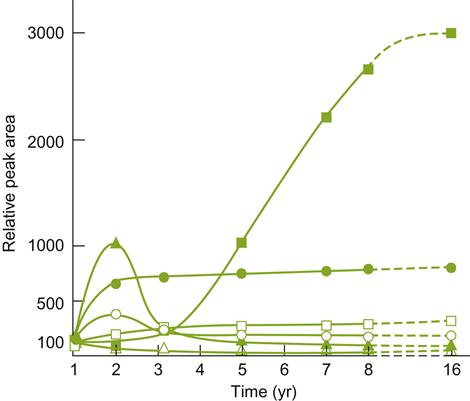

, benzaldehyde;

, benzaldehyde;  , unknown;

, unknown;  , vitispirane;

, vitispirane;  , nerolidol;

, nerolidol;  , hexyl acetate and isoamyl butyrate;

, hexyl acetate and isoamyl butyrate;  , total volatile acidity. (From Loyaux et al., 1981, reproduced by permission.)

, total volatile acidity. (From Loyaux et al., 1981, reproduced by permission.)Although the changes noted above are correlated to the second in-bottle fermentation and extended lees contact, how they arise remains unclear. Some, such as the release of glucans, amino acids, peptides, and mannoproteins are clearly associated with yeast autolysis. In contrast, the involvement of autolysis in the development of the distinctive aromatic characteristics of sparkling wines is uncertain. In addition, the potential significance of aromatic absorption by lees should not be overlooked (Gallardo-Chacón et al., 2010).

Correlations between bubble size and foam stability, and the presence of certain polysaccharides and hydrophobic proteins, have been demonstrated (Maujean et al., 1990). Colloidal protein content can double or triple within the first year.

Riddling

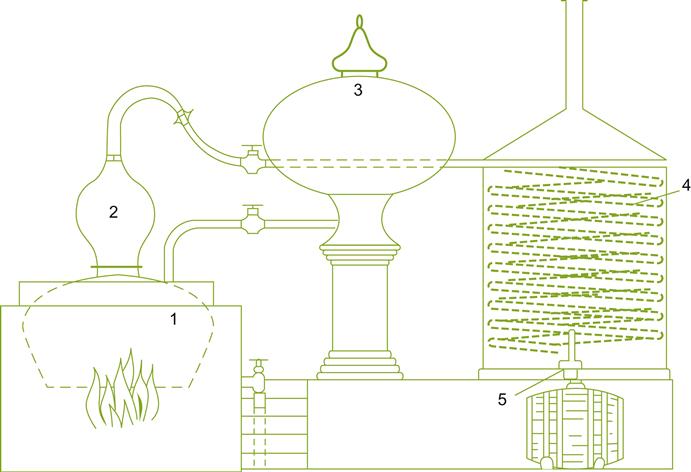

One of the more intricate procedures in sparkling-wine production involves removal of the yeast sediment (lees). The first step entails repeated loosening and suspending the cells in the wine. Progressing positioning of the bottle upside down moves the lees to the neck. The associated agitation also aids optimal flocculation (Stratford, 1989).

Historically, riddling (remuage) was done by hand. It took about 3 to 8 weeks, with the bottles finally being positioned neck downward in A-shaped racks (pupitres). Initially, they were arrayed to position the bottles 30° from vertical. Periodically, the sides of the pupitres were moved further apart, so that the bottles eventually came to be positioned about 10–15° from vertical. Rapid, short, vigorous bottle twisting (about one-eighth of a turn) dislodged the sediment. The bottle was then dropped back into the rack, a quarter turn (alternately to the right or left) of its original position. This action was repeated at roughly 2-day intervals.

Manual riddling has largely been replaced by automated mechanical riddling. It is less expensive, takes only about 7 to 10 days, and requires much less space (Plate 9.10). When fermentation and storage occur in the same container as riddling, bottle handling is greatly reduced. Various automated riddling systems are available. However, over zealous attempts to reduce the duration of riddling can leave the wine with a bentonite haze (Jeandet et al., 2000). The particles may also interfere with foam stability (Senée et al., 1998).

Disgorging, Dosage, and Corking

At the completion of riddling, the bottles are often left neck down for several weeks, in preparation for sediment removal (disgorging). For disgorging, the bottles are cooled to approximately 7 °C. Cooling increases the solubility of carbon dioxide, reducing the likelihood of gushing upon opening. Subsequently, the necks are immersed in an ice bath (a glycol- or CaCl2-ice solution, approximately−20 °C). This quickly freezes the sediment in the neck. Freezing commonly occurs in a trough, while the bottles are being transported through the freezing solution on way to the disgorging machine. Congealing the lees in ice, located within the bidule, facilitates ejection.

In rapid succession, the disgorging machine inverts the bottle, removes the cap, allows ejection of the frozen yeast plug, and then covers the mouth of the bottle with a sequence of devices. To minimize oxygen exposure, the headspace volume is usually flushed with carbon dioxide or an inert gas prior to cork insertion. These prevent further wine escape and adjust the wine to the desired volume (by either wine addition or removal). Adjustment is necessary because the amount of wine lost during disgorging can vary considerably. It is during this volume adjustment phase that any dosage liqueur is added.

The dosage typically consists of a concentrated sucrose solution (60–70%), dissolved in high-quality aged white wine. Preferably, the dosage wine is the same as the cuvée. Occasionally, brandy may be added to the dosage, as well as a small quantity of sulfur dioxide (15 to 20 mg/L). At this concentration, it helps restrict microbial spoilage and limit oxidation, without favoring the development of a reduced odor (Valade et al., 2006). The latter could arise from hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans, derived from cysteine residues in the wine (Tirelli et al., 2010). Without flushing the neck, disgorging may permit the uptake of about 1 mg O2 /L. Amounts, in about the same range, can be derived from oxygen dissolved in the dosage liqueur, or wine added to achieve the desired volume. An additional 3 mg O2 may slowly dissolve out of the lumen of cork cells. Typically, the oxygen is completely consumed within 6 months. Subsequently, oxygen uptake appears negligible, for at least several months (Bunner et al., 2010). A small quantity of malic acid may also be added to the dosage. This retards calcium tartrate crystallization and, thereby, instability problems. The dosage is prepared several weeks in advance, to ascertain that turbidity does not develop. The dosage volume depends on the sweetness desired, and, therefore, its sugar content.

A few sparkling wines receive no or minimal sweetening. Nature (<0.3% sugar) and Extra Brut (<0.6% sugar) wines are rare because the cuvée is seldom considered to have sufficient balance to be harmonious when bone dry. Brut wines tend to be adjusted with dosage up to 1.5% sugar. Extra-sec wines generally contain between 1.2 and 2% sugar; sec wines commonly possess between 2 and 4% sugar; demi-sec wines have between 3 and 5% sugar. Doux styles (now rare) contain more than 5% sugar. The range of sugar found in each category may vary beyond that indicated, depending on whether sugar remains following the second, in-bottle fermentation.

After volume adjustment and dosage are complete, the bottles are sealed with special corks (31 mm in diameter and 48 mm long). They are commonly composed of agglomerate cork, to which two disks of natural cork have been attached. They also possess a silicone coating on the surface in contact with the wine. Both the agglomerate portion and the silicone liner appear to limit contamination of the wine with TCA (Vasserot et al., 2001b). Although laminated corks were developed around the end of the 1800s (Sharf and Lyon, 1958), their use did not become standard until much later.

Once the cork is inserted, and just before addition of the wire hood, the upper 10 mm of the cork is compressed into its familiar, rounded shape. After the wire hood has been fastened, the bottle is agitated to disperse the dosage. The bottles are stored for 1–3 months, during which time the dosage marriages with the wine, and the cork sets in the neck. Before setting, cork extraction is particularly difficult. The rest period may occur either before or after the bottles are cleaned, in preparation for adding the capsule and label. Special glues are commonly used to retard label separation in water.

In a creative break with custom, a new closure for sparkling wine has been developed (Plate 9.11). It is in essence a resealable screw cap, but adheres to standard sparkling wine bottles, and retains most of the appearance of traditionally closed sparkling wines. Another new alternative involves a modified standard RO (Roll-on) closure. Regrettably, its use requires the adoption of bottles designed specifically for their application.

Yeast Enclosure

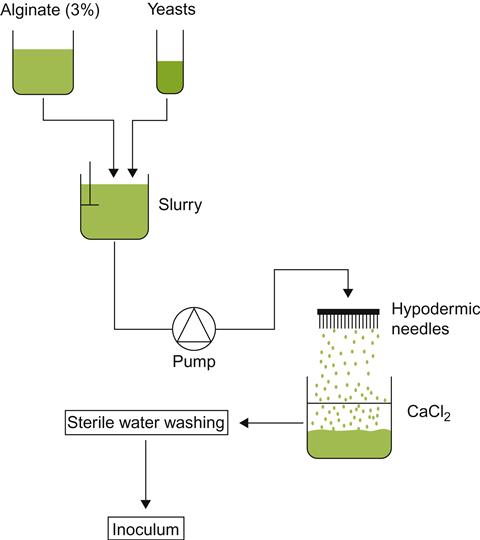

Incorporation of yeasts and other microbes into a stable gel matrix is increasingly being used in industrial fermentations. Investigation of its potential applicability to winemaking is comparatively recent and still tentative (Fumi et al., 1988; Martynenko and Gracheva, 2003). By injecting a yeast–gel mixture through fine needles into a fixing agent, small beads of encapsulated yeasts are generated (Fig. 9.28). Each bead contains several hundred cells. Because of the bead’s mass, simple inversion of the bottle results in rapid settling to the neck, thus eliminating the need for riddling.

Wines produced and aged with encapsulated yeasts show only subtle chemical differences from their traditionally produced counterparts (Hilge-Rotmann and Rehm, 1990). These differences appear not to influence the sensory properties of the wine. Nonetheless, these procedures have as yet to enter mainstream sparkling wine production.

Another innovative concept involved retaining yeasts, free, within a porous cartouche inserted into the bottle – the Millispark (Jallerat, 1990). Apparently, it was abandoned due to problems with diffusion of nutrients and aromatics into and out of the enclosure.

Transfer Method

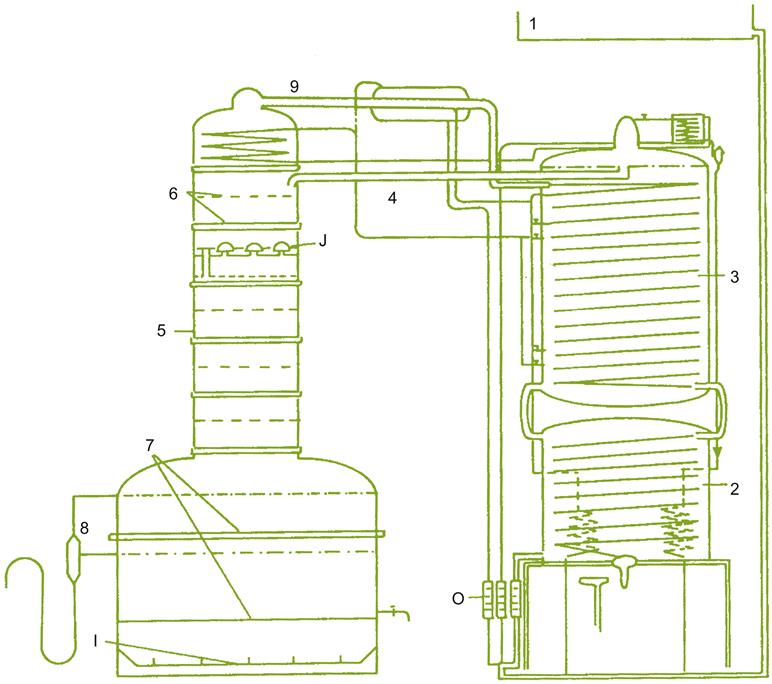

The transfer method (Fig. 9.19) was developed in the 1940s as a means of avoiding both the expense of manual riddling and the low quality of the wines then being produced by the bulk method (see below). With advancements in automated riddling, most of the advantages of the transfer method disappeared. Furthermore, advances in the bulk method have eliminated the sources of poor quality that initially plagued the process. Because the transfer system is capital-intensive, but does not have the prestige and pricing advantage of the standard method, its continued existence is in doubt. The one remaining advantage of the transfer technique consists of its avoiding bottle-to-bottle variation that can occur with the traditional method.

