications is preventing, or regulating, multivalent crossovers between multiple sets of similar chromosomes. This avoids unbalanced chromosome separation during meiosis, and the development of aneuploidy. Unequal chromosome complements in ovules and pollen often lead to partial or complete seed sterility.

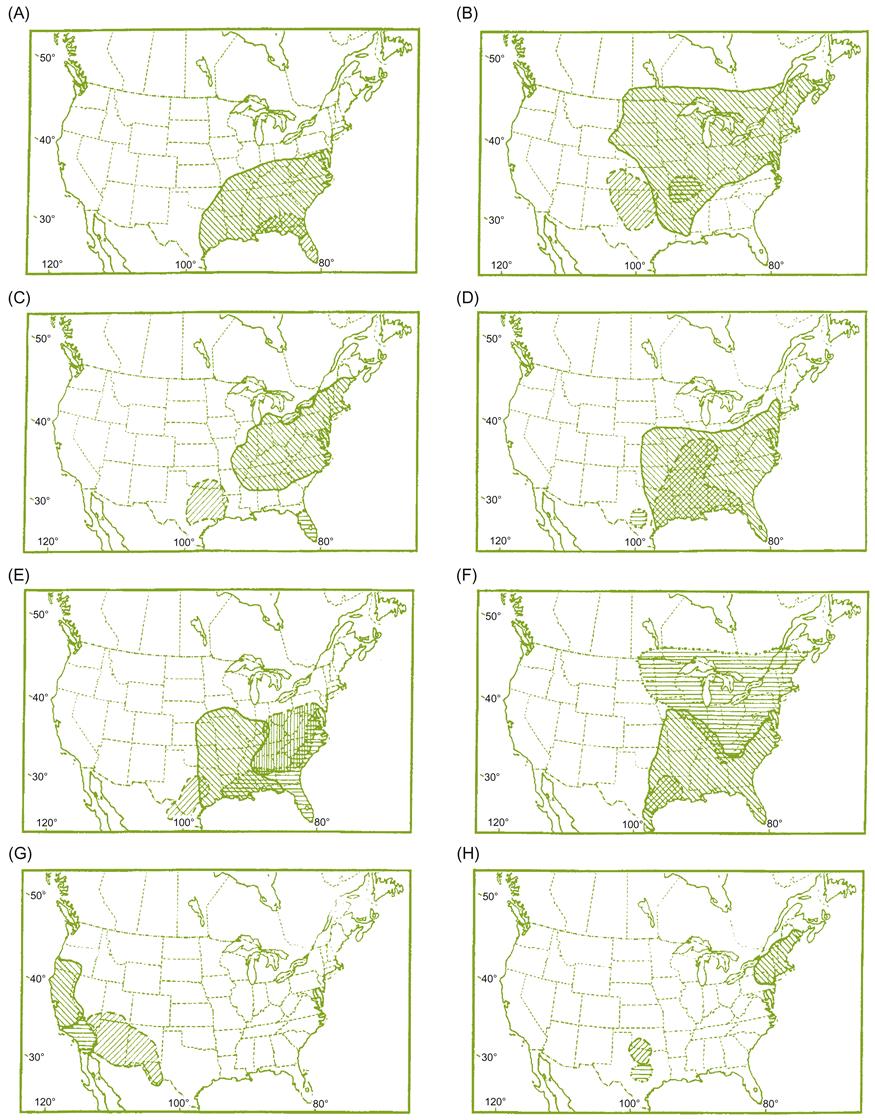

In contrast to the relative genetic isolation (infertility), imposed by the differing chromosome complements of the Vitis and Muscadinia subgenera, crossing among species within each subgenus produces fertile progeny. Although facilitating the incorporation of desirable traits from one species into another, the ease with which interspecies crossing occurs complicates the taxonomic task of delineating species. This is further compounded by many species possessing overlapping geographic distributions (Fig. 2.6), and the scarcity of distinctive morphological features. Quantitative differences that distinguish species, such as shoot and leaf hairiness, are often influenced by environmental conditions. This is often interpreted as evidence that speciation is still active within the genus, and evolution into distinct species remains incomplete – local populations often being viewed more as ecospecies or ecotypes than biological species. These complications may be partially resolved by molecular techniques (Tröndle et al., 2010).

The most recent classification of eastern North American species of Vitis is given by Moore (1991). A summary of the classification of Chinese species is given in Wan et al. (2008). Data derived from molecular (DNA) markers generally support relationships based traditionally on morphologic features, but also highlight differences (Aradhya et al., 2008). Their data suggest considerable gene flow among species.

Geographic Origin and Distribution of Vitis and Vitis vinifera

When and where the genus Vitis evolved is unclear. The current distribution includes northern South America (the Andean highlands of Colombia and Venezuela), Central and North America, Asia, and Europe. This would correlate with the ancestry of at least the original polyploidy having occurred while North America and Europe were still contiguous parts of Pangea. In contrast, species in the subgenus Muscadinia are restricted to the southeastern United States and northeastern Mexico, possibly indicating that its origin occurred close to or after North America had split from Pangea (the Cretaceous). This was the time when flowering plants began to replace gymnosperms as the predominate land plants. The North American distribution of Vitis species is shown in Fig. 2.6.

In the nineteenth century, many extinct species of Vitis were proposed, based on fossil leaf impressions (see Jongmans, 1939). The validity of many of these designations is now in question, due to the dubious nature of the evidence (Kirchheimer, 1938). Not only do several unrelated plants possess leaves similar in outline, but individual grapevines may show remarkable variation in leaf shape, lobbing, and dentation (Zapriagaeva, 1964). Of greater value in species delineation is seed morphology, even though significant interspecies variation also exists (Fig. 2.7). On the basis of seed morphology, two groups of fossilized grapes have been distinguished, Vitis ludwigii and V. teutonica. Seeds of the V. ludwigii type, resembling those of muscadine grapes, have been found in Europe from the Pliocene (2–10 million years b.p.). Those of the V. teutonica type, resembling those of bunch grapes, have been discovered as far back as the Eocene (34–55 million years b.p.). However, these identifications are based on comparatively few specimens, and, thus, any conclusions remain tenuous. In addition, related genera, such as Ampelocissus and Tetrastigma produce seed similar to those of Vitis. This would fit with the suspected much earlier evolution of these genera. In contrast, species radiation in the genus Vitis is estimated to have begun about 6–6.6 million years b.p. (Zecca et al., 2012). Although most grape fossils have been found in Europe, this may reflect more the distribution of appropriate sedimentary deposits (or paleobotanical interest and investigation) than Vitis distribution.

Baranov (in Zukovskij, 1950) suggests that the progenitors of Vitis were bushy and inhabited sunny locations. As forests expanded during the more humid Eocene, the development of a climbing habit would have permitted them to retain their preference for sunny conditions. This may have involved mutations modifying some floral clusters into tendrils, thus improving clinging ability. This hypothesis is not unreasonable in light of the differentiation of buds into flower clusters or tendrils, based on the relative balance of gibberellin versus cytokinin in the tissue (Srinivasan and Mullins, 1981; Martinez and Mantilla, 1993).

Regardless of the manner and geographic origin of Vitis, the genus established its present range by the end of the last major glacial period (~8000 b.c.). It is believed that periodic advances and retreats during the last glacial period markedly affected the evolution of Vitis, and its survival in Eurasia. The alignment of the major mountain ranges in the Americas, versus Eurasia, appears to have had an important bearing on the respective evolution of populations within the Northern Hemisphere. In the Americas and eastern China, the mountain ranges run predominantly north–south, whereas in Europe and western Asia they run principally east–west. This would have permitted North American and eastern Chinese species to relocate, south or north, relative to the movement of glacial ice sheets. In contrast, the southward movement of grapevine species in Europe and western Asia would have been largely restricted by the east–west mountain ranges (Pyrenees, Alps, Caucasus, and Himalayas). This may explain the much larger species presence in North and Central America (possessing some 34 endemic species – Rogers and Rogers, 1978) and China (possessing about 30 indigenous species – Fengqin et al., 1990). In contrast, Eurasia possesses but one, V. vinifera.

A few naturalized, foreign Vitis spp. are occasionally found in Europe. These are derived from ‘escaped’ rootstocks, imported for grafting, subsequent to the phylloxera epidemic in the late 1800 s (Arrigo and Arnold, 2007), or cultivated as a fruit crop (Cangi et al., 2006). Some of these have also yielded hybrids with indigenous wild Vitis vinifera (Bodor et al., 2010).

Although glaciation and cold destroyed most of the favorable habitats in the Northern Hemisphere during the last ice age, major southward displacement was not the only option open for survival. In certain areas, isolated but favorable sites (refuges) permitted continued existence throughout the glacial period. In Europe, refuges occurred around the Mediterranean basin, and south of the Black and Caspian Seas (Fig. 2.8). For example, grape seeds have been found associated with anthropogenic remains in caves in Southern Greece (Renfrew, 1995) and Southern France (Vaquer et al., 1985), both near the end of the last glacial advance. These refuges may have played a role in the evolution of the various varietal groups of Vitis vinifera (see below).

