Chapter 19

Food Systems, the Environment, and Public Health

Pamela Rhubart Berg, Leo Horrigan, and Roni Neff

Ms. Berg, Mr. Horrigan, and Dr. Neff report no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of this chapter. Dr. Nachman and Dr. Love report no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of their text boxes. Anna Engstrom reports no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of the tox box.

If the history of Homo sapiens were compressed into a single year, we would not have started farming until the evening of December 13. If the history of food production were compressed into a single year, we would not have introduced industrial agriculture, the mainstream food production system serving the United States today, until the morning of December 29. That's how new and different our modern food system is.

The modern food system is extremely large and permeates many aspects of our lives. In the United States, food production accounts for over half of our land, 16% of our energy, and 80% of consumptive water use (water lost to the environment by evaporation, crop transpiration, or incorporation into products). One in five private sector workers focuses on producing, processing, distributing, or selling our food, and food represents 13% of the U.S. gross domestic product (Neff, 2014). All that effort and expense produces a food supply that is more plentiful and costs less for consumers than it ever has.

In addition to these benefits, the way modern nations produce, process and distribute food has also created a wealth of challenges. In this chapter, we provide an overview of today's industrialized food system, focusing on threats to environmental public health, including contamination of soil, water, air and food, resource overuse, and food environments that promote unhealthy food choices. We then present a systems approach to the issue of food safety, both because of its importance to environmental health, and to illustrate the additional insight and problem-solving ability that this approach offers. Lastly, we briefly discuss some of the important policies that shape our food system's environmental health impacts. Rather than trying to be comprehensive (the system is too multifaceted for that), we give examples illustrating key concepts along the supply chain and in the policies shaping the system.

What Is the Food System?

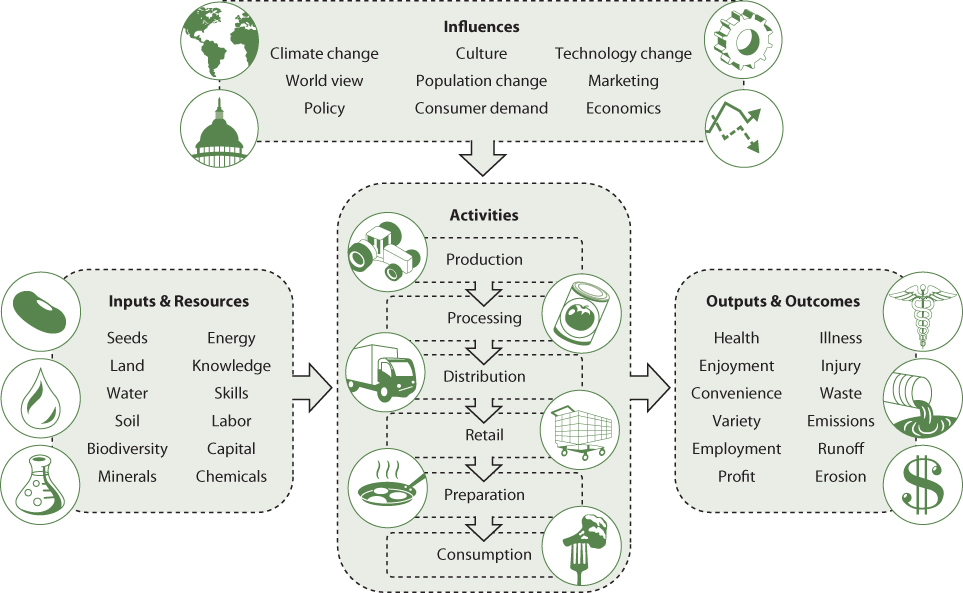

Food travels through the landscape via food supply chains of varying lengths, but all involve some form of production, distribution, consumption, and waste disposal; most also involve processing and sales (see Figure 19.1). Food supply chains are embedded within broader food systems, encompassing all the activities, resources, and inputs involved in the supply chain, as well as the outputs and outcomes of those processes; all the involved people, businesses, and organizations; and the related politics, policy, culture, marketing, and economics. What makes it a system rather than a collection of food-related components is its connective web of interacting relationships.

Figure 19.1 Selected Components of the Food System

Source: Brent Kim and Michael Milli, Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, 2015.

This figure shows examples of the flow of inputs and resources in food supply chains, influences that shape them, and resulting outputs and outcomes—many of which have direct and/or indirect impacts on public health. The arrows shown here represent only the prevailing directions of flow; in reality, relationships among food system components are often bidirectional or cyclical (e.g., manure and food waste may be composted and directed back into production), while many food system outcomes in turn influence supply chain activities and the use of inputs and resources. The dashed lines reflect the open nature of the system; each component operates not in isolation, but in relation to the others, and within the context of the social and biophysical environment.

The food system interacts with other systems. It brings in inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, energy, water, knowledge, and labor, and produces outputs, both positive and negative, including food, contamination, greenhouse gases (GHGs), and waste, with varying impacts on health, food security, and environmental health. The food system is shaped by environmental influences from outside as well, including climate change and land use, and social influences, such as population, policy, economics, culture, and marketing.

One important feature of a system is its dynamism; systems change constantly. This chapter describes many problems in today's food system, but there is also positive change afoot. Millions of consumers are seeking ways to make the food system—and the food they eat—healthier and more sustainable, while many businesses are recognizing that making changes can be profitable and can strengthen their businesses.

Food Production: Industrial Agriculture

Food production is the first stage in the food chain, and it has the greatest impact on environmental health. Food production includes producing crops, food animals (for meat, eggs, and dairy products), and both farmed and wild-caught seafood.

Most of our food is produced using industrial methods, which rely heavily on off-farm inputs such as fossil fuels, pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and large-scale machinery and which aim to produce the greatest possible yield with the lowest possible input cost. Agriculture was the last major sector of our economy to be industrialized, as some inherent difficulties in farming (e.g., unpredictable weather, crop failures, regional variations in climate) made it less amenable to industrialization.

Industrial agriculture requires much less labor than traditional methods that use human and animal power for seeding, plowing, and harvesting. Mechanization enabled each farmer to manage more land, so industrial agriculture made it possible to feed more people with fewer farmers and fewer farms. The United States had 7 million farms in 1935—when it had 127 million people. Today it has 316 million people but only 2 million farms (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [U.S. EPA], 2013).

Industrial Agriculture and Natural Resources

Agriculture relies on natural resources, such as soil, water, and biodiversity, and natural functions, such as pollination, decomposition, and predators that control pests (i.e., the ecosystem services described in Chapter 2). Unfortunately, some agricultural practices can damage natural resources and functions, as described in the next sections. We mention some specific implications for public health, but the overarching health threat here is that damaging and depleting these resources threatens our future food security.

Soil

Healthy soils contain thriving ecosystems—up to a billion bacteria in each teaspoon—and are resilient to drought. Once soil is eroded it can take a century or more to form an inch of new topsoil. Plowing, overgrazing, excessive fertilization (e.g., with manure from concentrated animal agriculture), and other agricultural practices degrade topsoil much faster than it can be replenished. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) says 25% of the world's land is severely degraded (Montgomery, 2007; FAO, 2011b).

Water

Agriculture is by far the world's biggest freshwater user globally, at 70% of all usage, with livestock products using far more water than most other agricultural products. Much water for agriculture is drawn from underground aquifers—some of which are nonrechargeable fossil aquifers. One of these, the Ogallala Aquifer, provides water for about one fourth of the irrigated acres in the United States, or more than 15 million acres. It has been estimated that as much as one third of the underground water extracted for agriculture is nonrenewable (Wada et al., 2010). Besides depleting water as a resource, agriculture is a leading source of pollution in U.S. water bodies. Pesticides and fertilizers can impair water quality, especially following high-intensity application, as can excessive plowing, overgrazing, or poor management of animal wastes.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity, or the existence of a variety of different species and organisms in an ecosystem, is important for agriculture. Today's agriculture has dramatically narrowed the range of plant and animal species produced in the United States and globally. Industrial agriculture threatens biodiversity in multiple additional ways. Most important is the use of monocultures, or large expanses of the same crop (Figure 19.2). About half of U.S. cropland is used to grow monocultures of genetically uniform corn and soybeans (U.S. EPA, 2009). While monocultures can create economies of scale, they are also vulnerable to pest invasions and plant diseases, because any pest or disease that prefers the monocultured crop as a food source will have an easier time becoming established.

Figure 19.2 Applying Herbicide to a North Carolina Cornfield

Source: North Carolina State Soil Science photostream, n.d.

