2. Conceptual models of boundary dynamics

4. Dynamics of boundaries in response to climate and disturbance

6. Consequences of boundary dynamics for animal populations

7. Approaches to detect boundary locations

8. Applying boundary dynamics to management

Landscapes consist of a mosaic of distinct vegetation types and their intervening boundaries with distinct characteristics. Boundaries can exist along abrupt environmental gradients or along gradual changes that are reinforced by feedback mechanisms between plants and soil properties. Boundaries can be defined based on the abundance, spatial distribution, and connectivity of the underlying patches. There are three major types of boundary dynamics that differ in the direction and rate of movement of the boundary in response to climatic fluctuations: stationary, directional, and shifting. Future conditions in climate and the disturbance regime, including land use, may fundamentally alter the type of boundary as well as its location and composition through time.

boundary (ecotone). Transition area where spatial changes in vegetation structure or ecosystem process rates are more rapid than in the adjoining plant communities

corridor. Edge that promotes movement or allows unimpeded movement of organisms between local populations

directional transition. Location of a boundary between two areas that moves unidirectionally through time

edge. Well-defined area between patch types; often a barrier, constraint, or limit to the movement of animals and plants

patch. Discrete, bounded area of any spatial scale that differs from its surroundings in its biotic and abiotic structure and composition

shifting transition. Boundary location that shifts back and forth with no net change over time

state. Defined by either the dominant species or composition of species, and associated process rates

stationary transition. Boundaries that are stable with little movement through time

Landscapes consist of a mosaic of distinct vegetation types and intervening boundaries (or ecotones) with different characteristics from the adjacent communities. An ecotone is a transition zone in time and space. Ecotones along spatial gradients in edaphic and climatic factors (e.g., elevation, soil texture, precipitation) have a long history in ecological studies. Gradual environmental gradients underlying vegetation transitions also exist, often related to positive feedbacks between plants and their environment. Ecotones are increasingly recognized as important elements of dynamic landscapes because of their effects on the movement of animals and materials, rates of nutrient cycling, and levels of biodiversity. Because dramatic shifts in location of vegetation types can occur at ecotones, these can also be important for management and as indicators of climate change.

Ecotones along spatial gradients, such as the treeline along an elevation gradient, have long been recognized by ecologists as important elements of landscapes. The term zone of tension between two plant community types dates to Clements (1904). Focused research on a broader definition of ecotones began in earnest in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Theoretical models were developed that laid the foundation for future research that considered ecotones as transitional areas between different vegetation types (Gosz, 1993). Many of these models included a hierarchy of spatial scales to depict ecotones, from plant edges to populations, patches, landscapes, and biomes. Most research initially focused on transition zones between biomes that cover large spatial extents, such as between grasslands and forests or between different grassland types. At the biome scale, ecotones were viewed as consisting of a collection of patches where the number and size of patches vary spatially across long distances (hundreds of kilometers). In general, average patch size was predicted to decrease as the distance from a biome or core population increased because of the loss of suitable habitats with increasing distance. Under conditions of increasing resource availability as distance to the biome edge decreased, patches were predicted to coalesce and shift the spatial location of an ecotone through time.

More recent conceptual models have focused on ecotones at landscape scales and have questioned this general relationship between patch size and distance from a core population. Some models focus on the properties of boundaries that influence the rate and pattern of movement of organisms, matter, and energy between adjacent areas (e.g., Wiens, 2002). In other cases, models have focused on boundary dynamics and the use of patch dynamics to provide new understanding about the structural and functional properties of ecotones. Patch dynamics theory has been integrated with hierarchy theory to relate pattern, process, and scale within the context of landscapes (chapter IV.3). A similar patch dynamics approach also allows prediction of changes in boundary location through time and across space (Peters et al., 2006).

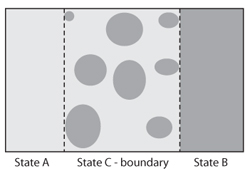

Landscapes consist of a mosaic of different vegetation states defined by the abundance, spatial distribution, and connectivity of patches (figure 1, and see chapter IV.1). In some cases, these states represent well-defined, homogeneous plant communities that consist of highly aggregated, well-connected patches of that community (states A and B, figure 1). Patches of other states occur infrequently within that state and do not contribute significantly to its overall dynamics. Boundaries between states consist of disaggregated patches of different types with large differences in patch properties and variable connectivity (state C, figure 1). This heterogeneity in patch properties and distribution can result in nonlinear rates of ecological flows across the spatial extent of a boundary.

Patch properties are particularly important to boundary characteristics by determining both their internal function and the connections among patches that determine boundary dynamics. Patch size, type, spatial configuration, and connectivity are key properties that influence the function and dynamics of boundaries.

