Chapter 17

Solid and Hazardous Waste

Sven E. Rodenbeck and Henry Falk

Dr. Rodenbeck and Dr. Falk report no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of this chapter.

Humans, like all animal species, are producers of wastes. It is significant, however, that as humankind has evolved, the character of the waste produced has changed markedly. No other species in the animal kingdom shares this trait. Like animals' waste, the waste of early humans was highly organic. It consisted of such materials as excreta, bedding materials, crude clothing, and implements. As humans evolved, however, refined materials such as paper and cloth and also inorganic materials such as ceramics and metals were added to their wastes.

For many centuries human waste products reflected a fundamentally agrarian lifestyle. As human endeavors evolved to include more technology and industry, the mix of wastes produced by society changed radically and irrevocably. Mining spoils, ashes and slag from metal processing, and other industrial wastes became commonplace. As industry grew in complexity throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the waste mix became more varied and complex to manage. Waste management has emerged as a significant challenge because of the growing variety of wastes and the trend throughout the twentieth century toward more packaging and disposability features.

Finally, along with the industrialization and modernization of society, the steady trend toward urbanization of much of the population has challenged waste management. As cities became more crowded, a shortage of space to accommodate all the waste developed. In developed countries, open dumping and backyard burn barrels are generally frowned upon as means of waste disposal. This chapter describes the types of wastes produced by modern society, the significance of these wastes with respect to human health and the environment, and some of the ways in which these wastes are managed.

Solid Waste

Determining whether something is solid waste is not a trivial matter. People have debated for years about what solid waste is and how it should be managed. In fact some material that is managed as solid waste is not a solid at room temperature but rather a liquid or gas (e.g., gases in cylinders). A fundamental premise is that a material is waste if it no longer has value—a judgment that may be subjective and may vary over time. On occasion, material designated as waste was later found to have value. For example, using new technology former mining wastes have been reextracted to recover residual metals. Cultural norms also influence waste value judgments. Western industrial societies often throw away material with little thought of reuse or repair alternatives. However, as a starting point, the fundamental premise that it lacks value is probably adequate to characterize solid waste.

In the United States and in most developed industrial countries, waste material is typically divided into three broad categories:

- Municipal solid waste

- Special waste

- Hazardous waste

Complex laws and regulations govern how these materials are identified, stored, collected, transported, treated, and finally disposed of (Text Box 17.1).

Municipal Solid Waste

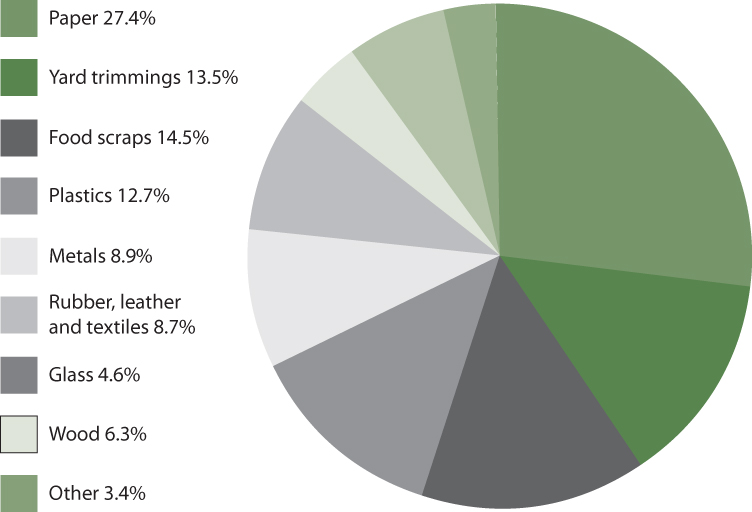

Municipal solid waste consists of everyday items that are commonly generated from homes. Over half of the U.S. municipal solid waste generated in 2012 consisted of containers, packaging, and nondurable goods such as newspapers and magazines (Figure 17.2). Other major components of municipal solid waste include yard trimmings, food wastes, and durable goods such as appliances, tires, and batteries. Local laws and regulations may prohibit the disposal of some of these materials (such as tires) as municipal solid waste. More and more frequently, municipal and county governments are also prohibiting the disposal of yard clippings with municipal solid waste, requiring that the clippings be composted or disposed of in some other, more environmentally friendly manner.

Figure 17.2 Composition of the 251 Million Tons of Municipal Solid Waste Produced in the United States (Before Recycling), 2012

Source: Adapted from U.S. EPA, 2012a.

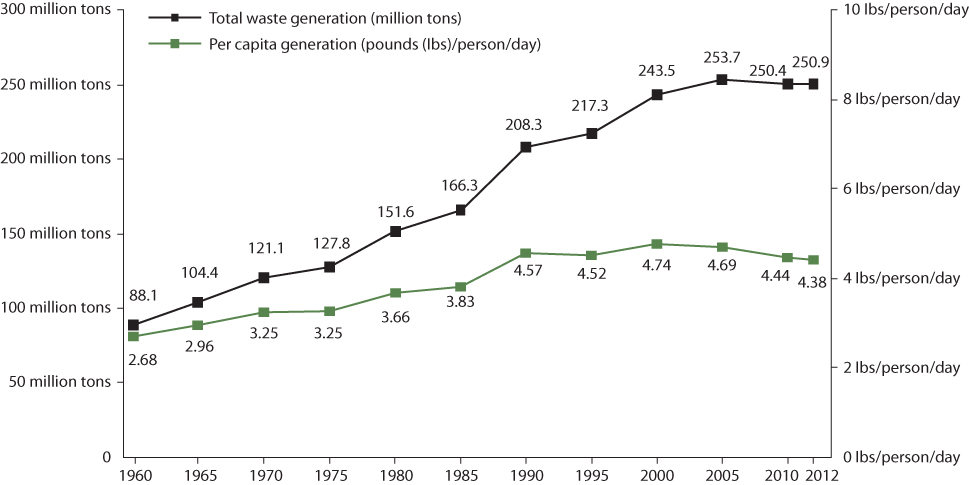

In the United States the per capita generation of municipal solid waste has steadily increased over recent decades. In 2012, the average American generated approximately 4.38 pounds of waste each day, a 70% increase from the 1960 average of 2.7 pounds per person per day (Figure 17.3).

