Regency, Victorian and Edwardian Houses

1800–1914

1800–1914

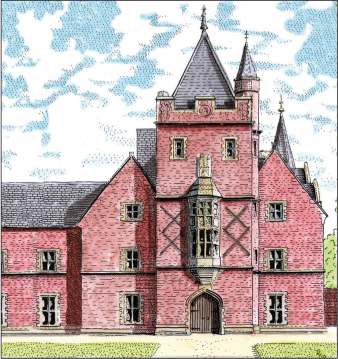

FIG 5.1: CAPESTHORNE HALL, CHESHIRE: At first glance the brick exterior with ogee-shaped caps upon square towers, Dutch gables, and mullioned windows looks like a Jacobean mansion. It is, in fact, a house of 1719 which was rebuilt in 1837 by Edward Blore in a pseudo Jacobean style. Often it is only on close inspection of details like brickwork and windows that these Victorian imitations can be told apart from the originals.

The French Revolution and the subsequent war with France heralded in a period of change. In reaction to the threat from Napoleon, England became severed from Europe and became fiercely patriotic, with a number of country houses built like castles. Enlightened thoughts and sensibilities were quickly replaced by hard commercial facts and industrial ingenuity, to which even the old landed families had succumbed by the 1830s. In addition to the income from agricultural rents which had supported the needs of their predecessors could now be added profits from mines, mills, factories (these often built on their country estates), railways, canals, docks and shipping, investments in stocks and shares, and rent from urban developments. Despite the wealth they amassed, it became increasingly easy to lose it all as huge sums were spent on a daughter’s dowry, running election campaigns, maintaining a hunt, gambling (especially horse racing), entertaining shooting parties and on increasingly grand houses to accommodate this busy social life. Although most of the landed gentry protected their family estates and avoided splitting them between siblings, those who did get into financial difficulty could find gentlemen who aspired to join the aristocracy and so were eager to snap up the property or were willing to marry into the family so that they could rise to the top rank in society.

By the middle of the 19th century the image of the aristocrat was changing. Revolution throughout Europe in the first half of the century had awoken them to the need to take more of the populace under their wing in order to hang onto power and hence their fortunes. They were the cultural leaders of their day and passed their moral codes down to an aspiring middle-class especially through public schools. The ideal gentleman would be a devout Christian and a good landlord, could be a supporter of the arts and of improvements in health and education, but above all would be a faithful husband and family man.

FIG 5.2: BUCKINGHAM PALACE, LONDON: One of the great monuments of the patriotic Regency period dating from 1825-1830. It was, in fact, a rebuilding of the existing Buckingham House by John Nash for George IV, whose notoriety for extravagance was well founded and the architect’s reputation was tarnished by the expenditure lavished on this project.

In reality, many had lost interest in industry and commerce with which their fathers had made their fortunes and instead entered political service. They were more likely to be seen enjoying themselves, hunting, shooting, smoking and playing billiards. No longer did they collect Classical artefacts. Instead, the 19th-century gentleman would fill his rooms with antique furniture, family paintings, Persian rugs and house plants, while exotic trees from around the world adorned his garden. He could also succumb to the new national obsession with history, as less was being written about innovation and more about the past, especially the perceived highly religious and moral Middle Ages. The search for a national identity had fused in an isolationist, mystical world of valiant knights and worthy craftsmen which was probably as much a reaction against machines and a fear of the new than a quest for the origins of English democracy. The Victorians had found merry old England on their doorstep and an empire that was the envy of all other nations. Now at home they transferred the architecture from a favourite period or fashionable country onto their country houses.

FIG 5.3: HIGHCLERE CASTLE, HAMPSHIRE: This backdrop for TV’s Downton Abbey was designed by Charles Barry shortly after he had completed plans for the new Houses of Parliament in the late 1830s. Unlike that Gothic-inspired piece, Highclere echoes the Renaissance style of the late 16th century (see Fig 2.3) with its castle form decorated with Italianate details and strapwork.

