Kernel-based programming originally became popular as a way to access GPUs. Since it has now been generalized across many types of accelerators, it is important to understand how our style of programming affects the mapping of code to an FPGA as well.

Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) are unfamiliar to the majority of software developers, in part because most desktop computers don’t include an FPGA alongside the typical CPU and GPU. But FPGAs are worth knowing about because they offer advantages in many applications. The same questions need to be asked as we would of other accelerators, such as “When should I use an FPGA?”, “What parts of my applications should be offloaded to FPGA?”, and “How do I write code that performs well on an FPGA?”

This chapter gives us the knowledge to start answering those questions, at least to the point where we can decide whether an FPGA is interesting for our applications, and to know which constructs are commonly used to achieve performance. This chapter is the launching point from which we can then read vendor documentation to fill in details for specific products and toolchains. We begin with an overview of how programs can map to spatial architectures such as FPGAs, followed by discussion of some properties that make FPGAs a good choice as an accelerator, and we finish by introducing the programming constructs used to achieve performance.

The “How to Think About FPGAs” section in this chapter is applicable to thinking about any FPGA. SYCL allows vendors to specify devices beyond CPUs and GPUs, but does not specifically say how to support an FPGA. The specific vendor support for FPGAs is currently unique to DPC++, namely, FPGA selectors and pipes. FPGA selectors and pipes are the only DPC++ extensions used in this chapter. It is hoped that vendors will converge on similar or compatible means of supporting FPGAs, and this is encouraged by DPC++ as an open source project.

Performance Caveats

As with any processor or accelerator, FPGA devices differ from vendor to vendor or even from product generation to product generation; therefore, best practices for one device may not be best practices for a different device. The advice in this chapter is likely to benefit many FPGA devices, both now and in the future, however…

…to achieve optimal performance for a particular FPGA, always consult the vendor’s documentation!

How to Think About FPGAs

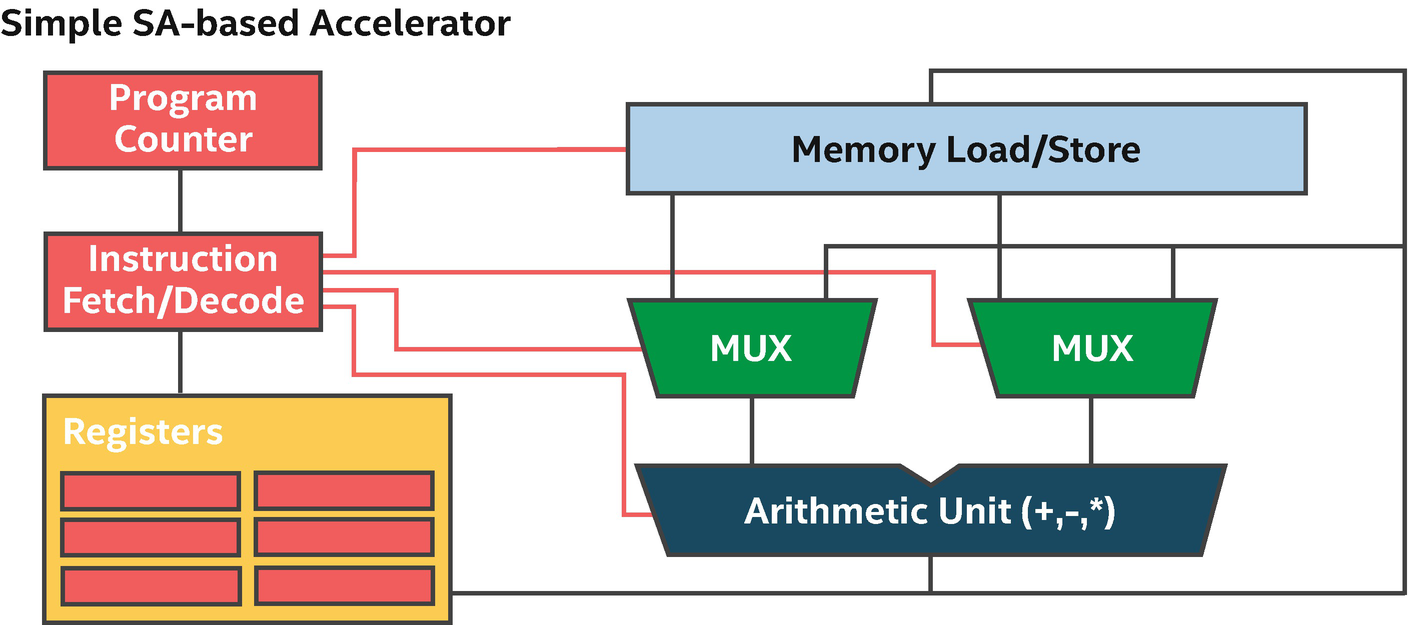

FPGAs are commonly classified as a spatial architecture. They benefit from very different coding styles and forms of parallelism than devices that use an Instruction Set Architecture (ISA), including CPUs and GPUs, which are more familiar to most people. To get started forming an understanding of FPGAs, we’ll briefly cover some ideas from ISA-based accelerators, so that we can highlight key differences.

For our purposes, an ISA -based accelerator is one where the device can execute many different instructions, one or a few at a time. The instructions are usually relatively primitive such as “load from memory at address A” or “add the following numbers.” A chain of operations is strung together to form a program, and the processor conceptually executes one instruction after the other.

Simple ISA-based (temporal) processing: Reuses hardware (regions) over time

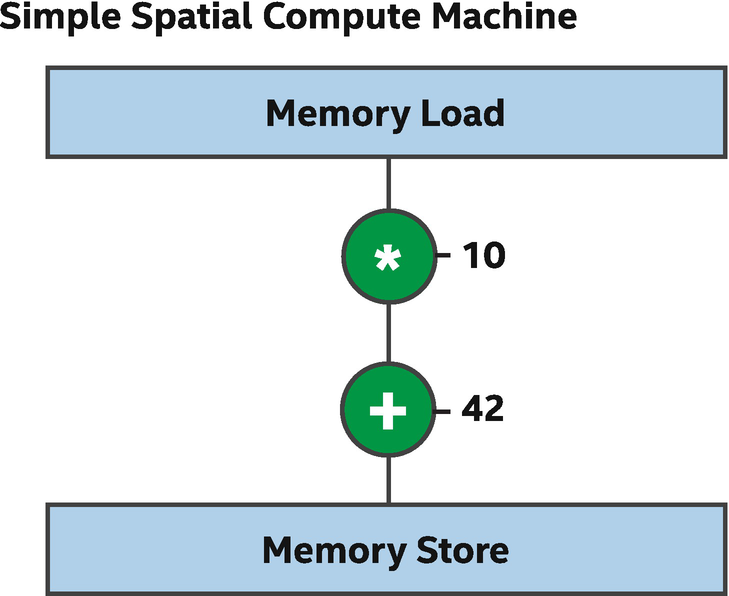

Spatial processing: Each operation uses a different region of the device

This description of a spatial implementation of a program is overly simplistic, but it captures the idea that in spatial architectures, different parts of the program execute on different parts of the device, as opposed to being issued over time to a shared set of more general-purpose hardware.

With different regions of an FPGA programmed to perform distinct operations, some of the hardware typically associated with ISA-based accelerators is unnecessary. For example, Figure 17-2 shows that we no longer need an instruction fetch or decode unit, program counter, or register file. Instead of storing data for future instructions in a register file, spatial architectures connect the output of one instruction to the input of the next, which is why spatial architectures are often called data flow architectures.

The benefit: If a program uses most of the area on the FPGA and there is sufficient work to keep all of the hardware busy every clock cycle, then executing a program on the device can be incredibly efficient because of the extreme parallelism. More general architectures may have significant unused hardware per clock cycle, whereas with an FPGA, the use of area can be perfectly tailored to a specific application without waste. This customization can allow applications to run faster through massive parallelism, usually with compelling energy efficiency.

The downside: Large programs may have to be tuned and restructured to fit on a device. Resource sharing features of compilers can help to address this, but usually with some degradation in performance that reduces the benefit of using an FPGA. ISA-based accelerators are very efficient resource sharing implementations—FPGAs prove most valuable for compute primarily when an application can be architected to utilize most of the available area.

Taken to the extreme, resource sharing solutions on an FPGA lead to an architecture that looks like an ISA-based accelerator, but that is built in reconfigurable logic instead being optimized in fixed silicon. The reconfigurable logic leads to overhead relative to a fixed silicon design—therefore, FPGAs are not typically chosen as ways to implement ISAs. FPGAs are of prime benefit when an application is able to utilize the resources to implement efficient data flow algorithms, which we cover in the coming sections.

Pipeline Parallelism

Another question that often arises from Figure 17-2 is how the spatial implementation of a program relates to a clock frequency and how quickly a program will execute from start to finish. In the example shown, it’s easy to believe that data could be loaded from memory, have multiplication and addition operations performed, and have the result stored back into memory, quite quickly. As the program becomes larger, potentially with tens of thousands of operations across the FPGA device, it becomes apparent that for all of the instructions to operate one after the other (operations often depend on results produced by previous operations), it might take significant time given the processing delays introduced by each operation.

