To further reduce the likelihood of leakage, bottles may be flushed with carbon dioxide before filling (removing the oxygen and nitrogen in air), or be placed under partial vacuum at corking. Partial vacuum (20–80 kPa) minimizes the development of a positive headspace pressure during cork insertion (Casey, 1993).

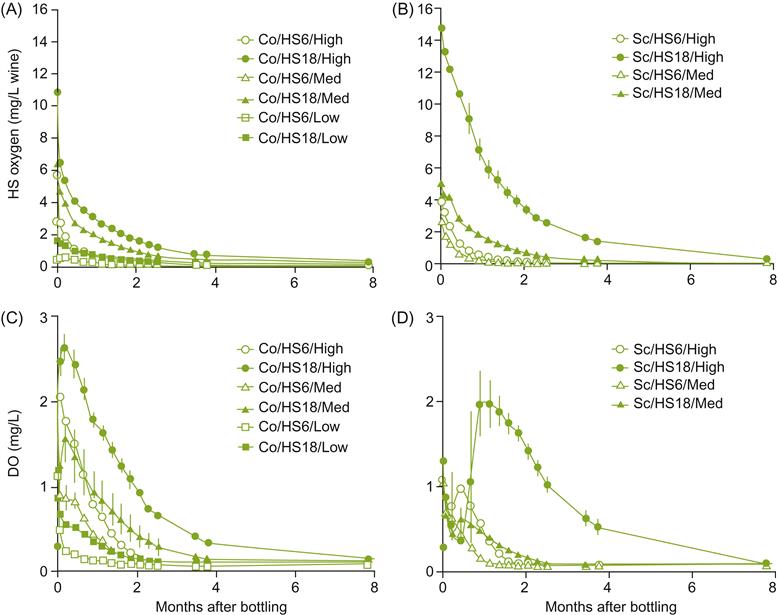

The use of corking under partial vacuum or carbon dioxide has been viewed as having benefits beyond reducing the likelihood of leakage. It might limit the development of ‘bottle sickness,’ presumably by removing most of the 4–5 mg of oxygen that would otherwise be absorbed from entrapped air. However, neither process eliminates the oxygen that can dissolve into wine from air present, and now under pressure, in the lumen of cork cells (Lopes et al., 2007). This could add an additional 2 mg O2 over the next few weeks. However, the rate of oxygen uptake by wine from the headspace in the bottle may be too slow to explain bottle sickness, at least in bottles closed with screw caps or coextruded synthetic corks (Fig. 8.70). This brings into question whether the phenomenon is real or just illusionary. Reports of bottle sickness are anecdotal and have not been verified objectively. Flushing does slow the loss of sulfur dioxide from the wine, by removing oxygen from the headspace. For example, De Rosa and Moret (1983) showed that vacuum and flushing, and vacuum application alone, reduced average SO2 loss after 12 months from 28 to16 mg/liter and 5 mg/liter, respectively. Assessing oxygen content has become much simpler with the advent of a luminescence technology measurement system (Plate 8.15A).

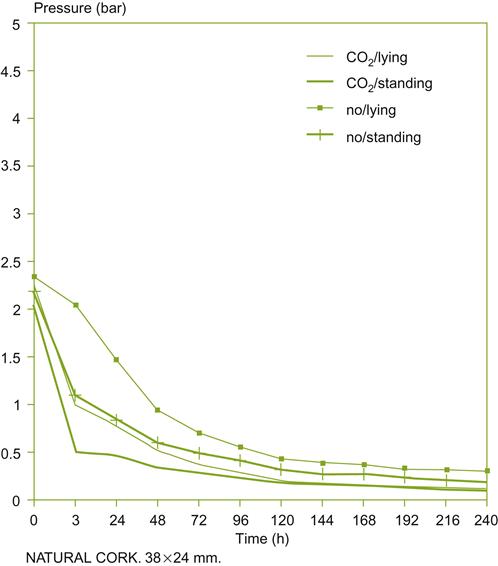

Variation in bottle capacity or fill-volume may be an additional source of seepage problems. Either could leave less than the standard headspace volume. Even with medium-length corks, bottles may possess a headspace volume as little as 1.5 mL after corking. Because wine in a 750-mL bottle can expand by about 0.15 mL/°C, a rapid rise in temperature could quickly result in a significant increase in pressure on the cork (Boulton, 2005). More typically, headspace volumes are in the range of 6–9 mL. In such cases, a rapid rise in temperature by about 20°C would be required to produce a doubling of the pressure exerted by the headspace gases on the cork. Leakage becomes probable at internal pressures above 200 kPa (twice atmospheric pressure). At this point, the net outward pressure begins to equal or exceed that exerted by the cork against the glass. This effect is reduced if the headspace gas is primarily carbon dioxide (which readily absorbs in the wine), but is enhanced if the headspace gas contains primarily nitrogen (which is what remains after oxygen in headspace air is consumed). The effect of rapid volume increase will also be greater if the wine is sweet or supersaturated with carbon dioxide (Levreau et al., 1977). In these situations, the pressure is likely to remain, either because nitrogen gas will not effectively dissolve in the wine or because wine supersaturated with carbon dioxide will absorb further CO2 slowly. Sugar can augment seepage by increasing the capillary action between cork and the glass. Sugar also increases, by about 10%, the rate at which wine volume changes with temperature (Levreau et al., 1977).

Finally, cork moisture content influences the likelihood of leakage. At a moisture content between 6 and 9%, cork has sufficient suppleness not to crumble on compression. The lower end of the scale is preferred for fast bottling lines, whereas the higher end is recommended for medium- and slow-speed bottling lines. Cork within this range also rebounds sufficiently slowly to allow pressurized headspace gases to escape before a tight seal develops. At lower moisture levels, compression and insertion are likely to rupture or crease the cork. At high moisture levels, more gas is likely to be trapped in the headspace (Levreau et al., 1977).

Bottles and Other Containers

Over the years, wine has been stored and transported in a wide variety of vessels. The first storage vessels were probably earthenware, or made from animal skins. The interior of the former were often covered with pitch to reduce their porosity. The sealing properties of pine pitch have been confirmed recently for oil, but it was less effective with wine (Romanus et al., 2009). Examples of pitched, earthenware wine vessels have been discovered dating as far back as 5400−5000 B.C. (McGovern et al., 1996). They have also been excavated from tombs of the earliest Egyptian Pharaohs.

The use of pitch (a complex mixture of oxidized diterpenoid carboxylic acids) in amphoras is carefully described by Pliny (Historia Naturalis 14.27), and has frequently been confirmed by archaeologic remains. Adding pitch involved pouring boiling resins or tars inside the amphora. In the Mediterranean Basin, resins or tars were normally derived from pines, notably Pinus halepensis. In contrast, terebinth (Pistacia atlantica), sandarac (Tetraclinis articulata), and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha) were the standard resin sources in the Near East. Details on the chemistry of pitch can be found in Font et al. (2007).

Later in the Classical Period, technical advancements permitted the production of amphoras that possessed a non-porous lining, and, thus, no longer required to be pitched. The addition of potash and firing at an atypically high temperature (between 800 and 1000°C) produced an inner vitreous glazing (Vandiver and Koehler, 1986).