The Style of Houses

Until now, country houses have fitted into fairly neat periodic groupings, with the odd whim of an owner an exception and not a rule. However, from the turn of the 19th century, architects found it acceptable to pluck details from a wider variety of sources which in some cases was just a few exotic or historic details that quickly developed into the complete structure. There was also a growing appreciation of the picturesque, inspired by Classical landscape painting, with lakes bordered by rugged mountains, waterfalls and ruined buildings which had been the blueprint for 18th-century landscape gardens and follies. Now, some country houses were being designed as if they had been plucked from one of these pictures, freeing the architect from the strict rules of symmetry and proportion so that picturesque houses could use a variety of textures and shapes and, most notably, could be asymmetric. It was also the association made with the choice of style and site. For instance, a castle built on top of a rocky outcrop implies power, strength, solidity and inspires awe, which was more important than the architectural detail viewed closer at hand. Another factor which affected houses was the new materials and technology available: large panes of glass for windows; lighter slates for roofing which meant that flatter pitched roofs could be fitted; and oil, gas and later electricity providing lighting. As architecture started to blend with engineering, so iron posts and girders could be found lurking behind the brick or stone façade.

FIG 5.4: A symmetrical 18th-century Palladian house (top) and an asymmetrical Victorian Gothic one (bottom).

The period from 1800–1837 which is loosely termed Regency (although the Prince Regent only ruled as such in his father’s absence between 1811–1820) is notable for a wide selection of styles inspired by the drama of native ruins, new discoveries from Ancient Egypt and increased contact with the Far East. It was acceptable to deceive and imitate, most notably with brick walls covered in stucco and then scoured and painted to match fashionable stonework. The details of the house also become more delicate, with thinner glazing bars in the windows and intricate patterns formed by castiron used in balconies and verandas.

FIG 5.5: NETHER WINCHENDON HOUSE, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE: This ancient house received a Regency make over in the latest Gothick fashion which included facing much of the timber-framed parts in stone. Note the period features like the stout pointed windows with Y-shaped glazing bar, battlements and a balcony between the two nearest towers.

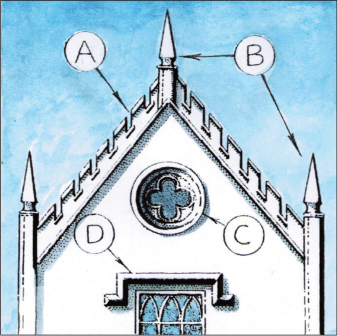

Gothick (the ‘k’ at the end differentiating it from the later Victorian Gothic) was a rather whimsical interpretation of medieval buildings. It was first applied to a complete house at Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, the home of Horace Walpole (youngest son of the first Prime Minister Robert Walpole). His restyling of this house from 1750 was a breakthrough in its asymmetrical design and use of Gothic details, which reflected the growing interest in romantic ruins of abbeys and castles. From 1790 a few architects produced new Gothick country houses with this more irregular layout, though for many this was purely applied to existing properties or new extensions. Details to look for are steeply-pitched roofs with end gables, pointed-arched windows, some with ‘Y’-shaped tracery, drip mouldings above openings, tall Tudor-style chimneys, and a painted stucco finish.

FIG 5.6: A Regency Gothick gable, with characteristic stucco finish, stepped battlements (A), pinnacles (B), quatrefoil (C), and hood or drip moulding (D) above the window.

Another popular form which peaked during the first half of the 19th century was the castle, a patriotic response to war with France or perhaps an owner’s desire to re-assert one’s social status in the subsequent period of worker and peasant discontent. The design had been inspired by romantic tales from the likes of Walter Scott and had been given acceptability by Robert Adam who believed that they were direct descendants of the architecture that the Romans had brought with them to these shores. Hence, they linked the Ancient World and Britain. Now alongside those castles which had survived the Civil War and had remained residences were erected new castles which, despite having the appearance of their medieval counterparts, can be told apart by the consistency of fine stonework throughout the building, a symmetrical façade and large windows neatly arranged in rows and columns. The castle remained an inspiration during the Victorian period and a variation called Scottish Baronial was popular. It developed north of the border and spread south after Queen Victoria acquired Balmoral in 1848. It is distinguished by tall outside walls surmounted by small corner turrets and round towers with steeply-pointed caps.