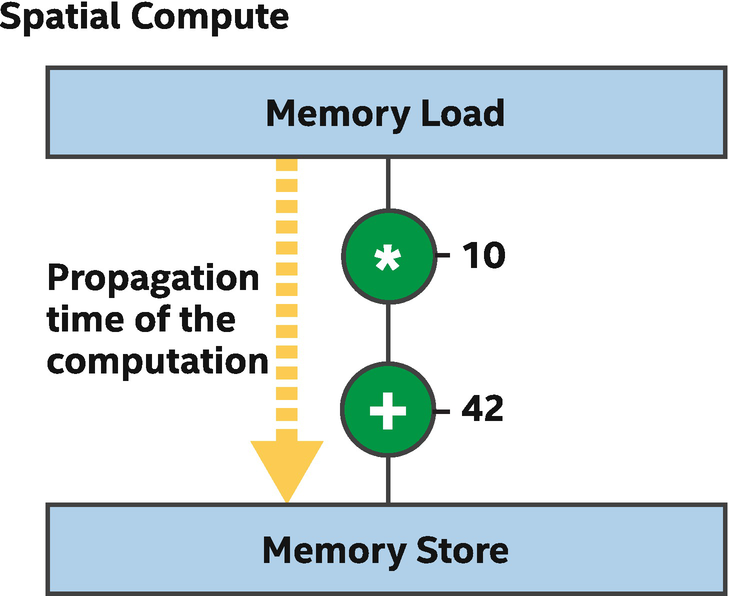

Propagation time of a naïve spatial compute implementation

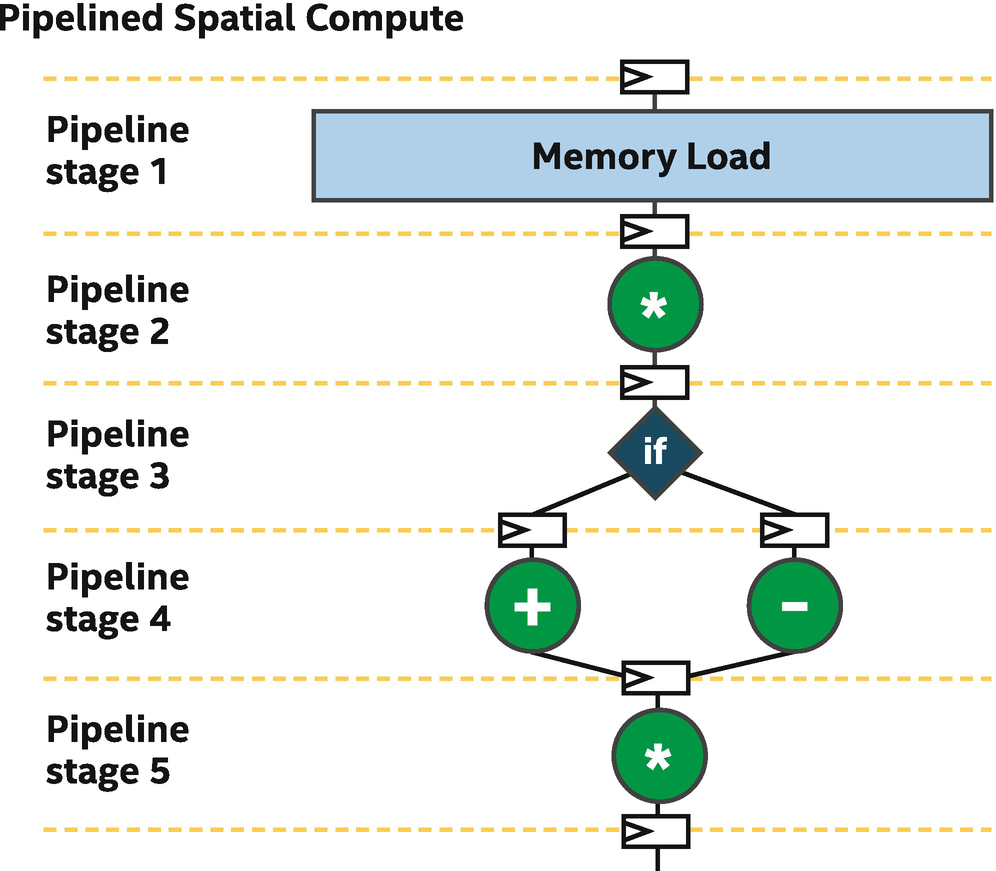

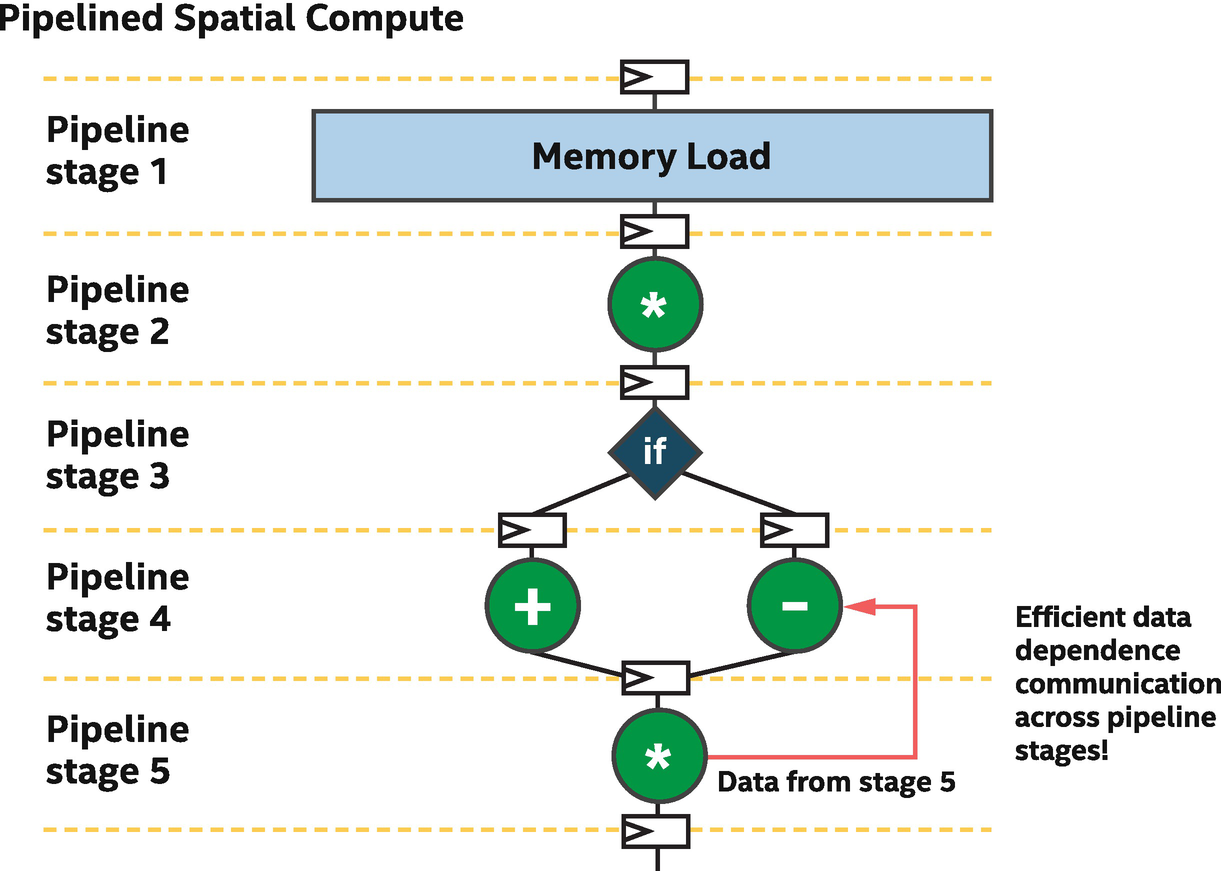

A spatial implementation as shown in Figure 17-3 is quite inefficient, because most of the hardware is only doing useful work a small percentage of the time. Most of the time, an operation such as the multiply is either waiting for new data from the load or holding its output so that operations later in the chain can use its result. Most spatial compilers and implementations address this inefficiency by pipelining, which means that execution of a single program is spread across many clock cycles. This is achieved by inserting registers (a data storage primitive in the hardware) between some operations, where each register holds a binary value for the duration of a clock cycle. By holding the result of an operation’s output so that the next operation in the chain can see and operate on that held value, the previous operation is free to work on a different computation without impacting the input to following operations.

Pipelining of a computation: Stages execute in parallel

When a spatial implementation is pipelined, it becomes extremely efficient in the same way as a factory assembly line. Each pipeline stage performs only a small amount of the overall work, but it does so quickly and then begins to work on the next unit of work immediately afterward. It takes many clock cycles for a single computation to be processed by the pipeline, from start to finish, but the pipeline can compute many different instances of the computation on different data simultaneously.

When enough work starts executing in the pipeline, over enough consecutive clock cycles, then every single pipeline stage and therefore operation in the program can perform useful work during every clock cycle, meaning that the entire spatial device performs work simultaneously. This is one of the powers of spatial architectures—the entire device can execute work in parallel, all of the time. We call this pipeline parallelism.

Pipeline parallelism is the primary form of parallelism exploited on FPGAs to achieve performance.

In the Intel implementation of DPC++ for FPGAs, and in other high-level programming solutions for FPGAs, the pipelining of an algorithm is performed automatically by the compiler. It is useful to roughly understand the implementation on spatial architectures, as described in this section, because then it becomes easier to structure applications to take advantage of the pipeline parallelism. It should be made clear that pipeline register insertion and balancing is performed by the compiler and not manually by developers.

Real programs and algorithms often have control flow (e.g., if/else structures) that leaves some parts of the program inactive a certain percentage of the clock cycles. FPGA compilers typically combine hardware from both sides of a branch, where possible, to minimize wasted spatial area and to maximize compute efficiency during control flow divergence. This makes control flow divergence much less expensive and less of a development concern than on other, especially vectorized architectures.

Kernels Consume Chip “Area”

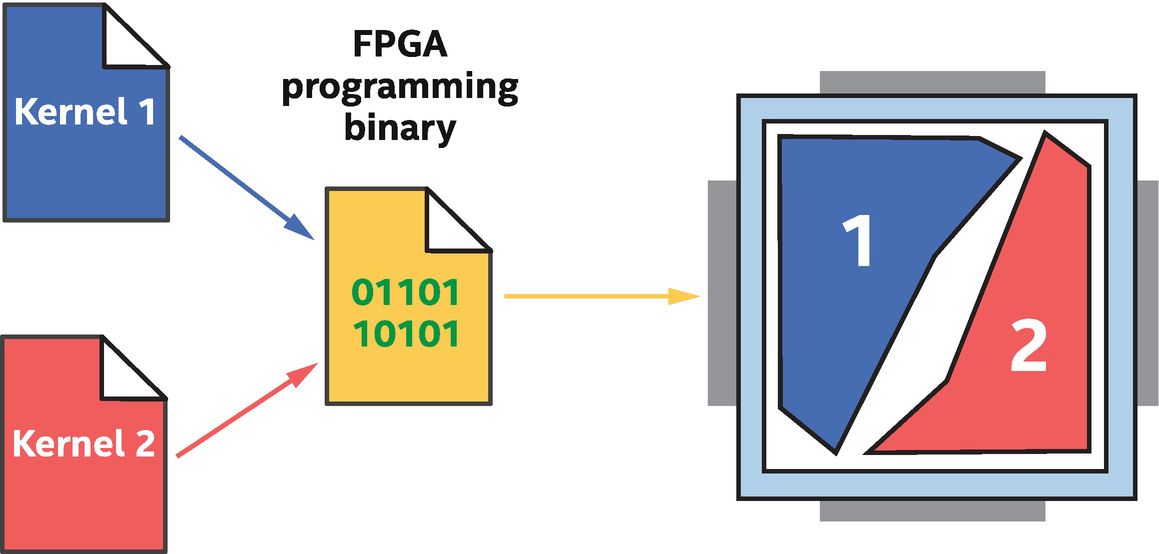

Multiple kernels in the same FPGA binary: Kernels can run concurrently

Since a kernel uses its own area on the device, different kernels can execute concurrently. If one kernel is waiting for something such as a memory access, other kernels on the FPGA can continue executing because they are independent pipelines elsewhere on the chip. This idea, formally described as independent forward progress between kernels, is a critical property of FPGA spatial compute.

When to Use an FPGA

Like any accelerator architecture, predicting when an FPGA is the right choice of accelerator vs. an alternative often comes down to knowledge of the architecture, the application characteristics, and the system bottlenecks. This section describes some of the characteristics of an application to consider.

Lots and Lots of Work

Like most modern compute accelerators, achieving good performance requires a large amount of work to be performed. If computing a single result from a single element of data, then it may not be useful to leverage an accelerator at all (of any kind). This is no different with FPGAs. Knowing that FPGA compilers leverage pipeline parallelism makes this more apparent. A pipelined implementation of an algorithm has many stages, often thousands or more, each of which should have different work within it in any clock cycle. If there isn’t enough work to occupy most of the pipeline stages most of the time, then efficiency will be low. We’ll call the average utilization of pipeline stages over time occupancy of the pipeline. This is different from the definition of occupancy used when optimizing other architectures such as GPUs!

There are multiple ways to generate work on an FPGA to fill the pipeline stages, which we’ll cover in coming sections.

Custom Operations or Operation Widths

FPGAs were originally designed to perform efficient integer and bitwise operations and to act as glue logic that could adapt interfaces of other chips to work with each other. Although FPGAs have evolved into computational powerhouses instead of just glue logic solutions, they are still very efficient at bitwise operations, integer math operations on custom data widths or types, and operations on arbitrary bit fields in packet headers.

The fine-grained architecture of an FPGA, described at the end of this chapter, means that novel and arbitrary data types can be efficiently implemented. For example, if we need a 33-bit integer multiplier or a 129-bit adder, FPGAs can provide these custom operations with great efficiency. Because of this flexibility, FPGAs are commonly employed in rapidly evolving domains, such as recently in machine learning, where the data widths and operations have been changing faster than can be built into ASICs.

Scalar Data Flow

An important aspect of FPGA spatial pipelines, apparent from Figure 17-4, is that the intermediate data between operations not only stays on-chip (is not stored to external memory), but that intermediate data between each pipeline stage has dedicated storage registers. FPGA parallelism comes from pipelining of computation such that many operations are being executed concurrently, each at a different stage of the pipeline. This is different from vector architectures where multiple computations are executed as lanes of a shared vector instruction.

The scalar nature of the parallelism in a spatial pipeline is important for many applications, because it still applies even with tight data dependences across the units of work. These data dependences can be handled without loss of performance, as we will discuss later in this chapter when talking about loop-carried dependences. The result is that spatial pipelines, and therefore FPGAs, are compelling for algorithms where data dependences across units of work (such as work-items) can’t be broken and fine-grained communication must occur. Many optimization techniques for other accelerators focus on breaking these dependences though various techniques or managing communication at controlled scales through features such as sub-groups. FPGAs can instead perform well with communication from tight dependences and should be considered for classes of algorithms where such patterns exist.

A common misconception on data flow architectures is that loops with either fixed or dynamic iteration counts lead to poor data flow performance, because they aren’t simple feed-forward pipelines. At least with the Intel DPC++ and FPGA toolchains, this is not true. Loop iterations can instead be a good way to produce high occupancy within the pipeline, and the compilers are built around the concept of allowing multiple loop iterations to execute in an overlapped way. Loops provide an easy mechanism to keep the pipeline busy with work!

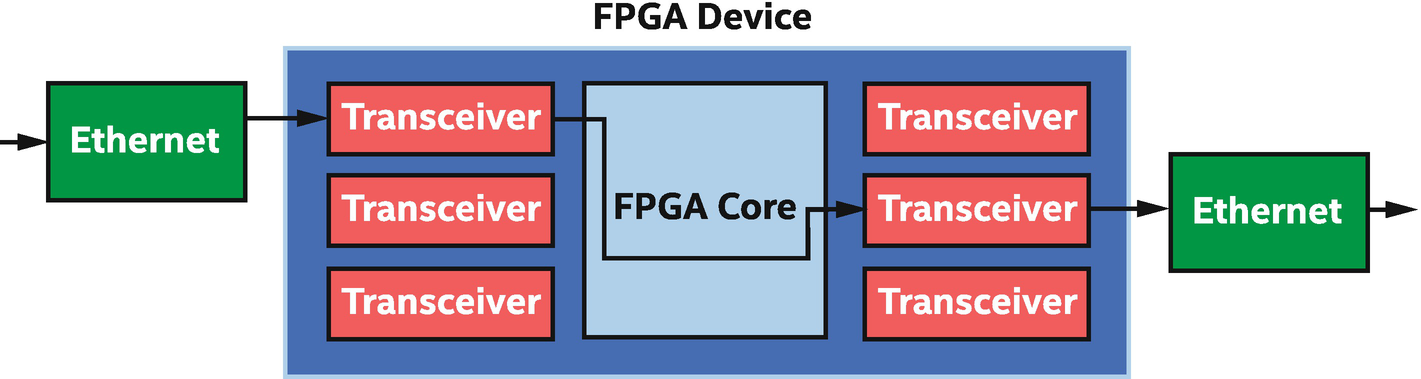

Low Latency and Rich Connectivity

Low-latency I/O streaming: FPGA connects network data and computation tightly

The opportunities are almost limitless when considering direct input/output through FPGA transceivers, but the options do come down to what is available on the circuit board that forms an accelerator. Because of the dependence on a specific accelerator card and variety of such uses, aside from describing the pipe language constructs in a coming section, this chapter doesn’t dive into these applications. We should instead read the vendor documentation associated with a specific accelerator card or search for an accelerator card that matches our specific interface needs.

