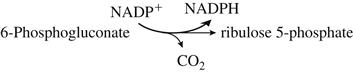

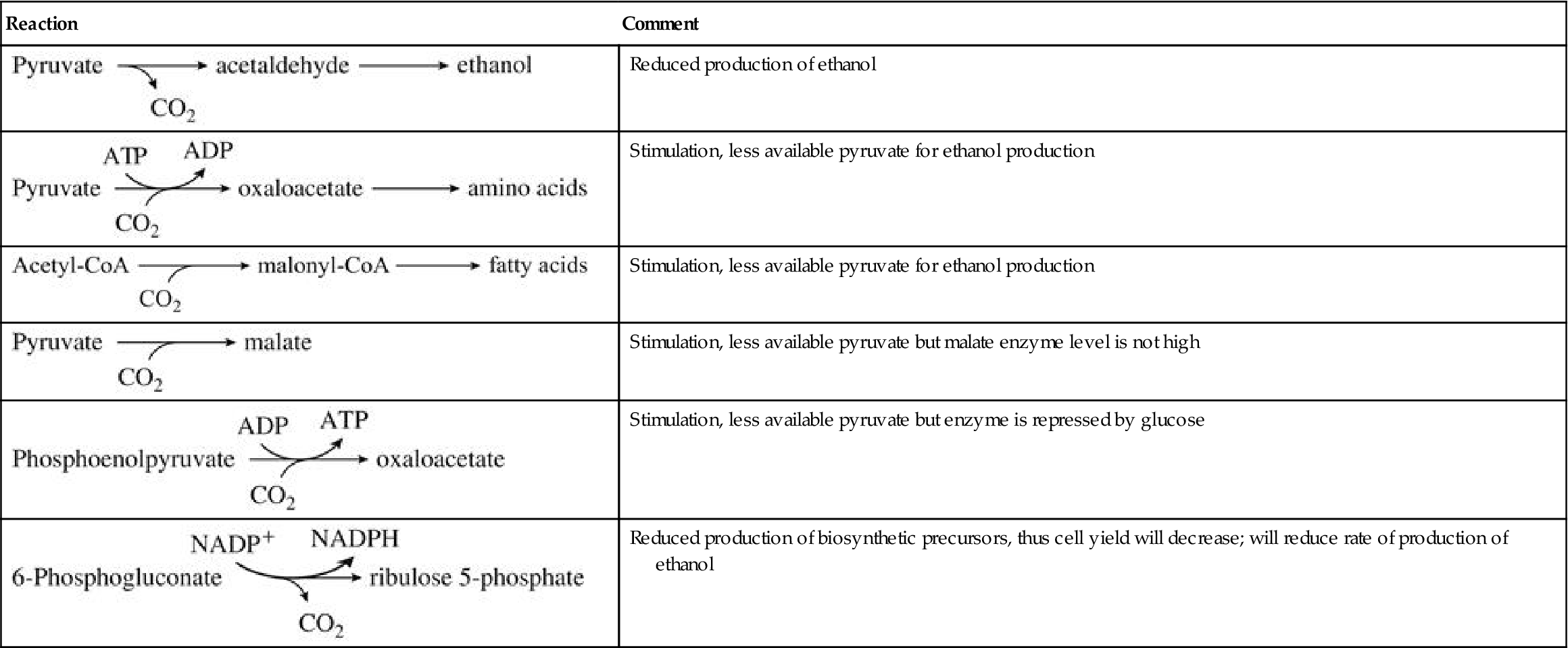

The metabolic intermediates needed for cell growth and maintenance are generally synthesized from components of the glycolytic and PPP pathways, and the TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle (see Fig. 7.20). However, during vinification, most of the TCA-cycle enzymes in the mitochondrion are inactive. Isozymic versions of most of these enzymes (located in the cytoplasm) take over the function of generating the necessary metabolic intermediates used in the biosynthesis of some amino acids and nucleotides (see Fig. 7.20). Full operation of the TCA cycle would produce an excess of NADH, disrupting the redox balance (respiratory oxidative phosphorylation is inoperative during fermentation). This is avoided because NADH, produced during the oxidation of citrate to succinate (the ‘right-hand’ side of the TCA cycle), can be oxidized back to NAD+ by reducing oxaloacetate to succinate (the ‘left-hand’ side of the TCA cycle). The result is redox balance. In addition, NADH generated in glycolysis may be oxidized in the reduction of oxaloacetate to succinate, rather than in the reduction of acetaldehyde to ethanol. In both scenarios, excess succinate is generated. This probably explains why succinate is one of the major by-products of yeast fermentation. In yeasts, the PPP functions primarily in the generation of particular amino acids and pentose sugars involved in the synthesis of nucleotides.

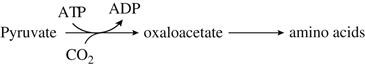

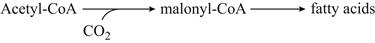

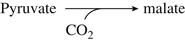

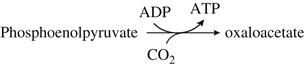

The replacement of TCA-cycle intermediates lost to biosynthesis probably comes from pyruvate. Pyruvate may be directly channeled through acetate, carboxylated to oxaloacetate, or indirectly routed via the glyoxylate pathway. The last pathway, if active, is probably functional only near the end of fermentation. Glucose suppresses the glyoxylate pathway. The involvement of biotin in the carboxylation of pyruvate to oxaloacetate probably accounts for its primary requirement by yeast cells.

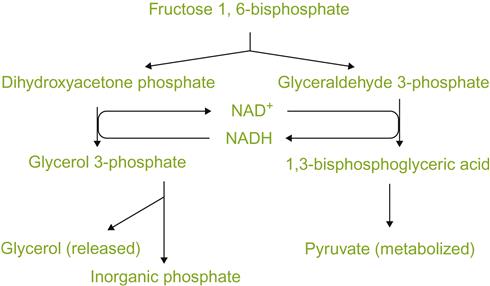

The accumulation of another major by-product of fermentation, glycerol, also has its origin in the need to maintain a favorable redox balance, as well as its function as an osmoticum. In some strains, glycerol accumulation appears to enhance the synthesis of another osmoticum, trehalose (Li et al., 2010). The importance of glycerol synthesis to redox balance is suggested by the inability of mutants, defective in glycerol synthesis, to grow under anaerobic conditions (Nissen et al., 2000). In addition, Roustan and Sablayrolles (2002) present evidence suggesting that glycerol synthesis, at least during the stationary phase, is associated with redox balance by eliminating excess reducing power. The reduction of dihydroxyacetone phosphate to glycerol 3-phosphate can oxidize the NADH generated in the oxidation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate in glycolysis (Fig. 7.23). However, the coupling of these two reactions does not generate ATP, and is therefore an energy-neutral form of glucose fermentation. This is in contrast to the net production of two ATP molecules, and release of two CO2 molecules, during the fermentation of glucose to ethanol. The separate functions of redox balance and osmotolerance appear to be regulated by different isozymes of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GPD1 and GPD2 (Ansell et al., 1997).

The presence of sulfur dioxide increases the production of glycerol. This probably comes from an indirect effect, requiring an alternative route to regenerate NAD+. When sulfur dioxide binds with acetaldehyde, its reduction to ethanol is inhibited, blocking the usual means by which alcoholic fermentation regenerates NAD+.

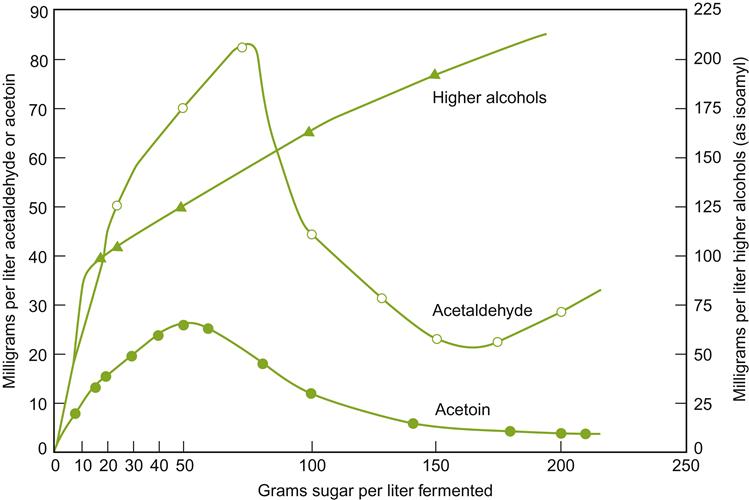

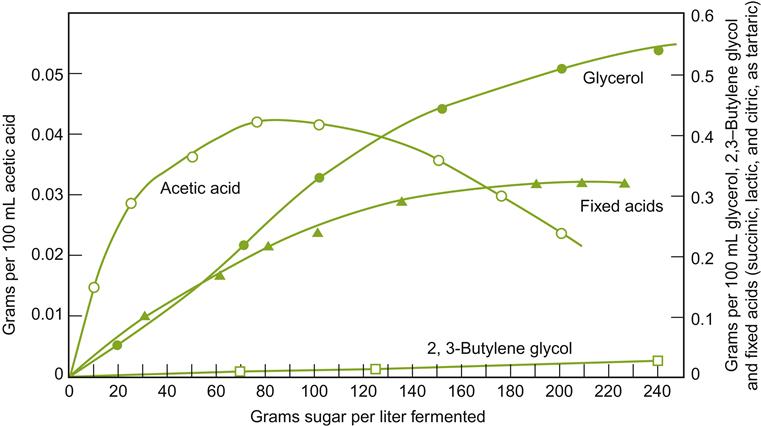

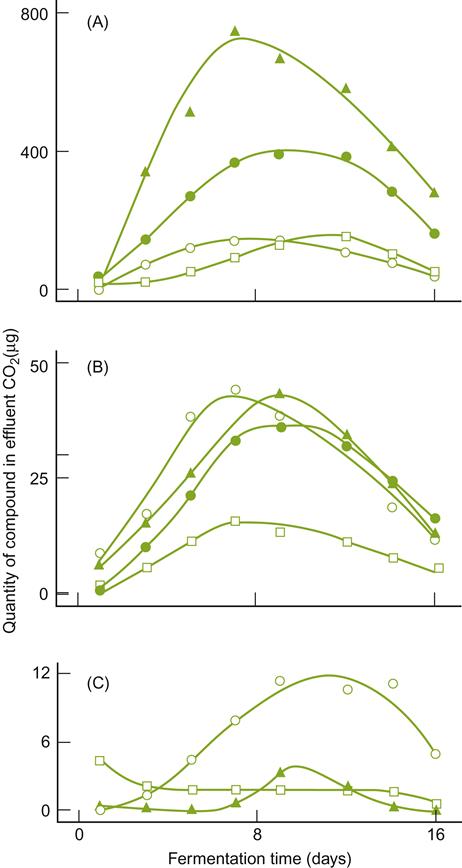

Throughout fermentation, yeast cells adjust physiologically to the changing conditions in the juice/must to produce adequate levels of ATP, maintain favorable redox and ionic balances, and synthesize necessary metabolic intermediates. Consequently, the concentration of yeast by-products in the cytoplasm and juice changes continuously throughout fermentation (see Figs. 7.21 and 7.22). Because several by-products are aromatic, for example acetic acid, acetoin (primarily by conversion from diacetyl), and succinic acid, their presence can affect bouquet development. The accumulation of acetyl CoA (as a result of limited activity of Krebs Cycle enzymes) may explain the accumulation and release of acetate esters during fermentation. The alcoholysis of acetyl CoA (and other acyl SCoA complexes) during esterification would release CoA for other metabolic functions. In addition, the formation of other aromatics, notably higher alcohols, reflects the relative availability of amino acids and other nitrogen sources in the juice. Adequate availability permits amino acids to be used as an energy source, or generates organic acids, fatty acids, and reduced-sulfur compounds.