Foreign sources still influenced country houses, with a wider palette of styles now available to the architect. Italianate villas, featured in the paintings which inspired the Picturesque movement with round towers off-set to one end, low pitched roofs and deep overhanging eaves, and arcades of arched openings, appeared in a few locations and inspired smaller urban residences. Napoleon’s presence in Egypt had led to French archaeologists uncovering and making drawings of the great monuments they found. The Egyptian style which was inspired by these discoveries is characterised by thick round columns with lotus leaf capitals, walls which lean in at the top and large concave eaves, usually only details applied to a house or garden buildings. Increased contact with India and China inspired a number of houses, most notably the Prince Regent’s Royal Pavilion at Brighton. Its onion-shaped domes, exotic window and door styles, and chimneys disguised as minarets cover what was, until 1815, a modest Neo Classical house.

FIG 5.7: LOWTHER CASTLE, CUMBRIA: At first glance it looks a very convincing castle, but look again and a house emerges. Note the central block has tall windows, with smaller square ones above, and pavilions at each end of the building, just like a Palladian mansion. The theatrical arrangement of towers in the centre, the perfect symmetry and the regularly-positioned windows confirm that it was built by Robert Smirke from 1806–11. The family moved out in the 1930s and it was partly demolished in 1957 leaving just the shell although partial restoration of the shell and the gardens is now underway.

FIG 5.8: CRONKILL, SHROPSHIRE: Its stark geometric shapes almost give it a 20th-century feel, but it was the creation of John Nash in 1802 and was inspired by the Italianate buildings in the pictures of the 17th-century artist Claude Lorrain.

FIG 5.9: THE ROYAL PAVILION, SUSSEX: This outrageous blend of Indian-styled elements was designed by John Nash for the Prince Regent from 1815–22. At its heart, though, is a far more conventional Neo Classical villa (the left-hand section of the top view) which was expanded for the supposedly bankrupt Prince and his lover Mrs Fitzherbert by adding the central dome and wing on the right in 1787. The dotted lines show its position within the Royal Pavilion’s last incarnation.

Despite becoming the chosen taste of the arch enemy Napoleon, Classical architecture was still prominent in country house design during this Regency period. The latest designs were influenced by the discoveries from Greece, and the temple which was seen as Ancient Greek architecture in its purest form features in part on many houses from this date. The main body of the house tends to be plain, with the roof hidden from view and a portico or colonnade projecting from the façade, with simple Greek Doric or Ionic columns and capitals.

Victorian and Edwardian Styles

From the 1830s, brick comes back into fashion. A wider range of materials allows the pitch and covering of roofs to vary according to style, and asymmetrically-placed towers appear, often used to house tanks which provided running water under pressure for new toilets and bathrooms. Now with larger panes of glass available, the sash window could virtually dispense with glazing bars and give uninterrupted views across the owner’s property. Later in the period large houses were built which hugged the landscape or were modestly set within woodland rather than dominating their surroundings. Timber-framing which since the 17th century had been unfashionable became popular again, sometimes just cladding, other times structural and usually set on top of a stone or brick lower storey and painted black and white (a largely Victorian fashion).

FIG 5.10: SHUGBOROUGH HALL, STAFFORDSHIRE: The garden front of this late 17th/18th-century house (see Fig 4.6) had the distinctive Regency, shallow-bowed central extension added between 1803–6 in a Neo Classical style. The delicate arched verandas either side of it are also characteristic of this period.