Preparation of the wine up to riddling is identical to that described for the standard method. Because the wines are not riddled, fining agents need not be added to aid yeast sedimentation. Typically, the bottles are stored neck down in cartons for aging. After maturation, the wine is chilled to below 0 °C before discharge. The bottles are opened by a transfer machine and the wine poured into special, pressurized receiving tanks. The wine is usually sweetened (dosage) and sulfited at this stage. Subsequently, the wine is clarified by filtration and decolored if necessary. The wine is typically sterile-filtered, just prior to bottling.

Bulk Method

Current versions are modifications of the technique initially developed by Charmat about 1907 (Charmat, 1925). The procedure (Fig. 9.19) works well with sweet sparkling wines, designed to accentuate varietal character. The best known examples are those produced from Muscat grape varieties, notably the sparkling (spumante) wines from Asti. The marked varietal character of Muscat grapes would mask the subtle bouquet generated, at considerable cost, by the standard method.

Occasionally, the wine may be aged on lees for up to 9 months, if a traditional lees-matured attribute is desired. However, because expensive pressurized tanks are tied up for months, many of the economic advantages of the system are voided.

One of the features generally thought to characterize bulk-processed sparkling wine is poorer effervescence. However, an accurate means of assessing this view has only recently become available (Maujean et al., 1988; Liger-Belair et al., 1999). Objective proof of this assertion awaits verification.

Base wine production may go to dryness or be terminated prematurely. Occasionally, fermentation is arrested at about 6% alcohol to retain sugars for the second fermentation. Termination is either by exposure to cold, followed by yeast removal, or directly by yeast removal. Yeast removal is achieved by a combination of centrifugation and filtration, or by a series of filtrations. Once the cuvée has been formulated, the wines are combined with yeast additives (ammonia and vitamins) and sugar, if necessary. The second fermentation takes place in reinforced stainless steel tanks, similar to those employed in the transfer process. If a dosage is not employed, and residual sweetness is desired, the second fermentation must be arrested early. This is most easily achieved by cooling the fermentor to about 8 °C.

If an extended contact period with yeasts is desired, for bouquet development, the lees are intermittently stirred. Left undisturbed, a thick layer of yeast cells would form, favoring the generation of reduced-sulfur taints. Mixing also helps release amino acids thought to be involved in evolution of a toasty bouquet. However, stirring also releases fat particles not easily removed by filtration. These may interfere with effervescence production (Schanderl, 1965).

At the end of fermentation, or lees contact, the wine is cold-stabilized to precipitate tartrates. Yeast removal involves centrifugation or filtration. It is imperative that these operations be conducted under isobarometric pressure conditions. Otherwise, carbon dioxide may be lost, or gained, if the pressurizing gas is carbon dioxide. Sugar and sulfur dioxide contents are adjusted just before sterile filtration and bottling.

Occasionally, still wine may be added to the sparkling wine before final filtration and bottling. This technique may be used to produce wines of reduced carbon dioxide pressure, such as Cold Duck.

Other Methods

A small amount of sparkling wine is produced by the rural or natural method. The primary fermentation is terminated early by repeated filtration to remove the yeasts. This also removes essential nutrients from the juice, notably nitrogen. Formerly, fermentation was stopped by repeatedly skimming off the cap of the fermenting juice. After fermentation has ceased, the wine is bottled, and a second in-bottle fermentation slowly converts the remaining sugars to carbon dioxide. Yeast removal usually entails manual riddling and disgorging.

Other wines have derived their sparkle from malolactic fermentation. The primary example is vinho verde from northern Portugal. The grapes are commonly harvested low in sugar, but high in acidity. They consequently produce wines low in alcohol, high in acidity. The addition of little sulfur dioxide and late racking favored the development of malolactic fermentation. Cool cellar conditions typically resulted in its occurrence in late winter or early spring. Because the wines were kept tightly bunged after fermentation, the small volume of carbon dioxide produced was trapped. The pétillant wine that resulted was consumed directly from the barrel. When maturation shifted to large tanks, much of the carbon dioxide liberated by malolactic fermentation escaped. This was especially pronounced when the wine was filtered to produce a stable, crystal-clear wine for bottling. Correspondingly, the wine is often carbonated to reintroduce its characteristic pétillance. Occasionally, vinho verdes are produced without carbonation or malolactic fermentation, when they are low in malic acid content.

In Italy, some red wines become pétillant following in-bottle malolactic fermentation. Often the same wine is produced in both still and spumante (sparkling) versions.

In the former Soviet Union, sparkling wines were commonly produced in a continuous fermentation process. Though extensively used in Russia, it has been used only sparingly outside the former communist state, for example, Portugal. Multistage, bioreactor, continuous fermentors have also been investigated in Japan (Ogbonna et al., 1989).

Carbonation

The injection of carbon dioxide under pressure is undoubtedly the least expensive method of producing a sparkling wine. It is also the least prestigious. Prestige must, by definition, be exclusive. Consequently, carbonation is used only for the least expensive effervescent wines.

Because of the comparative lack of surfactants, bubbles tend to be larger than in sparkling wines. Essentially, no mousse (semi-stable form) develops. Nonetheless, the effervescence can accentuate any faults the wine may possess. Thus, the base wine needs to be of good quality.

Although carbonated wines are generally discounted as unworthy of serious attention, carbonation has the advantage of leaving the aromatic and taste characteristics of the wine unmodified. No secondary microbial activity affects the sensory attributes of the wine. It is really a matter of preference and choice.

Production of Rosé and Red Sparkling Wines

Although red grapes may be used in the production of sparkling wines, they are normally processed to make a white wine. Only occasionally are red grapes, fermented on their skins, used to produce a rosé or light-red sparkling wine. The tannins extracted along with the pigments complicate the second fermentation and accentuate gushing. Consequently, the bulk method is preferred in their production. The base wines are almost universally encouraged to undergo malolactic fermentation prior to the second fermentation. This gives the wine a smoother mouth-feel.

Rosé sparkling wines may be produced from rosé base wines. However, rosé champagnes are typically produced by blending small amounts of red wine into a white cuvée. Anthocyanins donate most of the pinkish countenance, although some may also originate from the presence of pyranoanthocyanins (Pozo-Bayón et al., 2004).

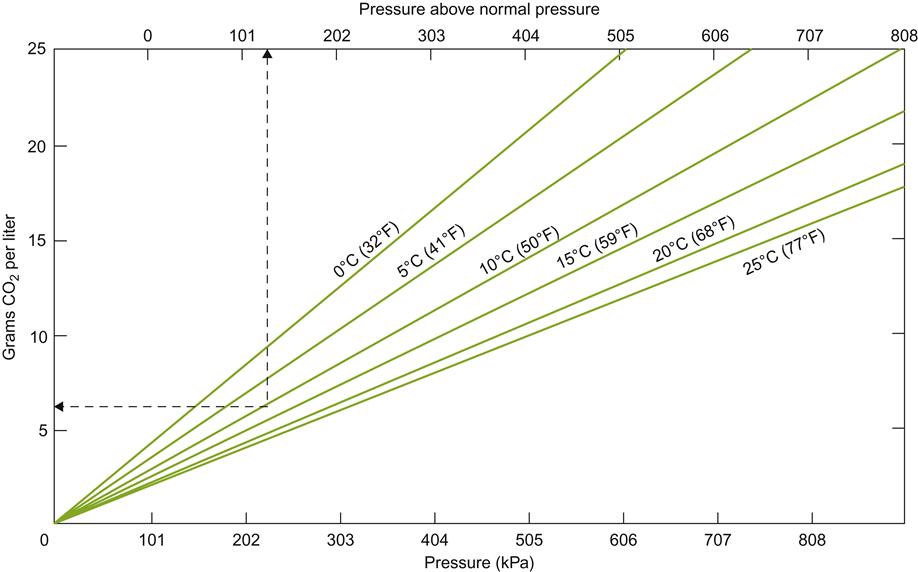

Most rosé and red sparkling wines are finished sweet, and with low carbon dioxide pressures. They are typically either pétillant (≥7 g CO2/L) or crackling (≥9 g CO2/L). The specific carbon dioxide levels applying to each of these terms can vary considerably from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In contrast, most white sparkling wines contain at least 12 g CO2/L.

Effervescence and Foam Characteristics

The appeal of sparkling wine, to consumer and critic alike, is often intimately intertwined with their effervescence and foam attributes. Correspondingly, the origin and factors affecting their development have come under considerable scrutiny (Senée et al., 1999; Liger-Belair et al., 2008b, 2010; Coelho et al., 2011). For effervescence, the appearance, size, and duration of bubble formation are central features, whereas the degree (height and extent), duration, and stability of the foam (mousse) are supplemental properties. These aspects are assessed subjectively in separate scoring systems devised by Obiols et al. (1998) and Gallart et al. (2004). Objectively, effervescence is assessed with highspeed video and strobe lighting (Liger-Belair, 2005), while foam parameters are assessed using a Mosalux (Maujean et al., 1990).

Carbon dioxide may exist in five states in water – microbubbles, dissolved gas, carbonic acid, carbonate ions, and bicarbonate ions. Within the normal pH range of wine, carbon dioxide exists predominantly in the form of dissolved gas, with no carbonate species (Liger-Belair, 2005).