Although all strains of S. cerevisiae possess the same set of enzymes, their catalytic activities may vary due to allelic differences. In addition, slight differences in regulation, or gene copy number, mean that any two strains are unlikely to respond identically under the same conditions. This variability undoubtedly accounts for many of the subtle, and not so subtle, differences between fermentations conducted by different strains. For example, overexpression of cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenase increases not only the accumulation of malic acid, but also fumaric and citric acids (Pines et al., 1997). In addition, overexpression of glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase not only results in a marked increase in glycerol production, but also augments the accumulation of acetaldehyde, pyruvate, acetate, 2,3-butanediol, succinate, and especially acetoin (Michnick et al., 1997). This is the mechanism by which glycerol production may be enhanced by heat shocking reactivated yeast before inoculation (Berovic and Herga, 2007). The shift in metabolism toward glycerol synthesis is of enologic interest as it could result in ‘normal’ alcohol contents in wines produced from grapes having high °Brix values. This is becoming more common, as delaying harvest to achieve maximum flavor development can lead to table wines possessing up to 15% ethanol.

Influence on Grape Constituents

Yeasts have their major effect on the sugar content of the juice or must. If fermentation goes to completion, only minute amounts of fermentable sugars remain (preferably≤1 g/liter). Small amounts of nonfermentable sugars, such as arabinose, rhamnose, and xylose, also remain (∼0.2 g/liter). These small quantities have no sensory significance and leave the wine tasting ‘dry.’

Yeasts may increase pH by metabolizing malic acid to lactic acid. However, the proportion converted is highly variable, differing among strains by 3–45% (Rankine, 1966). Some strains of S. paradoxus can also degrade malic acid up to 40% (Orlic et al., 2007). Some strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae can also synthesize malic acid, maximally at 25 °C (Farris et al., 1989). However, this is a more common property of S. bayanus var. uvarum.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe can completely decarboxylate malic acid to lactic acid (Benito et al., 2013). It also has the potential to limit urea and alcohol accumulation. The former reduces the potential for ethyl carbamate production, and the latter the high alcohol contents associated with overmaturation of grapes to achieve higher flavor potential. Nonetheless, this yeast has been little used because its sensory impact has generally, but not consistently, been viewed as negative. The chemical reasons for this are unclear. Delaying its inoculation until after S. cerevisiae has been active for several days, or has completed fermentation, apparently reduces its potential negative impact of (Carre et al., 1983). Immobilization appears to be an alternative and effective approach that does not spoil the wine’s character (Silva et al., 2003). It also permits greater control over the degree of deacidification.

During fermentation, the release of alcohols and other organics helps dissolve compounds from seeds and skins. Quantitatively, the most significant chemicals extracted are anthocyanins and various flavonoid phenolics, notably tannins. The latter are partially dependent on the solubilizing action of ethanol. Anthocyanin extraction often reaches a maximum within 3–5 days, when the alcohol content has reached about 5–7% (Somers and Pocock, 1986). As the alcohol concentration continues to rise, color intensity may begin to fall. This can result from the coprecipitation of anthocyanins with grape and yeast cells, to which they may bind. Nevertheless, the primary reason for color loss appears to be disruption of weak anthocyanin complexes present in the juice. Freed anthocyanins may convert into uncolored states. Although extraction of tannins occurs more slowly, their content often reaches higher values than anthocyanins. Tannin extraction from stems (rachis), if present, may reach a plateau after about 7 days. Seed tannins are the slowest to be liberated; their accumulation may still be active after several weeks (Siegrist, 1985).

Ethanol also aids the solubilization of certain aromatic compounds from grape cells. Unfortunately, little is known about the dynamics of the process. Conversely, ethanol decreases the solubility of other grape constituents, notably pectins and other carbohydrate polymers. The pectin content may fall by upward of 70% during fermentation.

As noted, the metabolic action of yeasts produces many important wine volatiles, notably higher alcohols, fatty acids, and esters. Yeast metabolism may also degrade some grape aromatics, notably aldehydes. This potentially could limit the expression of the herbaceous odor generated by C6 aldehydes and alcohols produced as a consequence of oxidation during the grape crush. Yeasts can also influence wine flavor by decarboxylating hydroxycinnamic acids to their equivalent vinylphenols. More significantly, fermentation may play a major role in the liberation of varietal aromatics, notably those bound in complexes with glycosides (Williams et al., 1996) or cysteine (Tominaga et al., 1998). Because yeast strains differ significantly in these attributes (Howell et al., 2004), strain choice can either enhance or diminish varietal expression.

Indirect effects of yeast action include wine color modification (Eglinton et al., 2004; Medina et al., 2005). This may involve pigment loss, by adherence to grape cell remnants and yeast mannoproteins, or color stabilization by the release of carbonyls, such as pyruvic acid and acetaldehyde, and the generation of vinylphenols. Because yeast strains also vary in these characteristics, strain selection can influence color depth and stability in red wines (Bartowsky et al., 2004b; Morata et al., 2006).

Yeasts

Classification and Life Cycle

Yeasts are a diverse group of fungi characterized by possessing a unicellular growth habit. Cell division may involve either budding (extrusion of a daughter cell from the mother cell) (Plate 7.6) or fission (division of the mother cell into one or more cells by localized ingrowths). Occasionally, yeasts may form short chains. Yeasts are also distinguished by possessing a single nucleus – in contrast to the frequently variable number of nuclei found in filamentous fungi. In addition, the composition of their cell walls is unique. The major fibrous cell-wall component of most fungi, chitin, occurs only as a minor component in yeast cell walls. It is localized to the bud scar, the site at which daughter cells are produced. The major constituent of yeast cells consists of chains of glucose molecules, specifically bonded together to form β-1,3-D-glucans. Also present are mannoproteins, complex polymers of the sugar, mannose, and particular proteins. These are covalently linked to either β-1,3-D-glucans or smaller amounts of glucose molecules bonded together into β-1,6-D-glucan chains.

Although characterized by a distinctive set of properties, yeasts are not a single evolutionarily related group. A yeast-like growth habit has evolved independently in at least three major fungal taxa – the Zygomycota, Ascomycota, and Basidiomycota. Only yeast members of the Ascomycota (and related imperfect forms) are significant in wine production. Most imperfect yeasts, i.e., those that have lost the ability to undergo sexual reproduction, are derived from ascomycete yeasts. Under appropriate conditions, the cells of most ascomycete yeasts differentiate into asci – the structures in which haploid spores are produced through meiosis and cytoplasmic division.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae and related species, four haploid spores are produced as a consequence of meiosis (Fig. 7.24). After rupture of the ascal wall (originally the mother cell wall), spores typically germinate to produce haploid vegetative cells. Those of opposite mating type usually fuse shortly after germination to reestablish the diploid state. Fusion may occur even before rupture of the ascal wall. Although individual cells only have the capacity to grow and bud about eight times before dying, newly budded cells have the same capacity as the mother cell – to produce (bud) eight new cells. Cellular death apparently results from disruption caused by the accumulation of circular copies of rDNA in the nucleus (Sinclair and Guarente, 1997). Under appropriate conditions, diploid cells can differentiate into asci and ascospores. However, wine strains rarely express this potential, at least in must or wine. Ascal development is suppressed by high concentrations of glucose, ethanol, and CO2.

If sporulation is desired, as in breeding experiments, nutrient starvation, the addition of sodium acetate, or both can induce ascospore production in S. cerevisiae. Bicarbonate accumulation in the growth medium also acts as a meiosis-promoting factor (Ohkuni et al., 1998).

Until the late 1970s, yeast classification was, by necessity, based on physiological properties and the few morphological traits readily observable under the light microscope. These have now been supplemented with nucleotide sequence analysis and DNA–DNA hybridization. These procedures will hopefully open a new period of more stable classification, based on evolutionary relationships.

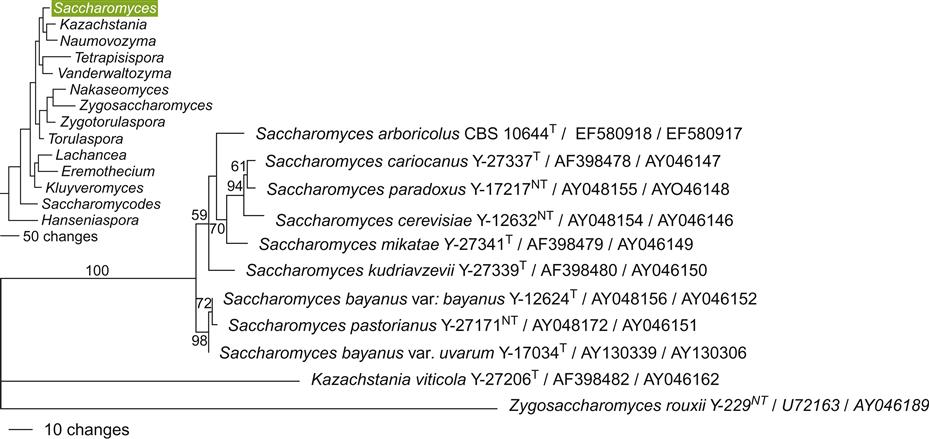

In most recent taxonomic treatments (e.g., Kurtzman et al., 2011), many named species of Saccharomyces have been reduced to synonymy. This does not refute the differences formerly used to distinguish these ‘species,’ but rather indicates that they are either minor genetic variants or genetically unstable. Most of these former species are viewed as physiological races of recognized species, or occasionally members of different genera. For example, S. fermentati and S. rosei are considered to be strains of Torulaspora rosei. Species such as S. bayanus, S. uvarum, and S. pastorianus (S. carlsbergensis) are variously viewed as subspecies of S. cerevisiae (Nguyen and Gaillardin, 2005), as distinct varieties of a separate species (S. bayanus var. bayanus or S. bayanus var. uvarum), or species (S. pastorianus) by Kurtzman et al. (2011). Figure 7.25 illustrates a modern interpretation of the relatedness among Saccharomyces and related genera, species, and strains.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and related species (Saccharomyces sensu stricto) are apparently evolved from an ancient chromosome doubling (autopolyploidy) (Wolfe and Shields, 1997; Wong et al., 2002). This was followed by inactivation or loss of most of the duplicate chromosomes (diploidization). Although this is estimated to have occurred millions of years ago, hybridization and polyploidy still occur within the genus (de Barros Lopes et al., 2002; Naumova et al., 2005). For example, S. pastorianus is thought to be an alloploid hybrid between S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus, or another subspecies. A list of accepted names and synonyms for some of the more commonly found yeasts on grapes or in wine is given in Appendix 7.1. Differences between some of the physiological races of S. cerevisiae (formerly given species status) are noted in Appendix 7.2.

Yeast Identification

Identification procedures, based on mitochondrial DNA, PCR, and other molecular technologies, now permit the rapid (hours vs. days) identification of species, and even strains from small samples (Cocolin et al., 2000; Martorell et al., 2005). Without these procedures it would be impossible to know what strains were actually conducting fermentation, or to detect the dynamics of strain fluctuation during fermentation. Thus, not only have these techniques been a boon to research, but they also have spawned renewed interest in endemic strains as potential sources of regional or site-specific wine individuality.

The speed and precision of molecular techniques are replacing traditional identification procedures, based on physiological properties and production of the sexual phase. Molecular techniques are also particularly useful in the early detection of potential spoilage organisms. They are also being applied to assessing the dynamics of physiological changes during fermentation. Regrettably, these procedures are costly, technically demanding, and currently only available in research centers, commercial laboratories, or the largest of wineries.