Figure 1. A biotic transition consists of two states (A. B) with a boundary state (C) between them. (Redrawn from Peters et al.. 2006) The boundary consists of patches from both states that vary in size, type, spatial configuration, and degree of connectivity.

The importance of patch size to function has often been recognized in landscape studies (Mazerolle and Villard, 1999). Patch size has effects on within-patch processes, such as nitrogen cycling and plant recruitment, and processes that connect patches, such as animal movement (chapter IV.1). As patch size increases, there is an exponential decrease in the perimeter-to-surface area ratio with geometric effects on patch function. Although patches have traditionally been considered internally homogeneous, edges and centers of patches can differ substantially with important consequences for ecosystem processes and animal responses. For example, small patches with large perimeter-to-surface area ratios can have high population densities of animal species that are restricted to edges, whereas large patches can contain high population densities of species associated with patch interiors.

Depending on the function concerned, the effects of patch size are effective over a particular range of sizes. For example, small animals may not forage on isolated shrubs located in large patches of grassland because there is insufficient cover, which increases the risk of predation. Once a patch consists of a larger group of shrubs, then the combined cover may be sufficient for small animals to risk moving to that patch for forage. In addition, the aggregation of plants into larger patches can have important effects on microclimate and wind and water erosion-deposition patterns that affect ecosystem processes such as seed germination, seedling establishment, and plant growth. Thus, patches consisting of groups of plants may have higher probabilities of recruitment and grow faster than expected based on the recruitment and growth of isolated individual plants within the adjacent state. As patch size continues to increase, the patch is sufficiently large that the addition of new plants and the associated increase in patch size have little influence on patch function or connectivity. Thus, for patches of this size or larger, ecosystem response within the patch is similar to the function of the state.

Patch type is defined by the composition and abundance of plant species within a patch and is typically determined by the species with the highest proportion of cover that dominate patch function. Examples include grassland and forest patches that differ in structure and response to environmental drivers.

Patch function and dynamics are also influenced by the spatial configuration and connections among patches. Spatial configuration refers to the distribution of patches and includes measures of richness, evenness, and dispersion (chapter IV.2). Connectivity includes the functional relationships among patches as a result of spatial properties of the landscape and movement of organisms in response to this landscape structure. Some patch types are highly connected, whereas other patch types are rarely, if ever, connected. For terrestrial systems, interactions among patches occur through the movement of water, soil particles, nutrients, or seeds. The vectors of movement are water, wind, animals, and people. Thus, both structural and functional connectivity are included in these interactions. Spatial configuration, including isolation, often interacts with patch size to influence connectivity. Patches of similar size and type located close together have a greater probability of being connected than patches of similar characteristics that are separated by large distances.

Boundary dynamics depends on (1) abiotic drivers (climate, disturbance) interacting with (2) properties of patches comprising the boundary and adjoining states, (3) biological processes that occur within patches (e.g., competition) and spatial processes that connect patches (e.g., seed dispersal, horizontal water movement), and (4) soil properties that determine water and nutrient availability (e.g., particle size distribution). Through time, new patches are created as plants are recruited, current patches can expand and coalesce with plant recruitment and growth, and patches can be lost as a result of plant mortality. The location and functional properties of a boundary can change through time as patches either increase or decrease in number and spatial extent.

There are three major types of dynamics that differ in the direction and rate of movement of the boundary in response to climatic fluctuations: stationary, directional, and shifting. The importance of four drivers or constraints determine which of these dynamics occurs for any given boundary: (1) abiotic drivers (climate, disturbance), (2) biotic feedback mechanisms among plants, animals, and soil biota, (3) inherent abiotic constraints (e.g., parent material, elevation), and (4) dynamic abiotic feedback mechanisms, such as organic matter and microclimate, that are influenced by the plant community. The width of the boundary and the relationship between patch size and distance from the core population vary for each type.

Stationary boundaries are stable over scales of decades with little movement of patches between states as climate fluctuates (figure 2A). However, disturbances that cause widespread plant mortality (e.g., fire, overgrazing), either along the boundary or in an adjacent state impacted by the disturbance, can shift the boundary through time and space. Although the width of the boundary is narrow and appears as an edge (figure 3A), small-scale fluctuations in boundary location can occur through time with climatic fluctuations. There is no relationship between patch size and distance from an associated state because the boundary is narrow.

