The police strike and the events that followed it highlighted the importance of having capable leaders in the senior ranks of the force. It was not enough that they had a sound record of police service; as well as being able to earn the respect and support of subordinates, they had to be at least receptive to new ideas and adaptable to pressures for change. After the strike, the government appointed Major General Sir James McCay as head of a Special Constabulary Force (SCF), to help maintain law and order while the regular force was rebuilt. The two forces co-existed for a few months before the SCF was disbanded, but it was long enough for McCay to overshadow Nicholson and show that there was a wealth of management skills available to the police from outside their ranks. Nicholson was not up to the task and, partly due to his failings, he was the last chief commissioner to be appointed from within the force for almost forty years. The three successive chief commissioners were all ‘outsiders’: Brigadier General Thomas A. Blamey, Alexander M. Duncan and Major General Selwyn H. Porter.

The role of the commissioner was one of the most important factors affecting the fortunes of the force—second only to the influence of the general community itself. This importance was evident not only in the era of Blamey, Duncan and Porter, nor only in the twentieth century, but it was during and after the police strike that the subject of police leadership became an especially important public issue, inflamed by Blamey’s controversial activities and the importation of Duncan from Scotland Yard.

Blamey, Duncan and Porter worked without the support of deputy or assistant commissioners and, aided only by small personal staffs, they shouldered enormous responsibilities. They were the force’s main public figures and spokesmen, and their decisions touched almost every facet of the force’s operations. In addition to superintending all manner of internal changes and duties, the personal influence of the three men was to be found in broader social issues, such as police attitudes and activities during the Depression, the police war effort and the force’s approach to changed juvenile behaviour during the 1950s.

When the chief commissioner was vibrant, introduced reforms and enjoyed public support, the force as a whole generally reflected it. When he waned, the force waned with him.

The police of Victoria are still under the control of the Chief Commissioner. The special police, a special body, existing only for special purposes, and for a limited time, are under the control of Sir James McCay.

By 17 November 1923 the violence and mayhem that marked the early days of the police strike had passed, and the attention of many people turned to the ongoing need to maintain public order and the urgent need to rebuild the police force. Never before in Australia had a community been so ‘let down’ by its police and so obliged to take the protection of lives and property into its own hands. Such was the loss of confidence in Nicholson and his depleted force that many people in Victoria looked again to someone of Monash’s type for succour, and approved of Sir James McCay’s appointment as commander of the SCF, which was briefly the larger of Victoria’s two police forces and had the finest commander. Nicholson found the role of second fiddle an ignominious sequel to the strike, but McCay was a highly educated lawyer and an experienced military commander, and had added status in his knighthood; his knowledge of people and network of contacts were beyond the reach of the plain man from Ballarat. McCay fitted readily into the role of leader, and not only commanded the SCF but also joined his efforts with Nicholson’s to rebuild the regular police force. There were some expressions of concern that he had ‘superseded’ or ‘displaced’ Nicholson, but this was temporary. The SCF was only an interim force, and Nicholson was not destined always to work in McCay’s shadow: he remained in office until mid-1925, whereas McCay and the SCF had gone by mid-1924. Nevertheless, that short-lived special force deserves scrutiny.

The headquarters of the SCF was located in the repatriation building at Jolimont. Theoretically an independent adjunct to the regular police force, the SCF became the gateway to the regular force. By government decision, and much to the chagrin of Nicholson’s recruiting officers, no man could join Nicholson’s force without first serving in McCay’s. Officers from the regular force conducted an intensive statewide recruiting campaign that netted an average of one hundred recruits a month, but these men were not immediately available to Nicholson as they were all first inducted into the SCF. As McCay reminded Nicholson, ‘I will supply such number of recruits each week as you wish. But of course my supplying them to you is entirely dependent on your first supplying them to me, as we both know’. This arrangement existed to minimise the risk of SCF members being ostracised as a ‘scab’ minority when they joined the regular force, but it also inflated the importance of the SCF, which had its own corps of officers, its own uniform and its own code of police conduct, and which, with a strength of 1380 men, was the third-largest force in Australia. Unlike the thousands of men who rallied to Monash’s side and volunteered for service as special constables during the police-strike emergency, the men of McCay’s SCF were paid employees whose wage of fifteen shillings a day was higher than the twelve shillings paid to junior constables in the regular force.

The duties and arrest powers of the SCF were almost identical to those of the regular force, and men from both forces worked together at suburban police stations. The main differences between them lay in their degree of public acceptance and their levels of efficiency. The Labor Party viewed the SCF with distaste, and this view was matched by many people in working-class suburbs, especially Collingwood and Northcote, where it was not considered safe for ‘specials’ to venture alone. The authorities had trouble finding living accommodation for specials in these suburbs, and at certain times they were compelled to patrol in groups of four to ensure their personal safety. The labour movement generally supported reinstatement of the police strikers, and it was felt that ‘scabs’ of the SCF were thwarting that objective.

Some of the specials themselves did little to enhance their collective image. Complaints of officiousness and excessive use of force were common, and two of them were involved in a widely publicised case of attempted extortion. The Labor Party expressed alarm at what it regarded as a ‘large number of grave offences committed by special constables’ but, given the size and nature of the SCF, the extent and degree of Labor criticism were unwarranted. Ninety-eight specials (about 7 per cent) were discharged for misconduct, but thirty-six of them were for being absent without leave and twenty-one for being ‘undesirable’.

Much of the trouble with members of the SCF was due to their hasty recruitment and lack of training, and the transitory nature of their role that often saw them go from civilian, to special, to constable, all in the space of fourteen days. Members of the regular force were instructed to treat the specials ‘on the same basis as they would treat raw recruits’, and were advised that as ‘these specials have not had any training in police duties, mistakes and errors of judgment in the performance of their duties must necessarily arise’. Taken overall, the work of the SCF was creditable and, while Nicholson rebuilt his force, the auxiliaries added useful weight against further outbreaks of serious crime and violence. Opponents of the SCF levelled many criticisms at it but never suggested that it was ineffective. It was an expedient for putting ‘policemen’ on the streets and, on occasions like New Year’s Eve, the bolstering of regular police ranks with specials was the salutary difference between a night of rejoicing and a night of rioting.

Andrew Moore is one historian who has looked at the role of special constables, but he approaches the question in doctrinaire fashion and views them as the sinister manifestation of some secret right-wing movement. There is more point of view than hard evidence behind such a proposition, and Moore appears unwilling to accept as a real possibility that the formation of the SCF was a spontaneous and even natural reaction when a community was in crisis, and was forced by the unprecedented breakdown of its regular police force to take steps to secure the order and safety desired by most people. One review properly describes Moore’s argument as over-dramatised and his sources as ‘sparse’, and says of his secret army theory, ‘one needs something more substantial than suspicion of an “unseen hand”’. Certainly some working-class areas showed even more active dislike of the specials than they normally did for any policemen, and many unionists were resentful of them on good union principles; but probably most Victorians simply wanted to feel safe by having sufficient ‘policemen’ on the streets, which might be conservative but is hardly sinister. If police militancy suffered a sad blow, that was quite in harmony with the accepted views of a great many Victorians, including non-union wage-earners and their dependants. If it was a plot, it was singularly ill-planned: so unprepared for it was everybody that even the supply of boots and batons to the specials caused acute problems.

