Once you’ve got some practice with flash under your belt, you can branch out and really get creative. High-speed sync is a feature that lets you do just that. Let’s say you and your family have planned a family outing in a nearby park where many colorful flowerbeds are pronouncing that spring has arrived. You’d love to get some nice portraits of your wife and kids, using the flowers as a wonderful backdrop of out-of-focus tones and colors. As is often the case, your spouse doesn’t share your joy of rising at the crack of dawn and rushing out the door for excellent photographs. As a result, it isn’t until about 12:45 PM that you all arrive at the park, and your family members want to get the “photo stuff” over with so that they can all just relax and enjoy themselves.

Oh, man, are you ever under the gun! Your family has no clue about light and photography, and explaining the principles of midday sunlight would only be an exercise in futility. They just want you to make it happen as quickly as possible, so let’s make it happen—despite that harsh, midday light! Do you think wedding photographers get away with telling a bride she can’t be photographed outside in the garden at midday because it’s too bright? Heck, no!

This is where high-speed sync comes in. By now you know that to get the most power from your flash you must use it at the full-power setting of 1/1 and with a shutter speed no faster than the maximum sync speed. However, high-speed sync is a feature that allows you to use your electronic flash at shutter speeds much faster than the maximum sync speed. Ever since high-speed sync came on the scene, wedding and portrait photographers the world over have used it to shoot brides in scenic flower gardens at midday.

Canon calls its high-speed sync feature High Speed Sync (HSS) on its 580EX flash. Nikon calls it Focal Plane (FP). With either system, you must first activate this feature to sync your flash with superfast shutter speeds. In Canon’s case, you activate the feature on the flash with the press of a button (refer to your flash manual for the exact instructions). With Nikon flashes, you go to Camera Menu and select Custom Feature; scroll down to Bracketing/Flash, and then choose Sync Speed 1/320s. After I set my Nikon D300S to that 1/320s sync speed, the back of my flash shows the FP icon, assuring me that I am indeed operating in high-speed sync mode.

So there you are, midday, shooting portraits of the kids about 30 feet in front of the most colorful flowerbed you could ever imagine. Choosing an f/4 to render the background flowers out-of-focus tones and colors, your meter indicates a shutter speed of 1/5000 sec., due to the bright conditions surrounding you. And of course, the light overhead is harsh on your subject’s faces. But no worries, as you call on your flash—mounted off camera—to create nice, even fill light on their faces. You frame up a good composition at a focal length of 105mm, and everything looks superb in your viewfinder. You’re almost ready. You simply set the camera to high-speed sync and manually push the zoom button on the flash so that it registers 105mm. At ISO 200 and f/4 for 1/5000 sec., the flash distance scale indicates a flash-to-subject distance of 7 feet for a perfect exposure, so you place yourself 7 feet from your subject and bingo, bango, bango! You’ve done it: an impressive and beautiful portrait shot at midday. You’re one smart cookie!

How the heck is it possible to suddenly shoot a correct flash exposure at shutter speeds that are much faster than the maximum sync speed? It’s possible because electronic flash has a special talent. While it usually produces a single burst of light when shooting at the normal maximum sync speed, when operated in high-speed sync, the flash momentarily becomes a high-speed strobe light, firing multiple times (actually, hundreds of times per second) when using those superfast shutter speeds. With fast shutter speeds, as soon as the first curtain of your shutter begins to open, the second curtain is right on its tail, closing in very quickly on the first. While this narrow slit between the curtains moves across the digital sensor (or film plane), the high-speed synced flash repeatedly illuminates the scene (strobe-light style). Due to this pulsating light, the subject is exposed to the light of the flash, albeit through a ridiculously small slit in the curtain.

No doubt you’re by now convinced of the usefulness of high-speed sync, making it one more powerful tool at your creative disposal. With Nikon and Canon cameras, you can leave high-speed sync engaged so that it’s available for all flash pictures when you need it. When high-speed sync is turned on, you can take a flash picture at any shutter speed, at any time—and without thinking about your designated sync speed. You may be thinking, I never have to worry about anything ever again and can shoot away. This idea makes sense in theory, but I wouldn’t recommend it. If you take a look at the facts and figures mentioned in the box opposite, you’ll see that simply turning on high-speed sync automatically cuts your guide number almost in half. That’s a lot of lost power, especially if you don’t really need high-speed sync for what you’re shooting. Let’s say that you accidentally change your shutter speed from 1/250 sec. to 1/1000 sec. At 1/250 sec. your guide number was 160, but at 1/1000 sec. it’s now 40. Accordingly, your subjects can be no farther than 5 feet from the flash for a correct exposure. If you’re shooting a portrait from 15 feet away with your flash attached to your camera, your flash output will be too weak to illuminate your subjects. While high-speed sync is a wonderful feature, it can trip you up if you leave it on for all of your shooting. Consider using it only when necessary, and turn it off when it’s not.

When you keep in mind that much of what can be done with a flash outdoors should involve the use of the ambient light, you’ll soon come to the same conclusion that I did some time ago: Every minute of the day or night affords an opportunity to use your flash. I never really thought I would hear myself saying that! Until recently I was a big fan of chastising anyone for shooting during midday light, suggesting instead that we all meet at the pool and work on our tans, but of course we now know that even during midday—and especially with high-speed sync—great flash photography can be achieved. In fact, that’s one of the greatest reasons to embrace flash.

Are there any downsides to shooting in high-speed-sync (HSS) mode? Only one, really, and it has to do with the flash output power. While high-speed sync fires a series of stroboscopic bursts at an extremely quick rate, the flash output of each burst is of lower flash output power. The lower output is what allows speeds of 1/8000 sec. or more. This reduced flash output averages around 1/2 to 1/4 the output of full-power (1/1) flash. Essentially, each time you quadruple your shutter speed, you cut the guide number in half. Here are some figures, and you can see the reductions:

| SHUTTER SPEED | APERTURE | FLASH MODE | RATIO | FLASH RANGE | FLASH MODE | GUIDE NUMBER |

| 1/250 sec. | f/16 | Manual | 1/1 | 10 ft. | Normal | 160 |

| 1/250 sec. | f/16 | Manual | 1/1 | 10 ft. | HSS | 80 |

| 1/500 sec. | f/11 | Manual | 1/1 | 7 ft. | HSS | 60 |

| 1/1000 sec. | f/8 | Manual | 1/1 | 5 ft. | HSS | 40 |

| 1/2000 sec. | f/5.6 | Manual | 1/1 | 4 ft. | HSS | 30 |

Do you really have to do this math? Nope. Just get back to that flash distance scale; it will tell you all you need to know. With less power in high-speed sync, you need to be much closer to your subject than normal to generate the same effect of a full-power flash exposure. How much closer? That will depend on just how fast your shutter speed is, but know this: The faster the shutter speed, the shorter the flash-to-subject distance. You can see this by simply placing your flash on the camera’s hot shoe with both the camera and flash turned on and with the flash set to high-speed sync. Set the aperture to f/8, and start cranking up the shutter speed dial on your camera. Watch the flash distance scale indicate shorter and shorter flash-to-subject distances as you increase your shutter speed from 1/250 sec. to your fastest available shutter speed.