Alternative techniques for the differentiation between fermentative and spoilage yeasts involve free fatty acid analysis, gas chromatography, or pulsed-field electrophoresis. However, these are equally unavailable to the vast majority of wineries. Computer-based analysis of data via synoptic keys, in contrast to structured dichotomous keys (Payne, 1998), would facilitate identification using standard culture techniques. In their absence, specialized culturing procedures, such as those given by Cavazza et al. (1992), or the standard methods noted in Kurtzman et al. (2011) are effective, but not speedy.

Standard procedures require that the organism be isolated as a single cell and grown on laboratory media. This is typically achieved by dilution from the source, containing upward of a billion cells/mL. Typically, selective media are required for the isolation of different species. It is essential that each species or strain be isolated and cultured individually. Identification is based on the capacity to grow with or without particular nutrients. Depending on how the isolation is done, data on the number of viable cells of each species and strain may be obtained. However, just because an organism is isolated does not necessarily mean that it was growing or physiologically active in the juice, must, or wine. Conversely, inability to culture an organism does not necessarily mean it was not present in a viable state. Yeast cells may survive for extended periods in a dormant (unculturable) state (Cocolin and Mills, 2003).

Because of the time, equipment, and experience required for the effective use of even traditional identification techniques, they are not discussed here. In all but large wineries, yeast identification is typically contracted out to commercial laboratories.

Yeast Evolution and Grape Flora

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is undoubtedly the most important of all yeast species. In various forms, it functions as the wine yeast, brewer’s yeast, distiller’s yeast, and baker’s yeast. Laboratory strains are extensively used in industry and in fundamental studies on genetics, biochemistry, and molecular biology. For all its importance, the natural habitat of S. cerevisiae is only now becoming clear. Current evidence indicates that its indigenous niche is the sap and bark of oak trees, and possibly adjacent soil. In these sites, it co-inhabits with a sibling species, S. paradoxus. The latter is often viewed as the progenitor of S. cerevisiae. This view is supported by their extensive genetic and physiological similarities, equivalent natural habitats, and ability to ferment wines to dryness (Redžepović et al., 2002). Other Saccharomyces species also inhabit bark, notably oak bark, for example, S. kudriavzevii and S. uvarum (Sampaio and Gonçalves, 2008).

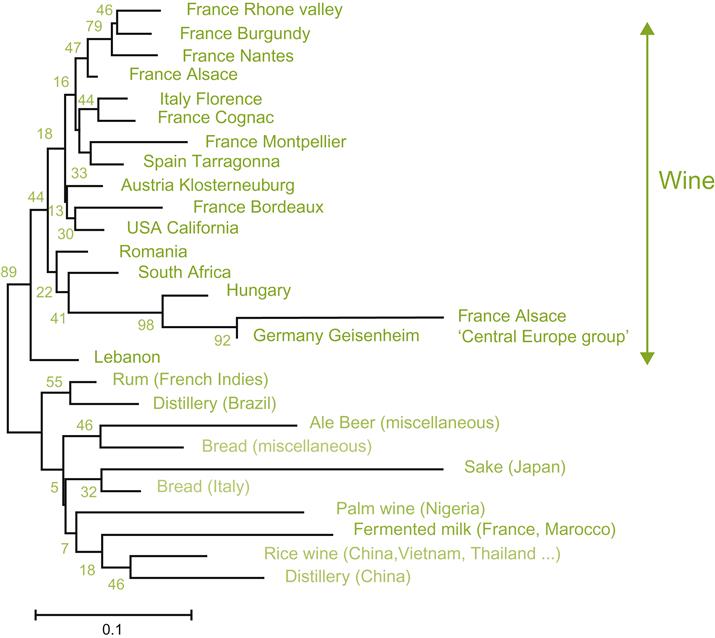

Wild strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. paradoxus differ primarily by being reproductively isolated (i.e., having an inability to mate under natural conditions); possessing genomic sequence divergence; and showing different thermal growth profiles. They also vary in that wild strains of S. cerevisiae demonstrate limited genetic distinction across continents, vs. the partial reproductive isolation between dispersed populations of S. paradoxus (Sniegowski et al., 2002; Kuehne et al., 2007). Wild strains of S. cerevisiae are distinguishable from wine strains by the absence of chromosomal polymorphisms, by being prototrophic, and by being sporulation-proficient. In contrast, wine strains exhibit significant DNA sequence diversity, and chromosome length polymorphisms, often possess auxotrophic or lethal mutants, express considerable heterozygosity, and show variable spore viability (see Mortimer, 2000). Currently, there is no consensus as to the evolutionary relationship between wild and domesticated strains of S. cerevisiae. Nevertheless, it appears that feral S. cerevisiae gave rise to two domesticated lines, one that developed into wine yeasts (and subsequently beer and bread yeasts). The other line gave rise to saké yeasts (Fay and Benavides, 2005). The greatest diversity was found in yeasts derived from fermented products in Africa, lending support to an ‘out-of-Africa’ origin of domesticated yeast (Fay and Benavides, 2005). Did humans unsuspectedly take S. cerevisiae along with them when our ancestors migrated out of Africa? Relative to wine yeasts, specifically, present data fits a Near Eastern center of origin (Fig. 7.26).

Although Saccharomyces cerevisiae has occasionally been isolated from fruit flies (Drosophila spp.), and may be transmitted by bees and wasps, the importance of insect dispersal is unresolved (Wolf and Benda, 1965; Phaff, 1986). S. cerevisiae is usually absent or rare on healthy grapes. Even in long-established vineyards, the isolation of S. cerevisiae (in small numbers) occurs only near the end of ripening. Mortimer and Polsinelli (1999) estimate about one healthy berry per thousand carries wine yeasts. However, on surface-damaged fruit, the frequency may rise to one in four (1×105 to 1×106 yeast cells/berry). In Croatia, Redžepović et al. (2002) found that S. paradoxus was more frequently found on grapes than S. cerevisiae. A comparison of the attributes contributed to wine by S. paradoxus vs. S. cerevisiae is provided by Majdak et al. (2002) and Orlić et al. (2010).

Strains of the related species, Saccharomyces bayanus, can also conduct effective alcoholic fermentations. Nevertheless, they are less encountered, and their use typically associated with special winemaking situations. For example, S. bayanus var. bayanus has properties especially well adapted to the production of sparkling wines and fino sherries. S. bayanus is also well adapted to fermenting white wines from relatively neutral flavored grapes grown in warm climates. It tends to produce little volatile acidity, augments the malic acid, succinic acid, and glycerol contents, and generates more aromatic alcohols and ethyl esters (Castellari et al., 1994; Antonelli et al., 1999). For cool fermentations (below 15 °C), the cryotolerant S. bayanus var. uvarum is of particular value. It is often involved in the production of tokaji, amarone, and sauternes wines. In some regions, such as Alsace, it has been reported to be the predominant fermentative yeast (Demuyter et al., 2004). The origin of these two species (often considered subspecies of S. cerevisiae) is unknown, as are their natural habitats. Wild strains have occasionally been isolated from the caddis fly, some mushroom species, and hornbeam tree exudate (Carpinus).

General attribute tendencies of the different species, subspecies, and strains of wine yeast have been investigated, but precise prediction of their actions under specific conditions is impossible. Individual experimentation over several years is the only way to determine their effects under in-house conditions.

Although wine yeasts rarely occur in significant numbers on the fruit, leaves, or stems of grapevines, other yeast species are frequently found. These include species of Hanseniospora (Kloeckera), Candida, Pichia, Hansenula, Metschnikowia, Sporobolomyces, Cryptococcus, Rhodotorula, and Aureobasidium. Their population numbers change during fruit ripening (Renouf et al., 2005), increasing markedly during the last few weeks of maturation. Endemic yeasts may be found on the fruit pedicel, but occur more frequently on the callused terminal ends, the receptacle. They are most frequently isolated from around stomata on the fruit, or next to cracks in the cuticle. In the last site, they routinely form small colonies (Belin, 1972). They presumably grow on nutrients seeping out of openings in the fruit, receptacle, and pedicel. Yeasts do not grow on the plates of wax that cover much of the berry surface, the matte-like bloom. In fact, yeasts cease to grow where they come in contact with the waxy cuticular plates.

Commonly, the cells are dormant or only slowly reproducing. This unquestionably results from the dry state of the cuticle. Microbes require at least a thin coating of water to be metabolically active. This occurs only during rainy spells, or when fog or dew condenses on grape surfaces. In contrast, damaged fruit surfaces, where juice may escape, may be slightly hygroscopic, providing a more favorable, albeit highly osmotic, site for yeast (and bacterial) growth.

As noted, grapes do not appear to have been the natural (ancestral) habitat for S. cerevisiae (or its progenitor). Nonetheless, winery equipment, and the winery itself, act as a significant inoculum source for spontaneous fermentations (Ciani et al., 2004; Santamaría et al., 2005). This is suggested by the repeat isolation of one or a few dominant strain(s) from particular wineries. Outside the winery, strain spread seems limited, and occurs only over short distances (Valero et al., 2005). A possible exception occurs where pomace is spread as a vineyard soil conditioner. In addition, regional strains isolated from vineyards often differ (Khan et al., 2000). Thus, this lends credence to the view that endemic yeast populations could contribute to a site’s regional character.

The most frequently occurring yeast species on mature grapes is Kloeckera apiculata. In warm regions, the perfect state of Kloeckera (Hanseniaspora) tends to replace the asexual form. Filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus, Botrytis, Penicillium, Plasmopara, and Uncinula, are rarely isolated, except from diseased or damaged fruit. Similarly, acetic acid bacteria are usually found in significant numbers only on diseased or damaged fruit.

Under most conditions, especially where must is inoculated with a particular strain of S. cerevisiae, the indigenous yeast flora has often been viewed to be of little significance in winemaking. The acidic, highly osmotic conditions of grape juice were thought to retard the growth of most yeasts, fungi, and bacteria. Also, the rapid development of anaerobic conditions and the accumulation of ethanol compromise the growth of competitive species. Nevertheless, in musts low in sugar content, the activity of yeasts less tolerant of high sugar and ethanol contents may be important (Ciani and Picciotti, 1995). Diseased grapes also have significantly modified and enhanced populations of epiphytic yeasts. These can markedly affect the outcome of fermentation, even with inoculation.

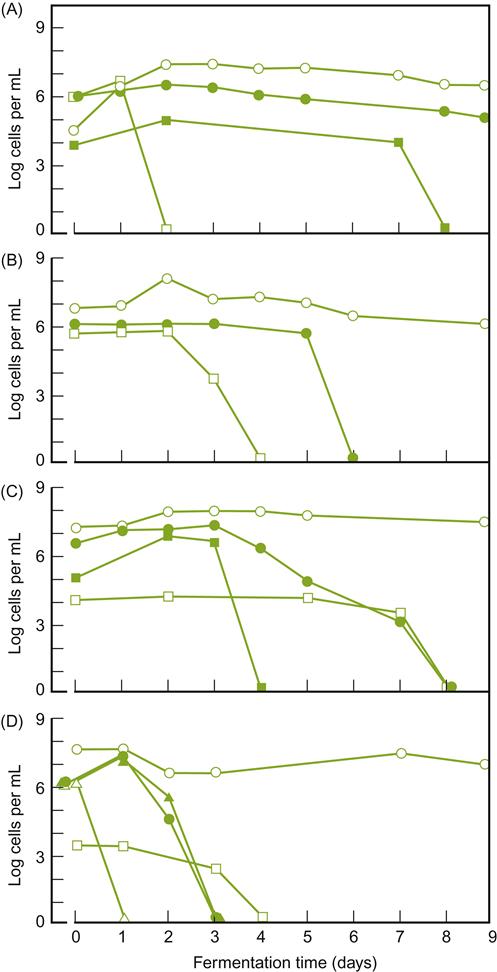

Even on healthy grapes, other yeasts may occur at concentrations approaching those typically used in inoculated fermentations (Fig. 7.27). Molecular evidence indicates that they may continue to persist in a viable, but unculturable state, throughout fermentation (Cocolin and Mills, 2003). At present, it is not established how commonly, or for how long, these species remain metabolically active (Millet and Lonvaud-Funel, 2000). Thus, their significance to vinification remains uncertain, and possibly underestimated. However, in some instances, they maintain or increase their numbers during fermentation (Mora and Mulet, 1991; Fig. 7.27). This appears to be more common when fermentation temperatures are low (Heard and Fleet, 1988), or yeast inoculation is delayed (Petering et al., 1993). Only in diseased or damaged grapes is the microbial grape flora clearly known to play an important role in vinification.

