Previous Chapter | Next Chapter | Main Table of Contents

The Rainforest | Interior Forests | Tundra | Ice | The Mountains | The Sea

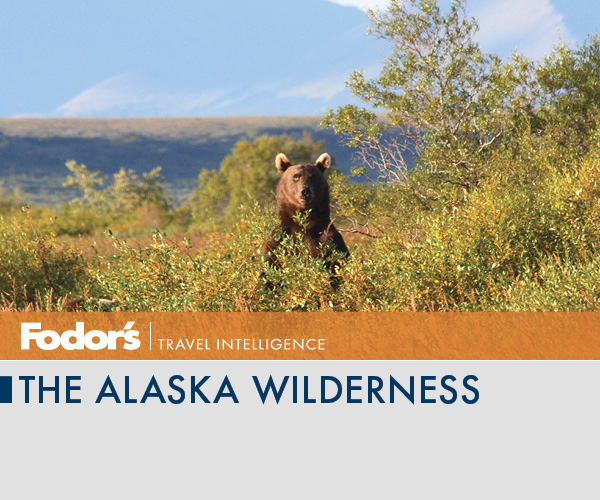

If Alaska were a country, it would be the seventh largest, just behind Australia but way ahead of India. And the state is as diverse as it is vast, with more than 5,000 miles of coast, myriad mountain ranges, alpine valleys, salmon-rich rivers, clear lakes, blue glaciers, temperate rain forests, and sweeping tundra. The Alaska wilderness is clearly the place for unforgettable outdoor adventures.

While Minnesota was busy bragging about 10,000 lakes, Alaska stopped counting after 2 million. Four great mountain ranges—the St. Elias, Alaska, Brooks, and Chugach—and more than 30 lesser chains sweep through the state. The St. Elias mountains form the world’s highest coastal range. The Alaska Range contains North America’s highest peak: Mt. McKinley—or Denali, as Alaskans call it—at 20,320 feet. The Brooks Range roughly follows the Arctic Circle, and the Chugach arcs through the state’s most populous region along the South Central coast.

Alaska flora and fauna is just as varied. Along the northern coast polar bears take to the ice to hunt seals. Seventy-foot-long whales swim slowly past the grassy islands of the Aleutians. Voles weighing not much more than a postcard hide in the Southeastern rain forest. The sky is filled with nearly 500 species of birds, including the largest population of bald eagles anywhere. And among all those mountains lie North America’s two largest national forests with more than 30 kinds of berries for the grizzly bears, which can grow to 11 feet tall and weigh more than a thousand pounds.

Indeed, this state has more parks, wilderness areas, and wildlife refuges than all the others combined. You can travel here for a lifetime and still find surprises, so the first step in planning any visit is determining which Alaska flora and fauna interest you most. Understanding the various ecozones; learning about the wildlife-viewing opportunities they hold; and finding the best activities, tours, and guides in each will go a long way toward creating a memorable outdoor adventure. Pick as much territory as time allows, and get ready for the last great place.

The Rainforest

The largest chunk of intact rain forest in North America lies in Alaska, scattered across hundreds of islands of the Southeast panhandle. This area—stretching from south of Ketchikan up to Skagway and mostly set aside as the Tongass National Forest—is a rich, dripping landscape of forested mountains coming straight out of the sea.

The spaces between the trees are filled with devil’s club, shelf fungus, dozens of kinds of ferns and moss and lichens, and enough berries—salmonberries, blueberries, huckleberries, raspberries, crowberries, and more than a dozen other kinds—to explain the common sight of the deep impression of a bear’s footprint in the ground.

But it’s water that truly defines the region: the 100 inches or more of rain that fall on most parts of it, feeding streams that lace through the forest canopy, bringing salmon and everything that hunts salmon, from seals to bald eagles. Even the trees along streambeds get a large percentage of their nutrients from bits of salmon left after everyone is done eating, water dripping from branches and needles and leaves speeding the decay.

Throughout the forest, decay is vital, because there is almost no soil in the Tongass—a couple of inches at best. New life sprouts on fallen trees, called “nursery logs,” and often a couple of dozen species of plant grow on a spruce knocked down by spring storms; adult trees grow oddly shaped near their base, evidence of the nursery tree they once grew on.

And the Tongass isn’t the only rain forest in Alaska; much of the Chugach National Forest, as well as most of the coastline from Valdez to Seward and beyond, is also rain forest.

Under the canopy, ravens yell, bears amble from berry bush to berry bush, Sitka black-tailed deer flit through the thick underbrush like ghosts. The rain forest is a riot of life, the best of what water, time, and photosynthesis can build.

Safety

Although Devil’s Club is commonly used for medicinal tea by Southeast Natives, it’s also the region’s only dangerous plant: the spines covering the plant’s branches and undersides of the leaves can break off and dig into the skin of passing animals and hikers, where they can fester and infect.

Look out for tall plants with five-lobed leaves 6 inches across. It grows in large patches or solitarily in well-drained areas.

Rain Forest Flora

Southeast’s rain forest is one of the most diverse territories in the world: from towering old-growth to dozens of species of moss, all glistening with rainfall.

Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis)

The salmonberry canes, on which the leaves and fruits grow, may reach 7 feet tall; they grow in dense thickets. The juicy raspberry-like fruits may be either orange or red at maturity; the time of ripening is late June through August. The favorite fruit of Alaska’s bears.

Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis)

Alaska’s state tree grows 150–225 feet high, up to 8 feet in diameter, and can live 500–700 years, although few make it that long. A combination of storms and very shallow soil tend to knock down most spruce within a couple of hundred years. The leaves are dark-green needles, about an inch long, pointing up, and they cover all the branches. At the top of the tree, light orange-brown cones develop. Spruce buds were used by early mariners for making beer, and Sitka spruce wood, now mostly used for making guitars, has always been one of the great treasures of the forest: the Russians used it for the beams and decks of ships built in their Sitka boat works, and for house building. During World War II, it was used for airplanes—the British made two fighter planes from Sitka spruce, and it’s the namesake wood of Howard Hughes’s Spruce Goose.

Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla)

Western hemlocks grow to a maximum of about 150 feet, and they’re thin, with a large tree only about 4 feet in diameter. Maximum lifespan is about 500 years, but few make it that long. The leaves are wider and lighter green than spruce leaves, pointing down, and the cones are a darker brown. Bark is a gray-brown. Western hemlock loves to come back in clear-cut areas, a fact that has changed the natural balance in some logged parts of Southeast Alaska.

Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata)

Western red cedar covers a wider range, from sea level to about 3,000 feet in elevation. The leaves are much like those of the yellow cedar, but more yellow-green in color. The cones are oval, as opposed to the round yellow cedar cones. Red cedar was the treasure species for Southeast Natives, who used it for everything from house building to making clothes.

Rain Forest Fauna

Making their home in the spaces between the trees of the rain forest are bears, moose, wolves, and deer. Watch estuaries for seals, streams for salmon, and keep an eye on the sky for eagles, ravens, crows, and herons.

Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)

With a wingspan of 6 to 8 feet and weighing as much as 20 pounds, these grand Alaska residents are primarily fish eaters, but they will also eat birds or small mammals. As young birds, they’re all brown, with the characteristic white head developing in adulthood. The world’s largest gathering of bald eagles occurs in Southeast Alaska each winter, along the Chilkat River near Haines. Bald eagles build the biggest bird nests in the world, weighing up to 1,000 pounds.