During a recent workshop in Tampa, my students got to try their first of many high-speed-sync photographs. Our model Deana made numerous leaps for us, and because Deana would be flying by all of us from right to left, we definitely wanted to use a faster shutter speed to freeze the action. When I recommended at least 1/4000 sec., several students were quick to ask, How the heck are we going to do that when my fastest flash sync speed is 1/200 sec.? All my students that day had the Canon Speedlite 580EX II, but they had no idea their flash offered high-speed sync.

So with their shutter speeds set to 1/4000 sec., I told them to take a natural-light reading of the strong backlit sky. An aperture of f/5.6 was indicated. I then asked what distance their flashes indicated for f/5.6. At ISO 200, it was approximately 4 feet. I told them to get down in the sand and prepare to shoot upward, and I marked a spot in the sand approximately 4 feet from them and their flashes (which were mounted on camera). That would be Deana’s launch point for her leaps, as you can see in the first image. The second image shows a natural-light exposure without flash, but above, you can see the benefit of high-speed-sync flash.

Third image: Nikon D300S, 12–24mm lens at 16mm, ISO 200, f/5.6 for 1/4000 sec., Speedlight SB-900

Wouldn’t it be great to be able to shoot backlit outdoor subjects that are beautifully lit by your flash but that also record a correct exposure of very bright and powerful backlight? Well, as we just discussed, it is possible to do just that with the aid of high-speed flash sync, but some flashes don’t offer this feature. There is another solution when you’re faced with “impossible” ambient-light exposures that are normally out of the range of the fastest sync speed—and that solution comes in the form of a neutral-density (ND) filter.

Shooting from a low angle with my wide-angle lens, I framed these tulips in the foreground while shooting up to the east into the mid-morning sky and sun. With ISO 200, my exposure was f/11 for 1/2000 sec. This reading came as no surprise, because the superbright background heavily influenced the light meter. When I shot at these camera settings without flash, I recorded a nice exposure of the sun and sky, but my flowers were quite dark (first image). Setting an exposure for the flowers (f/11 for 1/60 sec.), however, resulted in an overexposure of that much stronger background light (second image).

Since I wanted to record a correct exposure of the flowers as well as the sun and sky, and since I wanted to maintain great depth of field for a storytelling image, I had but one reasonable choice: use my flash and light up those flowers to be the same exposure as the sky and sun. Simple math told me that under normal circumstances I couldn’t use my flash because I was determined to use the exposure for the sky and sun, which was, again, f/11 for 1/2000 sec. For most cameras, 1/2000 sec. is beyond the fastest sync speed—unless you use high-speed sync or an ND filter. I chose the latter in this case.

Immediately after placing my 3-stop ND filter on my lens, my meter indicated an exposure of f/11 for 1/250 sec. for the sun and backlit sky. Certainly 1/250 sec. is well within the range of a normal sync speed. After powering down the flash to 1/32 power, the distance scale indicated that at f/11 the flash would cover a distance of just around 2 feet. That worked for me, since I was using my full-frame fish-eye lens for this composition and wanted to get about that close to those large, colorful tulips. And since I was shooting in the vertical format, I removed the flash from the hot shoe and used it with a sync cord. I held the flash above the foreground flowers from a distance of about 2 feet and tripped the shutter release. I was then able to record a daylight exposure of my foreground tulips without sacrificing my daylight exposure of the sun and sky—all because I used an ND filter!

All photos: Nikon D300, 14mm fish-eye lens, ISO 200. First image: f/11 for 1/2000 sec. Second image: f/11 for 1/60 sec. Third image: 3-stop ND filter, f/11 for 1/250 sec., Speedlight SB-900

A cheap and viable alternative to high-speed sync in many situations is to use a neutral-density (ND) filter. The neutral-density filter simply reduces the intensity of the light that passes into your lens, as if your camera is wearing sunglasses. This, in turn, causes your light meter to offer up a much slower shutter speed for the scene before you. A neutral-density filter will typically force you to drop your shut-ter speed by 3 or 4 stops (depending on the filter model), and more often than not, that reduction in light will be enough to return you to the more familiar flash sync speeds offered by your camera.

You’ve surely noticed the references I made earlier to zooming your flash. If you haven’t already discovered this really cool feature on your flash, you’ll want to do so right now. Just like the telephoto zoom lens that brings subjects closer to you, the zoom on your flash is meant to push light farther. Let’s say you want to photograph your daughter standing 25 feet away under the shade of the maple tree using your telephoto zoom at the focal length of 105mm and illuminating her with your flash. How are you supposed to do that? You’re going to zoom the flash head so it matches the focal length set on your lens, that’s how.

Zooming the flash head causes the beam of flash light to narrow. When the beam of the flash narrows, the flash’s light travels farther. It’s a lot like water through a garden hose. Without the benefit of a nozzle, water gushing out of the hose can only travel so far. With a nozzle on the hose forcing the water through a narrower opening at an increased pressure, the water travels a lot farther. Flash light doesn’t have pressure, but it does gain intensity when focused into a narrower beam. When you narrow the flash beam, the more-focused light travels a greater distance rather than spreading out and dissipating.

When you start playing around with the zoom on the flash, you’ll quickly see just how that angle of the light output can go from wide to narrow. So again, the narrower the angle of the flash head (or the more “zoomed in”), the farther the light output can travel in one direction. Just don’t expect this zoomed-in flash to light up a four-lane freeway, since the flash will be traveling down a much narrower road.

Now, you may have noticed that your flash head has a feature that zooms it automatically as you change the focal length of your lens. Well, I’m here to tell you to disable this feature. Why would you disable it? Because when it’s enabled, your flash head follows your lead and changes its angle of view whenever you change the focal length of your zoom lens. This is useful if you’re shooting a fast-paced event during which you’re constantly zooming in and out. However, this feature only works when the flash is mounted on the hot shoe or attached to the hot shoe via a cord. Since you’ll want to use your flash off camera in many situations, it’s best to disable the auto-zoom feature on the flash. Manually setting your flash zoom will also allow more creative freedom for exposures in which you might not want your flash zoom setting to match your lens focal length—for example, when you want to illuminate deeper into a scene than your angle of view for a particular effect. So open up your flash menu, and turn off the auto zoom, thereby ensuring that you will manually set your flash zoom for each shot.

When I took this shot, the Chicago weather forecast had called for yet another worthy winter snowstorm, and since I had missed the last worthy Chicago snowstorm while on a trip to New Zealand, I was determined to try my hand at flash in this storm. I had this idea to capture falling snowflakes against a dawn sky that would also include one of my favorite trees in a nearby park. All I needed was some light snowfall and a willingness to rise before dawn.

Now you might be asking yourself, How is it possible to have a dawn sky of any color when it’s snowing? I wasn’t expecting a clear dawn sky but the typical gray sky that one gets with snowfall, but I also knew that at this early hour even a gray sky would record a bluish hue. The bonus on this day was a really small sliver of clear sky on the horizon, somewhere over Lake Michigan; this got me some subtle magenta near the bottom of my composition.

So there I was, lying in the snow with my camera on tripod and my 12–24mm lens at a focal length of 20mm. With my aperture set to f/5.6, I focused on the tree and adjusted my shutter speed until 1/15 sec. indicated a correct exposure. All that remained was to fire up the flash in Manual exposure mode, setting it to f/5.6 at full power and then setting the zoom of the flash to 105mm. Now why would I set the zoom of the flash to 105mm when shooting with my lens at 20mm? Because I wanted the flash to travel farther into the scene, illuminating snowflakes that were both close to me and farther away. This, in turn, created far more depth than if my flash were set to the 20mm focal length. The resulting image almost looks like one of those star-trail time exposures or even a meteor shower. Just another example of having fun with a single flash!