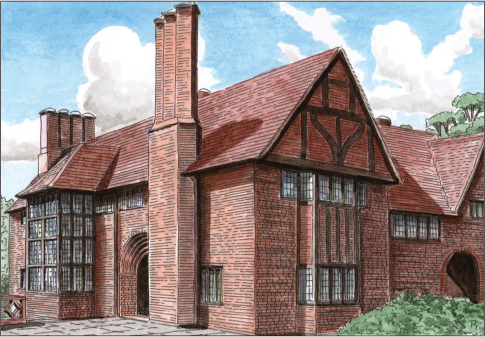

When Queen Victoria came to the throne there was intense religious debate centred on groups at Oxford, Cambridge and London as the Church of England faced up to an identity crisis. This in part had been caused by the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 which had removed most of the restrictions for practising Catholics dating back to the 16th century. One convert who rose to prominence at this time was Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin who, in a series of books, enthusiastically promoted Gothic architecture, based upon the accurate study of medieval buildings rather than the loose theme used in the earlier Gothick style. He argued that in order for buildings to have moral value they should not hide their function and structure and that they should use natural materials. This point of view had a dramatic influence upon Victorian architects. Pugin and others saw the Middle Ages, in particular the 14th century, as a time of high religious morality and the early buildings in this new Gothic Revival style use forms from this period for inspiration. There was no stucco hiding the materials used. Brick could once again be on show, with a preference for a rich red colour, with windows featuring pointed arches, tall slender towers and an asymmetrical layout being distinguishing features of early Gothic Revival houses.

FIG 5.11: BULSTRODE PARK, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE: The stocky Gothic tower in red brick is a typical mid Victorian feature. This muscular-looking building with an asymmetrical arrangement of spires, gables and battlements was built between 1861 and 1870.

FIG 5.12: TYNTESFIELD, SOMERSET: This extravaganza of Victorian Gothic Revival was built for William Gibbs from 1863 by architect, John Norton, with further additions made by Henry Woodyer and Arthur William Blomfield. It was purchased by the National Trust in 2002 after over £8 million was raised from the public in just 100 days, along with the largest single grant from the National Heritage Memorial Fund.

From the 1850s to ’70s there was a move to a more muscular form of Gothic, with dramatic decoration and stout towers, less influenced by the English Middle Ages and more by Continental sources. The most distinguishing feature of houses of this date is the use of polychromatic brick work where red or cream brick walls are broken by bands and patterns in lighter or darker colours.

Another popular inspirational source for country house building was the 16th century and early 17th century. Tudor red-brick houses and the imposing Elizabethan and Jacobean prodigy houses found fervent ground in this patriotic period (Fig 5.1). Even detail down to the strapwork decoration the Elizabethans so loved was copied, although the varying heights of windows depending on which floor the state rooms were in the original houses was usually not imitated.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert had Osborne House built in the style of the Italian Renaissance. It was inevitable that others would follow suit. Country houses and urban villas were designed in this Italianate style, with a peak of popularity in the 1850s and ’60s. It was characterised by the use of tall, round-arched windows, with large panes of glass; towers with a series of narrow-arched openings along the top and a low pyramid roof; shallow pitched roofs with large overhangs supported on decorative brackets; and was usually executed in a light colour brick or stone. Larger houses inspired by the same Continental sources might have a symmetrical façade with parapets and vases.

FIG 5.13: Examples of 16th-century brickwork (top) and 19th-century (bottom). The sharper edges and finer pointing of the later example is one way of identifying Victorian houses from the originals they were based upon. The patterns formed by the exposed end (header) and side (stretcher) of each brick varied through the ages. English bond (top) featuring a row of headers then one of stretchers was common in the 16th and early 17th century. Flemish bond with a header followed by a stretcher on each row became the more popular from this point up until the late 19th century when English bond was revived.

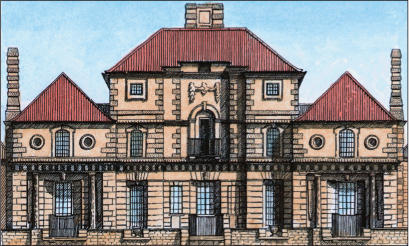

FIG 5.14: BRODSWORTH HALL, SOUTH YORKSHIRE: This mid Victorian Italianate house differs from earlier Classical styles in the mouldings around the windows, French doors, and two roughly equal height floors. Note there are no Classical columns on this façade as free-standing types were not favoured by Victorians, except on the portico across the entrance (right) which was a typical 19th-century feature.

