In red wines, the initial purplish tint has been associated with copigmentation. It fades as these complexes dissociate and freed anthocyanins oxidize or change their chromophoric status (McRae et al., 2012; see Fig. 6.8). Anthocyanins also progressively polymerize with tannins. Polymerization begins during fermentation, constituting about 25–60% of the anthocyanin content within a year (see Fig. 6.11). Polymerization is favored by the peroxidation of dihydroxyphenolics (primarily o-diphenols) to diquinones. These slowly polymerize through internal restructuring into oligomeric o-diphenols. These can undergo a further series of oxidation and restructuring reactions. These progressively generate increasingly large oligomeric and polymeric yellow to brown oxidized phenolics (tannins) (see Rose and Pilkington, 1989). Nevertheless, no consensus has been reached about the relative importance (or desirability) of the multiple potential reactions involved (see Alcalde-Eon et al., 2006; see the subsection ‘Color – Red Wines’ in Chapter 6).

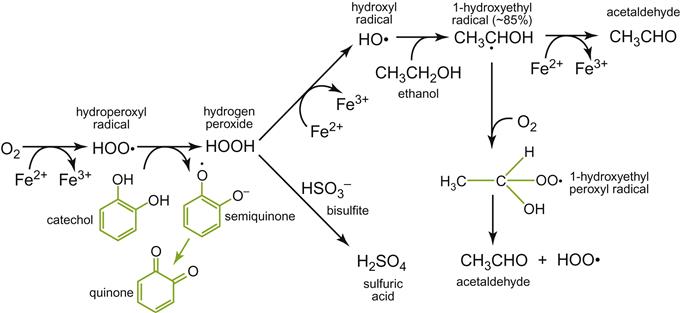

As o-diphenols oxidize, hydrogen peroxide is generated. It activates further oxidation reactions with other wine constituents, notably converting ethanol to acetaldehyde (Timberlake and Bridle, 1976), and presumably glycerol to glyceraldehyde and dihydroxyacetone (Laurie and Waterhouse, 2006). In addition, hydrogen peroxide may be consumed in Fenton-like reactions with phenolics (Walling and Johnson, 1975), requiring the catalytic action of iron and possibly copper or reactions leading to phenolic degradation, such as the conversion of gallic acid to muconic acid derivatives (Singleton, 1987).

Although some of the acetaldehyde produced in association with phenol oxidation enhances anthocyanin-proanthocyanidin polymerization, direct polymerization between these compounds also occurs under anaerobic, acid-catalyzed conditions. In addition, direct tannin polymerization occurs. Even though it occurs slowly, it occurs continuously. Thus, direct polymerization may be more significant than acetaldehyde-assisted polymerization that is most marked early in maturation.

Another source of phenolic polymerization involves the catalytic oxidation of tartaric acid to glyoxylic acid. This is activated in the presence of metallic ions, notably iron (Fulcrand et al., 1997). Glyoxylic acid binds catechins and possibly other phenolics into increasingly large polymers. The reaction can generate both colorless and yellow polyphenolics.

Although anthocyanin polymerization is critical to color stabilization, additional mechanisms are involved. One entails a reaction between yeast metabolites, such as pyruvic acid and anthocyanins (Fulcrand et al., 1998). Subsequent structural rearrangement and dehydration generate tawny colored products. These are more stable to sulfur dioxide, high temperature, and pH values above 3.5 than the original anthocyanin.

The origin of the color shift in rosé wines appears not to have been specifically studied. Presumably, it is related to the oxidative browning of free anthocyanins, and the degradation of their self-association and copigment complexes. Studies by Hernández et al. (2011) have shown a relatively consistent progression from raspberry to strawberry to red currant to salmon over about 18 months. The duration and rapidity of these transformations depend on the individual wine and its varietal composition.

The color shift in white wines has traditionally been ascribed to the accumulation of chromophoric carbonyl compounds. In addition, the slow oxidation and polymerization of grape and oak phenolics are undoubtedly involved. For example, oxidized caffeic acid has a golden color, whereas flavonoid polymers donate a brownish countenance. Nonetheless, it is likely considerably more complex than this. It probably involves structural modification of existing pigments, or de novo synthesis by processes such as the oxidation of ascorbic acid (vitamin C); metal ion-induced structural modifications to galacturonic acid; ketosamine condensation products produced by Maillard reactions (between reducing sugars and amino acids); and sugar caramelization, generating products such as furan-2-aldehyde. The latter two reaction types are particularly likely in sweet wines. Some of these reactions may also participate in the development of a bottle-bouquet. Sulfur dioxide can retard or prevent most of these reactions.

Taste and Mouth-Feel Sensations

During aging, residual glucose and fructose may react with other compounds and undergo structural rearrangements. Nevertheless, these reactions do not in themselves appear to occur to a degree sufficient to affect perceptible sweetness. The hydrolytic breakdown of acetate esters may, however, indirectly result in a loss of perceived sweetness. This could arise from the loss of their fruity odor, which the cerebral frontal cortex learns to associate with sweetness (see Prescott, 2004).

Age-related modifications to acidity may result in a small, but perceptible, reduction in perceived sourness. For example, esterification of acids, such as tartaric acid, removes carboxyl groups. Upwards of 1.5 g/liter of ethyl bitartrate may form during aging (Edwards et al., 1985). Slow deacidification can also result from the isomerization of tartaric acid – from the natural L- to the D-form. The resulting racemic mixture is less soluble than the L-form. This is one of the causes of tartrate instability. Isomerization also results in forming racemic mixtures of L- and D-amino acids (Chaves das Neves et al., 1990). The potential significance of the toxicity of the D-amino acids is unknown. It is likely insignificant due to wine’s small amino acid content.

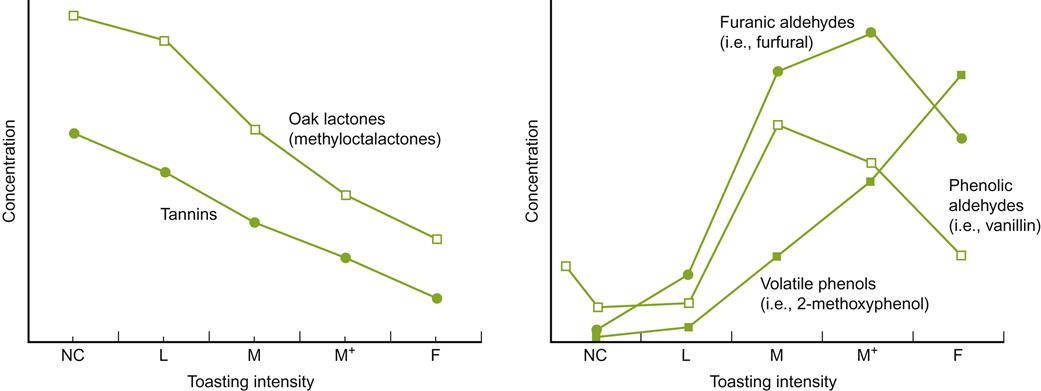

The most significant gustatory changes during aging affect the bitter and astringent sensations of red wines (McRae et al., 2010). Nonetheless, this appears not to be associated with any clear trends in a reduction in tannin content (McRae et al., 2012). The study is unique in investigating several series of red wines over a span of 30 and 50 years. The best understood of these reactions is the polymerization of proanthocyanidins, both with themselves, as well as with anthocyanins, proteins, and polysaccharides. Autopolymerization tends to induce a progressive decline in bitterness and astringency, due to chemical reactivity changes as well as precipitation. Acetaldehyde-induced polymerization, which reduces solubility, probably explains additional astringency loss during aging (Matsuo and Itoo, 1982). However, in the early stages of polymerization, there may be an increase in astringency. This results from the increased ability of medium- versus large-size tannins to bind with proteins in the mouth. The binding of tannins with polysaccharides, peptides, or proteins in the wine leads to a further reduction in bitter, astringent sensations. In addition, condensed tannins may slowly depolymerize during aging (Vidal et al., 2002), potentially increasing bitterness. Similarly, the breakdown of hydrolyzable tannins (primarily from oak cooperage) may reduce astringency, but enhance bitterness. There is also evidence that suggests that bitterness arises more from nonflavonoids (ethyl esters of hydroxybenzoic and hydroxycinnamic acids) than flavonoids (Hufnagel and Hofmann, 2008).

Due to our poor understanding of the complex dynamics of these multiple alterations in structure, it is currently impossible to clearly explain, in chemical terms, the age-related modifications in bitterness and astringency experienced by consumers.

Fragrance

Whereas studies on aging in red wines have concentrated primarily on color changes, most research on the aging of white wines has focused on fragrance modification. Flavor loss, especially in young white wines, has been primarily associated with alternations in ester content. Other known sources of reduced fragrance involve structural rearrangements in terpenes, thiols, and volatile phenols.