Figure 17.3 Total Amount and Per Capita Generation Rate of Municipal Solid Waste Produced in the United States (Before Recycling), 1960–2012

Source: Adapted from U.S. EPA, 2012a.

According to the World Bank, approximately 1.3 billion tons of municipal solid waste is generated each year, and that number is expected to increase to 2.2 billion tons by 2025 (Hoornweg & Bhada-Tata, 2012). The amount of waste generated per person varies by economic status, with low- and high-income individuals generating about 1.3 and 4.7 pounds per person per day, respectively. Waste generated by lower income individuals tends to have more organic material (65% for low-income versus 28% for high-income) and less paper (5% for low-income versus 31% for high-income).

Special Waste

Special waste is a catchall category. However, if a waste is neither municipal solid waste nor a designated hazardous waste, it likely has a special designation and associated laws or regulations. Some commonly identified special wastes are

- Medical waste

- Construction debris

- Asbestos

- Mining waste

- Agricultural waste

- Radioactive waste

- Sewage sludge

- Electronic waste

Medical Waste

Medical waste includes items that are generated from health care treatment or research facilities (human and nonhuman) and that have come into contact with bodily fluids (e.g., blood) or other materials that may contain infectious agents and may cause disease. Some examples of medical waste are

- Soiled or blood-soaked bandages

- Culture dishes and other associated glassware

- Items such as gloves, gowns, and scalpels used during surgery

- Needles used to give injections or draw blood

- Bodily fluids and tissues

One of the reasons medical waste is handled separately from municipal solid waste is to protect sanitation workers from infectious agents in the waste materials. The challenge of medical waste is further explored in Text Box 17.2.

Construction Debris

Unless a construction material is regulated separately (as asbestos is, for example), the construction debris waste stream consists of material generated from the construction and demolition of buildings and other facilities. Typically this rubble is disposed of in specific construction debris landfills or in municipal solid waste landfills. Recent research has found that construction debris is not as innocuous as previously thought. If water is allowed to infiltrate through the waste drywall (gypsum wallboard) in a landfill, hydrogen sulfide can be formed, and the surrounding population could be exposed to hydrogen sulfide levels that are a health concern (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry [ATSDR], 2006).

Asbestos

In the United States asbestos is designated as a special waste, with its own rules and regulations. In the past this class of fibrous minerals was used extensively in such consumer products as car brake linings and construction materials (see Tox Box 20.3, in Chapter 20). Most uses of asbestos have been banned in the United States because of its demonstrated capacity to cause disease in workers and other exposed people. To prevent the airborne release of asbestos fibers, federal regulations provide detailed guidance on the removal, packaging, and disposal of materials containing asbestos.

Mining Waste

The extraction of metals, coal, and oil from the Earth's crust generates huge quantities of mining waste materials. The volume of wastes from mining operations exceeds the volume of wastes from all other categories combined (U.S. EPA, 1985). The disposal of this leftover rubble and liquid material is regulated both by solid waste laws and regulations and by water pollution control and land-use and reuse laws and regulations.

Recent technical advances in oil and natural gas extraction from shale formations, using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, have resulted in the generation of a new mining waste stream. Fracking generates large quantities of liquid waste that can contain high levels of total dissolved solids (TDS), fracturing fluid additives, metals, and naturally occurring radioactive materials. The U.S. government and state governments have taken different approaches to regulating this new waste stream. For example, New York State has banned any use of fracking within state boundaries, Pennsylvania has declined to regulate fracking activities, and the U.S. government has issued regulations that require specific waste management practice for wells being developed on federal or tribal lands (New York State Department of Health, 2014; A Rule by the Land Management Bureau, 2015).

Agricultural Waste

In technologically advanced countries the production of food has become highly industrialized. A common arrangement for raising animals on a large scale is the concentrated animal feed operation (CAFO). As described in Chapter 19, CAFOs can bring thousands of poultry, swine, or cattle together in confined spaces. These facilities can become large-scale sources of agricultural waste in the form of air emissions (such as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, odors, and particles contaminated with a wide range of microorganisms) (Heederik et al., 2007) and animal waste. The animal waste in turn contains nutrients, microbes, and veterinary chemicals. For example, where antibiotics have been used in raising animals, they can be discharged through waste into the environment, where they may contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant pathogens (Gilchrist et al., 2007; Silbergeld, Graham, & Price, 2008). Recent U.S. Food and Drug Administration guidance issued in December 2013 should reduce the amount of antibiotics used in this manner (A Notice by the Food and Drug Administration, 2013). The waste stream may also contain other veterinary chemicals, such as arsenic (Silbergeld & Nachman, 2008). The EPA's clean water protection program regulates the management of the liquid waste and the sludge, or manure, coming from animal feed lots and CAFOs. Those waste materials not regulated by federal laws are managed either by local authorities or in accordance with best practices developed by the industry. There is concern, however, that these protective strategies may not suffice to protect the public's health (Burkholder et al., 2007).

Radioactive Waste

Radioactive waste contains radioactive chemical elements. Generally, it is divided into two subcategories: low-level waste and high-level waste. Low-level waste consists of used protective clothing and other items that contain low levels of radioactivity per mass or volume. This waste is typically disposed of in specifically designated landfills. High-level radioactive waste consists of spent nuclear fuel and waste materials left after spent fuel is reprocessed. The disposal of this nuclear waste is very controversial. The United States has been trying for years to establish a permanent, high-level radioactive waste repository inside Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Currently, most of the high-level radioactive waste in the United States is stored temporarily in spent fuel pools and in dry cask storage facilities.

Sewage Sludge

Before waste water is discharged back into the environment, it undergoes a series of treatments (mostly biological and chemical) to remove or break down any hazardous biological or chemical constituents. One of the main by-products of this treatment processes is sewage sludge, which is made up primarily of concentrated solid materials. The disposal of sewage sludge is regulated, and the methods allowed are based on whether any hazardous materials are present. Some sewage sludge is safe enough after it has been disinfected to be applied to cropland.

Electronic Waste

More commonly called e-waste, electronic waste includes unwanted, obsolete, or unusable electronic equipment such as computers, computer display monitors, televisions, VCRs, DVD players, cell phones, and electronic games. This waste stream is described in Text Box 17.3.