Amphoras were the standard storage and transport vessel throughout the ancient Greek and Roman world. Their use in the wine trade continued in the Middle East up until at least A.D. 625 (Bass, 1971, see also Kingsley, 2003). They fell into disuse throughout the western Mediterranean after the decline of the Roman Empire. North of the Alps, wood cooperage became the primary wine-storage and -transport vessel. The barrel held its preeminence throughout Europe until the twentieth century, when the glass bottle replaced wood cooperage as the preferred vessel for wine transport and aging.

Glass bottles were produced in limited quantities during Roman times. Petronius, in his Satyricon, mentions plaster-sealed glass wine bottles. An example of a glass wine bottle (ca. 325 A.D.) is located in the Wine Museum in Speyer, Germany (Younger, 1966). The cylindrical 1.5-liter bottle has shoulders possessing two small handles, resembling those found on amphoras. When excavated in 1867, it was sealed with wax and the wine covered with a layer of oil. However, most Roman glass was too fragile for widespread adoption as a wine container. Roman bottles appear to have been more a luxury item used for holding scented oils. In addition, Roman treatises dealing with wine are silent on the use of glass bottles.

The reintroduction of glass as a material in which to hold wine may have begun as early as the 1300s (in Venice, Italy). Subsequent developments permitted the production of clear glass in the 1400s. However, their fragility meant that the bulbous vessels needed to be protected by a covering of reeds, wicker, or leather. This limited their use to transporting wine from cask to table. Their traditional shape and covering are still used by some Italian producers, for example the Chianti and Orvieto fiaschi.

Both accidental advances and coincidental events resulted in improvements in glass manufacture in early seventeenth-century England. Prohibition of the sale of bottled wine in 1636 (due to nonstandard volumes) inadvertently increased the need for bottles. Owners brought their own bottles to retailers for filling from casks. Stoppering created a demand for stronger bottles (Dumbrell, 1983). Perfection of the incorporation of iron oxide into the glass formula, developed by George Ravenscroft in 1675 (Charleston, 1984), produced the now famous ‘black’ (dark olive-green) bottle. The advantages of the greatly enhanced strength of these new bottles soon lead to the adoption of similar production techniques throughout Europe, beginning in the latter part of the 1600s and early 1700s (Polak, 1975). Although unknown at the time, the glass coloration also protected the wine from exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

A 1715 edict by James I of England, forbidding the use of wood in glass furnaces or brick kilns, lead to coal replacing wood. England was fortuitous in having an abundant supply of coal near the soil surface, easing extraction. Not only did coal provide a higher and more sustainable heat, but it also incidentally supplied sulfur dioxide. A surface reaction between sulfur dioxide and sodium oxide in the glass formed a strengthening layer of sodium sulfate (Doyle, 1979). The use of a bellows, ascribed to Sir Kenelm Digby, permitted the production of even higher heat. This allowed reducing the potash and lime content in the glass mix. The cumulative effect of these separate advances was the production of glass that was not only much darker than Venetian glass, considerably stronger, and less expensive to generate, but also easier to produce in a semi-industrial fashion. Elongation and flattening of the sides initiated the conversion of the original bulbous (‘onion’) bottle into its now familiar cylindrical shape. This transition occurred gradually between 1720 and 1800 (Dumbrell, 1983; Jones, 1986). This coincides with the discovery of the benefits of bottle-aging wine that these bottles facilitated.

After the decline in the use and production of impervious amphoras, and before the widespread adoption of sulfur dioxide as a preservative, beginning in early 1700s, most wines had a short life. Except for some high alcohol wines from the southeastern Mediterranean (notably Cyprus), most wines were best consumed within 1 year of production. Most of the wine was made from the free-run juice as most small producers did not have access to effective presses. For example, most medieval bordeaux (claret) was called vin d’une nuit – it received only short exposure to the skins, after being trodden. The name claret denotes that it was more like a rosé than a red wine. de’Crescenzi (~1303–1309) reported that better-quality wine tended to last for no more than 1–2 years. Lower-quality wine usually had spoiled by the summer following production. This is reflected in the price of year-old wine often dropping to half or less than that of newly vinted wine.

The ability of wine to avoid rapid spoilage depended on storage in large-volume cooperage (von Rohr, 1730). Famous examples are the gargantuan Strasburg and Heidelberg Tuns (1472 and 1591, respectively). The latter had a capacity of 17,000 hL. The activity of acetic acid bacteria would have been markedly reduced by the minimal diffusion of oxygen into such huge volumes of wine. When wine was removed, the volume was replaced with newer wine (almost solera-like), or occasionally replaced with stones, to maintain a minimal ullage.

The benefits of extended aging, made possible in cork-stoppered glass bottles, appear to have been discovered accidentally, possibly associated with transport of wines such as port to England and tokaji to Poland. At the very least, the development of more cylindrical shaped bottles (Dumbrell, 1983) permitted their storage horizontally. As Hugh Johnson (1989) deftly notes: ‘All this was not even a gleam in the eye of the bottle makers of the 16th century.’

During the same period, there was the concurrent evolution of many of the distinctive bottle designs that still characterize particular wine regions. Nevertheless, the extensive use of bottles for wine transport came much later. Bottles were essential only for the transport of sparkling wine and the development of port, notably the precursors of vintage port. Bottles came to supplant barrels as an increasingly important transport container in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Despite the clarity, inertness, and impervious nature of glass, glass bottles have their drawbacks. Because of the various shapes, sizes, and colors used in modern commerce, reuse is cost-effective only for a small portion of the market. Consequently, bottles create a considerable disposal problem. In addition, once opened, wine conservation is difficult. A noticeable modification in sensory attributes may become evident within several hours. Although dispensing systems (see Plate 11.2) replace the apportioned wine with an inert gas (nitrogen or argon), they find use principally in restaurants. They are too expensive for the average consumer. As a consequence, new containers such as bag-in-box or carton packaging have replaced bottles for many standard wines, and for house wines in most restaurants.

Glass Bottles

Despite the limitations of glass, it has many advantages over other materials for storing wine. Its chemical inertness is especially useful in aging premium wines. Although trace amounts of sodium, chromium, and nickel may dissolve into wine, the levels normally involved are infinitesimal. Changes in glass formulation may increase the amount of chromium extracted from 1 to 4 μg/liter (Médina, 1981). Glass is also impermeable to gases and resists all but rough handling.

The transparency of most glass to near-ultraviolet and blue radiation is a disadvantage, but can be corrected by the inclusion of metal oxides. The primary disadvantages of glass are its weight and the energy required in its manufacture. This has led to an evaluation of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) plastic wine bottles. PET has many of the qualities of glass, for example moldability, transparency, and impermeability, but is lighter, less breakable, easier to recycle, and incurs lower production costs. PET plastic wine bottles can be produced with gas barriers as well as oxygen scavengers, in three- or five-layer versions. Comparative studies on the oxidative stability and sensory quality of wine in PET vs. glass bottles show they are essentially equivalent when formulated with an oxygen scavenger (residues of 3-hexenedioic acid and terephthalic acid) (Giovanelli and Brenna, 2007; Mentana et al., 2009). Data from Ghidossi et al. (2012) was less positive for the bordeaux white wine than for the bordeaux red wine tested, but may relate to the PET bottle used. Details on the oxygen permeability of PET and PET-flexible packaging films can be found in Lange and Wyser (2003). Another alternative is poly-lactic acid (PLA) (Pati et al., 2010). Combined with an oxygen scavenger, it appears acceptable as a glass replacement for wine with a short shelf-life, such as most carbonic maceration (nouveau) wines. It has the additional advantage of being biodegradable.