, Saccharomyces cerevisiae;

, Saccharomyces cerevisiae;  , Kloeckera apiculata;

, Kloeckera apiculata;  , Candida stellata; ■, C. pulcherrima;

, Candida stellata; ■, C. pulcherrima;  , C. colliculosa;

, C. colliculosa;  , Hansenula anomala. The initial population of S. cerevisiae comes predominantly from the inoculation conducted in the fermentations. (From Heard and Fleet, 1985, reproduced by permission.)

, Hansenula anomala. The initial population of S. cerevisiae comes predominantly from the inoculation conducted in the fermentations. (From Heard and Fleet, 1985, reproduced by permission.)In addition to the epiphytic yeast inoculum, juice and must may become inoculated from winery equipment (notably crushers, presses, and sumps) and the winery environment. This is especially true in old wineries, in which the equipment and buildings are thinly covered with wine yeasts. In addition, Hansenula anomala and Pichia membranaefaciens commonly occur in wineries, with Brettanomyces and Aureobasidium pullulans often being isolated from the walls of moist cellars. The hygienic operation of present-day wineries greatly limits juice and must inoculation, or contamination from the winery and its equipment. In such situations, the vineyard is presumably the main source of S. cerevisiae in spontaneous fermentations (Török et al., 1996).

Succession During Fermentation

In spontaneous fermentations, there is a rapid and early succession of yeast species. Initially, Kloeckera apiculata and Candida stellata may occur in the range of 103–106 cells/mL. This number increases rapidly if the grapes or must are left at warm temperatures. Although these endemic yeasts may grow at the beginning of fermentation, most strains soon pass into decline. The culturable population usually decreases, becoming a minor component of the yeast population. This has frequently been interpreted as a result of the increasing concentration of ethanol produced by Saccharomyces, and/or the addition of sulfur dioxide. Recent studies indicate that other interstrain and interspecies effects and influences may also play a role. Examples may involve the selective action of acetaldehyde (Cheraiti et al., 2005), and relative abilities to translocate glucose into the cell (Nissen et al., 2004).

During the initial stages of fermentation, the activities of non-Saccharomyces yeasts contribute to the production of compounds such as acetic acid, glycerol, and various esters (Ciani and Maccarelli, 1998; Romano et al., 2003). This can be sufficient to significantly influence the wine’s aroma (Eglinton et al., 2000; Soden et al., 2000). For example, some strains of Kloeckera apiculata can potentially produce up to 25 times the amounts of acetic acid typically produced by S. cerevisiae. K. apiculata, along with other members of the grape epiphytic flora, may also produce above-threshold amounts of 2-aminoacetophenone. This compound has been associated with the naphthalene-like odor characteristic of untypical aging (UTA) (Sponholz and Hühn, 1996). In addition, K. apiculata may inhibit some S. cerevisiae strains from completing fermentation (Velázquez et al., 1991), possibly due its production of acetic acid, octanoic and decanoic acids, or ‘killer’ factors. In addition, the indigenous grape flora may enhance amino acid availability by their proteolytic activities (Dizy and Bisson, 2000). At cool fermentation temperatures (10 °C), yeasts such as K. apiculata may remain active (or at least viable) throughout alcoholic fermentation (Heard and Fleet, 1988; Erten, 2002).

Occasionally, strains of Candida stellata persist in fermenting juice (Fleet et al., 1984). Their ability to produce high concentrations of glycerol could play a role in enhancing a wine’s smooth mouth-feel. Jolly et al. (2003) report that the perceived quality of Chenin blanc wine was increased when Candida pulcherrima was combined with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Torulaspora delbrucecki also has the potential to positively influence the sensory properties of wine, due to its low production of acetic acid and synthesis of succinic acid. Although Kloeckera apiculata and C. stellata typically ferment only up to approximately 4 and 10% alcohol, respectively, they are able to survive much higher alcohol concentrations (Gao and Fleet, 1988).

Of equal or possibly greater significance is the property of some Hanseniaspora, Debaryomyces, and Dekkera spp. to produce glycosidases (Villena et al., 2007). Their action in releasing terpenoids and other volatiles could positively affect the development of the varietal character of a wine. The role of their other enzymatic activities on flavor development is largely unknown, except for the negative influence of Dekkera spp. on the decarboxylation of hydroxycinnamic acids in generating 4-ethylphenol and 4-ethylguaiacol.

Nonetheless, most members of the grape flora are either slow growing or typically suppressed by the low pH, high initial osmolarity of the juice/must, augmenting ethanol content of the ferment, oxygen deficiency, or sulfur dioxide. Their relative inability to incorporate glucose under vinous conditions may also play a significant role in their early demise (Nissen et al., 2004). Consequently, most species of Candida, Pichia, Cryptococcus, and Rhodotorula probably do not contribute significantly to fermentation. Their populations seldom rise above 104 cells/mL, and the species usually disappear quickly from the ferment. However, if warm conditions prevail, and active fermentation is delayed, these yeasts may initiate severe spoilage. Under such conditions, Pichia guilliermondii has the potential to produce sufficient 4-ethylphenol to generate odors variously described as burnt beans, band-aid, wet dog, horse sweat, and barnyard (Barata et al., 2006).

Because of their potential to affect wine quality (Egli et al., 1998), there is increasing interest among winemakers in using endemic yeasts to give their wines distinctiveness (Fig. 7.28). Nevertheless, as with any technique, it needs to be used with discretion and tempered with experience. For example, cool fermentation without sulfur dioxide runs the risk that non-Saccharomyces yeast may dominate fermentation, generating sufficient acetic acid and fusel alcohols to mask grape varietal aromas. In addition, other yeasts can lead to stuck fermentation, especially under stressful vinifications (Ciani et al., 2006).

The few bacteria able to grow in juice or must are usually inhibited by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with the exception of lactic acid bacteria. Thus, S. cerevisiae (or occasionally other Saccharomyces spp.) find few if any organisms capable of competing with them in grape must. Not surprisingly, S. cerevisiae tends to dominate and complete fermentation, even when its initial presence in must is rare (less than 1/5000 colonies), as in many spontaneous fermentations (Holloway et al., 1990). Subsequently, however, other yeasts may multiply in association with lactic acid bacteria during or following malolactic fermentation, notably Pichia spp. (Fleet et al., 1984).

Several investigations indicate that local populations of S. cerevisiae are heterogeneous, consisting of many strains, differing considerably even among regional wineries (see Mortimer, 2000). Although their numbers are usually low, they may occasionally reach 104–105 cells/mL, possibly derived from winery equipment, or as residents on damaged grapes. There may also be shifts in their dominance from year to year (Polsinelli et al., 1996) and from site to site (Guillamón et al., 1996). Inoculated strains typically dominate fermentation, but other strains may remain active for several days before being suppressed (Querol et al., 1992). Thus, indigenous S. cerevisiae strains may play a significant sensory role even in induced fermentations. Shifts in population numbers may also occur throughout fermentation when must is inoculated with several strains (Schütz and Gafner, 1993a; Sipiczki et al., 2004). Because of the low incidence of sexual recombination, infrequent ascospore production, and poor ascospore viability, it is suspected that mitotic recombination and mutation are the primary sources of this variability (Puig et al., 2000). However, strain selection in an existing heterogenous population could be at work as well.

Must Inoculation

During inoculation, sufficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae is added to reach a population of about 105–106 cells/mL. With active dry yeasts, this is equivalent to about 0.1–0.2 g/liter of juice/must. Active dry yeast often contains about 20–30×109 cells/g. In its production, the culture is treated so that the cells possess adequate amounts of protein, ergosterol, unsaturated fatty acids, and reserve materials for several divisions. Principal among the latter is trehalose, important in providing resistance to both drying and rehydration.

Inoculation is particularly common in the production of white wine, due to its lower nutrient status and yeast population (short maceration followed by clarification), and cool fermentation temperature. The different processes involved in red wine production mean inoculation is less necessary (i.e., fermentation with the pomace, warmer fermentation temperatures, possibility of some aeration during pumping over). Nonetheless, inoculation still has significant benefits in assuring a clean, predictable fermentation. With stuck fermentations, inoculation is essential.

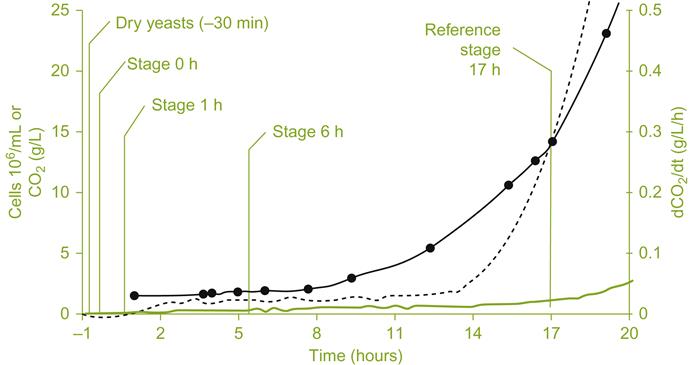

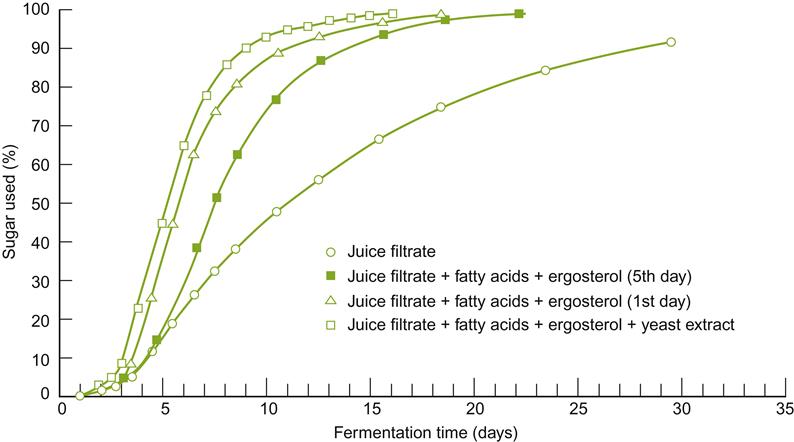

Before addition, the inoculum is placed in water or dilute juice. Rehydration is recommended to occur at about 37 °C for 20 min (details depending on the strain and supplier). Supplementation of the rehydration medium with small amounts of sterols (often in the form of yeast cell fragments) (Soubeyrand et al., 2005) increases both yeast viability and improves their fermentative ability. A short interval at 25 °C before inoculation also improves survival, during which damaged cytoplasmic and membrane structures (Beker and Rapoport, 1987) are repaired and metabolism adjusts itself to the new conditions. This is important before the cells are exposed to the full osmotic potential of grape must. Readaptation occurs progressively (Fig. 7.29) and is estimated to involve about 2000 genes (Rossignol et al., 2006). Inoculation of cool musts requires even longer and progressive adaptation. Fractional addition of further juice, before final incorporation of the inoculum into the must, avoids rapid temperature changes and promotes retention of high cell viability.

, cumulated CO2 released. (Reprinted from Rossignol et al., 2006, with kind permission of Springer Scientific and Business Media.)

