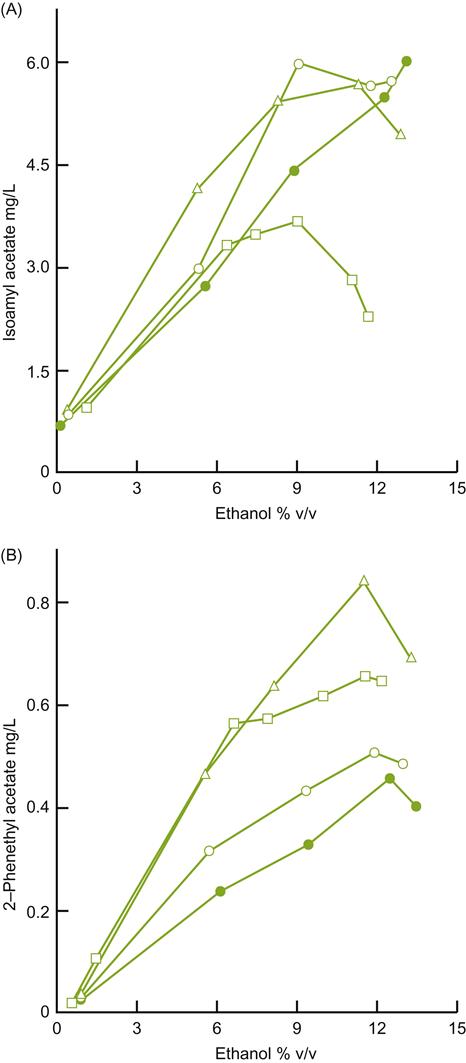

, 10 °C;

, 10 °C;  , 15 °C;

, 15 °C;  , 20 °C and

, 20 °C and  , 30 °C. (From Killian and Ough, 1979, reproduced by permission.)

, 30 °C. (From Killian and Ough, 1979, reproduced by permission.)Some of the effects noted above may result from the influence of temperature on the indigenous yeast flora. Cooler temperatures reduce both the growth rate and toxicity of ethanol (Heard and Fleet, 1988). As a result, species such as K. apiculata can remain active for a longer period during the extended fermentation period. For example, the indigenous flora appears to contribute significantly to the highly desired fruity–flora character of Riesling wines (Henick-Kling et al., 1998). Such findings have encouraged the use of cool fermentation temperatures and reduced sulfur dioxide addition.

The shift to cooler fermentation temperatures has increased interest in the use of Saccharomyces bayanus var. uvarum. Besides cryotolerance, these strains possess several additional desirable features. For musts low in total acidity, S. uvarum strains typically increase the malic acid content. Thus, a flat taste can be avoided by biological acidification. S. uvarum may also augment the glycerol content; enhance the content of several aromatic esters and succinic acid; and generate a lower alcohol content (Massoutier et al., 1998).

Red wines are typically fermented at higher temperatures than white wines. Temperatures between 24 and 27 °C are generally considered standard. Such temperatures favor not only anthocyanin but also tannin extraction. However, such temperatures are not universally preferred. For example, wines made from Pinotage are reportedly better when fermented at 15 °C (du Plessis, 1983). The warmer temperatures generally preferred for red wine production probably relates more to its effect on phenol extraction than on fermentation rate. Temperature and alcohol are the major factors influencing pigment and tannin extraction from seeds and skins. Both groups of compounds dominate the characteristics of young red wines. The potentially undesirable consequences of higher fermentation temperatures, such as the production of increased amounts of acetic acid, acetaldehyde, and acetoin, and lower concentrations of some esters, are probably less noticeable against the more intense fragrance of red wines. The greater synthesis of glycerol at higher temperatures is often thought, possibly incorrectly, to give red wines a smoother mouth-feel.

Other important influences arise from factors not directly related to the effect of temperature on fermentation. For example, temperature affects the rate of ethanol loss during vinification (Williams and Boulton, 1983). The volatilization of hydrophobic, low-molecular-weight compounds such as esters is even more marked. Consequently, their dissipation has a greater potential impact on the sensory quality of wine than the loss of ethanol.

During fermentation, much of the chemical energy stored in grape sugars escapes as heat. It is estimated that this is equivalent to about 23.5 kcal/mol glucose (see Williams, 1982), resulting in a potential rise in temperature of 1.3 °C per 100 g sugar. This is sufficient for juice, with a reading of 23°Brix, to potentially increase in temperature by about 30 °C during fermentation. If this were to occur, yeast cells would die before completing fermentation. In practice, such temperature increases are not realized. Because heat is liberated over several days to weeks, some of the heat dissipates with escaping carbon dioxide and water vapor. Heat also radiates through the surfaces of the fermentor into the cellar environment. Nevertheless, the rise in temperature can easily be in the range of 12–15 °C, sufficient to be critical to yeast survival, if temperature-control measures are not implemented. Temperature control is also essential if the fermentation temperature is intended to remain within a narrow range.

Critical to the importance in any heat buildup is the initial temperature of the juice or must. This influences the rate of fermentation and, correspondingly, the rate at which temperature rises. Up to a point, the greater the initial rate of fermentation, the sooner a lethal temperature may be reached. Thus, cool temperatures at the beginning of fermentation can diminish the degree and sophistication of any temperature control required.

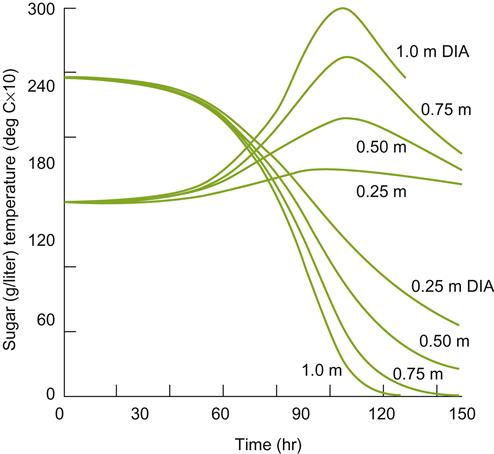

Also important to temperature control is the size and shape of the fermentor, and the presence or absence of a cap. The rate of heat lost is often directly related to the surface area/volume ratio of the fermentor. By retaining heat, the volume of juice can significantly affect the rate of fermentation – the larger the fermentor, the greater the heat retention and likelihood of overheating. This feature is illustrated in Fig. 7.45.

Another issue is the development and maintenance of a relatively uniform temperature throughout the fermentor. The turbulence induced by the tumultuous release of carbon dioxide during fermentation may be sufficient to achieve uniformity. This is often the case in producing white and rosé wines, in which vertical and lateral temperature variation is little more than 1 °C. At cool fermentation temperatures, however, turbulence may be insufficient to equilibrate the temperature throughout the fermentor and temperature stratification may develop.

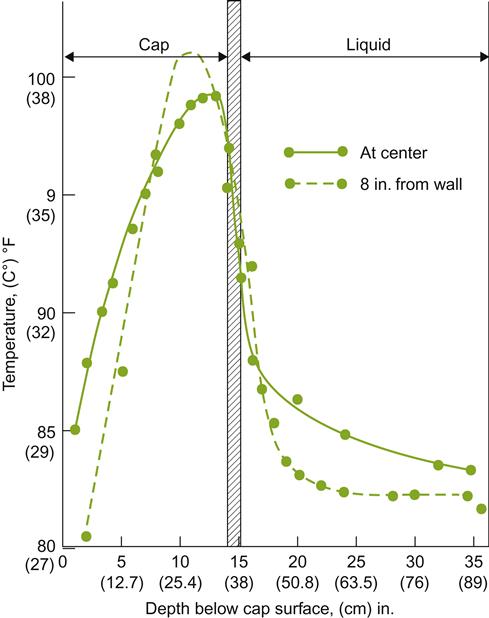

With red wines, cap formation disrupts the effective circulation and mixing of the must. The cap-to-liquid temperature difference may reach 10 °C (Fig. 7.46). Without mixing, the temperature differential may reach its maximum within 3 days, declining progressively thereafter to about 3.5 °C after 6 days (Vannobel, 1986). More recent and extensive data on temperature variations throughout the fermentor volume are presented by Schmid et al., 2009 (Fig. 7.47). Periodic punching down produces only transitory temperature equilibration between the cap and the juice; full pumping over is required to reduce temperature differences to less than 5 °C. In contrast, little temperature variation exists within the main volume of the must. Because high cap temperatures are a common feature of many traditional red wine fermentations, these vinifications may consist of two simultaneous but distinct phases – a liquid phase, in which the temperature is cooler and changes less during fermentation, and a largely uncontrolled high-temperature phase in the cap (Vannobel, 1986). Because the rate of fermentation is more rapid in the cap, the alcohol content rises quickly to above 10%. The higher temperatures found in the cap, plus the association of alcohol, probably increase the speed and efficiency of phenol extraction from the seeds and skins trapped in the cap. This feature is presumably absent or much diminished where the cap is submerged, or where automatic punching down, pumping over, or rotary fermentors are used to diminish the temperature and associated differences between the cap and main must volume. There appears to have been little investigation of the sensory consequences of current cap submerging techniques, and former procedures, where incomplete and intermittent cap disruption resulted in fermentation occurring at different temperatures within the cap and juice, respectively.

Temperature regulation is achieved by a variety of techniques. Selective harvest timing has the potential to provide fruit at a desired temperature, obviating at least the need for juice or must cooling. For centuries, relatively small fermentors and vinification in cool cellars have have been used to achieve a degree of natural temperature control. Pumping over in red wine vinification is another procedure that provides a degree of cooling, in addition to its main role in submerging the cap. However, the maintenance of fermentation temperatures within a select, narrow range requires direct cooling in all but small barrels in cool cellars.