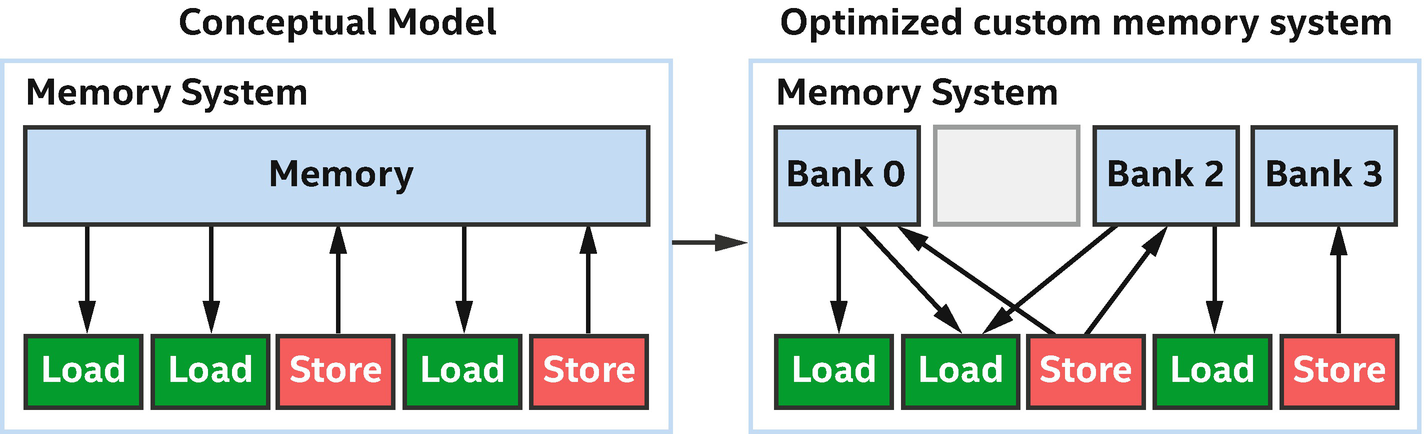

Customized Memory Systems

FPGA memory systems are customized by the compiler for our specific code

Other architectures such as GPUs have fixed memory structures that are easy to reason about by experienced developers, but that can also be hard to optimize around in many cases. Many optimizations on other accelerators are focused around memory pattern modification to avoid bank conflicts, for example. If we have algorithms that would benefit from a custom memory structure, such as a different number of access ports per bank or an unusual number of banks, then FPGAs can offer immediate advantages. Conceptually, the difference is between writing code to use a fixed memory system efficiently (most other accelerators) and having the memory system custom designed by the compiler to be efficient with our specific code (FPGA).

Running on an FPGA

- 1.

Compiling the source to a binary which can be run on our hardware of interest

- 2.

Selecting the correct accelerator that we are interested in at runtime

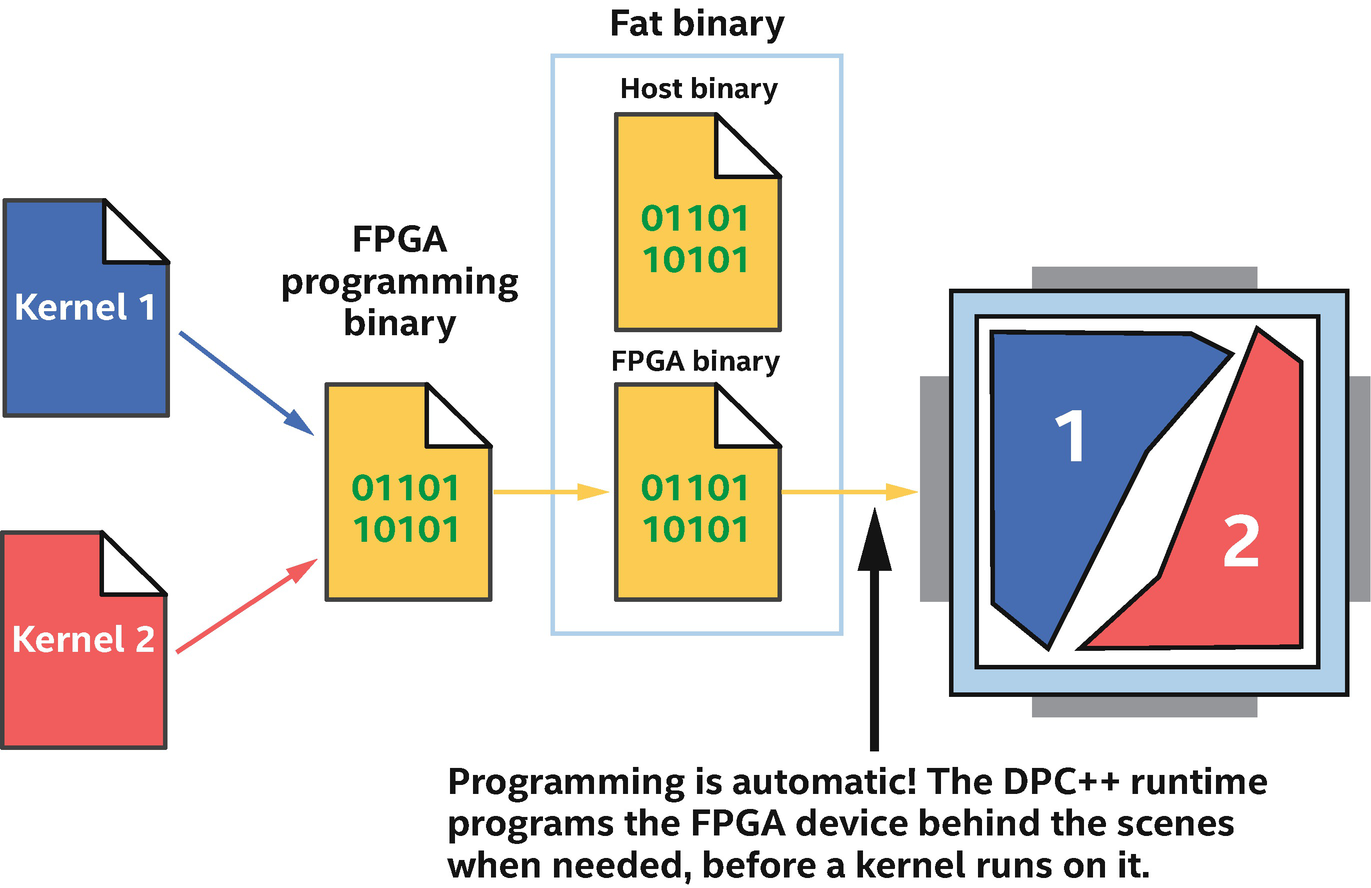

FPGA programmed automatically at runtime

FPGA programming binaries are embedded within the compiled DPC++ executable that we run on the host. The FPGA is automatically configured behind the scenes for us.

When we run a host program and submit the first kernel for execution on an FPGA, there might be a slight delay before the kernel begins executing, while the FPGA is programmed. Resubmitting kernels for additional executions won’t see the same delay because the kernel is already programmed to the device and ready to run.

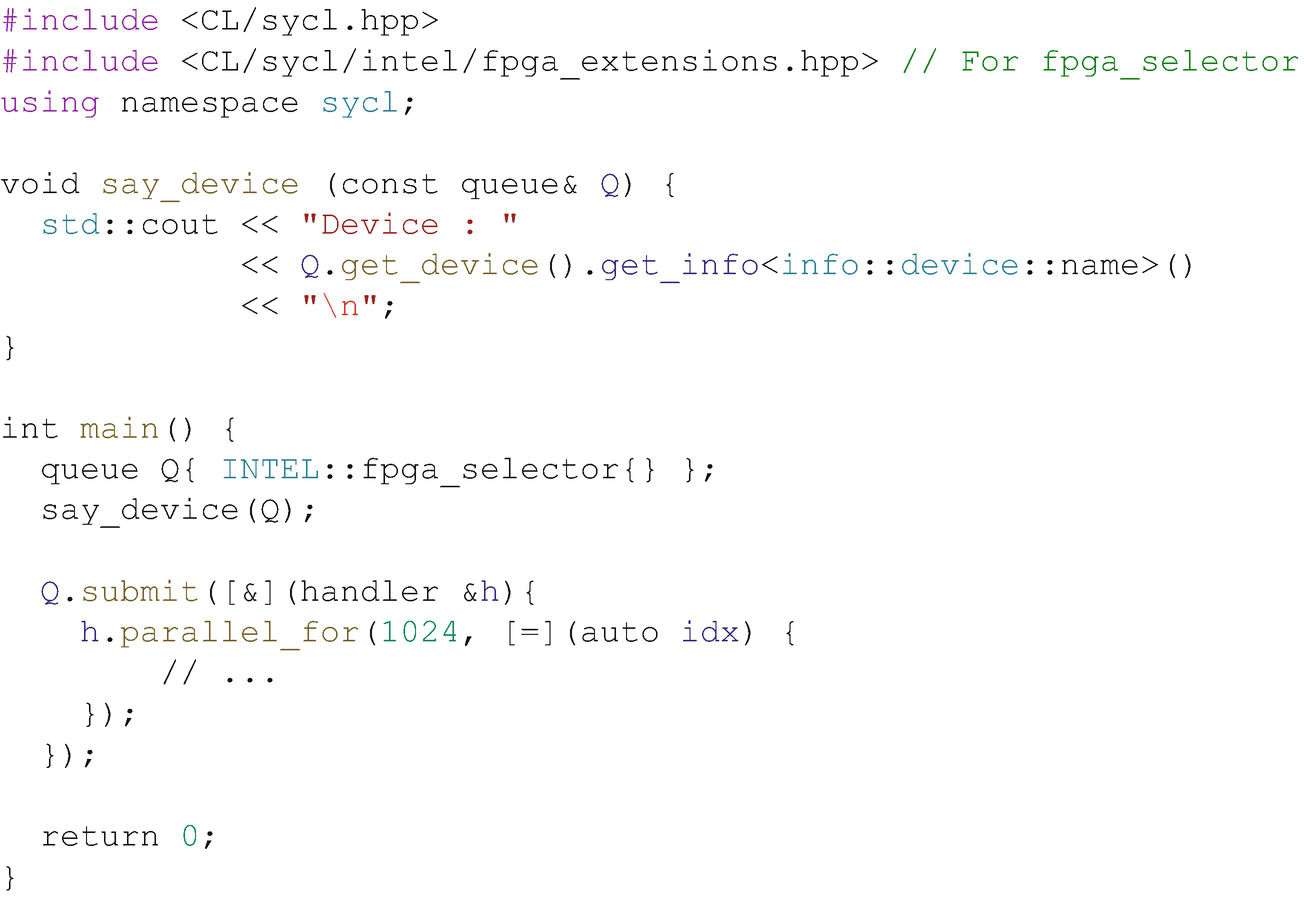

Choosing an FPGA device at runtime using the fpga_selector

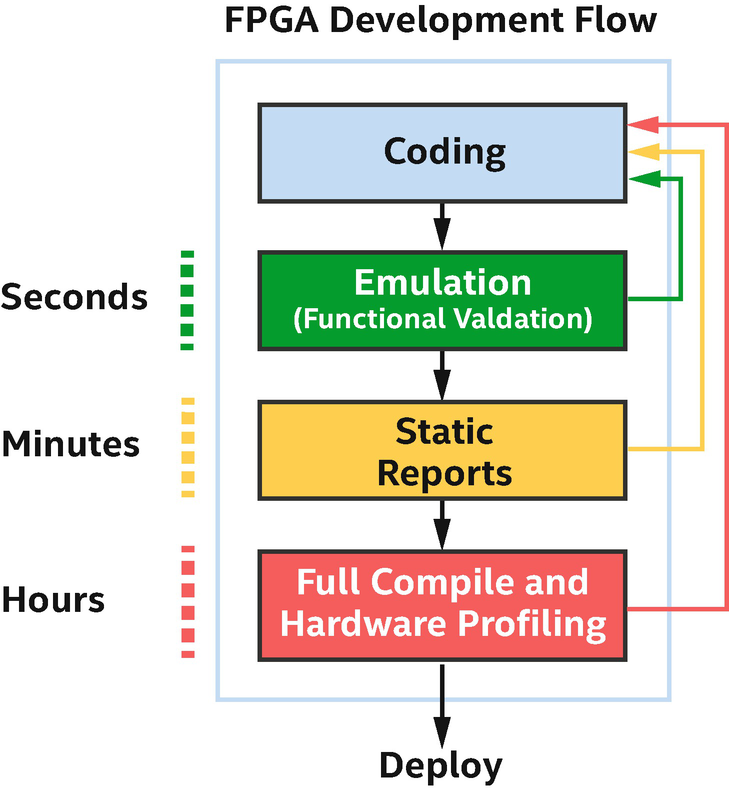

Compile Times

Rumors abound that compiling designs for an FPGA can take a long time, much longer than compiling for ISA-based accelerators. The rumors are true! The end of this chapter overviews the fine-grained architectural elements of an FPGA that lead to both the advantages of an FPGA and the computationally intensive compilation (place-and-route optimizations) that can take hours in some cases.

