CHAPTER 15

Sedation

Introduction

Sedation is a service frequently utilized throughout hospital environments. This service makes patients calm and relaxed and allows for the completion of diagnostic and interventional procedures that may not require general anesthesia. When compared to general anesthesia, sedation may result in fewer side effects, like nausea and vomiting, and shorter recovery times.

The term sedation represents the varying states of consciousness and responsiveness induced by the administration of medication by anesthesiologists and nonanesthesiologists. Sedation exists on a spectrum between anxiolysis and general anesthesia (Fig. 15.1). Anesthesia providers are trained to titrate medications in order to achieve varying depths of sedation and manage the cardiopulmonary impact of these medications. The cardiopulmonary impact of sedatives varies greatly from patient to patient and may be unpredictable. Therefore, providers must be capable of interventions such as the reversal of medications, airway support and management, or a transition to general anesthesia. Monitored anesthesia care (MAC) refers to the administration of sedation, at any level of consciousness, by an anesthesia provider. The older term “conscious sedation” or, also commonly, “nursing sedation” refers to the administration of limited, usually moderate, sedation, by nonanesthesia providers credentialed by their institution.

FIGURE 15.1. Continuum of Sedation.

Sedation services across multiple disciplines are governed by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). These practice guidelines and the accompanying recommendations are available from each organization.

Definition of Terms

The following definitions were written and approved by the ASA Task Force on sedation guidelines.

Minimal sedation (anxiolysis) is a drug-induced state during which patients respond normally to verbal commands. Although cognitive function and physical coordination may be impaired, airway reflexes and ventilatory and cardiovascular functions are unaffected.

Moderate sedation/analgesia is a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by light tactile stimulation. No interventions are required to maintain a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilation is adequate. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained.

Deep sedation/analgesia is a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients cannot be easily aroused but respond purposefully following repeated or painful stimulation. The ability to independently maintain ventilatory function may be impaired. Patients may require assistance in maintaining a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilation may be inadequate. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained.