Hazardous Waste

Hazardous waste can be defined simply as waste with properties that make it capable of harming human health or the environment. However, for regulatory purposes this simple definition is not sufficient. In the United States the EPA, in order to carry out the RCRA provisions, has developed specific criteria for defining hazardous waste. Two different mechanisms are applied. The first is to include the materials from approximately 500 specific industrial waste streams. These listed wastes include spent solvents, electroplating wastes, and wood-preserving wastes. The second mechanism relates to the waste's characteristics. The EPA has developed standardized test criteria to determine a waste's ignitability, corrosiveness, reactivity, and toxicity. If a waste possesses defined levels of any of these characteristics, it is classified as hazardous. At the same time, under the terms of the Act many waste materials (such as petroleum) are specifically excluded from the hazardous waste definition and regulations.

In 2011, approximately 34 million tons of hazardous waste was generated in the United States (U.S. EPA, 2012b). The states that generated the most hazardous waste tended to be those with a large petrochemical industry.

In general, other industrialized countries designate hazardous waste much as the United States does, although they may use different coding or terminology.

Solid Waste Management Strategies

Because solid and hazardous wastes may affect human health and the environment, waste management is a fundamental part of environmental public health. Waste management is best accomplished through a multitier approach. The first tier is primary waste stream avoidance and reduction. Materials recycling, substitution of materials, and changes in consumer habits, among other methods, can help industries, communities, and other groups achieve waste stream reduction. All sectors of a modern society, when approached with effective informational campaigns and incentives, can practice waste avoidance and reduction.

The second tier of solid waste management involves proper handling and disposal of waste, that is, in a manner that protects the public health and the environment. Although complete avoidance of solid waste generation is the ideal, it is likely that there will always be some residual of mankind's activities requiring disposal.

In the United States, landfilling is the means of disposal for approximately 54% of municipal waste (U.S. EPA, 2012a). Hazardous waste is disposed of in landfills and surface impoundments (approximately 15%), energy recovery units (approximately 13%), metals recovery operations (approximately 13%), deep well or underground injection (approximately 10%), and other methods (U.S. EPA, 2012b). All of these approaches have public health implications.

Primary Prevention of Waste

The ideal waste management strategy is not to produce the waste in the first place. This goal can be approached in several ways: that is, through efforts to reduce, reuse, and recycle. In an industrial setting this goal might be achieved by altering production processes to avoid or reduce the use of a hazardous chemical. For example, in some electroplating operations, less toxic alternatives can replace highly toxic cyanide salts. In office settings, converting to electronic commerce and records management can reduce waste paper production. Industry is also using life cycle analysis to design and produce things that can readily reclaimed at the end of their expected life.

Waste reduction also applies to municipal wastes. The quantity of raw materials in food and beverage containers is being reduced because of economic pressures. In the past few decades, manufacturers have reduced the amount of steel and aluminum in cans and the amount of plastic in milk jugs and plastic bags. These efforts have reduced the cost of these containers and decreased the amount of waste to be disposed. Further reductions in packaging could be achieved if consumers routinely carried reusable canvas shopping bags instead of expecting plastic or paper bags with each purchase.

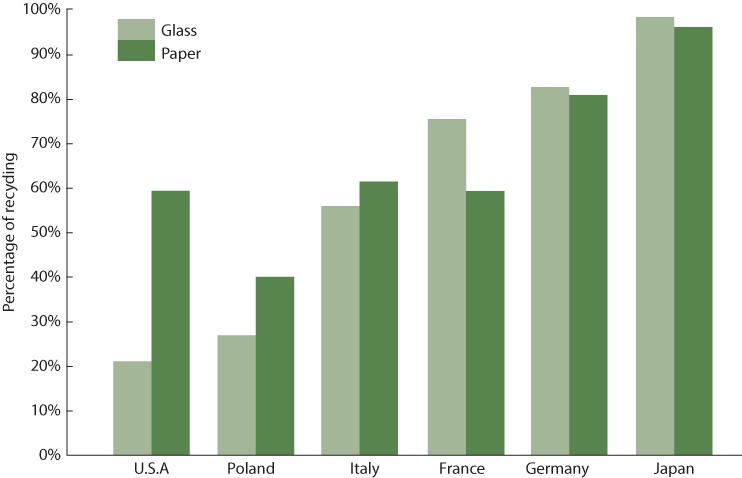

If the generation of waste cannot be avoided or reduced, then the next best alternative is to recycle the waste. Recycling can refer to using waste material to produce more of the original product or to using waste material in something else. Examples of the first kind of recycling include making glass or paper from used glass or paper and making new lead batteries from old lead batteries. An example of the second kind of recycling is using mining wastes as aggregate for asphalt and concrete production. In recent years, increased efforts to reduce the amount of trash dumped into landfills have led municipalities to encourage recycling of paper, plastic, aluminum, and glass. In some communities homeowners are also encouraged to compost yard waste to recycle it into a useful soil amendment. Recycling of municipal solid waste has steadily increased in the United States; today about 34.5% of municipal solid waste is recycled (Figure 17.4). Other industrialized nations tend to have a higher rate of recycling (Figure 17.5).

Figure 17.4 Total Amount and Percentage of Municipal Solid Waste Recycled in the United States, 1960–2012

Source: Adapted from U.S. EPA, 2012a.

Figure 17.5 Glass and Paper Recycling in Industrial Nations

Source: Zeller, 2008.

The importance of waste minimization has led to the emerging field of industrial ecology. Industrial ecology is the study of the physical, chemical, and biological interactions and interrelationships both within and between industrial systems and ecological systems (Garner & Keoleian, 1995). A primary goal of industrial ecology is to change the nature of our industrial systems from linear systems, in which raw materials are used and products and wastes are discarded, to cyclical systems that use the wastes as raw materials or energy for another product.

A famous example of an eco-industrial park is the Kalundborg industrial park in Denmark (Ehrenfeld & Gertler, 1997). In this park the companies reuse each other's wastes in the production of their own products. For example, Asnæsværket, a coal-fired power plant, captures sulfur dioxide from its flue stack gas and converts it to calcium sulfate (gypsum), which is sold to a drywall board plant. Another example is Novo Nordisk, a biotechnology company that produces insulin and industrial enzymes and then supplies biosludge waste to a nearby farm that uses it for fertilizer. These examples illustrate an industrial symbiosis in which energy and wastes are recycled and reused by another process within the system.