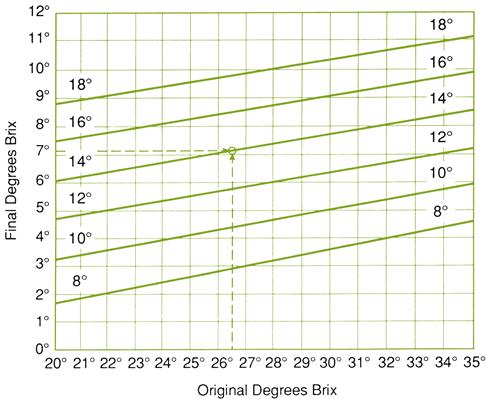

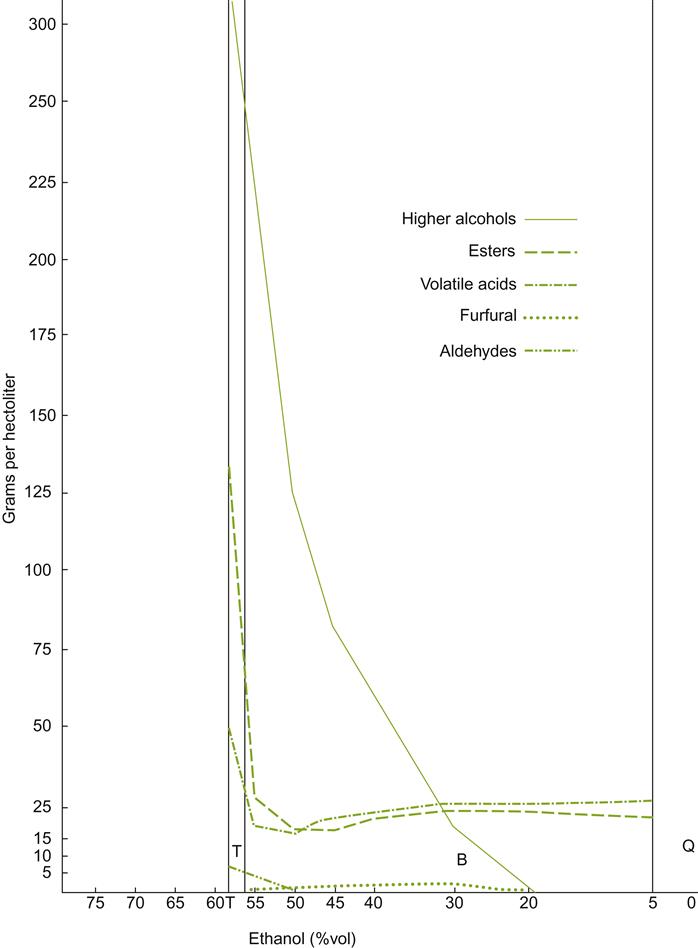

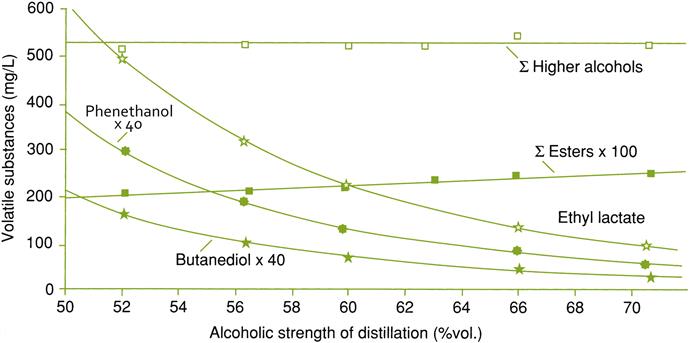

Many factors affect the solubility of carbon dioxide and, therefore, the pressure it can exert (Lonvaud-Funel and Matsumoto, 1979). The most significant factor is temperature (Fig. 9.29), with sugar and ethanol contents being secondary. Increasing these factors decreases gas solubility and augments the pressure exerted. Once the bottle is opened, ambient atmospheric pressure puts the wine into a supersaturated state. If the wine is shaken, the gas can exert sufficient force to eject a cork at velocities of up to 50–60 km/h (Liger-Belair, 2004).

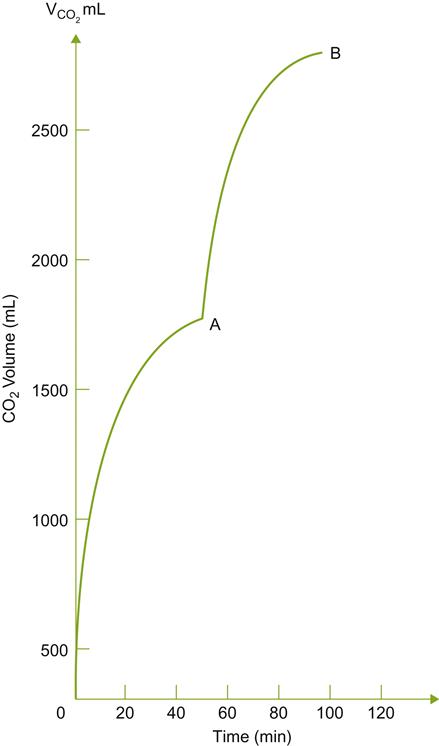

Upon opening, the headspace pressure over the wine drops from about 600 to 100 kPa (ambient atmospheric pressure). The partial pressure of carbon dioxide in air is ~0.03 kPa. This decreases carbon dioxide solubility in the wine from approximately 12 to 2 g/L, resulting in the eventual liberation of almost 5 liters of carbon dioxide gas (from a 750-mL bottle) (Jordan and Napper, 1987). Liger-Belair (2005) estimates that in a champagne flute (100 mL), full degassing would involve the release of about 10 million, 500-μm bubbles. The gas does not escape immediately, because there is insufficient free energy for bubble formation. Most of the carbon dioxide enters a metastable state, from which it is slowly liberated, if not agitated.

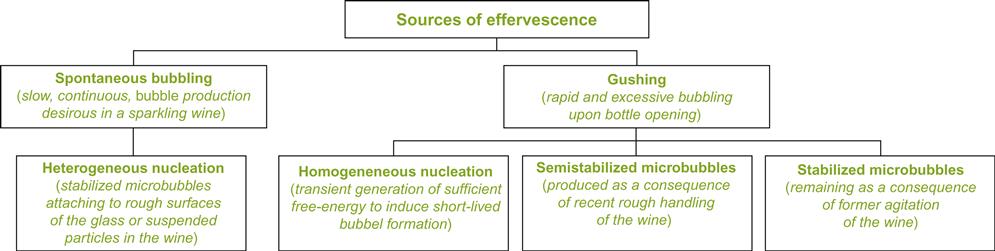

Carbon dioxide escapes from the wine either via diffusion or bubble formation (Fig. 9.30). The slowest and least significant to the sensory characteristics of sparkling wine is diffusion. Bubble nucleation may arise spontaneously, or through the action of various physical forces. Spontaneous effervescence from nucleation sites is the source for the continuous stream of bubbles so appreciated in sparkling wines. Provoked effervescence is undesirable (except during sport celebrations or ship launchings) as it enhances gushing and wine loss.

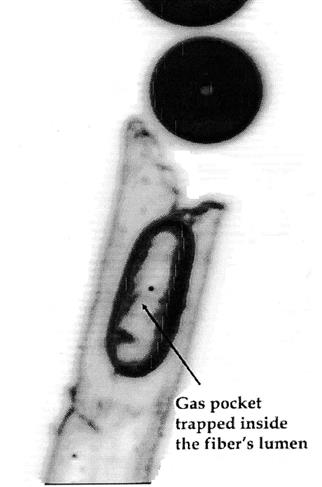

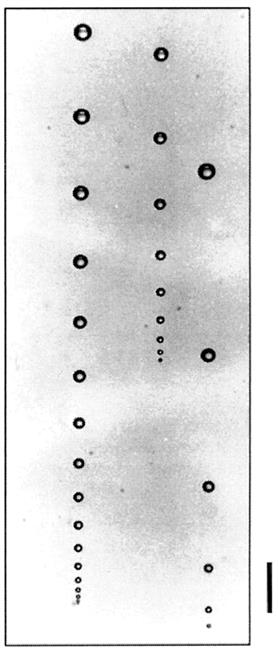

Spontaneous effervescence results from heterogeneous nucleation (Jordan and Napper, 1987). This occurs due to the formation of nucleation sites, associated with imperfections on the glass surface or extraneous suspended material. Most sites appear associated with lint fibers, adhering to the sides of the glass or floating in the wine. The latter are termed ‘fliers,’ due to their erratic or circular movements within the wine (Plate 9.12). They probably originate from glass drying or settle out of the air. They frequently possess cavities, of appropriate dimensions, to form microscopic air pockets. When wine is poured into the glass, they act as nucleation sites into which carbon dioxide can diffuse (Fig. 9.31). Nucleation sites may also develop in crevasses on tartrate salt crystals. The minimum diameter required for a nucleation site has been calculated to be about 0.25 μm (Liger-Belair et al., 2008b). Carbon dioxide, under the aegis of its supersaturated status, begins to diffuse into any entrapped air pocket. The associated formation and release of bubbles accounts for the slow liberation of almost 60% of the CO2 over a period of approximately 1 h (Fig. 9.32). As the degree of supersaturation decreases, so does the rate of bubble formation, and the size of the bubbles at the surface. The presence of even traces of detergent can inhibit this process. They coat nucleation sites, preventing carbon dioxide ingress and, correspondingly, bubble enlargement.

When the accumulating gas reaches the mouth of the nucleation site, its diameter begins to swell, developing into a nascent bubble. On reaching a critical size – from 14 to 31 μm (Liger-Belair et al., 2002), buoyancy provokes detachment (Fig. 9.31). Unknown factors can result in various bubble release scenarios, where bubbles may form in groups, or transient disruption in bubble formation occurs (Liger-Belair et al., 2006). During the ascent, carbon dioxide continues to diffuse into the bubble, increasing its diameter to upwards of 600μm. This apparently results in a dilution of surfactants coating the bubble (Liger-Belair and Jeandet, 2003). Ascent starts slowly, at about 0.2 cm/s. As the bubbles enlarge, their rate of ascent increases, reaching more than 6 cm/s as they approach the surface. Consequently, the distance between bubbles increases as they rise (Fig. 9.33). New bubbles tend to form at a rate of about 15/s, but this can vary from 1 to 30/s.

One of the sensory consequences of effervescence, other than its pleasurable appearance, is its effect on fragrance detection. The bubble chains generate convection currents and eddies (Plate 9.13). This refreshes the supply of aromatics available at the surface for volatilization. In addition, bubbles bursting at the surface propel wine microdroplets into the headspace above the wine (Plate 9.14), facilitating the escape of aromatics into the air. The effect is a selective release of volatile compounds (Liger-Belair et al., 2009). This includes decanoic acid, a compound possessing a toast-like fragrance. Although fascinating, the significance of these factors to the sensory perception of sparkling wines is questionable. Under normal tasting conditions, the wine is repeatedly swirled by the taster, generating more volatile liberation than effervescence.

In contrast to the slow, effervescent, liberation of CO2 in wine flutes, gushing can arise from a number of distinct nucleation processes (Jordan and Napper, 1987). The mechanical shock of opening or pouring provides sufficient free energy to weaken the bonds between water and carbon dioxide. Disruption of these van der Waals forces permits carbon dioxide to form nascent bubbles throughout the wine, in a process termed homogeneous nucleation. If the bubbles reach a critical size, they incorporate more CO2 than they lose. They continue to grow and begin their rapid ascent to the surface. Because the energy source for homogeneous nucleation is transient, so is the effervescence it provokes.

Another potential source of gushing comes from stabilized microbubbles. These develop from bubbles generated by agitation during handling. Most of the bubbles so formed float to the surface and break. The carbon dioxide released dissolves back into the wine, assuming the cork is still in place. However, other bubbles lose carbon dioxide to the wine, partially dissolving before reaching the surface. In the process, surfactants coating their face, produce a gas-impermeable membrane that stabilizes the bubble. After the bottle is opened, these bubbles rise to the surface. Gushing from this source takes a few seconds to develop. Semistabilized microbubbles, formed shortly after rough handling, may aggravate gushing. They can act as additional sites for bubble growth.

As noted, a membrane surrounds the bubbles as they rise. This allows them to mound on the surface, initially at the center, but also collect around the rim of the glass (Plate 9.15). This accumulation (foam) is termed the mousse. The bubbles soon burst, depending on the combined effects of the wine’s alcohol content, various surface-active ingredients, liquid drainage from between the bubbles, and the concentration of rigidifying agents, such as proteins and glycoproteins. The wine’s alcohol content (~12%) seems optimal for both foam formation and stability. When bubbles rupture, they implode on themselves. The resulting shockwave propels miniature columns of wine up from what was the submerged base of the bubble. As these columns rise, they break into a series of microscopic droplets. They can be ejected a few centimeters at several meters per second (Liger-Belair et al., 2001). Because several hundred bubbles may burst per second, the surface of the wine is spiked with these thin, cone-shaped spires (Plate 9.14). Their millisecond duration and minuscule size make them nigh invisible to the naked eye. They do, however, induce a perceptible touch sensation on the tongue and palate by stimulating nocioreceptor trigeminal nerve endings.

Because aromatic compounds (such as various alcohols, aldehydes and organic acids) may adsorb onto the bubble surface, or into the enclosed gas, they too are ejected into the headspace as the bubble ruptures. These aromatic droplets (or their remnants) can flow with air into the nose (Liger-Belair et al., 2001). This may initially enhance detection of the subtle fragrance that tends to characterize most sparkling wines. However, as time passes, the accumulation of protein and glycoprotein surfactants on the wine’s surface modifies, and eventually limits the ejection of aromatic laden droplets (Liger-Belair, 2001).