If heat transfer through the fermentor wall is sufficiently rapid, cooling the fermentor surface with water or by passing a coolant through an insulating jacket can be effective. If thermal conductance is insufficient, fermenting must can be pumped through external heat exchangers, or cooling coils may be inserted directly into the fermentor. Alternatively, pumps can provide gentle agitation to avoid temperature stratification throughout the fermentor. In special fermentors, trapping carbon dioxide and the associated pressure buildup can be used to slow fermentation, minimizing heat accumulation.

Pesticide Residues

Under most situations, no more than trace amounts of pesticide residues are found in juice or must. At such concentrations, they have little or no perceptible effect on fermentation, wine quality, or human health. Used properly, pesticides help the fruit mature fully, reach maximal quality, and reduce the risks of mycotoxin contamination. When used in excess, or applied just before harvest, pesticides can negatively affect winemaking and potentially pose health risks.

Various factors influence pesticide residues on or in fruit. For example, heavy rains or sprinkler irrigation wash contact pesticides off the fruit. Rain has less effect on systemic pesticides (those absorbed into plant tissues). Solar ultraviolet radiation degrades some pesticides and decreases residual levels. Epiphyte and plant metabolic decomposition are also possible.

Crushing, and especially maceration, can influence the incorporation of crop-protection chemicals into the must. Depending on the fungicide, extended maceration can either increase or decrease the amount found in the juice. Maceration generally has little effect on the content of systemic pesticides. They are already in the juice before crushing.

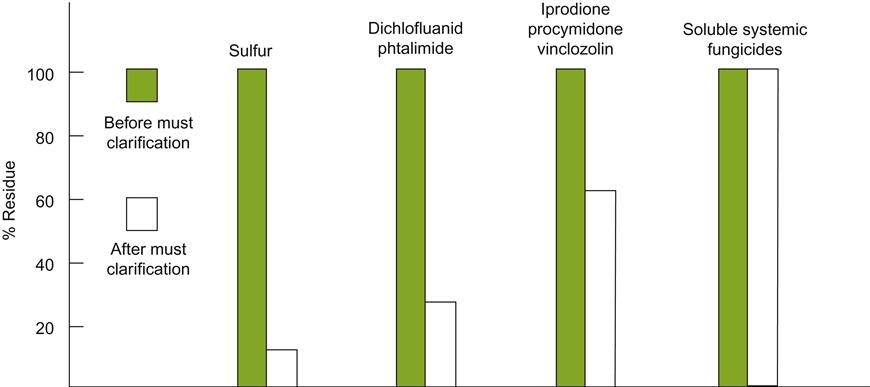

Clarification, either by cold settling, clarifying agents, or centrifugation, significantly reduces the concentration of contact fungicides, such as elemental sulfur, but has little effect on most systemic pesticide residues (Fig. 7.48). The persistence of pesticide residues, once dissolved, depends largely on their stability under the physicochemical conditions found in the ferment or wine. For example, more than 70% of dichlofluanid residues are degraded under the acidic conditions found in juice and wine (Wenzel et al., 1980). In contrast, differences in racking, clarification, and filtration procedures did not markedly reduce the concentrations of chlorpyrifos, fenarimol, vinclozolin, metalaxyl, mancozeb, and penconazole (Navarro et al., 1999). Nevertheless, for many commonly used pesticides, degradation or precipitation reduce their levels in finished wine to trace or undetectable levels (Sala et al., 1996; Fernández et al., 2005). There are also investigations into the value of washing grapes with a 1% solution of citric acid before crushing (Cavazza et al., 2007). Initial results appear encouraging.

Of pesticide residues, fungicides not surprisingly have the greatest effect on yeasts. Newer fungicides, such as metalaxyl (Ridomil®) and cymoxanil (Curzate®), do not appear to affect fermentation. In contrast, triadimefon (Bayleton®) can depress fermentation, presumably by disrupting sterol metabolism. Older, broad-spectrum fungicides, such as dinocap, captan, mancozeb, and maneb, generally are toxic to yeasts. Fungicides such as copper sulfate and elemental sulfur seldom have a significant effect, apart from at abnormally high concentrations (Conner, 1983). This tolerance may be related to the relative insensitivity of wine yeasts to other sulfur compounds, notably sulfur dioxide.

Fungicides can have several direct and indirect effects on fermentation. Delaying the start of fermentation is probably the most common. As this primarily affects the lag phase, subsequent fermentation is unaffected. Increasing the inoculum size (5–10 g/hL active dry yeast) avoids most fungicide-induced suppression of fermentation (Lemperle, 1988). The increased yeast population reduces the amount of fungicide available to react with each cell. Occasionally, the onset of fermentation occurs normally, but the rate is depressed (Gnaegi et al., 1983). Such suppression may result in stuck fermentation.

Fungicides occasionally may affect the sensory qualities of wine by influencing the relative activities of various yeast biosynthetic pathways. Residual elemental sulfur, applied as a fungicide, can augment the synthesis of hydrogen sulfide in some yeast strains (Fig. 7.49), as may Bordeaux mixture, folpet, and zineb. Although hydrogen sulfide favors the subsequent production of mercaptans, residual copper can limit mercaptan synthesis by forming insoluble cupric sulfide with H2S. Vinclozolin (Ronilan®) and iprodione (Rovral®) occasionally appear to affect fermentation and induce the development of off-flavors (San Romáo and Coste Belchior, 1982). In addition, fungicides may occasionally react with varietal flavor constituents, reducing their impact. An example is the effect of copper (in Bordeaux mixture) on reducing the content of 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one (4-MMP) in Sauvignon blanc wines (Hatzidimitriou et al., 1996). Copper reacts with 4-MMP during alcoholic fermentation and may also interfere with the synthesis of its precursor during grape maturation. Demonstration that newer fungicides are inactive against yeasts is often a requirement for registration of use on grapes.

Fungicides may also have selective effects on the endemic yeasts during vinification. For example, captan favors the growth of Torulopsis bacillaris by suppressing the growth of most other yeast species (Minárik and Rágala, 1966). Several herbicides (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid [2,4-D] and simazine) and most insecticides do not disrupt yeast fermentation (Conner, 1983; Cabras et al., 1995).

Stuck and Sluggish Fermentation

Stuck fermentation refers to the premature termination of fermentation before all but trace amounts of fermentable sugars have been metabolized. Clearly the best solution is avoidance. However, sluggish and stuck fermentations have been problems since time immemorial. Historically, their occurrence was usually attributed to overheating during fermentation. In the absence of adequate cooling, fruit harvested and fermented under hot conditions can readily overheat and fermentation become stuck. The resulting wines are high in residual sugar and low in alcohol content, making them unacceptable as a table wine, as well as highly susceptible to microbial spoilage. Instability is increased further if the grapes are low in acidity, high in pH, or both.

The current extensive use of temperature control has essentially eliminated overheating as a significant factor in stuck fermentation. Ironically, the application of cooling has favored the incidence of other causes of stuck wines. The desire to accentuate the fresh, fruity character of white wines has encouraged the use of cool temperatures. This can limit yeast growth and potentially favor microbial contaminants that further retard growth. The search for enhanced freshness has also induced some winemakers to use excessive juice clarification, either with bentonite, centrifugation, or similar procedures. The resulting loss of sterols, unsaturated fatty acids, and nitrogenous nutrients can increase yeast sensitivity to the combined toxicity of ethanol and carboxylic acids, notably octanoic and decanoic acids and their esters. The latter enhance ethanol-induced leakage of amino acids and other nutrients (Sá Correia et al., 1989). Octanoic acid and other stress factors such as ethanol, high temperature, and nitrogen deficiency also cause a reduction in intracellular pH and associated enzymic and membrane dysfunction (see Viegas et al., 1998). Crushing, pressing, and other prefermentative activities scrupulously conducted in the absence of oxygen heighten these effects. Molecular oxygen is required for the biosynthesis of sterols and long-chain unsaturated fatty acids essential for cell-membrane synthesis and function.

Juice from overmature and botrytized grapes generally has a very high sugar content. The resulting osmotic influence can partially plasmolyze yeast cells, resulting in slow or incomplete fermentation. In addition, overmature grapes may have an unusually low glucose-to-fructose ratio. This has been correlated with stuck fermentation in Switzerland (Schütz and Gafner, 1993b). It was solved by the addition of glucose to reestablish a more typical ratio. Overmaturity is also associated with reduced ammonia and amino acid content. This is further exacerbated in botrytized juice, which tends to have even lower available nitrogen and thiamine contents. The activity of indigenous yeasts can also reduce the thiamine content, thereby suppressing the activity of S. cerevisiae (Bataillon et al., 1996). Nutrient depletion adds to the combined inhibitory effects of high sugar contents and the toxicity of ethanol and C8 and C10 saturated carboxylic acids. Because these effects are well known, the juice is usually supplemented with DAP and thiamine. More difficult to counter are the inhibitory polysaccharides produced by B. cinerea (Ribéreau-Gayon et al., 1979) and the disruptive action of acetic acid released by acetic acid bacteria. Uptake of acetic acid can decrease the pH of yeast cytoplasm from about 7.2 to below 6. This disrupts protein function, notably the glycolytic enzyme enolase (Pampulha and Loureiro-Dias, 1990). The presence of 105–106 acetic acid bacteria/mL can be lethal to S. cerevisiae (Grossman and Becker, 1984).

If the juice is insufficiently protected by sulfur dioxide, and its pH is sufficiently high, indigenous lactobacilli may produce enough acetic acid to retard or inhibit fermentation. The best confirmed inhibitor is Lactobacillus kunkeei (Huang et al., 1996). Adding sulfur dioxide is the best-known means of controlling this relatively rare spoilage bacterium (Edwards et al., 1999). Conversely, excessive addition of sulfur dioxide can retard the growth of inoculated yeasts. Thus, as so often, sulfur dioxide should be employed judiciously, based on need not habit.

