Late in the nineteenth century and early in the twentieth there was a marked influence of Irishmen and their descendants on the Victoria Police Force. The police were very often Irish, and so were those opposed to the police, including Ned Kelly and John Wren, whose illegal activities resulted in royal commissions that exposed the force and its operations to searching public scrutiny, and ultimately produced important changes in police procedures, personnel and conditions of service.

One milestone passed in this era was the appointment of serving members to the top police post, and the image of the force was also enhanced by an unusual public interest in the activities of police personalities, such as David O’Donnell, John Christie and Thomas Waldron, who became household names. However, the police were at times subjected to searing criticism and were troubled by internal industrial disputes and confrontations between policemen, trade unionists and unemployed people. Under Chomley and O’Callaghan, police administration was generally conservative—often reactionary—and the force failed to keep pace with Victorians’ changing values, attitudes, expectations and technology.

Ned Kelly had an emotional but uncompromising view of those who hunted him. The police were:

a parcel of big ugly fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splay-footed sons of Irish Bailiffs or English landlords which is better known as officers of Justice or Victorian Police …1

Kelly was born in Australia and never set foot in Ireland but his ancestry produced in him a sense of Irish heritage and prompted his vilification of Irish police in Australia as men who betrayed their ancestors and religion. Kelly criticised the police often and contrasted ‘cowardly’ Irishmen, who became police, with the ‘bold and blooming’ Irishmen who died bravely in chains. Although Kelly was one of the few people to acknowledge publicly the role of Irish police in Victoria, his general view of the Irish was romanticised and biased. Even he probably underestimated the extent to which Irishmen dominated the police force, and certainly he overstated the degree to which the Irish were heroic rebels fighting for social justice.

Long after Kelly, writers have persisted with the romanticised depiction of Irishmen in Australia as underdogs championing the cause of the underdog. Works such as The Irish in Australia, Australia’s Debt to Irish Nation-Builders and The Irish at Eureka revere Irish-Australians and perpetuate the image of them as poor, honest and brave men, moved to action by a sense of justice and social inequality. References to Irish police are few, and are often anecdotes about the likes of the genial Sergeant Dalton, ‘a kindly, good natured giant’ from Kilkenny, whom some credit with coining the word ‘larrikin’. The importance of Irish police throughout the nineteenth century sits poorly with any narrow view of the Irish as natural rebels, yet it has not found much place in Irish-Australian literature or mythology.2 That pro-Irish publications and the writings of Ned Kelly have taken this course is understandable, if inaccurate. However, at least one contemporary researcher with pretensions to greater accuracy promotes this Irish-Australian mythology. Neil Coughlan claims that the ‘generally high crime rate’ of the Irish-born in Victoria

bespoke a group alienated from the colony’s social structure (by lower income, education and social standing, if nothing else) and perhaps from its British system of law, and concepts of rights and property … young, unsettled, poorly educated and employed, and in general, comparatively untouched by any prevailing ethic of social responsibility and propriety.

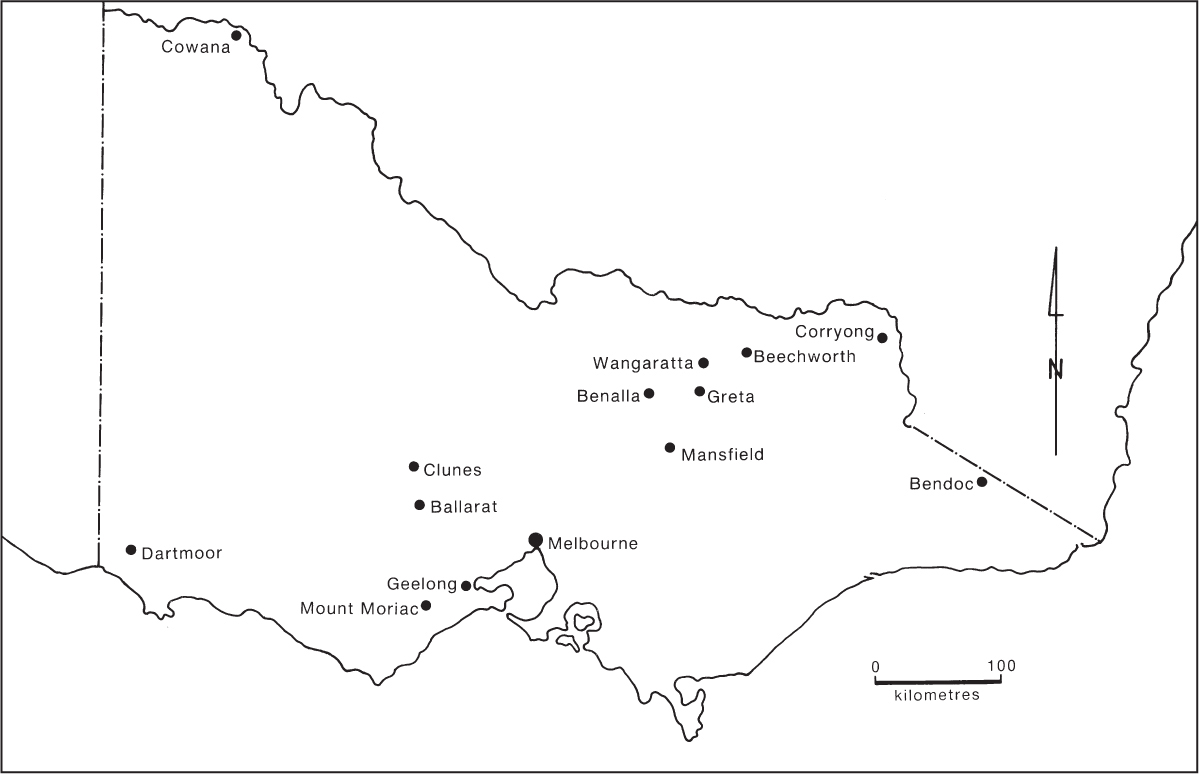

Places mentioned in Chapter 3

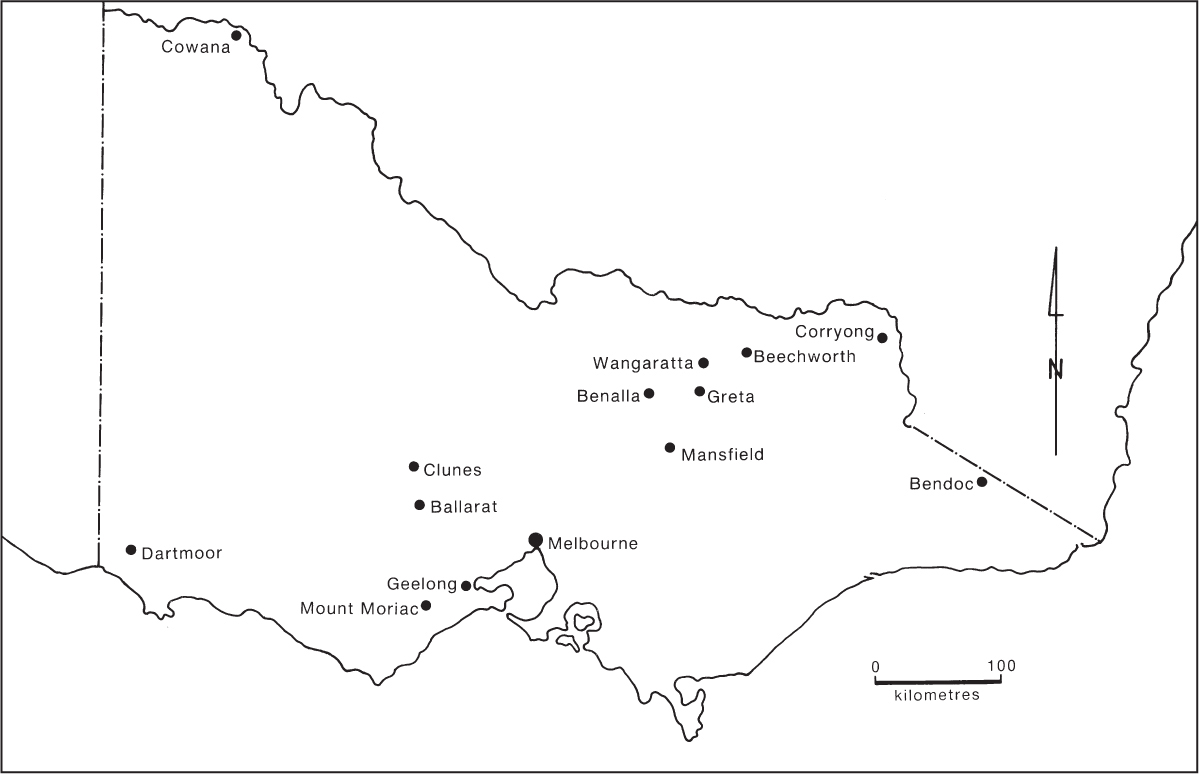

Senior Constable Michael Kennedy’s oath sheet

While this view undoubtedly contains elements of truth, it panders to the myth-makers and ignores the facts that, during the period studied, a former chief commissioner of police, Charles MacMahon, was Irish, as were the vast majority of officers and sub-officers in the police force, and three out of every four Victorian attorneys-general and solicitors-general were Irish-born. Recent literature perpetuates one-sided views such as Coughlan’s, without qualification and balance. Niall Brennan is one who propounds the Coughlan hypothesis of Irish-Australian outlawry and cites as ‘evidence’ the fact that a disproportionate number of Irish-born were gaoled in Victoria in 1870. In fact, the proportion of Irishmen taken into custody during 1870 was much less than their proportion of the police force. Irish males taken into custody numbered 6352 (33 per cent) of a total 19 525 males. Irish police numbered 867 (82 per cent) of a total police force of 1060.3