FIG 5.15: WADDESDON MANOR, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE: A Victorian country house in the style of a French chateau, designed by the architect Destailleur. It was built in the 1880s for Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild, a member of a large Austrian banking family whose various relations purchased five other properties within Buckinghamshire because of its close proximity to London and the excellent hunting in the county.

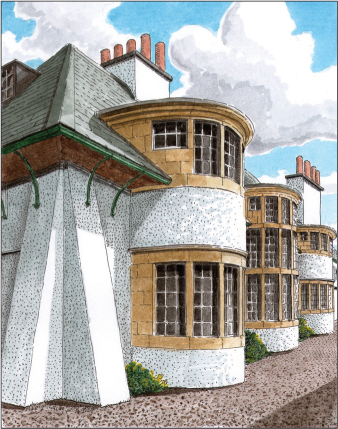

A French style of architecture became popular during the second half of the 19th century due to the fashionable changes which were taking place in Paris under the reign of Napoleon III. This so-called Second Empire style is usually recognisable by the use of mansard roofs (which have a shallow top slope, followed by a steep lower one) and lines of dormer windows. These windows allowed rooms to be put into the usually limited roof void and made them popular in urban buildings where space was at a premium. Out in the country the chateaux with steeply-angled roofed towers and Baroque-type decoration also inspired a number of projects.

From the 1860s a new generation of architects began to find inspiration not in mighty medieval buildings but less imposing manor and farmhouses of the 16th and 17th centuries. Rather than designing strict copies, they used these sources to create new forms. They may at first seem similar to the originals, but on closer inspection their layout can be revolutionary and the details strikingly modern, especially in the hands of Arts and Crafts architects at the turn of the 20th century. Richard Norman Shaw was one of the leading designers in this Old English style who created country houses which no longer reached up to the sky and dominated their surroundings. They were more humble, low structures designed with the demands of the family taking precedence over the appearance of the exterior. Although they could feature the latest technology and modern materials, the façades presented the viewer with the impression that the buildings had grown progressively over centuries. They were characterised by long, sloping, tiled roofs overhanging low walls, with exaggerated tall brick chimneys, and mullioned windows filled with leaded glass which were often set in long rows tucked right up under the eaves.

FIG 5.16: CRAGSIDE, NORTHUMBERLAND: This dramatically-set mansion was designed by Richard Norman Shaw from the late 1860s, with inspiration coming from 16th-century manor houses, with timber-framed gables, mullion windows and tall chimneys. It was notable for being the first house to have electric lighting.

As Norman Shaw turned his attention to developing new styles like the Queen Anne-style based upon the houses of the late 17th century with Dutch gables and white painted woodwork, (most timber was painted dark colours or grained to look like hardwood in this period), those who had been educated in his practice went out and developed the domestic revival styles further. The Arts and Crafts houses of the 1890s and early 1900s which they created used vernacular materials. This empowered skilled craftsmen to produce beautiful, quality fixtures and fittings, with the architect taking control of the whole project from the structure down to the handles on the doors. Most of the buildings produced by architects working under this banner were modest country houses or summer retreats, often incorporating an older building or feature which the architect now made a special point of preserving.

FIG 5.17: WIGHTWICK MANOR, WEST MIDLANDS: An Old English-styled house, asymmetrical, with a timber-framed exterior and Arts and Crafts interior. It does not tower over its site but spreads out with low-slung roofs, tall chimney stacks and an assortment of 16th-century window styles so appears to have evolved over time rather than having been erected in the 1880s and early ’90s.

FIG 5.18: STANDEN, SUSSEX: Designed by Philip Webb in the early 1890s around an old farmhouse which had been purchased by a wealthy London solicitor James Beale, it not only retained elements of the original building but also used local materials and a form which suggested it had grown progressively over centuries.