This photograph demonstrates an agricultural monoculture, mechanization, and chemical inputs—three features of industrial agriculture.

Energy

Our industrialized food system is the first in human history to use more energy than it produces, requiring, by some estimates, about 7 to 10 calories of input energy for each calorie of food energy produced (Pimentel & Pimentel, 1996). Much labor in agriculture has been replaced by machinery that runs on fossil fuels, and the pesticides and fertilizers used in conventional agriculture are also made with fossil fuel inputs. There has been an increasing movement to incorporate energy efficiency and renewable energy into farming, including wind, solar, and biomass power produced on- and off-farm. Much long-distance transportation of food occurs on energy-efficient trains and boats, though substantial quantities travel on trucks as well.

Our dependence on fossil fuels to produce food raises public policy concerns and public health concerns, for at least four reasons (Neff, Parker, Kirschenmann, Tinch, & Lawrence, 2011): (1) Fossil fuels are limited resources. Some may be nearing their peak of supply, after which available supplies will decline. For some energy types, such as liquid gasoline and diesel, there are not yet cost-effective, environmentally sound replacements. (2) As stocks decline the price of energy will rise and become more volatile, leading to food price spikes, with profound food security and public health effects. (3) Burning more fossil fuels to grow our food means exacerbating climate change, which in turn severely threatens future food security (see Chapter 12). (4) Reliance on fossil fuels additionally contributes to air pollution, including ozone and particulate matter, which in turn can aggravate health problems such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (see Chapter 13).

Climate

Stable climate is also a “resource” for agriculture, but it is becoming less and less a reality as climate change unfolds. As explored in Chapter 12, climate change is expected increasingly to stress both crops and livestock, leading to declines in productivity in many parts of the world. Extreme weather events such as severe drought, floods, and strong storms are all expected to become more common and add to the difficulties of producing food. Many weed species benefit more than crop species when temperature, rainfall, and carbon dioxide concentrations increase. Warmer temperatures will also help pest insects shift or expand their ranges. Some agricultural pests will likely have more rapid life cycles that will make them harder for farmers to control. Rising sea levels are a concern for coastal agriculture because of saltwater intrusion into soils, groundwater, and river deltas that farmers depend on for irrigation. All of these phenomena, along with increasingly uncertain rainfall and temperature patterns, will lead to increased crop failures, undermining food security (Porter et al., 2014).

Besides being impacted by climate change, agriculture and food systems contribute to it. Food systems have been estimated to emit between 19% and 29% of global GHGs, and 80% to 86% of those emissions are attributed to agriculture (Vermeulen, Campbell, & Ingram, 2012).

Manufactured Agricultural Inputs

In addition to the resources described above, industrial farms use a variety of manufactured inputs to produce crops, many of which have potential environmental health impacts. Here we focus on three: pesticides, fertilizers, and genetically engineered seeds. In the next section we discuss additional inputs of concern used in food animal production.

Pesticides

Pests, such as insects and weeds, are often crop-specific, and thrive when a single crop is planted in a large area and/or over multiple years. Manufactured pesticides, however, have enabled farmers to plant monocultures without worrying about pest reproduction cycles. Applying the chemical takes care of the problem, at least in the short term. Unfortunately, though, pesticides have also created new problems, as explored in detail in Chapter 18. One problem is that heavy pesticide use has increasingly led to pesticide resistance (similar to drug resistance), in which the pesticide loses effectiveness against a pest. More than 500 pest species are now resistant to one or more pesticides (Whalon, Mota-Sanchez, & Hollingworth, 2008).

Pesticides create public health risks for farmers, farmworkers, and farm neighbors, primarily at the time when they are being applied. Pesticide residues on food also create public health risks for consumers. Exposure to pesticides can put farmers and farmworkers, in particular, at risk for acute effects, such as poisonings by organophosphates or carbamates, which can cause neurological and gastrointestinal problems (see Tox Boxes 18.1 and 18.2, in Chapter 18). Chronic health risks associated with pesticide exposure can include hormonal disruptions, reproductive and fetal development problems, asthma, and allergies. Some cancers have been linked to pesticides in animal studies and epidemiological studies (see Chapter 18).

Fertilizers

Traditionally, farms had a mix of animals and crops, with the animals' manure serving as fertilizer for the crops. Once science discovered a way to fix atmospheric nitrogen to produce synthetic fertilizers (the Haber-Bosch process), animal manure was no longer an essential fertilizer on the farm. Globally, the use of synthetic fertilizers took off, increasing by about 800% between 1960 and 2000 (Canfield, Glazer, & Falkowski, 2010).

Synthetic fertilizers helped spur the dramatic increases in crop yields known as the Green Revolution during the twentieth century (although high yields are possible with organic fertilizers as well). But there are downsides. Under current agricultural practices, crops take up only 30% to 50% of fertilizer nitrogen and about 45% of applied phosphorus (Tilman, Cassman, Matson, Naylor, & Polasky, 2002). Some of the excess runs off the land and becomes nutrient pollution in marine ecosystems, river deltas, and estuaries, a phenomenon known as eutrophication. This nutrient load stimulates the growth of algae. As the algae sink and decompose, the decomposition consumes oxygen in the water that is essential to healthy aquatic life. This has resulted in dead zones in hundreds of coastal locations worldwide (Diaz & Rosenberg, 2008). In addition to their ecological effects, some algae give rise to harmful algal blooms (HABs). Toxins from these blooms can cause acute neurotoxic disorders or chronic disease in humans. Many farmers today reduce fertilizer overuse and save money by using precision application systems that calibrate the quantities of fertilizer used based on soil needs.

Genetically Engineered Seeds

One of the most controversial technologies to be introduced to the industrial agriculture toolkit is genetic engineering, resulting in genetically modified organisms (GMOs), including food crops. GM corn and soybean seeds only came on the market in 1996, but they already account for the vast majority of U.S. plantings of those crops, and now cover almost half of U.S. cropland (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2014). These crops have genes for herbicide tolerance or genes that allow the plants to produce their own insecticide, or both. While the seeds can be costly, they have increased yields in some cases and saved U.S. farmers time and money, though as described below, this may change. Many consumers have focused on concerns about safety, and have demanded labeling to identify products with GM ingredients. Assessments in the United States (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2102) and Europe (European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, 2010) and by the United Nations (World Health Organization, 2005) have not found significant evidence that these crops pose risk, though monitoring and research are ongoing, and some have called for more precautionary approaches in the short term (Hilbeck et al., 2015). Social concerns are also significant, as GMO technology is controlled by private firms that obligate farmers to purchase their seeds each year. Moreover, given the size of their investment, some of these companies aggressively defend their intellectual property rights in ways that impede independent research (Scientific American Editors, 2009).

From an environmental health standpoint, the impacts of the insecticides and herbicides used with GM crops are more pressing concerns. Herbicide-tolerant crops led to use of an additional 527 million pounds of the herbicide glyphosate in the United States between 1996 and 2011 (Benbrook, 2012). The World Health Organization (WHO) has designated glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup (the most common glyphosate product), a probable human carcinogen (Guyton et al., 2015), and glyphosate has also been linked to birth defects in some studies (Paganelli, Gnazzo, Acosta, López, & Carrasco, 2010; Antoniou et al., 2012).

Extensive use of glyphosate has led to the evolution of weeds that are resistant to the chemical. This cycle may continue, requiring increasingly toxic products. On the insecticide front, use decreased by a combined 123 million pounds from 1996 to 2011, although target insects are showing increasing resistance to the pesticide known as Bt (a natural toxin produced by the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis and exuded by “Bt crops”) (Benbrook, 2012).

Industrial Food Animal Production

The more than 9 billion food animals slaughtered in the United States each year exert an outsized impact on the environment and environmental health. Nearly all of the meat, milk, and eggs consumed in the United States are produced in a system known as industrial food animal production (IFAP), which raises animals in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), a legally defined term referring to facilities that confine animals, above certain numbers, without grass or other vegetation in the confinement area. The animals are raised under protocols created by integrators, companies that sign contracts with the CAFO operators. The contracts specify production methods but assign CAFO operators responsibility for managing the animals' waste. IFAP animals eat manufactured feeds containing a substantial portion of the corn and soybeans raised in the United States. CAFO animals' feed also routinely includes antimicrobials (in chicken and hog operations, although some major companies report plans to phase them out) and can also include rendered animal products and animal waste (Sapkota, Lefferts, McKenzie, & Walker, 2007). Despite the many limitations described below, the IFAP model has been exported, in particular to China, India, and Brazil.