During the period from December 1923 to May 1924 a total of 694 men transferred from the SCF to the Victoria Police Force, which was thus brought back to full strength in only six months. The remaining members of the SCF, including McCay, were demobbed during mid-1924, and on 1 August 1924, a special meeting of justices of the central bailiwick formally disbanded the SCF when they decreed there was ‘no further cause to apprehend that ordinary constables and officers appointed to preserve the peace, are insufficient for the purpose’. From that date Victoria again had one police force and Nicholson stood alone as the state’s most senior policeman.1

Although at full numerical strength, the force was not regarded as being up to its pre-strike standard. The average length of service of the strikers was five years, and service in individual cases ranged up to twenty-five years, with 135 of them having served for more than ten years each. It was not possible in the space of a few months to impart this level of experience to new recruits, and although former officers were retained as instructors, it was not even possible to give each recruit the standard seven-week training course. The Monash royal commission acknowledged that one consequence of the strike was a ‘lowering of efficiency’ that would take ‘two or three years entirely to repair’, but it was also acknowledged that the general education level of the new men was higher than that of the police strikers they replaced. Reduced efficiency was a difficult variable to measure and was not at once obvious to many people. A matter of greater concern to the public was ‘the number of young constables of small stature to be seen on duty in the city’. In order to bring the force more quickly back to full strength after the strike, and to open the force to more returned soldiers, the minimum height requirement was reduced by 1 inch to 5 ft 8 in. Throughout efforts to rebuild the force, first preference was always given to returned soldiers, and they comprised 56 per cent of the SCF. A 1-inch reduction was not unreasonable but it did run counter to police tradition. Long before they introduced minimum education standards, police forces had minimum—and arbitrary—height requirements: in London 5 ft 7 in, in Victoria 5 ft 9 in, and in New South Wales 5 ft 10 in. In 1924 tradition dictated that ‘a foot policeman in uniform should by his obvious physical proportions and strength command a respect for his capacity to deal with every situation demanding a physique well above the average’. The post-strike recruits were criticised for being ‘jockey-size’, and their ‘small stature’ so worried many people that in April 1925 the minimum height was restored to 5 ft 9 in.2

Although the police strike may have had some damaging effects on the efficiency and physical appearance of the force, it did bring about significant improvements in the work conditions of Victoria’s police. (The only men not to benefit from the strike were the strikers.) In the wake of the strike, the government and the force administration introduced a series of reforms designed to attract recruits and to reward those men who remained loyal. The strike prompted more improvements in police work conditions than constitutional means had achieved in the previous quarter of a century, and these reforms served as the corner-stone of efforts to rebuild the force.

On eight separate occasions during the period 1903 to 1921, members of the force made formal representations to the government for the reintroduction of police pensions. All of these were unsuccessful, the best that the police could elicit from the government being Lawson’s 1920 election promise that was broken. However, within weeks of the strike, a Police Pensions Bill was rushed through parliament and became law on 1 January 1924, providing all police with comprehensive pension entitlements, including disability payments and allowances for widows and children. Also, police were given a small increase in pay that raised their minimum yearly salary to £220, and brought them closer to the New South Wales Police. A good-conduct scheme was introduced, so that ‘during the seventh to eleventh years of his service’ a constable could ‘twice receive an annual increment of £10 for good conduct, special zeal, general intelligence, general proficiency, or by passing a qualifying examination in education and police matters’. Promotion, too, was made quicker and easier; the service period for qualification was reduced from seven to two years, and some other short cuts to promotion became possible. There was a big stick in the background: no man dismissed for misconduct—including going on strike—was entitled ‘to any pension or gratuity’, and this could mean the loss of a pension of up to £250 a year for a man with thirty years’ service. Pensions, pay rises and promotion prospects gave police better career goals, a greater sense of personal security and more money in their pockets. Nor did the rewards for loyalty stop there. In May 1924 all loyalist police were granted seven days’ extra leave, and in 1925 and 1927 respectively the annual leave for all police was raised to twenty-one days, then twenty-eight days, a great advance on the previous entitlement of seventeen days, and one that brought the force into line with New South Wales.

The government improved police surroundings with a massive increase in spending on police equipment and buildings. A new depot was built on land fronting St Kilda Road, the Russell Street barracks remodelled, the Bourke Street West police station renovated and dozens of other lesser works completed at police stations throughout the state. Table 4 shows the scale and rate of this increased capital expenditure. Given the nexus established by the Monash royal commission between the squalid state of many police buildings and the propensity of men living in them to strike, it is unfortunate that the frugal Lawson ministry did not spend some of this money before the strike.3

TABLE 4

Capital expenditure on buildings and works for police

Financial year |

Amount spent (£) |

% up or down on * strike year |

1918–1919 |

2891 |

–66% |

1919–1920 |

2879 |

–66% |

1920–1921 |

5752 |

–33% |

1921–1922 |

6681 |

–22% |

1922–1923 |

8597 |

*base year |

1923–1924 |

20 997 |

+ 144% |

1924–1925 |

20 109 |

+ 133% |

1925–1926 |

24 565 |

+ 185% |

1926–1927 |

31 637 |

+ 268% |

1927–1928 |

39 292 |

+ 357% |

Victorian Government Expenditure in Division 1 sub-division 2—Police Buildings (includes buildings and works for police, land, furniture, repairs and additions and fencing). (Source: Victorian Parliamentary Papers. Treasurer’s Financial Report for years 1918–1919 to 1927–1928.)

Buildings and manpower were not the only matters to occupy Nicholson in the last months of his career, and after the strike he resumed consideration of three developments that were initiated before October 1923 but temporarily pushed into the background by the strike. They were the use of dogs and wireless in police work, and an expanded role for women police. And that is the order of importance in which Nicholson viewed them. In 1922 the force acquired two ‘fine young liver-and-white pointers’ and during April 1923 they were taken on patrol to test their utility for police work. The trials were a favourite project of Nicholson’s and he was firmly committed to the idea that the dogs would prove a ‘great success’, reduce crime and save ‘police from being maltreated’. During 1924 he obtained information about the subject from a number of overseas sources, including the South African Police, and initiated a breeding programme at the Dandenong Police Stud Depot, using bulldogs, pointers and Airedale terriers. But their handlers lacked expertise: the dogs were not properly trained and were a failure. The scheme gradually faded from existence, but not before an Airedale–bulldog cross named P. C. Bully acquired considerable fame as a night rider with the Wireless Patrol. As a working police dog Bully was a flop, but perched on the running board of a police Lancia travelling at 50 miles an hour he was the meanest motor-car mascot in Melbourne.4

Nicholson’s keenness to give police dogs a trial set him apart from Alfred Sainsbury, who rejected the idea in 1914 as not worth ‘the time, trouble or money’. On another issue both men agreed: women had only a very limited role to play in police work. When women first entered the force in 1917 it was against Sainsbury’s wishes, and although many policemen, including Steward and Gellibrand, were pleased with the work of the women, Nicholson remained unimpressed. In 1922, after five years’ service as ‘police agents’, Victoria’s two policewomen asked if they might be paid equal money for doing equal work. It was a valid plea by women not subject to any entrance standards or training, but doing the same long hours and shifts as the men, and similar duties. The women took their own case to the chief secretary and the chief commissioner, arguing that they had all the usual living expenses to meet, plus special police ‘out of pocket expenses’, and the requirement to ‘maintain dignity’ and be ‘decently dressed’ at a time when ‘women’s clothing had increased in cost by leaps and bounds’. In August 1922 the policewomen were granted a daily plain-clothes allowance of 1s 6d, but this still left their pay at least five shillings a day below that of their male colleagues. Because they were not members of the Police Association that body did not support their claim, but the women did have a friend in John Cain, Labor MLA for Northcote, who aired their case in parliament. The moves by and for women police to improve their lot were accompanied by sustained lobbying from community groups like the National Council of Women, to increase their strength; and the number of policewomen was increased to four by the appointment of Mary Cox in September 1922 and Ellen Cook in September 1923. The movement to give policewomen greater recognition was gaining momentum and was given valuable impetus during the police strike, when the women loyally remained on duty throughout the crisis. After the strike there was talk of recognising the women’s efforts by extending the proposed pay rises and pension scheme to include them, but the moves were stymied by Nicholson. He publicly and privately opposed equal rights for women police and, at the height of discussions in December 1923, he wrote to the under-secretary:

The Wireless Patrol: P. C. Bully on running board and F. W. (‘Pop’) Downie at extreme right

If policewomen were made members of the force, they would be entitled to the pay and privileges of male members, unless special provision to the contrary was arranged. Their degree of usefulness to the government does not, in my opinion, justify their being placed on the same footing as the police, their sex hampering their usefulness.

In a separate press statement Nicholson even went as far as to suggest that if the women were to ‘be entitled to the same status as ordinary members of the force’ he could see ‘no alternative but to dismiss the four women’. A. J. O’Meara has generously assumed that Nicholson adopted this stance in the interests of women, ‘as a bluff to focus attention on the fact that, since they were not sworn in as constables, they could not be eligible for all the privileges to which that rank was entitled’. Yet such a claim is based on Nicholson’s tacit support for women police in a restricted welfare role. The truth is that Nicholson opposed the full entry of women into the force. His opposition to equal rights for policewomen, rather than serving as a ploy to highlight and remedy their plight, actually prolonged it. The conservative government of Harry Lawson accepted Nicholson’s recommendations, and it was not until after the Labor ministry of George Prendergast came to office on 18 July 1924 that Victoria’s four women police were sworn in, on 12 November 1924, and legally vested with the same powers of arrest, pay and pension rights as their male colleagues. O’Meara fails to mention the crucial change of government. The Labor Party had always supported efforts to improve the lot of women police, and when they used their brief spell in government to give legal effect to this policy it was not done with Nicholson’s concurrence.5

Women still had a long way to go. In 1924 there were only four of them among more than eighteen hundred men, and within the force were many sections destined for decades to remain all-male bastions. One of those sections was the newest and most exciting area of police work—the Wireless Patrol.