Most verification and optimization occurs prior to lengthy hardware compilation

Emulation and static reports from the compiler are the cornerstones of FPGA code development in DPC++. The emulator acts as if it was an FPGA, including supporting relevant extensions and emulating the execution model, but runs on the host processor. Compilation time is therefore the same as we would expect from compilation to a CPU device, although we won’t see the performance boost that we would from execution on actual FPGA hardware. The emulator is great for establishing and testing functional correctness in an application.

Static reports, like emulation, are generated quickly by the toolchain. They report on the FPGA structures created by the compiler and on bottlenecks identified by the compiler. Both of these can be used to predict whether our design will achieve good performance when run on FPGA hardware and are used to optimize our code. Please read the vendor’s documentation for information on the reports, which are often improved from release to release of a toolchain (see documentation for the latest and greatest features!). Extensive documentation is provided by vendors on how to interpret and optimize based on the reports. This information would be the topic of another book, so we can’t dive into details in this single chapter.

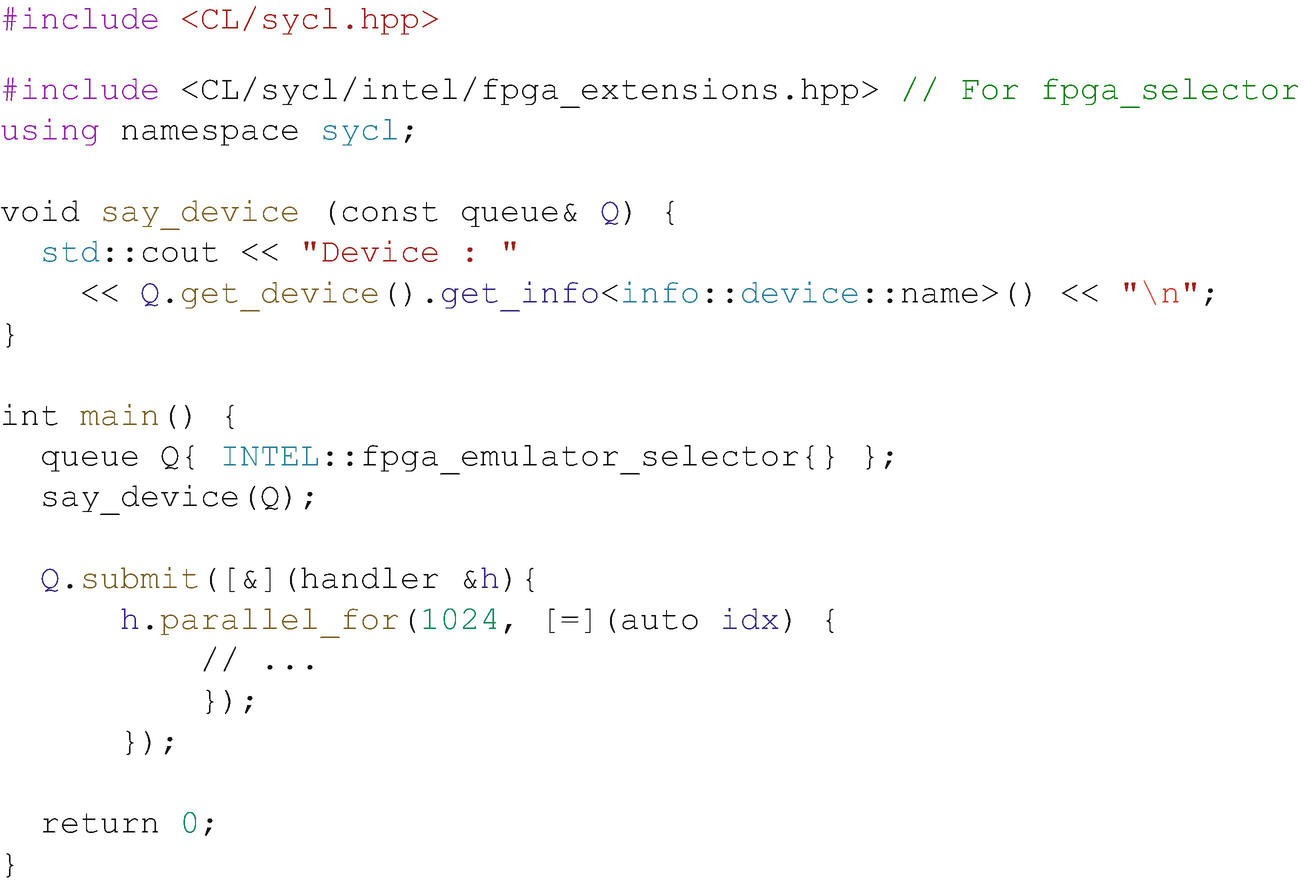

The FPGA Emulator

Using fpga_emulator_selector for rapid development and debugging

If we are switching between hardware and the emulator frequently, it can make sense to use a macro within our program to flip between device selectors from the command line. Check the vendor’s documentation and online FPGA DPC++ code examples for examples of this, if needed.

FPGA Hardware Compilation Occurs “Ahead-of-Time”

- 1.

Compilation takes a length of time that we don’t normally want to incur when running an application.

- 2.

DPC++ programs may be executed on systems that don’t have a capable host processor. The compilation process to an FPGA binary benefits from a fast processor with a good amount of attached memory. Ahead-of-time compilation lets us easily choose where the compile occurs, rather than having it run on systems where the program is deployed.

Conventional FPGA design (not using a high-level language) can be very complicated. There are many steps beyond just writing our kernel, such as building and configuring the interfaces that communicate with off-chip memories and closing timing by inserting registers needed to make the compiled design run fast enough to communicate with certain peripherals. DPC++ solves all of this for us, so that we don’t need to know anything about the details of conventional FPGA design to achieve working applications! The tooling treats our kernels as code to optimize and make efficient on the device and then automatically handles all of the details of talking to off-chip peripherals, closing timing, and setting up drivers for us.

Achieving peak performance on an FPGA still requires detailed knowledge of the architecture, just like any other accelerator, but the steps to move from code to a working design are much simpler and more productive with DPC++ than in traditional FPGA flows.

Writing Kernels for FPGAs

Once we have decided to use an FPGA for our application or even just decided to try one out, having an idea of how to write code to see good performance is important. This section describes topics that highlight important concepts and covers a few topics that often cause confusion, to make getting started faster.

