Luxor

Sights

Activities

Courses

Tours

Festivals & Events

Sleeping

Eating

Drinking & Nightlife

Entertainment

Shopping

Information

Getting There & Away

Getting Around

Luxor

![]() %095 / Pop 1,088,911

%095 / Pop 1,088,911

Why Go?

Luxor is often called the world’s greatest open-air museum, but that comes nowhere near describing this extraordinary place. Nothing in the world compares to the scale and grandeur of the monuments that have survived from ancient Thebes.

The setting is breathtakingly beautiful, the Nile flowing between the modern city and west-bank necropolis, backed by the enigmatic Theban escarpment. Scattered across the landscape is an embarrassment of riches, from the temples of Karnak and Luxor in the east to the many tombs and temples on the west bank.

Thebes’ wealth and power, legendary in antiquity, began to lure Western travellers from the end of the 18th century. Depending on the political situation, today’s traveller might be alone at the sights, or be surrounded by coachloads of tourists from around the world. Whichever it is, a little planning will help you get the most from the magic of Thebes.

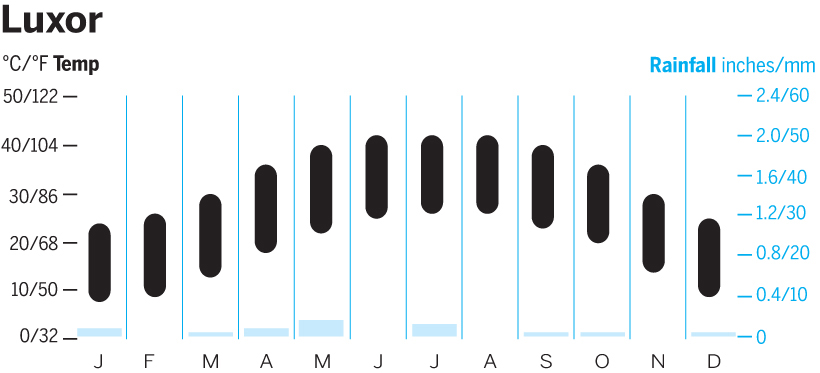

When to Go

- Apr–May & Oct–Nov Some of the best months to visit, with the richest light.

- Sha’aban (Mar–May) The month when the city celebrates its holy man, Youssef Abu Al Haggag.

- 26 NovThe day Howard Carter opened the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922.

Best Places to Eat

Best Places to Stay

Luxor Highlights

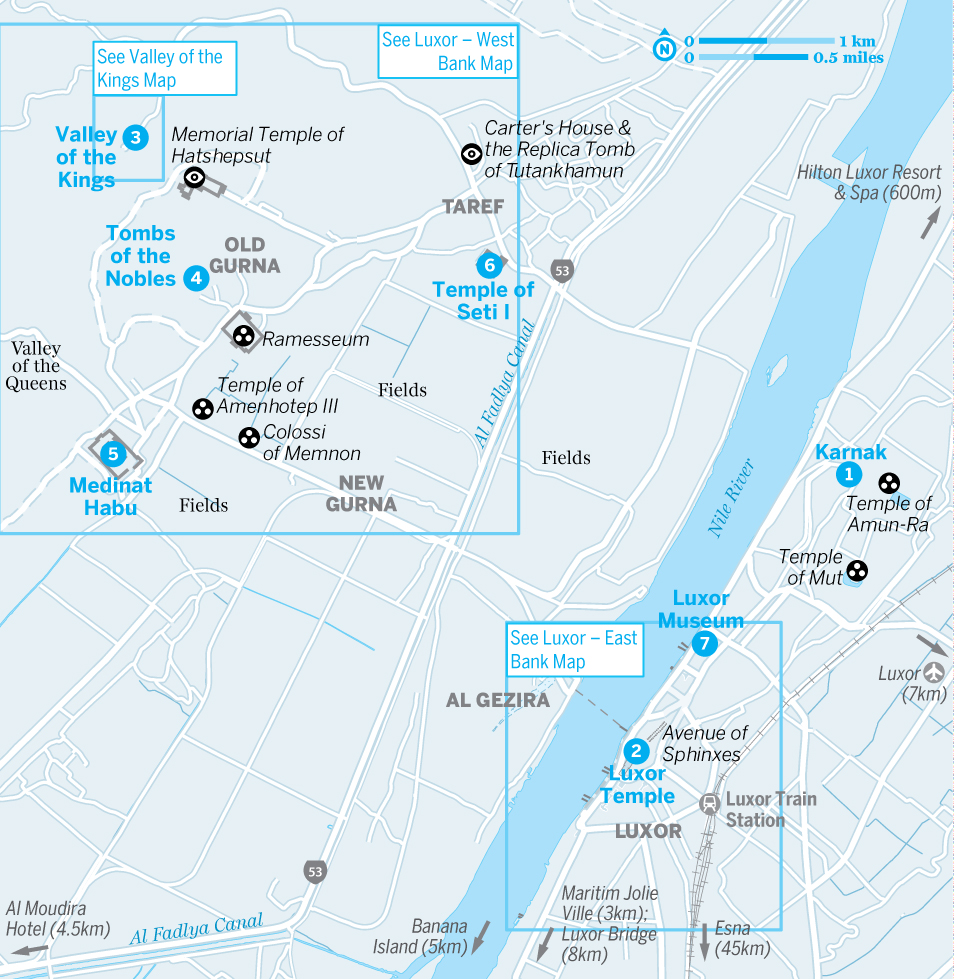

1 Karnak Wandering around the exotic stone thickets of gigantic papyrus-shaped columns in the great hypostyle hall.

2 Luxor Temple Marvelling at the stunning architecture and returning later at night to see the beautifully lit carvings on the walls.

3 Valley of the Kings Being led by the gods into the afterworld, like the pharaoh.

4 Tombs of the Nobles Glimpsing the good life of an ancient Egyptian aristocrat on the tomb walls.

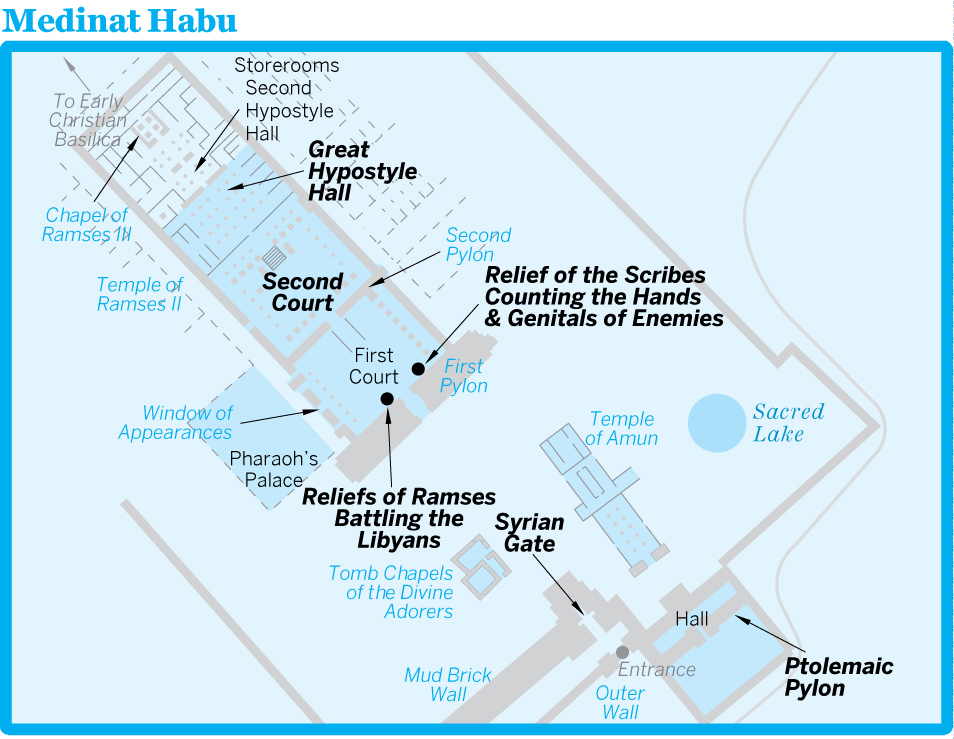

5 Medinat Habu Wandering through the best-preserved Theban temple in the soft late-afternoon light.

6 Temple of Seti I Sensing the spirituality of this rarely visited temple.

7 Luxor Museum Seeing the treasures in this beautiful museum.

History

Thebes (ancient Waset) became important in the Middle Kingdom period (2055–1650 BC). The 11th-dynasty Theban prince Montuhotep II (2055–2004 BC) reunited Upper and Lower Egypt, made Thebes his capital and increased Karnak’s importance as a cult centre to the local god Amun with a temple dedicated to him. The 12th-dynasty pharaohs (1985–1795 BC) moved their capital back north, but much of their immense wealth from expanded foreign trade and agriculture, and tribute from military expeditions made into Nubia and Asia, went to Thebes, which remained the religious capital. This 200-year period was one of the richest times throughout Egyptian history, which witnessed a great flourishing of architecture and the arts, and major advances in science.

It was the Thebans again, under Ahmose I, who, after the Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BC), drove out the ruling Asiatic Hyksos and unified Egypt. Because of his military victories and as the founder of the 18th dynasty, Ahmose was deified and worshipped at Thebes for hundreds of years. This was the beginning of the glorious New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC), when Thebes reached its apogee. It was home to tens of thousands of people, who helped construct many of its great monuments.

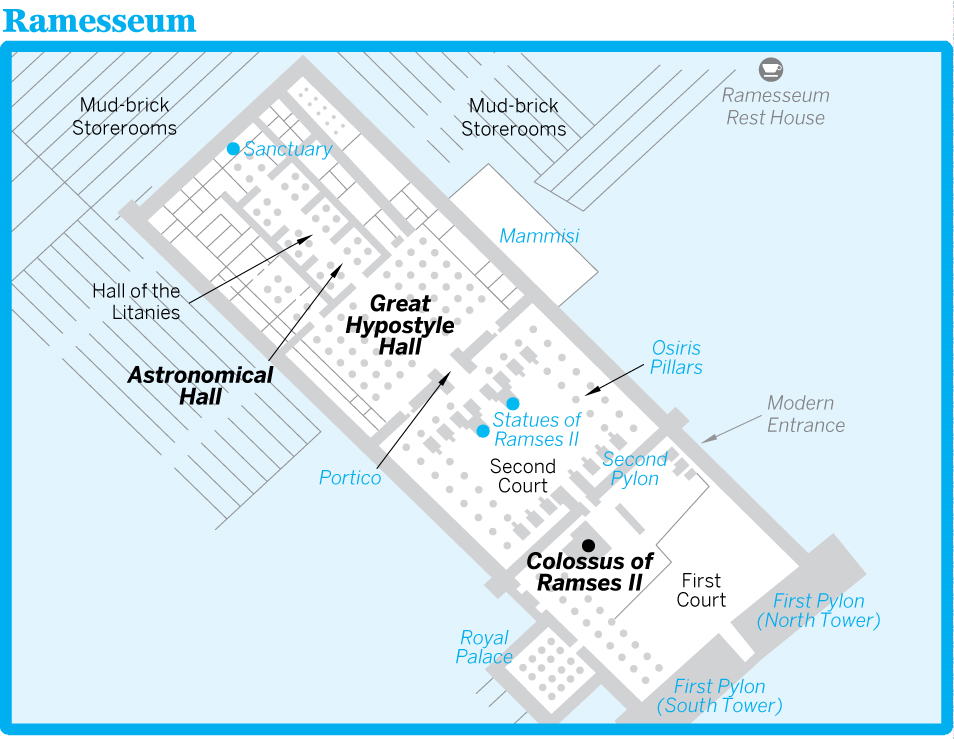

The greatest contributor of all to Thebes was probably Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC). He made substantial additions to the temple complex at Karnak, and built his great palace, Malqata, on the west bank, with a large harbour for religious festivals and the largest memorial temple ever built. Very little of the latter is left beyond the so-called Colossi of Memnon, the largest monolithic statue ever carved. His son Amenhotep IV (1352–1336 BC), who later renamed himself Akhenaten, moved the capital from Thebes to his new city of Akhetaten (Tell Al Amarna), worshipped one god only (Aten, the solar god), and brought about dramatic changes in art and architecture. After his death, the powerful priesthood was soon reinstated under Akhenaten’s successor, Tutankhamun (1336–1327 BC), who built very little but became the best-known pharaoh ever when his tomb was discovered full of treasure in 1922. Ramses II (1279–1213 BC) may have exaggerated his military victories, but he too was a great builder and added the magnificent hypostyle hall to Karnak, other halls to Luxor Temple, and built the Ramesseum and two magnificent tombs in the Valley of the Kings for himself and his many sons.