Public Health Concerns

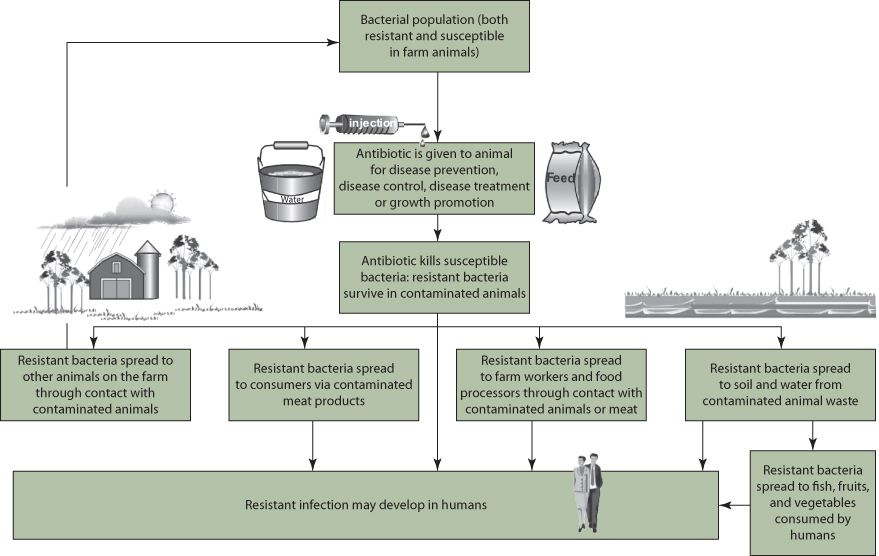

One of the major concerns about CAFOs is their routine use of antibiotics, which are fed to food animals in low doses that do not kill all of the target bacteria and so foster the development of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. These low doses are used to promote faster growth and compensate for the immune-compromising conditions in which they live. IFAP accounts for about 80% of the antibiotics used in the United States, and uses many of the same types of antibiotics that are used in human medicine (Collignon, Powers, Chiller, Aidara-Kane, & Aarestrup, 2009). This practice contributes to the unfolding crisis of antibiotic resistance, whereby human diseases once cured easily with antibiotics have become more difficult—and sometimes impossible—to treat. Text Box 19.1 describes policy approaches to addressing agricultural antibiotic use.

Animal waste can contain disease-causing organisms such as certain Salmonella, Listeria, and E. coli species. As a result, if it has not been composted for a sufficient period of time, CAFO manure used to fertilize food crops can contaminate fresh produce and lead to outbreaks of foodborne illness, as discussed below (Graham & Nachman, 2010). Manure can also contain antimicrobials, 25% to 75% of which are estimated to be excreted unaltered (Kummerer, 2004), and heavy metals. Cattle are routinely fed large amounts of grain—which is not part of their natural diet—and this alters their digestive tracts in a way that promotes a disease-causing strain of E. coli.

Pathogens from animal waste, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria, spread from the farm into the community primarily through occupational exposures, environmental contamination, and contact with contaminated food products (You & Silbergeld, 2014) (also see Figure 19.3).

Figure 19.3 Potential Pathways for the Spread of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria from Animals to Humans

Note: This figure is not intended to represent the full complexity of resistance transmission. For example, antibiotic-resistant bacteria can also be transferred from humans to animals.

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office [U.S. GAO], 2011, p. 6.

Numerous noncommunicable ailments have also been documented among people who live near industrial swine facilities and who are exposed to these facilities' air and water emissions. These conditions include elevated rates of depression, stress, fatigue, headaches, sore throats, nausea, and respiratory problems (Donham, 2010). Because poor communities and communities and communities of color are disproportionately located near CAFOs, these risks are environmental justice concerns (Nicole, 2013).

Waste Management

Swine, poultry, and cattle raised in U.S. CAFOs produce more than 300 million tons of dry waste each year (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2005), or more than forty times the amount of human solid waste processed by U.S. wastewater treatment plants (Graham & Nachman, 2010). In stark contrast to human biosolids, for which treatment must meet regulatory requirements for removing pathogens and chemical contaminants, there is no requirement to treat animal manure before releasing it into the environment (by spraying it on crop fields, for example) (Graham & Nachman, 2010). Separating food animals from the land has turned an agricultural asset—animal manure deposited directly on pastureland or used on a farm's nearby cropland as fertilizer—into a waste management problem. There are typically many CAFOs clustered in relatively small areas, intensifying the waste management challenge. For example, North Carolina's Duplin County, with a human population of 60,000, is raising 2.3 million hogs at any one time, or 38 hogs per resident (Agriculture and Community Development Services, n.d.). IFAP animal waste is commonly stored in large manure cesspits, as shown in Figure 19.4.

Figure 19.4 Manure Cesspit Outside Hog CAFO in Duplin County, North Carolina

Source: Horrigan & Moore, 2010.

When manure is applied at a greater rate than can be absorbed by the land, rainfall carries off the excess, which can then contaminate surface waters and create dead zones, or contaminate the air and also the shallow aquifers on which most rural residents depend for drinking water.

Sustainable Agriculture

This is a time of enormous interest in the food system and enormous efforts to bring about food system change. Consumers increasingly want to learn about their food, know where it came from, and trust its quality. According to a recent poll, 66% of Americans have thought about the sustainability of their food and beverages in the past year, 39% have shopped at farmers' markets, 26% have bought organic products (Text Box 19.2), and 22% have grown their own food (International Food Information Center Foundation, 2012). College students around the country have successfully called for changes to campus food, through participation in the Real Food Challenge (www.realfoodchallenge.org).

What are the features of a healthy, sustainable, and resilient food system? In short:

- A sustainable food system has the capacity to keep producing food into the future.

- A resilient food system has the capacity to bounce back after disturbances.

- A healthy food system supports the short- and long-term health of the population. It is, as defined by four major professional associations, “health-promoting, sustainable, resilient, diverse, fair, economically balanced, and transparent” (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, American Nurses Association, American Planning Association, and American Public Health Association, 2012).

Changes in food production may be categorized into two types. First, most conventional farms have now adopted at least some practices that make their operations more sustainable (and generally save money). Second, many farms have adopted agroecological practices, meaning they try to mimic natural systems as they design and manage their agricultural systems. As an example of the first, conservation tillage, to reduce soil loss and save gasoline, has become the norm rather than the exception in U.S. agriculture. It involves leaving residue from the previous crop on the ground rather than tilling the soil between crops. Other increasingly common methods are high-efficiency irrigation systems to conserve water; use of precision technology in fertilizer application, and use of cover crops for weed suppression, soil conservation, and soil enhancement, among other benefits. Another increasingly widespread method is integrated pest management (IPM) (described in Chapter 18), which emphasizes using biological controls for pests (e.g., introducing natural predators or creating habitat for them) and other nontoxic controls before applying least-toxic chemical pesticides only as a last resort (National Research Council, 2010).

All these changes in industrial agriculture represent incremental progress. But creating a more sustainable agriculture goes beyond substituting one farming practice for another; it focuses on mimicking natural systems. A 2013 United Nations report on the state of agriculture called for a “rapid and significant shift from conventional, monoculture-based and high external-input-dependent industrial production towards mosaics of sustainable, regenerative production systems” (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2013).

Good soil is seen by many as the foundation of healthy agricultural systems. One of the central goals of sustainable agriculture is to maintain and build soil health by adding organic matter and using cover crops, among other techniques. Biologically healthy soil improves retention of moisture and nutrients, provides substantial drought resistance, and sequesters more carbon than other soils. Soil holds about 80% of all the carbon found in terrestrial ecosystems (Ontl & Schulte, 2012).

Japanese farmer Takao Furuno (2001) created a well-known example of a farming system that mimics natural systems. His approach incorporates ducks into rice paddies to eat weeds and insects while also adding fertility to the water with their waste (see Figure 19.5). This reduces input costs for pesticides and fertilizers while creating additional revenue streams from duck meat and duck eggs. Furuno then added fish into his paddies to provide even more revenue—a practice that rice farmers had abandoned because the insecticides used in industrial rice farming would kill their fish. His system was shown to yield 20% more rice than a traditional rice production system (Hossain, Sugimoto, Ahmed, & Islam, 2005). Through Furuno's promotional efforts and those of his institutional partners, his method has spread to more than 75,000 farmers across eleven Asian countries and also to Cuba (Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship and the World Economic Forum, 2001).