Another potential cause of stuck fermentation involves killer yeasts. Killer yeasts produce a protein toxic to yeast cells that do not themselves produce the protein. This feature is associated with joint infection by a mycovirus and satellite dsRNA. The mycovirus is considered a helper, regulating replication and encapsulation of the satellite dsRNA. The latter synthesizes a toxic protein. Although most killer proteins act only on the same species, forms are known that are active against other yeasts, as well as filamentous fungi and bacteria (see Magliani et al., 1997). These do not appear to be important in wine fermentations.

Under worst-case scenarios (low inocula with highly sensitive strains, or continuous fermentation), killer yeasts can replace inoculated strains, even when the initial concentration of the killer strain is as low as 0.1% (Jacobs and van Vuuren, 1991). Killer S. cerevisiae strains may cause sluggish or stuck fermentations, as well as donate undesirable sensory attributes. Even more serious are situations where potential spoilage yeasts, notably K. apiculata or Zygosaccharomyces bailii, possess killer factors that can inactivate inoculated S. cerevisiae.

This potential can largely be countered by inoculation with commercial strains constructed to possess both common killer satellite dsRNAs strains (K1 and K2) (Boone et al., 1990; Sulo et al., 1992). Possession of the killer factor protects the producing cell from the effects of the toxin. Addition of sulfur dioxide may also suppress killer yeasts in the indigenous flora, if combined with inoculation with a resistant wine yeast strain. Temperature control and the addition of bentonite can also reduce the activity of killer proteins.

Killer properties have been isolated from naturally occurring S. cerevisiae strains in wine, as well as other yeast genera (e.g., Hansenula, Pichia, Torulopsis, Candida, and Kluyveromyces). Although relatively uncommon, yeast strains resistant to killer toxins have been found that do not possess the killer factor. These are termed neutral strains. Typically, yeasts immune to a particular killer protein possess the gene that produces it.

Expression of the killer factor can vary among various yeasts. In S. cerevisiae, both K1 and K2 strains are associated with a helper virus of the totiviridae group, whereas in Kluyveromyces lactis linear dsDNA plasmids control the property. In some genera, chromosomal genes may be involved. In all cases, the toxic principle is associated with the production and release of a protein or glycoprotein.

With K1 and K2 toxins, toxicity involves the attachment of the protein to β-1,6-D-glucans of the cell wall. Subsequently, the toxin binds with a component of the cell membrane. It induces the formation of a pore, permitting unregulated ion movement across the membrane. The consequence is cell death. The nuclear genes that encode the killer proteins KHR and KHS are less well known, but also result in an increase in ion permeability of sensitive cells. In contrast, the K28 toxin attaches to α-1,3-mannose of cell-wall mannoproteins. It inhibits DNA synthesis and further cell division of the affected cell.

The killer proteins produced by S. cerevisiae, notably K1, act optimally at a pH above that normally found in wine. Consequently, K2 is of greater significance in wine production. Cells appear to be most sensitive during the exponential growth phase, when the growing tip of buds provide β-1,6-D-glucan receptors in close proximity to the cell membrane. Thus, the significance of killer toxins depends on juice pH, the addition of protein-binding substances (such as bentonite or yeast hulls), the ability of killer strains to ferment effectively, and the number of division cycles wine yeasts undergo during fermentation.

In general, the incidence of stuck fermentation may also be reduced by: limiting prefermentative clarification (restricting nutrient depletion); moderate aeration (~5 mg O2 /liter) at the end of the exponential growth phase; the addition of ergosterol or long-chain unsaturated fatty acids (i.e., oleic, linoleic, or linolenic acids); the addition of yeast ghosts or other absorptive materials, such as bentonite (associated with agitation to assure adequate mixing); or the addition of ammonium salts periodically or halfway through fermentation. The addition of absorptive substances, such as yeast hulls, appears to have optimal effects when applied midway or near the end of exponential growth.

The need for such treatments can be partially predicted by discovering the root cause(s) of past instances of stuck or sluggish fermentations. This is greatly aided by close scrutiny, and recording, of the conditions and dynamics of fermentation. These details provide a basis for diagnosing the cause(s), the commencement of early corrective measures, or preventive actions in the future. Yeast analysis may also provide additional clues. For example, specific genes are activated under low nitrogen conditions (Mendes-Ferreira et al., 2007).

Bisson and Butzke (2000) have divided problem fermentations into four categories: slow initiation (eventually becoming normal); continuously sluggish; typical initiation, but becoming sluggish; and normal initiation but abrupt termination. Their studies indicate that comparing sugar consumption, temperature, nutrient profiles, and records of procedures used in previous fermentations often provides early indications of potential problems and their possible quick resolution. Once fermentation has stopped, reinitiation is more complicated.

When stuck fermentation occurs, successful reinitiation usually requires incremental reinoculation with special yeast strains, following racking off from the settled lees (see Bisson and Butzke, 2000). The special strains usually possess high ethanol tolerance, as well as greater ability to utilize fructose (the sugar whose proportion can increase markedly during fermentation). The latter property appears to depend on the mutated activity of one of the multiple sugar transport proteins located in the plasma membrane – Hxt3 (Guillaume et al., 2007). The inoculum appears to be more successful if it is derived from colonies harvested in their stationary phase and exposed to ethanol (Santos et al., 2008). The addition of nutrients (if deficient), yeast hulls (to remove toxic fatty acids), must aeration, and adjustment of the fermentation temperature (if necessary) usually achieves successful refermentation.

Ideally, treatment should be based on the cause. However, this usually requires access to rapid laboratory analysis. Although available in large wineries, this may not be an option for small wineries. In this instance, use of one of the many commercial preparations for stuck fermentation is about the only solution once fermentation has ceased.

Typically, vintners do their best to avoid stuck fermentation. However, in the production of certain specialty sweet wines, premature termination can be intentional – usually by chilling and clarification to remove the yeasts. It achieves the low alcohol, high residual sweetness desired. Because such wines are particularly sensitive to microbial spoilage, stringent measure must be employed to counteract this tendency.

Malolactic Fermentation

After years of intensive investigation, the desirability of malolactic fermentation is finally becoming less controversial. The contention related to its seemingly capricious nature – at times improving quality, at others degrading it. Wines in which malolactic fermentation had its major benefits were those in which its occurrence was most problematic. In contrast, conditions that favored malolactic fermentation were often those where its occurrence was either unnecessary or detrimental.

The principal effects of malolactic fermentation are a rise in pH and a reduction in perceived acidity. This involves the decarboxylation of a dicarboxylic acid (malic acid) to a monocarboxylic acid (lactic acid). This replaces the harsher taste of malic acid with the less aggressive sensation of lactic acid. The malic acid content usually is reduced to less than 300 mg/L.

Winemakers in most cool wine-producing regions (where high acidity is usually associated with residual malic acid) tend to view malolactic fermentation positively, especially for red wines. Nonetheless, raising the pH can result in a loss of color. Conversely, wines produced in warm regions may be low in acidity, high in pH, or both. Thus, malolactic fermentation can aggravate an already difficult situation, potentially leaving the wine tasting ‘flat,’ with undesired flavors, and microbially unstable.

Deacidification is still the paramount reason for favoring/inducing malolactic fermentation. Recently, many winemakers have begun to view it as a means of adjusting and improving wine flavor. For example, it is thought to reduce the incidence of vegetal notes and accentuate fruit flavors (Laurent et al., 1994). Nonetheless, the reverse may occur (see below). Malolactic fermentation is most commonly promoted in red wines, but is also being encouraged with some white wines. Where desired, and for wines marginally high in pH, tartaric acid may be added prior to the induction of malolactic fermentation.

Lactic Acid Bacteria

Lactic acid bacteria are characterized by several unique properties. As their name implies, a major by-product of their metabolism is lactic acid. Depending on the genus and species, lactic acid bacteria ferment sugars solely to lactic acid, or to lactic acid, ethanol, and carbon dioxide. The former mechanism is termed homofermentation, whereas the latter is called heterofermentation. Homofermentation potentially yields two ATPs per glucose (similar to yeast fermentation), whereas heterofermentation yields but one ATP per glucose molecule. Species possessing either type of fermentation can grow in wine.

The most beneficial member of the group, from an enologic perspective, is the heterofermentative species, Oenococcus oeni (formerly Leuconostoc oenos). Recently, its genome has been deciphered (Mills et al., 2005). It contains 1701 ORFs (open reading frames). Of these, 75% have been classified as related to functional genes. This information is facilitating the study of its physiology and genetic diversity.

Not only is O. oeni the species most frequently found in wine, it is also the only species inducing malolactic fermentation in wines at a pH≤3.5. It is also more tolerant to ethanol, low temperatures, and sulfur dioxide than most other lactic acid bacteria. Spoilage forms are generally members of the genera Lactobacillus and Pediococcus (see the section on ‘Lactic Acid Bacteria’ in Chapter 8). Lactobacillus contains both homo- and heterofermentative members, whereas Pediococcus spp. are strictly homofermentative.

Although lactic acid bacteria are categorized on the basis of sugar fermentation, the extent to which sugar metabolism is important to their growth in wine is unclear. Even dry wines, possessing primarily trace amounts of pentose sugars, can support considerable bacterial growth. Intriguingly, the concentration of hexose sugars (glucose and fructose) may increase marginally during malolactic fermentation (Davis et al., 1986a). This increase, however, is apparently unrelated to malolactic fermentation, as it can occur in its absence.

Lactic acid bacteria are further distinguished as a group by their limited biosynthetic abilities. They require a complex set of nutrients, including B vitamins, purine and pyrimidine bases, and several amino acids. Indicative of their limited synthetic capabilities is their inability to synthesize heme proteins. As a consequence, they produce neither cytochromes nor catalase (both heme proteins). Without cytochromes, lactic acid bacteria cannot respire. Consequently, their energy metabolism is strictly fermentative.