, cumulated CO2 released. (Reprinted from Rossignol et al., 2006, with kind permission of Springer Scientific and Business Media.)Commercially available strains of S. cerevisiae possess a wide range of characteristics, suitable for almost any winemaking situations. These include those that enhance the release of varietal flavorants (glycosides and/or cysteinylated/glutathionylated complexes); secrete acid proteases (potentially valuable in achieving protein stability) (Younes et al., 2011); produce an abundance of fruit esters (especially valuable in fermenting neutral flavored cultivars); are of neutral character (allowing the varietal character to be highlighted); or possess high hydroxycinnamate decarboxylase activity (enhancing the formation of stable pyranoanthocyanin pigments). Strains are also available that are notable for their production of low levels of acetic acid, hydrogen sulfide, or urea. Others may be chosen because of their relative fermentation speed; their ability to synthesize or degrade malic or lactic acid; their ability to augment the concentration of glycerol; their ability to restart stuck fermentation; or their known value in producing particular wine styles, notably carbonic maceration, late-harvest, or early- versus late-maturing reds. In addition, there are locally selected strains that are reported to produce regionally distinctive wines.

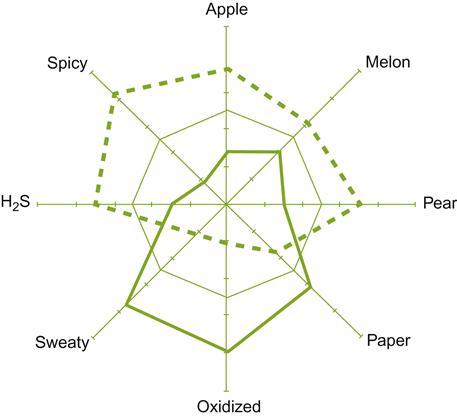

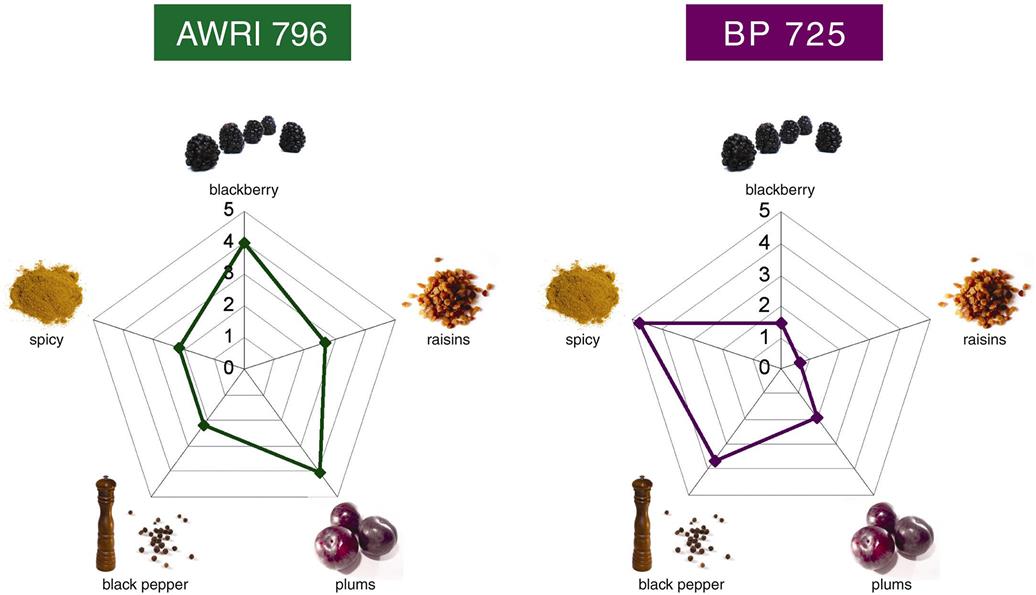

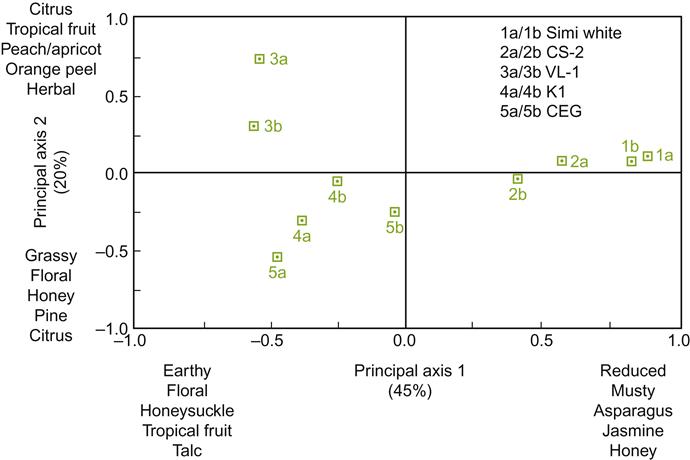

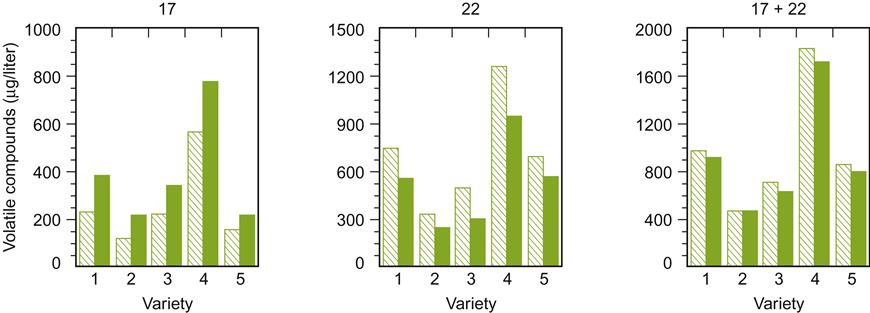

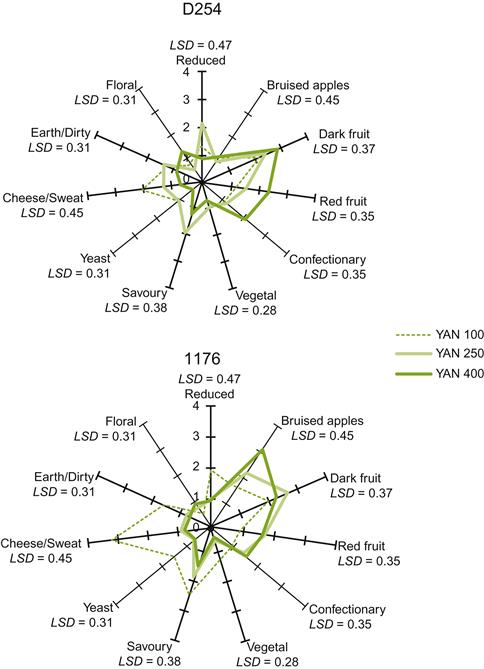

Despite all this information, or possibly because of it, the winemaker’s choice is far from simple. The main characteristics of most commercial strains are known, but most of their other properties are not, or if known they are buried in research papers not readily accessible to most winemakers. In addition, much information is anecdotal. Commercial suppliers provide data and suggestions on the various species and strains they provide, but cross comparison between suppliers is fraught with difficulty, combined with the knowledge that local conditions often are crucial to feature expression. Thus, regrettably, it is again up to the winemaker to do their own individual experimentation to determine what best suits their situations and preferences. Figures 7.30 and 7.31 give visual representations of the clear sensory differences between yeast strains.

In only a few instances is inoculation absolutely essential. With thermovinification or pasteurized juice, most of the endogenous yeast population is destroyed, requiring inoculation to achieve a rapid initiation of fermentation. In addition, inoculation is necessary to restart ‘stuck’ fermentations, and to promote fermentation of juice containing a significant number of moldy grapes. Moldy grapes generally possess various inhibitors, such as acetic acid, that slow yeast growth and metabolism. Finally, inoculation is required to assure the initiation of the second fermentation in sparkling wine production. However, the predominant reason for using a specific yeast strain or strains is to avoid the production of undesirable flavors that are occasionally associated with spontaneous fermentations.

Spontaneous vs. Induced Fermentation

There has been much discussion over the years concerning the relative merits of spontaneous versus induced fermentation. That various strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae supply distinctive sensory attributes is indisputable (Cavazza et al., 1989; Grando et al., 1993; Walsh et al., 2006). This is particularly important for aromatically neutral cultivars. Their use may also play an increasingly important role in restricting the higher alcohol potentials of late-harvested grapes – conducted on the belief that this enhances wine flavor (Donaldson, 2008). Yeast strains differ significantly in ethanol production under identical conditions. In addition, strain choice can equally affect the varietal character of aromatically distinctive cultivars, by influencing the liberation or synthesis of specific grape flavorants (Ugliano et al., 2006). These influences not only affect the sensory attributes of young wines, but can still be detected after at least 3 years (King et al., 2011). This may be even more significant with non-Saccharomyces yeasts. They appear to have greater activity in breaking glycosidic bonds (Mendes-Ferreira et al., 2001). These effects can be further modified or enhanced by sur lies maturation. Regrettably, our knowledge of the chemical origin of their sensory effects is insufficient to permit prediction of results. Nevertheless, using established strains provides the winemaker with the greatest confidence that fermentation will initiate rapidly, go to completion cleanly (diminishing the possibility of undesirable microbial activity, disruption from killer factors, or must oxidation), and possess relatively predictable flavor and quality attributes.

In contrast, spontaneous fermentations may accentuate yearly variations in character. Capitalizing on vintage uniqueness is part of the marketing strategy of many European regions, and often considered part of the appeal of terroir distinctiveness. Spontaneous fermentations are often believed to generate greater aromatic complexity. Whether this is beneficial or not depends on the perceiver. It is commonly viewed by wine writers and other wine professionals to be of significance to the consumer. Sadly, this is probably wishful thinking (justifying research), and may apply only to those influenced by the comments of wine critics. The vast majority of consumers seem oblivious or indifferent to such subtleties, with their purchasing habits little influenced by factors actually affecting the wine’s sensory attributes.

Although spontaneous fermentation can influence a wine’s sensory character (Hernández-Orte et al., 2008; Varela et al., 2009), its effects can be inconsistent and relatively unpredictable. It also has a greater risk of leading to the development of off-odors and other undesirable sensory properties. For example, the activity of Kloeckera and Hanseniaspora can increase the incidence of non-protein haze formation (Dizy and Bisson, 2000). Spontaneous fermentations associated with oxidative yeasts are also frequently associated with higher concentrations of volatile acidity and ethyl acetate (Salvadores et al., 1993). They also tend to possess noticeable lag periods (most likely due to the low S. cerevisiae inoculum) and thus are more susceptible to disruption by killer factors (see below), or suppression by other yeast species.

Those who favor spontaneous fermentation believe that the endemic grape flora supplies a desired subtle or regional character (Mateo et al., 1991), supposedly missing with induced fermentations. Large-scale wineries, where brand-name continuity is essential, must avoid such risks of inconsistency. Because even induced fermentations are not pure-culture fermentations, they already run enough hazards with the indigenous microbial flora. Juice and must always contain sizable populations of epiphytic yeasts and bacteria, unless pasteurized or treated to thermovinification. In either case, it is preferable to do yearly blind tasting with competitor wines to ascertain, in an objective manner, whether beliefs are supported by results. An outline of such techniques is provided in Chapter 11 and in greater detail in Jackson (2009).

