CHAPTER 2

Early Studies

In this chapter we introduce the early studies of the greenhouse effect of the atmosphere and global climate change, conducted during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. We begin with the pioneering studies of Fourier, Tyndall, Arrhenius, and Hulbert.

The Heat-Trapping Envelope

The existence of the greenhouse effect of the atmosphere described in the preceding chapter was conjectured, perhaps for the first time, by the well-known mathematical physicist Jean-Baptiste Fourier. In essays published in 1824 and 1827 (Fourier, 1827; Pierrehumbert, 2004a, b), Fourier referred to an experiment conducted by Swiss scientist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. In this experiment, de Saussure lined a container with blackened cork and inserted into the cork several panes of transparent glass, separated by intervals of air. Midday sunlight could enter at the top of the container through the glass panes. The temperature became more elevated in the most interior compartment of this device. Fourier speculated that the atmosphere could form a stable barrier like the glass panes, trapping a substantial fraction of the upward flux of terrestrial radiation emitted by the Earth’s surface before it reached the top of the atmosphere, despite being almost transparent to incoming solar radiation as indicated in figure 1.6b. Although Fourier did not elaborate on the specific mechanism involved in the trapping described in chapter 1, it is quite remarkable that he correctly conjectured the existence of the greenhouse effect of the atmosphere based upon the simple experiments conducted by de Saussure. (For interesting commentaries on the papers by Fourier and de Saussure, see chapter 1 of The Warming Papers, edited by Archer and Pierrehumbert [2011].)

Fourier, however, did not identify the constituents of the atmosphere that allow it to act as a heat-trapping envelope. Irish physicist John Tyndall successfully identified these gases and evaluated the relative magnitudes of their contributions to the greenhouse effect of the atmosphere. His measuring device, which used thermopile technology, is an early landmark in the history of absorption spectroscopy of gases. Tyndall (1859, 1861) concluded that, although major constituents of the air such as nitrogen and oxygen are transparent to longwave radiation, minor constituents such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone absorb and emit longwave radiation (figure 1.6d), exerting the greenhouse effect. He found that, among these absorbing gases, water vapor is the strongest absorber in the atmosphere, followed by carbon dioxide. They are the principal gases controlling surface air temperature. The relative contributions of these gases to global warming have been the subject of quantitative evaluation by Wang et al. (1976) and Ramanathan et al. (1985).

The First Quantitative Estimate

In 1894, Svante Arrhenius of Sweden (figure 2.1) gave a very provocative lecture at a meeting of the Stockholm Physical Society, proposing that a change in the atmospheric CO2 concentration by two to three times may be enough to induce a change in climate comparable in magnitude to the glacial-interglacial difference in global mean surface temperature. In a paper published the following year, Arrhenius (1896) described in specific detail how he conducted his study, which turned out to be relevant not only to the large glacial-interglacial transition of climate (chapter 7), but also the global warming that is currently taking place. Here, we describe his truly pioneering study, which used a simple climate model to estimate the magnitude of the surface temperature change resulting from a change in atmospheric CO2 concentration.

FIGURE 2.1 Svante Arrhenius (1859–1927).

For this purpose, Arrhenius formulated two equations that represent the heat balance of the atmosphere and that of the Earth’s surface at each latitude and during each season of the year. In his formulation, the heat balance of the atmosphere is maintained among the following components:

• cooling and heating due to the emission and absorption of longwave radiation, respectively

• heating due to the absorption of solar radiation

• heating due to the net upward flux of heat from the Earth’s surface to the atmosphere

• heating or cooling due to meridional heat transport by large-scale circulation in the atmosphere

The heat balance of the Earth’s surface is maintained among the following components, implicitly assuming that the surface has no heat capacity and returns all of the radiative heat energy it receives in sensible and latent heat:

• cooling and heating due to the emission and absorption of longwave radiation, respectively

• heating due to the absorption of solar radiation

• cooling due to the net upward flux of heat from the Earth’s surface to the atmosphere