Black Bear (Ursus americanus)

Black bears are found on nearly every large island in the Southeast, throughout South Central Alaska, and in coastal mainland areas. They average 5 feet in length and weigh from 150 to 400 pounds. A good-size black bear is often mistaken for a brown bear because black bears are not necessarily black: they range from black to very light brown. Black bears have a life expectancy in the wild of about 25 years.

Brown Bear (Ursus arctos)

Brown bears, or grizzlies, are rarer and considerably larger than their black cousins. In Southeast’s rain forest, browns are most often seen on Admiralty Island, where they outnumber the human population; near Wrangell; and on Baranof, Chichagof, and Kruzof islands. Southeast’s brown bears run 7 to 9 feet, with males ranging from 400 to 1,100 pounds; if they live in a place with a rich fish run, they can grow to 1,500 pounds. Brown bears range in color from a dark brown to blond. The easiest way to distinguish them is by the hump on their back, just behind the head. They have a life expectancy of about 20 years in the wild.

Sitka blacktailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus sitkensis)

The Panhandle’s rain forest is the primary home of this deer, though it has been transplanted to Prince William Sound and Kodiak. Dark gray in winter and reddish brown in summer, it’s smaller but stockier than the whitetails found in the Lower 48. The deer stay at lower elevations during the winter, then move up to alpine meadows in summer.

Experiencing a Rain Forest

Any trip into Southeast Alaska puts you in the rain forest. Even in a landscape this beautiful there are some highlights.

Animal Watching

At Pack Creek on Admiralty Island, brown bears fish for spawning salmon. To get here, you can fly by air charter or take a boat from Juneau. Another option is near Wrangell; Anan Bear Reserve is at one of the few streams in the world where black and brown bears share the waters, fishing at the same time.

By Sea

The Alaska Marine Highway runs ships to every major town—and many of the smaller ones—in Southeast Alaska. The local equivalent of a bus service, AMH ships go into small channels, offering views of rain-forest slopes, forays into quiet bays and inlets, and perhaps the best look at how the landscape was carved by glaciers.

Flightseeing

Misty Fiords National Monument, south of Ketchikan, is one of the most beautiful areas of drowned fjords and pristine rain-forest habitat in the Southeast. Covering more than 3,500 square miles, Misty Fiords is the Southeast’s most popular flightseeing destination (though the monument is also laced with hiking trails and is perfect for kayaks).

Hiking

The Tongass has hundreds of miles of hiking trails, from short loops to ambitious multiday expeditions. Rain gear and a proper understanding of bear safety are essential. Hiking gives you a chance to have the forest to yourself, and lets you appreciate its intricacies, from tiny lichen to the towering canopy. This might just be the best way to understand the rain forest.

Rain Forest Top Guides

Bear-Viewing

All of the Anan Wildlife Observatory–authorized guide companies we recommend are excellent, but a standout is Alaska Vistas (907/874–3006 or 866/874–3006 | www.alaskavistas.com). Based out of Wrangell, Alaska Vistas offers highly accommodating trip-planning services, and its guides’ enthusiasm and respect for the bear experience makes your trip unforgettable. You can also choose from jet-boat tours up the Stikine, kayaking and canoe trips, and guided hikes, all of which come with that special Alaska Vistas touch.

Natural History

An excellent guide to the rain forest of the Southeast can be found quite easily and with minimal expense (once you get yourself to Juneau, that is): the docents at Glacier Gardens (7600 Glacier Hwy. | 99801 | 907/790–3377 | www.glaciergardens.com) are Native Alaskans and will teach you more about the local forest than you’re going to learn anywhere else.

Hiking

If you have any inclination to go hiking, try to fit it in with Packer Expeditions (907/983–3005 or 907/983–2544 | www.packerexpeditions.com), out of Skagway. It offers trips on the famous Chilkoot Trail as well as on local trails popular with the area’s residents, both human and ursine. Packer Expeditions also offers many ways to combine rain-forest hiking with other modes of locomotion, such as a helicopter ride, or a ride on the White Pass & Yukon Route Railroad (either one way or, for accessing more remote trailheads, round-trip). It’s a good choice if you’re eager to combine rain-forest and glacier ecozone experiences; one trip offers a hike up to the Laughton Glacier, and a different itinerary will bring you there partially by train and leave time for hiking on the glacier itself.

If you have sufficient bear-safety experience and wilderness knowledge, the Alaska Travel Industry Association (www.travelalaska.com), or ATIA, provides fantastic guidance on exploring the rain forests of Southeast.

Interior Forests

Rain forests dominate the southern coast of Alaska; but move inland, and a different kind of forest appears. Much of the interior is covered by thick spruce and birch forests, trees that can grow in harsher conditions—temperatures in the middle of the state can hit 100°F in summer and –50°F in the winter—than their coastal counterparts.

The soil is usually deeper here, but as much as 75% of the region that this taiga, or boreal forest, covers may have patches of permafrost—soil that never thaws. The plants also have to cope with a very short growing season; in most areas, the entire season from beginning to end spans no more than four months.

The interior forest is dominated by conifers—spruce, pine, fir—but also has plenty of broadleaf trees, such as birch and aspen. Fires are a regular occurrence throughout the region, usually caused by lightning strikes, and they can quickly burn out thousands of acres. Although this may seem alarming (and no doubt is to anyone whose home is near a burning forest), these fires are actually beneficial to the long-term health of the forest. They serve to clear out dead trees and underbrush, and also open up the canopy to allow for new growth.

Taking advantage of the resources within these forests is a wide variety of animals, from bears and moose all the way down to the tiny vole. Like the trees, these animals have to know how to survive in dramatic temperature changes; come winter, many hibernate, but others find ways to scrape for food beneath the snow and ice. Still others rely on migration to stay warm; perhaps as many as 300 bird species spend part of the year in the forests, but only a couple of dozen have found ways to winter here.

Covering the vast, broad center of Alaska, the interior forests cover as much as 80,000,000 acres; include the parts of the state where the forests are patchier, and you get up to 220,000,000 acres of interior forest—an area bigger than Texas and Oklahoma combined. These forests are the heart of Alaska.

Safety

So much of Alaska’s interior forests are roadless wilderness that rivers often serve as the best avenues for exploring them. However, rivers can be dangerous. River difficulty is ranked Class I through Class IV; only very experienced river runners should attempt anything above Class II on their own. If you’re traveling with a guide, research their safety record before you sign up.

Interior Forests Flora

Alaska’s interior forests aren’t as biologically rich as those in some areas of the state, but what they lack in diversity, they more than make up for in beauty and sheer vastness.

Alaskan paper birch (Betula neoalaskana)

A near relative of the more common paper birch (Betula papyrifera) and once commonly used by Natives for making birch-bark canoes, the Alaska subspecies grows up to 45 feet tall. It’s noted for having a narrow trunk and leaves about 3 inches long. The bark is dark red-brown when the tree is young, and turns a delicate white or pinkish as the tree ages; like that of its relative, the bark peels off in layers, although not quite as well as does the paper birch. In Alaska, the Alaskan paper birch grows in bogs and on poorly drained soils, and is commonly mixed in with black spruce trees. It’s one of the iconic features of the landscape of the Interior, often the subject of art from the region.

Alder (Alnus)

Common throughout central Alaska, alders range from trees (such as the Sitka alder, one of the first species to come back in a disturbed area, such as after a fire or intensive logging) to bushes (like the mountain alder, which grows along streams and in other areas with wet soil). Mountain alder, despite being classified as generally shrublike, can actually grow up to 30 feet high, with thin trunks of about 6 inches in diameter. Sitka alder can grow to about the same height, but with a slightly thicker trunk. Both types have saw-toothed leaves with parallel veins and smooth gray bark. It’s difficult to tell them apart when they’re young.