Most bacteria incapable of synthesizing heme molecules are strict anaerobes – that is, they are unable to grow in the presence of oxygen. Oxygen reacts with certain cytoplasmic components, notably flavoproteins, producing toxic oxygen radicals (superoxide and peroxide). In aerobic organisms, superoxide dismutase and catalase rapidly inactivate these toxic radicals. Anaerobic bacteria produce neither enzyme. Lactic acid bacteria escape the fate of most anaerobic bacteria in the presence of oxygen (death) by accumulating large quantities of Mn2+ ions and producing peroxidase. Manganese detoxifies superoxide by converting it back to oxygen. The rapid action of manganese also limits the synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from superoxide. Peroxidase rapidly detoxifies any hydrogen peroxide that does form by oxidizing it to water in the presence of organic compounds. Lactic acid bacteria are the only procaryotes that are both strictly fermentative and able to grow in the presence of oxygen.

Although fermentative metabolism is an inefficient means of generating biologically useful energy, the production of large amounts of acidic wastes quickly lowers the pH of most substrates. As a consequence, the growth of most potentially competitive bacteria is arrested. Lactic acid bacteria are one of the few bacterial groups capable of growing below pH 5. This property permits lactic acid bacteria to grow in acidic environments. Although lactic acid bacteria grow under acidic conditions, growth is still comparatively poor at the low pH values typical of must and wine. For example, species of Lactobacillus and Pediococcus commonly cease growth below pH 3.5. Even Oenococcus oeni, the primary malolactic bacterium, is inhibited by pH values below 3.0–2.9. O. oeni grows optimally within a pH range of 4.5–5.5. Thus, a major benefit of malolactic fermentation, for the bacterium, is surprisingly acid reduction. By metabolizing malic to lactic acid, the number of carboxyl groups is halved, acidity is reduced, and the pH raised. The degradation of arginine, one of the major amino acids in must and wine, releases ammonia, which may also help raise pH. Raising the pH provides conditions more suitable for bacterial growth.

Another distinctive feature of lactic acid bacteria is the malolactic enzyme. Unlike other enzymes converting malic acid to lactic acid, the reaction decarboxylates L-malic acid to L-lactic acid, without free intermediates. The enzyme functions in a two-step process. First, malic acid is decarboxylated to pyruvic acid (which remains bound to the enzyme). Then, pyruvic acid is reduced to lactic acid. ATP is generated through the joint export of lactic acid and hydrogen ions (protons) from the cell (Henick-Kling, 1995). The hydrogen ions that accumulate outside the cell are sufficient to activate the phosphorylation of ADP to ATP in the cell membrane, where and as the ions move back into the cytoplasm.

A similar energy-producing mechanism is associated with the metabolism of citric acid. The metabolism of citric acid appears to assist the fermentation of glucose (Ramos and Santos, 1996). Small amounts of reducing energy (NADH) may also result from the action of a minor alternative oxidative pathway. It directly oxidizes malic acid to pyruvic acid. Some of the pyruvic acid so generated is subsequently reduced to lactic acid.

Although the decarboxylation of malic acid to lactic acid is central to the enologic importance of malolactic fermentation, malic acid is not the primary energy source for lactic acid bacteria. Currently, the primary energy source for these bacteria in wine is still in question. The source appears to change through the growth phase – initially involving small amounts of sugars (exponential phase), followed by malic acid (early stationary phase), and subsequently by citric acid (late stationary phase) (Krieger et al., 2000). The situation is complicated by the pronounced influence of pH on the ability of bacteria to ferment sugars, and the marked variability among strains. Oenococcus oeni appears to show little ability to ferment sugars, at least below pH 3.5 (Davis et al., 1986a; Firme et al., 1994). However, data from Liu et al. (1995) suggest that sugars may be the primary carbon and energy sources for the slow-growth phase of the bacteria. Growth may be increased by the joint metabolism of several compounds, such as glucose with fructose or citrate. This improves their redox balance and increases ATP production.

The metabolism of citric acid also has sensory significance. It is the prime source of the diacetyl, acetoin (Shimazu et al., 1985), and acetic acid generated during malolactic fermentation. Citric acid fermentation is enhanced by the presence of phenolic compounds (Rozès et al., 2003), as well as ethanol (Olguín et al., 2009).

Amino acids, notably arginine, may also act as energy sources (Liu and Pilone, 1998). The activity of O. oenion yeast and grape proteins may, thus, be important, both in terms of energy metabolism and in providing essential growth factors (De Nadra et al., 1997).

Although the high rate of malic acid conversion to lactic acid seems to account for much of the ATP required for maintenance during the log and stationary phases of malolactic fermentation (Henick-Kling, 1995), the energy dynamics associated with the initial growth phase under wine conditions remains contentious.

All lactic acid bacteria growing in wine assimilate acetaldehyde and other carbonyl compounds. However, their metabolism may retard malolactic fermentation. By shifting the equilibrium between bound and free carbonyls, inhibitory amounts of sulfur dioxide may be liberated. Recent experiments indicate that suppression is associated with bound forms of sulfur dioxide, not free sulfur dioxide (Wells and Osborne, 2011). Thus, the most significant influence may result from the release of sulfur dioxide inside the bacterium, as a consequence of acetaldehyde sulfonate uptake and metabolism – a microbial Trojan Horse.

As noted for anaerobic yeast metabolism, fermentation can result in the generation of an excess of NAD(P)H. To maintain an acceptable redox balance, the bacteria must regenerate NAD(P)+. How lactic acid bacteria accomplish this in wine is unclear. Some species reduce fructose to mannitol, presumably for this purpose (Nielsen and Richelieu, 1999; Richter et al., 2003). This may explain the common occurrence of mannitol in wine associated with malolactic fermentation. Some strains also regenerate NAD(P)+ with flavoproteins and oxygen. This reaction probably accounts for the reported improvement in malolactic fermentation in the presence of trace amounts of oxygen. However, oxygen also inactivates the pathway reducing pyruvate to ethanol – one of the means by which O. oeni regenerates NAD(P)+ for the metabolism of glucose.

In addition to important physiological differences, morphological features help to distinguish the various genera (Fig. 7.50). Oenococcus usually consists of spherical to lens-shaped cells (Plate 7.7). They commonly occur in pairs or chains, but occasionally singly. Leuconostoc mesenteroides, closely related to Oenococcus, may also be isolated from wine. Pediococcus species usually occur as packets of four spherical cells. Lactobacillus produces long, slender, occasionally bent, rod-shaped cells, commonly occurring in chains. Some of the lactic acid bacteria that may occur in wine are included in Table 7.4.

Effects of Malolactic Fermentation

Bacterial malolactic fermentation has three distinct, but interrelated, effects on wine quality. It reduces acidity, influences microbial stability, and affects the wine’s sensory attributes.

Acidity

Deacidification and a rise in pH are the most consistent effects of malolactic fermentation. This adjustment usually does not commence until the bacterial population has reached a threshold of about 108 cells per mL. A reduction in acidity increases the smoothness and drinkability of red wines, but can generate a flat taste in wines marginally low in acidity. The desirability of deacidification depends primarily on the initial pH and acidity of the grapes. Typically, the higher the acidity and the lower the pH, the greater the benefit; conversely, the lower the acidity and higher the pH, the greater the likelihood of undesirable consequences. In addition, the higher the relative proportion of tartaric acid in the juice, the less likely malolactic fermentation will significantly affect the acidity and pH of the wine.

As the pH of wine changes, so too do the relative concentrations of the various colored and uncolored forms of anthocyanins. The metabolism of carbonyl compounds (notably acetaldehyde) by lactic acid bacteria, and the accompanying release of any SO2 bound to them, can result in pigment bleaching. In general, color loss associated with malolactic fermentation is sensorially significant only in pale-colored wines, or those with an initially high pH.

Microbial Stability

Formerly, increased microbial stability was considered one of the prime benefits of malolactic fermentation. This view still holds, but its relative significance is now in some doubt and its mechanism uncertain.

Improved microbial stability was thought to result from the metabolism of residual nutrients left after alcoholic fermentation. It removed the more readily metabolized malic and citric acids, leaving the more microbially stable tartaric and lactic acids. In addition, the complex nutrient demands of lactic acid bacteria were thought to reduce the concentration of amino acids, nitrogen bases, and vitamins. Although their levels do tend to decrease, wines that have completed malolactic fermentation may still support the growth of Oenococcus oeni, or lactobacilli and pediococci (Costello et al., 1983), as well as other spoilage microorganisms.

Contrary to common belief, malolactic fermentation can occasionally decrease microbial stability. This can occur when the wine is marginally too high in pH. The resulting increase in pH can favor the subsequent growth of spoilage lactic acid bacteria. Spoilage organisms generally do not grow in wines at a pH below 3.5, but their ability to grow increases rapidly as the pH rises from 3.5 to 4.0 and above.

The stabilizing effect associated with malolactic fermentation may arise indirectly from the preservation practices applied after its completion. The onset and completion of malolactic fermentation permits the application of procedures, such as the addition of sulfur dioxide, storage at cool temperatures, and clarification, that are definitively preservative. Delayed onset, without the application of standard preservation techniques, exposes the wine to potential infection by acetic acid bacteria, spoilage lactic acid bacteria, and spoilage yeasts (notably Brettanomyces/Dekkera spp.). In the case of Brettanomyces, however, there is evidence that malolactic fermentation also reduces the presence of ethyl phenols, their principal spoilage by-product (Gerbaux et al., 2009). In addition, the early completion of malolactic fermentation avoids its possible, and undesirable, occurrence in bottled wine.

