Cell division in the flesh occurs most rapidly about 1 week after fertilization. It subsequently slows, and may stop within 3 weeks. Cell division begins to cease close to the seeds, and lastly next to the skin. Cell enlargement may occur at any stage of berry development, but is most marked after cell division ceases.

The epidermis consists of a single layer of flattened, disk-shaped cells, with irregularly undulating edges. These nonphotosynthetic cells possess vacuoles containing large oil droplets. Depending on the variety, the epidermis may develop thickened or lignified walls. The epidermis does not differentiate hair cells and produces few stomata (~1–2 per mm, i.e., less than 1% that of leaves). The stoma that do form are sunken, within raised (peristomal) regions (Fig. 3.30). They soon become nonfunctional. Subsequently, transpiration occurs primarily through the cuticle. Heat dissipation results primarily from wind-facilitated convection away from the berry surface.

The surface of the peristomal region accumulates abnormally high concentrations of silicon and calcium (Blanke et al., 1999). As the fruit matures, this region also becomes considerably suberized and accumulates polyphenolics. Microfissures may develop next to the stoma during periods of rapid fruit enlargement (see Fig. 4.42A). Diurnal berry diameter can fluctuate up to 6% during the pre-véraison period. This results from transpirational water loss during the day and reuptake at night (Greenspan et al., 1996).

As with other aerial plant surfaces, a relatively thick layer of cuticle and epicuticular wax develops over the epidermis (Fig. 3.31A). The cuticle is present almost in its entirety before anthesis. It forms as a series of compressed ridges a few weeks prior to anthesis (Fig. 3.31B). During subsequent growth, the ridges spread apart and eventually form a relatively flat layer over the epidermis (Fig. 3.31C). Exposure to intense sunlight and high temperatures appears to destroy its crystalline structure, and is correlated with fruit susceptibility to sunburn (Greer et al., 2006). Initially, the wax platelets are small and upright, occurring both between and on cuticular ridges. The number, size, and structural complexity of the platelets increase during berry growth (Fig. 3.31D). These changes in platelet structure may correspond to modifications in the chemical nature of these wax deposits. The cuticular covering is not necessarily uniform, as evidenced by the occurrence of microfissures in the epidermis (see Fig. 4.56A) and micropores in the cuticle (see Fig. 4.56B). These features, along with the presence of stomata, lenticels, stylar scars, the receptacle, and vascular connection to the pedicel limit the effectiveness of the cuticle in restricting water loss. Nonetheless, it does limit water loss sufficiently to result in much more marked berry temperature fluctuation during the day, when exposed to the sun, than is experienced by leaves (Millar, 1972; see Fig. 5.36).

The occurrences of such features, as well as cuticular thickness and wax plate structure, are affected by both hereditary and environmental factors. Thus, their influence on disease resistance is complex and may vary from season to season.

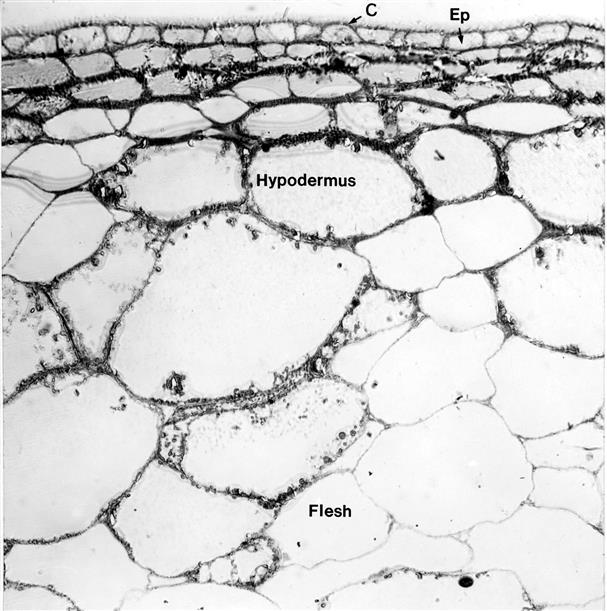

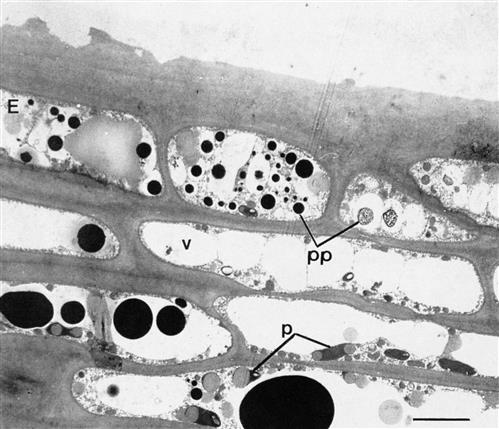

The hypodermis consists of a variable number of tightly packed mesophyll layers (see Fig. 3.29). The cells are flattened, with especially thickened corner walls. The hypodermis commonly contains about 10 layers, but this can vary from 1 to 17, depending on the cultivar and growth conditions. When young, hypodermal cells are photosynthetic. After véraison, the plastids lose their chlorophyll and starch contents, and begin to accumulate oil droplets (Fig. 3.32). They appear to be the principal site of terpenoid and norisoprenoid synthesis and storage. These compounds are thought to be the by-products of carotenoid degradation. Most hypodermal cell vacuoles accumulate flavonoid phenolics (Fig. 3.32), notably anthocyanins in the outermost layers of red grape varieties. In addition, hypodermal cells may contain vacuolar collections of raphides (needle-like crystals of calcium oxalate monohydrate) (DeBolt et al., 2004). These become less abundant during maturation. Calcium oxalate also occurs as star-shaped crystalline formations in cells of the flesh, called druses.

During ripening, the cell wall thickens, due to hydration, and connections between the cells loosen. In ‘slip-skin’ varieties, the cells of the flesh adjacent to the hypodermis become thinner and lose much of their pectinaceous cell-wall material. This produces a zone of weakness, permitting the skin to separate readily from the flesh.

Cell division in the flesh begins several days before anthesis, and continues for about another 3 weeks. Subsequent growth is largely due to cell enlargement. Correspondingly, fruit size is predominantly associated with cell enlargement, the number of pericarp cells being little influenced by the external environment. The most rapid period of pericarp enlargement occurs shortly after anthesis. Although associated with rapid cell division, this period also correlates with the most rapid water uptake. This may explain the high sensitivity of fruit set to water stress during this period (Nagarajah, 1989).

Most of the cells in the flesh are round to ovoid, with growth after véraison being exclusively due to cell enlargement. The result being that the pericarp tends to constitute about 65% of the berry volume. The central cell vacuole expands considerably during véraison, becoming the primary site for sugar accumulation. In addition, there is a diversity of smaller vacuoles, differing not only in size, but also in contents (Fontes et al., 2011). They are the principal sequestering sites for phenolics, organic acids, terpenoids, and ions such as potassium and calcium. Cells in the outer mesocarp generally contain plastids, but they seldom contribute significantly to photosynthesis. Although the cells of the pericarp remain viable late into maturity, their plasmodesmal connections appear to disintegrate.

The vascular tissue of the fruit develops directly from that of the ovary. It consists primarily of a series of peripheral bundles that ramify throughout the outer circumference of the berry, and axial bundles extending directly up through the septum. The locules of the fruit correspond to the ovule-containing cavities of the ovary and are almost undetectable in mature fruit. The locular space is filled either by the seeds or by growth of the septum.

Fruit abscission may occur either at the base of the pedicel, or where the fruit joins the receptacle. Separation at the pedicel base (shatter) results from the localized formation of thin-walled parenchymatous cells. This commonly occurs if the ovules are unfertilized, or there is early seed abortion. Some varieties, such as Muscat Ottonel, Grenache, and Gewürztraminer are abnormally susceptible to fruit abscission shortly after fertilization – a physiological disorder called inflorescence necrosis (coulure). In contrast, dehiscence that follows fruit ripening in muscadine cultivars results from an abscission layer that forms in the vascular tissue at the apex of the pedicel, next to the receptacle.

Seed Morphology

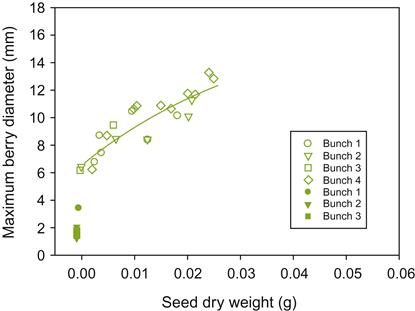

As noted, seed development is associated with the synthesis of growth regulators vital to fruit growth. Therefore, fruit size is largely influenced by seed number and weight (Fig. 3.33).

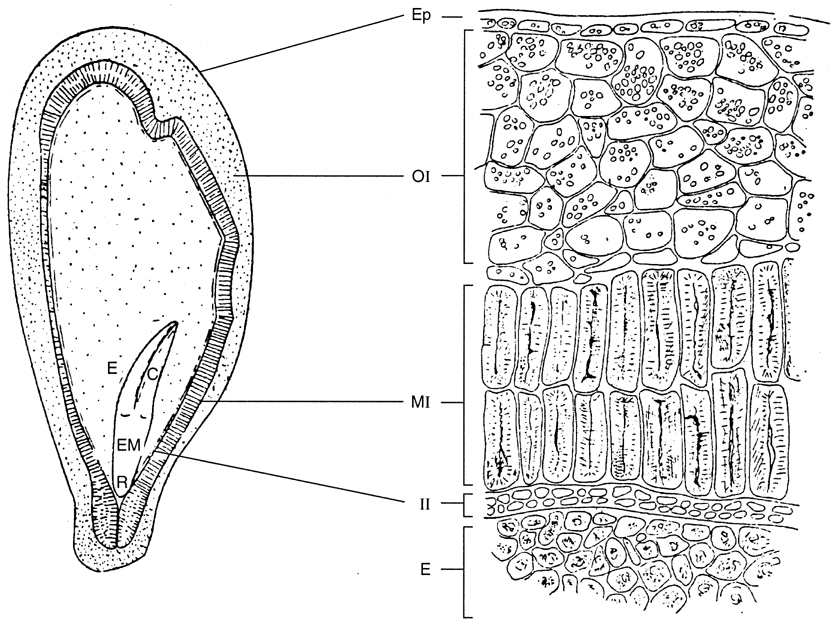

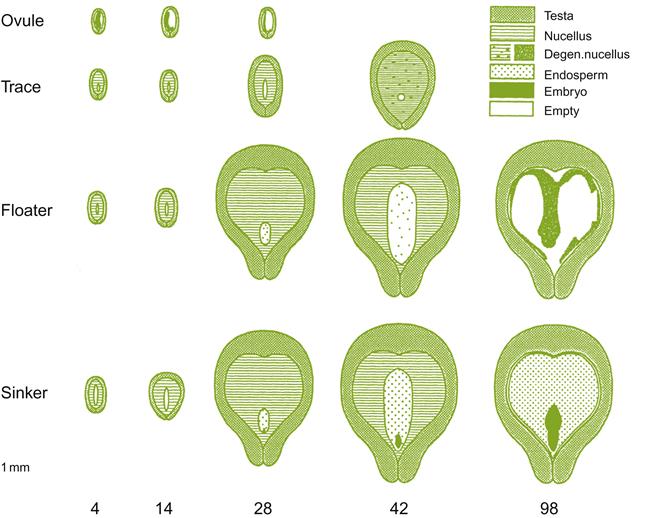

Seeds typically constitute only a small portion of the berry fresh weight. Similarly, the embryo makes up only a modest proportion of the seed volume (Fig. 3.34). The embryo consists of two seedling leaves (cotyledons), a nascent shoot (epicotyl), and an embryonic root (radicle) at the tip of the hypocotyl. The embryo is surrounded by a nutritive endosperm, which constitutes the bulk of the seed. The endosperm is itself enclosed in a pair of seed coats (integuments), of which only the outer integument (testa) develops significantly. The testa consists of a hard, lignified inner section, a middle parenchymatous layer, and an outer papery component or epidermis. Most of the seed tannins are located in the outer, thin-walled cells. Browning commences after véraison. The surface is covered by a cuticle.