Although periodically displaced during the various Quaternary glacial periods (Fig. 2.9), V. vinifera was inhabiting southern regions of France and northern Greece some 10,000 years ago (Planchais and Vergara, 1984; Wijistra, 1969). For the next several thousand years, the climate slowly improved to an isotherm about 2–3 °C warmer than current (Dorf, 1960). Preferred habitats of wild V. vinifera were in the mild, humid forests south of the Caspian and Black Seas and adjacent Transcaucasia, along the fringes of the cooler mesic forests of the northern Mediterranean, and into the heartland of Europe, along the banks and hillsides of the Danube, Rhine, and Rhône rivers. The current situation of wild Vitis vinifera is discussed in Arnold et al. (1998).

Domestication of Vitis vinifera

Grapevine cultivars show few of the standard signs of plant domestication noted by Baker (1972) and de Wet and Harlan (1975). Their views can be summarized as follows: conversion from cross- to self-fertilization, release from the need for seed and bud vernalization (cold treatment), elimination of photoperiod phenologic regulation, inactivation of seed dehiscence or fruit separation upon maturation, development of parthenocissus (fruit production independent of seed development), increase in shoot to root ratio, enhanced fruit (or seed) size, augmentation in crop yield, reduction in phytotoxin production, and a shift from a bi- or perennial habit to an annual habit.

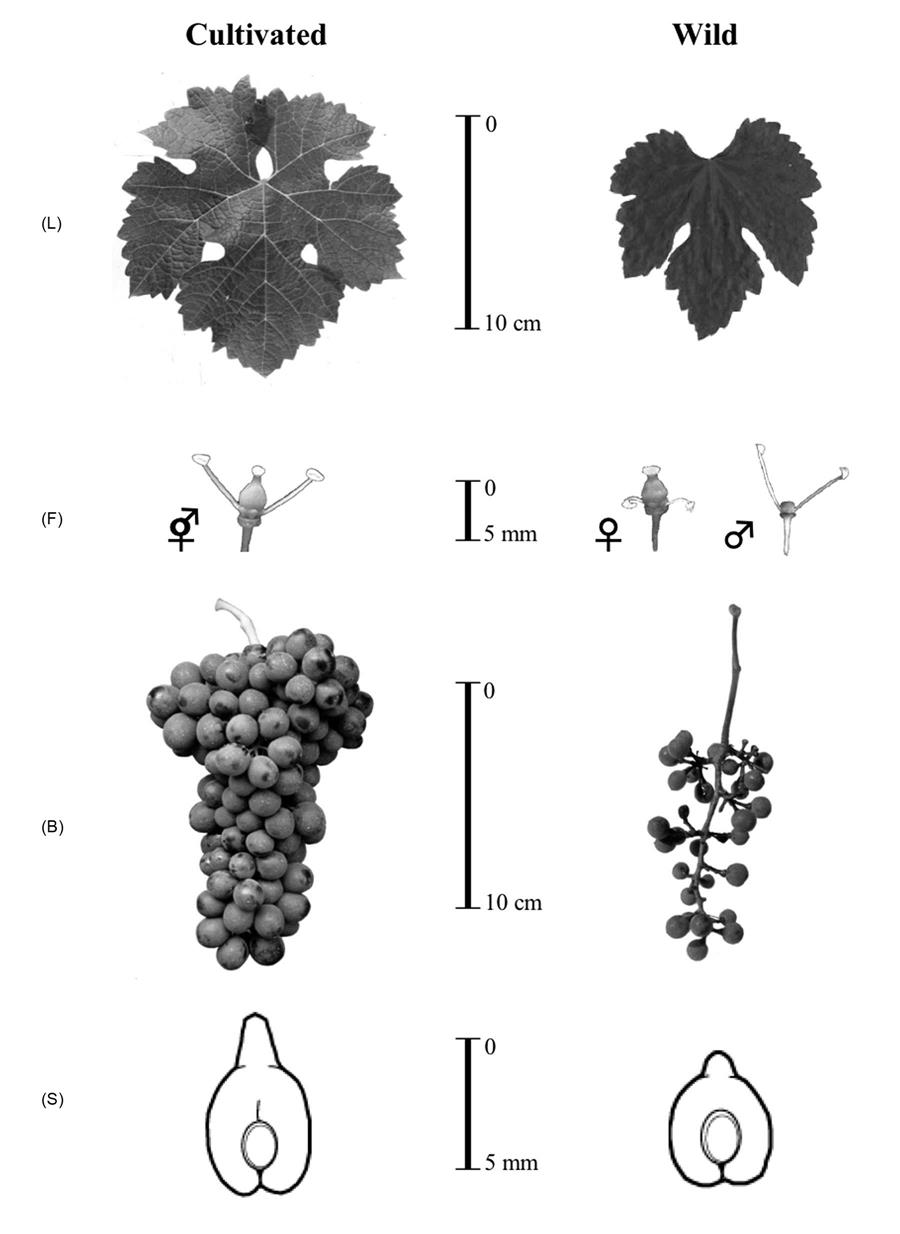

Of these changes, only conversion to self-fertility is clearly expressed in domesticated grapevines. Other modifications associated with domestication are less marked. There is a slight reduction in photoperiod sensitivity and need for seed vernalization; easier fruit separation from the cluster; increased fruit size (notably in table grapes); and seedlessness in some table and raisin cultivars. Other features that tend to differentiate wild from domesticated grapevines include a shift from small, round berries to larger, elongated fruit; more fruit per cluster; bark separating in wider, core-coherent strips (vs. bark separating in long thin strips); larger, elongated seeds (vs. smaller, rounded seeds); and large leaves with entire or shallow sinuses (vs. smaller, usually deep, three-lobed leaves) (Olmo, 1976). Some of these features are illustrated in Fig. 2.10. Plate 2.3 also illustrates the characteristic features of wild (sylvestris) grape clusters, including the dominant (wild-type) bluish fruit coloration.

The principal indicator of domestication, detectable in archaeological remains, is a shift in seed index – the ratio of seed width to length. Although of no known selective advantage, the shift appears to correlate with a change from cross- to self-fertilization. This may reflect some unknown and unsuspected pleiotrophic effects. Seed from wild (sylvestris) vines are rounder, possess a nonprominent beak, and show an average seed index of about 0.64 (ranging from 0.54 to 0.82). In contrast, seed from domesticated (sativa) vines are more elongated, possess a prominent beak, and have a seed index averaging about 0.55 (often ranging from 0.44 to 0.75) (Renfrew, 1973; Fig. 2.11). However, evidence based on carbonated seed remains may be of uncertain value. Charring appears to increase the relative seed length, decreasing the seed index (Margaritis and Jones, 2006). It does, though, enhance survival in sites. In addition, considerable variation in seed size and shape (Zapriagaeva, 1964) makes conclusions based on small sample sizes unreliable.

Seed index data have been used by Miller (1991) to suggest a slow domestication of grapevines in northeastern Iran and Anatolia. However, clear evidence of domestication begins only in the late fourth millennium b.c., in Jericho about 3200 b.c. (Hopf, 1983), and after 2800 b.c. in Macedonia and Greece (Renfrew, 1995). This is considerably later than the first archaeological evidence suggestive of wine production in northern Iran (5400–5000 b.c.) (McGovern et al., 1996). However, the time frame is consistent with the predicted spread of agriculture out of the Fertile Crescent into northern Iran and Anatolia (Ammerman and Cavalli-Sporza, 1971). Thus, the production of wine may have developed concurrently with agriculture, but predated preserved morphological evidence of grapevine domestication (Zohary, 1995).

In Europe, the earliest presumptive evidence of winemaking comes from the northern Aegean, dating from the latter half of the fifth millennium b.c. (Valamoti et al., 2007). In western Europe, evidence of wild grapevine use has been found in a Neolithic village near Paris (about 4000 b.c.) (Dietsch, 1996). Semidomesticated grape seed remains (2700 b.c.) have been discovered in England (Jones and Legge, 1987), and in several Neolithic and Bronze Age lake dwellings in northern Italy, Switzerland, and the former Yugoslavia (see Renfrew, 1973). In addition, grape seed and pollen remains have been identified from Neolithic sites in Southern Sweden and Denmark (see Rausing, 1990). At that time, the climate was warmer than today. Evidence consistent with grape culture in southwestern Spain has been found dating from about 2500 b.c. (Stevenson, 1985).

Differences in floral sexual expression and leaf shape occur between wild and domesticated grapevines (Levadoux, 1956). For example, male vines have larger inflorescences, flower earlier, and for a longer period than bisexual flowers (Negi and Olmo, 1971). Male flowers also show poorly developed nectaries. These features are, however, not preserved or recognizable in vine remains. Additional differences have been noted by Patel and Olmo (1955), but most of these features are readily influenced by cultivation.

Another potentially useful property, preserved in archaeological remains, involves changes in the fruit pedicel (see Fig. 3.23 for terminology). In domesticated Vitis vinifera, the pedicel frequently breaks at the main stem (rachis) when the berries are pulled. In contrast, this seldom occurs with wild vines, due to their stouter stems. Thus, the relative frequency of fruit remains attached to the pedicel may be an indicator of domestication in archaeological remains.

