CHAPTER 3

Pharmacology

Introduction

Medications are at the center of keeping patients safe and comfortable during surgery. They are used to render a patient unconscious and insensate to pain or surgical stimulus. In achieving this goal, however, we inhibit or alter many basic, life-sustaining processes that the body normally has very tight control over. These include maintaining adequate blood pressure, heart rate, and continuous breathing. Anesthesia providers then need another collection of medications to fix the problems that the “anesthetizing” drugs cause. Now, add to that, surgeons are invading the body in an effort to correct the underlying problem, be that a broken bone, ruptured gallbladder, cancerous liver, or other illness. To facilitate the patient’s surgery, we use medications like antianxiety drugs, muscle relaxants, antibiotics, pain medications, and antinausea drugs. Adding yet another layer of complexity is the fact that many patients undergoing surgery have chronic medical conditions, which require chronic medications. Medical conditions often alter how certain medications affect a patient; some conditions are absolute contraindications to receiving certain drugs. All types of people—men and women, young and old, healthy and infirmed—are in need of some type of surgery on a regular basis. Anesthesia providers use not only the anesthetic drugs that will render a patient unconscious but also the other drugs needed before, during, and after surgery to support normal organ system functioning and reduce complications, and then, also, to maintain the chronic disease conditions by which many patients are affected. It is important to understand how these medications work in the body and how the body processes and removes them. Pharmacology is the study of drugs: their uses, intended effects, side effects, mechanisms of action, and mechanisms of clearance.

Safety

Institutional policy will vary as to whether anesthesia technicians and technologists are permitted to administer drugs under the direction of anesthesia providers. Those institutions that do allow it will have very clearly defined situations when it is permissible. You should always be familiar with your institution’s policies; patient safety has the highest priority, but we don’t want anyone getting in trouble either. Even if not directly administering drugs, most anesthesia technicians are assisting with this by bringing medications to anesthetizing locations, setting up pumps, and understanding disposal of medications. It is crucial to verify, before any administration, that one has the correct drug, the correct dose and concentration, and the correct route. Good communication is essential when more than one person is involved in giving a drug. Errors in drug administration are among the most common preventable errors in health care and can be lethal; any member of the health care team can speak up to help prevent one.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetics is the study of how the body affects a drug, from the time it enters the body until it is removed. For a drug to have an effect, it must first get into the body, make its way to the site of action, exert change by interacting with its receptor or other target molecules, and then eventually get broken down and removed from the body. There are many steps in this process: absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination.

Absorption

Most drugs get to their site of action by way of the bloodstream. Absorption refers to the process of getting the drug into the bloodstream. How easily or quickly this happens is dependent on the route of administration of the drug. While there are many routes (Table 3.1), the vast majority of anesthetic drugs are given directly into the bloodstream (intravenously [IV]), which bypasses the step of absorption. Less common routes are oral (known as PO, for the Latin “per os”), inhalational, subcutaneous injection, and transdermal. Once in the bloodstream, drugs get to their targets quickly, so the process of absorption typically has the greatest influence on a drug’s onset time (the time from administration to taking effect).

Table 3.1. Routes of Drug Administration, their Abbreviations, and Examples of Common Anesthetic Medications Given by each Route

Some routes have no standard abbreviation.

aWorks at the site of delivery.

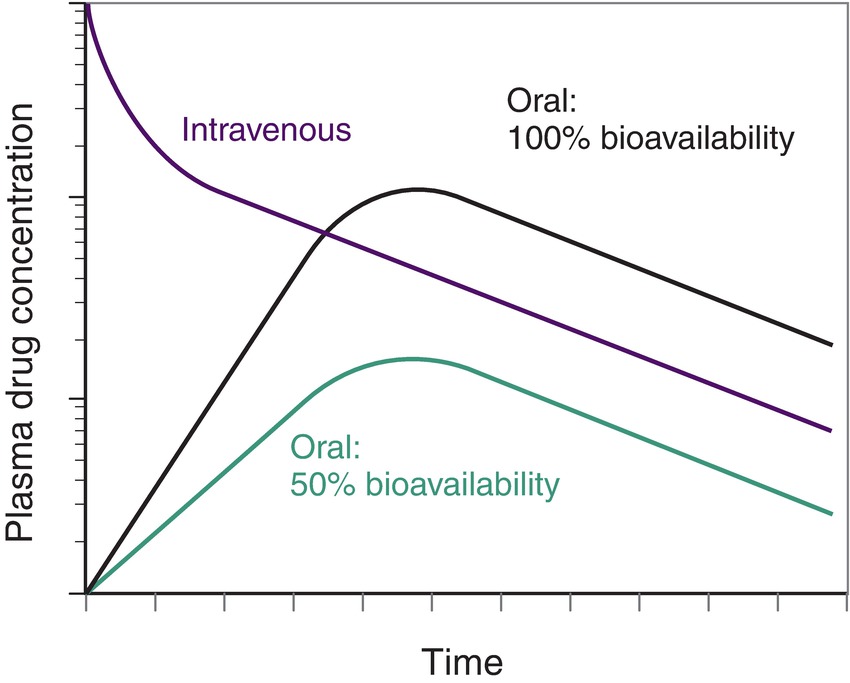

Absorption of drugs given orally has many more steps and takes much longer. A pill is swallowed and ends up in the stomach, where it dissolves and moves on to the small intestine. There, the drug molecules are absorbed into the cells of the lining and then into the bloodstream. How long all this takes is variable. Some pills dissolve more slowly than others. Impaired gastric motility can prolong the process because it takes longer for stomach contents to get to the intestine. Intestinal absorption can also take longer in some patients (Fig. 3.1). Typically, drugs given orally won’t take effect for 30-60 minutes.

FIGURE 3.1. Bioavailability after administration of a single dose of drug. Drugs that are slowly absorbed into the bloodstream from other compartments (transdermal, epidural, intramuscular, subcutaneous) have a similar curve to oral drugs; each route has a slightly different rate based on the blood supply to the tissue.