Four seeds may develop, but usually less than that mature. Only 20% of ovules may be fertilized (Ebadi et al., 1996). Berry development may be initiated by pollination, but continued growth is dependent on seed development. At least one mature seed is required for full berry development, but size is often related to seed number. When seed development terminates early, what remains is termed a trace. When all the seeds abort early, the berries remain relatively small, being termed shot. In addition, of those seeds that do develop, some may not fully mature, lacking an endosperm and possessing an atypical embryo. These are classed as floaters. Fully mature seeds are called sinkers (Fig. 3.35).

Chemical Changes during Berry Maturation

Due to the importance of both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of berry development, the subject has received extensive study. Most of the research has been pragmatically driven, directed at improving grape yield and quality rather than generating a unified theory of grape berry development. Such a theory might arise out of current investigations into the dynamics of gene transcription and metabolite production during ripening (Deluc et al., 2007), combined with modeling schemes (Dry et al., 2010). The following discussion will incorporate, where possible, physiological explanations of berry development. Because of the chemical nature of certain topics, some readers may wish to refer to Chapter 6 for clarification.

Understanding the dynamic chemical changes during berry development is often made harder by the various ways in which data have been presented (fresh weight, dry weight, per berry, per cluster). The potential for translocation, chemical modification, and polymerization further complicates interpretation. Finally, the enologic significance of these changes is often unclear, being dependent on extraction dynamics during vinification, a factor not necessarily, nor directly, correlated with fruit composition. This is especially true when dealing with phenolic and flavor compounds.

Recently, an array of new techniques have been added to traditional microscopic and biochemical investigations. For example, genetic mutants are being extensively used to study the biochemical aspects of ripening. Their use has advanced our understanding of berry color development considerably. Genomic approaches are also being applied to the complex pleiotropic and epistatic controls of berry flavor development. Three-dimensional scanning techniques, now standard in medical practice, are being adapted to investigate, in situ, water flow in the xylem and phloem (magnetic resonance imaging), the movement of 11C-labeled photosynthates (positron emission tomography), and detailed cellular and morphological analysis (high-resolution X-ray computed tomography) (Dhondt et al., 2010). With such tools, age-old questions, hitherto studied only indirectly, may begin to shed their secrets.

Growth Regulators

A major shift in metabolism occurs simultaneously with berry color change (véraison). That these changes are controlled by plant-growth regulators is beyond doubt. Regrettably, the specific actions and interactions of these growth regulators remain unclear. Unlike animal hormones, plant growth regulators have many and differing actions. In addition, with the exception of abscisic acid and ethylene, auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins and brassinosteroids occur in multiple forms, each with seemingly slightly different roles. Most may also occur in free and bound (inactive) states. It is also technically difficult to follow concentration changes in situ, where amounts may vary in different parts of the fruit or cell. Individual hormonal effects can also vary with the tissue involved, its physiological state, and the relative and absolute concentration of other growth regulators. This situation only further complicates the problem of differentiating between direct and indirect effects. The site specificity of growth hormone action and hormone interaction has made understanding, let alone prediction, of growth-regulator effects excruciatingly difficult (Teszlák et al., 2005; Considine and Cass, 2009).

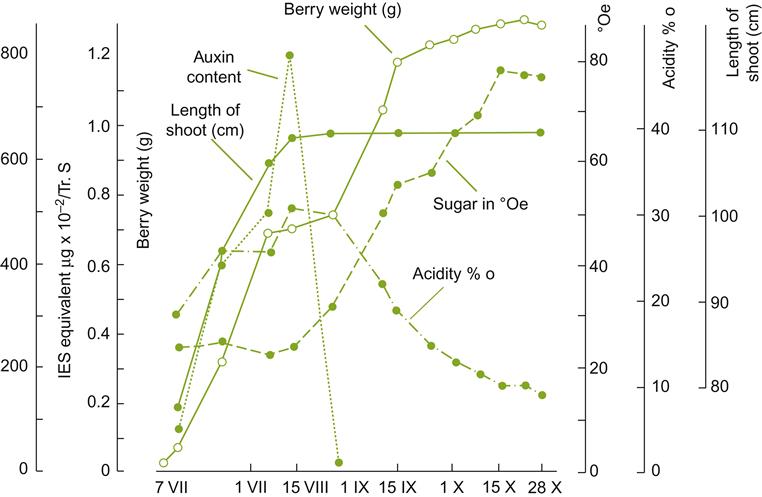

During stage I berry growth, auxin, cytokinin, and gibberellin contents tend to increase. They undoubtedly stimulate cell division and enlargement up to véraison. Their subsequent role in cell enlargement is unclear, because their concentrations are in decline. The drop in auxin and gibberellin contents coincides with an increase in the concentration of free abscisic acid, which is highest about véraison but falls thereafter (Fig. 3.36). In other studies, abscisic acid has shown two peaks, shortly before and after véraison (Owen et al., 2009). The decline in auxin content also correlates with a reduction in fruit acidity, the accumulation of sugars, and a decrease in shoot growth (Fig. 3.37). The importance of the decline in auxin content is suggested by the delay in ripening provoked by the application of auxins (Davies et al., 1997). Gibberellins appear most significant to seed growth, rising until the onset of véraison then declining (Pérez et al., 2000).

), A520 mn (

), A520 mn ( ), and free abscisic acid concentration (■) during the development of Cabernet Sauvignon berries. Standard errors are indicated. (From Wheeler et al., 2009, reproduced by permission.)

), and free abscisic acid concentration (■) during the development of Cabernet Sauvignon berries. Standard errors are indicated. (From Wheeler et al., 2009, reproduced by permission.)

Ethylene has traditionally been considered to play an insignificant role in grape ripening. However, data from El-Kereamy et al. (2003) suggest it may play a role in initiating anthocyanin synthesis. Its application activates the production of enzymes involved in flavonoid and anthocyanin synthesis. In addition, inhibition of its action by the application of 1-methylcyclopropene, a specific inhibitor of ethylene receptors, reduces sugar accumulation post-véraison (Chervin et al., 2006). Ethylene experiences a transient doubling, just prior to véraison (Chervin et al., 2004). Hilt and Blessis (2003) have also demonstrated ethylene’s action in young fruit abscission, presumably via its promotion of abscisic acid synthesis.

Because of their influence on berry development, growth regulators have been occasionally applied to control fruit growth and spacing within clusters (Plate 3.10). Generally, synthetic growth regulators have been more effective than their natural counterparts. They have the advantage of being less affected, or even unaffected, by natural feedback inhibition pathways in the vine. Artificial auxins, such as benzothiazole-2-oxyacetic acid, can delay ripening up to several weeks when applied to immature fruit. Conversely, the artificial growth retardant, methyl-2-(ureidooxy) propionate, markedly hastens ripening when applied before véraison (Hawker et al., 1981). Ripening can also be shortened marginally by applying growth regulators, such as ethylene or abscisic acid. The discovery that presumptive sites on the UFGT gene promoter are responsive to abscisic acid, ethylene, light, and sugar (Chervin et al., 2009) is consistent with their role in grape coloration, i.e., augmenting UFGT production (Peppi et al., 2008). UFGT is an essential enzyme in anthocyanin synthesis (see Fig. 3.44).

Although correlations have been found between changes in growth regulators and physiological and biochemical changes associated with ripening, direct causal relations are limited. Thus, many of these associations may be due to the combined actions of two or more regulators, or they may be indirect. Precise knowledge of the sequence of steps involved could potentially generate better regulation of berry development and fruit quality. An example of our lack in fundamental knowledge has been the recent discovery of a new group of growth regulators, the brassinosteroids, and their unsuspected role in berry ripening (Symons et al., 2006).

Water Uptake

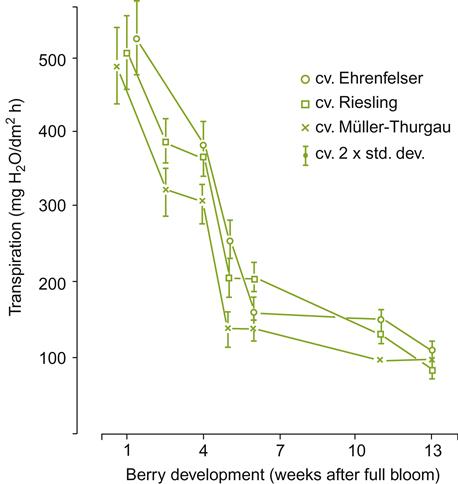

During development, structural changes in the skin and vascular tissues influence the types and amount of substances transported to the fruit. The degeneration of stomatal function, disruption of xylem function, and development of a thicker waxy coating can combine to reduce transpirational water loss (Fig. 3.38). This also reduces gas exchange between the berry and its surroundings, as well as increasing the likelihood of fruit overheating and day–night temperature fluctuations.

As berries near maturity, water uptake declines (Rogiers et al., 2001). This can produce a 10-fold reduction in hydraulic conductance from véraison to ripeness (Tyerman et al., 2004). This has normally been interpreted as resulting from xylem vessels rupturing in the peripheral vascular tissues of the berry (Creasy et al., 1993). However, this view has been challenged (Chatelet et al., 2005). Although vessels may stretch during post-véraison berry enlargement (being annular or spiral thickened), with some rupturing, others remain functionally intact. In addition, new vessels may develop post-véraison (Chatelet et al., 2008). Thus, it appears that berry swelling, as can occur during rainy spells near harvest, may occur due to water uptake via the receptacle region (Becker and Knoche, 2011), and not via microcracks in the skin.