Nikon D300, 12–24mm lens at 20mm, f/5.6 for 1/15 sec., Speedlight SB-900

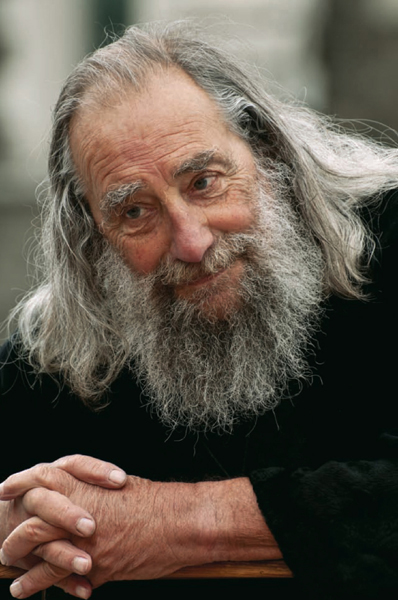

He’s called the Wizard of Christchurch, and just like clockwork, he shows up in his wizard costume, along with his 6-foot wooden ladder, in the town square of Christchurch, New Zealand, every day at 2:00 PM—rain or shine. Over the course of the next 45 minutes, he dispenses a great deal of advice on subjects ranging from sex to war to politics to religion. He is not only entertaining, but if you listen closely, much of what he says is actually insightful. When I saw the Wizard in the winter of 2010, I, like so many others before me, quickly succumbed to the temptation to photograph his wisdom-filled face, and I set up about 20 feet away from him (first image).

This particular day was quite overcast, so I opted to use my flash along with an amber gel to get a much warmer Wizard portrait. I needed to shoot wide open, because I was handholding the camera for this shot, and you get the fastest possible shutter speed when the lens is wide open. With the 70–300mm zoom lens I was using, at the 250mm focal length I wanted, that meant f/5.6. Considering the heavy overcast sky, I was in no danger of my shutter speed exceeding the maximum sync speed. So at 250mm, ISO 200, and f/5.6, the camera meter indicated a shutter speed of 1/160 sec. for a correct daylight exposure.

I then zoomed the flash head all the way to its maximum of 200mm. I dialed in my aperture of f/5.6, and the distance scale told me I needed to be at 41 feet! Yikes! I was a heck of a lot closer than that—about half that distance, in fact. But neither the flash nor the distance scale knew I was using an amber gel on my flash or that the flash was in a softbox. These factors combined to reduce the flash output by about 2 stops. That loss of flash output meant I needed to choose a distance that would be equivalent to 2 stops less power. So I dialed down the flash’s aperture wheel 2 stops and saw that f/11 was good for a flash-to-subject distance of 20 feet. Hot-diggity, I was at 20 feet! So even though I was shooting at f/5.6, I used the distance for an aperture of f/11 because my softbox and gel cost me about 2 stops of exposure.

Finally, because I wanted to underexpose the ambient light a bit, I chose to shoot at a 1/250 sec., knowing that my flash would provide the “daylight” exposure on the Wizard’s face. When the Wizard paused his animated speaking momentarily, I fired off the shot opposite and was quite happy with the result. I then turned off the flash, brought my shutter speed back down to a correct natural-light exposure of 1/160 sec. and fired off another shot (second image). Comparing the two, I think the flash exposure provides a more flattering image because of the added warmth and sparkle in the Wizard’s eyes.

Both photos: 70–300mm lens at 250mm, ISO 200. Third image: f/5.6 for 1/250 sec., Speedlight SB-900. Second image: f/5.6 for 1/160 sec.

As you’ve no doubt surmised by now, using your flash off camera is really the way to go. Imagine the possibilities if you had several flashes and you could place them anywhere in your scene and use them to simulate any kind of light. The ability to use multiple flash units—all triggered wirelessly—increases your creative options exponentially. Wireless flash has unlimited potential, so let’s take a look at how it works.

Flash units that aren’t connected to the camera by a dedicated sync cord need to be triggered wirelessly to flash at the appropriate time. There are many devices available for triggering your off-camera flash, including sync extension cords, optical slaves that “see” the other flashes fire and trigger the one they’re attached to, radio remotes, and designated devices. Today’s newer flash units come with wireless flash capability built in; these systems can trigger as many flash units as you have, provided they’re all compatible with your system.

The advantages to dedicated wireless units are (1) having no wires between the camera and flash (or flashes), (2) the ability to place the flash (or flashes) a great distance from the camera, and (3) through-the-lens (TLL) features that can adjust each flash unit’s output levels right from the camera. (For the TTL features, you need one master flash or triggering device and some flash units acting as slaves. With Canon dedicated units, you place the master flash unit in the hot shoe and slide the switch to Master; the master will then trigger all the other units in your lighting setup that are set to Slave. Nikon works similarly, with a master unit in the hot shoe to trigger the slaves. Newer camera models with pop-up flash have a feature that allows the pop-up flash to be used as a master flash that triggers slave flashes, a menu option that is sometimes called Commander.)

The Town Square in Christchurch, New Zealand, is filled with a host of characters on most any day, but as is true with most cities and towns, the abundance of characters are found on the weekend. This particular man caught my eye as he passed by me on his unicycle while juggling three red balls. I made a point of getting his attention and engaged him in conversation. After a while, I asked him if I could take his photograph and he, obviously, agreed.

Considering his long hair and beard, he was a candidate for what I call a sunset-portrait-on-the-beaches-of-Hawaii shot. You may be familiar with portraits that are actually shot against the bright backlight of a sunset on the beach, but did you realize that you can replicate that same ambient exposure with a flash—and even do so when you’re miles away from the beach? Take a look. In the first photo, I’ve got the composition of my frame-filling portrait set, and handholding the camera, I set my aperture at f/8 and adjusted the shutter speed until the camera’s light meter indicated 1/125 sec. as a correct exposure from the light reflecting off his face.

For the second photo, I called on the aid of my flash with the same exposure, but note the bright backlight of the “sunset” behind him and how his hair is aglow. How did I do that? I first set an aperture of f/8 on the flash and found that at full power I’d need a flash-to-subject distance of 12 feet for a correct exposure. However, a correct exposure was not what I wanted here. In fact, I wanted the flash exposure to record as an overexposure so that the eye/brain would be fooled into thinking there was a sunset behind the subject. I knew that if I placed the flash about 3 feet behind the subject’s head (pointing toward him), a gross flash overexposure would result. With one PocketWizard attached to my flash and another mounted on the camera’s hot shoe, I was able to fire remotely, and I had one of my students hold the flash in position, 3 feet behind the subject. A backlit sunset portrait was the results.

Both photos: 70–300mm lens, f/8 for 1/125 sec, ISO 200. Second image: with Speedlight SB-900

To recognize the master signal, each slave unit is assigned an ID, allowing its power output to be adjusted right from the camera. Imagine being able to adjust your key flash and fill flash, no matter where they are and all from the camera! Also, if you have a flash in the hot shoe or are using the pop-up as the master unit, that master can be set to act only as the trigger for the other units in your setup—without outputting any flash light.

