Grapevine Structure and Function

Grapevines are one of the more unique plants in terms of anatomy, morphology, and ontogeny. Coverage begins with the primary and secondary tissues of both young and old portions of the root and shoot systems, the foliage, tendrils, inflorescence, flower, fruit, and seed. Physiological coverage includes: root water and nutrient uptake; nutrient storage and transport; mycorrhizal involvement; photosynthetic and other light-activated processes, such as inflorescence induction; carbohydrate production and its seasonal movement throughout the plant; pollination; fertilization and its genetic control; chemical changes during berry maturation and the influences of cultural and climatic influences on its progress.

Keywords

grapevines; grapevine ontogeny; grapevine physiology; grapevine fertilization; grape maturation; climatic influences

Structure and Function

The uniqueness of many aspects of plant structure is obvious to even the most casual observer. However, some of the most distinctive and unique features become apparent only when viewed microscopically. Unlike animal cells, plant cells are enclosed in a rigid cell wall. Nevertheless, each cell initially possesses direct cytoplasmic connections with adjacent cells, through minuscule channels called plasmodesmata. Thus, embryonic plant tissue resembles a huge cell, divided into multiple, interconnected compartments, each possessing its own cytoplasm, organelles, and a single nucleus. As the cells differentiate, plasmodesmal and cytoplasmic organelles often deteriorate, and the cells specialize into functional but nonliving cells. The result is the plant begins to resemble layers of overlapping, longitudinal, semi-independent cones of specialized tissues.

Most conductive (vascular) cells elongate longitudinally, permitting the rapid movement of water and nutrients between superimposed sections of root and shoot tissue. In contrast, the conduction between adjacent cells is limited, occurring largely apoplastically (by diffusion through intercellular spaces). Direct translocation between tissues on opposite sides of shoots and roots is often nonexistent (except where vascular tissues do not elongate perfectly vertically). Spiraling of the vascular tissues can permit some indirect lateral translocation. Not only do the vascular tissues permit essential translocation between the shoot and root, but the xylem also provides the water essential for plant cooling. Thus, the physical characteristics of the vascular system place absolute limits on plant productivity and size that biochemical pathways cannot obviate or circumvent.

The vascular system in most plants consists of two structurally and functionally distinct components. The main water and mineral conducting elements, the xylem tracheae and tracheids, become functional on the disintegration of their cytoplasmic contents. Their empty lumens act as passive conduits. Loading and unloading functions appear to be under the control of adjacent, living, contact (parenchyma) cells. The primary cells translocating organic nutrients are the sieve tube elements of the phloem. They become functional when the nucleus disintegrates and the central vacuole disappears. Cytoplasmic organelles and clusters of proteins are appressed against the cell membrane. Metabolic control is thought to be associated with adjacent companion (parenchyma) cells. These retain their nucleus, central vacuole, and cytoplasm, which is packed with mitochondria, plastids, and other organelles (van Bel, 2003).

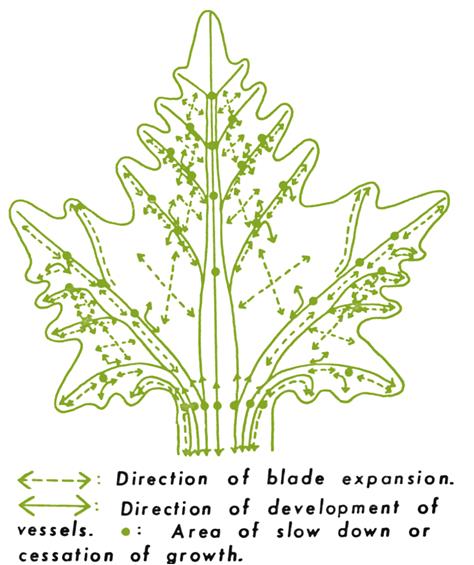

Vascular plants (such as the grapevine) also show a distinctive growth habit. Growth in length is primarily restricted to specialized embryonic (meristematic) cells, located in shoot and root tips. Growth in breadth is initially limited to that resulting from the enlargement of the cells produced in the shoot or root apices (primary tissues). Further growth in diameter occurs when a band of cells, the vascular cambium, differentiates between the phloem and xylem. As this lateral section of meristematic tissue becomes active, it produces cells both laterally (to the sides) and radially (to the inside and outside). Thus, as the vine grows, the shoots and roots increasingly resemble annually produced, superimposed, elongated, thin cones of secondary phloem and xylem, extending from root tips to shoot tips. The oldest (primary) phloem is located outermost and the oldest (primary) xylem located innermost. In addition, plants show distinctive growth patterns that generate leaves, and their evolutionary derivatives – flowers and tendrils, etc. In leaves and flowers, sites of growth (plate meristems) occur dispersed throughout the young leaf or flower part. Their nonuniform rates and patterns of growth generate the characteristic shape of the respective plant parts (see Fig. 3.13), and generate the patterns used in cultivar identification (ampelography).

The Root System

The root system possesses several cell types, tissues, and regions, each with their particular structure and function. It also consists of a series of root types: leader, fine lateral, and large permanent. Each possesses their particular function and relative life span. Thus, the root system works as a community of distinct but interconnected components, each contributing to the success of the whole.

The root tip performs many of the most significant root functions, such as water and inorganic nutrient uptake, synthesis of several growth regulators, and the elongation that pushes the root tip into regions untapped of their water and nutrient supplies. Not surprisingly, this region is the most physiologically active, and has the highest risk of early mortality (Anderson et al., 2003). In addition, the root tip is the site for the initiation of mycorrhizal associations, while secretions from the root cap soften the soil in advance of penetration. Root cap secretions also promote the development of a unique rhizosphere microbial flora, on and around the root tip. Older, mature portions of the root transport water and inorganic nutrients upward to the shoot system, and organic nutrients downward for storage, or to growing portions of the root. The outer, secondary tissues of the mature root restrict water and nutrient loss to the soil, and help protect the root from parasitic and mechanical injury. Permanent parts of the root system anchor the vine and act as a major storage organ during the winter (Yang et al., 1980; Zapata et al., 2001). Nutrient reserves decline during the winter and spring months, associated with root maintenance, and shoot and leaf production, respectively. Export to the shoot in the spring involves translocation via both the xylem and phloem (Glad et al., 1992a,b). Reserve accumulation commences after shoot growth slows in mid- to late-summer, reaching a peak in autumn. This may explain why roots produced before flowering have the shortest life span (due to the lowest carbohydrate reserve) (Anderson et al., 2003). Because of the significant differences in the structure and function of young and mature roots, they are discussed separately.

The Young Root

Structurally and functionally, the young root can be divided into several zones. The most apical is the root tip, containing the root cap and apical meristem (the metabolic ‘hot spot’ of the root system). The latter consist of cells that remain embryonic as well as those that differentiate into the primary tissues of the root. Primary tissues are defined as those that develop from apically located meristematic cells. Secondary tissues develop from laterally positioned meristematic tissues (cambia). The embryonic cells of the root tip are concentrated in the center of the meristematic zone, which was erroneously termed the quiescent (transition) zone. In addition, the region is a major site for the synthesis of certain growth regulators, notably cytokinin, abscisic acid, ethylene, and gibberellin. Their production is promoted by auxins translocated down from the shoot. In addition, auxins direct cell division, elongation, and differentiation in the root tip, as well as stimulate root hair initiation and development, as well as lateral root induction. Together, root- and shoot-derived regulators balance shoot vs. root growth. They also influence stomatal function (notably abscisic acid), inflorescence initiation, and fruit development. Hormonal interaction in plants is notoriously complex and site-specific, often depending on gradients established in different tissues of the shoot or root. An example is the ‘outside in’ auxin fountain developed by different PIN proteins in the inner and outer columns of the root tip (Baluška et al., 2010). Hormonal specificity also depends on the selective production of receptor proteins (e.g., Westfall et al., 2012).

Surrounding the permanently embryonic center of the transition zone are rapidly dividing cells, and their derivatives in early stages of differentiation. Cells positioned toward the apex develop into root-cap cells. These are short-lived and produce mucilaginous polysaccharides that ease root penetration into the soil. Internal (columella) cells respond to environmental signals and direct root growth. The different independent mechanisms by which gravitational, nutritional, thigmotropic, and moisture differentials are detected (Jaffe et al., 1985) may explain why primary (tap) roots grow downward, while secondary (lateral) roots initially grow outward. Their differential response to environmental signals leads to the three-dimensional, but primarily lateral, spread of the root system through the soil. In contrast, plant tissue polarity (shootward vs. rootward) is fixed early in embryogenesis. It is based on the orientation of a set of PIN proteins that remains stable. They take up a basal position that is perpetuated in all subsequent cells produced (Friml et al., 2006). PIN proteins direct the movement of auxins that establish apical dominance.

The cap also appears to cushion embryonic cells from physical damage during penetration into the soil. Laterally, cells differentiate into the epidermis, the hypodermis, and cortex, the latter consisting of several layers of undifferentiated parenchyma cells. Behind the apical meristem, vascular tissues begin to differentiate and elongate. Cell enlargement occurs primarily along the axis of root growth, and forces the extension of the root tip into the soil. This is primarily limited to a short (∼2 mm) region called the elongation zone. Except for some enlargement in cell diameter, most lateral root expansion results from the subsequent production of new (secondary) tissue behind the root apex.

Most newly generated cells complete their differentiation just behind the elongation zone. This is also the zone in which water and mineral absorption is most pronounced. Thus, the region is variously termed the differentiation or absorption zone. It is often about 10 cm in length. The next region is called the root-hair zone, due to the fine, cellular extensions (root hairs) that develop outward from epidermal covering. The formation, length, and life span of root hairs depend on many factors. For example, alkaline conditions suppress root-hair development, as does formation of a symbiotic association with mycorrhizal fungi. Root hairs increase root–soil contact and, thereby, potential water and mineral uptake. However, due to their absence or limited production under field conditions (McKenry, 1984), especially in mycorrhizal roots, their relative significance to water and nutrient uptake may have been exaggerated. Root hairs also release, and upon their decay, liberate organic nutrients into the soil, promoting further development of a unique microbial flora, initiated by root-cap secretions on and around the root. This may be particularly significant in deeper, organic, and nutrient-poor layers of the soil. The rhizosphere flora also helps protect the root from soil-borne pathogens, favors solubilization of inorganic soil nutrients, and may even assist in combating leaf pests and pathogens (Pineda et al., 2010).