Exposing Parallelism

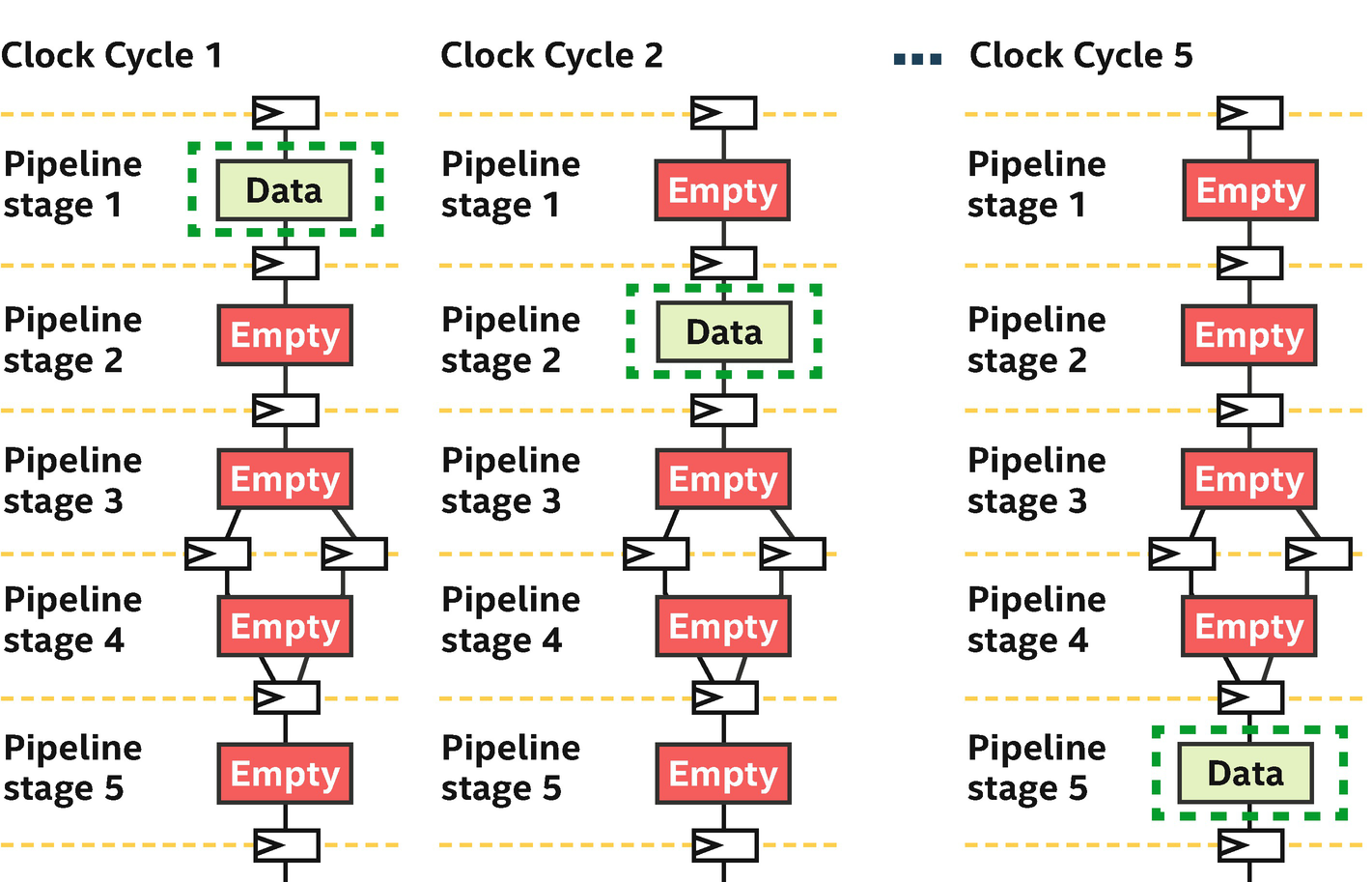

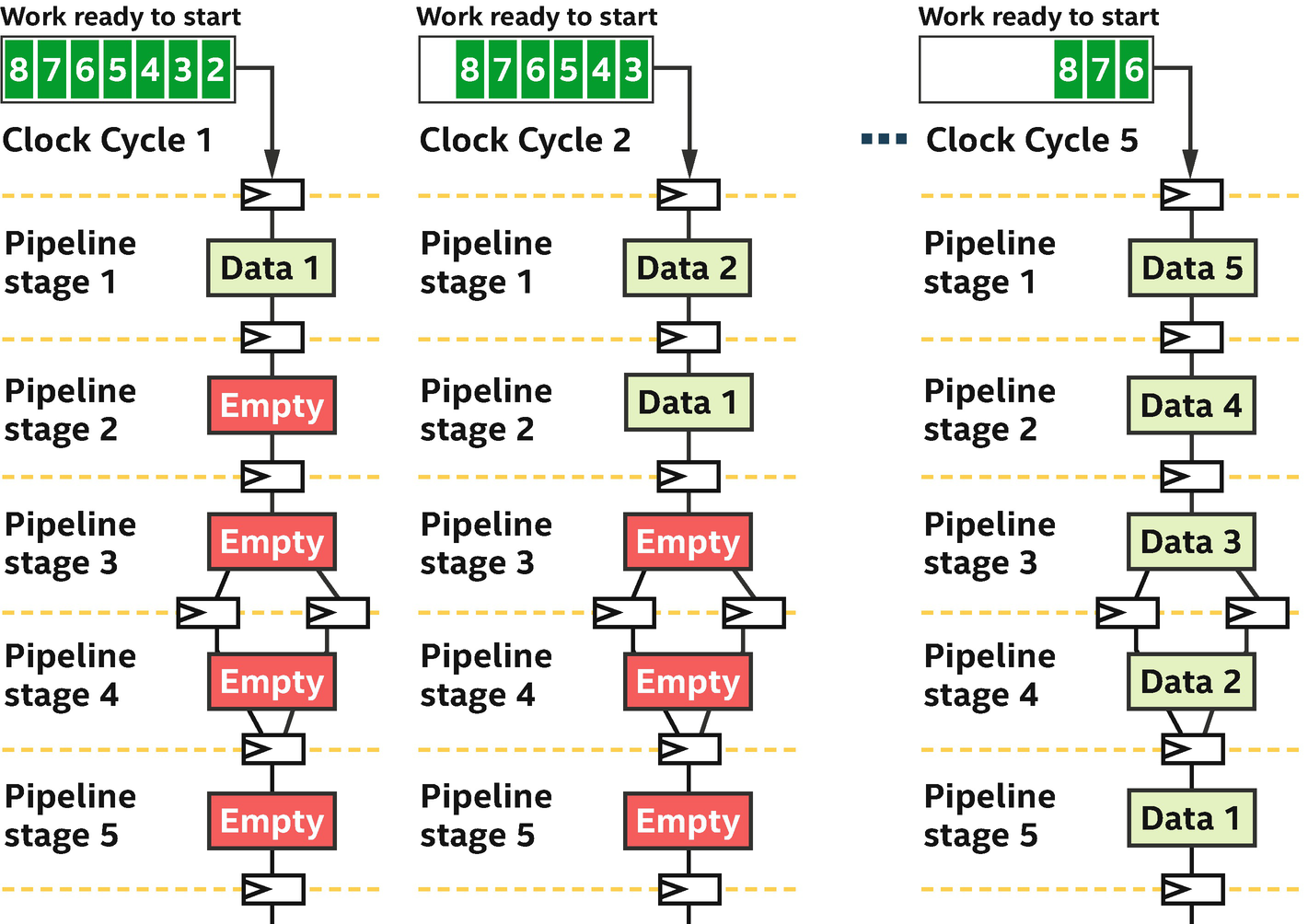

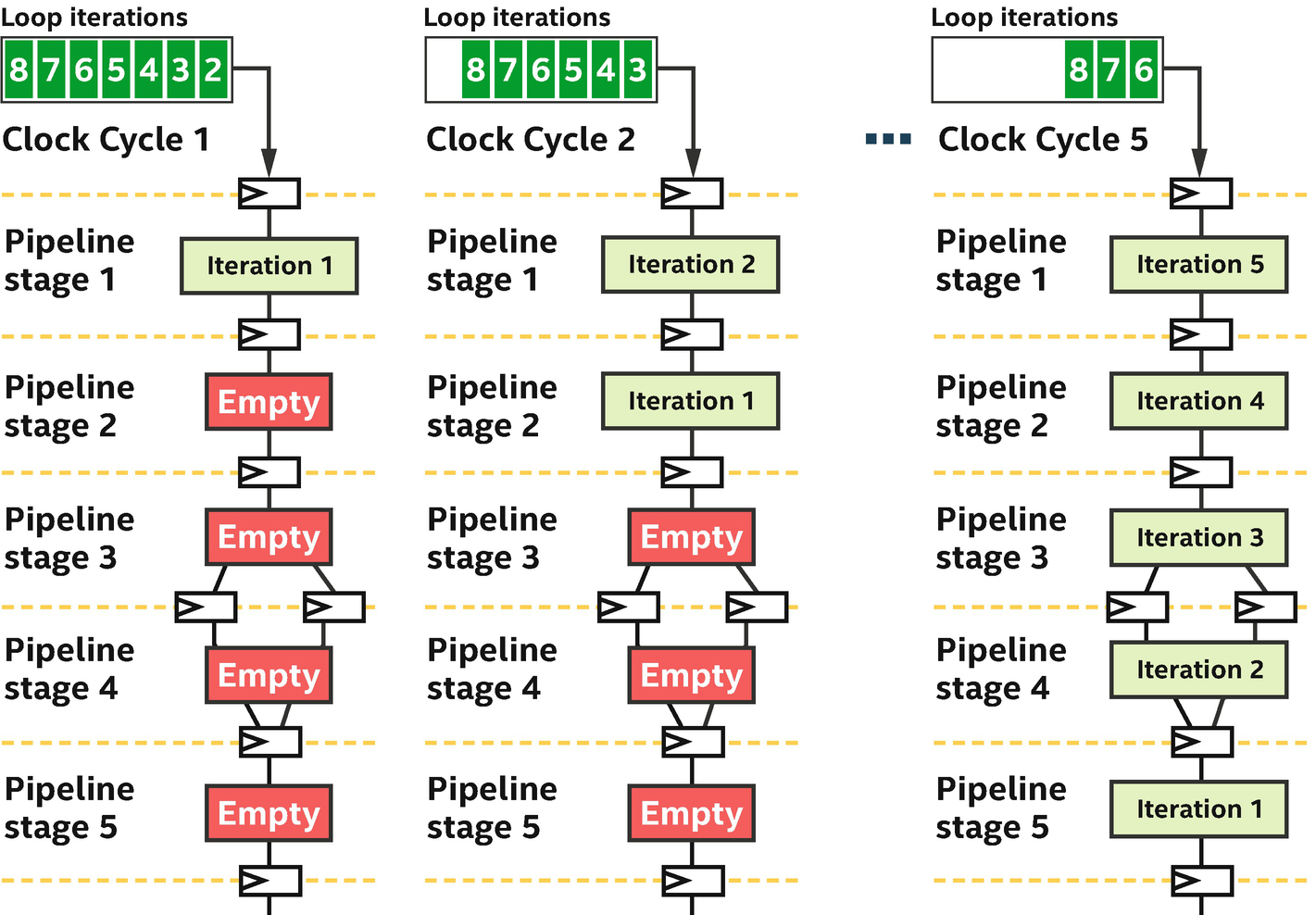

Simple pipeline with five stages: Six clock cycles to process an element of data

In this pipeline, there are five stages. Data moves from one stage to the next once per clock cycle, so in this very simple example, it takes six clock cycles from when data enters into stage 1 until it exits from stage 5.

Pipeline stages are mostly unused if processing only a single element of work

Efficient utilization comes when each pipeline stage is kept busy

- 1.

ND-range kernels

- 2.

Loops

Choosing between these options impacts how kernels that run on an FPGA should be fundamentally architected. In some cases, algorithms lend themselves well to one style or the other, and in other cases programmer preference and experience inform which method should be chosen.

Keeping the Pipeline Busy Using ND-Ranges

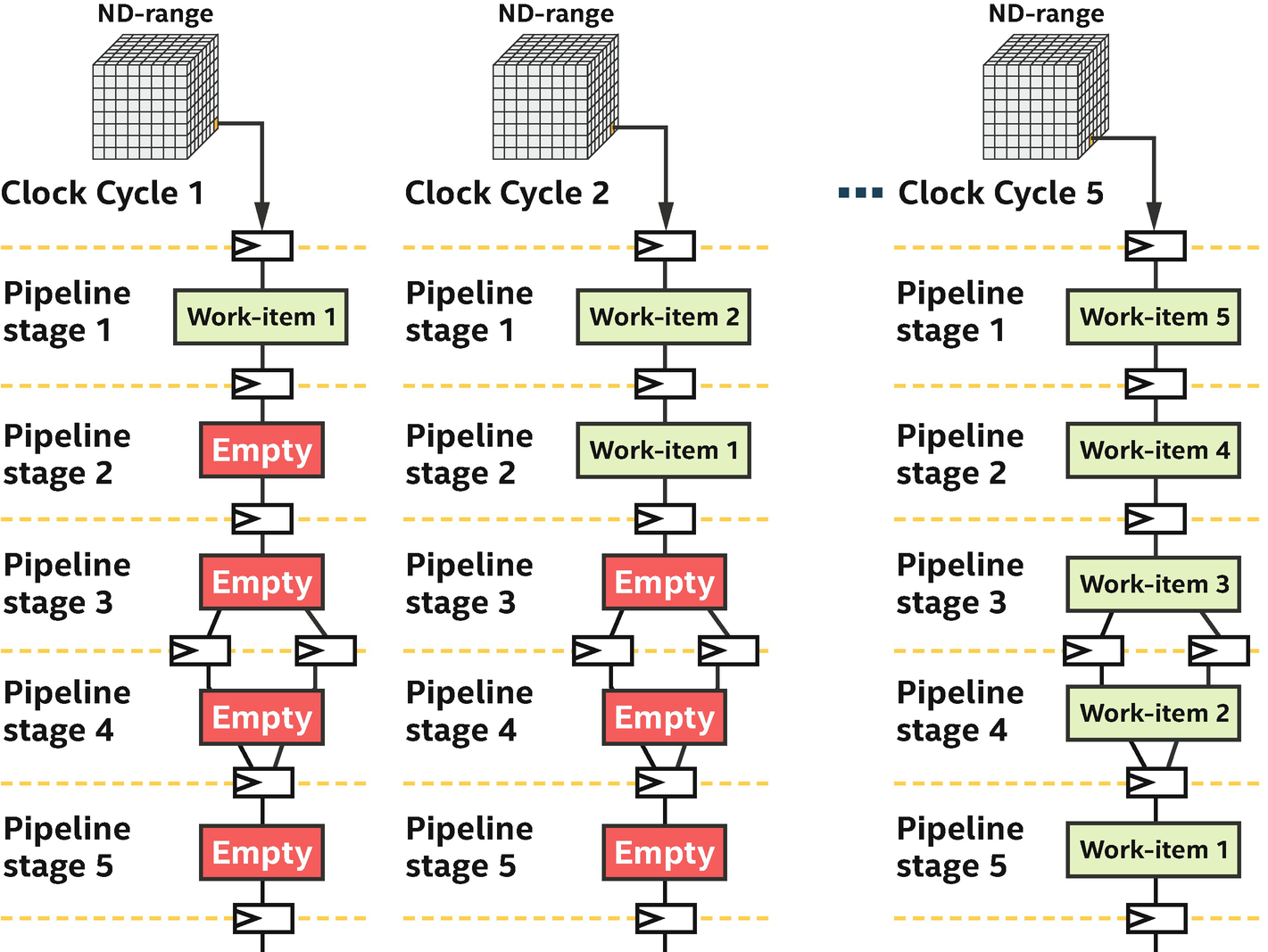

ND-range execution model: A hierarchical grouping of work-items

ND-range feeding a spatial pipeline

When should we create an ND-range kernel on an FPGA using work-items to keep the pipeline occupied? It’s simple. Whenever we can structure our algorithm or application as independent work-items that don’t need to communicate often (or ideally at all), we should use ND-range! If work-items do need to communicate often or if we don’t naturally think in terms of ND-ranges, then loops (described in the next section) provide an efficient way to express our algorithm as well.

If we can structure our algorithm so that work-items don’t need to communicate much (or at all), then ND-range is a great way to generate work to keep the spatial pipeline full!

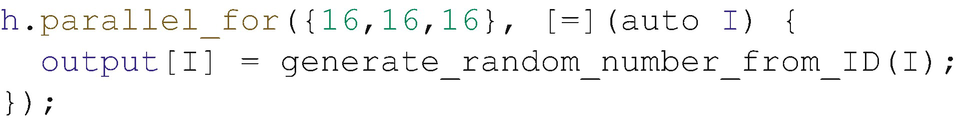

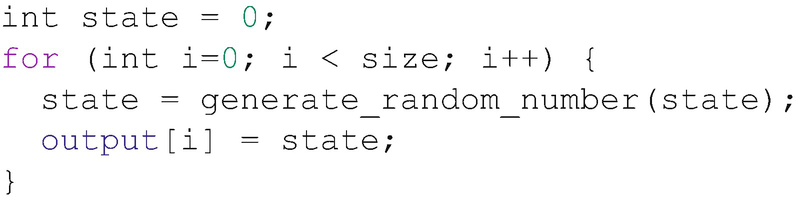

A good example of a kernel that is efficient with an ND-range feeding the pipeline is a random number generator, where creation of numbers in the sequence is independent of the previous numbers generated.

Multiple work-item (16 × 16 × 16) invocation of a random number generator

The example shows a parallel_for invocation that uses a range, with only a global size specified. We can alternately use the parallel_for invocation style that takes an nd_range, where both the global work size and local work-group sizes are specified. FPGAs can very efficiently implement work-group local memory from on-chip resources, so feel free to use work-groups whenever they make sense, either because we want work-group local memory or because having work-group IDs available simplifies our code.

The example in Figure 17-17 assumes that generate_random_number_from_ID(I) is a random number generator which has been written to be safe and correct when invoked in a parallel way. For example, if different work-items in the parallel_for range execute the function, we expect different sequences to be created by each work-item, with each sequence adhering to whatever distribution is expected from the generator. Parallel random number generators are themselves a complex topic, so it is a good idea to use libraries or to learn about the topic through techniques such as block skip-ahead algorithms.

Pipelines Do Not Mind Data Dependences!

One of the challenges when programming vector architectures (e.g., GPUs) where some work-items execute together as lanes of vector instructions is structuring an algorithm to be efficient without extensive communication between work-items. Some algorithms and applications lend themselves well to vector hardware, and some don’t. A common cause of a poor mapping is an algorithmic need for extensive sharing of data, due to data dependences with other computations that are in some sense neighbors. Sub-groups address some of this challenge on vector architectures by providing efficient communication between work-items in the same sub-group, as described in Chapter 14.