If you’d rather not dedicate an expensive portable electronic flash as the master triggering unit and your camera doesn’t come with a Commander feature, you can use the manufacturer’s dedicated infrared (IR) triggering devices. Canon and Nikon both have devices that you mount to your camera to serve as triggers to wirelessly control your off-camera flashes. Just remember, you don’t need these IR triggers if you always have one of the flashes on camera acting as master. The IR trigger just offers a lower-cost alternative to using a flash to trigger the slave units. That way you can use your expensive flash units off camera to illuminate your composition as creatively as possible.

There are some drawbacks to IR triggers, and one is that when used outside in bright sun, they aren’t always reliable, as the sun interferes with the IR signal. Also, when used outside, the trigger must be in a slave unit’s line of sight for the slave to receive the IR signal. This eliminates setups in which you hide a flash behind an object. Indoors, this isn’t a problem, as the signal can bounce off walls to reach the slave, but outdoors it becomes a challenge. IR triggers are also limited by the required distance between trigger and slave. So before you invest heavily in these devices, be sure to do your research. Many pros using wireless portable-flash systems prefer the wireless radio remotes over IR devices, because the radio signal doesn’t require a line-of-sight or suffer from distance issues.

There are many manufacturers of radio remote devices for wireless triggering, including PocketWizard, Quantum, RadioPopper, and MicroSync. One word of caution is that you research the devices thoroughly. Some triggering devices can’t sync fast enough to be used in high-speed sync situations; this means the camera shutters close before the flash burst is complete.

Wireless flash technology has become the rage, and many established pros are leaving their heavy studio lights back at the studio in favor of lighter, wireless flash kits when photographing on location. For example, portable flash can easily work as key light and fill light, a combination that works very well for portraits even outdoors. The key flash is placed off to one side so that the light wraps across the subject and sculpts the face by creating light and dark; an additional flash (or flashes) can then be added to create fill flash that lowers contrast and fills in shadow areas. If you have enough portable wireless flash units, you can also add a hair, edge, or background light for more accents on your subject.

Here’s another example of creating that backlit sunset effect, and I’m including it so that you can see the previous setup. In this covered parking garage, the camera meter indicated an exposure for the model’s face of f/8 for 1/125 sec. based on the ambient light. Great friend and photographer Robert LaFollette agreed to be my VAL (voice activated lightstand), an acronym coined by the iconic flash master Joe McNally. Robert stood close behind our model, about 3 feet from her, and held up the flash, which I had covered with an amber gel to provide the warm, sunsetlike tones.

With my flash and camera set to Manual, and with the flash powered down to 1/2 power, the flash distance scale told me I needed to shoot at f/16. However, in this case, I wasn’t going to use f/16 but rather f/8. But wait—using f/8 would mean that the flash exposure would be 2 stops overexposed, wouldn’t it? Yes, it would, but I had a really good reason for wanting the flash exposure to be overexposed, as you’ll soon see.

First, though, I needed to set a correct exposure for the model’s face. With my aperture set to f/8, I zeroed in on her face and adjusted the shutter speed until my camera’s meter indicated a correct exposure at 1/125 sec. Sure enough, when I tripped the shutter release, the flash fired behind the model’s head, and in that instant, I recorded a correct exposure of the natural light reflecting off her face. At the same time, I recorded a 2-stop overexposure around the edges of her hair, which was illuminated by the flash behind her head. The edges of her hair were overexposed, as I intended. The reason I wanted that overexposed look was to get that sun-going-down-behind-her look. If this were the real sun setting behind her, it, too, would record as a 2- or 3-stop overexposure (assuming, of course, that you had set an exposure solely for the natural light falling on her face). It really is this easy! And now that you know this, go grab your significant other or the kids. It’s time to pretend the sun is going down behind them!

70–300mm lens, f/8 for 1/125 sec., Speedlight SB-900

Do you need a special flash to illuminate your friend standing among the trees at dusk along the shore of Chicago’s Lake Michigan? It may appear that way, but the fact is, you can easily make this very simple shot with one portable electronic flash. Although I was over 150 feet away from my subject, my flash was not. In fact, with palms outstretched, my subject was holding the flash pointing up at himself. The Speedlight SB-900 in his hands was connected to a small radio remote that he was also holding. With another PocketWizard mounted on my camera’s hot shoe, the two could now “talk” to each other, and once I pressed the shutter release, the flash fired.

Remember, correct flash exposure is 100 percent dependent on the right aperture choice, and the right aperture choice is always determined by the flash-to-subject distance. My distance from the subject is meaningless, unless I’m shooting with the flash mounted on the camera’s hot shoe. I estimated that when my friend held the flash out in front of him, the distance from the flash to his face was about 2 feet. So that’s my flash-to-subject distance. I also took into account that I wanted to record the ambient-light exposure of the dusky blue sky and the surrounding trees. Did I have any depth-of-field concerns? No, not really, since the trees and my friend were basically at the same focusing distance. So I used a “Who cares?” aperture of f/8. When I set f/8 on my flash, the distance scale told me that at roughly 1/64 power my flash would illuminate a subject 2 feet away.

I then gave my friend the flash, along with an attached PocketWizard radio remote, and had him walk 150 feet into the scene. I also put a PocketWizard on my camera’s hot shoe and mounted the camera on a tripod. I set my aperture to f/8 and, while pointing my camera to the sky above the trees, took a meter reading and adjusted my shutter speed until 1/2 sec. indicated a correct exposure.

Nikon D300S, 12–24mm lens, f/8 for 1/2 sec., Speedlight SB-900

On a camping trip with my friend Charlie Borland, we decided to shoot a camp scene with wireless flash. He placed the flash inside the tent with the flash zoom manually set to a wide angle. This flash unit also had a wide-angle diffuser to spread the light around the tent. To keep the flash output consistent with each flash burst, he set the flash mode to Manual and the output to 1/4 power. This allowed an aperture of f/8. My strategy was then to shoot every single shot at f/8—giving the tent a consistent flash exposure—but bracket the shutter speed all over the place. This provided some darker and lighter ambient exposures of the mountain, people, and campfire, while the tent always had the same flash exposure. This particular shot had just the right mix of light and dark, with a well-exposed tent. Photo by Charlie Borland

Canon 20D, 70–200mm lens at 200mm, ISO 200, f/8 for 1/4 sec., Canon 580EXII

For years I enjoyed shooting a two-light setup with my two White Lightning Ultra 1200 studio strobes, placing each in a softbox—one on the floor, pointed up, and the other on a light stand, pointed down. Between these two softboxes would be a 4 × 4–foot sheet of 1/8-inch white Plexiglas on which I’d place numerous subjects, including flowers and fruit and vegetable slices. The first image is an example made this way. But as much as I enjoyed this setup, it did take up a large corner of a room, and it was expensive.

Then one day I stumbled upon the obvious. I lined the inside of a medium-size cardboard box with white poster board, replicating a softbox. I put one portable electronic flash inside the box, pointing it up. On top of the box, I placed a sheet of 1/8-inch white Plexiglas. And I mounted another portable flash on a light stand overhead about 2 feet above my subject. Doing this (second image, left), I was able to create a scaled-down version of my old larger setup with studio strobes and softboxes. Some kind of wireless device is key here to get the strobes to fire simultaneously. Due to the obstruction of the flash in the box, I’ve found a radio remote, such as a PocketWizard, to be most successful.