From the equation of the heat balance of the atmosphere and that of the Earth’s surface described above, Arrhenius obtained a formula that relates the temperature of the Earth’s surface to the atmospheric concentration of CO2. Using the formula thus obtained, he computed the change in surface temperature at various latitudes and during each season in response to a change in the CO2 concentration of the atmosphere. The positive feedback effect of water vapor described in chapter 1 was incorporated iteratively, keeping relative humidity unchanged in the atmosphere as temperature changed in each successive iteration. In addition to water vapor feedback, he incorporated the positive feedback effect of snow cover that retreats poleward as temperature increases, thereby enhancing the warming at the Earth’s surface. It is quite impressive that Arrhenius identified two of the most important positive feedback effects and incorporated them into his computation. It should be noted here, however, that Arrhenius assumed that the horizontal and vertical heat flux do not change despite the change in temperature at the Earth’s surface and in the atmosphere, greatly simplifying his computation. This assumption implies that the magnitude of the surface temperature change he obtained is controlled solely by radiative processes and does not depend on heat transport by the large-scale circulation and vertical convective heat transfer in the atmosphere.

Averaging globally and annually the surface temperature change thus obtained, Arrhenius found that the global mean surface temperature would increase by 5°C–6°C in response to a doubling of the atmospheric CO2 concentration. The magnitude of the global warming thus obtained is quite large and lies at the upper end of the sensitivity range of the current climate models (Flato et al., 2013). As discussed below, the large sensitivity of his model is attributable mainly to the unrealistically large absorptivity/emissivity of CO2 that Arrhenius used in his computation.

In order to estimate the absorption spectra of water vapor and CO2, Arrhenius used the record of radiation from the Moon obtained by astronomer and physicist Samuel Langley (1889). As pointed out in a detailed analysis by Ramanathan and Vogelmann (1997), the CO2 absorptivity Arrhenius used is too large by a factor of ~2.5. They suggested that this discrepancy is attributable mainly to the error involved in guessing the magnitude of the CO2 absorptivity from Langley’s observations over the spectral range, where the absorption bands of CO2 overlap with those of water vapor. When they repeated Arrhenius’s computation in the absence of albedo feedback using modern CO2 absorptivity data, they found that surface temperature increases by only ~2°C in response to the CO2 doubling. Although this is much smaller than the 5°C–6°C that Arrhenius obtained, it is similar to the sensitivity of one-dimensional models of the surface-atmosphere system that use modern CO2 absorptivity data.

As discussed already, the magnitude of the atmospheric greenhouse effect depends not only on the vertical distribution of greenhouse gases but also on the vertical temperature structure, which depends on both convective and radiative heat transfer. To obtain a reliable estimate of global warming, it is therefore desirable to use a multilayer radiative-convective model of the atmosphere rather than the one-layer model that Arrhenius used. The initial attempt to use such a model was made by E. O. Hulbert (1931). He developed a vertical-column model of the atmosphere, which consisted of the troposphere in radiative-convective equilibrium and the stratosphere in radiative equilibrium. He was very encouraged to find that his model simulated successfully the global mean temperature of the Earth’s surface. Using this model, Hulbert estimated the magnitude of surface temperature change that results from a given change in atmospheric CO2 concentration. He found that the temperature of the Earth’s surface increases by 4°C in response to a doubling of the atmospheric CO2 concentration in the absence of positive water vapor feedback. Realizing that the magnitude of the warming would have been even larger if this feedback had been taken into consideration, he concluded, in agreement with Arrhenius, that the CO2 theory of the ice ages was credible, despite various objections that had been raised against it.

The warming of 4°C (in response to CO2 doubling) obtained by Hulbert happens to be similar to the 3.8°C warming that Ramanathan and Vogelmann (1997) obtained, using a version of the Arrhenius’s model, in the absence of the water vapor and snow albedo feedbacks. Both of these values are about three times as large as the ~1.2°C that one gets from a radiative-convective model without these feedbacks, using modern CO2 absorptivity. It is therefore likely that Hulbert used CO2 absorptivity data that were too large by a factor of almost three, as Arrhenius did. Had Hulbert incorporated water vapor feedback into his computation, he would have found a surface temperature increase of as much as 6°C in response to a doubling of the atmospheric CO2 concentration.

Hulbert’s study is a natural extension of the study of Arrhenius. It uses for the first time a radiative-convective model of the atmosphere, which resolves the vertical temperature structure, to estimate the magnitude of global warming. Unfortunately, Hulbert’s study was overlooked or disregarded for a long time in favor of a very simple approach proposed by British engineer Guy Stewart Callendar, which we will discuss in the next section. Although Hulbert’s study has a serious flaw as discussed above, it is a truly groundbreaking contribution that predates by more than three decades the radiative-convective model study of Manabe and Wetherald (1967) that will be described in chapter 3.