Flavor Modification

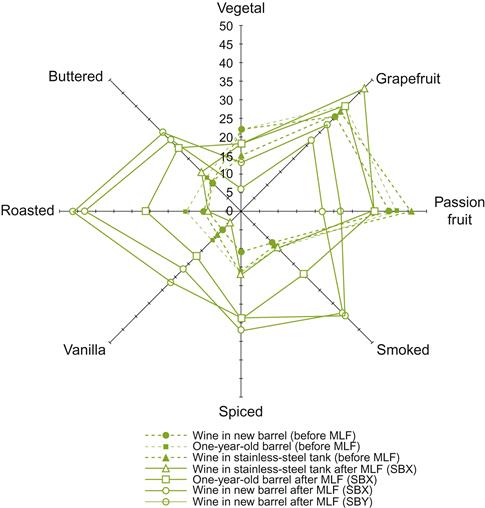

The greatest controversy concerning the relative merits, or demerits, of malolactic fermentation relates to flavor modification. The diversity of opinion undoubtedly reflects both the biologic and physicochemical conditions which exist during malolactic fermentation. For example, malolactic fermentation in barrels may enhance attributes characteristic of oak maturation, but diminish varietal attributes (Fig. 7.51). Varietal attributes, such as the apple and grapefruit-orange essences often detected in Chardonnay and the strawberry- raspberry attributes of Pinot noir wines, may be replaced by hazelnut, fresh bread, and dried fruit aromas, and animal and vegetable notes, respectively (Sauvageot and Vivier, 1997). In contrast, malolactic fermentation has been associated with increases in the fruity aspects of Cabernet Sauvignon wines (Bartowsky et al., 2011). Long-term studies on these sensory influences are needed.

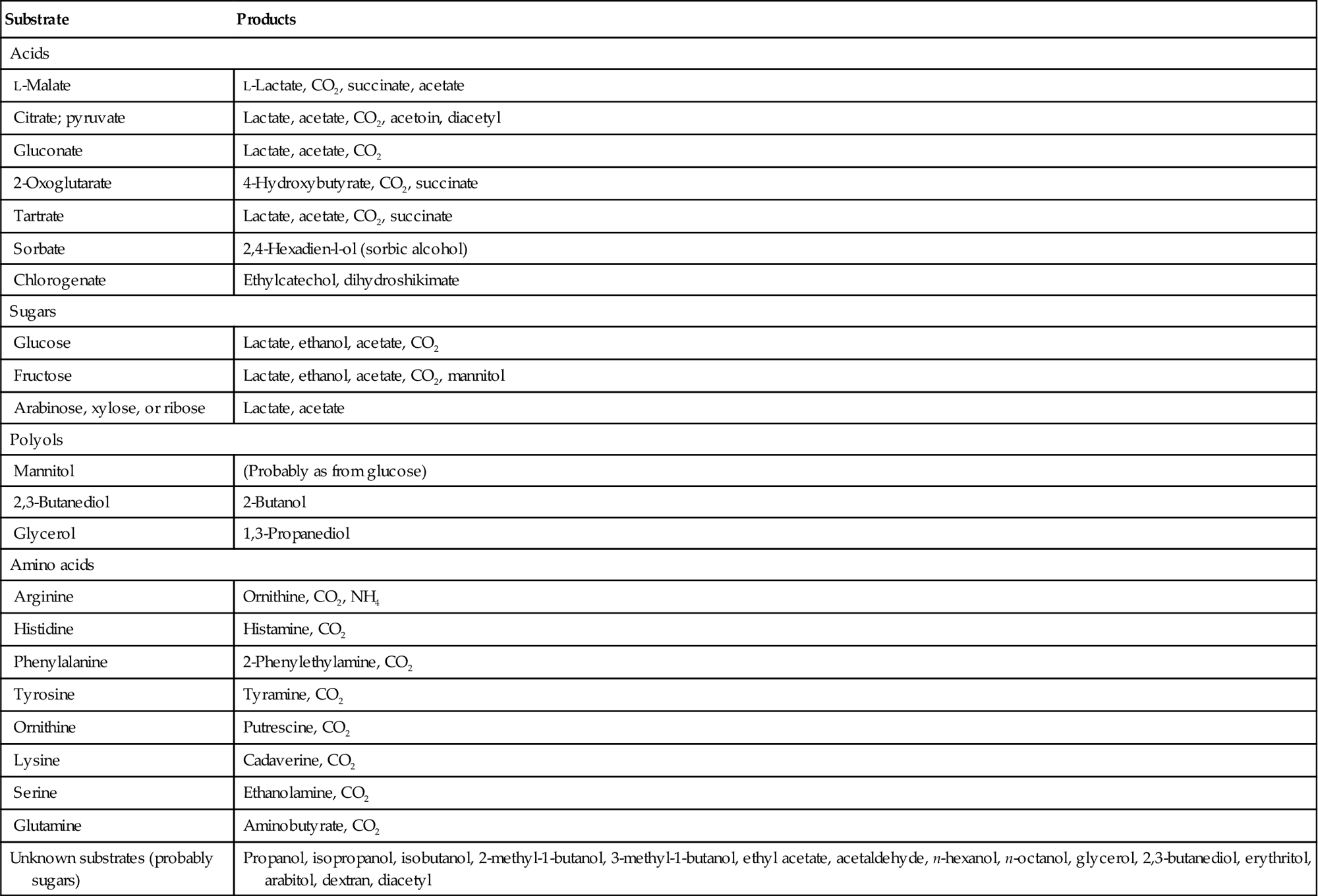

Considerable variation also depends on the strain and species of lactic acid bacteria involved (Laurent et al., 1994; Krieger, 1996). These influences are, in turn, affected by the wine’s temperature, pH, and varietal nature. Thus, it is not surprising that the relative sensory merits of malolactic fermentation are often contested. Table 7.5 lists some of the substrates metabolized and by-products produced by lactic acid bacteria. Figure 7.52 illustrates not only the influence of different bacterial strains, but also the response variability of two sets of panelists.

Table 7.5

Substrates and fermentation products of lactic acid bacteria

| Substrate | Products |

| Acids | |

| L-Malate | L-Lactate, CO2, succinate, acetate |

| Citrate; pyruvate | Lactate, acetate, CO2, acetoin, diacetyl |

| Gluconate | Lactate, acetate, CO2 |

| 2-Oxoglutarate | 4-Hydroxybutyrate, CO2, succinate |

| Tartrate | Lactate, acetate, CO2, succinate |

| Sorbate | 2,4-Hexadien-l-ol (sorbic alcohol) |

| Chlorogenate | Ethylcatechol, dihydroshikimate |

| Sugars | |

| Glucose | Lactate, ethanol, acetate, CO2 |

| Fructose | Lactate, ethanol, acetate, CO2, mannitol |

| Arabinose, xylose, or ribose | Lactate, acetate |

| Polyols | |

| Mannitol | (Probably as from glucose) |

| 2,3-Butanediol | 2-Butanol |

| Glycerol | 1,3-Propanediol |

| Amino acids | |

| Arginine | Ornithine, CO2, NH4 |

| Histidine | Histamine, CO2 |

| Phenylalanine | 2-Phenylethylamine, CO2 |

| Tyrosine | Tyramine, CO2 |

| Ornithine | Putrescine, CO2 |

| Lysine | Cadaverine, CO2 |

| Serine | Ethanolamine, CO2 |

| Glutamine | Aminobutyrate, CO2 |

| Unknown substrates (probably sugars) | Propanol, isopropanol, isobutanol, 2-methyl-1-butanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, ethyl acetate, acetaldehyde, n-hexanol, n-octanol, glycerol, 2,3-butanediol, erythritol, arabitol, dextran, diacetyl |

After Radler, 1986, reproduced by permission.

) and a wine research group (

) and a wine research group ( ). (From Henick-Kling et al., 1993, reproduced by permission.)

). (From Henick-Kling et al., 1993, reproduced by permission.)Prominent among the many malolactic by-products is diacetyl. At a concentration between 1 and 4 mg/liter, diacetyl may contribute positively to a wine’s fragrance (the threshold varying with the type of wine). It is often referred to as having a buttery, nutty, or toasty character. However, at concentrations above 5–7 mg/liter, its buttery character can become pronounced and undesirable. Mild aeration during malolactic fermentation dramatically increases diacetyl synthesis. Maximum accumulation correlates with the completion of malic and citric acid metabolism (Nielsen and Richelieu, 1999). Surprisingly, sensory differences among wines, with and without malolactic fermentation, often do not correlate with their diacetyl content (Martineau and Henick-Kling, 1995). In addition, presence of a buttery aspect does not necessarily correlate well with diacetyl contents (Bartowsky et al., 2002). Thus, even with a single compound, the sensory influence of malolactic fermentation is complex.

Other flavorants occasionally synthesized in amounts sufficient to affect a wine’s sensory character include acetaldehyde, acetic acid, acetoin, 2-butanol, diethyl succinate, ethyl acetate, ethyl lactate, and 1-hexanol. Much of the acetic acid associated with malolactic fermentation appears to be derived from citric acid metabolism. If the strain is a significant producer of acetic acid, it can leave the wine unacceptably high in volatile acidity.

Most lactic acid bacteria produce esterases. Although this could result in important losses in the fruity character of young wines, such decreases generally are negligible. Their enzymes work poorly at wine pH values (Matthews et al., 2007). Conversely, nonenzymatic synthesis of esters tends to increase during malolactic fermentation, especially ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate may also accumulate via direct bacterial biosynthesis. Many strains of lactic acid bacteria also produce β-glucosidases. If released in sufficient quantities, and not inhibited by unfavorable temperature and ethanol conditions (Spano et al., 2005), these enzymes could hydrolyze odorless glycosidic complexes, enhancing the development of a varietal character (D’Incecco et al., 2004). Enzymic activities may also modify oak aromatics (if malolactic fermentation occurs in wood cooperage) and change the wine’s soluble polysaccharide fraction (Dols-Lafargue et al., 2007). Oenococcus oeni may also contribute directly to the polysaccharide content of wine (separate from the occasional undesirable production of ropiness) (Ciezack et al., 2010).