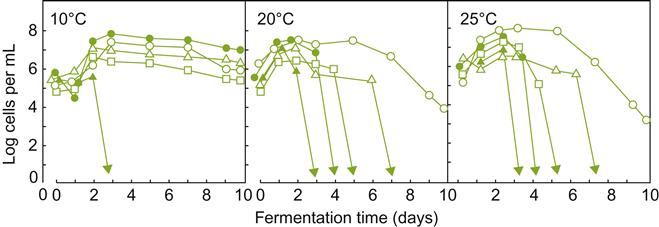

An alternative to either spontaneous or standard induced fermentation is inoculation with a mix of local and commercial yeast strains (Moreno et al., 1991). The combination appears to diminish individual differences, producing a more uniform and distinctive character. This may also involve the joint inoculation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with species such as Candida stellata (Soden et al., 2000), Debaryomyces vanriji (Garcia et al., 2002), or Pichia kluyveri (Anfang et al., 2009). In the latter instance, the liberation of the aromatically significant thiol, 3-mercaptohexyl acetate, from Sauvignon blanc was enhanced. The activity and survival of members of a mixture is highly dependent on a variety of factors, notably species and temperature (Fig. 7.32). Aeration of the must also favors prolonged activity of non-Saccharomyces yeasts (Hansen et al., 2001). Because joint inoculation may result in partial suppression of one or more strains or species, sequential inoculation of non-Saccharomyces species, followed by later inoculation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is an intriguing option (Languet et al., 2005; Raynal et al., 2011). This generates, under semi-controlled conditions, a sequence similar to spontaneous fermentation.

, Saccharomyces cerevisiae;

, Saccharomyces cerevisiae;  , Kloeckera apiculata;

, Kloeckera apiculata;  , Candida stellata;

, Candida stellata;  , Candida krusei;

, Candida krusei;  , Hansenula anomala. (From Fleet et al., 1989, reproduced by permission.)

, Hansenula anomala. (From Fleet et al., 1989, reproduced by permission.)As noted earlier, on-site experimentation is the only sure means of determining the value of any practice. The metabolic products released by any strain, species, or their combination depends largely on the specific fermentation conditions (Thorngate, 1998; Regodón Mateos et al., 2006).

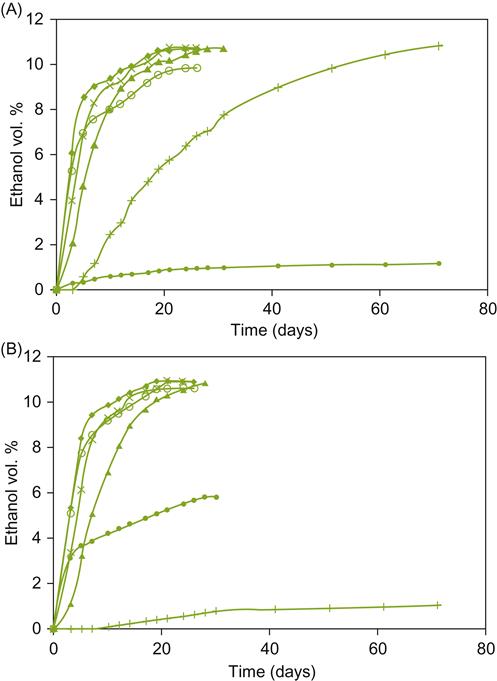

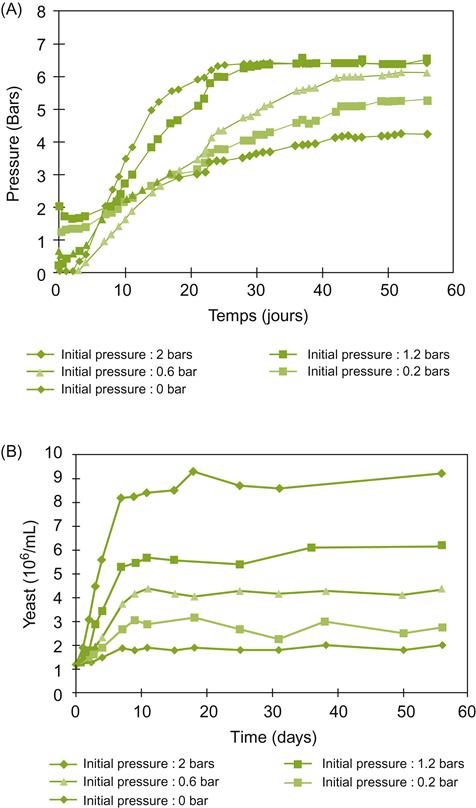

Another choice for winemakers searching to add a distinctive aspect to their wine is to use cryotolerant yeasts, notably S. bayanus var. uvarum. It is characterized not only by its ability to ferment at cold temperatures (Fig. 7.33), but also by its potential to direct the development of desirable sensory characteristics. For example, cryotolerant yeasts generally produce higher concentrations of glycerol, succinic acid, 2-phenethyl alcohol, and isoamyl and isobutyl alcohols; synthesize malic acid; and produce less acetic acid than many mesophilic S. cerevisiae strains (Castellari et al., 1994; Massoutier et al., 1998).

, 12 °C;×, 18 °C; ♦, 24 °C;

, 12 °C;×, 18 °C; ♦, 24 °C;  , 30 °C;

, 30 °C;  , 36 °C) for (A) cryotolerant and (B) non-cryotolerant strains. (From Castellari et al., 1995, reproduced by permission.)

, 36 °C) for (A) cryotolerant and (B) non-cryotolerant strains. (From Castellari et al., 1995, reproduced by permission.)Although different strains, species, and their combination can affect the sensory attributes of wines, until recently the question of whether these differences affected consumer preference had not been studied. Under the conditions of an experiment in a relatively recent study, the answer was affirmative (King et al., 2010). Whether consumer impression is sufficient to noticeably affect subsequent purchase and for how long are quite different questions for which there are currently no answers.

Yeast Breeding

Genetically, Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the best understood eucaryote, having been used for decades as a favorite laboratory organism. It is easily cultured and has a comparatively small genome (~13000 kb), possessing relatively little repetitive DNA and few introns. The complete genome of a laboratory strain was deciphered in 1997, indicating that it possessed about 5800 protein-coding genes, located on 16 chromosomes. Furthermore, its protenome (full set of proteins) may be defined in the near future. In addition, recent developments in DNA microarray technology may make it easier to understand the intricacies and interconnections of its metabolic pathways (see Cavalieri et al., 2000). These advances should permit a shift from the traditional cross-and-select approach to breeding to one based on the selective elimination, modification, or introduction of specific genes.

Although S. cerevisiae is admirably suited to its role as the predominant fermenter of grape must, and there exists a wide diversity of strains possessing distinctive and useful properties, improved expression or new properties would be useful. Such modifications can vary from subtle variations in aromatic synthesis (Fig. 7.34) to the incorporation of properties such as malolactic fermentation.

Genetic Modification

In contrast to industrial fermentations, winemaking has made little use of genetically engineered microbes (Cebollero et al., 2007). This is partially explained by the complex chemical origin of wine quality, which makes delineating specific improvements difficult. In addition, other factors such as grape variety, fruit maturity, and fermentation temperature are generally, but not necessarily, considered to be of greater importance. In addition, more is known about the negative influences of certain yeast properties than about their positive sensory attributes. Finally, public suspicion of genetic engineering is regrettably, but undoubtedly, a prime reason for its minimal use.

In genetic improvement, features controlled by one or a few genes are the most easily influenced. For example, inactivating the gene that encodes sulfite reductase limits the conversion of sulfite to H2S. Improvement in other attributes, such as flocculation, has been more difficult. Flocculation is regulated by several genes, epistatic (modifier) genes, and possibly cytoplasmic genetic factors (Teunissen and Steensma, 1995). The major locus encodes for cell-surface proteins, notably lectins and lectin receptors. These are not constitutively present on the cell surface, but appear later in colony growth. This may result from the proteins being selectively deposited where budding has occurred, and at the tips of buds (Bony et al., 1998). In addition, the flocculation mechanism employed by different yeast strains can differ, as is the case with top- versus bottom-fermenting brewing yeasts (Dengis and Rouxhet, 1997).

Most important enologic properties are likely to be under multigenic control (Marullo et al., 2004). Alcohol tolerance and the ability to ferment steadily and cleanly at low temperatures are undoubtedly multigenic; most individual genes possessing only slight or synergistic effects. Genetic improvement is possible, but probably will take considerable effort and time to achieve. Chances of improvement are significantly enhanced if the biochemical basis of such factors is understood. This knowledge could pinpoint the genes most likely worth modifying.

Even more convoluted problems arise from our inability to predict the consequences of changing the direction of metabolic pathways (Prior et al., 2000). Modifying the regulation of one pathway can have important and unforeseen consequences on another (Guerzoni et al., 1985; de Barros Lopes et al., 2003). Unanticipated metabolic disruptions are less likely when the compound concerned is the end by-product of a metabolic pathway. Thus, terpene synthesis has been incorporated, by transfer of farnesyl diphosphate synthetase from a laboratory strain into a wine strain, without apparent undesirable side-effects (Javelot et al., 1991). Use of the modified yeast gives the wine a Muscat-like attribute.

Many techniques are available to the researcher interested in improving wine yeasts. The most direct approach involves simple selection, and often is initially effective. This method is much facilitated if a selective culture medium can be devised to permit only cells containing the desired trait to multiply. Otherwise, cells must be laboriously isolated and individually studied for the presence of the desired trait.

Alternatively, adaptive evolution has had a long and successful history in developing industrial microbes. Surprisingly, it has been little employed in wine yeast breeding. Its applicability has, however, been illustrated by McBryde et al. (2006). It avoids problems associated with the reticence of many winemakers and consumers to accept wine produced using generically engineered strains. However, for certain changes, more direct measures of modifying the genetic makeup are required. This can involve procedures such as hybridization, backcrossing, and mutagenesis, or newer techniques such as somatic fusion and genetic engineering.

Interspecific hybridization has apparently occurred naturally in the past within Saccharomyces sensu stricto species (de Barros Lopes et al., 2002), as well as currently (Cubillos et al., 2009). This may be facilitated by passage of the spores through the gut of Drosophila, a known vector of S. cerevisiae (Reuter et al., 2007). Nonetheless, wine yeast breeding has proven difficult. One of the principal complications results from the early (intra-ascal) fusion of spores of opposite mating-type. This precludes designed mating between haploid cells of different strains. Further complicating matters is the tendency of haploid cells to switch mating type shortly after ascospore germination, followed by nuclear fusion to form diploid cells. This eliminates any possibility of their designed mating.

Problems with crossing can occasionally be avoided by tetrad analysis – the early physical isolation and separation of ascospores. Physically placing spores from desired strains next to one another often results in fusion and successful crossing. Designed mating can be made easier if the strains crossed are first made heterothallic (Bakalinsky and Snow, 1990b). Most wine strains are homothallic (self-fertile), with haploid nuclei fusing within the ascus or shortly thereafter, obviating the possibility of designed crosses. Introduction of a recessive allele of the HO gene prevents switching of the mating-type gene, and correspondingly increases the probability of successful designed crosses. An alternate technique has been described by Ramírez et al. (1998). Regrettably, techniques that work successfully with well-characterized, haploid, laboratory strains do not necessarily work equivalently with industrial strains, such as wine yeasts.

Breeding wine strains is also exacerbated by the low frequency of sexual reproduction and spore germination (Bakalinsky and Snow, 1990a). Many strains undergo meiosis infrequently, a clear precondition for sexual reproduction. Of the haploid spores produced, infertility is frequent, probably due to the high incidence of aneuploidy (unequal numbers of similar chromosomes) (Bakalinsky and Snow, 1990a). Wine strains may also show chromosomal polymorphism, associated with rearrangement. It has been suggested that aneuploidy and other chromosomal abnormalities, due to their frequent occurrence, may possess unsuspected selective value under winemaking conditions.