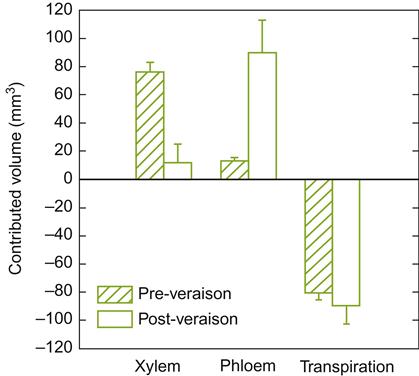

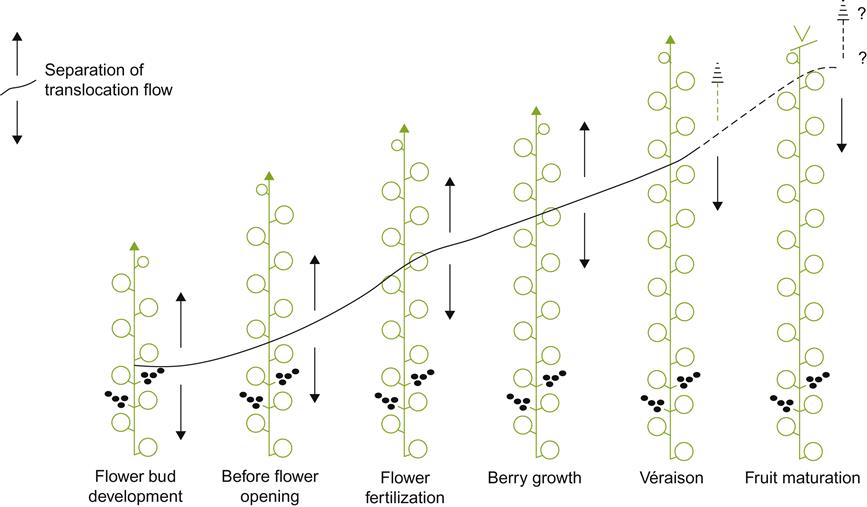

Data from Bondada et al. (2005) suggest that the decrease in xylem flow results from a reduction in the hydrostatic gradient leading to reduced flow. This could explain why most water uptake in post-véraison berries is associated with photosynthate transport via the phloem (Fig. 3.39), and why diurnal fluctuations in berry diameter disappear post-véraison (Greenspan et al., 1994). It would also explain why minerals such as calcium, manganese, and zinc, transported primarily in the xylem, become restricted post-véraison (Rogiers et al., 2006b). In contrast, potassium, which is transported equally in the phloem and xylem, continues to accumulate throughout ripening (Hrazdina et al., 1984). The increasing importance of phloem transport for water, as well as organic and inorganic nutrients during ripening, has been equally found in other fruits, for example apples and tomatoes. Evidence is contradictory as to whether the xylem acts as a conduit for the movement of water out of the berry (Lang and Thorpe, 1989; Greenspan et al., 1996).

At maturity, the phloem ceases to function due to the formation of a periderm at the base of the berry. Its formation also cuts off xylem connection, facilitating detachment of the fruit from the pedicel. Termination of vascular connections with the fruit probably explains shrinkage of the fruit at this stage (Rogiers et al., 2006a). Cultivars such as Shiraz, are particularly sensitive to such shriveling.

Sugars

Quantitatively, sucrose is the most significant organic compound translocated into the fruit. Initially, though, carbohydrate is photosynthesized in situ. As the berry enlarges and approaches véraison, the surrounding leaves become the major carbohydrate supplier. The trunk and arms of the vine may also provide additional carbohydrate. It has been estimated that under abnormal conditions, up to 40% of the carbohydrate accumulated by fruit may be supplied by the permanent, woody parts of the vine (Kliewer and Antcliff, 1970).

Sugar accumulation is particularly marked following véraison. This coincides with a pronounced decline in berry glycolysis, and a reduction of cell turgor (Matthews et al., 2009). Primary shoot growth also tends to slow dramatically at this time, facilitating a major redirection of photosynthate toward the fruit. Root growth also declines following véraison, further reducing its drain on photosynthate. An alternate interpretation, though, is that decreased shoot and root growth result because of the carbohydrate drain associated with berry sugar accumulation. An adequate, coordinated, explanation of these events has still to be provided.

Part of the carbohydrate accumulation in berries may also relate to reduced sugar metabolism, associated with a shift from glucose to malic acid respiration. Malic acid accumulates in considerable amounts early in fruit development, being respired post-véraison via the TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle (see Fig. 7.20). Although potentially involved, it is unlikely to be a major factor. Grapes in cool regions accumulate sugars to about the same degree as warmer regions, despite their retaining much of their malate content during ripening.

Another minor factor contributing to the increase in sugar content may be the biosynthesis of glucose from malic acid. Gluconeogenesis may explain the reduction in other TCA intermediates, such as citric and oxaloacetic acids during maturation. The increase in abscisic acid content, associated with the beginning of véraison, may activate this metabolic shift (Palejwala et al., 1985). Nevertheless, the major factor involved in the marked accumulation of sugar undoubtedly relates to a redirection of phloem sap from leaves to the fruit (Dreier et al., 2000).

The most significant factor promoting the redirected flow of sugar into the berry appears to be evapotranspiration (Rebucci et al., 1997; Dreier et al., 2000). Because water flow via the xylem slows and essentially stops after véraison, water uptake by the fruit continues via the phloem. Sucrose and other constituents, such as amino acids, are presumably imported in the water flow. Conversion of sucrose into glucose and fructose in the berry doubles its osmotic potential, augmenting further sap flow toward the fruit. Chemical modifications of wall constituents facilitate cell enlargement, permitting enhanced water transport and sugar accumulation. Because smaller berries have relatively more surface area, and thereby are exposed to higher evapotranspiration rates, this may explain why smaller berries tend to have higher sugar contents than larger fruit.

On reaching the berry, most of the sucrose is hydrolyzed by invertase. Although it liberates equal amounts of glucose and fructose, their relative concentrations are seldom identical. In young berries, the proportion of glucose is generally higher. During ripening, the glucose/fructose ratio falls, with fructose retention being slightly higher than glucose. Thus, by maturation, if not before, fructose is marginally more prevalent than glucose (Kliewer, 1967). The reasons for this disequilibrium are unknown, but may originate from differential rates of glucose and fructose metabolism in the berry, or selective synthesis of fructose from malic acid.

As with other cellular constituents, sugar accumulation varies with the cultivar, maturity, and prevailing environmental conditions. Depending on these factors, the sugar content may vary from 12–28% at harvest. Further increases during overripening appear to reflect concentration, due to water loss, rather than additional sugar uptake. For winemaking, optimal sugar contents usually range between 21 and 25%.

Depending on the species or cultivar, some of the sucrose translocated to the fruit is retained as sucrose. This is most marked in muscadine cultivars, in which 10–20% of the sugar content may remain as sucrose. In some French-American hybrids, sucrose constitutes about 2% of the sugar content. In most V. vinifera cultivars, the sucrose content averages about 0.4% (Holbach et al., 1998).

Small amounts of other sugars are found in mature berries, notably raffinose, stachyose, melibiose, maltose, galactose, arabinose, and xylose. Their presence is disregarded in assessing sugar content because they occur in such small amounts, are not metabolized by wine yeasts, and do not impact perceived sweetness.

Sugar storage occurs primarily in the central vacuole of mesophyll cells, with lesser amounts being deposited in the skin (Fig. 3.40). This can vary with the cultivar and stage of ripening. In contrast, the small amount of sucrose that occurs in V. vinifera fruit is restricted to the axial vascular bundles, and the skin adjacent to the peripheral vascular strands.

During ripening, much of the sugar comes from leaves located on the same side of the shoot as the fruit cluster and directly above the cluster. Carbohydrate supplies increasingly come from the shoot tip, as it develops (Fig. 3.41), with additional amounts from associated lateral shoots and old wood. Estimates of the foliage cover (leaf area/fruit weight) required to fully ripen grape clusters vary considerably, from 6.2 cm2/g (Smart, 1982) to 10 cm2/g (Jackson, 1986). The latter appears to be more typical. The variation may reflect varietal and environmental influences on fruit load and leaf photosynthetic efficiency.

Acids

Next to sugar accumulation, reduction in acidity is quantitatively the most marked chemical change during ripening. Tartaric and malic acids account for about 70–90% of the berry acid content. The remainder consists of variable amounts of additional organic acids (e.g., citric and succinic acids), phenolic acids (e.g., quinic and shikimic acids), amino acids, and fatty acids.

Although structurally similar, tartaric and malic acids are synthesized and metabolized differently. Tartaric acid is derived via a complex transformation from vitamin C (ascorbic acid). This appears to involve L-idonic acid as a rate-limiting step (DeBolt et al., 2006). The importance of tartaric acid in grape development and metabolism, if any, is unknown. In contrast, malic acid is an important TCA intermediate. As such, it can be variously synthesized from sugars (via glycolysis and the TCA cycle), or via carbon dioxide fixation from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), in the ‘dark’ steps of photosynthesis. Malic acid can be readily respired, or decarboxylated to PEP, via oxaloacetate in the gluconeogenesis of sugars. Not surprisingly, the malic acid content of berries changes more rapidly and strikingly than that of tartaric acid.

The degree and nature of acid conversions can vary widely, depending on the cultivar and environmental conditions. Nevertheless, several major trends are observed. After an initial, intense synthesis of tartaric acid in the ovary, both tartaric and malic acid contents slowly increase up to véraison. Subsequently, the amount of tartaric acid tends to stabilize, whereas that of malic acid declines. It is hypothesized that the initial accumulation of malic acid acts as a nutrient reserve, replacing glucose as the major respired substrate following véraison. This would explain the frequent rapid drop in malic acid content during the latter stages of ripening. However, it leaves unexplained the slow decline in malic acid content that is characteristic of vines grown in cool climates.

This pattern differs in some significant regards in V. rotundifolia. In muscadine cultivars, acidity, generated primarily by tartaric acid, declines from a maximum at berry set. Succinic acid, insignificant in V. vinifera cultivars, is a major component in very young muscadine fruit (Lamikanra et al., 1995). Its concentration declines rapidly thereafter. Malic acid content tends to increase up to véraison, declining thereafter.

It has long been known that grapes grown in hot climates often metabolize most or all of their malic acid before harvest. Conversely, grapes grown in cool climates retain much of their malic acid through to maturity. Although exposure to high temperatures activates enzymes that catabolize malic acid, this alone appears insufficient to explain the effect of temperature on berry malic acid content. Reduced synthesis, and possibly heightened gluconeogenesis, may play a role in the drop in malic acid content.