Production

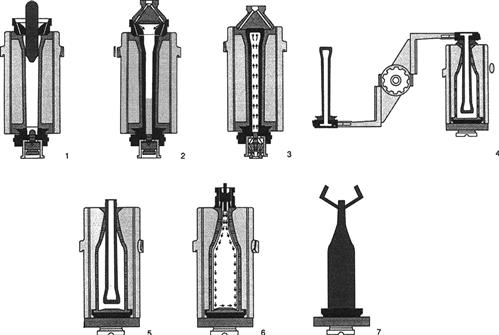

Bottle glass is formed by heating sand (largely silicon dioxide), soda (sodium carbonate), lime (calcium oxide), and small amounts of magnesium and aluminum oxides to approximately 1500°C. During manufacture, an appropriate amount of molten glass (parison) is removed from the furnace and placed in the upper end of a rough (blank) bottle mold (Fig. 8.71). Compressed air forces the molten glass down to the bottom of the mold, where the two portions of the neck mold are located. Subsequently, air pressure from the center of the neck mold blows most of the glass back into the configuration of the blank mold. The procedure establishes the finished shape of the neck. The blank mold, containing the lower portion of the neck mold, is opened and removed. The outer stiff layer of glass touching the mold maintains the shape of the blank mold for its transfer to the finishing (blow) mold. The remaining portion of the neck mold (neck ring) is used to raise and invert the bottle, positioning it between the halves of the blow mold. The bottle is released from the neck ring just before closing the halves of the blow mold.

The glass is reheated to bring it back to a moldable temperature. Compressed air, blown in via the neck, drives the glass against the sides of the blow mold. At the same time, a vacuum, created at the base of the mold, removes trapped air. These actions give the bottle its final dimensions. After a short cooling period, to assure retention of the finished shape, the bottle is removed from the blow mold.

During production, various parts of the bottle cool at different rates. This creates structural heterogeneity and areas of weakness. To release these structural tensions, the bottle is annealed at approximately 550°C. After sufficient annealing, the glass is slowly cooled through the annealing range, and then rapidly down to ambient. During annealing, sulfur is typically burned to produce a thin layer of sodium sulfate on the inner surfaces of the glass. The associated diffusion of sodium ions to the glass surface increases its chemical durability. Alternatively, a thin coating of titanium or other ions may be added. Both procedures harden the surface of the glass and minimize lines of weakness.

Historically, bottles were produced by gathering the parison on the end of a blowpipe. It was rolled (marvered) on a flat stone or metal surface to develop its rough shape, as the worker blew into the blowpipe. The glass was periodically reheated in the furnace during the process as necessary. In early examples, the bottle was left with its inherent, rounded, blown shape. However, bottle shape soon evolved into a mallet form. The flat bottom and more parallel sides allowed the bottle to stand upright more steadily, and facilitated horizontal storage.

After establishing the basic shape, but while still malleable, a small dollop of molten glass on a pontil rod was attached to the base of the bottle. Once attached, the worker pushed the pontil rod gently into the base, forming an indentation (punt). Alternatively, the indentation was made with a rounded mollette, before the pontil rod was attached at the base. The punt originally had several functions. It held the bottle while the blower separated (cut) the blowpipe from the bottle neck. For the older, onion-shaped bottles, the punt also produced a more or less flat bottom, allowing the bottle to sit upright on a table or other level surface. Furthermore, the punt positioned the rough edges of the pontil scar out of harms way. The pontil scar was produced when the bottle was snapped off the pontil rod. For more details see Lindsey (2012).

Some of these aspects of bottle production still have remnants in current bottle design. The punt is a common example. The feature is now used by sommeliers to elegantly, but perilously, dispense vinous delight into customer glasses. It would never have been so used originally. To do so would have done considerable damage to the dispenser’s thumb. The lip is also a vestige of the past. In its more prominent, former self, the lip kept the cork close for reinsertion – a string being tied around both stopper and bottle neck. Bottles were primarily used for transporting wine from barrel to table in pubs. Subsequently, bottles also came to be used by owners when they went to wine retailers. To facilitate recognition, bottles often had glass seals affixed to the side, identifying the owner. This is the original use of the seals, occasionally employed as a marketing tool on modern wine bottles.

With the development of wooden, and later metal, molds, the blower could create a diversity of shapes with more standardized volumes. After the glass had taken the shape of the mold, and while still attached at the neck to the blow pipe, the bottle was slowly turned in the mold. This eliminated the seam where the two sides of the mold met. Because the glass was still only semi-solid, curved stress lines developed in the neck. These are visible in old, hand-blown wine bottles. Finally, the blow pipe was cut off and a small amount of molten glass positioned around the neck. It was molded to form the lip, often with a pair of bladed forceps. Besides its original function, as an attachment site for the cord that held the cork, it also provided extra strength to the neck (useful during stoppering). Finally, the bottle was placed in a special annealing oven (lehr) to relax stress in the glass. Further details on the history of bottle manufacture can be found in Jones (1971), Polak (1975), Dumbrell (1983), and Lindsey (2012).

Shape and Color

Bottles of particular shapes and colors are associated with wines produced in several European regions. These often have been adopted in the New World for wines of analogous style, or to imply similar character. Unique bottle shapes, colors, and markings also are used in marketing to increase consumer awareness and recognition of particular wines.

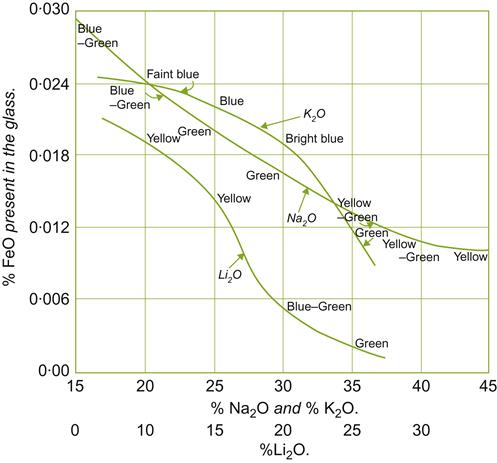

Clear glass is typically produced by adding sufficient magnesium to decolorize iron oxide contaminants that commonly occur in sand. Small amounts of iron, manganese, nickel, and chromium oxides may be added to give the glass a desired color. Ferric and ferrous oxides (Fe2O3 and FeO) often give glass a yellow to green color – the shade being influenced by the redox potential, degree of hydration, presence of other metals, and the chemical nature of the glass (Fig. 8.72). Amber is often generated by maintaining the reducing action of sulfur during glass fusion; brown by the addition of manganese and nickel; and emerald green by the incorporation of chromic oxide (CrO3). Adding chromic oxide under oxidizing conditions, or vanadium pentoxide (V2O5), greatly increases ultraviolet absorption (Harding, 1972).

An alternative to glass coloring is to apply an outer colored or textured coating. This technique has several advantages, other than the wider range of colors possible. The coating typically provides improved abrasion and impact resistance, and facilitates recycling (the coating melts off, leaving clear glass for processing). Even more significant is the development of a coating that absorbs ultraviolet radiation. This permits clear viewing of the wine’s inherent color, without risking light-induced oxidation or spoilage. In addition, the coating can be applied to any shape or bottle size. It is considerably less expensive than changing the color formulation of the glass.