Figure 19.5 Ducks in One of Takao Furuno's Rice Paddies in Japan

Source: Mamemachi, n.d.

Food Consumption and Food Environments

The penultimate stage of the food chain is food consumption. It may not seem intuitive that food consumption is an environmental health issue, but daily choices about what we will eat and not eat are strongly affected by our food environment. This term refers to all aspects of our surroundings that may influence our diets, including both the built environment in and around our homes, workplaces, and schools (as discussed in Chapter 15) and the marketing and social environments that surround us less tangibly but with no less impact. Food environments are shaped by numerous factors, including government policy, advertising, cultural norms, and what food outlets are available to consumers (supermarkets, corner stores, restaurants, etc.) (Truant & Neff, 2014).

Communities with poor access to affordable, healthy food are sometimes termed food deserts (or, to the extent they are awash in less healthy food, food swamps). These characterizations have been effective in policy advocacy, although some dislike them, particularly because of their emphasis on a community's limitations.

Evidence is mixed regarding the extent to which healthy food access affects food choices and health (although there is no question that the inconvenience of low access to healthy food makes it an environmental justice issue as it disproportionately affects low-income communities). As discussed in Chapters 9 and 15, physical proximity to markets is only one factor affecting food choices, and its impact is balanced against other factors such as perceived proximity, available transportation options, variations in food prices, and the many factors that shape food demand. While research results are mixed, some studies suggest that increased access to supermarkets is associated with healthier diet quality, lower prevalence of overweight and obesity, and greater consumption of fruits and vegetables, whereas increased access to convenience stores is associated with increased risk of obesity (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins, 2009; Lucan, 2015). At the very small scale—say, the experience of a child moving down a cafeteria line—there is evidence that the presentation and positioning of food can affect food choices—a phenomenon that is explored in Chapter 9.

The final step in the food chain is the disposal of waste. As described in Chapter 17, waste is managed in many ways, from landfilling to incineration, and in some cases through conversion to biofuels. Waste occurs at every stage of the food chain, and has important environmental implications. These are explored in Text Box 19.3.

Food Safety and Environmental Health: A Systems Perspective

Disease-causing bacteria, viruses, chemicals, and other threats to health can enter the food supply at many points along the supply chain. Although the major focus of food safety has been the reduction of health risks associated with foodborne pathogens (bacteria, parasites, and viruses), food safety can also be compromised by pesticides and other chemicals, as well as physical hazards such as glass.

Contaminated food can pose serious risks to those who are exposed, causing acute nausea, diarrhea, fever, chronic illness, and in some cases, death. Vulnerable populations—the very young or elderly, those with weakened immune systems, and workers who grow, process and distribute food—are at increased risk. The CDC estimates that one in six Americans suffers a foodborne illness each year, leading to approximately 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths (CDC, 2011).

Poor surveillance in many countries makes it difficult to estimate the global burden, but the World Health Organization estimates there are over 580 million cases of illness and 351,000 associated deaths annually from contaminated food and water (WHO, 2015). Foodborne illness is likely greater where sanitation is substandard and malnutrition increases susceptibility to the health effects of consuming unsafe food, particularly among children, who bear the brunt of foodborne illness and death. Many low-income countries lack infrastructure, such as refrigeration along the supply chain, and have limited capacity for basic environmental and public health services, such as water treatment. Food safety, however, remains a public health challenge even in industrialized countries, despite advances in risk identification, assessment, and management.

As the scale of the food chain grows, so does the number of people at risk from a single outbreak. Rapid changes in agricultural practices and food processing, new biotechnology, and a growing reliance on a globalized food system introduce new hazards and challenges for risk identification and traceability (see Text Box 19.4). Processed food items can include dozens of ingredients from multiple countries. A typical fast food cheeseburger can contain more than fifty ingredients that come from virtually every continent (Hueston & McLeoad, 2012).

The following sections of this chapter briefly describe the major categories of contaminants, discuss regulatory and other approaches to reduce the public health burden of foodborne illness, and highlight several challenges to food safety efforts in our increasingly complex supply chain.

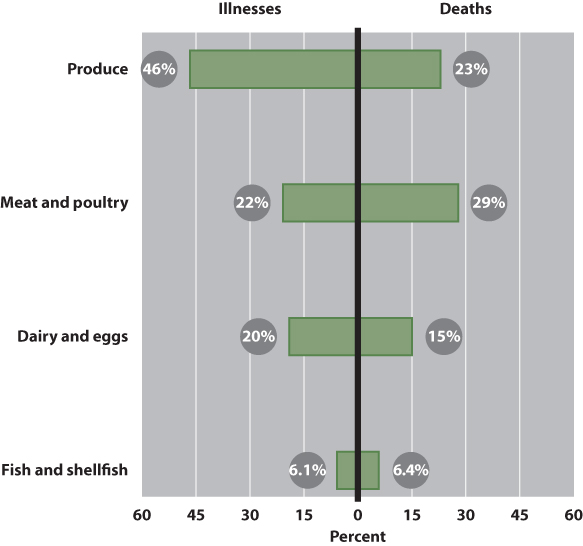

Biological Pathogens in the Supply Chain

Estimates suggest that in the United States, only fourteen pathogens account for 95% of illnesses and hospitalizations and 98% of deaths from foodborne pathogens (Scallan et al., 2011), and that these illnesses cost an estimated $14 billion each year (Batz, Hoffmann, & Morris, 2012). The public health threat of foodborne illness is growing as pathogens are linked to new food sources and new pathogens are discovered, and the rise of antibiotic resistance can make foodborne illnesses increasingly difficult to treat. Salmonella, Toxoplasma gondii, Listeria monocytogenes, and Campylobacter pathogens and noroviruses are the most dangerous of the pathogens responsible for serious illnesses and hospitalizations and for deaths (Batz et al., 2012). In a CDC analysis of foodborne illness data, produce accounted for nearly half of illnesses, most often caused by noroviruses, while meat and poultry were the primary sources of fatal infections, with most due to salmonella and listeria (Painter et al., 2013) (see Figure 19.7). Although chronic illness or death is possible, foodborne pathogens most often result in severe gastrointestinal symptoms that run their course and abate.

Figure 19.7 Contribution of Different Food Categories to Estimated Domestically Acquired Illness and Death, United States, 1998–2008

Note: Chart does not show 5% of illnesses and 2% of deaths attributable to other commodities. In addition, 1% of illnesses and 25% of deaths were not attributed to commodities; these were caused by pathogens not included in the outbreak database, mainly Toxoplasma and Vibrio vulnificus.

Source: CDC, 2013b.

One of the primary pathways of exposure to pathogens such as salmonella and E. coli is handling or eating food contaminated by animal waste. This can occur in several ways. First, livestock and pests such as insects and rodents carry disease-causing microbes. The pathogens from the waste can contaminate food via irrigation water, tainted equipment, and worker handling. Pathogens can also be introduced when food handlers have illnesses. Sometimes the meat itself may carry the microbes, while in many more cases small nicks to the digestive tract during meat processing can introduce fecal matter onto meat surfaces. A small amount of fecal matter or tainted meat can contaminate a large batch of processed meat, such as ground beef or turkey. In 2014, 18.7 million pounds of meat and poultry were recalled, including 13.2 million pounds of beef and beef products (Center for Science in the Public Interest, 2014; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service, 2015).

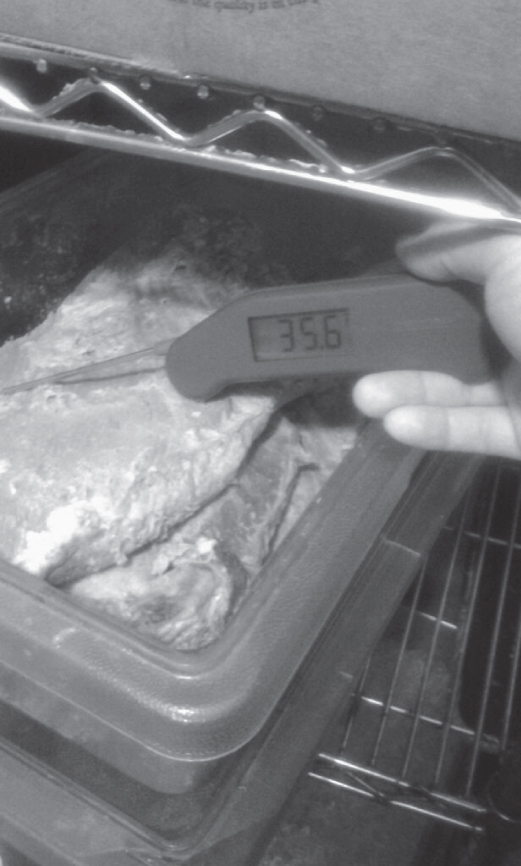

Once a pathogen enters the food system, it is possible to prevent its growth through proper handling techniques and avoidance of cross-contamination. Time and temperature controls are particularly important for potentially hazardous food (PHF), including meat, seafood, dairy, eggs, cooked starches, melons, and sprouts (see Figure 19.8). Many of the pathogens that cause foodborne illness thrive at temperatures between 40° and 140°F and can double in number every twenty minutes (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service [USDA, FSIS], 2013a). Of course, not all food is contaminated; when it is, refrigeration and freezing can slow or stop reproduction, but will not necessarily destroy bacteria, leaving proper cooking as the primary strategy for consumers to use to prevent foodborne illnesses.