Even in successful matings, the typical diploid state of wine yeasts can mask the presence of potentially desirable recessive alleles. In haploid organisms, the phenotype of recessive genes is expressed – no corresponding dominant (usually functional) allele being present. Although a complication in crossing experiments, diploidy permits ‘genome renewal’ by permitting the selective elimination of growth-retarding alleles. These slowly accumulate due to mutation (Ramírez et al., 1999).

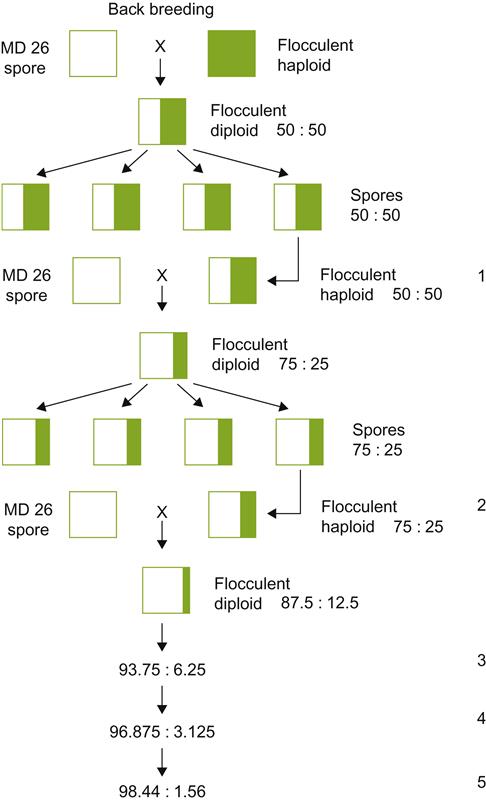

If only a single genetic trait needs to be incorporated into an existing strain, backcross breeding is the preferred method. Figure 7.35 illustrates a situation in which a dominant flocculant gene is transferred from a donor strain to a valuable nonflocculant strain. Hybridized cells, containing the flocculant gene, are repeatedly backcrossed to the recipient strain. Combined with strong selection for flocculation, backcrossing rapidly eliminates undesired donor genes, unintentionally incorporated in the original cross.

Where the genetic nature of the desired trait is unknown, or is under complex genetic control, crossing potentially suitable strains requires growing out tens of thousands of progeny. These must be individually assessed for their respective characteristics. Because this is so arduous, time-consuming, and expensive, breeders try to incorporate selective techniques that permit only the growth of desirable progeny.

In situations where standard procedures are not applicable (existing strains do not or are not known to possess the desired trait), ‘unconventional’ techniques must be sought. For example, somatic fusion may permit the incorporation of traits from yeast species with which traditional mating is impossible. Somatic fusion requires enzymatic, cell-wall dissolution, and subsequent mixing of the protoplasts. This usually occurs in the presence of polyethylene glycol, or some other agent that facilitates protoplast fusion. Fusion permits the possibility of gene exchange by combining the genes of both species in a single cytoplasm.

A serious limitation and disadvantage with somatic fusion is the frequent instability of the association. Fused cells often revert to one of the original species. The incorporation of foreign genes can also interfere with expression of existing traits.

Less disruptive is the incorporation of one or only a few genes from a donor organism. The procedure is called transformation, or more popularly, genetic engineering. It has the distinct advantage that the donor and recipient need not be closely related, as they need to be for crossing or somatic fusion to work. In transformation, yeast protoplasts may be bathed in a solution containing DNA from the donor organism. The DNA segments also require appropriate initiator and termination sequences for proper function when incorporated. Upon uptake, the gene needs to be transported into the nucleus and inserted into a chromosome. Without this, it is potentially unstable and may be lost in subsequent generations. Alternatively, the gene may be spliced into a plasmid before uptake. Plasmids are circular, cytoplasmic DNA segments that partially control their own replication. Thus, even without chromosomal insertion, the gene may be replicated, along with the plasmid in the cytoplasm. Although most eucaryotic cells do not possess plasmids, wine yeasts frequently carry copies of a 2-μm plasmid. Despite their presence, the plasmid is nonessential to the host cell.

Using transformation, the malolactic gene from Lactococcus lactis has been transferred to S. cerevisiae, along with the malate permease transport gene from Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Bony et al., 1997). The possession of several copies of the malolactic enzyme facilitates the almost complete conversion of malic acid to lactic acid within 4 days. Recently, a commercial strain (ML01) of this type has been released, based on a construct of genes from S. pombe and Oenococcus oeni (Husnik et al., 2007). The strain conducts simultaneous alcoholic and malolactic fermentations. This permits rapid deacidification, without the development of the buttery and other flavors usually associated with bacterial malolactic fermentation. Wine stabilization procedures can commence immediately after alcoholic fermentation, without waiting (sometimes for months) for bacterial malolactic fermentation to come to completion.

Other genes of enologic interest that have been incorporated into yeasts are β-(1,4)-endoglucanase (to increase flavor by hydrolyzing glucosidically bound aromatics) and alcohol acetyltransferase (to increase fruity flavors). Both features might benefit wines produced from aromatically neutral varieties. Yeasts have also been transformed with polysaccarase genes so that they can degrade glucans and xylans (Louw et al., 2006). They can increase the proportion of free-run wine and enhance the color intensity and stability of red wines.

Other examples involve combining the flocculation gene (FLO1) with a late-fermentation promotor (HSP30). Exposing the yeast to heat-shock can induce flocculation ‘on demand.’ In another case, a homozygous strain, recessive for one of the aldehyde dehydrogenase genes (ALD6), was transformed with a high-copy 2-μm plasmid, containing the glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GPD2). This diverted more sugar to glycerol production, without an overproduction of acetic acid (Eglinton et al., 2002). This has the potential benefits of reducing ethanol production (producing more balanced wines from fully mature grapes) and increasing the fermentation rate (by enhancing osmotolerance) (Remize et al., 1999), as well as enhancing the smooth mouth-feel of the wine.

However, with characteristics based on many unlinked genes, it is a moot point whether genetic engineering has any selective advantage. In addition, genetic engineering is still complex and expensive. Part of this involves the long and complicated set of tests required before getting approval from the US Food and Drug Administration, or equivalent regulatory agencies. There is also considerable controversy about the safety of releasing genetically modified organisms into the environment. Although caution is always prudent, imprudent caution impedes progress. When reflecting on the incredible modification that has occurred historically during crop domestication (Zohary and Hopf, 2000), notably with corn (Mangelsdorf, 1974), the modifications involved in genetic engineering seem almost infinitesimal.

A requirement for all useful strains, no matter how they are derived, is genetic stability. Although a property of most traits, genetic stability is not a universal characteristic (Ambrona et al., 2005). For instance, flocculant strains often lose their ability to form large clumps of cells, settling out as a powdery sediment. Genetic instability may arise due to aneuploidy, mutation, or epigenetic modification. The latter is a previously unsuspected but major factor in gene regulation. Being often influenced by environmental conditions or transposon movement, prediction seems impossible.

A final caveat relates to the difference between conditions in the laboratory and micro-vinification, and commercial production conditions. Not only do vinification procedures vary from winery to winery, but the indigenous yeasts and bacterial flora of the grapes can significantly influence the attributes expressed by an inoculated strain. These differences frequently modulate the characteristics of the added strain, to such a degree that its intended effects may be largely negated or unpredictably qualified. Occasionally, indigenous yeasts displace inoculated strains. As always, experience under actual winery conditions for several years is essential to have relative confidence in the actual value of ‘new and improved’ strains.

Environmental Factors Affecting Fermentation

Carbon and Energy Sources

The major carbon and energy sources for fermentation are glucose and fructose. Other nutrients may be used, but they are present either in small amounts (amino acids), are poorly incorporated into the cell (glycerol), or can be utilized (respired) only in the presence of oxygen (acetic acid and ethanol). Sucrose can be fermented, but it is seldom present in significant amounts in grapes. It may be added, however, during processes such as chaptalization and amelioration, or as a nutrient for the second fermentation in the production of sparkling wine. For its metabolism, sucrose must be enzymatically split into its component monosaccharides, glucose and fructose. This occurs under the action of one of several invertases. Hydrolysis usually occurs external to the cell membrane by an invertase located between the cell wall and plasma membrane (periplasm). Most other sugars cannot be fermented by Saccharomyces cerevisiae as they lack the requisite enzymes and/or transport proteins. Significantly, though, other grape sugars can be utilized as an energy source by several spoilage microorganisms.

A variety of transport mechanisms moves glucose across the plasma membrane (Kruckeberg, 1996). Saccharomyces cerevisiae shows an extraordinary duplication and diversification of its HXT (hexose transport) gene family. Each of the approximately 18 variants possesses distinct regulatory and transport-kinetic properties. Some are low-affinity systems that typically work at high substrate concentrations. For example, the Hxt1 carrier is expressed only at the beginning of fermentation (Perez et al., 2005), Hxt2 (an intermediate carrier) is active only during the lag phase, whereas Hxt3 is functional throughout fermentation (but maximally at the onset of the stationary phase). Low-affinity systems appear to function by facilitated diffusion (without direct expenditure of metabolic energy). Thus, they are most effective at high sugar concentrations. In contrast, high-affinity systems are energy-requiring, and are particularly valuable at low glucose concentrations. They tend to be activated by a membrane protein, Snf3p, when sugar levels fall. Despite this, the major high-affinity systems of wine yeasts (Hxt6 and Hxt7) become active when the yeast colony enters the stationary phase – when considerable amounts of sugars still remain in the must. Although these transport proteins are named because of their transport capabilities, deletion mutants suggest that they have additional, regulatory roles that are not fully understood.

Glucose concentration not only differentially affects the activation of sugar transport mechanisms, but also regulates expression of enzymes in the TCA and glyoxylate pathways. Nevertheless, continued expression of selected chromosomal (vs. mitochondrial) genes results in some TCA enzymes being found in the cytoplasm even at high sugar concentrations. They are required for biosynthetic reactions essential for growth.

At maturity, the sugar concentration of most wine grapes ranges between 20 and 25%. At this concentration, the osmotic influence of sugar can delay the onset of fermentation. The resulting partial plasmolysis of yeast cells may be one of the causes of any lag period before active fermentation (Nishino et al., 1985). In addition, cell viability may be reduced; cell division retarded; and sensitivity to alcohol toxicity enhanced. At sugar concentrations above 25–30%, the likelihood of fermentation terminating prematurely increases considerably. Strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae differ greatly in their sensitivity to sugar concentration.

The nature of the remarkable tolerance of wine yeasts to the plasmolytic action of sugar is unclear, but appears to be related to increased synthesis, or reduced permeability, of the cell membrane to glycerol (see Brewster et al., 1993). These responses to increased environmental osmolarity permit glycerol to equilibrate the osmotic potential of the cytoplasm to that of the surrounding medium. The accumulation of trehalose may also be involved.