The decline of Pharaonic rule was mirrored by Thebes’ gradual slide into insignificance: when the Persians sacked Thebes, it was clear the end was nigh. Mud-brick settlements clung to the once mighty Theban temples, and people hid within the stone walls against marauding desert tribes. Early Christians built churches in the temples, carved crosses on the walls and scratched out reliefs of the pagan gods. The area fell into obscurity in the 7th century AD after the Arab invasion, and the only reminder of its glorious past was the name bestowed on it by its Arab rulers: Al Uqsur (The Fortifications), giving modern Luxor its name. By the time European travellers arrived here in the 18th century, Luxor was little more than a large Upper Egyptian village, known more for its 12th-century saint, Abu Al Haggag, buried above the mound of Luxor Temple, than for its half-buried ruins.

The growth of Egyptomania changed that. Napoleon arrived in 1798 wanting to revive Egypt’s greatness and, with the publication of the Description de l’Egypte, did manage to reawaken interest in Egypt. European exhibitions of mummies, jewellery and other spectacular funerary artefacts from Theban tombs (often found by plundering adventurers rather than enquiring scholars) made Luxor an increasingly popular destination for travellers. By 1869, when Thomas Cook brought his first group of tourists to Egypt, Luxor was one of the highlights. Mass tourism had arrived and Luxor regained its place on the world map.

The 1960s saw the start of modern mass tourism on the Nile with Luxor as its epicentre, and more hotels and sights than anywhere else in southern Egypt. The town has since grown into a city of several hundred thousand people, almost all of them dependant on tourism. In the past couple of decades, there have been booms and crashes, the latest crash brought on by the riots that ended the presidencies of Hosni Mubarak and Mohammed Morsi. Tourist numbers have been down since then, and people in Luxor and elsewhere in the south have suffered.

RESOURCES

Luxor Travel Guide (http://luxor-news.blogspot.co.uk) Information on Luxor.

Theban Mapping Project (www.thebanmappingproject.com) History, images and news from the Valley of the Kings.

Flat Rental (www.flatsinluxor.co.uk) Accommodation, guide and tour bookings.

Luxor Times (http://luxortimesmagazine.blogspot.co.uk) The local English-language paper.

1Sights

Luxor sights are spread on the east and west banks of the Nile. Start on the east bank, where visitors will find most of the hotels, the modern city of Luxor and the temple complexes of Luxor and Karnak. The west bank, traditionally the ‘side of the dead’, is where the mortuary temples and necropolis are located.

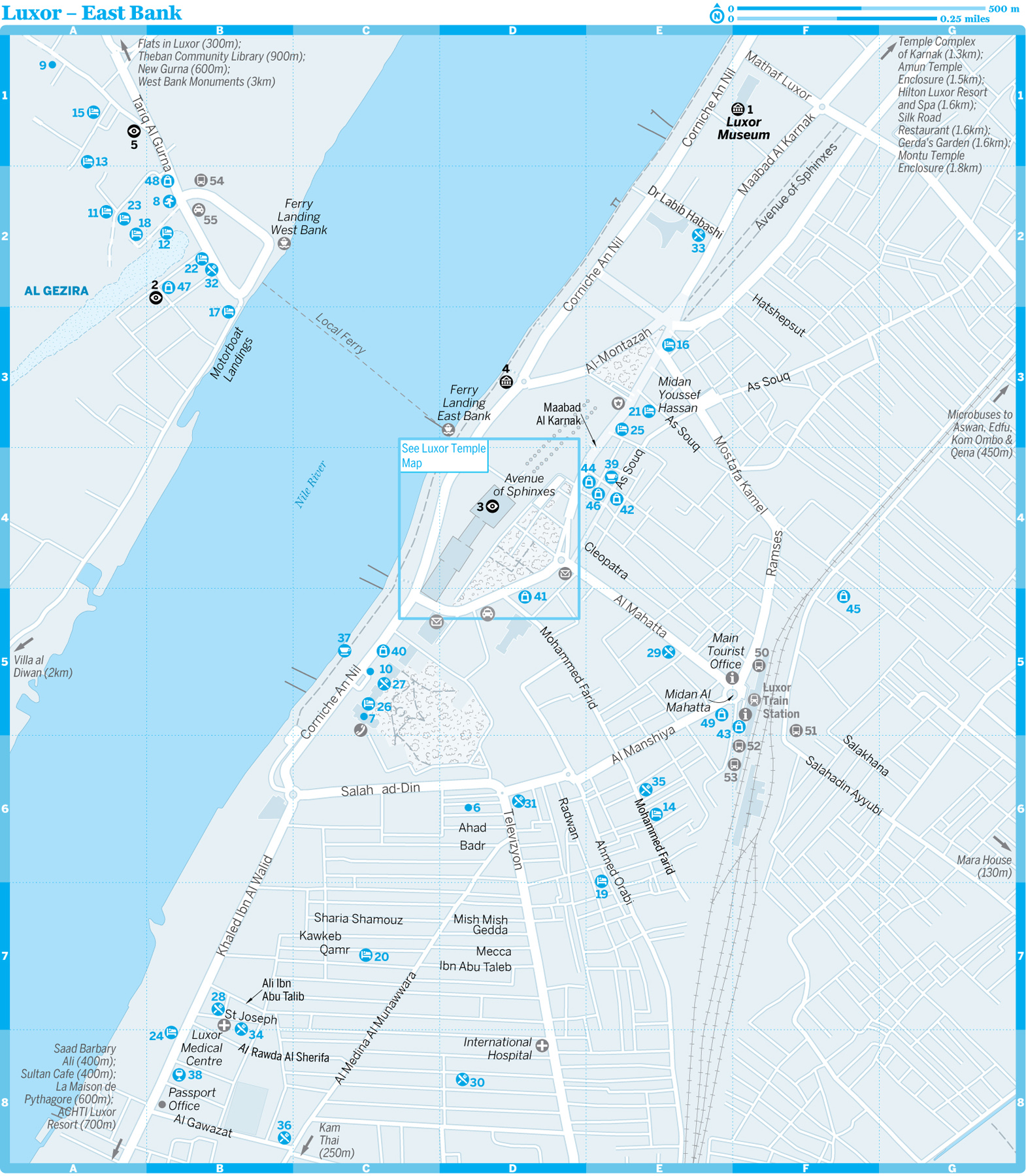

Luxor – East Bank

1Top Sights

1Sights

2Activities, Courses & Tours

4Sleeping

7Shopping

8Information

1East Bank

Karnak

Karnak ( ![]() % 095-238-0270; Sharia Maabad Al Karnak; adult/student LE120/60, incl open-air museum LE150/75;

% 095-238-0270; Sharia Maabad Al Karnak; adult/student LE120/60, incl open-air museum LE150/75; ![]() h 6am-6pm;

h 6am-6pm; ![]() p ) is an extraordinary complex of sanctuaries, kiosks, pylons and obelisks dedicated to the Theban triad but also to the greater glory of the pharaohs. The site covers over 2 sq km; it’s large enough to contain about 10 cathedrals. At its heart is the Temple of Amun, the earthly ‘home’ of the local god. Built, added to, dismantled, restored, enlarged and decorated over nearly 1500 years, Karnak was the most important place of worship in Egypt during the New Kingdom.

p ) is an extraordinary complex of sanctuaries, kiosks, pylons and obelisks dedicated to the Theban triad but also to the greater glory of the pharaohs. The site covers over 2 sq km; it’s large enough to contain about 10 cathedrals. At its heart is the Temple of Amun, the earthly ‘home’ of the local god. Built, added to, dismantled, restored, enlarged and decorated over nearly 1500 years, Karnak was the most important place of worship in Egypt during the New Kingdom.

The complex is dominated by the great Temple of Amun-Ra – one of the world’s largest religious complexes – with its famous hypostyle hall, a spectacular forest of giant papyrus-shaped columns. This main structure is surrounded by the houses of Amun’s wife Mut and their son Khonsu, two other huge temple complexes on this site. On its southern side, the Mut Temple Enclosure was once linked to the main temple by an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes. To the north is the Montu Temple Enclosure, which honoured the local Theban war god. The 3km paved avenue of human-headed sphinxes that once linked the great Temple of Amun at Karnak with Luxor Temple is now again being cleared. Most of what you can see was built by the powerful pharaohs of the 18th to 20th dynasties (1570–1090 BC), who spent fortunes on making their mark in this most sacred of places, which was then called Ipet-Sut, meaning ‘The Most Esteemed of Places’. Later pharaohs extended and rebuilt the complex, as did the Ptolemies and early Christians. The further into the complex you venture, the older the structures. The light is most beautiful in the early morning or later afternoon, and the temple is quieter then, as later in the morning tour buses bring day trippers from Hurghada. It pays to visit more than once, to make sense of the overwhelming jumble of ancient remains.

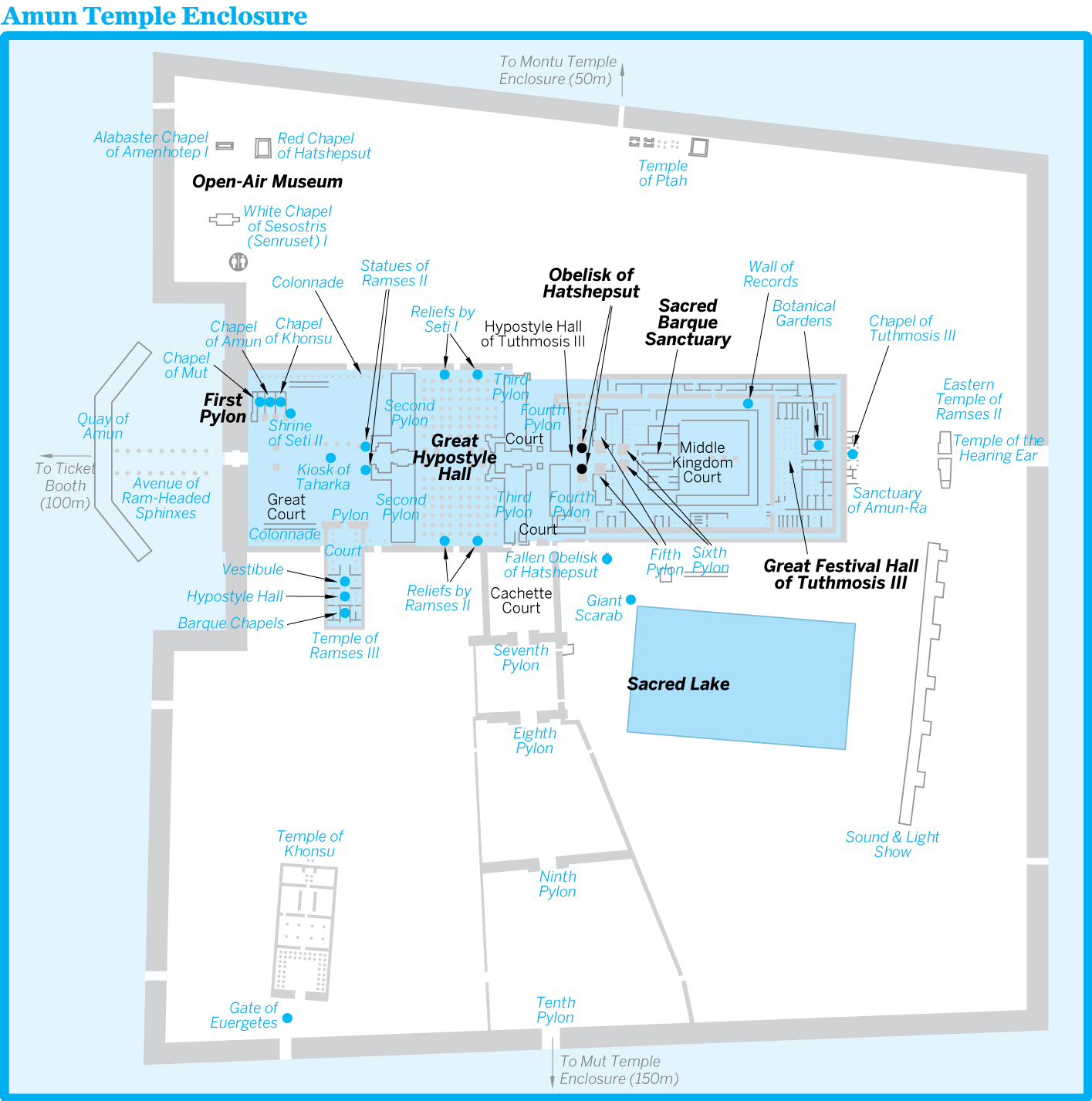

![]() oAmun Temple EnclosureTemple

oAmun Temple EnclosureTemple

Amun-Ra was the local god of Karnak (Luxor) and during the New Kingdom, when the princes of Thebes ruled Egypt, he became the preeminent state god, with a temple that reflected his status. At the height of its power, the temple owned 421,000 head of cattle, 65 cities, 83 ships and 276,400 hectares of agricultural land and had 81,000 people working for it. The shell that remains, sacked by Assyrians and Persians, is still one of the world’s great archaeological sites, grand, beautiful and inspiring.