Figure 19.8 A Health Inspector Tests the Temperature of Refrigerated Meat at a Restaurant

Source: Photo by Christopher Berg, REHS.

Inspections of food service establishments continue to be an important function of local health departments.

In a CDC analysis of foodborne outbreaks that occurred between 1998 and 2008, a majority of cases (60%) were associated with food prepared in a restaurant or deli (Gould et al., 2013) (Figure 19.9). Lack of paid sick days and employer-provided safety equipment, pressures to cut corners, inadequate training, and high turnover in the low-wage jobs typical across the food supply chain, particularly in the food service industry, compromise safety for workers and, ultimately, consumers.

Figure 19.9 A 1993 Outbreak Caused by E. Coli 0157 in Undercooked Beef at Jack in the Box Restaurants Sickened 732 People and Killed 4 Children

Source: Hathorn, 2012.

This outbreak prompted the creation of the CDC's PulseNet Pathogen Detection and Tracking System.

Chemicals in the Food Supply

While the reduction of exposure to foodborne pathogens tends to be the focus of food safety initiatives, food can also contain harmful chemicals. Synthetic and naturally occurring chemicals can contaminate foods intentionally or unintentionally during production (pesticides, dioxins [Tox Box 19.1], PCBs, arsenic), processing (monosodium glutamate, aspartame, dyes), packaging (phthalates, bisphenols, including BPA), and preparation (acrylamide, furans) (Jackson, 2009).

In some cases chemicals are used improperly or added unintentionally. In 2008, over 300,000 babies in China fell ill, 54,000 were hospitalized, and at least 6 died after a Chinese manufacturer added melamine, an industrial chemical used to make flame-retardant resin and plastics, to baby formula and milk powder to increase its apparent protein content (Gossner et al., 2009). In 2013, at least 23 children in the Indian state of Bihar died within hours of consuming a free lunch prepared using cooking oil stored in containers that had once held a dangerous and widely banned pesticide (United Nations News Centre, 2013).

Many of the most commonly used pesticides in the past, and some still in use in lower income countries, are now classified as persistent organic pollutants (POPs). POPs have been associated with reproductive, developmental, behavioral, neurological, immunological, and endocrine effects, including type 2 diabetes. Despite international bans decades ago, POPs such as DDT, dioxin, and PCBs continue to bioaccumulate and remain virtually unavoidable in the global food chain today. (Another group of toxic contaminants, mycotoxins, is addressed in Text Box 19.5 and Figure 19.10.)

Figure 19.10 An Example of Improper Grain Storage

Source: A. Qadri; Associated Press, 2012.

Properly drying and storing grains to control moisture is one of the most effective methods of preventing dangerous molds and mycotoxins.

Addressing Food Safety Threats

The food safety system is a moving target, complicated by emerging and newly identified threats and an increasingly globalized food supply chain. Even though a completely safe food supply is an unrealistic goal, most foodborne illnesses are preventable. Food safety illustrates the benefits of a systems perspective that goes beyond a simple “wash your countertops” approach. In many cases, preventive actions early in the supply chain to protect human, animal, and ecosystem health yield the co-benefits of safer food. Reducing density in livestock operations, reducing line speeds in processing plants, and providing proper safety equipment to workers are examples of steps that can yield downstream effects for food safety and public health.

Just as the risk factors for foodborne illness are diverse and multilevel, so too are the interventions to address it, which include the following:

- Regulations and standards at the international, federal, state, and local levels

- Inspections of food products, processing plants, restaurants, and retailers (see Figure 19.8)

- Training of food system workers, technical assistance in achieving compliance with regulations, and policy and workplace interventions to provide workers with paid sick days and other needed supports

- Tracking illnesses through physician reporting and other epidemiologic surveillance strategies

- Investigations following outbreaks to identify sources and contact those who may have been exposed

- Food recalls, both voluntary and mandated

- Public education to increase use of routine safety measures

- Threats of negative publicity and legal action

- Research to improve all of these strategies

The trend in food safety efforts is toward risk assessment and management tools, guidelines, and programs to reduce contamination risk during production, processing, and retail. Prerequisite programs (PRPs) generally serve as a foundation for overall quality and hygiene. These include good agricultural practices (GAPs), good manufacturing processes (GMPs), good hygienic practices (GHPs), and good storage practices (GSPs). When PRPs are in place and working effectively, Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) systems can further enhance risk reduction. HACCP was developed by NASA and Pillsbury to produce food guaranteed to be safe for consumption by astronauts during the early days of the U.S. space program (Hulebak & Schlosser, 2002). This stepwise approach to primary prevention (Table 19.1) aims to identify and address potential risks to food safety before they can occur and has become a standard in modern food safety approaches. HACCP systems are now required for manufacturers of meat, poultry, seafood, and juice products and are also employed in some segments of the food service industry.

Table 19.1 HACCP Principles

| 1. | Conduct a hazard analysis. |

| 2. | Identify critical control points (CCPs) in the process. |

| 3. | Establish critical limits for each CCP. |

| 4. | Establish CCP monitoring procedures. |

| 5. | Establish corrective actions for instances when CCP monitoring reveals deviations. |

| 6. | Keep records. |

| 7. | Establish procedures to verify that HACCP is functioning properly. |

Food Safety Regulations

The first attempts at food safety regulation in the United States date back to the early decades of the twentieth century in response to the public's outcry over Upton Sinclair's book The Jungle (Burkett, 2012). In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act established what is now the FDA, while the Meat Inspection Act established the USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service. On this foundation, today's food safety framework developed as a patchwork of laws and regulations that were put in place largely in reaction to deadly foodborne disease outbreaks (Table 19.2). Laws were enacted over the latter part of the twentieth century increasing the USDA's power to regulate and inspect meat products. The FDA's authority over the remaining 80% of the food supply was recently strengthened under the 2010 Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). The FSMA gave the FDA expanded recall capabilities, authority to mandate HACCP systems more broadly across the food manufacturing sector, and enhanced oversight of food processing and imported food (Taylor, 2011).

Table 19.2 Jurisdiction over Food Safety in the United States

| FDA | Oversees the safety of approximately 80% of domestic and imported food, including seafood, dairy, produce, eggs in the shell, and bottled water. Monitors for the safety of animal feed. Supports state and local efforts through the Model Food Code, guidance, training and technical assistance, and evaluation services. |

| USDA | Oversees the safety of meat, poultry, and some egg products, in settings including processing plants, retail outlets, and restaurants. Inspects meat processing plants, which can be carried out in conjunction with state programs and certification of imported meat products. Establishes quality and marketing grades for many foods and oversees the national organic labeling standards (see Text Box 19.2). |

| CDC | Monitors and investigates foodborne illness outbreaks, often in coordination with state and local health departments. Coordinates FoodNet surveillance (www.cdc.gov/foodnet) and data analysis of 9 foodborne pathogens. Oversees DNA tracing of pathogens through PulseNet, a network of laboratories in each state. |

| EPA | Monitors drinking water and regulates toxic chemicals, such as pesticides, through the Food Quality Protection Act. |

| State and local agencies and health departments | Inspect restaurants, grocery stores, day-care facilities, hospitals, schools, and some food manufacturing plants, and investigate complaints. Train food service workers. Conduct outreach to food service establishments and consumers during recalls and foodborne outbreaks. Coordinate surveillance and responses to outbreaks with the CDC. |

One of the criticisms of the U.S. food safety regulatory framework is the almost comical fragmentation of authority across different agencies. Although the FDA and USDA continue to have primary jurisdiction (Figure 19.11), authority over the food safety measures listed earlier is dispersed across a total of fifteen agencies and hundreds of state and local health departments, involving twenty-eight House and Senate committees and three dozen food safety–related statutes. For example, the USDA regulates egg-laying facilities and processed egg products, but the FDA has authority over the grain fed to laying hens and the eggs themselves while still in the shell. Responsibility for frozen pizza depends on the pizza topping: the FDA for cheese, the USDA for pepperoni (Sheingate, 2014). The USDA inspects sausage meat, but the casings that enclose the meat are the FDA's jurisdiction because they have no nutritional value (Goetz, 2010); or that sausage may be covered under state or local authority if it is made and sold in the same location (USDA, FSIS, 2013b). This overlapping of jurisdiction can complicate and hinder efforts to protect the food supply.