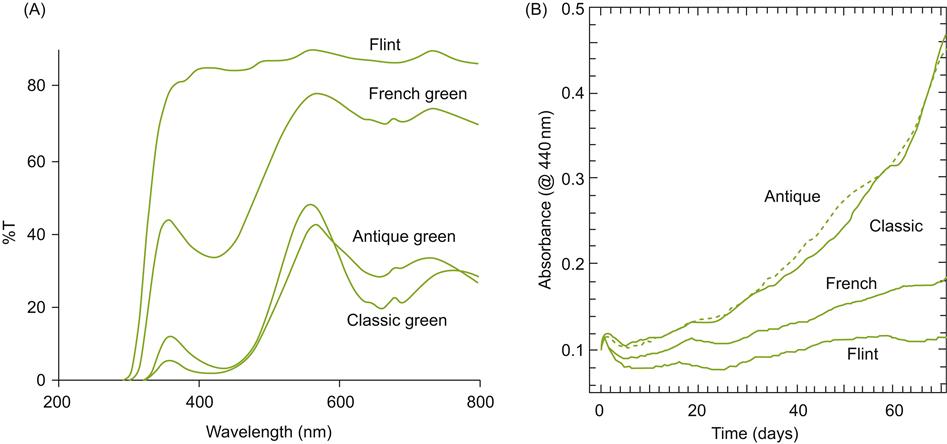

In general, bottle color and shape appear to have often been influenced more by marketing and tradition than appropriateness for aging, storage, or transport. This especially applies to white wines, those most sensitive to light exposure (Macpherson, 1982). They are often sold in clear or light-colored bottles, for example flint and French green glass. These absorb neither blue nor ultraviolet radiation effectively (Fig. 8.73A). Although counter intuitive, Maury et al. (2010) found that Sauvignon blanc wines, bottled in darker glass that absorbed more radiation in the blue and ultraviolet, were the most susceptible to browning (Fig. 8.73B). This result may be due to the destruction of xanthylium-based pigments involved in browning on exposure to light (George et al., 2006).

In contrast, bottle neck design has depended primarily on pragmatic issues, such as the type of closure (e.g., cork, RO, glass) or reducing the likelihood of dripping. Still table wines can use plain necks, because they require only a simple cork or RO closure. Sparkling wines, however, require a more substantial lip, to secure the restraining wire mesh for the stopper.

Bottles of differing filling heights, and permissible capacity variations, are available. Bottles with lower filling heights and smaller volume variation tend to leave more headspace between the wine and the cork. By providing more space (accommodating temperature-induced wine expansion), the bottles are less susceptible to leakage.

Preparation for Bottling

Just before bottling, the wine is frequently given a final polishing filtration and a dose of sulfur dioxide. The latter is added primarily for its antioxidative properties (Waters et al., 1996b). For white wines, sulfur dioxide is typically supplied at a concentration sufficient to achieve (after equilibration) a free SO2 content in the range of 25–40 mg/liter. Where bottles are not flushed with carbon dioxide or filled under vacuum, the headspace may contain up to 5 mL of air. In such situations, an additional 5–6 mg of free SO2 is required to bind the approximately 1.25 mg of oxygen in the headspace. Additional oxygen dissolves out of the cellular voids or fissures of the cork.

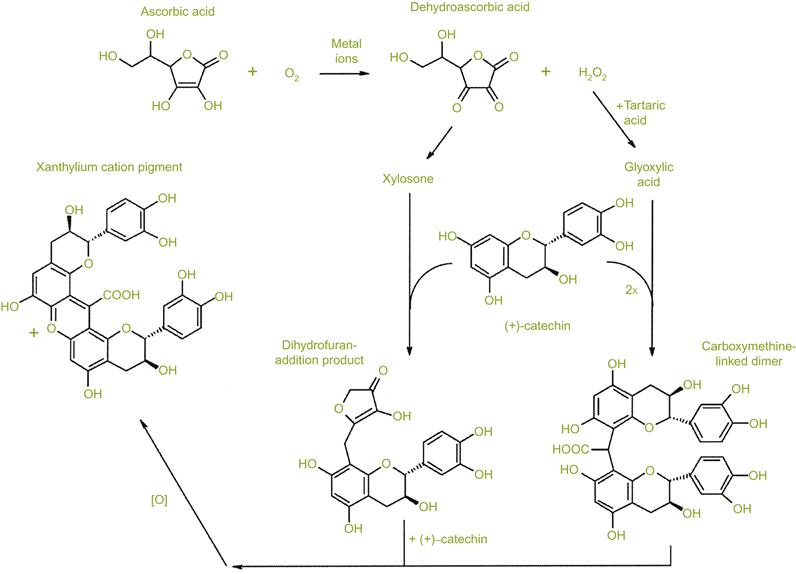

In addition to sulfur dioxide, ascorbic acid has often been added as supplemental protection against oxidation. However, a by-product of this reaction is hydrogen peroxide. One of the presumed benefits of their combined addition has been the ability of sulfur dioxide to react with hydrogen peroxide, reducing it to water. Nevertheless, Peng et al. (1998) found that with or without sulfur dioxide, ascorbic acid enhanced, rather than diminished, the browning potential of white wines. A proposed model that could explain the production of yellowish/brown xanthylium pigments is given in Fig. 8.74. Because many of these investigations involve model wine conditions, and because of the diversity of results, the relative beneficial/detrimental influence of ascorbic acid addition remains unsettled.

The antioxidant properties possessed by sulfur dioxide include: reducing quinones back to diphenols; binding with quinones (preventing their involvement in the formation of brown polymeric pigments); formation of sulfonates with carbonyl compounds (inhibiting their oxidation to brownish pigments as well as generating a nonvolatile complex with acetaldehyde); and bleaching existing pigments.

Browning appears to partially involve the oxidation of colorless xanthene to yellowish xanthylium compounds (Bradshaw et al., 2003). In addition, metal ions (e.g., ferric ions) can catalyze catechin dimers, linked through glyoxylic acid, to yellow compounds (Oszmianski et al., 1996). Although most oxidative browning is considered to involve flavonoids, the precise chemical nature of the pigments involved is incompletely understood. Studies by Lutter et al. (2007) are beginning this investigation.

Filling

After a hot-water rinse, bottles are steam-cleaned and allowed to drip dry before filling. Although cleaning is always essential, sterilization is generally unnecessary. The microbial population of new bottles is usually negligible, and consists mainly of species unable to grow in wine. In addition, the existing microbial population of the wine is often considerably higher than that of the bottle. A discussion of the various sources of microbial contamination during filling can be found in Neradt (1982).

Sterilization is only required for sweet or low- alcohol wines, or when recycled bottles are used. With hot water (or steam) the surface temperatures must reach and stay at least 82°C for at least 5 min, and for about 20 min to be absolutely safe. Alternatively, the availability of small ozone producers has permitted ozone bottle sterilization to become more cost-effective. The one significant drawback to ozone’s use is its tendency to damage components that might be composed of rubber or use silicone sealants.