Waste Treatment and Disposal

As discussed earlier, it would be ideal if all solid and hazardous or special waste could be recycled, reused, or avoided. Unfortunately, this ideal goal may not be attained. As a result, society should strive to dispose of all such wastes in a manner that minimizes harm to human health and the environment (see the discussions in Text Boxes 17.4 and 17.5). Both budgetary limitations and the need to comply with applicable regulations influence selection of the most practical option.

In years past it was common to burn wastes in backyard barrels, open dumps, and crude incinerators. All these methods had undesirable environmental and health impacts. During the second half of the twentieth century, public demand and government regulations led to improved waste treatment and disposal methods in upper-middle- and high-income countries. Controlled or sanitary landfills replaced dumps. More sophisticated and controlled combustion systems replaced crude incinerators. Newer incinerators are specifically designed for the type of wastes burned, such as medical waste, industrial waste, or municipal solid waste. Some industrial wastes, such as liquid brines, are discharged far beneath the Earth's surface, through deep well injection. Potentially harmful industrial wastes that had been previously discarded haphazardly in dumps or burial pits are now treated with remedial technologies designed to reduce or limit harmful impacts.

Unfortunately, burning and dumping of wastes is still a common practice in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. For example, it is estimated that more than 40% of the world's waste is burned in an uncontrolled manner (Wiedinmyer, Yokelson, & Gullett, 2014). China and India are believed to have the most waste burned by residents, while China, Brazil, and Mexico burn the most waste at open dumps. The air emissions from these practices have been estimated to account for 29% of the global particulate matter, 10% of airborne mercury emissions, and 5% of the world's anthropogenic carbon dioxide (a potent greenhouse gas—see Chapter 12).

Sanitary Landfill

Open-burning municipal waste dumps, which were once prevalent throughout the United States, were the source of many environmental and public health problems. These problems included air pollution; groundwater pollution; and rats, flies, and other disease-carrying vectors, as well as nuisance odors and unsightly conditions. The creation of the EPA in 1970 prompted a major move in the United States to eliminate open dumps and replace them with the improved sanitary landfill. Careful site selection and preparation, the application of a daily covering of earth for each day's accumulation of waste, and other procedural provisions (e.g., not permitting the disposal of liquids) eliminated most of the problems with open dumping. Between 1996 and 2006, the number of operating municipal sanitary landfills in the United States decreased from about 3,100 to 1,754 (U.S. EPA, 2012a), as old small landfills were replaced by larger sanitary landfills. Current landfill capacity appears to be sufficient for total national needs, but some areas of the country lack adequate landfill capacity.

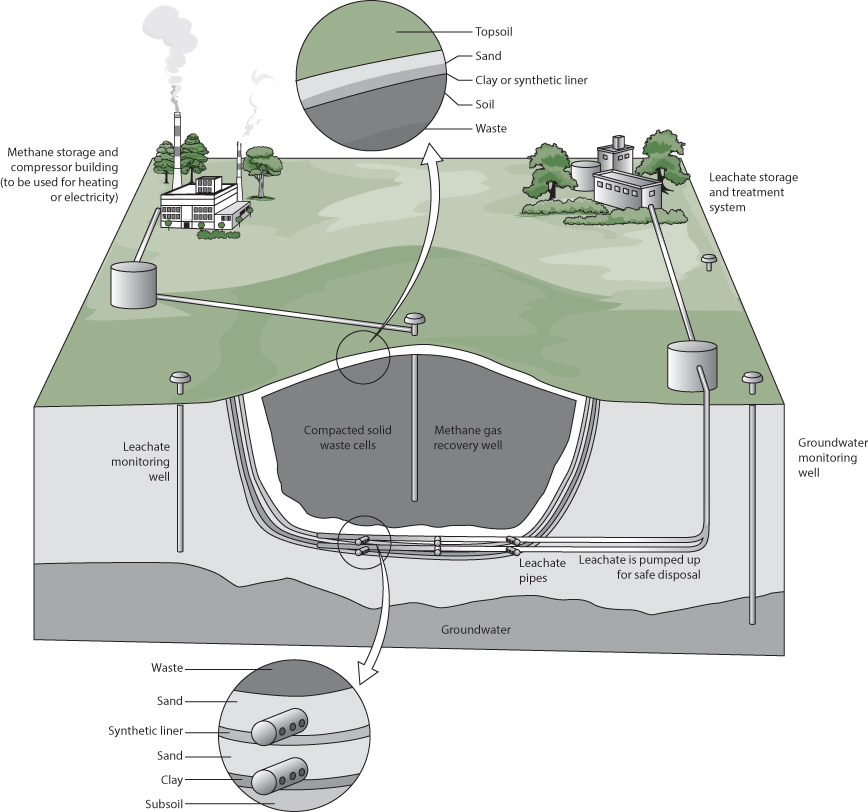

Sanitary landfills vary in design, depending on local site considerations. However, by definition, all sanitary landfills share certain design features and operating principles. These include selecting a location that has adequate space to provide waste disposal capacity for a reasonable time period, sufficient separation to protect regional surface and groundwaters, and an adequate buffer between the landfill and surrounding populations.

Once a landfill site has been selected and appropriate community concurrence and regulatory approval obtained, site preparation can begin. In addition to grading and installing sediment and erosion controls to protect local surface waters, provisions must also be made to protect groundwater from leachate. Leachate, a liquid, organic waste decomposition product, sometimes contaminated with chemicals, can migrate down and into the local aquifer. In the absence of a natural barrier, installing an underlying man-made impervious barrier can provide protection. Where significant amounts of leachate are anticipated, some landfills have systems to collect and treat the leachate. Similarly, provisions are often made for collecting and controlling the gaseous products of waste decomposition, consisting mainly of methane. In some cases the methane is cleaned and used as fuel for local energy production. Figure 17.7 provides a generalized depiction of a modern sanitary landfill.

Figure 17.7 Generalized Depiction of a State-of-the-Art Sanitary Landfill

Sanitary landfills are operated in a manner intended to contain and control waste. Each day's accumulation of waste is placed in its cell, compacted, and covered with earth. Usually waste is spread and compacted by heavy equipment on a sloped working face within the cell. This compaction reduces the waste volume, thereby extending the life of the landfill, and it also reduces the potential for fires, while the sloped working face diverts water from infiltrating into the waste. At the end of the day the working face and entire cell are covered with approximately six inches of compacted soil. This minimizes litter problems, helps control odors, and largely eliminates problems from animal and insect vectors. Some municipalities use precompacted, baled solid waste so landfill operators can stack the waste like building blocks each day and thereby maximize site life.