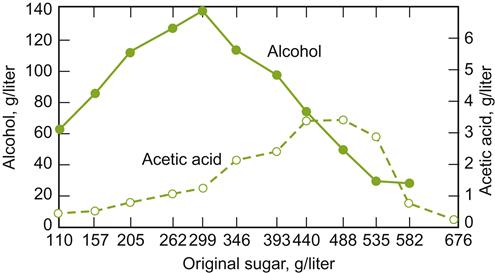

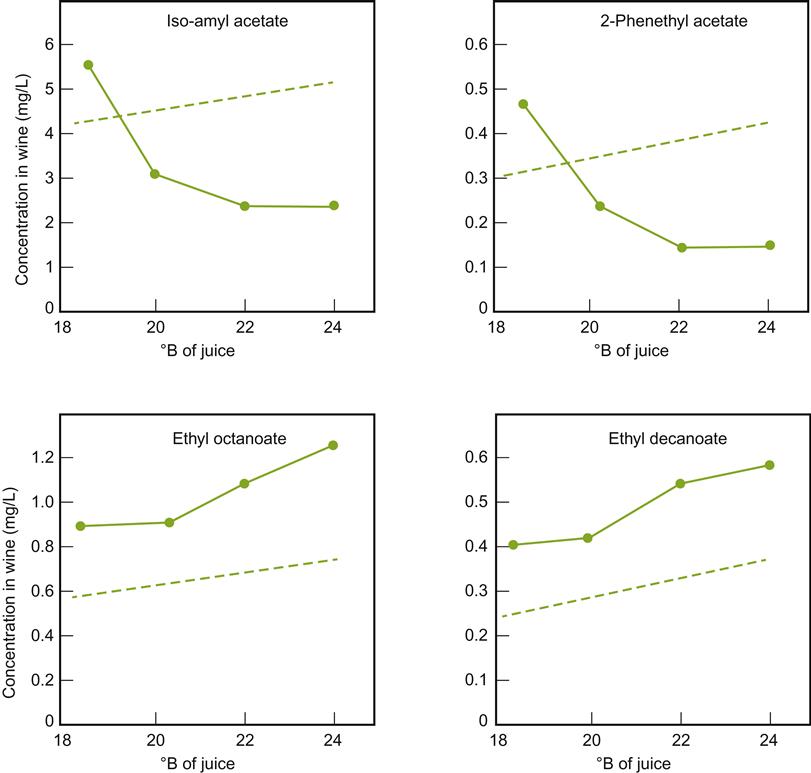

Sugar content affects the synthesis of several important aromatic compounds. High sugar concentrations increase the production of acetic acid (Fig. 7.36) and its esters. However, as indicated in Fig. 7.37, the effect of total soluble solids on esterification is not solely due to sugar content. For example, the synthesis of isoamyl acetate and 2-phenethyl acetate during fermentation decreases with increasing maturity (associated with a decreased synthesis of their corresponding fatty acids), but increases in juice from immature grapes, augmented with sugar to achieve the same °Brix. The importance of precursors in the must have been directly confirmed by Dennis et al. (2012). They found that the concentrations of C6 alcohols and aldehydes directly influence the synthesis of acetates such as benzyl, hexyl, and octyl acetates during fermentation.

Over a wide range of sugar concentrations, ethanol production is directly related to sugar content. However, above 30%, ethanol production per gram sugar begins to decline (Fig. 7.36).

Alcohols

All alcohols are toxic to varying degrees. Because Saccharomyces cerevisiae shows considerable insensitivity to ethanol toxicity, much effort has been spent attempting to understand the nature of this tolerance, and why it breaks down at high concentrations. Several factors appear to be associated with ethanol tolerance. These include activation of glycerol and trehalose synthesis (Hallsworth, 1998; Lucero et al., 2000); accumulation of Hsp104 (a general stress-related protein) and Hsp12 (Sales et al., 2000); and modification of the plasma membrane, such as activating membrane ATPase, substitution of ergosterol for lanosterol, increasing the portion of phosphatidyl inositol vs. phosphatidyl choline, and augmenting the incorporation of palmitic acid (Aguilera et al., 2006). These membrane changes decrease permeability (Mizoguchi and Hara, 1998), minimizing the loss of nutrients and cofactors from the cell, notably magnesium and calcium. That these factors may disrupt cellular redox potential is suggested by the growth stimulation provided by acetaldehyde (increasing the availability of NAD+) (Vriesekoop et al., 2007). Vacuolar membrane function is also crucial for the retention of toxic substances stored in vacuoles (Kitamoto, 1989). In addition to disrupting membrane function, ethanol can inactivate some enzymes by inducing structural modifications.

Although alcohol buildup eventually inhibits fermentation, it begins disrupting yeast metabolism at much lower concentrations. For example, suppression of sugar uptake can begin at about 2% ethanol (Dittrich, 1977). This property is partially dependent on the fermentation temperature, and is reflected in yeast growth potential (Casey and Ingledew, 1986), possibly through it effect on membrane fluidity. Disruption of ammonium transport and inhibition of general amino acid permeases also occurs as alcohol content increases. These influences can be partially offset by enrichment with unsaturated fatty acids (e.g., adding yeast hulls). Although higher (fusel) alcohols are more inhibitory than ethanol, their much lower concentration substantially limits their toxic influence.

Although most strains of S. cerevisiae can ferment up to 13–15% ethanol, there is wide variation in this ability. Cessation of growth routinely occurs at concentrations below those that inhibit fermentation. It is generally believed that this results from disruption of the semifluid nature of the cell membrane, thus lowering water activity (Hallsworth, 1998). This destroys the ability of the cell to control cytoplasmic function, leading to nutrient loss and disruption of the electrochemical gradient across the membrane. The latter is vital for nutrient transport (see Cartwright et al., 1989). Lowered water activity also disrupts hydrogen bonding, essential to enzyme function. High sugar contents enhance ethanol toxicity.

Ethanol is occasionally added to fermenting must or wine, usually in the form of distilled wine spirits (unmatured brandy), to arrest or prevent yeast and other microbial activity. This property is used selectively in sherry, port, and madeira production. In port, the brandy is added early during fermentation to retain about half the sugar content of the must. This leaves the wine with the aromatic attributes typical of early fermentation. For example, young port is likely to be higher in acetic acid, acetaldehyde, and acetoin content, but lower in glycerol, fixed acids, and higher alcohols (see Figs. 7.21 and 7.22) than had it fermented to dryness. In sherry production, wine spirits are added at the end of fermentation to inhibit the growth of acetic acid bacteria (>15% ethanol) and flor yeasts (>18% ethanol) during solera aging.

The accumulation of alcohol during fermentation has an important dissolving action on phenolic compounds. This effect is most pronounced at the beginning of fermentation. Given sufficient maceration time, though, phenolic compounds dissolve in water (Hernández-Jiménez et al., 2012). Most of the distinctive taste of red wines depends on the facilitated extraction of flavanols by ethanol during fermentation. Ethanol aids but is less critical to the extraction of anthocyanins. Phenolic extraction can be further enhanced in the presence of sulfur dioxide (Oszmianski et al., 1988).

Nitrogenous Compounds

Next to sugars, nitrogenous compounds are quantitatively the most important yeast nutrients. Under most circumstances, juice and must contain sufficient nitrogen for fermentation. Nitrogen contents can, however, vary considerably – values reported for juice in California can range from 60 to 2400 mg/liter. In addition, some cultivars have a tendency to experience nitrogen deficiency more frequently than others, for example, Chardonnay and Colombard. This is especially true when the juice has been given undue prefermentative centrifugation or filtration.

Nitrogen is required not only for the synthesis of structural, transport, and enzymatic proteins (essential for growth and metabolism), but is also an essential constituent in information molecules (nucleic acids) and in electron transport compounds. The importance of the ready availability of nitrogen for synthesis is illustrated by the rapid turnover in sugar transport proteins. These essential molecules have a half-life of about 6 h. Production of reduced sulfur odors can also commence within 30 min of the onset of nitrogen starvation.

Most of the nitrogen in grape must is in the form of free amino acids, notably proline and arginine. The proline content can be disregarded as it is poorly incorporated under anaerobic conditions. Thus, most of the assimilable nitrogen available to yeasts (YAN) consists of arginine, in addition to any ammonium ions present. Because arginine is largely localized in the skins, the duration of maceration and the method of pressing (with or without prior crushing) can significantly influence its extraction. With vineyard fertilization, the content of other available amino acids, notably glutamine, is increased.

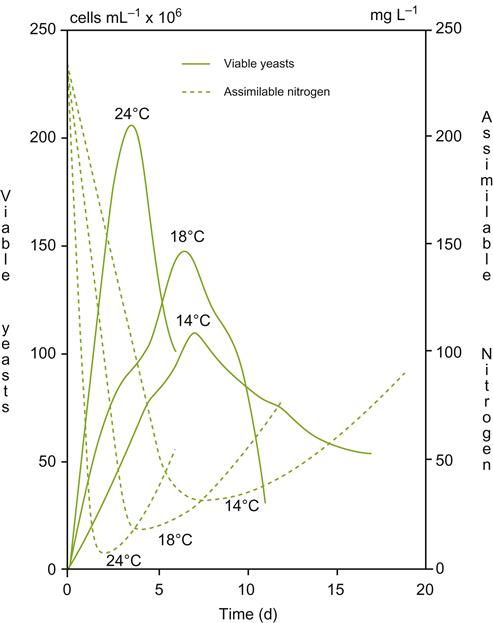

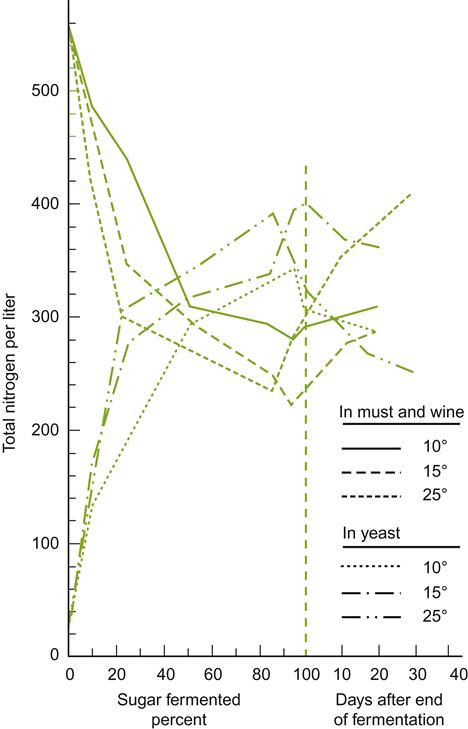

Uptake is highly correlated with the dynamics of yeast growth (Fig. 7.38), being initially stored before use. Optimum levels suggested by Henschke and Jiranek (1993) are in the range of 400–500 mg/liter, specific values depending on the demands of the yeast species and strain, as well as fermentation conditions, such as temperature and must sugar content. Significantly higher concentrations can be a disadvantage. They promote unnecessary cell multiplication and, correspondingly, reduce the conversion of sugar to alcohol. In contrast, low values or amino acid imbalance can enhance the release of higher alcohols; the accumulation of reduced sulfur off-odors; and an increased likelihood of sluggish or stuck fermentation.

When nitrogen is required, it is usually supplied as DAP. Ammonia is the least energy-demanding form of nitrogen available to yeasts. Amino acid uptake is associated with simultaneous hydrogen uptake. This eventually requires the expenditure of ATP for the expulsion of H+, to avoid lowering the pH of the cytoplasm. As ethanol content rises, its disruption of the cell membrane results in the spontaneous diffusion of H+ into the cytoplasm, and uptake of amino acids declines or ceases.

If added, DAP is usually supplied halfway through fermentation, near the onset of the stationary phase (Bely et al., 1990). As such, it does not interfere with the early synthesis of sugar transport proteins (Bely et al., 1994). Earlier addition also reduces yeast uptake of amino acids early during fermentation, when alcohol accumulation is still low. This has the potential to influence flavor development, due to the involvement of amino acids in higher alcohol and, thereby, ester formation and other sensory attributes (Fig. 7.39). Late addition is ill-advised as residual amounts can favor microbial spoilage.

In situations where nitrogen deficiency is severe, significant amounts of hydrogen sulfide are released as a consequence of restricted amino acid synthesis and degradation. This is most marked if nitrogen becomes limiting during the exponential phase. It is countered by the availability of ammonia (or most amino acids, with the notable exception of cysteine and proline). The breakdown of cysteine has the potential to increase the release of H2S and mercaptans. Under such conditions, earlier addition of DAP is advisable (Jiranek et al., 1995). Avoiding nitrogen deficiency also minimizes arginine degradation, and the subsequent release of urea. This in turn reduces the likelihood of ethyl carbamate generation, especially in wine exposed to heating. Ethyl carbamate is a suspected carcinogen.