FPGAs play an important role for algorithms that can’t be decomposed into independent work. FPGA spatial pipelines are not vectorized across work-items, but instead execute consecutive work-items across pipeline stages. This implementation of the parallelism means that fine-grained communication between work-items (even those in different work-groups) can be implemented easily and efficiently within the spatial pipeline!

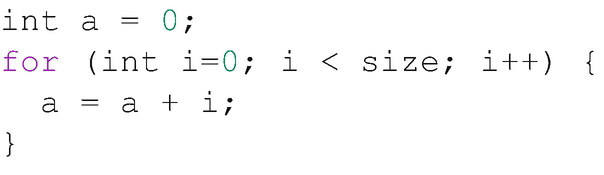

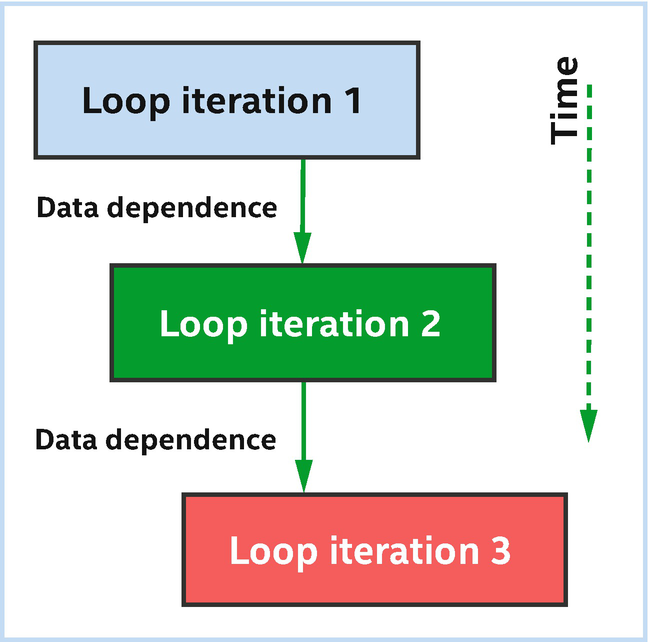

Loop-carried data dependence (state)

Backward communication enables efficient data dependence communication

- 1.

Loops

- 2.

Intra-kernel pipes with ND-range kernels

The second option is based on pipes that we describe later in this chapter, but it isn’t nearly as common as loops so we mention it for completeness, but don’t detail it here. Vendor documentation provides more details on the pipe approach, but it’s easier to stick to loops which are described next unless there is a reason to do otherwise.

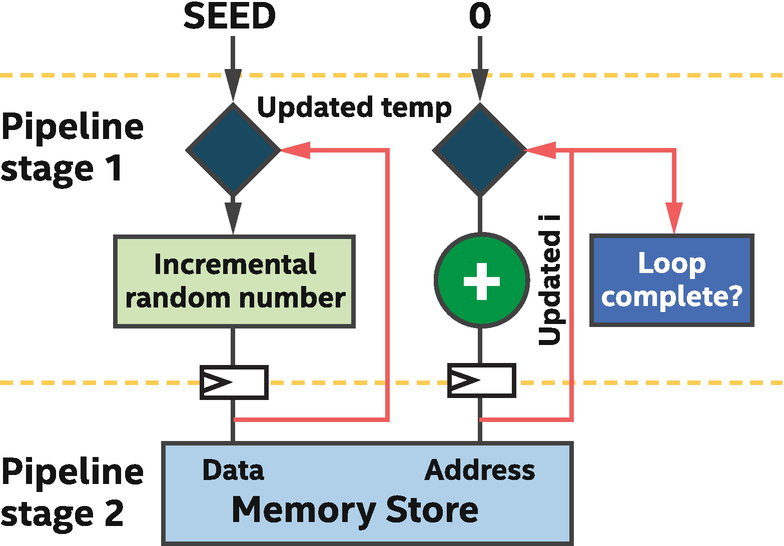

Spatial Pipeline Implementation of a Loop

Loop with two loop-carried dependences (i.e., i and a)

Pipelines stages fed by successive iterations of a loop

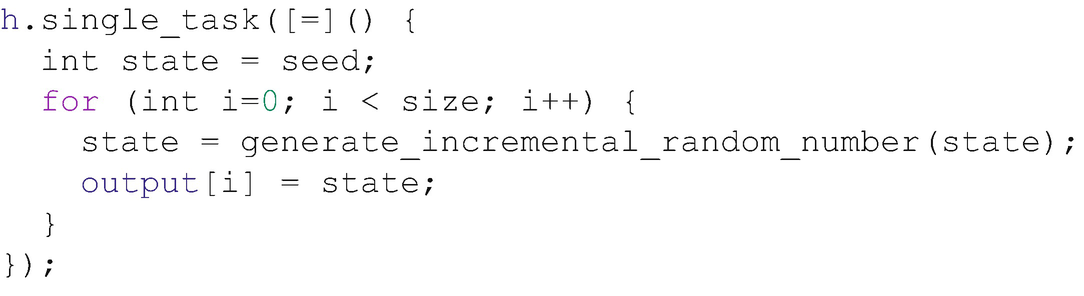

Random number generator that depends on previous value generated

The example uses single_task instead of parallel_for because the repeated work is expressed by a loop within the single task, so there isn’t a reason to also include multiple work-items in this code (via parallel_for). The loop inside the single_task makes it much easier to express (programming convenience) that the previously computed value of temp is passed to each invocation of the random number generation function.

In cases such as Figure 17-22, the FPGA can implement the loop efficiently. It can maintain a fully occupied pipeline in many cases or can at least tell us through reports what to change to increase occupancy. With this in mind, it becomes clear that this same algorithm would be much more difficult to describe if loop iterations were replaced with work-items, where the value generated by one work-item would need to be communicated to another work-item to be used in the incremental computation. The code complexity would rapidly increase, particularly if the work couldn’t be batched so that each work-item was actually computing its own independent random number sequence.

