Another syndrome induced by some heterofermentative strains of lactic acid bacteria, notably Oenococcus oeni and Lactobacillus brevis, is termed mannitic fermentation. This form of spoilage is characterized by the production of marked amounts of mannitol, via the partial metabolism of fructose. In addition, this ‘disease’ may also be associated with the production of various amounts of acetic and lactic acids, propanol, 2-butanol, diacetyl, and the development of considerable viscosity (Sponholz, 1993). It has been described as expressing vinegary-estery attributes.

Ropiness is another spoilage syndrome, this time associated with the synthesis of profuse amounts of high-molecular-weight, fibrillar, mucilaginous polysaccharides (β-1,3-glucan chains with 1,2-glucopyranosyl branches). Pediococcus parvulus is most frequently associated with ropiness, but other Pediococcus species and a few strains of Leuconostoc have occasionally been implicated. Even some strains of O. oeni have been isolated from ropy cider. It can develop during fermentation, maturation, or post-bottling, notably in wines high in pH. The property is connected with the presence of a plasmid, carrying ropy(+). It appears to be associated with a gene coding for glucosyltransferase, gtf (Dols-Lafargue et al., 2008). Some of the polysaccharides form a capsule around the bacteria, holding them together in long silky chains (a biofilm). These may appear as floating threads in affected wine. Other portions are liberated into the wine. Especially when the wine is agitated, the polysaccharides become dispersed, giving the wine an oily look and viscous texture. Although visually unappealing, ropiness is infrequently associated with off-odors or tastes; it is also nontoxic. It may also be a prelude to mannitic fermentation, and the accumulation of high volatile acidity. Real-time PCR detection should facilitate rapid differentiation between the majority of harmless P. damnosus strains and those carrying ropy(+) (Delaherche et al., 2004).

The presence of mousy taints, noted previously in relationship to Brettanomyces, is also associated with several strains of Oenococcus oeni and Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Costello et al., 2001). As previously, these odors are produced by several N-heterocycles, notably 2-acetyltetrahydropyridine, 2-ethyltetrahydropyridine, and 2-propionyltetrahydropyridines, as well as several pyrrolines, notably 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (Grbin et al., 1996) and 3-acetyl-1-pyrroline (Herderich et al., 1995). Because these taints have low volatility at cellar temperatures, cellar masters may put a few drops of a sample on their hand, rub it, and then sniff.

Several species of Lactobacillus also have the potential to produce relatively high (up to 800 μg/liter) concentrations of 4-ethylphenol (Couto et al., 2006). Thus, Brettanomyces yeasts are not the only microbes associated with barnyardy/manure and mousy odors in wine.

Lactic acid bacteria may also generate a geranium-like taint in the presence of sorbic acid (Crowell and Guymon, 1975). It was formerly added as a yeast inhibitor in sweet wines. Some strains of Lactobacillus and most strains of Oenococcus oeni can metabolize sorbic acid to p-sorbic alcohol (2,4-hexadienol). Under acidic conditions, 2,4-hexadienol isomerizes to s-sorbic alcohol (1,3-hexadienol). In turn, upon reaction with ethanol it can form an ester, 2-ethoxyhexa-3,4-diene. It is the latter that generates the intense geranium-like odor.

High volatile acidity is a common aspect of most forms of spoilage associated with lactic acid bacteria. Acetic acid can be produced from the metabolism of citric, malic, tartaric, and/or gluconic acids, as well as hexoses, pentoses, and glycerol. The amount of acetic acid synthesized depends on the strain and conditions involved. However, production is very limited in the absence of suitable reducible substances. Thus, acetic acid production is rare under strictly anaerobic conditions.

A few Lactobacillus spp. have been periodically isolated from fortified wines, usually those containing high sugar contents. Stratiotis and Dicks (2002) found that most strains tolerant to high alcohol concentrations (22%) belonged to L. veriforme.

Acetic Acid Bacteria

The acetic acid bacteria were first recognized as causing wine spoilage in the nineteenth century. Their ability to oxidize ethanol to acetic acid induces wine spoilage and is central to commercial vinegar production. Although acetic acid synthesis during vinegar production has been extensively investigated, the action of acetic acid bacteria on grapes, and in must and wine, has surprisingly escaped intense scrutiny.

That acetic acid bacteria could remain viable in wine for years under anaerobic conditions was unexpected. They were thought to be strict aerobes, unable to grow or survive for long periods in the absence of oxygen. However, they are now known to have the ability to utilize the traces of oxygen absorbed by wine during clarification and maturation (Joyeux et al., 1984; Millet et al., 1995). In addition, they appear able to substitute quinones for molecular oxygen in respiration (Aldercreutz, 1986). Thus, they may even show limited metabolic activity under strictly anaerobic conditions. Thus, the role of acetic acid bacteria in all phases of winemaking deserves reinvestigation.

Acetic acid bacteria form a distinct family of gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria characterized by the oxidation of ethanol to acetic acid. One of the major consequences is acidification of the surrounding medium. The accumulation of acetic acid is primarily associated with the stationary and decline phases of colony growth (Kösebalaban and Özilgen, 1992).

The metabolism of sugar by acetic acid bacteria is atypical in many ways. For example, the pentose phosphate pathway is used exclusively for sugar oxidation to pyruvate, whereas pyruvate oxidation to acetate is by decarboxylation to acetaldehyde, rather than via acetyl-CoA. Sugars may also be oxidized to gluconic and mono- and diketogluconic acids, rather than metabolized to pyruvic acid (Eschenbruch and Dittrich, 1986). Although this property is most commonly associated with Gluconobacter oxydans, some strains of Acetobacter also possess this ability.

In addition to oxidizing ethanol to acetic acid, acetic acid bacteria oxidize other alcohols to their corresponding acids. Furthermore, they may oxidize polyols to ketones, for example glycerol to dihydroxyacetone.

Of the eight recognized genera of acetic acid bacteria, only Acetobacter and Gluconobacter commonly occur on grapes or in wine. They can be distinguished both metabolically and by the position of their flagella. Members of the Acetobacter have the ability to overoxidize ethanol; that is, they may oxidize ethanol past acetic acid to carbon dioxide and water, via the TCA cycle. Under the alcoholic conditions of wine, however, ethanol overoxidation is suppressed. In contrast, Gluconobacter lacks a functional TCA cycle, and cannot oxidize ethanol past acetic acid under any conditions. The Gluconobacter are further characterized by a greater ability to use sugars than Acetobacter. Motile forms of both genera can be distinguished by flagellar attachment. Gluconobacter has polar flagellation (insertion at the end of the cell), whereas Acetobacter has a more uniform (peritrichous) distribution. Of species in these genera, only A. aceti, A. pasteurianus, and G. oxydans are commonly found on grapes or in wine. A new species, Acetobacter oeni, has recently been isolated from spoiled red wine (Silva et al., 2006).

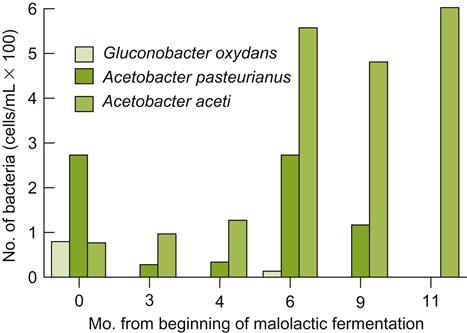

Although all three main species occur on grapes, and in must and wine, their frequency differs markedly. Gluconobacter oxydans is the predominant species on grape surfaces, probably because of its greater ability to metabolize sugars. On healthy fruit, the bacterium commonly occurs at about 102 cells/g. On diseased or damaged fruit, this value can rise to 106 cells/g (Joyeux et al., 1984). Although its presence in must and early during fermentation has generally been viewed negatively, its ability to produce esterases, active at must and wine pH values, indicate that it has the potential to significantly influence a wine’s ester profile (Navarro-González et al., 2012). In contrast, Acetobacter pasteurianus is typically present in small numbers, whereas A. aceti is only rarely isolated.

During fermentation, the number of viable bacteria in the must tends to decrease, although usually not below 102–103 cells/mL. The most marked change is in the relative proportion of the species. Gluconobacter oxydans declines during fermentation, being replaced by Acetobacter pasteurianus. Subsequently, its population may rise or fall during fermentation and maturation. A. aceti tends to become the dominant species after fermentation. Despite this, the population diversity (number of strains) of A. aceti declines considerably during fermentation (González et al., 2005). G. oxydans tends to disappear entirely during maturation (Fig. 8.80).

