Post-Fermentation Treatments and Related Topics

Post-fermentation treatments may begin almost immediately after fermentation. These may involve any necessary adjustments to the wine’s physicochemical composition, as well as procedures such as sur lies maturation. Subsequent modifications involve various forms of clarification and fining, and chemical and biologic stabilization (including oxidation control). Both before and after bottling, further spontaneous chemical changes occur (aging). These affect the wine’s visual, gustatory, and olfactory attributes, with potential beneficial or detrimental consequences. These changes may occur in either inert or wood containers. Because of the significance of maturing premium wines in barrels before bottling, the taxonomy, distribution, and structural and chemical attributes of oak are noted, as well as barrel construction, conditioning, and care, as well as their alternatives. The origin and chemical and physical attributes of cork are explored, as well as stopper production, insertion, faults, and sorting, plus closure alternatives. The properties and production of various storage/transport containers (notably glass) are subsequently described. A discussion of wine spoilage follows including: cork-related problems; the various forms of microbial spoilage; sulfur and other off-odor development and control; and accidental contamination. An examination of winery waste water and treatment completes the chapter.

Keywords

wine; post-fermentation; sur lies; stabilization; clarification; fining; wine aging; oak; barrels; cork; wine spoilage; off-odors; winery waste water treatment

All wines undergo a period of adjustment (maturation) before bottling. Maturation involves the deposition and/or removal of particulate and colloidal material. In addition, the wine undergoes a range of physical, chemical, and biological changes that usually maintain or improve its sensory qualities. Many of these changes occur spontaneously, but may be promoted by the winemaker to speed their occurrence. Although undue intervention can disrupt the wine’s inherent attributes, shunning any intervention can be equally deleterious. What is important is that rational, data-based action takes precedence, not philosophical (or marketing) dictates.

Wine Adjustments

Adjustments attempt to correct deficiencies found in the grapes and/or sensory imbalances that developed during fermentation. In certain jurisdictions, certain types of adjustments to acidity and sweetness are permitted only before fermentation. This is regrettable, because it is impossible to predict the course of fermentation precisely. Judicious adjustment after vinification can improve the wine so that its stylistic, geographic, and varietal attributes can be fully expressed. Regrettably, once enacted, laws seem to develop a life of their own, independent of need or logic.

Acidity and pH Adjustment

Theoretically, acidity and pH adjustment can be conducted at almost any stage during vinification. Nevertheless, postfermentative correction is probably optimal. During fermentation, deacidification often occurs spontaneously, due to acid precipitation or yeast and bacterial metabolism. In addition, some strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae synthesize significant amounts of malic acid during fermentation (Farris et al., 1989). Thus, the truest assessment of wine acidity and any need for adjustment is possible only at the end of fermentation. However, if the juice is above pH 3.4, prefermentative lowering of the pH is advisable. It favorably influences fermentation and avoids large adjustments following fermentation, especially with white wines.

Typically, red wines have higher pH values than white wines. This partially results from red wines being more frequently produced in warmer regions. Therefore, they tend to have lower malic acid contents at harvest. In addition, more potassium is extracted during the extended maceration red wines receive. Consequently, more tartaric acid exists in a salt form. These have a greater tendency to crystallize and precipitate than non-salt forms.

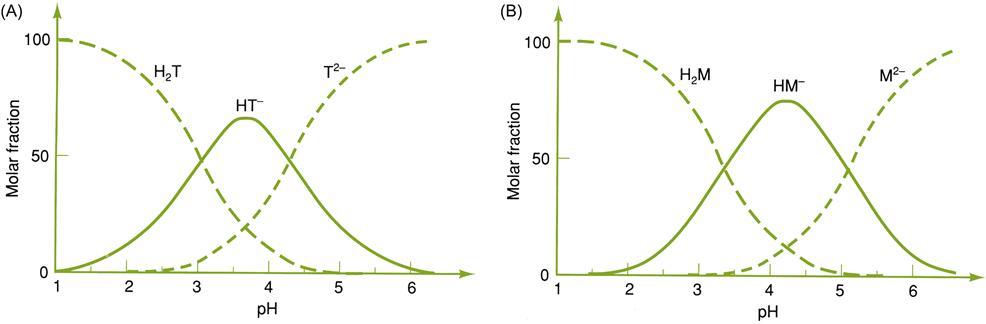

Precise recommendations for optimal acidity are impossible. They reflect stylistic, regional, and traditional preferences. More fundamentally, acidity and pH are complexly interrelated. The major fixed acids in grapes (tartaric and malic) occur in a dynamic equilibrium of ionized and nonionized states (Fig. 8.1). These include undissociated (nonionized) acids, half-ionized states (with one ionized carboxyl group), fully ionized states (with both carboxyl groups ionized), half-salts (with one carboxyl group associated with a cation), full salts (with both carboxyl groups bound to cations), or as double salts with other acid molecules and cations. The proportion of these interconvertible states depends largely on the pH, concentration of the respective acids, and potassium ions. Because of the complexity of the equilibria, and how they are affected by wine colloids, precise prediction of the consequences of changing any one of these factors on acidity is nigh impossible. Nevertheless, a range between 0.55 and 0.85% total acidity is generally considered appropriate. Red wines are customarily preferred at the lower end of the range, whereas white wines are preferred at the upper end.

Another important aspect of acidity is pH. It represents the proportion of H+ to OH− ions in an aqueous solution – the higher the proportion of H+ ions, the lower the pH; conversely, the higher the proportion of OH− ions, the higher the pH. Wines vary considerably in pH, with values below 3.1 being perceived as sour, and those above 3.7 being considered flat. White wines are commonly preferred at the lower end of the pH range, whereas red wines are frequently favored in the midrange.

Relatively low pH values in wine are preferred for many reasons: they give wines their fresh taste; improve microbial stability; reduce browning; diminish the need for SO2; and enhance the production and stability of fruit esters. The concentrations of monoterpenes may also be affected (Rapp et al., 1985). For example, the concentration of geraniol, citronellol, and nerol may rise at low pH values, whereas those of linalool, α-terpineol, and hotrienol decline. In red wines, color intensity and hue are enhanced at lower pH values.

Because of the importance of pH, the method of acidity-correction is influenced considerably by how it affects pH. Because tartaric acid is more highly ionized than malic acid, within the usual range of wine pH values, adjusting the concentration of tartaric acid has a greater effect on pH than an equivalent change in the concentration of malic acid (Fig. 8.2). Thus, adjusting the concentration of tartaric acid affects pH more than total acidity. In contrast, adjusting malic acid content affects total acidity more than pH. Which is preferable depends on the rationale for adjustment. Prefermentative adjustments are discussed in Chapter 7.

Deacidification

Wine may be deacidified by either physicochemical or biological means. Physicochemical deacidification involves either acid precipitation or column ion-exchange. Biological deacidification usually involves malolactic fermentation (see Chapter 7).

The advantages of eliminating excess acidity extend beyond simply removing an excessively sour taste. One of the side-benefits relates to shifts in wine fragrance. The effect on monoterpene concentration has already been noted. In addition, pH can modify the equilibrium between glycosides and esters, and their aglycones and constituent acids and alcohols, respectively.

Precipitation

Precipitation primarily entails the neutralization of tartaric acid; malic acid is less involved due to the higher solubility of its salts. Neutralization occurs when cations (positively charged ions) of a salt exchange with hydrogen ion(s) of an acid. Salt formation can reduce acid solubility, inducing crystallization and precipitation. The removal of the precipitated salt during racking, filtration, or centrifugation makes the reaction irreversible.

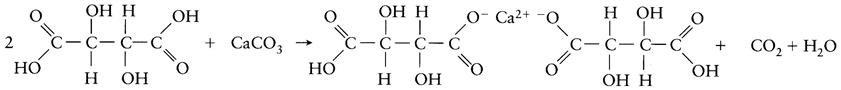

To induce the neutralization and precipitation of tartaric acid, finely ground calcium carbonate may be added to the wine. The reaction produces a calcium double salt of tartaric acid.

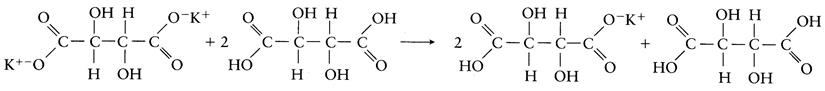

Neutralization can also result from the formation of insoluble half salts. Deacidification with potassium tartrate by this method is illustrated below.