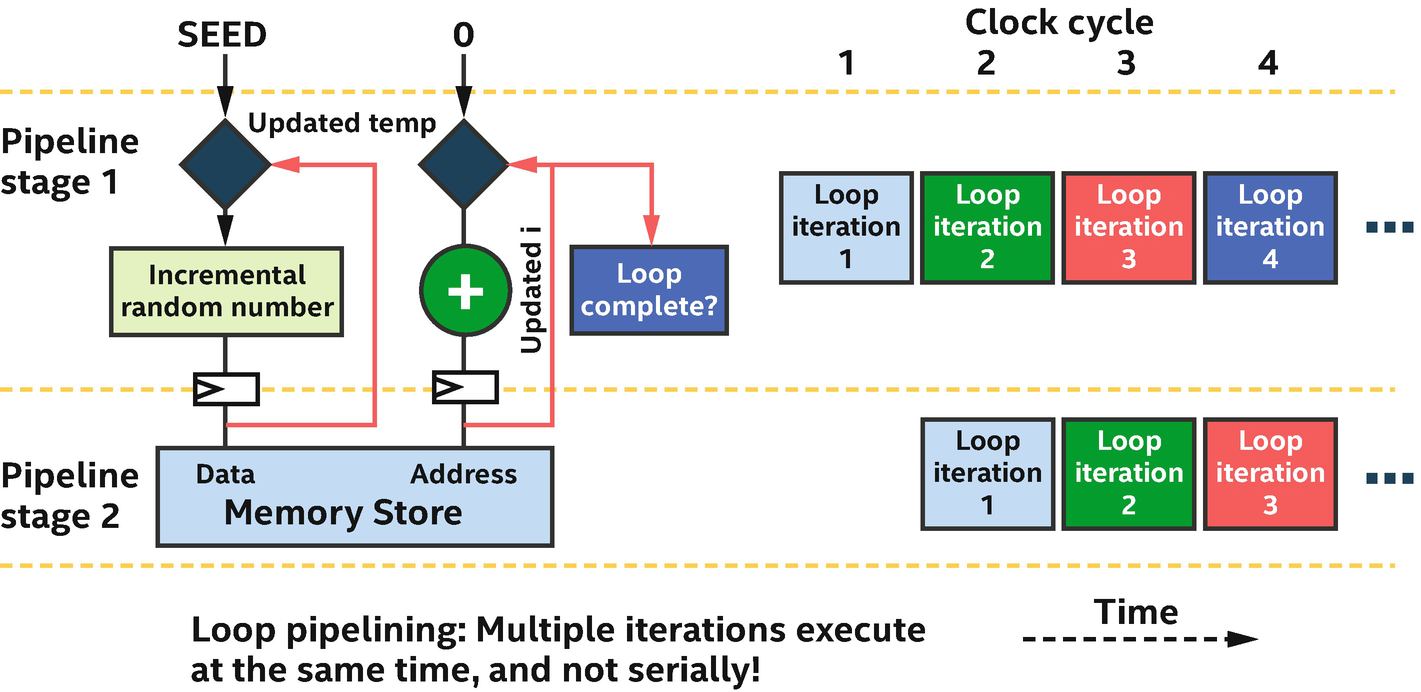

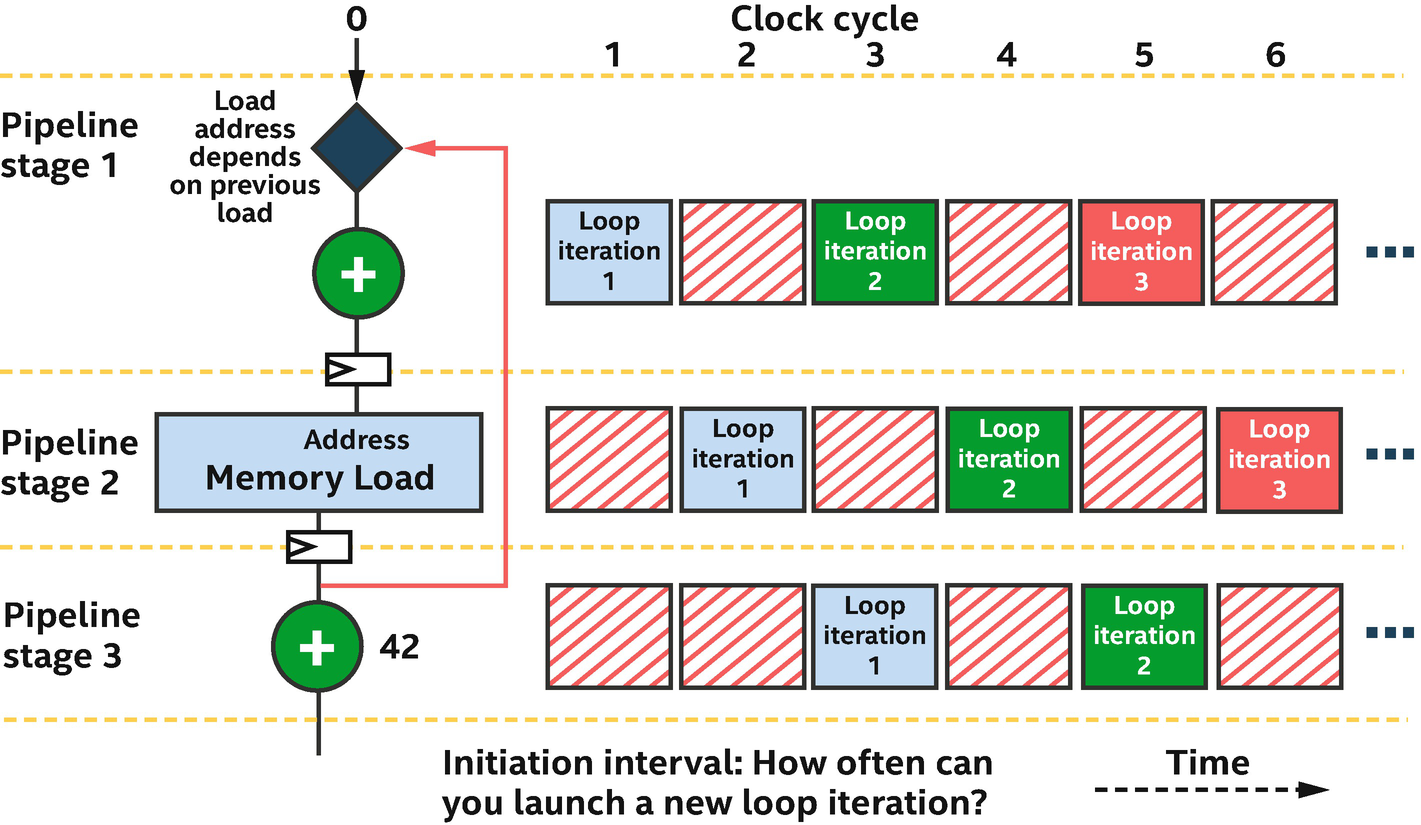

Loop Initiation Interval

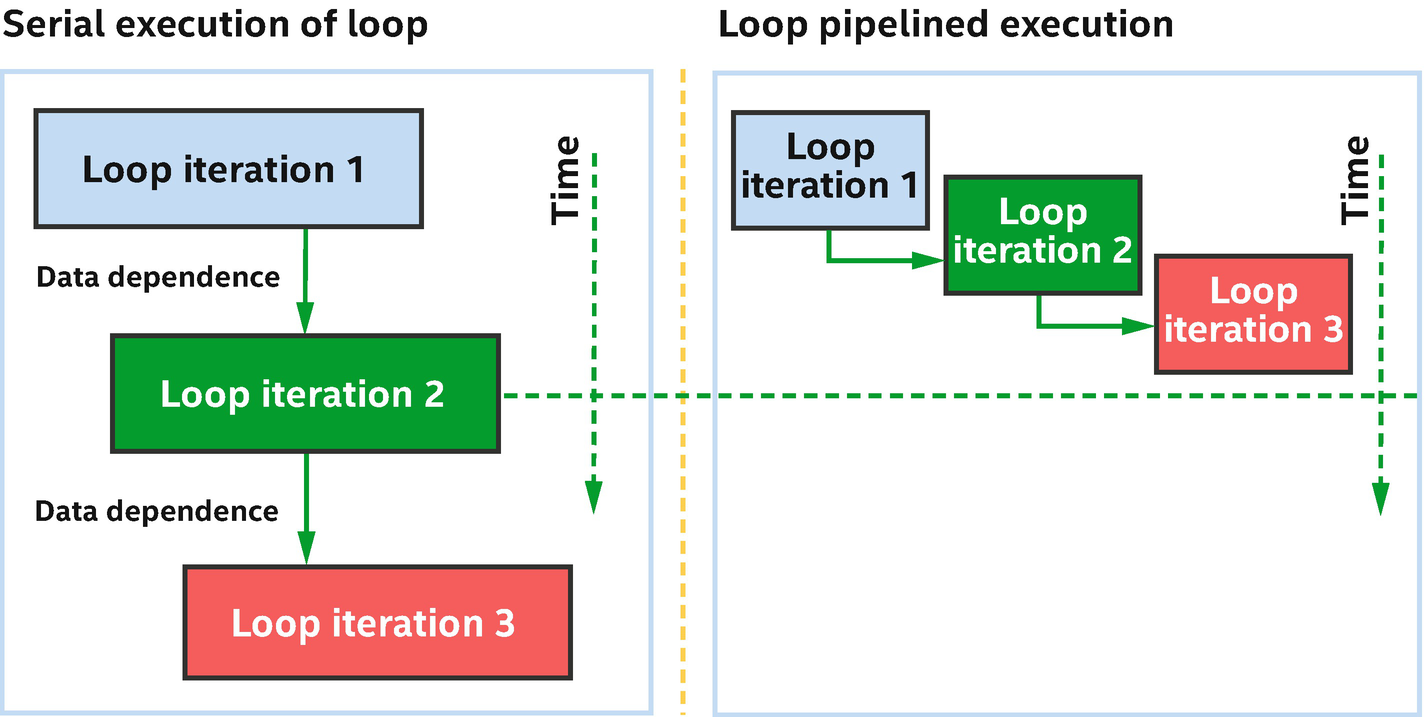

Conceptually , loop iterations execute one after another

Loop pipelining allows iterations of the loop to be overlapped across pipeline stages

A pipelined implementation of the incremental random number generator

Loop pipelining simultaneously processes parts of multiple loop iterations

Sub-optimal occupancy of pipeline stages

An II larger than one can lead to inefficiency in the pipeline because the average occupancy of each stage is reduced. This is apparent from Figure 17-27 where II=2 and pipeline stages are unused a large percentage (50%!) of the time. There are multiple ways to improve this situation.

The compiler performs extensive optimization to reduce II whenever possible, so its reports will also tell us what the initiation interval of each loop is and give us information on why it is larger than one, if that occurs. Restructuring the compute in a loop based on the reports can often reduce the II, particularly because as developers, we can make loop structural changes that the compiler isn’t allowed to (because they would be observable). Read the compiler reports to learn how to reduce the II in specific cases.

An alternative way to reduce inefficiency from an II that is larger than one is through nested loops, which can fill all pipeline stages through interleaving of outer loop iterations with those of an inner loop that has II>1. Check vendor documentation and the compiler reports for details on using this technique.

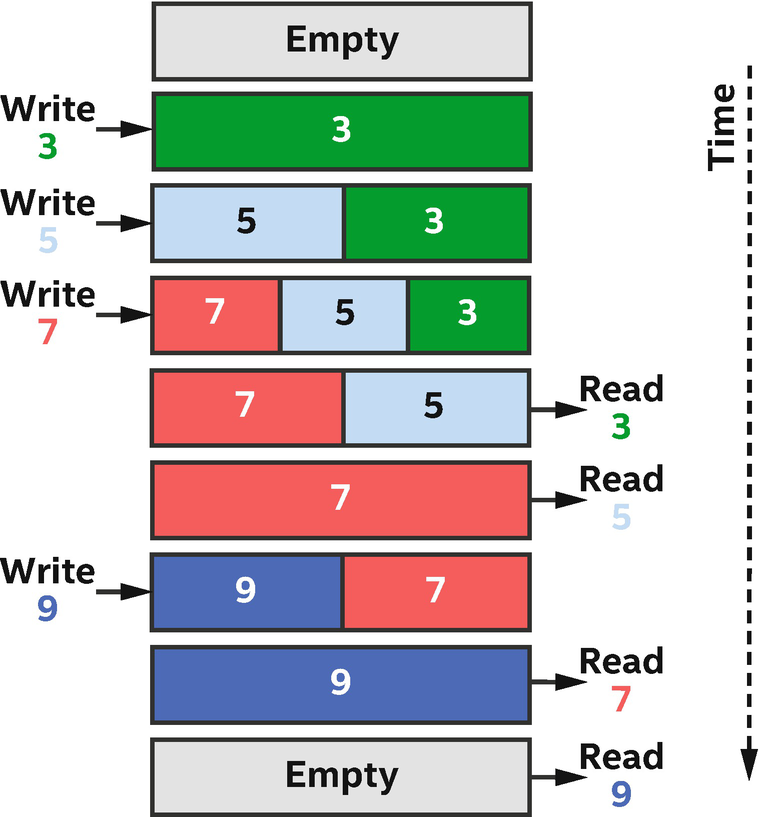

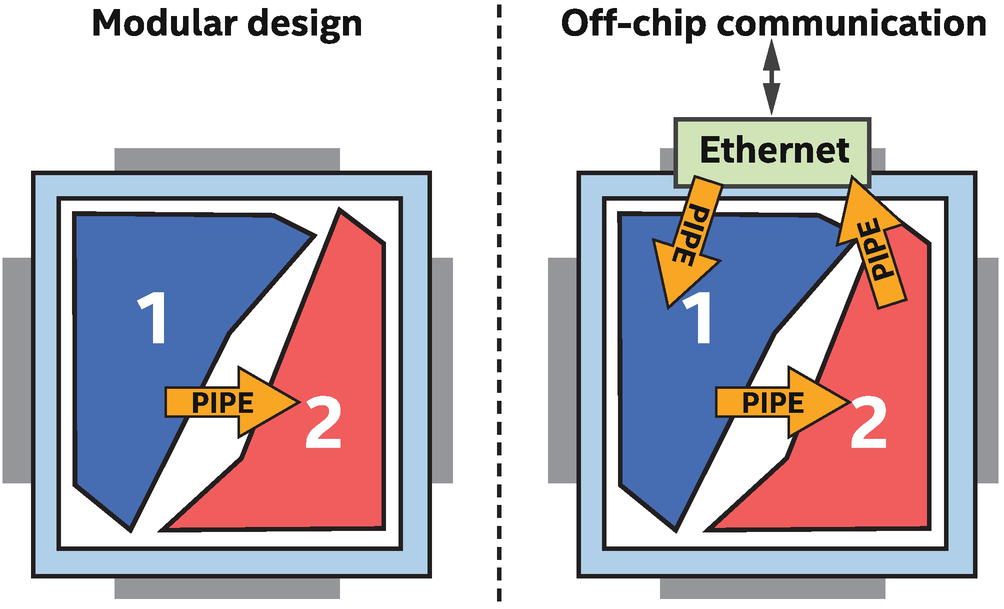

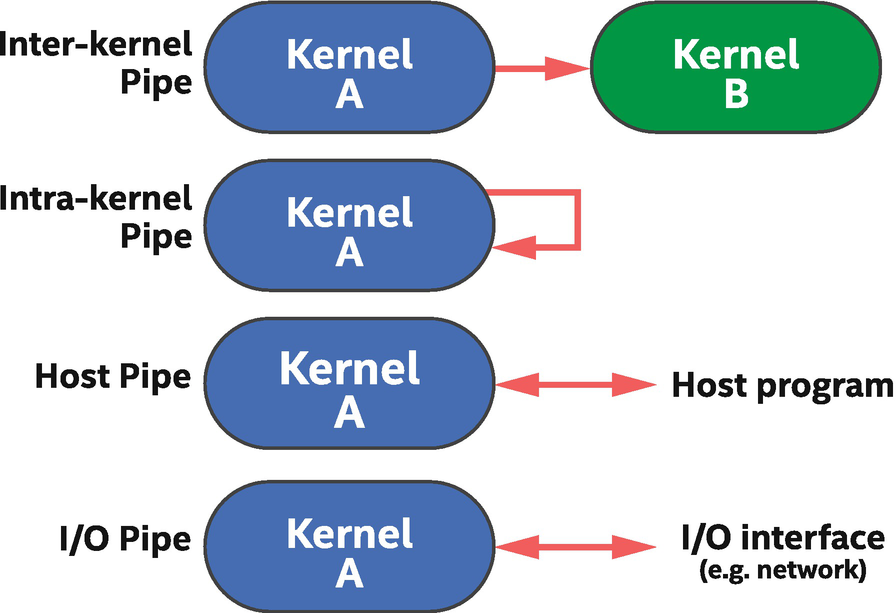

Pipes

- 1.

There is implicit control information carried alongside the data. These signals tell us whether the FIFO is empty or full and can be useful when decomposing a problem into independent pieces.

- 2.

FIFOs have storage capacity. This can make it easier to achieve performance in the presence of dynamic behaviors such as highly variable latencies when accessing memory.

Example operation of a FIFO over time

Pipes simplify modular design and access to hardware peripherals

Remember that FPGA kernels can exist on the device simultaneously (in different areas of the chip) and that in an efficient design, all parts of the kernels are active all the time, every clock cycle. This means that optimizing an FPGA application involves considering how kernels or parts of kernels interact with one another, and pipes provide an abstraction to make this easy.

Pipes are FIFOs that are implemented using on-chip memories on an FPGA, so they allow us to communicate between and within running kernels without the cost of moving data to off-chip memory. This provides inexpensive communication, and the control information that is coupled with a pipe (empty/full signals) provides a lightweight synchronization mechanism.

No. It is possible to write efficient kernels without using pipes. We can use all of the FPGA resources and achieve maximum performance using conventional programming styles without pipes. But it is easier for most developers to program and optimize more modular spatial designs, and pipes are a great way to achieve this.

Types of pipe connectivity in DPC++

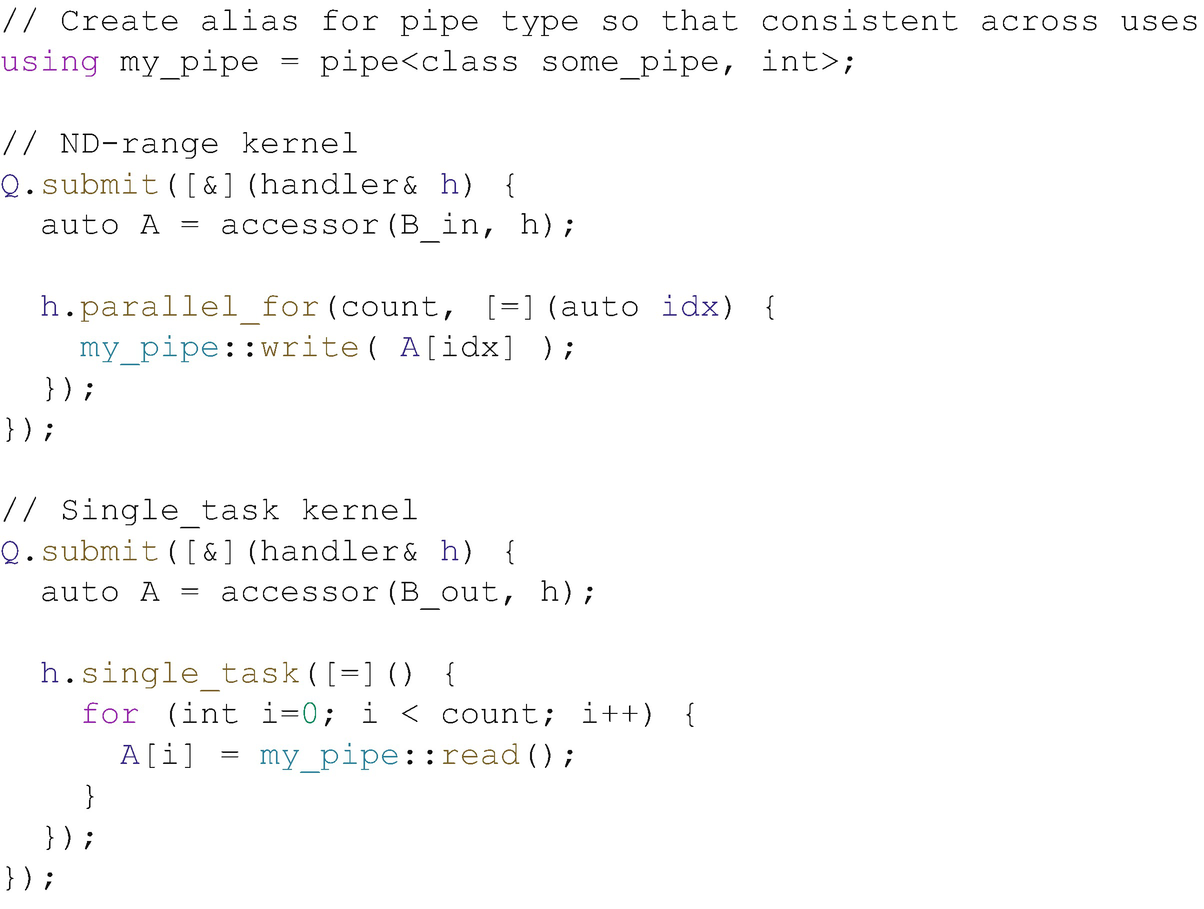

Pipe between two kernels: (1) ND-range and (2) single task with a loop

There are a few points to observe from Figure 17-31. First, two kernels are communicating with each other using a pipe. If there are no accessor or event dependences between the kernels, the DPC++ runtime will execute both at the same time, allowing them to communicate through the pipe instead of full SYCL memory buffers or USM.