Transdermal is another slow route of drug delivery. A scopolamine patch (anticholinergic, used to prevent post-op nausea) must be applied to the skin at least 2 hours before the end of surgery to have an effect. Transdermal drugs must diffuse through the skin (which is designed to be a barrier between the body and the outside environment) and subcutaneous layers before they enter the bloodstream. Other transdermal drugs, like lidocaine, exert their effects directly underneath the patch. Lidocaine (a local anesthetic that inhibits nerve conduction by blocking sodium channels) is absorbed through the skin and subcutaneous layers and then inhibits the nerves right there from conducting sensory signals (pain).

When drugs are delivered by injection, the process of absorption is a little different, but the concepts are the same. Nerve blocks, for postoperative pain, entail the injection of local anesthetics around nerve bundles to temporarily prevent the nerves from transmitting pain signals (the area or body part becomes numb as a result). These drugs are injected very close to the nerves on which they will act, and they diffuse across tissue layers until they are taken up by the nerves they are targeting. They also diffuse into the bloodstream, which is how the nerve block wears off. In small doses, local anesthetics have no effect in the bloodstream, but at large doses, they can be toxic. Doses that would be toxic if injected into the bloodstream are often used for nerve blocks, so great care must be taken to prevent intravascular injection. Drugs can also be injected into the epidural space or thecal space (also called the subarachnoid space), which is the fluid that directly surrounds the spinal cord (see Chapter 16, Regional Anesthesia). In all these examples, the drugs are injected near their targets, and they are absorbed into the surrounding tissues and bloodstream.

Bioavailability

The amount or dose of a drug always has to be adjusted according to the route by which it is administered. An oral dose of metoprolol (a beta-blocker used for hypertension or heart disease) is 25-100 mg, but when this same drug is given intravenously, a typical dose is only 2-5 mg. The reason for this large disparity has to do with the differing percentages of dose that actually get into the bloodstream, depending on the route given. Oral doses are so high because a large percentage of the drug is lost. Not only does oral absorption take a long time but it is also inefficient, as drug may be lost at many steps along the pathway through the digestive system. Some of the drug is broken down and degraded by stomach acid. Drug that survives stomach acid may not be absorbed but eliminated in feces. The intestines have their own vascular system called the “portal circulation” draining directly to the liver, which efficiently processes food, toxins, and chemicals. When an oral drug is absorbed, it is taken straight to the liver where a portion of it may be metabolized or inactivated. This process of drug removal by the liver just after absorption is called first-pass metabolism; the percentage lost is variable, depending on the drug and health of the liver. Once past the liver, the drug goes to the heart, systemic circulation, and on to its final target site. The bioavailability of a drug is the percentage of the original dose that is circulated and active in the body. If 70% of the dose ingested is broken down or not absorbed, then only 30% ends up in the systemic circulation; that drug has a bioavailability of 30%. It varies with different drugs, doses, other gastric contents, and certain disease states that affect intestinal absorption. Hydromorphone and methadone are both opioids used to treat pain. Hydromorphone has oral bioavailability of about 20%, so when converting from IV to oral routes, the dose is multiplied by 5. Methadone, however, has an oral bioavailability near 100%, so when converting between oral and IV dosing, there is minimal change in the dose.

Many drugs can be given by multiple routes; both dosing and the time of onset are usually different. The right dose of the right drug must be given by the right route. It might seem difficult to give a drug by the wrong route. However, the injection ports (Luer lock and slip tip) for IV catheters are identical for epidural and nerve block catheters, and the intrathecal space can be mistaken for the epidural space, potentially causing paralysis, loss of consciousness, seizures, or even death. Local anesthetics meant for the epidural or perineural space can be injected intravenously, causing CNS and potentially fatal cardiac toxicity (see Chapter 63, Local Anesthetic Toxicity).

Distribution/Redistribution

As already stated, once a drug reaches the blood, it must be carried, or distributed, to its site of action. This process is not as simple as the drug being taken directly from point A to point B. Once a bolus of drug is given into the vein, the drug will travel within the venous system back to the right heart, through the lungs, into the left heart, and eventually into the arterial system to the rest of the body. During this time, the drug will become diluted to an initial or peak concentration, which depends on the dose given and the patient’s total volume of blood. At the level of the capillaries, the drug will diffuse out of the blood (where it is in high concentration) and into other tissues and organs (where the initial drug concentration is zero). This is the process of distribution—the movement of a drug from the blood (or compartment with high concentration) into other body tissues.

Blood flow is not equal to all tissues. Those that need the most energy (brain, heart, kidneys, liver) get a disproportionately large fraction of blood flow relative to their sizes. These organs are collectively known as the vessel-rich group. These organs get the most blood flow, so they get the largest amount of whatever the blood is carrying, including drugs. Tissues that get a moderate amount of blood (muscles) get a smaller amount of drug, and those tissues that get the least amount of blood flow are known as the vessel-poor group (fat, cartilage, skin). The vessel density of tissues is what dictates the initial distribution of drugs.

But then redistribution kicks in, producing equilibrium and again altering the concentration of drug in the blood. As a drug diffuses out of the blood compartment into the muscle and vessel-poor compartments, the drug concentration in blood drops below that of the vessel-rich group. Now, the direction of diffusion reverses, and the drug diffuses out of the vessel-rich group into the blood, and drug continues to move into the muscle and vessel-poor groups. Redistribution (Fig. 3.2) is the net movement of drug out of the vessel-rich group and into the muscle- and vessel-poor groups by way of passive diffusion. This process accounts for the duration of effect (or “wearing off”) of certain drugs, like propofol (induction agent, sedative). Initially, propofol will be distributed quickly to the brain. There, the concentration will rise sharply, and the patient will lose consciousness. If no additional propofol is given, the level of propofol in the blood will drop as it moves to the muscles and fat, causing redistribution of propofol from the brain back into the blood. The level in the brain will drop and the patient will regain consciousness. This happens before any of the drug has been metabolized or removed from the bloodstream by the kidneys.