Of available methods, deacidification with calcium carbonate is probably the most common. Of alternate procedures, the use of potassium tartate is more expensive and potassium carbonate prohibited in several countries. Although widely used, calcium carbonate has a number of disadvantages. Its primary drawback is the slow rate at which calcium tartrate precipitates. In addition, formation of calcium malate may generate a salty taste if the wine has not already undergone malolactic fermentation. Furthermore, if tartrate removal is excessive, the resulting increase in pH may leave the wine with a flat taste, and increase susceptibility to microbial spoilage.

Some of the disadvantages of calcium carbonate addition may be avoided using double-salt deacidification. The name refers to the belief that the technique functioned primarily via the formation of an insoluble double calcium salt between malic and tartaric acids. It now appears that very little of the hypothesized double salt actually forms. Nonetheless, the procedure does both speed the precipitation of calcium tartrate and facilitate the partial precipitation of calcium malate (Cole and Boulton, 1989).

The major difference between the single- and double-salt procedures is that the latter involves the addition of calcium carbonate to only a small proportion (~10%) of the wine to be deacidified. Sufficient calcium carbonate is added to raise the pH to above 5.1. This assures adequate dissociation of both malic and tartaric acids (see Fig. 8.2). It also induces the rapid formation and precipitation of the salts. A patented modification of the double-salt procedure (Acidex) incorporates 1% calcium malate–tartrate with the calcium carbonate. The double salt possibly acts as seed crystals, promoting rapid crystallization.

In double-salt procedures, the remainder of the wine is slowly blended back into the treated portion, with vigorous stirring. Subsequent crystal removal occurs by filtration, centrifugation, or settling. Stabilization may take 3 months, during which residual salts precipitate before bottling.

Although precipitation works well with wines of medium to high total acidity (6–9 g/mL), and medium to low pH (<3.5), it can result in an excessive pH rise in wines showing both high acidity (>9 g/mL) and high pH (>3.5). This situation is most common in cool climatic regions, where malic acid constitutes the major acid and the potassium content is high. In this situation, column ion exchange may be used (Bonorden et al., 1986), or tartaric acid may be added to the wine before the addition of calcium carbonate in double-salt deacidification (Nagel et al., 1988). Precipitation following neutralization removes the excess potassium with acid salts, and the added tartaric acid lowers the pH to an acceptable value.

Because protective colloids can significantly affect the precipitation of acid salts, it is important to conduct deacidification trials on small samples of the wine. This will establish the amount of calcium carbonate or Acidex required for the desired degree of deacidification.

Ion-Exchange Column

Ion exchange involves passing the wine through a resin-containing column. During passage, ions in the wine exchange with those in the column. The types of ions replaced can be adjusted by modifying the type of resin and ions present.

For deacidification, the column is packed with an anion-exchange resin. Tartrate ions are commonly exchanged with hydroxyl ions (OH−), thus removing tartrate from the wine. The hydroxyl ions released from the resin associate with hydrogen ions, forming water. Alternatively, malate may be removed by exchange with a tartrate-charged resin. The excess tartaric acid may be subsequently removed by neutralization and precipitation. The major limiting factor in ion-exchange use, other than legal restrictions and cost, is its tendency to remove flavorants and color from the wine, reducing wine quality.

Biological Deacidification

Biological deacidification, via malolactic fermentation, is possibly the most common means of acidity correction. Because malolactic fermentation can occur before, during, and after alcoholic fermentation, it is discussed in Chapter 7. Alternatively, use of malic-acid-degrading strains of S. cerevisiae can achieve partial deacidification.

Acidification

If wines are too low in acidity, or possess an undesirably high pH, tartaric acid may be added. As an acidulent, tartaric acid has several distinct advantages. These include its fresh crisp taste, high microbial stability, and a dissociation constant (Ka) that allows it to markedly reduce pH. The main disadvantage of tartaric acid addition is its cost, especially when added to wines high in potassium content. Crystal formation results in most of the tartaric acid being lost due to precipitation. The addition of citric acid avoids these problems and can assist in preventing ferric casse, via its chelating action. Nevertheless, the ease with which citric acid is metabolized by many microbes means that it is microbially unstable. Alternatively, ion exchange may be used to lower pH by exchanging H+ for the Ca2+ or K+ of tartrate and malate salts.

Sweetening

In the past, stable naturally sweet wines were rare. Most of the sweet wines of antiquity probably contained boiled-down must or honey – crystalline sugar becoming common in the second half of the nineteenth century. Stabilization by adding distilled alcohol, as in port and madeira, is a comparatively recent innovation. The stable, naturally sweet table wines of the past few centuries seem to have been produced from highly botrytized grapes (see Chapter 9). In contrast, present-day technology can produce a wide range of sweet wines, without recourse to botrytization, baking, or fortification.

Wines may be sweetened with sucrose, for example, sparkling wines. However, most still wines with a sweet character obtain this attribute from the addition of partially fermented or unfermented grape juice, termed sweet reserve (süssreserve). The base wine is typically fermented dry and sweetened just before bottling. To avoid microbial spoilage, both the wine and sweet reserve are sterilized by filtration or pasteurization; the blend being bottled under aseptic conditions, employing sterile bottles and corks. Regardless, peace of mind demands that sulfur dioxide and sorbic acid be added to protect against in-bottle yeast and bacterial spoilage.

Various techniques are used in preparing and preserving sweet reserve. One procedure involves separating a small portion of the juice as the sweet reserve. Thus, it possesses the same varietal, vintage, and geographic origin as the wine it sweetens. If the sweet reserve is partially fermented, yeast activity is terminated prematurely by chilling, filtration, and centrifugation, or by trapping the carbon dioxide released during fermentation. If the sweet reserve is stored as unfermented juice, microbial activity is inhibited/restricted by cooling to−2°C after clarification, pasteurizing, applying CO2 pressure, or sulfiting to above 100 ppm of free SO2. In the last instance, desulfiting is achieved by flash heating or sparging with nitrogen gas before use. Complete desulfiting is not required (or possible). What is left can be calculated into what is required in the finished wine at bottling. If desired, juice can also be concentrated by reverse osmosis or cryoextraction. Heat and vacuum concentration are additional possibilities, but are likely to result in greater flavor modification and fragrance loss.

Dealcoholization

In the past few decades, an increasing market for low-alcohol and dealcoholized wines has developed. Conversely, delayed harvesting to increase flavor content has resulted in wines with high alcohol content. Although a small portion of this latter tendency may be due to global warming, most of it appears to be intentional (Alston et al., 2011) – despite the wines often being criticized as unbalanced and ‘hot.’ Interestingly, Meillon et al. (2010) found unmodified control wines were preferred to their partially (1.5 and 3%) dealcoholized versions. The alcohol contents of the control Chardonnay, Sauvignon blanc, Merlot, and Syrah wines were 14.2, 13.6, 13.4, and 12.7, respectively. Only less experienced consumers tended to prefer the partially dealcoholized wines. Reconstituting the most dealcoholized versions to their original alcohol content did not fully compensate for aspects lost during reverse osmosis dealcoholization.

Previously, dealcoholization involved heat-induced alcohol evaporation. Although successful, it generated detectable baked or cooked odors, and drove off important flavorants. Correspondingly, it was appropriate only for the production of inexpensive, low-alcohol wines, for an uncritical niche market. With the advent of vacuum distillation, the temperature required could be reduced, avoiding heat-generated flavor distortion. Despite this, it still had the problem that many important volatiles escaped with the alcohol. Although some of these could be retrieved and added back to the wine, the final product still lacked its original character.

Alternative procedures include strip-column distillation, dialysis, pervaporation, spinning cone column, and stripping with carbon dioxide (see Wollan, 2010b). Strip-column distillation can lower ethanol contents down to 0.9 g ethanol/liter (Duerr and Cuénat, 1988; Ireton, 1990). Dialysis can have similar effects, with apparently little loss in flavor (Wucherpfennig et al., 1986). Pervaporation selectively removes ethanol, permitting the rest of the permeate to be added back to the wine (Takács et al., 2007). The spinning cone column (Rieger, 1994) and volatilization with carbon dioxide (Antonelli et al., 1996; Scott and Cooke, 1995) both appear to have the advantages of speed and minimal flavor disruption. Nevertheless, the most widely used dealcoholization techniques appear to be vacuum distillation and reverse osmosis, despite their potential for removal of fruity aromatics and accentuating unpleasant odors (Fischer and Berger, 1996). Until recently, these procedures required expensive installations and extensive technical skill. Thus, their application was limited to very large wineries, where the cost–benefit return could justify their purchase. Currently, though, specialized firms offer the service on a contract basis. In addition, affordable bench top units are becoming available, which are appropriate for boutique wineries desiring slight alcohol reduction.

When overly alcoholic wines are treated to bring their alcohol contents down to traditional values, measurable losses in aromatic have generally been relatively minor. Because alcohol content influences wine flavor and balance, alcohol adjustment has the potential to provide the winemaker with an opportunity (albeit for a price) to tweak a wine’s sensory characteristics.