The Quay of Amun was the dock where the large boats carrying the statues of the gods moored during festivals. From paintings in the tomb of Nakht and elsewhere we know that there were palaces to the north of the quay and that these were surrounded by lush gardens. On the east side, a ramp slopes down to the processional avenue of ram-headed sphinxes. These lead to the massive unfinished first pylon, the last to be built, during the reign of Nectanebo I (30th dynasty). The inner side of the pylon still has the massive mud-brick construction ramp, up which blocks of stone for the pylon were dragged with rollers and ropes. Napoleon’s expedition recorded blocks still on the ramp.

AGreat Court

Behind the first pylon lies the Great Court, the largest area of the Karnak complex. To the left is the Shrine of Seti II, with three small chapels that held the sacred barques (boats) of Mut, Amun and Khonsu during the lead-up to the Opet Festival. In the southeastern corner (far right) is the well-preserved Temple of Ramses III, a miniature version of the pharaoh’s temple at Medinat Habu. The temple plan is simple and classic: pylon, open court, vestibule with four Osirid columns and four columns, hypostyle hall with eight columns and three barque chapels for Amun, Mut and Khonsu. At the centre of the court is a 21m column with a papyrus-shaped capital – the only survivor of ten columns that originally stood here – and a small alabaster altar, all that remains of the Kiosk of Taharka, the 25th-dynasty Nubian pharaoh.

The second pylon was begun by Horemheb, the last 18th-dynasty pharaoh, and continued by Ramses I and Ramses II, who also raised three colossal red-granite statues of himself on either side of the entrance; one is now destroyed.

AGreat Hypostyle Hall

Beyond the second pylon is the extraordinary Great Hypostyle Hall, one of the greatest religious monuments ever built. Covering 5500 sq m – enough space to contain both Rome’s St Peter’s Basilica and London’s St Paul’s Cathedral – the hall is an unforgettable forest of 134 towering stone pillars. Their papyrus shape symbolise a swamp, of which there were so many along the Nile. Ancient Egyptians believed that these plants surrounded the primeval mound on which life was first created. Each summer when the Nile began to flood, this hall and its columns would fill with several feet of water. Originally, the columns would have been brightly painted – some colour remains – and roofed, making it pretty dark away from the lit main axis. The size and grandeur of the pillars and the endless decorations can be overwhelming, so take your time, sit for a while and stare at the dizzying spectacle.

The hall was planned by Ramses I and built by Seti I and Ramses II. Note the difference in quality between the delicate raised relief in the northern part, by Seti I, and the much cruder sunken relief work, added by Ramses II in the southern part of the hall. The cryptic scenes on the inner walls were intended for the priesthood and the royalty who understood the religious context, but the outer walls are easier to comprehend, showing the pharaoh’s military prowess and strength, and his ability to bring order to chaos.

On the back of the third pylon, built by Amenhotep III, to the right the pharaoh is shown sailing the sacred barque during the Opet Festival. Tuthmosis I (1504–1492 BC) created a narrow court between the third and fourth pylons, where four obelisks stood, two each for Tuthmosis I and Tuthmosis III (1479–1425 BC). Only the bases remain except for one, 22m high, raised for Tuthmosis I.

AInner Temple

Beyond the fourth pylon is the Hypostyle Hall of Tuthmosis III built by Tuthmosis I in precious wood, and altered by Tuthmosis III with 14 columns and a stone roof. In this court stands one of the two magnificent 30m-high obelisks erected by Queen Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BC) to the glory of her ‘father’ Amun. The other is broken, but the upper shaft lies near the sacred lake. The Obelisk of Hatshepsut is the tallest in Egypt, its tip originally covered in electrum (a commonly used alloy of gold and silver). After Hatshepsut’s death, her stepson Tuthmosis III eradicated all signs of her reign and had them walled into a sandstone structure.

The ruined fifth pylon, constructed by Tuthmosis I, leads to another colonnade now badly ruined, followed by the small sixth pylon, raised by Tuthmosis III, who also built the pair of red-granite columns in the vestibule beyond, carved with the lotus and the papyrus, the symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt. Nearby, on the left, are two huge statues of Amun and the goddess Amunet, carved in the reign of Tutankhamun.

The original Sanctuary of Amun, the very core of the temple and the place of darkness where the god resided, was built by Tuthmosis III. Destroyed when the temple was sacked by the Persians, it was rebuilt in granite by Alexander the Great’s successor and half-brother, the fragile, dim-witted Philip Arrhidaeus (323–317 BC).

East of the shrine of Philip Arrhidaeus is the oldest-known part of the temple, the Middle Kingdom Court, where Sesostris I built a shrine, of which the foundation walls have been found. On the northern wall of the court is the Wall of Records, a running tally of the organised tribute the pharaoh exacted in honour of Amun from his subjugated lands.

AGreat Festival Hall of Tuthmosis III

At the back of the Middle Kingdom Court is the Great Festival Hall of Tuthmosis III. It is an unusual structure with carved stone columns imitating tent poles, perhaps a reference to the pharaoh’s life under canvas on his frequent military expeditions abroad. The columned vestibule that lies beyond, generally referred to as the Botanical Gardens, has wonderful, detailed relief scenes of the flora and fauna that the pharaoh had encountered during his campaigns in Syria and Palestine, and had brought back to Egypt.

ASecondary Axis of the Amun Temple Enclosure

The courtyard between the Hypostyle Hall and the seventh pylon, built by Tuthmosis III, is known as the cachette court, as thousands of stone and bronze statues were discovered here in 1903. The priests had the old statues and temple furniture they no longer needed buried around 300 BC. Most statues were sent to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, but some remain, standing in front of the seventh pylon, including four of Tuthmosis III on the left.

The well-preserved eighth pylon, built by Queen Hatshepsut, is the oldest part of the north–south axis of the temple, and one of the earliest pylons in Karnak. Carved on it is a text she falsely attributed to Tuthmosis I, justifying her taking the throne of Egypt.

East of the seventh and eighth pylons is the sacred lake, where, according to Herodotus, the priests of Amun bathed twice daily and nightly for ritual purity. On the northwestern side of the lake is part of the Fallen Obelisk of Hatshepsut showing her coronation, and a giant scarab in stone dedicated by Amenhotep III to Khepri, a form of the sun god.

In the southwestern corner of the enclosure is the Temple of Khonsu, god of the moon, and son of Amun and Mut. It can be reached from a door in the southern wall of the Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Amun, via a path through various blocks of stone. The temple, mostly the work of Ramses III and enlarged by later Ramesside rulers, lies north of Euergetes’ Gate and the avenue of sphinxes leading to Luxor Temple. The temple pylon leads via a peristyle court to a hypostyle hall with eight columns carved with figures of Ramses XI and the High Priest Herihor, who effectively ruled Upper Egypt at the time. The next chamber housed the sacred barque of Khonsu.

Mut Temple EnclosureTemple

(adult/student LE40/20)

From the 10th pylon, an avenue of sphinxes leads to the partly excavated southern enclosure – the Precinct of Mut, consort of Amun. The Temple of Mut was built by Amenhotep III and consists of a sanctuary, a hypostyle hall and two courts. It has been restored and officially opened to the public.

Amenhotep also set up more than 700 black granite statues of the lioness goddess Sekhmet, Mut’s northern counterpart, which are believed to form a calendar, with two statues for every day of the year, receiving offerings each morning and evening. The main avenue of sphinxes from Luxor Temple enters the Karnak complex at the front of the Mut Temple.

Montu Temple EnclosureTemple

Inside the Amun Temple Enclosure there is a gate in the northern wall (on your left as you enter) near the Temple of Ptah. The gate, which is usually locked, leads to the Montu Temple Enclosure. Montu, the falcon-headed warrior god, was one of the original deities of Thebes and this temple was one of the original Middle Kingdom structures at Karnak. The ruins that survive were rebuilt by Amenhotep III and modified by others. The complex is very dilapidated.

Open-Air MuseumMuseum

(adult/student LE60/30, incl Amun Temple Enclosure LE150/70; ![]() h6am-5.30pm summer, to 4.30pm winter)

h6am-5.30pm summer, to 4.30pm winter)

Off to the left (north) of the first court of the Amun Temple Enclosure is Karnak’s open-air museum. The word ‘museum’ and the fact that there is so much else to see in Karnak means that most visitors skip this collection of stones, statues and shrines, but it is definitely worth a look.

The well-preserved chapels include the White Chapel of Sesostris I, one of the oldest and most beautiful monuments in Karnak, which has wonderful Middle Kingdom reliefs; the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut, its red quartzite blocks reassembled in 2000; and the Alabaster Chapel of Amenhotep I. The museum also contains a collection of statuary found throughout the temple complex. Buy the combo ticket at the main ticket office.

Luxor Temple & Museums

Luxor TempleTemple

(![]() %095-237-2408; Corniche An Nil; adult/student LE100/50;

%095-237-2408; Corniche An Nil; adult/student LE100/50; ![]() h6am-9pm)

h6am-9pm)

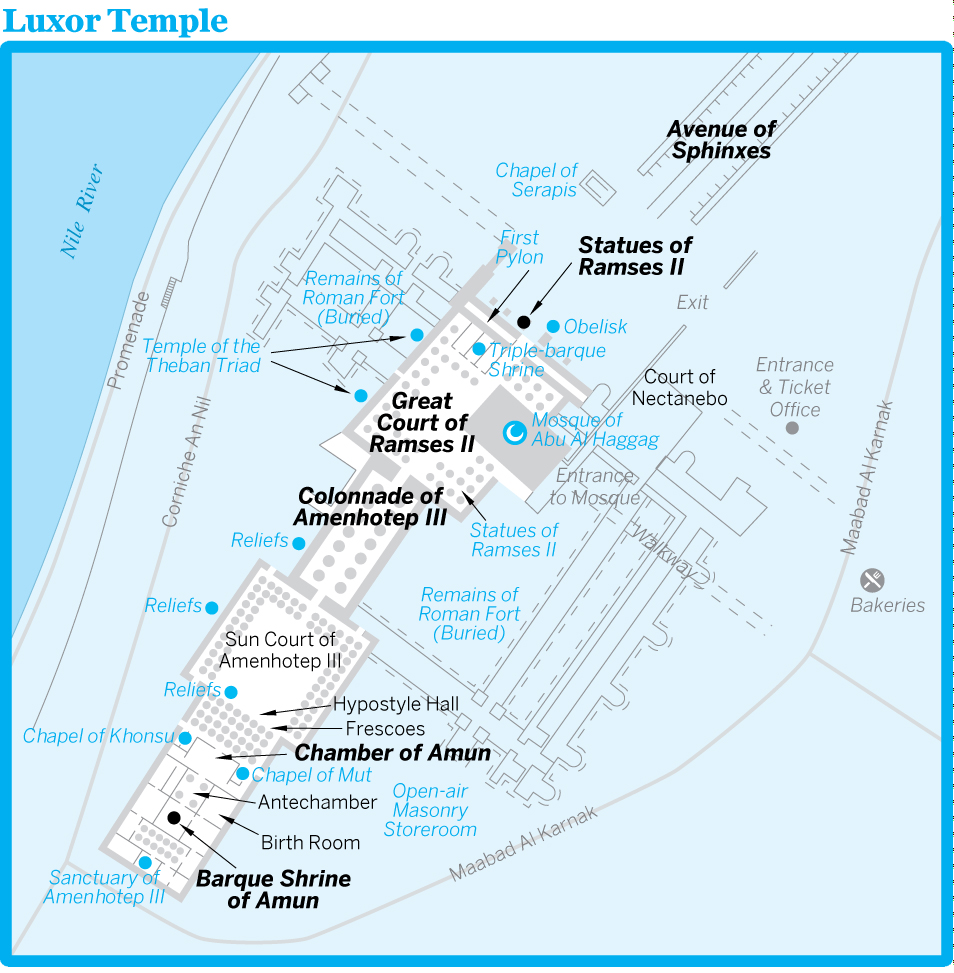

Largely built by the New Kingdom pharaohs Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC) and Ramses II (1279–1213 BC), this temple is a strikingly graceful monument in the heart of the modern town. Also known as the Southern Sanctuary, its main function was during the annual Opet celebrations, when the statues of Amun, Mut and Khonsu were brought from Karnak, along the Avenue of Sphinxes, and reunited here during the inundation.