Various types of automated bottling machines are available (Plate 8.16). Some operate by siphoning or gravity feed, whereas others use pressure or vacuum. Siphoning and gravity feed are the simplest but slowest. Pressure and vacuum fillers are more appropriate for rapid, automated, filling lines.

Regardless of the machine, precautions must be taken against contamination with spoilage microorganisms. The equipment needs to be flushed and disinfected, both before and after each use. The growth of microbes in bottling equipment can contaminate thousands of bottles. It is not just the simple growth of organisms, such as Brettanomyces, that is a concern, but their ability to develop biofilms in bottling equipment. Biofilms are sticky colonies that adhere tenaciously to surfaces (as occurs in plaque on teeth). They form crusts that protect the interior cells from disinfectants, including heat.

Precautions must also be taken to minimize oxidation during filling. This is best achieved by flushing the bottles with carbon dioxide before filling, or filling under a vacuum. Alternatively, the headspace may be flushed with carbon dioxide after filling. The amount of oxygen contained in headspace air can amount to eight times that absorbed during filling.

Bag-in-Box Containers

Bag-in-box technology has progressed dramatically from its initial start as a means of marketing battery fluid. Subsequent developments have found wide application in the wine industry. Because the bag collapses as wine is removed, its volume is not replaced with air (or an inert gas as in a wine dispenser). This permits wine to be periodically removed over several weeks without a marked loss in quality (aromatics do not escape from the wine into the headspace, as occurs when wine is stored in a partially empty bottle). This is a highly desirable feature not available in any other form of wine packaging. The benefits and convenience of bag-in-box packaging is credited with expanding the wine market in regions without an established wine culture. In some countries, such as Australia, more than half the wine may be sold by the box (Anderson, 1987). Bag-in-box packaging is also ideally suited for ‘house wine’ sold in restaurants, especially large 10- to 20-liter sizes.

Wines in bag-in-box packaging tend to show little noticeable loss in sensory quality for 9 months or longer, especially when kept at cool temperatures (Hopfer et al., 2012). However, white wines appear to be much more sensitive than red wines to quality deterioration (Ghidossi et al., 2012). Nonetheless, 1 year is usually adequate for wines that require no additional aging, and have high turnover rates. In addition, the limited shelf-life is of insignificance to the majority of consumers. They typically consume the wine within a few days or weeks of purchase and take wine only sporadically and/or in relatively small quantities. Wine so consumed will retain its qualities far longer than in a partially opened bottle.

To facilitate stacking and storage, as well as protection, the bag is housed in a corrugated or solid fiber box. A handle permits ease of transportation. The large surface area of the box also provides ample space for marketing information and attracting consumer attention.

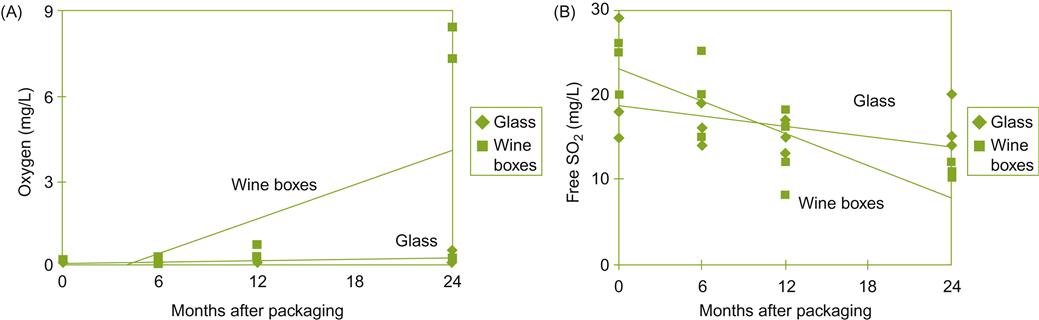

No single membrane possesses all the features necessary for a collapsible wine bag. The solution has been the development of a two-membraned enclosure (Arch, 1997; Buiatti et al., 1997). The outer barrier often consists of a 12-μm metallicized layer of PET, sandwiched between two layers of polyethylene (each 40–50 μm thick). This slows the loss of sulfur dioxide and aromatic compounds, and limits the inward diffusion of oxygen (Fig. 8.75). Of a series of barriers tested, aluminum-laminated barrier film was found the least O2 permeable (Sundell et al., 1992). The inner barrier is a single layer of low-density polyethylene or ethyl vinyl acetate (50 μm thick). It provides the necessary protection against flex cracking. Most modern plastic films are inert to wine and do not affect its sensory characteristics. Eliminating amide additives has removed a former source of off-odors. Polyethylene does absorb ethanol, increasing its crystallinity and limiting the absorption of volatile compounds. Nonetheless, it can rapidly absorb some aromatics, for example 2-phenylethanol and ethyl hexanoate (Peyches-Bach et al., 2012).

Taps come in a variety of styles. Each has its potential problems, such as a tendency to leak, relative permeability to oxygen, and expense. The tap is considered the primary source of oxygen ingress in bag-in-box packaging (Armstrong, 1987; Doyon et al., 2005). Uptake rates can apparently range from 0.02 to 1 mL/m2/day (Reeves and Malcolm, 2009).

To minimize oxidation, the bags are placed under vacuum before filling, and the headspace is charged with an inert gas after filling. To protect the wine against microbial spoilage, and limit oxidation, the wine is usually adjusted to a final level of 50 mg/liter sulfur dioxide before filling.

Wine Spoilage

Cork-Related Problems

The difficulties associated with off-odor identification are well illustrated by cork-related faults. The origins of these faults are often as diverse as their chemical nature may be unknown. Even experienced tasters may have great difficulty accurately recognizing faults, especially against the aromatic background of different wines. The situation becomes even more complex if a wine is affected by more than one fault. Combinations may influence both the individual quantitative and qualitative sensory attributes of a fault. Thus, most off-odors can be identified with confidence only with sophisticated analytic equipment. Much has been learned in the past few decades, but considerably more needs to be known to reduce their incidence.

Although several cork-derived taints have a ‘musty’ or ‘moldy’ odor, others do not. Therefore, cork-related taints are usually grouped by presumed origin. Some off-odors come from the adsorption of highly aromatic compounds in the environment. Other taints originate during cork production, notably 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (TCA). Even some glues used in producing sparkling wine corks have been implicated in off-odor production (i.e., butyl acrylate) (Brun, 1980). Finally, microbial infestation can be an important source of cork-related taints. Because several of these problems have already been discussed in the section on ‘Cork’ above, consideration here will be limited to microbially induced spoilage.

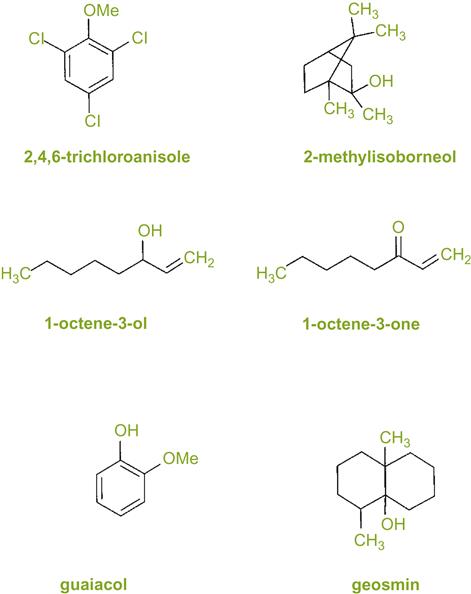

In a study of tainted wines (Simpson, 1990), the most frequent off-odors detected were derived from TCA (86%), followed by 1-octen-3-one (73%), 2-methylisoborneol (41%), guaiacol (30%), 1-octen-3-ol (19%), and geosmin (14%) (Fig. 8.76). Each compound has its own, somewhat distinctive, odor and may not be present at concentrations sufficient for easy recognition. In about 50% of the wines, TCA was considered the most intense off-odor. In a recent study, with and without obvious off-odors, geosmin was much more frequently detected than TCA (Weingart et al., 2010). Many wines possessed known off-odors at above-threshold values, but their effects were not detected sensorially, presumably masked by other constituents.