A powerful touring car slips along decorously in the early morning quiet of Melbourne. Externally it is the property of some eminently respectable suburbanite homewardbound.

Inside it, beside the driver, are a dog and four men, one of whom wears a leather helmet and wireless headgear.

The headgear buzzes … Dot-Dash-Dash-Dot-Dot … ‘Thieves in warehouse, Lygon Street, Carlton’, the operator reads. At a word the driver accelerates, and the rest of the message is taken at 50 miles an hour.

The wireless patrol, which nightly guards thousands of lives and millions of pounds worth of property, is on the job.

That is the style of journalistic eulogies of the Wireless Patrol found in the pages of Melbourne newspapers throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The ‘Patrol’, as it became more colloquially known, was the brainchild of Senior Constable Frederick William ‘Pop’ Downie, who was described in later years by Sir Thomas Blamey as ‘the most intelligent, uneducated man’ he had ever met. The hitherto unknown sight of six burly policemen together in a sleek motor car with a dog and a wireless set enraptured the public and proved a revolutionary turning point in modern policing. Members of the patrol were able to boast that ‘the average time taken to get to the scene of a crime is 4.4 minutes’, and their arrest record was unchallenged by any other police in Australia. Indeed, they were the envy of the international police community, and were the first police in the world to put wireless in a touring car.

Today, police use of sophisticated communications equipment is an essential feature of every force, but in 1920 the mere idea of police wireless was so novel that it attracted wonder, incredulity and sometimes scorn. At that time Downie was serving with the Motor Patrol, which used a Palm car built from Model T Ford parts to patrol at night, checking such places as post offices and railway stations. To receive and give information, this unit would call at police stations each half-hour and telephone Russell Street for news. It was an inefficient means of communication. Around 1921 Downie began working with the idea of providing wireless for police patrol cars, and by November 1922 had developed his concept to the stage where he was able to persuade Nicholson to take part in experimental transmissions. Initially, these experiments were conducted using wireless telephony but it was decided to switch to wireless telegraphy, which involved the use of morse code, and this remained the basis of the police wireless network until April 1940. The force’s first Marconi receiving set was hired from Amalgamated Wireless for £1 a week and fitted to the force’s one Hotchkiss car in May 1923, and this was followed by the purchase of two new Lancia patrol cars later in 1923, and the progressive purchase of a fleet of Daimlers from August 1926. In the space of five years Downie’s Wireless Patrol was a revolutionary reality. From these small beginnings the combined use of motor cars and wireless by police slowly developed, resulting in the removal of constables from suburban beats and their encapsulation in patrol cars. In the period before World War II it was not a problem, it was progress. However, by the 1970s a ‘revolutionary new direction’ in police work was Operation Crime Beat, a scheme to take policemen from motor cars and put them back on the streets to patrol on foot—with portable radios in their pockets. In 1921 when Downie developed his idea after attending the Melbourne Marconi School of Wireless, not even he could have foreseen the impact that his experiments would have on the future of policing.

Dot-Dash-Dot: telegraphist Constable F. W. Canning of the Wireless Patrol

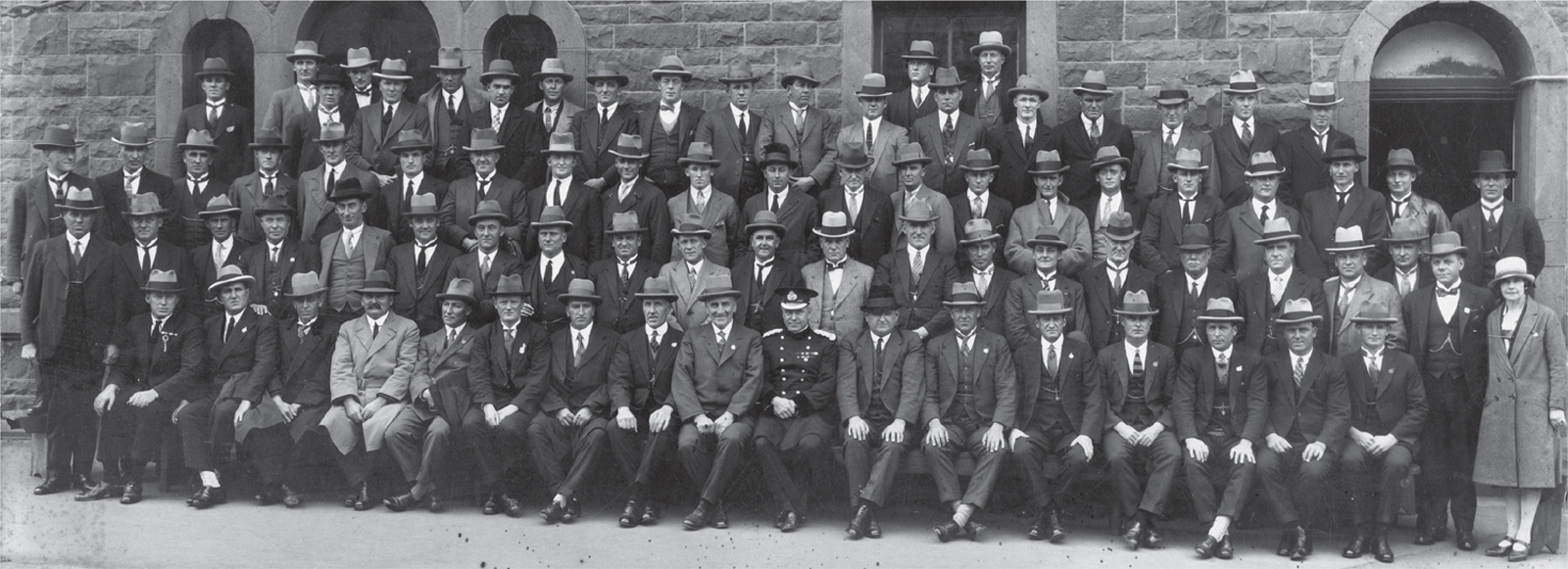

The men behind the Wireless Patrol: Chief Commissioner A. Nicholson, front centre (seated), F. W. (‘Pop’) Downie, extreme right (seated), and Constable F. W. Canning (standing second from right).

What was Nicholson’s role in this? Downie’s son argues that Nicholson was unenthusiastic about the idea and forced Downie to ‘go it alone’, while Nicholson’s son, and the newspapers of the period, credit Nicholson with appreciating the full possibilities of Downie’s vision and with supporting it totally. The real position was more probably as surmised by two of the original wireless telegraphists who worked with Downie: that Nicholson was an ageing and conservative man, approaching retirement, beset by the problems and costs of the police-strike era, and confronted by an inventive senior constable with a bold but expensive plan for police wireless that had never before been tried in the world. In such circumstances, a cautious response on the part of Nicholson would not only have been reasonable and prudent, but would have been in keeping with his character.6 In any event, Nicholson did finally facilitate the introduction and development of the Wireless Patrol, and it served as his swan-song. Before Downie had completed his work, Nicholson became ill and was admitted to hospital in May 1925. He never returned to duty and was succeeded as chief commissioner by Brigadier General Thomas Albert Blamey on 1 September 1925. Post-strike efforts to rebuild the force were largely complete, but on the recommendation of the Monash royal commission, Blamey was offered a salary of £1500 a year, £600 more than that paid to Nicholson, and he was expected to consolidate Nicholson’s work of reconstruction. It was thus that Monash’s former chief of staff ‘embarked on the most tempestuous eleven years of his life’.7

One thing at least is certain about Thomas Blamey: he was complex. Sir John Monash said that Blamey ‘possessed a mind cultured far above the average, widely informed, alert and prehensile. He had an infinite capacity for taking pains … Blamey was a man of inexhaustible industry, and accepted every task with placid readiness. Nothing was ever too much trouble’. Yet David McNicoll is no less right in seeing Blamey as ‘without doubt one of the most controversial generals in history. During his lifetime he was accused of perjury, nepotism, larrikinism, faulty judgement, drunkenness, lechery, deceit and even—by a couple of his more dedicated enemies—cowardice’.8