The decline in acid concentration during ripening is particularly marked when assessed on a fresh-berry-weight basis. This results from berry enlargement (water uptake) markedly exceeding the accumulation of tartaric acid and the metabolism of malic acid.

Shoot vigor is another factor influencing fruit acidity. Vigor (as indicated by an increased leaf surface/fruit ratio) is correlated with reduced grape acidity and higher pH (Jackson, 1986). This connection has usually been ascribed to the leaf and fruit shading associated with increased vigor. Nevertheless, even where shading was prevented, greater vigor reduced fruit quality (higher pH, decreased acidity, and lower °Brix) (Jackson, 1986).

In addition to environmental influences, hereditary factors also affect berry acid content. Some varieties, such as Zinfandel, Cabernet Franc, Chenin blanc, Syrah, and Pinot noir are proportionally high in malic acid, whereas others, such as Riesling, Sémillon, Merlot, Grenache, and Palomino are inherently higher in tartaric acid content (Kliewer et al., 1967).

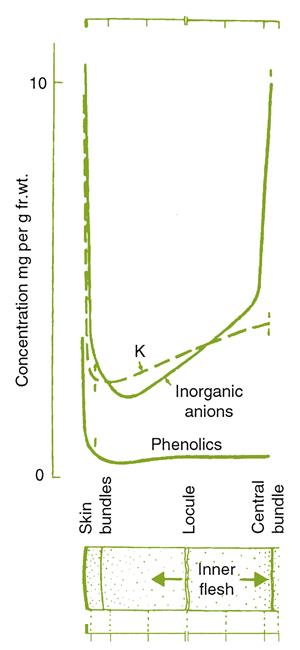

Tartaric acid tends to accumulate in the skin, with lower amounts relatively evenly distributed throughout the flesh (Fig. 3.42). By comparison, malic acid deposition is highest in the epidermis, low in the hypodermis, and increases again to a maximum near the berry locule. As ripening advances, these differences become less marked. By maturity, malic acid concentration in the skin, although low, may surpass that in the flesh. This appears to result from malate metabolism initiating around the axial vascular bundles and progressing outward.

The balance between the free and salt states of tartaric acid generally changes throughout maturation. Initially, most of the tartaric acid exists as a free acid. During ripening, progressively more tartaric acid combines with cations, predominantly K+. Salt formation with Ca2+ usually results in the deposition of calcium tartrate crystals in vacuoles of the skin (Ruffner, 1982). In contrast, malic acid generally remains as a free acid. The combination of the changing acid concentrations, and their salt states, results in the lowest titratable acidity occurring next to the skin. The highest titratable acidity normally exists next to the seeds.

The factors regulating tartaric and malic acid synthesis are poorly understood, despite the effect of temperature on malic acid degradation already noted. Nutritional factors can also considerably influence berry acidity and acid content.

Increased potassium availability results in slight increases in the levels of both acids. The amplification is probably driven by the need to produce additional acids to maintain ionic balance, associated with potassium uptake. Transport of K+ into cells requires the simultaneous export of H+. Although potassium uptake may enhance acid synthesis, it also results in a rise in pH, due to its association with free acids generating acid salts. This effect may be far from simple. For example, the proportion of free tartaric acid in skin cells may rise during maturation, even though up to 40% of potassium accumulation occurs in the skin. This apparent anomaly may result from a differential deposition of potassium and acids in vacuoles of the skin (Iland and Coombe, 1988).

Nitrogen fertilization enhances malic acid synthesis, but may induce a reduction in tartaric acid content. The increase in malic acid synthesis may involve cytoplasmic pH stability. Nitrate reduction (to ammonia) tends to raise cytoplasmic pH by releasing OH+ ions. The synthesis of malic acid could neutralize this effect. However, because of the low level of malic acid ionization in grape cells, and its metabolism via respiration during ripening, the early synthesis of malic acid does not permanently prevent a rise in pH during ripening.

Although both malic and tartaric acids appear to be involved in maintaining a favorable cellular ionic and osmotic balance, they tend to be stored in vacuoles to avoid excessive cytoplasmic acidity. Here, the differential permeability and distinctive transport characteristics of vacuolar membranes isolate the acids from the cytoplasm.

Potassium and Other Minerals

Potassium uptake during maturation affects both acid synthesis and ionization. Regrettably, the factors controlling potassium accumulation are poorly understood. It is transported in both the xylem and phloem, and can be redistributed from older to younger tissues. Its uptake increases after véraison, especially in the skin (Fig. 3.43). The skin, which constitutes about 10–15% of the berry weight, may contain up to 30–40% of the potassium content. The high correlation between potassium and sugar accumulation in the skin and flesh, respectively, fits the view that potassium acts as an osmoticum in skin cells, as sugar does in the flesh. Potassium accumulation also correlates with berry softening, associated with apoplast acidification. H+ ion export compensates for the import of K+ ions. Because potassium accumulation in vacuoles affects membrane permeability, potassium uptake may influence the release of malic acid, favoring its metabolism in the cytoplasm. Potassium is also a well-known enzyme activator. However, the reasons for the marked, but nonuniform, accumulation of potassium in skin cells (Storey, 1987) remain a mystery.

Concerning other minerals, boron tends to located in the skin and pulp, whereas calcium, manganese, phosphorus, sulfur, and zinc are primarily deposited in the seeds (Rogiers et al., 2006b).

Phenolics

In red grapes, flavonoid phenolics constitute the third most significant group of organic compounds. They not only donate the color to red wine, but also provide most of their characteristic taste and aging potential. White grapes have lower total phenolic contents and do not synthesize anthocyanins. Aside from seed phenolics, both red and white grapes contain most of their phenolics in the skin. Because seed phenolics are slowly extracted, the primary source of grape phenolics in most wines is the skin. They are primarily located in phenolic granules that accumulate in epidermal and hypodermal vacuoles (see Fig. 3.32). Those granules that adhere to the vacuolar membrane or cell wall are not easily extracted. Hydroxycinnamic acid esters of tartaric acid form the predominant phenolic components of the flesh. Their concentration tends to decline during ripening, whereas benzoic acid derivatives may increase (Fernández de Simón et al., 1992).

Pigmentation in most red cultivars is restricted to the outer hypodermal layers and epidermis (Walker et al., 2006). In white grapes, color comes from the presence of carotenoids, xanthophylls, and flavonols such as quercetin. Carotenoids accumulate predominantly in plastids, whereas flavonoid pigments are deposited in cell vacuoles. Similar pigments occur in red grapes, but the presence of anthocyanins donates the dominant color.

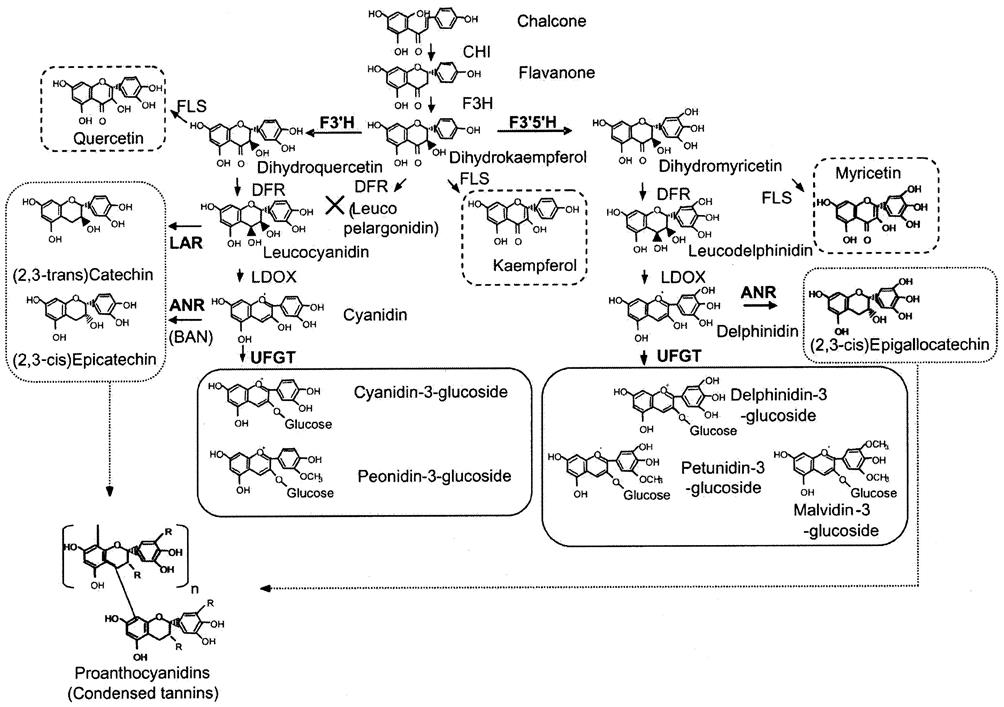

Anthocyanin synthesis is regulated in maturing grapes by two homologous, adjacent MYB transcription factor genes – VvMYBA1 and VvMYBA2. Activation of either can initiate anthocyanin synthesis, through the production of the regulatory protein they encode. This protein activates UFGT, a critical gene involved in anthocyanin synthesis. Two other MYB transcription factors occur in the locus, but appear not to be involved in anthocyanin synthesis, at least in the fruit (Walker et al., 2007).

Vitis vinifera cultivars typically possess at least one nonfunctional VvMYBA1 allele (Mitani et al., 2009). The presence of a retrotransposon, Gret1, prevents this allele, designated VvMYBA1a, from being activated (Walker et al., 2007). The functional VvMYBA1c allele lacks the retrotransposon. White cultivars typically are homozygous for the nonfunctional VvMYBA1a allele, as well as inactive alleles of the second regulator gene (VvMYBA2). The nonfunctional status of this second set of alleles relates to the presence of both a substitution and a deletion mutant in the gene (Walker et al., 2007). Pigmented cultivars (gray, pink, red to black) are more variable in allelic composition, but typically possess at least one functional MYB allele (Walker et al., 2007; This et al., 2007). Because the alleles function in a dominant/recessive manner, the presence of one functional allele can activate production of the enzyme UFGT, essential to anthocyanin synthesis (Fig. 3.44).

That the vast majority of white-berried cultivars possess identical versions of the VvMYBA1a allele, and the majority of red cultivars are heterozygous for the same allele (Walker et al., 2007), suggests that its inactivation by insertion of the Gret1 retrotransposon occurred early in the lineage of Vitis vinifera.