FIG 5.19: HEATHCOTE, LEEDS, YORKSHIRE: This suburban villa designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in 1906 combines the Arts and Crafts’ use of local materials, with a variety of Classical sources to create a unique form of building characteristic of the great architect’s later work. The form is Palladian (see Fig 4.14) but with late 17th-century, Baroque-style details and stone from quarries at nearby Guiseley and Morley.

This was a time of great nostalgia. Traditional pastimes were revived, the National Trust was formed and Country Life magazine published for the first time. This magazine played a large part in promoting the designs of a young Sir Edwin Lutyens who, after producing some of the leading Old English-style houses, turned his attention to Classical styles. He used his unique skills to create new forms guided by the orders rather than direct copies of ancient buildings. The Edwardian period, in which the houses he created were most influential, is characterised by this mix of styles from Imperial classical buildings to recreations of Georgian houses, with symmetrical façades featuring distinctive low-arch tops to the sash windows.

The Layout of Houses

Despite an obsession with reviving the past, the layout of houses reflected the changing social climate and the demands of the new aristocracy. The piano nobile which dominated in the previous century was gone and the main rooms were now on the ground floor. The procession of state apartments became a thing of the past, with more informal rooms arranged in a less strictly symmetrical manner. Rooms were increasingly dedicated to a precise purpose in the 19th century, with morning, breakfast, smoking, music, and billiards rooms frequently appearing in the plan. In Arts and Crafts houses there was an emphasis upon the revival of the hall as a communal space. The careful control of light and the use of different levels of floor and height of ceiling made for innovative interiors. The awkward problem of where to site the service rooms was generally solved by building a courtyard or rear wing often to the north of the house. This meant the food was nearer to the dining room than it had been when sited in the 18th-century pavilions. With no restriction upon size, these service areas could incorporate the large number of specialist rooms required to service the ever-increasing demands of a Victorian country house.

FIG 5.20: A cut-away view of a Victorian country house, with the principal rooms now on the ground floor dedicated to a more precise use. Upstairs are the bedrooms and dressing rooms, while the service rooms are in the separate kitchen court at the rear. Note that the central stairwell is top lit by a glass ceiling light; these more imaginative illuminating effects are a feature of 19th-century houses.

The picturesque landscape gardens which appeared to draw right up to the house were by the Victorian period outdated. Now there was a return to terraces and flower beds which could be viewed from fashionable French doors and verandas. Exotic plants and trees from the furthest corners of the Empire were in vogue now that large glass conservatories and greenhouses had been developed. These were often built as a wing or even part of the structure of the house, a distinctive feature of 19th-century country houses.

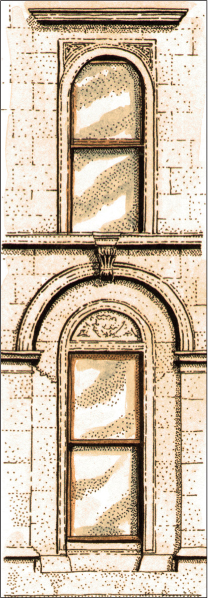

FIG 5.21: Two Italianate-style windows with their distinctive Romanesque (semi circular) arches and large, single panes of glass with no glazing bars. Raised mouldings around the windows and decorative details above and within the arches often help to differentiate Victorian houses from earlier work.

FIG 5.22: An Italianate-style tower with arched openings, balustrade and urns. Another common design had triple arched openings with a flat pyramid roof, as popularised at Osborne House.

FIG 5.23: A pointed arch formed out of brickwork above a sash window was a common way of integrating the Gothic style into a façade without compromising the practical rectangular shape of the window. The use of cream, grey and red bricks was popular in the 1860s and ’70s as were bands of patterns and decorative crests on the roof.

FIG 5.24: Roofs on Gothic and Arts and Crafts houses were a prominent feature with gabled ends exposed and decorative bargeboards fitted under the eaves as in this beautifully-carved example from Wightwick Manor. Roofs were steeper pitched and could stretch down to the top of the ground floor (low-slung) on Arts and Crafts houses. Casement windows (side-hinged) were reintroduced in the late 19th century but usually have rectangular leaded lights, as in this example, rather than the diamond shapes widely used in the 16th century.