Industrial and hazardous waste landfills share many of the containment and control features of sanitary landfills; however, they are much more stringently regulated. The type of waste allowed in a given landfill is strictly defined in the operating permit. In some cases certain hazardous wastes must be specially treated, packaged, or stabilized before being placed in the landfill. Periodic analysis of the wastes may be required to ensure that adequate characterization of the fill is maintained. The ultimate use of the land after the landfill is closed must also be determined.

Incineration

Broadly defined, incineration is the controlled combustion of a waste. Incineration has been used for all types of wastes, including municipal solid wastes, sewage sludge, industrial and hazardous waste, and medical wastes. Some large municipal and industrial incinerators are designed to capture energy for reuse. The goal of incineration is to reduce the volume of the waste being processed or to reduce the hazardous characteristics of a particular waste stream, or both. All incineration attempts to control several variables in an effort to maximize the completeness of combustion. The classic 3 T's of combustion are:

- Time: the length of time that solids and combustion gases are in the ignition and burn zones of the incinerator

- Temperature: an indication of the amount of heat energy in the combustion chambers available to break molecular bonds and facilitate oxidation toward the desired end products of combustion (carbon dioxide, water vapor, inorganic ash)

- Turbulence: the agitation of both solids and the combustible by-products, needed to provide opportunity for complete oxidation to take place.

The other major factor in fundamental combustion control is the provision of adequate oxygen, usually in the form of combustion air, to complete all oxidation reactions. The theoretically required amount of air for complete combustion of a given waste stream is known as the stoichiometric air requirement. In actual incineration systems, air in excess of this requirement is provided to force the reaction toward complete oxidation of the organic wastes. This excess air is usually reported as a percentage of stoichiometric air.

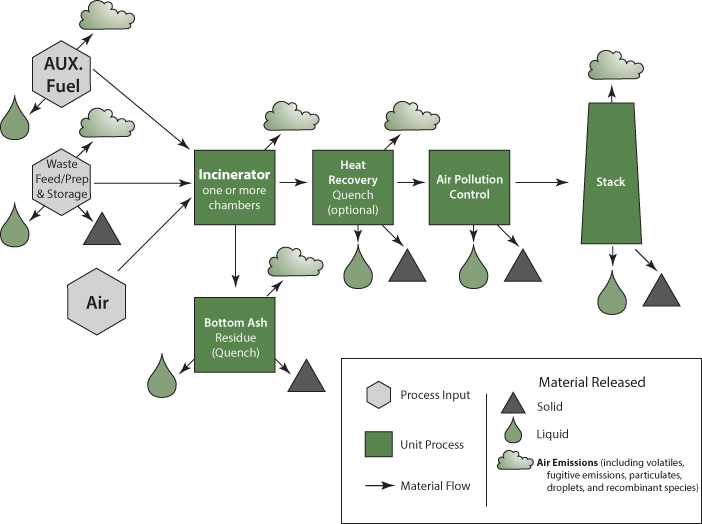

Specific incineration designs vary widely in the ways that wastes are introduced into the units and in the ways that air control and mixing are achieved (Figure 17.8). Some incinerators have multiple chambers for combustion. Ignition and preliminary combustion take place in a primary chamber. The volatile products from the primary chamber are oxidized to completion in a secondary chamber, or afterburner.

Figure 17.8 Generalized Diagram of Incineration Material and Process Flow

Early incinerators were noted for smoke, odors, and sometimes even live embers coming out of the exhaust stacks. Because of these unacceptable conditions, regulations now require strict air pollution control technology. Now, devices such as wet or caustic scrubbers control acid gas. Electrostatic precipitators, venturi scrubbers, and baghouses capture fine particulates. Some of the newest hazardous waste incinerators have a final activated-carbon filtration system. This polishing device minimizes emission of low-level products of incomplete combustion (PICs), such as dioxins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Inorganic waste contaminants, such as heavy metals (mercury, lead, and chromium, for example) can be difficult to control and can require special pollution control systems or elimination from the waste being fed to the incinerator. Because of increased traffic from trucks hauling in wastes and also because of odors and aesthetic objections, communities rarely welcome incinerators or waste landfills.

Deep Well Injection

Deep well injection is a liquid waste disposal technology that uses deep injection wells to force treated or untreated liquid waste into geological formations that do not allow migration of contaminants into potential potable water aquifers. These wells, typically several thousand feet deep, extend into permeable injection zones containing highly saline brines that render the water nonpotable. Impermeable rock or soil layers confine the injection zone vertically. The wastes injected can be radioactive wastes, hydrocarbon wastes, oil and gas drilling brines, hazardous wastes, and other wastes not suitable for landfill. In the United States injection wells are regulated and classified under an EPA definition that addresses uses and characteristics of such wells.

Injection wells can be located only in areas free of faults and other geological features that could allow wastes to migrate into potable water aquifers. Liquid wastes high in suspended solids, iron content, or organic substrates that could serve as food for microbial growth should not be disposed of in such wells because of their potential to foul or clog the well. Injection wells are double sleeved to allow monitoring for system integrity and to provide dual boundaries for protecting intervening geological layers.

Other Technologies

The previous discussion touches on some of the most prevalent methods for treatment and disposal of wastes, but many other waste treatment techniques are in practice or evolving. Treatment methods such as supercritical water oxidation, molten metals and molten salt oxidation, glass melt and vitrification processes, and waste-specific biological treatment systems and composting are a few such technologies. Dedicated treatment technologies, such as thermal desorption, have been developed for in situ and extractive remediation of old industrial waste disposal sites. Waste disposal technology has undergone tremendous technological evolution to keep pace with the changing character of society's waste products.