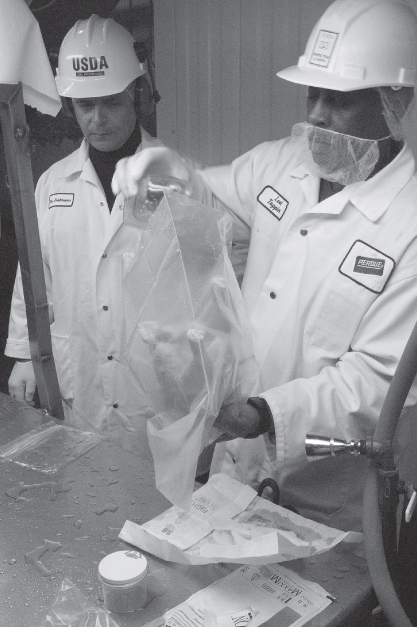

Figure 19.11 A U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service Inspector at a Poultry Processing Facility in Accomac, Virginia, Testing for Cleanliness and the Avian Influenza (AI) Virus

Source: USDA, 2006.

The Codex Alimentarius is a set of internationally recognized standards and procedures for food safety and fair trading practices in the increasingly global food trade. Codex member countries cover 99% of the global population and the standards are managed by a commission operating within the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization (Codex Alimentarius, 2015). The Codex has far-reaching implications, often serving as the basis for national food safety legislation in countries without national food safety programs. World Trade Organization members may cite the Codex in challenging food safety and quality measures that are stricter than Codex standards.

Gaps and Challenges in Food Safety Protection

The U.S. Government Accountability Office is highly critical of the fragmentation and inefficiency of government oversight over food safety, although it acknowledges that improvements have been made under the FSMA (U.S. GAO, 2004, 2014). Its recommendations include a broad overhaul of the food safety framework to create more centralized leadership and establish an institutionalized collaboration among agencies with a government-wide food safety plan. Such a broad approach to prevention is highly consistent with public health principles (see Chapter 26). Importantly, to be effective, new food safety programs must be based on a clear understanding of actual conditions contributing to risk and on data-driven priority setting. For example, food safety policy affecting workers commonly focuses on training, but many food service workers say they know what to do but are stymied by social and structural barriers to using hygienic practices, including a lack of paid sick days and intense pressures to perform quickly in often-insecure, low-paying jobs (Clayton, Smith, Neff, Pollack, & Ensminger, 2015).

With an increasing push for harmonization of food safety regulations and practices in the United States and worldwide, there is debate about the extent to which policies should be tailored according to risk, based on such factors as food type, farm size or a company's performance record. Broadly applying stringent food safety policies, such as HACCP requirements, would likely simplify global trade for the largest food manufacturers and result in more universal use of certain practices. It could, however, pose a significant burden for small-scale farmers, processors, or retailers who do not benefit from the same economies of scale, and who operate largely outside the lengthy industrial food chain (such as the farmers' market in Figure 15.7, in Chapter 15).The new FSMA rules will likely include some exemptions and considerations for small-scale farmers who sell direct to customers.

Making Change: Food System Policy

It is clear that the way we grow, process, distribute, and choose food can have substantial effects on our health, the health of the environment, and long-term food security. There are many ways to shift toward a healthier food system, including encouraging entrepreneurial activities, creating demand for alternative products, building infrastructure, supporting research and development on improved agricultural methods, incentivizing production and consumption of healthier foods and other desirable activities, and restricting or disincentivizing unwanted activities. Additionally, consumers impact the food system with every purchase they make, every bite they eat, and every vote they cast.

Consumer demand has had major impacts on the food system, particularly in recent years with people's increasing awareness and concern about how food gets from farm to plate. It has been argued, however, that far greater potential for improving public health outcomes would come from addressing socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, and improving food environments so that individuals' “default” food choices are healthier (Story, Kaphingst, Robinson-O'Brien, & Glanz, 2008). Well-crafted policies can address the negative impacts of food production practices, increase the availability of healthy foods, shift demand, and more. In this section we explore the roles specific policies have played in shaping our current food system and the importance—and challenge—of using policy as a tool to create food system change.

In the United States, food system policy is dispersed among thousands of laws, regulations, and agreements across many different agencies at the local, state, federal, and international levels (Table 19.3). While food policies originally focused on correct labeling and the safety of products for consumers, farm policies have historically been based on the economic needs of farmers, the need for a steady supply of food, and maintaining the soil and water resources for food production (Muller, Tagtow, Roberts, & Macdougall, 2009).

Table 19.3 Some of the Many Policies Shaping the U.S. Food System

| Federal levels | State and local levels |

| Farm Bill Trade policy (domestic, international) Food assistance (domestic, international) Child Nutrition Act Food safety policies (including the Food Safety Modernization Act) Regulations on food labeling and marketing Dietary guidelines Procurement policies Tax policy Regulation of feed additives Regulation of biotechnology Labor standards Clean Water Act Clean Air Act Occupational safety and health standards and regulations |

Food safety policies, such as restaurant inspections and training Zoning and licensing requirements Land-use policies and planning Economic development policies and planning Infrastructure investments Nuisance laws Tax policy and incentives Limits on industry access to schools Food procurement Food policy councils Limits on specific additives |

Note: These categorizations are not absolute; for example, some states do engage in policymaking in areas listed in the federal category.

Some agencies juggle competing interests as they make policy. The USDA, for example, has a leading role in developing the national nutrition guidelines that recommend eating more fruits and vegetables, but at the same time it supports the corn-based agricultural system that contributes to the ubiquity and relatively low retail price of meat and high-sugar, processed foods.

One of the largest policies that influences the operation of our food system is the federal Farm Bill, multiyear “omnibus” legislation with provisions for farm commodity supports, land conservation, nutrition assistance programs, and many other large and small government programs affecting agriculture and food. The 2014 Farm Bill is projected to cost approximately $490 billion in mandatory spending over five years, with programs and initiatives under the nutrition title, which includes funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), receiving about 80% of those funds (Monke, 2014). Approximately $65 billion is designated to support commodity crops such as corn and soybeans, enabling purchasers to buy them at prices below the cost of production for uses including animal feed, biofuels, and processed food. Relatively little funding goes to support so-called specialty crops, including the fruits and vegetables that are supposed to make up the majority of a healthy diet, although the portion is growing. Funds to encourage farm use of conservation and sustainable practices are also relatively small but growing.

Given its size and impact, the Farm Bill would seem a logical platform for promoting public health, and indeed, public health professionals have advocated changes in recent Farm Bills. But gridlock in Congress has caused many advocates to grow frustrated with federal policy and to turn their focus to opportunities at the state and local levels. Often more workable, state and local policy arenas can also serve as laboratories for piloting new programs that can be scaled up if appropriate. Certain policy approaches may also make sense on a state or local scale yet not be suitable for a national program. Food policy councils bring together stakeholders, including engaged consumers, to address many of the food system–related policy decisions that largely take place at a local level, such as decisions on land use and zoning, on food safety regulations for such sources as food trucks and mobile vendors, and on rules governing school food sourcing. Between 2000 and 2014, the number of food policy councils in North America grew from 16 to 263 (Scherb, Palmer, Frattaroli, & Pollack, 2012).

The nature of agriculture and the infrastructure involved in the industrialized food system make reform slow, particularly at the national and international levels. Crafting effective food system policy is difficult because of the complexity of the interactions among the various parts, stakeholder interests, and the potential for far-ranging consequences. Too often, potential solutions to complex problems challenge conventional wisdom, assumptions, and beliefs. For example, despite shorter transport distances, locally produced food may have higher levels of embedded transportation-related energy than food from the conventional food supply chain does, due to the different vehicle types used. Similarly, in terms of food-related greenhouse gas emissions, forgoing dairy and meat one day per week would reduce food-related greenhouse gas emissions more than buying only locally grown foods (Weber & Matthews, 2008). Despite these realities, local food systems have many social, economic, and community benefits.