Loss or Modification of Aroma and Fermentation Bouquet

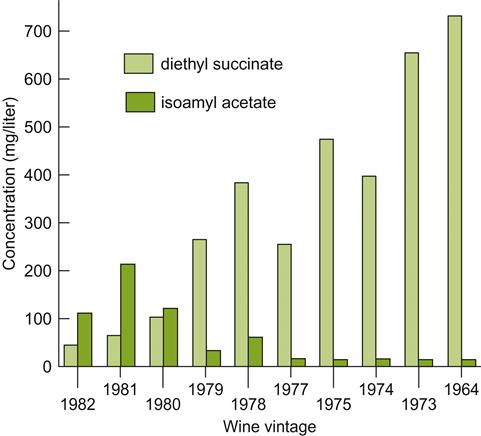

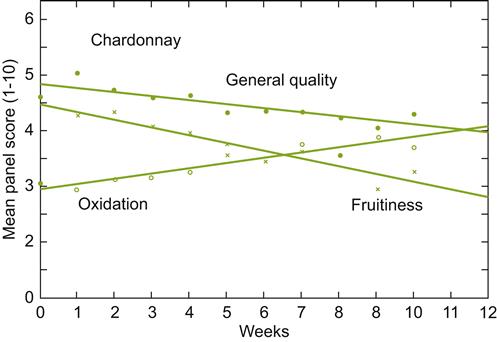

Esters produced during fermentation generate much of the fresh, fruity character of young white wines, and to a lesser degree red wines. The most significant appear to be acetic acid esters, formed with higher alcohols, such as isoamyl and isobutyl acetates. Because yeasts produce and release more of these than the equilibrium in wine permits, they tend to slowly hydrolyze back to their corresponding acids and alcohols during aging. Thus, the fruity aspect donated by these esters tends to fade with time (Fig. 8.28) (Gonzalez Viñas et al., 1996). Their hydrolysis occurs more rapidly at lower pH values and higher temperatures (Marais and Pool, 1980). For example, important esters, such as isoamyl and hexyl acetates, may decline by about 80% within 2 years at 30°C; hence the value of cool storage. Nevertheless, several esters remain above their detection threshold for several years. Some may even increase. For example, the headspace content of ethyl acetate can increase by a factor of 2.5 at 30°C (Marais and Pool, 1980). Regrettably, augmenting its sensory impact is not necessarily a favorable change.

Ester hydrolysis can be reduced by the addition of antioxidants, such as sulfur dioxide, glutathione, and phenolics, notably caffeic and gallic acids (Lambropoulos and Roussis, 2007). Sulfur dioxide also retards the loss of varietally important thiols, such as 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol (Blanchard et al., 2004) and 3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol (Nikolantonaki et al., 2010). In contrast, an increased concentration of catechins favors their oxidative degradation. Although sulfur dioxide may help preserve some desirable aromatics, its reaction with damascenone markedly reduces its impact on the fruity character of several wines (Daniel et al., 2004).

A second major class of aromatic esters is based on ethanol reacting with long-chain saturated fatty acids. The content of particular forms may decrease, remain stable, or increase during aging (Marais and Pool, 1980). Because they generally occur at lower concentrations than acetate esters, the high ethanol content of wine shifts the equilibrium toward esterification rather than the reverse. Hydrolytic rupture is also influenced by wine pH and storage temperature, as well as the molecular weight of the fatty acid moiety. Their sensory qualities are significantly influenced by the hydrocarbon chain length. Those with shorter hydrocarbon chains, such as butanoate, hexanoate, and octanoate ethyl esters, tend to possess a somewhat fruity character. As the hydrocarbon chain lengthens, the aromatic attributes become more soap-like, and finally lard-like.

A third group of esters, and eventually the most abundant, form slowly between ethanol and organic acids, such a tartaric, malic, lactic, citric, and succinic acids. Their content tends to increase with higher alcohol contents, lower pH values, and notably at higher temperatures (Marais and Pool, 1980; Shinohara and Shimizu, 1981). The synthesis of diethyl succinate is particularly marked (see Fig. 8.28). Both it and methyl succinate are thought to be of major significance in the fragrance development of muscadine wines (Lamikanra et al., 1996). However, most of these ethyl esters probably play little role in bouquet development, due to their low volatility and nondistinctive odors.

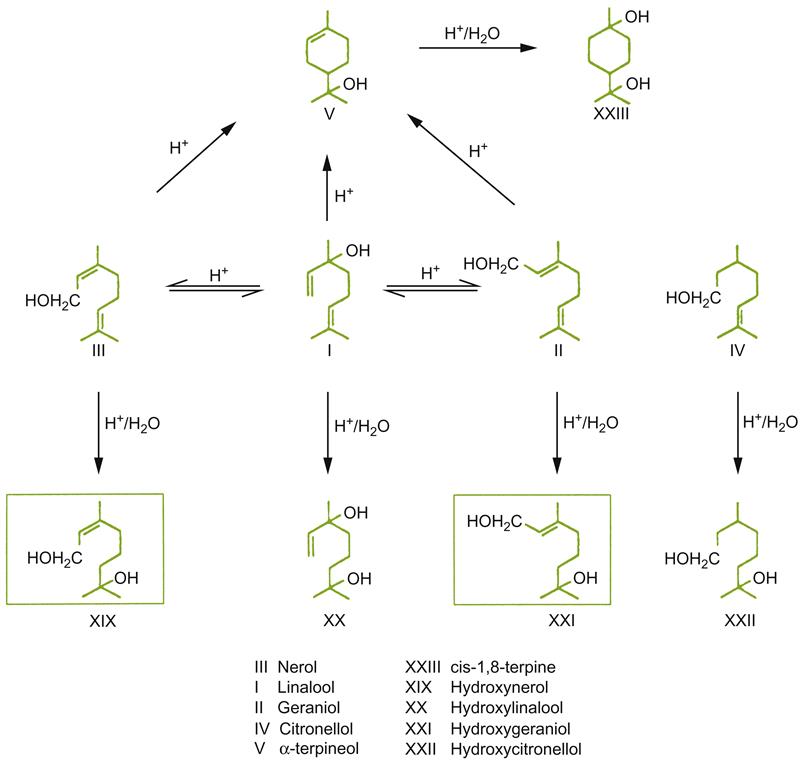

Another group of important flavorants that change during aging are terpenes. These are particularly important to the aroma of Muscat and related cultivars. Oxidation of terpenes results in a marked loss of varietal character in these varieties. During ripening, the concentration of monoterpenes in grapes tends to rise. At the same time, though, an increasing proportion becomes bound in nonvolatile glycosidic complexes. Theoretically, these should slowly break down under the acidic conditions of wine. Nonetheless, the typical observation is that the net concentration of fragrant monoterpene alcohols falls during aging. The decline in geraniol, linalool, and citronellol is especially marked. For example, the linalool content of Riesling wines can decrease by 80%, to below its detection threshold, within 3 years. This can result in a noticeable loss in floral character. In contrast, the concentrations of linalool oxides, nerol oxide, hotrienol, and α-terpineol increase. Figure 8.29 presents a proposed reaction scheme for changes in monoterpene alcohols during aging. Most of these derivatives have higher perception thresholds than their monoterpene progenitors. For example, linalool oxides have flavor thresholds in the 3000–5000 μg/liter range vs. 100 μg/liter for linalool (Rapp, 1988). Terpene oxides also have qualitatively different odors. For example, α-terpineol has a musty, pine-like odor, whereas its precursor linalool has a floral aspect. In addition, mixtures may have a qualitative fragrance different from their component compounds. Terpene-related heterocyclic oxygen compounds also develop during aging, but their sensory significance, if any, is unknown.

The role of norisoprenoids in aroma loss has been little studied. However, the concentration of the rose-like β-damascenone declines during aging (see Fig. 8.26). The content of other isoprenoid degradation products, such as theaspirane and ionene (a 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene isomer) also appears to decline.

Several volatile phenols, such as vinylphenol and vinylguaiacol, are partially converted to nonvolatile ethyoxyethylphenols during aging (Dugelay et al., 1993). At low concentrations, volatile phenols can enhance wine fragrance, but at higher levels they produce phenolic off-flavors. The concentration of important varietal aromatics, such as 2-phenylethanol, also declines during aging (see Fig. 8.26).

Another example of aroma loss involves the oxidation of thiol flavorants, for example 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol (3-MH) and 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol acetate (3-MHA) (Herbst-Johnstone et al., 2011). In Sauternes, similar and additional thiols, found in young versions, become undetectable within 2 years, with the exception of 3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol (Bailly et al., 2009).

In addition to the loss or modification of grape and yeast aromatics, new compounds are also generated. Some of these appear to be the result of oxidation. The best-known is acetaldehyde. However, the importance of acetaldehyde to the oxidized odor of table wines has come under question. Its distinctive odor is typically not detectable in table wines considered to be oxidized, nor does the free (volatile) concentration of acetaldehyde rise upon short-term, intentional oxidation (Singleton et al., 1979; Escudero et al., 2002). Although produced as an indirect by-product of o-diphenol oxidation, free acetaldehyde is rapidly consumed in reactions with other wine constituents. It is only in some fortified wines, notably sherries, that the odor of acetaldehyde is considered appropriate and expected. In contrast, the production of other aldehydes, notably furfural and hexanal, appears to be important, but in a negative way. They appear to participate in masking the wine’s natural fragrance. Exposure to high temperatures also generates additional compounds (Silva Ferreira et al., 2003). Descriptive terms used for these compounds relate more to those used to describe an aged bouquet than an oxidized odor. In addition, quinones generated during oxidation may react with amino acids. These reactions could potentially affect flavor by generating aldehydes and ketones in Strecker-type degradations.

Occasionally, red wines undergo a process termed premature aging. It tends to be associated with the development of a distinct prune/fig-like odor that masks other wine flavors. Pons et al. (2008) have associated this character with the accumulation of γ-nonalactone, β-damascenone, and especially 3-methyl-2,4-nonanedione. The latter has a marked prune/anise/hay-like aroma, with a perception threshold of about 6 ng/liter.

Although most studies on wine aroma loss have primarily involved white wines, some studies have involved rosé wines. Like most white wines, rosé wines lose much of their fruity character within 1–2 years. This is correlated with the loss of several volatile thiols (Murat et al., 2003; Murat, 2005). The principal compounds affected appear to be 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol (3-MH) and 3-mercaptohenyl acetate (3-MHA). The concentration of the former (3-MH) can decrease to half within the first year, while its acetate ester may be no longer detectable. This may relate to binding with oxidized phenolics (Nikolantonaki et al., 2012). The limited antioxidant properties of rosé wines may also help to explain why they tend to rapidly take on an orangish coloration (due to oxidation of their restricted anthocyanin content and limited formation of more stable anthocyanin-tannin polymers). Another compound involved in the fruity character of rosé wines is phenethyl acetate. The concentration of this fermentation by-product also declines quickly during aging, further explaining the typical short shelf-life of rosé wines.