Tall fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium)

The fireweed is among the first plants to reinhabit areas that have been burned out by wildfire, and in the proper conditions it grows well. Found throughout much of Alaska, it’s a beautiful plant, with fuchsia flowers that bloom from the bottom to the top of stalks; it’s said that the final opening of flowers is a sign that winter is only weeks away. Spring fireweed shoots can be eaten raw or steamed, and its blossoms can be added to salads. A related species is dwarf fireweed (Epilobium latifolium), which is also known as “river beauty” and tends to be shorter and bushier.

Interior Forests Fauna

With all that space, there’s plenty of space for animals. From the rarely seen wolverine to the very common moose, the heart of the state has room for everything.

Common Raven (Corvus corax)

A popular character in Alaska Native stories, the raven is both creator and trickster. Entirely black, with a wedge-shape tail and a heavy bill that helps distinguish it from crows, the raven is Alaska’s most widespread avian resident. Ravens are also the smartest bird in the sky; scientists have shown that they are capable of abstract reasoning and teaching other ravens their tricks. They’re among the most articulate of birds, with more than 50 calls of their own, plus the ability to mimic almost any sound they hear.

Lynx (Lynx canadensis)

The lynx is the only wild cat to inhabit Alaska. It’s a secretive animal that depends on stealth and quickness. It may kill birds, squirrels, and mice, but the cat’s primary prey is the snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), particularly in winter; its population numbers closely follow those of the hare’s boom–bust cycles.

Moose (Alces alces gigas)

The moose is the largest member of the deer family; the biggest bulls stand 7 feet tall at the shoulders and weigh up to 1,600 pounds. Bulls enter the rut in September, the most dominant engaging in brutal fights. Females give birth to calves in late May and early June. Though most commonly residents of woodlands, some moose live in or just outside Alaska’s cities.

Wolf (Canis lupus)

The largest and most majestic of the Far North’s wild canines, wolves roam throughout Alaska. They form close-knit family packs, which may range from a few animals to more than 30. Packs hunt small mammals, birds, caribou, moose, and Dall sheep. They communicate through body language, barks, and howls.

Wolverine (Gulo gulo)

Consider yourself lucky if you see a wolverine, because they are among the most secretive animals of the North. They are also fierce predators, with enormous strength and endurance. Denali biologists once reported seeing a wolverine drag a Dall sheep carcass more than 2 miles; they can run 40 mph through snow. Though they look like very small bears, wolverines are in fact the largest members of the weasel family.

Experiencing Interior Forests

The interior forests are big enough you could spend years exploring and never see the same area twice. Or you could just go for a nice day hike. Whatever adventure you’re after, you’ll find it here.

Canoeing and Kayaking

It can be a lot easier to see the forest from a river than from the inside. Alaska’s premier long canoe trip is along the Yukon River, starting across the Canadian border in Dawson City and taking out at Eagle. A wilder option is white-water kayaking the Fortymile, from Chicken, though this is definitely not for the faint of heart. Another popular float trip is one that takes you down the Nenana, through Fairbanks. Guides are available on all these rivers and more; no one unfamiliar with Alaskan conditions should try these trips alone under any circumstances.

Dog Sled

For those hardy enough to come to Alaska in winter, dog-sled tours offer the most classic way to see the state: behind a pack of howling dogs who are having the time of their lives, running as fast as they can. Trips range from short runs through forest loop trails to multiday adventures, and all you need are warm clothes and the ability to hang on tight.

Hiking

Nearly every town in the central forests has hiking trails lacing the woods around it. Especially popular are Angel Rock, Granite Tors, and Ester Dome hikes, all near Fairbanks. For something longer, try the Kesugi Ridge Trail, near Talkeetna; it’s a two- to four-day alpine traverse along a beautiful ridgeline with possible views of Denali if the weather’s right.

Interior Forests Top Guides

Hiking

For a backcountry hiking experience in Wrangell–St. Elias National Park, contact St. Elias Alpine Guides (888/933–5427 | www.steliasguides.com), based in McCarthy. The guides here will facilitate anything from a few hours in the woods to a monthlong foray into the wilderness. This is the only company contracted by the Park Service to run tours of historic Kennicott buildings ; if you have any interest in Alaska’s history, it’s a very compelling way to get out into the country.

River Sports

St. Elias Alpine Guides also leads rafting trips through its river-travel-focused division, Copper Oar (800/523–4453 | www.copperoar.com). Also based in McCarthy, it will outfit and guide you along pristine waters into the heart of the wilderness.

Fishing trips are a great way to get out on the water, too. The Kenai Peninsula might be the best spot to combine fishing with boreal forest scenery. Hi-Lo Charters (www.hilofishing.com), in the town of Kenai, runs fishing trips from its home base on the Russian River; this fishing lodge scores high in all the important ways—excellent service, knowledgeable guides, comfortable quarters—but the custom-built, sheltered, outdoor grilling area is a great perk.

Out of Fairbanks, a simple but highly educational and entertaining way to experience the surrounding landscape is to simply take a ride on the Riverboat Discovery. Onboard naturalists are enthusiastic and highly knowledgeable. If you prefer to go it alone, Alaska Outdoor Rentals and Guides (Pioneer Park Boat Dock, along Chena River next to Peger Rd. | 99708 | 907/457–2453 | www.2paddle1.com) can rent you gear and facilitate drop-offs and pickups along the lower Chena River in Fairbanks or other local waterways.

Dog-Sled Tours

Sun Dog Express Dog Sled Tours (907/479–6983 | www.mosquitonet.com/~sleddog), out of Fairbanks, runs winter and summer tours (weather permitting), and can accommodate whatever level of involvement you’re looking for—from simple demonstrations to a full-tilt three-day mushing camp. Another great winter option in the Fairbanks area is Chena Dog Sled Tours (907/488–5845 | www.ptialaska.net/~sleddogs), out of Two Rivers (near Chena Hot Springs).

Tundra

At first glance the tundra might not look like very much: a low carpet plants, few more than shoelace high. But take a closer look and you’ll realize you’re encountering an ecozone every bit as fascinating and diverse as the showier forests, glaciers, and intertidal zones elsewhere in the state.

Tundra stretches throughout the Bush in Alaska, with patches as far south as Denali National Park. Characterized by dwarf shrubs, sedges, grasses, mosses, and lichen, tundra occurs in places where the temperatures are low (so it makes sense for plants to hug the ground) and the growing season is short—some prime tundra spots might not get more than a few weeks of summer.

Arctic tundra has roughly 1,700 species of plants growing in it; a single square foot of tundra might contain several dozen species, from saxifrage to bear berry to arctic rose. It does make for a hard place for most animals to build homes; mammals that depend on the tundra tend to cover a fair chunk of territory in their search for food, be they musk ox, lemmings, or caribou.

Throughout most of the tundra zone in Alaska the ground beneath is permafrost—permanently frozen soil—and too hard for many plants to put down deep roots. Permafrost happens when the average temperature of an area is below freezing, and it comes in both continuous—an entire region’s soil encased in ice at a more or less uniform depth—and discontinuous—where some places get warm enough to thaw.