FIGURE 3.2. Distribution of a bolus of intravenous anesthetic. When a bolus of intravenous anesthetic is administered, it is initially transported through the vascular system to the heart and then distributed to the tissues. The vessel-rich group (VRG) receives the highest percentage of the cardiac output; its anesthetic concentration rises rapidly, reaching a peak within 1 minute. Redistribution of anesthetic to the muscle then quickly decreases the anesthetic level in the VRG. Because of very low fat perfusion, redistribution from muscle to fat does not occur until much later. Note that rapid redistribution from the VRG to muscle does not occur if the muscle has previously approached saturation through prolonged administration of anesthetic (not shown); this can lead to significant toxicity if intravenous barbiturates are administered continuously for long periods of time. Newer agents, such as propofol, are designed to be eliminated by rapid metabolism and, therefore, can be used safely for longer periods of time. (From Katzung, BG, Trevor AJ. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 14th ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2018, with permission.)

The process of drug movement from one compartment to another will continue to approach a state of equilibrium which is when there ceases to be diffusion gradients between compartments, and net movement between them stops. The amount that ends up in each compartment is a function of the relative size of that compartment (all the muscles in the body have more mass than the thyroid gland and so can hold more drug) as well as the relative solubility of drug in each tissue type (more on this later).

Volume of Distribution

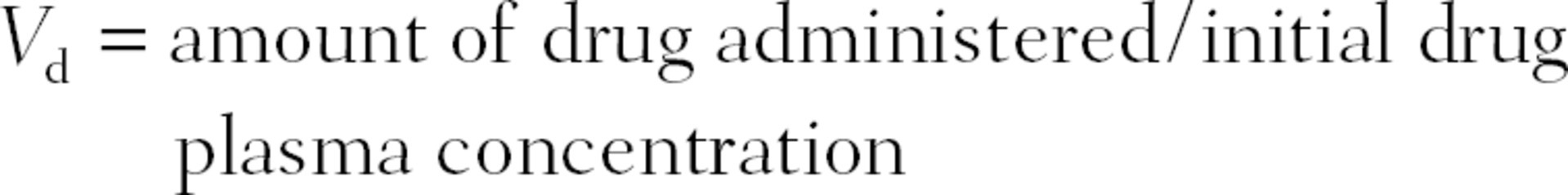

One term used to describe how drugs are distributed throughout the body is the volume of distribution, which is the apparent volume into which the drug has been distributed. This conceptual volume (not actual, physical volume) is calculated by measuring a drug plasma concentration after administration of a known amount of drug. Mathematically, it looks like this:

where Vd is the volume of distribution. It describes the relative drug amount that stays in the vascular compartment vs that which is taken up in the tissues. A high volume of distribution means that very little remains in the blood space (because the measured plasma concentration is very low). A low Vd means that the drug largely stays in the blood space (because the measured plasma concentration is very high). This is a function of the solubility properties of the drug. Those that are highly water soluble (hydrophilic) tend to stay in the blood and have low Vd, while fat soluble (lipophilic) preferentially diffuse out of blood and have a high Vd.

Another way to think of the volume of distribution is to imagine what total volume would be needed to result in the given plasma concentration of a drug knowing the amount administered. For example, if 100 mg of drug A were given and the resulting plasma concentration were 25 mg/L, then the volume of distribution for drug A would be 4 L (100 mg/25 mg/L = 4 L). However, if 100 mg of drug B resulted in a plasma concentration of 1 mg/L, then the volume of distribution for drug B would be 100 L. Drug B has a higher volume of distribution than drug A, even though both drugs were given to the same patient, with the same actual plasma volume.

This occurs because of the different solubilities of the two drugs. Chemically, the body can be simplified down to having a water compartment (the blood space or plasma) and fat/lipid compartment (tissues, cellular component layers, etc.). Drugs dissolved in the body will exist in both of these compartments at different concentrations. The relative concentrations of drug contained within each compartment is dependent on the water solubility vs lipid solubility of the drug. Drugs that are more water soluble are called hydrophilic (“water loving”). Those that are more lipid soluble are called lipophilic (“lipid loving”) or hydrophobic (“water hating”). Since blood has a high water content, drugs with high water solubility tend to stay in the blood space, and a small fraction distributes to other tissues. This leads to a low volume of distribution. Those with high lipid solubility will predominantly diffuse out of the blood space and into the lipid compartment of the body. This leads to a high volume of distribution.

Drug Elimination

Once distributed, drugs do not stay in the body indefinitely. Instead, they are removed by several processes, collectively known as elimination. Most drugs are filtered out of the blood by the kidneys and end up in the urine. Some oral medications are poorly absorbed from the GI tract, so the portion that stays in the GI tract is removed in feces. Others are absorbed, chemically modified in the liver, pumped back into the GI tract, and then removed in feces. Anesthesia gases traverse a rather unusual path. They are breathed into the lungs, enter the bloodstream, and go to the brain (their target organ). They are eliminated in the exact opposite order—once the anesthesia provider stops administering anesthesia gases, delivering only fresh gas (air/oxygen mixture), the gas molecules distributed throughout the body diffuse back into the bloodstream and then the lungs. The patient breathes the gas back into the circuit, and the fresh gas flowing in the circuit carries it away to the scavenging system. Small amounts of most drugs (and their breakdown products) are deposited in sweat, tears, finger nails, and hair, but these routes account for only a tiny fraction of total elimination. These routes are more relevant to Sherlock Holmes and forensic toxicology than to the anesthesia provider. Patients continue to “off-gas” a few parts per million of volatile anesthetic even in the recovery room: these are measured for occupational health purposes and consistently found to be minimal.

Metabolism

Now we need to start thinking about drugs as complex molecules. Some drugs make their way to the urine or feces without undergoing any chemical changes. The majority of drugs, however, undergo extensive chemical reactions and modifications before they are eliminated by the body; this process is known as metabolism. The term “metabolism” is also used in the fields of biology and nutrition to refer to the chemical processes by which an organism uses and stores energy. For our purposes, however, we will use the term to describe only the processes by which drugs are altered.