Origin of a Bottle-Aged Bouquet

Terms occasionally used to describe an aged bouquet include ‘leather,’ ‘cigar box,’ and ‘truffle’ for red wines, and ‘sun-dried linen’ for white wines. Such terms are used almost universally, regardless of the wine’s varietal origin. Regrettably, the chemical basis of such terms is unknown.

Currently, four chemical groups are associated with the supplementation and/or generation of a bottle-aged bouquet. These include: constituents liberated by acid or enzymic hydrolysis from nonvolatile glycosidic conjugates; derivatives from norisoprenoid precursors and related diterpenes; modified carbohydrates; and reduced-sulfur compounds.

Many flavorants in grapes accumulate as glycosides. This is the basis for the glycosyl-glucose (G-G) analysis of grape quality. The slow liberation under acidic condition of terpenes from their glycosidic bonds may partially offset losses during aging. The release of varietally significant volatile thiols from cysteinyl and glutathionyl conjugates is another source of additional flavorants (Capone et al., 2010a). This may be the source of thiols that may accumulate during aging, for example phenylmethanethiol and ethyl 3-sulfanylpropionate (Tominaga et al., 2003). In addition, the generation of minor quantities of some monoterpene oxides, such as 2,6,6-trimethyl-2-vinyltetrahydropyran and the 2,2-dimethyl-5-(1-methylpropenyl)tetrahydrofuran isomers, may participate in the development of aspects such as a cineole-like fragrance in aged Riesling wines (Simpson and Miller, 1983).

Of isoprenoid degradation products, vitispirane and 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene (TDN) appear to be the most important in relation to an aged bouquet. The two isomers of vitispirane have qualitatively different odors. However, because they usually occur in concentrations at or below their detection thresholds, their sensory significance remains in doubt. In contrast, the concentration of TDN increases during aging, at least in Riesling wines (Rapp, 1998), to values above its threshold of ~20 ppb. Thus, it could play a meaningful role in bouquet development (Fig. 8.30). Because, by itself, TDN possesses a kerosene-like odor, it is often viewed as undesirable. Nonetheless, it could contribute to the pine/petrol aspect often expected in aged Riesling wines. TDN also has been detected in red wines.

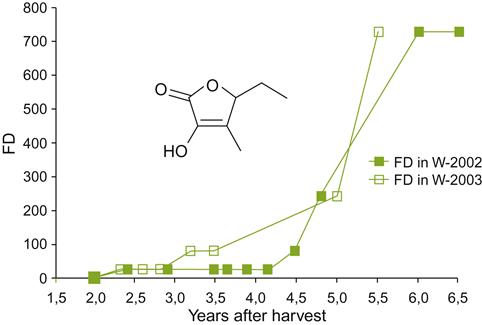

In aged Sauternes, some of the distinctive compounds detected in young versions are still present after several years. However, other compounds, such as γ-decalactone and abhexon (5-ethyl-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-2(5H)furanone), increase in concentration (Fig. 8.31). These are associated with apricot and honey-like odors, typically detected in aged botrytized wines. This suggests that these compounds may play a significant role in bouquet development in Sauternes.

Carbohydrate degradation occurs rapidly during the heating of wines such as madeira and baked sherries. Similar acid-catalyzed dehydration reactions also occur, but much more slowly at cellar temperatures. For example, the caramel-like 2-furfural can show a marked increase during aging (Table 8.2). The sensory significance of other decomposition products, such as 2-acetylfuran, ethyl 2-furoate, 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde, 2-formylpyrrole, and levulinic acid is unknown. The fruity, slightly pungent ethyl ether, 2-(ethoxymethyl)furan, has been found to form during aging in Sangiovese wines (Bertuccioli and Viani, 1976). This suggests that etherification of Maillard-generated alcohols may play a role in the development of aged bouquets.

Table 8.2

Changes in aroma composition from carbohydrate decomposition during aging of a Riesling winea

| Year | ||||||

| Substance from carbohydrate degradation | 1982 | 1978 | 1973 | 1964 | 1976 (frozen) | 1976 (cellar stored) |

| 2-Furfural | 4.1 | 13.9 | 39.1 | 44.6 | 2.2 | 27.1 |

| 2-Acetylfuran | – | – | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Furan-2-carbonic acid ethyl ester | 0.4 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 2.0 |

| 2-Formylpyrrole | – | 2.4 | 7.5 | 5.2 | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) | – | – | 1.0 | 2.2 | – | 0.5 |

aRelative peak height on gas chromatogram (mm).

Source: Data from Rapp and Güntert (1986).

The concentration of reduced-sulfur compounds also changes during aging. Of these, the most significant may be dimethyl sulfide. Its accumulation has occasionally been correlated with the development of a desirable aged bouquet. Spedding and Raut (1982) found that the addition of 20 mg/liter dimethyl sulfide (to wines already containing 8–15 mg/liter dimethyl sulfide) enhanced the wine’s flavor score. Higher concentrations (≥40 mg/liter) were considered detrimental. Occasionally, the production of dimethyl sulfide is so marked that, after several months, its presence can mask the varietal character (Rapp and Marais, 1993). Dimethyl sulfide has also been correlated with increased flavor complexity, and the donation of truffle and black olive notes (Segurel et al., 2004). Its accumulation in white wines may be a negative feature, but dimethyl sulfide may contribute to a desired aged bouquet in older red wines. The divergent affects may simply reflect the differing expectations consumers have for young white wines versus those for aged red wines, as well as the aromatic background in which dimethly sulfide appears.

Oak may also be a source of aromatics that contribute to an aged bouquet, for example 4-ethylphenol, 2- methoxy-4-ethylphenol, 2-furaldehyde, and 5-butyl-4-methyldihydrofuran-2(3H)-one (whisky lactone) (Pérez- Prieto et al., 2003a; Fernandez de Simon et al., 2006).

Additional Changes

Although the positive attributes of fragrance may increase, decrease, or change in quality during aging, most off-odors are not known to diminish significantly. Exceptions include hydrogen sulfide and vinylphenols. Hydrogen sulfide tends to oxidize, and acid-catalyzed reactions between ethanol and 4-vinylphenol and 4-vinylguaiacol generate 4-(1-ethoxyethyl)-phenol and 4-(1-ethoxyethyl)-guaiacol, respectively (Dugelay et al., 1995). The latter by-products have little if any influence on wine flavor.

A number of age-related changes develop in sherries that generally do not occur in table wines. Notable are increases in the concentrations of aldehydes and acetals. These develop under the oxidizing conditions prevalent during sherry maturation. Similar events also occur in the aging of wood ports, where acetaldehyde reacts with glycerol generating several heterocyclic acetals (da Silva Ferreira et al., 2002). These accumulate to concentrations that could contribute to the sweet, aged bouquet of wood ports. In table wines, the aldehyde content generally declines after bottling. Consequently, aldehyde-derived acetals do not accumulate during aging. An exception involved Tokaji Aszú wines during the Communist era (Schreier et al., 1976). During that time period the wines were often exposed to oxidizing conditions during maturation.

Structural rearrangements in the major fixed acids found in wine occur during aging. For example, decarboxylation can convert tartaric acid to oxalic acid and citric acid to citramalic acid. The sensory significance of these changes, if any, is unknown. Another, presumably inconsequential, modification involves a marked increase in the concentration of abscisic acid. Although abscisic acid is important as a growth regulator in higher plants, its generation in wine is probably purely coincidental.

In contrast to the examples noted above, the concentrations of several major chemical groups are little affected by aging. Those essentially unaffected by aging include higher alcohols, their esters, and lactones.

Accelerated Aging

In the 1950s, there was considerable interest in accelerated aging (Singleton, 1962). Subsequently, activity on the topic has waned. More recent experiments indicate that exposure to 45°C for 20 days could produce changes in Chardonnay and Sémillon wines resembling those engendered by several years in-bottle aging (Francis et al., 1993). In addition, experiments involving alternating current (600 V/cm for 3 min) reportedly improve the balance and mouth-feel of Cabernet Sauvignon wines (Zeng et al., 2008). There was also a reduction in aldehyde and higher alcohol contents, and slight increases in esters. Nonetheless, such treatments generally are not associated with the desired complexity ascribed to traditionally cellared wines.

Factors Affecting Aging

Oxygen

Essentially, all wines are exposed to oxygen during bottling. This may arise as the wine is transferred from storage cooperage to the bottling facility, during bottle filling (air that may be present in the bottle and remaining in the headspace), or shortly thereafter (dissolved oxygen escapes from the lumens of cork cells). Most of the oxygen is quickly consumed in reactions with phenolics and sulfur dioxide, resulting in the oxygen level soon falling to near zero. Further oxygen uptake tends to be slow and minimal (directly through the stopper or between the stopper and the neck). It is typically consumed faster than it enters. Thus, except where oxygen uptake occurs through serious faults in the cork (physical cavities or creases generated during cork insertion) or deficits in oxygen permeability (some cork substitutes), rapid oxidative damage of the wine is typically negligible. Although many reactions are known, their stoichiometry, rates under wine conditions, and sensory significance are poorly understood.