Although TCA is considered the principal corked taint, its musty chlorophenol odor is different from the putrid butyric smell originally ascribed to corked wine (Schanderl, 1971). The pesticide PCP, from which TCA is often thought to be derived, began to be used only in the 1930s. Examples of wine described as ‘corky’ go back to at least 1903 (Anonymous, 1903). Although apparently no longer observed, the butyric off-odor has usually been associated with ‘yellow stain’ – an infection thought to be induced by Armillaria mellea. Sections of cork infected by A. mellea, at least in recent times, have been found to be contaminated by TCA and additional moldy or mushroomy off-odors, uncharacteristic of healthy cork (Rocha et al., 1996a). Conversely, Lefebvre et al. (1983) have associated old incidences of les goût de bouchon with infection by Streptomyces spp. Commonly isolated saprophytes from cork do produce typical fungal odors (Barreto et al., 2011). Neither these fungi nor Streptomyces are characterized by producing a putrid, butyric odor.

Moldy odors may originate from bacteria, various molds, and occasionally yeasts growing on cork slabs. Jäger et al. (1996) suggested that contamination was most likely during seasoning of the bark or the storage of finished stoppers in plastic containers. Contamination due to fungal growth after insertion is unlikely. The acidic, low nutrient, and anaerobic conditions of the bottle severely restrict most microbial metabolism.

Because nonselective media are commonly used when isolating organisms from cork, it is difficult to assess whether the microbes isolated are members of an indigenous cork flora or simply accidental contaminants. Nonselective culture media favor the growth of fungi that grow rapidly and/or produce large numbers of spores. It may be the equivalent of adding a teaspoon of woodland soil to a pot of sterilized soil to assess the significant inhabitants of a forest. Regardless of origin or role, several common fungal and bacterial saprophytes are capable of producing moldy- or musty-smelling compounds. Because microorganisms require moist conditions for growth, control is commonly attained by keeping the moisture content of corks below 8%. Sulfur dioxide added to plastic storage bags further minimizes the likelihood of microbial growth. Corks can be sterilized by exposure to gamma radiation (30 MR for 30 min) (Marais and Kruger, 1975). This has been recommended to prevent microbial tainting during storage (Borges, 1985), and reduce the contamination by TCA (Pereira et al., 2007). Valuable as these procedures are, none address the problem of off-odors produced in the bark before harvesting or subsequent seasoning.

Examples of musty- or corky-smelling compounds produced by common fungal saprophytes (such as Penicillium and Aspergillus) include 3-octanol, as well as mushroom- or metallic-smelling 1-octen-3-one and 1-octen-3-ol. Metallic sensations may also arise in the mouth from metal-induced oxidation of lipids (Forss, 1969; Swoboda and Peers, 1978). In addition, several Penicillium and Streptomyces spp. produce musty-smelling sesquiterpenes, notably geosmin (Larsen and Frisvad, 1995). Geosmin has been shown to occur in wines at up to 300 ng/liter (Darriet et al., 2000). Its earthy odor becomes detectable at about 80 ng/liter. Nevertheless, its long-term significance in tainting wine is in doubt, due to its short half-life in wine (Amon et al., 1989). The potential role of Penicillium in the synthesis of TCA has already been noted. Additional corky taints are suspected to come from the growth of fungi on cork (e.g., Trichoderma harzianum) (Brezovesik, 1986). Species of Streptomyces, as well as Bacillus subtilis, could taint cork by metabolizing vanillin (derived from lignins) to guaiacol (Lefebvre et al., 1983; Álvarez-Rodríguez et al., 2003). Guaiacol possesses a sweet, burnt odor.

Most fungi isolated from cork can also be found in bark taken directly from the tree. In contrast, Penicillium roquefortii appears to be a contaminant typically found in wineries. It has seldom been isolated from corks prior to delivery and storage in wine cellars. It is one of the few organisms that can occasionally grow through cork in bottled wine (Moreau, 1978). Other commonly isolated fungi, such as Penicillium glabrum, P. spinulosum, and Aspergillus conicus cannot grow in contact with wine. Thus, the lower two-thirds of a cork seldom yield viable fungi after a few months in-bottle (Moreau, 1978). Direct observation of cork from a 61-year-old bottle showed fungal growth had penetrated only 70% of the cork’s length (Jäger et al., 1996). Personal investigation confirms the rarity of fungal growth in and through cork stoppers.

Among fungi growing on or in cork, few are known toxin producers. The major, potentially toxigenic, species is P. roquefortii (Leistner and Eckardt, 1979). Whether the strains of P. roquefortii that grow on cork are toxigenic and whether the toxin, if produced, seeps into wine have not been investigated. The major aflatoxin-producing fungus, Aspergillus flavus, has not been isolated from cork. Whether Aspergillus carbonarius, the major source of ochratoxin A, can grow on or in cork also remains uninvestigated.

Fungal growth on the upper surface of corks in bottled wine,1 so common in the past, was favored by moisture retention under unperforated lead capsules. Although growth rarely progressed through the cork, the production of organic acids favored capsule corrosion. Corrosion eventually contaminated the neck and upper cork surface with soluble lead salts. This knowledge is one of the principal reasons that have led to replacing lead-tin capsules with those made of aluminum or plastic. These are either perforated or insufficiently adherent to develop moisture conditions favorable to fungal growth.

Yeasts have seldom been implicated in cork-derived taints. Exceptions, however, may involve Rhodotorulaand Candida. Both have been isolated from corks of tainted champagne (Bureau et al., 1974).

Although the importance of cork as a source of spoilage bacteria has been little investigated, the presence of microorganisms on or in cork seems both highly variable and generally low. The most frequently encountered bacterial genus is Bacillus. This is not surprising. It produces one of the most highly resistant of dormant structures – endospores. Being such a widely dispersed and resistant organism, the isolation of Bacillus may indicate nothing more than its presence as an aerial-derived contaminant. Nevertheless, several Bacillus species have been associated with spoilage. B. polymyxa has been implicated in the metabolism of glycerol to acrolein, a bitter-tasting compound (Vaughn, 1955), and B. megaterium has been associated with the presence of unsightly deposits in brandy (Murrell and Rankine, 1979).

In addition to cork-related taints, cork can donate a slightly woody character to wine. This is derived from naturally occurring aromatics extracted from cork, of which more than 80 have been isolated (Boidron et al., 1984). Many of the compounds are similar to those isolated from oak used in barrel maturation. This is not surprising. Cork comes from oak, but in this case Quercus suber. Nevertheless, the donation of a woody odor from cork appears to be rare. One of the major advantages of cork has been its relative absence of extractable odors.