FIG 5.25: Arts and Crafts houses had plain mullioned windows in the bays, as featured here at Broadleys, Windermere, by C.F.A. Voysey. They were often tucked tight under the eaves of low-slung roofs. Shallow buttresses and deep overhanging eaves were also distinctive of this style.

FIG 5.26: Chimneys once again become a feature as architects were happy to expose the functional parts of the house rather than hide them behind a balustrade. Tall stacks copying Tudor styles were a key part of the design of many Old English and Arts and Crafts houses in the late 19th century, as here at Deanery Gardens, Sonning, by Sir Edwin Lutyens.

The Demise of the Country House

On a sunny day in May 1869, upon a barren plain some 56 miles west of Ogden, Utah, USA, the final spike where two railroad tracks met was about to be driven home by Leland Stanford of the Central Pacific. His stroke with the hammer missed, but the eager telegrapher was already sending the message that the first trans-continental railway across America was complete. Now huge quantities of grain and livestock from the west could be moved east by train and then, aided by breakthroughs in refrigeration, shipped abroad. Back in England, landowners sitting in their country houses were basking in the warm glow of a golden age in farming. They were oblivious to the fact that, by the mid 1870s, American imports were keeping the price of corn steady and in the following decade lowering it. The agricultural depression triggered by these imports and the effects of a general economic downturn, meant reduced rents and income for the aristocracy. They were also affected by a loss of power as most males received the vote and were hit by increased bills from the introduction of death duties in 1894, and higher rates of income and super tax in 1909.

FIG 5.27: EXEMPLAR HALL c.1900: Some 40 years before this view is dated, the latest owner embarked on an expansion programme creating a wing to the right of the picture, with additional rooms for leisure and guest accommodation, a conservatory (left), a tower to hold the water tank and an enlarged service courtyard in the foreground. This was a time of great prosperity on the estate due to high agricultural returns, but by 1900 a sharp downturn in fortunes has resulted in the sale of much of the farm and parkland which is being swallowed up by new villas and terraces from the rapidly expanding nearby town (top).

Unfortunately the situation would only get worse, Having lost the sole heir during the First World War and the aging lord of the manor shortly afterwards, the family’s mounting debts and death duties forced it to sell Exemplar Hall and it became a private school. This was poorly run and by 1939 was in the hands of the armed forces as a training centre. At the end of the Second World War the council of the local town which by now had engulfed what was left of the estate purchased the site but the lack of maintenance had left the old hall unsafe and the majority of the building was demolished in the 1960s. Only the old kitchen courtyard was retained and has become offices while the remainder of the estate is now a public park. After all these years, only the church and its surrounding boundary have survived from the original scene in 1400.

Many houses had already been sold off or left empty before the First World War. Worse was to come, however, especially for those families who lost male heirs in the conflict and could not pay the tax demands and bills in the tight economic climate after the war. During the 20th century these huge buildings designed for a more affluent generation became a drain on the upper classes. Large numbers became schools, hotels and offices, or were partially or completely demolished (Fig 5.7), only surviving today in the name of an estate which was often built over, swallowed up by rapidly expanding suburbs as happened at Exemplar Hall.

Thankfully, many country houses have survived although often only through diversification into other fields like theme and wildlife parks, museums, and as locations for special or corporate events. Some still remain in the same family, others maintained by bodies like the National Trust and English Heritage. If you take what was once the six Rothschild houses around Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire (Fig 5.15) as an example, they are now an RAF camp, a hotel, a religious centre, an out of bounds school, with the two remaining ones open to the public through the National Trust. None of them remain in the family’s hands.

FIG 5.28: CASTLE DROGO, DEVON: Completed in 1930 and then on a much reduced scale from Lutyen’s original grand scheme, this modern interpretation of a castle is often regarded as the last great country house and marks the end of the age of aristocratic rule.