Nonetheless, of all fossil evidence, the greatest confidence can be placed in pollen data. Pollen found in sedimentary deposits is sufficiently distinct and well preserved to establish the presence of a species or subspecies at a prehistoric site (Fig. 2.9). The outer wall (exine) of pollen consists primarily of sporopollenin, a material particularly resistant to decay. Pollen frequency is often used as an indicator of the relative abundance of wind-pollinated species in a region. Correspondingly, grapevine pollen frequency has been used as an indicator of ancient viticulture (Turner and Brown, 2004). For example, a pronounced increase in pollen counts was associated with increased human activity and presumptive viticulture in northern Greece after 1500 a.d. (Bottema, 1982).

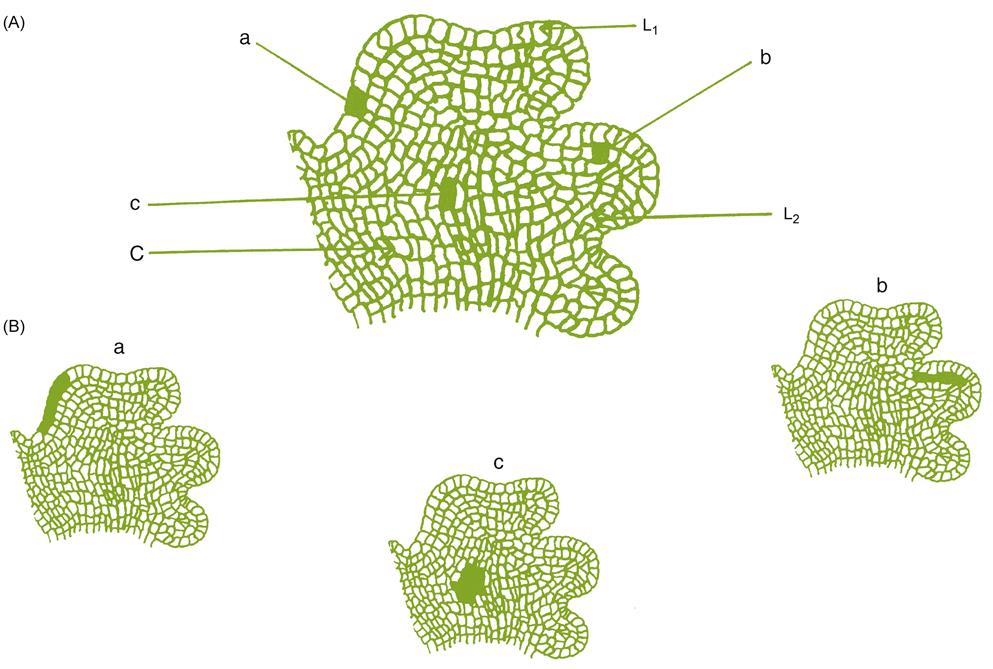

Of particular interest is the difference between fertile pollen (produced by male and bisexual flowers) and sterile pollen (produced by some female flowers). Fertile pollen in Vitis vinifera is tricolporate (containing three distinct ridges) and produces germ pores, whereas sterile pollen is generally acolporate (possessing no ridges) and produces no germ pores (Fig. 2.12). Thus far, differences in the fertile/infertile pollen ratio have not been used in assessing the relative frequency of dioecious (wild) and bisexual (cultivated) vines at prehistoric sites. This may result from the poorer release of pollen from bisexual flowers and corresponding limited collection in sedimentary deposits. Nevertheless, pollen differences have been used in distinguishing the presence, or absence, of domesticated vines near ancient lake and river sediments (Planchais, 1972–1973).

As noted, it is generally believed that domestication began in or around Transcaucasia, or neighboring Anatolia, about 4000 b.c. About 8000 years ago, the climate started to become warmer and generally more humid than currently. In particular, rainfall increased considerably in eastern Anatolia. This was associated with an advance of a Quercus-dominated steppe-forest into what had been a semiarid environment. The forest reached its maximum extension about 4200 b.c. (Wick et al., 2003). Thus, growth of V. vinifera was likely more extensive in regions associated with the earliest known archaeological evidence of wine production (northwestern Zargos mountains) than today. This is also the region in which domestication of wheat (Einkorn) is thought to have begun (Heun et al., 1997). Subsequent climatic drying, beginning about 2000 b.c., slowly shifted the vegetation to match the current semiarid state, resulting in a shrinkage of the Vitis habitat. Further shrinkage of feral V. vinifera populations in recent times has been due to human habitat destruction and the decimation caused by the phylloxera outbreak that ensued after its accidental introduction in the mid-1850s. Its likely distribution, just prior to the phylloxera epidemic, is illustrated in Fig. 2.8.

Conversely, Núñez and Walker (1989) have also found evidence strongly suggestive of grapevine domestication in Southern Spain. This is long before Phoenician and Phocaean (Canaanite and Ionian Greek, respectively) colonizations, beginning about 800 b.c. They established colonies along the western coast of North Africa and the eastern Iberian Peninsula. The existence of at least two independent centers of grapevine domestication has also received molecular support from Arroyo-García et al. (2006).

Cultivars were carried westward in association with colonization. Their transplantation in Italy and southern France by ancient Greek colonists, and into France, Spain, and Germany by Roman settlers, is suggested from ancient writings. Even more certain is the implantation of a grape-growing and winemaking culture; the transport of grapevines into areas such as Israel, Egypt, and ancient Babylonia is even more indisputable. The vine is indigenous to none of these regions.

Despite human migration and its consequences, changes in seed morphology and pollen shape indicate that local grape domestication was in progress in Europe long before the agricultural revolution reached southern and central Europe. Traits such as self-fertilization and large fruit size have often been attributed to varieties brought in by human activity, but this is not requisite. Fruit size often increases under cultivation, but berry size could have also resulted from mutation in the flb gene (or possibly related genes) (Fernandez et al., 2006). Bisexuality occurs in Vitis species, albeit rarely (Fengqin et al., 1990). Thus, the occurrence of a bisexual habit in indigenous wild (sylvestris) populations (Schumann, 1974; Failla et al., 1992; Anzani et al., 1990) need not presuppose crossing between wild and domesticated vines.

Diversification of fruit color is another feature often associated with domestication. From the wide color diversity in modern grape cultivars (e.g., Plate 2.4), this property seems to have been selected for centuries. Nonetheless, one of the genetic factors leading to a loss in anthocyanin synthesis appears to have occurred millennia before domestication (Mitani et al., 2009).

Locally derived cultivars would have had the advantage of being already adapted to prevailing soil and climatic conditions. In addition, data suggest that most cultivars fall into ecogeographic groups (Bourquin et al., 1993), consistent with local origin. The presence of numerous traits (such as rounder seeds), reminiscent of V. vinifera f. sylvestris, occur in cultivars such as Traminer, Pinot noir, and Riesling. This has been construed as evidence of indigenous origin. This, of course, does not preclude the possibility of crossing and trait introgression from imported cultivars. Comparison of the genetic traits of long-established Italian varieties with indigenous feral vines is consistent with some (Grassi et al., 2003), but not all, cultivars (Scienza et al., 1994) having been derived locally. This also applies to Iberian cultivars (Arroyo-García et al., 2006). Data from a range of studies suggest that European cultivars originated from a mix of importation, introgression, and de novo domestication.

Until devastated by foreign pests and disease in the middle of the nineteenth century, wild grapevines grew extensively from Spain to Turkmenistan. Although markedly diminished at present, wild vines still occur in significant numbers in some portions of its original range, notably the Caucasus. Efforts to discover and preserve these wild populations are in progress. They are considered a genetic reserve of diversity not existent in modern cultivars. This view is supported by the greater anthocyanin diversity in wild accessions than in domesticated cultivars (Revilla et al., 2010).

Domestication probably occurred progressively, with the slow accumulation of agronomically valuable mutations. The early association of wine with religious rites in the Near East (Stanislawski, 1975) could have provided the incentive for cultivar selection, and the beginnings of concerted viticulture. Initially, cultivation would have required the planting of both fruit-bearing (female) and non-fruit-bearing (male) vines. Propagating only fruit-bearing cuttings would have resulted in a reduction or cessation of productivity, by separating female vines from pollen-bearing vines (growing wild in potentially distant, open, moist woodlands or riparian habitats). So doing would have highlighted the productivity of any self-fertile revertants, and presumably led to their selection. Viticulture also would have favored the selection of vines showing increased fruit size, as well as improved visual, taste, and aroma attributes. An obvious example might be the augmented terpene production in Muscat cultivars.