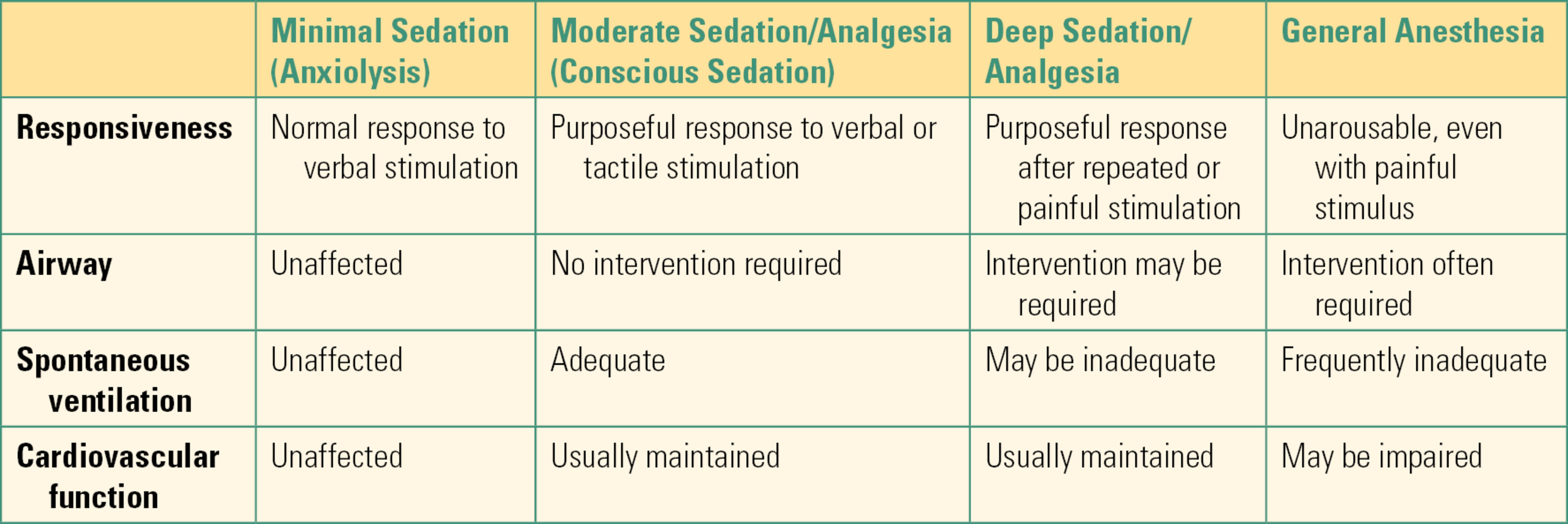

General anesthesia is a drug-induced loss of consciousness during which patients are not arousable, even by painful stimulation. The ability to independently maintain ventilatory function is often impaired. Patients often require assistance in maintaining a patent airway, and positive pressure ventilation may be required because of depressed spontaneous ventilation or drug-induced depression of neuromuscular function. Cardiovascular function may be impaired (Table 15.1).

Table 15.1. American Society of Anesthesiology Depth of Anesthesia Definitions

ASA Recommendations

Sedation is a continuum, and it is not always possible to predict how an individual patient will respond. Therefore, practitioners intending to produce a given level of sedation should conduct a presedation evaluation, use standard monitoring equipment, and have support equipment available.

Presedation Evaluation and Preparation: A focused physical examination, including an airway exam, along with a review of pertinent medical history may increase the likelihood of a satisfactory sedation and decrease the likelihood of complications. For example, patients who do not adhere to preoperative fasting guidelines are at risk for pulmonary complications associated with aspiration and thus are not suitable candidates for sedation.

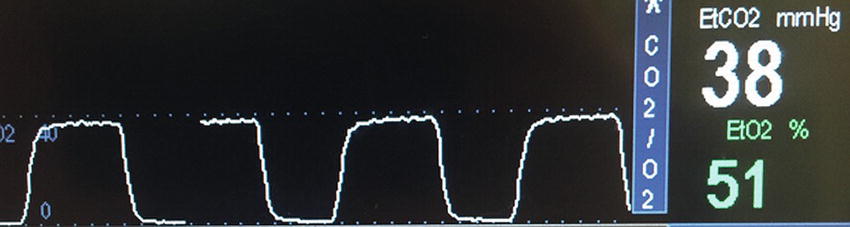

Monitoring: Standard ASA monitors must be applied prior to the start of sedation. These monitors must be observed and recorded throughout the administration of sedation and until the patient enters recovery. The cardiac effects of sedation are monitored via blood pressure, heart rate, and electrocardiograph. Adequate oxygenation is assessed via pulse oximetry, and ventilation is continuously assessed with end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2). The use of EtCO2 (Fig. 15.2) during sedation is a relatively new standard of care set by the ASA and accepted by CMS.