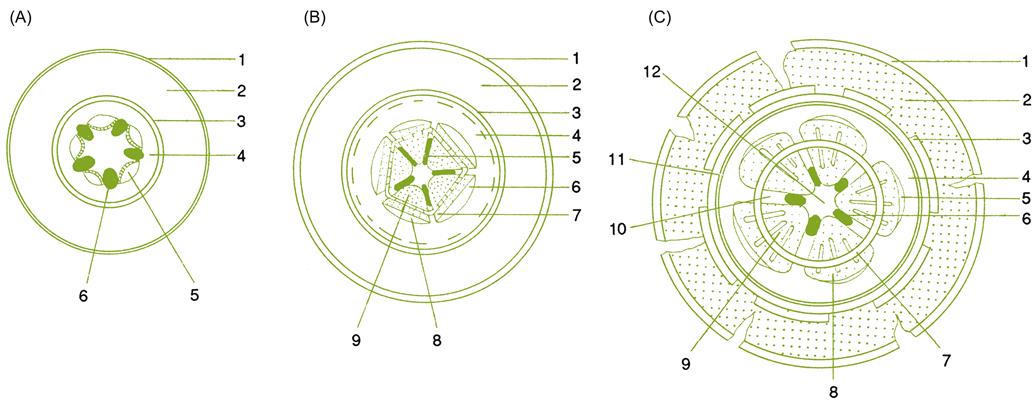

The first of the vascular tissues to differentiate is the phloem. Early phloem development facilitates the translocation of organic nutrients to the dividing and differentiating cells of the root tip. The xylem, involved in long-distance transport of water and inorganic nutrients, develops further back in the differentiation zone. This sequence probably evolved to avoid removing water and inorganic nutrients from the root tip. These compounds, locally absorbed, are required for the cell growth that typifies the region. The primary xylem and phloem cells mature in distinct packets, termed vascular bundles, separated by columns of undifferentiated parenchyma cells.

Adjacent to the primary xylem, and forming the innermost cortical layer, is the endodermis. The endodermis deposits a band of wax in, and lignin around, its radial walls, called the Casparian strip. This restricts the diffusion of water and nutrients between the cortex and vascular cylinder (via the nonliving space separating adjacent cells, primarily the cell walls). Thus, movement of water and nutrients between the cortex and vascular cylinder must pass through the cytoplasm of the endodermal cells. This gives the root metabolic control over transport into and out of the vascular tissues. Further back in the differentiation zone, the pericycle develops just inside of the endodermis. It generates a protective cork layer, if the root continues to grow and differentiate. The pericycle is also the site for the initiation of lateral root production.

Although still considered a major site for water and mineral uptake, the root-hair zone is no longer considered the only site involved. Behind the root-hair zone, the epidermis may soon die, turning brown. The underlying hypodermis becomes encased in waxy suberin. Suberization occurs rapidly during the summer and may advance to include the root tip under dry conditions (Pratt, 1974). The endodermis also thickens and becomes suberized behind the root tip. These changes reduce, but do not prevent, water uptake. The influence of suberization on mineral uptake depends on the ion involved, and the amount of wax in the suberin. Water and potassium uptake by heavily suberized, woody roots approximates 30 and 1–4%, respectively, of that absorbed by young unsuberized roots (Queen, 1968). In maturing sections of feeder roots (short-lived lateral roots), the cortical tissues collapse and the root becomes encased in cork, especially in dry soil. However, as only the inner wall surfaces of cork cells are suberized, and may be penetrated by plasmodesmata, diffusion routes for water and solutes through pores in the walls between adjacent cells are possible (Atkinson, 1980). This could be of considerable importance. As few feeder roots survive from one year to the next, most of the water and nutrient uptake in the early spring occurs via older, structural components of the root system. Feeder-root production may not reach its maximum until shoot growth has ceased.

The developmental and anatomical changes in root structure are reflected in a rapid decline in nitrate uptake and respiration along the root length. Nevertheless, the reduction in nitrogen uptake is more precipitous than would be expected, based solely on morphological changes. Volder et al. (2005) found that nitrate uptake declined by about 50% within 2 days of emergence, and fell to 10–20% within a few days. Uptake subsequently remained relatively constant for a month or more. Respiration followed a similar trend. These changes may owe their origin to rapid nitrate depletion in the immediate vicinity of the growing tip. In addition, development of the xylem and the initiation of nitrogen transport to other parts of the vine may also help explain the decline in net metabolic rate. Nutrient and water uptake is regulated by the activation, timing, and duration of new root production.

Root life span depends on multiple factors. These include the soil depth at which the roots formed, the timing of emergence, and their diameter. For example, fine lateral roots often remain viable for little more than 50 days, whereas deeper and coarser roots usually survive much longer (Anderson et al., 2003). McLean et al. (1992) obtained similar results, finding that no more than 60–80% of fine roots survive more than one season. Pruning treatment and grape yield also influence root longevity. For example, higher grape yields were correlated with reduced root viability, whereas roots of minimally pruned vines tended to remain metabolically active longer than those of balance-pruned vines (Comas et al., 2000).

Regardless of the site, soil-water uptake is induced by passive forces. In the spring, absorption and movement may be driven by the conversion of stored carbohydrates into soluble, osmotically active sugars. The negative osmotic potential produced generates what is termed root pressure in the xylem. Root pressure produces the ‘bleeding’ that occurs at the cut ends of spurs and canes in the spring. Once the leaves have expanded sufficiently, transpiration creates the negative vascular pressure (suction) that maintains the upward movement of water and inorganic nutrients throughout the remainder of the growing season.

Unlike water uptake, mineral uptake and unloading into the xylem is an active process, under the control of tightly appressed contact cells (parenchyma). Metabolic energy is also required for loading growth regulators synthesized in the root tip. Subsequently, movement appears to be passive, being carried along with the water flowing in the xylem. In contrast, organics compounds are seldom absorbed from the soil and translocated in the conducting elements of the root system. Exceptions include systemic fungicides and herbicides, and some microbial toxins and growth regulators. Xylem-inhabiting microbes may also be passively translocated in the transpiration stream.

Although essential to plant growth, the regulation of mineral uptake and nutrient loading into the xylem sap still remain poorly understood. For example, Mapfumo et al. (1994) discovered large lignified xylem vessels possessing protoplasm up to 22.5 cm back from the root tip. In several crops such cells have been found to be involved in potassium accumulation before transport (McCully, 1994). Whether this is true for grapevines is unknown. In addition, marked remobilization of stored Ca, K, Mg, Zn, and Fe can occur in the spring. Their movement out of the root seems dependent on xylem flow rate. In contrast, NH4, NO3, P, Cu, Na, and Cl movement appears to be independent of xylem flow rate (Campbell and Strother, 1996a, 1996b).

Mycorrhizal Association

An important factor influencing mineral uptake is the symbiotic association formed between the root and a mycorrhizal fungus. Grapevines are among the more than 80% of plant species that develop mycorrhizal associations. Plants with weedy tendencies are an interesting exception. Such plants depend on their ability to germinate and rapidly produce a fine root-hair system to establish a foothold in disturbed sites. In contrast, most plants grow more slowly and depend on mycorrhizal associations to exploit soil-water and nutrient reserves in their competition with other plants. Of the three major groups of mycorrhizal fungi, only vesicular–arbuscular fungi invade grapevine roots (Schubert et al., 1990).

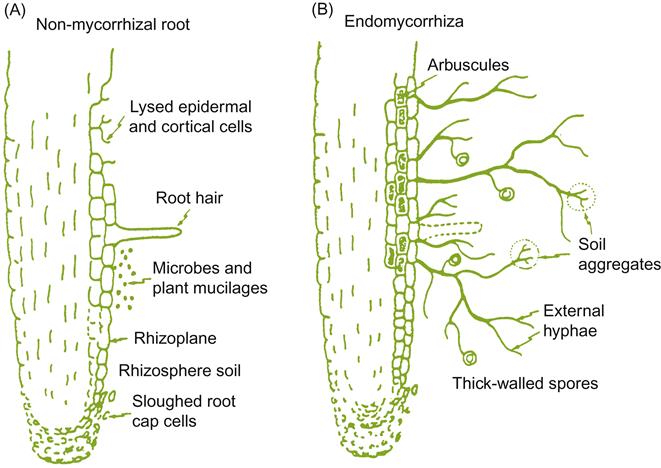

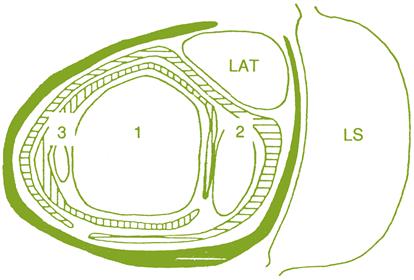

Species of Glomus are the primary vesicular–arbuscular fungi associated with grapevines, although Acaulospora, Gigaspora, Scutellospora, and Sclerocystis may occur. These fungi produce chlamydospores or sporocarps (containing many chlamydospores), from which infective hyphae invade the root epidermis. From this site, the fungus penetrates and colonizes the cortex. Here, the fungus produces large swollen vesicles and highly branched arbuscules, the two features that give these fungi their name. The fungi do not markedly alter root morphology, as other mycorrhizal associations tend to do (Fig. 3.1). Nonetheless, they do reduce root-hair formation, increase lateral root production, and promote dichotomous root branching. Invasion often results in the normally white root tip possessing a yellowish-brown cast and becoming misshapen. Although mycorrhizal invasion reduces root elongation and soil exploration, it produces a more economical root system for nutrient acquisition (Schellenbaum et al., 1991).

New mycorrhizal associations begin near the root tip, and advance apically as the root grows and produces new cortical tissue. Mycorrhizal activity declines and ceases rearward, as the root matures and the cortex is sloughed off. Mycorrhizal roots are strong sinks for plant carbohydrates, which may help explain why these roots tend to live longer than their nonmycorrhizal counterparts.

As the fungus establishes itself in the cortex, wefts of hyphae ramify into the surrounding soil, extending outward up to 2 cm. The hyphal extensions absorb and translocate water and minerals back to the root. Mycorrhizal fungi are more effective at mineral absorption than are root hairs. The high surface area to volume ratio of fungal hyphae, and their small diameter, also permit their penetration into more minute soil pores than root hairs. Mineral mobilization and uptake is further aided by the release of hydroxyamates (peptides), oxalate, citrate, and malate by the hyphae. The effectiveness of mycorrhizal hyphae in mineral uptake is particularly valuable with poorly soluble inorganic nutrients, such as phosphorus, zinc, and copper. Phosphorus is one of most immobile of essential soil nutrients, and its diffusion in dry soils may decline to 1–10% of that in moist soils.

Carbohydrates supplied by the vine sustain fungal growth. These are ‘exchanged’ for inorganic nutrients, notably phosphorus and ammonia, but also nickel, sulfur, manganese, boron, iron, zinc, copper, calcium and potassium. Mycorrhizal associations also provide the vine with some protection from the toxic effects of potential soil contaminants, notably lead and cadmium (Karagiannidis and Nikolaou, 2000).

The benefits of mycorrhizal associations are particularly noticeable in soils low in readily available nutrients, and under dryland-farming conditions. Under limiting growth conditions, the shoot conducts additional carbohydrates to the roots, which encourage not only mycorrhizal establishment but also development. In contrast, where access to inorganic nutrients is adequate, less carbohydrate is allocated to the roots, and mycorrhizal expansion is limited. Under drought conditions, mycorrhizal fungi augment water uptake and transport to the host, enhance stomatal conductance and transpiration, and accelerate recovery from stress (see Allen et al., 2003).

Both root and mycorrhizal exudates influence soil texture and the soil flora. These effects tend to be beneficial, partially due to the selective favoring of nitrogen-fixing and ethylene-synthesizing bacteria around the roots (Meyer and Linderman, 1986). These changes increase root resistance, or at least tolerance to fungal and nematode infections. For example, root inoculation with Glomus mosseae reduced the incidence of grapevine ‘replant disease’ in affected nursery soil (Waschkies et al., 1994). Mycorrhizal associations also tend to reduce vine sensitivity to salinity and mineral toxicities. By affecting the level of growth regulators, such as cytokinins, gibberellins, and ethylene, mycorrhizal fungi further influence vine growth. An additional, indirect effect may be the promotion of chelator production, such as catechols by soil bacteria. These help keep minerals, such as iron, in a biologically available form. Finally, mycorrhizae contribute to the formation of a stable soil-crumb structure.