Although the viable population of acetic acid bacteria tends to decline during maturation, racking can induce temporary increases. This is probably due to the uptake of oxygen during racking. Oxygen can not only participate directly in bacterial respiration, but can also indirectly generate electron acceptors for respiration, notably quinones.

Spoilage can result from bacterial activity at any stage in wine production. For example, moldy grapes typically have high populations of acetic acid bacteria and can provoke spoilage immediately after crushing. By-products of metabolism, such as acetic acid and ethyl acetate, may be retained throughout fermentation and can taint the finished wine.

Spoilage by acetic acid bacteria during fermentation is rare, largely because most present-day winemaking practices restrict contact with air. Improved forms of pumping over and cooling have eliminated major sources of must oxidation during fermentation. Also, a better understanding of stuck fermentation can limit its incidence, permitting the earlier application of techniques that reduce the likelihood of oxidation and microbial growth.

Although wine maturation occurs largely under anaerobic conditions, storage in small oak cooperage increases the likelihood of oxygen uptake and reactivation of bacterial metabolism. Wood cooperage can also be a significant source of microbial contamination, if improperly stored, cleansed, and disinfected before use. Thus, it is not surprising that red wines tend to have higher levels of volatile acidity than their white counterparts (Eglinton and Henschke, 1999).

Alone, the levels of sulfur dioxide commonly maintained in maturing wine are insufficient to inhibit the growth of acetic acid bacteria. Therefore, combinations of techniques, such as maintaining or achieving low pH values, minimizing oxygen incorporation, and cool storage, along with sulfur dioxide, appear to be the most effective means of limiting the activity of acetic acid bacteria. Spoilage of bottled wine by acetic acid bacteria is presumably limited to situations where failure of the closure permits seepage of oxygen into the bottle.

The most well-known and serious consequence of spoilage by acetic acid bacteria is the production of high levels of acetic acid (volatile acidity). The recognition threshold for acetic acid is approximately 0.7 g/liter (Amerine and Roessler, 1983). At twice this value, it can give wine an unacceptably vinegary odor and taste.

Although wines mildly contaminated with volatile acidity may be improved by blending with unaffected wine, alternate solutions include treating with reverse osmosis (to remove the acetic acid), or blending with grape juice and refermenting (yeasts can metabolize the excess acetic acid). Seriously spoiled wines are fit only for distillation into industrial alcohol, or conversion into wine vinegar.

Under aerobic conditions, acetic acid bacteria do not synthesize noticeable amounts of esters. Although ethyl acetate production is increased at low oxygen levels, most of the ethyl acetate generated during acetic spoilage appears to arise from nonenzymatic esterification, or the activity of other contaminant microorganisms. Ethyl acetate may also be metabolized by several microbes. As a consequence, the strong sour vinegary odor of ethyl acetate is not consistently associated with spoilage by acetic acid bacteria (Eschenbruch and Dittrich, 1986). By itself, ethyl acetate possesses an acetone-like odor resembling nail-polish remover.

Another aromatic compound sporadically associated with spoilage by acetic acid bacteria is acetaldehyde. Under most circumstances, acetaldehyde is rapidly metabolized to acetic acid and seldom accumulates. However, the enzyme that oxidizes acetaldehyde to acetic acid is sensitive to denaturation by ethanol (Muraoka et al., 1983). As a result, acetaldehyde may accumulate in highly alcoholic wines. Low oxygen tensions also favor the synthesis of acetaldehyde from lactic acid.

Acetic acid bacteria spoilage generally does not produce a fusel taint. The bacteria oxidize higher alcohols (the source of a fusel taint) to their corresponding acids. In oxidizing polyols, acetic acid bacteria generate either ketones or sugars. For example, glycerol and sorbitol are metabolized to dihydroxyacetone and sorbose, respectively. The conversion of glycerol to dihydroxyacetone may affect the sensory properties of wine, due to its sweet fragrance and cooling mouth-feel. Dihydroxyacetone may also react with several amino acids, generating a crust-like aroma. Whether such a reaction has any involvement in the generation of the classic toasty aspect of better sparkling wines is unknown.

Some strains of acetic acid bacteria produce one or more types of polysaccharides from glucose. Their production in grapes may account for some of the difficulties in filtering wines made from some diseased fruit.

In addition to acetic acid, acetic acid bacteria often metabolize glucose to gluconic and mono- and diketogluconic acids. These compounds occur so frequently in association with fungal infections, notably Botrytis cinerea, that they have been used as indicators of the degree of infection.

Other Bacterial Spoilage

Because most bacteria do not grow well under acidic conditions, other than lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria, their involvement in spoilage is rare. Nevertheless, when it develops it can have serious financial consequences. The genus most frequently involved is Bacillus. Members of the genus are gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria that commonly produce long-lived, highly resistant endospores. Most species are aerobic, but some are facultatively anaerobic, as well as being acid- and alcohol-tolerant.

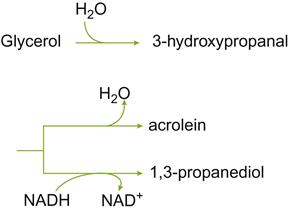

Bacillus polymyxa has been associated with the fermentation of glycerol to acrolein. Other species, including B. circulans, B. coagulans, B. pantothenticus, and B. subtilis, have been isolated from spoiled fortified dessert wines (Gini and Vaughn, 1962). B. megaterium may even grow sufficiently in bottled brandy to produce visible sediment.

Although unlikely to grow directly in wine, species of Streptomyces may be involved in wine tainting. Their growth has already been mentioned in regard to the production of off-odors associated with cork. Streptomyces may also grow on the surfaces of unfilled cooperage. Their ability to produce earthy, musty odors is well known. The synthesis of sesquiterpenols, notably geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol, is believed to be the principal source of the characteristic earthy odor of soil. Geosmin may also originate from the joint action of Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum on infected grapes (La Guerche et al., 2005).

Sulfur Off-Odors

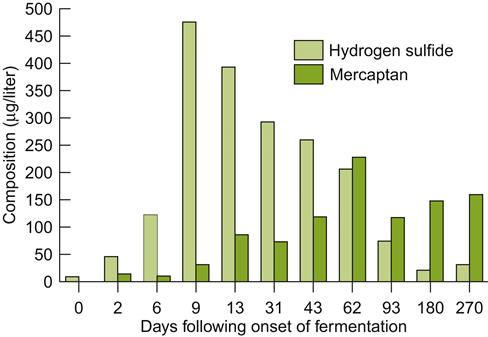

In minute quantities, reduced-sulfur compounds can contribute to the varietal fragrance of certain wines, as well as to their aromatic complexity. They can also be the source of revolting odors. Frequently, the difference is only a function of concentration. The principal offending compounds appear to be hydrogen sulfide (H2S), dimethyl disulfide, and mercaptans. Hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans develop putrid odors at concentrations of 1 ppb or less. In contrast, dimethyl disulfide expresses its cooked cabbage and shrimp-like quality only at concentrations some 30 times higher. In all cases, these off-odors have lower thresholds in sparkling and white wines than in red wines. Hydrogen sulfide can be generated throughout fermentation, maturation, and bottle aging, depending on conditions, whereas dimethyl disulfide and mercaptans are more frequently associated with maturation and bottle aging.

For reasons that remain unclear, but possibly due to increased awareness and a reduction in corked off-odors, the reported incidence of reduced-sulfur odors in wines has increased (Godden et al., 2001; Skouroumounis et al., 2005b). It has been estimated that they now constitute up to 50% of wines rejected at tastings (Roger et al., 2010).

At much above its sensory threshold, hydrogen sulfide produces a rotten-egg odor. The origin of hydrogen sulfide can be very diverse, due to its pivotal role in sulfur metabolism. Hydrogen sulfide may be generated from: sulfur fungicide residues on grapes; sulfate found in grape tissue; sulfite (derived from sulfur dioxide addition); and the degradation of sulfur-containing amino acids.