Few—if any—authors, whether writing of the Irish-Australian tradition, bushranging or the police, seem to have been aware of the pervasive influence of Irishmen in the Victoria Police Force. It is misleading to go only as far as Garry Disher, who wrote that ‘The police were a mixture of native-born and immigrant men, many of them Irish’. The police were overwhelmingly Irish, although even accomplished historians like John McQuilton seem not to have realised the full extent of the Irish domination. He wrote: ‘The officers had been drawn from outside the colony, some having served with the notorious Irish Constabulary. None were native-born. But the rank and file did include the native-born and hostility developed between the native and the immigrant’. Certainly, much of this inaccuracy is due to the fact that precise figures have not previously been collated. However, the public statements of senior police and John Woods, MLA, early in the 1860s, that the force was being over-run with Irishmen, might have alerted people to the fact that the Irish police presence was more than fairly common. The real situation was closer to being an Irish invasion.

Nor was Victoria unique. The prominence of Irish policemen in Western Australia prompted the T’othersider to offer this definition: ‘A Policeman: A man with a uniform, a brogue and a big free thirst’. Statistically, the thirst is unproven, but there are figures to demonstrate how commonly a police uniform and a brogue were combined. In December 1873 a new Police Regulation Act became law in Victoria, necessitating the re-swearing of all the police. The ceremonies were held during January 1874 and all 1060 police were required to state their place of birth (as well as previous occupation, and religion, and to declare membership of any secret society).4

Table 2 shows clearly that the force was not a representative mixture of Australians and immigrants, but was overwhelmingly dominated by Irishmen, whose numbers in the police were at a level significantly—and quite astonishingly—disproportionate to their percentage of the Victorian population. Of all male ethnic groups, Irishmen formed the only group statistically over-represented in the police. By contrast, Australian-born males in the colony numbered more than 170 000—or almost half of all the males—and yet only thirty of them were in the police force. Although a high percentage of Irishmen has been found in other police forces, none has approximated the level of Irish domination evident in Victoria in the 1870s. Researchers looking at the New South Wales and Western Australian police have discovered significantly high levels of Irish membership, but the respective percentages of approximately 60 and 30 per cent are well short of the Victorian figure of 82 per cent.5

TABLE 2

Ethnic composition of the Victoria Police Force in January 1874, compared with estimated percentage of male ethnic groups in total Victoria population

* The percentage of males in the population is an estimation based upon figures published in the 1871 Census of Victoria.

† Other includes ‘At Sea’, Canada, Cape of Good Hope, China, East and West Indies, France, Guernsey, Holstein and Mauritius.

Irish police also figured in a large number of overseas forces in Canada, England, Scotland and the United States, and enlisted in the British colonial police forces in Africa, Asia, Palestine and the Caribbean. In most of these forces the Irish presence was representative rather than dominant. Although it was sometimes the latter, rarely was the enlistment rate anything like 82 per cent. The proportion of Irishmen in the Victoria Police Force put it into a class with police forces in New York City and New England, where their domination by Irishmen is legendary.

Irish police historian Seamus Breathnach has considered the role of Irishmen in foreign police forces (not including Australia) and suggests that the Irish have had a particular interest in ‘policemanship’ and that, like Irish militarists, émigré Irish police extend over time and territory from eighteenth-century France to twentieth-century America. Although the work of Breathnach and others shows that Irish domination of a police force was not unique to Victoria, no study so far has successfully explained what attracted Irishmen to police work, or shown what influence they had upon the forces they joined.6

In the case of Victoria a partial explanation is found in an analysis of the occupational backgrounds of the Irishmen who joined the force. Table 3 shows that more than half of the Irish members of the Victoria Police in 1874 had previously worked in other police forces, and that 46 per cent of all Irishmen in the force were former members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). By any standards, these figures are significant, although it still remains difficult to say precisely what attracted such large numbers to Victoria. Although Irish-born men were prominent in Victorian politics, Chief Commissioner Standish was a leading member of the Freemasons and an Englishman. In the 1850s efforts were made by a committee of colonists from Victoria to recruit police from Ireland, but the attempt failed, and although O’Shanassy later displayed favouritism in recruiting Irish Catholics, that was stopped in 1863 after a select committee criticised the practice. Apart from these incidents there is no evidence of a deliberate campaign to recruit Irishmen, whether policemen or not, into the force. Indeed, the reverse applied, and MacMahon at times favoured Scotsmen and Englishmen. The explanation for the heavy presence in Victoria of former members of the RIC seems to rest with events in Ireland.

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century the RIC was a large force, usually over ten thousand men, but subject to substantial fluctuations in manpower levels according to the rise and fall of political unrest. During the later 1850s and early 1860s more than six thousand men resigned from the Irish Constabulary, and by the mid-1860s resignations outpaced recruiting. Apart from retrenchments whenever the country went quiet, RIC numbers were reduced by a high resignation rate due to low wages and poor working conditions. During those lean years a large number of young policemen resigned with the express intention of emigrating to Australia or America, where policemen ‘were earning heaps of money’.7 There is obviously some correlation between mass resignations of police in Ireland and their recruitment in Victoria. The ‘heaps of money’ might also account for many of the Irishmen who were not former members of the RIC but joined the force in Victoria. One student of Irish police history has suggested that an important factor attracting Irishmen to places like Victoria was the opportunity of marriage. Irish police regulations forbade policemen to marry unless they had served for at least seven years and could produce ‘evidence of solvency considered appropriate to a married state’. In addition, only one-quarter of the men in the force were allowed to be married and there was a long list of bachelors waiting their turn. Strict moral standards were enforced and there was a disciplinary offence of ‘criminal intercourse’: extramarital sexual relations and marriage without permission were punishable by dismissal from the force. Although policemen in Victoria needed permission to marry, it was almost always given and none of the other Irish Constabulary restrictions applied. Irishmen, and others, in the Victoria Police Force were free to get married, raise children, and live away from police barracks. This prospect, when combined with the attraction of generally better work conditions and higher wages, was perhaps a lure to Irishmen who wanted to be policemen but also wanted a wife and children. Such a theory is speculative, but given the importance of marriage and children to Irish life it is one of the better explanations of what attracted hundreds of Irishmen to the Victoria Police.8

Source: Victoria Police Archives. Oath Sheets: 1874 Re-Sworn Series

Other theories merit investigation. Apart from Breathnach’s theory of ‘Irish policemanship’—the idea that Irishmen are natural policemen—there is also Hobsbawm’s theory that policemen are often recruited from the same material as social bandits. He claims that: ‘The tough man, who is unwilling to bear the traditional burdens of the common man in a class society, poverty and meekness, may escape from them by joining or serving the oppressors as well as by revolting against them’. Almost a century before Hobsbawm developed this theory of peasant bandits and state bandits, Ned Kelly suggested a similar idea in his letter from Jerilderie. Kelly argued that the Irish police were rogues at heart who were ‘too cowardly to follow it up without having the force to disguise it’. Hobsbawm and Kelly were both suggesting that the oppressors and those who opposed them were often drawn from the same basic stock. It is a notion given some weight by figures showing that Irish-born males in Victoria dominated both the prison population and the police force—yet such a theory needs more investigation and testing.9

An equally likely explanation for the dominant role of Irish police in Victoria is to be found in the work of MacDonagh, Coughlan and Fitzpatrick on Irish emigration to Victoria. Although the specific question of Irish police was not raised by them, their work does suggest some answers: Irish emigration to Victoria was largely state-aided, Irish immigrants filled the lowest places on the Victorian social ladder, the majority of Irishmen were fit only for unskilled manual work, and many of them exhibited a craving for security. Fitzpatrick found that Irishmen were:

unusually adept at securing the best of the worst jobs displaying ubiquity as dogsbodies to the rich and as ruthless rivals of the ‘established’ poor … any employment, however degrading or ill-paid, marked an improvement on home opportunities.

Although this poverty-stricken aspect can be pushed much too far, it remains at least part of the picture.10

Given all these factors, police work might have been attractive to Irishmen arriving on Victorian shores. It was unskilled manual work requiring no special training, just a sound body and minimum literacy levels. Police work paid moderately well and carried with it the promise of long-term job security and improving social status. It also offered fringe benefits in the form of a uniform, housing, a reward system and a police hospital. From the early 1850s onwards, the number of Irish-born men in the force increased steadily, giving it that strong Irish identity that undoubtedly attracted even more arrivals from Ireland. Whereas Australian-born men shunned police work, and English and Scotsmen often had the skills, resources or status to avoid it, it was open and acceptable to many Irishmen who arrived as poor state-aided migrants and who belonged to a race that displayed a world-wide interest in ‘policemanship’.