Some wines are more susceptible to oxidation than others, notably white and rosé wines, with the wines of some cultivars being particularly susceptible to oxidative browning. Precisely why is still unclear, but it likely relates to variations in the concentration and types of their flavonoid and nonflavonoid phenolics. The most prevalent phenolic in white wines is caftaric acid (the ester of caffeic and tartaric acids). After hydrolysis, caffeic acid (an o-diphenol) can undergo significant oxidation, generating browning (Cillers and Singleton, 1990). This results from polymerization with other phenolics. Red grape varieties particularly susceptible to oxidation, such as Grenache, contain high concentrations of caftaric acid and its derivatives. Although the concentration of catechins is typically low in white wines (~30–50 mg/liter), their presence is often closely related to in-bottle browning (Simpson, 1982; Salacha et al., 2008). Another important factor affecting oxidation is pH. As the pH rises, the proportion of phenols in the highly reactive phenolate state increases, enhancing potential oxidation. Finally, the reactivity of the various anthocyanins, their structure, and condensation with tannins greatly affect oxidative susceptibility.

Oxygen has traditionally been viewed as detrimental to bouquet development. Thus, considerable effort has been expended in protecting bottled wine from oxygen uptake. To assure that bottled wine remains essentially under anaerobic conditions, good-quality closures (corks or pilfer-proof screw caps) are typically used, and oxygen exposure during bottling held to a minimum. Sulfur dioxide is typically added at bottling to further retard oxidative browning, notably with white wine. Ascorbic acid has frequently been added for the same purpose. However, its long-term benefits are controversial, seeming to vary with the cultivar and/or oak exposure (Skouroumounis et al., 2005a,b). In addition, the debate about natural, synthetic, and screw cap closures has exposed our ignorance about the detriment/benefit consequences of minimal, but protracted, oxygen uptake on in-bottle wine development.

Browning and o-diphenol autooxidation (Fig. 8.32), and its associated production of acetaldehyde, have normally been considered the principal consequences of oxidation. Although important in the long-term, little if any increase in acetaldehyde content has been detectable after oxygen saturation. This apparent anomaly may relate to the short duration of the oxidation period (Escudero et al., 2002), rapid consumption of acetaldehyde in other reactions, or the low concentration of o-diphenols in white wines. The principal descriptors for treated wines in the Escudero study were ‘cooked vegetables’ and ‘pungent.’ These attributes were correlated with the presence of furfural and hexanal, respectively. Other aromatic constituents potentially involved were 2-nonenal, 2-octenal, and benzaldehyde. Methional (mercaptopropionaldehyde) was associated with a cooked cabbage odor (Escudero et al., 2000). Other studies have correlated oxidative odors with the production of methional (3-(methylthio)propionaldehyde), phenylacetaldehyde, 4,5-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-2(5H)-furanone (sotolon), and trimethyl-1,5-dihydronaphthalene (TDN), particularly at high (45°C) temperatures and/or low pH values (Silva Ferreira et al., 2003). These compounds were produced in low concentrations at 15°C, even after several weeks and several oxygen saturations. It is debatable whether some of the attributes generated during purposeful oxidation, such as honey-like (phenylacetaldehyde), hay and wood (eugenol) attributes, are typical of an aged bouquet or are simply oxidation off-odors.

Although white wines have a lower phenolic content than red wines, they are more susceptible to oxidative browning. This apparent contradiction results from the ability of many wine phenolics to consume large amounts of oxygen, retarding the undesirable sensory consequences of oxidation. In addition, the paler color and milder flavor of white wines make the consequences of oxidation evident earlier. Factors such as high pH, cultivation in warm climates, and fungal infection significantly increase the risk of oxidative browning.

Oxidative browning is universally considered undesirable by wine professionals. Despite this, there is little evidence that consumers are similarly concerned or as critical about the visual consequences of oxidative browning. In most cases, unless oxidation is extensive, browning results only in the development of a yellowish or golden tint. Development of obvious browning may require considerable oxygen uptake (Fig. 8.33). In some cultivars, such as Sauvignon blanc, in-bottle oxidation may initially lead to the development of a pinkish blush (pinking) (Singleton et al., 1979). Although disconcerting to the professional, whether the average consumer is in the least influenced by or even notices pinking appears not to have been assessed.

Browning is usually measured by assessing increased absorption at 420 nm. Nevertheless, this may be woefully inadequate, due to the diverse nature of the pigments involved (Skouroumounis et al., 2005a; Pedretti et al., 2007).

Although much of the attention concerning in-bottle oxidation relates to browning, and the formation of oxidative odors, oxidation may provoke other forms of quality deterioration. This is particularly noticeable with cultivars dependent on monoterpenes for their varietal character. Their oxidation products are still volatile, but they have higher sensory thresholds and possess less appealing odors. Loss of fruitiness also occurs in cultivars not dependent on terpenes for their varietal aroma. An example is the oxidation of varietal thiol flavorants to disulfides. In addition, some ethyl and acetate ester contents decrease rapidly on exposure to air (Roussis et al., 2005).

In bottled wine, oxygen ingress probably involves diffusion next to or through the cork. Initially, though, most oxygen uptake probably originates from cellular voids in the cork, and any air trapped in the headspace during filling. Additional factors affecting oxidation include the wine’s pH, tannin, copper, and iron contents. Although oxidation results in the formation of acetaldehyde, its rapid binding with other wine constituents normally keeps its free volatile content below the detection threshold. Only after considerable oxidation is acetaldehyde accumulation likely to contribute to an oxidized odor.

One of the principal problems in limiting in-bottle browning is determining the wine’s oxidative susceptibility. New laboratory techniques may help in this regard (Oliveira et al., 2002; Palma and Barroso, 2002). They may permit a better assessment of the degree of protection required.

In contrast to aging in table wines, limited oxygen exposure is often involved, if not required, in the maturation of most fortified wines. Depending on the style, they may be characterized by high concentrations of common wine constituents, or relatively unique by-products of oxidative aging. For example, sherries and similar wines are distinguished by the presence of acetaldehyde, acetals, and the lactone, sotolon. Sotolon is thought to be one of the distinctive compounds donating a rancio attribute to oxidized red and white sweet wines (Cutzach et al., 1999). The Vins Doux Naturels of Rousillon have also been characterized by the slow development of several unique ethyl esters (Schneider et al., 1998), notably ethyl pyroglutamate, ethyl 2-hydroxyglutarate, and 4-carbethoxy-γ-butryolactone. They possess honey, chocolate and coconut fragrances. Acetals commonly found in oxidatively aged sweet wines also include compounds such as furfural and 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural.

Temperature

To avoid loosening the cork seal, the bottle needs to be stored under relatively stable temperature conditions. Rapid temperature changes can generate sudden fluctuations in wine volume, putting pressure on the cork/neck seal. If sufficiently marked, or repeated, rupturing the cork seal may facilitate oxygen ingress. If the wine freezes, the volume increase can be sufficient to force the cork out of the bottle.

Temperature also directly influences the rate and direction of wine aging. In most instances, heat both speeds and may activate the reactions involved. Thus, cool storage (<10°C) extends retention of the fresh, fruity character of young wines. For example, the concentrations of fragrant acetate esters, such as isoamyl and hexyl acetates, were stable at 0°C, but rapidly hydrolyzed at 30°C (Marais and Pool, 1980; Marais, 1986). In contrast, esterification of the less aromatic ethyl and diethyl esters was enhanced at higher storage temperatures, but negligible at 0°C. Temperature also has a marked effect on the liberation of norisoprenoid aromatics from their glycosidic precursors (Leino et al., 1993). This may account for some of the increased concentration of TDN in Riesling wine aged at 30° versus 15°C (Marais et al., 1992), as well as the content and types of monoterpene alcohols found in aged wines (Rapp and Güntert, 1986). The conversion of norisoprenoid precursors to spiroesters, such as vitispirane and theaspirane, or to hydrocarbons such as TDN and ionene is suspected but unconfirmed. Exposure to heat also favors the degradation of carbohydrates to furfurals and pyrroles. Conversely, other age-related changes are accelerated at cold temperatures. The most well-known vinous example is the activation of potassium tartrate crystallization.

For most wines, prolonged exposure to high temperatures (≥40°C) rapidly induces quality deterioration. Carbohydrates undergo Maillard and thermal degradation reactions, turning brown and producing a baked (madeirized) flavor. Wines also tend to develop a sediment. Even temperatures as low as 30°C show detectable fragrance losses within a few months.

From the data available, it appears that traditional cellar temperatures (about 10°C) favor the retention of most fruit esters, while not excessively inhibiting other desirable aging reactions. Temperatures up to 20°C do not appear inimical to the sensory changes desired during aging, at least for red wines. Some of the changes that accrue under different storage temperatures are illustrated in Fig. 8.34.

Light

For traditional aging, wine should be stored in darkness whenever possible, or at the least protected from direct sunlight. It induces excessive heating, rapidly increasing wine volume and putting pressure on the cork. The heating also disrupts standard aging reactions, accelerating undesirable changes. In addition, exposure to near-ultraviolet and blue radiation can activate light-induced off-odors. The best-known reaction generates a shrimp- to skunky-like off-odor in champagne, termed light-struck (goût de lumière) (Carpentier and Maujean, 1981). It appears to be associated with the synthesis of several sulfur compounds, including dimethyl sulfide, dimethyl disulfide, and methyl mercaptan. This presumably involves the photodegradation of sulfur-containing amino acids by the activation of riboflavin. An additional light-struck phenomenon has been identified by D’Auria et al. (2003): 2-methylpropanol and a marked reduction in fruit ester content appear to be involved. The greater importance of these reactions in sparkling wines may be associated with increased volatilization associated with effervescence.