Tundra is extremely fragile; the short growing season means even the slightest damage can take years to recover from. Footprints across tundra might not fade for decades. But at the same time, tundra is extremely resilient, able to thrive in the most extreme conditions, regrow after a herd of 100,000 caribou have crossed over it, nibbling, and emerge ready again to help feed the millions of birds who depend on tundra areas as part of their migration route. The closer you look, the more you’ll find in the tundra.

Safety

Alaska has at least 27 species of mosquito, and in summer the biomass of the mosquitoes can actually outweigh that of the caribou. The bite of a mosquito from up this way can be enough to raise welts on a moose. While the mosquitoes provide a huge base of the food chain for tundra birds, small mammals, and fish, they can cause serious discomfort for travelers. Apply DEET, wear long sleeves, and consider traveling with a head net if you’re hiking.

Tundra Flora

The tundra is a close-up territory: the longer and closer you look, the more you’ll see. Take it on its own terms and you’ll find a whole world to discover.

Blueberry (Vaccinium)

A favorite of berry pickers, blueberries are found throughout Alaska, except for the farthest northern reaches of the Arctic. They come in a variety of forms, including head-high forest bushes and sprawling tundra mats. Pink, bell-shape flowers bloom in spring, and dark-blue to almost-black fruits begin to ripen in July or August, depending on the locale. But the tastiest are the tundra blueberries, which almost carpet the ground in some places; this is the true flavor of the midnight sun, and you’ll want to factor in time on any hikes for plenty of berry-eating breaks.

Reindeer lichen (Cladonia rangiferina)

A slow-growing white lichen that grows in shapes somewhat reminiscent of reindeer antlers, or a small sea coral, reindeer lichen come up in a tangle of branches. Another reason for its name: it is a favored food of both reindeer and caribou (it’s sometimes called caribou moss). It’s also used traditionally in medicinal teas and in poultices for arthritis; nutritionally there’s not much to be gained from eating it, but if you did it would feel sort of like chewing soft toothpicks.

Saxifrage (Saxifraga razshivinii)

One of the most characteristic plants of the tundra, able to grow in even the thinnest soil (the name translates to “stone breaker”), saxifrage is close to the ground, tends to grow in a kind of rosette shape, and sends up small, five-petaled flowers, which are usually white, but may also be red or yellow. Saxifrage is one of the first bits of color that show up on the tundra in spring, making it a particular favorite of many who live up here during the (very long, very cold) winters.

Willow (Salix)

An estimated three dozen species of willow grow in Alaska. Some, like the felt-leaf willow (Salix alaxensis), may reach tree size; others form thickets. In the tundra, what you’ll find are others, like the Arctic willow (Salix arctica), that hug the ground; a plant an inch tall might be 100 years old. Whatever the size, willows produce soft “catkins” (pussy willows), which are actually columns of densely packed flowers without petals.

Tundra Fauna

The tundra is perfect for animal spotting.

Arctic Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus parryii)

These yellowish-brown, gray-flecked rodents are among Alaska’s most common and widespread mammals. Ground squirrels are known for their loud, persistent chatter. They are easiest to spot standing above their tundra den sites, watching for grizzlies, golden eagles, weasels, and anything else after the average 2,000 calories an arctic ground squirrel provides.

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus)

Sometimes called the “nomads of the north,” caribou are long-distance wandering mammals. The Western Arctic Caribou Herd numbers nearly 500,000, while the Porcupine Caribou Herd has ranged between 70,000 and 180,000 over the past decades. They are the only members of the deer family in which both sexes grow antlers. Caribou might migrate over hundreds of miles between summer and winter grounds, a feat eased by the tendon in their ankle that snaps the foot back into place with each step with an audible click.

Musk Ox (Ovibos moschatus)

The musk ox is an Ice Age relic that survived partly because of a defensive tactic: they stand side by side and form rings to fend off predators such as grizzlies and wolves. Unfortunately, that tactic didn’t work very well against humans armed with guns. Alaska’s last native musk oxen were killed in 1865. Musk oxen from Greenland were reintroduced here in 1930; they now reside on Nunivak Island, the North Slope of the Brooks Range, and in the Interior. The animal’s most notable feature is its long guard hairs, which form “skirts” that nearly reach the ground. Inupiats called the musk ox oomingmak, meaning “bearded one.” Beneath those coarser hairs is fine underfur called qiviut, which can be woven into incredibly soft, warm clothing.

Sandhill crane (Grus canadensis)

The sandhill’s call has been described as “something between a French horn and a squeaky barn door.” Though some dispute that description, most agree that the crane’s calls have a prehistoric sound. Scientists say the species has changed little in the 9 million years since its earliest recorded fossils. Sandhills are the tallest birds in Alaska; their wingspan reaches up to 7 feet. The gray plumage of adults is set off by a bright red crown.

Experiencing Alaska’s Tundra

Get out and spend some time in this landscape and discover just how big the world of the tundra really is.

Drive (or be Driven)

With a road system that leads into nearly uninhabited parts of Alaska, Nome offers the perfect jumping-off point for tundra fans. It’s also the only town in Alaska where you are likely to spot musk oxen within a few miles of buildings. You can do this on your own, but many people prefer the extra knowledge gained by doing this with a guide. Hiring a guide also supports the local economy and helps promote preservation of Native knowledge.

Hike

The easiest place to go for a tundra hike is in Denali National Park: away from the mountains, the park contains huge swatches of tundra, where you might also see bears, moose, and caribou. The best time is in early autumn, when the colors start to change; that’s when “the ground looks like a giant bowl of Captain Crunch.” However, so long as you’re properly equipped against mosquitoes, summer (when visitors are most likely to be here) is also a fine time to explore the tundra on foot.

Raft

Several of Alaska’s great arctic rivers cut through tundra: the Hulahula heads north through the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge, the largest patch of undisturbed land left in the United States. Another good option is the Kongakut, which rises in the Brooks Range and then flows towards the arctic plain where the caribou calve. Either river offers a week or more of the ultimate wilderness experience.

Tundra Top Guides

A trip with Nome Discovery Tours (907/443–2814) is maybe one of the most memorable experiences you could have in Alaska’s tundra. Touted as Alaska’s best tour guide by many who have had the pleasure of being shown around the tundra by him, former Broadway showman Richard Beneville has lived in the Far North for over 20 years and has developed an intimate knowledge of the land and its history. One tour includes Safety Sound, a tidal wetland about 30 miles out of Nome that has some fantastic birding. Another includes a tundra walk on which Richard serves as tundra-savvy interpreter.

The best guide companies to the remotest places in Alaska tend to be owned and operated by those who have lived here for a while, and Kuskokwim Wilderness Adventures (907/543–3900 | www.kuskofish.com) is no exception. Local expert Jim McDonald does much of the guiding for this family-owned operation. Several birding and fishing tours are available. Spend a weekend fishing at its Kisaralik Camp, 80 miles north of town by riverboat—it’s a great way to spend several days on some of the remotest tundra in the world without forgoing modern conveniences, like a shower.

Tour Bus

Not everyone will have the time to get out to the far Northwest; luckily, there’s tundra to be found much closer to one of the main attractions in Alaska: Denali National Park. Take any of the guided bus tours in Denali (except for the shortest which doesn’t get out of the forest). Since you’re on a bus, you don’t get the full benefit of seeing it up close and personal except for photo stops, but it’s still a lot of reward for very little effort.