The formation of durable, continuous chains of small bubbles is an important quality attribute. The factors that regulate this property are still incompletely understood. Cool fermentation and maturation temperatures, and extended contact with the lees, are thought to favor the property. The sustained formation of fine bubble chains appears to depend on the joint effects of high-molecular-weight, and hydrophobic, low-molecular-weight mannoproteins with monoacylglycerol and glycerylethylene glycol fatty acid derivatives (Núñez et al., 2006; Coelho et al., 2011).

The formation and persistence of a cordon de mousse (Plate 9.15) is also considered an important property. It develops around the rim of the glass. In contrast to beer, the foam rapidly collapses and must be continuously replenished. Its formation and durability are largely dependent on the nature of the surfactants and the type and number of metallic ions in the wine. The surfactants, notably soluble proteins, polyphenols, and polysaccharides, decrease surface tension. Several fatty acid esters have also been found to favorably affect mousse development and stability, whereas free fatty acids negatively affect both attributes (Gallart et al., 2002). Bubble surfactants appear to collect at the wine–air interface (Péron et al., 2003), forming an amphiphilic layer composed of about 35% protein and 65% polysaccharides (Aguié-Béghin et al., 2009). Their coating of the bubbles is thought to donate a degree of stability to the mousse. The cultivar or cultivars used in preparing the base wine also affect foam attributes. For example, of several varieties assessed, Chardonnay wines had the best propensity to develop foam, but were the worst in terms of its stability (Andrés-Lacueva et al., 1997). The potential for mousse formation initially increases after the second fermentation, but may decline thereafter (Andrés-Lacueva et al., 1997). Subsequently, mousse stability may again increase.

Gravity progressively removes fluid from between the bubbles, forcing them to assume polyhedral shapes. As a result, uniformity of pressure on the sides of the bubble is lost. This forces further liquid into the angled corners of the bubbles, inducing further compaction. Thinning of the interstitial fluid layer induces fusion. Carbon dioxide in small bubbles increasingly comes under more pressure than in larger bubbles, promoting CO2 diffusion from smaller to larger bubbles. As the remaining bubbles enlarge, they become increasingly susceptible to rupture.

The presence of proteinaceous or polysaccharide surfactants tends to restrict bubble compression. Interaction between surfactants may give a degree of rigidity and elasticity to the mousse. Elasticity can absorb the energy of mechanical shocks, limiting fusion, and bubble rupture. Although formation of a mousse is desirable, it is also traditional that it be relatively evanescent. The relative absence of stabilizing surfactants limits its duration.

Aging

In contrast to the extensive research on the consequence of lees contact during in-bottle maturation, changes post-disgorgment have been little studied. This is not too surprising. Sparkling wines are rarely aged by the consumer after purchase. Nonetheless, there is a long history of a subset of connoisseurs preferring aged champagnes, either late-disgorged or post-disgorgment.

Late-disgorging (aging on the lees longer than the traditional 3 years), appears to retain the wine’s freshness longer, at least initially. However, prolonged lees contact (up to 60 months) increases the rate of oxidation. Flavor deterioration also occurs faster than that of the same wine disgorged traditionally (Stevenson, 2012).

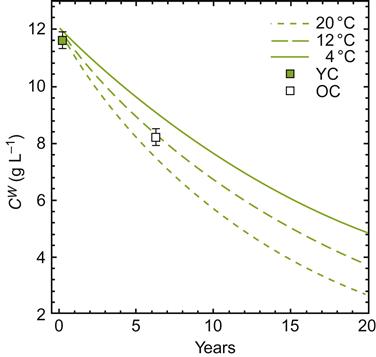

During aging, sparkling wines also slowly lose their effervescence. Only recently has this phenomenon been investigated. If the theoretical projections illustrated in Fig. 9.34 are substantiated, there should be about a 5% loss in carbon dioxide per year at 20 °C. The rate should be considerably slower at 4 °C, but, theoretically, could still result in a 60% reduction in carbon dioxide content over a 20-year period. Because champagnes may remain noticeably effervescent for about 20 years, and can still possess some fizz after 50 years, unknown factors, other than bottle volume, appear to be acting, slowing the projected loss in CO2.

) and old (

) and old ( ) sample. (From Liger-Belair and Villaume, 2011. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society, reproduced by permission.)

) sample. (From Liger-Belair and Villaume, 2011. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society, reproduced by permission.)Not only does carbon dioxide dissipate during and after disgorging, but also during the wine’s maturation on the lees. Even under a crown cap, the wine may lose 60 kPa CO2/year, depending on the seal provided (Valade et al., 2011). Oxygen uptake during this period can also sensorially affect the wine (Valade et al., 2011).

As typical for white wines, aged champagne shows a loss of floral and fruit attributes (Escudero et al., 2000). There is also the development of distinctive attributes, described as resembling roasted coffee beans, toast, and brioche (Tominaga et al., 2003). This profile has been partially associated with the presence of several thiols, for example, 2-furanmethanethiol. It is considered to donate a roasted coffee aroma to barrel-matured wines (Tominaga et al., 2000). Other thiols that accumulate to above threshold values include benzenemethanethiol and ethyl 3-mercaptopropionate. Furfural also accumulates with aging, but unlike the thiols, its increase was not associated with disgorging, as was the increase in the thiols. Additional compounds, associated with a toasty flavor, include m-cresol and decanoic acid (Escudero and Etiévant, 1999). Dihydroxyacetone has also been reported to possess a crust-like aroma.

Fortified Wines

Fortified wines are classified together because of their elevated alcohol content. This is usually derived from the addition of brandy or highly rectified spirits, at some stage in production. The marked flavor of fortified wines gives the grouping an additional unifying property. Because of this property, they are seldom consumed with meals, normally being served as aperitifs or dessert wines. Unfortunately, governments often combine them for the purposes of higher taxation.

Most fortified wines have evolved in the last two to three hundred years, primarily in southern Europe. Examples are sherry (southern Spain), port (Portugal), marsala (Sicily), madeira (Madeira) and vermouth (northern Italy). The production of some of these is discussed below.

Sherry and Sherry-Like Wines

Sherry evolved into its near-present-day form in southern Spain, possibly as late as the early 1800s. The details of its development from a young table wine, transported to England in the 1600s, are unclear (Gonzalez Gordon, 1972). The original sack imported to England, and made famous to later generations by Shakespeare, was not the sherry we know today. Sack was a table wine, coming in either red or white versions. The solera system, so associated with modern sherry, is thought to have originated in the early nineteenth century (Jeffs, 1982), and was established as standard practice by the 1850s. In its current form, sherry exists only in white to tawny versions.

In Spain, the designation sherry is used as a geographic appellation. It is restricted to wines produced in and around Jerez de la Frontera in Andalucia. Similar wines produced elsewhere in Spain, or the rest of Europe, are not permitted to use the sherry appellation. Nevertheless, similar wines may use the stylistic terms fino, amontillado, and oloroso.

Outside Europe, the designation ‘sherry’ is used generically for wines that, to varying degrees, may resemble Spanish sherries. The provenance of these products is typically appended to the term sherry. Such sherries are seldom produced by techniques similar to those employed in Jerez.

Three distinctly different techniques are used worldwide for the production of wines designated ‘sherry.’ Each is described separately. These are the traditional solera procedure (used almost exclusively in Spain), the submerged fino technique, and the baked method.

Solera System

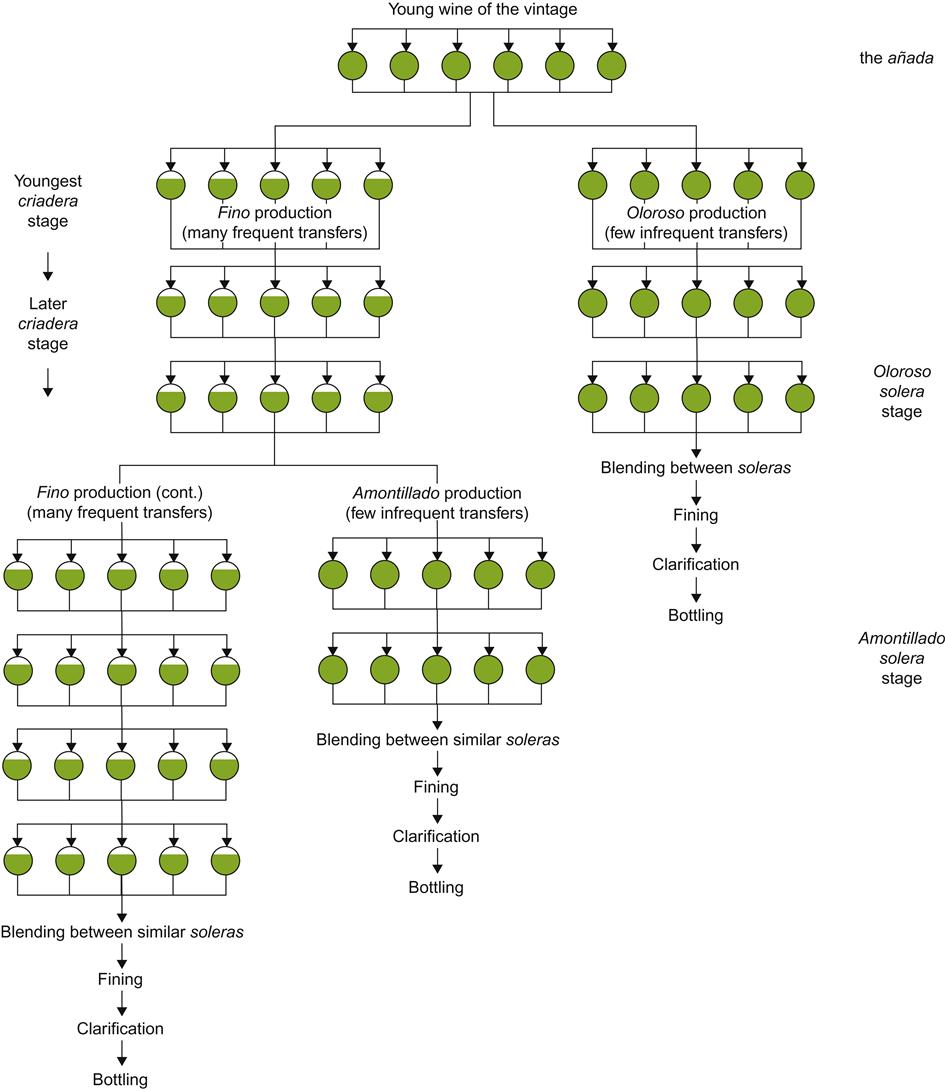

The solera system that developed in southern Spain is a form of fractional blending (Fig. 9.35). In summary, it consists of several distinct collections of casks (termed butts), each termed a criadera. When a portion of wine is removed from the criadera containing the oldest blend, termed the solera, it is replaced with an equivalent amount of wine from the next oldest criadera. This sequence continues until wine is removed from the youngest criadera. It is in turn replaced with young wine. The wine removed from the solera is prepared for bottling. The technique is ideally suited for the production of wine that is both brand-distinctive and consistent from year-to-year.

The frequency and proportion of wine transferred is adjusted to the style desired. The transfer rate and number of criaderas are particularly important. They direct the wine’s development. For example, fino sherries undergo frequent transfers and possess many criadera stages. In contrast, oloroso sherries develop best with few criaderas and involve infrequent transfers.