Visit early when the temple opens, before the crowds arrive, or later at sunset when the stones glow. Whenever you go, be sure to return at night when the temple is lit up, creating an eerie spectacle as shadow and light play off the reliefs and colonnades.

Amenhotep III greatly enlarged an older shrine built by Hatshepsut, and rededicated the massive temple as Amun’s southern ipet (harem), the private quarters of the god. The structure was further added to by Tutankhamun, Ramses II, Alexander the Great and various Romans. The Romans constructed a military fort around the temple that the Arabs later called Al Uqsur (The Fortifications), which was later corrupted to give modern Luxor its name.

In ancient times the temple would have been surrounded by a warren of mud-brick houses, shops and workshops, which now lie under the modern town, but after the decline of the city people moved into the – by then – partly covered temple complex and built their city within it. In the 14th century, a mosque was built in one of the interior courts for the local sheikh (holy man) Abu Al Haggag. Excavation works, begun in 1885, have cleared away the village and debris of centuries to uncover what can be seen of the temple today, but the mosque remains and has been restored after a fire.

The temple is less complex than Karnak, but here again you walk back in time the deeper you go into it. In front of the temple is the beginning of the Avenue of Sphinxes that ran all the way to the temples at Karnak 3km to the north, and is now almost entirely excavated.

The massive 24m-high first pylon was raised by Ramses II and decorated with reliefs of his military exploits, including the Battle of Kadesh. The pylon was originally fronted by six colossal statues of Ramses II, four seated and two standing, but only two of the seated figures and one standing remain. Of the original pair of pink-granite obelisks that stood here, one remains while the other stands in the Place de la Concorde in Paris. Beyond lies the Great Court of Ramses II, surrounded by a double row of columns with lotus-bud capitals, the walls of which are decorated with scenes of the pharaoh making offerings to the gods. On the south (rear) wall is a procession of 17 sons of Ramses II with their names and titles. In the northwestern corner of the court is the earlier triple-barque shrine built by Hatshepsut and usurped by her stepson Tuthmosis III for Amun, Mut and Khonsu. Over the southeastern side hangs the 14th-century Mosque of Abu Al Haggag, dedicated to a local sheikh, entered from Sharia Maabad Al Karnak, outside the temple precinct.

Beyond the court is the older, splendid Colonnade of Amenhotep III, built as the grand entrance to the Temple of Amun of the Opet. The walls behind the elegant open papyrus columns were decorated during the reign of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun and celebrate the return to Theban orthodoxy following the wayward reign of the previous pharaoh, Akhenaten. The Opet Festival is depicted in lively detail, with the pharaoh, nobility and common people joining the triumphal procession. Look out for the drummers and acrobats doing backbends.

South of the Colonnade is the Sun Court of Amenhotep III, once enclosed on three sides by double rows of towering papyrus-bundle columns, the best preserved of which, with their architraves extant, are those on the eastern and western sides. In 1989 workmen found a cache of 26 statues here, buried by priests in Roman times, now displayed in the Luxor Museum.

Beyond lies the Hypostyle Hall, the first room of the original Opet temple, with four rows of eight columns each, leading to the temple’s main rooms. The central chamber on the axis south of the Hypostyle Hall was the cult sanctuary of Amun, stuccoed over by the Romans in the 3rd century AD and painted with scenes of Roman officials: some of this is still intact and vivid. Through this chamber, either side of which are chapels dedicated to Mut and Khonsu, is the four-columned antechamber where offerings were made to Amun. Immediately behind the chamber is the Barque Shrine of Amun, rebuilt by Alexander the Great, with reliefs portraying him as an Egyptian pharaoh.

To the east a doorway leads into two rooms. The first is Amenhotep III’s ‘birth room’ with scenes of his symbolic divine birth. You can see the moment of his conception, when the fingers of the god touch those of the queen and ‘his dew filled her body’, according to the accompanying hieroglyphic caption. The Sanctuary of Amenhotep III is the last chamber; it still has the remains of the stone base on which Amun’s statue stood, and although it was once the most sacred part of the temple, the busy street that now runs directly behind it makes it less atmospheric.

![]() oLuxor MuseumMuseum

oLuxor MuseumMuseum

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; Corniche An Nil; adult/student LE120/60; ![]() h 9am-2pm & 5-9pm)

h 9am-2pm & 5-9pm)

This wonderful museum has a well-chosen and brilliantly displayed and explained collection of antiquities dating from the end of the Old Kingdom right through to the Mamluk period, mostly gathered from the Theban temples and necropolis. The ticket price puts off many, but don’t let that stop you: this is one of the most rewarding sights in Luxor and one of the best museums in Egypt.

The ground-floor gallery has several masterpieces, including a well-preserved limestone relief of Tuthmosis III (No 140), an exquisitely carved statue of Tuthmosis III in greywacke from the Temple of Karnak (No 2), an alabaster figure of Amenhotep III protected by the great crocodile god Sobek (No 155), and one of the few examples of Old Kingdom art found at Thebes, a relief of Unas-ankh (No 183), found in his tomb on the west bank.

A new wing was opened in 2004, dedicated to the glory of Thebes during the New Kingdom period. The highlight, and the main reason for the new construction, is the two royal mummies, Ahmose I (founder of the 18th dynasty) and the mummy some believe to be Ramses I (founder of the 19th dynasty and father of Seti I), beautifully displayed without their wrappings in dark rooms. Other well-labelled displays illustrate the military might of Thebes during the New Kingdom, the age of Egypt’s empire-building, including chariots and weapons. On the upper floor the military theme is diluted with scenes from daily life showing the technology used in the New Kingdom. Multimedia displays show workers harvesting papyrus and processing it into sheets to be used for writing. Young boys are shown learning to read and write hieroglyphs beside a display of a scribe’s implements and an architect’s tools.

Back in the old building, moving up via the ramp to the 1st floor, you come face-to-face with a seated granite figure of the legendary scribe Amenhotep (No 4), son of Hapu, the great official eventually deified in Ptolemaic times and who, as overseer of all the pharaoh’s works under Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC), was responsible for many of Thebes’ greatest buildings. One of the most interesting exhibits is the Wall of Akhenaten, a series of small sandstone blocks named talatat (threes) by workmen – probably because their height and length was about three hand lengths – that came from Amenhotep IV’s contribution at Karnak before he changed his name to Akhenaten and left Thebes for Tell Al Amarna. His building was demolished and about 40,000 blocks used to fill in Karnak’s ninth pylon were found in the late 1960s and partially reassembled here. The scenes showing Akhenaten, his wife Nefertiti and temple life are a rare example of decoration from a temple of Aten. Further highlights are treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb, including shabti (servant) figures, model boats, sandals, arrows and a series of gilded bronze rosettes from his funeral pall.

A ramp back down to the ground floor leaves you close to the exit and beside a black-and-gold wooden head of the cow deity Mehit-Weret, an aspect of the goddess Hathor, which was also found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

On the left just before the exit is a small hall containing 16 of 22 statues that were uncovered in Luxor Temple in 1989. All are magnificent examples of ancient Egyptian sculpture, but pride of place at the end of the hall is given to an almost pristine 2.45m-tall quartzite statue of a muscular Amenhotep III, wearing a pleated kilt.

Mummification MuseumMuseum

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; Corniche An Nil; adult/student LE80/40; ![]() h 9am-2pm)

h 9am-2pm)

Housed in the former visitors centre on Luxor’s corniche, the Mummification Museum has well-presented exhibits explaining the art of mummification. The museum is small and some may find the entrance fee overpriced. Also, although it should be open throughout the day, a lack of visitors means that it sometimes closes for several hours after midday.

On display are the well-preserved mummy of a 21st-dynasty high priest of Amun, Maserharti, and a host of mummified animals. Vitrines show the tools and materials used in the mummification process – check out the small spoon and metal spatula used for scraping the brain out of the skull. Several artefacts that were crucial to the mummy’s journey to the afterlife have also been included, as well as some picturesque painted coffins. Presiding over the entrance is a beautiful little statue of the jackal god, Anubis, the god of embalming who helped Isis turn her brother-husband Osiris into the first mummy.