Raft

Like the forests of the interior of the state, the tundra is a great place for a rafting trip. Arctic Treks (907/455–6522 | www.arctictreksadventures.com) runs top-notch rafting trips (and also hiking, bird-watching, and photography tours) to the Brooks Range, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and Gates of the Arctic National Park, among other locations. It’s been in operation for over 30 years, and guides have deep knowledge of the tundra and its wildlife.

Ice

Ice is its own ecosystem in Alaska, and a vital one, as well as being the part of the state’s environment that is at the most risk. Ice covers roughly 5% of Alaska—from the southernmost tidewater glacier at LeConte, through the Juneau Icefields, past Glacier Bay, and up to the Malaspina Glacier, the largest nonpolar glacier in the world.

Glaciers form when more snow falls than melts. If this keeps up year after year, the new snow presses down on the old snow, compacting it, turning it to ice. And after a time it all grows heavy enough to start moving, flowing with the landscape and the call of gravity.

Historically, nothing has shaped Alaska more than ice. A quick look at the mountains in Southeast Alaska offers ready proof: mountains under about 3,500 feet are rounded; those above, sharp and jagged. Why? Because during the last ice age, that’s the height at which the glaciers came through, smoothing everything.

But it’s not just that glaciers carve the landscape. They also rejuvenate it; a walk toward a glacial face is like walking backwards in time. Glaciers leave behind them the ultimate clean slate, a chance for nature to move back in and regrow from scratch.

Glacial winds, known as katabatic winds, carry seeds for hundreds of miles, allowing plant species to spread; the freshwater held in Alaska’s ice feeds countless rivers, streams, and lakes, supporting everything from the incredibly delicate freshwater snails of the Brooks Range to the spawning grounds of the biggest king salmon.

And it’s all under threat. Over the past decades nearly every glacier in Alaska has gotten smaller. Glaciers that used to be easily visible—Worthington, Exit, Portage—have almost disappeared from sight. Estimates are that Alaska has nearly 100,000 glaciers, but that number will likely change in the future.

Safety

Glacier terrain includes a mix of ice, rock debris, and often-deep surface snow; sometimes frigid pools of meltwater collect on the surface. Watch out for glacier crevasses; sometimes hidden by snow, these cracks in the ice may present life-threatening traps. Glacier travel should be attempted only after you’ve been properly trained. If you haven’t been taught proper glacial travel and crevasse-rescue techniques, hire a backcountry guide to provide the necessary gear and expertise.

Ice Flora

As a general rule, plants don’t grow on ice, but Ruth Glacier has a fully mature forest growing on it. Still, for the most part, about the only life found on the ice might be some bacteria and algae, and a few lichen growing on rocks the ice is carrying along. The interest lies at the face of the glacier, and in the progression of plants leading away from it.

Algae

At least seven species of algae have been found on Alaska’s glaciers. The most common include Chlamydomonas nivalis, technically classified as a green algae, which stains snow atop glaciers red when they bloom; and Ancylonema nordenskioldii, which is another green algae, and is perhaps the most common algae found on ice. Again, like the bacteria and the fungus, unless you know what you’re looking for, you won’t see much.

Bacteria

A close look on Alaska’s glaciers might uncover some Rhodobacteracae, some Polaronomas, and Variovorax, and a few dozen more species of bacteria. For most people, all of these are going to either be invisible, or look like small smudges on the ice.

Lichen

A bit more showy than the bacteria, lichen tend to grow near glacial faces; in fact, tracking lichen in moraines is a way scientists date glacial movement. A combination of a fungus and a bacteria, lichen are among the first noticeable things to grow near a glacier. Lichen get their nutrition from air and water, digging rootlike structures called rhizomes into the rocks where they grow, eventually breaking them down and turning them into soil. Favored among glacier scientists are Rhizocarpon geographicum (green and blotchy); but you’ll also spot some that look like burned ash, some that look like branches, and, if the air is really clear, some that are orange. In all, Alaska has more than a thousand species of lichen, and hundreds can show up around glaciers.

Spruce Forest (The Ruth Glacier Exception)

Although most of what grows on glaciers is nearly invisible, there is one exception. At the end of Ruth Glacier, which flows off Mt. McKinley, is a forest, growing atop the ice. Not the best place to be a tree: as the glacier moves (at a rate of about 3 feet a day), the trees at the edge get pitched into the river below.

Ice Fauna

Most animals can’t live on the ice—there’s nothing to eat. But living near the ice has some distinct advantages.

Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina)

Ice broken off the face of tidewater glaciers is a favorite place for seals to pup, to sunbathe, and most of all, to stay safe from orcas on the prowl. All those berg shapes confuse the orca’s sonar, making it a perfect place to be a seal. In Southeast Alaska, the easiest place to see them, they will be harbor seals, which grow to about 180 pounds. They’re covered with short hair, and are usually colored either with a dark background and light rings, or light sides and a belly with dark splotches. They can dive to 600 feet and stay down for more than 20 minutes, their heart rate slowing to 15–20 beats per minute, about a fourth of their heart rate when at the surface. The easiest way to tell a seal from a sea lion is by the ears: seals have no external ear structure.

Ice worm (Mesenchytraeus)

Robert Service described this animal in his poem “Ballad of the Ice Worm Cocktail,” where he wrote that they are “indigo of snout./And as no nourishment they find, to keep themselves alive/They masticate each other’s tails, till just the Tough survive./Yet on this stern and Spartan fare so rapidly they grow,/That some attain six inches by the melting of the snow.” He was very wrong. Pin-size, usually blue, black, or brown, and hard for even scientists to find, ice worms come to glacial surfaces only in morning and evening; they can actually melt at temperatures just a few degrees above freezing.

Orca (Orcinus orca)

Maybe the harbor seals are hiding from the orcas, but that doesn’t mean the orcas don’t view the ice edge as an open refrigerator door. Orcas, or killer whales—a term that has fallen out of favor with the politically (and taxonomically, as the scientific name translates to “one from the realms of the dead”) correct, as they are neither killers per se nor, since they’re really the largest member of the porpoise family, whales—can be more than 30 feet long, and the dorsal fin on a male can be as much as 6 feet high. At birth, orcas weigh roughly 400 pounds. A full-grown orca can weigh as much as 9 tons, and can swim 34 miles per hour; they can live as long as 80 years. Watch for the tall fin, the distinctive black-and-white markings, and size—Dall’s porpoises are also black and white, but are smaller than a newborn orca.

Experiencing Alaska’s Ice

What most people want to see in Alaska is a glacier. Luckily, there are plenty of them to explore.

Flightseeing

In the Southeast, helicopter tours to Mendenhall Glacier, an 85-mile-long, 45-mile-wide sheet of ice, just the tiniest finger of the 1,500-square-mile Juneau Icefields, provide fantastic views; most tours land on the ice for an up-close look. In South Central, trips over Ruth Glacier toward Mt. McKinley offer the best ice views.

Hiking

The Matanuska Glacier, at Mile 103 off the Glenn Highway (about a 90-minute drive northeast of Anchorage) is not only Alaska’s biggest nonpolar glacier, but also one of the easiest to get to, with readily accessible ice; however, the inexperienced should not consider going far without professional guides.

Kayaking

Some outfitters offer kayaking near glaciers and icebergs. The experience can be transformative. It can also be extremely dangerous; bergs can roll over and glaciers can calve at any moment. Be sure to go with an experienced guide and do exactly as he or she instructs.