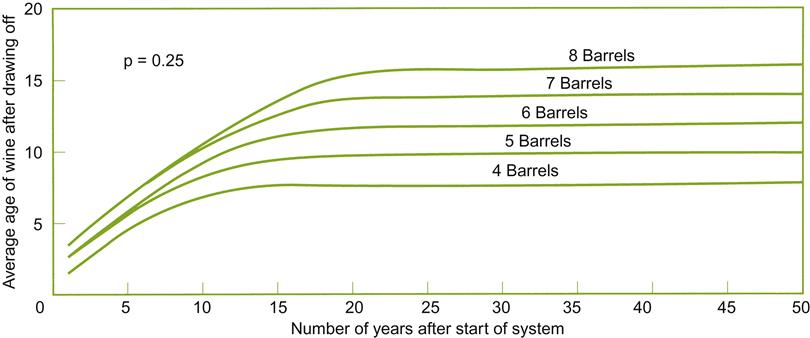

These factors also influence the average age of the sherry produced. When a solera system is initiated (a series of criaderas), the average age of the wine rises rapidly (Fig. 9.36). Subsequently, the mean age increases progressively more slowly, finally reaching what approximates a constant age. The plateau is reached more quickly when the frequency and proportion of the wine transferred is increased. Correspondingly, the number of criaderas in a solera system influences the rate and maximal age achieved. The greater the number of criaderas, the older the stable age finally achieved. Formulas for calculating the effects of these factors are discussed in Baker et al. (1952).

Spanish sherry is subdivided into three main categories – fino, amontillado, and oloroso (Fig. 9.35). They may also be classified based on where the wines are matured (e.g., Sanlúcar de Barrameda vs. Jerez de la Frontera), by their sensory characteristics (e.g., palo cortado versus raya olorosos), or on how they are sweetened (e.g., cream-type sherries).

Base Wine Production

In the past, grapes were laid out in the sun for several weeks before being stemmed and crushed. This was done to augment the sugar level of the grapes by dehydration. While still done with Pedro Ximénez and Muscat, primarily for producing sweetening wines, it is no longer applied to the principal variety, Palomino (Palomino Fino). Harvesting is done when the grapes have reached the desired maturity (≥23°Brix). Acidity level is less critical as it can be augmented with tartaric acid if insufficient. Models of maturity have been presented by Palacios et al. (1997).

Whereas the development of a sherry into a fino or oloroso once seemed arbitrary, almost mysterious, it is now largely predictable, as well as directed. Experience has shown that juice derived from grapes grown in cooler vineyards, or in cooler years, is more predisposed to becoming a fino. Vineyards containing a high proportion of chalk in the soil also tend to favor fino development. Gentle grape pressing, and the inclusion of little press-run juice, further shift evolution toward a fino. Conversely, juice derived from grapes ripened under hot conditions, grown on soils containing less chalk, pressed in hydraulic vertical presses, and incorporating press-run fractions generally promote transformation into an oloroso. Slightly higher initial phenolic contents are desired in wines designed for oloroso production (encouraging oxidation). These tendencies can also be directed by the level of fortification. Contents of 15.5 and 18% alcohol favor fino or oloroso development, respectively. The level of cask (butt) filling and maturation temperature also direct the wine’s evolution.

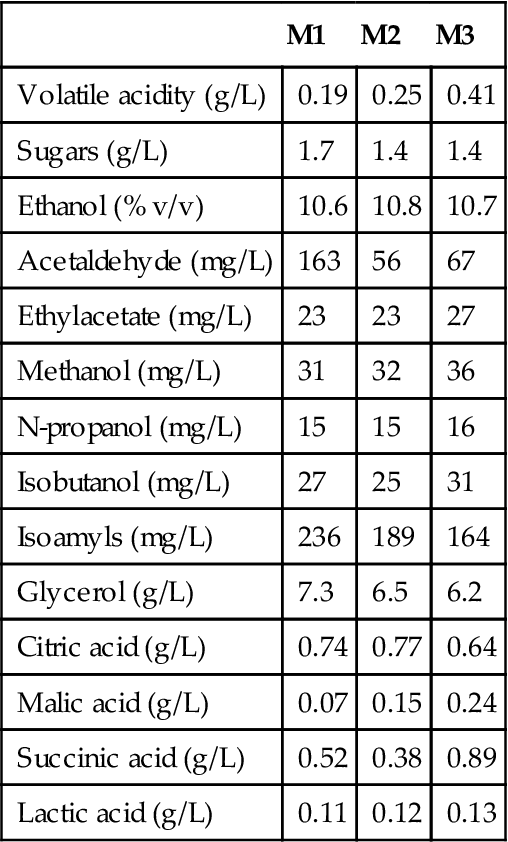

Production of the base wine generally follows standard procedures, except that fermentation occurs between 20 and 27 °C – higher than generally preferred elsewhere for white table wines. Pressing almost immediately follows crushing, thereby limiting tannin extraction. Spontaneous settling for several hours brings the suspended solids content down to 0.5–1%. The effect of suspended solids on the chemical composition of the wine is illustrated in Table 9.6. Increasing tannin content gives a roughness, inconsistent with accepted sherry norms. Values of≤200 mg/L total phenolic content are desired. Because the juice often has an undesirably high pH, tartaric acid is commonly added to correct this deficiency. A value lower than pH 3.45 is desired. The older procedure (called plastering) involved adding yeso, a crude form of gypsum (calcium sulfate). Plastering both lowered the pH and provided a source of sulfate. After conversion to sulfite, it had the additional advantage of inhibiting the growth of spoilage bacteria, notably Lactobacillus trichodes. Adding sulfur dioxide directly has the same effect, but avoids the addition of calcium, and other potential mineral contaminants in yeso.

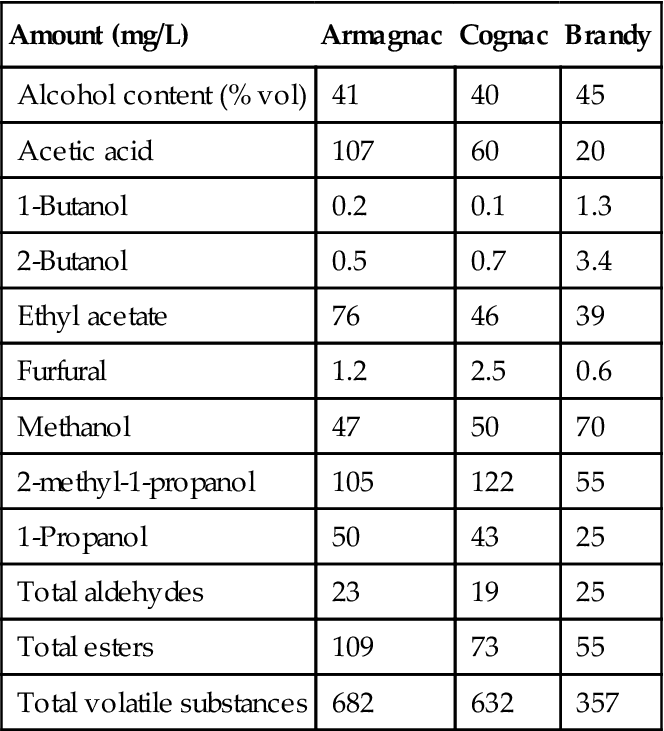

Table 9.6

Concentration of several compounds after the fermentation of a must with a different concentration of solidsa,b

| M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| Volatile acidity (g/L) | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.41 |

| Sugars (g/L) | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Ethanol (% v/v) | 10.6 | 10.8 | 10.7 |

| Acetaldehyde (mg/L) | 163 | 56 | 67 |

| Ethylacetate (mg/L) | 23 | 23 | 27 |

| Methanol (mg/L) | 31 | 32 | 36 |

| N-propanol (mg/L) | 15 | 15 | 16 |

| Isobutanol (mg/L) | 27 | 25 | 31 |

| Isoamyls (mg/L) | 236 | 189 | 164 |

| Glycerol (g/L) | 7.3 | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| Citric acid (g/L) | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.64 |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.24 |

| Succinic acid (g/L) | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.89 |

| Lactic acid (g/L) | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

aM1, not decanted (5 g/liter solids); M2, decanted (1.1 g/liter solids); M3, decanted and filtered (0 g/liter solids).

bAnalyses correspond to the sixth day after inoculation. The experiment was done per triplicate with a coefficient of variation of<10%.

Source: From Martínez et al., 1998, reproduced by permission.

Inoculation with specific yeast strains still seems uncommon, with fermentation developing spontaneously from the indigenous grape and winery (bodega) flora. If yeast inoculation is employed, it is usually added to one-third of the must. Once fermentation has become turbulent (usually 4–5 days), an equivalent volume of must is added. When this volume is clearly fermenting, the final must portion is added. Esteve-Zarzoso et al. (2001) report that despite this acclimation, the inoculated strain is occasionally replaced by wild strains. Unlike in the past, most fermentations are now conducted in stainless steel tanks, rather than in oak barrels (butts).

To avoid interference with the sherry flavor, the base wine should have little varietal aroma. In Spain, the neutral-flavored Palomino is used for dry sherry production, whereas Pedro Ximénez or Muscat tend to be preferred for making sweet, darker sherries.

Stylistic Forms of Jerez Sherry

Finos

Fino sherries are the lightest, driest, and most subtly flavored sherries. They are also characterized by possession of a flor bouquet. This develops from the action of a yeast film (velum) that grows on the wine’s surface during solera maturation (Plate 9.16). The film-forming yeasts (flor) are typically related to those that induced the original fermentation. If flor development does not occur rapidly, an inoculum may be transferred from casks containing an active culture.

After the first racking, the base wine is fortified to bring the alcohol content up to 15–15.5%, in a process termed encabezado. This involves preparing a 50:50 blend of rectified (aromatically neutral) wine spirits (∼95% ethanol) and aged sherry, called miteado. Storage for approximately 3 days permits settling of any cloud that forms, and limits haze production in the young wine. At 15%, the alcohol favors flor development, as well as restricts the growth of acetic acid bacteria. A velum (pellicle, biofilm) forms because the elevated alcohol content promotes the production of a hydrophobic cell wall (Alexandre et al., 1999). Unlike other microbial biofilms, no protein or polysaccharide extracellular matrix forms between the cells. In contrast, direct interaction between the hydrophobic Flo11 glycoprotein, with mannobiose terminal units of oligosaccharide ligands on adjacent cells, links them together (Veelders et al., 2010). Film formation depends on activation and regulation of a particular isogenic variant, FLO11. It shows high gene expression, resulting in large numbers of Flo11 glycoproteins on the cell surface (Fidalgo et al., 2006). Expression of the gene is increased in the presence of ethanol and glucose (Ishigami et al., 2006). The hydrophobicity of these proteins results in floating vs. the more typical settling of the clumped cells. Other genes indirectly involved in velum development include BTN2, associated with cellular protein localization (Espinazo-Romeu et al., 2008), and HSP12, encoding one of the heat-shock proteins active during the stationary phase (Zara et al., 2002). Low pH and the presence of biotin (Iimura et al., 1980), pantothenate (Martínez et al., 1997c), and phenolic compounds (Cantarelli, 1989) further favor velum formation.

Yeast aggregation also entraps carbon dioxide generated by yeast metabolism, further increasing buoyancy (Martínez et al., 1997a; Zara et al., 2005). This permits the aggregated cells to float to the surface, forming the velum (flor). Thus, velum development is considered an adaptive mechanism, whereby starved yeast cells gain access to oxygen, permitting ethanol and acetaldehyde respiration (Ibeas et al., 1997a). Sulfur dioxide content is commonly adjusted to approximately 100 mg/L, to limit the growth of lactic acid bacteria. Nonetheless, small numbers of these bacteria, mostly Lactobacillus spp., have been detected during the early stages of sherry production (Moreno-Arribas and Polo, 2008). Thus, if and when malolactic fermentation occurs, it appears to take place early during maturation, and not involve the action of Oenococcus oeni.

Because maturation under a velum involves yeast metabolism, it is often referred to as biological aging. This differentiates the wine’s reductive aging (absence of oxygen under the velum) from the more traditional reductive aging of table wines, and the partially oxidative aging of most fortified wines.