Royal Irish Constabulary, 1876

It is quite obscure why Australian men shunned police service, but—with only thirty native-born constables in a force of 1060—they obviously did so. Two historians have raised the general subject of Australian antipathy towards the police, and have concluded that native-born men did not join the forces because of the ‘Currency ethos’ and ‘the ill-repute of the force among colonials’. These theories are not supported by sufficient evidence and, until some comprehensive research into this subject is done, they are destined to remain unproven. One sidelight on this whole question is that police recruitment in the late 1880s showed a marked downturn in applications from Irishmen and a corresponding increase in applications from Australian-born men. In the absence of complete records it is very hard to know if the native-born applicants were the sons of Irishmen, but by the early 1920s the Irish-born element was fast disappearing and the force was dominated by men born in Australia. Using the 636 police strikers as a sample, 93 per cent of them were native-born.11

An important question prompted by Irish domination of the force in the 1870s is the extent to which their presence influenced the development and public image of the police. The Irishmen came from a country where the police system was political, repressive and unpopular. Members of the RIC were drilled and equipped as infantrymen and had all the attributes of a standing army. During the 1850s and 1860s the Irish Constabulary came under severe criticism from both the public and the magistrates. It was thought by some that the constabulary was too centralised, militarist and inefficient in the prevention and detection of crime. One observer of the Irish Constabulary wrote that it was ‘an Imperial political force, having none of the qualities of a police body … its extra-political duty and raison d’être is to form a bodyguard for the system of Irish landlordism’. The force was generally regarded as efficient in the suppression of civil disorder, and the tactics it used in dealing with secret societies and agrarian outrages made the Irish style of policing a popular choice with the ruling classes in other Commonwealth countries. Sir Charles Jeffries, author and deputy under-secretary of state for the colonies, was an advocate of the ‘paramilitary’ Irish Constabulary because men from it and forces modelled on it worked well as agents of central governments, in countries ‘where the population was predominantly rural, communications were poor, social conditions were largely primitive, and the recourse to violence by members of the public who were “agin the government” was not infrequent’. The Irish policing style was one that also utilised the gathering of political intelligence data, secret surveillance and the extensive use of informers. The activities of the Irish Tenant League, agricultural crop returns, and the 1850s elections were but three areas where the Irish police monitored public activity.12

Although the political climate of Ireland was different from that of Victoria, it is reasonable to expect that many of the Irish police in Victoria were inured to the ways of the RIC, accepting such duties and methods as normal. Indeed, given that no police training was conducted in Victoria, it is fair to expect that the ethics and skills of many Irish police in Victoria were unaltered from those taught in Ireland. Apart from the incidental participatory influence of former Irish police in Victoria, the force was largely modelled on the Irish Constabulary in its operational aspects, although the authorities chose to use the London model for administrative and discipline procedures. Thus the public face of the Victoria Police was Irish in appearance and design. It was a centrally controlled force of armed police, mounted and foot, not representative of the community it served, and reviled in some parts of the colony no less than were the police in Ireland.13

Some evidence of the result of Irish policing in Victoria was displayed in rural areas during the 1860s and 1870s. With the passing of the Land Acts, police were empowered to report on selections and could recommend the abolition of licences and leases. They were also used to remove selectors’ fences interfering with squatters’ runs, pursue alleged selector-duffers on behalf of the squatters’ Stock Protection Association, and deal with shearers engaged by squatters under the Masters and Servants Act. One officer described the presence of his men in parts of north-eastern Victoria as ‘an army of occupation’. Although the performance of such duties was not of itself ‘Irish’, the work was analogous to that performed by the RIC on behalf of landlords in Ireland. Victorian police were known to resort to perjury, brutality and the use of extensive ‘spy’ networks in order to control the selectors, to whom the police were synonymous with authority and the squatters. In Victoria the squatters had much for which to thank the Irish landlords’ policing precedent.14

Did the actions of the police result from the ethnic composition of the force, or from the deliberate policy of the government to use the Irish policing model? More than likely the police behaviour resulted from a compatible combination of men and policies. It is evident that trained Irish police using Irish police methods predominated in Victoria before the Kelly outbreak and rode roughshod over many small selectors. Their pursuit of the Kelly Gang thrust the shortcomings of the police and their methods into the limelight. Two decades before the Kelly outbreak Superintendent Power Le Poer Bookey described former members of the Irish Constabulary as ‘not nearly so sharp as they ought to be’, and the same sentiments echoed through the Warby Range when many of these men pursued Ned Kelly, a police killer and bushranger sometimes thought of as ‘an extraordinary man … superhuman … invulnerable, you can do nothing with him’. At least he was one sharp Irishman against others not so sharp, and he had the added advantage of not being a squatters’ man.15

Mounted police in 1875

Never in the history of the force has a clash between police and criminals had such public and dramatic consequences as did the Kelly hunt. Lives were lost, careers ruined and the innermost workings of the force made the subject of public scrutiny, debate and ridicule. In the final analysis it was found that many of the police—Irishmen and others—were not as efficient as they ought to have been and that Kelly, although not invulnerable, was certainly extraordinary.

Before 1878 Ned Kelly was known to few people outside north-eastern Victoria. The native-born son of an Irish Catholic ex-convict, he was a self-confessed horse thief with a criminal history that was not uncommon for one of the larrikin class: horse stealing, assault, assaulting police, drunk and disorderly, and sending an indecent letter. Although his brushes with the law spanned a decade, his criminal background was hardly noteworthy and its adolescent character is typified by his conviction for having a pair of calf’s testicles delivered to a childless married woman, with a note suggesting that they might be of some use to her. Contrary to popular mythology Ned Kelly and his family were not typical selectors and Ned was not a true representative of the selector class, championing their cause against the squatters. His family were indifferent farmers, and his mother’s small selection of 88 acres at Lurg was cultivated only twice. Ned did not take up his own selection when he had the opportunity, nor did any of the money that he boasted he made from horse stealing appear to find its way back into the family farm. Whereas other selectors and their sons were known to go shearing in New South Wales, using their earnings to improve their selections, Ned and his close associates did not. A recent study by Doug Morrissey has shown that the majority of selectors in north-eastern Victoria were honest and hard-working farmers who kept up the payments on their selections. A royal commission described Ned as one who ‘led a wild and reckless life, and was always associated with the dangerous characters’. He was a bush larrikin whose real friends were drawn from an extensive network of families tied to one another by blood, marriage and criminal activity. Members of this network, including Ned and his immediate relatives, often came under police notice—sometimes unfairly and roughly—but there is little evidence that this police activity amounted to victimisation, or that it justified the acts of killing and robbery that later made the Kelly Gang infamous. A royal commission found no evidence that Ned Kelly or his friends ‘were subjected to persecution or unnecessary annoyance at the hands of the police’.

The Kelly saga began in earnest on 15 April 1878 when Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick, of Benalla, visited the Kelly home at Eleven Mile Creek. Fitzpatrick, later described by Acting Chief Commissioner Chomley as ‘a liar and a larrikin’ and by himself ‘as not fit to be in the police force’, was not typical of the policemen of that region and had more in common with the likes of Ned Kelly than his police colleagues. Fitzpatrick claimed that he visited the home with the idea of arresting Ned’s brother Dan, who was wanted on warrant for horse stealing. He made no arrest, but he precipitated what is generally known as the Fitzpatrick Incident. The constable disobeyed instructions in imprudently going to the Kelly selection alone and without the warrant. Accounts of what then happened differ greatly, but two basic versions emerged. Fitzpatrick claimed that while trying to arrest Dan he was confronted and assaulted by a number of the Kelly clan, then shot in the wrist by Ned. The Kelly version is that Ned was not present at the time of Fitzpatrick’s visit and that Fitzpatrick was ushered from the premises without the use of arms. Whatever the true facts—and Fitzpatrick is even harder to believe than the Kellys—the incident became a turning point. Fitzpatrick’s allegation that Ned Kelly tried to murder him was used to issue arrest warrants against Ned, Dan and Ellen Kelly, Bill Skillion and Brickey Williamson. The latter three were quickly arrested, but Ned and Dan evaded capture.

The Kelly brothers, joined by two friends, remained at large for some months and, in October 1878, the police decided to mount a pincer movement, police parties of four men from Mansfield and five men from Greta to hunt the gang. Disguised as diggers, they were armed with revolvers, a Spencer rifle and a borrowed double-barrelled shotgun. The Mansfield party was led by Sergeant Michael Kennedy, an Irish Catholic, married with children. After fourteen years’ service, he was selected for the Kelly pursuit because he knew the country well. With him were constables Thomas Lonigan of Violet Town, Michael Scanlan of Mooroopna and Thomas McIntyre. These three were hand-picked for the patrol, Lonigan because he knew the Kellys, Scanlan because of his local knowledge, and McIntyre because he was a good camp cook. Only the cook returned alive.