In most vineyard soils, mycorrhizal associations arise spontaneously from naturally occurring soil inocula. Inoculation of cuttings in the nursery is often ineffectual, due to extensive rootlet mortality following transplantation (Conner and Thomas, 1981) and the presence of indigenous inocula. Specific inoculation tends to be of more value when vines are planted in fumigated soils, devoid of an indigenous population of vesicular–arbuscular fungi. Spontaneous infection is poorly understood, with spore populations tending to depend on the soil type, as well as soil cover (being higher on sandy soils and with a groundcover); is retarded by fungicidal applications; but is facilitated by the presence of a favorable rhizosphere flora. Soils low in available phosphorus encourage mycorrhizal establishment (Karagiannidis et al., 1997), whereas soils rich in nutrients limit its development. Differences in the incidence of colonization also occur among different rootstocks, usually being higher in cultivars that impart greater vigor to the scion. Nonetheless, these differences are small in comparison to factors such as crop load. Higher yield is associated with reduced numbers of roots with arbuscules (Schreiner, 2003), possibly due to a diminished translocation of carbohydrates to the roots.

Although mycorrhizal association is usually beneficial, there are situations where its formation may be ineffectual, for reasons poorly understood, or may have negative consequences. If phosphorus is seriously deficient, colonization by mycorrhizal fungi may not overcome the deficiency (Ryan et al., 2005). Under such conditions, metabolism of plant carbohydrates by the mycorrhizal fungus may reduce crop yield due to its ‘parasitic’ action. In addition, under some circumstances, mycorrhizae may increase the availability of, and thereby toxicity of, trace elements such as aluminum. Mycorrhizal fungi may also occasionally be associated with an increased incidence of lime-induced chlorosis (Biricolti et al., 1992).

Secondary Tissue Development

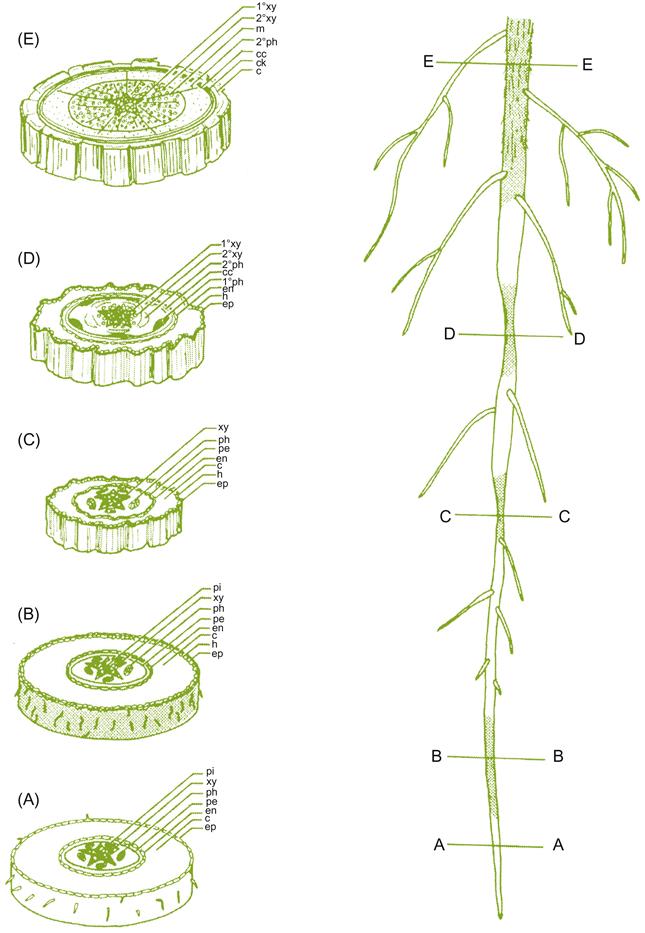

As noted, the epidermis and root cortex often become infected by mycorrhizal fungi. These tissues may also succumb to microbial and nematode attack. The latter may provoke the brown and collapsed regions commonly observed along otherwise healthy young roots. Regardless of health, the cortex and outer tissues soon die, especially if the central region of the root commences secondary (lateral) development (Fig. 3.2). Secondary growth includes the production of a band of cork (periderm) around the root, just inside the endodermis. Its formation restricts, and eventually cuts off, nutrient flow to the cortex and epidermis. Another lateral meristem (vascular cambium) develops as a circular band around the root, in the zone between the initial (primary) xylem and phloem. The cambium produces new (secondary) vascular tissues – xylem and phloem to the inside and outside of this band of meristematic tissue. The result is complete bands of xylem and phloem that encircle the root (Fig. 3.3). Periodically, cells produced in the vascular cambium differentiate into ray parenchyma, instead of xylem or phloem tissues. These cells elongate along the radial axis of the root, forming what are termed medullary rays. They facilitate water and nutrient exchange between contiguous regions of the phloem and xylem. As the root enlarges in diameter, new cork layers may develop in the secondary phloem, cutting off the older cork layers and nonfunctional phloem.

Root-System Development

In exploiting the soil for water and nutrients, the root system employs both extension and branching. Extension entails the rapid growth of thick leader roots into unoccupied soil, with the direction and extent of this growth being dependent as much on water availability, soil penetrability, vine density, and rootstock/scion combination as on geotropism (Seguin, 1972; McKenry, 1984). In favorable sites, many thin, highly branched, lateral roots develop from leader roots. Most of the lateral, feeder roots are short-lived and are replaced by new laterals. Thus, few laterals survive and become a part of the permanent structural framework of the root system. Large roots are retained much longer than most young roots, but are themselves subject to periodic abortion (McKenry, 1984).

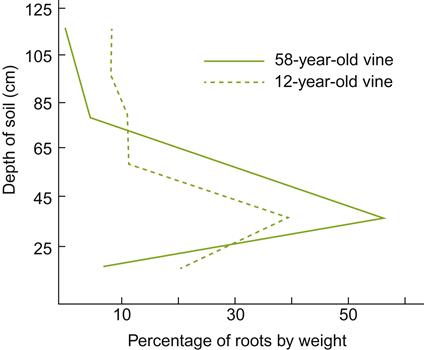

The largest roots generally develop within a zone about 0.3–0.35 m below ground level. Their number and distribution tend to stabilize a few years after planting (Fig. 3.4). From this basic framework, smaller permanent roots spread outward, with a restricted number angled downward. These, in turn, produce most of the short-lived feeder roots of the vine. Tentative evidence suggests that a ratio of fine to larger roots (<2 mm/>2 mm) greater than 3.5 indicates an effective root system (Archer and Hunter, 2005). This permits the vine to quickly take advantage of favorable conditions to fully mature the fruit.

Root-system expansion is dependent on both environmental and genetic factors. Spread may be limited by layers or regions of compacted soil, high water tables, or saline, mineral, and acidic zones. Thus, it is judicious that the soil be properly assessed and corrective measures taken, if necessary, before planting. Tillage, mulching, and irrigation favor the optimal positioning of major root development, but cannot offset unfavorable soil conditions. Increasing planting density tends to decrease root mass, but increases root density (roots per soil volume). Differences in the angle and depth of penetration vary with the genetic potentialities of the rootstock and rootstock–shoot interaction. For example, V. rupestris rootstocks are generally thought to sink their roots at a steeper angle and penetrate more deeply than V. riparia rootstocks, while the latter produce a shallower, more spreading root system (Bouard, 1980). However, an extensive review of the literature by Smart et al. (2006) suggests that local soil conditions are more significant than genetic factors in affecting root distribution.

Grapevine roots are characterized by their extensive colonization of the soil, principally horizontally, but at low rooting densities (Zapriagaeva, 1964). Grapevine roots commonly occupy only about 0.05% of the available soil volume (McKenry, 1984). Most root growth develops within a zone 4–8 m around the trunk. Depth of penetration varies widely, but is largely confined to the top 60–80 cm. Nevertheless, roots up to 1 cm in diameter can penetrate to a depth of more than 6 m. The tendency for deep penetration may reflect evolutionary pressures related to competition with the roots of trees on which they tended to climb. The finest roots, which do most of the absorption, generally occur within the uppermost 0.1–0.6 m. This portion of the root system may be located lower, depending on the depth of tilling, or the presence of a permanent sward. Conversely, mulches, or clean, no-till conditions allow root growth nearer the soil surface.

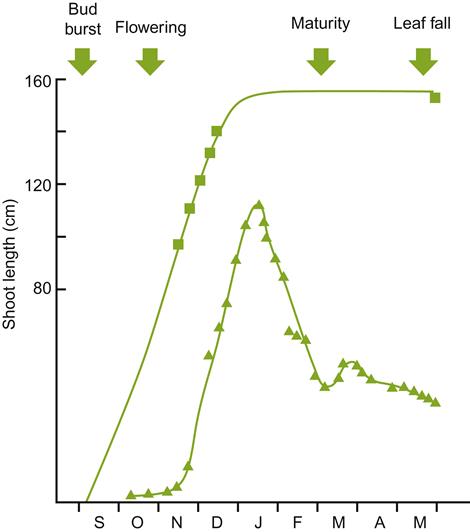

Unlike many woody perennials, the initiation of spring root growth lags significantly behind shoot growth. This may relate to the requirement for auxin translocation from germinating shoot buds. The latter occurs later than in most other perennial plants. Auxins are required to activate cytokinin synthesis in the root tip, which in turn stimulates root growth. Root production commences slowly after bud break, when soil temperatures rise above 6 °C (Khmelevskii, 1971). Mohr (1996) observed that root growth commenced slowly, occasionally reaching a peak only in late summer, whereas Comas et al. (2005) found root production reached a peak near mid-season (between bloom and véraison) (Fig. 3.5). Root production may closely follow canopy production, but is also significantly influenced by yearly climatic fluctuations (Comas et al., 2010). For example, restricted water availability tends to increase the root to shoot ratio (Hofäcker, 1976). Heavy pruning and delayed canopy development also affect root formation. A second, autumnal root-growth period may occur in warm climatic regions, where the postharvest growth period may be long (van Zyl and van Huyssteen, 1987). In contrast, root growth tends to be unimodal in temperate climates. Root production is most pronounced in years following high yields, when starch levels in the canes are low. Signs of root mortality appear to correspond with fruit development and ripening.

) and root growth (

) and root growth ( ) for the variety Shiraz grown in the Southern Hemisphere. (After Richards, 1983; from Freeman and Smart, 1976, reproduced by permission.)