As noted in Chapter 7, another solution has been described by Kontoudakis et al. (2011). A portion of the crop is picked unripe, fermented, and treated with bentonite and charcoal to produce a flavorless, low-alcohol acidic wine. Its subsequent addition to wine made from mature grapes decreases the blended wine’s alcohol content while compensating for reduced acidity. The resultant wine possesses a more traditional alcohol content, while the acidity enhances color intensity and freshness, apparently without negatively affecting flagrance.

Simpler still is harvesting earlier, at a °Brix that will achieve a lower alcohol content. Recent studies in Australia have shown that consumers preferred Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz wines in the 13.5% alcohol range (Anonymous, 2011). This was achieved with grapes picked earlier than is currently standard.

Where the addition of water is permissible to produce low-alcohol beverages, dilution is clearly the simplest and least expensive dealcoholization technique. Flavor enhancement, as with wine coolers, can offset flavor dilution.

Flavor Enhancement

Many grape flavorants, notably terpenes, norisoprenoids and volatile phenols, are bound in nonvolatile glycosidic complexes. Consequently, releasing this potential has drawn considerable attention. Glycosidic bonds may be broken by either acidic or enzymic hydrolysis. Because acid-induced hydrolysis is slow, heating the wine to increase the reaction rate has been investigated (Leino et al., 1993). Although successful, it tends to increase the production of methyl disulfide, accentuate terpene oxidation, and promote the hydrolysis of fruit esters. These features diminish the floral character of the wine, but enhance oaky, honey, and smoky aspects – attributes typically associated with bottle-aged wine.

Because of the flavor distortion associated with heat-accentuated acidic hydrolysis, enzymic hydrolysis has received most of the attention. Of these, β-glycosidase preparations have been extensively studied. Because flavorants are often bound to a variety of sugars, not just glucose, preparations with some α-arabinosidase, α-rhanmosidase, β-xylanosidase, and β-apiosidase activities are preferred. Commercial enzyme preparations are usually derived from filamentous fungi. Their enzymes are relatively insensitive to the acidic conditions typical of wine, unlike those produced by grapes or yeasts.

When employed, the enzymes are added at the end of fermentation – with glucose in the juice/must acting as an inhibitor. In addition, enzymic action can be quickly terminated, as desired, by adding bentonite; it absorbs and removes the enzymes by precipitation. More efficient (but expensive) regulation can be achieved with immobilization of the enzymes in a column through which the wine is passed (Caldini et al., 1994).

As yet, commercial sources of enzymes capable of releasing varietally significant thiols from their cysteinylated and glutathionylated complexes are unavailable.

Sur lies Maturation

Sur lies (on the lees) maturation is an old procedure enjoying considerable renewed interest and application (Dubourdieu et al., 2000). It has been used traditionally with Burgundian and some Loire white wines for decades, if not centuries. It is now employed fairly extensively worldwide, and occasionally with red wines. In red wines, it is credited with diminished astringency and an enhanced perception of sweetness (Marchal et al., 2011). Nonetheless, it is also associated with reduced color intensity (Rodríguez et al., 2005).

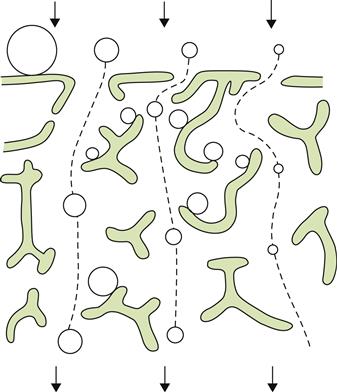

Sur lies maturation involves leaving the wine in contact with the lees at the end of fermentation. The duration can range from 3 to 6 months. This usually takes place in the same barrel in which fermentation occurred. The large surface area/volume ratio of small cooperage, and periodic stirring (bâttonage), favors the diffusion of nutrients, mannoproteins, and flavorants from yeasts into the wine (Fig. 8.3).

) tank aged on light lees; (

) tank aged on light lees; ( ) barrel aged on light lees; (

) barrel aged on light lees; ( ) barrel aged on fermentation lees; (

) barrel aged on fermentation lees; ( ) barrel aged on fermentation lees periodically resuspended. (From Llaubères et al., 1987. Copyright 1987, American Chemical Society, reproduced by permission.)

) barrel aged on fermentation lees periodically resuspended. (From Llaubères et al., 1987. Copyright 1987, American Chemical Society, reproduced by permission.)The effects associated with sur lies maturation occur to some degree in all wines, except when they are racked early and frequently. Nonetheless, they are accentuated with the extended lees contact associated with sur lies maturation.

During maturation, dead and dying yeast cells begin to autolyse. This involves a series of stages. The first two stages, identified by Charpentier and Feuillat (1993), relate to cell-membrane integrity and hydrolytic enzyme activation. The last three stages involve cytoplasmic disintegration, degradation, and increased cell-wall porosity. Although occurring slowly under cool storage conditions, and within the pH range of wine, autolysis releases many cellular constituents (Charpentier, 2000). Lees autolysis also favors the degradation of grape-derived arabinans and arabinogalactan-proteins. These tend to characterize red wines more than white wines, due to the former’s prolonged contact with grape skins (Doco et al., 2003).

The release of volatile yeast metabolites, such as ethyl octanoate and ethyl decanoate, can add a fruity element to the wine, whereas enzymatic reduction diminishes the sensory impact of carbonyl compounds, such as diacetyl. They can also activate the release of aromatic compounds from their precursors (Loscos et al., 2009). Lees may also reduce the sensory defect generated by 4-ethylphenols (Chassagne et al., 2005; Loscos et al., 2009), and the synthesis of sotolon (possessing a curry-like odor) during bottle aging (Lavigne et al., 2008).

Susceptibility to oxidative browning may decrease, due to the release of various amino acids (increasing the supply of oxidizable substrates). Although yeast hydrolytic enzymes can liberate glycosidically bound flavorants (Zoecklein et al., 1997), they may also degrade other grape aromatics. However, the most significant influence of sur lies maturation appears to result from the liberation of mannoprotein cell-wall constituents.

Mannoproteins have a wide range of effects (Caridi, 2006). These glycoproteins appear to have a protective effect on the monomeric anthocyanin content (Palomero et al., 2007). They also soften the taste of red wines, by complexing with and precipitating grape- or oak-derived tannins (Vidal, S. et al., 2004). Mannoproteins also diminish the likelihood of phenolic pinking in white wines (Dubourdieu, 1995). The latter feature is linked with the release of a hydrolytic breakdown product of yeast invertase (Dubourdieu and Moine, 1998a). In addition, mannoproteins favor the early completion of malolactic fermentation (Guilloux-Benatier et al., 1995), and minimize haze production from heat-unstable proteins (Dupin et al., 2000a). Improved protein stability is especially valuable in reducing the need for bentonite fining. To this end, Gonzalez-Ramos et al. (2009) have developed yeast strains with increased mannoprotein release; it apparently can reduce the need for bentonite fining by some 20–40%.

Mannoproteins also promote tartrate stability (Dubourdieu and Moine, 1998b). This clearly benefits wines consumed early, but the long-term benefits of tartrate stability are less clear. For example, breakdown of the soluble complexes may eventually lead to in- bottle tartrate deposition, as well as protein-haze formation. At least, delayed tartrate crystallization is of less concern, because the wine is most likely to have been consumed before the process commences. Aficionados usually know what the crystals are, and are not concerned.

In addition, mannoproteins reduce adsorption of aromatic compounds, such as fruit esters by oak cooperage (Ramirez-Ramirez et al., 2004). They can also favor the volatilization of some compounds, but bind others (Lubbers et al., 1994; Chalier et al., 2007). Particularly important in this regard may be a reduction in the volatility of thiols such as ethanethiol and methanethiol.

To avoid the development of a low redox potential in the lees, and the consequential production of reduced-sulfur off-odors, the wine is periodically stirred (bâttonage). This may occur on a weekly to monthly basis. It also favors the oxidization of hydrogen sulfide. However, in large cooperage, hydrostatic pressure exerted on the lees appears to promote the production of hydrogen sulfide and several reduced organic sulfur compounds (Lavigne, 1995). Anaerobic conditions in the lees also favor their production. Thus, sur lies maturation takes place almost exclusively in small cooperage. Under these conditions, lees appear to metabolize or absorb mercaptans; they escape or are oxidized during racking.