Additional support for the connection between winemaking and grapevine domestication comes from the remarkable similarity between the words for wine and vine in European languages (Table 2.1). In contrast, little resemblance exists between words for grape. The persistence of local terms for grape in European languages suggests that grapes were used (and recognized verbally) long before the introduction of viticulture and winemaking. The spread of related terms for wine and the vine may have been associated with the demic diffusion of Neolithic farmers (Chicki et al., 2002; Bramanti et al., 2009), and the associated dispersion of Indo-European languages, into Europe (Renfrew, 1989). This tendency undoubtedly was accentuated by the dispersion of Roman culture, millennia later. This, in turn, was preceded by the implantation of Greek cultural traditions and colonies into Italy and southern France beginning in the eighth and seventh centuries b.c. The development of viticulture and winemaking spread (or developed independently) in Early Bronze Age Macedonia and Crete during the third millennium b.c. (Hamilakis, 1999; Valamoti et al., 2007). One perception of diffusion routes into Europe is given in Fig. 2.13.

Table 2.1

Comparison of synonyms for ‘wine,’ ‘vine,’ and ‘grape’ in the principal Indo-European languages

Source: Information from Buck (1949).

In contrast, in Near Eastern regions, where grapevines are not indigenous, the terms for grape, wine, and grapevines all have the same root derivation (Forbes, 1965). This similarity is consistent with the likelihood that wine preceded, or coincided with, the appearance of the grapevine and winemaking in Semitic cultures. Gamkrelidze and Ivanov (1990) believe their related terms are all derived from what may have been the archetypal word for wine, woi-no.

The advanced state of cultivar variation in the southern Caucasus is also consistent with this region being associated with early grapevine domestication. Local varieties possess many recessive mutants, such as smooth leaves, large branched grape clusters, and medium-size juicy fruit. The number of accumulated recessive traits is often considered an indicator of cultivar age. Varieties showing these traits were classified by Negrul (1938) as members of proles orientalis. Also included in this group are the genetically distinct V. vinifera cultivars of China and Japan (Goto-Yamamoto et al., 2006). Evidence from Jiang et al. (2009) suggests that the first tentative cultivation of V. vinifera began in China about 300 b.c. Cultivars in the northern Mediterranean and in central Europe were viewed by Negrul as being of relatively recent origin (middle to late first millennium b.c.). This view was based on their possessing few recessive traits, and their close resemblance to wild vines. They were placed in proles occidentalis. Varieties found in contiguous regions (e.g., Georgia and the Balkans) show properties intermediate between proles orientalis and proles occidentalis. These Negrul designated as proles pontica. Characteristics of the three groupings are given in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2

Classification of varieties of Vitis vinifera according to Negrul (1938)

| Proles orientalis | Proles pontica | Proles occidentalis |

| Regions | ||

| Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, Armenia, Azerbaijan | Georgia, Asia Minor, Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania | France, Germany, Spain, Portugal |

| Vine properties | ||

| Buds glabrous, shiny | Buds velvety, ash-gray to white | Buds weakly velvety |

| Lower leaf surfaces glabrous to setaceous pubescent | Lower leaf surface with mixed pubescence (webbed and setaceous) | Lower leaf surfaces with webbed pubescence |

| Leaf edges recurved toward the tip | Leaf edges variously recurved | Leaf edges recurved toward the base |

| Grape clusters large, loose, often branching | Grape clusters medium size, compact, rarely loose | Grape clusters generally very large, compact |

| Fruit generally oval, ovoid, or elongated, medium to large, pulpy | Fruit typically round, medium to small, juicy | Fruit often round, more rarely oval, small to medium, juicy |

| Varieties mostly white with about 30% rosés | About equal numbers of white, rosé, and red varieties | Varieties commonly white or red |

| Seeds medium to large with an elongated beak | Seeds small, medium, or large (table grapes) | Seeds small with a marked beak |

| Fruiting properties | ||

| Many varieties partially seedless, some seedless | Many varieties partially seedless, some completely so | Seedless varieties rare |

| Varieties produce few, low-yielding fruiting shoots | Varieties often produce several, highly productive fruiting shoots | Varieties typically produce several, highly productive fruiting shoots |

| Varieties short-day plants with long growing periods, not cold-hardy | Varieties relatively cold-hardy | Varieties long-day plants with short growing periods, cold-hardy |

| Most varieties are table grapes, few possess good winemaking properties | Many varieties are good winemaking cultivars, a few are table grapes | Most varieties possessing good winemaking properties |

| Grapes low in acidity (0.3–0.6%), sugar content commonly 18–20% | Grapes acidic (0.6–1.0%), sugar content commonly 18–20% | Grapes acidic (0.6–1%), sugar content commonly 18–20% |

| Self-crossed seedling of certain varieties possessing simple leaves | Self-crossed seedings of certain varieties with dwarfed shoots and rounded form | Self-crossed seedlings of certain varieties having mottled colored leaves |

Source: After Levadoux (1956), reproduced by permission.

Additional studies along these lines were conducted by Levadoux (1956). Extensions of Negrul’s classification system can be found in Tsertsvadze (1986), and Gramotenko and Troshin (1988). The division of cultivars, and the probability of distinct centers of origin, have received modern support from Aradhya et al. (2003) and Arroyo-García et al. (2006). In addition, table grapes (more common in the Near East) show greater genetic divergence from wild grapes than do wine grapes. Table grapes also possess distinctive traits not found in wine grapes.

Cultivar Origins

Except for cultivars of recent origin, for which there is a documented record, the origin of most cultivars is shrouded in mystery. Archaeological finds are insufficiently detailed, while ancient writings do not discuss the issue. The written record of intentional plant breeding begins only in the late 1600 s, with the development of hybrid hyacinths in Holland. However, selection of improved strains of food crops (probably associated with accidental crossings) clearly goes back to the origins of agriculture (Zohary and Hopf, 2000).

For annual crops, seed collection for the next year’s crop has functioned as the principal agent for cultivar propagation, and, indirectly, development. In contrast, for perennial crops such as grapevines, vegetative propagation has been the main means by which cultivars were reproduced and variation selected. In both instances, cultivar evolution undoubtedly occurred over long periods and occurred surreptitiously. For grapevines, it was both simpler and quicker to propagate by layering (and subsequently by cuttings). Had anyone purposely planted seeds, the new vines would have had properties considerably different from those of the parent vine. Astute growers would have quickly realized that layering (or cuttings) maintained and multiplied vines possessing desirable traits.

During Roman times, it is clear that the benefits of breeding were well known, at least for animals. However, if evidence from existing European grape cultivars is correct, introgression played a significant role in their development. Crossing probably occurred accidentally, due to pollen from proximate feral vines fertilizing cultivated vines. Alternatively, the random intermixture of cultivars, typical during the medieval period, would have favored intercultivar crossing. Cultivar admixture possibly had the advantage of buffering against the vagaries of climate and soil conditions. Although the fortuitous germination and growth of seeding to maturity in established vineyards seem unlikely, both events might have occurred in small peasant kitchen gardens or outbuildings. Because fruit as well as leaves often show marked phenotypic variability (the latter property being used as the basis for ampelography), recognizing differences among vines could have been easily detected by observant growers. If intentional breeding and selection were practiced, there appear to be no records of such activity. The most likely sites for such activities would have been abbeys and noble estates with established vineyards. Monks had the advantage of being able to read ancient texts, as well as the time and writing skills to observe and collect data on vine performance. That deliberate breeding was involved seems supported by molecular evidence that permits the construction of intertwined pedigree lines, linking the parentage for several Italian and French cultivars (Fig. 2.14).

Even before molecular means of assessing cultivar origins became available, many cultivars were considered ancient. However, the evidence was dubious. There were even attempts to associate some existant cultivars with those named by Pliny, for example Greco with vitis aminea gemina, Fiano with vitis apiano, and Sciascinoso with vitis oleagina (see Thomson, 2004). During the Middle Ages, varietal designation was largely abandoned. Wine itself was principally differentiated into two categories: vinum hunicum (poor quality) and vinum francicum (high quality). These terms subsequently were applied respectively to groups of cultivars (Heunisch and Frankisch) (Schumann, 1997). Precise cultivar designation began to reappear in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries – examples being Traminer (1349), Ruländer (1375), and Riesling (1435) (Ambrosi et al., 1994).

Name derivation has occasionally been used to suggest local origin, for example Sémillon from semis (seed), and Sauvignon from sauvage (wild) (Levadoux, 1956). However, the existence of multiple and unrelated synonyms for many European cultivars does not lend credence to name derivation as an important line of argument. Much greater confidence can be placed in DNA studies. They have provided clear evidence of the local origin of many well-known European cultivars.

Until the development of DNA sequencing, the best evidence for varietal origin came from morphological (ampelographic) comparisons. Such data were particularly useful when cultivars had diverged from a common ancestor, via somatic mutation. Examples are the color mutants of Pinot noir—Pinot gris, and Pinot blanc. Vegetative propagation maintains the traits of the progenitor, except where modified by somatic mutations. In contrast, seed propagation in highly heterozygous plants, such as the grapevine, produces progeny that can possess markedly different characteristics than their parents (Bronner and Oliveira, 1990). This tends to blur morphologic traits, making leaf characteristics suspect as indicators of varietal origin.