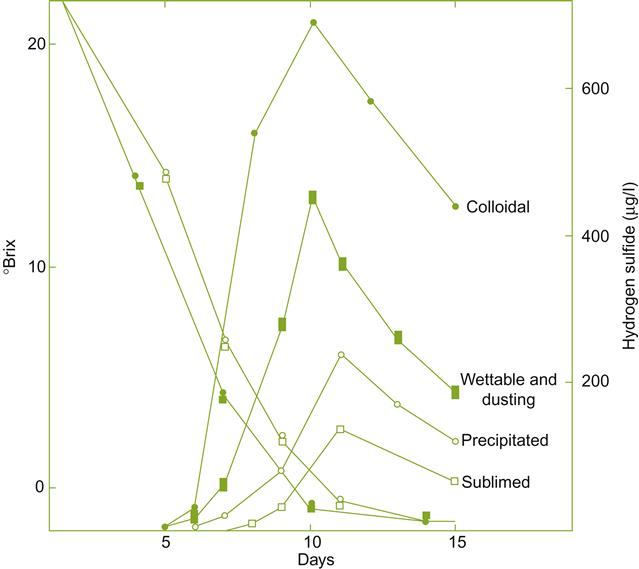

During fermentation, organosulfur fungicides do not appear to be a significant source of hydrogen sulfide, with the possible exception when applied late in the season. The primary source of hydrogen sulfide during vinification was once thought to be elemental sulfur, especially in colloidal form (Fig. 8.81). Stopping application (as a fungicide) at least 6 weeks prior to harvest limits its potential role in hydrogen sulfide production (Thomas et al., 1993).

Hydrogen sulfide possesses two distinct production phases during fermentation. The first occurs during the exponential phase of yeast growth, when demand for sulfur-containing amino acids is high. If these are not supplied in adequate amounts in the must, yeast cells produce sulfides from intracellular sulfates. Sulfides may also be generated if yeast cells come in contact with sulfur particles. If vitamin cofactors (pantothenate and pyridoxine) and nitrogen precursors of amino acids are limiting, sulfides produced escape into the must as hydrogen sulfide. Under these conditions the addition of both pantothenate and biotin (Bohlscheid et al., 2011), as well as diammonium hydrogen phosphate (DAP), tends to limit H2S accumulation. Their effectiveness depends on the amino acid requirements of the yeast strain involved in fermentation (Ugliano et al., 2009).

Although application of DAP can avoid the early accumulation of hydrogen sulfide, it has little effect on H2S liberation later on during fermentation. The second potential peak of hydrogen sulfide release is correlated with total assimilable nitrogen concentration. Generation is even more closely linked to the ratio of particular amino acids in the must. High concentrations of glutamic acid, alanine, and γ-amino butyric acid (GABA), relative to methionine, lysine, arginine, and phenylalanine, favor the release of hydrogen sulfide.

Additional features involved in limiting hydrogen sulfide synthesis include: lower fermentation temperatures; harvesting to possess adequate acidity; reduced levels of suspended-solids (>0.5%); fermentation in small fermentors (slower decline in redox potential); and limiting the addition or uptake of sulfur dioxide (such as during racking into newly sulfured barrels). If insufficient acetaldehyde is present to bind sulfur dioxide, other components such as sulfate may be reduced to hydrogen sulfide. Copper fungicide residues can augment H2S accumulation.

There have been several attempts to breed yeast strains with low to negligible ability to synthesize hydrogen sulfide. Although some strains are sulfite reductase-deficient (Zambonelli et al., 1984), they are dependent on external sources of sulfur-containing amino acids. Because sulfide synthesis is an integral aspect of yeast sulfur metabolism, all yeast strains generate some hydrogen sulfide. Nevertheless, some strains release less hydrogen sulfide than others, for example Pasteur Champagne, Epernay 2, and Prise de Mousse. To date, the most successful strain has been developed in Australia (Cordente et al., 2007). In contrast, the reduction of elemental sulfur to H2S by hydrogen peroxide, thought to occur at the cell-wall surface, would be nonenzymatic (Wainwright, 1970). Thus, this source of H2S would be largely beyond genetic modification.

Despite the normal release of hydrogen sulfide associated with yeast metabolism, most of it is carried off with carbon dioxide generated during fermentation. Further reduction in hydrogen sulfide content occurs during maturation. The oxidation of hydrogen sulfide to elemental sulfur may be coupled with the reduction of sulfur dioxide to sulfate. In addition, hydrogen sulfide can be oxidized to sulfur in the presence of hydrogen peroxide under acidic conditions. Removal of the precipitated sulfur during racking prevents subsequent reduction back to hydrogen sulfide.

Unacceptably high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide can also be reduced with aeration. However, this carries several risks. There is the possibility of activating dormant acetic acid bacteria and, for white wines, the potential for enhanced oxidative browning. An alternative procedure involves sparging with nitrogen.

More intractable are problems associated with the production of volatile organosulfur compounds, notably mercaptans and dimethyl sulfides. Once formed, they are difficult to remove. It often requires the combined actions of copper fining, and sulfur dioxide and ascorbic acid additions. Although synthesis typically occurs during maturation, compounds such as methylmercaptopropanol may form during fermentation (Lavigne et al., 1992). Cultivar and vineyard conditions play significant roles in their production, as well as high contents of soluble solids and sulfur dioxide.

During maturation, mercaptan synthesis is favored in the lees by the development of low redox potentials (Fig. 8.82). Although hydrogen sulfide theoretically can combine with acetaldehyde, forming ethyl mercaptan (ethanethiol), it apparently does not occur under wine conditions (Bobet, 1987). If present, ethyl mercaptan more likely comes from a slow reaction between diethyl disulfide and sulfite (Bobet et al., 1990). Nonetheless, hydrogen sulfide and acetaldehyde can generate 1,1-ethanedithiol under wine-like conditions (Rauhut et al., 1993). It possesses a sulfur, rubbery note.

The principal source of organosulfur compounds is sulfur-containing amino acids. Methionine can be metabolized by yeasts to methyl mercaptan, while cysteine is a source of dimethyl sulfide (de Mora et al., 1986). Dimethyl sulfide may also be generated when acetic acid bacteria use dimethyl sulfoxide as an electron donor during anaerobic respiration. Additional methyl mercaptan may arise from the hydrolysis of bisdithiocarbamate fungicides. Despite these potential sources, the dynamics and precise origin of most volatile organosulfur compounds remains a mystery. This clearly is a topic in need of investigation.

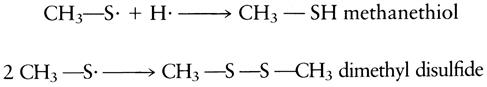

The occasional genesis of sulfide off-odors in bottled wine, notably champagne, appears clearer. They form in a complex series of reactions involving methionine, cysteine, riboflavin, and light (Maujean and Seguin, 1983). When photoactivated by light, riboflavin catalyzes the degradation of sulfur-containing amino acids. Various free radicals are formed, some of which combine to form methanethiol and dimethyl disulfide. Hydrogen sulfide also is generated under these conditions. Together, these compounds give rise to a light-struck (goût de lumière) fault. Wines can be protected from this fault by limiting the presence of amino acids and riboflavin, plus bottling in amber or anti-UV glass (to restrict the passage of the blue and UV radiation that catalyzes the reactions). The insensitivity of red wines to light-struck off-odors may relate to the binding of riboflavin by tannins. The significance and origin of the high concentrations of dimethyl sulfide typical of champagne are unclear. It accumulates regardless of light exposure.

Selectively removing hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans from wine is complicated. Activated carbon absorbs mercaptans, but reduces wine quality by also removing important aromatic compounds. Although mercaptans oxidize readily to disulfides, which have higher sensory thresholds, the reaction slowly reverses under the reducing conditions of bottled wine. Addition of trace amounts of silver chloride (Schneyder, 1965) or copper sulfate (Petrich, 1982), several months before bottling, can neutralize their odor. Removal of their metal precipitates is important as these reactions are also reversible. Unfortunately, these treatments can also remove thiol aromatics (Hatzidimitriou et al., 1996), important to the varietal fragrance of certain vinifera cultivars (Tominaga et al., 2000). Copper does not, however, remove disulfides, thioacetic acid esters, or cyclic sulfur-containing off-odors (Rauhut et al., 1993). In addition, care must be taken not to exceed permissible residual levels of copper (0.5 mg/liter in the United States; 0.2 mg/liter in most other wine-producing countries). Ascorbic acid may be added, in conjunction with copper sulfate and SO2, to limit disulfide production. By consuming oxygen, ascorbic acid limits the reoxidation of thiols back to disulfides. The reaction is very slow, though, taking months to complete. Metal salts have also been used diagnostically to differentiate between off-odors generated by hydrogen sulfide, mercaptans, or both (Brenner et al., 1954). The laboratory test is based on selective removal by copper and cadmium salts.