Exceptions to these trends include: Brown Frontignac and Black Frontignac, members of the normally white-colored Muscat family; rosé and red forms of Italia; and rare, rosé-colored clones of Chardonnay, and Gewürztraminer. With colored Frontignac cultivars, recombination may have reestablished a functional allele (Walker et al., 2007), while with Chardonnay and Gewürztraminer, excision of the Gret1 retrotransposon may be the source (This et al., 2007). White variants of red cultivars, such as Pinot blanc, appear to have lost the functional VvMYBA1c allele found in Pinot noir, but retain the inactive VvMYBA1a allele (Yakushiji et al., 2006). Brown and white versions of Cabernet Sauvignon (Plate 3.11) possess other genetic modification in their promoter genes, as does a white variant of Rhoditis (Lijavetzky et al., 2006). Additional sources of color variation can involve allelic variants of genes leading to, as well as directly involved in, anthocyanin synthesis (Fig. 3.44).

Several genes are directly involved in anthocyanin synthesis, with many others involved in earlier steps of flavonoid synthesis (Fig. 3.44). The latter genes are expressed in all tissues. However, UFGT, controlled by VvMYBA, is expressed only in skin cells of the fruit. It encodes the enzyme, UDP glucose-flavonoid 3-o-glucosyl transferase (UFGT). It directs anthocyanin glycosidation (Fig. 3.44). The relative transcription activities of genes encoding F3′5′H and F3′H appear to differentiate dark-colored (purple/blue) cultivars, possessing more trihydroxylated anthocyanins (malvidin, delphinidin, petunidin), from lighter, red-colored cultivars. The latter possess relatively more dihydroxylated anthocyanins (cyanidin and peonidin) (Castellarin and Di Gaspero, 2007). These pathways appear to be similar in all grapevine species studied: Vitis vinifera, V. aestivalis, and V. rotundifolia (Samuelian et al., 2009).

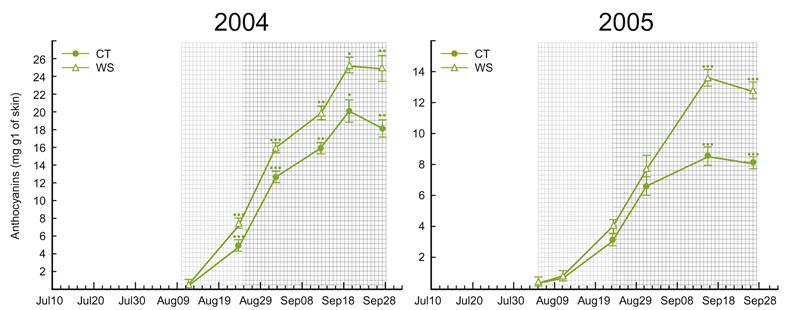

Expression of flavonoid synthesis genes, such as chalcone synthase and flavanone 3-hydroxylase, and those associated with anthocyanin synthesis, are enhanced in the presence of abscisic acid (Jeong et al., 2004; Peppi et al., 2008). Because high temperatures reduce abscisic acid content (Yamane et al., 2006), this probably explains why pigment formation is suppressed in hot weather. The critical flavonoid synthesis gene, UFGT, can be activated by application of 2-chloro-ethylphosphonic acid, an ethylene-releasing compound (El-Kereamy et al., 2003). Thus, activation of ethylene production by spraying grapes with a dilute solution of ethanol or methanol (Chervin et al., 2001) may explain its effect on enhancing grape coloration. In contrast, application of auxins (naphthaleneacetic acid, NAA) and shading suppressed the anthocyanin pathway regulator VvMYBA1 (Jeong et al., 2004).

The most intensely pigmented layers of the skin are typically the epidermis and first hypodermal layer. The next two layers contain smaller amounts of anthocyanins, and subsequent hypodermal layers tend to be sporadically and weakly pigmented (see Plate 3.11). Pigmentation seldom occurs deeper than the sixth hypodermal layer, except in teinturier varieties. These possess uniformly but weakly pigmented flesh (Hrazdina and Moskowitz, 1982). However, as skin cells senescence during overripening, pigmentation may diffuse from the skin into the flesh.

Anthocyanin synthesis is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum, where they are also glycosylated. The anthocyanins are subsequently transported for storage to adjacent vacuoles. The anthocyanin content in the outer hypodermal layer(s) soon approaches saturation. The anthocyanins subsequently combine in self-association or co-pigment complexes. The decline in anthocyanin content, occasionally observed in some cultivars as they approach maturity or overmature, is probably caused by β-glycosidases and peroxidases. These enzymes are isolated in vacuoles of the skin (Calderón et al., 1992), but may be released and become active as the grapes mature.

In addition to anthocyanins, all cultivars synthesize and accumulate variable amounts of catechins, their polymers (proanthocyanidins), flavonols, benzoic and cinnamic acids and their aldehyde derivatives, and tartrate esters of hydroxycinnamic acids. They occur in small amounts in the grape skin, and at even lower concentrations in the flesh. The predominant flavonol in V. vinifera tends to be kaempferol, whereas quercetin is the principal form in V. labrusca cultivars. Like anthocyanins, most flavonols are glycosidically linked, but to rhamnose and glucuronic acid in addition to, or instead of, glucose. The predominant hydroxycinnamic acid ester in grapes is caffeoyl tartrate, with smaller amounts of coumaroyl tartrate and feruloyl tartrate. As with most other chemical constituents, the specific concentrations can vary widely from season to season, and from cultivar to cultivar.

Flavonoid synthesis begins with the condensation of erythrose, derived from the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), with phosphoenolpyruvate, generated via glycolysis. The phenylalanine so generated is converted to the first of a series of phenylpropanoids, cinnamic acid. It is subsequently metabolized to coumaric acid and finally 4-coumaroyl-CoA. It contributes what is designated the B ring of flavonoids (see Illustration 6.10). Its binding with three acetates (derived from three malonyl CoA moieties) forms the A ring. The product, naringenin chalone, is the progenitor of grape flavonoids (Hrazdina et al., 1984). Subsequent alterations give rise to the full range of flavonoid phenolics. Some may become anthocyanins, while others give rise to flavonols as well as catechins, and their polymers, proanthocyanidins, and condensed tannins (Boss et al., 1996; Dixon et al., 2005). The latter are under the control of another MYB transcription factor, VvMYBPA1 (Bogs et al., 2007).

The synthesis of phenolics begins shortly after berry development commences. Some anthocyanins are synthesized early, but most production involves nonflavonoid and other flavonoid phenolics. Anthocyanin synthesis becomes pronounced only after véraison. The timing and degree of anthocyanin synthesis depends on a variety of factors, such as temperature, light exposure, water status, sugar accumulation, and genetic factors. After reaching a maximum (usually at grape maturity), anthocyanin concentration tends to decline. Tannin content tends to mirror changes in anthocyanin content, especially for those more readily extracted from the skin. A decline in solubility, associated with increasing polymer size, contributes to a reduction in fruit astringency.

Although the anthocyanin content of red grapes increases during ripening, the proportion of the various anthocyanins and their acylated derivatives can change dramatically (González-SanJosé et al., 1990). As the final combination can significantly influence the hue, intensity, and color stability of a wine, these changes have great enologic significance. Methylation of oxidation-sensitive o-diphenol1 sites improves anthocyanin stability. Thus, the monophenolic anthocyanins, peonin and malvin, are the most stable (see Fig. 3.44). Oxidative susceptibility is also decreased by bonding with sugars and acyl groups (Robinson et al., 1966). Independent factors can also affect color development, for example, mild water deficit, which activates abscisic acid synthesis, enhancing flavonol synthesis. Other flavonols that accumulate during ripening can contribute to the development of oxidation-resistant anthocyanin copigments.

The precise conditions that initiate anthocyanin synthesis during véraison are unknown. One hypothesis suggests that sugar accumulation provides the substrate needed for synthesis. The marked correlation between sugar accumulation in the skin and anthocyanin synthesis is consistent with this view. The accumulation of sugars, beyond the immediate needs of a tissue, often favors the synthesis of secondary metabolites. Nevertheless, sugar accumulation may act indirectly, through its effect on the osmotic potential of skin cells. In tissue culture, high osmotic potentials induce anthocyanin synthesis and subsequent methylation (Do and Cormier, 1991). However, as abscisic acid content correlates with sugar accumulation up to véraison, and its application at véraison enhances UFGT gene expression (Peppi et al., 2006), sugar accumulation may act through enhanced abscisic acid production (Ban et al., 2003). Alternatively, anthocyanin synthesis may be activated by changes in the potassium and calcium contents of skin cells. Potassium accumulation in skin cells, following véraison, is as nonuniform in cellular distribution as is initial anthocyanin synthesis. Conversely, a decline in calcium content is inversely correlated with anthocyanin synthesis; which of these alone or in combination, if any, ultimately triggers anthocyanin synthesis remains to be established.

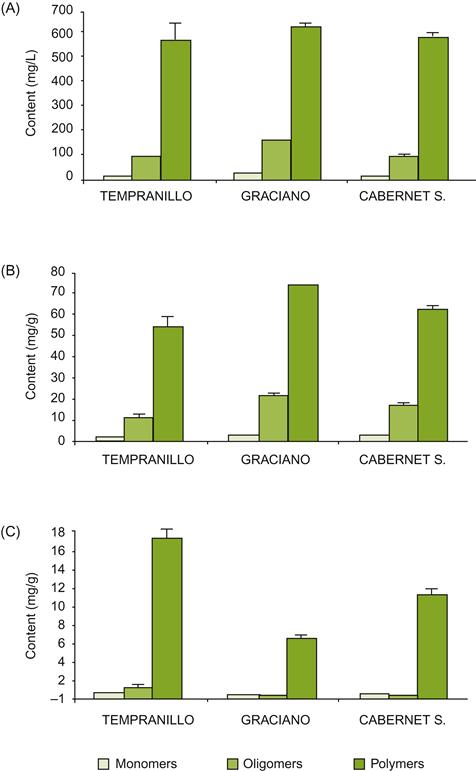

During berry development changes similar in scope to those involving anthocyanin composition affect skin tannins (Downey et al., 2003). There is often good correlation between sugar accumulation in the skin (not the flesh) and phenolic content (Pirie and Mullins, 1977). Phenol accumulation occurs both in cellular vacuoles (where polymerization appears less common), as well as in cell walls (Gagné et al., 2006). The degree of polymerization increases during ripening, as does the proportion of epigallocatechin subunits. This may also involve the inclusion of anthocyanin monomers in proanthocyanidin polymers (Kennedy et al., 2001). The average number of catechin subunits in skin tannins is about 25 in Shiraz, between 24 and 33 in Cabernet Sauvignon, and may reach up to 80 in Merlot. As the polymer size increases, tannin interaction with cell-wall constituents tends to decrease, at least in red grapes (Bindon and Kennedy, 2011). Presumably this change facilitates tannin extraction during fermentation. The binding potential of cell-wall polysaccharides (notably their rhamnogalacturonans) (see Hanlin et al., 2010) remains undiminished in the must, a feature that could reduce extraction during fermentation.