The metabolism of arginine, which has a bitter, musty taste, could influence the taste perception of wines high in residual arginine. Occasionally, residual arginine values can reach the g/liter range. The disadvantage, however, is that incomplete arginine metabolism can liberate citrulline. Its reaction with ethanol can produce ethyl carbamate. Thankfully, this appears more likely with other lactic acid bacteria than Oenococcus oeni (Mira de Orduña et al., 2001), and tends to occur preferentially within a pH range higher than that typical of wine.

Malolactic fermentation has traditionally been encouraged more in red wines than in white wines. This preference may relate to the tendency of lactic acid bacteria to metabolize compounds responsible for an excessively vegetative, grassy aspect, for example the herbaceous aspect of Cabernet Franc wines (Gerland and Gerbaux, 1999). Oenococcus oeni also appears to increase the presence of C4 to C8 fatty acid ethyl esters and 3-methylbutyl acetate (Ugliano and Moio, 2005). In addition, red wines typically possess more flavor than white wines. Thus, they are less likely to be overpowered by malolactic flavors.

Oenococcus oeni can modify hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives to vinyl phenols, but is not known to decarboxylate them to ethyl phenols; however, other lactic acid bacteria can do this (Cavin et al., 1993). For example, Lactobacillus brevis, L. plantarum, and Pediococcus spp. can convert ferulic and p-coumaric acids to 4-ethylguaiacol and 4-ethylphenol. The production of these compounds can donate distinct phenolic or stable-like off-odors. At subthreshold levels, however, they may be of value in adding to a wine’s overall aromatic complexity. Because people differ markedly in their detection thresholds, this may help to explain why there is such diversity in opinion relative to the flavor influences of malolactic fermentation.

Also relating to phenolics, but in a clearly positive vein, O. oeni has the potential to enhance the concentration of several aromatic compounds, such as oak lactones, vanillins, and phenolic aldehydes. This has been noted for wines in which malolactic fermentation occurred in barrels (de Revel et al., 2005).

As a general rule, malolactic fermentations occurring below pH 3.5 (typically by Oenococcus oeni) rarely generate undesirable off-odors. Undesirable buttery, cheesy, or milky odors are usually confined to malolactic fermentation induced by pediococci or lactobacilli, at or above pH 3.5. Cold soak and sluggish fermentation conditions may also favor the generation of malolactic off-odors.

Amine Production

Lactic acid bacteria, notably the pediococci, produce amines via amino acid decarboxylation. Nonetheless, the prevalence of Oenococcus oeni indicates that it is the primary source of histamine production in wine. This may occur even after the bacteria are no longer culturable. The enzyme involved remains active in wine considerably longer than the producing bacteria (Coton et al., 1998). Thankfully, synthesis appears to be significant only in wines of high pH. Although some biogenic amines can induce blood-vessel constriction, headaches, and other associated effects, their contents in wine have not been demonstrated to be adequate to induce these physiological effects in humans (Radler and Fäth, 1991).

Origin and Growth of Lactic Acid Bacteria

The ancestral habitat of Oenococcus oeni is unknown. Although rarely isolated from grapes (Bae et al., 2006) or leaf surfaces, it has no known habitat other than wine. Its isolation from winery walls and equipment probably relates to wine residues. From the relatively small variation in its genetic makeup, O. oeni appears to have evolved from a few individuals that have specialized to grow in wine (Zavaleta et al., 1997). These appear to have subsequently spread worldwide.

The only other member of the genus is Oenococcus kitaharae. Its endemic habitat appears to be compost. Although closely related to O. oenococcus, it does not produce the malolactic enzyme, prefers growth at higher pH values, and expresses other distinctive physiologic attributes.

As noted, grape surfaces rarely possess colonies of Oenococcus oeni; neither are grapes a typical habitat for other lactic acid bacteria. Nonetheless, species of Pediococcus, Lactobacillus, and Leuconostoc may occur in the range of 103–104 cells/mL shortly after crushing (Costello et al., 1983). The population size depends largely on the maturity and health of the fruit – higher numbers occurring on mature, wounded, or infected fruit.

Although malolactic fermentation could be induced by bacteria originating from grape surfaces, spontaneous fermentations appear to usually originate from winery equipment. Stemmers, crushers, presses, and fermentors may harbor populations of lactic acid bacteria. The relative importance of grape versus winery sources in spontaneous malolactic fermentation has yet to be clearly enunciated.

The current trend is for winemakers to inoculate their wines with commercial strains when malolactic fermentation is desired. Of particular concern is avoiding slow, delayed, or partial fermentation, the production of off-flavors and high histamine levels, and the partial metabolism of arginine to citrulline. Citrulline and its breakdown product, carbamyl-P, can generate ethyl carbamate (a suspected carcinogen).

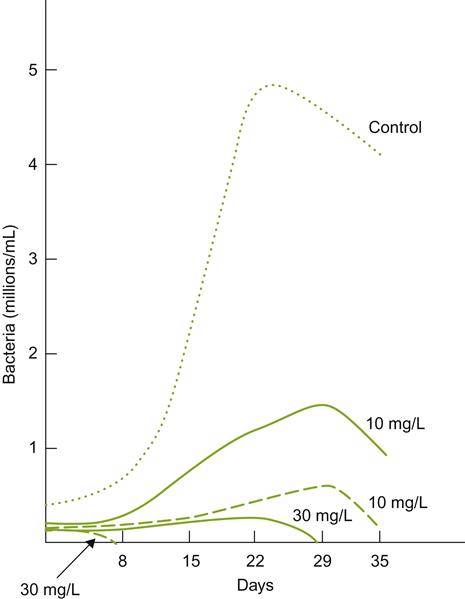

Unlike yeast growth during alcoholic fermentation, no consistent bacterial growth sequence develops in the must or wine during malolactic fermentation. A pattern occasionally found in spontaneous malolactic fermentations is shown in Fig. 7.53. Significant variations occur due to factors such as pH, total acidity, malic acid content, temperature, duration of skin contact, and grape cultivar (wine matrix).

Several strains of Oenococcus oeni may be present at the beginning of alcoholic fermentation. In spontaneous malolactic fermentations, the most common strains frequently disappear by the end of alcoholic fermentation. Malolactic fermentation is usually conducted by one or more of the strains that are initially uncommon (Reguant and Bordons, 2003). When malolactic fermentation is induced by inoculation, it is typical for the inoculated strain to dominate deacidification or, at least, be a common member of the population inducing malolactic fermentation (Bartowsky et al., 2003).

In most spontaneous fermentations, most pre-existing bacterial cells rapidly lyse as alcoholic fermentation begins. This reduces the bacterial population from about 1×103 to about 1 cell/mL. Most species of lactic acid bacteria initially found die out during alcoholic fermentation. Wines with pH values higher than 3.5 may show the temporary growth of species such as Lactobacillus plantarum. Although capable of producing ethyl phenols, these species may reduce oxidative browning by delaying the formation of xanthylium pigments from flavan-3-ols (Cureil et al., 2010). Occasionally, when sulfiting is low and the pH is above 3.5, Oenococcus oeni may induce malolactic fermentation coincident with alcoholic fermentation.

The usual initial population decline has been variously ascribed to sulfur dioxide toxicity, acidity, the synthesis of ethanol and toxic carboxylic acids, or the increasingly nutrient-poor status of fermenting must. All these factors may be involved to some degree. At the end of alcoholic fermentation, a lag period generally ensues before the bacterial population begins to rise. This phase may be of short duration, or it may last several months. Once growth initiates, the bacterial population may rise to 106–108 cells/mL. In most wines of low pH, only Oenococcus oeni grows. However, there can be variations in the proportion of various O. oeni strains throughout malolactic fermentation. At high pH values, species of both Lactobacillus and, especially, Pediococcus may predominate. Depending on the strain or species involved, malic acid decarboxylation may occur simultaneously with bacterial multiplication, or only after cell multiplication has ceased.

At the end of the exponential growth phase, the bacterial population enters a prolonged decline phase. The slope of the decline can be dramatically changed by cellar practices. For example, storage at above 20–25 °C, or the addition of sulfur dioxide, can result in a rapid dying off of Oenococcus oeni. If the pH is above 3.5, and other conditions are favorable, previously inactive strains of Lactobacillus or Pediococcus may begin to multiply. Their growth often produces a corresponding decline in the population of O. oeni. The nature of this apparently competitive antibiosis is unknown.

Factors Affecting Malolactic Fermentation

Growth conditions in wine are harsh for any bacterium – cool, acidic, alcoholic, anaerobic, low in nutrients, and possessing toxic fatty acids. Thus, Oenococcus oeni is exposed to many environmental stresses. Its relative tolerance to these factors appears to be under the control of a master regulator (CtsR) (Grandvalet et al., 2005). It controls the synthesis of a variety of stress response proteins, such as Hsps and Clp ATP-dependent proteases. The first group facilitates maintenance of proper protein folding, while the second degrades improperly folded proteins. In addition, the bacterium produces membrane-bound ATPases, thought to maintain cytoplasmic electrolytic balance. Many of these proteins are synthesized at specific phases of colony growth. The influence of several of these stress factors on bacterial growth and physiology are outlined below.