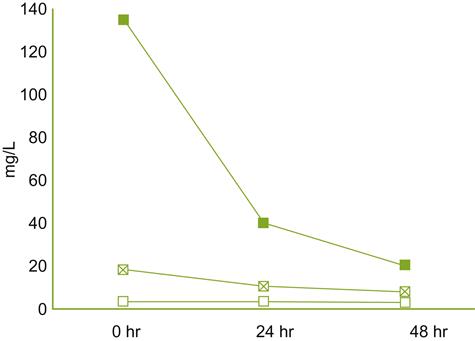

An alternative technique showing promise in removing mercaptans involves the addition of lees (Lavigne, 1998). This can even be the lees that generated the problem. By isolating and gently aerating the lees for approximately 24 h, mercaptans in the lees tend to dissipate. On readdition, yeast walls bind (and thus remove) various volatile reduced-sulfur compounds from the wine (Lavigne and Dubourdieu, 1996).

Additional suggestions for reducing the presence of reduced sulfur compounds include: the use of lower SO2 additions (≤50 mg/liter); low levels of soluble solids (Lavigne et al., 1992); slight oxidation after the first racking (Cuénat et al., 1990); and fermentation at cooler temperatures.

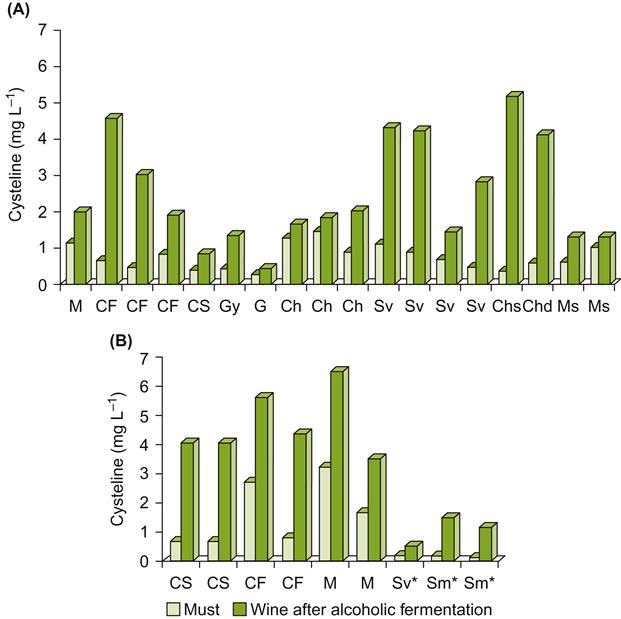

Development of an HPLC method for measuring free amino acid levels (Pripis-Nicolau et al., 2001) should facilitate measuring cysteine content. Because cysteine appears to be the primary source of thiol off-odors, assessment of its content may predict the degree of risk, and, thereby, the need for preventative measures. Figure 8.83 illustrates the considerable variation in cysteine content in the must and wine of several cultivars.

Despite the negative influence of most simpler sulfur and thiol compounds, many of the more complex thiols contribute to essential varietal attributes. However, like most generalizations, it is not true for all. A case in point is the thiol ester, ethyl 2-sulfanylacetate (Nikolantonaki and Darriet, 2011). It possesses a disagreeable, irritating, pungent odor possessing resemblances to baked beans and Fritillaria meleagris bulbs. It develops in Sauvignon blanc wines, especially when the juice comes from the last press-run. Its presence has also been detected in wines made from Riesling, Merlot, and Grenache, among others. Its concentration appears to increase for several years during in-bottle aging.

Additional Spoilage Problems

Light Exposure

In addition to the light-induced, reduced-sulfur off-odor noted above, light can also cause other faults in sparkling wines. For example, it can induce the development of an unpleasant taste and odor resembling aromatic herbs and preserved vegetables in Asti Spumante (Di Stefano and Ciolfi, 1985). Sunlight exposure can also result in a loss of several aromatic terpenes, as well as generating novel terpenes, notably 3-ethoxy-3,7-dimethyl-1-octen-7-ol. These changes were enhanced in the presence of sulfur dioxide, but reduced when sorbic acid was added. Other changes in wine exposed to light include a marked reduction in fruit ester content, and an enhanced presence of 2-methylpropanol (D’Auria et al., 2003).

Light also has the capacity to favor browning reactions, through the iron-catalyzed oxidative reactions, for example the decarboxylation of tartaric acid to glyoxylic acid (Clark et al., 2011). The latter can bond with two flavan-3-ols, generating yellow-pigmented xanthylium pigments (Maury et al., 2010).

Untypical Aged Flavor

‘Untypical aged’ (UTA) is an off-odor that tends to develop about a year after bottling. It is usually associated with wines made from grapes having suffered stress during the growing season (Sponholz and Hühn, 1996). The problem has been correlated with the presence of o-aminoacetophenone and possibly skatole (3-methylindole). The off-odor is characterized by naphthalene, furniture polish, or wet wool attributes. o-Aminoacetophenone appears to be a degradation by-product of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), one of the major phytohormones in plants. This is favored by the presence of superoxide radicles, produced in association with the aerobic oxidation of sulfite (Hoenicke et al., 2002). Although IAA is itself derived from the amino acid, the must content of neither IAA nor tryptophan appears to be connected with vine nitrogen fertilization (Linsenmeier et al., 2004), despite the incidence of UTA reflecting the level of nitrogen fertilization (Linsenmeier et al., 2007). Methional (3-methylthio propionaldehyde) may also be associated with UTA (Rauhut et al., 2001).

The occurrence of this disorder appears to be reduced by the incorporation of thiamine before fermentation, the addition of diammonium phosphate (if must-assimilable nitrogen is low or yeast strains requiring high nitrogen contents are used), and the addition of ascorbic acid (150 mg) (Rauhut et al., 2001). Recently, Henick-Kling et al. (2005) have questioned the involvement of o-aminoacetophenone or skatole in this fault. They found trimethyl-1,5-dihydronaphthalene (TDN) and the loss of volatile terpenes were better indicators of UTA occurrence in New York State. This association was especially marked when water deficit occurred just before or during véraison. However, this difference in opinion may be related to a different interpretation of what constitutes UTA, called ATA in North America. Rapp (1998) makes a distinction between UTA (caused primarily by o-aminoacetophenone) and the kerosene note generated by TDN. Occasionally the presence of UTA is masked by the simultaneous occurrence of reduced-sulfur odors.

Oxidation

Oxidation can cause serious deterioration throughout the winemaking process. Historically, it was associated with a marked increase in the likelihood of microbial spoilage. Currently, it is more connected with an abnormal and early shift in color toward brown, and the development of an ill-defined oxidized odor. Expressions such a honey, boiled potato, cooked vegetables, and hay have occasionally been used to represent its aromatic attributes in white wines. Loss of fruit/jam/floral attributes is a general characteristic. Although imprecise, these separate effects may be no more than expressions of oxidation taking alternate courses in different varietal or stylistic wines, and with the degree of oxidation.

Although the most serious oxidation reactions in bottled wines are thought to be associated with the ingress of oxygen (Karbowiak et al., 2010), molecular oxygen is itself seldom directly involved. Typically, oxygen must be activated in the presence of metal catalysts, such as iron and copper, or by light absorbed by pigments such as riboflavin. The more reactive oxygen states generated may include the superoxide (O2.−) and hydroxyl (HO.) radicles, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

The most well-known oxygen reaction in wine involves the generation of hydrogen peroxide, from the interaction of oxygen radicals and phenolics (see Fig. 8.32). The principal organic compound oxidized by hydrogen peroxide is ethanol, presumably because it is the major oxidizable substrate in wine. The by-product, acetaldehyde, rapidly binds with other wine constituents, resulting in its low, free, volatile content in wine. In a complex sequence of reactions, quinones generated during phenol oxidation begin to polymerize. These undergo slow structural reorganization, and regenerate further oxidizable substrate (see Chapter 6). The quinones so generated, and their polymers, produce much of the brownish color in white wines. They are also involved in the shift from the purplish red color of young red wines toward orangish brick and eventually to tawny shades. Although oxidative browning occurs in both white and red wines, it becomes more noticeable earlier in white wines. This undoubtedly results from their paler color, and the lower phenolic concentration (i.e., their limited ability to consume oxygen). Oxidative degradation during storage is particularly a problem in bottles stoppered with short low-quality corks, in most synthetic corks, and in wine stored in bag-in-box containers.