Sailing

Glacier Bay is where most people get on boats to see calving glaciers (when big chunks of ice fall into the sea). Other options include Tracy Arm, near Juneau (smaller, but more dramatic); LeConte Glacier, between Wrangell and Skagway; or glacier cruises from Valdez and Seward. You’re hard-pressed to find a cruise in the Southeast that doesn’t put you within sight of a glacier. It can be dangerous to get too close to a glacier when cruising; you never know when it will calve and create a nasty wave before you can sail to safety.

Ice Top Guides

Glacier Cruises

Glacier-viewing cruises are extremely popular in Alaska, particularly in Prince William Sound. Of the plethora of operators these stand out for their commitment to good environmental stewardship, charismatic guides, and customer service.

Major Marine Tours (907/274–7300 or 800/764–7300 | www.majormarine.com), out of Whittier, runs excellent glacier-viewing tours into Prince William Sound. They visit at least two tidewater glaciers on each sailing and have an itinerary that is kind to those who are nervous about seasickness.

Kenai Fjords Tours provides a comfortable boat, a whole lot of glaciers, and excellent wildlife-watching along the way. You can see rain forest, mountains, glaciers, and the sea all at once. The route out for all trips to Kenai Fjords covers some open ocean that can be very rough at times; take the necessary seasickness precautions beforehand regardless of the weather.

From Southeast, Adventure Bound Alaska (907/463–2509 or 800/228–3875 | www.adventureboundalaska.com) will get you up close to the glacier in Tracy Arm, one of the most actively calving glaciers in Alaska.

If you have limited time, consider 26 Glacier Cruise (907/276–8023 or 800/544–0529 | www.phillipscruises.com), which travels 135 miles in 5 hours. You’ll head out of Whittier and see 26 glaciers from a comfortable reserved-seating catamaran. This is another smooth-ride standout; even those who are always seasick will be pleasantly surprised.

Flightseeing

Air Excursions (800/354–2479, 907/697–2375 outside Alaska | www.airexcursions.com) and Wings of Alaska (907/789–0790 | www.wingsofalaska.com) are top choices for glacier flights. Both have offices throughout the Southeast and can create custom flights. ERA Aviation of Era Alaska (www.eraalaska.com) can fly you via helicopter from Juneau or Skagway to various places, the cheapest and quickest (but no less dazzling) of which is the trip to Mendenhall Glacier.

Kayaking

Tongass Kayak Adventures (www.tongasskayak.com), out of Petersburg, leads kayaking trips to the icebergs of nearby LeConte Glacier, among many other worthwhile adventures.

The Mountains

An awful lot of Alaska lies a considerable way above sea level. The state is covered with mountains, from the relatively small peaks of Southeast Alaska—only a few much above 4,000 feet—to the highest point in North America, Mt. McKinley, at 20,320 feet above sea level.

The state’s mainland is divided by mountains: the Chugach range along the South Central coastline; the Alaska Range, which includes Mt. McKinley, close to the center of the state; and the Brooks Range, which divides the interior from the arctic coast. On the eastern edge of the state lies the Wrangell Range, which, with the St. Elias mountains north of Glacier Bay and stretching into Canada, offers more unexplored high peaks than any other area in the hemisphere. Lesser ranges include the Ogilvie, Kuskokwim, and Talkeetna mountains, as well as the Aleutian Range, which never gets very high, but offers dramatic views from the storm-tossed sea.

The higher the peak, the less that grows on it, but along the way to the top, mountains provide rich biodiversity, from the trees on their lower slopes to the alpine meadows along the way to the peak. The mountains also influence everything around them, creating weather patterns that spread out across the state; the main reason why so few people ever see the peak of Mt. McKinley is because the mountain makes weather, and the weather that mountains like most is clouds.

In the Coast Mountains in Southeast, the effect of altitude on weather is particularly dramatic: the east sides of the mountains are relatively dry (for a rain forest), getting only 100 or so inches of rain a year; some spots on the west sides of the mountains get as much as 300 inches of rain.

Once above the alpine meadow level, not a whole lot grows or lives in the mountains, but mountains have shaped everything in Alaska, from Native culture to wildlife migrations. They’re the birthplace of glaciers and the last truly unexplored edge of the state.

Safety

For many visitors the mountains here beg to be skied. However, unless you are knowledgeable about avalanche dangers, the best strategy is to hire a guide when exploring Alaska’s backcountry on skis. Be sure your guide has had avalanche-awareness training. Conditions can change quickly, especially in mountainous areas, and what begins as an easy cross-country ski trip can suddenly become a survival saga if you’re not prepared.

The Mountains Flora

Each mountain is its own complete ecosystem; what you’ll find depends on altitude, on exposure, on what other mountains are nearby.

Alpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa)

The alpine fir is a fairly large tree growing up to 150 feet tall, although more commonly around 60 feet, with a trunk around 3 feet in diameter. Branches are covered with needles about an inch long. Like ideal Christmas trees, the crown is very narrow, often only a single spike. Bark on young trees is smooth and gray, but roughens as the tree ages.

Avens (Dryas)

The avens is a low, evergreen, flowering plant (technically a subshrub) common in high alpine meadows, most frequently found in areas that were once glaciated. Usually growing in patches, avens have small leaves, and produce eight-lobed flowers with a yellow center. Avens is considered to be a member of the rose family.

Chocolate lily (Fritillaria lanceolata)

A high-alpine-meadow plant, the chocolate lily grows up to 4 feet high, with one to five rich, brown flowers coming off the central stalk. Leaves are broad and flat, shaped like spearheads. The chocolate lily usually blooms from mid-June to mid-July, and is characterized by a smell that is very distinctive; nicknames for the chocolate lily include outhouse lily, skunk lily, and dirty diaper.

Valerian (Valeriana sitchensis)

One of the most common alpine flowers in Alaska, valerian grows on stems that range from about a foot to 4 feet long. Leaves grow in pairs, leading up to beautiful flower clusters of white, five-lobed flowers with long stamens shooting above the petals. Valerian has a sweet smell to it, and can be used for helping ease insomnia. While not native to Alaska, it’s become an important part of the Alaskan landscape.

The Mountains Fauna

For many animals, up is the way to go to be safe from most predators. Changing altitude is also like changing seasons—up leads to cooler weather.

Dall Sheep (Ovis dalli dalli)

One of four wild sheep to inhabit North America, the white Dall is the only one to reside within Alaska. Residents of high alpine areas, the sheep live in mountain chains from the St. Elias Range to the Brooks Range. Though both sexes grow horns, those of females are short spikes, while males grow grand curls that are status symbols displayed during mating season.

Golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos)

The bald eagle is mostly a coastal species in Alaska; golden eagles prefer the interior, especially around Denali and the Brooks Range. Characterized by the golden feathers on their head and neck, golden eagles have wingspans of 6 to 7 feet, and can weigh up to 12 pounds, with females much larger than males. They feed on squirrels, hares, and small birds, but they’ve also been known to occasionally attack larger animals, such as Dall sheep lambs. A single eagle might hunt over a territory of more than 60 square miles.

Marmot (Marmota broweri)

Alaska’s biggest rodent, marmots are common in the Brooks Range, where they live communally in scree where they can hide easily from predators. Browsing on pretty much anything that grows at that altitude, a marmot can grow to 2 feet in length and weigh 8 pounds or more.

Mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus)

Living on the high peaks, favoring rocky areas so steep that any predator would slip and fall, mountain goats live in the arc of coastal mountains from roughly Anchorage all the way down through the Panhandle. An adult male goat weighs 250–350 pounds, with females running about 40% smaller. Goats can live up to 18 years, although 12 is the high end of average. They feed on the high alpine plants—grasses, herbs, shrubs—and then in winter will eat whatever is available, favoring blueberry plants, hemlock, and lichens.