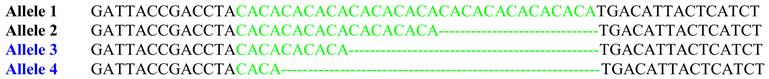

Another line of evidence involved chemical indicators. Isozyme and phenolic distributions are examples. However, the growing number of DNA fingerprinting techniques, such as amplified fragment-polymorphism (AFLP) and microsatellite allele (simple sequence repeat) (SSR) analysis are far more powerful and universally applicable. They circumvent some of the difficulties associated with interpreting restriction fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns, and standardization with the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) procedure. In addition, because microsatellite markers are seldom located in functional genomic regions, mutations in them tend to be evolutionarily neutral. Thus, they are unaffected by selective pressure. This permits the rapid (in terms of centuries) accumulation of variations, permitting varietal (but usually not clonal) differentiation. Markers may contain one or multiple nucleotide repeats, for example as noted below in the accompanying illustration.

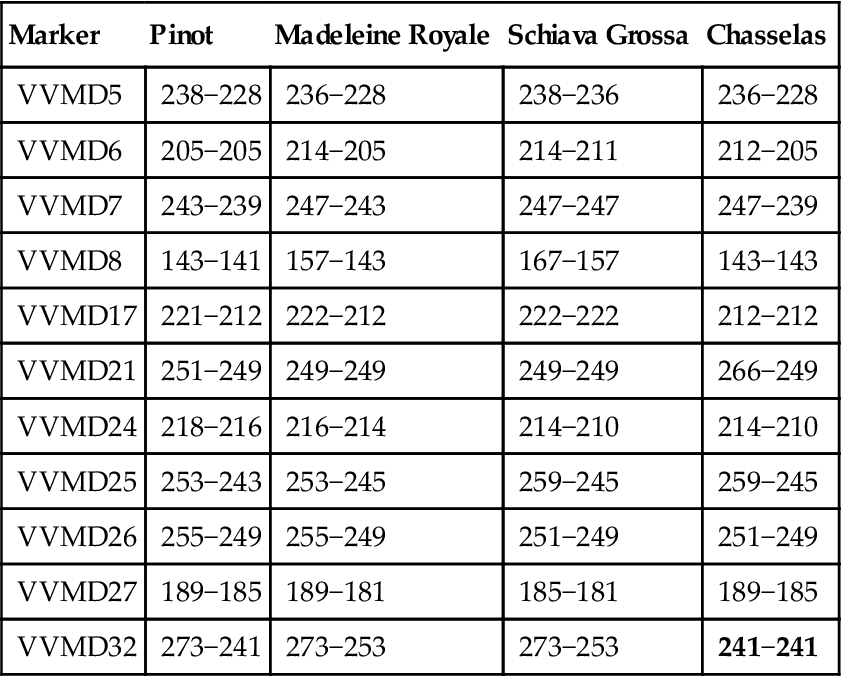

Microsatellite markers also have the advantage of high polymorphism. In addition, they are inherited co-dominantly (valuable in parentage studies). For example, crossing vines possessing VVMD5 genotypes with base-pair lengths 228/238 and 236/236 could yield offspring only with 228/236 or 238/236 genotypes. When comparing the genotypes of varieties for multiple SSR markers, it is possible to predict their likely relatedness (e.g., parents, offspring, or siblings) (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3

Partial data indicating the presumptive parentage of Madeleine Royale as a cross between Pinot and Schiava Grossa. The relationship between Madeleine Royale and Chasselas is ruled out by discrepancies (bold)

| Marker | Pinot | Madeleine Royale | Schiava Grossa | Chasselas |

| VVMD5 | 238−228 | 236−228 | 238−236 | 236−228 |

| VVMD6 | 205−205 | 214−205 | 214−211 | 212−205 |

| VVMD7 | 243−239 | 247−243 | 247−247 | 247−239 |

| VVMD8 | 143−141 | 157−143 | 167−157 | 143−143 |

| VVMD17 | 221−212 | 222−212 | 222−222 | 212−212 |

| VVMD21 | 251−249 | 249−249 | 249−249 | 266−249 |

| VVMD24 | 218−216 | 216−214 | 214−210 | 214−210 |

| VVMD25 | 253−243 | 253−245 | 259−245 | 259−245 |

| VVMD26 | 255−249 | 255−249 | 251−249 | 251−249 |

| VVMD27 | 189−185 | 189−181 | 185−181 | 189−185 |

| VVMD32 | 273−241 | 273−253 | 273−253 | 241−241 |

Source: Data from Vouillamoz and Arnold (2010).

Automation of microsatellite analysis, combined with the functional diploidy, heterozygosity, and the small genome of grapevines (475–500 Mb), have made SSR analysis the preferred tool in parentage and synonymy studies. The latter have been particularly useful in identifying the cultivars found in old, traditional vineyards (Jung and Maul, 2004). These have proven ‘treasure troves’ of variants of old and near-extinct varieties. Their preservation is sought as a reserve of the existant genetic diversity in cultivated Vitis vinifera. These studies are being assisted by the development of a map designating the relative position of large numbers of markers on 19 linkage groups (Vezzulli et al., 2008). Advances in this field are occurring at a dizzying pace.

Additional markers from chloroplast DNA are of particular interest in determining maternal inheritance – chloroplast DNA (as well as mitochondrial DNA) are derived only from the egg cell (Strefeler et al., 1992; Arroyo-García et al., 2002). This has permitted the identification of Gouais blanc as the maternal parent of cultivars such as Chardonnay, Gamay noir and Aligoté (Hunt et al., 2009), and Sauvignon blanc as the female parent of Cabernet Sauvignon. This determination is of more than just academic interest. Chloroplast DNA can influence properties such as chilling injury (Chung et al., 2007) and fungal toxin tolerance (Avni et al. 1992). In addition, it has attributes superior to nuclear DNA in discerning evolutionary trends, due to its low mutation rate and the absence of genetic recombination typical of nuclear DNA. These attributes have been used to identify two regions (central Italy and the Caucasus) as being ancient genomic refuges from the last European glacial period (Grassi et al., 2006); as demonstrating the extensive genetic diversity of Georgian cultivars (Schaal et al., 2010); and as denoting the likely center of diversity for many European cultivars (Imazio et al., 2006).

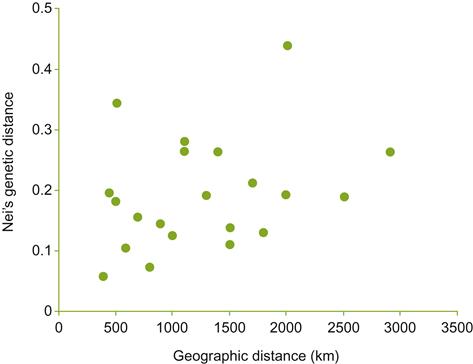

Molecular studies have also confirmed the involvement of local wild vines in the origin of many cultivars. For example, Grassi et al. (2003) demonstrated moderate genetic similarity between two Sardinian cultivars and local feral vines, suggestive of introgression. In contrast, mainland Italian varieties seem to be a mix of introduced cultivars and those introgressed with sympatric wild vines. The influence of indigenous vines on the origin of regional cultivars in western and central Europe has received support from studies by Sefc et al. (2003). Their data show that the genetic divergence among 164 cultivars was roughly correlated with their geographic separation (Fig. 2.15). Spanish and Portuguese cultivars showed the most marked similarity, followed by French/German/Austrian cultivars. Also, Vantini et al. (2003) have shown the close similarity of local Veronese cultivars. In Georgia, Ekhvaia et al. (2010) found extensive genetic similarity between local cultivars and sympatric feral vines; for example, Rkátsiteli showed 90% similarity with wild vines growing in the Lekjura Gorge. In addition, significant differentiation between Greek and Italian cultivars, as well as Italian and French ones, suggests that the importation of cultivars by Greek and Roman colonists into Italy has been exaggerated. Data from chloroplast DNA lend further support to the view that many western European cultivars were selected (bred) locally (Arroyo-García et al., 2002). Finally, Vouillamoz et al. (2006) have demonstrated the comparative genetic separation between Georgian, Armenian, and Turkish cultivars.

In contrast, several studies have provided data supportive of the importance of cultivar importation. Vouillamoz et al. (2006) had data implicative of the involvement of Georgian cultivars in the origin of several important Western European cultivars. These include Muscat, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Pinot noir, Nebbiolo, and Chasselas. This view is further supported by an analysis of over 1000 French and German accessions (specifically designated and cultured clones). It implicates introgression with eastern cultivars (Myles et al., 2011). For table grapes, Dzhambazova et al. (2009) and Snoussi et al. (2004) also found data suggestive of introduction versus local domestication of Bulgarian and Tunisian table grapes, respectively. Importation also seem important in the origin of North African cultivars (Riahi et al., 2012).

Thus, not surprisingly, there appears to be no simple or common denominator to the origin of existent cultivars, some appearing to be selections from local wild vines, others being the offspring of imported and sympatric feral vines, and still others being transplanted from elsewhere, possessing no direct genetic relationship to indigenous vines.