Physicochemical Factors

pH

The initial pH of juice and wine strongly influences not only if and when malolactic fermentation occurs, but also how and what species will conduct the process (Fig. 7.54). Low pH not only slows the rate, but also tends to delay the initiation of malolactic fermentation. Below a pH of 3.5, Oenococcus oeni is the predominant species inducing malolactic fermentation, whereas above pH 3.5 Pediococcus and Lactobacillus spp. become increasingly prevalent (Costello et al., 1983). Some of the inhibitory effects observed at low pH values are probably indirect, acting through increased cell-membrane sensitivity to ethanol and the enhanced proportion of molecular sulfur dioxide. The pH also significantly affects the composition and degree of unsaturation of cell-membrane fatty acids, similar to the effect of ethanol (Drici-Cachon et al., 1996).

Through these indirect influences, the pH modifies the metabolic activity of lactic acid bacteria. For example, sugar fermentation is much more effective at higher values. Similarly, the synthesis of acetic acid increases, whereas diacetyl production decreases in relation to increased pH (see Wibowo et al., 1985). The metabolism of malic and tartaric acid is also affected, with decarboxylation of malic acid being favored at low pH values, whereas the potential for tartaric acid degradation increases above pH 3.5. This results primarily from the preferential growth of Lactobacillus brevis and L. plantarum at higher pH values (Radler and Yannissis, 1972). This can lead to dramatic increases in wine pH, if both malic and tartaric acids (strong acids) are metabolized to lactic acid (a weak acid).

Temperature

The pronounced effect of temperature on malolactic fermentation has long been realized – often occurring in the spring when cellars began to warm. To speed its initiation, cellars may be heated to maintain the wine’s temperature above 20 °C. Although temperature directly affects bacterial growth rate, it most significantly influences the rate of malic acid decarboxylation. Maximal decarboxylation occurs between 20 and 25 °C, whereas growth is roughly similar within a range of 20–35 °C (Ribéreau-Gayon et al., 1975). Outside this range, decarboxylation slows dramatically. At temperatures below 10 °C, decarboxylation essentially ceases. In addition, most strains of Oenococcus oeni grow very slowly or not at all below 15 °C. Cool temperatures do maintain cell viability, though. Thus, wines cooled after malolactic fermentation commonly retain a high viable population for months. Temperatures around 25 °C favor a rapid decline in the O. oeni population (Lafon-Lafourcade et al., 1983), but can favor the growth of pediococci and lactobacilli.

Cellar Practices

Many cellar practices can affect when, and if, malolactic fermentation occurs. Maceration commonly increases the likelihood and early onset of malolactic fermentation (Guilloux-Benatier et al., 1989). The precise factors involved are unknown, but they may entail the action of phenols as electron acceptors in the oxidation of sugars during fermentation (Whiting, 1975). This would help to explain why malolactic fermentation develops more commonly in red wines than white wines. The higher pH of most red wines is undoubtedly involved as well.

Clarification can directly reduce the population of lactic acid bacteria by favoring their removal, along with yeasts and grape solids. Racking, fining, centrifugation, and other similar practices also remove nutrients, or limit their uptake into wine as a consequence of yeast autolysis.

Chemical Factors

Carbohydrates and Polyols

The chemical composition of must and wine has a profound influence on the outcome of malolactic fermentation. Carbohydrates and polyols constitute the most potentially significant group of fermentable compounds (Davis et al., 1986a). Most dry wines contain between 1 and 3 g/liter residual hexoses and pentoses. There are also variable amounts of di- and trisaccharides, sugar alcohols, glycosides, glycerol, and other polyols.

There is considerable heterogeneity among strains and species of lactic acid bacteria in their use of these nutrients. Ethanol and pH also influence their ability to ferment carbohydrates. Consequently, few generalizations about carbohydrate use appear possible. The major exception may be the poor use of most polyols. Few lactobacilli metabolize glycerol, the most prevalent polyol in wine. Although uncommon, glycerol metabolism can produce a bitter-tasting compound, acrolein (Meyrath and Lüthi, 1969).

Skin contact, before or during fermentation, promotes bacterial growth and malolactic fermentation. This is associated with an increased release of mannoproteins during fermentation, and reduced production of toxic mid-chain fatty (carboxylic) acids. A similar boost is also associated with sur lies maturation. Must clarification before fermentation appears to enhance the subsequent release of yeast polysaccharides, but also reduces the natural population of lactic acid bacteria (an important negative factor if early spontaneous malolactic fermentation is desired). Synthesis of α- and β-glucosidases in lactic acid bacteria increases in the presence of yeast polysaccharides, suggesting that polysaccharide hydrolysis may be a carbon source for cell growth (Guilloux-Benatier et al., 1993).

Occasionally, increases in the concentration of glucose and fructose have been noted following malolactic fermentation. These increases appear to be coincidental and not causally related. The sugars may arise from the nonenzymatic breakdown of various complex sugars, such as trehalose, from the hydrolysis of glycosides, or the liberation of sugars following the pyrolytic hydrolysis of hemicelluloses in oak.

Organic Acids

Although the decarboxylation of malic acid is the principal reason for promoting malolactic fermentation, other acids are also metabolized. Of particular importance is the oxidation of citric acid. It is associated with the synthesis of acetic acid and diacetyl (Shimazu et al., 1985). Few bacteria in wine, other than O. oeni, appear to metabolize citric acid. Where the flavor of diacetyl is undesired, a commercial strain of O. oeni (CiNi) is available that does not metabolize citrate. Gluconic acid, characteristically found in botrytized wines, is also metabolized by lactic acid bacteria, with the exception of the pediococci. Some lactic acid bacteria, notably the lactobacilli, have been reported to degrade tartaric acid (Radler and Yannissis, 1972). This has been associated with a wine fault called tourne.

The relative significance of organic acid metabolism to the energy budget of lactic acid bacteria is unclear. Both malic and citric acids are fermented after the major growth phase, when bacteria enter the stationary phase. The decarboxylation of malic acid, and the subsequent release of lactic acid from the cell, activates H+ uptake via membrane-bound ATPase. This is associated with the generation of ATP. A small proportion of malic acid is also metabolized directly to lactic acid. This may generate reducing power (NADH).

Fumaric acid addition was once proposed as an inhibitor of malolactic fermentation. However, its activity decreases dramatically at pH values above 3.5 (Pilone et al., 1974). Thus, it becomes progressively ineffective under the precise conditions where protection is increasingly needed.

The rise in pH associated with malic acid decarboxylation is particularly a problem when sorbic acid has been added to control spoilage yeasts in sweet wines. Metabolism of sorbic acid by lactic acid bacteria results in the formation of 2-ethoxyhexa-3,4- diene, a compound possessing a strong geranium-like off-odor.

The ability of lactic acid bacteria to metabolize or tolerate fatty acids is largely unknown. However, some fatty acids are toxic to lactic acid bacteria, notably octanoic, decanoic, and dodecanoic acids produced by yeasts. These are more inhibitory in their acidic forms, but more cytotoxic in their esterified forms (Guilloux-Benatier et al., 1998). Tolerance to their toxicity is one of the multiple features for which current strain selection and/or breeding is being conducted. Adsorption of these acids onto added yeast hulls helps diminish their toxicity.

Nitrogen-Containing Compounds

Lactic acid bacteria are noted for their complex nitrogen growth requirements. Nonetheless, few generalizations about the nitrogen composition of wines by lactic acid bacteria appear evident (Remize et al., 2006). For example, the concentration of individual amino acids may increase, decrease, or remain stable during malolactic fermentation. Simple interpretation of the data is confounded by the release of bacterial proteases. These hydrolyze soluble proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. Of these, transporting peptides is more energy-efficient than the uptake of individual amino acids. The latter have higher energy requirements. Besides grapes, an additional important source of nitrogenous compounds is yeast autolysis.

Of amino acids, only the concentration of arginine appears to change consistently during malolactic fermentation. This involves its bioconversion to ornithine. The conversion is associated with the generation of ATP. Arginine uptake, along with fructose, also activates stress-responsive genes that enhance survival (Bourdineaud, 2006).

Where reduction in amino acid content is evident, it is probably associated with their uptake and incorporation into proteins. The direct uptake and utilization of ammonia apparently does not occur.

Ethanol

At low concentrations (1.5%), ethanol appears to favor bacterial growth (King and Beelman, 1986). At higher concentrations, it progressively retards bacterial growth, and even more effectively inhibits malolactic fermentation (Fig. 7.55). Of lactic acid bacteria, Lactobacillus is the most ethanol-tolerant. For example, L. trichodes can grow in wines at up to 20% ethanol (Vaughn, 1955). A few strains of Oenococcus oeni grow in culture media at up to 15% alcohol (Guzzon et al., 2009). This trait in O. oeni is becoming more important as the production of table wines with high alcohol contents expands. Modified inoculation procedures appear also to have some benefit in acclimating O. oeni to higher alcohol levels (Zapparoli et al., 2009). Alcohol tolerance appears to decline, both with increasing temperature and decreasing pH values.

, 0%; ■, 5%;

, 0%; ■, 5%;  , 8%;

, 8%;  , 11%;

, 11%;  , 13% ethanol. (From Guilloux-Benatier, 1987, reproduced by permission.)

, 13% ethanol. (From Guilloux-Benatier, 1987, reproduced by permission.)The source of the toxic action of ethanol is unknown, but presumably involves changes in the semifluid nature of the plasma membrane. These changes can induce enhanced passive H+ ion influx and loss of cellular constituents (Da Silveira et al., 2003). A reduction in the concentration of neutral lipids and an increase in the proportion of glycolipids have been correlated with high alcohol concentrations (Desens and Lonvaud-Funel, 1988). Ethanol tolerance has also been associated with an increased synthesis of certain phospholipids (phosphoethanolamine and sphingomyelin), and the incorporation of lactobacillic acid in the plasmalemma (Teixeira et al., 2002).