Nevertheless, sur lies maturation has been noted to increase susceptibility to the development of a sunstruck odor (goût de lumière) (La Follette et al., 1993). In addition, the release of significant amounts of glucose during autolysis (Guilloux-Benatier et al., 2001) increases the risks of microbial spoilage. Thus, it is particularly crucial that the cooperage be properly cleaned and sanitized to avoid contamination with yeasts such as Brettanomyces. When conducted slowly, bâttonage-induced oxygen exposure appears to avoid significant oxygen accumulation in the wine (Castellari et al., 2004). Thus, activation of acetic acid bacteria is minimized, when combined with cool storage temperatures. This can avoid the need for adding sulfur dioxide. This could retard or prevent malolactic fermentation that may be desired to occur simultaneously with sur lies maturation.

A distinctive form of sur lies maturation, though not so called, occurs during sparkling wine production. During the long, yeast-contact period, following the second, in-bottle fermentation, autolysis donates the toasty bouquet that characterizes fine sparkling wines. Part of this may be associated with the release of thiols, such as phenylmethanethiol and ethyl 3-sulfanylpropionate (Tominaga et al., 2003). The release of mannoproteins also stabilizes dissolved carbon dioxide, promoting the formation of long-lasting chains of bubbles. In addition, mannoproteins slow the release of aromatic compounds from the wine (Dufour and Bayonove, 1999), as well as bind potentially undesirable thiols (Tominaga et al., 2003). Another special example of a sur lies maturation-type process involves the solera aging of fino sherries.

Color Adjustment

The bevy of studies on micro-oxygenation, in relation to red wine production (see below), is one expression of the interest in color adjustment. The slow or periodic addition of oxygen favors the polymerization of anthocyanins with tannins (proanthocyanidins). Boulton et al. (1996) suggest that red wines can benefit from up to 60 mL O2 per liter (~10 periodic saturations), but show obvious deterioration with more than 25 saturations. Nonetheless, micro-oxygenation must be carefully monitored to avoid risks of activating dormant acetic acid bacteria, aggravating potential spoilage by Brettanomyces, and inducing the precipitation (loss) of polymeric pigments.

Another technique relates to the effect of temperature on enhancing polymerization. Correspondingly, Somers and Pocock (1990) recommended heating the wine during maturation as an alternative to aeration, to encourage early color stabilization.

In other instances, with varieties that either possess low tannin contents or tannins that are not easily extracted, adding enologic tannins may improve color depth and stability. Currently, the results of such investigations have been ambivalent, being encouraging with some cultivars, but not with others.

More frequently, though, color adjustment after fermentation refers to its reduction, especially with white wines. All wines can be partially or completely decolored by ultrafiltration. Depending on the permeability characteristics of the membrane, ultrafiltration retains macromolecules above a specific size. With membranes of lower cut-off values (~500 Da), ultrafiltration can also remove phenolic pinking. The use of filters, with even lower cut-off values, can produce blush or white wines from red or rosé wines. The major factor limiting the more widespread use of ultrafiltration is its potential for removing important flavorants along with macromolecules.

Adding PVPP (polyvinylpolypyrrolidone) is another procedure used to remove brown or pink pigments (Lamuela-Raventós et al., 2001). By binding tannins into large macromolecular complexes, PVPP facilitates their removal by filtration or centrifugation. Several white wines, such as Sauvignon blanc, have a tendency to turn pinkish within days of oxygen exposure (Simpson, 1977), especially those assiduously protected from oxidation during and after crushing. Considerable oxygen may be required for development of full pink expression (Singleton et al., 1979). Pinking is thought to occur when flavan-3,4-diols (leucoanthocyanins) slowly dehydrate to flavenes under reducing conditions. These can quickly oxidize to their corresponding colored flavylium-forms on exposure to oxygen. The use of moderate levels of sulfur dioxide helps to limit pinking (Simpson, 1977). Anecdotally, erythorbic acid, a diastereoisomer of ascorbic acid, has been reported to be more effective than ascorbic acid in limiting pinking in bottled white wine (Clark et al., 2010).

Other means of color removal involve the addition of casein or special preparations of activated carbon. With activated carbon, the simultaneous removal of aromatic compounds and the occasional donation of off-odors have limited its use. The addition of yeast hulls has also been studied as a means of removing brownish pigments from white wines (Razmkhab et al., 2002).

Blending

Blending is a standard feature in winemaking. It can vary from the selective combination of free- and press-run juice or wine; to wine made from different lots of grapes or juice derived from a single or several adjacent vineyards, growing the same or different cultivars; to wine made from grapes grown in different regions or countries. When blending wine, it is important to establish the physicochemical and sensory attributes of each to better predict the best potential blends.

Of blended wines, those made by combining wines from different varieties is probably the most well known to consumers. In Bordeaux, both red and white wines are rarely made from a single variety. For red wines, more than five are permitted, and for whites, up to three are authorized. In Chianti, up to five varieties may be included, and in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, 13 different cultivars may be involved. Even more may be blended in the production of porto.

In the past, varietal combination frequently occurred at harvest. Cultivars were often dispersed throughout the vineyard and harvested simultaneously, without separation as to variety. Although this is rare today, it may still occur in some regions. Where varieties are fermented together (cofermentation), the musts are typically combined after crushing. Usually, only the juice or must from either white or red cultivars is blended, though sometimes this is blended from white and red cultivars. Examples of the latter are Chianti and some Côte Rôtie wines. The addition of white juice to red must has often been explained as a means of ‘softening’ the wine. While possibly valid, it may be more valuable in color enhancement (Gigliotti et al., 1985). If the red wine is low in copigment factors, for which the white variety has an abundant supply, the addition of some juice from the white variety can enhance coloration. The addition of white juice could also assist in the formation of pigment polymers, which are important in long-term color stability. Where this is valuable, but dilution with the juice undesired, only the skins may be employed (depending on the phenolic components needed). It is more common, though, to ferment the must of individual cultivars separately, followed by blending of their wines. This has the advantage of permitting selective blending, based on the attributes of the specific wines. Separating grapes into lots at harvest also permits the distinctive qualities of the fruit from different sites or maturity grades to be realized. These can be blended later, if desired.

The skill and experience of the blender are especially important in the production of fortified and sparkling wines. Without blending, the creation and maintenance of house-styles would be impossible. The production of proprietary table wines also is largely dependent on the judicious combination of diverse wines. Consistency of character typically is more important than the vintage, variety, or vineyard origin. The skill of the blender is often amazing, given the number of wines potentially involved. It may also help that most consumers are ill-adept at remembering subtle sensory differences.

Blending also is used in the production of many premium table wines. In this case, however, the wines typically come from the same geographic region, and are often from a single vineyard (or holding) and vintage. Limitations on blending are usually precisely articulated in Appellation Control laws – the more renowned the region, the more restrictive the legislation.

There is little to guide blenders other than past experience. Blending to achieve specific attributes (relative to taste or some legal requirements) is usually comparatively easy. Simple calculations based on the relative composition, and the proportion of the wines blended, may approximate the desired result. However, many aspects are so complex and nonlinear that major discrepancies between physicochemical prediction and sensory perception are common. Evident examples relate to acidity, color, and flavor. To date, few studies have directly investigated the scientific basis of blending. Those that have have focused on methods predicting color, based on pigmentation of the base wines. Color is particularly significant due to its strong influence on quality perception, at least to critics, connoisseurs and trained tasters.

Blending diagrams may be developed using colorimeter readings. The diagrams are founded on the reflectance of the wines in the red, green, and blue portions of the visible spectrum. From these data, the lots required to achieve a desired color can be estimated. Pérez-Magariño and González-San José (2002) have proposed simple absorbance measurements for wineries without the equipment or software necessary to make the complex measurements normally involved.

Because of the limitations of individual blenders, and the nonlinear manner in which many sensory attributes combine, computer-aided systems have been proposed to facilitate blending (Datta and Nakai, 1992; Ferrier and Block, 2001). If nothing else, they may assist in helping us understand the origins of how various attributes interact.

Despite our lack of understanding into the subtleties of blending, on a practical level it is clear that some of the major advantages associated with blending are improved flavor, balance, and complexity. These properties were even known to the ancient Greeks; for example, Theophrastus (371–287 B.C.) notes in his Concerning Odours (ΠEPI OΣMΩN 11.2):

… for instance, if wine of Heraclea be mixed with wine of Erythrae, since the latter contributes its mildness and the former its fragrance; for the effect is that they simultaneously destroy one another’s inferior qualities through the mildness of the one and the fragrance of the other.

Loeb edition

In contrast, the Roman author, Columella (De Re Rustica 3.21.6–10) was opposed to blending, at least before vinification. He considered the qualities of the better wine to be worsened by the inferior one, and that the blended wine would not age well. However, subsequent comments indicate that part of this negative opinion is based on problems associated with mixed planting (e.g., the inability to prune or grow cultivar vines relative to their unique requirements).