The wine is matured in American oak cooperage. The butts have a capacity of about 490 liters. Typically, they have been used previously to ferment wine. Prior conditioning minimizes oak-flavor extraction that might otherwise mask the fino bouquet. Barrels are left with 10–20% ullage to provide sufficient surface, and favorable growth conditions, for flor development.

During the initial storage (añada), the development of the new wine (sobretablas) is periodically checked to assess its development. It may remain in the añada for from 1 to 2 years. Flor begins to develop and may soon cover the wine. If flor does not form as desired, even with inoculation, the wine is either used for the production of another sherry style or distilled.

During fractional blending, when wine is removed from the youngest criadera, it is replaced from an añada (Fig. 9.35). In each transfer, about one-quarter of the wine (100 liters) is removed and replenished. The transfer frequency depends on development of the wine, as determined by sensory analysis. Typically, transfers occur about twice a year, but may occur more frequently. There are generally four or five criaderas in a fino solera system. There may, however, be considerably more, especially with Manzanilla fino produced in Sanlúcar.

The butts of a criadera are arrayed in rows, in above-ground, spacious buildings called bodegas (Plate 9.17). The floors are usually bare soil, so that they can be easily moistened to maintain a relative humidity of above 60%.

Generally, butts are stacked no more than three to four high. This avoids structural damage to the cooperage. The criaderas in any particular solera series may be housed throughout the bodega. Large firms generally have numerous solera series, in various stages of development. The finished sherry may be, and usually is, a blend of wine from several separate soleras, with different initiation dates.

Each transfer involves combining the fractions from the different butts in each criadera stage, before gentle dispersion to butts in the next older criadera. This helps minimize differences among butts. The transfer process involves a series of siphons that extract the desired proportion of wine from underneath the velum. After blending, the wine is transferred to butts in the next criadera, also under its flor covering. The procedure attempts to disturb as little as possible both the surface flor and the bottom lees. The process is being automated to obviate the arduous task of manual siphoning, blending, and subsequent pouring. In the past, the process was facilitated by several ingenious devices, involving perforated tubes (rociadors) and wedge-shaped funnels. The angled spout (canoas) minimized velum disturbance.

Frequent wine transfer (about every 3 months) is critical to the development and maintenance of an active flor, refreshening the nutrient supply (Berlanga et al., 2004a). Proline is the principal nitrogen source, whereas biotin favors production of a hydrophobic cell wall. Providing a favorable surface area/volume (SA/V) ratio is also important. Leaving the butts with about 20% ullage creates a SA/V ratio of about 15 cm2/L (Fornachon, 1953). The practice provides sufficient contact with the primary carbon and energy sources, and supplies oxygen for respiration. The bung hole is left slightly ajar to allow gradual air exchange. Oxygen is required for the action of yeast mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase, that converts ethanol to acetaldehyde (Millán and Ortega, 1988). Acetaldehyde accumulation often averages between 260 and 360 mg/L. Ethanol metabolism is particularly active during the first few months of velum development. As ethanol is both metabolized and escapes by volatilization, periodic wine spirit addition may be required to maintain the ethanol content at between 15 and 15.5%.

The taxonomic nature of the flor population is still contentious. This may relate as much to changing views of yeast taxonomy as to barrel-to-barrel and winery-to-winery diversity. The dominant flor-inducing yeasts have been variously identified as strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, S. bayanus, Torulaspora delbrueckii, or Zygosaccharomyces rouxii. Recent research suggests that unique strains of S. cerevisiae constitute the majority of flor yeasts (Ibeas et al., 1997b; Esteve-Zarzoso et al., 2004). They all appear to possess a common deletion in their 5.8 S ribosomal gene.

The proportion and genetic characteristics of the dominant yeast strains change during fermentation, and throughout solera aging. For example, the frequency of cells with functional mitochondria (capable of respiration) is highest in flor strains (Martínez et al., 1995). Whether this reflects selection of existing, or mutant strains, is unknown. Flor yeasts also show a higher expression of heat shock protein (HSP) genes, and correspondingly higher resistance to the toxicity of ethanol and acetaldehyde (Esteve-Zarzoso et al., 2001). They also have greater insensitivity to osmotic stress than fermentative strains. In addition, they overexpress SSU1, a gene that encodes for a sulfite pump that translocates sulfite out of the cell. This enhances cellular resistance to sulfur dioxide. Finally, and most distinctively, flor strains show high expression of FLO11 (alternatively called MUC1), encoding for the surface glycoprotein that is responsible for velum formation.

Flor strains often vary in their temperature preference, thickness of the velum they generate, and in their synthesis of volatile compounds, such as esters, higher alcohols, and terpenes. Whether these differences are of sensory significance is unclear (Cabrera et al., 1988). Most yeast vela are a mix of strains and species. Criddle et al. (1981) considered that mixed cultures form more uniform pellicles than pure cultures.

Flor yeasts are critical to the development of fino sherries. In the absence of fermentable sugars, yeast growth depends on a shift to respiratory metabolism. As the film grows, covering the wine, diffusion of oxygen into the wine is restricted. Thus, the redox potential of the wine increases, although the wine is seemingly exposed to air. This, plus yeast-induced inhibition of phenol oxidation, probably explain the wine’s pale color (Martínez et al., 1998; Lopez-Toledano et al., 2002). An alternative, or additional factor, appears to be the action of phenolic compounds on membrane lipids. They favor the adsorption of polyphenolics, notably those colorless intermediates in browning reactions (Márquez et al., 2009).

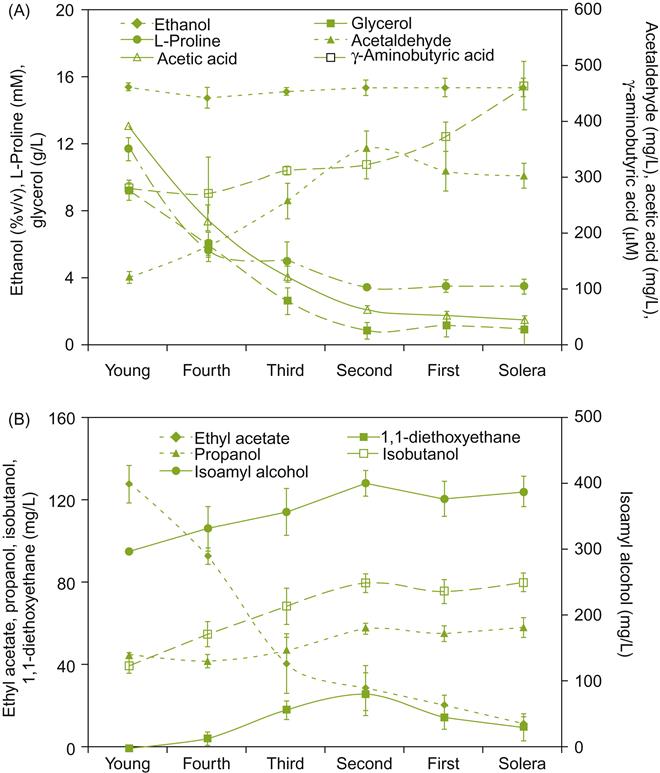

Flor yeasts respire ethanol, glycerol, acetic and several other organic acids, producing acetaldehyde and various aromatic by-products. Examples are 1,1-diethoxyethane, diacetyl, acetoin, 2,3-butanedione, and C4 organic acids (Cortés et al., 1999). During solera maturation, ethanol consumption remains fairly constant (in the range of 5 to 6 L per year) (Martínez et al., 1998). In contrast, glycerol consumption rapidly declines (Bravo, 1984). Its availability is not replaced. Most of the acetaldehyde generated is respired via the TCA cycle by yeast cells at the surface. It reaches its highest concentration during the añada phase, declines early in solera aging, and then slowly rises again (Martínez et al., 1997b). Limited fermentation in the lower, submerged portion of the film probably depends on residual sugars.

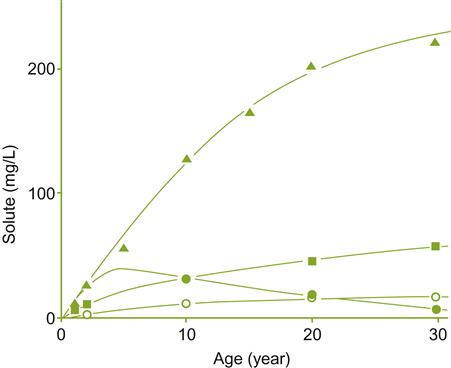

The accumulation of acetaldehyde (not respired during yeast metabolism) gives sherry its oxidized bouquet. Subsequent reaction of acetaldehyde with ethanol, glycerol, and other polyols generates acetals. Of these, only 1,1-diethoxyethane likely accumulates sufficiently to add a ‘green’ note (see Etiévant, 1991). Small amounts of terpenes, such as linalool, cis- and trans-nerolidol, and trans, trans-farnesol are synthesized (Fagan et al., 1981). Several lactones, notably substituted γ-butyrolactones, have been isolated from fino sherries. They are generally regarded as important in the development of a fino character (Kung et al., 1980). The lactone, sotolon, is probably important in contributing to the characteristic walnut-like fragrance of fino sherries. Sotolon has also been isolated from vin jaune, a sherry-like wine produced in the south of France (Martin et al., 1992). Sotolon forms during a slow reaction between α-ketoglutaric acid and acetaldehyde (Pham et al., 1995). Nevertheless, the typical fino fragrance appears to depend on the combined effects of several aromatics, including lactones, acetals, terpenes, and aldehydes. Examples of other chemical changes during solera maturation are provided in Fig. 9.37.

In addition to the oxidative metabolism of film yeasts, volatile compounds are lost through the sides and bung hole of the cooperage. Conversely, the evaporation of water from the butts can increase the concentration of various compounds (Martínez de la Ossa et al., 1987). This could potentially increase the alcohol content by about 0.2% v/v per year (Martínez et al., 1998). Water evaporation for barrel surfaces can be reduced by increasing the relative humidity in the bodega. This is commonly, and most simply, achieved by sprinkling water on the bodega floor.

During maturation, both amino acid and peptide content fall dramatically, especially proline (Villamiel et al., 2008). Tartaric acid, acetic acid and ethanol content also decline. In contrast, the content of higher alcohols increases (Muñoz et al., 2006).

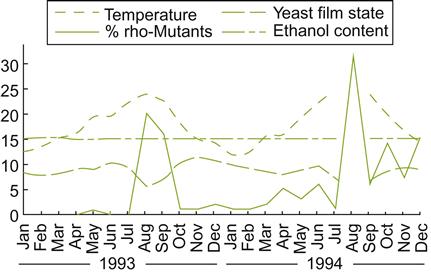

Although flor coverage is commonly complete, being about 3–6 mm thick, yeast activity is not constant. Growth is usually most active in the spring and fall, when the ambient temperatures in the bodega are between 15 and 20 °C. During the winter and summer months, unfavorable temperature conditions slow growth, and flor coverage may become patchy. This is particularly noticeable when temperatures rise above 22.5 °C (Fig. 9.38). This also correlates with an increase in the number of rho° strains (lacking mitochondria). Because these are respiratory deficient, they die and settle down to the lees.

As the velum thickens, lower sections break off and fall to the bottom. Because of yeast autolysis, sediment rarely accumulates to any degree, and the cooperage seldom needs cleaning. Nutrients released by autolysis, notably glucans, fatty acids, amino acids, peptides, and nucleotides are probably important to continued flor growth. Substances released during autolysis are also likely to be important in the development of the typical fino bouquet, similar to sparkling wines.

After maturation is complete, the wine removed from one solera is usually blended with wines from other similar soleras. Subsequently, the alcohol content is adjusted to 16.5% alcohol, or an amount considered appropriate for the export market. Increasing the alcohol content stops any further flor activity. During maturation, the malic acid level falls, which may leave the wine with insufficient acidity. If so, tartaric acid may be added. A polishing clarification and cold stabilization prepare the wine for bottling. Fino sherries are seldom blended with sweetening or color wines. They are sold as dry, pale-colored, aperitif wines.