On 25 October 1878 the Mansfield patrol camped overnight in a remote bush clearing on Stringybark Creek. The following day Kennedy and Scanlan went in search of the Kellys, leaving the other two at the camp. McIntyre, like many policemen at that time, was not a good bushman and in the absence of the patrol leader he shot at some parrots and lit a large fire. Unbeknown to any of the Kennedy party, they were based only a mile from the Kelly camp and the actions of McIntyre were a beacon to Ned and his companions, who knew the bush well. Later that day the outlaws raided the police camp, killing Lonigan and detaining McIntyre at gunpoint. Having gained initial ascendancy over their would-be captors, Kelly and company then lay in wait for the return of Kennedy and Scanlan. Less than an hour later the unsuspecting pair returned and were greeted by McIntyre who called on them to surrender. At first Kennedy thought it was a joke, but he was quickly put right and he and Scanlan engaged the outlaws in gunfire. McIntyre, survival uppermost in his mind, fled on foot and hid in a wombat hole. The Kelly Gang was superior in number and had the added advantage of surprise. Scanlan was shot down. Kennedy dismounted and fired at the Kellys and he was the only policeman to fire a weapon. Being outnumbered he tried to escape but he was pursued and shot in the chest and armpit. As Kennedy lay dying, Ned Kelly—in an act later described by a royal commission as ‘cruel, wanton and inhuman’—placed a gun against his chest and shot him dead. Then the bodies of the three fallen policemen were robbed.

In the clearing at Stringybark Creek the Kelly Gang passed the point of no return. For a few brief hours they had reversed the roles of hunter and hunted, but the violence that marked the end of the Kennedy patrol was the beginning of the gang as outlaws. Ned Kelly, Steve Hart, Dan Kelly and Joe Byrne embarked together on the path to infamy, for most of their remaining short lives leading the police a humiliating dance. During a period of twenty months they were pursued through a labyrinth of rural sympathisers in a saga that included spectacular bank robberies at Euroa and Jerilderie and reached its climax in the siege at Jones’s Hotel, Glenrowan, on 28 June 1880. Hart, Byrne and Dan Kelly died there, but Ned was spared for one last performance and on 28 October stood trial for the murder of Lonigan. Found guilty, Kelly was hanged at the Melbourne Gaol on 11 November 1880.16

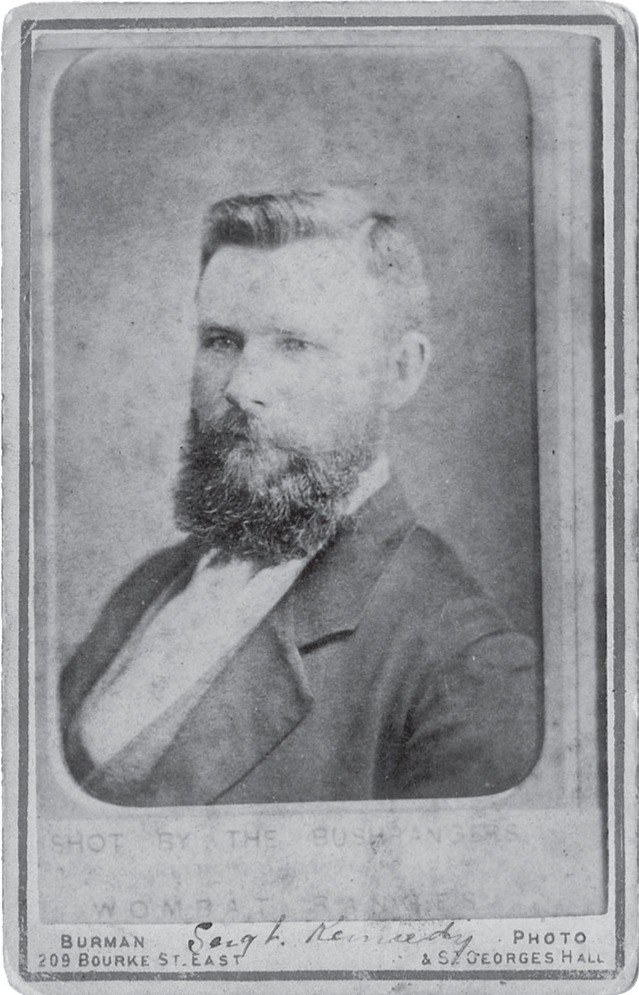

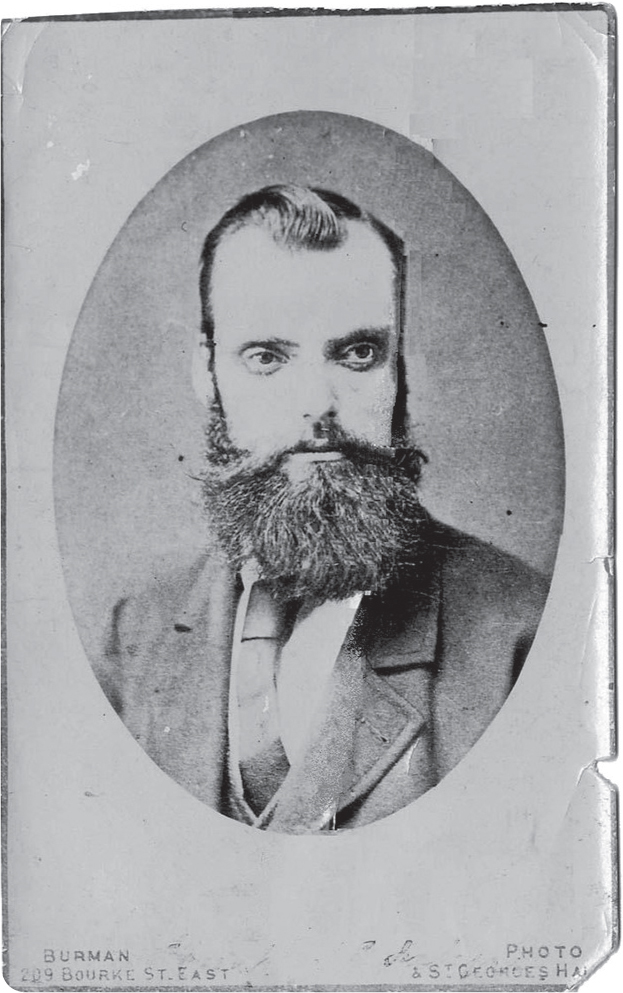

Constable Michael Scanlan.

Constable Thomas McIntyre.

Constable Thomas Lonigan.

Sergeant Michael Kennedy.

The Kelly outbreak lasted almost two years and in the end Ned Kelly met a violent and controversial death. During his time as an outlaw he and his companions tested the capabilities of the police to the limit—and beyond. It was both a tragic and humiliating time for the police; they were pilloried in the newspapers, criticised in parliament and made antagonistic to each other in the field. The destruction of the gang did not, however, bring respite for the beleaguered force, for the spectre of Kelly caused them as much anguish in death as he did in life. When sentenced by Redmond Barry, Kelly warned the judge, ‘I will see you there where I go’. It proved an apt epitaph for Barry, who died twelve days after Kelly’s execution. It also served as an appropriate parting curse for the police force as Kelly knew it.17

Only weeks after the Glenrowan siege Chief Commissioner Standish was forced to retire by the newly elected liberal government of Graham Berry. After twenty-two years as the colony’s leading policeman, Standish was dumped unceremoniously and replaced by Charles Nicolson, who was temporarily promoted from assistant commissioner to acting chief commissioner. Berry and his liberal colleagues, both in government and in opposition, had long been critical of the police and Standish, even though he had so astutely survived Berry’s Black Wednesday in 1878. Standish’s personal failings during his last years in office had, however, contributed substantially to the farcical hunt for the Kellys and destined him to relative obscurity. He accepted his sacking unquestioningly, but his last official despatch, pathetic and lonely, was to Berry, asking for permission to retain his official despatch box ‘in remembrance of my 22 years connection with the Police Department’. For the fallen chief there were no testimonials or accolades. With his despatch box and a pension, Standish retired on 30 September 1880. He died in Melbourne before the Longmore royal commission, inquiring into ‘his’ force, had produced its final report.18

Standish’s sacking and the execution of Kelly were followed by a public inquiry that lasted another two years. Almost as if it were the reincarnation of Ned, the inquiry brought alive the Kelly years. The sympathisers and the newspapers had a field day as the police force was again lambasted and lampooned. Ironically, some of the police had themselves requested an inquiry, but they had obviously not counted on its vituperative and searching nature. Instead of the anticipated exoneration and acclaim, several of them received rebuke, embarrassment and retirement.