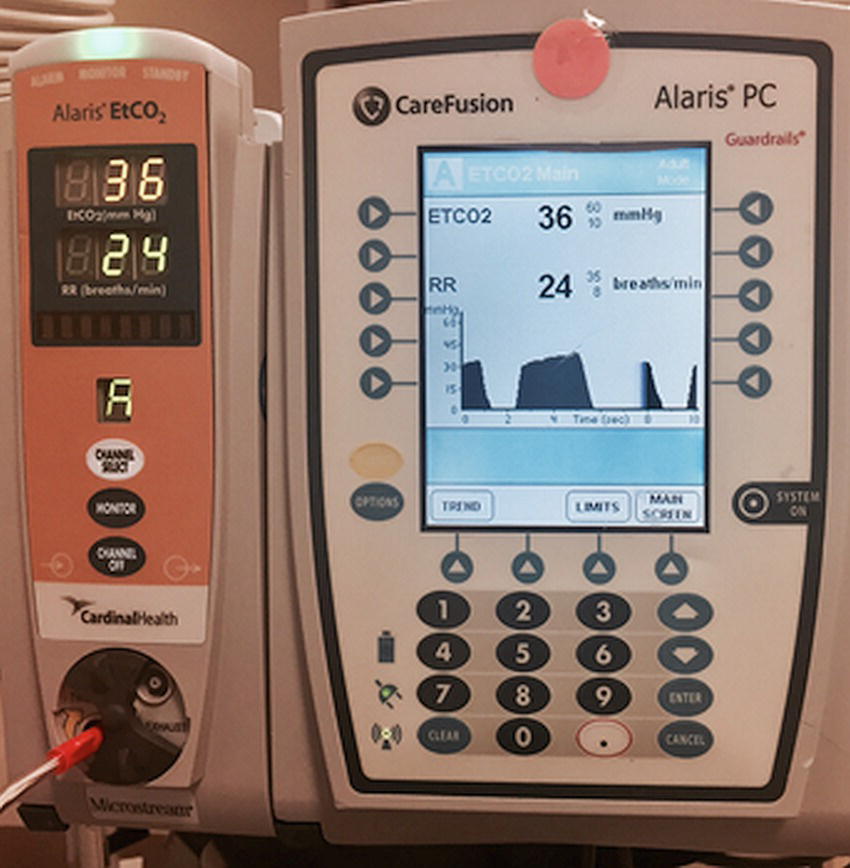

For out of operating room (OOR) procedures, transportable EtCO2 monitors exist for a variety of applications (Fig. 15.3). The rapid detection of hypoxemia via pulse oximetry, coupled with the rapid detection of airway obstruction or apnea using EtCO2 monitors, may decrease risk of cardiorespiratory compromise during moderate and deep sedation.

Support Equipment: Preparation of airway equipment and resuscitation medications prior to a sedation case is the standard of care. Anesthesia providers are trained to assess the impact of sedatives and analgesics, intervene if necessary, and mitigate any negative effects. Rescue equipment, including the ability to provide positive pressure ventilation, vacuum suction, and reversal medications for opioids and benzodiazepines, should be readily available.

FIGURE 15.2. EtCO2 waveform.

FIGURE 15.3. Portable capnograph designed for use during sedation.

Medication Selection

The characteristics of the ideal anesthetic would include rapid onset of sedation and analgesia, easy titration, cardiopulmonary stability, absence of toxic effects, and rapid recovery. Unfortunately, no single medication possesses all these qualities. Usually, the anesthesia provider administers multiple agents in order to achieve safe and satisfactory sedation. Some of the most common agents are listed below.

Propofol is a sedative frequently administered by anesthesia providers during sedation cases. This intravenous medication is prepared in a white emulsion. Propofol can be administered in an individual bolus dose but is frequently titrated as an infusion for sedation. In comparison to other sedatives, propofol provides rapid onset and clearance. The drug can also reduce the incidence of nausea and vomiting. The ASA recommends that this drug be administered only by an anesthesia provider because of its high risk of causing hypotension and apnea.

Dexmedetomidine is an anxiolytic, sedative, and analgesic that is commonly administered via infusion. This medication provides sedation without respiratory depression, a notable characteristic when compared to propofol, opioids, and benzodiazepines. Dexmedetomidine has demonstrated utility during awake fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) and prolonged mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic that provides sedation and analgesia while maintaining airway reflexes, ventilatory drive, and cardiovascular stability. It is frequently used in settings where patients need pain relief but opioids are not suitable or where patients are at risk for cardiac or respiratory compromise. Its dissociative sedation is characterized by a trancelike state. Some of the side effects of ketamine include hallucinations, hypersalivation, and emergence delirium.

Benzodiazepines are a class of medications that can be used to reduce anxiety and achieve sedation. Medications like midazolam (commonly referred to by its trade name, Versed) are a mainstay of moderate and deep sedation cases. Benzodiazepines reliably achieve amnesia but pose a risk of paradoxical reactions in elderly patients.

Opioids are frequently necessary for moderate and deep sedation because commonly used sedatives (with the exception of ketamine) do not provide pain relief. Fentanyl and alfentanil possess rapid onset and clearance. Opioids and benzodiazepines have a synergistic effect on respiratory depression when used in combination.

Reversal agents exist for both benzodiazepines and opioids. These agents provide a layer of safety during sedation, especially in moderate sedation by a nonanesthesiologist provider. Naloxone (also commonly referred to by its trade name, Narcan) provides a rapid reversal of opioids, and flumazenil can be used to reverse the sedative effects of benzodiazepines.

Common Cases

In any anesthesia practice, sedation services represent a significant amount of the daily workload. Sedation and OOR anesthesia also represent a significant percentage of anesthesia morbidity and of anesthesia-related lawsuits. The practice of anesthesia sedation is common and deceptively “simple” but can be very challenging: when ASA and CMS guidelines are met, sedation can be provided anywhere in the hospital (see Chapter 50, Anesthesia Outside the Operating Room), and the anesthesia technician is an essential ally in its safe performance.