Yeast-Induced Spoilage

A wide variety of yeast species have been implicated in wine spoilage. Even S. cerevisiae could be so classed, if it grew where and when it was unwanted – for example, in bottles of semisweet wine. In addition, epiphytic yeasts such as Kloeckera apiculata and Metschnikowia pulcherrima can induce wine spoilage. During fermentation, these organisms can donate high contents of acetic acid, ethyl acetate, diacetyl, and o-aminoacetophenone. The latter has frequently been implicated in the generation of an ‘untypical aged’ (UTA) flavor of wines (Sponholz and Hühn, 1996). Nonetheless, it is unlikely that these yeasts could grow in bottled wine.

Spoilage is commonly detected due to the production of off-odors. However, yeast spoilage can also generate off-tastes and visual faults. Spoilage can simply result from yeast growth, inducing haze formation and/or sediment deposition. The number of cells required to generate haziness varies with the species. With Brettanomyces, a distinct haziness has been reported to develop at less than 102 cells/mL (Edelényi, 1966). In contrast, most yeast populations must reach above 105 cells/mL to begin to generate haze (Hammond, 1976).

Zygosaccharomyces bailii can generate both flocculant and granular deposits (Rankine and Pilone, 1973). It can grow in bottling equipment, contaminating and clouding thousands of bottles. White and rosé wines tend to be more susceptible to attack than red wines. This is probably explained by the suppression of Z. bailii by the tannins that characterize red wines. Z. bailii is frequently difficult to control due to its high resistance to yeast inhibitors. For example, it can grow in wine supplemented with 200 mg/liter of either sulfur dioxide, sorbic acid, or diethyl dicarbonate (Rankine and Pilone, 1973). Some strains can even grow in wines at up to 18% alcohol, although most are restricted by 12% (Kalathenos et al., 1995). Even 1 cell/10 liters may be sufficient to induce spoilage (Davenport, 1982). Along with osmophilic Kluyveromyces spp., Z. bailii can spoil sweet reserve.

These spoilage yeasts frequently produce enough acetic acid and higher alcohols to taint wine. They may also produce acetoin. By itself, acetoin does not generate a distinct off-odor. Its sensory threshold is too high. Nonetheless, its conversion to diacetyl can result in an undesirable character, often described as buttery. Z. bailii also effectively metabolizes malic acid, potentially resulting in an undesired reduction in acidity and rise in pH.

Z. bailii is rarely isolated from the grape flora of healthy fruit, but commonly occurs in association with grape sour rot (Barata et al., 2008a). The latter, a disease of complex etiology, is associated with infection of wounds by a wide range of saprophytic or weakly parasitic yeasts, fungi, and bacteria. Z. bailii is able to survive throughout the fermentation process, contaminating the finished wine.

Z. lentus (Steels et al., 1999) is a newly designated species. It has the potential of being even more significant than Z. bailii. It is osmophilic, preservative-resistant, and can grow at low temperatures.

Several yeasts form film-like surface growths on wine under aerobic conditions. These include strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. prostoserdovii), S. bayanus, and Z. fermentati. These are involved in producing the flor character of sherries and similarly matured wines. Species of Candida, Pichia, Hansenula, and Brettanomyces may occur as minor members in film growths on flor sherries, without apparent harm. Under other conditions, they are considered spoilage organisms, causing the formation of unsightly deposits.

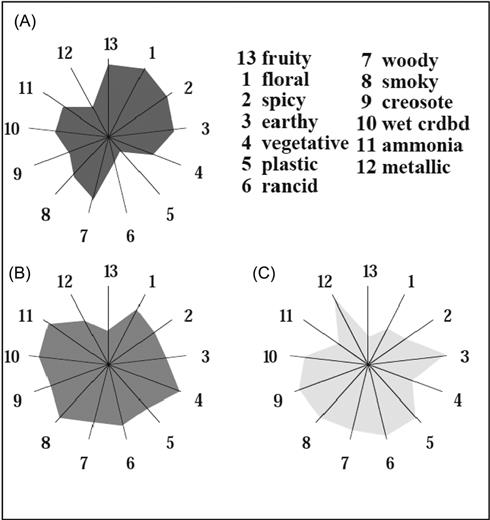

Of spoilage yeasts, Brettanomyces (imperfect state of Dekkera) is probably the most notorious (Larue et al., 1991), as well as controversial (Licker et al., 1998). Surprising to those who detect the malodorous by-products of Brettanomyces metabolism, some winemakers appear to appreciate its effects, considering that it donates part of the wine’s distinct (terroir) character. These individuals often refer to spicy, smoky, or simply complex aspects, rather than the horse sweat or manure others detect. From the view point of most microbiologists, it is clearly an egregious spoilage organism. For example, Fugelsang and Zoecklein (2003) found no strain that had a positive effect on wine quality. In a study of consumer response, there was a clear correlation between wine disappreciation and the presence of a ‘Brett’ character (Curtin et al., 2008). Interestingly, the presence of this feature appears to be suppressed by the equal presence of an oaked character, and vice versa. A ‘Brett’ aspect is often viewed to suppress the fruity and floral character of affected wines (Gerbaux and Vincent, 2001; Aznar et al., 2003) (Fig. 8.77). Botha (2010) detected suppression of berry attributes in Pinotage wines, and complex interactions (both synergism and suppression) between the various sensory aspects of ethylphenols.

Brettanomyces contamination is particularly a problem with barrel-matured red wine. Delayed racking and malolactic fermentation enhance the risks of contamination. Despite the yeast’s slow growth, insensitivity to sulfur dioxide, alcohol, and low sugar levels give it great potential to develop in the lees and spoil wine.

The potential seriousness posed by Brettanomyces is indicated by the estimation that 50% of nonstabilized French Pinot noir wines tested were contaminated with Brettanomyces by the end of malolactic fermentation. It was also detected in about 25% of bottled versions (Gerbaux et al., 2000). Thus, risk of spoilage is not limited solely to wines during in-barrel maturation. The problem appears to be most frequent in wine sealed with cork closures. Coulter (2010) suspects that sporadic spoilage in bottled wine may arise from variability in the potential for oxygen ingress among corks. Oxygen so derived could favor the metabolism of Brettanomyces (du Toit et al., 2005). Even in dry wines, there appears to be ample residual sugar to permit growth, with the production of well-above-threshold concentrations of 4-ethylphenol (Barata et al., 2008b; Coulter, 2010). The negative influence of 4-ethylphenol is estimated to begin within the range of 425–500 μg/liter (in red wines), but can be detected at lower concentrations.

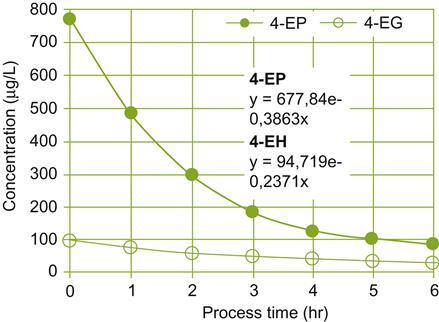

Brettanomyces spp. derive most of their infamy from their ability to synthesize several volatile phenolics, notably ethylphenols (4-ethylphenol and 4-ethylguaiacol) (Chatonnet et al., 1997; Licker et al., 1998). In trace amounts, ethylphenols can donate smoky, spicy, phenolic, or medicinal attributes, features that could be appreciated. At higher concentrations, they generate sweaty, leather, barnyardy, or manure taints. Their sensory effects depend not only on their concentration, but also the type of wine (matrix) (Romano et al., 2008). The potential to synthesize ethylphenols depends on reducing decarboxylated hydroxycinnamic acids (vinylphenols). The concentration of these odious compounds can be decreased by absorption to yeast cell walls (Pradelles et al., 2008) or reverse osmosis (Fig. 8.78).