For cultivars where presumptive parents are known, it is unknown whether the crosses occurred spontaneously or purposefully. Cultivars where parents are fairly certain include Chardonnay (Pinot noir×Gouais blanc) (Bowers et al., 1999); Cabernet Sauvignon (Cabernet franc×Sauvignon blanc) (Bowers and Meredith, 1997); and Merlot (Cabernet franc×Magdeleine Noire des Charentes) (Boursiquot et al. 2009). Other examples include Silvaner (likely the progeny of Traminer×Österreichisch weiß) (Sefc et al., 1998); Sangiovese (a crossing of the Calabrian cultivars, Ciliegiolo and Calabrese de Montenuovo) (Vouillamoz et al., 2007); and Syrah (Shiraz) (the offspring of two southern French cultivars, Dureza and Mondeuse blanche) (Bowers et al., 2000). Other suggestions, such as Pinot noir (Traminer×Meunier) (Regner et al., 2000) are possible, but have yet to be confirmed. Most researchers consider Meunier just a clonal variant of Pinot noir.

Many important cultivars appear to have involved a common parent (Fig. 2.16). Traminer appears to be one of the parents of cultivars such as Riesling, Sauvignon blanc, and Chenin Blanc. Pinot noir also appears to have parented multiple offspring. Surprisingly, a cultivar of little apparent enologic significance, Gouais blanc (syn. Weißer Heunisch), is the presumptive parent, along with Pinot, of multiple French cultivars, notably Chardonnay, Gamay noir, Aligoté, and Melon (Bowers et al., 1999).

The relative success of Gouais blanc×Pinot noir progeny is partially mirrored in the importance of Sangiovese and Garganega in the origins of many Italian cultivars (Fig. 2.17; Di Vecchi Staraz et al., 2007), and Listán Prieto in South America (Tapia et al., 2007). The latter, a little-known Spanish cultivar, crossed with Muscat of Alexandria, gave rise to two Torrontés varieties, and with Jaen B, and Negra Mole, to produce other local cultivars. Listán Prieto was important in the establishment of vineyards in the Americas, being variously called Mission, Pais, or Criolla chica in California, Chile, and Mexico, respectively.

Although the actual origins of many cultivars may never be known with certainly, due to actual parents no longer existing, DNA studies can suggest probable ancestry. The inclusion of multiple SSR markers greatly reduces the probability of false positives. Twenty-five markers are often considered a minimum. While certainty of parentage is difficult, DNA fingerprinting techniques can easily establish what is essentially impossible. For example, it has shown that Müller-Thurgau is neither the result of a Riesling self-cross, nor a Riesling×Silvaner cross (Büscher et al., 1994). Riesling and Madeleine Royale are most likely the actual progenitors of Müller-Thurgau (Dettweiler et al., 2000). Microsatellite analysis has also shown the presumed parentage of some recent Ukranian cultivars to be in error (Goryslavets et al., 2010). The technique has even revealed unsuspected aspects of the diversity and geographic distribution of Cabernet Sauvignon (Moncada et al., 2006) and Merlot (Herrera et al., 2002) clones. In the latter instance, the clone of Merlot grown in Chile is distinctly different than that typical in France.

One of the limitations of all such studies is that they must be based on existent cultivars. What potential lineages might be suggested were extinct cultivars or feral strains available for sampling will never be known. Although most cultivars thus far investigated appear to be monozygous (derived from a single seed), this does not necessarily imply genetic identity. Mutations, subsequent to origin, can give rise to a variable number of genetically identifiable clones, showing allelic polymorphy. Examples of clearly polyclonal varieties are Cabernet franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Traminer, Riesling, Pinot noir, Chenin blanc, and Grolleau (Pelsy et al., 2010); Meunier (Franks et al., 2002; Stenkamp et al., 2009); Pinot gris, and Pinot blanc (Hocquigny et al., 2004); and Pinot noir and Chardonnay (Riaz et al., 2002). In addition, clonal divergence may also be derived polyzygotically (that is, where siblings are so morphologically similar as to be considered members of the same variety). A suspected example of a polyzygotic cultivar involves two lines of Fortana (Silvestroni et al., 1997). However, siblings are usually distinctly different, as indicated by the variety of cultivars derived from Gouais blanc×Pinot (Fig. 2.18). Additional sources of variation may arise if distinct clones are involved in multiple crosses (e.g., Pinot noir vs. Pinot blanc). Furthermore, differences can arise depending on which parent acted as the female – it being the sole origin of traits associated with chloroplast and mitochondrial2 genes.

The designation of a variant (accession), with a varietal or clonal designation, is partially subjective, depending on precedent (Boursiquot and This, 1999). If the variant is used in the sense of a subvariety, it is individually designated, for example the Musqué clone of Chardonnay. Alternatively, it may only be distinguished by a number, for example Riesling clones #239, #239-20, #239-12, and #110-1. However, if the variants make distinctly different wines, they usually go under separate but clearly related names, for example the color mutants of Pinot noir – Pinot gris and Pinot blanc. This is not a requirement, though, as some clones of Traminer used similarly possess distinct varietal designations (synonyms), e.g., Savagnin.

If the number of allelic variants can be used as a measure of cultivar age, then data from Pelsy et al. (2010) would suggest that Pinot noir and Traminer are ancient cultivars. This fits morphological attributes that give the impression that both are ancient and probably selections from wild or slightly domesticated vines. Their association as one of the parents of multiple other cultivars also supports their presumptive age. Nonetheless, based on the few accessions studied, the limited somatic diversity within Riesling clones (Pelsy et al., 2010) would be at variance with its presumptive ancient origin. However, the number of detected genotypes could easily vary, based on the number and appropriateness of the clones assessed. For example, in an investigation of 24 accessions of Traminer (Imazio et al., 2002), all were found to be genetically identical – a finding distinctly different from the observations of Pelsy et al. (2010). In addition, there is no evidence that the rate at which allelic SSR differences develop is constant, unlike point mutation rate which tends to be relatively constants over long periods of time (Drake, 1991). SSR differences appear to depend primarily on polymerase slippage, or the activity of transposons, not nucleotide substitutions induced by tautomeric shifts in the nitrogen bases that constitute primary structure of DNA.

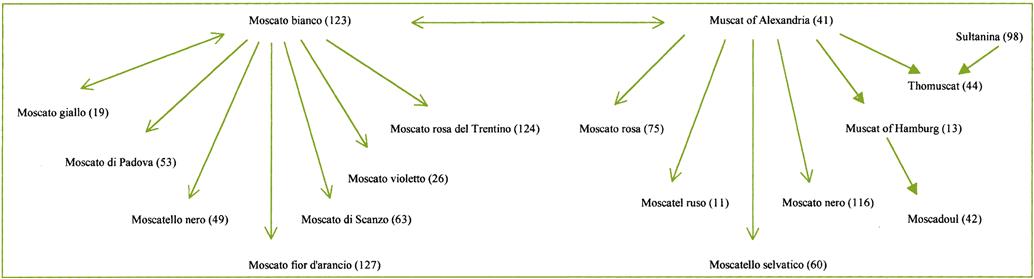

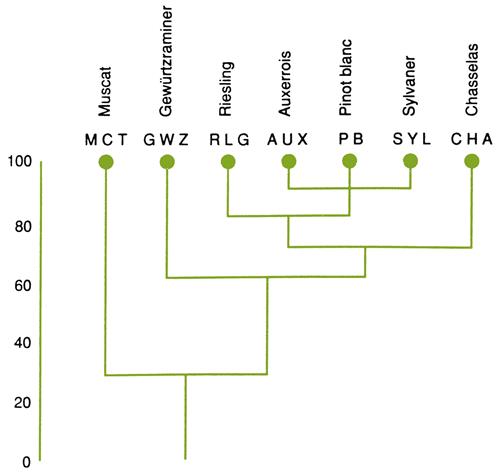

Another significant use of DNA fingerprinting has involved unraveling the often complex synonymy of cultivars. For example, Zinfandel in the United States is Primativo in Italy and Crljenak kaštelanski in Croatia (Maletiae et al., 2004). A related cultivar, Plavac mali, appears to be the progeny of a cross between another Croatian cultivar, Dobrièiae, and Crljenak kaštelanski (Zinfandel). Molecular analysis has also shown the synonymy between most Californian Petite Sirah and Durif (Meredith et al., 1999). Durif is itself the progeny of a crossing between Syrah and Peloursin. Sequence analysis has also permitted clarification of the interconnections among Muscat cultivars (Fig. 2.19).

Initially, sequencing techniques were thought to be independent of the tissues used – in contrast to isozymes and pigments, both of which are produced only in certain tissues or at particular developmental stages. However, tissue-specific DNA banding has now been identified (Donini et al., 1997). This is not overly surprising, due to the selective amplification or mutation of genes during tissue development. In addition, genetic differences found in chimeras may complicate patterns. Thus, some divergence in data interpretation among different research labs may originate from the tissues used for DNA extraction.