Blamey, who was to become Australia’s first field marshal, is still heralded as its ‘greatest soldier’ and ‘unrecognised hero’; yet in 1936 his career was seemingly in ruins, when, ‘almost friendless’ and ‘widely vilified’, he was asked to resign from the police force. As chief commissioner, Blamey was a controversial figure, uniquely embodying the reformist generalship of Steward and Gellibrand, the fractious authoritarianism of O’Callaghan and the scandal of Standish. His commissionership spanned eleven stormy years, beginning in the wake of the police strike amid calls for an inquiry into police corruption, and ending during the 1930s, following a royal commission inquiry into the shooting of Superintendent J. O. Brophy. During his police career Blamey survived five changes of government and an unprecedented challenge to his tenure of office, and confronted—some would say precipitated—a series of personal and professional crises that included the notorious ‘badge 80’ affair, a provident-fund controversy, a running feud with the press, the shooting of demonstrators by police, the break-up of the Police Association, and several police inquiries. Some of these troubles were primarily of his own making, and others were largely political in origin, but rarely was Blamey an innocent bystander. He was an outspoken man—politically conservative, with a dislike of the Labor Party—and displayed an intense personal interest in the suppression of communism, working-class radicalism and public protest. His reactionary politics he shared with his predecessors in the office of chief commissioner, but Blamey served for several years under Labor governments. Against a background of economic depression and unemployment, his personality and politics made a difficult task even harder. In the words of John Hetherington, Blamey’s years as chief commissioner were spent ‘on the edge of a volcano’.

Blamey was initially appointed chief commissioner by the conservative Country Party ministry of John Allan, after Sir Harry Chauvel mooted the idea with the chief secretary, Dr Stanley Argyle, during an early-morning stroll in the Botanic Gardens. Blamey’s appointment was well received by the more conservative and propertied elements in the community, who had been so troubled by the police strike and the seeming inability of policemen like Nicholson to ensure the security of their lives and property. He was only forty-one when he arrived at police headquarters to take charge, but he was a graduate of the military staff college at Quetta who had earned high praise from Monash for his war work, and had already in the post-war period held such positions as Director of Military Operations, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, Colonel (General Staff) at the High Commissioner’s Office, London, and Australian representative on the Imperial General Staff. When he swapped his soldier’s sword for the policeman’s baton, Blamey was Second Chief of General Staff and right-hand man to Chauvel, then Inspector General of the Australian Military Forces.9

Chief Commissioner T. A. Blamey

So highly was Blamey regarded in some circles that his appointment as chief commissioner was of itself enough to end moves for an inquiry into alleged police corruption and maladministration. In the months between Nicholson’s hospitalisation and Blamey’s assumption of command numerous allegations of corruption were levelled at members of the force, particularly the Licensing Branch. Mr H. H. Smith, MLC for Melbourne, moved for a select committee ‘to inquire into and report upon the administration of the police department’ because there was ‘no place on earth’ where licensing supervision was ‘so lax’. He added that sly-grog selling and two-up games flourished because certain police had accepted bribes. His allegations received some publicity and support, particularly from people concerned about illegal trading by hotels, so his calls for a public inquiry gathered momentum and prompted the government to demand explanatory reports from senior members of the force. Being then without a permanent chief commissioner, the force lacked its traditional spokesman, but the mere announcement that Blamey was to get the post was enough to undo Smith’s work. Government members conceded to Smith that there was a ‘great deal to deplore in connexion with our police force’, but they urged him to drop his calls for a public inquiry because ‘the right man’ had been selected and the force under Blamey would ‘be squared up and cleaned up’. The pro-Blamey lobby persuaded Smith to declare that he would not embarrass Blamey and to withdraw his call for an inquiry. Instead, he would place his evidence of lax liquor control before the new chief commissioner. There is no suggestion that the government hastily appointed Blamey with the intention of silencing Smith; the allegations were not as important as all that, and Blamey’s name had been connected with the top police post since 1922. The timing of the announcement was fortuitous, even though it was also fortunate for the government that the new chief commissioner was a well-known and respected general, not an ageing and obscure country police superintendent. The aura of Blamey took effect even before he had taken office.

Yet it was foolish to put such trust in Blamey. The new chief commissioner—to whom drinking was an innocent and indispensable element of everyday social life—openly flouted licensing laws, and his presence after hours at fashionable hotels provided fellow illegal drinkers with a guarantee against police raids. It is not known how his predilection for liquor after hours influenced his handling of Smith’s complaints, but it did highlight a grave flaw in his police command. He viewed the police force with a soldier’s eye, and never really understood the unique responsibilities and obligations attaching to his position as the state’s most senior policeman. In matters such as training, supply, personnel management and organisational planning, where his army background could be readily applied to the police, Blamey was a fine leader. Beyond lay many other aspects of police life, and here he ran into trouble. He publicly told implausible lies out of misplaced loyalties, he openly broke licensing laws because he disagreed with them, he smashed the Police Association because it disagreed with him, he disliked and openly haggled with newspapermen, and he never understood the ‘indivisibility of the private and official lives of the man in public office’.10

It was never more evident than during the ‘badge 80’ affair, which broke only weeks after Blamey joined the force and cast a shadow of doubt over his veracity and the force he commanded. On the night of 21 October 1925, three members of the Licensing Branch raided a brothel in Bell Street, Fitzroy, where one of the amorous male visitors produced to them a police badge numbered ‘80’ and announced, ‘That is all right, boys. I am a plain-clothes constable. Here is my badge’. Badge ‘80’ was Blamey’s. It took several weeks, but reports of this encounter gradually filtered along the passages of police stations, into the corridors of parliament and onto the pages of newspapers, fed all the while by anonymous letters to the government, such as this one:

Do you know that the Commissioner of Police was found in a sly grog shop at Fitzroy last month naked and in bed with a naked woman and that the police who found him there are in terror as to what he will do to them. How is the cursed drink to be put down if the head of the police is an adulterer and a drunkard? Good men are needed at the top, pure and honest (Rom. xiii XI–XIV).

The ‘badge 80’ affair was a daunting test of character. With such a spectre as the chief commissioner wearing naught but his badge, the press had a field day, and during debates in parliament it was suggested that Blamey had been framed (though no one suggested by whom or for what purpose), and calls were made for a full public inquiry. Such an inquiry was never held but, at Blamey’s direction, some detectives did conduct an investigation of sorts, the findings of which were inconclusive on all but one point. It was determined, to the satisfaction of Blamey and the government that had appointed him, that Blamey was not the man who produced badge ‘80’ in Mabel Tracey’s house of ill-repute. That man was never identified or located. The three raiding constables attested that Blamey was not the man, Blamey produced an alibi proving evidence of his whereabouts elsewhere at the crucial time, and Tracey agreed that Blamey was not her amorous customer. Beyond this point the police inquiries went nowhere. It was claimed by Blamey that his police badge had been ‘surreptitiously removed’ from his key-ring the day before the Fitzroy raid, and found by him three days later in his letterbox at the Naval and Military Club. Superintendent Daniel Linehan, the senior officer next in line to Blamey, disputed this story and claimed that he saw the badge on Blamey’s desk only seven hours before the Bell Street raid. Linehan’s candour caused considerable embarrassment to Blamey and the government, and prompted the chief secretary, Argyle, to brand Linehan as ‘disloyal’. However, some weeks later, Linehan reached the pension age and retired from the force, whereupon his statement was conveniently forgotten.

Many years later, credence was given to Linehan’s version by John Hetherington who, in his biography of Blamey, claims that Blamey privately admitted to making up the ‘surreptitious removal’ story. Blamey allegedly confessed that he gave his key-ring and badge to a visiting friend from Sydney on the night of 21 October 1925, but would not tell the truth when the furore finally broke because he did not want to implicate his old army colleague, who ‘was married and the father of three children’. If one accepts Hetherington’s account, and it is more plausible than the inconclusive police report released publicly at the time, then one accepts that Blamey lied and embroiled the force in a public scandal, out of a quixotic sense of personal loyalty to an old army mate. Enduring personal loyalty can be an admirable trait, but a man of Blamey’s intelligence should perhaps have appreciated that the office of chief commissioner, by its very nature, at times demanded a degree of public accountability and personal integrity transcending even that ordinarily expected of a general.11

Yet there were great strengths in Blamey. Like Steward and Gellibrand, he could motivate other men. He was frightened of neither change nor challenge, and he quickly applied his many ideas and talents towards improving the force. He gave unqualified support and encouragement to Downie and the Wireless Patrol team, which developed into a key branch of the force. Some years later he and Downie combined to create an information section, for the systematic collection of criminal records and modus operandi analysis. Without reservation Blamey supported the place of women in police work, and he was responsible for increasing their number and expanding their role. He sent two officers to Europe and North America to study the latest developments in criminal investigation and traffic policing; formed a bicycle patrol section for special anti-crime duties; reorganised the Criminal Investigation and Plain Clothes branches; and established a traffic control group, of sixty constables, equipped with thirty motorcycle–sidecar outfits. The formation of a statistics section, the greater utilisation of fingerprints and criminal photographs and a police mapping programme were all matters to which Blamey devoted his seemingly indefatigable energy. He pursued all these projects along with the routine running of the force, and during his first five years in office took a total of only six days’ leave.