In a classic study by Singleton and Ough (1962), similar pairs of wines, ranked comparably, but recognizably distinct, were reassessed along with their 50:50 blend. In no case was the blended wine ranked more poorly than the lower ranked of the base wines. More significantly, about 20% of the blends were ranked higher than either of the component wines (Fig. 8.4). Because the relationship between perceived intensity and flavorant concentration is nonlinear, blending does not necessarily diminish the desirable sensory characteristics of the individual wines. The reverse is more common.

) compared with their 50:50 blend (×), indicating the value of a complex flavor derived from blending. (Based on data from Singleton and Ough, 1962, from Singleton, 1990, reproduced by permission.)

) compared with their 50:50 blend (×), indicating the value of a complex flavor derived from blending. (Based on data from Singleton and Ough, 1962, from Singleton, 1990, reproduced by permission.)Although the origin of the improved sensory quality of blended wines is unknown, it may relate to the increased flavor subtlety and complexity. This has been used to commercial advantage when wines of intense flavor have been blended with large volumes of neutral wine. The blend still tends to express the characteristics of the fragrant component. In addition, the negative perception of some off-odors often diminishes with dilution, as they approach their threshold of detection (see Chapter 11).

When blending should take place depends largely on the type and style of wine involved. In sherry production, for example, fractional blending occurs periodically throughout maturation. With sparkling wines, blending (development of the cuvée) occurs in the spring following harvest. At this point, the unique features of the base wines are apparent. Blending of red table wines also typically occurs in the spring following fermentation.

Important in the deliberation is not only the proportional amount of each wine, but also whether wine derived from later pressings should be included. Wines from poor vintages customarily benefit from the addition of extra press wine than wines from better vintages. Later press fractions contain a higher proportion of pigment and tannins than the free-run or first pressing. The addition of pressings can also provide extra body and color to white wines. After blending, the wine is often aged for several weeks, months, or years before bottling. This is intended to ‘marry’ their flavors, as well as allow a new equilibrium to develop relative to acidity, their salts, protein, and pigment stabilization.

Wines may not be blended for a number of reasons. Wines produced from grapes of especially high quality are usually kept and bottled separately, to retain their distinctive attributes. For wines produced from famous vineyards, blending with wine from other sites, regardless of quality, would prohibit the owner from using the site name. This would significantly reduce the market value of the wine. With famous names, origin can be more important to sales than inherent quality.

Stabilization and Clarification

Stabilization and clarification involve procedures designed to produce a brilliantly clear wine with no flavor faults. Because the procedures can themselves create problems, it is essential that they be used judiciously, and only to the degree necessary.

Stabilization

Tartrate and Other Crystalline Salts

Tartrate stabilization is one of the facets of wine technology most influenced by consumer perception. The presence of even a few tartrate crystals can too easily be misinterpreted by neophytes. As a consequence, considerable effort is expended to avoid the formation of crystalline deposits in bottled wine (they have too often been misinterpreted as glass slivers). Stabilization is normally achieved by enhancing crystallization, followed by removal. In wines likely to be consumed shortly after bottling, a simpler delaying of crystallization can be used.

Potassium Bitartrate Instability

Juice is typically supersaturated with potassium bitartrate at crushing. As the alcohol content rises during fermentation, the solubility of the bitartrate decreases. This induces the slow precipitation of potassium bitartrate (cream of tartar). Given sufficient time, the salt crystals precipitate spontaneously. In northern regions, low cellar temperatures may induce adequately rapid precipitation. This is seldom satisfactory in warmer areas. Early bottling aggravates the problem. Where spontaneous precipitation is inadequate, refrigeration typically achieves rapid and satisfactory bitartrate stability. For a comparison of two stabilization techniques, from an environment impact perspective, see Bories et al. (2011).

Because the rate of bitartrate crystallization is directly dependent on the degree of supersaturation, wines that are only mildly unstable may be insufficiently stabilized by cold treatment. In addition, protective colloids may retard crystallization (Lubbers et al., 1993). Typically, protective colloids have been viewed negatively, as their precipitation after bottling releases tartrates that could subsequently crystallize. Although this may be true for most protective colloids, some mannoproteins appear sufficiently stable to donate adequate tartrate stability in bottled wine (Dubourdieu and Moine, 1998b). Different types of mannoproteins are released early during fermentation, and especially later during maturation as yeast cells in the lees autolyse. Alternatively, the addition of yeast cell-wall enzymic digest (yeast hulls) can promote tartrate stability, without cold or other stabilization treatments.

Potassium bitartrate exists in a dynamic equilibrium between ionized and salt states, as well as being associated with protective colloids. Under supersaturated conditions, salt crystals begin to form, eventually reaching a critical mass that provokes precipitation. Crystallization continues until an equilibrium develops. If sufficient crystallization and removal occur before bottling, bitartrate stability is achieved. Because chilling decreases solubility (provoking crystallization), bitartrate stability is of particular concern where bottled wines are likely to experience cold temperatures for any significant period during transport or storage.

In red wines, crystallization during maturation is often associated with yeast cells. They may constitute about 20% of crystal weight (Vernhet et al., 1999b). This compares with about 2% in white wines (Vernhet et al., 1999a). Potassium hydrogen tartrate crystals may also associate with other materials, for example, small amounts of phenolic compounds (notably anthocyanins and tannins in red wines), and polysaccharides, such as rhamnogalacturonans and mannoproteins.

Thus, although chilling tends to establish bitartrate stability, charged particles can interfere with crystal initiation and growth. For example, positively charged bitartrate crystals are attracted to negatively charged colloids, blocking growth. The charge on the crystals is created by the tendency for more potassium than bitartrate ions to associate with crystals early in growth (Rodriguez-Clemente and Correa-Gorospe, 1988). Crystal growth may also be delayed by the binding of bitartrate ions to positively charged proteins. This reduces the amount of free bitartrate and, thereby, the rate of crystallization. Because both bitartrate and potassium ions may bind with tannins, crystallization tends to be delayed more in red than in white wines. The binding of potassium with sulfites is another source of delayed bitartrate stabilization.

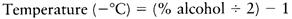

For cold stabilization, table wines are routinely chilled to near the wine’s freezing point. Five days is usually sufficient at−5.5°C, but 2 weeks may be necessary at−3.9°C. Fortified wines are customarily chilled to between−7.2 and−9.4°C, depending on their alcoholic strength. The stabilization temperature can be estimated using the empirical formula established by Perin (1977):

Adding potassium bitartrate crystals is often used to stimulate crystal growth. Crystal initiation (nucleation) is the principal obstacle to crystal growth. Another technique employing the same principle involves filters incorporating seed crystals. The chilled wine is agitated and then passed through the filter. Crystal growth is encouraged by the dense concentration of seed nuclei in the filter. The filter acts as a support medium for the crystal nuclei.

At the end of chilling, the wine is either filtered or centrifuged to remove the crystals. Crystal removal must be performed before the wine warms to ambient temperatures to prevent resolubilization.

Because of the expense of refrigeration, various procedures have been developed to determine the need for cold stabilization. Regrettably, none appears to be fully adequate. Potassium conductivity, although valuable, is too complex for regular use in most wineries. Thus, empirical freeze tests are the most common. For details on the various tests, the reader is directed to Goswell (1981) and Zoecklein et al. (1995). Despite the expense of cold stabilization, a recent comparison with several alternative techniques actually found the former to be the most cost-effective (Low et al., 2008).

Reverse osmosis is an alternative stabilization technique. By removing water, the concentration of bitartrate is increased, favoring crystallization and precipitation. After crystal removal, the water is added back.

Electrodialysis is another membrane technique occasionally used in bitartrate stabilization (Soares et al., 2009; Wollan, 2010a). Electrically charged membranes selectively prevent the passage of ions of the opposite charge. Passing wine between oppositely charged membranes can remove both anions and cations. In practice, though, potassium ions are more rapidly removed than tartrate ions. This not only limits crystallization, which requires both ions, but tends to lower the pH. Reducing the potassium content by about 10% seems to be effective in achieving adequate bitartrate stability. The procedure has the benefit of avoiding the simultaneous precipitation of polysaccharides and polyphenols, associated with cooling the wine to near freezing. It also reduces the energy costs associated with cooling, and wine loss with the crystals that form.

Another technique particularly useful for wines with high potassium contents is ion exchange. Passing the wine through a column packed with sodium-containing resin exchanges sodium for potassium. Sodium bitartrate is more soluble than its potassium equivalent, and is therefore much less likely to precipitate. Although effective, ion exchange is not the method of choice. Not only is it prohibited in certain jurisdictions, for example the EU, but it also increases the wine’s sodium content. The high potassium/low sodium content of wine is one of its positive health benefits.