Sedation can be effective for diagnostic and interventional cases. In general, sedation works best in minimally invasive (endoscopic or percutaneous) procedures resulting in minimal periprocedure pain. The following section presents common procedures that illustrate the use of sedation.

Gastrointestinal procedures: From basic endoscopy to advanced interventional procedures, sedation by anesthesia and nonanesthesia providers in the gastrointestinal suite is ubiquitous. These natural orifice procedures are relatively short in duration and result in minimal pain. Administration of benzodiazepines and opioids are effective for moderate sedation. Propofol infusions are used for deep sedation for advanced endoscopy and to facilitate rapid recovery.

Interventional radiology (IR) procedures: These procedures require highly specific radiologic equipment and are usually conducted out of the operating room. Most of these cases are accomplished through percutaneous access and result in minimal postprocedure pain. Sedation can help patients who may struggle to remain in one position during longer procedures.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Patients that suffer from anxiety, claustrophobia, developmental delays, or neurologic and orthopedic discomforts may require sedation to endure the MRI experience. The imaging is accomplished by placing a patient within a magnetic coil. The space for the patient is small and uncomfortable (Fig. 15.4), and the patient is remote from the anesthesia provider. Since MRI is a diagnostic procedure, postoperative pain is limited to the discomfort of positioning. A combination of benzodiazepines and sedative infusions are commonly administered. See Chapter 52, “MRI Safety,” for more details both on the MRI environment and the unique challenges of anesthesia care here.

Regional or neuraxial blocks: During the placement of blocks, the patient must be responsive enough to report pain or other complications related to the block. Sedation is titrated during block placement to improve safety, reduce patient anxiety or discomfort, and optimize conditions. A patient’s ability to report symptoms during the procedure can prevent nerve injury and local anesthetic toxicity.

In combination with block: A dense regional block in the area of surgical interest, whether a neuraxial block, peripheral nerve block, or field/local block is effective as the primary anesthetic. Sedation may then be administered to improve patient satisfaction, reduce anxiety, or induce amnesia. In the event of block failure, the anesthesia provider may choose urgently to induce general anesthesia, as even deep sedation is rarely a good substitute for a regional anesthetic that is not working well; the AT may be an essential resource to the anesthesia provider, especially in a rapidly evolving situation with an uncomfortable patient.

FIGURE 15.4. MRI scanner.

Summary

Sedation exists on a spectrum from minimal to deep and is provided throughout hospital environments, by both anesthesia and nonanesthesia providers. Advances in monitoring and the wide variety of titratable and reversible medications have made sedation safer and reliable. Anesthesia providers are trained to recognize and treat the varied cardiovascular and respiratory effects of sedation. Organizational and institutional guidelines govern all aspects of sedation including training, the evaluation of patients prior to sedation, monitoring, and support equipment.

Review Questions

1. When providing moderate sedation for a patient, the anesthesia provider is

A) Not permitted to use propofol

B) Expecting the patient to be able to maintain his or her own airway

C) Not required to record vital signs as often as for other anesthetics

D) Not required to perform a physical exam prior to the case

E) None of the above

Answer: B

As defined by the ASA, moderately sedated patients should be able to maintain their own airway without assistance. Patients who require adjuncts or support to maintain their airway are by definition deeply sedated. All sedation cases require appropriate preprocedure evaluation including a physical exam. A sedation case does not obviate the need for ASA standard monitoring and frequent recording of vital signs. An anesthesia provider is not limited in drug selection for sedation cases.

2. Dexmedetomidine is used for providing sedation for procedures

A) Only in cardiac cases

B) When the surgeon or endoscopist wants the patient deeply sedated

C) For procedures that are not painful, but amnesia is very important

D) Where preservation of respiratory function is important

E) Only in the ICU

Answer: D

Dexmedetomidine is a unique sedative that produces analgesia and sedation without respiratory or significant cognitive depression and without amnesia. It is well validated in the ICU but is not used exclusively there. Patients properly sedated with dexmedetomidine are sedated but cooperative. It does not cause cardiac dysfunction and can be good for cardiac patients because of its preservation of breathing, but it can cause heart rate slowing and drops in blood pressure.