In his approach to police administration Blamey had much in common with Steward, and in one particular area their combined efforts stand as a vital contribution to the force they helped to shape. Both men had an unwavering commitment to the need for police education. Steward began police training; it waned under Gellibrand and Nicholson; Blamey revived it, expanded it and set it on a course from which it has never deviated. Blamey, a former schoolteacher and a product of military discipline, extended the period of basic police training from thirty-five days to three months, and expanded the curriculum to include ‘lectures on sex hygiene, the way to live, hints on general behaviour, attitude towards the public, etc.’, as well as ‘instruction in general education including arithmetic, English, geography, civics, grammar, etc.’ He acknowledged that most police recruits were ‘young working men’ who were ‘not mentally fitted’ for an exclusive diet of law lectures, so he determined that one-third of all recruit training classes would be devoted to ‘general educational subjects’, and ‘a highly qualified teacher’ from the Education Department was appointed for the purpose. A qualified teacher from outside the force was unprecedented, and his presence exposed police recruits to the wider world of human knowledge existing outside the pages of their law books, and was vital in helping them understand the institutions and the people they would be expected to deal with.

In addition to this recast basic training, new regulations effective from 1 August 1926 required recruits graduating from the depot to enter a twelve-month probationary period, at the end of which they sat a retention examination; unless candidates obtained a 60 per cent pass they were not entitled to any increase in pay. The scheme was designed to encourage further study by working police, in their own time, and to facilitate it Blamey scheduled a series of free day and evening instruction classes, covering all the subjects tested at both the retention examination and the promotion examinations for higher ranks. Blamey later claimed that the result was an educational standard ‘considerably higher than it ever was before’, and an obvious ‘improvement in efficiency’. His mild boast was quite justified; some measure of his success is found in the fact that his basic concept of broadened and in-service police education has survived him and is the corner-stone of modern police training.

Blamey also acquired a deserved reputation as an irritable autocrat who ‘enforced his will relentlessly’, but his empathy with the welfare needs of the force was greater than that of his predecessors, save perhaps Steward and Gellibrand. In many things touching upon the morale and well-being of the force Blamey had a clear notion of sharing and fairness to all. An element of ‘equal opportunity’ was introduced into the procedures for filling vacancies in the CIB and Plain Clothes Branch, and into the general system of awarding commendations. Previously the plum jobs and the commendations were something of a ‘closed shop’, and many qualified members missed out because they had the ‘wrong’ contacts or did not have the ‘right’ boss. Blamey changed this for the general good of all members, with beneficial results in morale and efficiency. He also introduced a new grade of first constable, which ranked between those of constable and senior constable, and afforded constables with less than ten years’ service the chance to gain promotion and increased pay. It was taking constables up to twenty-six years to gain the rank of senior constable, and Blamey’s new intermediate grade sustained ambition and morale by providing a chance to earn increased status, responsibility and pay. Blamey also saw the police hospital as a place for treatment and caring rather than as a hospice for suspected malingerers, and he upgraded its facilities and staffing to include ‘three trained nurses with a matron in charge’, who took over from the one male dispenser who previously had sole care of patients. Blamey was also very keen on the idea of a police holiday home by the sea where members and their families could rest and recuperate, and he went so far as to purchase the necessary land at Mornington. Here Blamey was ahead of his time, and it was not until many years after he left the force that his concept was given effect.12

Healthy bodies, healthy minds and healthy wallets might well have been Blamey’s recipe for the making of a contented force: he devoted considerable energy towards these things. He encouraged the use of new gymnasiums at the Police Depot and the Russell Street police station, so that men could ‘keep themselves fit’, and he established a police institute ‘to allow members of the force to buy good articles at low prices’. Limited credit was allowed to police shopping at the institute and all profits were ‘devoted to police welfare objects’. In conjunction with the Police Institute, Blamey started a police provident fund to assist ‘policemen who were financially embarrassed owing to illness or other ill-fortune’ and to ‘prevent young constables from getting into the hands of moneylenders’. Blamey firmly believed that police were underpaid, and he was known to lend those in financial trouble up to £300 from his own pocket, repayable at the rate of five shillings a week, interest free. The provident fund scheme—modelled on similar funds in London—was an extension of this belief, and was a positive attempt to alleviate the financial difficulties of many policemen. After 1925 the post-strike improvement in police working conditions had lost momentum, and the pay of junior constables fell behind the basic wage. Blamey sought in particular to ease the plight of these men, without simply adding his voice to the never-ending and seemingly ineffective chorus asking for increased wages. The provident fund was started in June 1927 with a donation of £100 from the Commonwealth Bank, and was quickly added to when, in July, the philanthropic J. Alston Wallace made a gift of £1000 in recognition ‘of the hourly danger to which members of the police force are exposed in their work of protecting the lives and property of the citizens of this state’.

Wallace’s gesture, like that of Blamey’s in establishing the fund, was well intentioned, but their combined actions prompted a public outcry and drew severe criticism from both the press and the government. Both men were forced to publicly defend their actions, and for Wallace this meant disclosing his identity and motives, after initially making the gift anonymously. Considerable public pressure was exerted on Blamey to return the money, lest a ‘dangerous precedent’ be set of police accepting ‘gifts of dubious propriety’, which could ‘hamper them in the execution of their duties’. Blamey, however, proved that he was a man to be reckoned with. Much to the annoyance and embarrassment of Ned Hogan’s newly elected Labor government—sections of which labelled the gift as ‘practically bribery’—Blamey kept the money and the provident fund, and closed the subject by reporting that he was ‘unable to return the money’ as he had been legally advised ‘that the contribution became the property of every member of the force directly it was accepted’.

Blamey’s establishment of a police institute and provident fund were not uncharacteristic ventures into socialist co-operativeness but were typical examples of his paternalistic leadership style. He exercised firm control over both ventures. There were no committees, no elected office-bearers and no audits, the balance of accounts was kept secret, and disbursements were dependent upon the personal good will of Blamey. Incidents like this rankled with the Labor Party, annoyed the press, and kept Blamey on the edge of a volcano. In doing so he won the wholehearted support of many policemen and a common sentiment among them was that ‘all Blamey was ever guilty of was sticking to his men’.13

Not all Blamey’s troubles ended as resolutely and smugly as the provident fund controversy, nor were the issues in conflict always as straightforward. The most controversial administrative action of his police command involved the virtual destruction of the original Police Association, and the substitution of a puppet organisation, over which he retained control. Blamey’s attitude was that of a military man: there was no room for a ‘trade union’ in a disciplined police force. Almost from the time he assumed office, he embarked on a course destined to end in a showdown between himself and the association. For Blamey it was an immutable question of principle, and he was unmoved by the association’s claims that it had existed since 1917 as a properly constituted body, had not taken part in the police strike, and had over the years made a worthwhile contribution to the well-being of the force.

Before Blamey’s appointment the association had worked with Sainsbury, Steward, Gellibrand and Nicholson, and, although disagreements often arose, there was never any serious conflict of wills. Blamey had been in office for less than eight weeks when, on 26 October 1925, he wrote to the Crown solicitor seeking an opinion about the legality of certain of the association’s activities, including determination of the legal status of its secretary, who was ‘not a member of the police force’. The Crown solicitor decided in favour of the association and no prosecutions were made, but it was an early sign of things to come nearly three years later.

During August 1928 Blamey held the inaugural Victoria Police Conference at the Police Depot, where twenty-nine elected delegates, who represented all grades and branches of the force, discussed 120 agenda items ‘of importance to the force’, including pensions, pay, travelling and uniform allowances, accommodation, long-service leave, hours of duty, ‘bedding for troop horses’ and—a clear indication of Blamey’s personal influence on the proceedings—a recommendation ‘for the removal of the press representatives’ from the press room at Russell Street. One delegate represented the Police Association, but his was a token presence for Blamey had effectively established his own system: his conference duplicated a number of the association’s activities and gave him the basic structure of a forum that he later used to supplant the association.