Drug metabolism is basically the process whereby the body chews up and spits out drugs. Lots of different types of reactions occur in multiple locations throughout the body. The liver is the single most active organ in this process. Its job is to clean or detoxify the blood. The liver houses lots of enzymatic machinery to carry out this task. The most famous of these is the cytochrome P-450 (CYP) system. This is a family of enzymes, each responsible for facilitating one specific type of chemical reaction. Extensive details about these reactions are beyond the scope of this text, but we will give a few examples to give the reader a conceptual understanding.

Drugs can be altered by adding or removing electrons (oxidation/reduction reactions), or chemical bonds can be hydrolyzed, which is when they are broken with the addition of water molecules (hydro = water, lyse = to break apart). These reactions are known as phase I reactions. Phase II reactions involve the addition of larger molecules or functional groups to drugs, thereby altering their structure and solubility.

Why do all these reactions occur? This is how the body detoxifies the blood and eliminates drugs (or any potentially harmful chemical) from the body. Once drugs are chemically modified, they lose their biologic activity, so they no longer exert their effects. Modifications also change the solubility of drugs, so that the body can more easily eliminate them (in either urine or feces).

In healthy patients, the rate at which these processes occur is relatively predictable, which is why a given drug will have a similar effect for the same length of time from one patient to the next. There are differences in some patients that will lead to drastically different results. Since metabolism is carried out by enzymes (proteins that facilitate chemical reactions), patients with certain enzyme deficiencies will exhibit altered drug metabolism. Certain drugs may be toxic to these patients when given at normal doses, or some drugs could exert their effects for a prolonged period of time. A classic example of this is pseudocholinesterase. This enzyme breaks down the drug succinylcholine (neuromuscular blocking agent; see Chapter 14). Our genetic material, DNA, contains all the blueprints for our proteins, and there are two copies of each blueprint for each protein. People with two normal copies of the gene for pseudocholinesterase metabolize the drug at the normal rate, so succinylcholine causes paralysis for about 10 minutes. In people with one normal copy and one bad copy, the drug causes paralysis for 30 minutes. People with two bad copies don’t make any functional enzyme; in these rare patients, this drug can cause paralysis for 8 hours!

There are other reasons why drugs will exhibit altered pharmacokinetics in some patients. The enzymes that modify and deactivate drugs can be dysfunctional or nonexistent. This could be from genetic causes (pseudocholinesterase deficiency) or acquired organ dysfunction (liver failure from alcohol abuse or viral hepatitis). The same is true of kidney disease. In patients with liver or kidney disease, the doses or choices of medications may have to be adjusted because drug metabolism and clearance can be drastically impaired. Other abnormalities can be seen with drugs whose metabolites are more active than the original drug itself. Codeine is a pain reliever and cough suppressant, but codeine itself has very little biologic activity. It has to be metabolized to a structurally related compound, morphine, in order to exert its effects. Some patients lack the enzyme necessary for this conversion, so codeine does nothing for them. Other patients have abnormally high amounts of the enzyme needed, so they are hypermetabolizers. Codeine is especially potent for them. These enzymatic pathways can also exhibit abnormally high activity (rapid metabolism) as a result of drug interactions. Some drugs can up-regulate the drug metabolism enzymes produced by the body. A classic example of this is up-regulation of the CYP system by antiepileptic drugs. Patients taking these medications can require very high doses of other medications because their bodies metabolize them so quickly.

Clearance

How do drugs and their breakdown products get removed from the bloodstream? This is primarily the task of the kidneys. These organs are constantly filtering out large amounts of water and small molecules and then adding back just the right amount of each so as to maintain very tight control of the total amount that remains in the body. They also remove foreign substances like drugs and toxins. The mixture of water, ions, and molecules that kidneys are continually pulling out of the bloodstream is collected and eventually eliminated from the body as urine. The rate at which the kidneys do this is known as clearance. More specifically, clearance is the volume of blood from which a drug or substance is removed for a given period of time. In a given patient, this is a function of how quickly a given drug is typically removed from the blood by healthy kidneys and how healthy that patient’s kidneys are. To assess a patient’s kidney function, clinicians look at a measured creatinine level (part of a basic set of chemistry labs, the so-called “chem. 7 panel” that also includes basic electrolytes and blood glucose). This is used to calculate a patient’s glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which is an approximation of that patient’s kidney function. Some drugs and molecules are quickly removed by the kidneys, and others remain in the blood much longer. Understanding how specific drug properties lead to fast vs slow clearance is beyond this text, but most drugs and molecules have a known clearance rate, which was established by extensive testing in healthy test subjects.