The principal extension subunits of skin tannins are (−)-epicatechin and (−)-epigallocatechin, with the terminal units being primarily (+)-catechin (Fig. 3.45), although this varies among cultivars (Mattivi et al., 2009). The epicatechins (cis isomers) are biosynthesized from anthocyanidins, whereas catechins (trans isomers) are derived from leucocyanidins (flavan-3,4-diols) (Fig. 3.44). These tannin monomers usually reach their peak content prior to véraison, probably because the precursors are subsequently redirected toward anthocyanin accumulation in red cultivars, as well as downregulation of abscisic acid synthesis, progressive polymerization, and dilution associated with water uptake. Variation in tannin concentration among cultivars, between different tissues, in degrees of bonding with cell-wall constituents, and in climatic conditions may relate to the relative expression of the multiple enzymes involved in flavonoid synthesis (Jeong et al., 2008). Multiple and distinct gene variants, as well as their regulators, occur in the grape genome. For example, three variants of chalone synthase are presently known, as well as two forms of chalone isomerase and flavanone 3-hydroxylase. Because of the extensive number of potential proanthocyanidins, discrepancies among the findings from different studies may have as much to do with the analytic techniques used for extraction and assessment as with legitimate variation.

Because the synthesis of nonflavonoid phenolics also tends to decline or cease following véraison, the concentrations of their esters also declines precipitously (Fig. 3.46). Dilution during berry enlargement is undoubtedly also involved. Nevertheless, some low-molecular-weight phenolic compounds (e.g., benzoic and cinnamic acid derivatives) may increase during ripening (Fernández de Simón et al., 1992).

In white grapes, the phenolic changes during ripening primarily involve hydroxycinnamic tartrates and catechins. Although the dynamics of hydroxycinnamic tartrate metabolism is unclear, their levels tend to decline strikingly during ripening (Lee and Jaworski, 1989). As the degree and nature of this decline are influenced by genetic and environmental factors, their role in the oxidative browning of wine can differ markedly from variety to variety, and from year to year. Catechin levels may rise following véraison, but decline again to low levels by maturity. Catechin monomers show a lower tendency to polymerize into large tannins in white than red cultivars. This may involve the partial inactivity of VvMYBPA transcription factor genes in white cultivars, but this is currently just speculation.

The predominant phenolics in seeds are flavan-3-ols (catechin, epicatechin, and their proanthocyanidin polymers). The proportion of catechin to epicatechin in proanthocyanidins varies considerably from cultivar to cultivar (Mattivi et al., 2009). Those in the seed wall are more polymerized and contain a higher proportion of epicatechin gallate than those in inner parts of the seed (Geny et al., 2003). Extension subunits are principally epicatechin and epicatechin gallate, with the terminal moiety being about equally epicatechin, epicatechin gallate and catechin (Downey et al., 2003; see Fig. 3.45). Correspondingly, the degree of galloylation in seed tannins is much higher than in skin tannins (13–29% vs. 3–6%, respectively) (Prieur et al., 1994; Souquet et al., 1996). In Shiraz, the average number of subunits in proanthocyanidin polymers is about 5. Although they constitute the major source of phenols in grapes (about 60% vs. 20% each in the skins and stalks), they dissolve more slowly and contribute less to the phenolic composition of wine, except when maceration during fermentation is prolonged. In the latter situation, their galloylation is likely to contribute to the coarseness of a wine’s astringency (Vidal et al., 2003). Extraction of seed tannin is reduced during wine production due to galloylation and the lipid content of the seed coats, at least until the alcohol content of the ferment facilitates their solubilization. The proportion of monomeric, oligomeric, and polymeric flavonols in seeds, skins, and wine from three cultivars is illustrated in Fig. 3.47.

After a pronounced increase during early berry development, the content of individual flavanols in the seeds declines, as they polymerize into procyanidins and condensed tannins. Because this is more marked in vines with low vigor (Peña-Neira et al., 2004), it may partially explain why wines made from these vines tend to be less bitter and astringent than equivalent wines made from grapes harvested from vigorous vines. Reduced astringency may also result from the association of pectins with procyanidins (Kennedy et al., 2001).

A group of stilbene phenolic compounds (phytoalexins) have attracted considerable attention recently. They are predominantly synthesized in response to localized stress, both biotic (e.g., infection) and abiotic. As such, they are part of the vine’s defense mechanism. The major phytoalexin in grapes is resveratrol (as well as its glycoside piceid). Smaller amounts of several related compounds, derived from resveratrol (pterostilbene and viniferins), may also accumulate.

Although activation of phytoalexin synthesis has generally been viewed as a response to stress, phytoalexins may also show constitutive synthesis and accumulation during ripening (Gatto et al., 2008). In this regard, there is marked variation between cultivars (Fig. 3.48), some being high producers, such as Pinot noir, whereas others are low producers, such as Nebbiolo. White cultivars generally produce less resveratrol. In a few cultivars, reduction in resveratrol content after véraison has been detected, coinciding with increased anthocyanin synthesis. Because the synthesis of anthocyanins and stilbenes have the same precursor (coumaroyl-CoA), it has been hypothesized that the synthesis of anthocyanins may limit the ability of berries to synthesize resveratrol (Jeandet et al., 1995). However, this seems inconsistent with the greater synthesis of stilbene phytoalexins in red than white grapes.

Pectins

One of the more obvious changes during berry ripening is softening. Softening facilitates juice release from the flesh, and the extraction of phenolic and flavor components from the skin. Softening results from a loosening of the bonds that hold plant cells together. This is associated with an increase in water-soluble pectins and a decrease in wall-bound pectins (Silacci and Morrison, 1990). These changes probably result from a combination of enzymatic degradation and a decline in pectin calcium content. The latter is associated with acidification of the apoplast. Calcium is important in maintaining the solid pectin matrix that characterizes most plant-cell walls. Calcium uptake essentially ceases following véraison. The involvement of cellulases and hemicellulases, in addition to that of pectinases, in softening is unknown.

Lipids

The lipid content of grapes consists of cuticular and epicuticular waxes, cutin fatty acids, membrane phospho- and glyco-lipids, and seed oils. Seed oils are important as an energy source during seed germination (a potential commercial by-product of winemaking), but seldom found in juice or wine. Their presence in significant amounts could generate rancid odors. Because the lipid concentration of the berry changes little during growth and maturation, synthesis appears to be equivalent to berry growth.

Membrane phospholipids constitute the most abundant grape lipid fraction, followed by neutral lipids. Glycolipids and sterols (primarily β-sitosterol) constitute the least common groups (Le Fur et al., 1994). The predominant fatty components are the long-chain fatty acids: linoleic, linolenic, and palmitic acids (Roufet et al., 1987).

Most of the cuticular layer is deposited in folds by anthesis and expand during berry growth (see Fig. 3.31B). In contrast, epicuticular wax plates are deposited throughout berry growth, commencing about anthesis (Rosenquist and Morrison, 1988). Most of the epicuticular coating consists of hard wax, composed of oleanolic acid dimers attached to the edges of plates consisting of C24–C26 alcohols, notably n-hexacosanol (Casado and Heredia, 1999). The content seems to be cultivar-dependent. For example, Palomino cuticular wax showed about 30% oleanolic acid (Casado and Heredia, 1999) vs. nearly 65% in Sultana (Fig. 3.49). The softer, underlying cuticle contains the fatty acid polymer, cutin. It consists primarily of C16 and C18 fatty acids, such as palmitic, linoleic, oleic, and stearic acids, and their derivatives. Cutin is embedded in a complex mixture of relatively nonpolar waxy compounds.

About 30–40% of the long-chain fatty acids of the berry are located in the skin. As such, they could potentially supply unsaturated fatty acids, used in the synthesis of yeast cell membranes during vinification. Regrettably, high concentrations of these phytosterols disrupt yeast cell membrane function (Luparia et al., 2004).

The relative concentration of fatty acids changes little during maturation, but the concentration of individual components can vary considerably. The most significant change involves a decline in linolenic acid during ripening (Roufet et al., 1987). This could have sensory impact, by reducing the likelihood of the development of a herbaceous odor in the wine.

Carotenoids are another important class of grape lipids. In red varieties, the concentration of both major (β-carotene and lutein) and minor (5,6-epoxylutein and neoxanthin) carotenoids falls markedly after véraison (Razungles et al., 1988). The decline appears to be partially the result of dilution during stage III berry growth, following cessation of synthesis. Because of their insolubility, most carotenoids remain with the skins and pulp following crushing. Nevertheless, enzymatic and acidic hydrolysis during maceration may release water-soluble carotenoid derivatives. These can include important aromatic compounds such as damascenone and β-ionone. In addition, the increasing norisoprenoid content in ripening Muscat of Alexandra grapes is correlated with a corresponding decrease in their carotenoid content (Razungles et al., 1993).

Nitrogen-Containing Compounds

Most of the information concerning grape proteins relates to enzymes and other soluble proteins associated with maturation. The most studied are those involved in anthocyanin synthesis and other phenolics of vitivinicultural interest, and polyphenol oxidases sequestered in cytoplasmic lysosomes. The other proteins that have received extensive study are those most associated with microbial protection, notably pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins. These have enologic interest due to their resistance to proteolytic breakdown and solubility at low pH values. These properties can lead to protein instability and eventual haze formation in bottled wine.

The concentration of grape soluble proteins increases markedly during maturation, reaching levels from 200–800 mg/L. In addition to changes during maturation, cultivars differ considerably in protein content (Tyson et al., 1982). This diversity is highest in nascent berries, becoming less variable as the fruit ripens. The composition also changes, with PR proteins becoming increasingly abundant after véraison. Their synthesis seemingly is activated by sugar accumulation (Tattersall et al., 1997). They may constitute 50–75% of the soluble protein content at maturity (Monteiro et al., 2007).

Pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins are produced in all plants and are highly diverse, having been classified into 14 structurally and functionally distinct categories. Those found in grapes include PR-5 (thaumatin-like proteins and osmotins), PR-2 (β-1,3-glucanases), and PR-3, -4, -8, and -11 (chitinases). They assist in defending against microbial invasion by creating transmembrane pores in the pathogen or degrading their cell-wall constituents (Ferreira et al., 2004). Although produced constitutively, various environment stresses as well as wounding can increase their synthesis. The most common PR proteins in ripe grapes are thaumatin-like and chitinase proteins (Robinson and Davies, 2000).