Blamey’s conference was modelled on the English Police Federation instituted in 1919, after the English police strikes, ‘as part of the official campaign to destroy an independent union movement, by providing some measure of the right to confer’. The federation was designed to ‘act as a means of containing police dissatisfaction’, by allowing ‘elected representatives of each rank’ to ‘consider and bring to the notice of police authorities … all matters affecting their welfare and efficiency other than questions of discipline and promotion affecting individuals’. Blamey adopted the same sort of forum, even down to incorporating the same words into its charter, and providing for a disproportionately high level of representation by the senior ranks, to minimise the influence of constables, ‘the most numerous and militant rank’. Even so, the conference was a valuable arena for debate, encompassing a greater range of delegates and discussion points than did the association. Blamey’s system provided a forum for the previously unheard opinions of the policewomen (who were allowed a delegate of their own) and policemen who were not members of the Police Association. Initially only an annual event, the conference system still had serious implications for the future of the Police Association, so it troubled the Labor government, which first read of Blamey’s scheme in The Age. In his inimitable fashion Blamey again affronted the Labor Party by setting out to undermine a union of workers without telling his political masters.14

Shortly after Blamey’s first conference, the conservative McPherson ministry was returned to office and, in a favourable political climate, his conferences were no longer a problem. With the support of McPherson, Blamey then introduced new promotion regulations that placed emphasis on examination results and ability, rather than seniority. It was a sound idea in principle and had been spoken of by Blamey’s predecessors, but he was the first commissioner bold enough to try to shift the emphasis in promotion from seniority to merit. Among often reactionary policemen, Blamey’s scheme was widely viewed with disdain; it threatened not only the status quo but also the prospects of policemen of mediocre ability. Merit is hard to define, and Blamey’s plans were not fool-proof, but he had two good reasons for wanting to change a tradition dear to the hearts of many policemen. First, the many hundreds of men who joined immediately after the police strike were permanently disadvantaged by their lack of seniority. Secondly, Blamey wanted ability promoted. It was his view that:

The police force of Victoria today is suffering very greatly in its efficiency … It can never become a really efficient force until the most able men are given opportunity to attain the highest positions without having to wait for the passing on of men of poorer abilities. Since the rewards in the higher ranks are considerable, the state should have the right to the full value of the services of the men of greater ability in the higher ranks. The seniority system of promotion is the worst factor in the police system of this state.

Blamey had succinctly stated a strong position: a police-promotion system should give value to the public who pay for it, not sinecures to ageing and indifferent policemen. Many policemen regarded Blamey’s view as heresy, and it has been debated perennially.

The Police Association was quick to oppose his plans, and the subject rapidly escalated into a heated political issue. As the debates warmed up, the parties became increasingly polarised. The association and its supporters argued that ‘the regulations had created discontent, uncertainty, unrest, and suspicion throughout the force, and … were undermining the spirit of comradeship and esprit de corps’, whereas ‘long and faithful service was entitled to rewards’. Blamey, his supporters and even the newspapers reasserted that there ‘should be no obstacle to prevent the progress of the brilliant man, and no mechanical advancement for the mediocrity whose only distinction is length of service … Those who insist that promotion should be governed exclusively, or even chiefly, by seniority put themselves in the position of defending entrenched incompetence against the pressing claims of ability’.

The new regulations were first given legal effect by the McPherson ministry on 1 July 1929 but, before they had any real impact, the association succeeded in making them an issue during the November 1929 state elections. The association firmly believed that a change of government was its ‘only hope’ of having the new promotion scheme modified or abandoned, and during the election campaign it lobbied every candidate for parliament and urged all its members to vote for ‘candidates who have signified their intention of assisting us … make sure that all your relatives and friends vote as you intend to on polling day’. This stand came close to being an open endorsement of the Labor Party, and Blamey was so incensed at the association’s defiant and partisan display that he again sought the advice of the Crown solicitor as to the legality of the association and its conduct.

Before Blamey had time to take any further action, and to the glee of the association, the Labor Party won the election and the Hogan ministry again took office. The tables were turned on Blamey. The association’s honorary solicitor, Mr W. Slater, MLA, was sworn as attorney-general in the new ministry; the Hogan government agreed to defer and review Blamey’s promotion plans; and applications were invited for the position of chief commissioner. Blamey was told he could reapply for the job if he so desired, but he was—and remains—the only chief commissioner to have his position advertised, against his wishes and while he was still serving under contract. Blamey was paying for his alienation of the Labor Party.

The uncertainty of tenure attaching to his position diverted Blamey’s attention away from the promotion regulations and the behaviour of the association—for a time. A different man might have resigned, but Blamey successfully devoted his considerable energies to securing reappointment and, after months of haggling, he emerged battered but victorious. The Labor government, having caused Blamey undoubted anguish of an unprecedented kind, reappointed him on a limited three-year contract and on a Depression salary drastically cut by one-third, from £1500 to £1000 a year.

A Plain Clothes Branch muster on the occasion of the visit of the Duke and Duchess of York in 1927: Chief Commissioner Blamey in uniform; Policewoman Mary Katherine Cox, standing extreme right, and J. R. Birch, standing extreme left, second row. Birch later founded the Special Branch

Having secured his base again, Blamey sought full and swift retribution on the association that had so openly defied him. His new contract began on 1 September 1930; on 4 September he declared the association an ‘illegally constituted body’ and directed all members of the police force ‘to dissociate themselves from it’. His action was supported in a petition organised by his personal staff and signed by over three hundred policemen who, although constituting less than 15 per cent of the force, comprised its most senior members, and was backed by a legal opinion from the Crown solicitor that the existence of the association ‘in its present form’ contravened the Police Regulation Act. During October 1930 Blamey used his third Victoria Police Conference to form a new ‘legal’ police association, modelled closely on the lines of the English Police Federation. This association, with teeth drawn, was firmly under his influence and gave him ‘complete control of all the members in their sporting and social undertakings’. Some vestiges of the original association remained while the secretary and executive fought for its survival, and for a time the two associations, differentiated simply as the ‘old’ and the ‘new’, existed in spite of each other. Blamey, however, was also quick to end the duplication. Victor G. Price, the civilian secretary of the old association, was charged and convicted with ‘inciting members of the force to commit breaches of discipline’ and sentenced to one month in gaol. On appeal to the Court of General Sessions his sentence was varied to a fine of £10 but he was refused leave to appeal to the High Court. The police office-bearers of the old association were reprimanded and transferred from Melbourne to distant rural centres—known colloquially as Siberia—at Mildura, Tallangatta, Portland, Wangaratta and Horsham. By the end of July 1931 Blamey had accomplished the total destruction of the original association and supplanted it with a tame-cat organisation of his own making. Eventually, the new association returned to its ‘old’ mould and became a genuine union of employees, but that was not for many years, long after the iron-fisted general had left the force.15

And what of the new promotion scheme that sparked this affray? It disintegrated like the old Police Association. Blamey tried to develop his idea, but not even the new association and a return to conservative government could save it from the passive resistance of a force committed to promotion based upon seniority. The ructions between Blamey and sections of his force were conflicts that at times seriously upset the well-being of the department. However, for many people outside the force they were little more than internal rumblings, although they were symptomatic of more serious and violent activity directed by Blamey against trade unionists, suspected communists and others who dared engage in public protest. During Blamey’s commissionership police were involved in a series of conflicts with demonstrators, including one notoriously bloody, large-scale clash, and numerous complaints were made about alleged violence and harassing tactics used by policemen against the unemployed and unionists. The Depression years were tough, lean years for many thousands of Victorians—including the police, who voluntarily underwent pay cuts—and many people gave vent to frustration in public protests and violence. It was an unsurprising phenomenon in an age when many doubted that the meek would inherit food, clothing and shelter, let alone the earth.

Blamey’s task was not easy, but he did not make it easier. In contrast to Chomley’s discreet policy in the 1890s depression, Blamey was quick to side with capital against labour and quick to crush public protest. He issued a direction that any unemployed people marching through Melbourne and causing a breach of the peace were to be ‘hit over the head’ with batons, and in a personal battle waged against suspected communists he formed the genesis of a special branch and regularly petitioned the government for special powers to ‘deal with communists’. In his loathing of working-class radicalism and communism Blamey was far from alone, but his repressive zeal was extreme. It prompted an officer of the Investigation Branch of the federal attorney-general’s department to complain that Blamey ‘more than any other’ was responsible ‘for giving the public something to talk about and exaggerate to hysteria and nonsense’.