3. The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends that propofol

A) Should only be used for deep sedation

B) Should only be used for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia

C) Should only be used with a controlled infusion

D) Should only be used by an anesthesia provider

Answer: D

Propofol is used both for sedation and for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. It can be given by bolus or infusion; it is usually titrated by infusion for sedation, but this is not a requirement. The ASA does recommend that it be given by an anesthesia provider given the high risk of hypotension and apnea associated with the drug.

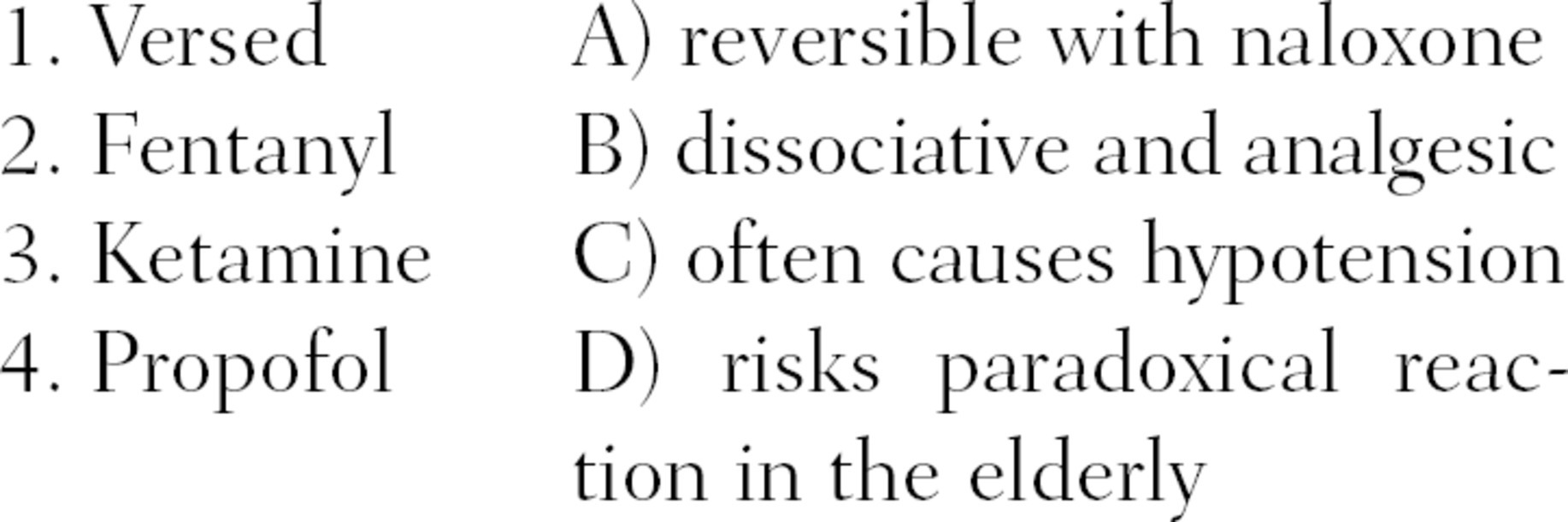

4. Match the drug to its unique property

Answer: 1/D, 2/A, 3/B, 4/CBenzodiazepines, like midazolam (commonly referred to by its trade name, Versed, though it is almost always sold as a generic now), can cause paradoxical agitation in the elderly. Fentanyl, like all opioids, is rapidly reversed by naloxone. Ketamine is uniquely “dissociative” and produces a trancelike state in which patients appear awake but may be unresponsive or apparently nonsensical and have profound analgesia. Propofol, in addition to its depression of the level of consciousness, is a vasodilator and can produce hypotension.

SUGGESTED READINGS

American Society of Anesthesiologists Task for on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017.

Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of General Anesthesia and Levels of Sedation/Analgesia. Committee of Origin: Quality Management and Departmental Administration. Approved by the American Association of Anesthesiology House of Delegates on October 27, 2004 and amended October 21, 2009.

Revised Appendix A Section 482.52. Condition of Participation: Anesthesia Services. CMS Manual System. Effective December 2, 2011

Standards for Basic Anesthetic Monitoring. Committee of Origin: Standards and Practice Parameters. Approved by the ASA House Delegates on October 21, 1986, last amended on October 20, 2010 and last affirmed on October 28, 2015.