Summary

The food system nourishes us and provides livelihoods for a significant portion of the global population. But the modern industrialized food system wastes or undermines many of the resources on which it depends—water, energy, soil, a stable climate, and biodiversity. Population growth, urbanization, and growing volumes of travel and trade have contributed to new threats to food safety, global food security, and long-term food system sustainability.

Although important environmental public health hazards emerge from every sector of the food system, food waste, the increasing demand for meat, and the industrial food animal production system that meets that demand have been recognized as having particularly significant impacts on the environment and human health. Reducing both meat consumption and waste of food and also shifting toward more sustainable food production practices could help us meet our future food needs with fewer resources.

Key Terms

- agroecological practices

- Practices that apply ecological principles to agriculture in ways that mimic natural processes and conserve ecological integrity. Related terms include ecological agriculture, agricultural ecology, sustainable agriculture, and permaculture.

- Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt)

- A soil-dwelling bacterium often used as a biological pesticide. Food crops have had Bt genes inserted; these crops are a major example of genetically modified organisms.

- biodiversity

- The variety, and degree of variation, of different types of organisms found within an area or ecosystem or on the planet.

- biomass

- Biological material derived from living or recently living organisms.

- Codex Alimentarius

- A collection of internationally recognized standards, codes of practice, guidelines, and other recommendations relating to foods, food production, and food safety.

- commodities

- Agricultural crops produced and marketed on a large scale, including corn, soybeans, cotton, rice, and wheat.

- concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO)

- Agricultural operations that keep and raise animals in confined situations. The EPA defines a CAFO (pronounced kayfo) as a facility that confines animals for at least forty-five days per year, without grass or other vegetation, in the confinement area during the normal growing season.

- conservation tillage

- Any method of soil cultivation that leaves the previous year's crop residue (e.g., corn stalks or wheat stubble) on fields between harvesting one crop and planting the next crop, to reduce soil erosion and runoff.

- critical control point (CCP)

- In the HACCP system, a step in the food production process at which a potential food safety hazard exists but can be controlled by an intervention.

- cross-contamination

- The spread of pathogens between foods via, for example, unwashed hands, equipment, or cooking utensils.

- dead zone

- An area of water in which excess nutrients have caused excessive algal blooms that, as they die off and decompose, deplete the oxygen in the water and make it uninhabitable for aquatic life.

- ecosystem services

- Benefits that humans derive from ecosystems.

- embodied energy

- The sum of all the energy required to produce a good or a service.

- eutrophication

- The enrichment of a body of water with nutrients, typically phosphates or nitrates, leading to excessive algal growth, depletion of oxygen in the water, and possibly the death of other organisms such as fish. Eutrophication may occur naturally, but human activity such as fertilizer application on nearby land or poor sewage management can greatly accelerate it.

- Farm Bill

- A multiyear, highly complex piece of U.S. federal legislation that governs an array of agricultural and food programs.

- Food Code

- A model, published by the FDA, that provides state, local, and tribal food control authorities with a technical and legal basis for regulating the retail and food service industries, including restaurants, grocery stores, and institutions such as nursing homes (also called Model Food Code).

- food desert

- An area with low access to healthy foods, commonly a low-income urban or rural area without nearby supermarkets.

- food environment

- All aspects of our surroundings that may influence our diets, including physical locations of stores, marketing, media, and online exposures.

- food loss

- The decrease in edible food mass at the production, postharvest, and processing stages of the food chain.

- Food Quality Protection Act

- A 1996 U.S. federal law amending the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA). Major provisions altered the EPA's approach to pesticide regulation, requiring stricter safety standards, especially for infants and children, a complete reassessment of all existing pesticide tolerances, and the establishment of a standard of “reasonable certainty of no harm.”

- food recalls

- Voluntary actions by manufacturers or distributors to protect the public from products that may cause health problems or possibly death.

- Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA)

- U.S. federal legislation passed in 2011 that reformed federal regulation of food safety.

- food security

- A condition in which all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

- food waste

- Discarded edible foods, either at any point along the food chain or, in some definitions, only at the retail and consumer levels. Examples include cooking loss; natural shrinkage (such as with moisture loss); loss from mold, pests, or inadequate climate control; food discarded by retailers due to color or appearance; and plate waste and other food discarded by consumers.

- FoodNet

- Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, a collaborative effort of the CDC, USDA, FDA, and local health departments to conduct surveillance for common foodborne pathogens.

- fossil aquifer

- An underground body of water, in a bed or layer of earth, gravel, or porous stone, established thousands or millions of years ago under past climatic and geological conditions, that cannot be replenished on a human time scale.

- genetically modified organism (GMO)

- An organism whose genome has been altered through the techniques of genetic engineering so that its DNA contains one or more genes not normally found there.

- glyphosate

- A broad-spectrum, systemic herbicide used to kill weeds that compete with commercial crops and grow in lawns and gardens. The most common glyphosate product is Roundup. A gene for glyphosate resistance, inserted into corn and other food crops, is a major example of genetic modification of food.

- harmful algal bloom (HAB)

- An accumulation of algae in a body of water that can damage other organisms.

- Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP)

- HACCP (pronounced hassip) is a food safety system in which each step in the manufacture, storage, and distribution of food is analyzed and measures are implemented to reduce and/or eliminate identified potential risks before they occur.

- herbicide tolerance

- The ability of a plant species to survive and reproduce after being exposed to an herbicide.

- industrial food animal production (IFAP)

- IFAP (pronounced eye-fap) is an approach to meat, dairy, and egg production characterized by specialized operations designed for a high rate of production, large numbers of animals confined at high density, large quantities of localized animal waste, and substantial inputs of capital, fossil fuel, feed, pharmaceuticals, and indirect inputs (e.g., fuel and water) embodied in feed.

- inputs

- Resources and materials entering a production system: for example, the feed, drugs, energy, water, and labor that go into the food system.

- integrated pest management (IPM)

- A system of controlling pests that applies the least toxic pesticides possible and only as a last resort after trying other control measures.

- integrators

- Companies that coordinate multiple successive stages of the supply chain in the hog and poultry industries.

- manure cesspits

- Open-air, earthen storage basins for liquid cattle or swine waste from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

- monocultures

- Extensive plantings of a single variety of a single crop.

- organic food

- Food produced without the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, and animal products produced without hormones or antibiotics.

- persistent organic pollutants

- Toxic chemicals that persist and accumulate in the environment and are passed from one species to the next through the food chain.

- potentially hazardous food

- Food that contains moisture and protein, is pH neutral or slightly acidic, and is capable of supporting the rapid and accelerating growth of infectious or toxigenic microorganisms.

- prerequisite programs

- Practices and conditions considered essential for food safety, implemented prior to and during the implementation of HACCP.

- PulseNet

- A network of federal, state, and local laboratories that conduct DNA “fingerprinting” of bacteria to analyze and detect foodborne outbreaks.

- specialty crops

- Noncommodity crops, including fruits, vegetables, tree nuts, and horticulture and nursery plants.

- time and temperature controls

- Procedures that aim to avoid the growth of pathogens, including avoiding keeping food in the “danger zone” (between 40° and 140°F).

- traceability

- In food safety, the ability to track any food, feed, substance, or livestock through all stages of production, processing, and distribution.

Discussion Questions

- Please review Text Box 19.1, regarding policy approaches to agricultural antibiotic use.

- Do you think the United States can accomplish changes in how antibiotics are used animal agriculture like those seen in Denmark? Why or why not?

- What are the main barriers to minimizing or ending antibiotic misuse in animal agriculture in the United States? How could these barriers be addressed?

- Go to the Web site of your local health department. Look up the food inspection results from the last three restaurants at which you ate. Describe any violations you see. Do you have any concerns? Are you confident that the inspectors were able to detect all significant problems?

- Please review Text Box 19.2. What does the USDA Organic label mean to you? What are the pros and cons of large multinational food companies dominating the organic food sector?

- What are the benefits of taking a systems approach to studying the environmental public health implications of our food?

- Which comes first in changing the food system: supply or demand?