Blamey’s campaign seemingly had as many supporters as detractors, being backed by a large body of public opinion and the conservatives in parliament. However, the particularly violent clash between police and strikers had even his most loyal backers groping for explanations to justify the shooting by policemen of four unarmed demonstrators. On 2 November 1928 a group of twenty-three armed police, under the command of Sub-Inspector Mossop, were detailed for duty at Prince’s Pier ‘to protect’ strike-breaking volunteers from possible assault and harassment by striking members of the Port Phillip Stevedores’ Association. The protection of strike-breakers was a routine police activity, but on this day a large group of strikers reportedly stormed the pier and the police line. In the mêlée that followed, the police fired their revolvers into the surging mob, wounding four unarmed stevedores. Three of them received only minor wounds but one, Allan Whittaker, was hospitalised with a serious gunshot wound to the face and died of his wound on 26 January 1929. Whittaker was an AIF veteran who had been shot and seriously wounded on 25 April 1915 during the Gallipoli landing, and his death at the hands of police on the Melbourne waterfront struck a note of cruel irony with those critical of the police actions. The storming strikers stoned the police with blue metal, seriously injuring two constables, one of whom ‘fell unconscious, and was kicked as he lay on the pier’.

Chief Commissioner T. A. Blamey addressing a parade at Russell Street police station

Blamey defended the shootings as being an act of last resort, and added that it ‘would have been a tragedy to have allowed the mob to gain possession of the pier’. The labour movement greeted Blamey’s statements with anger and derision. Many people harked back to the ‘Tom Price incident’ of 1890, and the waterfront was alive with the story that ‘Inspector Mossop had not adopted the command of Tom Price, “Fire low and lay them out”. He had told his men to fire high and be sure to kill’.

In 1873, when Standish’s men at Clunes drew their guns to protect Chinese strike-breakers from protesters, Standish was castigated by the government for intervening in ‘a dispute between employer and employed’. In 1928 there was no such censure for Blamey. No policemen or strikers were charged over the incident, and the conservative Argyle ministry resisted calls for a public inquiry into the shootings on the grounds that they were justified, and pointed out that Mossop’s men were heavily outnumbered by hundreds of angry, burly stevedores. Many people acknowledged that this last point had some relevance, but in the absence of a full public disclosure of the facts some questions remained unanswered. Why did the police not retreat instead of shooting? Why did the police have guns at the scene of a public demonstration? Why were there so few policemen on the pier, with no reinforcements in reserve, to contain such a situation without using firearms?

Blamey and the government remained mute in a stand that did little to help the image of the police or placate a seething waterfront population. Hetherington says that although Blamey was ‘authoritarian’, he knew that his force was ‘not at war with the citizens’; and yet Hetherington adds that in the ‘economic depression of the early 1930s the police had to maintain public order in Victoria when thousands of men who wanted work and could not get it were clamouring for the right to earn their daily bread. The problem of how to keep the peace without using violence now and then would have baffled Solomon’. There is truth in this defence of Blamey, but it could be said with equal validity that Blamey’s style of dealing with public protest was confrontationist, readily violent, and generally ruthless.16

In 1932 serious allegations of violence were again levelled at Blamey’s men after they used batons to stop a peaceful protest of 150 unemployed workers marching along Flinders Street. This time the Labor Hogan ministry appointed Mr A. A. Kelley, PM, as a one-man board of inquiry to investigate the incident. Kelley eventually exonerated the police and found—according to the newspapers (copies of the report itself seem not to exist)—that they were ‘justified in using force’. During the investigation Blamey defended the actions of his men and advised Kelley that ‘unchecked demonstrations’ were a ‘real danger’, and that to combat them he had formed a special section to ‘watch communist propaganda, and to attend to all matters, such as evictions, which tend to mass lawlessness’. Sergeant J. R. Birch was the head of this special section, and he told Kelley that the protest march was stopped because he had ‘heard from a reliable source’ that the marchers ‘proposed to demonstrate at Parliament House’. Not surprisingly, Kelley’s finding and the evidence of Blamey and Birch alarmed many working-class people, and the Central Unemployment Committee denounced the outcome as ‘white-washing’. The Hogan Government too was concerned at the train of events, and paid the legal expenses of the unemployed men involved, but before Hogan could take the matter any further his government was voted from office.17

Much to the relief of Blamey, May 1932 saw a return to office of a conservative ministry under Argyle, the friend who had appointed Blamey in 1925 and who now restored his salary to its original level and gave him security of tenure for life. Yet the volcano was not extinct. During 1933 allegations of corruption continued to be levelled at Blamey and some other members of the force, primarily in connection with the recovery and restoration of stolen motor cars, and Kelley was again appointed to investigate. The inquiry generated some bad publicity for the force but, after sitting publicly for twenty-seven days and examining 146 witnesses, Kelley exonerated all the police, including Blamey, and the matter ended.18

There is no evidence of impropriety on Kelley’s part, but he proved a good friend to Blamey when it counted most. In 1930 it was he who gaoled Price and finally broke the spirit of the old Police Association; in 1932 it was he who condoned the use of police violence to stop a peaceful protest march; and in 1933 it was he who dismissed thirty corruption allegations levelled against members of the force. The 1932 and 1933 Kelley inquiries have a relatively insignificant place in Victorian police history. All the police involved were exonerated and the matters were quickly forgotten. No published work on the force has even mentioned them.

During Blamey’s time the exoneration of policemen accused of wrong-doing was not unusual. It is also not unusual to find that the relevant reports and other important documents are missing. Large amounts of archival material from Blamey’s commissionership cannot be found; all the chief commissioner’s correspondence for the period 1921–34 is missing and registered by the force as ‘destroyed’. The chief secretary’s inward correspondence for the years 1933–35 is missing, as are the premier’s secret papers for the years 1929–37. Included among these papers are most of the documents relevant to Blamey’s anti-communist activities, the formation and work of his ‘special section’ and complaint files about alleged police corruption, violence and harassment during the Depression years. The destruction of such a large volume of police papers is unique to the Blamey era.

A key link in the chain of troubles leading to Blamey’s ultimate downfall was his bitter and constant battles with the press. He shared the opinion held by many regular army officers that ‘newspapers were irresponsible, mischievous and often ill-informed’, and he believed that they ‘ought to be regimented’. From the beginning of his police command Blamey took steps to thwart what many other people accepted as the legitimate activities of newspapermen. He stopped policemen giving information to journalists, he delayed and vetted crime reports that were released to the press, he had surveillance police follow reporters to check on their activities, and he closed the press room at police headquarters to all police roundsmen and prohibited their entry beyond the public inquiry counter. Blamey’s initial idea was the sound one of trying to bring some measure of control into the relationships between police and journalists, to stop policemen leaking information to favoured journalists—usually for payment—and to stop the lionisation of individual detectives by friendly journalists. Regulation of such practices has since been adopted as an important part of the relations between police and press, but Blamey went beyond reasonable control and embarked on an individual crusade against newspapermen, for their ‘insufferable disposition’ to intrude upon ‘strictly personal affairs’. Apart from the Star, which he sued for libel, Blamey did not single out any particular journalist or paper for his wrath, but labelled them collectively as the ‘Modern Moloch’. For their part, the newspapers responded with a range of journalistic retorts, including one prophetic line in an Argus editorial, satirically headed ‘Atten-Shon!’, that criticised Blamey’s position as that of a man in ‘the Indian summer of a fading autocracy’.

Blamey’s attitude has since been described as ‘resentment of press criticism carried to an extreme’, and although a number of his close friends warned him that his stand was unwise, he dismissed their misgivings with a gruff, ‘I’m not afraid of the press’. It was unfortunate for him that he was not. He had whipped the Police Association, the Labor Party, the communists, and anyone else who dared defy him, but in his battle with the newspapers was himself about to be whipped and pilloried by a united press, keen to see him squirm. Although he could not guess it in 1935—the year he was knighted—Blamey had less than twelve months to serve as chief commissioner and was soon to stand vilified and shamed at the hands of the press: living proof of Napoleon Bonaparte’s epigram that ‘Four hostile newspapers are more formidable than a thousand bayonets’.