The royal commission was appointed to inquire into the force on 7 March 1881 and, with Francis Longmore, MLA, as chairman, its terms of reference were to inquire into:

1. the circumstances preceding and attending the Kelly outbreak;

2. the efficiency of the Police to deal with such possible occurrences;

3. the action of the Police authorities during the period the Kelly Gang were at large;

4. the efficiency of the means employed for their capture; and

5. generally to report upon the present state and organization of the Police Force.19

The commission was faced with difficulties from the outset. A number of prominent men, including Alfred Deakin, were asked to sit on the inquiry but for undisclosed reasons they declined to do so. Others accepted the role initially but resigned either just before the inquiry sat or while it was in progress. Eventually eight commissioners, including Longmore, began hearing evidence on 23 March 1881. Longmore was a staunch temperance man and loyal Irish Protestant, described by Deakin as ‘little above the average of the ordinary man in the street’, vituperous and having ‘all a selector’s distrust and all an Irishman’s hate of great landlords’.20

Suitably equipped or not, the commissioners faced an arduous task that not only involved investigating the very divisive Kelly outbreak, but also entailed penetrating the quasi-secret world of detectives and informers. The commissioners, for the most part, manfully took up their work, and Longmore proved assiduous as chairman. During the first series of hearings, when the board inquired into terms of reference 1-4, Longmore was present at sixty-five of the sixty-six meetings convened. The royal commission spanned more than two years, taking evidence from 183 witnesses, and publishing five reports. It stands as the most extensive inquiry ever undertaken of the workings of the Victoria Police. During the life of that commission, the government in Victoria changed three times, a new chief commissioner was appointed, and over three hundred men left or joined the police force.21

As soon as the inquiry began, Acting Chief Commissioner Nicolson and Superintendents F. A. Hare and J. Sadleir were relieved from duty and forced to take leave of absence. Nicolson and Hare, who along with Standish had at different times led the hunt for the Kellys, never returned to duty and were retired from the force as police magistrates. It was a hard decision that not only deprived the community and force of two of their most experienced policemen, but also deprived Nicolson of almost certain appointment as chief commissioner. Nicolson and Hare had been with the force since 1853 and 1854 respectively, and their careers had been exemplary before the Kelly outbreak. Both men had figured in the capture of the infamous bushranger Harry Power in 1870, and Nicolson in particular had built up an excellent reputation in the colony as a thief-taker. Yet the testing nature of the Kelly hunt found them wanting, and also exposed the intensity of their personal rivalry—the commission deciding that the community suffered greatly because of the ‘want of unanimity existing between these officers’. Sadleir, who did not figure in the Kelly hunt to the same extent as Standish, Nicolson and Hare, escaped the full wrath of the inquiry but was found ‘guilty of several errors of judgement’, and he was placed at the bottom of the list of superintendents.

In addition to criticism levelled at the senior superintendents, the commission strongly rebuked several other policemen for their actions during the Kelly hunt. Inspector Brook Smith was accused of ‘indolence and incompetence’, and was forced to retire on a pension; Detective Michael Ward was censured and reduced one grade for ‘misleading his superior officers’; Sergeant A. L. M. Steele was censured for ‘impromptitude and poor judgement’; and constables H. Armstrong, W. Duross, T. Dowling and R. Alexander were found guilty of ‘arrant cowardice’. Armstrong resigned and the other three were dismissed.22

The presentation of the commissioners’ report on the Kelly outbreak concluded the first part of their inquiry into what they termed ‘a disgraceful and humiliating episode in the history of the colony’. The report on the Kelly saga as the commissioners saw it sent shock-waves through the police force. Their frank and hard-hitting account had policemen disagreeing with each other, and prompted impassioned and comprehensive responses from a number of them, including Nicolson, Hare, Sadleir, Ward and Alexander.

Sadleir later accused the commission of using methods that ‘were repugnant to all ideas of justice and fair play’, and he described Longmore as a man who ‘went relentlessly for scalps’, a judgement with which Deakin might have agreed. Yet, for the most part, the plaintive protests of Sadleir and other police were not well-founded. Sadleir in particular bleated about the character of some of the witnesses who appeared before the commission, and the fact that he and his brother officers were not allowed to cross-examine them personally. He appeared to forget that it was a public royal commission, held in an age when even accused persons on trial could not give sworn evidence in their own defence. Indeed, the tenor of his grumblings suggests that, had Ned Kelly been alive, Sadleir would have objected to Kelly’s appearance before the commission on the grounds that he was a ‘disaffected witness’.23

Sadleir’s argument that Longmore ‘went for scalps’ does, however, find support in the commission’s report and it highlights the main weakness in Longmore’s inquiry to that point. Notwithstanding their very broad first term of reference, the commissioners focused almost exclusively on the actions and personal failings of individual policemen and ignored more general social, economic and political considerations. It was an approach that contrasted sharply with the inquiries held at the time of Eureka, when investigators not only criticised individual police but also considered in detail the broader social questions of mining licences, electoral rights and the land question. The Longmore Commission, without even canvassing serious social questions like rural unemployment, land selection and rural class conflict, determined that the Kelly outbreak was rooted in police actions that ‘weakened that effective and complete surveillance without which the criminal classes in all countries become more and more restive and defiant of the authorities’. The almost exclusive attention given by the police commission to individual police failings undoubtedly heightened the sense of victimisation felt by police like Sadleir, and contributed to the commission’s lack of credibility with sections of the press.

Not even Sadleir doubted that a number of individual policemen were culpable, but the general police view was that they alone were not responsible for the Kelly outbreak. It was a view shared by others, including the Kelly Reward Board, which made individual payments of up to £800 to police involved in the Kelly hunt, and the government, which refused to fully act upon some of the Longmore recommendations against individual policemen and later cut across the royal commission’s final terms of reference. Since the Longmore Commission, a number of researchers have identified socio-economic, racial, political and geographic factors as being relevant to the cause and nature of the Kelly outbreak. It is perhaps unfortunate that Longmore—former Minister for Lands and selectors’ advocate—and his colleagues, did not consider these aspects at all in their second progress report. Their failure to do so alienated many honest policemen, and the loss of credibility undoubtedly hindered their work during the second part of the inquiry—generally to inquire into and report upon the state and organisation of the police force.24

The hearings to finalise this last term of reference began in December 1881 and by that time the liberal Berry Government had been replaced by that of the Irish Catholic lawyer Sir Bryan O’Loghlen. O’Loghlen, who had gained office on 9 July as premier, attorney-general and treasurer, headed a ‘scratch team’ comprised of prominent conservatives and discontented liberals. The political turmoil that saw O’Loghlen rise to power did not leave the Longmore Commission or the police unaffected. O’Loghlen appointed Hussey Malone Chomley as chief commissioner of police and instructed him ‘to draw up a special report embodying his views upon the re-organisation of the force’. Longmore and his team initially regarded Chomley’s appointment as an action ‘designed to supersede the commission, or at least to render further investigation superfluous’, and the inquiry was suspended until they received an assurance from the government that such was not the case.

Chomley’s record as a police administrator was not outstanding and did not warrant his sudden and inexpedient appointment as chief commissioner and special adviser during a crucial stage of the Longmore Inquiry. He was an Irish Protestant from Dublin, whose police career began in 1852 when he joined Sturt’s Melbourne and County of Bourke Police as a cadet, and he had risen through all ranks of the force, although his time was spent mostly in rural areas. At the time of the Kelly outbreak he was superintendent in charge of the South-Western District, with headquarters at Geelong, and at the time of Ned Kelly’s capture Chomley was in Brisbane on police business, which was fortunate for him in that he did not become involved in the hunt for Ned Kelly or the police commission’s ‘scalp hunting’. When Graham Berry removed Standish and left the chief commissioner’s position vacant, Chomley was third in line for the post, after C. H. Nicolson and F. A. Winch, and was hotly pressed by younger and more accomplished men like Hare and Sadleir. The chances of the other four being ended, Chomley was left as the most senior man in the force. He was not, however, insensitive to the circumstances that placed him in such a fortunate position and felt obliged to make public a copy of a personal letter from Standish, in which Standish had written, ‘I beg to say that you never at any time showed the slightest disinclination to proceed to the North-Eastern district in connection with the pursuit of the outlaws’. At the age of forty-nine H. M. Chomley became the fourth chief commissioner of the Victoria Police Force and the first career policeman in the colony’s history to fill the senior police post.25

Chief Commissioner H. M. Chomley

In one sense Chomley’s appointment marked the stage the force had reached. During the years when Mitchell, MacMahon and Standish were appointed it was unthinkable to choose as chief commissioner a man who had joined and served in the ranks. On the other hand it might have reflected the slogan of O’Loghlen’s conservative government—‘peace, prosperity, progress’—in that Chomley was loyal, honest, disciplined, conservative and a man ready ‘to sacrifice a good deal as long as things went smoothly’. So police organisational development and political conservatism came together in fortuitous circumstances after the turmoil of the Kelly outbreak. From the outset, however, it was evident that the head of the force lacked the intellect and administrative ability of his three predecessors. His ‘easy-going disposition’, ‘genius of commonsense’ and ‘long apprenticeship to police work’ were no doubt handy attributes and a stabilising influence on the force, but his brief, simplistic report to the O’Loghlen ministry on the state of the force highlighted his prosaic nature. The Longmore Commission rightly dismissed Chomley’s modest suggestions for reform as ‘sanguine anticipation’, and forged ahead with its own undertaking.26