Health Concerns

Exposure to solid and hazardous wastes can adversely affect human health in several ways. The aesthetic impact of poor waste management—trash piling up in streets and vacant lots—can undermine the livability and even the safety of a community. At least five kinds of health hazards are well recognized:

- Infectious disease risks from poorly managed solid waste

- Contamination of drinking water and soil by biological, chemical, and mining wastes

- Gas migration and leachate discharges from landfills

- Emissions of air pollutants from incinerators

- Contamination of food by waste chemicals that escape into the environment

Poorly operated landfills can be havens for flies, mosquitoes, rats, and mice. Uncovered garbage and trash provide them with food, shelter, and a breeding ground. These insects and animals can be vectors for disease by carrying pathogenic microbes into the surrounding community. As described in chapter 18, rats and mice can spread a range of diseases to humans, including leptospirosis, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (CDC, 2008). Furthermore, rats can carry many kinds of mites, lice, fleas, and ticks that act as disease vectors. Modern landfills, which require wastes to be covered daily with clean soil, have greatly reduced the spread of disease by these vectors.

Improper disposal of solid and hazardous wastes can contaminate drinking water. Both groundwater and surface water can be affected. Most old landfills or dumps lack liners, which allows chemicals buried in the landfill to leach down into the underlying aquifer. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, and petroleum distillates are common contaminants in municipal and industrial landfills. These organic solvents are widely used as degreasers, dry cleaning fluids, and components of paints, varnishes, and adhesives. Because these chemicals are highly mobile, they readily migrate through unlined landfills into the underlying groundwater. Heavy metals in landfills, such as lead, cadmium, mercury, and chromium, can also be a source of groundwater contamination. Moreover, microbial degradation of garbage and vegetative wastes in a landfill can produce organic acids that lower the pH of the milieu, making buried metals more soluble. Old industrial sites where waste chemicals were sometimes dumped into open pits or onto the ground have also been known to contaminate nearby groundwater. If the contaminated groundwater migrates off site, it can affect people who drink from down-gradient private and public water wells. In Hardeman County, Tennessee, for example, leachate from a hazardous waste landfill contaminated private drinking-water wells with carbon tetrachloride and other VOCs (Clark et al., 1982). People who drank from these wells experienced headaches, nausea, and visual disturbances. Physicians who examined the victims reported that several of them had enlarged livers. In addition, clinical laboratory tests documented the presence of elevated levels of liver enzymes and altered serum chemistries, evidence of liver toxicity. Fortunately, these abnormalities resolved several months after the people stopped drinking the contaminated water.

Municipal landfills can also be a source of air pollutants such as methane, hydrogen sulfide, and VOCs. Anaerobic microbial digestion of organic matter buried in landfills generates large quantities of methane gas. In 1969, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, methane gas from a landfill migrated underground through the soil into the basement of an armory building adjacent to the landfill. The methane built up to an explosive level in the basement, and a lit cigarette triggered an explosion that killed three men and injured five others. Methane and carbon dioxide released to the atmosphere from landfills can also have ecological effects, given that these gases may contribute to global warming (see Chapter 12). It has been estimated that landfills accounted for about 23% of total U.S. methane emissions to the atmosphere from anthropogenic sources in 2006 (U.S. EPA, 2008).

As mentioned, wastes from mining and petroleum production form the largest category of solid wastes produced in the United States. Huge piles of mine tailings, left behind after the extraction of metals, are a potential source of environmental contamination (Figure 17.9). Smelters are often located near the mining areas and release additional metal-contaminated particulates to the ambient air and soil. At several mining and smelting sites, it has been demonstrated that children's exposure to lead-contaminated soil has contributed to increased blood lead concentrations (Gulson et al., 1994; Murgueytio et al., 1998). Such exposures are of health concern because there is no clear threshold for lead-induced neurotoxicity in children (Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention, 2012) (see Tox Box 11.1).

Figure 17.9 Mine Tailings Pile: The Legacy of Sixty Years of Lead and Zinc Mining in Ottawa County, Oklahoma

Source: Photo supplied by Ken Orloff.

Municipal and hazardous waste incinerators and open burning of waste releases particulates, vapors, and gases to the ambient air that are also of potential health concern. Burning even nontoxic materials, such as wood and paper, produces particulate matter, carbon monoxide, aldehydes, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In addition, burning commonplace materials, such as paints, solvents, insecticides, and plastics, can produce chlorinated dibenzodioxins and chlorinated dibenzofurans, collectively known as dioxins (see Tox Box 19.1 in Chapter 19). Small amounts of dioxins are released from hazardous waste incinerators, which operate under strict environmental regulations. Backyard burning of household trash in open barrels can also be a significant source of atmospheric dioxin emissions. It has been estimated that backyard trash burning by only two to forty households can generate as much dioxin as a municipal waste incinerator (Lemieux, Lutes, Abbott, & Aldous, 2000).

Although inhalation of dioxins in ambient air is a potential source of exposure, the major source of exposure to dioxins is through food consumption. Once dioxins are released to the environment, they resist chemical, physical, and biological degradation, and they can bioaccumulate in aquatic and terrestrial animals. More than 90% of the dioxin exposure in the general population is derived from background, low-level dioxin contamination in dairy products, meats, fish, eggs, and other foodstuffs (ATSDR, 1998).

Public health practice emphasizes prevention over treatment (see Chapter 26). This principle is especially relevant in the field of environmental health because preventing environmental contamination is easier and less costly than cleaning it up after it has occurred. Therefore both industrialized and developing countries should learn from the mistakes of the past and strive to manage and treat wastes in a manner that protects public health.

Summary

Human activities produce a huge volume and variety of waste materials that are regulated by federal, tribal, state, and local laws and regulations. Waste management strategies emphasize the importance of reducing, reusing, and recycling waste materials. When this is not possible, proper disposal and treatment of wastes is important. Selection of the best means for waste disposal or treatment requires consideration of factors such as technological feasibility, compliance with regulatory requirements, long-term effectiveness, community acceptance, and cost. Proper handling and disposal of wastes is necessary to prevent environmental contamination and potential adverse impacts on public health and ecological systems.

Key Terms

- agricultural waste

- Discarded material generated from the production of food and other products.

- animal waste

- Feces, urine, and spilled food from animals.

- construction debris

- Discarded material generated from construction and demolition of buildings and other facilities.

- deep well injection

- A disposal technology that forces treated or untreated liquid waste into geological formations that do not allow migration of contaminants into potential potable water aquifers.

- electronic waste (e-waste)

- Discarded electronic equipment such as computers, computer display monitors, televisions, DVD players, cell phones, and electronic games.