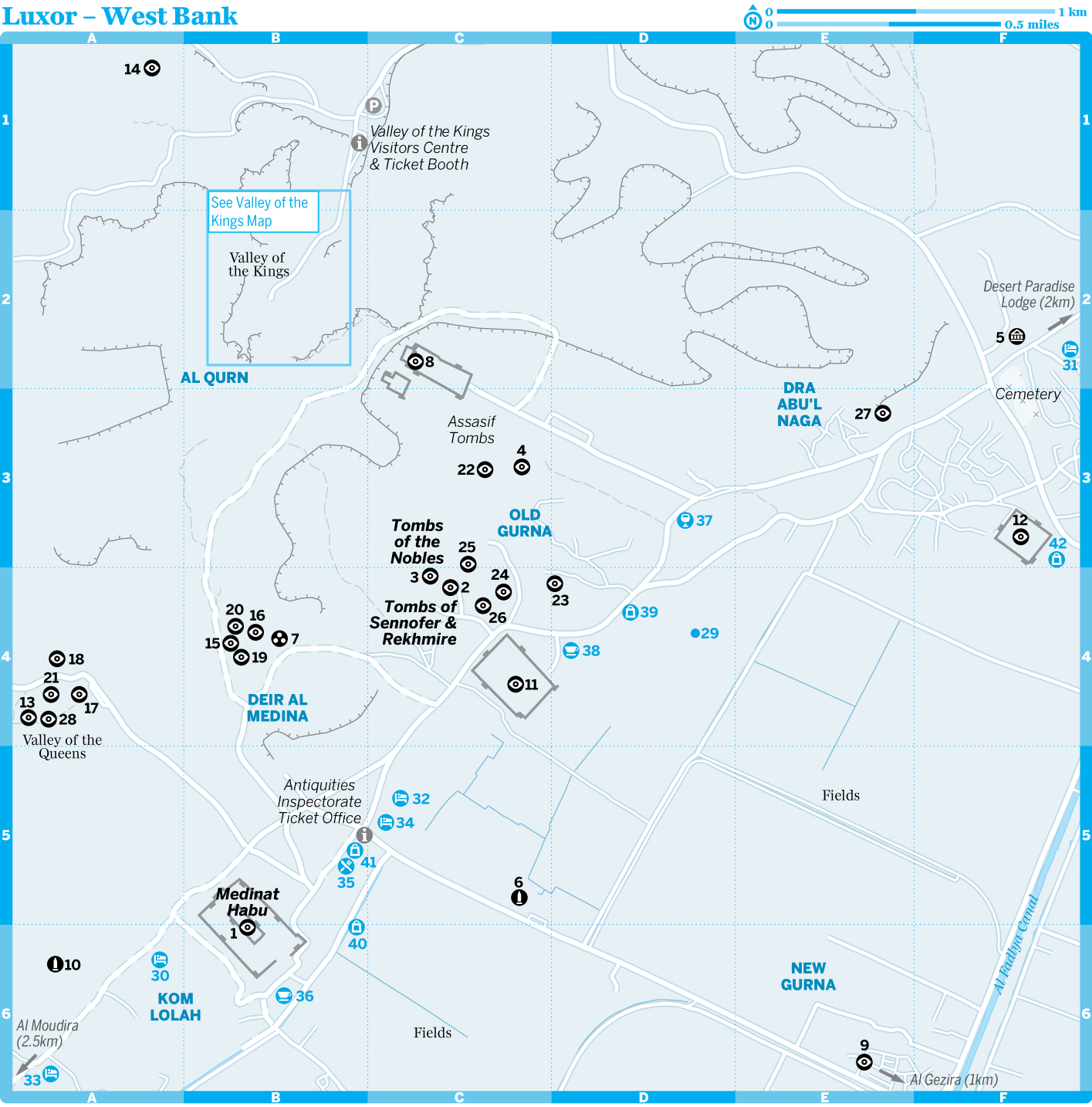

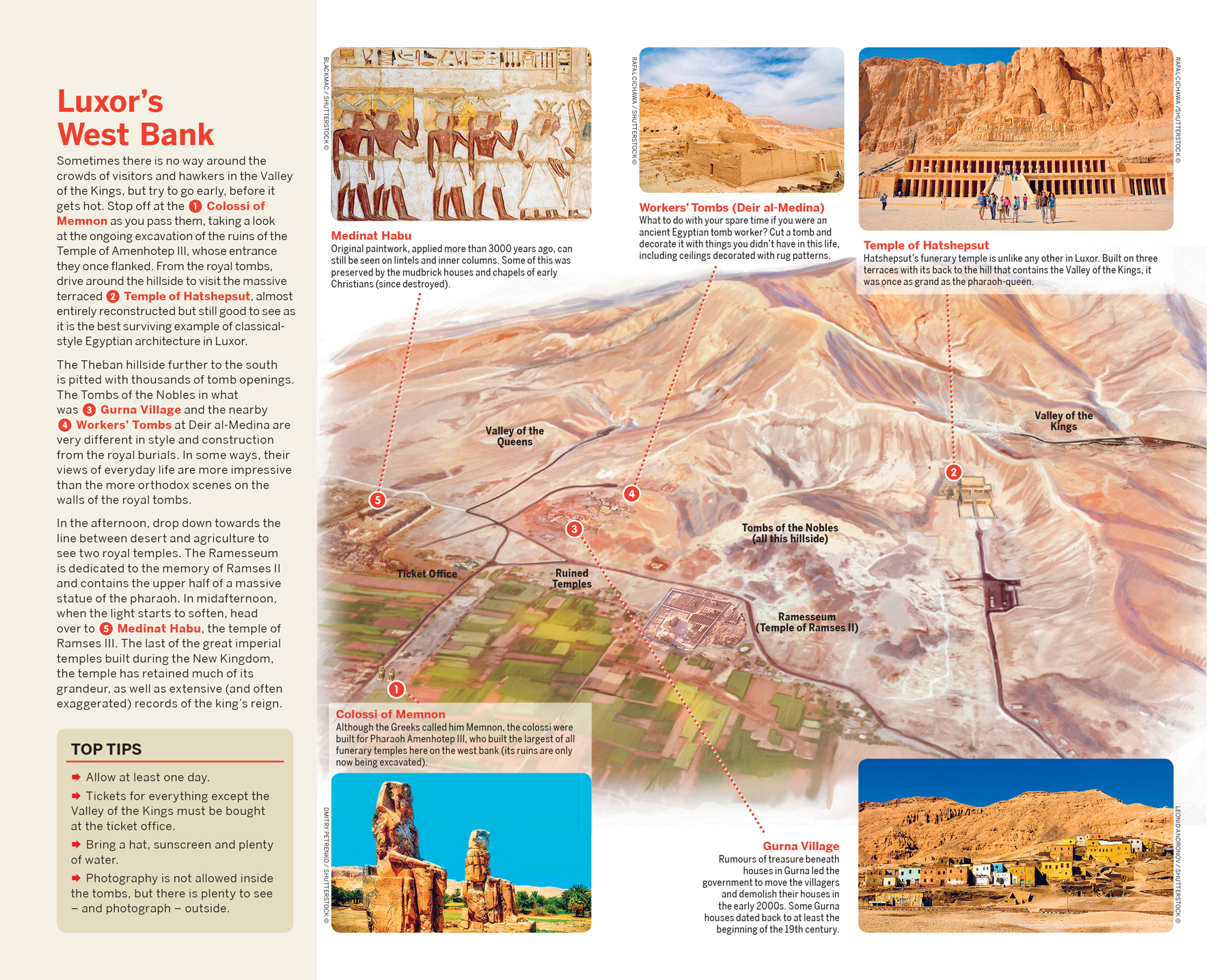

Luxor – West Bank

1West Bank

The West Bank (illustration) is a world away from the noise and bustle of Luxor town on the east bank. Taking a taxi across the bridge, 6km south of the centre, or crossing on the old ferry, you are immediately in lush countryside, with bright-green sugarcane fields along irrigation canals and clusters of colourful houses, all against the background of the desert and the Theban hills. Coming towards the end of the cultivated land, you start to notice huge sandstone blocks lying in the middle of fields, gaping black holes in the rocks and giant sandstone forms on the edge of the cultivation below. Magnificent memorial temples were built on the flood plains here, where the pharaoh’s cult could be perpetuated by the devotions of his priests and subjects, while his body and worldly wealth, and the bodies of his wives and children, were laid in splendidly decorated tombs hidden in the hills.

From the New Kingdom onwards, the necropolis also supported a large living population of artisans, labourers, temple priests and guards, who devoted their lives to the construction and maintenance of this city of the dead, and who protected the tombs full of treasure from eager robbers. The artisans perfected the techniques of tomb building, decoration and concealment, and passed the secrets down through their families. They all built their own tombs here.

Until a generation ago, villagers used tombs to shelter from the extremes of the desert climate and, until recently, many lived in houses built over the Tombs of the Nobles. These beautifully painted houses were a picturesque sight to anyone visiting the west bank. However, over the past 100 years or so the Supreme Council of Antiquities has been trying to relocate the inhabitants of Al Gurna. In 2007, their houses were demolished, and the families were moved to a huge new village of small breeze-block houses 8km north of the Valley of the Kings. A few houses have been left standing, although it has not been decided what use they should be put to.

LUXOR IN…

Two Days

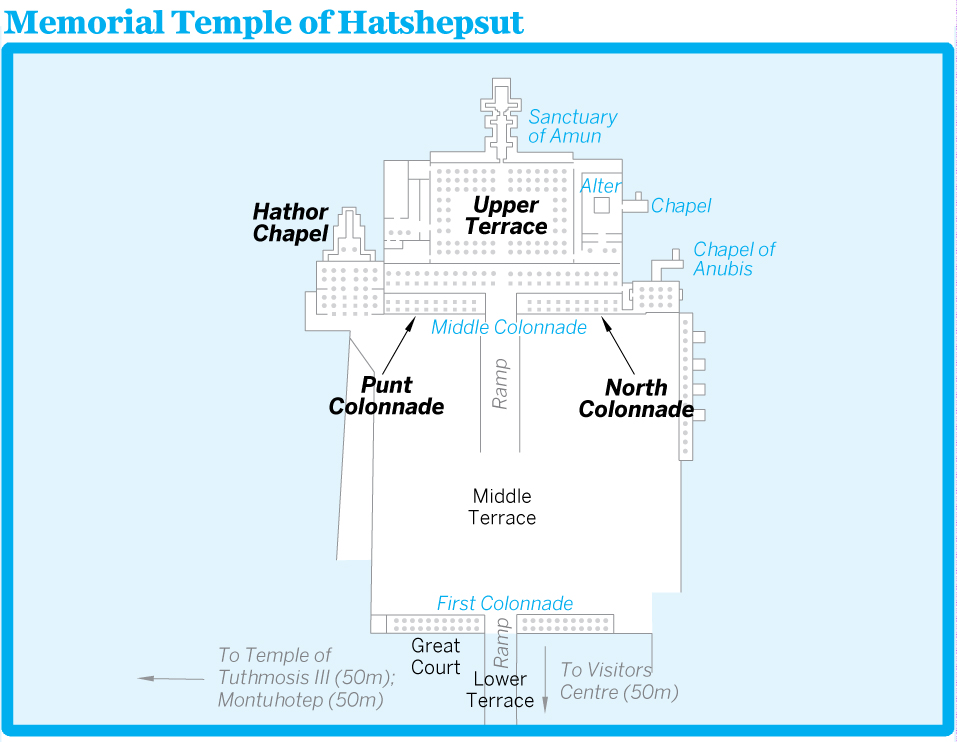

If you’ve only got two days in Luxor, your schedule will be full on. Start the first day on the east bank with an early morning visit to the Temples of Karnak. After Karnak stroll along the corniche to the Luxor Museum. After a late lunch at Sofra, visit Luxor Temple in the golden glow of the afternoon. Return after dinner to see the temple floodlit. The next day take a taxi for a day to the west bank, starting early again to avoid the crowds at the Valley of the Kings. On the way back visit Howard Carter’s House, with its brilliant replica of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, and the Memorial Temple of Hatshepsut. After lunch visit the Tombs of the Nobles, or the wonderful temple of Ramses III at Medinat Habu.

Four Days

Four days allows for a more leisurely schedule. On the west bank, you could visit the Tombs of the Nobles, the Ramesseum and the Temple of Seti I, and on the last day revisit Karnak in the morning and cross the river to see the ancient workers’ village and tombs at Deir Al Medina. Alternatively you could make a day-trip to the amazing temples of Dendara and Abydos.

Tickets

The Antiquities Inspectorate ticket office (MAP GOOGLE MAP; main road, 3km inland from ferry landing; ![]() h

6am-5pm), beyond the Colossi of Memnon, sells tickets to most sites except for the Temple at Deir Al Bahri, the Assasif Tombs (available at Deir Al Bahri ticket office), the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. Check here first to see which tickets are available, and which tombs are open. All sites are officially open from 6am to 5pm.

h

6am-5pm), beyond the Colossi of Memnon, sells tickets to most sites except for the Temple at Deir Al Bahri, the Assasif Tombs (available at Deir Al Bahri ticket office), the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. Check here first to see which tickets are available, and which tombs are open. All sites are officially open from 6am to 5pm.

Photography is not permitted in any tombs, and guards may confiscate film or memory cards. Alternatively, they might see you using a camera or phone as an opportunity to extract some extra cash. Tickets are valid only for the day of purchase, and no refunds are given.

Gezira Village to Ticket Office

Art from People to PeopleArts Centre

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; ![]() % 095-231-5529, 012-2079-7310; https://art-frompeople.com; Gezira;

% 095-231-5529, 012-2079-7310; https://art-frompeople.com; Gezira; ![]() h 4-8pm Sat, Mon & Thu)

h 4-8pm Sat, Mon & Thu)

A new venture in Luxor, this art gallery and centre is located in a small place behind the Nile Valley Hotel. Run by Eiad Oraby, it showcases local artists as well as holding art classes and events for kids, providing a much-needed creative hub.

Theban Community LibraryLibrary

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; ![]() % 010-0523-8113; www.tmp-library.org; near New Gourna;

% 010-0523-8113; www.tmp-library.org; near New Gourna; ![]() h 3.30-8.30pm;

h 3.30-8.30pm; ![]() c )

c ) ![]() F

F

The latest project from Professor Kent Weeks and the Theban Mapping Project is the first open library in Luxor, a free service with general books in Arabic and English, and a good collection on archaeology and issues related to conservation. There are regular evening lectures. More information is available from the librarian, Ahmed Hassan, or via their website or Facebook page.

Open to all, the library is used by local archaeologists and guides, school children (there is no other library that serves them) and people from the villages. The latest additions include books on diet and prenatal care for local mothers. The library is self-funding and welcomes donations.

New GurnaVillage

Hassan Fathy’s mud-brick village lies just past the railway track on the road from the ferry to the Antiquities Inspectorate ticket office. Although built between 1946 and 1952 to rehouse the inhabitants of Old Gurna, who lived above and around the Tombs of the Nobles, the village became a showcase of utilitarian mud-brick design. The stunning buildings had Hassan Fathy’s signature domes and vaults, thick mud-brick walls and natural ventilation.

The project failed in its original intention because most inhabitants of Old Gurna refused to move into the new houses, unhappy at the idea of being moved from their old homes and their livelihoods, which some claim was selling trinkets to tourists and others claim was digging up treasures from the ancient burials beneath the houses. Today much of Fathy’s work is in tatters, the original houses increasingly replaced with breeze block, although the beautiful mud-brick mosque and theatre survive. Unesco has recognised the need to safeguard the village, but its plans have stalled. A short film about the village is available at https://vimeo.com/15514401.

Colossi of MemnonMonument

(MAP GOOGLE MAP) ![]() F

F

The two faceless Colossi of Memnon, originally representing Pharaoh Amenhotep III, rising majestically about 18m from the plain, are the first monuments tourists see when they visit the west bank. These magnificent colossi, each cut from a single block of stone and weighing 1000 tonnes, sat at the eastern entrance to the funerary temple of Amenophis III, the largest on the west bank. Egyptologists are currently excavating the temple and their discoveries can be seen behind the colossi.

The colossi were already a great tourist attraction during Graeco-Roman times, when the statues were attributed to Memnon, the legendary African king who was slain by Achilles during the Trojan War. The Greeks and Romans considered it good luck to hear the whistling sound emitted by the northern statue at sunrise, which they believed to be the cry of Memnon greeting his mother Eos, the goddess of dawn. She in turn would weep tears of dew for his untimely death. All this was probably due to a crack in the colossus’ upper body, which appeared after the 27 BC earthquake. As the heat of the morning sun baked the dew-soaked stone, sand particles would break off and resonate inside the cracks in the structure. After Septimus Severus (193–211 AD) repaired the statue in the 3rd century AD, Memnon’s plaintive greeting was heard no more.

The colossi are just off the road, before you reach the Antiquities Inspectorate ticket office, and are usually being snapped and filmed by an army of tourists. Yet few visitors have any idea that these giant enthroned figures are set in front of the main entrance to an equally impressive funerary temple, the largest in Egypt, the remains of which are slowly being brought to light.