A Simple Alternative

Several decades after the publication of Arrhenius’s study, Callendar made a renewed attempt to estimate the change of surface temperature that results from a change in atmospheric CO2 concentration. The main motive of his study, however, was different from that of Arrhenius’s. Arrhenius was mainly interested in exploring the role of greenhouse gases in producing the glacial-interglacial contrast in climate. But Callendar began his paper with the following assertion: “Few of those familiar with the natural heat exchanges of the atmosphere, which go into the making of our climate and weather, would be prepared to admit that the activities of man could have any influence upon phenomena of so vast a scale. In the following paper, I hope to show that such influence is not only possible but is occurring at the present time” (Callendar, 1938, 223).

Although Callendar was aware of Arrhenius’s study described above, he attempted to improve the estimate of the CO2-induced change in surface temperature using absorptivities of CO2 and water vapor that are more realistic than those used by Arrhenius. Callendar, however, employed a very simple method that is based solely upon the radiative heat balance of the Earth’s surface, which we describe in the remainder of this chapter.

As noted in chapter 1, a change in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration results in a change in the intensity of the downward flux of longwave radiation at the Earth’s surface. If the atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration increases, for example, the infrared opacity of air also increases, thereby enhancing the absorption of longwave radiation in the atmosphere. This implies that the absorption of the downward flux of longwave radiation from higher layers of the atmosphere increases more than that of the flux from lower layers. Thus, the effective height of the layer from which the downward flux originates decreases. Since temperature increases with decreasing height in the troposphere, where the downward flux of longwave radiation originates, this implies that the downward flux of longwave radiation increases at the Earth’s surface as the concentration of CO2 increases in the atmosphere. To maintain the heat balance of the Earth’s surface, it is therefore necessary that the increase in downward flux is compensated by an equal increase in the upward flux of longwave radiation, if other things remain unchanged. In his study, Callendar estimated the magnitude of the surface temperature change needed to keep the net upward flux of longwave radiation unchanged at the Earth’s surface despite an increase in downward flux due to the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration.

The net upward flux of longwave radiation (E) at the Earth’s surface is defined here as the difference between the upward flux (U) and downward flux (D) as expressed by:

where E is usually positive and is expected to increase with increasing surface temperature.

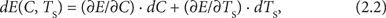

The perturbation equation of the net upward flux of longwave radiation at the Earth’s surface may be expressed by:

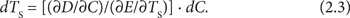

where C is the atmospheric CO2 concentration, and TS is the global mean temperature of the Earth’s surface. Assuming that the surface heat balance is maintained, dE(C, TS) = 0, which means that (∂E/∂C) = −(∂D/∂C). One can then derive the relationship between the changes in CO2 concentration and surface temperature, as expressed by:

Using equation (2.3) thus obtained, Callendar estimated the magnitude of surface temperature change that results from a given change in atmospheric CO2 concentration. He assumed that the vertical gradient of temperature is constant and does not depend upon surface temperature. This method led to the finding that surface temperature increases by about 2°C in response to the doubling of atmospheric CO2. Although it is less than half of the 5°C–6°C that Arrhenius obtained earlier, Callendar’s result appeared to be consistent with the observed increase of the global mean surface temperature over several decades in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

A few decades after the publication of Callendar’s study, several authors attempted to repeat the study, incorporating various factors that had been neglected by Callendar (Kaplan, 1960; Kondratiev and Niilisk, 1960; Möller, 1963; Plass, 1956). For example, Plass found that surface temperature increases by 3.6°C in response to a doubling of the CO2 concentration. Kaplan obtained ~1.5°C, taking into consideration the effect of clouds on the change in the downward flux of longwave radiation. Using the best CO2 absorptivity available at that time (e.g., Yamamoto and Sasamori, 1961), Möller (1963) obtained 1°C, which is about half as large as the 2°C originally obtained by Callendar. Realizing that the results presented above were obtained without accounting for water vapor feedback, Möller repeated the computation incorporating the feedback and obtained a quite surprising result.