Additional factors, presumably implicated in light-induced off-odor production, include the relative concentrations of antioxidants, such as sulfur dioxide and glutathione, and metallic catalysts. Bottle glass transmissibility to ultraviolet and blue radiation, and the intensity and duration of exposure are also critical factors. Thus, it is not surprising that the observed effects of exposure treatments often differ. For example, sherries exposed to UV-visible light (xenon source) showed an increase in ester content (Benítez et al., 2003), whereas white and red table wines exposed to UV radiation (Mercury lamp) showed a marked decrease in ester content (Cellamare et al., 2009). With some ethyl esters there was an initial increase in red wines, but not in white wines. In addition, light exposure can promote the formation of copper casse (Joslyn and Lukton, 1956), and favor the browning of white wines (Maury et al., 2010). Even comparatively short exposure to fluorescent light can induce sensory changes in white wine (Dozon and Noble, 1989).

Vibration

Vibration is popularly considered to disrupt or accelerate aging, but there appears to be no evidence to support this view. In contrast, old claims concerning beneficial aspects of vibration probably refer to facilitated clarification rather than aging.

pH

Wine acidity and pH affect the rate as well as the chemical nature of changes that occur during aging. The best understood of these includes the effects of pH on red wine color and stability, and phenolic susceptibility to oxidation (the proportion in the phenolate state). pH also markedly affects the equilibrium between esters and their alcohol and acid precursors (Garofolo and Piracci, 1994).

Rejuvenation of Old Wines

Cuénat and Kobel (1987) proposed a process for rejuvenating wines that have lost their fresh character. It involves dilution of the affected wine with water. The water and the chemicals presumably involved in the development of the undesired aged character are subsequently removed by reverse osmosis. Ultrafiltration may have a similarly beneficial effect in rejuvenating old wines.

Aging Potential

Much has been made of a wine’s aging potential, or lack thereof. Despite this, wine critics often differ considerably in their advice. Habituation is likely to play a central role in these differences. Even if wine storage conditions were constant, individual perception is highly variable and can be markedly influenced by the tasting conditions (see Chapter 11). In addition, for the majority of consumers aging potential appears to have no significance, most wines being consumed within days, if not hours, of purchase.

For most aficionados, wine potential and how long a wine should be aged are a source of endless conversation. Nonetheless, they primarily depend on personal preference. If consumers prefer their wine possessing a fresh fruity fragrance and/or showing a distinctive varietal or stylistic character, aging potential is of little concern. The wine should be drunk within a few years of bottling. This also applies to consumers who enjoy (or are relatively insensitive to) the astringent taste of most young red wines. Preferring coffee strong and black probably indicates a preference for (or ability to enjoy) strongly astringent red wines. Contrariwise, a preference for coffee or tea with sugar and cream may indicate a predilection for more mature versions, with more mellow subtle flavors. Such a consumer may also prefer white wines, or reds made from Pinot noir; the latter is rarely astringent. Besides habituation, these differences in preference may be based on inherent variations in sensory acuity – hypertasters detecting and preferring subtler flavors, whereas hypotasters only detecting and preferring stronger sensations. During aging, if a pleasant bouquet replaces the diminishing varietal character, the wine definitely has aging potential. Whether it is worth the wait depends on one’s preference, patience, or wealth.

As noted above, the most significant factor normally affecting the rate of wine aging is storage temperature. When people ask at what temperature wine should be stored, I half-facetiously ask them how long they expect to live. If the response is at least another 20 years, it is safe to store your best wines at 10°C (typically viewed as ideal). Although no empirical equation currently predicts how temperature affects maturation rate, the general rule of thumb for many chemical reactions would suggest that aging probably doubles with each 10°C increase in temperature. Above 30°C, aging not only occurs much more rapidly, but its nature changes. To most professionals, these changes are not for the better. Even short exposures to high temperatures (≥30°C) can provoke significant changes in the concentration of esters (Fig. 8.35).

Summary

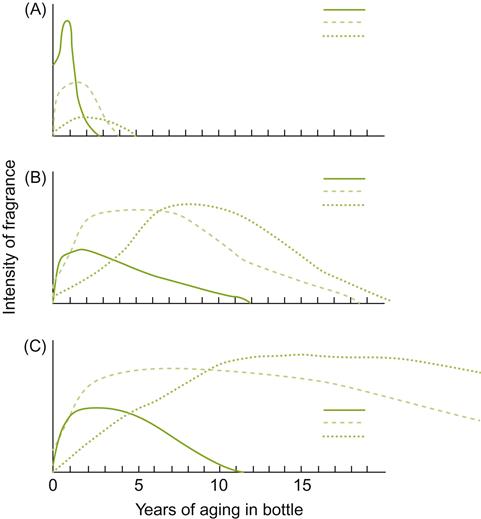

To varying degrees, aging involves multiple chemical reactions. These include oxidation (with or without the direct action of oxygen), reduction, hydrolysis, polymerization, structural rearrangement, equilibrium adjustment, volatilization, yeast autolysis, and oak extraction/absorption. These produce, to varying degrees, initial improvements in the subjective appreciation of a wine’s character. Subsequently, changes tend to reduce the fermentation and varietal attributes of the wine’s fragrance. If these are simultaneously replaced by flavors that contribute to complexity, by adding subtle fragrances and gustatory properties, then the wine’s overall character is considered to be enhanced. If a desirable aged bouquet does not supplement the loss of the wine’s youthful fragrance, then the wine will have a comparatively short shelf-life (i.e., limited aging potential). Red wines generally possess longer shelf-lives than white wines, with the exception of sweet botrytized wines and fortified wines. Figure 8.36 presents a hypothetical representation of the changes in fragrance during aging of several different wine styles.

Shelf-Life

The concept of shelf-life relative to wine is much more difficult to define than for most other commercial beverages or foods. The latter can reasonably be given a ‘best before’ indication. Other than Beaujolais nouveau, this is essentially impossible. Most white wines are generally recommended to be consumed within the first year or two of production, and most red wines within 5 years. However, these are only general guidelines, and highly dependent of preferences and storage conditions. This partially reflects the ambiguity as to what constitutes quality and deterioration in wine. This, in itself, is a reflection of experience and expectation on the part of the consumer. Is the wine’s youthful varietal fruitiness desired, or the more subtle nonvarietal attributes that develop with age? The relative weightings given to these extremes often vary with the type of wine and its presumed prestige. Everyday (inexpensive) wines are (correctly or incorrectly) consumed young and stress fresh fruity aromas and fragrances. In contrast, premium (expensive) wines are expected to have long aging potential and be better after several to many years of in-bottle aging. The complex subtle attributes of the latter provide the connoisseur with most of the intrigue associated with these wines. Its age also provides an element of exclusivity, available only to those who age wine (or are sufficiently well-off to purchase old wine). Because there are few objective criteria by which to define aging potential, it is far easier to explain shelf-life loss than its retention.

One of the crucial elements in wine shelf-life is the production method. As noted above, Beaujolais nouveau is acknowledged to have a very short shelf-life, usually considered to be 6 months to 1 year. It is normally considered best on arrival, about 1 month to 6 weeks after production. In contrast, premium wines are usually aged several years in the winery before release. Although consumable upon purchase, the wines are often ‘closed in’ and rough in texture. It is normally anticipated that they will be aged for several to many years before they reach their optimum. This period consists of a plateau, during which the varietal aroma begins to fade, to be replaced by a subtle, intriguing, aged bouquet. Only after several decades are such wines expected to lose their fragrance and reach the end of their shelf-life. Where along this path the wine is ‘best’ depends on the person providing the advice. Relative to expensive Bordeaux wines, French authorities seem to side on earlier consumption, British experts tend to prefer extended aging, whereas American commentators tend to be in the middle, but closer to the French view. In addition, flavors considered a fault in the majority of wines may be accepted or even highly regarded in a premium wine. Examples are the ethyl acetate attribute frequently found in renowned Sauternes, or the barnyardy (‘Brett’) character of some famous Rhône wines.

Opinion on when to consume sparkling and fortified wines also varies (or used to). Most current recommendations suggest that sparkling wines should be consumed shortly after purchase, while they retain their full carbon dioxide surcharge. It is estimated that sparkling wines lose about 5% of their CO2 per year (see Fig. 9.34). Nonetheless, a view once held by aficionados in Britain considered that champagne was at its optimum when it was sufficiently aged to have lost all, or most of, its sparkle. Experts on fino sherry comment that it is so short-lived, once bottled, that it only expresses its true attributes in Spain. If so, most consumers of fino sherry are probably habituated to the wine past its prime (and shelf-life). In contrast, oloroso sherries are considered to retain their optimal attributes for decades, and for months after being opened. Thus, shelf-life is an ill-defined attribute, depending more on expectation than any particular feature, and only typically applicable to wines intended to be consumed young.

Another feature that distinguishes the concept of wine shelf-life, versus other beverages, is cellar aging; this involves the purchaser in the retention and development of the wine. How the wine develops is thus partially under the control and direction of the consumer. Even other products expected to improve upon aging, such as some cheeses and balsamic vinegars, are sold in a state considered optimal for consumption (and not recommended or intended to be further aged by the purchaser).

As briefly noted, production style has a distinct influence on flavor protection and the avoidance of off-flavor development. Prolonged skin contact not only extracts more aromatics, but also more natural antioxidants. These favor prolonged shelf-life. The disadvantage of prolonged skin contact during fermentation is the extended aging frequently required for the wine to express its potential. Other winemaking decisions, such as fermentation temperature and yeast strain, also significantly influence the wine’s character and potential shelf-life. Maturation in oak, for example, not only adds its own distinctive flavors, but also supplies additional antioxidants as well as slight oxidation that favor color stability in red wines. Grape quality is also an essential element. This is normally interpreted as fruit that is fully ripe (maximal flavor potential, but retaining adequate acidity), uniform maturity (absent of partially or overripe grapes), free of extraneous material (MOG), and devoid of damage or disease (except noble-rotted grapes in botrytized wine production). Grape quality is in its turn a reflection of the characteristics of the soil and atmospheric climate. Cultivation at the cooler extremities of a cultivar’s range is usually viewed as ideal for both wine quality and shelf-life. This is commonly envisioned as putting the vine under stress. In reality, it probably more reflects restricted vegetative vigor, so that vine capacity can be more effectively directed toward fruit maturation and lower pH. Cool climates also once had the advantage of reducing the likelihood of wines becoming stuck due to overheating during fermentation. Cool cellar temperatures during maturation also favored natural clarification and microbial control. In these latter aspects, modern winemaking facilities have leveled the playing field between warmer and cooler grape-growing regions.