The most common simple peptide found in ripe grapes is glutathione, a tripeptide consisting of glutamine, cysteine, and glycine. Its accumulation begins at the onset of véraison and closely follows the rise in berry sugar content (Adams and Liyanage, 1993). It functions as an important antioxidant, by maintaining ascorbic acid in its reduced form. As such, glutathione is a significant grape juice constituent. In must, it reacts rapidly with caftaric acid and related phenolics as they oxidize, forming S-glutathionyl complexes.

The free amino acid content of grapes rises at the end of ripening, consisting primarily of proline and arginine. The latter is the principal form of nitrogen transported in the phloem. The relative concentrations of these two amino acids can vary up to 20-fold, depending on the variety and fruit maturity (Sponholz, 1991; Stines et al., 2000). Their ratio may shift from an early preponderance of arginine to proline at maturity (Polo et al., 1983), or the reverse (Bath et al., 1991). In many plants, proline acts as a cytoplasmic osmoticum (Aspinall and Paleg, 1981), similar to that of potassium. Whether proline accumulation has the same role in grapes is unclear.

Amino acids usually constitute the principal group of soluble organic nitrogen compounds released during crushing and pressing. Nevertheless, up to 80% of berry nitrogen content may remain with the pomace as nonsoluble components of the fruit.

Changes during ripening also occur in the level of inorganic nitrogen, notably ammonia. Ammonia may show either a decline (Solari et al., 1988), or an increase (Gu et al., 1991). Although a decline might appear to negatively affect fermentation, it probably is more than compensated by a simultaneous increase in amino acid content. Amino acids are incorporated by yeasts at up to 5–10 times that of the rate of ammonia. Their incorporation also alleviates the requirement of diverting metabolic intermediates to amino acid synthesis. However, as individual amino acids are accumulated by yeast cells at different rates, the specific amino acid content of the juice can significantly affect its fermentability. Some of the changes in nitrogen grape content are summarized in Fig. 3.50.

Aromatic Compounds

Until comparatively recently, most research focused on the major constituents of wine. Studies of its aromatic components lagged behind, due to a lack of analytic equipment possessing sufficient resolving power. Long-held views about the synthesis and location of aromatic compounds thus remained unsubstantiated. Developments and refinement in gas chromatography and other analytic procedures opened the floodgates for an unabated flow of new information. Eventually, this information may permit the scheduling of harvest relative to a predefined aromatic profile.

Initially, research centered on very aromatic cultivars – those whose aroma was based primarily on monoterpenes – as these were easier to analyze. Not only did they accumulate during ripening, but they were progressively converted into nonvolatile forms. Most bonded with sugars to form glycosides, whereas others were converted into their corresponding oxides, or polymerized into polyols (Wilson et al., 1986). Thus, mature grapes typically exhibited less aromatic character than their terpene content might suggest. Similar trends have also been noted with fragrant norisoprenoids and aromatic phenols (Strauss et al., 1987a).

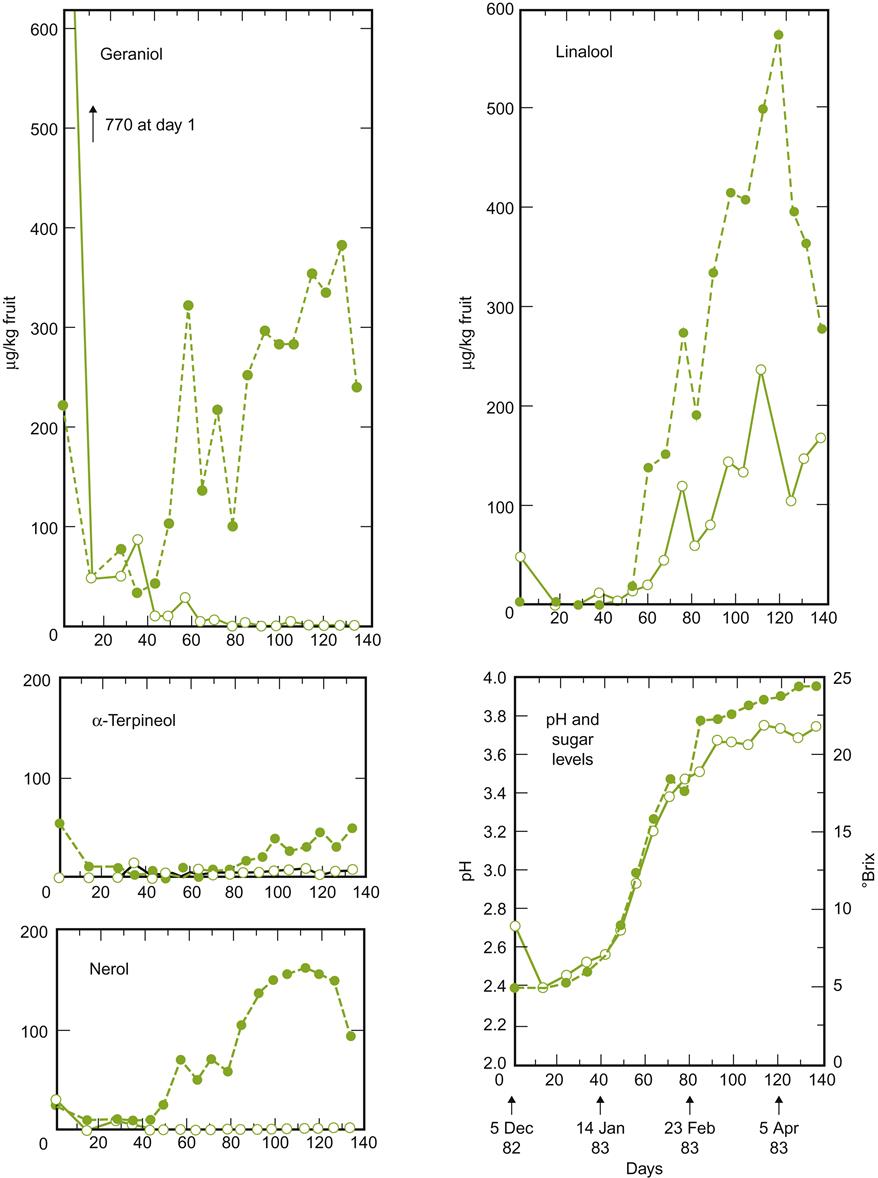

Glycoside formation often increases solubility of the aglycone (nonsugar) component, facilitating terpene accumulation in vacuoles. Similar complexes may also form at even higher concentrations in leaves (Skouroumounis and Winterhalter, 1994). Those synthesized in leaves appear not to be translocated to maturing fruit (Gholami et al., 1995). Details on the accumulation of free and bound terpenoids in Muscat of Alexandria are given in Fig. 3.51. The accumulation of most varietal flavorants (terpenes, norisoprenoids, volatile phenolics, etc.) tends to coincide with the beginning of véraison. For some constituents, this may occur very rapidly (Coombe and McCarthy, 1997; Fig. 3.52), followed by subsequent declines (Coelho et al., 2007).

Although most terpenes accumulate in the skin, notably geraniol and nerol, not all do. For example, free linalool and diendiol I occur more frequently in the flesh. In addition, the proportion of free and glycosidically bound terpenes often differs between the skin and the flesh.

In contrast, norisoprenoids, such as TDN (1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene), vitispirane, and damascenone, are localized predominantly in the flesh. They occur primarily in their more soluble, glycosidically bound forms, with only trace amounts of damascenone occurring in a free, volatile state. As with monoterpenes, their concentrations increase during ripening (Strauss et al., 1987b).

In addition to monoterpenes and norisoprenoids, other aromatic compounds are present in nonvolatile, conjugated (glycosidically bound) forms. One group consists of low-molecular-weight aromatic phenols. Examples in Riesling include vanillin, propiovanillone, methyl vanillate, zingerone, and coniferyl alcohol. Even phenolic alcohols, such as 2-phenylethanol and benzyl alcohol, may become glycosylated during ripening. Conjugated aromatic phenols have also been isolated from Sauvignon blanc, Chardonnay, and Muscat of Alexandria (Strauss et al., 1987a).

Another group of nonvolatile precursors of varietal significance are thiols, typically bound to glutathione. They apparently are the precursors of both free and S-cysteine thiol conjugates (Grant-Preece et al., 2010). The latter are metabolized by yeasts during fermentation, liberating their volatile thiol moiety. These play significant roles in the aroma of many varieties in the Cabernet family, notably Sauvignon blanc, and to a lesser extent in other cultivars, such as Pinot grigio and Riesling. Most of the precursors are localized in the skin, such as the precursors of 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol. In contrast, others are equally distributed in the skin and pulp (Peyrot des Gachons et al., 2002). Their concentrations can increase very rapidly, by up to 10-fold, during the latter stages of ripening (Capone et al., 2011).

Unlike the compounds noted above, others may remain in a free, volatile form through to maturity. An example is methyl anthranilate. It increases in concentration throughout the later stages of maturation (Robinson et al., 1949). In other instances, such as the methoxypyrazines, the concentrations may decline during maturation (Fig. 3.53). In this rare instance, the reduction is considered desirable. Methoxypyrazines can easily overpower a wine’s flavor, suppressing the perception of other compounds and, thus, aromatic complexity. Fermentation conditions do little to diminish methoxypyrazine content (Roujou de Boubée et al., 2002); nor does aging (Pickering et al., 2006). Maturation in oak may be beneficial, possibly due to methoxypyrazine absorption by the wood.

In several varieties, maturity affects the production of fusel alcohols and esters during subsequent fermentation. This has normally been interpreted as a result of the differing sugar contents of the grapes. However, as Fig. 7.37 shows, other poorly understood factors occurring during ripening may affect ester formation during fermentation.

Studies comparable with those on white grapes have not been conducted on red grapes. In some varieties, however, aroma development has been associated with ripeness and sun exposure. In Cabernet Sauvignon, the total volatile component of the fruit was considered to be about equally derived from the skin and flesh (Bayonove et al., 1974). However, because the skin constituted between 5 and 12% of the fruit mass, the aromatic concentration in the skin must be considerably higher than that in the flesh.

Although the synthesis of secondary metabolites in general tends to be correlated with the accumulation of sugars, the evolutionary rationale for this occurrence, if any, is unknown. In relation to fruit aromatics, though, synthesis and accumulation are presumably intended to attract herbivores and favor seed dispersal. Most mammals do not possess full color vision, possessing only two retinal, color-receptive pigments. Thus, for them, the color change usually associated with ripening, readily obvious to us (and birds), is hardly noticeable. In contrast, odor acuity is often highly developed, in contrast to our own poor attributes in this regard. Thus, changes in fragrance would be much more detectable, even at greater distance, than visual changes.