If the wine is expected to be consumed shortly after bottling, treatment with metatartaric acid is an inexpensive alternative. Metatartaric acid is produced by the formation of ester bonds between the hydroxyl and acid groups of tartaric acid. The polymer is generated during prolonged heating of tartaric acid at 170°C. When added to wine, metatartaric acid restricts potassium bitartrate crystallization. It also interferes with the growth of calcium tartrate crystals. Because metatartaric acid slowly hydrolyzes back to tartaric acid, its effect is only temporary. At storage temperatures between 12 and 18°C it may be effective for about 1 year. Because hydrolysis is temperature-dependent, the stabilizing action of metatartaric acid quickly disappears above 20°C. If this treatment is used, metatartaric acid is added just before bottling. Other agents that can retard if not totally prevent crystallization include gum arabic and carboxymethylcellulose. They do not appear to modify the wines sensory attributes, possess no health risks, and remain active significantly longer than metatartaric acid (Bosso et al., 2010; Gerbaud et al., 2010).

Calcium Tartrate Instability

Instability caused by calcium tartrate is more difficult to control than its potassium counterpart. Fortunately, it is less common. Calcium-induced problems usually arise from the excessive use of calcium carbonate in deacidification, but can also arise from using cement fermentors, filter pads, and fining agents.

Several organic acids significantly influence calcium tartrate crystallization (McKinnon et al., 1995). For example, malolactic fermentation removes a major inhibitor of crystallization (malic acid) and, thus, promotes earlier calcium tartrate stability. However, for wines consumed shortly after bottling, such as champagnes, retarding crystallization may be preferable. Thus, malic acid may be added to sparkling wine with the dosage. Because grapes, used in making the base wine for sparkling wines, are pressed whole, they contain little polygalacturonic acid (a pectin breakdown product). Polygalacturonic acid is a potent retardant of calcium tartrate crystallization.

Calcium tartrate stabilization is more complex because precipitation is not effectively activated by chilling. Despite crystal growth and precipitation occurring optimally between 5 and 10°C, it can still take months for spontaneous stability to develop. Seeding with calcium tartrate crystals, while deacidifying with calcium carbonate, greatly enhances precipitation (Fig. 8.5). Because the formation of crystal nuclei requires more free energy than crystal growth, seeding circumvents the major limiting factor in stability development. A racemic mixture of calcium tartrate seed nuclei, containing both L and D isomers, is preferred. The racemic mixture is about one-eighth as soluble as the naturally occurring L-tartrate salt. This may result from the more favorable (stable) packing of both isomers within crystals (Brock et al., 1991). The slow conversion of the L form to the D form is a major factor provoking crystallization in bottled wine. Because clarification removes ‘seed’ crystals that promote crystallization, wine filtration should be delayed until calcium tartrate stability is no longer considered a hazard. Protective colloids such as soluble proteins and tannins can restrict crystal nucleation, but they do not inhibit crystal growth (Postel, 1983).

If protective colloids are a problem, agar may be added to the wine. Agar, an algal polysaccharide, tends to neutralize the charges on protective colloids. This eliminates their protective property, allowing colloid-tartrate complexes to dissociate. This favors both colloid precipitation and calcium tartrate crystallization.

Alternatively, calcium content may be directly reduced through ion exchange. Because of the efficiency of ion removal, typically only part of the wine needs to be treated. This proportion is then mixed back into the main volume. Treating only a small portion of the wine minimizes the flavor loss often associated with ion exchange.

Other treatments that show promise are the addition of stable colloids, such as pectic and alginic acids. They restrict crystallization and keep calcium tartrate in solution (Wucherpfennig et al., 1984).

Other Calcium Salt Instabilities

Occasionally, crystals of calcium oxalate form in wine. The development occurs late, commonly after bottling. The redox potential of most young wines stabilizes the complex formed between oxalic acid and metal ions, such as iron. However, as the redox potential rises during aging, ferrous oxalate changes into the unstable ferric form. After dissociation, oxalic acid may bond with calcium, forming calcium oxalate crystals.

Oxalic acid is commonly derived from grape must, but small amounts may originate from iron-induced structural changes in tartaric acid. Oxalic acid can be removed by blue fining early in maturation (Amerine et al., 1980), but avoiding the development of high calcium levels in the wine is preferable.

Other potentially troublesome sources of crystallization are saccharic and mucic acids. Both are produced by the pathogen Botrytis cinerea. They may form insoluble calcium salts. The addition of calcium carbonate for bitartrate stability often induces their crystallization, precipitation, and separation before bottling.

Protein Stabilization

Protein-induced haze is another significant concern for winemakers, potentially causing economic loss. Protein instability is primarily a concern with white wine, but occasionally can affect rosé wines. It is seldom a problem with red wines, presumably due to the precipitation of the causal proteins with tannins, and removal before bottling.

Haze (i.e., turbidity/clouding) results from the clumping of dissolved proteins into light-dispersing, colloidal particles. Heat exposure during transport accelerates colloid formation (Dufrechou et al., 2010), but it can develop at standard temperatures. This results as soluble proteins denature in the presence of polyphenolics, metals, and/or sulfates (Pocock et al., 2007). Denaturation appears to involve protein unfolding, followed by interaction with other constituents to form colloidal-sized aggregates. Nonetheless, a complete understanding of the causes of haze development remains elusive (Batista et al., 2009), possibly due to variation in secondary factors involved in different wines.

The majority of proteins suspended in wine have an isoelectric point (pI) above the pH range of wine. The isoelectric point is the pH at which a protein is electrically neutral. Consequently, most soluble proteins in wine possess a net positive charge, generated by the ionization of amino groups. This charge slows clumping, while Brownian movement and hydration (coating with water) delay settling. In contrast, denaturation favors coalescing, producing clouding.

The proteins primarily involved in haze production have only recently been identified. The situation was confusing because protein instability was poorly correlated with protein content. The principal proteins involved are pathogenesis-related (PR) protein (Waters et al., 1996b,c; Dambrouck et al., 2003), including thaumatin-like proteins and chitinases. Other proteins may also be present in the precipitate, for example β-(1-3)-glucanase and a ripening-related protein (grip22) precursor (Esteruelas et al., 2009a). In reconstruction experiments, chitinase was the most active protein provoking haze formation (Gazzola et al., 2012).

Pathogenesis-related proteins often constitute the majority of the small soluble proteins found in pressed juice and wine. Their occurrence typically ranges from 50 to 100 mg/liter, but can vary from 200 to 250 mg/liter in Muscat of Alexandria and Sauvignon blanc, to 62 mg/liter and 31 mg/liter for Pinot noir and Shiraz, respectively (Pocock et al., 2000). Mechanical harvesting, associated with prolonged transport to (or storage at) the winery, can activate increased production. The result can be a doubling of the amount of bentonite needed for stabilization (from 0.5 to 1.0 g/liter) (Pocock et al., 1998).

As the name pathogenesis-related proteins suggests, their principal role in grapes is to protect maturing fruit from infection. Nonetheless, their production in post-véraison healthy fruit suggests a possible additional developmental role (Tattersall et al., 2001). Despite being the principal causal agents of protein instability in wine, it is their acid stability, resistant to proteolytic action, and their minimal bonding with tannins that create the problem. Their stability permits them to survive through fermentation and maturation, denaturing slowly during prolonged in-bottle aging. It is this slow denaturation that produces the instability that can be so costly.

The proteins involved in protein instability are unrelated to those involved in haze production in beer (Siebert et al., 1996). In beer, proteins possessing a high proline content combine selectively with polyphenolics possessing two- or three-vincinal (adjacent) OH groups (Siebert and Lynn, 1998). Such complexes in wine would precipitate long before bottling.

Additional soluble proteins in wine, such as yeast mannoproteins and grape arabinogalactan–protein complexes may aggravate heat-induced protein haze, even though specific members in both groups can reduce protein-induced haze (Pellerin et al., 1994). Particularly interesting is the action of mannoproteins in reducing the size of haze particles to the threshold of human detection (Waters et al., 1993; Dupin et al., 2000b). Because the active glycoprotein fractions do not appear to be associated with the haze particles, they presumably have their action on secondary factors involved in aggregation (Dupin et al., 2000a). Although commercial mannoprotein preparations are available that limit protein-haze development, use of yeast strains releasing increased amounts of mannoproteins is an alternative solution (Dupin et al., 2000a,b).