) for the variety Shiraz grown in the Southern Hemisphere. (After Richards, 1983; from Freeman and Smart, 1976, reproduced by permission.)The effect of soil moisture on root production may be partially indirect, by affecting soil aeration and mechanical resistance. Some cultivars appear to be particularly sensitive to anaerobiosis, with oxygen tensions as low as 2% becoming toxic (Iwasaki, 1972). Waterlogging also enhances salt toxicity (West and Taylor, 1984). Furthermore, soil moisture content affects the rate at which soil warms in the spring, slowing the resumption of root growth, and the availability and movement of nutrients in the soil. Even relatively short periods of waterlogging (2 days) can significantly retard root growth (McLachlan et al., 1993). Root growth and distribution are also markedly influenced by soil cultivation, compaction, and irrigation.

The Shoot System

The shoot system of grapevines possesses an unusually complex developmental pattern. This complexity provides the vine with a remarkable ability to adjust its development throughout much of the growing season. It has also generated an equally complex terminology. Three or more successive sets of shoots may develop in a single year. In addition, dormant buds from previous seasons may become active. In recognition of this complexity, shoots may be designated according to their origin, age, position, or length. The buds, from which shoots arise, may also be identified relative to their position, germination sequence, or fertility.

Buds

All buds produced by grapevines may be classed as axillary buds. That is, they are formed in the axils of foliar leaves, or their modifications (bracts). Axils are defined as the positions along shoots where leaves develop. As such, axils are a part of a circular region of the stem called a node (see Fig. 2.1). Most structures that develop from shoots – leaves, buds, tendrils, and inflorescences – develop at nodes. The first two nodes of a shoot are very close, and subtend bracts. Only the subsequent nodes, which generate photosynthetic leaves, are usually considered when counting nodes on a shoot. These are frequently referred to as count nodes.

Most stem elongation occurs in the region separating adjacent nodes, the internodes. Buds occurring in the axils of bracts (leaves modified for bud protection) located at the base of mature canes are often termed base buds. They typically remain dormant. Buds of any kind that remain dormant for one or more seasons are usually referred to as latent buds. Depending on their location, latent buds may give rise to water sprouts or suckers (see Fig. 4.11), based on whether they originate above or below ground level.

Each node can potentially develop an axillary-bud complex, consisting of four buds on a very foreshortened shoot. These include the lateral (prompt or true axillary) bud, positioned to the dorsal side of the shoot, and a compound (latent) bud, which is positioned more ventrally (Fig. 3.6; Plate 3.1). The compound bud typically possesses three buds in differing states of development, referred to as the primary, secondary, and tertiary buds. In a notation system proposed by Bugnon and Bessis (1968), the shoot is termed N, the first (lateral) bud is denoted as N+1, the second (primary) bud is designated as N+2, and the third (secondary) and fourth (tertiary) buds are considered N+31 and N+32, respectively.

Depending on genetic and environmental factors, lateral buds may differentiate into shoots during the season in which they are produced. More commonly, they remain dormant, becoming latent buds. Shoots developing from lateral buds (N+1) in the year of their formation are termed lateral (summer) shoots.

There is considerable dissension among grape growers on whether to retain, trim, or remove lateral shoots. Initially lateral shoots act as a drain on vine photosynthate. However, later they can act as net carbohydrate exporters – when possessing two or more fully expanded leaves (Hale and Weaver, 1962). Lateral shoots (especially those that terminate their growth in mid-season) can benefit fruit ripening (Candolfi-Vasconcelos and Koblet, 1990), but may reduce fruit set earlier in the season (Vasconcelos and Castagnoli, 2000). These divergent effects may be explained by the relative maturity of the leaves at different stages during fruit production. In vigorous vines, lateral shoots can lead to dense canopies, generating excessive shading, reducing fruit quality, and enhancing disease susceptibility. Nonetheless, moderate shading can be beneficial in very sunny climates, as well as modifying fruit flavors in ways that may suit particular wine styles. In addition, fruit-bearing lateral shoots may produce what is called a ‘second’ crop. In most vinifera cultivars, lateral buds typically remain dormant, unless damage or early pruning of the shoot tip removes the source of auxins that promote their dormancy. Lateral buds in other Vitis spp. and French-American hybrids are more likely to germinate during the growing season. Secondary lateral buds, formed in the leaf axils of lateral shoots, also possess the potential to develop during the current year. If they do, they may generate a second series of lateral shoots.

The primary (N+2) bud of a compound bud develops in the axil of the bract (prophyll) produced by the lateral bud (N+1). Secondary and tertiary buds develop in the axils of the bracts produced by the primary and secondary buds, respectively. All three buds typically remain inactive during the growing season in which they develop, unless severe summer pruning removes apical (auxin-induced) dormancy. Subsequently, the compound bud develops endogenous (self-imposed) dormancy by autumn. By this time the compound bud is referred to as a dormant bud (‘eye’).

Concurrent with the development of endogenous dormancy, bud moisture content declines, from about 80 to 50%, starch grains become prominent, signs of mitosis disappear, catalase activity declines, and respiration falls to its lowest level (Pouget, 1963). The sequence of steps by which dormancy establishes itself is still unclear, but it is associated with an increase in the content of cis-abscisic acid (Koussa et al., 1994), and the production of a particular set of glycoproteins (Salzman et al., 1996).

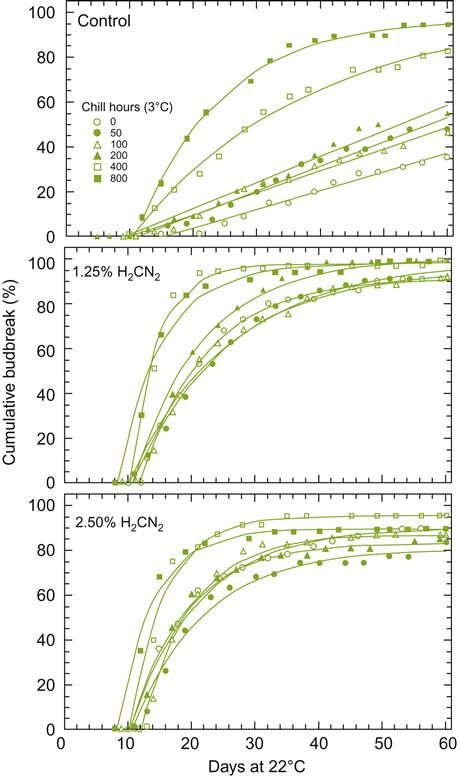

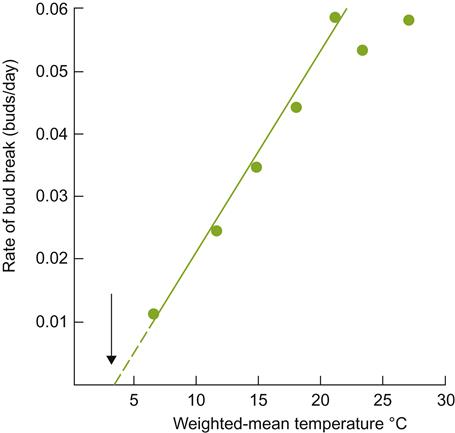

Release from dormancy typically requires exposure to low temperatures (Fig. 3.7). In temperate zones, this may commence in late fall and finishes during the winter months. Although the biochemical processes involved are unknown, they appear to involve an increase in hydrogen peroxide production, and the development of oxidative stress associated with low levels of catalase. This is consistent with the action of hydrogen cyanamide. It may be applied in situations where early bud break is desired (Lavee and May, 1997; Fig. 3.7). Hydrogen cyanamide depresses transcription of the catalase gene (Or et al., 2002). Hydrogen cyanamide application is also associated with the activation of genes that produce a dormancy-breaking protein kinase (GDBRPK), and genes producing pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase in buds (Or et al., 2000). This may accrue partially through an increased availability of NADH (Pérez et al., 2008). In tropical and subtropical regions, severe pruning usually can induce premature bud break. However, this treatment is more effective and uniform if combined with hydrogen cyanamide application. Garlic extract may be substituted, but is less effective (Botelho et al., 2007). Sublethal heat shock can also facilitate bud break under greenhouse conditions, and is being investigated for vineyard application (Halaly et al., 2011).

Assuming that the primary buds are not destroyed by freezing temperatures, insect damage, or pathogenic or physiological disturbances, they generate the primary shoots (major shoot system) of each year’s growth. The secondary and tertiary buds become active only if the primary and secondary buds, respectively, die.

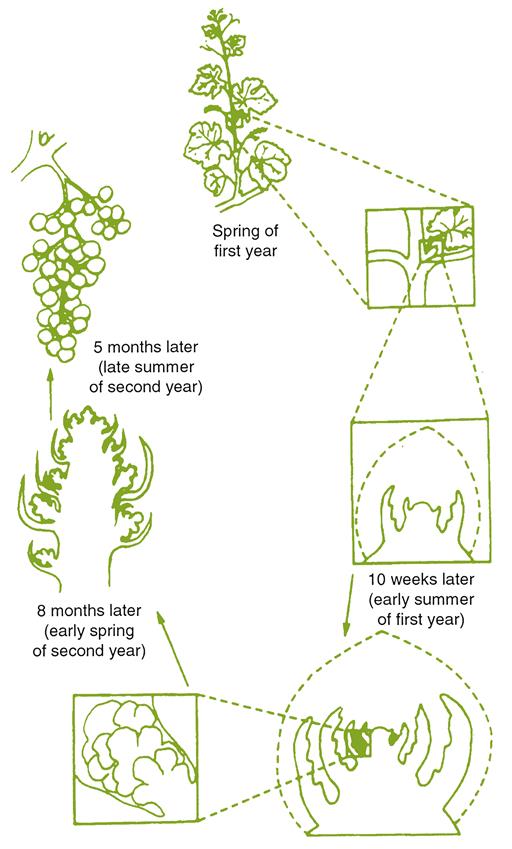

The primary bud is the most developed in the compound bud. It usually possesses several primordial (embryonic) leaves, inflorescences, and lateral buds before becoming dormant at the end of the growing season (Morrison, 1991). The secondary bud occasionally is fertile, but the tertiary bud is typically infertile (does not bear inflorescences). The degree of inflorescence differentiation, prior to the onset of dormancy, is a function of the genetic characteristics of the cultivar, vigor of the rootstock, bud location, and the immediate surrounding environment during bud formation.

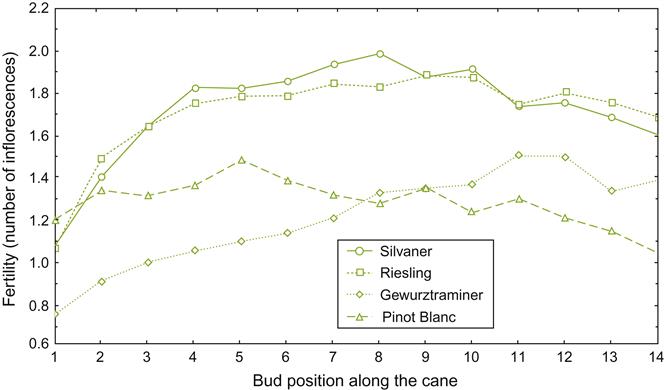

Buds that bear nascent (primordial) inflorescences are designated as fruit (fertile) buds to differentiate them from those that do not. The latter are referred to as leaf (sterile) buds. In most V. vinifera cultivars, fruit buds form with increasing frequency, distal to the basal leaf, often reaching a peak between the fourth and tenth nodes. However, this property varies considerably among cultivars (Fig. 3.8). Some cultivars, such as Nebbiolo, do not form fruit buds at the base of the shoot. Such cultivars are not spur-pruned, as this would drastically limit fruit production. Bud fruitfulness also influences pruning procedures. For example, the production of small fruit clusters by Pinot noir usually requires the retention of many buds on long canes.