Half-life

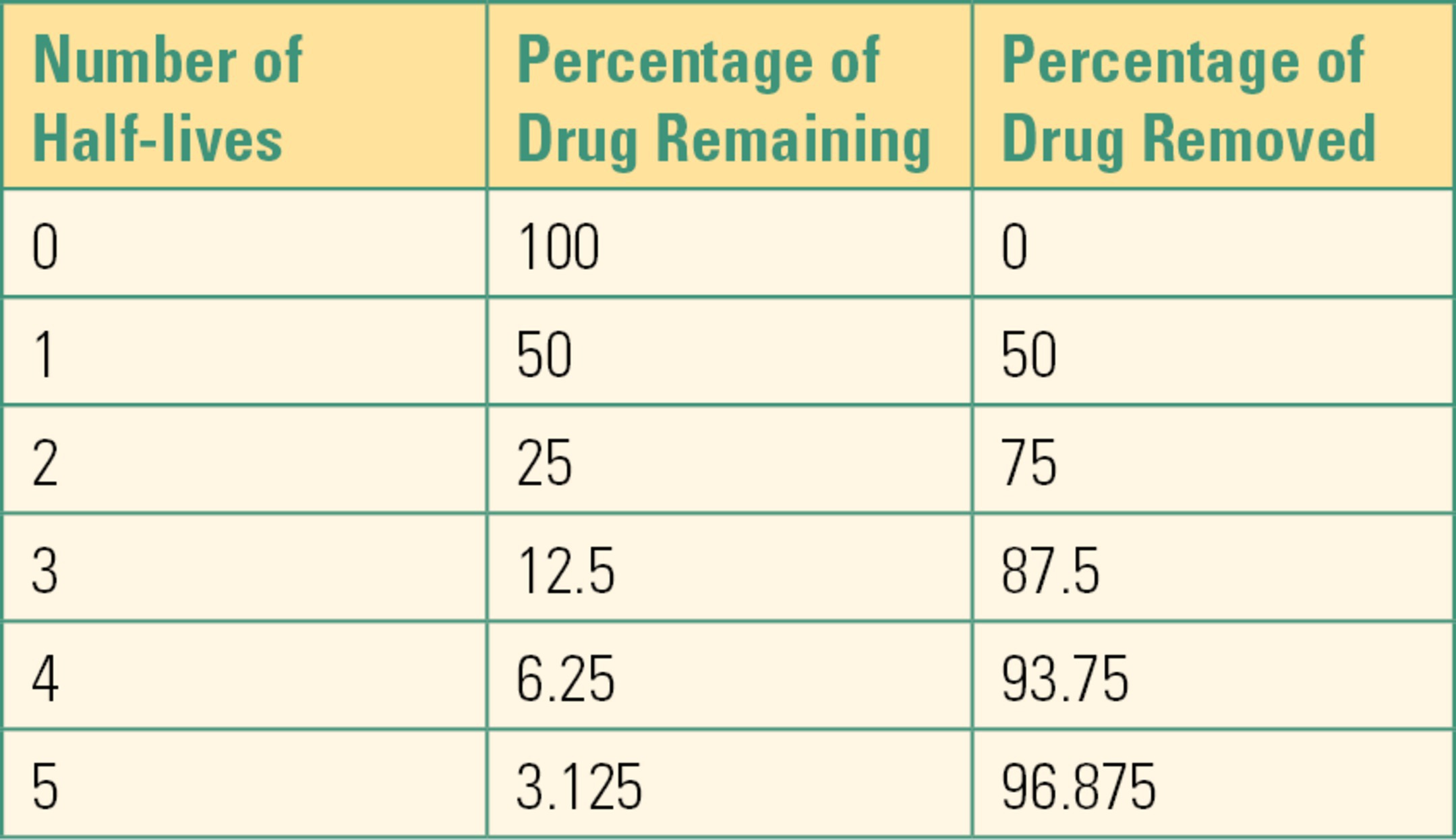

Another concept related to clearance and elimination is that of half-life, t1/2. This term is defined as the amount of time needed for the drug concentration in the body to decrease by 50%. Most drugs follow first-order kinetics, which means that the rate of elimination is directly proportional to the drug concentration. When the drug concentration is at its highest, elimination is the highest. As the concentration drops, its rate of elimination slows down. This means that a fixed percentage of the drug is removed over a given time period, regardless of the drug concentration. If drug A, with a half-life of 2 hours, has a concentration of 100 mg/L in the blood, the concentration will drop to 50 mg/L after 2 hours. After another 2 hours, the concentration will be 25 mg/L and then 12.5 mg after another half-life. Note that the amount of drug eliminated every 2 hours decreases as the concentration decreases.

Some drugs are instead eliminated by zero-order kinetics, which means a fixed amount, rather than a percentage, is removed over a given time. The amount of drug eliminated is fixed and is not related to the concentration or the amount of drug in the body. If the initial amount of drug in the blood is 400 mg, and the body can remove 100 mg/h, it will take 2 hours to reduce the amount down to 200 mg. To reduce the amount to 100 mg, it will take another hour. In this scenario, the half-life changed from 2 hours to 1 hour because it is dependent on the amount of drug present. The vast majority of drugs, however, are cleared by first-order kinetics, so they have a constant half-life, regardless of their concentration (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Half-lives and Corresponding Percentage of Drug Removed

(From Barash PG. Clinical Anesthesia. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2017, with permission.)

Steady State

Drug doses are often given repeatedly, perhaps during a hospital admission or long term for a chronic condition. Most medications have a known concentration at which they are effective. How do we achieve and maintain this effective concentration, if the body is constantly metabolizing and removing it from the system? In order to schedule dosing, we need to understand the concept of steady state. Since most drugs are removed by first-order kinetics, a fixed percentage of drug is removed per unit time. If we want the drug concentration to remain constant, we must add back (re-dose) the same amount that is removed per unit time. When equal amounts of drug are being both added and removed, the concentration of the drug will remain constant (with minor fluctuations), and the drug is said to be in steady state.

We can arrive at this by two different approaches. The easiest, and most common, is simply to repeat fixed doses at a fixed interval (give 20 mg of rocuronium every hour). If the desired effect is not achieved, the dose (or frequency) is increased (give 30 mg every hour). For the first few doses, there can be significant fluctuations in drug concentrations, but eventually, we will reach a steady state because repeated doses will drive the average concentration up. As the concentration increases, the rate of elimination also increases (assuming first-order kinetics).

The other common approach to achieving a steady state is to give an initial large dose, or “loading dose,” which will be distributed and achieve the desired concentration. This is followed by repeated doses that are much smaller. The frequency and size of these “maintenance doses” is chosen so that they replace the amount of drug eliminated. There will be small troughs in drug concentration just before the next dose, and there will be a small peak in the concentration just after each dose. The doses and intervals are chosen so as to prevent any problems from too low or too high of drug concentrations (Fig. 3.3). These fluctuations can be prevented entirely by giving maintenance doses in the form of a constant infusion. If the rate of infusion is equal to the rate of elimination, we have achieved steady state. Even if the rate of administration is a little too high or low, the drug concentration will only change slowly, so adjustments in the infusion can be made to keep the drug concentration at its goal.

FIGURE 3.3. The other common approach to achieving a steady state is to give an initial large dose or “loading dose.”

Pharmacodynamics

We’ve covered what happens to a drug inside the body, now let’s look at how a drug affects the body. Pharmacodynamics is the study of the biochemical, physiologic, and molecular effects of a drug on the body.