To start, set both flashes to the same output—full power. Also make sure that both flash distance scales indicate the same f-stop. F/16 is a good place to begin. Keep in mind that the flash in the cardboard box will be illuminating the subject through the 1/8-inch Plexiglas, so don’t place a diffuser or any other light-filtering device on the strobe going into the box, since the Plexiglas becomes the diffuser. However, do place a diffuser on your other flash so that its light output is also diffused. Next, call on a normal sync speed of 1/125 sec., 1/200 sec., or 1/250 sec.; that choice is yours. Then place a flower or other small subject on the Plexiglas, and shoot down on the setup.

Check your exposure. Your goal is a subject floating in white space while being well exposed from both front and back. Many subjects will appear to glow. This is due to the strong backlight of the strobe firing from inside the box. You may end up decreasing the power of one strobe to make it mesh more with the light output of the other. It’s easier to make any changes to the strobe outside the box (the one on the light stand).

For the mixed flower image (fourth image), I took apart a regular bouquet, arranged it on the Plexiglas, and set my aperture to f/11. The flowers appear to float, and the combination of backlight and frontlight creates great contrast. For the three tulips (third image, right), I used the same exposure settings. As you can see, the two different setups produce identical results.

All photos: 105mm lens, ISO 200, f/11 for 1/125 sec.

Throughout this book, there are numerous references to using the flash off camera and to the right of, to the left of, from below, or from above the subject. Unlike the sun, which follows a fairly predictable line across the sky as it moves toward sunset, your flash can be placed anywhere you need light. Yet—just like the sun—your flash emits “daylight.” And your flash can mimic all the varieties of sunlight: the hard light of midday, the soft light of an overcast day, or the warm front- or sidelight of an early-morning sunrise. Your flash can also provide backlight, silhouetting a subject in front of it or even looking like a sunset when placed behind a subject’s head and used with an amber gel.

I know of no better exercise that will help you immensely in understanding the daylight output of your flash—and its direction—than one that I always recommend to my students. If you can’t find someone to be your model, then use a simple vase of flowers on a table. From a distance of about 15 feet from your subject, and with a moderate telephoto lens such as an 85mm, set the aperture on your camera to f/16. With your flash in Manual mode, zoom the flash head to 85mm and set the ISO to 200. Now dial up f/16 on your flash and note the distance required for a correct flash exposure. Let’s assume that distance is around 12 feet (Note: It may or may not be, depending on the power of your flash.)

As you face the subject from 12 feet away, think of your position and the subject’s position as the hands of a clock. Your subject is at twelve o’clock and you’re standing at six o’clock. From the correct flash-to-subject distance, take your first picture with the flash at this six-o’clock position. This is a frontlit scene, meaning your subject is in frontlight. Keeping your camera in its place, if you move your flash to the nine-o’clock position and then the three-o’clock position (keeping that 12-foot flash-to-subject distance), you’ll have sidelit scenes, with the subject in sidelight. Finally, if you move just the flash to the twelve-o’clock position (12 feet behind the subject), you’ll have a backlit scene, since the subject will be in backlight.

Study your resulting photographs and you’ll quickly notice a difference in the lighting. Make a note of what you like and don’t like about the light’s effect on the subject in each of these four exposures. As you begin to experiment more with flash and become familiar with how light falls across a given scene or subject based on your flash placement, you’ll soon be making mental images of the scenes before you without having to even set up the shot. Knowing your flash, the power of its output, and how it looks from different angles will not only save you precious time when setting up shots but will increase your odds of pulling off some magical and very creative images. The only limitations are those of your imagination.

While in a neighborhood of Tucson, I came upon a home with a gated entry that was, I’m sure, meant to be a piece of art. Assembled from a number of metal pieces—all varying in size, shape, and texture—it could easily be photographed to showcase the effects of light on a subject. Focusing on just a portion of the gate, I set up with my camera mounted on a tripod and shot four different manual flash exposures: one pointing the flash down from above (first image, top), one pointing it up from below (second image, bottom), one with it on the right of the subject (third image, top), and one with it on the left of the subject (fourth image, bottom). Although I never once changed my camera position, it is evident that each exposure is unique. That uniqueness has everything to do with the light and its direction.

All photos: Nikon D300S, 12–24mm lens at 24mm, ISO 200, 1/40 sec. at f/22, Speedlight SB-900

Moving beyond a simple metal gate, try your hand at various lighting angles with a human subject. It’s a truly revealing exercise in how the direction of the light has a tremendous impact on the emotional appeal and message of the image.

In my first example (top, left) of a young Indian woman, the exposure is just of the ambient light. I positioned her under an overhang against a fabric-covered wall. The soft ambient light allowed me to record a simple yet pleasing portrait at f/8 for 1/60 sec. Now compare this with the next three images I made, which were all shot at the same exposure of f/8 for 1/250 sec. with flash. (I chose 1/250 sec. because I wanted to kill the ambient exposure, and after powering down the flash to 1/16 power, I found I could use f/8 at a flash-to-subject distance of 4 feet.) The only difference among them is the position of the flash and the direction of its light.

I had one of my workshop students hold the flash for me and set the camera to Commander mode for remote flash firing. I then had the student hold the flash in the twelve-o’clock position (top, right), the three-o’clock position (bottom, left), and the six-o’clock position (bottom, right). The overall feel and mood of each shot is quite different, and this diversity is owed 100 percent to the position of the flash. Get in the habit of moving that flash around the subject, and you’ll soon be making a host of discoveries about light and its emotional impact in a photograph!

All photos: 70–300mm lens. Bottom, left: f/8 for 1/60 sec. Top, right and bottom images: f/8 for 1/250 sec., Speedlight SB-900

In my never-ending quest for letters, I now find myself calling on flash when I come upon raised letters, as I did during this outing in downtown Chicago. It was an overcast day, and I wanted to shoot in low-angled sunlight. No problem. This letter T was soon basking in warm sidelight thanks to a low-angled flash with an amber gel. Also, I didn’t want the normally hard light of a low-angled sun, so I shot the flash through my circular cloth diffuser, as you can see at left. The result has depth and shadow—exactly like sunlight in the late afternoon.

Nikon D300S, 105mm lens, ISO 200, 1/250 sec. at f/16, Speedlight SB-900

Creating appealing sidelight was just as easy as asking my friend Yousif to pose among this long row of columns. With a single amber-gelled flash unit mounted on a small light stand and placed about 10 feet off to the right of the columns, I was able to create the illusion that Yousif was bathed in low-angled sunlight—even though it was a cloudy day.

Nikon D300, 70–300mm lens at 300mm, f/11 for 1/60 sec., Speedlight SB-900

My students and I were hanging out near Arab Street in Singapore when this pretty young woman came our way. When she agreed to be photographed, we quickly set up a black cloth behind her (first image) to create a clean, black background. I then captured the first image (second image) under the available light of the overcast sky. It’s a nice shot, but I was in the mood for some low-angled sunlight and that really warm glow you often see streaming into your house through a window in late afternoon. And despite the overcast sky and the fact that we were outside, I knew I could create this look with my portable electric flash, a plastic chair, an amber gel, and the help of my students.

As the next image (third image) shows, I got my subject appearing as if bathed in a single ray of warm afternoon light while looking “out the window.” How did I accomplish this? I asked one student to hold the chair and the strobe, placing the strobe up and near the open slats of the chair back (first image). This essentially feathered the light, narrowing its angle of view via the slats in the chair. Only a portion of the light from the flash got through to the subject—just enough to create the warm ray of light you see here falling on her face.