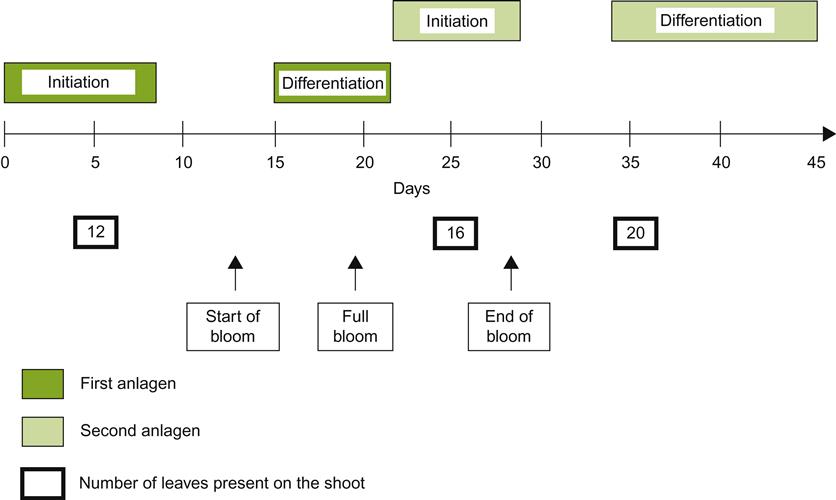

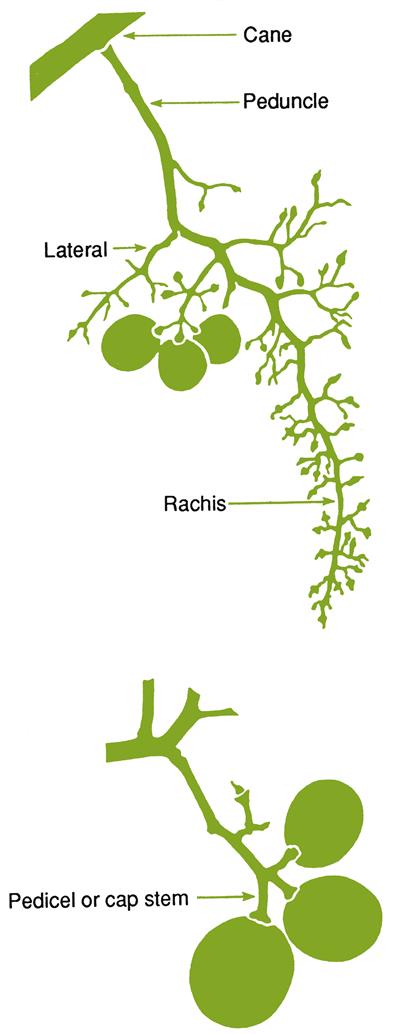

Shoots generally produce two (one to four) flower clusters per shoot. Flower clusters usually differentiate opposite the third and fourth, fourth and fifth, or fifth and sixth leaves on a shoot. Although inflorescence number and position are predominantly scion characteristics, they may be modified by hormonal signals coming from the rootstock (see Richards, 1983).

Shoots and Shoot Growth

Components of the shoot system obtain their names from the type and position of the buds from which they are derived, as well as their age, position, and relative length (see Fig. 4.11). Once the outer photosynthetic, subepidermal tissues degenerate, turning brown by the end of the season, the shoot comes to be referred to as a cane (if left long) or a spur (if short – pruned to possess only a few buds). Canes retained for 2 years or more, and supporting fruiting wood (spurs or canes) are called arms. When arms are positioned horizontally, they are referred to as cordons. The trunk is the major permanent upright structure of the vine. When they are old and thick, trunks no longer need support. Nevertheless, most vines require trellising to support the arms, canes, and growing shoots of the vine. All stem tissue 2 or more years old can be designated ‘old wood.’

Shoot growth is controlled primarily by environmental factors. Because there are no terminal buds, growth could theoretically continue as long as climatic conditions permitted. This growth habit, termed indeterminant, is much more characteristic of tropical than temperate woody plants. Shoot growth is favored by warm conditions, especially warm nights. Low-light conditions promote shoot elongation, but are detrimental to inflorescence induction. Genetic factors, probably acting through hormone production, generate the distinctive growth patterns typical of various cultivars. These tendencies can be modified by pruning and other cultural practices. For example, minimal pruning induces more, but shorter, thinner shoots.

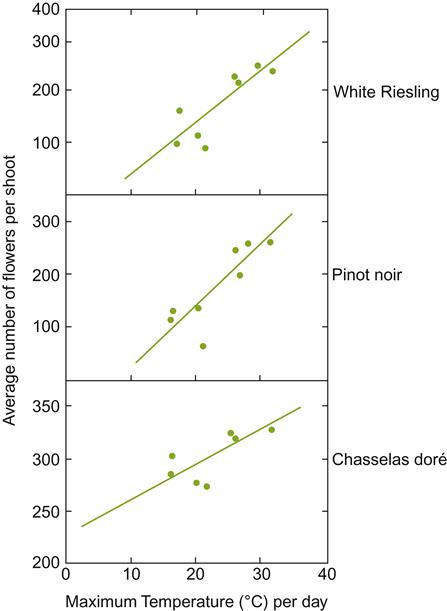

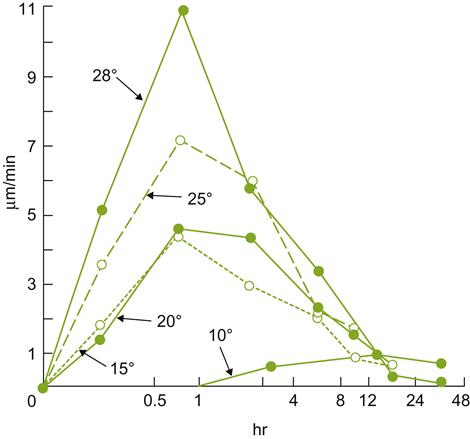

Bud break and shoot growth have generally been thought to begin when the mean daily temperature reaches>10 °C, following the loss of endogenous dormancy. However, bud break in some varieties may commence at temperatures as low as 0.4 °C (average 3.5 °C), and leaf production may begin at 5 °C (average 7 °C) (Moncur et al., 1989). The rate of bud break and shoot growth increases rapidly above the minimum temperature (Fig. 3.9). Once initiated, growth quickly reaches a maximum, after which growth progressively slows and may cease. Further shoot growth during the summer generally originates from the activation of lateral buds.

The slow initiation of growth in the spring, and the potential for lateral shoot growth throughout the season, probably reflect the ancestral growth habit of the vine. Slow bud activation would have delayed leaf production until its supporting tree had completed most of its foliage production. Thus, the vine could position its leaves, relative to the foliage of the host, in locations optimally suited for vine photosynthesis. In eastern North America, growth can be sufficiently rampant to result in the death of the host tree (Plate 3.2). In addition, the potential to generate several series of lateral shoots allows the vine to position new leaves in favorable sites, when and where as necessary.

Older portions of the vine provide the support and translocation needs of the growing shoots, leaves, and fruit. The woody parts of the vine constitute the majority of its structure. Mature wood also acts as a significant storage organ, thereby helping to cushion the effects of unfavorable growth conditions on fruit production during any one season. These reserves also tend to increase average vine productivity. Berry sugar content and pH increase slightly, relative to the portion of old wood (Koblet et al., 1994). In addition, increased berry aroma and fruit flavor have been correlated with vine age (Heymann and Noble, 1987), or with the proportion of old wood (Reynolds et al., 1994). Whether these associations are direct, or due to indirect effects of age-related reduced vigor, is unknown.

Shoot growth early in the season depends primarily on previously stored nutrients in the vine’s woody parts (May, 1987). Nitrogen mobilization and translocation to the buds initiates in the canes, and progresses downward, successively into older parts of the trunk, finally reaching the roots (Conradie, 1991b). Significant mobilization and translocation of nutrient reserves from the older structures of the vine to the developing fruit may also occur following véraison (the onset of color change in the fruit). The vine stores organic nutrients, primarily as starch and arginine, as well as inorganic nutrients, such as potassium, phosphorus, zinc, and iron. The movement of nutrients, such as nitrogen, downward, and into woody parts of the vine, probably occurs throughout the growing season, but is most marked after fruit ripening (Conradie, 1990, 1991a). It appears that some of the first nutrients mobilized in the spring are those last stored in the fall.

Although shoot growth can continue into the fall, this is usually undesirable. Not only is shoot maturation delayed and bud survival reduced, but it also draws nutrients away from the ripening fruit. Ideally, shoot growth termination should correlate with the onset of véraison. Various procedures may be used to promote this termination. These may include inducing limited water deficit, trimming the shoot tips, or the use of devigorating rootstocks. In hot Mediterranean climates, shoot growth may terminate shortly after flowering, when little more than a meter long. In contrast, vigorous shoots can grow to more than 4 m.

Tissue Development

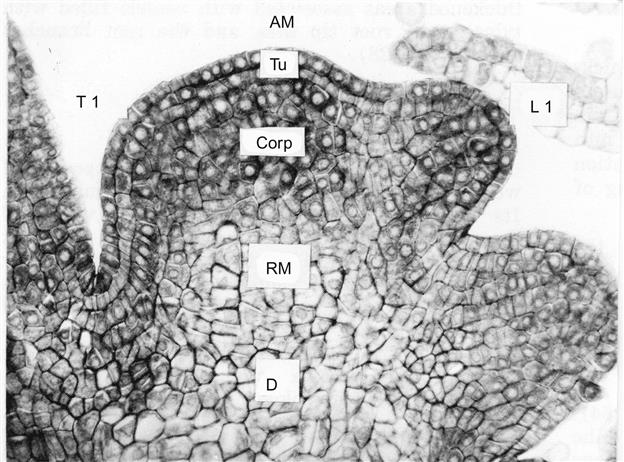

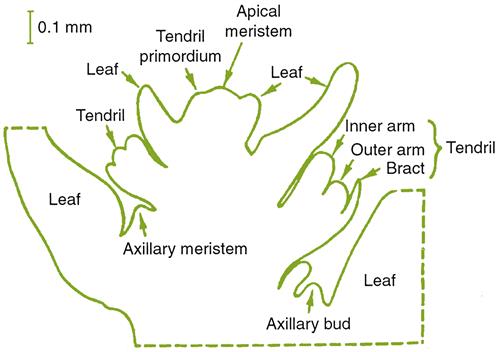

Shoot growth develops from an apical meristem that consists of two layers of ill-defined tunica cells, covering an inner collection of corpus cells (Morrison, 1991; Fig. 3.10). The outer layers produce the epidermal tissues of the stem, leaves, tendrils, flowers, and fruit, as well as initiating the development of leaf and flower primordia. The corpus generates the inner tissues of the shoot and associated organs. The shoot apex, unlike its root equivalent, has a highly compressed, complex morphology. Buds, leaves, tendrils, and flower clusters all begin their development within a few millimeters of the apex (Fig. 3.11). Subsequent cell division, differentiation, enlargement, and elongation produce the mature structures of each organ.