Directional boundaries involve the movement by plants and patches from one state into another state such that the location of the boundary moves unidirectionally through time (figure 2B). Directional boundaries are strongly influenced by abiotic drivers, and biotic and abiotic feedback mechanisms that maintain the expansion of plants across the landscape. For example, wet summers combined with overgrazing by livestock can promote the recruitment of native woody plants and initiation of patches in neighboring grassland states located at large distances from the woody-plant-dominated state. Following patch initiation, both positive and strong abiotic feedback mechanisms act to promote the maintenance of the invading patch through time. Positive feedback mechanisms also promote patch expansion and coalescence through the increased probability of recruitment of new individuals within the patch as its size increases. Animal movement between patches leads to increased connectivity of patches as distance between patches decreases. The width of the boundary is intermediate with isolated recruits located at large distances from the advancing state (figure 3B). In general, patch size is largest near its own state, where patches have had time to coalesce; patch size decreases as distance from its state increases.

Figure 2. Three types of boundaries, (A) stationary, (B) directional, and (C) shifting, with different dynamics, patch properties, and important constraints and feedbacks.

Shifting boundaries occur when the location of a boundary moves back and forth through time with no net change in its location (figure 2C). These boundaries are very responsive to fluctuating climatic conditions that promote different states during different time periods. For example, a multiyear summer drought may result in high mortality of one plant species, which allows a neighboring species to expand its spatial extent across the boundary. A multiyear winter drought that favors the first species will result in a shift back to the original boundary location or farther depending on the extent of recruitment and mortality of the two species. Disturbances such as fire that reduce cover but not plant density will shift the boundary toward fire-tolerant species until the other species recovers. The boundary is typically broad (figure 3C) with no relationship between patch size and distance from the core population. Extensive periods of overgrazing by livestock and other disturbances that cause widespread plant mortality of one species over another may move these boundaries into a directional phase.

Landscape dynamics depends on the mosaic of boundary types that occur within the landscape. Many landscapes contain more than one type of boundary; thus, both spatial and temporal variation in dynamics are possible. For example, at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge in central New Mexico, landscapes have all three types of boundaries that vary in their response to climatic fluctuations and grazing by cattle (plate 9). The stationary boundaries in this landscape occur most frequently between two grass species, Bouteloua gracilis (blue grama) and B. eriopoda (black grama), which dominate on different soils. These boundaries are controlled by soil texture constraints and soil water availability interacting with plant life-history traits. These boundaries are stable even under conditions of changes in seasonal rainfall (winter, summer) and grazing by or exclusion from cattle.

By contrast, shifting boundaries at the Sevilleta are responsive to both seasonal rainfall and cattle gazing (plate 9C, D). They occur between blue grama and black grama grasslands located on soils with intermediate sand and clay contents. Black grama expands into boundaries under summer rainfall without grazing, whereas blue grama expands with livestock grazing under a similar rainfall regime. These responses reflect different plant traits by these two species. Black grama, a characteristic species of the Chihuahuan Desert, is less grazing-tolerant than blue grama, a characteristic species of the Shortgrass Steppe, a system that evolved with heavy grazing by large herbivores, in particular bison.

Finally, directional transitions occur at the Sevil-leta as a result of the invasion by the native woody plant Larrea tridentata (creosotebush), primarily into black grama grasslands (plate 9B). This expansion and subsequent conversion of grasslands into shrublands are promoted with grazing and either summer or winter rainfall. Shifts in dominance from grasses to shrubs are maintained by positive feedback mechanisms between shrubs and their localized soil environment.

Figure 3. Boundary width for each type of boundary based on the overlap in patches from each state: (A) narrow edges of stationary boundaries, (B) intermediate widths of directional boundaries, and (C) broad transition zones of shifting boundaries.

The importance of edges as features of landscapes has a long history in animal ecology, dating to Leopold (1933). Edges between vegetation types were historically viewed as positive features with high plant productivity and biodiversity that resulted in favorable habitat for animals. However, as landscapes have become increasingly fragmented, as a result of changing patterns of land use and patchily distributed disturbances (e.g., wildfire, hurricanes, floods, drought), it is increasingly recognized that edges, and more broadly boundaries, can have both positive and negative effects on animal populations. As landscapes become more fragmented, habitat patches become smaller and more isolated, resulting in smaller animal populations with less movement between patches. Species adapted to the interior of patches avoid edges and reduce their effective habitat area or have lower growth and survival rates at habitat edges. Alternatively, exotic species can spread more rapidly as the density and extent of edges increase across a landscape. Thus, both the ratio of edge-to-interior species can change and the ratio of native-to-exotic species can change with landscape fragmentation.

Effects of boundaries and edges on animal populations are related to their permeability, from impermeable to semipermeable to permeable. Corridors are permeable edges where the movement of organisms can be promoted or unimpeded. Permeability of a corridor can vary by animal species, gender, and age, even for animals within the same landscape. For example, adult female gray-tailed voles (Microtus canicaudis) tend to avoid corridors as they get older and presumably more dominant socially (Lidicker and Peterson, 1999).