DNA fingerprinting has recently been applied to DNA isolated from seed (Manen et al., 2003) and other archaeological remains. Amplification has generated useful microsatellite markers from both waterlogged and charred seed (600 b.c. to 300 a.d.). DNA data are much more informative than seed morphology, which may suggest, but does not permit, the unambiguous differentiation between domesticated and wild vines. Although few useful markers have been obtained thus far, the data suggest that the specimens investigated are more closely related to varieties currently cultivated in regions where the seeds were isolated than to varieties cultivated elsewhere. These data are consistent with data noted earlier, suggesting that most European cultivars arose locally, rather than derived from elsewhere.

Regrettably, current DNA fingerprinting techniques involve markers of unknown genetic significance. For example, SSR markers appear to be located in sections of the genome other than the 4% that codes for functional (protein sequencing) genes (Lodhi and Reisch, 1995). The remaining DNA consists primarily of variously repeated segments of unknown function, transposon copies, gene regulator sections, and nonfunctional (null or pseudo-) genes. Thus, SSR relationships may have no phenotypically (selective) value. It is a moot point whether it would be preferable if relationships were based on evolutionary (ecologically) significant properties (structural genes), somewhat similar to taxonomic studies, or, as currently, on random changes in selectively neutral segments of the genome (see Jones and Brown, 2000).

Recorded Cultivar Development

Until little more than a century ago, deliberate attempts to develop new cultivars were limited (or at least unrecorded). Some of the earliest examples of suspected crosses occurred between indigenous Vitis spp. and V. vinifera cultivars planted in New England. Concord and Ives are thought to be chance crossings between V. labrusca and V. vinifera. Support for this view is provided by the presence of the Gret1 retrotransposon in several New England cultivars, including Concord (Mitani et al., 2009). This genetic insert is found in most V. vinifera cultivars, but not in North American and Asian Vitis spp. Another likely progeny of a chance crossing is Delaware – this time among three species (V. vinifera, V. labrusca, and V. aestivalis).

In contrast, Dutchess is thought to be the offspring of an intentional crossing between V. labrusca and V. vinifera. Other V. labrusca cultivars, such as Catawba and Isabella, are considered to be straight selections from local V. labrusca strains. Aside from V. labrusca, the involvement of native North American species in indigenous North American cultivars is limited. Exceptions include Noah and Clinton (V. labrusca×V. riparia), Herbemont and Lenoir (V. aestivalis×V. cinerea×V. vinifera), and Cynthiana and Norton (likely V. vinifera×V. aestivalis) (Stover et al., 2009). These early cultivars are termed American hybrids, to distinguish them from hybrids developed in France between V. vinifera and one or more of V. rupestris, V. riparia, and V. aestivalis var. lincecumii accessions. The latter are variously termed French-American hybrids, French hybrids, or direct producers. The last designation comes from their ability to grow ungrafted in phylloxera-infested soils. Some French-American hybrids are of highly complex parentage, based on subsequent backcrossing with one or more V. vinifera cultivars. Backcrossing was used to enhance the expression of vinifera-like winemaking qualities in the progeny. The relatedness of many of these cultivars has been studied by Pollefeys and Bousquet (2003).

The original aim of most French breeders was to develop cultivars containing the wine-producing attributes of V. vinifera and the phylloxera resistance of American species. It was hoped that this would avoid the expense and problems associated with grafting existing vinifera cultivars to American rootstocks. Grafting was the only effective control against the devastation being inflicted by phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae). It also was hoped that breeding would incorporate resistance to other nonindigenous pathogens, notably powdery and downy mildew. More by accident than design, several of the hybrids proved more productive than pure vinifera cultivars. They became so popular with grape growers that by 1955 about one-third of French vineyards were planted with French-American hybrids. This success, and their different aromatic character, came to be viewed as a threat to the established reputation of viticultural regions, such as Bordeaux and Burgundy. The pressure for political action culminated in the enactment of laws intended to restrict and then eliminate their cultivation. Subsequently, similar legislation has been passed in other European countries.

Although largely rejected in the land of their origin, French-American hybrids have found broad acceptance in many northeastern regions of North America. They initially helped foster wine production in much of the continent, outside of California, and generated regionally distinctive wines. They are still thus used in regions where vinifera survival is tenuous. French-American hybrids are also grown extensively in some other parts of the world, notably Brazil and Japan.

In the coastal plains of the southeastern United States, commercial viticulture is based primarily on selections of Vitis rotundifolia var. rotundifolia. Scuppernong is the most widely known cultivar, but has the disadvantage of being unisexual. Newer cultivars such as Noble, Magnolia, and Carlos are bisexual, and so avoid the necessity of interplanting male vines to achieve adequate fruit set. Another complication of muscadine cultivars is the tendency of berries to separate (shatter) from the cluster as they ripen. Newer cultivars such as Fry and Pride show less tendency to shatter. In addition, ethephon (2-chloroethyl phosphonic acid) application can promote more uniform ripening. The resistance of muscadine grapes to most indigenous diseases and pests in the southern United States has permitted a local wine industry to develop, where the commercial cultivation of V. vinifera cultivars is difficult to impossible. Although Pierce’s disease has limited the cultivation of most nonmuscadine cultivars in the region, the varieties Herbemont, Lenoir, and Conquistador are exceptions. The first two are thought to be natural V. aestivalis×V. cinerea×V. vinifera hybrids, whereas Conquistador is a complex cross involving several local Vitis spp. and V. vinifera.

Although grafting prevented the demise of grape growing and winemaking in Europe during the late 1800s, early rootstock cultivars created their own problems. Most of the initial rootstock varieties were direct accessions of V. riparia or V. rupestris. As most were poorly adapted to the high-calcium soils found in many European regions, the incidence of lime-induced chlorosis increased markedly. Nevertheless, stock from both species rooted easily, grafted well, and were relatively phylloxera-tolerant. Vitis riparia rootstocks also provided some cold-hardiness, resistance to coulure (unusually poor fruit set), restricted vigor on deep rich soils, and favored early fruit maturity. In contrast, V. rupestris selections showed acceptable resistance to lime-induced chlorosis and tended to root deeply. Although the latter provided some drought tolerance on deep soils, these rootstocks were unsuitable on shallow soils.

The problems associated with early named rootstock selections, such as Gloire de Montpellier and St. George, led to the breeding of new hybrid rootstocks (Fig. 2.20), incorporating properties from several Vitis species. For example, V. cinerea var. helleri (V. berlandieri) can donate resistance to lime-induced chlorosis; V.×champinii can supply tolerance to root-knot nematodes; and V. vulpina (V. cordifolia) can provide drought tolerance under shallow soil conditions. Alone, however, these species have major drawbacks as rootstocks. Both V. cinerea var. helleri (V. berlandieri) and V. vulpina root with difficulty; V. mustangensis (V. candicans) has only moderate resistance to phylloxera; and both V. mustangensis and V. vulpina are susceptible to lime-induced chlorosis. Important cultural properties of some of the more widely planted rootstocks are given in Tables 4.6 and 4.7.

=interspecies crossings. The Champin varieties, Dog Ridge and Salt Creek (Ramsey), are considered to be either natural V. mustangensis×V. rupestris hybrids, or strains of V.×champinii. Solonis is considered by some authorities to be a selection of V. acerifolia (V. longii), rather than a V. riparia×V. mustangensis hybrid. On this basis, some multiple-species hybrids noted above are bihybrids. (Modified from Pongrácz, 1983, reproduced by permission.)

=interspecies crossings. The Champin varieties, Dog Ridge and Salt Creek (Ramsey), are considered to be either natural V. mustangensis×V. rupestris hybrids, or strains of V.×champinii. Solonis is considered by some authorities to be a selection of V. acerifolia (V. longii), rather than a V. riparia×V. mustangensis hybrid. On this basis, some multiple-species hybrids noted above are bihybrids. (Modified from Pongrácz, 1983, reproduced by permission.)Grapevine Improvement

As with other perennial plants, and especially due to the small size and minor morphologic differences between the chromosomes (see Fig. 2.5), little data on the genetic properties of Vitis had accumulated. This gap is now being filled by genome sequence analysis (Jaillon et al., 2007; Velasco et al., 2007). Figure 2.21 represents the Vitis genome, noting the chromosomal location of many genes. It is estimated that the Vitis genome contains some 30,000 protein-coding genes. Preliminary data suggest that as many as 13% of the genes are heterozygous (Velasco et al., 2007). In addition, grapevines possess an abnormally high number of isogenes. For example, there are 43 stilbene synthase, 89 functional terpene synthase, and two geranyl diphosphate synthase genes (more than twice as many as most other plants) (Jaillon et al., 2007). These genes are particularly important to grapevine health and flavor characteristics. Stilbene synthases are involved in the production of resveratrol and other antimicrobial phytoalexins; terpene synthases are responsible for the production of aromatic terpenes; and geranyl diphosphate synthases are critical in the production of terpene progenitors. Knowledge of the location of genes should facilitate varietal improvement using marker-assisted breeding (Mackay et al., 2009). This could be particularly used in improving disease resistance.