Branching of the vascular tissues into the leaves and other subtended organs, called traces, are equally complex in derivation. In leaves, four to eight leaf traces diverge from the vascular cylinder well below the leaf itself. The traces may fuse (anastomose) prior to entering the petiole. They give rise to the main veins of the leaves. Their subsequent division gives rise to their often varietally distinctive venation pattern. Not only do they provide some physical structure, but they also translocate nutrients to and from the developing leaves, flowers, fruit, etc.

As in the root, phloem is the first vascular tissue to differentiate in the shoot. The need for organic nutrients by the rapidly dividing apical cells undoubtedly explains the rationale for this morphogenic sequence. Cell elongation, which primarily entails water uptake, occurs later. Thus, xylem differentiation can be delayed and occurs further back. Early xylem development could also complicate shoot elongation. Even then, the first vessels to develop possess only partial (annular or spiral) secondary wall thickening. This allows for some vessel elongation, by stretching areas consisting primarily of the more flexible primary cell wall. Full, secondary, pitted and lignified thickening occurs only where elongation has ceased. In contrast, the earliest, thin-walled phloem cells are destroyed as the cells in the shoot tip elongate. New phloem sieve tubes differentiate to replace those destroyed by early cell elongation.

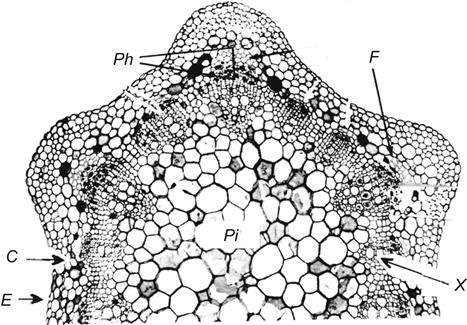

The outer tissues of the young stem consist of a layer of epidermis and several layers of cortical cells (Fig. 3.12). The epidermis is initially photosynthetic and bears stomata, hair cells, and pearl glands, especially adjacent to where vascular bundles differentiate. Most young cortical cells also contain chloroplasts and are photosynthetic. Nonetheless, the cortex tends to function more as a temporary storage tissue, notably for carbohydrates (primarily as starch), but also proteins. The innermost layer is distinguished by possessing large starch granules, and is termed the starch sheath. Collections of cortical cells, with especially thickened side walls, termed collenchyma, differentiate opposite the vascular bundles. These regions generate the ridges (ribs) of the young shoot. The region, internal to the zone where vascular bundles develop, is termed the pith. It consists of relatively undifferentiated parenchyma cells. These become increasing large toward the center.

When cell elongation ceases, a band of cells between the phloem and xylem begins to differentiate into a lateral meristem, the vascular cambium. It generates the secondary vascular and ray tissues of the maturing stem (Plate 3.3). The secondary phloem, similar to the primary, consists of translocating cells (sieve tubes), companion cells, fibers, and storage parenchyma. The secondary xylem consists of tracheids and larger diameter, thickened, xylem vessels, as well as structural fibers and parenchyma cells. Ray cells elongate horizontally, along the stem radius, and transport nutrients between the xylem and phloem. In the phloem, ray tissue expands laterally to form V-shaped segments (Plate 3.3). These cells store starch, along with xylem parenchyma. As secondary phloem and xylem accumulate, the vascular bundles take on the appearance of elongated lenses in cross-section. The innermost stem tissue, the pith, consists predominantly of thin-walled parenchyma cells. In species belonging to the subgenus Vitis, the pith soon disintegrates in all but the nodal region, where it develops into the woody diaphragm (see Fig. 2.3A).

Environmental conditions during growth can significantly affect xylem development. For example, leaf shading (Schultz and Matthews, 1993) and water deficit (Lovisolo and Schubert, 1998) slow growth, possibly as a consequence of reduced water conductance and disrupted hormonal movement. Positioning shoots downward also reduces vessel diameter, while increasing their number (Schubert et al., 1999). This influence has occasionally been used to reduce vine vigor. The effects of shoot orientation on water conductance appear to be related to increased auxin levels (Lovisolo et al., 2002). This promotes vessel division, but limits expansion. Smaller diameter vessels increase resistance to water flow, but reduce the likelihood of embolism (the formation of gas pockets in vessels that disrupts water flow). Cultivars differ markedly in their susceptibility of embolism (Alsina et al., 2007). Nonetheless, the significant given embolism in the past may have been exaggerated. In some plants, it is a normal and daily occurrence, reabsorbing shortly after forming, despite the water column still being under negative water potentials (McCully, 1999).

During shoot maturation, a layer of parenchyma cells in the phloem differentiates into a cork cambium (phellogen) (Plate 3.4). The cork (periderm) produced prevents nutrient and water supplies from reaching the outer tissues (mostly cortex and epidermis). These tissues subsequently die, begin to slough off, and create the brown appearance of maturing shoots.

In most regions, with the probable exception of the tropics, the end walls (sieve plates) of the sieve tubes become plugged with callose in the autumn, terminating translocation of organic nutrients. This occurs as the leaves die and are shed.

When buds become active in the spring, phloem cells in the cane and older wood progressively regain their ability to translocate. Activation progresses longitudinally up and down the cane from each bud, and outward from the vascular cambium (Aloni and Peterson, 1991). The rootward movement of auxins, produced by newly emerging leaves, appears to stimulate callose breakdown (Aloni et al., 1991). Although cambial reactivation is also associated with bud activation, it shows marked apical dominance. Thus, activation starts in the uppermost buds and progresses downward, and laterally around the canes and trunk until the enlarging discontinuous patches meet (Esau, 1948). The activated cambium recommences producing new xylem and phloem tissue (Plate 3.5). Unlike either the phloem or cambium, mature xylem vessels containing no living material are potentially functional whenever the temperature permits water to exist in a liquid state.

Phloem cells in the trunk may remain viable for upwards of 4 years, but most sieve tubes are functionally active only during the year in which they form (Aloni and Peterson, 1991). In the xylem, vessel inactivation begins about 2–3 years after formation, but is complete only after 6–7 years. Inactivation involves tyloses that grow into the vessel lumen from surrounding parenchyma cells. These paratracheal parenchyma cells also produce tyloses and gels that occlude vessels in response to wounding. Tyloses form primarily during the growing season whereas gels are deposited principally during the winter (Sun et al., 2008).

In woody sections, except for functional xylem and phloem, most of the tissues function in storing nutrients, notably starch. This even includes old xylem vessels plugged with tyloses. In the spring, most of the starch is remobilized and translocated to growing shoots.

In members of the subgenus Vitis, new cork cambia develop at infrequent intervals in nontranslocatory regions of the secondary phloem. Tissues external to the developing cork cambium, largely old phloem (and initially remnants of the cortex and epidermis), die and turn brown. The tissues subsequently split and are eventually shed. In contrast, in the subgenus Muscadinia, the cork cambium forms under the epidermis and persists for several years. Thus, canes of the Muscadinia do not form shedding bark like Vitis species (see Fig. 2.3D).

Tendrils

Tendrils are modified flower clusters, inhibited from completing floral development by gibberellins (Srinivasan and Mullins, 1981; Boss and Thomas, 2002). Tendril morphogenesis also depends on the balance between gibberellins and cytokinins (Srinivasan and Mullins, 1979). Flower clusters are, themselves, viewed as modified shoots. Not surprisingly, tendrils bear shoot-like features. However, unlike vegetative shoots, tendril growth is determinant, that is, growth is strictly limited. Tendril development also passes through three developmental and functional phases. Initially, tendrils develop water-secreting openings called hydathodes at their tips. Subsequently, the hydathodes degenerate and pressure-sensitive cells develop along the tendril. On contact with solid objects, these specialized cells activate elongation and cellular growth on the opposite side of the tendril. This induces twining of the tendril around the object touched. With differentiation of collenchyma in the cortex and xylem, and lignification of ray cells, the tendril becomes woody and rigid at maturity.

With the exception of Vitis labrusca and its cultivars, tendril production develops in a discontinuous manner in Vitis; that is, tendrils are produced opposite the first two of every three leaves, distal to the first two to three basal leaves. In V. labrusca, tendrils are produced opposite most leaves. On bearing shoots, flower clusters replace the tendrils in the lower two or more locations in most V. vinifera cultivars, and in the basal three to four tendril locations in V. labrusca cultivars.

Leaves

Leaves develop as localized outgrowths, just underneath the epidermis of the apical meristem. Cortical cells differentiate to connect the developing shoot vascular system with the vascular bundles in the developing leaf. These branches of the vascular system are termed leaf traces. They originate slightly below the leaf itself in the tightly compacted shoot tip (see Fig. 3.11). The first two leaf-like structures that develop in a bud develop into bracts. The internodes between the bracts are very short. Subsequent internodes elongate normally, and the leaf primordia that form at the nodes expand into mature leaves.

Maturing leaves consist of a broad, photosynthetically active blade, a supportive and conductive petiole, and two basal semicircular stipules. The latter soon die and dehisce, leaving only the petiole and blade. Unlike the growth of most plant structures, leaf expansion is not induced by apical or lateral meristems. Leaf growth entails the action of many, variously positioned, plate meristems (Fig. 3.13). The unique growth pattern generates the flat, distinctly lobed appearance that characterizes each cultivar.

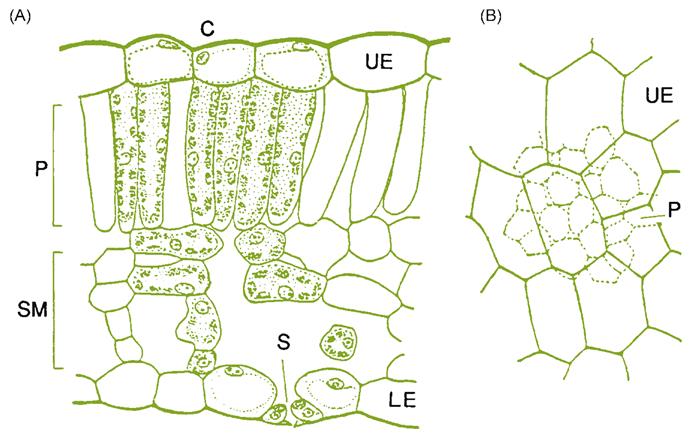

The leaf blade consists of an upper and lower epidermis, a single palisade layer, several layers of spongy mesophyll (Fig. 3.14), and a few large (and multiple small) veins. The epidermis consists of a single layer of flattened cells, with irregularly undulating edges, resembling the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Within these basic aspects, there can exist considerable variation in cell shape and size among cultivars (Boso et al., 2011). The upper epidermal wall is covered by a cuticle, consisting of a inner layer of cutin, and an outer waxy component. The latter consists of wax plates projecting upward from the surface. Cutin is composed of hydroxyl and hydroxyepoxy fatty acids, whereas the waxy plates are composed of a complex mix of long-chain aliphatic and cyclic compounds. The cuticle (notably its lipophilic, waxy outer layer) retards water and solute loss (Schönherr, 2006); helps limit the adherence of pathogens; minimizes mechanical abrasion of the leaf; and slows the diffusion of chemicals into the leaf. The lower epidermis shows a less well-developed cuticle and possesses stoma. Although stomatal shape, density, and distribution are varietal characteristics (Fig. 3.15), their number is influenced by environmental conditions. For example, stomatal density is reduced under warm soil conditions, increased CO2 concentration, and higher starch levels in the root and trunk (Rogiers et al., 2001). The undersides of leaves also typically possess leaf hairs and pearl glands. The latter derive their name from the small, bead-like secretions they produce. Water-secreting hydathodes commonly develop at the pointed tips (teeth) of the blade.