Animal populations can also have important feedback to boundary dynamics. Effects of animals on seed availability, from production to dispersal and storage of viable seeds, and seedling establishment can effectively shift boundary locations by favoring one plant species or another or by limiting or promoting the expansion of invasive species.

Boundary locations can be difficult to determine depending on the scale of observation (plate 10). Both the spatial extent of the landscape and the resolution of the sampling unit need to be considered. The spatial extent needs to be sufficiently large to ensure that both end states and the boundary can be characterized (figure 1). The resolution or grain should be large enough to contain more than one individual or patch of interest yet small enough to allow edge detection. A variety of statistical methods have been developed, primarily for abrupt boundaries, although more recent advances also apply to gradual boundaries (Fagan et al., 2003). After boundaries have been identified, overlap statistics can be used to examine relationships between boundaries, for example, to compare the movement of a boundary through time. Dynamic modeling can be used to simulate the effects of boundaries on ecological processes of interest.

Management of natural systems often requires an understanding about the dynamics of boundaries in addition to information about the adjacent states. Predicting changes in the location and composition of boundaries is of particular interest to land managers. Prediction will require an understanding of the type of boundary being considered (stationary, directional, shifting) and the drivers and biological processes controlling those dynamics. The future variation in environmental drivers and consequences of that variation for the key ecological processes will also be important. If this variability in drivers is within the realm of past and current conditions, then confidence can be placed in predictions of future boundary location and composition. However, unforeseen changes in drivers or the appearance of novel disturbances, such as cultivation or housing developments, which go beyond experience to date, may result in new boundary dynamics. For example, boundaries that appear stationary under current conditions may become directional or shifting with large increases in temperatures or decreases in precipitation that either restrict plant recruitment or increase mortality.

Introduction of exotic species into a landscape containing a stationary or shifting boundary may result in a directional change as the species expands its spatial distribution. The ability of land managers to effectively manage for these spatially and temporally variable conditions will require an explicit understanding of the composition of each boundary in the landscape, including patch size, type, and spatial configuration, as it is related to changing environmental drivers.

This chapter is Sevilleta publication number 403.

Clements, F. E. 1904. The Development and Structure of Vegetation. Studies in the Vegetation of the State. III. Botanical Survey of Nebraska VII. Lincoln, NE: Woodruff-Collins Printing Co.

Curtis, J. T. 1959. The Vegetation of Wisconsin: An Ordination of Plant Communities. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. A classic book on boundaries.

Fagan, W. F., M.-J. Fortin, and C. Soykan. 2003. Integrating edge detection and dynamic modeling in quantitative analyses of ecological boundaries. BioScience 53: 730–738.

Forman, R.T.T. 1995. Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. A good general text on landscape ecology.

Fortin, M.-J., R. J. Olson, S. Ferson, I. Iverson, C. Hunsaker, G. Edwards, D. Levine, K. Butera, and V. Klemas. 2000. Issues related to the detection of boundaries. Landscape Ecology 15: 453–466. A discussion of methods related to boundary detection.

Gosz, J. R. 1993. Ecotone hierarchies. Ecological Applications 3: 369–376.

Hansen, A. J., and F. di Castri, eds. 1992. Landscape Boundaries: Consequences for Biotic Diversity and Ecological Flows. New York: Springer-Verlag. A more recent book on boundaries.

Leopold, A. 1933. Game Management. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Lidicker, W. Z., Jr. 1999. Responses of mammals to habitat edges: An overview. Landscape Ecology 14: 333–343. An overview of animal responses to boundaries.

Lidicker, W. Z., and J. A. Peterson. 1999. Responses of small mammals to habitat edges. In G. W. Barrett and J. D. Peles, eds., Landscape Ecology of Small Mammals. New York: Springer-Verlag, 211–227

Mazerolle, M. J., and M. Villard. 1999. Patch characteristics and landscape context as predictors of species presence and abundance: A review. Ecoscience 6: 117–124.

Peters, D.P.C., J. R. Gosz, W. T. Pockman, E. E. Small, R. R. Parmenter, S. L. Collins, and E. Muldavin. 2006. Integrating patch and boundary dynamics to understand and predict biotic transitions at multiple scales. Landscape Ecology 21: 19–;23.

Risser, P. G. 1995. The status of the science examining ecotones. BioScience 45: 318–325.

Wiens, J. A. 2002. Riverine landscapes: Taking landscape ecology into the water. Freshwater Biology 47: 501–515.

Wiens, J. A., C. S. Crawford, and J. R. Gosz. 1985. Boundary dynamics: A conceptual framework for studying landscape ecosystems. Oikos 45: 421–427. An early conceptual framework for boundaries.