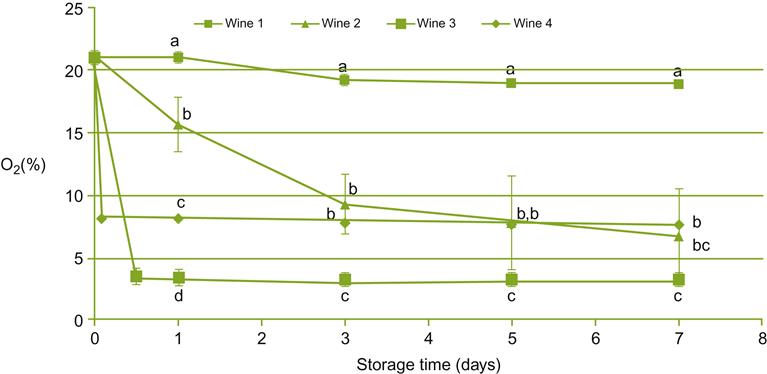

The term ‘oxidation’ is also traditionally applied to the aroma deterioration of wine after bottle opening, despite the known slow uptake of oxygen via diffusion (Fig. 8.84), even at high temperatures (Singleton, 1987). Lee et al. (2011) observed significant reductions in several esters and higher alcohols after wine was constantly agitated in the presence of air for a week. However, the experimental conditions were vastly different from the minimal oxygen uptake post-bottle opening. The conditions used in deriving the data in Fig. 8.85 are less drastic, but still not equivalent to those typical in a home situation. Nonetheless, the results indicate that significant hydrolytic breakdown of ethyl and acetate esters, and to a lesser extent the oxidation of volatile terpenes (Fig. 8.85), can occur. Subjectively, these changes were associated with a loss in fruity, sweet aspects, and the development of animal, dairy, and bitter attributes. The oxidative nature of such changes is supported by the protective action of antioxidants, such as caffeic acid and N-acetyl-cysteine (Roussis et al., 2005).

———

——— ), and terpenols (

), and terpenols ( ———

——— ) after opening of a bottle of Muscat wine (20°C). (Data from Roussis et al., 2005.)

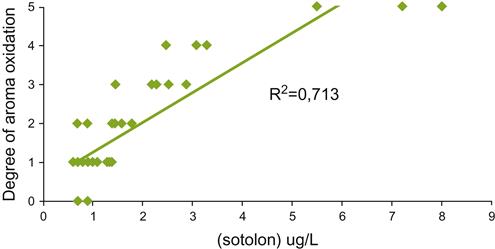

) after opening of a bottle of Muscat wine (20°C). (Data from Roussis et al., 2005.)Presumably, slower reactions are involved in the generation of the prune-like character described by Pons et al. (2008) involved in the premature aging in red wines. This feature is associated with the production of several lactones, and especially the diketone, 3-methyl-2,4-nonanedione. A curry-like fragrance, associated with sotolon, can also develop in some white wines exposed to oxygen (Fig. 8.86).

Regrettably, most studies have not assessed the headspace concentration of these aromatics, or their changes over time intervals corresponding to consumer conditions. Thus, the involvement of oxidation in a wine’s ‘opening’ (supposedly increased by wine aerators), in the need for wine to ‘breath,’ or in the rapid flavor deterioration of partially consumed bottles remains unsupported. Equally, the common view that small amounts of acetaldehyde, generated upon exposure to air, mask or dominate the wine’s fragrance is unsupported by direct observation (Escudero et al., 2002). Acetaldehyde rarely reaches levels above its sensory threshold (100–125 mg/liter) required for detection, except in wines such as sherries.

Aromatic changes in wine following bottle opening are probably most affected by factors associated with the wine/air interface. Simply removing the closure exposes the wine to only minimal air (oxygen) contact (equivalent to ~0.4 cm2/100 mL for a 750-ml bottle). Due to oxygen’s slow diffusion rate, and the short time-span involved, the likelihood of any sensorially significant oxidation (‘breathing’) is next to nil. It took several days for 20-mL samples of wine, in open-topped 60-mL-capacity bottles, to show significant reductions in the concentration of aromatics (Roussis et al., 2009). This is about 50 times the surface area/volume ratio of a newly opened, 750-mL bottle of wine.

However, pouring some of the wine out of a bottle markedly increases the surface area exposure to air and augments the amount of headspace volume in the bottle, as well as possibly generating moderate but short-lived turbulence. All of these features increase the opportunity for oxygen uptake. Were half the contents poured out, the surface area/volume ratio of the wine would increase about 20 fold, to 7.5 cm2/100 mL. If corked and stored, air in the bottle would contain about 120 mg of oxygen, which is ample to potentially produce sensory detectable changes. Over several days, especially at room temperature, this could lead to oxidation.

When wine is poured into a glass and swirled, wine-to-air contact is further enhanced. However, no known oxidative reactions in wine are known to occur sufficiently rapidly to be of sensory significance within the duration of a wine tasting. In contrast, swirling does facilitate the liberation of aromatic compounds into the headspace above the wine. It is this aspect of wine-to-air contact that is important.

A similar phenomenon occurs more slowly in sealed but partially empty bottles of wines. It is the liberation of volatiles into the headspace that is probably the most significant factor affecting flavor loss in opened bottles. This results from the changed equilibrium between the small amounts of aromatics in the wine (dissolved and weakly bound with other organics, i.e., the wine’s matrix) and the increased headspace volume. Although important in supplying aromatics to the air during a tasting, the liberation of volatiles into the headspace could result in irreversible aromatic loss in partially emptied bottles. This situation is subjectively detectible in the depauperated fragrance of wine poured out of partially emptied bottles after several days. By comparison, the glorious fragrance detectable at the neck of the emptied bottle is amazing. Regrettably this phenomenon has not been investigated. Most solutions to improve wine aroma in the glass, and reduce its deterioration in partially consumed bottles, are likely ‘barking up the wrong tree.’

Heat

Despite temperature extremes inducing serious degradation during transport or warehouse storage, the phenomena has only recently begun to receive the study it deserves (Beech and Redmond, 1981; Robinson et al., 2010; Butzke et al., 2012; Hopfer et al., 2012). Direct exposure to sunlight further accentuates the negative effects of unfavorable storage temperatures.

Accelerated hydrolysis of aromatic esters and a loss of terpene fragrances are among the known negative effects of exposure to high temperatures. Both changes reduce the fruity and/or varietal attributes of wine. Furfurals derived from sugars are believed to be partially involved in the development of a baked character. Exposure to temperatures above 50°C quickly accelerates the generation of caramelization products. These affect both the wine’s bouquet and color. Browning in red wines, in association with exposure to high temperatures, results from the degradation of anthocyanins and the generation of phenolic polymers. Their subsequent precipitation can lead to sediment formation.

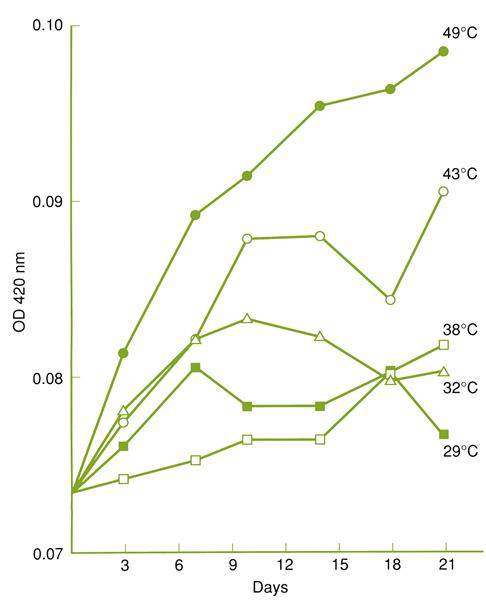

Important changes can occur even within a few days at elevated temperatures (Fig. 8.87). Consequently, temperature control is important during all stages of wine transport and storage. Devices are now commercially available to assess temperature fluctuation during shipment. The more extensive use of such products, and associated better storage during transport, should see a reduction of temperature-induced wine damage. Sulfur dioxide (100 mg/liter) apparently minimizes some of the effects (Ough, 1985). This was thought to be unrelated to its antioxidant property.