The palisade layer consists of cells directly below and elongated perpendicularly to the upper epidermis. When the leaf is young, the cells are tightly packed, but intercellular spaces develop as the leaf matures. In leaves that develop in bright sunlight, the palisade cells are shorter, but thicker than those formed in the shade. Cells of the palisade layer are the primary photosynthetic cells of the plant. Directly below the palisade layer are up to five to six layers of photosynthetic spongy mesophyll. The number of mesophyll layers is reduced when the leaf develops under sunny conditions. The cells of the mesophyll are extensively lobed, creating large intercellular spaces in the lower portions of the leaf. The large surface area thus generated, along with the stomata, facilitate the diffusion of water and gases between the inner leaf cells and the surrounding air. Without efficient evapotranspiration, the leaf would rapidly overheat in full sun, suppressing photosynthesis. Effective gas circulation is equally important for the rapid exchange of CO2 and O2. Carbon dioxide is an essential ingredient in photosynthesis, and oxygen (one of its by-products) inhibits the crucial carbon-fixing action of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBPCase).

The branching and anastomosis of the vascular system forms a net-like patchwork through the leaf. The network consist of a few large veins, containing several vascular bundles, and multiple, progressively smaller veins containing a single bundle. Each bundle consists of xylem toward the upper (adaxial) side and phloem toward the lower (abaxial) surface. At their extremities, they may consist of just a few tracheids. The vascular tissues of larger veins are surrounded by thickened cells, termed the bundle sheath. The latter may extend to the upper and lower epidermis.

Xylem translocates water and minerals such as calcium, manganese, and zinc, whereas the phloem transports organic compounds and minerals such as potassium, phosphorus, sulfur, magnesium, boron, iron, and copper. Organic compounds include sugars (primarily sucrose), amino acids (principally arginine), and growth regulators.

Because of the divisions created by the bundle sheath extensions, the leaf is subdivided into many relatively distinct compartments, with little lateral gas exchange. Under conditions of water deficit, low atmospheric humidity, or saline conditions, each compartment may show distinct differences (patchiness) in their respective rates of transpiration and photosynthesis (Düring and Loveys, 1996). Such leaves are termed heterobaric.

In the autumn, abscission layers form at the base of the leaf blade and petiole. Exchanges between the shoot and the leaf cease when a periderm forms between the stem and the petiolar abscission layer.

Photosynthesis and Other Light-Activated Processes

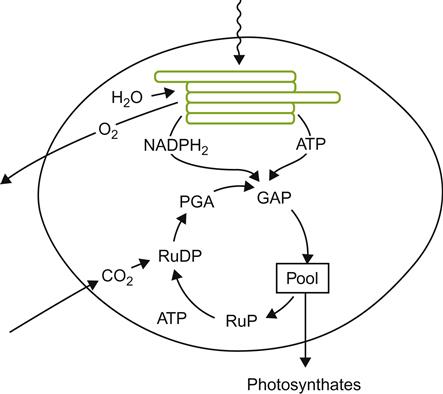

The production of organic compounds from carbon dioxide and water, energized by sunlight, is the quintessential attribute of plant life. While sugar is the major organic by-product of photosynthesis, it also provides the intermediates for fatty acid, amino acid, and nitrogen base synthesis. From these, the plant can derive all its organic needs. The process is summarized in Fig. 3.16.

Chlorophyll molecules, in a complex called photosystem II (PS II), absorbs light energy. This is used to split water molecules into their component elements. The liberated oxygen atoms combine to form molecular oxygen, escaping into intercellular spaces of the leaf and subsequently diffusing out into the surrounding air. In contrast, the liberated hydrogen ions dissolve in the lumen (central fluid) of the chloroplast thylakoid – membrane enveloped, disc-like structures found in chloroplasts (Fig. 3.16). Energized electrons, removed from the hydrogens, are passed along an electron-transport chain embedded within the thylakoid membrane. Associated with the shunting of electrons along the transport chain, hydrogen ions are pumped across the thylakoid membrane into the central fluid (stroma) of the chloroplast. Because the thylakoid membrane is highly impermeable to hydrogen ions, an electrochemical differential develops across the membrane. This drives the movement of hydrogen ions back, across the thylakoid membrane, via ATPase complexes embedded within the membrane. This transmembrane movement is associated with the phosphorylation of adenosine diphosphate (ADP), generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The partially de-energized electrons are passed along to chlorophylls in photosystem I (PS I), also embedded in the thylakoid membrane. These electrons are re-energized by photon energy absorbed by PS I. The electrons are subsequently passed to a second electron transport chain, finally being transferred to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+). The net result is the production of reducing power (NADPH) and high energy phosphate bonds (ATP). Both NADPH and ATP are required in what is termed the Calvin cycle for the synthesis of sugars during the ‘dark,’ CO2-fixing reactions of photosynthesis.

The initial by-product of CO2 fixation, with RuBP (ribulose bisposphate), is extremely unstable and splits almost instantaneously into two molecules of 3-phosphoglyceric acid (PGA). These enter the Calvin cycle. In the process, additional molecules of RuBP are regenerated. As increasing amounts of carbon dioxide are incorporated, and generate more PGA, enough carbon in incorporated to permit intermediates of the Calvin cycle to be diverted to the synthesis of sucrose and other organic compounds (Fig. 3.16). Quantitatively, sucrose is the most important immediate by-product of photosynthesis, as well as being the major organic compound translocated in the phloem out of the leaf. Sucrose may be stored temporarily, via conversion into starch, but is usually quickly transported out of the leaf to other parts of the plant. It may be subsequently stored in starch granules; polymerized into structural components of the cell wall; metabolized in the synthesis of other organic constituents; or respired as an energy source in cellular metabolism.

Because photosynthesis is fundamental to plant function, providing an optimal environment for its occurrence is one of the most essential aspects of viticulture, especially canopy management. A favorable light environment also influences other photo-activated processes. These include such vital aspects as inflorescence initiation, fruit ripening, and cane maturation.

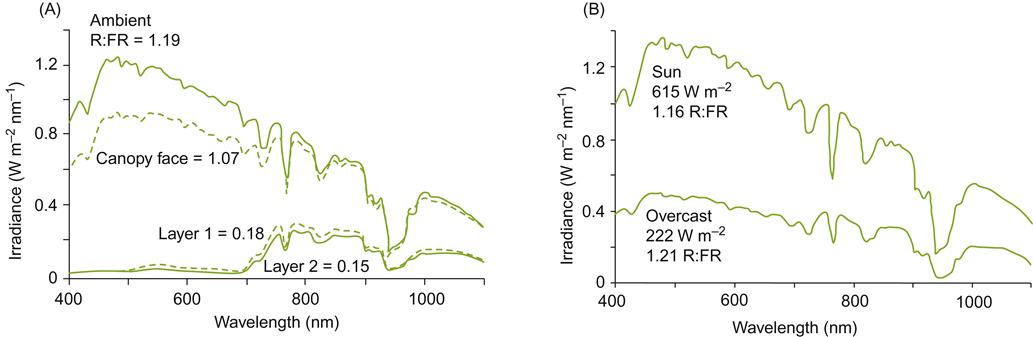

For photosynthesis, radiation in the blue and red regions of the visible spectrum is particularly important. For most other light-activated processes, it is the balance between the red and far-red portions of the electromagnetic spectrum that is crucial, as well as the ultraviolet sections. The differences relate to both energy requirements and the pigments involved.

In photosynthesis, the important pigments are chlorophylls and carotenoids, whereas in most other light-activated processes, phytochrome is involved. Both chlorophylls a and b absorb optimally in the red and blue portions of the electromagnetic spectrum, whereas carotenoids absorb significantly only in the blue. The splitting of water, the major light-activated process in photosynthesis, is energy-intensive. Nonetheless, for an assortment of reasons, the overall rate of vine photosynthesis is maximally effective at about one-third of full sunlight intensity (700–800 μmol/m2/s). This relates to rate-limiting factors imposed by the pace of the dark (carbon-dioxide) reactions of photosynthesis. In the center of a dense vine canopy, photosynthesis is minimal – due to the low light intensity (15–30 μmol/m2/s). This is due to the absorption (or reflection) of most of the photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) by the outer leaf layers.

In contrast, phytochrome-activated processes require little energy. For these, shifts between the two states of phytochrome depend on the relative intensities in the red and far-red portions of the spectrum. These regions correspond to the absorption peaks of the two alternate states of phytochrome, Pr and Pfr : 650–670 nm and 705–740 nm, respectively. Red light converts Pr to the physiologically active Pfr state, whereas far-red radiation transforms it back into physiologically inactive Pr. In sunlight, the natural red/far-red balance (1.1–1.2) generates a 60 : 40 ratio between Pfr and Pr. However, when light passes through the leaf canopy, the strong red absorbency of chlorophyll shifts the red/far-red balance to about 0.1 (toward the far-red). This probably means that some processes active in sunlit tissue are inactive in shaded tissue. The precise levels and actions of phytochrome in grapevine tissues are poorly understood.

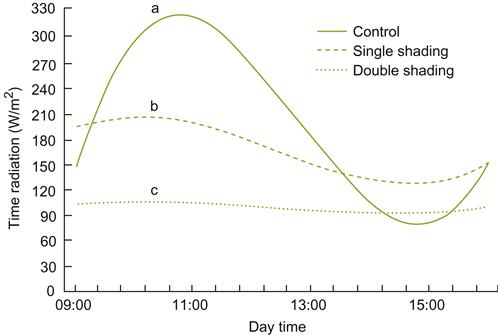

Because of the negative influence of shade on photosynthesis and modification to phytochrome-induced phenomena, most pruning and training systems are designed to optimize light exposure. The effects of shading on spectral intensity and the red/far-red balance are illustrated in Fig. 3.17A. In contrast, cloud cover produces little spectral modification in the visible and far-red spectra, although it markedly reduces their intensity (Fig. 3.17B). Cloud cover does, however, significantly reduce the infrared (heat) portion of solar radiation received from the sun. Figure 3.18 illustrates the daily cyclical effects of shade on light conditions at different canopy levels. Because photosynthesis is usually maximal at light intensities equivalent to that provided by a slightly overcast sky, cloud cover has its most marked effect on the photosynthesis of shaded leaves.

Canopy shading affects both leaf structure and physiology. In response to shading, pigment content increases (carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b) and the compensation point (the light intensity at which the rates of photosynthesis and respiration are equal) decreases to about 10–30 μmol/m2/s. Nevertheless, the lower respiratory rate of cooler shaded leaves, enhanced pigmentation, and reduced compensation point do not fully redress the poorer spectral quality and diminished intensity of shade light. As a result, shade leaves generally do not photosynthesize sufficiently to export sucrose or contribute significantly to vine growth. This was dramatically shown by Williams et al. (1987), where removal of shade leaves (30% of the foliage) did not delay berry growth or maturity. This situation might change in windy environments. Movement of the exterior canopy could markedly increase sunflecking (periodic exposure to sunlight through the canopy). Although sunflecking is highly variable, average rates of 0.6 s per 2 s intervals could significantly improve shade-leaf net photosynthesis (Kriedemann et al., 1973). Sunflecking also appears to delay premature leaf senescence and dehiscence.