Some tiny parts of the temple that stood behind the colossi remain and more is being uncovered now that the excavation is underway. Many statues, among them the huge dyad of Amenhotep III and his wife Tiye that now dominates the central court of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, were later dragged off by other pharaohs, but much still remains beneath the silt. A stele, also now in the Egyptian Museum, describes the temple as being built from ‘white sandstone, with gold throughout, a floor covered with silver, and doors covered with electrum’. No gold or silver has yet been found, but if you wander behind the colossi, you can see the huge area littered with statues and masonry that had long lain under the ground.

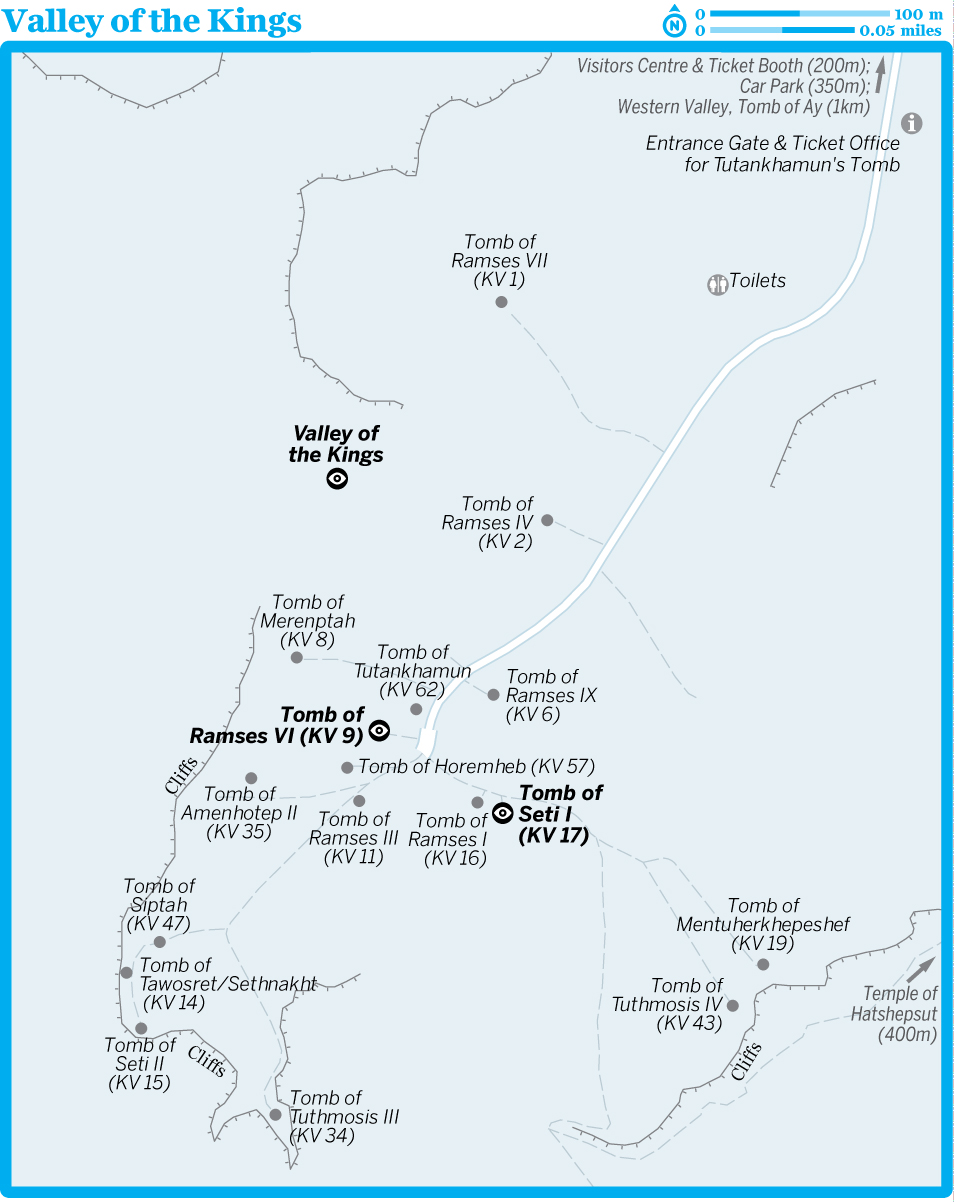

Valley of the Kings

The west bank of Luxor had been the site of royal burials since around 2100 BC, but it was the pharaohs of the New Kingdom period (1550–1069 BC) who chose this isolated valley dominated by the pyramid-shaped mountain peak of Al Qurn (The Horn). Once called the Great Necropolis of Millions of Years of Pharaoh, or the Place of Truth, the Valley of the Kings (Wadi Biban Al Muluk; MAP; www.thebanmappingproject.com; adult/student for 3 tombs LE160/80; ![]() h

6am-5pm, last ticket sold at 4pm) has 63 magnificent royal tombs.

h

6am-5pm, last ticket sold at 4pm) has 63 magnificent royal tombs.

The tombs have suffered greatly from treasure hunters, floods and, in recent years, mass tourism: carbon dioxide, friction and the humidity produced by the average 2.8g of sweat left by each visitor have affected the reliefs and the stability of paintings that were made on plaster laid over limestone. The Department of Antiquities has installed dehumidifiers and glass screens in the worst-affected tombs. They have also introduced a rotation system: a limited number of tombs are open to the public at any one time. The entry ticket gains access to three tombs, with extra tickets to see the tombs of Ay, Tutankhamun, Seti I and Ramses VI.

The road into the Valley of the Kings is a gradual, dry, hot climb, so be prepared, especially if you are riding a bicycle. Also be ready to run the gauntlet of the tourist bazaar, which sells soft drinks, ice creams and snacks alongside the tat. The air-conditioned Valley of the Kings Visitors Centre & Ticket Booth (MAP) has a good model of the valley, a movie about Carter’s discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun and toilets (there are Portakabins higher up, but this is the one to use). A tuf-tuf (a little electrical train) ferries visitors between the visitors centre and the tombs (it can be hot during summer). The ride costs LE4. It’s worth having a torch to illuminate badly lit areas but you cannot take a camera – photography is forbidden in all tombs.

The best source of information about the tombs, including detailed descriptions of their decoration and history, can be found on the Theban Mapping Project website. Some tombs have additional entry fees and tickets.

Highlights include the Tomb of Ay, Tomb of Horemheb (KV 57), Tomb of Ramses III (KV 11), Tomb of Ramses VI (KV 9) and Tomb of Seti I (KV 17).

Tomb of Ramses VII (KV 1)Tomb

Near the main entrance is the small, unfinished tomb of Ramses VII (1136–1129 BC). Only 44m long – short for a royal tomb because of Ramses’ sudden death – it consists of a corridor, a burial chamber and an unfinished third chamber. His architects hastily widened what was to have been the tomb’s second corridor, making it a burial chamber, and the pharaoh was laid to rest in a pit covered with a sarcophagus lid.

Niches for Canopic jars are carved into the pit’s sides, a feature unique to this tomb. Walls on the corridor leading to the chamber are decorated with fairly well preserved excerpts from the Book of Caverns and the Opening of the Mouth ritual, while the burial chamber is decorated with passages from the Book of the Earth. It was later used by Coptic hermits, as their graffiti suggests.

WHAT TO BRING

When visiting the west bank sights, bring plenty of water (it is available at some sights, but you should overestimate the amount you will need). A sun hat, sunglasses and sun protector are also essential. Small change for baksheesh is much needed, as guardians rely on tips to augment their pathetic salaries; LE10 or LE20 for each should be enough for them to either leave you in peace, or to open a door or reflect light on a particularly beautiful painting. A torch (flashlight) can come in handy.

Tomb of Ramses IV (KV 2)Tomb

Originally intended to be much larger, KV 2 was cut short at 89m on the early death of the pharaoh (1147 BC) and a pillared hall was converted to be the burial chamber. The sarcophagus is in place with a magnificent goddess Nut filling the ceiling above it. Close to the entrance of the valley, this tomb was opened in antiquity and inhabited (there is Greek, Roman and Coptic graffiti), and used as a hotel by many 18th- and 19th-century visitors.

The paintings in the burial chamber have deteriorated, but there is a wonderful image of the goddess Nut, stretched across the blue ceiling, and it is the only tomb to contain the text of the Book of Nut, with a description of the path taken by the sun every day. The red-granite sarcophagus, though empty, is one of the largest in the valley. The discovery of an ancient plan of the tomb on papyrus (now in the Turin Museum) shows the sarcophagus was originally enclosed by four large shrines similar to those in Tutankhamun’s tomb. The mummy of Ramses IV was later reburied in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35), and is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

KV 5: THE GREATEST FIND SINCE TUTANKHAMUN

In 1995 American archaeologist Dr Kent Weeks discovered the largest tomb in Egypt, believed to be the burial place of the many sons of Ramses II. It was immediately hailed as the greatest find since that of Tutankhamun, or as one London newspaper put it: ‘The Mummy of all Tombs’.

In 1987 Weeks had located the entrance to tomb KV 5, which James Burton Carter had uncovered in the 1820s but had thought was a small tomb as it was filled with silt and sand. The entrance to the tomb was then lost beneath debris from other excavations. When Weeks and his team cleared the entrance chambers, they found pottery, fragments of sarcophagi and wall decorations, which led the professor to believe it was the tomb of the Sons of Ramses II.

Then, in 1995, Weeks unearthed a doorway leading to an incredible 121 chambers and corridors, making the tomb many times larger and more complex than any other found in Egypt. One chamber has 16 pillars, more than any other in the Valley of the Kings. Clearing the debris from this unique and enormous tomb has been a painstaking and dangerous task. Not only does every bucketful have to be sifted for fragments of pottery, bone and reliefs, but major engineering work had to be done to shore up the structure of the 440m-long tomb. Progress is slow, but Weeks speculates that it has as many as 150 chambers. The excavation can be followed on the excellent website www.thebanmappingproject.com.

Tomb of Ramses IX (KV 6)Tomb

Only half decorated at the time of the king’s death and open since antiquity, this is not the most interesting tomb in the valley, but it is one the most popular because it has a very gently shelving shaft and is near the entrance to the valley. Its large antechamber is decorated with animals, serpents and demons from the Book of the Dead. There is also a pillared hall and short hallway before the burial chamber.

On either side of the gate on the rear wall are two figures of priests, both dressed in panther-skin robes and sporting a ceremonial sidelock. The walls of the burial chamber feature the Book of Amduat, the Book of Caverns and the Book of the Earth; the Book of the Heavens is represented on the ceiling. Although it is unfinished, it was the last tomb in the valley to have so much of its decoration completed, and the paintings are relatively well preserved.

Tomb of Merenptah (KV 8)Tomb

The second-largest tomb in the valley, Merenptah’s tomb has been open since antiquity and has its share of Greek and Coptic graffiti. Floods have damaged the lower part of the walls of the long tunnel-like tomb, but the upper parts have well-preserved reliefs. The corridors are decorated with the Book of the Dead, the Book of Gates and the Book of Amduat. Beyond a shaft is a false burial chamber with two pillars decorated with the Book of Gates.

Ramses II lived for so long that 12 of his sons died before he did, so it was finally his 13th son, Merenptah (1213–1203 BC), who succeeded him in his 60s. The pharaoh was originally buried inside four stone sarcophagi: three of granite (the lid of the second is still in situ, with an effigy of Merenptah on top), and the fourth and innermost of alabaster. In a rare mistake by ancient Egyptian engineers, the outer sarcophagus did not fit through the tomb entrance and its gates had to be hacked away. Much of the decoration in the burial chamber has faded, but it remains an impressive room, with a sunken floor and brick niches on the front and rear walls.

DON’T MISS

The Best Tombs

With so many tombs to choose from, these are the highlights of the Theban necropolis:

Deir Al Medina

Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV 62)Tomb

(MAP; Valley of the Kings; adult/student LE200/100, plus Valley of the Kings ticket; ![]() h 6am-5pm)

h 6am-5pm)

The story of the celebrated discovery of the famous tomb and all the fabulous treasures it contained far outshines the reality of the small tomb of a short-lived pharaoh. Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of the least impressive in the valley and bears all the signs of a rather hasty completion and inglorious burial, as well as significant damage to the decorations. In spite of this and of the existence of a more instructive replica, many people choose to visit.

The Egyptologist Howard Carter slaved away for six seasons in the valley and in the end was rewarded with the discovery of the resting place of Tutankhamun, with all its treasures, the most impressive haul ever made in Egypt. The first step was found on 4 November 1922, and on 5 November the rest of the steps and a sealed doorway came to light. Carter wired Lord Carnarvon to join him in Egypt immediately for the opening of what he hoped was the completely intact tomb of Tutankhamun. When he looked inside, he saw what he famously described as ‘wonderful things’.