With the camera in Manual exposure mode and the flash set to TTL, I simply aimed, focused, and fired. Since I shot this image in TTL and since the flash was off camera, I used Nikon’s Commander mode to fire the flash. With my Nikon D300 camera, the pop-up flash became a transmitter, sending a signal to my flash to fire when the shutter was released.

Third image: Nikon D300, 24–85mm lens at 85mm, ISO 200, f/8 for 1/200 sec., Speedlight SB-900

You’ve already seen several examples in this book in which I turned the normally white light of the flash into light that was much warmer—light akin to the warm, golden glow of the low-angled sunlight found in early morning or late afternoon. In those situations, I was able to make the light much warmer with the use of an amber-colored gel placed directly in front of the flash head. Using gels with electronic flash is akin to using colored filters when shooting available light: You wish to add color to, or subtract color from, the light in the scene.

The amber gel I use is actually intended for indoor use where incandescent or tungsten light abounds. Typically, you would use this gel with your white balance set to Incandescent/Tungsten. With the gel attached to the front of your flash, the color temperature of the light being emitted by the flash becomes the same temperature as the Incandescent/Tungsten lights in the room. As you fire away, everyone and everything is bathed in the same color light: a somewhat-cool white.

Likewise, when you place the light-green gel that comes with the Nikon Speedlight SB-900 over the flash head and change your white balance to Fluorescent, you can expect to get nice, white-light pictures in an office setting, where fluorescent lighting is often found. The green gel converts the flash to the same color temperature as fluorescent lights, and when you then combine this color temperature with a Fluorescent white balance setting, you’ll eliminate the normal, sickly green cast that sometimes permeates the scene in office photographs.

A purple gel is all it took to turn a somewhat distracting foreground into a foreground with impact! Near the Marina Hotel and Casino in Singapore, a very interesting pedestrian bridge crosses the bay in the downtown area. The bridge’s chrome structure affords photographers the opportunity to use elements of the structure to frame the distant skyline, but when shot at dusk (top), these parts of the bridge are often “dusted” with a smattering of streaks from reflected traffic lights—pretty bland and also anything but uniform in both color and contrast. By fully illuminating the bridge elements with a flash and purple gel, I was able to call greater attention to the foreground element and get it to stand out in marked contrast to the distant skyline.

Both photos: 16–35mm lens, ISO 200, f/11 for 3 seconds. Bottom: with Speedlight SB-900 with purple gel

Using colored gels, at least initially, is fun, and they do have their place. But as I’ve learned, gel use falls into that category of less is more. Yes, I often use the amber gel, but I seldom use any other, and believe me, it’s not because there’s a shortage of colored gels—heck, you can find gel packs that offer more than 250 colors! Can you imagine having 250 colored filters for your lenses? Neither can I, which raises the question, Why do you need 250 colored gels for your flash? You don’t.

But assuming you want a few gels, the good news is they’re easy to acquire. For example, my good friends at Adorama Camera sell the Rosco Color Effects Kit, which comes complete with fifteen different 10 × 12–inch colored gels, including the amber gel. The beauty of this kit is that you can then simply cut a custom size to fit your flash from the 10 × 12–inch gel sheet, and you still have plenty of extra left, which is a good thing, since I guarantee you’ll lose that first one at some point in your flash photography journey.

The gels in this kit are so large because they’re intended for studio photographers who use electronic flashes that are much larger and much more powerful than portable electronic flash units. The silver reflectors that often fit over these studio strobes require the bigger gel. But on the other end of the spectrum, if you’re shooting with the built-in pop-up flash on your camera, you can easily wrap a sliver of a gel in front of that itsy-bitsy, teeny-weeny flash and attach it with a small rubber band. Just make sure the rubber band is wrapped around the gel and below the flash head itself so that the rubber band doesn’t cover any part of the flash head.

Those who just want one gel can buy a single gel sheet in any color. The amber gel, in particular, is popular because it does a great job of warming up any given subject. Better yet, with that one gel you can keep your relatives away during the holidays! Seriously. Tell them that you’re taking the family to Hawaii for the holidays, when in fact you’ll be staying at home. Then sometime during that enjoyable, quiet holiday week, gather up your family and shoot a few waist-high portraits with your flash and an amber gel (make sure everyone wears T-shirts or beach attire). If you really want to make the shots extra believable, have the kids wet their hair in the shower and rub some soap in their eyes. The wet hair and red eyes, combined with the amber gel–induced tan, will make them look like they’ve been in a chlorinated pool all day! A few days later, after you get back from “Hawaii,” e-mail your relatives a few of these shots. I am absolutely certain that they will comment on how tan everyone is!

There are also a variety of other light modifiers that can help you shape and filter the light from your flash. Diffusers are popular and useful tools for softening the light of your flash. These simple panels go in front of the flash head to spread out the flash light so that it’s more dispersed and less concentrated. The effect is a less harsh light on your subject. Like gels, diffusers cause a loss of flash output, usually about 1 stop in my setups.

Unlike a diffuser, which both softens and spreads the light, a snoot considerably narrows the spread of the light. If you don’t want to spill any gasoline on your sidewalk as you fill up the lawnmower with gas, you probably use a funnel. A snoot works in much the same way in that it funnels the light down toward the narrow opening at the end of the snoot. Your flash head attaches to the snoot, and when the flash and snoot are placed close to a given subject, a narrow circular spot of light is seen on the subject you’re lighting.

When we pulled into the parking lot next to a beach outside Tampa Bay, I commented to one of my students that we should return after dark and shoot one of the many parking meters with our flash. Based on his expression, it was clear that he was not looking forward to that outing. What’s so interesting about a rusty old parking meter at night? he asked.

It was a fair question, but one I didn’t answer, choosing instead to simply say, Trust me, you’ll be glad you did when the night is over. Returning at night, I took one flash and attached a snoot. This became the foreground flash, which I aimed at the parking meter. I was able to zoom in the flash, narrowing the angle of the flash beam considerably so that only a portion of the parking meter was fully illuminated. In the background, my assistant reached over our “expired” model with his outstretched arm holding another flash unit. Based on the flash-to-subject distance, this flash required an aperture of f/8 for a proper exposure. I then powered down the foreground flash so that its required aperture was the same as the background flash (f/8).

Simple enough, and now all that remained was to mount my camera and lens on a tripod and set the lens to f/8. Since there was no ambient light to speak of, the shutter speed was irrelevant (because, remember, shutter speed controls ambient-light exposure). However, since I wanted an exacting composition, leaving no margin for any minor shift in point of view that sometimes happens when handholding the camera, I chose to use the tripod.

Nikon D300, 35-70mm lens at 35mm, ISO 200, f/8 for 1/125 sec., Speedlight SB-900

Turning day into night is now possible—and easy—thanks to the powerful combination of flash and ambient light. With this setup, it was my intention to create a composition that suggested fear. What could be more fearful than knowing it’s late at night and you’re being followed as you leave the local bar? In an effort to run, you stumble across the sidewalk and your purse goes flying. How did I create a picture like this in broad daylight? With flash, a blue gel, and the deliberate and severe underexposure of the ambient light, that’s how!

I set up this scene against an east-facing wall at around 3:00 PM, so the sun was directly behind the building and fully blocked from view. With my main model in place—kneeling on the sidewalk and with items from her purse scattered about (first image)—the shot required two flashes, both used wirelessly attached to PocketWizards. One flash was held over the model’s head and gelled with a blue gel, to replicate a blue neon sign that a club or bar might have outside its entrance. The second was ungelled and held behind a male model (on the far right of the setup shot in the second image) as he assumed the pose of an attacker.