After purchase, shelf-life is primarily a function of storage conditions. The cooler and more uniform the storage temperature, the slower the wine ages and the longer its shelf-life. Avoidance of light exposure, especially direct sunlight, is crucial for prolonging shelf-life. Beyond these aspects, maintaining the bottle in a position to keep the cork moist, so that it retains its resilience, is critical to limiting oxygen uptake. Storage in an aromatically neutral environment is also important. Aromatic compounds, being fat soluble, can be absorbed into and potentially diffuse through the cork, contaminating the wine. Screw caps are the most consistently impermeable of closures, avoiding the inherent variability in a natural product such as cork.

One of the favorite pastimes of wine aficionados and critics alike is postulating on a wine’s aging potential (partially equivalent to shelf-life). This is usually based on experience, speculation, and wine prestige. More objective and quantitative, but less consumer applicable, are non-destructive in situ methods. These include nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and spectroscopy. NMR has the potential to quantify certain wine constituents indicating, for example, the presence of spoilage amounts of acetic acid (Weekley et al., 2003) and acetaldehyde (Sobieski et al., 2006). Due to cost, it is only applicable to assessing the potential quality of rare wines sold at auction. Spectroscopy is more affordable and available but is currently limited to assessing oxidative browning (absorption at 420 nm) (Skouroumounis et al., 2003), and total and free sulfur dioxide contents (Cozzolino et al., 2007). It is most applicable to wine in clear flint glass. Amber and antique green glass absorb intensely in the 420 nm spectral zone. Thus, absorption at 540 nm alone, or 540 nm and 600 nm, respectively, might be possible as substitute spectral bands. For wine bottled in glass of other colors, empty versions might act as acceptable standards.

For additional information on the shelf-life of wines see Reeves and Malcolm (2009) and Jackson (2011).

Oak and Cooperage

Barrel production probably evolved out of the skills involved in making wooden buckets and tanks. The innovations necessary were those required to bend and shape the staves to form watertight joints. These may have been adopted from techniques used in boat construction.

Possibly the oldest illustration of a barrel is found in the tomb of Hesi-Re (ca. 2630–2611 B.C.) (Quibell, 1913). It shows a wooden barrel produced from beveled planks, held together by bent wooden hoops. It apparently was used as a corn measure. A painting in the tomb of Rekhmire in Thebes (ca. 1400 B.C.) also shows what appear to be barrels, one with straight sides and the other with curved ends (Davies, 1935). Other illustrations of ancient barrels, or their precursors, are shown in Kilby (1971).

Herodotus (ca. 485–425 B.C.) reports that wine was transported down the Euphrates from Armenia in palm-wood containers. There is no indication whether they had straight or curved sides. Due to the porosity of the wood, they presumably were sealed, possibly with pitch. Unequivocal written and archaeological evidence of wooden cooperage, with hoops, and used for wine storage/transport, appear only in Imperial Roman times (Plate 8.3). Pliny the Elder (23–79 A.D.) notes that wine was stored in wooden vessels with hoops north of the Alps (Historia Naturalis 14.27). Clay dolia (Plate 8.4) were the principal wine fermentation and storage vessels south of the Alps. By at least the fourth century A.D., barrel use seems to have spread into Italy. In his Opus Agriculturae (1.18), Palladius describes a press house where the juice from pressed grapes, in excess of what could be placed in sunken dolia, was collected in barrels. Presumably the extra juice was also fermented therein.

Roman barrels were typically longer and thinner than barrels today. They possessed an average diameter/length ratio of about 1:3, in contrast to the more typical, current standard of 1:1.4. Examples have been excavated throughout Europe (Ulbert, 1959) and in England (St John Hope and Fox, 1898). Possibly the most well-known illustration appears in the Bayeux Tapestry (Plate 8.5), chronicling the Norman invasion of England in 1066. Barrels of modern dimensions became standard in the early 1500s. Nevertheless, barrels possessing modern attributes were produced earlier (Laubenheimer, 1990).

Oak has been used in cooperage construction since at least Roman times. Although other types of wood have been used throughout this period, their use has largely been limited to the construction of large storage vessels or fermentors. In Europe, chestnut (Castanea sativa) and acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia) were employed for these purposes. A comparison of their properties, as well as those of cherry (Prunus avium) and mulberry (Morus alba and M. nigra), is provided in De Rosso et al. (2009). However, their use, along with oak, has largely been supplanted by inert materials. Similarly, the former use of wooden barrels as the primary container for transporting wine has been superceded by the glass bottle. Thus, oak cooperage is now principally restricted to the maturation (and occasionally fermentation) of wine. It is particularly popular in the maturation of premium wines. The flavor and occasional slight oxidation provided by in-barrel maturation are often considered to enhance the character of wines with distinctive varietal aromas.

Oak Species and Wood Properties

The woods currently preferred in cooperage production are all members of the white oak section of Quercus. They not only possess the properties required for tight (leak-proof) cooperage, but their traditional use has led to an appreciation of (or habituation to) their subtle fragrance. Other woods have either undesirable structural or aromatic attributes, or have been studied insufficiently to establish their applicability to barrel construction.

Oak wood, used in cooperage construction, comes primarily from Quercus alba, Q. robur, and Q. sessilis. Q. alba and a series of six related white oaks (Q. bicolor, Q. lyrata, Q. macrocarpa, Q. muehlenbergii, Q. prinus, and Q. stelata) constitute the oaks employed in the construction of American oak cooperage. Of these, Q. alba provides about 45% of the white oak lumber harvested in North America. It also has the widest distribution of all American white oaks (Fig. 8.37C), and the size and structure preferred for select cooperage oak. In Oregon, wood from Q. garryanna is a new source of oak flavors.

In Europe, Quercus robur (Q. pedunculata) and Q. sessilis (Q. petraea, Q. sessiliflora) constitute the primary oak species employed in cooperage production. Nonetheless, there is interest in the use of the extensive tracts of Q. pyrenaica in Spain. It has distinctive attributes, characterized as partially between those of American and standard (French) European oaks (Fig. 8.38).

Although Quercus robur and Q. sessilis are not genetically isolated (infertile), and show considerable morphologic variability, species identification is generally possible only using a combination of features, including leaf and acorn morphology. Differences in chemical composition exist, with Q. sessilis tending to possess considerably higher levels of extractable aromatic compounds (e.g., oak lactones, eugenol, and vanillin), but lower concentrations of ellagitannins, ellagic acid, and dry extract than Q. robur (Doussot et al., 2000). Nonetheless, individual variation is too extensive to permit unequivocal species identification based purely on chemical analysis (Mosedale et al., 1998). The same difficulty exists using wood anatomy (Feuillat et al., 1997).

Both species occur sympatrically throughout much of Europe (Fig. 8.37A,B), with trees growing for several hundred years. Quercus robur does better on deep, rich, moist soils of large river valleys and damp lowlands, whereas Q. sessilis prefers drier, shallow, hillside soils. Nevertheless, species distribution does not necessarily reflect these preferences. Q. robur can quickly establish itself in sunlit areas, but it is slowly replaced by the more shade-tolerant Q. sessilis. In addition, nonselective acorn collection, used in silvicultural plantings, has tended to increase the proportion of Q. robur. It is more productive in acorn production.

Staves produced from different American white oak species are almost indistinguishable to the naked eye. The same is true for the two important white oak species in Europe. They can be differentiated only with difficulty, and then with certainty solely with the use of a microscope. Genetic and environmental factors often blur morphologic differences (Fletcher, 1978). That Q. robur is often considered to possess a coarser grain (more summer wood and larger growth rings) compared with the finer grain of Q. sessilis probably reflects as much the growth conditions favored by the two species as genetic factors.

In North America, most of the oak used in barrel construction comes from Kentucky, Missouri, Arkansas, and Michigan. There has been little tendency to separate or distinguish oak coming from different states, sites, or species. In contrast, designation by provenance is traditional in Europe. Geographic designation may denote country of origin (e.g., French, German, Russian), region (e.g., Slovenian, Limousin), political district (e.g., Vosges, Allier), or forest (e.g., Nevers, Tronçais) (Fig. 8.39).

Conditions affecting growth (principally moisture availability) affect wood anatomy and chemistry. Slow growth generally results in the development of less-dense heartwood, due to the higher proportion of large-diameter vessels produced in the spring. In contrast, rapid growth generates wood with a higher portion of small vessels (summer wood). This results from growth continuing into the summer months. The major deposition of tannins occurs some 10–15 years after vessel formation, when sapwood differentiates into heartwood. Because deposition occurs predominantly in large-diameter spring vessels, growth rate indirectly affects heartwood chemistry. The phenolics not only contribute significantly to the flavors extracted during in-barrel maturation, but also donate resistance to wood rot.

Due to the higher proportion of large-diameter vessels, slow-grown wood is slightly softer. The lower percentage of cell-wall material in the wood makes it more pliable than oak that grew rapidly. In France, the properties of slowly grown Q. sessilis, found in forests such as Nevers and Allier, are commonly preferred for wine maturation. For brandies, the denser, but less aromatic Q. robur, found in Limousin is preferred. The properties and origin of the wood preferred depend largely on the desired balance between varietal and oak attributes in the finished wine.