Despite fino sherries being considered oxidized (due to the presence of acetaldehyde), newly bottled versions do not possess the oxidized character of white table wines. These attributes, or loss of fresh fino attributes, occur only after bottling. Thus, fino sherries are best consumed shortly after bottling. Although uninvestigated, loss of its initial flavor may be due to the use of short, chamfered, T-corks. These may permit significant oxygen ingress. If so, the current shift to RO closures may permit fino sherries to have a much longer shelf-life, allowing more people to have a true experience of its inherent properties. Browning and development of oxidized flavors are accelerated by exposure to light and high-temperature storage (Benítez et al., 2003, 2006).

Amontillado

Amontillado sherries begin development as a fino sherry. However, after transfer through several criaderas, the frequency of transfer is slowed, decreasing the rate of nutrient replenishment. This favors water loss, tending to increase the relative alcohol content. All these features slowly lead to the cessation of flor growth. This can be induced by fortification to reach 17–17.5% alcohol. This also protects the exposed wine from the activity of acetic acid bacteria. In addition, because an exposed wine surface is neither desired nor required, the butts are usually filled. Without flor protection, the wine shifts from reductive to a slow oxidative aging. Thus, it becomes darker in color, and develops a richer, oxidized flavor, associated with aspects derived from the earlier biological (flor) aging. Its character is dominated by the presence of ethyl esters (ethyl octanoate, ethyl butanoate and ethyl isobutanoate), eugenol, and sotolon (Moyano et al., 2010). These and other compounds donate a sensory profile described as spicy, fruity, and nutty (Zea et al., 2008). In comparison with fino soleras, there may be few to many criadera stages in the maturation of amontillado – the number depending on the flavor intended. Due to the extended period in each of the amontillado criaderas, maturation often takes up to 8 years. Most amontillado soleras are initiated intentionally, rather than, as in the past, occurring as if by accident.

When drawn from the solera, amontillado sherries may be sweetened and fortified to meet particular market demands. In Spain, the wine is usually left unmodified. After cold stabilization, and a polishing filtration, the wine is ready for bottling. Amontillados may also be used in preparing cream-type sherry blends.

Oloroso

The first step in producing an oloroso sherry involves fortifying añada wine to about 18% alcohol. This inhibits both yeast and bacterial growth, and makes oloroso maturation less sensitive to temperature fluctuation, as compared to other sherry types. Consequently, the butts are located in areas of the bodega showing the greatest temperature fluctuation. This can vary from as low as 5 °C during winter to almost 40 °C in summer. If stacked together with fino butts, the oloroso butts are on top, where climatic variation is the greatest. The butts are commonly filled to about 95% capacity, and irregular topping limits the rate and degree of oxidation. This may partially explain the minimal increase in acetaldehyde content observed during oloroso maturation. However, an additional reason may be the conversion of acetaldehyde to acetic acid, and its subsequent esterification with ethanol to ethyl acetate. This is suggested by the progressive increase in the concentration of acetic acid and ethyl acetate during oloroso maturation (Martínez de la Ossa et al., 1987).

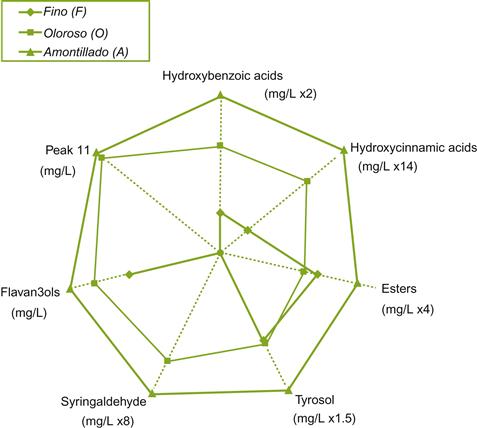

Because of the long maturation in oak, the concentration of phenolic compounds is generally higher in amontillado and oloroso than in fino sherries (Estrella et al., 1986; Fig. 9.39). The higher phenolic content also partially arises from the original añada wine coming from press fractions in the later stages of grape pressing. In oloroso sherries, the most marked changes occur during the first few years of oxidative aging (Ortega et al., 2003). Sugar and alcohol content also rise during maturation. This probably arises from concentration due to water evaporation during the 7 to 8 years in-barrel maturation, that can last up to 14 years. Sugars may also come from the degradation of glycosides in the wood.

There are typically few criadera stages in an oloroso solera. Transfer rates are infrequent, often amounting to only 15% per year. Because fractional blending is limited, the wine shows considerable barrel-to-barrel variation. The cellar master establishes brand consistency through blending.

Although, like all sherries, olorosos are initially dry, they are seldom found that way on the international market. Most are available as cream sherries or their variants. Although predominantly based on olorosos, depending on their formulation, they may also contain some amontillado and fino components. They will typically also possess proprietary amounts of sweetening and color wines, and are usually brought up to about 21% alcohol. Thus, their flavor attributes are a combination of both those changes that occurred during the wine’s oxidative aging, with potentially some flor character, and the characteristics donated by the treatment given the sweetening and color wines. These aspects also explain why their flavor is so stable, even months after the bottle has been opened. After clarification and stabilization, they are ready for bottling. Palo cortado and raya sherries are special oloroso sherries. They are more subtle and rougher versions, respectively.

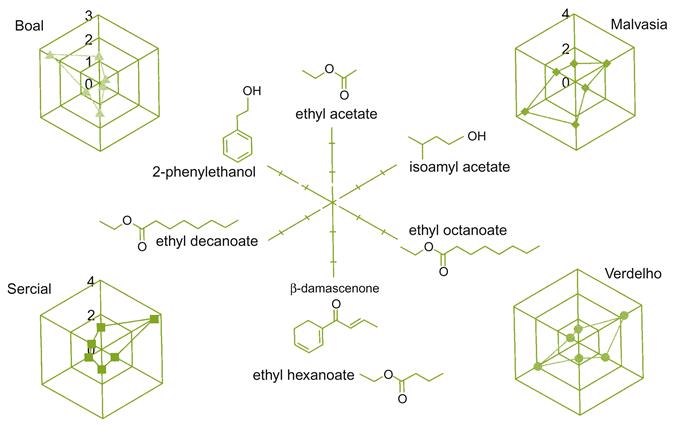

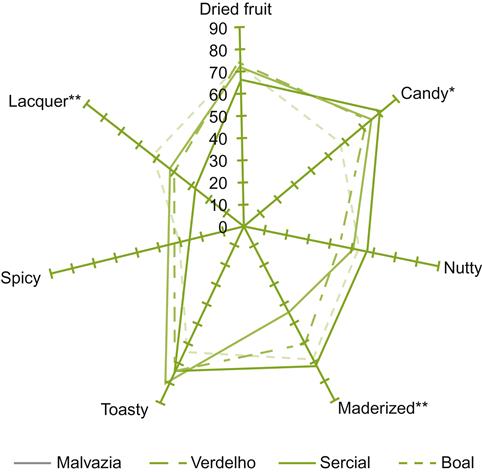

Distinguishing Sensory Differences

For a detailed chemical comparison of all three basic sherry types, see Zea et al. (2001). They differentiate the styles as follows. Finos were distinguished by floral and fruity notes, apparently derived from farnesol, β-citronellol and β-ionone, as well as the presence of cheesy/rancid (butanoic acid), and pungent/apple (acetaldehyde) attributes. The acetaldehyde concentration is often in the 350 to 450 mg/L range. Additional aromatics, at significantly above threshold concentration, were 1,1-diethoxyethane (fresh, fruity, green aromatic aspects) and sotolon (nut and curry notes). In contrast, oloroso profiles were characterized by ethereal and smoky aspects, for example ethyl acetate, and 4-ethylguaiacol, respectively. The latter probably has its origin as a lignin breakdown product, from the oak in which the wine was matured. Amontillados were differentiated by possessing flavor characteristics supplied by both flor (biological) and oxidative aging processes. Consequently, they had the most complex sensory attributes of the three. Most of these attributes develop early during maturation, but appear to continue accentuating, but at a slower rate.

Sweetening and Color Wines

Sweetening is typically achieved by adding one of two special sweetening wines, PX or mistela, although variations are occasionally used (Reader and Dominguez, 2003). PX is juice extracted from sun-dried berries (soleo) of Pedro Ximénez. Extended exposure to sun favors the dehydration of fructose to HMF (5-hydroxymethylfurfural), and the formation of significant accumulations of several henenols, henenals, phenolic alcohols, lactones and other furfurals (Franco et al., 2004). Because the increase in sugar content does not necessarily correlate with the development of the desired flavors, an electronic (e-) nose combined with gas chromatographic analysis has been used to facilitate rapid assessment of the optimal exposure period (Lopez de Lerma et al., 2012). To improve juice extraction, pectinases may be added to the must before pressing. This is reported to improve the product’s sensory quality (Espejo and Armada, 2010). The juice, possessing a marked raisiny flavor, is fortified to about 9% alcohol, allowed to settle, and aged for several months. After racking, the alcohol content is raised to about 18%, and the PX placed in special soleras for further maturation. At maturity, PX is dark in color, possesses about 40% sugar, and is typically used in the formulation of cream sherries.

In contrast, mistela is produced from Palomino grapes, the principal variety used in sherry production. The free-run juice and first pressing are initially fortified to about 15% alcohol, allowed to settle, racked, and fined. The product is subsequently raised to about 17–18% alcohol, and aged in casks or tanks. Mistela is not fractionally blended through a solera system. It generally contains about 16% sugar.

Alternatively, sweetening may be derived from the addition of color wine. This is normally obtained from the second pressings of Palomino grapes. Boiling brings the volume down to approximately one-fifth of its original. The froth that forms during boiling is periodically skimmed off. The product, called arrope, is a thick, dark, highly caramelized, 70% sugar solution. Addition of arrope to fermenting Palomino juice successively slows the rate of fermentation after each addition, until fermentation ceases. It often possesses an alcohol strength of about 8% and contains about 22% sugar. The wine may be raised to about 15% alcohol and be solera-aged. Alternatively, arrope may be added at the end of fermentation (one part arrope to two parts wine). The end product in either case is called vino de color.

European Sherry-Like Wines

The major source of sherry-like wines, other than Jerez, is Montilla-Moriles. It lies about 160 km northeast of Jerez. Its wines were once transported to Jerez for maturation and used in the production of Jerez sherry. This practice is no longer permitted. In Montilla-Moriles, Pedro Ximénez is the predominant cultivar. Grapes of this variety can, without solar drying, yield wines of up to 15.5 to 16% alcohol. Thus, flor tends to develop spontaneously, without fortification.

Fino sherries are produced from a combination of free-run and first press-run fractions. Oloroso sherries are produced from free-run juice plus several press fractions. Fermentation traditionally occurs in large earthenware vessels termed tinajas. These possess capacities between 6000 and 9000 liters. They resemble storage vessels (pithoi), used by the ancient Greeks and Romans. The wines are solera-aged, in a procedure analogous to that used in Jerez.

Small amounts of solera-aged sweet wine are also produced in Málaga, about 180 km east of Jerez. Most Málaga wine is produced without solera aging. Those winemakers who use fractional blending employ fermentation procedures distinct from those practiced in Jerez and Montilla. Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel grapes are harvested at about 23 to 25°Brix. They are then placed on mats and frequently turned to speed drying and overripening in the sun. This is the same as the procedure formerly common in Jerez. The grapes are covered at night to prevent the formation of dew on the surface. Both features reduce the incidence of fungal infection. The process takes 7 to 10 days, in temperatures that often reach above 40 °C. Details on chemical changes that occur during drying can be found in Ruiz et al. (2010). The most marked is an increase in acetoin content.