A number of procedures have been developed to achieve protein stability. The most common involves the addition of bentonite (Fig. 8.6). It is typically added after fermentation as a fining agent. However, data from Pocock et al. (2011) suggest that two-stage addition (with and after fermentation) is more efficient, both in terms of total amount required and effectiveness.

Because of the abundance of cations associated with bentonite, extensive exchange of ions can occur with ionized protein amino groups. By weakening their association with water, the cations favor protein coalescence and precipitation. Flocculation and precipitation are further enhanced by adsorption onto the negatively charged plates of bentonite. Because of the variable amounts and ionizing potential of the different proteins involved, it is not surprising that the dynamics of their precipitation can vary considerably (Fig. 8.7).

Sodium bentonite is preferred because it separates more readily into individual silicate plates. This generates the largest surface area of any clay and, therefore, the greatest potential for cation exchange and protein adsorption. Regrettably, bentonite generates considerable sediment and associated wine loss. Although much of the wine lost can be recovered by vacuum rotary drum filtration, the oxidation potential associated with the process can reduce its quality. Despite these limitations, bentonite’s additional clarification properties (see below) still make it the preferred fining agent for protein stabilization.

Because haze-inducing proteins can be desorbed from bentonite by increasing the pH, there is interest in developing a continuous flow stabilization system. Bentonite immobilization would not only permit its regeneration, but also dramatically reduce the amount of wine lost with currently practiced batch fining. An alternate procedure being investigated is in-line dosing, and bentonite removal with centrifugation (Muhlack et al., 2006).

Other fining agents, such as tannins, are occasionally used in lieu of bentonite. However, the addition of tannins is often ill-advised. They can leave an off-odor and generate an astringent mouth-feel. Kieselsol, a colloidal suspension of silicon dioxide, has also occasionally been used to remove proteins. Another alternative procedure showing promise is zirconium dioxide (Marangon et al., 2011a). It is supplied enclosed in a metal cage to facilitate its removal at the end of treatment. The addition of carrageenan and pectin before fermentation is another alternative showing promise (Marangon et al., 2012). Ultrafiltration has been investigated as another alternative to bentonite or other types of fining (Hsu et al., 1987). It has the advantage of minimizing wine loss, and the need for a final polishing centrifugation or filtration.

Traditionally, protein stability and treatment need have been estimated empirically by treating wine samples to 80°C for 8 h. However, studies by Pocock and Waters (2006) suggest that 2 h may be fully adequate. In a comparison of various protein stabilization tests, Esteruelas et al. (2009b) recommend exposing samples to 90°C for 1 h in a water bath, followed by cooling to 4°C for 6 h in a refrigerator. Cooling is usually required for the rapid development of haze in treated samples. Its development also depends on the ionic strength and sulfite content of the wine, with thaumatin-like proteins and cutinases responding differently (Marangon et al., 2011b). Haze is either measured subjectively by eye, or objectively with a nephelometer or some other optical density devise. If demonstrated to be unstable, samples are treated and retested to determine whether further treatment is still required.

Polysaccharide Removal and Stability

Pectinaceous and other mucilaginous polysaccharides can cause difficulty with filtration, as well as provoke haze development. Polysaccharides can also act as protective colloids, binding with other suspended materials, slowing or preventing precipitation. For example, negatively charged pectins collect around positively charged grape solids. In addition, multiple hydrogen bonds formed between water and pectins help these complexes remain in suspension. During fermentation, alcohol production tends to disrupt hydration, provoking pectin precipitation.

Where concentration of pectins is high, the must is usually treated with pectinases. These contain a mixture of enzymes, including a pectin lyase. They split the pectin polymer into simpler, noncolloidal, galacturonic acid subunits. In so doing, positively charged areas of the pectin are exposed and can bind to the negatively charged surfaces of other colloids. As these complexes increase in mass, they tend to precipitate, becoming easier to remove during fining.

Other grape-derived polysaccharides, such as arabinans and galactans, have little effect on haze formation or filtration. Nonetheless, their degradation can be beneficial in producing denser lees. This reduces wine loss during racking. Like grape-derived polysaccharides, yeast-derived mannans have no detrimental effects relative to haze production or filtration.

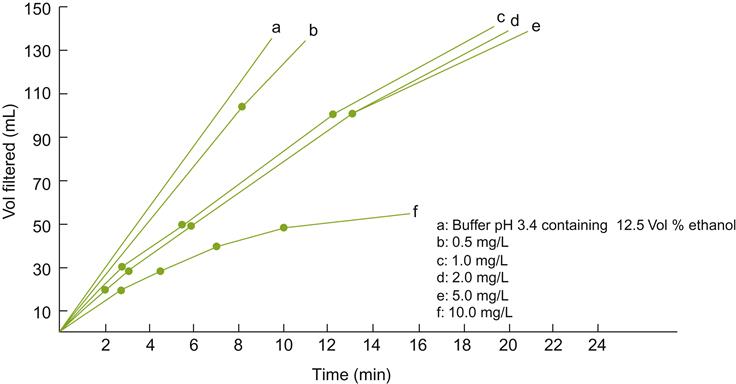

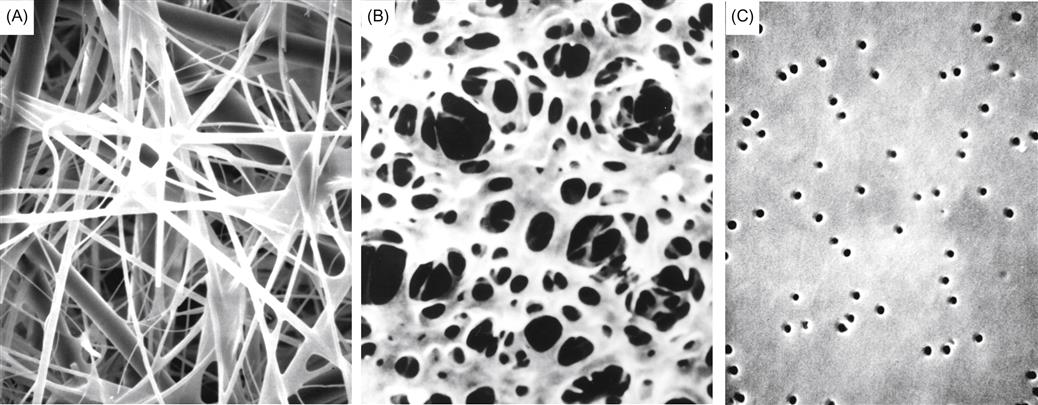

The most vexing group of polysaccharides is the β-glucans. They are produced in, and easily extracted from, botrytized grapes. They can cause serious filtration problems, even at low concentrations (Fig. 8.8). This is especially serious in highly alcoholic wines, in which aggregation is enhanced. A Kieselsol–gelatin mixture is apparently effective in removing the mucilaginous polymers. Alternatively, the wine may be treated with a formulation of β-glucanases (Villettaz et al., 1984). The enzymes hydrolyze the polymers, eliminating both their protective colloidal property and filter-plugging action. To minimize extraction, noble-rotted grapes are manually harvested and slowly pressed without prior crushing.

Tannin Removal and Oxidative Casse (Haziness)

Tannins may be both directly and indirectly involved in haze (casse) formation. After exposure to oxygen, catechins and other phenolics oxidize and may polymerize into brown, light-diffracting colloids, potentially causing oxidative casse. Shortly after crushing, as grape polyphenol oxidases are inactivated, oxidative reactions become slow and nonenzymatic. Depending on the timing and degree of oxidation, tannin oxidation can result in a loss of color intensity, a shift in hue, and an enhancement in long-term color stability. The addition of sulfur dioxide limits oxidation through its antioxidant and antienzymatic properties. However, wine from moldy fruit, contaminated with fungal polyphenol oxidases (laccases), is particularly susceptible to oxidative casse. Because laccases are poorly inactivated by sulfur dioxide, at permissible concentrations, pasteurization may be the only convenient means of protecting moldy juice from oxidative casse. Healthy grapes rarely develop oxidative casse. Because casse usually develops early during maturation and precipitates before bottling, it is seldom involved in in-bottle clouding.

Chilling wine to achieve bitartrate stability may provoke formation of a protein–tannin haze. Filtration before the wine warms removes these protein–tannin complexes before their dissociation, preventing their reformation post-bottling.

Removal of excess proanthocyanins and tannins is normally achieved by adding fining agents such as gelatin, egg albumin, isinglass, or casein. Because most are complex collections of proteins, with different amino acid compositions, or their denatured products, each has somewhat different effects, as do individual commercial versions (e.g., Maury et al., 2001; Cosme et al., 2009). Thus, it is only possible to provide general tendencies here.