Brettanomyces spp., such as B. intermedius and B. lambicus, may also synthesize 2-acetyltetrahydropyridines. These possess mousy odors. They, and related compounds (Grbin et al., 1996), are derived from ethyl amino acid precursors (Heresztyn, 1986). They can also be produced by several spoilage bacteria. ‘Brett’ taints have also been associated with the production of above-threshold amounts of isobutyric, isovaleric, and 2-methyl-butyric acids (Suárez et al., 2007). Licker et al. (1998) associated ‘Brett’ taints primarily with isovaleric acid, and an unknown plastic-smelling compound. Under slightly aerobic conditions, the yeast can also generate pronounced concentrations of acetic (volatile) acidity (Freer et al., 2003). Certain Brettanomyces species may also generate apple or cider odors, and liberate toxic fatty acids (octanoic and decanoic acids). The toxic fatty acids can accumulate to concentrations sufficient to retard the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, if contamination occurs in the juice before fermentation.

Brettanomyces species can survive and multiply in, and thereby contaminate, wines from transfer piping. Nonetheless, insufficiently cleaned and disinfected cooperage appears to be the principal source of contagion. Their ability to grow on cellobiose, a by-product of toasting during barrel production, means that improperly stored new barrels can also support Brettanomyces populations. They are also effectively transmitted by fruit flies.

The difficulty in controlling these yeasts primarily rests in their relative insensitivity to sulfur dioxide. This may relate to many strains being able to rapidly adhere to surfaces and form biofilms (Joseph et al., 2007). Biofilm-forming microbes are notoriously hard to control with antimicrobial agents – such agents being unable to effectively penetrate the densely coherent colonies. The yeasts can also survive and multiply on trace amounts of sugar and amino acids left in tubing or cooperage after use. Thus, control demands prompt cleaning and surface-sterilization. Chatonnet et al. (1993a) recommend that used barrels are disinfected with at least 7 g SO2/barrel, and filled barrels are maintained at 20–25 mg/liter free SO2, with periodic additions as needed. Dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) appears to show promise during wine maturation, before bottling (Renouf et al., 2008). The yeast is also susceptible to killer toxins from Pichia anomala and Kluyveromyces wickerhamii (Comitini et al., 2004). Barrel-surface contamination with Brettanomyces can also be reduced by exposure to sterilizing ultraviolet radiation. Under appropriate conditions, ultraviolet radiation may also significantly reduce microbial populations in juice and wine (Fredericks et al., 2011). An alternative treatment showing promise is the application of a low electric current treatment (LEC) to maturating wine (Lustrato et al., 2010).

Because eliminating Brettanomyces contamination, once established, has proven exceptionally difficult, it is important to avoid the initial contamination. Keeping cellar temperatures at below 12°C (after malolactic fermentation), maintaining an adequate level of free sulfur dioxide (often considered about 0.8 ppm molecular), and achieving residual sugar levels as low as possible (<1 g/liter) slow the growth of Brettanomyces in maturing wine. Other control measures are summarized by Suárez et al. (2007). Nonetheless, sterile filtration (preferably 0.3 μm membrane) (Renouf et al., 2008) and strict hygiene at all stages of bottling are the only sure means of preventing development of a ‘Brett’ character in bottled wines.

Compounding difficulties with control is the slow growth of Brettanomyces on culture media. It can take up to 2 weeks to identify its presence by traditional methods. These methods also limit identification to strains that are readily culturable, a situation not necessarily valid for all strains. Correspondingly, there has been considerable interest in developing molecular methods for rapid identification (Cocolin et al., 2004; Delaherche et al., 2004). This would permit the early application of control measures, as soon as contamination was detected. This is a problem inherent with all potential contaminant microbes. Epifluorescence microscopy is another potential option for rapidly establishing the presence of infestation. Regrettably, because of the complexity of these procedures, their application is restricted to firms or research centers specializing in such a service. In addition, as noted by Murat et al. (2006), the method of sampling is equally important. The presence of Brettanomyces is often distributed nonuniformly throughout a barrel, often largely localized in the lees.

Although uncommon, some filamentous fungi, such as Aureobasidium pullans and Exophiala jeanselmei var. heteromorpha, can grow in must and, under suitably aerobic conditions, in wine. They often metabolize tartaric acid and can seriously reduce total acidity (Poulard et al., 1983). Must or wine so affected is highly susceptible to further microbial spoilage.

Bacterial-Induced Spoilage

Other than a few yeasts of major significance, most microbial spoilage is of bacterial origin. Nonetheless, the majority of bacteria do not grow well, or at all, at the pH values typical of wine. Thus, only genera in two bacterial families are typically involved in wine spoilage – the Lactobacillaceae and Acetobacteraceae.Figure 8.79 provides a summary of the genera involved, their effects, and the pathways involved in generating these effects.

Lactic Acid Bacteria

Lactic acid bacteria have already been noted in connection with malolactic fermentation. In this regard, the activity of Oenococcus oeni is frequently desirable. However, the activity of other lactic acid bacteria is usually undesirable, and may incite serious spoilage. Such spoilage is largely restricted to table wines, but Lactobacillus hilgardii can occasionally grow in fortified wines (Couto and Hogg, 1994).

Spoilage typically occurs under warm conditions, in the presence of insufficient sulfur dioxide, and at pH values higher than 3.5. None of the problems are induced exclusively by a single species, and the frequency of spoilage strains varies considerably among species.

Tourne refers to a spoilage syndrome associated primarily with Lactobacillus brevis, although a few strains of Oenococcus oeni have been implicated. Spoilage is primarily associated with the fermentation of tartaric acid to oxaloacetic acid. Depending on the strain, oxaloacetate is subsequently metabolized, resulting in the accumulation of lactic acid, succinic acid, acetic acid, and carbon dioxide. Associated with these changes is a rise in pH and the development of a flat taste. Affected red wines also usually turn a dull red-brown color, become cloudy, and develop a viscous deposit. Some forms produce an abundance of carbon dioxide, giving affected wine an effervescent aspect. In addition to an increase in volatile acidity, other off-odors may develop. These are often characterized as sauerkrauty or mousy.

Amertume is another syndrome usually associated with the growth of a few strains of Lactobacillus brevis and L. buchneri. The strains are characterized by the ability to oxidize glycerol to 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde, and its subsequent dehydration to acrolein or reduction to 1,3-propanediol. Acrolein possesses a bitter taste (Fr. amertume). Alternative metabolic routing of glycerol may increase the concentrations of aromatic compounds, such as 2,3-butanediol and acetic acid. As a result of glycerol metabolism, its concentration may decrease by 80–90%. In addition, there is a marked accumulation of carbon dioxide and often a doubling of the volatile acidity (Siegrist et al., 1983).