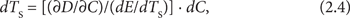

As explained in chapter 1, a warming of the Earth’s surface induced by an increase in greenhouse gases is accompanied by an increase in temperature throughout the troposphere and an increase in absolute humidity, keeping relative humidity essentially unchanged. The increase in absolute humidity leads to an additional increase in the infrared opacity of the troposphere, reducing further the average height of the layer from which the downward flux of longwave radiation originates. Because temperature increases with decreasing height in the troposphere as noted above, the downward flux of longwave radiation increases, thereby enhancing the warming at the Earth’s surface through the positive feedback effect of water vapor. To incorporate this effect, Möller modified equation (2.3), replacing ∂E/∂TS by dE/dTS, and obtained the following equation, which describes the relationship between dTS and dC in the presence of the water vapor feedback:

where dE/dTS depends not only on TS but also on W (i.e., the total moisture content of the atmosphere). Given that (∂E/∂W) = −(∂D/∂W), it may be expressed by:

Since the downward flux of longwave radiation increases with increasing W, which increases with increasing surface temperature as explained above, the second term, ∂D/∂W · (dW/dTS), on the right side of equation (2.5) is positive and compensates for the first term, which is positive as noted already, thereby reducing the strength of the radiative feedback (i.e., dE/dTS) that operates on the perturbation of the global mean surface temperature. Assuming that surface temperature is 15°C and relative humidity of air is fixed at 77%, for example, the two terms on the right side of equation (2.5) compensate for each other almost completely, yielding a very small negative value of dE/dTS. In other words, the net upward flux of longwave radiation decreases slightly with increasing surface temperature. This implies that, in the presence of water vapor feedback, the net upward flux of longwave radiation cannot compensate for the increase in the downward flux due to the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Inserting the value of dE/dTS thus obtained into equation (2.4), one gets a large cooling of as much as 6°C in response to a doubling of atmospheric CO2. This irrational result is obtained because longwave feedback is positive and equation (2.4) is no longer valid.

One of the important components of heat balance at the Earth’s surface is the upward flux of sensible heat and latent heat of evaporation to the atmosphere. When the downward flux of longwave radiation increases at the Earth’s surface owing to an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration, the temperature increases at the Earth’s surface, thereby increasing the upward sensible and latent heat flux to the atmosphere. To estimate the magnitude of temperature change at the Earth’s surface, Callendar assumed, however, that the upward flux of sensible and latent heat does not change, despite the change in surface temperature. Thus, he neglected one of the important processes that contribute to the heat balance of the Earth’s surface. This is the main reason why Möller, who used a surface heat balance approach similar to Callendar’s, encountered the difficulty described above. Although Arrhenius also assumed incorrectly that the upward sensible and latent heat flux does not change, he did not experience a similar difficulty because the vertical temperature gradient in the atmosphere is permitted to increase in his model. The strengthened vertical gradient results in an increase in the net upward flux of longwave radiation at the Earth’s surface, which helps to compensate for the increase in the downward flux that results from the increase in CO2 and water vapor. On the other hand, the vertical temperature gradient is held fixed in Callendar’s model, making it impossible for the net upward flux of longwave radiation to increase enough to compensate for the increase in downward flux that results from the increase in both of these gases in the atmosphere.

We note here that Newell and Dopplick (1979) made a renewed attempt to estimate the change in surface temperature in response to a doubling of atmospheric CO2 concentration, using a heat balance model of the Earth’s surface that incorporates the effect of heat exchange between the surface and the atmosphere. They found that the magnitude of the increase in surface temperature is less than 0.25°C. As discussed by Watts (1981), for example, the small response of their model is attributable in no small part to the unrealistic assumption that the temperature and absolute humidity of air in the near surface layer of the atmosphere do not change in response to the increase in CO2 concentration, thereby severely constraining the magnitude of temperature change at the Earth’s surface.

To obtain a reliable estimate of global warming, it is desirable to construct a model in which the heat exchange between the Earth’s surface and the atmosphere is computed without making an artificial assumption as Callendar did. An approach that did not require this assumption involved the adaptation of a radiative-convective model (such as that developed by Hulbert) for use in the study of global warming. In chapter 3 we shall present such a study conducted in the early 1960s, when accurate measurements of the absorptivity of greenhouse gases became available and simple schemes for reliably estimating radiative heat transfer (e.g., Goody, 1964; Yamamoto, 1952) had been developed.