The son of Akhenaten and one of Akhenaten’s sisters, Tutankhamun ruled briefly (1336–1327 BC) and died young, with no great battles or buildings to his credit, so there was little time to build a tomb. The tomb had been partially robbed twice in antiquity, but its priceless cache of treasures vindicated Carter’s dream beyond even his wildest imaginings. Four chambers were crammed with jewellery, furniture, statues, chariots, musical instruments, weapons, boxes, jars and food. Even the later discovery that many had been stuffed haphazardly into the wrong boxes by necropolis officials ‘tidying up’ after the ancient robberies does not detract from their dazzling wealth. Some archaeologists believe that Tutankhamun was perhaps buried with all the regalia of the unpopular Amarna royal line, as some of it is inscribed with the names of his father Akhenaten and the mysterious Smenkhkare (1388–1336 BC), who some Egyptologists believe was Nefertiti ruling as pharaoh.

Most of the treasure is in the Cairo Museum, with a few pieces in Luxor Museum: only Tutankhamun’s mummy in its gilded wooden coffin and his sarcophagus are in situ. The burial chamber walls are decorated by chubby figures of the pharaoh before the gods, painted against a yellow-gold background. The wall at the foot end of the sarcophagus shows scenes of the pharaoh’s funeral; the 12 squatting apes from the Book of Amduat, representing the 12 hours of the night, are featured on the opposite wall.

The extra ticket needed to enter the tomb can be bought at the Entrance Gate & Ticket Office for Tutankhamun’s Tomb (MAP).

An exact replica of the tomb and sacrophagus, as well as a full explanation of the rediscovery of the tomb, has been installed in the grounds of Howard Carter’s house.

Work was underway at the time of writing to determine whether there is another chamber beyond the back wall of the burial chamber: Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves has suggested that the tomb might originally have been used to bury Nefertiti, whose remains – and perhaps her treasure – might lie beyond the wall.

![]() oTomb of Ramses VI (KV 9)Tomb

oTomb of Ramses VI (KV 9)Tomb

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; Valley of the Kings; adult/student LE80/40, plus Valley of the Kings ticket; ![]() h 6am-5pm)

h 6am-5pm)

With some of the broadest corridors, longest shafts (117m) and greatest variety of decoration, KV 9 is one of the most spectacular tombs in the valley. Started by Ramses V and finished by Ramses VI, it is a feast for the eyes, much of its surface covered with intact hieroglyphs and paintings. The burial chamber has an unfinished pit in the floor and a magnificent figure of Nut and scenes from the Book of the Day and Book of the Night.

Tutankhamun’s tomb remained intact until 1922 largely thanks to the existence of the neighbouring tomb of Ramses VI, which acted as an unwitting cloak for the older tomb’s entrance. KV 9 was begun for the ephemeral Ramses V (1147–1143 BC) and continued by Ramses VI (1143–1136 BC), with both pharaohs apparently buried here; the names and titles of Ramses V still appear in the first half of the tomb. Following the tomb’s ransacking a mere 20 years after burial, the mummies of both Ramses V and Ramses VI were moved to Amenhotep II’s tomb where they were found in 1898 and taken to Cairo.

Although the tomb’s plastering was not finished, its fine decoration is well preserved, with an emphasis on astronomical scenes and texts. Extracts from the Book of Gates and the Book of Caverns cover the entrance corridor. These continue into the midsection of the tomb and well room, with the addition of the Book of the Heavens. Nearer the burial chamber the walls are adorned with extracts from the Book of Amduat. The burial chamber itself is beautifully decorated, with a superb double image of Nut framing the Book of the Day and Book of the Night on the ceiling. This nocturnal landscape in black and gold shows the sky goddess swallowing the sun each evening to give birth to it each morning in an endless cycle of new life designed to revive the souls of the dead pharaohs. The walls of the chamber are filled with fine images of Ramses VI with various deities, as well as scenes from the Book of the Earth, showing the sun god’s progress through the night, the gods who help him and the forces of darkness trying to stop him reaching the dawn. Look out for the decapitated kneeling figures of the sun god’s enemies around the base of the chamber walls and the black-coloured executioners who turn the decapitated bodies upside down to render them as helpless as possible.

Tomb of Ramses III (KV 11)Tomb

One of the most popular tombs in the valley, KV 11 is also one of the most interesting and best preserved. Originally started by Sethnakht (1186–1184 BC), the project was abandoned when workers hit the shaft of another tomb (KV10). Work resumed under Ramses III (1184–1153 BC), the last of Egypt’s warrior pharaohs, with the corridor turning to the right, then left. It continues deep (125m overall) into the mountain and opens into a magnificent eight-pillared burial chamber.

The wonderful decorations include colourful painted sunken reliefs featuring the traditional ritual texts (Litany of Ra, Book of Gates etc) and Ramses before the gods. Unusual here are the secular scenes, in the small side rooms of the entrance corridor, showing foreign tributes, such as highly detailed pottery imported from the Aegean, the royal armoury, boats and, in the last of these side chambers, the blind harpists that gave the tomb one of its alternative names: ‘Tomb of the Harpers’. When the Scottish traveller James Bruce included a copy of this image in his Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, he was laughed out of London after its publication in 1790.

In the chamber beyond is an aborted tunnel where ancient builders ran into the neighbouring tomb. They shifted the axis of the tomb to the west and built a corridor leading to a pillared hall, with walls decorated with scenes from the Book of Gates. There is also ancient graffiti on the rear right pillar describing the reburial of the pharaoh during the 21st dynasty (1069–945 BC). The remainder of the tomb is only partially excavated and structurally weak.

Ramses III’s sarcophagus is in the Louvre in Paris, its detailed lid is in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and his mummy – found in the Deir Al Bahri cache – is now in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. It was the model for Boris Karloff’s character in the 1930s film The Mummy.

Tomb of Horemheb (KV 57)Tomb

Horemheb was Tutankhamun’s general, who succeeded Ay, Tutankhamun’s briefly reigning tutor. His tomb has beautiful decoration that shows the first use of bas-relief in the valley. This was also the first time the Book of Gates was used to decorate a tomb in the burial chamber. Some 128m long and very steep, this was also the first tomb to run straight and not have a right-angle bend. Horemheb, who was not of royal birth, ruled for 28 years and restored the cult of Amun.

This tomb was discovered filled with ransacked pieces of the royal funerary equipment, including a number of wooden figurines that were taken to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Horemheb (1323–1295 BC) brought stability after the turmoil of Akhenaten’s reign. He had already built a lavish tomb in Saqqara, but abandoned it for this tomb. The various stages of decoration in the burial chamber give a fascinating glimpse into the process of tomb decoration.

From the entrance, a steep flight of steps and an equally steep passage lead to a well shaft decorated with superb figures of Horemheb before the gods. Notice Hathor’s blue-and-black striped wig and the lotus crown of the young god Nefertum, all executed against a grey-blue background. The six-pillared burial chamber, decorated with part of the Book of Gates, remains partially unfinished, showing how the decoration was applied by following a grid system in red ink over which the figures were drawn in black prior to their carving and painting. The pharaoh’s empty red-granite sarcophagus carved with protective figures of goddesses with outstretched wings remains in the tomb; his mummy is missing.

Tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35)Tomb

This 91m-long tomb was built for Amenhotep II (sometimes also called Amenophis II), who succeeded his father, the great king Tuthmosis III. Amenophis died around 1400 BC after a 26-year reign, long enough to excavate this large and complicated tomb with its six-pillared inner hall leading to the burial chamber. The pharaoh’s remains were found here along with many other royal mummies when the tomb was opened by French archaeologist Victor Loret in 1898.

One of the deepest structures in the valley, this tomb has more than 90 steps down to a modern gangway, built over a deep pit designed to protect the inner, lower chambers from both thieves (which it failed to do) and from flash floods.

Stars cover the entire ceiling in the huge burial chamber and the walls feature, as if on a giant painted scroll, text from the Book of Amduat. While most figures are of the same stick-like proportions as in the tomb of Tuthmosis III, this is the first royal tomb in the valley to present figures with more rounded proportions, as on the pillars in the burial chamber showing the pharaoh before Osiris, Hathor and Anubis. The burial chamber is also unique for its double level; the top level was filled with pillars, the bottom contained the sarcophagus.

Although thieves breached the tomb in antiquity, Amenhotep’s mummy was restored by the priests, put back in his sarcophagus with a garland of flowers around his neck, and buried in the two side rooms with 13 other royal mummies, including Tuthmosis IV (1400–1390 BC), Amenhotep III, Merenptah, Ramses IV, V and VI, and Seti II (1200–1194 BC), most of which are now at the Egyptian Museum.

Tomb of Tuthmosis III (KV 34)Tomb

Hidden in the hills between high limestone cliffs, and reached only via a steep staircase that crosses an even steeper ravine, this tomb demonstrates the lengths to which the ancient pharaohs went to thwart the cunning of the ancient thieves. Tuthmosis III (1479–1425 BC), an innovator in many fields, and whose military exploits and stature earned him the description ‘the Napoleon of ancient Egypt’, was one of the first to build his tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

It is a steep climb up and down, but secrecy was the pharaoh’s utmost concern: he chose the most inaccessible spot and designed his burial place with a series of passages at haphazard angles and fake doors to mislead or catch potential robbers. The shaft, now traversed by a narrow gangway, leads to an antechamber supported by two pillars, the walls of which are adorned with a list of more than 700 gods and demigods. As the earliest tomb in the valley to be painted, the walls appear to be simply giant versions of funerary papyri, with scenes populated by stick men. The burial chamber has curved walls and is oval in shape; it contains the pharaoh’s quartzite sarcophagus, which is carved in the shape of a cartouche.

Tomb of Siptah (KV 47)Tomb

Discovered in 1905, the tomb of Siptah (1194–1188 BC) was never completed, but the upper corridors are nonetheless covered in fine paintings. The tomb’s entrance is decorated with the sun disc, and figures of Maat, the goddess of truth, kneel on each side of the doorway. There are further scenes from the Book of Amduat, and figures of Anubis, after which the tomb remains undecorated.

Tomb of Tawosret/Sethnakht (KV 14)Tomb

Tawosret was the wife of Seti II and after his successor Siptah died, she took power herself (1188–1186 BC). Egyptologists think she began the tomb for herself and Seti II, but their burials were removed by her successor, the equally short-lived Sethnakht (1186–1184 BC), who added a second burial chamber for himself. The tomb has been open since antiquity and some decoration has deteriorated.

The change of ownership can be seen in the tomb’s decoration; the upper corridors show the queen, accompanied by her stepson Siptah, in the presence of the gods. Siptah’s cartouche was later replaced by Seti II’s. But in the lower corridors and burial chambers, images of Tawosret have been plastered over by images or cartouches of Sethnakht. The colour and state of the burial chambers remains good, with astronomical ceiling decorations and images of Tawosret and Sethnakht with the gods. The final scene from the Book of Caverns adorning Tawosret’s burial chamber is particularly impressive, showing the sun god as a ram-headed figure stretching out his wings to emerge from the darkness of the underworld.

Tomb of Seti II (KV 15)Tomb

Adjacent to the tomb of Tawosret/Sethnakht is a smaller tomb where it seems Sethnakht buried Seti II (1200–1194 BC) after turfing him out of KV 14. Open since ancient times, judging by the many examples of classical graffiti, the tomb’s entrance area has some finely carved relief scenes, although the rest was quickly finished off in paint alone. The walls have extracts from the Litany of Ra, the Book of Gates and the Book of Amduat.

One unusual feature of the decoration here can be found on the walls of the well room: images of the type of funerary objects used in pharaohs’ tombs, such as golden statuettes of the pharaoh within a shrine.

Tomb of Ramses I (KV 16)Tomb

Unfinished at the time of his death in 1294 BC after a two-year reign, Ramses I’s simple tomb has the shortest entrance corridor; it leads to a single, almost square, burial chamber, containing the pharaoh’s open pink-granite sarcophagus. Discovered and excavated (like many others) in 1817 by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni, the quartzite sarcophagus is in place and some of the wall paintings are still fresh.

Only the chamber is superbly decorated, very similar to Horemheb’s tomb (KV 57), with extracts from the Book of Gates, as well as scenes of the pharaoh in the presence of the gods, eg the pharaoh kneeling between the jackal-headed ‘Soul of Nekhen’ and the falcon-headed ‘Soul of Pe’, symbolising Upper and Lower Egypt.

![]() oTomb of Seti I (KV 17)Tomb

oTomb of Seti I (KV 17)Tomb

(MAP; Valley of the Kings; LE1000, plus Valley of the Kings ticket; ![]() h 6am-5pm)

h 6am-5pm)

One of the great achievements of Egyptian art, this cathedral-like tomb is the finest in the Valley of the Kings. Long closed to visitors, it is now reopened and if you can afford the ticket, it is money well spent. The 137m-long tomb was completely decorated and beautifully preserved when Giovanni Belzoni opened it in 1817, and although it has suffered since, it still offers an eye-popping experience – art from Seti’s reign is among the finest in Egypt.