In addition to growth-rate induced variations, structural and chemical differences occur throughout the tree. More extractable ellagitannins occur in the heartwood at the base of the tree than near the crown, and in heartwood close to the sapwood. This may reflect increased phenolic deposition as the tree ages, as well as the hydrolysis to ellagic acid and oxidative polymerization to less soluble forms. American white oaks tend to have lower levels of extractable ellagitannins than their European counterparts. Significant variations in the concentration of oak lactones and vanillin have also been observed across the wood grain (Masson et al., 1996). Nevertheless, variation among individual trees is often more marked than average differences between species.

Wood properties reflect both the climatic conditions prevalent in the region, as well as the silvicultural practices employed to maintain forest productivity. A classic example is the denser tree spacing used in Tronçais. This is based on the view that thin annual growth rings (narrow grain), associated with slow growth, generate higher quality wood. In an extensive study of Quercus robur and Q. sessilis, Doussot et al. (2000) found that grain (ring width) was poorly correlated with either extractable ellagitannins or volatile compounds. Nonetheless, ring width apparently correlates with the wood’s tendency to shrink on drying (Vivas, 2001), and with reduced oxygen permeability (Vivas et al., 2003). Both are significant properties relative to barrel quality.

Although most chemical variations arise from differences in growth rate and tree age, dissimilarities also originate from genetic divergence. The most significant occur between Q. alba (and related species) and European species (Q. sessilis and Q. robur). American oak appears to possess about 40% of the extractable phenolics found in European oaks (Singleton et al., 1971). However, not all European oak samples possess high tannin contents (Hoey and Codrington, 1987). In addition, Q. sessilis generally contains considerably less extractable phenolics than Q. robur. Winemakers desiring higher tannin and phenol levels may choose oak, such as that from Limousin, whereas those preferring lower levels could use Q. alba, or the mild Q. sessilis of Germany. Those preferring intermediate tannin values might prefer one of the forms of Q. sessilis grown in France. There is some evidence that wine color stability (higher content of polymeric anthocyanins) develops more rapidly in American than French oak (Pérez-Prieto et al., 2003b).

Although significant differences exist in the levels of extractable tannins between American and European oaks, the intensity of oak flavor is similar, albeit different in character (Singleton, 1974). For example, American oak possesses markedly higher levels of isomers of the volatile norisoprenoids, 3,4-dihydro-3-oxoactinidol and oxoedulan derivatives, than Vosges oak (Sefton et al., 1990). Q. alba is also distinguishable from European white oaks by the presence of isomers of 3-oxo-retro-α-ionol (9-hydroxy-4,6-megastigmadiene-3-one) (Chatonnet and Dubourdieu, 1998a). Oak species also differ in oak lactone content (isomers of β-methyl-γ-octalactone), and probably in sesquiterpene, hydrocarbon, and fatty acid concentrations. For example, Q. alba has often been found to possess the highest oak lactone content (especially the more aromatic cis isomer), whereas Q. robur has the lowest (Prida and Puech, 2006). Although typical (Chatonnet and Dubourdieu, 1998a), it is not consistent. In a study by Spillman et al. (1996), Q. sessilis from Vosges had the highest content, and Q. alba the lowest. Differences between specimens of the same species, obtained from different sites, are illustrated in Fig. 8.40. With the sources of variation being so extensive, it is not surprising that differences among winemaker preferences and studies are so common.

Even barrels produced by separate firms, to similar specifications and from the same species, may differ more markedly than attribute differences generated by species origin (Gawel et al., 2002). Variations in oak lactone content have often been considered the most significant feature distinguishing wines aged in barrels derived from different species (Spillman et al., 1996; Prida et al., 2009). Aspects of this chemical differentiation were still detectable in wine 10 years after bottling (Gougeon et al., 2009).

Habituation to the flavor attributes of locally or readily available sources of oak probably explains much of the traditional association between oak provenance and use in particular regions. For example, Spanish vintners customarily prefer American oak cooperage, whereas French producers tend to favor oak derived from their own extensive and local forests (4.2 million hectares). Intriguingly, deforestation in France during the nineteenth century probably explains the contemporary French preference for oak from Russia and Germany, followed by North America, the Austrian Empire, and finally France (Maigne, 1875); French forests were subsequently reestablished.

Recent studies support the high quality of Russian oak (Chatonnet, 1998). In another study, oak from Eastern Europe appeared to be intermediate in character between French and American oak (Prida and Puech, 2006). Although matching oak flavor with the wine remains as elusive and subjective as ever, progress in oak chemistry may soon facilitate decision-making. Differences in sensory attributes can often be recognized by trained panels when identical wines are aged similarly in oak of different origin, seasoning, toasting, or production technique. Nevertheless, these influences are frequently incredibly difficult to recognize in nonidentical wines. This indicates that oak extractives are simply another component in the interplay of wine flavors – whose sensory input is often difficult to predict. In that regard, oak is equivalent to the function of a spice or condiment in cooking.

With all the various sources of variation in oak flavor (Table 8.3), the only way to achieve some degree of standardization is to use barrels incorporating a randomized selection of staves from a relatively common source (standard practice), blend wine matured in a large selection of barrels, and frequently sample to assess that the wines are developing the characteristics desired.

Table 8.3

Summary of sources of variation in oak flavor found in wine

Oak species (coarse/fine grain, tyloses, chemistry, rays)

Geographic origin (rate of growth and ratio of spring to summer wood)

Location along length of tree trunk

Method of drying/seasoning (kiln drying versus the climatic conditions prevalent in the location where external seasoning occurred)

Type of barrel production (steaming versus firing)

Level of toasting

Nature of barrel conditioning prior to use

Size of cooperage, duration, and cellar conditions during maturation

Repeated use (with or without shaving and retoasting)

Primacy of Oak

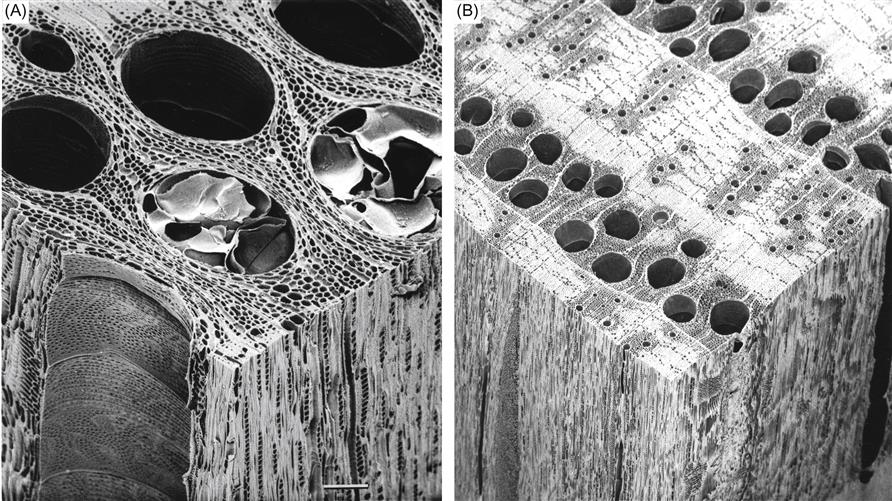

Wine cooperage requires that the wood possess very specific properties. It must be straight-grained, that is, possess vessels and fibers running parallel to the length of the trunk, with no undulating growth patterns or vessel intertwining. In addition, the wood should exhibit both strength and resilience. Structurally, the segments must be free of faults that could make the cooperage leaky. The wood also must be free of pronounced or undesirable odors. In all these aspects, Q. alba, Q. robur, and Q. sessilis excel. The trees also grow large, straight, and tall. This minimizes wood loss during logging and stave production. Furthermore, white oaks combine two relatively unique quality features – large rays and tyloses. With oak’s other attributes, these two features make oak the wood of choice in constructing tight cooperage.

All trees produce rays – collections of parenchyma cells elongated radially. These act as conduits for the flow of water and nutrients between living sections of bark and wood. In oak, the rays can be unusually large. They can be upward of 15–35 cells thick and 100 or more cells high, although they are more commonly single columns of parenchyma cells. In cross-section, large rays resemble elongated lenses (Fig. 8.41B). Because barrel staves are split (or sawed) along the radius, the broad surface of the stave runs roughly parallel to the rays. The radial plane becomes the inner and outer surfaces of the cooperage. The high proportion of ray tissue in oak (~28%) and its positioning parallel to the cooperage circumference make rays a major barrier to wine and air diffusion. Wine diffusing into ray cells is deflected 90° along the stave width. Continued lateral flow is limited by nonalignment with the rays of adjacent staves. Wine would have to navigate a very tortuous route, past five or more large rays, to diffuse out through the sides of a barrel. In practice, wine seldom penetrates more than about 20% of a typical barrel stave (~6 mm) (Singleton, 1974).

Positioning the radial axis of the wood tangential to the barrel circumference has additional benefits in the construction of tight cooperage. The large number of rays permits only minor circumferential swelling. The swelling (~4%) is sufficient, however, to help compress the staves together and seal joints. Positioning the radial plane of the wood facing outward also directs the axis of greatest wood expansion (its tangential plane) inward. In this alignment, an expansion of about 7% (Peck, 1957) does not influence barrel tightness. The negligible longitudinal expansion of the staves has no effect on barrel tightness or strength.

The high proportion of rays also gives oak much of its flexibility and resilience. Otherwise, the staves would be too tough to be easily bent to form the curved sides (bilge) of the barrel without cracking. The bilge permits full barrels, weighing several hundred kilograms, to be easily rolled.