- hazardous waste

- Discarded material that is capable of harming human health or the environment.

- incineration

- The controlled combustion of discarded materials.

- industrial ecology

- The study of the physical, chemical, and biological interactions and interrelationships both within and between industrial systems and ecological systems.

- industrial waste

- Discarded material from industrial processes such as manufacturing, cleaning, recycling, and others.

- leachate

- A liquid generated by organic waste decomposition within a landfill or dump.

- life cycle analysis

- A technique for assessing the environmental and social (including health) impacts associated with all the stages of a product's life, from cradle to grave, and for designing and producing products that minimize waste and pollution at the end of their useful life.

- medical waste

- Discarded items that are generated from health care treatment and research and that have come into contact with body fluids or contain infectious agents.

- mining waste

- Discarded items generated as a result of the extraction of metal, coal, and oil from the Earth's crust.

- municipal solid waste

- Discarded everyday items generated from homes and businesses.

- radioactive waste

- Discarded materials that contain radioactive chemical elements.

- reduce, reuse, and recycle

- Primary goals of an ideal waste management strategy.

- sanitary landfill

- Land disposal areas specifically planned, constructed, and managed to prevent impact on human health and the environment.

- sewage sludge

- Concentrated solid material remaining after the treatment of waste water or sewage.

- solid waste

- Material (solid, liquid, or gas) that lacks value and is discarded.

- special waste

- A subcategory of solid waste that is designated by laws and regulations.

- waste management

- A multitier approach to prevent the generation of or to manage discarded materials so that human health and the environment are not impacted.

Discussion Questions

- What are the different approaches to solid waste management? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each approach?

- What are the different types of solid wastes, and how are they identified?

- How does the composition and management of solid waste vary around the world?

- How can you reduce the amount of waste you produce? Name each way and discuss it.

- Select one of the waste treatment or disposal technologies discussed in this chapter. How could this technology be effectively used in a solid waste management program? Specify the type of solid waste, and discuss how using the technology would protect the health of people and the environment.

- What are the ways in which people can be exposed to toxic substances in solid waste and hazardous waste?

- Research and summarize the management of municipal waste in your community. Where does the trash go? How much is produced per person? What steps is your community taking to reduce waste generation?

References

- Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. (2012). Low level lead exposure harms children: A renewed call for primary prevention. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (1998). Toxicological profile for dibenzo-p-dioxins (Update). Atlanta: Public Health Service, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2006). Health consultation: Exposure investigation report, air sampling for sulfur gases, Warren Township, Trumball County, Ohio. Atlanta: Public Health Service, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

- Burkholder, J., Libra, B., Weyer, P., Heathcote, S., Kolpin, D., Thorne, P. S., & Wichman, M. (2007). Impacts of waste from concentrated animal feeding operations on water quality. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115, 308–312.

- Caniato, M., Tudor, T., & Vaccari, M. (2015). International governance structures for health-care waste management: A systematic review of scientific literature. Journal of Environmental Management, 153, 93–107.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Got mice? Seal, trap, and clean up to control rodents. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/Features/Rodents

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015a). Infection prevention and control recommendations for hospitalized patients under investigation (PUIs) for Ebola virus disease (EVD) in U.S. hospitals. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/infection-prevention-and-control-recommendations.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015b). Interim guidance for environmental infection control in hospitals for Ebola virus. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/environmental-infection-control-in-hospitals.html

- Chartier, Y., Emmanuel, J., Pieper, U., Prüss, A., Rushbrook, P., Stringer, R.,…Zghondi, R. (2014). Safe management of wastes from health care activities (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Clark, C. S., Meyer, C. R., Balistreri, W. F., Gartside, P. S., Elia, V. J., Majeti, V. A., & Specker, B. (1982). An environmental health survey of drinking water contamination by leachate from a pesticide waste dump in Hardeman County, Tennessee. Archives of Environmental Health, 37(1), 9–18.

- Duan H., Miller T.R., Gregory J., & Kirchain R. (2013). Quantitative characterization of domestic and transboundary flows of used electronics: Analysis of generation, collection, and export in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Materials Systems Laboratory. Retrieved from http://www.step-initiative.org/files/step/_documents/MIT-NCER%20US%20Used%20Electronics%20Flows%20Report%20-%20December%202013.pdf

- Ehrenfeld, J., & Gertler, N. (1997). Industrial ecology in practice: The evolution of interdependence at Kalundborg. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 1, 67–79.

- Garner, A., & Keoleian, G. A. (1995). Industrial ecology: An introduction. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, National Pollution Prevention Center for Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.umich.edu/∼nppcpub/resources/compendia/INDEpdfs/INDEintro.pdf

- Gilchrist, M. J., Greko, C., Wallinga, D. B., Beran, G. W., Riley, D. G., & Thorne, P. S. (2007). The potential role of concentrated animal feeding operations in infectious disease epidemics and antibiotic resistance. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115, 313–316.

- Gulson, B. L., Davis J. J., Mizon K. J., Korsch M. J., Law A. J., & Howarth, D. (1994). Lead bioavailability in the environment of children: Blood lead levels in children can be elevated in a mining community. Archives of Environmental Health, 49(5), 326–331.

- Heederik, D., Sigsgaard, T., Thorne, P. S., Kline, J. N., Avery, R., Bønløkke, J. H.,…Merchant, J. A. (2007). Health effects of airborne exposures from concentrated animal feeding operations. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115, 298–302.

- Hill, S. (2012). Bad reaction: The toxicity of chemical-free claims. Retrieved from http://www.csicop.org/specialarticles/show/bad_reaction_the_toxicity_of_chemical-free_claims

- Hoornweg, D., & Bhada-Tata, P. (2012). What a waste: A global review of solid waste management (Urban Development Series Knowledge Papers). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Hossain, M. S., Santhanam, A., Nik Norulaini, N. A., & Omar, A. K. (2011). Clinical solid waste management practices and its impact on human health and environment—A review. Waste Management, 31(4), 754–766.

- Institute of Medicine. (2014). Research priorities to inform public health and medical practice for Ebola virus disease: Workshop in brief. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2014/Research-Priorities-to-Inform-Public-Health-and-Medical-Practice-for-Ebola-Virus-Disease-WIB.aspx

- Lemieux, P. M., Lutes, C. C., Abbott, J. A., & Aldous, K. M. (2000). Emissions of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans from the open burning of household waste in barrels. Environmental Science & Technology, 34, 377–384.