By affecting wine volume, rapid temperature fluctuation can also loosen the cork seal, leading to leakage, oxidation, and possible microbial contamination. The smaller the headspace volume, the more significant these volume changes are. However, if the temperature fluctuations occur slowly, the absorption and escape of carbon dioxide from the wine can minimize the associated pressure changes and potential leakage.

Storage Orientation

It is traditional for wine closed with cork to be stored horizontally. This places the cork in direct contact with the wine, preventing drying and shrinkage of the cork. Although the importance of this in limiting wine oxidation is commonly acknowledged, the damage caused by upright positioning does not necessarily occur rapidly. Lopes et al. (2006) did not find marked differences in oxygen penetration between vertical and horizontal positioning over a 2-year period. In addition, Skouroumounis et al. (2005b) found that it took several years for the effects of upright storage to result in distinct browning, or the development of an oxidized odor (cooked vegetable, nutty, and sherry-like aspects). In contrast, Mas et al. (2002) found vertical positioning distinctly unfavorable to wine development. Bartowsky et al. (2003) found that upright storage made red wine more susceptible to spoilage by Acetobacter pasteurianus. Bacterial growth could be detected by the presence of a ring-like growth at the wine/headspace interface.

Accidental Contamination

Intentional adulteration of wine has probably occurred since time immemorial. Vinegar, aged seawater, and various spices were added to wine in Roman times. These were, at the time, not considered adulterations. Lead salts were occasionally added during the Middle Ages to ‘sweeten’ highly acidic wine. Laws forbidding such additives were being enacted in Europe by at least 1327. In that year, William, Count of Hennegau, Holland, proclaimed an edict that outlawed the addition of lead sulfate, mercury, and similar compounds to wine (Beckmann, 1846). Concern about unintentional contamination is more recent. Only since the 1970s have sufficiently accurate analytic tools become available that can identify many of the contaminants that periodically can despoil wine.

Typically, heavy metals occur in wine at considerably below toxic levels. When metals occur at above trace amounts, they usually arise from contamination after fermentation: for example, activated carbon can be an unsuspected source of chromium, calcium, and magnesium; diatomaceous earth may be a source of iron contamination; and bentonite can act as a source of aluminum.

Tin-lined lead capsules were once an occasional source of metal contamination in old wine. Corrosion of the capsule could produce a deposit of soluble lead salts on the lip of the bottle. Although the salts did not diffuse through the cork into the wine (Gulson et al., 1992), failure to adequately cleanse the neck could contaminate the wine during pouring (Sneyd, 1988). With old bottles possessing a lead capsule, cleaning the bottle mouth thoroughly prior to puncturing the cork with a corkscrew avoided contamination. Although advisable, removing corks from old bottles is always problematic. They tend to break and crumble on removal. This development can be minimized, if not avoided, using a new corkscrew – The Durand™. It combines the actions of both a central helical screw and two blades that slide down between the cork and the bottle neck. Alternatively, the neck of the bottle may be removed with the cork intact.2 Currently, instances of lead contamination, arising from the use of brass tubing and faucets on winery equipment (Kaufmann, 1998), are rare. Structural cork faults are another, but unlikely, route leading to lead contamination.

Incidental off-odor contamination can arise from an incredibly wide range of unsuspected sources, including blanketing gases, fortifying brandies, oil and refrigerant leaks, desorption from wax-coated cement fermentation and storage tanks, leaching of chemicals from epoxy paints and resins used on winery equipment, and chlorophenol used to protect the surfaces of cooperage or other wooden structures (see Strauss et al., 1985).

Naphthalene absorbed by cork from the environment has already been noted. Naphthalene may also come from fiberglass used in the construction of holding tanks, resin used to seal tank joints, compounds used to adhere polyvinyl chloride inlays in bottle caps, and from adsorption onto wax used to coat cement tanks. In the last instance, the naphthalene may come from oil or solvent spills in or near fermentation or storage tanks (Strauss et al., 1985). Naphthalene gives wine a musty note at levels above 0.02 mg/liter. In contrast, the naphthalene-like odor associated with the UTA flavor has usually been correlated with the presence of o-aminoacetophenone.

Benzaldehyde is another off-odor occasionally associated with the use of epoxy resins. It has the potential to produce a bitter almond odor when its concentration reaches 2–3 mg/liter (Brun, 1984). Benzaldehyde is derived from the oxidation of benzyl alcohol. It is occasionally used as a plasticizer in epoxy resins, or found as a contaminant in liquid gelatin (Delfini, 1987). Several microbes can oxidize benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde. These include Botrytis cinerea and the yeasts Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Zygosaccharomyces bailii (Delfini et al., 1991). The latter two may also synthesize benzyl alcohol and benzoic acid. Various ketone notes may also be associated with epoxy resin contaminants. Improperly formulated resins can be a source of methyl isobutyl ketone, methyl ethyl ketone, acetone, toluene, and xylene (Brun, 1984). In addition, trace amounts of the hardener methylenedianiline, and its monomers bisphenol and epichlorhydrin, may migrate into wine stored in cement and steel tanks coated with some epoxy resins. However, they do not appear to accumulate in concentrations sufficient to affect the wine’s sensory attributes (Larroque et al., 1989).

Fiberglass tanks occasionally retain a small amount of free styrene (Wagner et al., 1994). If the styrene migrates into the wine, at levels above 0.1–0.2 mg/liter, it may donate a plastic odor and taste (Brun, 1984). Styrene is also a by-product of the decarboxylation of cinnamic acid during fermentation, although its natural occurrence in wine is much lower, from about 1–8 μg/liter (Sponholz, 1990).

Transport tanks lined with polyvinylchloride (PVC) may release butyltins (Forsyth et al., 1992). Butyltin is occasionally used as a PVC stabilizer. The presence of this compound does not affect the sensory qualities of the wine, but does suggest that a food-grade form of PVC was not used. Butyltin is a member of a group of compounds called organotins. They have diverse uses in industry, including wood preservation, catalysts, and as an antifouling agent in marine paint.

Residues from degreasing solvents and improperly formulated paints can be additional sources of taints. When winery equipment is disinfected with hypochlorite, the chlorine may react with degreasing solvents or phenols found in paint (Strauss et al., 1985; Bertrand and Barrios, 1995). As a consequence, one or more chlorophenols may be generated. Wine coming in contact with the affected equipment may show vague medicinal, chemical, or disinfectant odors. Chlorophenols may also be used as wood preservatives. These compounds may be microbially metabolized, producing 2,4,6-trichloroanisole, related chloroanisoles, and diverse chlorophenols. Examples recently detected as generating wine taints are 2-chloro-6- methyl phenol and 2,6-dichlorophenol (Capone et al., 2010b). If wine cellars are poorly aerated, these volatile compounds may bind to cooperage surfaces as well as materials stored within the cellar, such as cork and fining agents (Chatonnet et al., 1994c). These may subsequently contaminate stored wine with corky, musty, or moldy off-odors. When detected before bottling, treating the affected wine with highly absorbing yeast hulls (Fernandez et al., 2007) or passage through a molecularly imprinted polymer (Garde-Cerdán et al., 2008) are options.

Prolonged storage of water in tanks can also lead to the development of strong, musty, earthy taints. This is usually associated with the growth of actinomycetes, such as Streptomyces. If the water is subsequently used to dilute distilled spirits in fortifying dessert wines, the wine will develop an earthy off-odor (see Gerber, 1979).