The final three police commission reports were concerned with the inquiry’s fifth term of reference, which did not directly touch upon the Kelly outbreak. All the reports, however, owed their existence to the Kelly Gang. In these later sessions the commissioners displayed a greater sense of balance than they had in their Kelly Report; broader social issues, such as larrikinism, prostitution, liquor control and gambling were investigated during the hearings. Individual policemen still figured prominently, and a number were censured in unmitigated language. Superintendent F. A. Winch and Sub-Inspector J. N. Lamer were both found guilty of corrupt practices and retired from the force on a pension. Winch, who held the key position of superintendent in charge of the Melbourne Police District, had a history of corrupt behaviour over twenty years but all that time had been shielded from public exposure, criminal charges and dismissal by his good friend Chief Commissioner Standish. With the retirement of Standish, Longmore used the full power of the royal commission to rid the force of Winch, who even then escaped criminal charges and was allowed to retire with a pension. For personal gain Winch had allowed prostitution and gambling to flourish in Melbourne and ensured that zealous and honest police did not ‘grapple with the evil’. Lamer, who some years earlier had figured so prominently in the Clunes riot, was not as crooked as Winch; the basis of his offences was the regular borrowing of money from hotelkeepers. In an unusual twist for the Longmore Commission, Lamer admitted his guilt but ‘urged in extenuation the great expense to which he was subjected in consequence of his promotion’.27

A number of other policemen were individually censured by the royal commission for general acts of inefficiency and misconduct, but these cases were minor compared with the damning condemnation levelled at the Detective Branch as a whole. This section of the force was described as ‘a standing menace to the community’, ‘a nursery of crime’ and a department ‘inimical to the public interest’. Commanded by Inspector Secretan—‘one of the most useless men in the service’—the detective force numbered twenty-six men. The Longmore Commission recommended that Secretan be retired and the detective force disbanded, and a new Criminal Investigation Branch formed as part of the general police force under the command of the chief commissioner. This was in some ways a curious development as only six years earlier the Metropolitan Police in London had abandoned this form of organisation and replaced it with the more autonomous model then in use in Victoria. Nevertheless, a century later, in the 1970s, the London CID was again made part of the general force, in a bid to reduce corruption and inefficiency among detectives. So the Longmore Commission might have recommended wisely.28

The basic fault with the detective force was that its mode of operation had changed little from the convict years. The methods that had produced successes for detectives during the 1840s and 1850s, when the population was much smaller and unsettled, were not nearly so effective in later years. Originally a small, select group, the detectives were judged efficient as thief-takers because they infiltrated the criminal classes and by fraternising with criminals were privy to information that was not readily available to other policemen. The detectives initially made many arrests but, as the population increased and settled over a wider area of the colony, they only increased in number and failed to adapt to the changing economic and social conditions. They did not develop any special investigation skills but continued to rely simply on the use of informers and ‘fiz-gigs’. Under this system, criminals and others were employed by detectives and paid ‘secret service money’ for details about crimes and the whereabouts of offenders. It placed the detectives in close contact with men and women of the criminal class and gradually rendered the detectives ‘comparatively helpless’ and by themselves ‘almost powerless to trace offenders’. The informer system worked well among the Vandemonian population in the seedier parts of Melbourne during the early years but was found wanting during the hunt for the Kelly Gang, when police could not effectively induce enough people in the north-east to inform on the outlaws. The essential ingredients of the system were infiltration and betrayal, and a mixture of rural sympathy for the Kellys and fear of them rendered the detective system virtually impotent. Fear of the gang was not without foundation, and stark evidence of the precarious world of the police informer was provided when Joe Byrne executed one of the few police spies, Aaron Sherritt, as a prelude to events at Glenrowan.

A ‘fiz-gig’ is paid to start the prey which the expectant detective captures without trouble or inconvenience. He is supposed to receive not only a subsidy from the detective who employs him, but a share in the reward, and a certain immunity from arrest for offences with which he may be chargeable. He may plan robberies and induce incipient criminals to co-operate, but provided he lures the latter successfully into the detectives’ hands, his whereabouts and antecedents are not supposed to be known to the police.29

It was the basic informer system, with various modifications, that Superintendent C. H. Nicolson and Detective Michael Ward tried constantly to use against the Kelly Gang. Nicolson in particular had great faith in the system of spies and informers, and his network included ‘Diseased Stock’, arch-spy of the Kelly years. Such activities were still common outside Victoria; although overseas scholars, including Hans Gross and Alphonse Bertillon, were pioneering scientific investigation methods, detective work around the world was dependent upon ‘native skill and cunning’. Indeed, even the much-vaunted sleuths of Scotland Yard were denounced by the British prime minister as being ‘especially deficient as a detective force’, and labelled in Punch as the Defective Department. Longmore’s devastating criticism of the Victorian detective force was aimed not so much at the inadequacy it shared with most of its counterparts elsewhere, but at the sinister lengths to which the ‘fiz-gig’ networks had developed.30

In its assessment of the police force generally, the Longmore Commission touched upon such matters as recruiting, training, promotions and transfers, and concluded with a list of thirty-six recommendations for the reform of the force. Certain of the recommendations related only to routine matters, such as the abolition of white gloves for men on patrol. Other proposed reforms were more important and included instructional classes and promotional examinations for police, the compilation of a police code and new recruiting procedures. Also contained in the list were the perennial issues of police enfranchisement and a proposal to vest the management of the force in a board of three men.31

The final Longmore report highlighted yet again the characteristic inability of most senior police willingly to undertake reform and adapt to changed circumstances. Since 1852 important changes had been forced on the police by outside inquiries, and in 1883 the effort was repeated by Longmore. Sturt, Mitchell, MacMahon and Standish had all displayed remarkable adaptability and a desire to introduce reform when first appointed from outside the police sphere. The impetus given to the force by these administrators was not sustained but languished, particularly during much of the Standish era. It is also evident that the older and more senior career police generally lacked the intellect and administrative ability of leaders appointed from outside the force, and did not engender the supportive climate so necessary for innovation and reform. Their world was largely insular and reactionary, and was illustrated by Sadleir’s vehement criticism of basing police promotion on a system of written examinations.

The Kelly Gang exposed serious police weaknesses in the field, including a general lack of bushcraft, horsemanship and firearms training, together with lax discipline, low morale, and an inability to relate to sections of the rural community and maintain their confidence and respect. These shortcomings were ultimately attributable to mismanagement at a senior level, and the Longmore Commission exposed serious deficiencies in the force’s administration: a lack of provision for police training, poor planning, injudicious manpower deployment, insufficient attention to ordnance requirements, sub-standard officering and the generally debilitating leadership of Standish, which ‘was not characterised either by good judgement, or by that zeal for the interests of the public service which should have distinguished an officer in his position’. Ironically, many of the changes mooted by Longmore were originally suggested by police from the lower ranks but had never been acted upon by Standish or his senior officers. Internally and externally the senior police were seemingly committed to maintaining the status quo.32

The history of public inquiries into the Victoria Police Force before the Kelly outbreak proved them to be valuable community forums where important reforms were germinated and cancerous sections of the force were exposed and excised. The Longmore Commission had this effect, and if the enormous expense and tragedy of the Kelly outbreak was ever at least partly redeemed, this was one way it occurred. The Longmore Commission was far from perfect and did not provide a panacea for all ills. Nonetheless, the force was cleansed of some of its more openly corrupt influences, aged and ineffective senior police were retired and many important administrative changes were introduced. Most importantly, however, the force was once again exposed to searching public scrutiny, and sections of the community and many policemen were moved to take more than passing interest in the state of the force and the doings of its senior officers. The long term of Standish’s commissionership had lulled many people into thinking that all was as well as possible with the colony’s police, quite a few of whom had been basking comfortably in a widespread belief that Victoria’s police were the finest in Australia. It was a debatable notion; even if it had been well founded, it would not have warranted any resting on laurels. In 1878 it was certainly not a view shared by Ned Kelly, and by 1883 there were many others who agreed with his assessment.33

Many persons think that a policemen’s lot is an easy one. It is really nothing of the sort …

John Sadleir, Recollections34

John Sadleir’s lament no doubt found its inspiration in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance, which parodied rustic police and criminals. Although first performed in New York (1879) and London (1880), its sentiments were equally felt by many policemen then working in Victoria.

The Kelly outbreak and the Longmore royal commission diverted attention away from the ‘ordinary copper’ and focused it firmly upon the dramatic and sometimes scandalous lot of senior policemen like Standish, Winch, Nicolson and Hare. The tendency to focus on those in the limelight was natural, but it cast into shadow many hundreds of urban and rural policemen who were not directly involved in the Kelly hunt, whose footsteps never ceased in towns across Victoria. They were the bulk and backbone of the police force, and to bring the everyday world of the constable into sharper focus gives a necessary balance to the Kelly–Longmore years.