Experiencing the Mountains

Alaska has more big mountains than the rest of the country combined.

Flightseeing

Unless you feel like spending a month or so climbing, the best way to see Alaska’s peaks is by plane, and the best place to do that is in Denali. Flightseeing trips leave from Talkeetna; the best travel up Ruth Glacier, into the Great Gorge—an area of dramatic rock and ice—and up around the summit of Mt. McKinley. Although summit is often hidden in clouds, it’s still the best ride in Alaska.

Horseback

Encompassing more than 13 million acres of mountains, glaciers, and remote river valleys, Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve is wild and raw with so many big mountains that a lot of them don’t even have names. There’s no better way to absorb the enormity and natural beauty of this region than on horseback. Centuries-old game trails and networks blazed and maintained by contemporary outfitters wind through lowland spruce forests and into wide-open high-country tundra. From there, horses can take you almost anywhere, over treeless ridgelines and to sheltered campsites on the shores of scenic tarns.

Skiing

Alyeska Resort, located 40 miles south of Anchorage in Girdwood, is Alaska’s largest and best-known downhill ski resort. A new high-speed quad lift gets you up the mountain. The resort encompasses 1,000 acres of terrain for all skill levels. Ski rentals are available at the resort. Local ski and snowboard guides teach classes and offer helicopter-ski and -snowboard treks into more remote sites in the nearby Chugach and Kenai ranges. You probably won’t see much wildlife, but you’ll see a lot of mountain.

The Mountains Top Guides

Flightseeing

There’s no question that the top mountain-oriented activity in Alaska for most visitors is flightseeing in Denali National Park. One of the top companies to go with is K2 Aviation, out of Talkeetna. It provides thoroughly narrated tours that vary by length and route; we highly recommend going on the longest (and thus most expensive) one you can afford. Most people agree that the flight that takes you up over the top of McKinley itself is the best (you guessed it: it’s also the priciest).

K2 Aviation is owned by Rust’s Flying Service (907/243–1595 or 800/544–2299 | www.flyrusts.com), based in Anchorage, so even if you can’t make it up to Talkeetna by land, Rust’s can help you arrange a tour from your Anchorage base. If you prefer not to head north, you can take a trip out to the Brooks Range and the mountainous Harding Icefield and Kenai Fjords National Park, among other places.

Hiking

If you’re fit and want to immerse yourself in the mountains, consider a trip with Arctic Treks (907/455–6502 | www.arctictreksadventures.com), based in Fairbanks. You don’t need experience in the backcountry to go on the trips, and the company is very highly recommended.

Horseback

Horseback riding is the unsung hero of mountain travel in Alaska; in the warmer months, there’s hardly a more pleasant way to travel. Chena Hot Springs Resort (907/451–8104 | www.chenahotsprings.com), east of Fairbanks, can take you out on guided horse treks out on the trails and up into the mountains. If you won’t have time to travel to the Fairbanks area, consider a guided ride with Alaska Excursions (907/983–4444 | www.alaskaexcursions.com), based in Skagway; guides lead very good tours in a more conveniently located mountain landscape.

Mountaineering

While serious climbing isn’t for everyone, if you’re fit and not afraid of heights, Alaska is both a top destination for the pros and a great place for those interested in the sport to try their hand. Alaska Mountain Guides (907/766–3366 or 800/766–3396 | www.alaskamountainguides.com) has offices all over the state and is especially strong in the area of helping first-timers feel comfortable with the sometimes vertigo-inducing sport.

The Sea

The most philosophically accurate maps of Alaska are perhaps the nautical charts: they show the sea, in great detail, and only sketch in a few features on land. Anybody who has done much travel in Alaska understands why. Travel on land is arduous. Travel in a boat, unless the weather gets you, is sheer joy.

Alaska’s coastline—longer than that of the rest of the United States combined—and adjacent waters range from the deep and smooth inlets and bays of Southeast Alaska to the huge, shallow, and wild waters of the Bering Sea.

The ocean influences almost everything in Alaska, from how people live to the weather they encounter. Fishing has always been one of the state’s biggest industries since the Russians who settled here introduced the concept, and fish and other sea creatures had been important sources of food and materials for coastal communities for thousands and thousands of years before that (in fact, they still are).

And the health of the sea influences not just the adjacent coastal areas but fishing returns hundreds and hundreds of miles inland; if not enough salmon survive in the sea long enough to make it back to the mouth of their home river, it follows that a reduced amount will make it up the length of those rivers to spawn. Subsistence hunters deep in the Brooks Range can face hardship, as well as bears who depend on spawned-out salmon for much of their diet.

Perhaps even more compelling a reason to travel here: the sea is simply where some of Alaska’s most beautiful, graceful, dramatic animals spend their time. Whether it’s rafts of birds covering a dozen acres of sea off the Aleutians, or the slow arc of a whale’s back in Southeast, the sea is the center of Alaska’s life. However you travel through it, doing so with a knowledgeable guide who can help you better understand what you encounter will increase your enjoyment exponentially.

Safety

If you’re going to get out onto the water by self-propelled means—a kayak, canoe, or raft—go with a guide; a reputable one will ensure weather and tide conditions align in the chosen paddling spot for the smoothest ride possible (or roughest-while-still-safe, in the case of rafting).

Only consider going it alone if you have serious endurance-paddling experience under your belt and know what information to gather and what equipment to bring to avoid a dangerous situation.

The Sea Flora

Most people go to the beach looking for animals, but there’s no shortage of things for plant lovers to see, either. Some of the state’s most weird and wonderful living organisms can be found here.

Bull kelp (Nereocystis)

Probably the most common seaweed found on Alaska’s beaches, bull kelp is dull brown and has a bulb at one end of its otherwise long, whiplike structure. That’s right: snap it just so and it will crack like a whip. Or you can cut the bulb in half and blow the whole thing like a trumpet. One of the fastest growing plants in nature, most strands of bull kelp are around 8 to 15 feet long. If you’re kayaking and are feeling puckish, it’s generally safe to pick a little (just make sure it looks healthy) and nibble it right there. Some people also bring it home and fry it or put it in a salad.

Eelgrass (Zostera marina)

Common all along the Alaskan coast, eelgrass can grow up to 6 feet (although it usually doesn’t in the short Alaska growing season). Thin, brown, and with roots that are covered with fine hairs, it’s a perfect place for spawning herring to lay their eggs. The largest patch of eelgrass in the world is in Bristol Bay, off the west coast of the state (the patch is in Izembek Lagoon and stretches across roughly 34,000 hectares at last measure).

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

One of the first plants to come up on beaches and along glacial moraines, horsetails look just like their name, if horses had bushy green tails with segments kind of like bamboo. They might grow to a couple of feet tall, and can have a cone, sort of like a pinecone, for spores. Traditionally, it’s used for bladder or kidney problems, and it can also serve as a good natural solution for certain soil moisture imbalances.

Salix

Salix include willows and several hundred other species of trees. However, along Alaskan beaches, what you are most likely to see are Salix hookeriana, or Dune willows, which can have yellow, green, or brown flowers. They like to grow on wet soil and in coastal meadows, often right near spots you might be near while fishing, wildlife-watching, cruising, or kayaking.

The Sea Fauna

Alaska’s seas are among the biologically richest in the world—which is why the whales all come here to eat. For things with fins and flippers, this is paradise.