Mechanism of Action

How do drugs cause the changes that they do? How do analgesics reduce the sensation of pain? How do antihypertensive drugs reduce blood pressure? How do antibiotics kill bacteria? The changes start with a molecular interaction between the drug and its target molecule. This sets off a sequence of events that are amplified into cellular changes, and ultimately the tissues and organs behave differently. This cascade of events is known as the mechanism of action (MOA). Some drugs bind to receptors on the surface of cells, others either increase or decrease the rate of some process by interacting directly with enzymes, and others interact directly with DNA to change the amount of proteins that are made by the cell.

Receptors and Ligands

Most drugs exert their effects by interacting with receptors. These are molecules that are typically located on cell surfaces and possess a structure that is perfectly complementary to the drug structure so that they fit together like a lock and key. Ligand is the generic term for molecules that bind to receptors. When a ligand binds to its receptor, it initiates a cascade of events within the cell that culminates in some desired effect. This effect could be contraction of smooth muscle causing vasoconstriction, or it could change how ion channels on a cell membrane function, thus altering the cell’s electrophysiology.

Agonists, Partial Agonists, and Antagonists

Receptors are often capable of binding several different ligands, though each one may not produce the same effect. Agonists are ligands that bind to a receptor and produce an effect. If a drug is capable of producing the maximal drug effect when bound to the receptor, it is said to be a full agonist. If, however, it is only capable of producing a partial drug effect, it is said to be a partial agonist. Partial agonists will never be able to produce the maximum drug effect, even in large amounts. This concept can be seen with opioids. Fentanyl is an opioid and binds to the opioid receptor. When it does, it causes pain relief (and many other opioid effects: sedation, respiratory depression, constipation, itching). It is a full agonist, so its binding will maximally activate the opioid receptor, resulting in cellular changes. Nalbuphine also binds to the opioid receptor, but it is a partial agonist, which means that no matter how high the dose, it will only partially activate the opioid receptor and, in turn, induce only a fraction of the cellular changes that result from opioid receptor binding.

The opposite of agonists are antagonists, which are ligands that bind to receptors but do not produce any activation or downstream effects. Not only do they not cause activation but their binding can prevent agonists from binding to the receptor. Antagonists can be either competitive or noncompetitive. Competitive antagonists bind to receptors in a reversible fashion at the same part of the receptor as where the agonists bind; two different ligands are competing for the same binding site. If the agonist is present in high enough concentration, then it will out-compete the antagonist, and it will occupy the binding sites on the majority of receptors present, and it will be able to exert its effects. If the antagonist is more abundant, or if it binds more tightly, then it wins the battle and will occupy the majority of receptor binding sites, preventing activation.

There is another type of antagonist. Noncompetitive antagonists bind to receptors at a location different from where agonists bind. When these antagonists bind, they cause a shape change in the receptor that then prevents the agonist from binding at all. No matter how high the agonist concentration is, it cannot out compete the antagonist, so there will be no receptor activation.

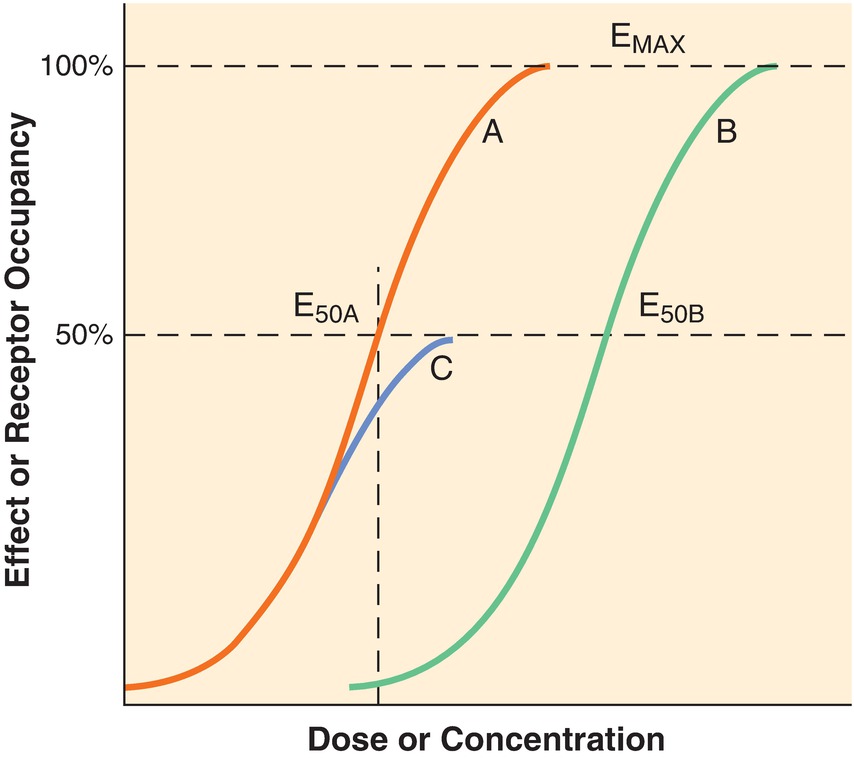

Potency and Efficacy

Drugs that act at the same receptor or target may not produce equal effects. Efficacy refers to the maximum effect a drug is capable of producing. Full agonists are therefore, by definition, 100% efficacious, whereas a partial agonist will be less than 100%. Potency refers to the dose of drug needed to produce an indicated response. It is generally expressed as the median effective dose (ED50), or the amount required to produce the desired response in 50% of a population. Fentanyl and morphine both bind to the opioid receptor and are full agonists. However, fentanyl exerts these effects at a much smaller dose, about 1/100th of the dose of morphine. So, they are equally efficacious, but fentanyl is more potent. Graphically, efficacy and potency can be represented by using a dose-response curve. This is a graph where the dose or concentration of drug is plotted on the x-axis and the magnitude of effect or response produced is plotted on the y-axis (Fig. 3.4).