References

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, American Nurses Association, American Planning Association, and American Public Health Association. (2012). Principles of a healthy, sustainable food system. Retrieved from https://www.apha.org/∼/media/files/pdf/topics/healthy_sustainable_food_systems_principles_2012may.ashx

- Agriculture and Community Development Services. (n.d.). Agricultural trends profile for Duplin County, NC. Retrieved from http://www.duplincountync.com/pdfs/Agricultural%20Trends%20Profile%20for%20Duplin%20County.pdf

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2102). Statement by the AAAS board of directors on labeling of genetically modified foods. http://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/AAAS_GM_statement.pdf.

- Antoniou, M., Habib, M.E.M., Howard, C. V., Jennings, R. C., Leifert, C., Nodari, R. O.,…Fagan, J. (2012). Teratogenic effects of glyphosate-based herbicides: Divergence of regulatory decisions from scientific evidence. Journal of Environmental and Analytical Toxicology, S4-006.

- Balfour, Lady Eve. (1977). Towards a sustainable agriculture—the living soil. Presentation at the IFOAM Conference, Sissach, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010116balfourspeech.html

- Batz, M. B., Hoffmann, S., & Morris, J. G. (2012). Ranking the disease burden of 14 pathogens in food sources in the United States using attribution data from outbreak investigations and expert elicitation. Journal of Food Protection, 75(7), 1278–1291.

- Beaulac, J., Kristjansson, E., & Cummins, S. (2009). A systematic review of food deserts, 1966–2007. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6(3), A105.

- Benbrook, C. M. (2012). Impacts of genetically engineered crops on pesticide use in the U.S.—the first sixteen years. Environmental Sciences Europe, 24, 24.

- Buck E. H. (2010). Seafood marketing: Combating fraud and deception. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from http://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RL34124.pdf

- Burkett, A. (2012). Food safety in the United States: Is the Food Safety Modernization Act enough to lead us out of the jungle? Alabama Law Review, 63(4), 919–940.

- Buzby, J. C., Wells, H. F., & Hyman, J. (2014). The estimated amount, value, and calories of postharvest food losses at the retail and consumer levels in the United States (U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Information Bulletin No. EIB-121). Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib-economic-information-bulletin/eib121.aspx#.VEp2mRYnmHs

- Canfield, D. E., Glazer, A. N., & Falkowski, P. G. (2010) The evolution and future of Earth's nitrogen cycle. Science, 330(6001), 192–196.

- Center for Science in the Public Interest. (2014). Risky meat: A CSPI field guide to meat & poultry safety. Retrieved from http://cspinet.org/foodsafety/riskymeat.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). CDC estimates of foodborne illnesses in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/2011-foodborne-estimates.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, March 14). CDC research shows outbreaks linked to imported foods increasing: Fish and spices the most common sources (Press release). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2012/p0314_foodborne.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013a). Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013b). Contribution of different food commodities (categories) to estimated domestically-acquired illnesses and deaths, 1998-2008. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/attribution-image.html#foodborne-illnesses

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013c). PulseNet & foodborne disease outbreak detection. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/features/dsPulseNetFoodborneIllness

- Clayton, M. L., Smith, K. C., Neff, R. A., Pollack, K. M., & Ensminger, P. (2015). Listening to food workers: Factors that impact proper health and hygiene practice in food service. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. Advance online publication.

- Codex Alimentarius. (2015). About Codex. Retrieved from http://www.codexalimentarius.org/about-codex/en

- Collignon, P., Powers, J. H., Chiller, T. M., Aidara-Kane, A., & Aarestrup, F. M. (2009). World Health Organization ranking of antimicrobials according to their importance in human medicine: A critical step for developing risk management strategies for the use of antimicrobials in food production animals. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 49(1), 132–141.

- Diaz, R. J., & Rosenberg, R. (2008). Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science, 321(5891), 926–929.

- Donham, K. J. (2010). Community and occupational health concerns in pork production: A review. Journal of Animal Science, 88(13, Suppl.), E102–111.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. (2010). A decade of EU-funded GMO research (2001–2010). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/research/biosociety/pdf/a_decade_of_eu-funded_gmo_research.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2011a). Global food losses and food waste—extent, causes, and prevention. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/mb060e/mb060e.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2011b). State of land and water resources for agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/015/i1688e/i1688e00.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2013). Food wastage footprint: Impacts on natural resources. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3347e/i3347e.pdf

- Furuno, T. (2001). The power of duck: Integrated rice and duck farming. Sisters Creek, Tasmania: Tagari.

- Goetz, G. (2010). Who inspects what? A food safety scramble. Food Safety News. Retrieved from http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2010/12/who-inspects-what-a-food-safety-scramble/#.VEuvPRYnmHt

- Gossner, C. M.-E., Schlundt, J., Ben Embarek, P., Hird, S., Lo-Fo-Wong, D., Beltran, J. J.,…Tritscher, A. (2009). The melamine incident: Implications for international food and feed safety. Environmental Health Perspectives, 117(12), 1803–1808.

- Gould, L. H., Walsh, K. A., Vieria, A. R., Herman, K., Williams, I. T., Hall, A. J., & Cole, D. (2013). Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks—United States, 1998–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(SS02), 1–34.

- Graham, J. P., & Nachman, K. E. (2010). Managing waste from confined animal feeding operations in the United States: The need for sanitary reform. Journal of Water and Health, 8(4), 646–670.

- Guyton, K. Z., Loomis, D., Grosse, Y., El Ghissassi, F., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., Guha, N.,…Straif, K. (2015). Carcinogenicity of tetrachlorvinphos, parathion, malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate. Lancet: Oncology, 16(5), 490–491.

- Hall, K. D., Guo, J., Dore, M., & Chow, C. C. (2009). The progressive increase of food waste in America and its environmental impact. PLoS One, 4(11).

- Hathorn, B. (2012). Jack in the Box in Laredo, Texas IMG 6011 [Photo]. Retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jack_in_the_Box_in_Laredo,_Texas_IMG_6011.JPG#/media/File:Jack_in_the_Box_in_Laredo,_Texas_IMG_6011.JPG

- Hilbeck, A., Binimelis, R., Defarge, N., Steinbrecher, R., Székács, A., Wickson, F.,…Wynne, B. (2015). No scientific consensus on GMO safety. Environmental Sciences Europe, 27, 4.

- Horrigan, L. (Producer), & Moore, A. (Director). (2010). Out to pasture: The future of farming? [Motion picture]. USA.

- Hossain, S. T., Sugimoto, H., Ahmed, G.J.U., & Islam, M. R. (2005). Effect of integrated rice-duck farming on rice yield, farm productivity, and rice-provisioning ability of farmers. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development, 2(1&2), 79–86.

- Howard, Sir Albert. (1943). An agricultural testament. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hueston, W., & McLeoad, A. (2012). Improving food safety through a One Health approach: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Hulebak, K. L., & Schlosser, W. (2002). Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) history and conceptual overview. Risk Analysis, 22(3), 547–552.

- International Food Information Center Foundation. (2012). Food and health survey. Retrieved from www.foodinsight.org/Content/5519/IFICF_2012_FoodHealthSurvey.pdf

- Jackson, L. S. (2009). Chemical food safety issues in the United States: Past, present and future. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 57(18), 8161–8170.

- Kensler, T. W., Roebuck, B. D., Wogan, G. N., & Groopman, J. D. (2011). Aflatoxin: A 50-year odyssey of mechanistic and translational toxicology. Toxicological Sciences, 120, S28–48.

- Kim, B., Laestadius, L., Lawrence, R., Martin, R., McKenzie, S., Nachman, K.,…Truant, P. (2013) Industrial food animal production in America: Examining the impact of the Pew Commission's priority recommendations. Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. Retrieved from http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-a-livable-future/_pdf/research/clf_reports/CLF-PEW-for%20Web.pdf

- Kirschenmann, F. (2000). The hijacking of organic agriculture…and how USDA is facilitating the theft. International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM); Ecology and Farming. Retrieved from www.organicconsumers.org/old_articles/Organic/kirschenmann.php

- Kummerer, K. (2004). Resistance in the environment. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 54, 311–320.

- Kummu, M., de Moel, H., Porkka, M., Siebert, S., Varis, O., & Ward, P. J. (2012). Lost food, wasted resources: Global food supply chain losses and their impacts on freshwater, cropland, and fertiliser use. Science of the Total Environment, 438, 477–489.

- Lawrence, R. S., Nachman, K. E., & Smith, T. J. (2013). Antibiotics: Collect more US data. Nature, 500(7463), 400.

- Lelieveld, H. (2015). Mycotoxins: A food safety crisis. Food Safety, February 3. Retrieved from http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/enewsletter/mycotoxins-a-food-safety-crisis