- Morin, M. (2014). Another Ebola challenge: Disposing of medical waste. Los Angeles Times, October 20. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/science/la-sci-ebola-waste-disposal-20141020-story.html

- Murgueytio, A. M., Evans, R. G., Sterling, D. A., Clardy, S. A., Shadel, B. N., & Clements, B. W. (1998). Relationship between lead mining and blood lead levels in children. Archives of Environmental Health, 53(6), 414–423.

- New York State Department of Health. (2014). High volume hydraulic fracturing for shale gas development. Albany: Author.

- A Notice by the Food and Drug Administration (Guidance for industry on new animal drugs and new animal drug combination products administered in or on medicated feed or drinking water of food-producing animals: Recommendations for drug sponsors for voluntarily aligning product use conditions with guidance for industry #209; Availability), 78 FR 75570 (2013).

- Orloff, K., & Falk, H. (2003). An international perspective on hazardous waste practices. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 206, 291–302.

- Osibanjo, O., & Nnorom, I. C. (2007). The challenge of electronic waste (e-waste) management in developing countries. Waste Management & Research, 25(6), 489–501.

- Ramesh Babu, B., Parande, A. K., & Ahmed Basha, C. (2007). Electrical and electronic waste: A global environmental problem. Waste Management & Research, 25(4), 307–318.

- Rubber Manufacturers Association. (2014). 2013 U.S. scrap tire management summary. Washington, DC: Author.

- A Rule by the Land Management Bureau (Oil and gas; Hydraulic fracturing on federal and Indian lands), 80 FR 16577 (2015).

- Sarraf, M., Stuer-Lauridsen, F., Dyoulgerov, M., Bloch, R., Wingfield, S., & Watkinson, R. (2010). The ship breaking and recycling industry in Bangladesh and Pakistan (Report No. 58275). Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPOPS/Publications/22816687/ShipBreakingReportDec2010.pdf

- Schmidt, C. W. (2002). e-Junk explosion. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(4), A188–194.

- Schmidt, C. W. (2006). Unfair trade: e-Waste in Africa. Environmental Health Perspectives, 114(4), A232–235.

- Silbergeld, E. K., Graham, J., & Price, L. B. (2008). Industrial food animal production, antimicrobial resistance, and human health. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 151–169.

- Silbergeld E. K., & Nachman, K. (2008). The environmental and public health risks associated with arsenical use in animal feeds. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1140, 346–357.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (1985). Report to Congress: Wastes from the extraction and beneficiation of metallic ores, phosphate rock, asbestos, overburden from uranium mining, and oil shale. Washington, DC: Author.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2008). Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990–2006. Retrieved from http://epa.gov/climatechange/emissions/downloads/08_ES.pdf

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2011). Electronics waste management in the United States through 2009. Washington, DC: Author.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2012a). Municipal solid waste generation, recycling, and disposal in the United States: Facts and figures for 2012. Washington, DC: Author.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2012b). The national biennial RCRA hazardous waste report (based on 2011 data). Washington, DC: Author.

- Wiedinmyer, C., Yokelson, R. J., & Gullett, B. K. (2014). Global emissions of trace gases, particulate matter, and hazardous air pollutants from open burning of domestic waste. Environmental Science and Technology, 48, 9523–9530.

- Wines, M. (2014). Waste from Ebola poses challenge to hospitals. New York Times, October 17.

- Zeller, T. (2008). Recycling: The big picture. National Geographic, January, pp. 82–87.

For Further Information

Books and Articles

- Carroll, C. (2008) High-tech trash: Will your discarded TV or computer end up in a ditch in Ghana? National Geographic, January, pp. 64–87.

- Chang, H. O. (2000). Hazardous and radioactive waste treatment technologies handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Gorner, I. K. (2003). Waste incineration: European state of the art and new developments. IFRF Combustion Journal, art. 200303.

- Gwin, P. (2014). The ship-breakers. National Geographic, May, pp. 80–88. Available at http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2014/05/shipbreakers/gwin-text where an extensive gallery of photos from Bangladesh is also available.

- Hickman, H. L. (1999). Principles of integrated solid waste management. Annapolis: American Academy of Environmental Engineers.

- Johnson, B. L. (1999). Impact of hazardous waste on human health: Hazard, health effects, equity, and communications issues. New York: Lewis.

- Lichtveld, M. Y., Rodenbeck S. E., & Lybarger J. A. (1992). The findings of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Medical Waste Tracking Act report. Environmental Health Perspectives, 98, 243–250.

- Manuel, J. S. (2003). Unbuilding for the environment. Environmental Health Perspectives, 111(16), A881–887.

- National Research Council. (1991). Environmental epidemiology: Public health and hazardous wastes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Rathje, W. L., & Murphy, C. (2001). Rubbish! The archaeology of garbage. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Schneider, A., & McCumber, D. (2004). An air that kills. New York: Putnam.

- Taylor, D. (1999). Talking trash: The economic and environmental issues of landfills. Environmental Health Perspectives, 108(7), A404–409.

- Tchobanoglous, G., & Kreith, F. (2002). Handbook of solid waste management (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Willis, B. C., Howie, M. M., & Williams, R. C. (2002). Public health reviews of hazardous waste thermal treatment technologies: A guidance manual for public health assessors. Atlanta: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Health Assessment and Consultation.

Nongovernmental Organizations

- Basel Action Network (BAN): www.ban.org. The BAN is an NGO based in Seattle that addresses global hazardous waste, with a focus on two waste streams: electronic waste (e-waste), and end-of-life ships.

- NGO Shipbreaking Platform: www.shipbreakingplatform.org. This is a Brussels-based coalition of environmental, human rights, and labor rights organizations working to prevent the dangerous pollution and unsafe working conditions caused when end-of-life ships containing toxic materials in their structures are freely traded in the global marketplace.

- StEP (solving the e-waste problem): www.step-initiative.org. Based in Bonn, Germany, and hosted by the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS), StEP focuses on reducing e-waste.

Agencies

Because federal government agencies frequently revise and update the information and data posted on their Web sites, specific Web pages are not provided. However, each of these home page Web sites has a search engine that will assist you in locating appropriate information.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: http://www.cdc.gov

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: http://www.epa.gov