Recently, producers in Ontario and adjacent American states have experienced wines tainted with a bell pepper/herbaceous off-odor. This taint was associated with grape infestation by large populations of Multicolored Asian lady beetles (Harmonia axyridis). When irritated, the insects release a yellowish fluid containing several methoxypyrazines. As few as one beetle per liter of juice can produce a detectable off-odor (Pickering et al., 2004). At 10 beetles per liter, the wine’s character is seriously compromised. This equates to 1200–1500 beetles per 1000 kg of fresh grapes. The taint is not diminished to any significant degree during aging, but can be partially masked by maturation in oak cooperage, or reduced by fermentation in the presence of activated charcoal (Pickering et al., 2006). The taint can also be significantly reduced, with minor effects on other aromatics, by the addition of food-grade silicone (Ryona et al., 2012). The procedure could also be used for musts or wines possessing natural concentration of methoxypyrazines that mask important varietal aromatics. The beetles were imported into North America and Europe as a biocontrol agent for crop pests. Regrettably, the lady beetle has faired so well that it has become a nuisance for home owners in its own right, and has reduced wine quality in North America and Europe.

Another taint of comparatively recent origin comes from exposure of vines and fruit to smoke from brush fires. Although the aromatic composition of smoke is complex (Hayasaka et al., 2013), the most significant compounds contaminating affected wines appear to be guaiacol and 4-methylguaiacol (Kennison et al., 2008), potentially combined with cresol isomers (Parker et al., 2012). They generate attributes described as smoky/ash, burnt rubber, leather, and/or smoked meat. They can quickly accumulate to values that can mask the fruity and other varietal attributes of a wine. Quaiacols also occur in wines aged in toasted oak barrels, but at considerably lower concentrations.

Grapes are most sensitive to smoke uptake about a week after véraison, and up to harvest (Kennison et al., 2009). Repeat exposures are cumulative. Because most of the absorption occurs in the skin (Dungey et al., 2011), the longer maceration times of red wines means they are more susceptible than other wines to expressing a smoky taint. Mechanical harvest is also likely to increase any smoke taint, due to the inclusion of contaminated leaf material in the crush. The sensory impact of exposure increases during aging, due to the progressive hydrolysis of nonvolatile glycosidic conjugates (Kennison et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2011). In addition, the smoky aspect may become more pronounced in the mouth, as a consequence of the action of oral hydrolytic enzymes (Parker et al., 2012). Smoke-affected wines may be improved using selected fining agents, especially activated carbon, with little impact on wine color (Fudge et al., 2012).

Another potential contaminant, depending on personal response, could be a detectable presence of cineole. It is the predominant oil from Eucalyptus trees. The presence of this terpene oil in wine has been previously discussed in Chapter 6.

The discovery of ochratoxin A in plant materials, a potential human toxin, has led to an extensive survey of its presence in wine (O’Brien and Dietrich, 2005; Varga and Kozakiewicz, 2006). Toxin producers include several hyphomycetes – mostly, but not exclusively, members of the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium. The species most commonly implicated are members of the black aspergilli, notably Aspergillus carbonarius. As general saprophytes, they tend to occur on infected or damaged plant tissues, such as grapes. Nonetheless, they can also grow on improperly cleaned and maintained winery equipment.

Currently, only Europe has set legal limits on ochratoxin A occurrence in wine (2 μg/liter) and defined its safety limit as 5 μg/day from all sources. About 80% of the toxin that may be associated with grapes is lost with the skins and pulp during pressing (Leong et al., 2006). Yeasts subsequently absorb about half of the remaining ochratoxin A (Cecchini et al., 2006). This portion is lost during racking (Fernandes et al., 2007). The concentration of ochratoxin A is further diminished during fining or filtering (Gambuti et al., 2005), notably if activated carbon has been added (Valdés-Sánchez et al., 2005). It is also removed efficiently by bentonite (Mine Kurtbay et al., 2008). Additional toxin may be removed by binding with oak chips, especially oak powder used to donate an oak flavor (Savino et al., 2007). Contact with uncontaminated grape pomace also extracts toxin (Solfrizzo et al., 2010). Metabolism by Oenococcus oeni during malolactic fermentation can further reduce its presence. Metabolism by Botrytis cinerea may explain the surprisingly low concentration of ochratoxin A in botrytized wines (Valero et al., 2008). Contamination is usually avoided by proper winery sanitation and the use of healthy grapes. Occasionally, fungicidal sprays (e.g., Switch®) have been used to limit the incidence of Aspergillus on grapes. For a review of ochratoxin A removal in wine see Quintela et al. (2013).

Wastewater Treatment

As environmental issues come more to the fore, safely and acceptably voiding winery waste is becoming an increasingly costly and regulatory issue. Legal issues are definitely beyond the scope of this text, but the science of wastewater treatment is certainly within its realm.

An unavoidable consequence of wine production is the generation of considerable waste, both solid and liquid. It is estimated that about 20% of the grape (i.e., stalks, seeds, skins) is waste. Liquid waste is more variable in volume and origin. Its generation can commence during crushing/pressing, originate from spillover during fermentation, or arise as a consequence of clarification, racking, fermentor, barrel and bottle cleansing, and general winery hygiene. Except for locations where municipal waste treatment systems are close by and accept winery wastes at affordable prices (usually applicable only to smaller wineries), the material must be treated on-site or transferred for commercial disposal.

Occasionally, some of the waste can be a resource. For example, seed oil may be extracted. Its moderately high smoke-point (216°C) and mild taste qualify it for use in household cooking. The skins of red grapes may also be used as a source of nutraceuticals, such as resveratrol, antioxidant flavonoids, and tartrate (cream of tartar). For details on these and other uses of winery waste see Arvanitoyannis et al. (2006). More frequently, pomace and stem waste is just that – waste. Optimally, it can be composted (see Chapter 4), producing a valuable soil amendment. Otherwise, solids may be disposed of as landfill.

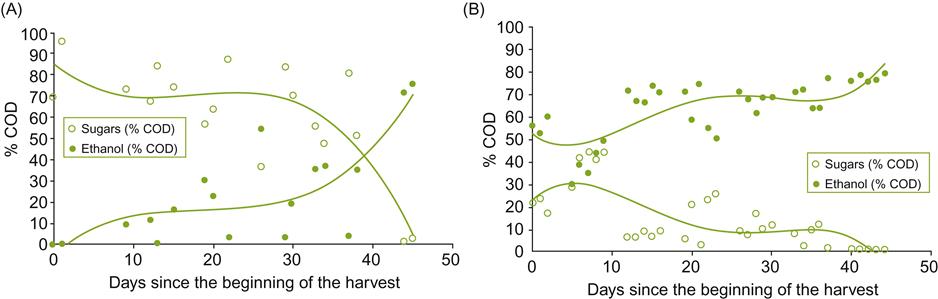

The variable composition of liquid waste (Fig. 8.88), with its distinct peaks and surges, both temporally and in volume, makes its disposal more problematic. These features create trouble with any treatment system. Its disposal requires not only system tailoring to individual wineries, but also its volume and organic content also need to be reduced. These issues are sufficiently important to have spawned an extensive literature. Much of the detail relates to civil engineering, but certain biologic aspects are worth noting here.

The COD (chemical oxygen demand) of winery waste is largely dependent on its soluble organic content, due to the relative absence of other oxidizable compounds. As such, it is often measured as the BOD5 – a laboratory procedure assessing the amount of oxygen consumed by a specified sample volume, within a 5-day period, under standardized conditions. For red wines, the principal constituents are ethanol and acetic acid, with smaller amounts of organic and fatty acids, phenolics, and small amounts of sugars (Sheridan et al., 2011). For white, rosé, and thermovinified red wine wastewaters (liquid from the pressed pomace remains), sugars tend to be their primary organic constituent (Bories and Sire, 2010). The style of wine can also significantly affect the periodicity of wastewater surges. If not protected by screening, wastewater may also be contaminated by pomace (seeds and skin). Yeasts, bacteria, and fining agents are also found in wastewater; their presence complicates treatment and increases the cost and duration of treatment.

Treatment typically involves three phases: a primary physical stage, a secondary biological period, and a tertiary polishing or chemical treatment. Physical treatment often involves the use of sieves, filters, and/or sedimentation to reduce the solids content. The storage phase involved in sedimentation can also function as surge protection, equalizing the flow going to biological (secondary) treatment. Biological treatment relates to microbial degradation of the organic material to some defined level of oxygen (BOD) demand. After removal of any residual solids (by settling), tertiary treatment may involve further pH or other chemical adjustments. This may be necessary before the water can be released into a drainage system or wetland, or applied as irrigation water (Laurenson et al., 2012).