Cultural and Climatic Influences on Berry Maturation

Any factor affecting grapevine growth and health has the potential to influence the ability of the vine to nourish and ripen its crop. Consequently, most viticultural practices are directed at regulating these factors to achieve the maximum yield, consistent with grape quality and long-term vine health and productivity. Although macro- and mesoclimatic factors directly affect berry maturation, they are beyond the control of the grape grower. Thus, most attention is directed at microclimatic factors.

Yield

Because of the obvious importance of yield to commercial success, much research has focused on increasing fruit production. However, yield increases can reduce the ability of the vine to mature the fruit, or its potential to produce subsequent crops. This has led to an ongoing debate over the appropriate balance between grape yield, fruit quality, long-term vine health, and fiscal solvency.

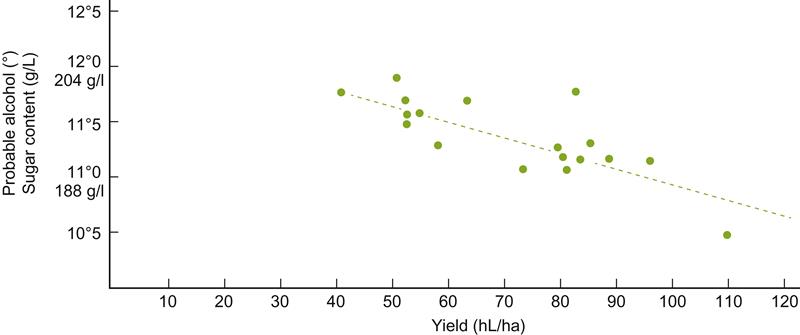

In France, yield is viewed so directly associated with grape and wine quality that theoretical maximum crop yields have been set for Appellation Control regions. This is partially justified by the negative correlation between increased yield and sugar accumulation (Fig. 3.54; see Fig. 4.4). Nevertheless, focusing attention simply on yield deflects attention from other factors of equal or greater importance, such as improved nutrition and light exposure (Reynolds et al., 1996). Elimination of viral infection often improves the vine's capacity to produce and ripen fruit. The yield quadrupling in German vineyards in the twentieth century (Fig. 3.55) is a dramatic, but not isolated, example of yield increases without comparable changes in ripeness. Clonal selection has also identified clones able to produce more as well as better-quality fruit (see Figs. 2.24 and 2.27). Improved fertilization, irrigation, weed and pest control, and appropriate canopy management can often further improve the capacity of the vine to produce more, and fully ripened, fruit (see the 'Management of Vine Growth' section in Chapter 4).

Although serious overcropping (>110–150 hL/ha) can clearly reduce wine quality, the specific cause-and-effect relationships are poorly understood. Factors frequently involved include delayed ripening, higher acidity, enhanced potassium content, reduced anthocyanin synthesis, diminished sugar accumulation, and limited flavor development. Achieving the ideal yield is one of the most perplexing, and probably quixotic, demands of grape growing. It depends not only on the grape variety and soil characteristics, but also on the type of wine desired and the specifics of the prevailing climate.

Although overcropping reduces grape and wine quality, and negatively affects subsequent yield and vine health, low yield does not necessarily equate with improved quality. Undercropping can prolong shoot growth and leaf production, increase shading, depress fruit acidity, and undesirably influence berry nitrogen and inorganic nutrient contents. Reduced yield also tends to induce the vine to produce larger berries. The reduced skin/flesh may negatively affect attributes derived primarily from the skin. This may partially explain that although reduced yield increased the intensity of ‘good’ wine aroma, it also enhanced taste intensity (Fig. 3.56). The enhanced taste intensity partially offset the benefits of the increased aroma. In addition, an overly intense aroma may compromise subtlety, resulting in diminished complexity and appreciation.

Attributes associated with the skin do not necessarily change in direct proportion to the surface area/volume ratio, when comparing various berry-size categories. The interaction can be complex and diverse, depending on the constituents assessed, how easily they are extracted, whether they are volatile or bound, and how they are measured (e.g., mg/berry, mg/g skin, mg/kg grape, and mg/cm skin) (Barbagallo et al., 2011).

In a study by Chapman et al. (2004), reduced yield was associated with a slight increase in the bell pepper odor (2-methoxy-3-isobutylpyrazine), bitterness, and astringency in Cabernet Sauvignon wines. In contrast, high yield generated wine moderately higher in red/black berry aromas, jammy flavors, and fruitiness. The effects were less marked than those found with Zinfandel wines (Fig. 3.56). Of particular interest was the observation that how yield variation was achieved was important (Chapman et al., 2004). Winter pruning, which had less effect on yield manipulation, had a greater effect on sensory characteristics than did the more marked yield variations generated by cluster thinning. It has generally been considered that wines produced from vines bearing light to intermediate crops are preferred (Cordner and Ough, 1978; Gallander, 1983; Ough and Nagaoka, 1984). Nevertheless, the yield/quality ratio is not necessarily constant within the mid-yield range (Sinton et al., 1978).

Excessive yield reduction, at least based on a per hectarage basis, can also jeopardize the financial viability of a vineyard. In contrast, reduced yield per vine, induced by higher density planting, has often been associated with improved grape quality. This advantage does come at considerable up-front costs, associated with vineyard establishment, as well as increased maintenance expenses.

An improved understanding of the complexities of yield/quality relationships presumably will come with a better grasp of the factors that lead to grape and wine quality (see the 'Criteria for Harvest Timing' section in Chapter 4). In addition, it is difficult to separate the indirect effects of vigorous growth, such as excessive canopy shading, from its more directs effects on yield and grape maturity. Canopy shading can influence fruit quality, even when the grapes themselves are not shaded (Schneider et al., 1990).

An excellent example of research in this area is provided by Cortell et al. (2005). Their study was conducted in a commercial vineyard, planted with vines of the same age, clone, and rootstock. Georeferencing permitted sampling and wine preparation from sites showing differing levels of vigor. Fruit from vines showing low vigor possessed higher levels of proanthocyanidins in the skin, as well as an increased proportion of epigallocatechin, proanthocyanin size, and pigmented polymers. These attributes were also reflected in the wines produced.

It is also essential that studies on yield/quality relationships investigate more than just their sensory effects on young wines. The effects of yield on wine-aging potential also requires verification. Regrettably, such long-term studies do not mesh well with the time limits of funding agencies, the need to publish frequently, nor the duration of graduate studies.

Another commonly held belief is that ‘stressing’ vines increases their ability to produce fine-quality wine. This view arose from the reduced vigor/improved grape quality association of some low-nutrient status, renowned, European vineyards. Nevertheless, balancing the leaf area/fruit ratio can improve the microclimate within and around the vine, increase photosynthetic efficiency, and promote fruit maturation and flavor development (see the ‘Yield/Quality Ratio' section in Chapter 4). Judicious balancing of the vegetative and reproductive functions of the vine can also favorably affect fruit acidity and pH.

Sunlight

As the energy source for photosynthesis, sunlight is without doubt the single most important climatic factor affecting berry development. Because sunlight contains ultraviolet, visible, and infrared (heat) radiation, and most absorbed radiation is released as heat, it is often difficult to separate light from temperature effects. Because of the early cessation of berry photosynthesis, most of the direct effects of sunlight on berry maturation, post-véraison, are either thermal or phytochrome-induced.

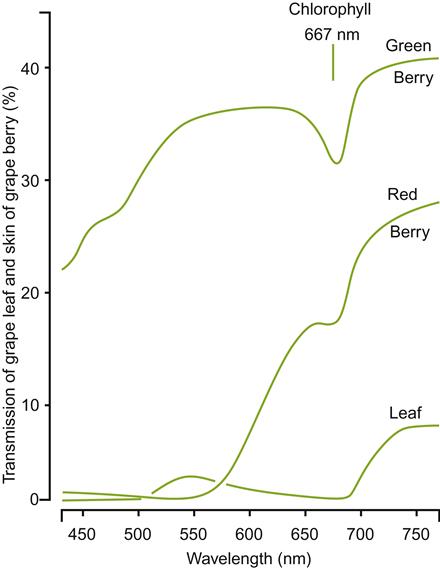

Because of the selective absorption of light by chorophyll, there is a marked increase in the proportion of far-red light within vine canopies. This shifts the proportion of physiologically active phytochrome (Pfr) from 60% in full sun, to below 20% in shade (Smith and Holmes, 1977). Evidence suggests that this may delay the initiation of anthocyanin synthesis, decrease sugar accumulation, and increase the ammonia and nitrate content in shaded fruit (Smart et al., 1988). The red/far-red balance of sunlight, and ultraviolet radiation, are known to influence flavonoid biosynthesis in many plants (Hahlbrock, 1981), including grapevines (Gregan et al., 2012). Whether sunflecks can offset the effects of shading is unknown, but is theoretically possible. Pr is more efficiently converted to Pfr by red light than is the reverse reaction (exposure to far-red radiation). However, because some plants also show high-intensity blue and far-red light responses, the effects of leaf shading may be more complex than the red/far-red balance alone might suggest.

Berry pigmentation, and its change following véraison (Fig. 3.57), can influence the Pr/Pfr ratio in maturing fruit (Blanke, 1990). Whether this significantly influences fruit ripening is unknown, but it could affect the activity of light-activated enzymes such as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), a critical enzyme in the metabolism of malic acid (Lakso and Kliewer, 1975).

Light exposure is generally essential for flavonol synthesis, and may promote anthocyanin synthesis, inducing deep coloration in red cultivars (Rojas-Lara and Morrison, 1989). It can also increase the relative proportion of anthocyanins and skin tannins to seed tannins. In this regard, the ratio has been proposed as an indicator of wine flavonoid composition, wine color, and quality (Ristic et al., 2010). Nevertheless, this finding is not universal, seemingly being varietally dependent. For example, Weaver and McCune (1960) found little difference in the pigmentation of berries covered (to prevent direct-sunlight exposure) and that of sun-exposed fruit. Downey et al. (2004) have confirmed this observation with Shiraz (Plate 3.12). High intensity light may actually decrease coloration in varieties such as Pinot noir (Dokoozlian, 1990).

Berry phenol content tends to follow the trends set by anthocyanin synthesis in response to light exposure (Morrison and Noble, 1990), but again not consistently (Price et al., 1995). Some of these differences may relate to macroclimatic factors, where increased exposure (and temperature) favors anthocyanin and phenolic synthesis in cool climates, but can have adverse effects in hot climates.

The influence of light exposure on the specific anthocyanin composition of grapes is largely unknown. In Nebbiolo, shading not only reduced anthocyanin accumulation, but increased the relative proportion of trihydroxylated forms (malvidin, delphinidin, petunidin) (Chorti et al., 2010). Because anthocyanins differ in their susceptibility to oxidation, changes in composition can be more important to color stability than total anthocyanin content. The involvement of light intensity and spectral quality on catechin synthesis appears not to have been studied, despite the involvement of catechins in color stability (see Chapter 6).