Horned Puffin (Fratercula corniculata)

Named for the black, fleshy projections above each eye, horned puffins spend most of their lives on water, coming to land only for nesting. They are expert swimmers, using their wings to “fly” underwater and their webbed feet as rudders. Horned puffins have large orange-red and yellow bills.

Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)

Humpbacks are most commonly seen in the Southeast. Humpback whales grow to 50 feet, but most are closer to 40, weighing up to 80,000 pounds. They are distinguished by the way they swim and their shape at the waterline: their back forms a right angle as they dive. Whales do not generally show their tails above water unless they are sounding or diving deep. Baleen whales, humpbacks feed on krill and plankton, using the baleen to filter their food from the sea water. Most of Alaska’s humpbacks winter in Hawaii, but there are a couple of small year-round populations, most notably near Sitka.

Salmon

Alaska has five species of salmon: pink (humpie), chum (dog), coho (silver), sockeye (red), and the king, or Chinook. All salmon share the trait of returning to the waters in which they were born to spawn and die. During the summer months this means rivers are clogged with dying fish, and a lot of very happy bears.

King salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) grow to 100 pounds, although not many people will ever see one that size. They’re blue-green on the back, with silver sides, and might spend anywhere from one to seven years at sea before returning to their home streams.

Coho, or silver salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), which grow from 8 to 12 pounds, don’t have the tail spots that kings do. Fins are usually tinted with orange, and the male has a hooked snout.

Sockeye, or red salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), spend one to four years in the ocean, and then do the run home. Average weight is around 4 to 8 pounds at maturity, but they can get bigger; some around 15 pounds have been caught.

The pink, or humpback salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), grow to about 4 pounds. They’re steel-blue on top and silver on the side. They get their nickname, humpie or humpback, from the hump and hooked jaws that develop when they enter freshwater. Pink salmon mature in only two years, and make up the bulk of Alaska’s commercial salmon catch.

Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), which are green-blue on top with small black dots, mature after roughly four years. They spend most of that time at sea, primarily in the Bering Sea or the Gulf of Alaska. A full-grown chum will weigh 7 to 15 pounds.

Sea otter (Enhydra lutris)

Sea otters don’t have blubber; instead, air trapped in their dense fur keeps their skin dry. Beneath their outer hairs, the underfur ranges in density from 170,000 to 1 million hairs per square inch. Not surprisingly, the otter spends much of every day grooming. Otters also eat about 14 crabs a day, or a quarter of their body weight.

Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus)

Its ability—and tendency—to roar is what gives the sea lion its name. Because they can rotate their rear flippers and lift their bellies off the ground, sea lions can get around on land much more easily than seals can. They are also much larger, the males reaching up to 9 feet and weighing up to 1,500 pounds. They feed primarily on fish, but will also eat sea otters and seals.

Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus)

The walrus’s ivory tusks can be dangerous weapons; there are stories of walruses killing polar bears when attacked. Weighing up to 2 tons, the walrus’s primary food includes clams, mussels, snails, crabs, and shrimp. You won’t see a walrus unless you get pretty far off the beaten track; Round Island is perhaps the best viewing spot.

Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea)

These are the world’s long-distance flying champs; some members of their species make annual migratory flights between the high Arctic and the Antarctic. Sleekly beautiful, the bird has a black cap and striking blood-red bill and feet; in flight, their long, split tails look like kite streamers. Like all terns, they’re extremely agile fliers, and can hover almost as well as hummingbirds. Spotted out to sea, almost anywhere along the coast, or inland looking for small fish in ponds and marshes.

Pacific Halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis)

The halibut is the largest of the flatfish to inhabit Alaska’s coastal waters, with females weighing up to 500 pounds. Long-lived “grandmother” halibut may survive 40 years or more, producing millions of eggs each year. Bottom dwellers that feed on fish, crabs, clams, and squid, they range from the Panhandle to Norton Sound. Young halibut generally stay near shore, but older fish have been found at depths of 3,600 feet.

Experiencing the Sea

To really see the sea, you’re going to need a boat.

Inside Passage AMH Ferry

The Alaska Marine Highway runs ferries from Bellingham, Washington, to as far out as Dutch Harbor, in the Aleutians. But there are also some island areas, where the land meets the sea, that offer a great chance for spotting wildlife.

Wildlife-Watching Cruise

The best whale-watching is in Southeast Alaska: a lot of humpbacks hang out close to Juneau, making it the easiest place to start from. Frederick Sound is famous for its huge humpback population, as is Icy Strait, near the entrance to Glacier Bay.

Glacier Bay itself is one of the richest marine environments in the state, with humpbacks, orcas, seals, porpoises, and more.

Trip to Remote Pacific Islands

For migratory birds and Northern Pacific seals, the place to go is the Pribilof Islands. Approximately 200 species of birds have been sighted on the twin islands of St. Peter and St. Paul, out in the middle of the Bering Sea, but you will almost certainly need to be part of a guided tour to get there. The Pribilofs are also home to the world’s largest population of fur seals.

AMH Ferry to the Aleutians

A little more accessible, the Aleutians—particularly Dutch Harbor—are also spots for adding to the life list, since many vagrants appear. Take the Alaska Marine Highway from Kodiak for the three-day run to Dutch. Along the way, you’ll likely see humpbacks, fin whales, orcas, and more puffins, murres, and auklets than you knew the planet could hold.

The Sea Top Guides

Wildlife-Watching Excursions

If you have the opportunity to travel to Sitka, Otter Quest is a great guide company for spotting not just otters but the whole spectrum of wildlife.

Believe it or not, there’s an excellent snorkel outfitter in Ketchikan that facilitates trips most experienced snorkelers give an enthusiastic two thumbs up to. Snorkel Alaska (S. Tongass Hwy. and Roosevelt Dr. | 99903 | 907/247–7783 | www.snorkelalaska.com) will provide a wet suit for protection against the water temperatures; you’ll likely get an up-close view of such fascinating tidal sea creatures as giant sunflower stars, bright blood stars, and sea cucumbers.

If you want to get down to water level but aren’t so keen on outright submersion, Southeast Sea Kayaks (907/225–1258 or 800/287–1607 | www.kayakketchikan.com) specializes in day trips that still take you to some of the remotest inlets in Southeast.

Orca Enterprises (with Captain Larry) (907/789–6801 or 888/733–6722 | www.alaskawhalewatching.com), out of Juneau, is a favorite Southeast whale-watching guide company; Captain Larry notes his whale-spotting success rate is 99.9% during the summer months. His success rate is due in part to the speediness of his boat; he’s able to cover more ground than some of the larger vessels.

If you’ve only got a few hours, Weather Permitting Alaska (907/209–4221 | www.weatherpermittingalaska.com) can get you out and back in about four hours. The ship is luxury-level with delicious food served, a plus.

Wildlife Tours Farther Afield

If you can afford the trip out in terms of time and money, and if you have even a slight interest in birds, travel to the Pribilofs with Wilderness Birding Adventures. The guides with Wilderness Birding lead trips here regularly and have in-depth knowledge about the many different ways birds and other animals come from across the sea to breed here. Because of the wildlife that comes here, it’s one of the most unique seascapes you could hope to experience in the state. Wilderness Birding also runs trips to other parts of the state; among other combinations, you could match a tour to the Pribilofs with another trip to the Brooks Range to immerse yourself in the mountains.

Previous Chapter | Beginning of Chapter | Next Chapter | Main Table of Contents