A constable and his makeshift police station in Gippsland, about 1900

The 1880s saw the disbandment of Stubbs’s Bulldogs and the separation of police recruiting from that of the defence forces, which suited the police very well. Entry into the foot police became open to men ‘under 30 years of age, at least 5 ft 9 in. tall, who were smart, active and could read and write well’. Mounted recruits had to be under twenty-five years of age, at least 5 ft 7 in. tall and weigh under 11 st. 7 lb. In the 1880s, as in the 1860s, the emphasis was on physical attributes, as long and wearisome periods of beat duty and mounted patrol were the staple of a constable’s working life. The requirement that they ‘read and write well’ was very elastically applied, for the force included ‘lots of men’ who could barely write, and the only educational test for recruits was a basic dictation and spelling exercise. There were no university graduates in the force but a spirometer test did ensure that policemen had the lung capacity for strenuous outdoor work. Upon joining the force men were not given any classroom instruction in their duties; once outfitted, they were sent to police stations for beat and patrol duty. In the case of mounted recruits that often meant the testing and solitary life of a one-man station in a remote mountain district or the Mallee–Wimmera. The policy of sending new police into the fray without any training or preparation was a legacy of Standish’s administration and reflected his philosophy ‘that a constable is born, not made’. It was this policy that saw some young constables, ‘raw, and knowing no more about the police duty than a man from North Africa’, pitted against the likes of Ned Kelly. Through no fault of their own, policemen were at times embarrassed and admonished because they lacked bush skills or knew little about laws, firearms, horsemanship, tracking and police patrol. Many of them did well just to survive; only a minority were natural policemen, like Constable Robert Graham who had charge of the Greta police station after the execution of Ned Kelly. Graham, a native of Victoria and an accomplished bushman and horseman, displayed considerable courage and intelligence in hostile Kelly country. He not only survived but effectively policed the district and won the support of many local people. A sign of his competence and fairness was the mutual respect that developed between him and Ellen Kelly—Ned’s mother. When Graham had trouble with some of Ned’s former cronies it was Mrs Kelly who helped him and kept the peace. Graham was officially commended for his work at Greta and later promoted. His skills and reputation were, however, unusual and could never justify the overworked excuse that policemen were born, not made.35

The basic starting wage of a constable was 6s 6d a day and out of this money the new recruit was expected to pay £12 for his police uniform of tunic, trousers, shirt, jumper, white gloves and boots. His shiny black helmet, worth nine shillings, and other accoutrements, were issued free by the force. Unless a constable had some money saved, the first weeks of his new job placed him under considerable financial strain and many men took at least a year to clear their uniform debts. Dress standards, including the changing of underpants, were governed by regulations, and constables were paraded regularly and instructed to replace worn or damaged clothing at their own expense. Apart from the cost of uniform items, constables complained about such things as a lack of proper wet-weather gear, the oppressiveness of tunics and helmets in summer and the useless, ornamental nature of white gloves and swords. In a style befitting The Pirates of Penzance, hapless Constable McEvoy described the lot of a white-gloved constable:

I have often felt ashamed on the wharf; having to take a drunken man, I took my gloves off. I met an old drunken woman in the street, and had my gloves on; I had not time to take them off. I was trying to take off my glove, and had my hand round her, and had to put my hand up to my mouth to take the glove off, and they had a great laugh at me, as if I was going to kiss the old woman. They are an ornamental and useless thing.36

Constable James Thyer

The constables’ basic wage fell between the rates paid to tradesmen and labourers and was generally less than the pay of other civil servants, transport workers and even shop assistants. Married constables in particular found it difficult to support a family on such low pay, when living expenses included rent of fifty shillings a month, bread at 6d a loaf, milk at 6d a quart, mutton at 4d a pound and firewood at 1s 3d a cwt. Due to such costs it was suggested that young police recruits be prohibited from marrying for five years so that they could pay for their uniforms and then save money to provide for a family. In 1881 constables petitioned the chief secretary for a pay rise and in support of their claim sought to highlight the unique and arduous nature of their duties. They worked a seven-day week, with no rest days or public holidays, and were granted only twelve days leave a year. This was in contrast to all other civil servants, including charwomen, who were paid annual wage increments, and received at least one rest day each week, ten public holidays a year and twenty-one days paid annual leave.37

The Police Regulations required constables to rise no later than 5.30 a.m. every day (6.30 a.m. in winter) and after dressing and cleaning their rooms, they were to be at stable parade by 6 a.m. For those men not working night shift, curfew was 10 p.m. Beatmen in Melbourne and the larger towns rose about 4.30 a.m. and worked a constant round of shifts that commenced daily at 5 a.m. Day duty of eight hours was divided into two four-hour reliefs, broken by four hours of reserve duty, which meant that a constable who started work at 5 a.m. did not go off duty until 5 p.m. Night duty was a fixed shift from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m., and constables worked this continuously for fourteen days before rotating back to day shift. Such hours of work were themselves tiresome but in the 1880s they were not unique to the police. Bakers, butchers, transport workers and shop assistants were just a few of the other occupations in which employees regularly worked up to ninety hours a week. Where the police differed was that they were paid less for their labour and worked every day: no Sunday rest day, no Christmas Day holiday and no public holidays. Even the toughest of other occupations usually granted some time off on Sunday, and most workers in sales and commerce worked a five- and-a-half-day week. Leave of absence was granted to constables only if they could be spared, and even then they were ‘to consider themselves subject to every order, rule, and regulation of the force’ and needed special permission to visit Melbourne.38

The inequities in benefits and allowances were not limited to differences between married and single men but were also evident in the payments to officers, who received much larger allowances for fuel and travelling and were paid transfer expenses. All policemen were entitled to a wood allowance and in winter married constables received 6 cubic feet a week, which they protested was ‘not sufficient to boil a kettle’. They pointed to officers who, regardless of their home or family situation, were allowed 20 cubic feet of firewood a week. By protesting in such terms the constables were out of order for Victorian times and met with little success.39 Privileges of rank were common in the force, and the constables, not really expecting full parity with officers, might have used the ‘kettle boiling’ issue as a device to lead into another issue that they saw as the real grievance.

This was the hardship involved in transfers and transfer expenses. Over a period of years, constables pushed for changes to the system. There were more than 330 police stations scattered throughout Victoria, some in locations as remote and distant as Bendoc, Corryong, Dartmoor and Cowana. The Police Regulations stated that police were distributed ‘as the requirements of the country demanded’, and policemen were liable to be transferred to any station, at any time, for any reason. There was no right of appeal. What worried the men even more was that a transfer involving a move to another town or suburb had to be paid for by the policeman being transferred. Officers were paid a transit allowance for 2 cwt of luggage, but other ranks received nothing. Chomley agreed that such a system caused great hardship and, depending on the distance of removal and the amount of luggage, it was not uncommon for constables to incur large debts for removal expenses. Efficient men suffered most, as they were moved about very often, at their own expense, ‘for the good of the country’. Misjudged men also suffered because forced transfers were declared in the regulations to be a legitimate ‘punishment’ and, without trial or appeal, constables could be capriciously shunted about the colony, dragging their families behind them.

Another example of this mean type of administration was the decision by Standish, during the Kelly hunt, to cancel the travelling allowances of all those Melbourne constables engaged on the hunt in the north-east. He transferred them indefinitely to the strength of the local police district to save paying the five shillings a day travelling money for being away from home. Married men either had to leave their families behind or themselves pay to move them to the north-east. Standish argued that his decision saved the government money, but he did not cut the travelling allowance of twelve shillings a day paid to officers in the north-east. Later, he admitted that many of the men worst affected ‘were married men separated from their wives and families’.40

The regulations controlling transfers and allowances were part of a much larger code of rules that governed the daily lives of policemen. It was not a code restricted to official matters but one that sought to control their personal conduct and private lives at all times. Policemen could not vote at elections and were to ‘observe strict neutrality in all matters connected with polities’. No constable could marry without permission and then only after his intended wife and her family were judged unlikely ‘to bring discredit on the force’. They were not allowed any outside employment and, ‘unless by special permission of his Officer’, no constable was to allow his wife ‘to practise any profession, trade or business’. Except on necessary duty, policemen were prohibited from frequenting places of amusement or public houses. They were not allowed to incur debts or obligations that might ‘shackle their exertions’ and were expected to ‘at all times and in all ways maintain a character for unimpeachable integrity’. Married constables were directed to live as near as possible to their station and all members, whether on duty or not, were to ‘at once turn out when called upon in cases of emergency … or whenever required’. Policemen were not paid overtime; extra duty was regarded as being part of the job. A particular source of frustration to married men was the requirement that, no matter where they were stationed or what their family situation was, if they were injured or fell ill they had to go to the Police Hospital in Melbourne. This often meant leaving their families behind and hundreds of miles of travel. It was intended to reduce malingering, but was regarded as being unduly harsh, particularly as patients in the Police Hospital had half their wages stopped to pay for meals and medical expenses. One constable described the Police Hospital as ‘a good place for loafers’ and those young fellows ‘suffering from venereal disease’, but ‘a great hardship’ for a married man, with his own house, his own doctor and his ‘own comfortable bed’.