Since the flashes were at different distances from their respective subjects, I needed to power down the flash near the woman so that its output would equal that of the more distant strobe behind the man. Based on their respective flash-to-subject distances, both of my flashes were set to create a correct exposure at an aperture of f/16. At f/16, the correct ambient-light exposure was 1/15 sec. However, it was my intention to turn day into night, so with my shutter speed set to 1/250 sec., my ambient light would record as a 4-stop underexposure. This is pretty darn dark, and as you can see in the third image, the resulting image did, in fact, transform day into night.

Third image: Nikon D300S, 12–24mm lens at 20mm, ISO 200, f/16 for 1/250 sec., two Speedlight SB-900s

Following a very early start and several hours of shooting lavender fields in Provence, my students and I took a coffee break in the small town of Puimoisson. Everyone was thrilled to finally get their morning cup of joe, including one of my students, Dennis. As I was sitting at the other end of the bar with several other students, I was quick to notice the extreme contrast in the rather dark café and the much brighter street behind Dennis. I then explained to several of my students just how easy it is to combine the available light exposure of the outside street with portable “sunlight” that we could create.

Since I wanted some detail of the street outside and beyond Dennis, I used f/16. I decided that the flash would essentially frontlight Dennis and also chose to fire the flash through a small diffuser that would spread, as well as soften, the flash’s light (first image). Then I set my flash to f/16 and noted the corresponding flash-to-subject distance of 9 feet for a correct exposure. But experience has taught me that when shooting my flash through a diffuser I lose about 1 stop. To compensate, I cut the flash-to-subject distance almost in half. As you can see in the setup photo, the flash is about 5 feet from Dennis.

With my lens aperture set to f/16, I took a meter reading of the available light out on the street by simply pointing my camera and lens at the large, bright window at the end of the bar. The meter indicated 1/160 sec. for a correct exposure at my chosen aperture. At 1/160 sec. without the flash, Dennis would have recorded as a silhouette, but when I added flash, with my lens set to f/16 and my shutter speed still at 1/160 sec., I was able to render a pleasing portrait of him enjoying his cup of joe.

70–300mm lens, f/16 for 1/160 sec., Speedlight SB-900

When we reached this mosque, one of my students thought it would be a good idea to compose the scene with flowers in the foreground and using a wide-angle lens for a composition of great depth and perspective. All he had to do, he said, was wait for the sun to come up a little higher behind him so that the flowers and mosque would both be lit by the early-morning light. I loved the idea of incorporating the foreground flowers into the composition. But I was quick to tell him that if he waited for the sun to light the flowers, he’d be fighting his own shadow in that part of the composition. I suggested that he’d actually be much better off using his flash at that moment—before the sun got any higher on the horizon.

The first image shows the scene as it was at that moment: recorded without flash, the foreground flowers not yet lit by the early-morning sun. But with our miniature sun, the flash, we could make my student’s vision happen. Since we needed great depth of field, f/22 was appropriate. Set at f/22, the flash indicated a flash-to-subject distance of 5.4 feet for a correct exposure. But that assumed we’d be shooting the flash “naked,” without any gels or diffusers in front of it. In fact, we were planning to use a small diffuser on the flash to soften the light. With a diffuser, the flash’s power is reduced by about 1 full stop, so we needed to place the flash closer to the subject (about half as close as what the distance indicator told us). In the situation, that meant holding the flash about 3 feet from the flowers.

Looking through the camera, I could see that, at f/22, the light meter indicated a correct exposure of 1/60 sec. for the early-morning light reflecting off the mosque. So as long as we kept the flash at a distance of about 3 feet from the flowers, the flash exposure and the natural-light exposure of the rest of the scene would both be correct—and the same exposure in terms of quantitative value. So holding the flash overhead, about 3 feet from the flowers and pointed downward at a 45-degree angle, we fired away. The miniature sun did a nice job of illuminating the flowers without any worries of our shadows falling into the scene. Sure enough, about two minutes later the real sun rose behind us, just high enough to light up the flowers, and try as we might, we could not get the shot without casting our shadows all over the flowers.

Both photos: Nikon D300, 12–24mm lens at 12mm, ISO 200, f/22 for 1/60 sec. Bottom: with Speedlight SB-900

I asked my model, Tyler, to stand against a south-facing wall in Tampa. My assistant, Dave, then helped me transform Tyler into a dark, mysterious character, with only the aid of a flash and a single snoot. Standing back from Tyler at a distance of about 20 feet and handholding my camera and 70–300mm lens, I zoomed in to 300mm, filling my frame up nicely with Tyler’s face. As you can see in the first image, Dave is right up on Tyler, holding the flash and a snoot covered with an amber gel about 8 inches away from his face. Due to this very close flash-to-subject distance, I powered down the flash considerably. When I reached 1/64 power, the flash’s distance indicator said I could shoot at my chosen aperture of f/11 from 1 foot away. But Dave was closer even than that. Still, since I was using an amber gel, which absorbs about a stop of light output, I stayed at 1/64 power.

All that remained was to set an exposure for the available light. With my lens set to f/11, I merely adjusted my shutter speed until 1/60 sec. indicated a 1-stop underexposure for Tyler’s face. Why a 1-stop underexposure? Because I wanted the light from the snoot to be center stage, and underexposing his face by 1 stop would do just that.

Third image: 70–300mm lens at 300mm, f/11 for 1/60 sec., Speedlight SB-900

Peter Kastner, the Bass “Meister” from Austria (bottom), got his first taste of rock stardom at age sixteen. Austria quickly proved to be too small for this talented musician, and it was soon “America or Bust.” Peter is truly a guy in love with music and, of course, his bass guitar. After stumbling into an alleyway just off Venice Beach, I remarked that the red wall and gargoyle figure would make a perfect backdrop for a portrait of Peter. While he went to get his guitar from his nearby car, I asked Randy Ray Mitchell (guitarist for Donna Summer, among others) to stand in for him so that I could set up the lighting and make some test shots (top).

As you can see, I used two lights. The rear strobe is off camera left and pointed at the wall and the gargoyle. The front light is off camera right and pointed somewhat straight at the subject. I placed diffusers over both strobes and also used light amber gels. Since I wanted the wall and gargoyle to remain somewhat “soft” while Peter was in sharp focus, I chose an aperture of f/5.6. I then dialed f/5.6 into the near flash and found that, at my 4-foot flash-to-subject distance, I’d need to power down the flash to 1/32 power. For the 5-foot flash-to-subject distance of the rear strobe, I found that 1/16 power was called for. So, with my aperture at f/5.6, I took a meter reading of the overall ambient light and got a correct shutter speed of 1/15 sec. Since I wanted to create a bit of mood in the scene, I underexposed my ambient exposure by about 1 1/3 stops (f/5.6 for 1/40 sec.). As you can see, the parts of the wall that are not lit by the flash give a somewhat moody feel to the overall exposure. And yes, Peter is indeed licking his guitar. Like I said, this guy loves his bass!

f/5.6 for 1/40 sec., two Speedlight SB-900s

One of the most common uses of flash is to capture onstage performances, which frequently have energy-filled, low-light subjects. This might have been a challenge before, but now that you’re armed and dangerous with the knowledge of electronic flash, you’ll feel like you can do almost anything. (You may even start running ads on Craigslist: Rock Band Photographer for Hire.) Whether you’re shooting an indoor performance or wish to take the band outside, there isn’t a lighting situation you can’t handle. And just think of the many creative doors that are now yours to open! There has never been a great scientific breakthrough without preliminary experimenting, and the same is true with electronic flash technique—so get out there and take some chances! Every experiment that doesn’t work moves you a step closer to the ones that do.