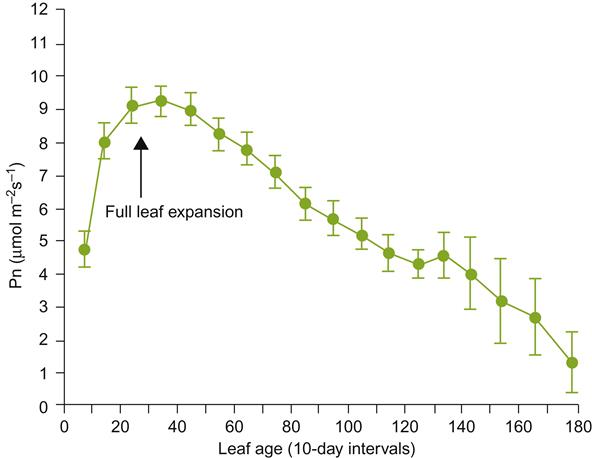

When leaves are young and rapidly unfolding, they act as carbohydrate sinks, rather than a net source of photosynthate. Leaves begin to export photosynthates (sugars and other organic by-products) when they reach about 30% of their full size. At this stage they develop their mature green coloration. Nonetheless, leaves continue to import carbohydrates until they have reached 50–75% of their mature size (Koblet, 1969). Maximal photosynthesis and sugar export occur about 40 days after unfolding, when the leaves have fully expanded (Fig. 3.19). Old leaves continue to photosynthesize, but their contribution to vine growth declines significantly (Poni et al., 1994). The rate of this photosynthetic decline varies considerably, depending on the light environment, nitrogen availability, and the development of new leaves. Leaves cease to be net producers when they lose their typical dark-green coloration. Leaves formed early in the season may photosynthesize at up to twice the rate of those produced later.

The angle of the sun, relative to the leaf blade, also influences photosynthetic rate. Nevertheless, even leaf blades aligned parallel to the sun’s rays may photosynthesize at rates up to 50% that of perpendicularly positioned leaves (Kriedemann et al., 1973). This probably reflects the importance of diffuse sky light, the benefits of a cooler leaf temperature, and maximal photosynthetic rates occurring at well below full sunlight intensity.

The effect of temperature on photosynthesis varies slightly throughout the growing season. In the summer, optimal fixation tends to occur at between 25 and 30 °C, whereas in the autumn the optimum may decline to between 20 and 25 °C (Stoev and Slavtcheva, 1982). Photosynthesis is more sensitive to (suppressed by) temperatures below 15 °C than to temperatures above the optimum (>40 °C).

Fruit load and canopy size affect photosynthesis, presumably through feedback regulation. Within limits, the rate of photosynthesis can adjust itself to demand. For example, fruit removal results in a reduction in the photosynthetic rate of adjacent leaves (Downton et al., 1987). Conversely, photosynthetic rate increases as a consequence of basal leaf removal. Improved photosynthetic efficiency appears to be associated with wider stomatal openings and increased gas exchange. Greater sugar demand could also activate export, thus reducing the concentration of Calvin-cycle intermediates that could act as photosynthetic feedback inhibitors.

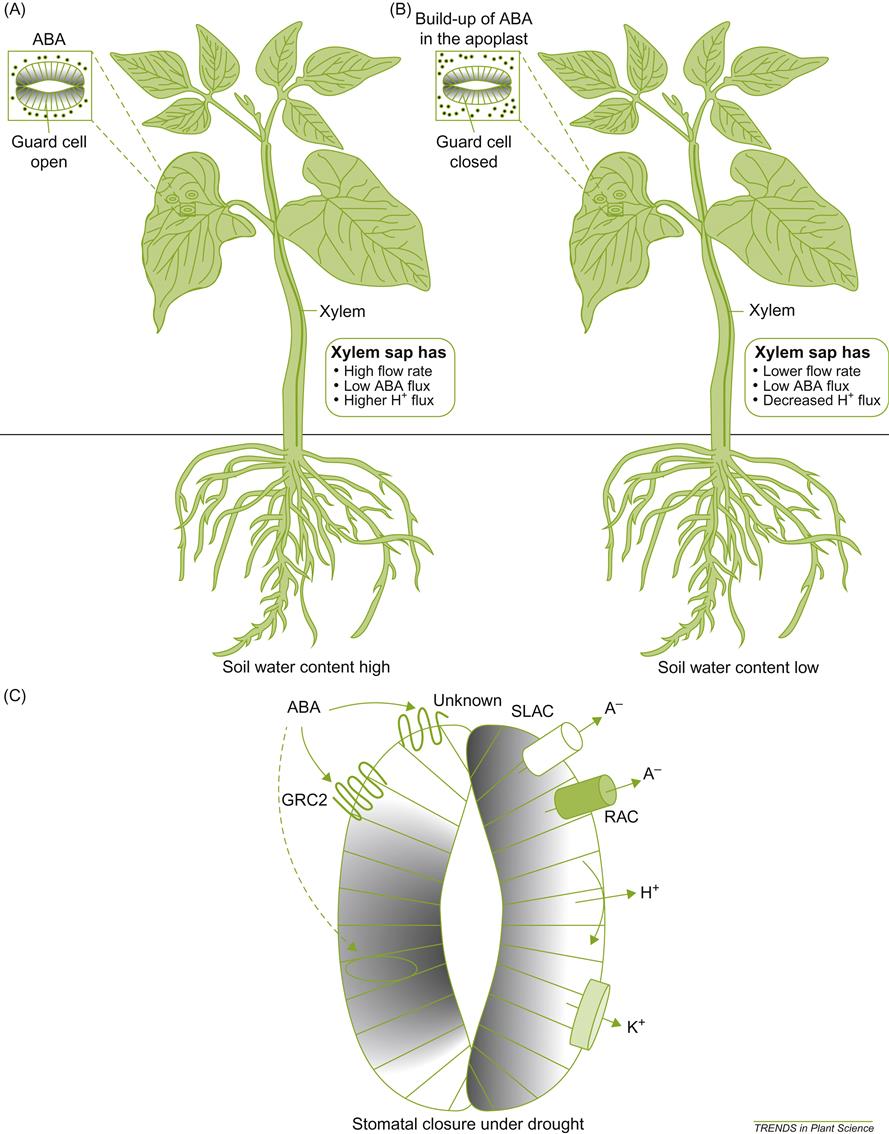

Water conditions also markedly influence the rate of photosynthesis. In particular, water deficit increases the production of abscisic acid. This, in turn, enhances the synthesis of other activator molecules, notably hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide (Patakas et al., 2010). These changes induce stomatal closure; reduce transpiration rate and gas exchange; increase leaf temperature; and suppress photosynthesis. Because water status affects the relative incorporation of stable carbon isotopes (13C/12C ratio) (Brugnoli and Farquhar, 2000), this feature has been used to assess the cumulative effects of water status on vine photosynthesis (Gaudillère et al., 2002). Plate 3.6 illustrates a technique for assessing whole-plant gas exchange.

The direction of carbohydrate export from leaves varies with their position along the shoot, and the time of year. Export from young maturing leaves generally is apical, toward new growth. Subsequently, photosynthate from the upper maturing leaves is directed basally, toward the fruit (see Fig. 3.41). By the end of berry ripening, basal leaves are rarely involved in export. This function is taken over by the upper leaves. Translocation typically is restricted to the side of the cane and trunk on which the leaves are produced.

Phytochrome is associated with a wide range of photoperiodic and photomorphogenic responses in plants. Typically, grapevines are relatively insensitive to photoperiod, but may show several other phytochrome-induced phenomena. For example, bud dormancy in Vitis labrusca and V. riparia is induced by short-day photoperiods (Fennell and Hoover, 1991; Wake and Fennell, 2000). Several plant enzymes are partially activated by changes in phytochrome balance. These include those involved in the synthesis and metabolism of malic acid (malic enzyme); the production of phenols and anthocyanins (phenylalanine ammonia lyase and dihydroflavonol reductase) (Gollop et al., 2002); sucrose hydrolysis (invertase); and possibly nitrate reduction and phosphate accumulation (see Kliewer and Smart, 1989). Phytochrome is also suspected of being implicated in the regulation of berry growth (Smart et al., 1988). Nevertheless, the actual importance of the shift in the Pfr/Pr ratio in shaded grapevine leaves is unclear. Also, the significance of sunflecking on phytochrome balance is unknown.

A third, light-induced process in grapevines is activated by ultraviolet (UV) radiation, namely the toughening of the cuticle. Strong ultraviolet absorption by phenolics in the leaf results in its almost complete absence in shade light. Consequently, UV-induced hardening of the cuticle in shaded leaves and fruit is absent, resulting in their surfaces being softer than their sun-exposed counterparts. This factor, combined with the slower rate of drying and higher humidity in the understory, may explain the greater sensitivity of shaded tissue to fungal infection. Protection against UV-induced mutation is presumably one of the rationales for young leaves and other tissues possessing anthocyanins. It is suspected, but unconfirmed, that either or both of the blue/UV-A (315–380 nm) or UV-B (280–315 nm) photoreceptors (such as cryptochrome) are involved.

Exposure to short-wave ultraviolet radiation (UV-C, 100–280 nm) also appears to activate several metabolic pathways. This is of particular importance in general disease resistance, as the activated pathways include those involved in the synthesis of phytoalexins, chitinases, and pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins (Bonomelli et al., 2004). In addition, exposure to UV-B increases pre-véraison (a phase in grape maturation prior to a noticeable loss in green fruit coloration) flavonol content in the skin of Sauvignon blanc, but does not appear to influence the amino acid or methoxypyrazine content (Gregan et al., 2012).

Transpiration and Stomatal Function

To optimize its photosynthetic potential, the leaf must act as an efficient light trap. Because of the importance of diffuse radiation coming from the sky, most leaves provide a broad surface for light impact. Even on clear days, up to 30% of the radiation impacting a leaf may come from diffuse sky light. However, the large surface area of the leaf blade makes it also an effective heat trap. Heating is reduced by evaporative cooling, but, if unrestricted, would place an unacceptably high water demand on the root system. The cuticular coating of the leaf limits water loss, but also retards gas exchange essential for photosynthesis. These conflicting demands result in a series of complex and dynamic compromises.

When the water supply is adequate, transpirational cooling can effectively minimize leaf heating during direct sun exposure to about 1–2 °C above ambient (Millar, 1972). This, however, places considerable demands on the root system. Even under mild transpiration conditions, water loss can occur at rates of up to 10 mg/cm2/h. Except for the small proportion of water (<1%) used in photosynthesis, and in other metabolic reactions, most of the water absorbed by the root system is lost via transpiration. However, water loss usually does not begin to significantly limit transpiration, or photosynthesis, until leaf water potentials (ψ) fall below−13 to−15 bar.