FIGURE 3.4. Schematic pharmacodynamic curves, with dose or concentration on the x-axis and effect or receptor occupancy on the y-axis, that illustrate agonism, partial agonism, and antagonism. Drug A produces 50% of maximal effect at dose or concentration ED50A and then a maximum effect, Emax as the dose is increased. Drug B, also a full agonist, can produce the maximum effect, Emax; however, it is less potent (ED50B > ED50A). Drug C, a partial agonist, can only produce a maximum effect of approximately 50% Emax. If a competitive antagonist is given to a patient, the dose response for the agonist would shift from curve A to curve B—although the receptors would have the same affinity for the agonist, the presence of the competitor would necessitate an increase in agonist in order to produce an effect. In fact, the agonist would still be able to produce a maximal effect, if a sufficient dose were given to displace the competitive antagonist. (From Barash PG. Clinical Anesthesia. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2017, with permission.)

Looking at the figure, a curvilinear relationship is seen. At very low doses, there is little drug effect. Eventually, a point is reached where the slope increases quickly, indicating that small increases of dose result in large changes in effect. Between 20% and 80% of maximum effect, the relationship is usually linear. Once the effect has reached close to the maximum, again, changes in drug dose have little change on the effect.

Efficacy is measured by comparing the maximum height of each curve. As shown, Drugs A and B both reach 100% of effect and therefore are full agonists. Drug C never reaches 100% of effect; it is a partial agonist. Drugs A and B are both full agonists but differ in potency; they reach the same effect but at different doses/blood concentrations. Drug B requires a higher concentration (x-axis) to reach the ED50 (y-axis). This decrease in potency of drug B likely reflects lower affinity for the receptor than drug A.

Therapeutic Index

In addition to the median effective dose, there is also a median lethal dose (LD50), which is the dose that causes death in 50% of the test subjects taking that dose. The ratio of the median lethal dose to the median effective dose is termed the therapeutic index (TI):

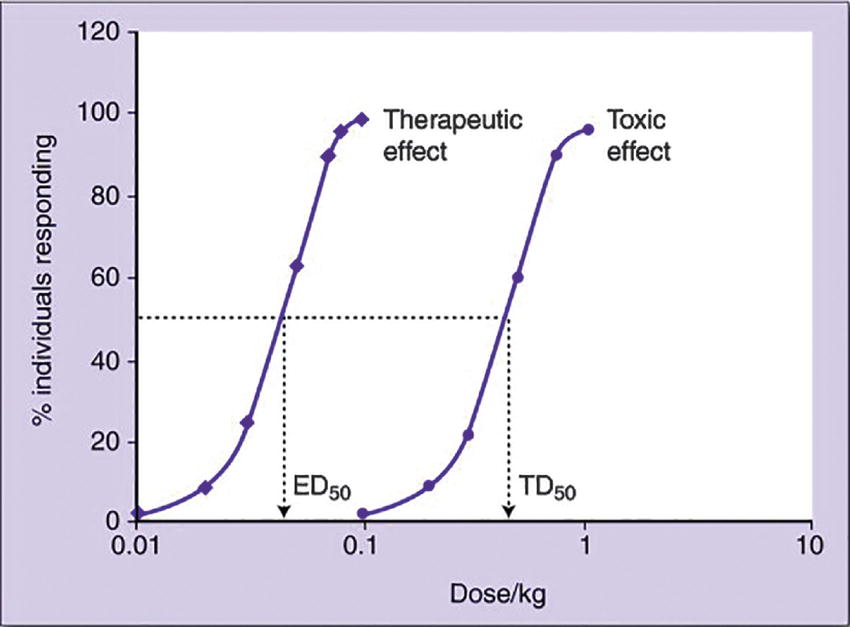

Traditionally, the “lethal dose” was used to define TI, but therapeutic index is now used with other markers of toxicity (since patients usually present with other signs of illness, instead of death). Therapeutic index is thus the ratio between a drug’s effective dose and its toxic dose. A large therapeutic index is a good quality in a drug, as it indicates a greater degree of safety. If a patient takes increasing doses (or if impaired liver or kidney function causes a build-up of the drug in the patient’s system), there is a chance for drug toxicity. A narrow TI means that the drug will cause toxic effects with only small increases in doses, whereas a wide TI means that even very large overdoses (doses greater than those needed to be effective) are not harmful (Fig. 3.5).

FIGURE 3.5. Quantal dose-response curves for the therapeutic effect and toxic effect of drug X. The ratio TD50/ED50 gives the therapeutic index (TI) of the drug. Drug X has a TI = 10. Note that very little toxicity will be seen at a dose that gives therapeutic effect in greater than 90% of individuals. (From Pandit N, Soltis RP. Introduction to the Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011, with permission.)

Drug-Drug Interactions

During the perioperative period, patients receive a large variety of medications. Anesthesia providers typically give many types of drugs intraoperatively, recovery nurses have a new set of medications to give, and patients may resume their normal medications after discharge, as well as any specific new postoperative medications. The anesthesia provider must be aware of any possible drug-drug interactions and their consequences, whether beneficial or harmful.

Drug-drug interactions may be pharmaceutical, pharmacokinetic, or pharmacodynamic in nature. Pharmaceutical interactions are the result of two or more drugs acting directly on one another as chemicals. This could happen if two medications are in solutions that are not compatible with each other. If they are injected into the same intravenous tubing, they react with each other, or they may form a solid and precipitate out of solution. An example of this can be seen by mixing rocuronium (neuromuscular blocker) and thiopental (induction agent, no longer available in the United States); within seconds, they form a solid precipitate that may occlude the IV tubing if injected at the same time. An example where a pharmaceutical interaction is beneficial is rocuronium and sugammadex. Sugammadex was designed as a reversal agent for rocuronium; it will grab onto any rocuronium floating around in the blood or tissue and prevent it from interacting with its target (acetylcholine receptor). It will even pull rocuronium off of its receptor-binding site. Sugammadex can reverse the paralyzing effects of rocuronium within seconds.

Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions are seen when the actions of one drug cause an alteration in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of another drug. Some pills need to be taken alone, with food, or without food because their absorption into the GI tract can be blocked by the presence of other medications or nutrients. Antacids can reduce the absorption of some drugs because they alter the gastric pH. Another example is the use of epinephrine in nerve blocks. Local anesthetics can be injected around nerve bundles to reduce pain or provide anesthesia for surgery; epinephrine can be mixed in so that it will cause vasoconstriction and reduce blood flow to the area. This prolongs the action of the local anesthetic because it doesn’t absorb into the bloodstream and get removed from the area quite so quickly. Recall that the liver and kidneys are largely responsible for metabolizing and clearing drugs from the system. There are many drugs that alter liver and/or kidney function, so other drugs can be affected by these mechanisms as well. If the CYP enzyme system in the liver is down-regulated or impaired, drugs that are normally metabolized by this pathway will build up in the system and may reach toxic levels. If the CYP is up-regulated, other medications may be metabolized faster than expected, and they may not reach therapeutic levels. Drugs that impair CYP include antifungals and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, for depression); drugs that up-regulate the CYP family include alcohol, phenytoin, and St. John’s wort.

Pharmacodynamic drug-drug interactions are those whereby one drug directly influences the effect of another, usually as a result of interactions at the same receptors. The end result may be an effect that amplifies the individual drug effects. Most sedating drugs (such as propofol and fentanyl) work together to produce greater sedation than would be expected if the drug effects were simply added together. This leads to greater sedation, and greater respiratory depression, than when each drug is used alone. Interactions may also be antagonistic such as in the case of opioids and naloxone; both compete for the opioid receptor, but naloxone (competitive antagonist) prevents other opioids from binding.

Summary

One of the most basic actions of anesthesia is the administration of medications to alter consciousness. Medications are the tools of the anesthesia provider, and each has fundamental properties: efficacy, potency, half-life, receptor interactions, metabolism, toxicity, therapeutic index. The anesthesiologist must understand them fully and how they may be altered by a patient's condition in order to care for the patient safely and effectively. The foundational drugs of anesthesia will be discussed throughout this textbook, but pharmacology itself, the principles of how all medications work in the body, has been the topic of this chapter. This is the foundation for why some medications are given by infusion pumps, some by vaporizers, some in pills, and some in patches (bioavailability and half-life). Some must be given under careful supervision by experts, because their therapeutic index is low, and a small change in dose can be fatal; some can be sold over the counter, because their therapeutic index is large, and their toxicity is limited. Two medications can have the same effect, even though they are given at different doses (lower potency). One medication can be less effective than another, even though its dose is larger (lower efficacy). A patient may appear alert after a small dose of one sedating medication but then be apneic when given a small dose of another (drug-drug interaction). Understanding these processes, and (as covered in later chapters) the medications themselves, will help you understand anesthesia practice and how you can support providers and patients in safe care.

Review Questions

1. What process is responsible for the offset of effects of a bolus of propofol?

A) First-pass effect

B) Redistribution

C) P-450 enzyme reduction

D) Increased renal blood flow

E) None of the above

Answer: B

Redistribution. The bolus of propofol is mixed and distributed rapidly to the central compartment and the vessel-rich group. Subsequently, the plasma level falls as the propofol is redistributed to muscles and the vessel-poor group.

2. Half-life is defined as:

A) Halfway to the expiration date for a drug

B) The time it takes the body to eliminate 50% of a drug

C) The dose of drug that is effective in 50% of patients

D) One-half the volume of distribution

E) None of the above

Answer: B

Drugs are gradually eliminated from the body. Some are eliminated at a constant rate (x amount of drug per hour) in a process known as zero-order kinetics. With the vast majority of drugs, a first-order kinetic process is observed in which the amount of drug eliminated is dependent upon the concentration of the drug—a fixed percentage of the drug, not a fixed amount, is eliminated each hour. The half-life is the amount of time it takes for 50% of the drug to be eliminated.

3. Which of the following is not a primary site of drug metabolism?

A) Liver

B) Kidney

C) Plasma

D) Heart

E) Lungs

Answer: D

Drugs are primarily metabolized by the liver. However, the kidneys, lungs, and plasma are also sites of metabolism.

4. Which of the following statements about partial agonists is FALSE?

A) Partial agonists act at the same site as full agonists.

B) Partial agonists can be as efficacious as full agonists if large amounts are used.

C) Partial agonists may also have antagonistic properties.

D) Partial agonists’ efficacy is unrelated to their potency.

E) None of the above.

Answer: B

By definition, a partial agonist is a ligand that operates at a receptor and produces an effect that is submaximal when compared to the effect of a full agonist. This cannot be overcome by increasing the amount of partial agonist administered. In the presence of a full agonist, a partial agonist may compete for the receptor binding site and thus act as an antagonist. A partial agonist’s efficacy is not the same as a full agonist: the amount of drug required to achieve that efficacy (i.e., its potency) is unrelated and may be large or small.

5. Which of the following combinations will produce the safest drug profile?

A) Large LD50, large ED50

B) Small LD50, small ED50

C) Large LD50, small ED50

D) Small LD50, large ED50

Answer: C

A higher therapeutic index indicates a safer drug profile. By definition, TI = LD50/ED50. Therefore, a high LD50 and a low ED50 would lead to the greatest degree of safety.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Barash PG. Basic principles of clinical pharmacology. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017:241-276.

Corrie K, Hardman JG. Mechanisms of drug interactions: pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics. Anaesth Inten Care Med. 2011;12(4):156-159.

Hall JE, Guyton AC. Introduction to endocrinology/mechanisms of action of hormones. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016: 930-935.

Hall JE, Guyton AC. Organization of the nervous system, basic functions of synapses, and neurotransmitters/action of the transmitter substance on the postsynaptic neuron—function of “Receptor Proteins”. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:582-584.

Miller RD, Pardo M, Stoelting RK. Basic pharmacologic principles. Basics of Anesthesia. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011:35-49.

Pleuvry BJ. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic drug interactions. Anaesth Inten Care Med. 2005;6(4):129-133.