Alcohol-induced membrane malfunction could explain growth disruption, reduced viability, and poor malolactic fermentation at high alcohol contents. Up to an 80% reduction in the rate of malic acid decarboxylation has been reported with an increase in alcohol content from 11 to 13% (Lafon-Lafourcade, 1975).

Other Organic Compounds

During malolactic fermentation, lactic acid bacteria assimilate a wide range of compounds. Occasionally, this can affect the progress of malolactic fermentation. The most well-known example involves the metabolism of carbonyl hydroxysulfonates. This has the potential to liberate sufficient SO2 to slow or terminate malolactic fermentation.

Many lactic acid bacteria produce esterases. Despite this, the concentration of most esters, such as 2-phenethyl acetate and ethyl hexanoate, changes little during malolactic fermentation. Any reductions that occur appear to be insufficient to cause sensory impact. Other esters, such as ethyl acetate, ethyl lactate, and diethyl succinate, may increase. Although the last two are unlikely to have a perceptible impact, due to their low volatility, increased ethyl acetate content could donate an off-odor, resembling nail-polish remover (acetone).

Various phenolic acids, such as ferulic, quinic, and shikimic acids, as well as their esters, are metabolized by some lactic acid bacteria. Lactobacillus spp. are notable in this regard. One of the dubious consequences can be the generation of volatile phenolics, such as ethylguaiacol and ethylphenol. Even at low concentrations these compounds have spicy, medicinal, creosote-like odors (Whiting, 1975). Because these fragrances do not characterize malolactic fermentations, their synthesis is probably too minimal to be perceptible.

At the concentrations generally found in wine, grape phenolics do not seriously retard malolactic fermentation, even though they have the potential to inhibit growth (Campos et al., 2009). In contrast, anthocyanins and gallic acid appear to favor bacterial viability (Vivas et al., 1997). Nevertheless, leaving stems in the ferment can delay the onset and somewhat slow the rate of malolactic fermentation (Feuillat et al., 1985). This may also result from extended maturation in oak cooperage, with ellagitannins suppressing cell viability slightly (Vivas et al., 1995). In this regard, how the oak is treated during barrel assembly appears to be of particular significance. For example, the growth of Oenococcus oeni was favored when the wood was toasted, but retarded without firing (de Revel et al., 2005).

Fermentors

Malolactic fermentation often occurs in the same fermentor as alcoholic fermentation, before racking and maturation. Formerly, malolactic fermentation more frequently occurred in oak barrels after transfer from the fermentation tank. Vivas et al. (1995) have noted that the color intensity and stability of red wine are increased following malolactic fermentation in oak cooperage. This has been correlated with increased anthocyanin–tannin polymerization. In addition, astringency is also apparently reduced, generating a smoother, richer wine. The researchers also comment that oak and fruit flavors are more balanced and harmonious. These perceptions persisted for at least 3 years after bottling. In addition, lactic acid bacteria facilitate the release of vanillin from oak by hydrolyzing glycoside precursors (Bloem et al., 2008).

Gases

Sulfur dioxide can markedly inhibit malolactic fermentation. The effect is complex due to the differing concentrations and toxicities of its many states in wine. As usual, free forms are more inhibitory than bound forms (Fig. 7.56). Of the free forms, molecular SO2 is the most antimicrobial. Wine pH significantly influences the toxicity of sulfur dioxide by affecting the relative proportions of these forms. Temperature also dramatically influences sensitivity (Lafon-Lafourcade, 1981). In all cases, however, the effect is more bacteriostatic than bactericidal (Delfini and Morsiani, 1992). Part of the inhibitory effect (and other factors such as ethanol and toxic fatty acids) appears to be due to disruption of ATPase activity (Carreté et al., 2002).

; free SO2, - - - - -. (From Lafon-Lafourcade, 1975, reproduced by permission.)

; free SO2, - - - - -. (From Lafon-Lafourcade, 1975, reproduced by permission.)Different species and strains vary considerably in their sensitivity to sulfur dioxide. In general, strains of Oenococcus oeni are particularly sensitive. Because of the greater tolerance of pediococci and lactobacilli to SO2, they may be unintentionally selected by sulfur dioxide addition, especially in high pH wines. Thus, where sulfur dioxide is added, it is judicious to inoculate the must or wine with a known sulfur dioxide-resistant strain of O. oeni.

Although lactic acid bacteria are strictly fermentative, small amounts of oxygen can favor malolactic fermentation. As the bacteria neither respire nor require sterols or unsaturated fatty acids for growth, oxygen may act by improving the redox balance via reaction with flavoproteins.

The significance of carbon dioxide to malolactic fermentation is somewhat controversial. One potential mechanism for involvement may be the production of oxaloacetate, via the carboxylation of pyruvate. This could both help maintain a desirable redox balance and favor amino acid biosynthesis.

Pesticides

Little is known about the possible effects of pesticide residues on the action of lactic acid bacteria. Vinclozolin and iprodione have been reported to depress malolactic fermentation, and increase the growth of acetic acid bacteria (San Romáo and Coste Belchior, 1982). Cymoxanil (Curzate) and dichlofluanid (Euparen) have also been reported to inhibit malolactic fermentation (Haag et al., 1988). Copper equally has an inhibitory effect, with the delay in malolactic fermentation being accentuated at higher ethanol and sulfur dioxide concentrations and lower pH values (Vidal et al., 2001). In contrast, benalaxyl, carbendazim, tridimefon, and vinclozolin were found to have no effect on lactic acid bacteria (Cabras et al., 1994). Of seven fungicides and three insecticides tested by Ruediger et al. (2005), only the insecticide dicofol was found to have an inhibitory effect on malolactic fermentation.

Biological Factors

Biological interactions in malolactic fermentation are as intricate as the complex interplay of physical and chemical factors already noted. Although mutually beneficial effects may occur, most interactions appear to negatively affect growth.

Yeast Interactions

Occasionally, alcoholic and malolactic fermentation occur simultaneously. In this instance, lactic acid bacteria occasionally exert an inhibitory effect on yeast growth, causing stuck fermentations. More commonly, though, yeasts inhibit bacterial growth (Edwards et al., 1990). Cryotolerant yeasts, which are more commonly used with white wines, appear to be more inhibitory than other strains (Caridi and Corte, 1997). There is also marked sensitivity differences among O. oeni strains. Recent laboratory tests may help winemakers determine, in advance, whether, and to what degree, particular yeast and bacterial strain combinations are compatible (Costello et al., 2003; Arnink and Henick-Kling, 2005). This could avoid the often prolonged delay between the completion of alcoholic fermentation and the onset of malolactic fermentation. Nonetheless, cessation of bacterial growth does not necessarily inhibit malolactic fermentation, if the population is already at the point were malolactic fermentation is possible. Spoilage yeasts, such as Pichia, Candida, and Saccharomycodes, can also retard, if not inhibit, malolactic fermentation.

Various explanations have been offered for the inhibitory action of yeast growth. Suppression by Saccharomyces bayanus (Nygaard and Prahl, 1996) has been associated with its production of SO2 (Larsen et al., 2003), and the high alcohol tolerance of this yeast species (resulting in a slow loss in its viability, the onset of autolysis, and associated release of nutrients). The depletion of arginine and other amino acids during the early phases of alcoholic fermentation is another possibility. Certain yeast strains coprecipitate with bacteria, removing them from the wine and thus delaying malolactic fermentation. The increasing ethanol content and the accumulation of toxic carboxylic acids (notably octanoic and decanoic acid) are also likely involved (Lafon-Lafourcade et al., 1984). Furthermore, proteins with antibacterial activities (e.g., lysozyme) have been isolated from some strains of S. cerevisiae (Dick et al., 1992). Whether this is related to the selectively toxic, proteinaceous agent identified by Comitini et al. (2005) is unknown. Osborne and Edwards (2007)have also isolated a peptide from S. cerevisiae that inhibits malolactic fermentation.

After alcoholic fermentation, yeast cells die and begin to undergo autolysis. The associated release of nutrients may explain the initiation (or reinitiation) of bacterial growth after the completion of alcoholic fermentation. Thus, leaving wines in contact with the lees for several weeks tends to encourage malolactic fermentation. Although nutrient release is undoubtedly involved, the maintenance of a high dissolved CO2 concentration in the lees (Mayer, 1974) and the release of mannoproteins (Guilloux-Benatier et al., 1995) also appear to be involved (Fig. 7.57). Mannoproteins not only inactivate toxic fatty acids, but also provide nutrients when decomposed by bacterial β-glucosidases and proteases.

Surprisingly, malolactic fermentation may be stimulated in botrytized juice (San Romáo et al., 1985). This occurs in spite of the well-known reduction in available nitrogen content. Growth promotion may result from the metabolism of acetic acid (found in higher concentrations in botrytized grapes), or the removal of toxic carboxylic acids (adsorbed by Botrytis-synthesized polysaccharides). Regrettably, the increased glycerol content of the juice can favor the development of the wine fault, mannitic fermentation, if acidity is too low.

Bacterial Interactions

The activity of acetic acid bacteria often favors malolactic fermentation during alcoholic fermentation. This may result indirectly from their suppression of yeast growth (resulting in higher nutrient levels and lower concentrations of alcohol and toxic carboxylic acids), or directly by growth enhancement through the use of acetic acid as a nutrient.

Internal competition/antibiosis between Oenococcus oeni strains is suggested by changes in the relative proportions of different strains throughout malolactic fermentation. More importantly, there may be antagonism between different species of lactic acid bacteria. Such antagonism is rare below pH 3.5, at which typically only O. oeni grows. However, above pH 3.5, pediococci and lactobacilli progressively have a selective advantage over O. oeni. Antagonism seems clearest when a decline of O. oeni is mirrored by an equivalent rise in the number of lactobacilli and pediococci. The mechanism(s) of this apparent antagonism are unknown.

Viral Interactions