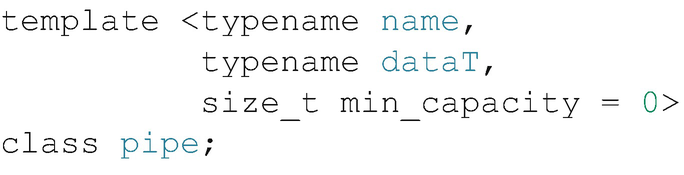

Parameterization of the pipe type

It is recommended to use type aliases to define our pipe types, as shown in the first line of code in Figure 17-31, to reduce programming errors and improve code readability.

Use type aliases to identify pipes. This simplifies code and prevents accidental creation of unexpected pipes.

- 1.

Two kernels communicating with a pipe do not run at the same time, and we need enough capacity in the pipe for a first kernel to write all of its outputs before a second kernel starts to run and reads from the pipe.

- 2.

If kernels generate or consume data in bursts, then adding capacity to a pipe can provide isolation between the kernels, decoupling their performance from each other. For example, a kernel producing data can continue to write (until the pipe capacity becomes full), even if a kernel consuming that data is busy and not ready to consume anything yet. This provides flexibility in execution of kernels relative to each other, at the cost only of some memory resources on the FPGA.

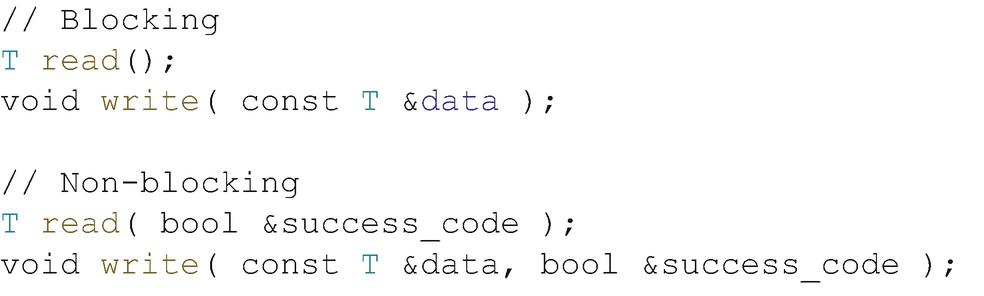

Blocking and Non-blocking Pipe Accesses

Like most FIFO interfaces, pipes have two styles of interface: blocking and non-blocking. Blocking accesses wait (block/pause execution!) for the operation to succeed, while non-blocking accesses return immediately and set a Boolean value indicating whether the operation succeeded.

Member functions of a pipe that allow it to be written to or read from

Both blocking and non-blocking accesses have their uses depending on what our application is trying to achieve. If a kernel can’t do any more work until it reads data from the pipe, then it probably makes sense to use a blocking read. If instead a kernel wants to read data from any one of a set of pipes and it is not sure which one might have data available, then reading from pipes with a non-blocking call makes more sense. In that case, the kernel can read from a pipe and process the data if there was any, but if the pipe was empty, it can instead move on and try reading from the next pipe that potentially has data available.

For More Information on Pipes

We could only scratch the surface of pipes in this chapter, but we should now have an idea of what they are and the basics of how to use them. FPGA vendor documentation has a lot more information and many examples of their use in different types of applications, so we should look there if we think that pipes are relevant for our particular needs.

Custom Memory Systems

When programming for most accelerators, much of the optimization effort tends to be spent making memory accesses more efficient. The same is true of FPGA designs, particularly when input and output data pass through off-chip memory.

- 1.

To reduce required bandwidth, particularly if some of that bandwidth is used inefficiently

- 2.

To modify access patterns on a memory that is leading to unnecessary stalls in the spatial pipeline

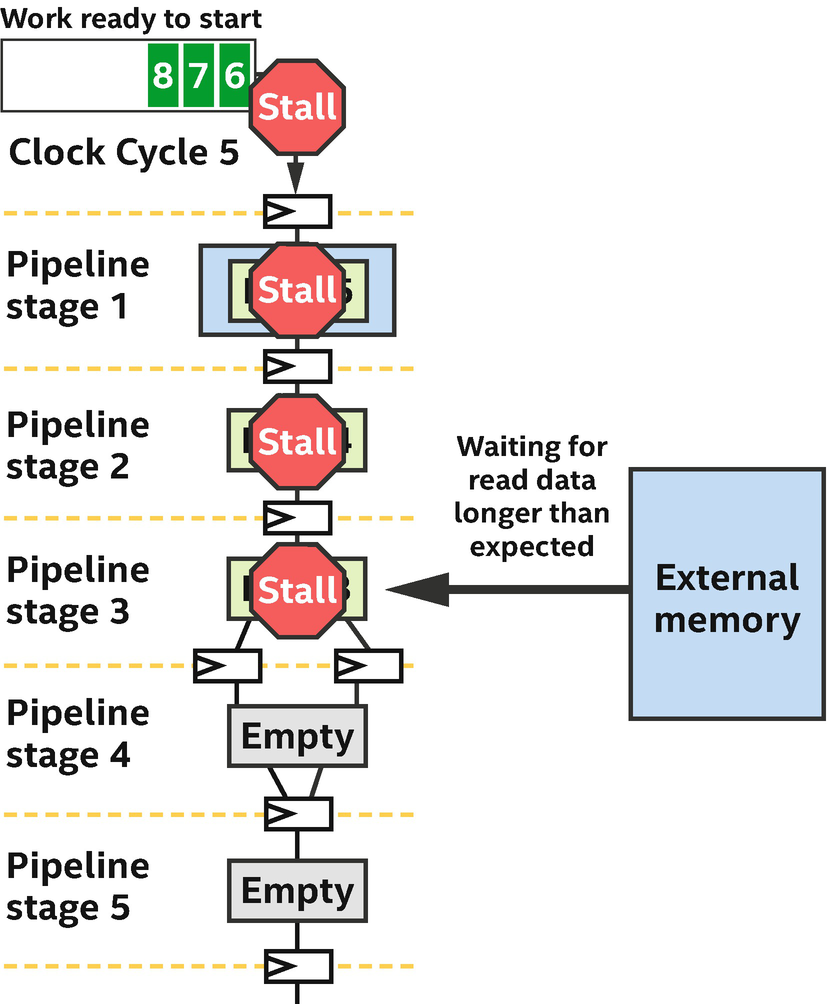

How a memory stall can cause earlier pipeline stages to stall as well

- 1.

Static coalescing : The compiler will combine memory accesses into a smaller number of wider accesses, where it can. This reduces the complexity of a memory system in terms of numbers of load or store units in the pipeline, ports on the memory system, the size and complexity of arbitration networks, and other memory system details. In general, we want to enable static coalescing wherever possible, which we can confirm through the compiler reports. Simplifying addressing logic in a kernel can sometimes be enough for the compiler to perform more aggressive static coalescing, so always check in the reports that the compiler has inferred what we expect!

- 2.

Memory access style: The compiler creates load or store units for memory accesses, and these are tailored to both the memory technology being accessed (e.g., on-chip vs. DDR vs. HBM) and the access pattern inferred from the source code (e.g., streaming, dynamically coalesced/widened, or likely to benefit from a cache of a specific size). The compiler reports tell us what the compiler has inferred and allow us to modify or add controls to our code, where relevant , to improve performance.

- 3.

Memory system structure: Memory systems (both on- and off-chip) can have banked structures and numerous optimizations implemented by the compiler. There are many controls and mode modifications that can be used to control these structures and to tune specific aspects of the spatial implementation.

Some Closing Topics

When talking with developers who are getting started with FPGAs, we find that it often helps to understand at a high level the components that make up the device and also to mention clock frequency which seems to be a point of confusion. We close this chapter with these topics.

FPGA Building Blocks

To help with an understanding of the tool flows (particularly compile time), it is worth mentioning the building blocks that make up an FPGA. These building blocks are abstracted away through DPC++ and SYCL, and knowledge of them plays no part in typical application development (at least in the sense of making code functional). Their existence does, however, factor into development of an intuition for spatial architecture optimization and tool flows, and occasionally in advanced optimizations when choosing the ideal data type for our application, for example.

- 1.

Look-up tables : Fundamental blocks that have a few binary input wires and produce a binary output. The output relative to the inputs is defined through the entries programmed into a look-up table. These are extremely primitive blocks, but there are many of them (millions) on a typical modern FPGA used for compute. These are the basis on which much of our design is implemented!

- 2.

Math engines: For common math operations such as addition or multiplication of single-precision floating-point numbers, FPGAs have specialized hardware to make those operations very efficient. A modern FPGA has thousands of these blocks—some devices have more than 8000—such that at least these many floating-point primitive operations can be performed in parallel every clock cycle! Most FPGAs name these math engines Digital Signal Processors (DSPs).

- 3.

On-chip memory: This is a distinguishing aspect of FPGAs vs. other accelerators, and memories come in two flavors (more actually, but we won’t get into those here): (1) registers that are used to pipeline between operations and some other purposes and (2) block memories that provide small random-access memories spread across the device. A modern FPGA can have on the order of millions of register bits and more than 10,000 20 Kbit RAM memory blocks. Since each of those can be active every clock cycle, the result is significant on-chip memory capacity and bandwidth, when used efficiently.

- 4.

Interfaces to off-chip hardware: FPGAs have evolved in part because of their very flexible transceivers and input/output connectivity that allows communications with almost anything ranging from off-chip memories to network interfaces and beyond.

- 5.

Routing fabric between all of the other elements: There are many of each element mentioned in the preceding text on a typical FPGA, and the connectivity between them is not fixed. A complex programmable routing fabric allows signals to pass between the fine-grained elements that make up an FPGA.

Given the numbers of blocks on an FPGA of each specific type (some blocks are counted in the millions) and the fine granularity of those blocks such as look-up tables, the compile times seen when generating FPGA configuration bitstreams may make more sense. Not only does functionality need to be assigned to each fine-grained resource but routing needs to be configured between them. Much of the compile time comes from finding a first legal mapping of our design to the FPGA fabric, before optimizations even start!

Clock Frequency

FPGAs are extremely flexible and configurable, and that configurability comes with some cost to the frequency that an FPGA runs at compared with an equivalent design hardened into a CPU or any other fixed compute architecture. But this is not a problem! The spatial architecture of an FPGA more than makes up for the clock frequency because there are so many independent operations occurring simultaneously, spread across the area of the FPGA. Simply put, the frequency of an FPGA is lower than other architectures because of the configurable design, but more happens per clock cycle which balances out the frequency. We should compare compute throughput (e.g., in operations per second) and not raw frequency when benchmarking and comparing accelerators.

This said, as we approach 100% utilization of the resources on an FPGA, operating frequency may start to decrease. This is primarily a result of signal routing resources on the device becoming overused. There are ways to remedy this, typically at the cost of increased compile time. But it’s best to avoid using more than 80–90% of the resources on an FPGA for most applications unless we are willing to dive into details to counteract frequency decrease.

Rule of thumb Try not to exceed 90% of any resources on an FPGA and certainly not more than 90% of multiple resources. Exceeding may lead to exhaustion of routing resources which leads to lower operating frequencies, unless we are willing to dive into lower-level FPGA details to counteract this.

Summary

In this chapter, we have introduced how pipelining maps an algorithm to the FPGA’s spatial architecture. We have also covered concepts that can help us to decide whether an FPGA is useful for our applications and that can help us get up and running developing code faster. From this starting point, we should be in good shape to browse vendor programming and optimization manuals and to start writing FPGA code! FPGAs provide performance and enable applications that wouldn’t make sense on other accelerators, so we should keep them near the front of our mental toolbox!

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.