These agents take effect through their positively charged sites associating with negatively charged sites on flavonoids. The interaction produces large protein– phenolic complexes. Their formation is a function of the balance between the potential binding sites of both the tannins and proteins. Excess in either tends to diminish binding. Once formed, the complexes may be removed by filtration or centrifugation, if early bottling is desired. Otherwise, adequate spontaneous sedimentation normally occurs during maturation. The removal of excess tannins reduces a major source of astringency, generates a smoother mouth-feel, reduces the likelihood of oxidative casse, and limits the accumulation of sediment following bottling.

In white wines, the addition of PVPP is a particularly effective means of removing flavonoids and their dimers. Ultrafiltration may also be used to remove excess proanthocyanidins and other polyphenolic compounds in white wines. Ultrafiltration is seldom used with red wines, due the simultaneous removal of important flavorants and anthocyanins.

Additional but infrequent sources of phenolic instability include oak chips or shavings, used to give an oaked character (Pocock et al., 1984), and the accidental incorporation of excessive amounts of leaf material in the grape crush (Somers and Ziemelis, 1985). Both can generate in-bottle precipitation, especially if the wine is bottled early. These problems can be avoided by permitting sufficient time for spontaneous precipitation. The instability associated with oak-chip use results from the overextraction of ellagic acid. The phenolic deposit produced consists of a fine precipitate of off-white to fawn-colored ellagic acid crystals. A flavonol haze in white wine, usually associated with excessive leaf material in the crush, is produced by the formation of fine, yellow, quercetin crystals (Somers and Ziemelis, 1985). Its occurrence, if suspected, can be reduced with PVPP (Laborde et al., 2006). An excessive use of sulfur dioxide has also been associated with cases of phenolic haze in red wines.

Many premium-quality red wines develop a tannin-based sediment during prolonged in-bottle aging. This potential source of haziness is typically not viewed as a fault. It develops only if the sediment is resuspended by turbulence generated by injudicious bottle handling or wine pouring. Individuals who customarily consume aged wines know its origin. They often consider sediment a quality indicator (incorrectly assuming that fining is inherently prejudicial to wine quality).

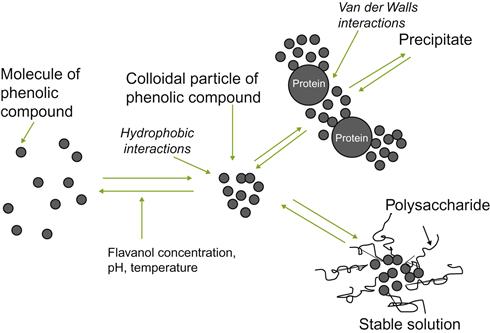

Some of the interactions in wine stabilization are illustrated in Fig. 8.9.

Metal Casse Stabilization

Several metals can form insoluble salts and induce additional forms of haziness. Although occurring much less frequently than in the past (largely due to the replacement of iron, copper, bronze, and brass fitting with stainless steel), metal casse occasionally still causes problems.

The most important metallic ions involved in casse formation are iron (Fe3+ and Fe2+) and copper (Cu2+ and Cu+). They may be derived from grapes, soil contaminants, fungicidal residues, or winery equipment. Most metallic ions so derived are lost during fermentation, by coprecipitation with yeast cells. Troublesome concentrations of metal contaminants usually are associated with pickup after vinification. Corroded stainless steel, improperly soldered joints, unprotected copper or bronze piping, and tap fixtures are the prime sources of any current contamination. Additional sources may be fining and decoloring agents, such as gelatin, isinglass, activated carbon, and cement cooperage.

Ferric (Iron) Casse

Two forms of ferric (iron) casse are known – white and blue (Fig. 8.10). Although uncommon, white casse occasionally develops in white wine. It occurs when soluble ferrous phosphate (FePO4) is oxidized to insoluble ferric phosphate (Fe3(PO4)2). The white haziness may be due solely to ferric phosphate, or to a complex between it and soluble proteins. In red wines, the oxidation of ferrous ions (Fe2+) to the ferric state (Fe3+) can result in the formation of a blue casse. Ferric ions form insoluble particles with anthocyanins and tannins. The oxidation of ferrous to ferric ions usually occurs when the wine is exposed to air. In an unstable wine, sufficient oxygen may be absorbed during bottling to induce clouding.

The development of ferric casse is dependent both on the wine’s metallic content and on its redox potential. Its occurrence is also affected by pH, temperature, and the concentration of certain acids. White casse forms only below pH 3.6 and is generally suppressed at cool temperatures. In contrast, blue casse is accentuated at cold temperatures. The frequency of white casse increases sharply as the iron concentration rises above 15–20 mg/liter. Recommended maximum amounts for iron in wine are in the range of≤4 mg/liter. Critical iron concentrations for the formation of blue casse have been more difficult to estimate. Its occurrence is markedly affected by the wine’s phosphate content and traces of copper (1 mg/liter). In addition, citric acid can chelate ferric and ferrous ions, reducing their effective (free) concentration in wine. Correspondingly, the addition of citric acid (~120 mg/liter) has been suggested as a means of limiting ferric casse development where it has been a problem (Amerine and Joslyn, 1970).

Wines may be directly stabilized against ferric casse by iron removal. For example, the addition of phytates, such as calcium phytate, selectively removes iron ions (Trela, 2010). EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), pectinic acid, and alginic acid can also be used to remove iron and copper ions. Removal with ferrocyanide is probably the most efficient method, as it precipitates most metal ions, including iron, copper, lead, zinc, and magnesium. The process is known as blue fining. Because of cyanide’s toxicity, blue fining is prohibited in many countries, and is strictly regulated where permitted. Filtration removes the insoluble metal–ferrocyanide complexes.

Ferric casse may also be controlled by the addition of agents that limit the flocculation of insoluble ferric complexes. Gum arabic acts in this manner. It functions as a protective colloid, restricting haze formation. Because gum arabic limits the clarification of colloidal material, it can only be safely applied after the wine has undergone all other stabilization procedures.

Copper Casse

Whereas iron casse develops on exposure to oxygen, copper casse forms solely in its absence. It develops only after bottling and is associated with a decrease in redox potential. Light exposure speeds the reduction of copper, critical in casse development. Sulfur dioxide is important, if not essential, for its development. In a series of incompletely understood reactions, involving the generation of hydrogen sulfide, cupric and cuprous sulfides form. The sulfides produce a fine, reddish-brown deposit, or they flocculate with proteins to form a reddish haze. Copper casse is particularly a problem with white wines, but can also cause haziness in rosé wines. Wines with copper contents greater than 0.5 mg/liter are particularly susceptible to copper casse development (Langhans and Schlotter, 1985). Values for copper in wine are generally recommended to be less than 0.2 mg/liter.

Masque

Occasionally, a deposit termed masque, forms on the inner surfaces of sparkling wine bottles. It results from the deposition of material formed by the interaction of albumin (used as a fining agent) and fatty acids (Maujean et al., 1978). Riddling and disgorging, used to eliminate yeast sediment, do not remove masque. Masque is a problem only with traditionally produced (méthode champenoise) sparkling wines, in which the wine is sold in the same bottle as that used for the second fermentation.

Lacquer-Like Bottle Deposits

In the 1990s, there was an increase in the worldwide incidence of a lacquer-like deposit in bottles of red wine. It appeared especially in higher-priced wines. The deposit developed within a few years, and could cover the entire inner surfaces of the bottle. It is not associated with a reduction in wine quality, but impeded sales due to the turbid perception.

The thin, film-like layer resulted from the deposition of a complex of tannins, anthocyanins and proteins (Waters et al., 1996a). The protein component was unexpected because the high tannin content of red wines has usually been thought to induce the protein precipitation before bottling. Although the mechanism of deposit formation is unknown, several factors can reduce its occurrence. These include the use of bentonite (>50 g/liter) and cold stabilization (−4°C for 5 days, followed by centrifugation at−4°C to remove insoluble material).

Microbial Stabilization

Microbial stability is not necessarily synonymous with microbial sterility. At bottling, wines may contain upwards of 103–104 viable cells/mL (Renouf et al., 2008). Under most situations, they provoke no stability or sensory problems. They remain metabolically inactive under in-bottle conditions.

The simplest procedure for conferring limited microbial stability is racking. Racking removes cells that have fallen out of the wine by flocculation, or have coprecipitated with tannins and proteins. The sediment includes both viable and nonviable microorganisms. The latter slowly undergo autolysis and release nutrients that could favor subsequent microbial growth. Microbial stability also relates to the wine’s basic chemistry, which is improved with minimal residual sugar (≤0.5 g/liter) and malic acid (≤30 mg/liter) contents, and low pH (≤3.3). Cool temperatures help maintain microbial viability, but retard or prevent metabolic action.