Or, to revert to another metaphor, Blamey’s volcano was about to erupt.19

Before it did however, in what was probably Blamey’s last noteworthy action as chief commissioner that was not shrouded in controversy, he was instrumental in creating a special police unit to guard the Shrine of Remembrance in Kings Domain on St Kilda Road, Melbourne.

Opened on 11 November 1934 by Prince Henry, the Duke of Gloucester, before a crowd of 300 000 people, the imposing Shrine of Remembrance was built between July 1928 and November 1934, in remembrance of the 114 000 men and women of Victoria who served and those who died in the Great War of 1914–1918: 89 100 of them served overseas and 19 000 did not return.

Despite its great symbolic significance to the people of Victoria, from the time of its construction and opening, a number of acts of petty vandalism occurred in the precincts of the shrine, prompting the premier, Sir Stanley Argyle, to propose that military guards be employed to provide permanent guard duty at the shrine. Chief Commissioner Blamey was first approached by the premier in February 1933 to provide a police guard for the shrine ‘until the question of safeguarding it had been permanently settled’, and he initially detailed three constables to stand guard duty at the shrine from 17 February 1933.

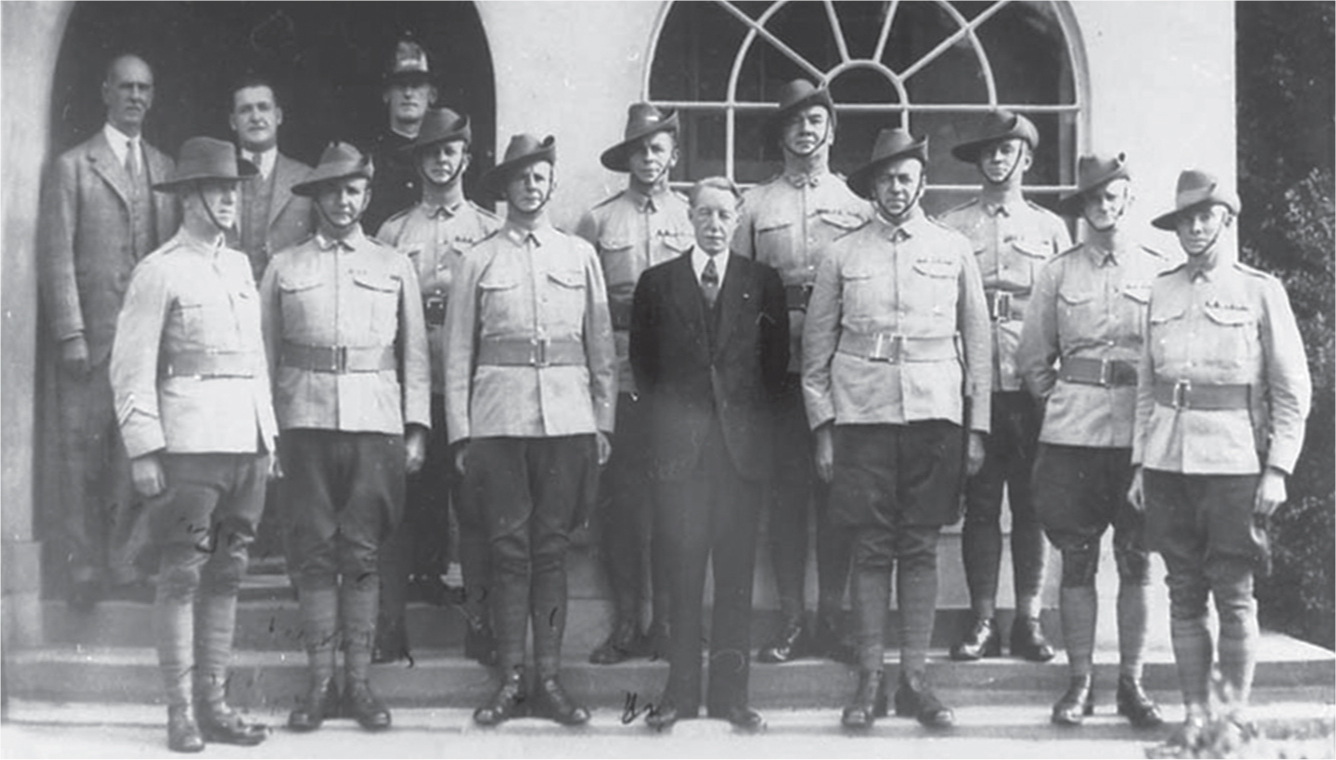

After some deliberation between Argyle, Blamey and Defence Department officials, it was resolved that the Victoria Police would provide a permanent Shrine Guard Unit, staffed where possible by highly decorated ex-servicemen from World War I. Because there were insufficient men with the appropriate experience and military decorations, the Police Regulations were amended to enable the recruitment of older men specifically for shrine guard duty. More than two hundred and fifty men applied for the inaugural intake, from which Blamey personally selected fourteen highly decorated war veterans. These men were appointed to the force on 8 April 1935 and on completion of basic police training they commenced duty at the shrine on 21 August 1935. Among this first group of guardsmen the highest decorated officer was Lieutenant George Mawby Ingram, VC, MM, formerly a carpenter, whose wartime exploits included an action when his platoon ‘was held up by a strong point, he, without hesitation, dashed out and rushed the point at the head of his men, capturing nine machine guns and killing 42 enemy after stubborn resistance’. His status among the shrine guards was such that Ingram was the unofficial leader of the guardsmen, and he was the first of them to perform guard duty at 7 a.m. on 21 August 1935.

The Shrine Guard formed in Victoria is unique in the history of Australian policing, and quite possibly in the English-speaking world, and a prime reason for this is the fact that the guard was a permanent police unit, detailed to provide security and ceremonial duties at a war memorial, dressed in a military-style khaki uniform. Reminiscent of the AIF Light Horse infantry uniform, the first guardsmen were attired in a slouch hat, tan boots and khaki puttees, breeches and tunic, with accoutrements that included a Lee-Enfield .303 rifle. A Sam Browne belt and the distinctive emu plume followed much later.

For Blamey it was a merging of two important phases in his career, but his time as chief commissioner ended in relative disgrace and it was not until another world war that he salvaged his reputation and again made his mark as a soldier.

Amid the controversy that shrouded Blamey at this time, one ray of light was the formation of the Victoria Police Highland Pipe Band, which with Blamey’s support held its inaugural meeting at Russell Street Police Headquarters on 26 February 1936. Instigated by First Constable Jack McKerral, who presented the idea to Blamey, McKerral was the band’s first pipe major and was regarded as its ‘founding father’.

The stated objectives of the band were ‘to help charity [its main purpose]; to play in competitions; to foster Scottish sentiment’ and ‘to give charity concerts and to play at charity carnivals in city and country’. Comprised of eleven members, its initial task, with Blamey as inaugural president, was fundraising to purchase uniforms and instruments, a task that was greatly alleviated by the philanthropy of Mr J. Alston Wallace and Melbourne businessman Mr William Edward McPherson, the former donating £42 to purchase two uniforms and the latter donating £150 to also help with the cost of uniforms. In recognition of this ‘splendid help’ the band selected the red Clan Macpherson tartan for their uniforms.

Members were expected to own their own bagpipes, but drums were supplied. In 1937, equipped with uniforms and instruments, the band was relocated to the St Kilda Road Police Depot and the chief commissioner granted band members four hours’ time off for practice and parades. The first official public appearance of the band in full uniform was at the Coronation March at Olympic Park, Melbourne, on 16 May 1937.

From 1936 until 1988 pipe band members were largely drawn from the ranks of interested and dedicated operational police, who performed with the band on a part-time basis. In 1988 professional musicians were appointed to the force, among them being Inspector Nat Russell, who was recruited as pipe major from the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Under his tutelage the band was rated in the top five pipe bands in the world, defeating in international competition the then current world champions, the Strathclyde Police, as well as the notable Royal Scots Dragoon Guards and the Scots Guards.

Over time the band established itself as an emblematic and successful unit of the force, performing at the Edinburgh Military Tattoo and the Glasgow World Pipe Band Championships, together with numerous competition and charity performances throughout Victoria. Chief Commissioner Neil Comrie described ‘the stirring music of the internationally acclaimed Pipe Band’ as ‘an integral part of the Force strategy to establish positive contact with people of all ages and cultural backgrounds’. In 2014, when the other police bands were purged as a cost-saving measure, the pipe band alone was spared, giving it a continuous existence from 1936 to now.