Oak produces especially large-diameter xylem vessels in the spring. These are sufficiently large to be seen with the naked eye. The vessels allow the rapid flow of water and nutrients up the tree early in the season. However, this porousness would allow wine to readily seep out stave ends. This does not occur with white oak because the vessels become tightly plugged as the sapwood differentiates into heartwood (Fig. 8.41A). This is in strong contrast to red oak (Fig. 8.41B). The plugging results from the expansion of surrounding companion parenchyma cells into the empty vessels. These ingrowths are termed tyloses. Tylose production is so extensive that the vessels become essentially impenetrable to the movement of liquids or gases. Correspondingly, only heartwood is used in the construction of tight cooperage.

The combined effects of rays, tyloses, and the placement of the radial plane of the stave tangential to the circumference severely restricts the diffusion of air and wine through the wood. With proper construction and presoaking, oak cooperage is essentially an impervious, airtight container.

As sapwood completes its maturation into heartwood, deposition of phenolics kills any remaining living wood cells. The phenolics (primarily ellagitannins) render the heartwood highly resistant to decay. Because mature heartwood contains only nonliving cells, its lower moisture content makes the lumber less liable to crack or bend on drying. These features give heartwood the final properties required for superior quality cooperage wood.

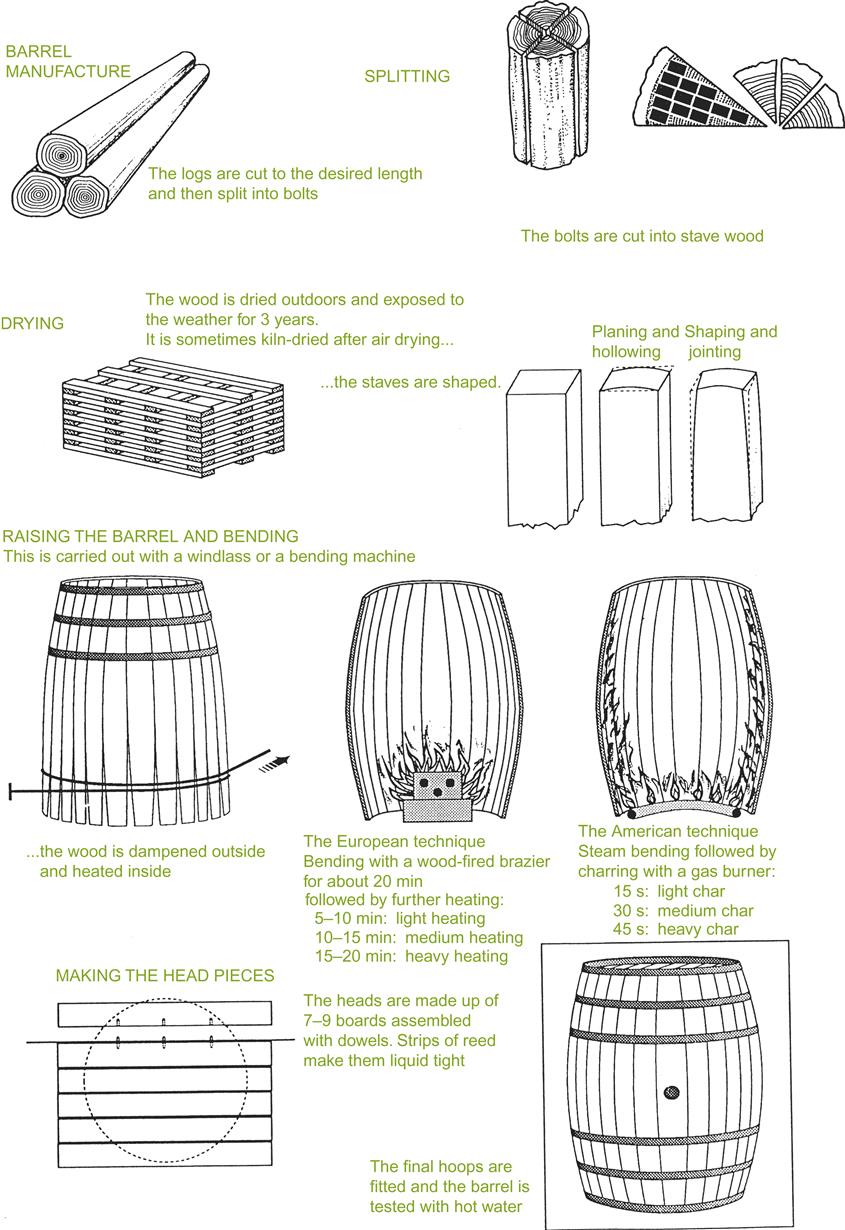

Barrel Production

Staves

For stave production (Fig. 8.42), trees with diameters between 45 and 60 cm are favored (minimum 100–150 years old). Larger trees tend to be used for the production of head staves (headings). After felling, the trees are cut into sections (bolts), equivalent to the stave length desired. They are then split (or sawed) into quarters, out of which the staves are split (or sawed). In sawing, planks of uniform thickness are produced, aligning the cuts roughly along the radius (parallel to the rays). In splitting, wedge-shaped planks are removed. Portions too narrow for stave production are discarded. Subsequently, wood is removed from the planks to give them a more uniform width. Because splitting follows the plane of vessel elongation, the sections may be somewhat twisted. Any sapwood associated with a stave section is removed. Staves may vary slightly in breadth. Staves with a light pinkish coloration (next to the sapwood) are preferred.

Despite the loss of wood, and the lower uniformity in width associated with splitting, it is still preferred. This relates to separation of the wood along natural planes of vessel elongation and ray extension. Although oak is ‘straight-grained,’ sawing unavoidably cuts across some irregular vessels, increasing surface roughness and possibly enhancing permeability. The latter appears not to have been established experimentally. This may be more of a problem with European oaks. Their large-diameter spring vessels possess fewer and thinner (more fragile) tyloses than American oak (Chatonnet and Dubourdieu, 1998a). The consequential greater porosity of European oak may also partially explain why the staves release more phenolics than similarly made American oak staves. Sawing across surface vessels is relatively insignificant with American oak because of its thick, tightly packed tyloses. This makes the short, severed vessels liquid and gas impermeable.

With splitting, one side of the staves is shaved obliquely to make the sides parallel. This also cuts across wood rays and vessels, creating potential points of leakage. In practice, this appears to be inconsequential, due to the stave’s thickness. Heading pieces are cut out similarly, but are removed from shorter lengths of wood.

Stave length, width, and thickness depend on the desired cooperage volume. By affecting the surface area/volume ratio, cooperage volume directly affects the rate of maturation. To favor early maturation, barrels constructed of thinner (~2.1 cm), Château-style staves may be preferred (presumably by favoring increased oxygen penetration). They are also refilled less often. For standard barrels, staves and headings are roughly 2.7 cm thick. Most barrels used in the maturation of wine possess a capacity of 225 liters.

Once cut, the staves and heading pieces are stacked to dry and season in the open air. Natural seasoning for about 3 years is traditional (~1 yr/cm thickness). Stacking each stave row at right angles favors good air circulation, while close spacing diminishes excessively rapid drying (limiting warping or cracking). The stacks are usually dismantled, the staves randomized, and the piles reconstructed each year. This minimizes variation based on positioning within the stacks.

It is generally considered that naturally dried oak gives a more pleasant, woody, vanilla-like character, whereas kiln drying produces a more aggressive, green, occasionally resinous aspect (Pontallier et al., 1982). Various interpretations for this subjective opinion have been offered. Masson et al. (2000) noted a reduction in oak lactone, volatile phenol, fatty acid, and norisoprenoid contents, and an enhancement in the concentration of furfural and hydroxymethylfural levels with kiln drying. This has been confirmed by Martínez et al. (2008) finding lower concentrations of volatile phenols, phenolic aldehydes, and furanic compounds, as well as both isomers of β-methyl-γ-octalactones. An additional advantage of external natural seasoning, especially for European oak, has been seen in the reduction of subsequent ellagitannin extraction.

The differences between natural seasoning and kiln drying are magnified if drying occurs at higher temperatures and involves green wood (without prior air drying). Kiln drying normally occurs at between 45 and 60°C. It can rapidly bring newly cut (green) wood down to a desirable moisture content – about 12%. The specific effects of drying method often depend on the species (Chatonnet, 1991). For example, Q. sessilis releases more tannins following kiln drying than does Q. robur. Although kiln drying decreases the production or release of oak lactones and eugenol, it can increase the availability of trans-methyl octalactone from Q. sessilis.

With Q. alba, natural seasoning favors pyrolytic breakdown during barrel toasting, especially its cellulosic constituents. The longer the seasoning, the greater the potential production of compounds, such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, furfural, and 5-methyl furfural (Hale et al., 1999). The effects of air drying are also noticeably influenced by the local climate (Francis et al., 1992; Spillman et al., 2004). Because of the variation in the moisture content of air-dried staves, and the potential for undesirable fungal development at higher moisture contents, it is now common to combine air drying with kiln drying.

Although fungal attack can reduce wood quality, it may also generate some of the benefits associated with natural seasoning. Fungal action has the potential to synthesize aromatic aldehydes, as well as lactones from wood lignins (Chen and Chang, 1985). For example, the wood-rotting fungus, Coriolus versicolor, produces polyphenol oxidases that can degrade lignins, as well as induce phenolic polymerization. Many fungi have been isolated from the outer few millimeters of staves, but it takes almost a year before penetration of the wood becomes microscopically evident (Vivas et al., 1997). The significance, if any, of the frequent isolation of common saprophytic fungi, such as Aureobasidium pullans and Trichoderma spp., has not been established. Their isolation may indicate no more than contamination from the air, not metabolic activity.