Note that in situations like the ones shown on these few pages, I sometimes work with one flash, sometimes two. Sometimes with gels, sometimes without. And almost always with my trusty PocketWizards, since I am a strong advocate of keeping the flash off the camera’s hot shoe. And of course, 98 percent of the time, I’m shooting in Manual flash exposure mode.

Combining a low viewpoint, two flashes, and a bit of intentional camera movement enabled me to capture Butch Norton (drummer extraordinaire for the Eels and Tracey Chapman, among others) in a high-energy pose. Placing one flash behind Butch and another about 2 feet to my right caused Butch’s shadow to fall toward me while also illuminating the front of him.

Depth of field was not a huge issue here, so I went with f/11. When I input f/11 into both strobes, I saw that I’d need a flash-to-subject distance of 13 feet. So both strobes were on small stands at 13 feet: one 13 feet behind, the other 13 feet in front (and 2 feet to my right). I took an ambient reading off the traffic lights and nearby storefronts and found that a 2-second exposure at f/11 would be correct. Since the only light falling on Butch would be from my two flashes, I didn’t set the shutter speed to a 1-stop underexposure; this allowed the ambient light around Butch to fully expose on the digital sensor. And finally, when I pressed the shutter release, I jiggled the camera a bit, knowing this would result in an artistic “painted” look. Since Butch wasn’t lit by any ambient light, the exposure for him was 100 percent dependent on the flash. The flashes were set to rear-curtain sync, I jiggled the camera a bit, and just before the 1-second exposure was finished, the flashes fired, freezing Butch in the pose you see here.

Nikon D300S, 24–85mm lens, ISO 200, f/11 for 1 second

When I made this shot, I had been recently hired to photograph WaldoBliss (also seen on this page). After flying out to Los Angeles, I met the band members and within an hour was shooting their performance at a local coffee shop in San Pedro. Although not a critical performance for the band’s photograph needs, it provided a great excuse to try some lighting tricks.

Here, singer, songwriter, and guitar player Dan Carlson belts out a tune. The low light level allowed me to try zooming my lens during the necessary slow shutter speed, and with my flash set for rear-curtain sync, the flash fired at the end of the zoomed ambient exposure. To set this up, I had my flash on a light stand about 10 feet from Dan, and for this flash-to-subject distance, the flash distance scale indicated f/11 as the correct aperture. At that point, I metered the ambient light in the room, and at f/11, the meter indicated 1 second as the correct exposure. However, since I would be combining flash and ambient light, I chose to shoot the ambient light at 1/2 sec., in effect underexposing the ambient light by 1 stop. I then handheld the camera, pressed the shutter release, and zoomed my lens from wide to telephoto, and at the end of this 1/2-sec. exposure, the flash fired—and a high-energy zoomed portrait of Dan is the result.

Nikon D300S, 24–85mm lens, ISO 200, f/11 for 1/2 sec., Speedlight SB-900

One doesn’t have to be familiar with art to be familiar with shadows. Take an early morning walk on a sunshine-filled day and, with the sun at your back, you’ll see your shadow, long and lengthy, falling before you. Shadows are commonly referred to in literary works, where they are often used as metaphors. Walt Whitman is noted for observing that you should keep your face always toward the sunshine so that the shadows will fall behind you. A common French proverb equates the shadow to a man’s reputation: It sometimes follows and sometimes precedes him, it is sometimes longer and sometimes shorter than his physical stature. But it was Conrad Hall, a three-time Academy Award–winning cinematographer, who said it best: “Manipulating shadows and tonality is like writing music or a poem.”

Shadows do change the melody of the photographic song, and other than the sun itself, nothing else but the electronic flash comes as close when it comes to creating shadows and readily changing the melody of your own photographic songs. I can recall numerous times when I found myself relying solely on Mother Nature to produce the desired light and looking up to the sky, my thoughts quickly turning grim as I faced the reality that there would be no sunlight coming my way anytime soon. Not anymore! My pockets are filled with portable sunlight!

Shadows impart that often-pivotal three-dimensionality; without shadows, we have neither texture nor form, and without form we have no volume. In the absence of textures, there is the absence of any substantial feelings. Study shadows in the natural world and soon you’ll discover that low-angled light produces long shadows and sidelight emphasizes texture and form. Make a point of creating shadows with your flash simply by placing objects in front of your flash (see this page as an example).

Some objects throw a better shadow the closer they are to the flash, while others do a better job when placed farther from the flash. Since there are no film costs in the age of digital photography, trial and error is no longer a luxury but the norm! And because you have your own electronic flash, you are the sunshine, so get out there and start creating shadows that can precede or follow you no matter where your travels take you.

A blue wall and a wrought-iron window gate—what more can you ask for? Well, I asked Randy Ray Mitchell to stand against this blue wall in the corner where the window gate and wall met. Peter, seen on this page, helped me with the flash; with his long arms, he was able to extend the flash beyond the gate just enough so that when I fired the flash I would record some wonderful shadows on the blue wall as well as some warm sidelight on both the subject and gate. The effect was that of an early-morning sunrise.

To make the exposure, I had already determined that Peter would be holding the flash at about 8 to 9 feet from where my subject would be standing with his guitar, so I simply adjusted the dial on the back of my flash until I hit 9 feet and noted that the suggested aperture was f/11. With my camera now set to f/11, I took a meter reading of the ambient light and got 1/30 sec. for a correct exposure. But since I was combining ambient light with flash, I chose to underexpose the ambient light by 1 stop (1/60 sec.), as I felt the colors of the wall in particular would be a bit more vivid if underexposed. I fired a dozen or so pictures, and this is one of my favorites.

Nikon D300S, 24–85mm lens, ISO 200, f/11 for 1/60 sec.

“What if” is a philosophy that travels with me 24-7, and it was on a small and very quiet street in Tucson that I put “what if” to work once more. Turning to my workshop students, I asked, What if we pretend this vacant house is being lit by low-angled sunlight instead of the overcast north-facing light we see here? With a single flash Nikon Speedlight SB-900, an amber gel, and the help of my VAL, Frank Carrol, the once ho-hum, flat, lifeless house is awakened by the light!

Over the course of the next thirty minutes, my students and I shot many variations of this blue wall and red door, making certain we were firing the flash into and through the many plants and bushes that grew in front of this house—to create the most interesting cast shadows.

Like so many other flash exposures, this one, too, was really quite simple. There weren’t any depth concerns, so f/11 was the aperture choice. I dialed this into the aperture wheel on the back of my flash and found that at 1/1 power and with the flash head set to 28mm, the flash-to-subject distance needed to be 12 feet. But since the amber gel I was using would cause about a 1/2-stop of light loss, I knew I needed to come in closer to about 8 feet to maintain a correct flash exposure. As you can see in the setup shot, Frank is about 8 feet from the blue wall and doorway. He’s also holding the flash, which means I was firing the flash remotely (in this case, using a PocketWizard on the camera’s hot shoe that communicates with and fires the flash whenever I press the shutter release).

Nikon D300S, 12–24mm lens at 13mm, ISO 200, f/8 for 1/125 sec.