When not ill or called upon after hours, married constables presumably sought some sanctuary from the Police Regulations at home. For single men in barracks there was no respite. They were not allowed to smoke or gamble in barracks, their rooms, beds and clothing were subject to inspection, and regulations governed cleaning and bed-making procedures. As the barracks usually formed part of police stations, constables were also directed that at all times they ‘will stand at attention, or, if sitting down, will rise when officers or persons entitled to a salute are passing’. In the age of social distinctions and sweated labour, police conditions of work were not unusually severe. They were, however, indicative of a regimented and all-consuming lifestyle, where the line between on and off duty was barely perceptible. Policing was not just a job but a way of life, and the men in blue serge whose duty it was to superintend the lives of others were themselves closely supervised and controlled.41

A principal legacy of the Kelly outbreak is the popular notion that police work was haphazard and the police themselves generally inefficient. It is an exaggerated notion, given some credence in police behaviour during the Kelly hunt, but not generally applicable to policemen and police work of the period. The Kelly saga was an extraordinary series of events that highlighted particular police inadequacies and belied the fact that most police work was routine and completed satisfactorily according to set procedures. Policemen, particularly during the early years of their service, had their shortcomings but, once they overcame their initial lack of training, average constables completed many demanding tasks. The majority of constables spent their working day either on beat duty or mounted patrol, while a minority of them worked as clerks and watch-house keepers or performed extraneous duties, including guard duty at Government House, Parliament House, the Royal Mint, Public Library, General Post Office and University Gardens. Beat duty was confined to Melbourne and the larger towns, and the beat constables themselves were as much a part of the city streetscape as were veranda posts and street lamps. Constables patrolled set beats alone and on foot and, in rotating shifts, they were there twenty-four hours of every day. These men were not detectives; although crime prevention was an element of their presence, their primary role was a service one. They were ‘the proper class to be applied to for assistance’ and, to this end, beat constables were instructed to acquire local knowledge of all kinds and to ‘in fact be a walking directory’. The need for civility and politeness was stressed. They checked the security of doors and windows, and were alerted to watch for leaking waterpipes, overflowing closets and dead animals lying about. They were also responsible for obliterating obscene words and drawings in public places and to ‘in every way diminish as far as possible, the risk of accident to the public’. In the interests of public safety no task was too menial, and beatmen were specifically directed to watch for and remove pieces of orange peel from the pavement.42

Beat duty regulations were enforced by sub-officers and officers using a system of reports and monetary fines. It was a system that showed that the regulations only outlined the beat duty ideal and could not guarantee universal compliance or commensurate performance. It was also a system that struck hard at the earnings of policemen, who were liable to fines of a week’s pay for being drunk on duty, and a day’s pay if found sheltering under a veranda or dawdling on their beats. There were still a number of constables who were alcoholic, lazy or just plain unlucky, and discipline charges were not uncommon. These covered a wide range of conduct, from simply being late for duty to the serious offence of assaulting a prisoner. Some of the more common breaches were: absent from beat, improperly working the beat, asleep on beat, sitting down on beat, in a hotel on beat, found gossiping, drunk on duty and loitering under a veranda. Many constables were never charged and led exemplary careers that included awards, rewards and high public praise. Others, like Constable M. Carroll, ‘a drunken, useless man’, amassed seventeen convictions for offences committed while on duty.43

In rural districts the local equivalent of the beat constable was generally the mounted trooper. These men were often responsible for patrolling large tracts of country and it was expected that they be competent horsemen with a knowledge of the bush and an ability to go it alone. The Kelly outbreak left many people with the impression that policemen were bumble-footed urbanites. However, the daily routine of many mounted policemen necessitated patrols to outlying farms that sometimes took days on bush tracks and over unsettled country. In one noted case, Mounted Constable Samuel James Fane of Alberton, near Yarram, completed a month-long patrol of over 600 miles, tracking a suspected horse thief. In the process he lost his police revolver and his pack horse fell down a slope and disappeared into the Mitta Mitta River. As meritorious as it was, his epic journey was not sufficient to ensure his continued employment as a constable. Like many of his contemporaries he succumbed to the temptations of the flesh and was discharged from the force for discipline offences that included ‘carrying a female on his horse’ and ‘being found in a house of ill-repute for three quarters of an hour’.

A country trooper was not only expected to be a ‘walking directory’ but ‘to make himself as thoroughly acquainted as possible with all the peculiarities and characteristics of the part of the country over which his duties range’, including the natural features of the country, all the roads and bush tracks, the nature of the soil and other topographical features. Some of the mounted men never came up to standard, but the acquisition of local knowledge and bush skills was regarded as an ongoing activity, and troopers were encouraged to use different routes and to ‘proceed through the bush, and call at the houses of settlers to learn what is going on’. The early police historian, A. L. Haydon, felt that there was ‘an appealing picturesque touch’ about the solitary trooper, ‘a highly important personage’ and ‘ruler of a good many square miles, doing several men’s work in one’. He perhaps romanticised, but he had a true sense of the individuality and authority of the mounted trooper. Rural mounted men were key official figures who did more than police work in the generally accepted sense. In small rural communities they served as a general government representative and their wide-ranging duties included the collection of agricultural statistics, enforcement of compulsory vaccination programmes, truancy prosecutions, handling mental health cases and bushfire prevention.

Non-police tasks such as these were categorised as ‘extraneous duties’, and the diversity of such roles that police were called upon to fill was almost limitless. One case that highlighted community expectations in this regard was that of Mounted Constable Norman McPherson of Buchan, which was reported widely in the rural press under the heading ‘Police Constable as Undertaker and Parson’:

Many duties fall to the lot of a policeman, but few members of the force are called upon to act as coffin-maker, undertaker, and clergyman, as Trooper McPherson had to do a few days ago in the lonely mountains near Buchan. Charles Emil Gerlach, an old resident of the district, died, and the Constable was called in in his official capacity. There was no undertaker in the district and the nearest carpenter was sixty miles away. Constable McPherson, therefore, made a coffin out of the pine boxes and helped to dig the grave. Reverently, as at the most orthodox funeral, the box containing the remains of Gerlach was lowered into the grave, and in the absence of a clergyman the constable impressively read the burial service and assisted to cover the remains and fill the grave.44

Trooper Norman Bruce McPherson, Buchan police station

Each country trooper was required to maintain a weekly ‘Diary of Duty and Occurrences’ in which he recorded not only his own activities but also the work performed by police horses. A typical one-man police station was located in the quiet and settled farming district of Mount Moriac near Geelong. This station was manned in 1871 by Constable N. Hagger, who was the local policeman to 3300 people living in the Shire of Barrabool. Figure 1 is a copy of entries from Hagger’s duty book. His records also show that in the weeks before and after those entries, his working day of up to twenty-four hours was occupied cleaning the police station, serving summonses, and attending to reported cases of larceny, an insane woman, a missing person, the death of a boy, cruelty to cattle and the concealment of a birth. He also made regular mounted patrols of up to 35 miles a day, and was visited by his inspector. His work routine was typical of that experienced by most rural mounted troopers in the last decades of the nineteenth century.45

FIGURE 1

Entries from Constable Hagger’s duty book, 5–11 November 1871

Source: Victorian Public Record Series 844, Vol. 1, Ref. 38/4/2

* Martha Hunter, mentioned in the Special Occurrences column, was a local servant girl charged by Hagger with ‘concealment of birth’ for allegedly killing her baby son shortly after she gave birth.

Hagger was a married Englishman then aged 36 years of age. A former member of the Mauritius Police and Bombay Horse Artillery he joined the Victoria Police Force on 3 March 1864 and his record includes a commendation for his part in the Kelly hunt. He was certified insane and discharged from the force in 1882 but during this time at Mount Moriac he was rated by his superiors as ‘careful and efficient’.

Hagger had an unblemished career that lasted eighteen years, until in 1882 he was declared a lunatic and discharged from the force as medically unfit for police duty. Premature retirements from the force on medical grounds were not uncommon and long-term police work was recognised by authorities both in and outside the force as taking a heavy toll on the physical and mental health of policemen. The daily, all-weather, outdoors regimen of beat constables and mounted troopers was often lonely, tiring and uncomfortable. The pattern of police work usually comprised extended periods of routine duty, often boring, interspersed with stressful events when lone constables needed to think and act quickly in response to acts of violence, crimes and other crises. Chief Commissioner Chomley expressed the view that ‘after twenty years police service a man is generally done for’, and this was a view shared by the police medical officer, who felt that ‘the continual wear and tear of a policeman’s life tells very much on their constitutions’. Medical witnesses before the Shops Commission gave evidence about the effects of long hours, shift work and continual leg-work on the health of workers. It was not an inquiry concerned with the health aspects of police work but the evidence given was equally as relevant to policemen as to other workers, in an age when the common work-related ailments of policemen were consumption, rheumatism, catarrh, sciatica, bronchitis and varicose veins. The Longmore royal commission accepted the proposition that constables at fifty-five years of age were ‘unserviceable’ owing to the ‘debilitating effects of their duties’, and recommended that all policemen who attained that age be allowed to retire on a pension.46