After a short maceration period, the grapes are pressed. Juice, fortified to 7% alcohol, may be added before fermentation. Fermentation is slow and often incomplete. The resulting wine may have an alcohol level of 15–16%, and a residual sugar content of 160–200 g/L. The wine may be further sweetened with PX and mistela. Solera aging, when employed, occurs without the interaction of flor, in a manner similar to that of an oloroso. The wine may be colored with sancocho, a product possessing a specific gravity of about 1.24, and similar to the color wine of Jerez. Because sancocho is concentrated to only one-third of the original volume, it is lighter in color and less caramelized than color wine. It is added slowly to the fermenting must to supply a distinctive arrope flavor and color. The brownish color comes from Maillard-generated pigments (melanoidins) (Rivero-Pérez et al., 2002). If aged in an oxidative solera system, the wine develops a complex flavor and an astringent aftertaste.

European sherry-like wines, produced outside Spain, include Vernaccia di Oristano and Malvasia di Bosa (Sardinia), as well as vin jaune (Jura, France). The Sardinian wines are flor-matured wines, made from fully mature grapes of the Vernaccia and Malvasia cultivars, respectively. Natural ripening on the vine commonly produces grapes with sufficient sugar content to yield wines of more than 15% alcohol. Thus, the wines often need no fortification to favor flor development.

Vin jaune is usually produced from the Savagnin cultivar, a mild-flavored strain of Traminer. The grapes are harvested late and allowed to dry for several months to develop a high sugar content. The wine is barrel-aged for slightly more than 6 years, without racking (Dos Santos et al., 2000). Flor yeast development occurs spontaneously, or following specific inoculation. Like some other sherry-like wines, its development occurs without fortification. The dry wine, often over 13% ethanol, is stored in tightly bunged barrels, after the completion of malolactic fermentation. Without fractional blending, velum completeness tends to decrease with time. Velum coverage also depends on the cellar temperature. This can vary from 5 °C in winter to 17 °C during the summer. Often a thick lees layer forms on the bottom of the barrel. Yeast autolysis is presumably important to renewed velum development as temperatures warm in the spring. As with other similar wines, the acetaldehyde content rises during aging. It can occasionally reach 600 to 700 mg/L (Pham et al., 1995). Similarly, vin jaune is characterized by the presence of sotolon, at values well above threshold. Traces of diethoxy-1-ethane also appear typical. Additional significant aromatics, recently detected, are abhexon and theaspirane-derived compounds (Collin et al., 2012).

Non-European Sherry-Like Wines

Solera-Aged Sherries

Production of solera-aged wine, similar to that practiced in Spain, is uncommon in the New World. The expense of fractional blending and the prolonged maturation undoubtedly explain this situation. Up to 10 times the volume of wine may be maturing as sold each year using fractional blending.

South African sherries are produced with a form of solera blending, but the details are quite different from those in Spain. Palomino and Chenin blanc (Steen) are the varieties normally used. The juice is inoculated with selected yeast strains, chosen for their fermentation and film-forming habits.

Wine designed to become flor-matured sherries are initially fortified to 15–15.5% alcohol. They are placed, without clarification, in 450 liter butts for 2–4 years. A 10% ullage provides surface for flor development. After the initial maturation, storage of both lees and wine occurs in casks containing about 1500 liters. There are generally two criaderas and one solera stage. Each stage has only one or two casks. Consequently, little blending occurs between transfers. Wine is generally drawn off in 450-liter lots, equivalent to the contents of añada barrels. Due to the proportionally higher evaporation of water through the wood, the alcohol content reaches a level that inhibits flor activity. The wine generated is apparently intermediate in character between a fino and an amontillado.

Wines intended for oloroso production are fortified to about 17% alcohol after fermentation. Subsequent storage occurs for about 10 years in butts without fractional blending. Sweetening mistela, derived from Palomino or Chenin blanc juice, is also fortified to 17% alcohol and matured for upward of 10 years in oak casks. Color wines are produced from arrope, blended into young sherry, and stored in butts for prolonged periods.

In Australia, flor sherries are seldom fractionally blended. After fortification, the wine may be inoculated with a film-forming yeast and matured for upward of 2 years in barrels (~275 liters), or cement tanks (~1000 liters). When the desired flor character has been reached, the wine is fortified to 18 to 19% alcohol. Further maturation occurs in oak for 1–3 years.

Submerged-Culture Sherries

A biological aging procedure, markedly different from that based on the Spanish model, has been pioneered in Australia, California, and Canada. It involves a submerged- culture technique. Respiratory growth of the flor yeasts is maintained with agitation and aeration.

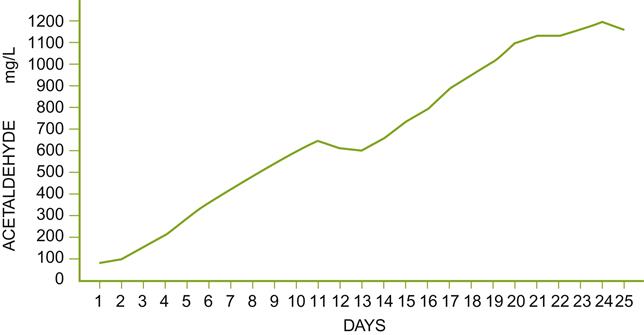

The base wine is fortified to about 15% alcohol, and inoculated with an acclimated culture of flor yeast. Optimal growth conditions include a pH of about 3.2, a temperature of 15 °C, and SO2 contents close to 100 mg/L. Oxygen is provided by bubbling filtered air or oxygen through the wine. The use of porcelain sparging bulbs finely disperses the gas, improving oxygen adsorption, while minimizing the loss of aldehydes and other aromatics. The yeasts are kept suspended and highly dispersed by mechanical agitation. The process has the advantage of rapidly producing high levels of acetaldehyde (Fig. 9.40). By adjusting the duration of yeast action, slightly (~200 mg/L) to heavily (>1000 mg/L) aldehydic wines can be obtained.

After flor treatment, fortification with relatively neutral spirits raises the alcohol content to 17 to 19%. Fortification appears to intensify the flor character. Because the wine generally lacks the complexity and finesse of solera-aged wines, it is customarily used to enhance the complexity of baked sherries (see below), rather than used independently as a beverage. The lack of finesse may result from the absence of the reductive phase that occurs under the flor growth, plus products released during yeast autolysis.

Baked Sherries

Baking has been the most common technique for producing sherries in Canada and the United States. It involves a process that more resembles the production of madeira than it does Jerez sherry. Not surprisingly, the resulting wines more resemble madeira than Jerez sherry or at least used to.

Varieties that oxidize fairly readily are preferred in the production of baked sherries. In eastern North America, the variety Niagara has routinely been used, whereas in California, varieties such as Thompson seedless, Palomino, and Tokay, have typically been used. Both white and red grape varieties may be used. Baking destroys the original color of the wine. Posson (1981) recommends juice possessing a pH no higher than 3.4 for submerged-culture sherries, whereas pH values between 3.4 and 3.6 are suggested for baked sherries.

Slow baking occurs when barrels of wine are exposed to the sun. More rapid and controlled baking is achieved in artificially heated rooms. Heating coils may also be inserted directly into wine-storage tanks. Heating is variously provided by passing steam or hot water through the coils. California winemakers are reported to prefer baking at 49 °C for 4 weeks, rather than the former 10 weeks at 60 °C (Posson, 1981).

Heating induces the formation of a wide variety of oxidative and Maillard products, including furfurals, caramelization compounds, and melanoid by-products. Baking also promotes ethanol oxidation to acetaldehyde (Kundu et al., 1979). Air or oxygen gas may be bubbled through the heated wine to accelerate oxidation.

The desired level of baking may be measured chemically by the production of 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde, or colorimetrically to assess the development of brown pigments. Nevertheless, final decisions are made based on sensory analysis.

After baking, especially by rapid heating, the wine requires maturation to lose some of the resulting strong flavors and rough mouth-feel. Maturation in oak is preferred, with used barrels being employed to avoid giving the wine an oaky attribute. Aging may last for from 6 months to more than 3 years.

Baked wines are always finished sweet. The sweetness may come from fortified grape juice added to a base wine. Alternatively, premature termination of fermentation (by fortification) can retain residual sweetness in the base wine.

Porto and Port-Like Wines

The beginnings of port development, or porto as it is called in Portugal, are unclear. Fortification may have been used by the end of the 1670s. However, this appears to have been to limit spoilage during transport and improve its acceptability, not to preserve sweetness by arresting fermentation early. The latter practice seems not to have become standard until the mid-nineteenth century, but did have earlier predecessors (see Younger, 1966; Unwin, 1991).

The premature termination of fermentation, achieved with the addition of brandy spirits, is essential to modern port production. The retention of a high sugar content, and the higher (fusel) alcohols supplied with the brandy spirits, give port two of its most distinguishing features. The brandy spirits also contribute esters (e.g., ethyl hexanoate, ethyl octanoate, ethyl decanoate) and terpenes (e.g., α-terpineol, linalool). These donate a fruity, balsamic, and spicy profile (Rogerson and de Freitas, 2002). In addition, brandy spirits are rich in aldehyde content, such as acetaldehyde, propionaldehyde, isovaleraldehyde, isobutyraldehyde, benzaldehyde (Pissarra et al., 2005). These not only influence the fragrance, but also contribute to color development in the young wine. They participate in the formation of alkyl-linked anthocyanin/tannin polymers. Subsequent aging and blending differentiate the various port styles.

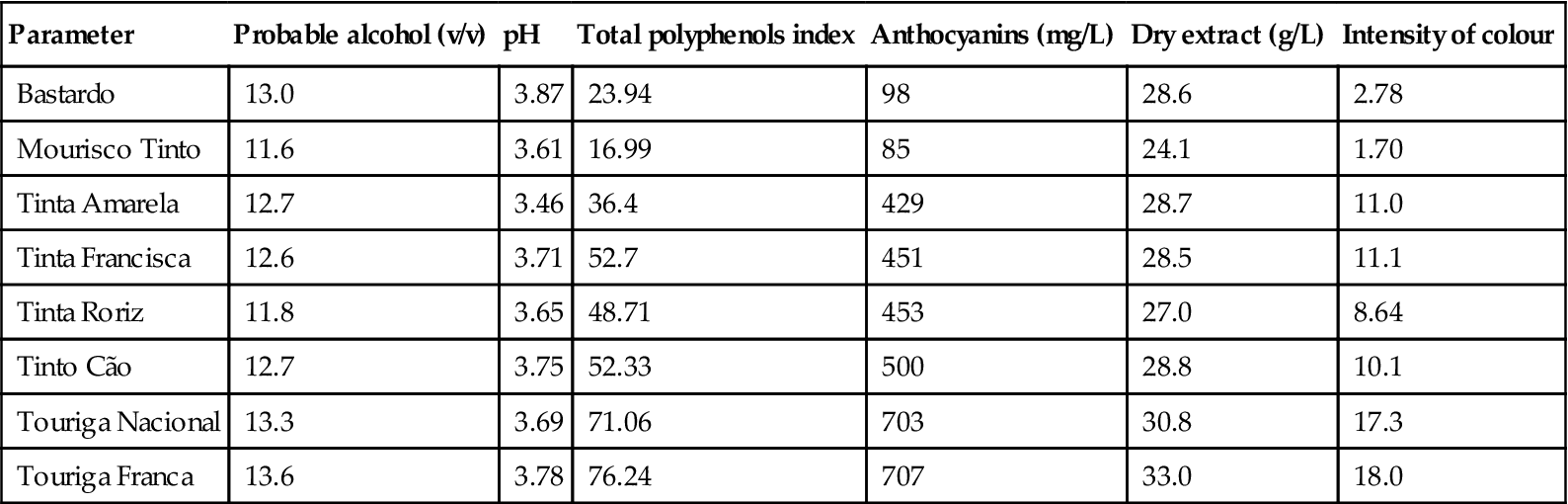

Porto