Standard Breeding Techniques

The focus of most grape breeding has changed little since the early work of breeders such as F. Baco, A. Seibel, and B. Seyve (Neagu, 1968). Standard goals include improving the agronomic properties of rootstocks, and enhancing the viticultural and winemaking properties of fruit-bearing (scion) stock. The major changes involve the availability of modern analytical techniques and a better understanding of genetics. Such knowledge can dramatically increase a breeder’s effectiveness.

Of breeding programs, those developing new rootstocks are potentially the simplest. Improvement often involves enhancing properties, such as lime and drought tolerance or pest resistance. When one or a few genes are involved, incorporation may require only the crossing of a desirable variety with the source of the new trait, followed by selection of offspring possessing the trait(s) desired (Fig. 2.22A). Backcross breeding (Fig. 2.22B) can be particularly useful when integrating single dominant traits into an existing cultivar.

Developing new scion (fruit-bearing) varieties is far more complex. The repeated backcrossing, required to re-establish expression of desirable traits, may result in diminished seed viability and vine vigor, a phenomenon termed inbreeding depression. It occasionally can be countered if more than one cultivar can serve as a recurrent parent, or if embryo rescue is possible. Embryo rescue involves the isolation and cultivation of seedling embryos on culture media, which otherwise would abort during seed development (Spiegel-Roy et al., 1985; Agüero et al., 1995). Alternatively, inbreeding depression (Charlesworth and Willis, 2009) may be countered by treating germinating seeds with a demethylating agent, if recent findings on Scabiosa are confirmed in other plants (Pennisi, 2011). Gene inactivation is often associated with DNA methylation.

However, an even more intractable problem in breeding new grapevine scions is the highly heterozygous nature of most desirable traits (Plate 2.4). As a consequence, breeding tends to disrupt the complex balance that donates a variety’s desirable attributes. In addition, most of the properties associated with commercial success are quantitative, depending on the accumulative action of multiple genes, often located on separate chromosomes. Thus, the disruption of desirable combinations is particularly likely during recombination and the random assortment of chromosomes that occurs during meiosis. Gene reassortment also complicates the selection process, by blurring the distinction between environmentally and genetically induced variation.

The problem may be partially diminished if the genetic basis of the trait is known. For example, selection for cold-hardiness might be facilitated if the nature, location, and relative importance of the regulatory genetic loci were known. Individual aspects of this particular complex property involve diverse features, such as the control of cellular osmotic potential (timing and degree of starch/sugar interconversion), the unsaturated fatty-acid content of cellular membranes, and the population of ice-nucleating bacteria on leaf surfaces. This knowledge would permit each aspect to be individually assessed and selected for during breeding.

Chemical indicators and other genetically linked features are especially useful in the early selection of suitable offspring. The efficient and early elimination of undesirable progeny in a breeding program assures that precious time and resources are spent only on potentially useful offspring. For example, the presence of methyl anthranilate and other volatile esters was used in the early elimination of progeny possessing a labrusca fragrance (Fuleki, 1982). Improved knowledge of the factors associated with color stability in red wines would be helpful in the early selection of offspring possessing better color retention attributes. Selection for disease resistance would be both sped up and facilitated were this property assessable in seedling by a simple chemical test. Regrettably phytoalexin production and toxin resistance are often stage-specific and not necessarily adequately expressed in seedlings. In addition, laboratory trials frequently do not adequately simulate field conditions.

Another factor that can facilitate breeding is combining ability. This somewhat nebulous term refers to a strain’s relative success in breeding programs. Regrettably, combining ability is currently impossible to assess in advance. Its genetic basis is unknown. Nonetheless, it is suspected to be partially associated with the genetic difference between the parents. A possible example of combining ability may involve Gouais blanc and Pinot noir. Many important cultivars have them as their parents (see Fig. 2.18). Gouais blanc is suspected to be an ancient Croatian cultivar whereas Pinot noir is often viewed as a strain selected from wild vines, or introgressed strains retaining many feral characteristics.

Adding to the complexities of grape breeding is the time required for winemaking attributes to become assessable. Vines only begin to bear sufficient fruit for testing in their third year. Increasing the population of a potentially new cultivar to a point where features such as winemaking potential can be adequately evaluated can often take decades.

The length of a breeding program can, at least potentially, be shortened by inducing precocious flowering (Mullins and Rajasekaran, 1981). This especially applies to properties assessable with small fruit samples. Flowering can be induced within 4 weeks of seed germination, by the application of synthetic cytokinins such as benzyladenine or 6-(benzylamino)-9-(2-tetrahydropyranyl-9H). It induces tendrils to develop into flower clusters (Fig. 2.23). This shortens the interval between crosses. Generation cycling can be further condensed by exposing seed to peroxide and gibberellin, prior to chilling (Ellis et al., 1983). The treatment shortens the normally prolonged cold treatment required for seed germination. In theory, the combination of precocious flowering and shortened seed dormancy could reduce the generation time from 3–4 years to about 8 months. Inducing dormant cuttings to flower is another means of accelerating the breeding process. With a greenhouse, crossing is not limited by seasonal conditions, and could be conducted year-round.

Although clear indicators of gene expression are highly desirable, few agronomically important genetic traits are amenable to early detection. Assessing properties, such as winemaking quality, can easily extend beyond the career of an individual breeder. The long gestation period for generating new scion varieties is further complicated by consumer conservatism and regulatory intransigence. In Europe, most appellations rigidly limit cultivar use, effectively legislating against innovation. This automatically places new cultivars under legal and marketing constraints. Restrictions are even more severe when involving interspecies crosses, despite many hybrids possessing vinifera-like aromas (Becker, 1985). Correspondingly, incorporating new sources of disease and pest resistance into existing V. vinifera cultivars is essentially precluded using standard techniques. Although species other than V. vinifera are the primary sources of disease and pest resistance, untapped resistance may still exist within existing V. vinifera cultivars. For example, the offspring of a crossing between two Riesling clones (Arnsburger) showed resistance to Botrytis not apparent in either clonal progenitor (Becker and Konrad, 1990).

Despite North American Vitis species having been historically used as the primary source for new traits in grapevine breeding, Asian species, such as V. amurensis and V. armata, also possess desirable traits. For example, V. amurensis (and some strains of V. riparia) are potential sources of mildew and Botrytis resistance (along with V. armata in the latter case). In addition, V. amurensis and V. piasezkii (along with northern races of V. riparia) are valuable sources of cold-hardiness, early maturity, and resistance to coulure. For cultivation in subtropical and tropical regions, sources of disease and environmental stress resistance include V. aestivalis and V. shuttleworthii (from the southeastern United States and Mexico), V. caribaea (from Central America) (Jimenez and Ingalls, 1990), and V. davidii and V. pseudoreticulata (from southern China) (Fengqin et al., 1990).

Most interspecific hybridization has involved crossings within the subgenus Vitis. However, the production of partially fertile progeny between V. vinifera×V. rotundifolia is encouraging. Success is limited both by the inability of Vitis pollen to penetrate the style of muscadine grapes (Lu and Lamikanra, 1996), and the aneuploidy caused by unbalanced chromosome pairing during meiosis (Viljoen and Spies, 1995). Backcrossing to one of the parental species (usually the pollen source) has been used in several crops to restore fertility to interspecies hybrids. Although crossing bunch with muscadine grapes is far from simple, V. rotundifolia is the principal source of Pierce’s disease resistance, as well as resistance to downy and powdery mildew, anthracnose, black rot, and phylloxera; tolerance to root-knot and dagger nematodes; and enhanced heat insensitivity. Advances in vegetatively propagating V. vinifera×V. rotundifolia hybrids may enhance their commercial availability (Torregrosa and Bouquet, 1995) and adoption. Similar breeding programs could also introduce V. vinifera-like winemaking properties into muscadine cultivars.

Although most interspecies hybrids possess aromas distinct from those characteristic of V. vinifera cultivars, their aroma is not necessarily less enjoyable. Their distinctiveness could form the basis of regional wine styles. It was the regional distinctiveness of certain European wines that historically provided them with much of their appeal. There is no rational reason why this could or should not occur in North America or elsewhere. Regrettably, tradition-bound critics and many connoisseurs are inordinately opposed to change. Acceptable flavors seem to have become petrified with a few ‘premium’ cultivars. This situation limits the choice of wine flavors available to a new, and initially unbiased, generation of wine drinkers. It also restricts the spectrum of flavors available to all consumers. The associated boredom may be one of the root causes of stagnated wine sale worldwide.

Reticence to new sensory traits restricts the options in most grape-breeding programs. Traditional views demand that progeny (even of self-crosses) be given a new name. Thus, new cultivars lose the marketing advantage of their parents’ names. Most consumers are neophobic, generally viewing wines possessing unfamiliar names or places as inferior. This may also stem from new cultivars being relegated to regions where premium varieties do not grow profitably, or where increased yield or reduced production costs offset the loss of varietal-name recognition. The increasing popularity of ‘organically grown’ wines may enhance the acceptance and cultivation of new varieties. New cultivars often require less pesticide and fertilizer use than existing cultivars.

Modern Approaches to Vine Improvement