Seti I, who succeeded Ramses I and was father of Ramses II, ruled some 70 years after the death of Tutankhamun. After the chaos of the Akhenaten years at Tell Al Amarna, Seti I’s reign was a golden age that saw a revival of Old Kingdom-style art, best seen at his temple in Abydos and here in his tomb. The tomb suffered after Belzoni made copies of the decoration by laying wet papers over the raised reliefs and lifting off some of the colour. Subsequent visitors did more damage, with Champollion, the man who deciphered hieroglyphs, even cutting out some of the wall decoration. The tomb was reopened in 2016 and its walls are filled with fabulous images from many ancient texts, including the Litany of Ra, Book of the Dead, Book of Gates, Book of the Heavenly Cow and many others. The sarcophagus, one of the finest carved in Egypt and taken by Belzoni, now sits in the Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, while two of its painted reliefs showing Seti with Hathor are now in the Louvre in Paris and Florence’s Archaeological Museum.

Tomb of Mentuherkhepeshef (KV 19)Tomb

The only tomb of a prince that you can visit in the Valley of the Kings (others are closed), this was decorated for Prince Rameses Mentuherkhepeshef (c 1000 BC), a son of Rameses IX. When Giovanni Belzoni discovered it in 1817, he found a number of later mummies buried here. Mentuherkhepeshef’s remains have not been found. There are good wall paintings, although they are now behind glass since a 1994 flood damaged the lower parts of the walls.

Mentuherkhepeshef’s name translates as ‘The Arm of Mentu is Strong’. The entrance corridor to his tomb is adorned with life-size reliefs of various gods, including Osiris, Ptah, Thoth and Khonsu, receiving offerings from the young prince, who is shown in all his finery, wearing exquisitely pleated fine linen robes and a blue-and-gold ‘sidelock of youth’ attached to his black wig – not to mention his gorgeous make-up (as worn by both men and women in ancient Egypt).

Tomb of Tuthmosis IV (KV 43)Tomb

The tomb of Tuthmosis IV (1400–1390 BC) is one of the largest and deepest tombs constructed during the 18th dynasty. It is also the first in which paint was applied over a yellow background, beginning a tradition that was continued in many tombs. It was discovered in 1903 by Howard Carter, 20 years earlier than the tomb of Tuthmosis IV’s great-grandson, Tutankhamun.

It is accessed by two long flights of steps leading down and around to the burial chamber where there’s an enormous sarcophagus covered in hieroglyphs. The walls of the well shaft and antechamber are decorated with painted scenes of Tuthmosis before the gods, and the figures of the goddess Hathor are particularly fetching in a range of beautiful dresses decorated with beaded designs.

On the left (south) wall of the antechamber there is a patch of ancient Egyptian graffiti dating back to 1315 BC. It was written by government official Maya and his assistant Djehutymose, and refers to their inspection and restoration of Tuthmosis IV’s burial on the orders of Horemheb, following the first wave of robbery in the eighth year of Horemheb’s reign, some 67 years after Tuthmosis IV died.

Tomb of AyTomb

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; adult/student LE40/20, plus Valley of the Kings ticket; ![]() h 6am-5pm)

h 6am-5pm)

Although only the burial chamber is decorated, this tomb, tucked away in the West Valley, is noted for its scenes of Ay hunting hippopotamus and fishing in the marshes (scenes usually found in the tombs of nobles not royalty), and for a wall featuring 12 baboons, representing the 12 hours of the night, after which the West Valley or Wadi Al Gurud (Valley of the Monkeys) is named.

Although he succeeded Tutankhamun, Ay’s brief reign from 1327 to 1323 BC tends to be associated with the earlier Amarna period and Akhenaten (some Egyptologists have suggested he could have been the father of Akhenaten’s wife Nefertiti). Ay abandoned a grandiose tomb in Amarna and took over another here in the West Valley. The valley played an important part in the Amarna story, as it was chosen as a new burial ground by Amenhotep III for his own enormous tomb (KV 22, part way up the valley), and his son and successor Akhenaten also began a tomb here, before he relocated the capital at Amarna, where he was eventually buried.

It seems Tutankhamun also planned to be buried in the West Valley, until his early death saw his successor Ay ‘switch’ tombs. Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb (KV 62) in the traditional section of the Valley of the Kings, while Ay himself took over the tomb Tutankhamun had begun at the head of the West Valley. The tomb is accessed by a dirt road that leads off from the car park at the Valley of the Kings and winds for almost 2km up a desolate valley past sheer rock cliffs. Recapturing the atmosphere (and silence) once found in the neighbouring Valley of the Kings makes it worth the visit.

AVENUE OF SPHINXES

A 3km-long alley of sphinxes connecting Luxor and Karnak is being excavated. Most of the buildings covering the sphinxes have been demolished, including some that were important to the development of 19th- and early-20th-century Luxor. The avenue will eventually be completely revealed, although it remains to be seen how many people will want to walk from Luxor to Karnak temples.

Valley of the Queens

At the southern end of the Theban hillside, the Valley of the Queens (Biban Al Harim; MAP GOOGLE MAP; adult/student LE80/40; ![]() h

6am-5pm) contains at least 75 tombs that belonged to queens of the 19th and 20th dynasties as well as to other members of the royal families, including princesses and the Ramesside princes. Four of the tombs are open for viewing. The most famous of these, the tomb of Nefertari, was only reopened to the public in late 2016. The other tombs are those of Titi, Khaemwaset and Amunherkhepshef.

h

6am-5pm) contains at least 75 tombs that belonged to queens of the 19th and 20th dynasties as well as to other members of the royal families, including princesses and the Ramesside princes. Four of the tombs are open for viewing. The most famous of these, the tomb of Nefertari, was only reopened to the public in late 2016. The other tombs are those of Titi, Khaemwaset and Amunherkhepshef.

An additional ticket is required for Tomb of Nefertari.

Tomb of NefertariTomb

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; LE1000, plus Valley of the Queens ticket; ![]() h 6am-5pm)

h 6am-5pm)

Nefertari’s tomb is hailed as one of the finest in the Theban necropolis – and all of Egypt for that matter. Nefertari was one of five wives of Ramses II, the New Kingdom pharaoh known for his colossal monuments, but the tomb he built for his favourite queen is a shrine to her beauty and, without doubt, an exquisite labour of love. Every centimetre of the walls in the tomb’s three chambers and connecting corridors is adorned with colourful scenes.

Nefertari, known as the ‘Most Beautiful of Them’, is depicted wearing a divinely transparent white gown and a golden headdress featuring two long feathers extending from the back of a vulture. The ceiling of the tomb is festooned with golden stars. In many places the queen is shown in the company of the gods and with associated text from the Book of the Dead.

Like most of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, this one had been plundered by the time it was discovered by archaeologists. Only a few fragments of the queen’s pink-granite sarcophagus remained, and of her mummified body, only traces of her knees were left.

A replica of the tomb is planned to be installed, alongside the replica of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, near Howard Carter’s house.

Tomb of AmunherkhepshefTomb

If you can’t afford entry to the Tomb of Nefertari, the valley’s showpiece is the tomb of Amunherkhepshef, with beautiful, well-preserved reliefs. Amunherkhepshef, a son of Ramses III, was in his teens when he died. On the walls of the tomb’s vestibule, Ramses holds his son’s hand to introduce him to the gods who will help him on his journey to the afterlife. Amunherkhepshef wears a kilt and sandals, with the sidelock of hair typical of young boys.

The mummified five-month-old foetus on display in the tomb is the subject of many an inventive story, among them the suggestion that the foetus was aborted by Amunherkhepshef’s mother when she heard of his death. It was actually found by Italian excavators in a valley to the south of the Valley of the Queens.

Tomb of KhaemwasetTomb

Like his neighbour Amunherkhepshef, Khaemwaset was a son of Ramses III who died young; there is little information about his age or cause of death. His tomb follows a linear plan and is decorated with well-preserved, brightly coloured scenes of Ramses introducing his son to the gods, and scenes from the Book of the Dead. The vestibule has an astronomical ceiling, showing Ramses III in full ceremonial dress; Khaemwaset wears a tunic, the sidelock of hair signifying his youth.

Tomb of TitiTomb

(MAP GOOGLE MAP; Valley of the Queens; adult/student LE50/25; ![]() h 6am-5pm)

h 6am-5pm)

The tomb of Queen Titi has a corridor leading to a square chapel, off which is the burial chamber and two smaller rooms. The paintings are faded, but you can still make out a winged Maat kneeling on the left-hand side of the corridor, and the queen before Thoth, Ptah and the four sons of Horus opposite. Inside the burial chamber are a series of animal guardians: a jackal and lion, two monkeys, and a monkey with a bow.

Egyptologists are not sure which Ramesside pharaoh Titi was married to; in her tomb she is referred to as the royal wife, royal mother and royal daughter. Some archaeologists believe she was the wife of Ramses III, and her tomb is in many ways similar to those of Khaemwaset and Amunherkhepshef, perhaps her sons.

MAKING MUMMIES

Although the practice of preserving dead bodies can be found in cultures across the world, the Egyptians were the ultimate practitioners of this highly complex procedure that they refined over a period of almost 4000 years. Their preservation of the dead can be traced back to the very earliest times, when bodies were simply buried in the desert away from the limited areas of cultivation. In direct contact with the sand that covered them, the hot, dry conditions allowed the body fluids to drain away while preserving the skin, hair and nails intact. Accidentally uncovering such bodies must have had a profound effect upon those who were able to recognise people who had died years earlier.

So began a long process of experimentation to preserve the bodies without burying them in the sand. It wasn’t until around 2600 BC that internal organs, which is where putrefaction actually begins, began to be removed. As the process became increasingly elaborate, all the organs were removed except the kidneys, which were hard to reach, and the heart. The latter, which was considered the source of intelligence rather than the brain, was left in place, often with a heart amulet inscribed with an invocation from the Book of the Dead. The brain was removed by inserting a metal probe up the nose and whisking to reduce the organ to a liquid that could be easily drained away. All the rest – lungs, liver, stomach, intestines – were removed through an opening cut in the left flank. Then the body and its separate organs were covered with piles of natron salt and left to dry out for 40 days, after which they were washed, purified and anointed with a range of oils, spices and resins. All were then wrapped in layers of linen, with the appropriate amulets set in place over the various parts of the body as priests recited the incantations needed to activate the protective functions of the amulets.

Deir Al Medina

Deir Al Medina (Monastery of the Town or Workmen’s Village; MAP GOOGLE MAP; adult/student LE80/40; ![]() h 6am-5pm) takes its name from a Ptolemaic temple, later converted to a Coptic monastery – the Monastery of the Town – but the real attraction here is the unique Workmen’s Village. Many of the skilled workers and artists who created tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens lived and were buried here. Archaeologists have uncovered more than 70 houses in this village and many tombs; the most beautiful of these are now open to the public.

h 6am-5pm) takes its name from a Ptolemaic temple, later converted to a Coptic monastery – the Monastery of the Town – but the real attraction here is the unique Workmen’s Village. Many of the skilled workers and artists who created tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens lived and were buried here. Archaeologists have uncovered more than 70 houses in this village and many tombs; the most beautiful of these are now open to the public.

About 1km off the road to the Valley of the Queens and up a short, steep paved road, the small Ptolemaic-era temple, measuring only 10m by 15m, was built between 221 and 116 BC. It was dedicated to Hathor, the goddess of pleasure and love, and to Maat, the goddess of truth and personification of cosmic order. In front of the temple are the remains of the workmens’ village, mostly low walls although there are also remains of ancient irrigation pipes. More impressive, however, are the nearby tombs of Sennedjem, Peshedu, Inherka and Ipuy. Originally these were all topped by small mud-brick pyramids, one of which has been rebuilt.

ATomb of Sennedjem

The tomb of Sennedjem is stunningly decorated and contains two small chambers with some exquisite paintings. Sennedjem was a 19th-dynasty artist who lived during the reigns of Seti I and Ramses II, and it seems he ensured his own tomb was as finely decorated as those of his masters. Images include Sennedjem farming with his wife, his mummification and a particularly beautiful image of Osiris with crook and flail.

ATomb of Inherka

Inherka was a 19th-dynasty servant who worked in the Place of Truth in the Valley of the Kings. His beautifully adorned one-room tomb has magnificent wall paintings, including a famous scene of a cat (representing the sun god Ra) killing a snake (representing the evil serpent Apophis) under a sacred tree, on the left wall. There are also beautiful domestic scenes of Inherka with his wife and children.

ATomb of Ipuy