As with composting pomace, preliminary chemical adjustment is preferable before secondary (biological) treatment. If treatment is aerobic, this typically involves raising the pH to near neutral. This is less important in an anaerobic digester because it tends to operate at lower pH values than aerobic digesters.

Treatment Systems

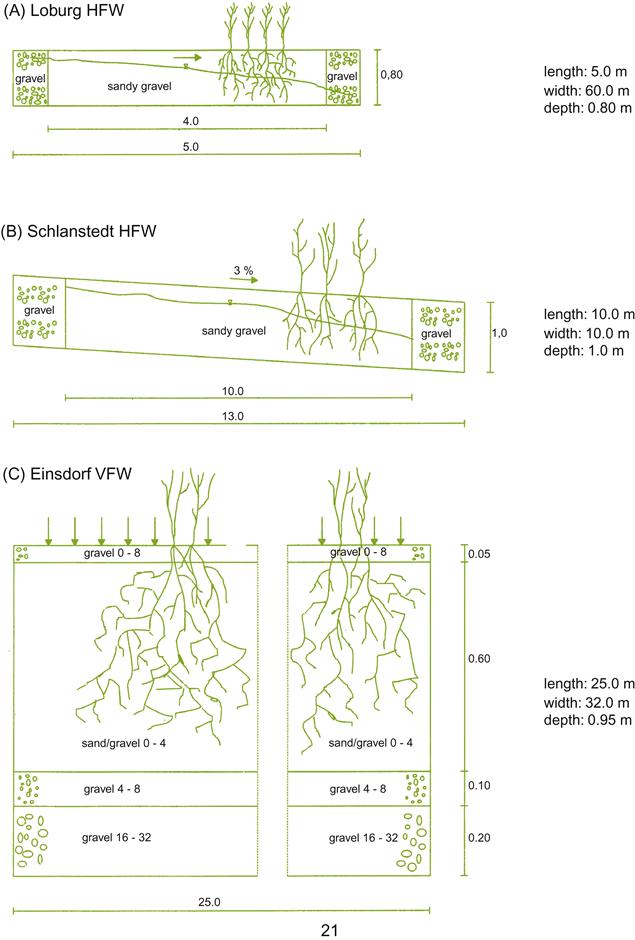

In the past, winery wastewaters were often directly released into an adjacent stream or wetland. Although currently unacceptable, a modified version can entail the construction of an artificial wetland, with a horizontal subsurface flow (Vymazal, 2009). This involves creating a porous underlay for a relatively horizontal, elongated, lined bed. It is planted with semiaquatics, such as Juncus ingens (Great rush), Phragmites communis (Ditch reed), Scirpus lacustris (bulrush), and Typha latifolia (Cattail), depending on the location. As the wastewater flows through the porous substratum (often gravel), its organic content decomposes both aerobically and anaerobically, supplying inorganic nutrients to the plants. Their roots, in turn, facilitate air penetration into the substratum. The system avoids most problems that can otherwise arise with insects and odors. An alternative system applies the wastewater broadly over the surface, but otherwise is basically similar (Fig. 8.89). The effluent is collected as it exits the contained wetland.

More frequently used, and less expensive, is a lagoon system. At its simplest, it is a large, lined reservoir where the waste is sent for holding. Solids settle to the bottom, where they begin to decompose, primarily under bacterial action. The inorganic nutrients released support surface algal growth. They supply oxygen to the system. Alternatively, oxygen may be supplied by an aerator or, where adequate, wind turbulence. A lagoon system may also be subdivided into a series, the first being anaerobic and subsequent one(s) being aerobic. Although comparatively slow acting, it does not depend on a relatively steady supply of wastewater to maintain its optimal effectiveness. In addition, if the water is not desired for irrigation or cannot be legally discharged, its large surface area encourages evaporation. Its principal disadvantage involves the release of off-odors. This results from the production of fatty acids, such as butyric and propionic acids. This situation can often be reduced by the application of calcium nitrate, a nitrogen source (Bories et al., 2007). Without nitrogen enrichment, volatile fatty acids can constitute up to 60% of the COD. Subsequent microbial denitrification avoids contaminating the finished effluent with nitrates. Other malodorous problems can arise from the generation of reduced-sulfur compounds. This is particularly a problem if the bottom of the lagoon becomes excessively anaerobic. Odor problems are especially a problem close to inhabited areas, requiring a cover to limit odor escape. Lagoons can also be costly, due to the land tied up in the system. If not regulated properly, they can also be a source of annoying insect populations. Although generally not a significant limitation in viticultural regions, lagoons do not function effectively in cold climates. Periodically, bacterial and algal remains (sludge) must be removed from the bottom of the lagoon(s). This can be added to pomace destined for composting or other solids management.

Activated sludge digesters are fully enclosed systems with higher throughput, but they are more expensive to construct and can be complex to operate efficiently. They require continuous agitation to supply the extensive aeration necessary to maintain the complex ecosystem. Biologically, it operates as a complex of bacterial, yeast, and filamentous fungal digesters. These frequently congregate in a cottony, zoogloeal floc. This is, in turn, grazed by a range of protozoa. As the organic material is degraded, new biomass is generated, which, in sequence, is digested and grazed upon by additional components of the ecosystem. After the BOD declines to an acceptable value, the material moves to a clarifier, where the zoogloeal mass settles. Some of the mass is returned, acting partially as an inoculum for a new infusion of wastewater. The liquid component is sent on for tertiary treatment. The remainder of the solids are added to pomace and composted, if they are not of a quality acceptable for direct application to the vineyard (Fumi et al., 1995). Although possessing the potential for rapid and high throughput, activated sludge digesters work best with a steady supply of wastewater of relatively consistent chemistry. In situations of high surge organic loading, a slurry of bentonite may be added. It provides attachment sites for rapid new floc formation. Alternatively, sequence-batch digesters consist of activated sludge components designed specifically to function with effluent surges (Andreottola et al., 2002).

Anaerobic digesters are also fully enclosed systems, but operate primarily under the action of anaerobic bacteria. They are most effectively used with wastes containing high organic loads, such as distillery waste (Melamane et al., 2007). Although they can be very effective, rapid, and an energy source (methane), as well as taking up relatively little space, they are complex to operate. The sludge generated can be used as a compost supplement.

Any of these systems may be supplemented with ozonation. Ozone is a powerful oxidant that can help degrade phenolics prior to pH adjustment. It can inactivate potential inhibitors of biological decomposition (Santos et al., 2003). Ozonation can also be used to sterilize effluent before discharge and facilitate particulate flocculation. In combination with a photocatalytic/photolytic reactor, ozonation increases the efficiency of oxygen demand reduction (Agustina et al., 2008).

Details of the species composition and microbial dynamics in any of these systems are still primitive. Water waste microbiology is as complicated as soil microbiology, where the inability to grow most inhabitants (individually on solid media) prevents traditional identification. Culture plates are frequently overgrown by common saprophytes, uninvolved in the complex ecosystem active in these habitats. Nonetheless, with the advent of DNA sequencing, some idea of the taxonomic status of the microbial flora is becoming clearer, including their enzymatic potentialities. In a recent study, 68 different bacterial denizens were partially categorized (Keyser et al., 2007).

Another aspect of wastewater microbiology that appears to have been insufficiently studied is the pathogen load of the treated effluent, notably grapevine viruses. This could be of considerable significance if the effluent water is used to irrigate vineyards.

Depending on the chemistry and solids content, the end product of secondary treatment may require treatment to adjust the pH or eliminate its inorganic nutrient load, notably if it is high in nitrogen or phosphorus. Sodium and potassium values also need to be checked. Potassium levels in winery wastewaters can reach 1000 mg K/liter (Arienzo et al., 2009). High salt contents are best resolved in the winery, by source reduction, than with tertiary treatment. Unadjusted, long-term application could result in decreasing the water permeability of the soil. Even at moderate values, salt presence should be calculated when determining if, when, and by how much to fertilize a vineyard. In addition, settling and a final filtration may be necessary to reduce particulate load, to permit its use for irrigation.

If the sources of waste effluent are separated, or even if they are not, not all wastewater may need to pass through all three treatment stages. It largely depends on chemical composition and intended end-use.